Jung’s Psychological Types Personality refers to those qualities which make us what we are, which give us a personal identity and distinctive individuality. It encompasses our habitual patterns of behavior, which we express through physical and mental activities and attitudes. Jung's Psychological Types , published in 1921 in Switzerland, is only one among many personality theories. Nevertheless, it impresses us by its relevance to many facets of life. The types Jung describes are in evidence in our families, among friends and neighbours, and at work They are also clearly depicted by writers, poets, philosophers, artists and composers. If this theory is so powerful, the reader may ask, and if it was developed over seventy years ago, why is it attaining prominence only now? One possible explanation is the prejudice of behaviorists and cognitive psychologists toward depth psychology. Other explanations arise from the sheer volume and complexity of Jung's work, the perceived impracticality of his theories, their lack of application to some systems of psychology, and the difficulty of accurately measuring his typologies. Jung's type theory was originally developed to explain his differences with Freud. The book, Psychological Types (in German: Typologie), was translated by one of Jung's close associates, H. Baynes, only two years after it was published in German. All the same, nobody paid much attention to the theory until fairly recently. It lay dormant for decades, until it was gradually "discovered," mainly by North Americans. The theory gained prominence and popularity in the US and Canada through Katharine Briggs and her daughter, Isabel Briggs Myers, who developed a test to measure the various types Jung had proposed. They were among the first to see its value and power in a wider context beyond the domain of analytical psychology. The following synopsis will describe Jung's theory of psychological types. Our discussion is divided into three parts: first, the concepts of attitudes and functions; next, the way attitudes and functions combine into eight types; and finally, the notion of differentiation and development of functions. Attitudes and Functions At the very outset, we wish to clarify our approach and elaborate our basic premise in describing Jung's theory. We intend to present what Jung wrote--not our interpretation of it, nor that of others--in a condensed, readable, and simplified form. We have tried not to deviate too far from his words, because Jung expressed himself well, if not always coherently, and chose his terms with care. Secondary sources--that is, writers and researchers who have elaborated and applied Jung's theory--are deliberately omitted from our discussion. In perusing these sources (e.g., Keirsey & Bates, 1984; Myers-Briggs, 1985; Sharp, 1987; Wheelright, et al., 1964), we reached the conclusion that each author used Jung selectively. We prefer to go back to Jung's original work rather than citing authors who selected only those aspects of his theory that interested them personally.

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

-

Jungs Psychological Types

Personality refers to those qualities which make us what we are, which give us a personal identity and distinctive individuality. It encompasses our habitual patterns of behavior, which we express through physical and mental activities and attitudes.

Jung's Psychological Types, published in 1921 in Switzerland, is only one among many personality theories. Nevertheless, it impresses us by its relevance to many facets of life. The types Jung describes are in evidence in our families, among friends and neighbours, and at work They are also clearly depicted by writers, poets, philosophers, artists and composers.

If this theory is so powerful, the reader may ask, and if it was developed over seventy years ago, why is it attaining prominence only now? One possible explanation is the prejudice of behaviorists and cognitive psychologists toward depth psychology. Other explanations arise from the sheer volume and complexity of Jung's work, the perceived impracticality of his theories, their lack of application to some systems of psychology, and the difficulty of accurately measuring his typologies.

Jung's type theory was originally developed to explain his differences with Freud. The book, Psychological Types (in German: Typologie), was translated by one of Jung's close associates, H. Baynes, only two years after it was published in German. All the same, nobody paid much attention to the theory until fairly recently. It lay dormant for decades, until it was gradually "discovered," mainly by North Americans. The theory gained prominence and popularity in the US and Canada through Katharine Briggs and her daughter, Isabel Briggs Myers, who developed a test to measure the various types Jung had proposed. They were among the first to see its value and power in a wider context beyond the domain of analytical psychology.

The following synopsis will describe Jung's theory of psychological types. Our discussion is divided into three parts: first, the concepts of attitudes and functions; next, the way attitudes and functions combine into eight types; and finally, the notion of differentiation and development of functions.

Attitudes and Functions

At the very outset, we wish to clarify our approach and elaborate our basic premise in describing Jung's theory. We intend to present what Jung wrote--not our interpretation of it, nor that of others--in a condensed, readable, and simplified form. We have tried not to deviate too far from his words, because Jung expressed himself well, if not always coherently, and chose his terms with care.

Secondary sources--that is, writers and researchers who have elaborated and applied Jung's theory--are deliberately omitted from our discussion. In perusing these sources (e.g., Keirsey & Bates, 1984; Myers-Briggs, 1985; Sharp, 1987; Wheelright, et al., 1964), we reached the conclusion that each author used Jung selectively. We prefer to go back to Jung's original work rather than citing authors who selected only those aspects of his theory that interested them personally.

-

The following descriptions of attitudes, functions and types contain the essence of Jung=s theory (admittedly, as we perceive and judge it). We have attempted to organize the descriptions in a coherent, logical, and sequential manner, bringing together passages from different sections of the book to draw a clearer picture of each type. More specifically, we have categorized and sorted, gathered scattered ideas and organized them, pulled together negative and positive aspects, consolidated, highlighted, and simplified--using Jung's own words or close paraphrases, to avoid distortions, misinterpretations, and falsifications. We have omitted references to gender (Jung laid himself open to charges of sexism), the fine arts (many artists, for example, are infuriated by his limited discernment of paintings) and mental illnesses (these are not relevant to our developmental view of Jung's theory).

We should point out that Jung's descriptions of attitudes and functions create an image of pure, undiluted, absolute types that are rarely embodied in actual people. For example, his description of extraverts seldom applies to single individuals. Similarly, Jung=s description of the extraverted thinking function disregards the moderating effects of the other functions.

At the most general level, Jung identifies two basic types of people, two contrary attitudes, two mechanisms of adaptation and defense: introversion and extraversion. These traits are found in every human being, and help us understand the wide variations that occur among individuals. They are neither traits of character nor attributes of gender, but appear to be randomly distributed. Both modes of psychic reaction operate alternately in the same person, and can be turned on and off. One of them, extraversion, moves toward the object: people or things; the other, introversion, moves toward the subject: one's own mind.

Extraversion

The interest of extraverts is directed toward the object. Objects can be people or things, which act like a magnet on extraverts, allowing them to find themselves--to unfold, stream outward, and embrace the world. This interest can be charged with psychic energy and can manifest itself in extraverts, as a need to get outside themselves. It makes them energetic, active, and full of life; it gives them a relaxed and easy attitude. Through the object, they take delight in themselves and in people; they are "open, sociable and jovial, or at least friendly and approachable...on good terms with everybody, or [apt to] quarrel with everybody, but always relat[ing] to them in some way and in turn affected by them" (330).

The libido of extraverts is directed toward material things and external reality. They are interested in the tangible phenomena of the outside world, and motivated by facts and experiences. Extraverts fit easily and well into existing conditions, exert compelling personal influence on others, and are in turn influenced by others. They are able to gather around them a large and enthusiastic circle of people, and enjoy doing so. Toward the outside world extraverts are full of confidence and trust, assurance and initiative; here they feel united, reconciled, and merged with their fellow human beings. They have "a need to join in and 'get with it,' the capacity to endure

3

-

bustle and noise of every kind, and [they] actually find [these things] enjoyable" (549). They attach great importance to the figure they cut.

