Inhalt Peter Scholz/Dirk Wiegandt Zur Einführung 1 Wolfgang Orth Das griechische Gymnasion im römischen Urteil 11 Christian Mann Gymnasien und Gymnastikdiskurs im kaiserzeitlichen Rom 25 Martin Hose Die Sophisten und das Gymnasium – Überlegungen zu einer Nicht- Begegnung 47 Dennis P. Kehoe Das kaiserzeitliche Gymnasion, Bildung und Wirtschaft im Römischen Reich 63 Peter Scholz Städtische Honoratiorenherrschaft und Gymnasiarchie in der Kaiserzeit 79 Lucia DʼAmore Culto delle Muse e agoni musicali in età imperiale 97 Angelos Chaniotis Das kaiserzeitliche Gymnasion in Aphrodisias 111 Boris Dreyer Eine Landstadt am Puls der Zeit – Neue Inschriſten zum Gymnasion und zum Bad aus Metropolis in Ionien 133 Frank Daubner Gymnasien und Gymnasiarchen in den syrischen Provinzen und in Arabien 149 Monika Trümper Modernization and change of function of Hellenistic gymnasia in the Imperial period: Case-studies Pergamon, Miletus, and Priene 167 Martin Steskal Römische Thermen und griechische Gymnasien: Ephesos und Milet im Spiegel ihrer Bad-Gymnasien 223

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

InhaltPeter ScholzDirk WiegandtZur Einfuumlhrung 1

Wolfgang OrthDas griechische Gymnasion im roumlmischen Urteil 11

Christian MannGymnasien und Gymnastikdiskurs im kaiserzeitlichen Rom 25

Martin HoseDie Sophisten und das Gymnasium ndash Uumlberlegungen zu einer Nicht-Begegnung 47

Dennis P KehoeDas kaiserzeitliche Gymnasion Bildung und Wirtschaft im Roumlmischen Reich 63

Peter ScholzStaumldtische Honoratiorenherrschaft und Gymnasiarchie in der Kaiserzeit 79

Lucia DʼAmoreCulto delle Muse e agoni musicali in etagrave imperiale 97

Angelos ChaniotisDas kaiserzeitliche Gymnasion in Aphrodisias 111

Boris DreyerEine Landstadt am Puls der Zeit ndash Neue Inschriften zum Gymnasion und zum Bad aus Metropolis in Ionien 133

Frank DaubnerGymnasien und Gymnasiarchen in den syrischen Provinzen und in Arabien 149

Monika TruumlmperModernization and change of function of Hellenistic gymnasia in the Imperial period Case-studies Pergamon Miletus and Priene 167

Martin SteskalRoumlmische Thermen und griechische Gymnasien Ephesos und Milet im Spiegel ihrer Bad-Gymnasien 223

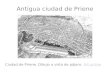

Monika TruumlmperModernization and change of function of Hellenistic gymnasia in the Imperial period Case-studies Pergamon Miletus and PrieneFrom an archaeological point of view the aim of this conference ndash to examine the change and extension of the functions of gymnasia in the Imperial period and their interrelation with changes in the socio-political context ndash can be assessed in two dif-ferent methodological ways First the development of gymnasia can be analyzed by looking at gymnasia that were built in the Late Classical or Hellenistic period and con-tinued to be used in the Imperial period Second Late Classical or Hellenistic gymna-sia whose design and decoration can be safely reconstructed can be compared with gymnasia that were built in the Imperial period namely the so-called bath-gymnasia in the eastern Mediterranean It might be additionally revealing to compare the newly built gymnasia of the Imperial period with the older Late Classical and Hellenistic gymnasia still used in the Imperial period and to assess the similarities and differ-ences between these two groups This should show whether the remodeling processes and new building projects were characterized by the same aims and trends whether the new gymnasia served as models and references for the remodeling processes of the old gymnasia and which aims and preferences distinguished the remodeling pro-jects that necessarily required compromise and could only be carried out on a limited scale Here the first methodology is followed and the alterations and possible func-tional changes of Late Classical and Hellenistic gymnasia in the Imperial period are analyzed in three case studies the gymnasia of Pergamon Miletus and Priene1 Due