Of course, such a glorious description of extraverts cannot be left to stand by itself, but needs some counterweight to give it balance. Jung supplies it readily. Inasmuch as the outside world is of interest and importance to the extravert, he says, in extreme cases the extravert gets sucked right into it and loses himself there. This assimilation by the object, by outer happenings, prevents an individual's personal, subjective impulses (thoughts, wishes, feelings, needs, etc.) from reaching consciousness. These impulses take on an infantile, archaic, and unconscious character. They may reveal themselves in almost childish selfishness, ruthlessness, and even brutality.

In less extreme cases, identification with the object, and the accompanying loss of subjectivity, leads to a valuing of sense impressions over reflection and forethought. Extraverts often jump headfirst into situations "only to reflect afterwards that they had perhaps landed themselves into a swamp" (533). Lack of reflection also results in ideas that are badly digested and of doubtful value, a poor ability to synthesize, "theories" which are merely accumulations of experiences, and lack of the "unity of settled systems" that results from reflection. Because his own inner thoughts and feelings are not taken into account, the extravert's "philosophy of life and his ethics are as a rule of a highly collective nature, with a strong streak of altruism, and his conscience is in large measure dependent on public opinion" (549).

Introversion

Jung has rather more to say about introverts than extraverts. This may partially reflect his own bias, since--according to his own and various biographical accounts--he himself was introverted. It may also be an attempt to reveal the ways of the introvert in more depth since Jung claims people are generally rather badly informed about this mechanism.

The life energy of the introvert moves toward the subject; that is, toward a person's own psyche. Introverts like to withdraw into themselves; to meditate, reflect, and contemplate--mainly about themselves. Thus introverts appear outwardly calm, possess quiet manners, and prefer an atmosphere of repose. It is difficult for outsiders to read them, because they are reserved, rather inscrutable, mistrustful, quite anxious, and generally not forthcoming. They keep their ruminations to themselves and do not show the emotions, passions, and powerful impulses that lie dormant under the surface of their equanimity. They hold their ground against outside influences by assigning them a low value, staying aloof from them, detaching and isolating their personalities from external reality. Introverts draw upon flashes and snippets of the outside world to take secret delight in their own inner life; objects are no more than outward tokens of this life. By withdrawing from too intimate a contact with the world, they overcome their fear of powerful and dangerous objects, and of their own impotence. When the introvert asks questions, "it is not from curiosity or a desire to create a sensation, but because he wants names, meanings, explanations to give him subjective protection against the object" (517).

4

-

Introverts lead a conscious inner life. They love to understand and grasp ideas, to perceive inner images of beauty, to order and synthesize their psychic contents, and to create abstractions that collect the diversity of their impressions into a fixed form. Introverts go so far with this process that they become lost and submerged in the inner image, so that "finally its abstract truth is set above the reality of life" (297). They themselves become the center of their interests. Their inner movement, activity, and development are of crucial importance to them. The introvert, Jung writes vividly,

has a distinct dislike of society as soon as he finds himself among too many people. In a large gathering he feels lonely and lost. The more crowded it is the greater becomes his resistance. He is not in the least 'with it', and has no love of enthusiastic get-togethers. He is not a good mixer. What he does, he does in his own way, barricading himself against influences from outside. He is apt to appear awkward, often seeming inhibited, and it frequently happens that, by a certain brusqueness of manner, or by his glum inapproachability...he causes unwitting offence to people. His better qualities he keeps to himself, and generally does everything he can to dissemble them. He is easily mistrustful, self-willed, often suffers from inferiority feelings, and for this reason is also envious. [He] has an everlasting fear of making a fool of himself, is usually very touchy and surrounds himself with a barbed wire entanglement so dense and impenetrable that finally he himself would rather do anything than sit behind it. He confronts the world with an elaborate defense system compounded of scrupulosity, pedantry, frugality, cautiousness, painful conscientiousness, stiff-lipped rectitude, politeness and open-eyed distrust. His picture of the world lacks rosy hues, as he is over-critical and finds a hair in every soup. (551)

Jung goes on to say that the introvert is also pessimistic and worried, and never feels accepted because he himself does not accept the world, but judges it by his own critical standards. He likes to self-commune in his own safe world, which Jung likens to a carefully tended and protected garden, closed to others. He likes his own company best and feels at home in his world,

where the only changes are made by himself. His best work is done with his own resources, on his own initiative, and in his own way. If ever he succeeds, after long and often wearisome struggles, in assimilating something alien to himself, he is capable of turning it to excellent account. Crowds, majority views, public opinion, popular enthusiasm never convince him of anything but merely make him creep still deeper into his shell.

Introverts exercise little direct personal influence over others, and therefore have few friends, acquaintances, or disciples. A possible reason for this is that they generally resist outside influences and have problems warming up to other people and overcoming their shyness and defensive distrust of others. This does not mean that introverts are completely as a loss socially but rather that other people make them uneasy and disquiet them. They prefer to retreat into themselves, to concentrate their psychic energy on their inner life. Introverts thus live apart, absorbed in themselves.

5

-

Introverts give an impression of slowness. This is partially due to their ability to engage in forethought: they like to consider a situation before they act, and interject their personal views between what they perceive and how they act. Because of their personalization of reality, their actions do not always fit the objective situation. Consequently, they are the victims of numerous misunderstandings. Jung claims that these misunderstandings give introverts a certain satisfaction because they reaffirm their pessimistic outlook. "That being so, it is easy to see why [they are] accused of being cold, proud, obstinate, selfish, conceited, cranky, and what not" (552). Their lives are ruled by their subjective world, which they sometimes believe, "in moments of delusion, to be the objective one" (552).

Two Mechanisms

Since the psychic values of the two types are diametrically opposed, they naturally speak ill of each other: "the extravert has the same repugnance, fear, or silent contempt for introversion as the introvert for extraversion" (102). Worse, the extravert "inevitably comes to the conclusion that the introvert is either a conceited egoist or crack-brained bigot...harboring an unconscious power complex" (377). Further, extraverts dislike the way introverts express generalizations, seeming to rule out others= opinions from the start, as well as the inflexibility of their subjective standpoints and judgments, through which they set themselves above all objective situations and facts. To the extravert, the subjective process is little more than a disturbing and superfluous appendage to objective events.

Introverts, on the other hand, find it incomprehensible that the object should be the decisive factor: "This dependence on the object seems to the introvert a mark of the greatest inferiority" (517). Introverts are distressed by the quickness and volatility of extraverts. When criticized by them, introverts are at a loss for what to say.

Besides this mutual bias, the two attitudes can also produce inner dissension. "The opposition between the types is not merely an external conflict between men; it is [also] the source of endless inner conflicts; the cause not only of external disputes and dislikes, but of nervous ills and psychic suffering" (523). Each of us have probably experienced the pull of the two inner forces and their disquieting manifestations.

Predilections toward introversion or extraversion seem to depend on a person's inborn, innate disposition. Yet, since the two mechanisms also shape character through habitual use, environmental influences can be just as important. They allow some people to alter their attitudes from one moment to the next, as situations change. Usually, however, these individuals= dominant attitude is not affected, and reestablishes itself when the environmental forces are no longer operative.

The two mechanisms can be active or inactive at any one time within the same individual. They exist successively, rather than side by side. An introvert may find herself in an extraverted phase

6

-

vis--vis the external world at a point, for instance, when she is in a totally congenial harmonious milieu. Such an environment may induce her to appear vigorously active, so that others think they are dealing with an extravert. An extravert in an introverted phase will appear passive and calm to outsiders, even though the inner activity of his thought or feeling may be quite lively: "put an extravert in a dark and silent room, where all his repressed complexes can gnaw at him, and he will get into such a state of tension that he will jump at the slightest stimulus" (287).

We should mention here the influence of libido on the two mechanisms. This "magical power," or psychic energy, which will be discussed later, is said to reside in the depth of our being, to give life and force to each mechanism, and to determine whether a person is shut up within or liberated from herself.

Since people often alternate between extraversion and introversion in quick succession, it is difficult to spot a person=s prevailing attitude. Extraverts can become quite introverted if they remain for prolonged periods in close proximity to introverts. Similarly, introverts can become rather extraverted when they work with small groups of extraverts. Most of the time, however, the two types stand in striking contrast to each other. Even if they do change mode, eventually they will always revert to their dominant attitude.

Thus, typing of attitudes is not always easy. In some cases, where the characteristics are exaggerated, the distinction may appear obvious. For the extensive middle group, however, "which is the most numerous and includes the less differentiated normal man" (516), only "careful observation and weighing of the evidence permit a sure classification" (516). In a lecture delivered seven years after publication of the book on type, Jung appeared more optimistic with respect to typing: "whether a function is differentiated or not can easily be recognized from its strength, stability, consistency, reliability and adaptedness" (540). We may conclude that even though the attitudes are simple in principle, they are more complicated in reality and more difficult to discern. Every individual seems to be an exception to the rule.

Psychic Functions

Attitude types (extraversion or introversion) do not exist by themselves, but only in conjunction with function types. Jung defines a psychological function as "a particular form of psychic activity that remains the same in principle under varying conditions" (436) and "by which consciousness obtains its orientation to experience" (1964, p. 61). The different functions in our conscious psyche allow us to adapt and orient ourselves, to grasp differences between people and to understand our own and others' prejudices.

Jung distinguishes among four distinct functions, two rational and two irrational: thinking-feeling and sensation-intuition. The four functions can be found in both extraversion and introversion, which "appear only as the peculiarity of the predominating conscious function" (520). There are, then, four types of extraverts and four types of introverts: eight attitude-types altogether. Jung describes the function-types in one sentence: "The essential function of sensation is to establish

7

-

that something exists, thinking tells us what it means, feeling what its value is, and intuition surmises whence it comes and whither it goes." (553)

Thinking is the process of connecting ideas by means of concepts. It is activated when people subject their experiences to consideration and reflection. When thinking is active and directive, it is an act of the will; when it is passive and undirected, it merely occurs. In the former case, judgment is exercised through the intellect; in the latter, connections come about of their own accord. Jung points out that the quality of thought varies widely among people: "...there are a surprising number of individuals who never use their minds if they can avoid it, and an equal number who do use their minds, but in an amazingly stupid way." (1964, p.60) Yet all thinking types apply those mental operations that seem to them the most logical, reasonable and correct to guide them in life.

Feeling is the subjective process that imparts value to every conscious content. Whatever comes to mind, even a mood, is imbued with value--accepted or rejected, liked or disliked, considered good, bad or indifferent. Unlike what occurs with thinking, no conceptual connection of ideas takes place when feeling is involved. Jung differentiates between abstract and concrete feeling. Abstract feeling entails universal values rather than specific contents of the conscious mind; it produces a general mood. Concrete feeling entails personal values applied to specific content. Jung is quite aware that the very nature of feelings makes intellectual judgment difficult. His definition of feeling stresses valuation; the common definition emphasizes affect and emotion.

Sensation, or sensing, is the operation of sense perception. It conveys to the mind images of both the external and internal world. Like feeling, sensing can be concrete or abstract. Concrete sensation is a reactive process: a person sees, hears, touches, or smells something and reacts to it. Abstract sensation is proactive, mobilized by the will; it detaches itself from what is perceived (person, thing, etc.) and concerns itself with the essence of what is perceived. Seeing the details of a flower is an example of concrete perception; perceiving what is salient about the flower--its brilliant color, for instance--is an example of abstract perception.

Intuition is the process of unconscious, indirect perception. The focus of this perception can include internal or external objects, and the relationships between them. With intuitives, something presents itself whole and complete to the mind, without any indication of where it came from. Intuition thus derives an overall impression from a situation; a whole picture, including a sense of where it comes from and where it may go. Jung calls intuition an Ainstinctive apprehension,@ whereby ideas and associations are added to what is perceived. When intuition is subjective, it refers to a person's perception of unconscious, internal psychic data. When it is objective, it refers to subliminal perception of external data.

Like thinking and feeling, sensing and intuition are opposites. A person who is paying attention to details will not be able to keep the overall picture in mind, while a person who seeks an overall impression will not be able to concentrate on specifics at the same time. Therefore, if and individual prefers and develops the intuitive mode as his main function, sensing will be repressed and, for lack of use, undeveloped in him.

8

-

Psychological Types

As we explained at the outset, the following description of the eight types is based on Jung's original work, Psychological Types, first published in 1921, and in small part on Man and his Symbols, completed a few days before his death in 1961. The descriptions are organized according to their classification as rational or irrational functions.

Rational Judgmental Types

Jung considers thinking and feeling to be rational or judgmental functions. Judgments are decisions, opinions or estimates as to the value, importance or relative worth of something. Rational functions provide direction to people, based on their reflection and deliberation. The lives of rational types are subordinated to judgments; only choices based on reason and logic are accepted. Everything irrational and accidental is excluded.

This polar opposition leads to biases. To the rational types, the irrational (sensing and feeling) ones appear scarcely credible. How can you orient yourselves by a hodge-podge of accidental factors rather than by reason?, the rational types ask the others. They find it painful to think that relationships will only last "as long as external circumstances and chance provide a common interest" (372).

When rational types make use of their auxiliary function, their perceptions are, for the most part, chosen and guided by rational judgment. However, antagonistic, unconscious elements of perception are at times so strong that they disrupt the conscious rule of reason.The nature of judgment is different when exercised by extraverted and introverted functions. Extraverted thinking and feeling types have an outward-oriented rationality that gives their lives a definite pattern. Their rapport with others is based on behavior generally considered to be rational and reasonable. The subjective, individualistic aspects of their thinking are repressed. The rationality of introverted thinking and feeling types is based on subjective, invisible, and intangible data. This subjectivity biases their judgments, fostering misunderstandings and giving them a tendency toward egotism.

With Extraverted Thinking types (ETs), all vital energy flows into thinking. Their thoughts are generally logical, positive, productive, progressive and creative. They orient themselves by external facts and objective data transmitted by sense perception and by generally accepted ideas, equally determined by external data. However, their thinking can lead to new conceptions of ideas and to the discovery of new facts or, through logical analysis, to new combinations of old facts. All their activities and behaviors are thus dependent on intellectual conclusions.

What makes ETs extraverted is that "input"--the facts and ideas they work with--comes from the outside and that "output"--the conclusions they draw from the data and ideas--is directed outwards. When these external data overwhelm them, ETs= thinking can become rather imitative and dull, affirming "nothing beyond what was visible and immediately present in the objective

9

-

data in the first place" (345). In the process, they lose valuable and meaningful aspects inherent in situations. Such dissociation of thought only ends when they use a simple idea to give coherence to the disordered whole in order to "get back on track".