1enspI would like to thank the conference organizers Hartmut Leppin and Peter Scholz for inviting me to this very stimulating and interesting conference and for their hospitality I am also very grateful to the other participants at the conference for comments and discussions and to Elizabeth Robinson for improving my English text I owe a special debt to Ralf von den Hoff Verena Stappmanns and Wulf Raeck who critically read the original manuscript offered astute suggestions and comments and generously discussed their recent research in Pergamon and Priene with me Ralf von den Hoff also kindly allowed me to read and cite his article on Hellenistic gymnasia (now von den Hoff 2009b forthcoming however when I wrote this paper) and Verena Stappmanns kindly provided me with a high quality plan of the Pergamenian gymnasion All remaining errors are my own This paper was written and submitted in July of 2008 While it was attempted to integrate the most important research and literature published between July of 2008 and September of 2014 for the gymnasia of Pergamon Miletus and Priene this could not be done systematically for all aspects and topics that may be relevant for this paper (e g for these three cities beyond their gymnasia for gymnasia in general or for the much discussed importance and development of Greek culture athletics institutions and urban landscapes in the Roman Imperial period) Of two new comprehensive studies on the Greek gymnasion Skaltsa 2008 was not available to me and Trombetti 2013 focuses on

168emsp emspMonika Truumlmper

to the limited space comparisons with new buildings of the Imperial period must be restricted to a few select features and examples So far the history of Greek gymnasia in the Imperial period has hardly been studied neither for individual buildings nor on a more comprehensive comparative level for several or even all examples2 This paper is a first attempt to fill this gap but due to the incomplete state of research in many respects it can only offer preliminary results and suggestions for further research It will show that from an archaeological point of view neither the idea of a general decline of the gymnasion building type particularly in terms of its athletic function3 nor the notion of an omnipresent continuity and vitality of athletic activity can be sustained4 Instead different cities adopted diverse strategies in dealing with the heritage of their athletic buildings and each city has to be studied individually before possible larger trends can be reconstructed

In the following after a brief summary of the main characteristics and innovative features of Hellenistic and particularly Late Hellenistic gymnasia the gymnasion of Pergamon is discussed in detail because it is the best example to examine the above-mentioned question This is succeeded by a much shorter analysis of two buildings that are less well preserved and published namely the so-called Hellenistic gymna-sion of Miletus and the upper gymnasion of Priene and by comparative conclusions My considerations are mainly based on relevant literature and on short visits to the three sites in 2007 I have examined only the Hellenistic gymnasia and particularly their bathing facilities in more detail but not the gymnasia of the Imperial period5

cultic aspects of gymnasia of the 6th to 1st century BC that are located in central Greece and on the Cycladic islandsFor an assessment of the bath-gymnasia that were newly built in the Imperial period see M Steskalrsquos contribution in this volume and also Steskal 2003a Steskal 2003b Steskal 2007 Steskal 2008 Yeguumll 1986 Yeguumll 1992 250-313 414-423 Nielsen 1990 I 105-1082ensp Delormersquos study Delorme 1960 ends at the beginning of the Augustan period only a few pages 243-250 (bdquoLa disparition drsquoun type de monumentldquo) are dedicated to a brief summary of the development of the gymnasion in the Imperial period See also Yeguumll 1992 21-24 Glass 1967 discusses the history of a few selected buildings but attempts no comprehensive assessment of changes in the Imperial period - For individual examples see below3enspThis was particularly popular in older publications see Newby 2005 10 note 33 229-271 278 citing older literature Steskal 2003a and 2003b argues that at least the palaistrai of bath-gymnasia saw a shift from a mixed athletic-intellectual towards an exclusively educational-intellectual-cultural function which however would not necessarily entail a general decline or abandonment of athletic activities just their relocation into other facilities4enspMost recently fervently supported by Newby 2005 passim also citing other advocates of this more recently adopted view5enspFor comprehensive studies on Greek bathing culture see Truumlmper 2006 Truumlmper 2008 258-275 Truumlmper 2009 LucoreTruumlmper 2013 Truumlmper 2014