ETs have a tendency to elevate outer reality into a ruling principle or formula. This formula contains and embodies their entire meaning of life. It is truth as they see it, and it represents their purest conceivable formulation of outer reality. By this formula, good and evil, beauty and ugliness, are measured. They elevate the formula into universal law which they then put into effect everywhere, all the time, and which they themselves and others are expected to follow and obey. Anything new that does not fit the formula is either condemned or considered an imperfection. Viewpoints that violate the formula are considered reluctantly, if at all. Critics are silenced through invalidation of their arguments.

If the formula is broad and encompassing, it plays a useful role in social life and has a beneficial and favorable influence. Its oughts and musts are then not too disturbing. But if the formula is applied in a narrow, rigid fashion, it becomes dogmatic and has negative effects. It then takes on the character of fanaticism or intellectual superstition, with an overtone of absoluteness. Those closest to the ET are the first to taste the unpleasant consequences of this formula. The majority of ETs move in between these two extremes. Because they cannot guide their entire life by one formula, sooner or later they will feel disturbed by it, will consequently modify it, and will then rationalize the modification.

Feeling, the inferior function, is opposed to the conscious aims of the ET's formula and therefore becomes greatly distorted. ETs feelings may grow sullen, resentful and mistrustful, their voices sharp, and their behavior aggressive. "Their sanction is: the end justifies the means. Only an inferior feeling function, operating unconsciously and in secret, could seduce otherwise reputable men into such aberrations" (349). Inferiority of feeling also shows itself in other ways: in poor taste, neglect of family and friends, in over-sensitivity, or prejudices.

Extraverted Feeling types (EFs) are guided in their lives by feeling. Feeling has a personal quality: "In my view, the extraverted feeling type has really the chief claim to individualized feeling, because his feelings are differentiated" (283). Due to its extraverted nature, the personality of this type adjusts itself to and harmonizes with external conditions, objective situations, and commonly held values. Thus, although feeling is individualized, it subordinates itself entirely to the influence of external circumstances, "the object being the indispensable determinant of the quality of feeling" (354).

The following may seem like a paradox, difficult for other types to understand, but EFs feel moved to call a painting beautiful, not because they find it so in their deepest inner being, "but because it is fitting and politic to call it so, since a contrary judgment would upset the general feeling situation" (355). To EFs it is therefore most important to establish an intense feeling of rapport with their environment through inner acts of adjustment. It is they who fill the theatres, concerts, and galleries; it is they who support social, philanthropic and cultural institutions; and it

10

-

is they who go with the fashion and trends of the time. Without them, Jung says, a harmonious social life would be impossible.

EFs are good companions, excellent parents, and suitable mates, because they measure up to all reasonable expectations. Their feelings are genuine, if without passion--that is, without suffering or agony, which characterize the deeper feelings of the EFs opposite, the IT. Passionate feelings, Jung says, are an instinctive force common to all; this form of feeling is undifferentiated, and hence not individualized.

The more EFs consider external events and situations important, the more their individual personalities become lost and dissolved into the feeling of the moment. The personal, warm and genuine quality of feeling then disappears and turns cold, "unfeeling," and artificial. It no longer speaks to the heart, but becomes "padding for a situation, but there it stops, and beyond that its effect is nil" (356).

In addition, because life presents a constant succession of situations that evoke feelings, the EF's personality can get split into many different feeling states, resulting in "self-disunity." The expression of feeling is then no longer personal, but appears as a mood, manifesting itself in "extravagant displays of feeling, gushing talk, loud expostulations, etc., which ring hollow" (358) and which the observer cannot take seriously.

EFs must therefore be careful not to have their personalities swallowed up in successive feeling states. Thinking disturbs feeling. What EFs cannot feel, they cannot consciously think. When asked what they think, they are likely to begin their reply with "I feel that...". Conclusions based on thinking, when they disturb feelings, are rejected. Thinking is only tolerated as a servant of feeling. For that reason it appears infantile, archaic, and negative.

11

-

Introverted Thinking types (ITs) like to create ideas, formulate theories, and open up new prospects or insights. These are not triggered by external sources but by contemplation of inner images and conceptions. ITs are not concerned with the intellectual reconstruction of concrete facts, but with shaping the inner images they perceive into luminous ideas. Facts are collected only to illustrate their ideas, to present them as evidence, or to see how they fit or fill in the idea. Indeed, translating an initial image into an idea that fits external facts is one of the main weaknesses of ITs. They are inclined to force facts to fit their ideas, or else to ignore them. Basically they delight in using their powers of thinking to create new abstract ideas for the ideas= own sake, regardless of external validity or practical applicability. Traditional or commonly shared ideas do not interest them; likewise, they are indifferent or averse to anything practical or experiential, rarely applying their ideas to real-world situations. The reason for this is that ITs have no idea of how their abstract thoughts connect to reality--unlike ETs, whose concrete thoughts do sustain such a connection.

ITs value their conscious, intense inner lives and try to shut out all external influences. They love contemplation, reflection and solitude. Such a peaceful state allows them to immerse themselves in the process of assimilating and understanding ideas. They can then use their intellect to think out problems to the limit, admittedly complicating them at times. But they never shrink from a risky or unpleasant idea, nor "from thinking a thought because it might prove to be dangerous, subversive, heretical, or wounding to other people's feelings" (384).

Because of their captivating inner preoccupations, ITs place their relations to other people at a secondary level of importance. Yet they appreciate good arguments, and one can talk to them in a reasonable and coherent manner. They annex others' meanings to their own thoughts without attempting to press their convictions on those others. But they never yield to opposing arguments, and can respond quite viciously if their own ideas are criticized, however just that criticism may be. At the same time, they are afraid of the disagreeable effects they produce through their own criticisms because they believe others to be as sensitive as they are themselves. They cling to their own convictions in a rigid, stubborn, and headstrong way, impervious to influence. They will not go out of their way to win anyone's appreciation, especially anyone of influence. If others cannot understand their ideas, ITs consider them stupid, failing to understand that their own thoughts are not clear to everyone. When they do feel that they have been understood, and believe their ideas to be accepted, they can easily overestimate their own abilities.

Nevertheless, the better one knows ITs, the more favorable one's judgment of them becomes. Close friends value being on intimate terms with them. To avoid becoming isolated, ITs become quite dependent on these relationships. However, if they cannot form close friendships, their "originally fertilizing ideas become destructive, poisoned by the sediment of bitterness" (386). Outsiders and casual acquaintances perceive ITs to be rather prickly, taciturn, gauche, inconsiderate, unapproachable, arrogant, domineering, and unsympathetic. Professionally, they provoke the most violent opposition; because ITs do not know how to deal with antagonism, they often make colleagues feel superfluous. Usually though, they try to act polite and kind in order to disarm and pacify opponents so that the latter do not become bothersome.

12

-

When ITs get lost in their own immense inner world of ideas and truths, they may act extraordinarily unpractical. As a result, their work proceeds slowly and with difficulty. "[Their] style is cluttered with all sorts of adjuncts, accessories, qualifications, retractions, saving clauses, doubts" (385). They let themselves be brutalized and exploited in order to gain the peace they need to pursue their ideas. Every so often, others get to see the fruits of their deliberations. But frequently, they merely Adump@ their ideas, without much patience . If these ideas fail to thrive on their own account, or if they vanish behind a cloud of misunderstanding, ITs easily get annoyed.