Modernization and change of function of Hellenistic gymnasia emsp emsp169

Characteristics of (Late) Hellenistic gymnasiaAlthough both the design and equipment of Late Hellenistic gymnasia were clearly influenced by their regional socio-cultural context many buildings were also shaped by three general innovative trends 1 A new importance and quality of multifunctional rooms for assemblies and

sojourns These rooms were located in the palaistra-complexes of gymnasia andwere often designed as exedrae6 They were often combined with lavish monu-mental entrances propyla which were preferably placed opposite the largest and most luxurious rooms

2 A new quality of decoration recently discussed especially by Henner von Hesberg and Ralf von den Hoff7

3 A new quality of bathing facilities that has been largely underestimated or evenignored so far although this is a feature that is not only archaeologically welldocumented but also by far the most important factor for the development ofgymnasia in the Imperial period8 While the Late Classical and early Hellenisticgymnasia (4th3rd centuries BC) had only been provided with ascetic facilities forcleansing with cold water mostly basins for ablutions and rarely pools for immer-sion several gymnasia of the 2nd and 1st centuries BC were equipped with relax-ing warm bathing forms These include large round sweat baths found in five orsix sports facilities9 and rectangular sweat rooms in two or three cases10 Sweat

6enspVon Hesberg 1995 Wacker 1996 passim von den Hoff 2009b - For the problematic terminological differentiation of palaistra and gymnasion see most recently Mango 2003 18-19 which is followed here A palaistra included a central courtyard with surrounding rooms had no facilities for running and could exist as an independent building but also form part of a gymnasion In contrast to this a gymnasion comprised next to a palaistra also facilities for running as well as javelin and discus throwing (dromos paradromis xystos stadion) - If however the denomination gymnasion is commonly applied in literature to buildings that are according to this definition palaistrai it will also be used here to avoid confusion (see below for the examples in Miletus and Priene)7enspVon Hesberg 1995 von den Hoff 2004 see also Martini 20048enspThe development and significance of bathing facilities in Late Hellenistic gymnasia is partly recognized in Delorme 1960 301-315 and especially in Yeguumll 1992 17-24 but not to its full extent Glass 1967 esp 247-269 failed to notice any development of bathing facilities in gymnasia Von Hesberg 1995 in his overall excellent assessment of Late Hellenistic gymnasia pays no attention to the bathing facilities9enspGymnasia of Aiuml Khanoum (third phase identification of the gymnasion and the sweat bath not secure) Akrai Assos Eretria Solunto and Thera for a more detailed discussion and literature see Truumlmper 2008 258-275 table 3 10enspDelos so-called Gymnasium and Lake Palaestra possibly Pergamon gymnasion - The precise function of the two Delian bathrooms currently cannot be safely reconstructed but both were vaulted and served most likely for some warm bathing form (certainly without water in the Gymnasium possibly with water in the Lake Palaestra) see Truumlmper 2008 251-255 Truumlmper in preparation For the gymnasion of Pergamon see below

whose identification as a palaistra is debated at least for its last phase of use

170emsp emspMonika Truumlmper

bathing and the other relaxing warm bathing forms that were all introduced in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC and were also installed in public bath buildings and domestic architecture all over the Mediterranean required heat and time this in turn entailed an advanced technology and a certain monetary expense in order to provide the necessary heat and a socially accepted endorsement of leisure pleasure and indulgence Furthermore because of the expense to heat them sweat baths were most likely used exclusively for collective bathing at specific times in contrast cold water bathing facilities could easily have been used indi-vidually at any time

This development of bathing culture must have revolutionized the bathing experi-ence particularly in gymnasia which before had not even been provided with warm cleansing bathing forms By far the largest sweat baths of the Hellenistic Mediter-ranean world were installed in gymnasia and they most likely could accommodate more athletes at a time than the often simple and small loutra with basins for cold water ablutions This means that bathing gained enormous significance in gymnasia as a collective experience and social activity The wide distribution of rectangular and especially round sweat baths all over the Mediterranean speaks against identifying this new bathing form as a Roman invention as has occasionally been proposed instead it is an achievement of the Hellenistic koine11 The new bathing standard of (some) Late Hellenistic gymnasia12 is probably reflected in Vitruviusrsquo description of an ideal Greek gymnasion which included in the corners of its northern suite of rooms two areas that were physically clearly separated on one side a traditional loutron for cold water ablutions and on the other an extended suite with various warm bathing forms among them especially sweat baths The bath suite in Vitruviusrsquo gymnasion is much larger and more sophisticated than the single sweat rooms in the preserved Late Hellenistic gymnasia and resembles a fusion of a Greek gymnasion and a Late Republican or early Augustan Roman-style bath but it might still mirror the change of attitude towards communal hot bathing in Late Hellenistic gymnasia13