The ITs= inferior function is feeling. They are tormented by their emotions and bottle up their feelings to the point of becoming completely overwrought. Believing their feelings to be unique, they fail to realize that extreme emotion possesses little that is individual. The more their thinking function is consciously activated, the more their feeling function is prey to unconscious fantasies. "In contrast therefore, to [their] logical and well-knit consciousness, [their] affective life is elemental, confused and ungovernable" (155). They become unreasonably inflexible in things that touch their emotions, and their judgment appears arbitrary and ruthless. They prefer to keep their feelings to themselves, or else to express them in rational terms ("Let me think about how I feel!@).

Introverted Feeling types (IFs) feel everything, just as ITs think everything. In some respects, the two types are very much alike, particularly with regard to the outside world. In typical introverted fashion, both of them underrate and dismiss the object without paying much attention to it. The world serves merely as a stimulus to generate intense feelings; otherwise, IFs shrink back from it. They prefer to seek inspiration primarily from the fathomless store of primordial images which have no existence in reality. These images can be as much ideas as feelings, but each significant idea has feeling values attached to it (e.g., God, freedom, immortality).

Jung points out that it is difficult to give an intellectual account of the positive feeling process. "A more than ordinary descriptive or artistic ability@ is needed Abefore the real wealth of this feeling can even be approximately presented or communicated to the world" (388). Seldom appearing on the surface, the depth of such feeling can be guessed, but never grasped, and its existence only inferred indirectly. In communicating with others, IFs have to externalize their feelings in a way that arouses a parallel feeling in others. Otherwise, they feel misunderstood and become silent and inaccessible. Yet Jung claims that the peculiar nature of IFs gains clarity once one becomes aware of it.

In the normal IF type, the ego, center of consciousness, is subordinated to images that arise from the unconscious. In this case, the outward demeanor [of the individual] is harmonious, inconspicuous, giving an impression of pleasing repose, or of sympathetic response, with no desire to affect others, to impress, influence, or change them in any way" (389). IFs observe a benevolent though critical neutrality, but are mostly silent and inaccessible, keeping their true motives to themselves, often hiding behind a childish or banal mask, inclined to melancholy, neither exposing nor revealing themselves.

13

-

Although IFs display "a constant readiness for peaceful and harmonious co-existence, strangers are shown no touch of amiability, no gleam of responsive warmth, but are met with apparent indifference or repelling coldness" (389). IFs restrict feeling relationships to a safe middle path, curtailing expressions of affection and making no effort to respond to the real emotions of others. When they feel threatened, they assume an air of profound indifference and "a faint trace of superiority that soon takes the wind out of the sails of a sensitive person" (389), causing him to feel superfluous and undervalued.

With abnormal IF types, when their feelings are distorted by egotism, or when they fall into their inferior thinking function, causing them to feel overwhelmed by the outside world, their mysterious power of intense feeling can turn into bossiness, and their sense of harmony ceases. They then try to express their feelings through others, by letting their intense emotions flow into them and by overpowering them with their feelings. Such domineering behavior becomes a stifling and oppressive, extending its influence to everybody around them. This mysterious power can stem from deeply felt unconscious images which IFs sometimes believe to be their own. When this occurs, their feeling power turns into a banal desire to dominate. Unconscious thinking can also project itself into open opposition: "other people are thinking all sorts of mean things, scheming evil, contriving plots, [hatching] secret intrigues" (391). These projections then need to be forestalled through counter-intrigues and suspicions.

Irrational Perceptive Types

Jung calls the two other functions, sensing and intuition, irrational--that is, undirected, perceptive, and lacking the power of reason. The irrational is beyond reason; judgments are unintelligible. People with an irrational dominant function will go with the flux of events, react to every occurrence, and lack direction by logic. Although they become progressively aware of what is happening around them, they do not interpret or evaluate what they perceive, and often behave in ways that are illogical and contrary to reason. All rational communication is alien and repellent to them. They establish rapport through common perceptions and experiences. This does not mean that irrational types have no judgmental functions. They do, if they have a pronounced auxiliary function, but often the sheer intensity of their perceptions allows no time for judgments.

The irrational types are naturally biased against the rational types, whom they regard with suspicion and believe to be only half-alive, and "whose sole aim is to fasten the fetters of reason on everything living and strangle it with judgments" (371). They find it difficult to understand how one can put rational ideas above actual, live happenings, and generally find the rational types unreliable and hard to get along with.

In the extraverted mode, perceptions focus on events as they happen. What arises from within is not accorded much significance. Introverted irrational types experience and perceive inwardly. What goes on within them is inaccessible to judgment from the outside. Because they lack reason, and thus conviction, they find it hard to translate their inner perceptions into intelligible language. This limits their capacity for expression and communication. "From an extraverted and

14

-

rationalistic standpoint, these types are indeed the most useless of men" (404), Jung writes. Yet, he continues, they are not blinded by the intellectual fashion of the day and do not fall into the trap of overestimating human communication.

Extraverted Sensing types (ESs) are conspicuously well-adjusted to reality. They are drawn to things in life that are touchable, visible, detectable, discernible, perceptible, and palpable. In short, they are interested in reality as it is, in pure sense perception: "no other human type can equal the extraverted sensation type in realism" (363). All concrete objects and processes perceived with their senses enter into their consciousness. They hear and see everything to the limits of their physiological ability; their sensitivity to the outside world is extraordinarily developed. They value things and people, facts and data, to the extent that they excite sensations. The more intense the sensation produced--and it does not have to be pleasurable--the more value ESs assign to it.

The phrase "real life lived to the full" (363) characterizes ESs. They are easygoing, sociable, quite likeable, and considerate of others. They have no desire to dominate. They can be quite jolly, know how to enjoy themselves, and are able to differentiate their sensations to the finest pitch of aesthetic purity and good taste. Their love, too, "is unquestionably rooted in the physical attractions of its object" (364). ESs know how to dress well, as befits the occasion, and keep a good table for their friends.

When ESs are in bondage to the object--when the object takes over and they are only out to stimulate their senses--their less differentiated functions come into play and show less agreeable tendencies. ESs can then turn quite mean, developing into crude pleasure seekers who ruthlessly exploit an object and squeeze it dry, with a morality that is oriented accordingly. Due to the archaic nature of their weakest function, intuition, they project onto others: "The wildest suspicions arise; if the object is a sexual one, jealous fantasies and anxiety states gain the upper hand" (365). When their judgmental functions, thinking and feeling, are undeveloped, "reason turns into hair-splitting pedantry, morality into dreary moralizing...religion into ridiculous superstition" (365).

ESs do not notice glaring violations of logic. They also have little inclination for reflection. This makes them quite credulous; they accept everything that happens indiscriminately, without rational judgment. Thus they make little use of the experiences they accumulate, treating them instead as starting points for fresh sensations. Many people, ESs included, mistake their highly developed sense of reality for rationality--which it is not. Further, because they lack intuition, they show no interest in conjectures that go beyond concrete sensuous reality; and because they are extraverted and can only receive from the outside, anything that comes from inside is perceived as morbid and suspect.

Extraverted Intuitives (ENs), like all extraverts, are totally outward-directed. Yet their psychology is different--rather peculiar and difficult to grasp, though unmistakable. Unlike the ESs, who are very conscious of what they perceive, ENs= dependence on external conditions is, in the main, an unconscious process. Unconscious perception "is represented in consciousness by

15

-

an attitude of expectancy, by vision and penetration" (366). ENs have an eye for the soul, essence, and heart of things. Yet what they see in people or things may be entirely what they read into them. For Ens, intuition is an active and creative process, triggered by the object. It allows them to perceive relationships between things or matters, to have specific insights into people or situations, to peer around corners or gaze beyond the horizon. Unlike ESs, who are guided by their strongest sensations, ENs never know which stimuli will make an impression on their unconscious minds. Their visions are a kind of fate.

ENs are keenly interested in trying to discover the possibilities inherent in external situations. Apprehending and envisioning a wide range of possibilities gives members of this type their highest satisfaction: "nascent possibilities are compelling motives from which intuition cannot escape and to which all else must be sacrificed" (368). This constant act of sniffing and ferreting out new possibilities and fresh outlets in external life gives ENs a keen nose for things new and in the making. Business tycoons, entrepreneurs, speculators, stockbrokers, promoters, and politicians are often ENs, Jung writes.

The ENs capacity to inspire courage and kindle enthusiasm in others is unrivalled, as long as the situation holds their interest. Then their whole personality and existence is absorbed by the project, which they tackle with utmost intensity and enthusiasm. It is ENs who have the ability to bring their visions to life, and to present them convincingly and with dramatic fire. Stable, normal, and routine conditions suffocate them. When confronted with such conditions, they generally choose either to abandon them without regret or, if forced to endure them, to fall into a disinterested stupor. Ordinary, preexisting situations constitute a prison for them, a locked room from which they must escape by discovering new possibilities.

Although ENs generally have little consideration for the welfare, lifestyle, and convictions of others, socially they are quite well adapted. They are able to exploit social occasions, make the right connections, and seek out people who might be useful to them by making an intuitive diagnosis of their abilities and potentialities. When they are on the scent of a new possibility, however, their concern for their own and others= welfare diminishes, and they pursue their aim without taking much note of personal consequences.

Sensing is the EN's inferior function because it prevents "naive," unconscious perception. When thinking and feeling are undeveloped (that is, when judgment is lacking), these processes carry no weight. They cannot frighten ENs away from new possibilities or influence their morality, which consists mainly of loyalty to their vision. The inferior functions bring about unconscious, archaic impulses: intense projections, compulsive tendencies, sexual suspicions, and forebodings of illness or financial ruin.

The stronger their intuition, the more ENs become fused with the possibilities they envision. They may thus fritter away their lives, moving from one possibility to the next, showing others the abundant promise of each new situation, but never reaping any benefits themselves, always going away empty-handed. They rely entirely on their sixth sense to exploit the possibilities that chance throws their way.

16

-

Introverted Sensing types (ISs), like other introverted types, are merely stimulated by what takes place outside of themselves. Nevertheless, they are also dependent on the object. In contrast to ITs or INs, who can generate images without outside influence, ISs perceptions depend greatly on external stimuli. What they see and hear, however, undergoes considerable modification. They add their subjective dispositions to objective stimuli; in other words, they add their very own unconscious reactions to what they perceive. This alters their sense perception at its sourceas though [they] were seeing [things] quite differently, or saw quite other things than other people see" (394).

This peculiar nature of ISs requires amplification. Basically, they perceive the same things everybody else does. But they do not stop there. They also add their personal meaning, which they perceive as clinging to things or people. What they see may not be found in the things at all; or it may merely be suggested. It is impossible to guess in advance, which things or people will make an impression on them. Here they are strictly guided by the intensity of their sensation. Jung claims that they can apprehend the background of what they see, rather than the mere surface, and transmit images which do "not so much reproduce the object as spread over it the patina of age-old subjective experience and the shimmer of events still unborn. The bare sense perceptions develop in depth, reaching into the past and future" (395).

Probably because their perceptions are often different from reality, ISs are incapable of giving a good account of what they perceive. Others will not easily understand them, nor do ISs often understand themselves. They are at the mercy of their perceptions and, as a rule, have resigned themselves to their isolation. Outwardly they appear as calm, passive, and neutral, showing little sympathy yet constantly striving to soothe and adjust to keep the influence of the object within bounds: "the too low is raised a little, the too high is lowered, enthusiasm is damped down, extravagance restrained" (397). Thus ISs, for the most part, remain divorced from things and people. People feel diminished in their presence. Jung maintains that ISs easily become victims of others' aggression. They "allow themselves to be abused and then take their revenge on the most unsuitable occasions" (397).

ISs are classified as irrational because they orient themselves by what happens in life and, if thinking and feeling are unconscious, organize their impressions in an archaic way, without judgment. If the two rational functions become momentarily conscious, ISs sense the difference as morbid and remain generally faithful to their irrationality. At best, thinking and feeling result in the most necessary and ordinary means of expression. Thus "the normal type will be compelled to act in accordance with the unconscious model. Such action has an illusory character unrelated to objective reality and is extremely disconcerting" (396). In extreme cases, the outside world will appear to the IS as make-believe, and a giant theatrical production.

Intuition, ISs inferior function, is repressed. "This archaicized intuition has an amazing flair for all the ambiguous, shadowy, sordid, dangerous possibilities lurking in the background" (398). The properties of Intuition would contrast glaringly with the well-meaning and gullible harmlessness of this type.

17

-

Introverted Intuitives (INs) are peculiar types. Like other introverts, their attention and interest is inner-directed. Unlike ISs, though, who need reality to give them ideas which they then follow and enhance inwardly, INs draw from their unconscious. The unconscious coexists with the conscious psyche; it is constantly undergoing transformation because it is connected to external life. The images and visions arising from INs= unconscious are therefore not their own. Rather, they are age-old images and archetypes stored in the collective unconscious. These are inherited, accumulated life-experiences that go back to primeval times. Jung believes that these archetypal patterns are part of our psyche. In INs they become activated in the form of images and visions. INs then move from image to image, each arising from "the teeming womb of the unconscious [in] inexhaustible abundance by the creative energy of life" (400).

When the impetus of perception comes from the outside, rather than from the unconscious, INs can quickly see the inner image of what the external object releases in them. They can peer behind the scenes and explore every detail of the image, holding fast to it and observing with fascination how it unfolds, changes, and finally fades. When they communicate the image they see, it usually has little reality or practical value, and is generally written off by others as a fruitless fantasy. Jung points out that these inner images can be just as conscious and real to INs as outer reality is to other types. The only difference is that inner reality is not physical but psychic.

INs are misunderstood even more frequently than other introverts.. Theirs is not a language many people can relate to. They appear to be wise simpletons and mystical dreamers, seers, or cranks. Though they proclaim and foresee new possibilities in more or less clear outline, their arguments lack conviction, and they are so far-removed from reality that they seem strange and weird, even to their friends. Nevertheless, what they perceive are "possible views of the world which may give life a new potential" (400); they "can supply certain data which may be of the utmost importance for understanding what is going on in the world" (401)

When the auxiliary judging function, thinking or feeling, is pronounced, INs tend to reflect on the meaning of their visions. Through judgment, they see themselves as somehow involved in their visions, and become participants rather than mere spectators. They may even feel bound to apply the visions to their own life. But as a rule, Jung states, INs stop at perception.

The INs= inferior function is Extraverted Sensing. Their perception of the outside world is repressed and compensatory in nature, lending their unconscious personality a rather low, primitive, and archaic character. "Instinctuality and intemperance are the hallmarks of this sensation, combined with an extraordinary dependence on sense-impressions" (402). However, sensation gives normal INs enough consciousness to make them aware of their own bodily existence and its effect on others.