11enspFor the development of bathing culture in the Hellenistic period see in more detail Truumlmper 2006 Truumlmper 2008 258-275 Truumlmper 2009 LucoreTruumlmper 2013 Truumlmper 2014 211ndash21212enspIt has to be emphasized that innovative relaxing bathing did not (yet) become standard for gymnasia in the Late Hellenistic period many prominent examples such as the gymnasia of Am-phipolis Delphi Miletus Olympia Priene (lower gymnasion) Samos and Sikyon did not include a sweat bath in the Hellenistic period see also below note 12613enspVitruvius V 11 - The exact reconstruction of Vitruivusrsquo gymnasion and its possible model(s) is debated and cannot be discussed here for some reconstructions see Delorme 1960 489-497 figs 67-68 Yeguumll 1992 14-17 fig 13 RowlandNoble Howe 1999 fig 88 See also Wacker 2004 who - wrongly - considers the sweat bath laconicum as atypical for Greek gymnasia and (unconvincingly) proposes that Agripparsquos laconicum in Rome served as model for Vitruviusrsquo description of a Greek gymnasion

Modernization and change of function of Hellenistic gymnasia emsp emsp171

All three innovative traits of Late Hellenistic gymnasia were highly significant for the development of this building-type in the Imperial period They paved the way both physically as well as conceptually for a new perception and design of gymna-sia in the Imperial period particularly in the eastern Mediterranean This is espe-cially true with regard to the bathing facilities that under the influence of Roman culture and Roman technological achievements were continuously extended and improved upon to the point that they dominated the whole complex New features in the bathing facilities of Imperial gymnasia were above all the systematic use of sophisticated heating systems (hypocausts and tubuli) and the integration of the hot water bath for reasons of clarity and simplicity such installations are referred to in the following as Roman-style bathing facilities In opposition to this the cold water installations and the large sweat baths of Late Hellenistic gymnasia which were still heated with simple heat sources such as hot stones and braziers are identified as Greek-style bathing facilities14

The transition from the Hellenistic to the Imperial gymnasion and the develop-ment of the gymnasion in the Imperial period can best be analyzed currently for the gymnasion of Pergamon For many other buildings even those recently discussed in monographs their use in the Imperial period and particularly the date and form of their final abandonment are unknown as some examples may illustrate

ndash The history of the gymnasion in Olympia was recently studied by Christian Wacker who dates the latest remodeling process namely the addition of a pro-pylon to room XV to the second half of the 1st century AD The gymnasion was gradually overbuilt by residential and industrial structures in late antiquity from the 4th century AD onwards at the latest How long this building was used as a gymnasion however remains uncertain15

ndash The gymnasion of Amphipolis is not yet fully published but its history can be roughly reconstructed from preliminary reports It saw extensive remodeling in the Imperial period including the addition of a lavish propylon the construc-tion of a building and water basin between palaistra and xystos the installation probably of a second loutron in the palaistra and other repairs16 Its period of use and the date of its final abandonment are not (yet) known

14enspFor the differentiation of Greek- versus Roman-style bathing see in more detail Truumlmper 2009 - Hypocaust systems were developed in the 3rd century BC in the western Mediterranean but were only used in the 2nd century BC for a few round sweat baths that were all included in public bath buildings and which were remarkably small with diameters of about 220 to 350 m as opposed to the 590-1020 m diameters in round sweat baths of safely identified gymnasia 15enspWacker 1996 23-56 esp 52-56 the gymnasion was built in the first half of the 3rd century BC and extended and remodeled in the 2nd and 1st centuries BC16enspSummary in Wacker 1996 141-144 Koukouli-Chrysanthaki 2002 57 note 5 the palaistra was built in the 4th century BC and the xystos added about a century later the building phases of the