Differentiation

18

-

Differentiation means becoming different. It involves the development of distinct differences. Jung applies the concept of differentiation mainly to psychological functions. He distinguishes among primary, secondary, and undifferentiated functions. Among the latter he includes the inferior, or least preferred, function, which lags furthest behind in the process of differentiation. He also writes on the development of functions, the process he calls individuation. Related to differentiation is the idea of psychic energy, which determines the intensity of the workings of the psyche. Each of these concepts will be discussed separately.

Differentiation of Functions

The notion of differentiation of functions is not easy to understand. While Jung is clear and definite on some aspects of the concept, he is less clear, and at times contradictory, on others. Basically, differentiation means the separation of one or more functions from the collective psyche. Conversely, lack of differentiation means the fusion or merging of functions with one another. When two functions are continually mixed up, when they do not exist separately, each in its own right, the situation incessantly leads to ambivalences and opposed tendencies, inhibitions and irrelevancies, lack of direction or poor guidance. For example, when feeling and thinking, or sensing and intuition, are of equal strength, they both try to exert power over consciousness. This indicates that both functions are relatively undeveloped and undifferentiated, regardless of whether they are consciously directed or unconsciously followed. When people are undifferentiated, their personalities disappear "beneath the wrappings of collectivity" (10). To discover the nature and scope of their own personalities and individual characters, people have to free themselves from collective opinion. If we are only collective, Jung writes, we are no longer distinct individuals, but simply species, estranged from ourselves.

When the mechanism of extraversion predominates, Jung states, "the most differentiated function is always employed in an extraverted way, whereas the inferior functions are introverted" (340). The reverse also holds true. When the mechanism of introversion predominates, the most differentiated function is employed in an introverted way, whereas the inferior functions are extraverted. While the less differentiated functions of the extravert "show a highly subjective coloring with pronounced egocentricity and personal bias" (341), those of the introvert are outward-directed, in all their imperfections.

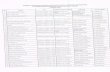

An illustration may be helpful. Consider Figure 1. It shows the personality profile of Jane Smith. The upper "box" contains the two judgmental functions, thinking and feeling, while the lower box contains the two perceptive functions, sensing and intuition. The four extraverted functions are displayed on the left side, the four introverted functions on the right. We will refer to Jane's profile throughout the sections that follow.

19

-

Figure 1: Personality Profile of Jane Smith

Dominant Function

Experience shows, Jung says, "that the basic psychological functions seldom or never all have the same strength or degree of development in the same individual" (346). One of the functions is likely to dominate, in both strength and development.

In Jane's case, the dominant function is intuition. Intuition has the longest bar overall, a good measure of the strength of a function, and the longest of the four bars on the extraverted side. Jane would therefore be considered an EN. As one can see from the profile, Jane is neither strongly extraverted nor introverted. Two of the four functions have longer bars on the introverted side (IT and IF). Only intuition is predominantly extraverted.

Jung regards voluntary differentiation, "a conscious capacity for one-sidedness ... [as] a sign of the highest culture" (207). For one thing, it allows people intentionally to keep out of the way of their inferior functions. Thus a person who has only sensing dominant would consciously abstain from making predictions about the future, a strength of the intuitive, but would instead suggest alternatives to problems firmly rooted in experience. For another thing, people who identify with one function can also deliberately invest it with all the psychic energy they have at their disposal.

20

-

By implication, this means that, when they do so, the other functions will be starved of energy and "gradually sink below the threshold of consciousness, lose their associative connection with it, and finally lapse into the unconscious" (298). Here they regress, becoming infantile and archaic. When they become activated while in this state, they disturb the directed dominant function and bring about a state of personality dissociation.

However, having a dominant function is by no means always beneficial or desirable. If a dominant function is not voluntary, not conscious, not under the control of a person's will, it is what Jung refers to as an involuntary dominant function. In such a case, the individual identifies with only one function. There is no backup, no secondary function. Jung calls this state compulsive, untamed, uncontrolled, and undomesticated; a one-sided Aquarter psyche:@ "the other three quarters languish in the darkness of repression and inferiority" (100). People who meet this definition "barbarously" overvalue their one function and consider themselves highly differentiated. Yet they are actually in a collective state, in that they conform to collective demands and general expectations, lacking the ability to be anything but one-sided.

Auxiliary Function

Jung states that "besides the most differentiated function, another, less differentiated function of auxiliary importance is invariably present in consciousness and exerts a co-determining influence" (405). This means that the auxiliary function, like the dominant one, is consciously under the control of the will and thus able to orient a person. In such an instance, it has clear aims, allowing it to guide and motivate action.

In Jane's case, judging by the length of the bars, the auxiliary function is thinking. Since her thinking is more introverted than extraverted, her auxiliary function is IT. This means that she can "check out", think through, possibilities she sees "out there" in the world. Her IT function would allow her to detect meaning and significance for herself; her ET function would help her to explain her vision logically to others.

Although the auxiliary function complements the dominant function, it is always different from it, Jung states, and never opposes it. Thus feeling cannot be an auxiliary function to thinking; only sensing or intuition can. Rational judgmental functions, therefore, pair with irrational perceptive ones. Nevertheless, Jung makes it quite clear that the auxiliary function can never be as important, reliable, or decisive as the dominant one. If the auxiliary function should reach the level of the dominant, the judgmental and perceptive character of the two functions would simultaneously vie for attention, resulting in lack of differentiation. Thus "the auxiliary function is possible and useful only insofar as it serves the dominant function" (406). Undifferentiated Functions

While the dominant and auxiliary functions are under intentional control and represent an expression of our conscious personality, the less differentiated functions are, at least partially, unconscious. They always have some measure of consciousness attached to them, and aid conscious personality--its aims, will and performance--to some extent, Jung writes. Only the

21

-

inferior function remains barely conscious, particularly if the dominant function is really dominant and retains a small share of available psychic energy.

In Jane's case, ET, IN, and IF are somewhat pronounced, thus somewhat conscious. Indeed, ET can be considered an auxiliary function to EN on the extraverted side, since it is clearly differentiated from EF and ES, both of which are relatively undeveloped. On the introverted side, IF and IN are almost of equal strength. They are both somewhat conscious, and will vie for attention in assisting IT, the dominating introverted function. Sensing is clearly the least preferred function; it has the shortest bar and is undeveloped in the introverted and extraverted attitude. This means that the two descriptions of the ES and IS given earlier will not apply to Jane--they define what Jane is not. Sensing is her weakness.

Jung links differentiation to consciousness and intent, and lack of differentiation to unconsciousness and spontaneity: "the unconscious...is a neutral region of the psyche where everything that is divided and antagonistic in consciousness flows together into groupings and configurations" (113). This material constantly surfaces into consciousness "to such a degree that at times it is hard for the observer to decide which character traits belong to the conscious and which to the unconscious personality" (341). By contrast, "conscious contents can become unconscious through loss of their energic value" (484); this process leads to forgetfulness and fading memories.

Psychic Energy

Why is it, Jung asks, that the dominating function is intense in one person and rather weak in another? The answer he attributes to libido, or psychic energy: "the intensity of the dominant function seems to me to be directly dependent on the degree of tension in the propensity to act" (287). The higher the psychic tension, the more energy can flow into the dominant function.

High psychic energy can thus result in a highly charged dominant function. Put differently, the intensity of the dominant function depends on the amount of accumulated, disposable libido. This does not mean that the output of this function is always of positive value, a point worth remembering. Differentiated thinking, for example, may well be superficial and shallow. Nor is the energy produced by the functions, but rather by the attitudes. Attitudes energize functions.