172emsp emspMonika Truumlmper

ndash Stratigraphic excavations date the final destruction of the north gymnasion (or rather palaistra) in Eretria to the first half of the 2nd century AD17 The majority of sculptural fragments found in the building and the renewal of the roofing of the round sweat bath are dated to the Imperial period this shows that the building was still actively used and maintained until its destruction18

ndash Repairs to the exedra and colonnades in the Hellenistic gymnasion of Stratonikeia are dated to the Julio-Claudian through Antonine periods based on an inscrip-tion and above all a stylistic analysis of the architectural elements19 How long the gymnasion was used as such is unknown but several building projects in the city such as the construction of a monumental gateway with a nymphaion and repairs to the stage building of the theater can be dated to the Severan period20

This list could easily be continued and would yield mainly fragmentary or negative results This also holds true with significant nuances for the three case studies that will now be examined in more detail

The gymnasion of Pergamon The gymnasion of Pergamon was published by Paul Schazmann in 192321 Although excellent for its period this publication is insufficient by modern standards This is especially true in terms of the question examined here namely the exploration and reconstruction of the original Hellenistic building that was massively altered by remo-deling processes in the Imperial period Marianne Mathys Verena Stappmanns and Ralf von den Hoff have recently carried out a research project that aims to fill this serious lacuna by focusing on the design and decoration of the Hellenistic building The research campaigns included a new examination of the architecture sondages in various rooms of the upper terrace and an investigation of the epigraphic evidence and the sculptural decoration22 These campaigns have shown that the Hellenistic

Imperial period are not dated more precisely but an important inscription (gymnasion law) was set up in 2322 BC17enspMango 2003 49-69 esp 66-67 the gymnasion was built in the years around 300 BC and remodeled in the period of about 150-100 BC18enspMango 2003 91-97 102-116 19enspMert 1999 40-42 215-227 the gymnasion was constructed in the second quarter of the 2nd century BC20enspMert 1999 43-4821enspSchazmann 192322enspvon den Hoff 2004 Pirson 2006 68-72 75 von den Hoff 2007 von den Hoff 2008 von den Hoff 2009a Mathys 2009 Mathys 2011 Mathys 2012 Mathysvon den Hoff 2011 MathysStappmannsvon den Hoff 2012 Stappmanns 2011 Stappmanns 2012 The final monographic publication of this large research project has not yet appeared

Modernization and change of function of Hellenistic gymnasia emsp emsp173

gymnasion is far less securely known than previously thought and that alterations in the Imperial period were far more dramatic than hitherto assumed and reconstructed This severely affects all attempts to analyze the possible changes of function and use of this building from its origins through the Imperial period Since the recent research project focused on the Hellenistic period and its final results have no yet been pub-lished the following discussion is particularly for the Imperial period still based mainly on the earlier partially outdated literature and all considerations and results are necessarily preliminary23

The gymnasion of Pergamon was one of the largest gymnasia of the Hellenistic world24 Its construction is commonly dated to the reign of Eumenes II who initi-ated a major remodeling and extension of the city The location of the gymnasion on the steep sbquoBurgberglsquo of Pergamon required the construction of three terraces that are connected to the urban street system by several staircase-systems (fig 1) The visible remains result from a long multi-phased building process that extended over at least five centuries from the 2nd century BC through the 3rd century AD (or later) A brief description shall show whether or not the functions of the various terraces and struc-tures in their currently visible state that is their last state of use can be determined This is followed by a discussion of what can be stated about the original design and function of the gymnasion as well as major later changes25

All three terraces are centered on or even dominated by unpaved open areas (figs 1 2) While both the peristyle courtyard (palaistra) and the terrain over rooms 20ndash60(paradromis) on the upper terrace were most likely used for athletic purposes because of their shape and proximity to significant features such as bathing facilities and a