Jung is specific about the effect of energy on attitudes. Introversion is generally characterized by an intense dominant function, he contends, and by a correspondingly long auxiliary function. In contrast, extraversion is characterized by a more relaxed, and therefore weaker, dominant function and a correspondingly short auxiliary function. As with all energy, psychic tension eventually lessens: "when with increasing fatigue the tension slackens, distractibility and superficiality of association appear...a condition characterized by a weak dominant and a short auxiliary function" (287).

In terms of psychic energy, Jane=s profile is difficult to interpret. It is possible that her dominant function, EN, is not very intense, and that her auxiliary function, IT, is short. Still, as mentioned

22

-

above,, it is not clear whether Jane should be classified as an extravert simply because her dominant function is oriented that way. Overall, her profile looks rather balanced between the two attitudes. It could well be that her IT function is rather intense. Also, as mentioned, the profile itself gives little indication of the quality of the conscious functions. Jane could be a highly successful stockbroker, sniffing out and betting on the future after carefully checking out the logic and reasoning behind her visions. Her intuition could also be restricted to more mundane things, like the weather or news, and her thinking to more trivial pursuits, like organizing her day=s activities.

Libido therefore divides into two streams, which alternately flow inward or outward. At times, the outward stream opposes the inward and conflict results. The two impulses are difficult to govern because of their overwhelming power. Jung calls a person cultured when he can tame the libido "to the point where he can follow its introverting or extraverting movement of his own free will and intention" (208). The taming process thus involves the will: "I regard the will as the amount of psychic energy at the disposal of consciousness" (486). When the will is not brought to bear and the psychic process is conditioned by unconscious motivation, Jung writes, an uncultured, primitive mentality results.

Development of Functions

Development of functions should proceed by way of one auxiliary function; for instance, "in case of the rational type via one of the irrational functions" (407). It is useless to develop the inferior function, the opposite of the dominant function, Jung states, because this process would involve "too great a violation of the conscious standpoint" (407). Thus a thinking type should work on developing either the sensing or the intuitive function, but not the feeling one.

It strikes us that all extraverts would have to go against their stream of psychic energy in trying to develop their introverted function. The more pronounced their extraversion, the more they would dislike the process of developing an inner function. It may be more logical, and may make intuitively more sense, to develop an auxiliary function for the same mechanism. Extraverts with a rational dominant function (thinking or feeling) should develop an auxiliary irrational extraverted function (sensing or intuition). Similarly, introverts should develop an auxiliary introverted function. This does not mean that the opposite attitude should not also be developed. It would be particularly useful for introverts, who, after all, have to orient themselves in the external world.

Jane may therefore want to develop both thinking functions. The tertiary and least preferred functions, however, are more difficult to develop. Her EF, ES and IS functions are all less preferred. According to Jung, there is not much that someone like Jane can do to develop them, although she might work out a set of elementary skills to compensate for their lack of development. For example, Jane can learn some basic Arules of etiquette@ for her low EF function, and become more aware of how she makes use of her five senses.

23

-

Individuation

Jung defines Individuation as "the process by which individual beings are formed and differentiated" (448). It is the impulse or urge toward uniqueness and self-realization, the process of consciously "coming to terms with one's own inner center (psychic nucleus) or Self" (166). This imperceptible process of psychic growth, Jung claims, leads to a wider and more mature personality and to increased personal effectiveness.

In terms of type, individuation is a process whereby the functions are differentiated. Improving and fine-tuning the dominant function, peeling away an auxiliary function, or developing a tertiary function would be examples of individuation. In this sense, individuation is personality development through type.

Every individual is also partly collective in nature. The collective norm is made up of the totality of individual ways. Thus no individual standpoint can ever be completely antagonistic to the collective social norm, since it is part of that norm-- only differently oriented. Therefore, says Jung, individuals should try to remain distinct and separate from the norm on the one hand, and continue to be oriented toward social norms on the other hand.

Achieving a balance between the development of one=s individual character and a social personality is not easy. If someone is too far removed from social norms, she can become isolated; if her behavior completely conforms with those norms, she ceases to exist as an individual. Before a person embarks on the process of individuation, Jung writes, she must first become adapted to the necessary minimum of collective norms.

Typing

Jung acknowledges that his descriptions of types are somewhat terse, and not always understandable on first reading. In addition, he admits, "No one, I trust, will draw the conclusion from my description...that I believe the four or eight types here presented to be the only ones that exist." Nevertheless, Jung insists that "it would be difficult to adduce evidence against the existence of psychological types." (489-90) He stresses that his typology is the product of many years of practical experience, not an outcome of Aundisturbed hours in the study@ (xiii). Each sentence, he says, has been tested a hundredfold in practice.

"My typology,@ Jung writes, does not "stick labels on people on first sight," a practice he believes to be nothing but a childish game. Rather, it deals "with the organization and delimitation of psychic processes that can be shown to be typical" (xv). Because typology is derived from individual behavior, Jung continues, it touches on personal and intimate matters, and is therefore contradictory. He claims that the great diversity of individual psychic dispositions he encountered in the course of his professional practice made him aware of a Aneed [to establish] some kind of order among the chaotic multiplicity of points of view" (xiv).

24

-

Jungs typology is one of many possible ways of viewing life, a small contribution to the almost infinite variations and gradations of individual psychology. Yet Jung is convinced that a thorough understanding of type helps people settle conflicts, comprehend other standpoints, and free themselves from their own type. Given the fact that, as he puts it, "people are virtually incapable of understanding and accepting any point of view other than their own, knowledge of type enables them to become conscious of their own partiality and abstain from "heaping abuse, suspicion, and indignity upon [their] opponent" (489).

As we see it, the initial challenge lies in gaining a solid understanding of type theory and observing type in action. When one uses type theory as a focus, as a way of looking at people, its power gradually reveals itself.

References

Cranton, P. (1998). Personal Empowerment through Type. Sneedville, TN: Psychological Type Press.

Cranton, P. (Ed.) (1998). Psychological type in action. Sneedville, TN: Psychological Type Press.

Jung, C. (1971). Psychological types. Princeton: Princeton University Press. (originally published in 1921.)

Jung, C. (Ed.). (1964). Man and his symbols. New York: Doubleday.

Keirsey, D., & Bates, M. (1984). Please understand me: Character and temperament types. Del Mar, CA: Prometheus Nemesis Books.

Myers, I. B. (1985). Gifts differing. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Sharp, D. (1987). Personality types: Jung's model of typology. Toronto: Inner City Books.

25

Jungs Psychological TypesAttitudes and FunctionsExtraversionIntroversionTwo MechanismsPsychic FunctionsPsychological Types

Rational Judgmental TypesIrrational Perceptive TypesDifferentiation

Differentiation of FunctionsDominant FunctionAuxiliary FunctionPsychic EnergyDevelopment of FunctionsIndividuationTypingReferences

Related Documents

![Regulacioni Ventili [VENR]termoventsc.rs/srpski/wp-content/uploads/A-02-VENR-SR-V170614-R00-.pdf · Regulacioni ventili PN 16 / PN 25 / PN 40 PN 63 / PN 100 / PN 160 Ugradne dužine](https://static.cupdf.com/doc/110x72/5e3c81c907082c693464c9eb/regulacioni-ventili-venr-regulacioni-ventili-pn-16-pn-25-pn-40-pn-63-pn.jpg)