23enspThe best brief description of the building and summary of research up to 1999 is given by Radt 1999 113-134 344 For research up to 2004 see von den Hoff 2004 382-391 For research on the Hellenistic gymnasion see previous note24enspThere is no consensus regarding the size of this gymnasion which is difficult to measure because of the irregularity and different extension of its three terraces Schazmann 1923 3-6 upper terrace 150 x 70 m middle terrace 250 x 70 m Delorme 1960 378-379 note 7 6630 m2 (only upper terrace) MartiniSteckner 1984 91 25000 m2 Mert 1999 125-126 tab 3-4 28600 m2 Radt 1999 115-116 upper terrace 210 x 80 m middle terrace 150 x 40 m lower terrace 75 x 10-25 m = 2411250 m2 von den Hoff 2009b for the Hellenistic gymnasion upper terrace (including area over the sbquoKellerstadionlsquo and rooms 20-60) c 10200 m2 middle terrace c 5500 m2 lower terrace c 1000 m2 = c 16700 m2 - For a comparison of sizes of gymnasia see Delorme 1960 378-379 note 7 which however does not yet include large examples such as the gymnasia of Samos Rhodos (Ptolemaion) and Stratonikeia for these see Mert 1999 126 tab 4 see also von den Hoff 2009b passim 25enspThis description is entirely focused on the reconstruction of possible functions and is largely based on Radt 1999 113-134 only in cases of doubt and debate will other literature be cited in addition For much more comprehensive descriptions of the remains see Schazmann 1923 Delorme 1960 171-191 Glass 1967 154-174 Radt 1999 113-134 for the Hellenistic gymnasion see also von den Hoff 2009b Stappmanns 2011 Stappmanns 2012 MathysStappmannsvon den Hoff 2012

t

174emsp emspMonika Truumlmper

Fig 1 Pergamon gymnasion plan Schazmann 1923 pl IVndashV

Modernization and change of function of Hellenistic gymnasia emsp emsp175

Fig 2 Pergamon gymnasion hypothetical functional plan of the building in its last stage of use M Truumlmper after Radt 1999 fig 29

176emsp emspMonika Truumlmper

possible stoa over the sbquoKellerstadionlsquo (xystos) the function of the open terrain on the middle and lower terraces cannot safely be determined Both also could have served for athletic training but other activities such as assemblies festivities cultic proces-sions or agreeable strolls in a possibly planted park-like setting are also conceivable Ultimately all uncovered areas were most likely used flexibly according to need albeit possibly with a more pronounced athletic function on the upper and a more distinct cultic function on the middle terrace26 According to epigraphic and archa-eological evidence all of the terraces were also decorated with various monuments such as honorific statues votives and inscribed stelai

It is equally difficult to determine a precise function of the covered space that is the rooms and buildings most of which also seem to have been multifunctional The easiest to identify are the bathing facilities which are all located on the upper terrace and include the Greek-style loutron L and two Roman-style baths to the west and east of the peristyle-complex respectively27 A temple with an altar on the middle terrace and at least one room (57) or even several rooms (52ndash57) related to it served cultic pur-poses Another larger temple (R) is located on a separate terrace high above the upper terrace and is commonly identified as the main temple of the gymnasion because lists of ephebes were engraved on its walls however it was accessed not from the

26enspThe use of the lower terrace which includes only a square building of unknown function is most difficult to imagine Cf now Stappmanns 2011 32 MathysStappmannsvon den Hoff 2012 271 Stappmanns 2012 23727enspFor the west and east baths see below Room L has a doorway 188 m in width was paved with stone slabs decorated with a red probably waterproof stucco and provided with a niche in its west wall from which water was distributed into basins on the west north and south walls of these seven marble basins on high supports and two foot basins of trachyte are still visible on the north and south walls Schazmann 1923 pl IV-V shows the two foot basins in the northeast corner at a certain distance from the walls today they are located on the eastern end of the north wall as also described in the text Schazmann 1923 65 The other structures in the center of this room foundations for statues or the like and five large pithoi shown on Schazmann 1923 pl IV-V and described in Schazmann 1923 65 are no longer visible - Several fixtures for the adduction of water were found under the floor of the room and to its west and an opening for the drainage of waste water was discovered in the southwest corner recent research von den Hoff 2009a 163-164 figs 35-37 showed that the original loutron most likely was not yet provided with running water the fountain niche in the west wall which was supplied by a terracotta pipe system running under the floor belongs to a second phase and saw a remodeling in a third phase - While Schazmann 1923 63-64 does not describe the doorway at all later authors assume that the door was lockable Delorme 1960 177 bdquo(hellip) L nrsquoouvre que par un une porte agrave vantail de bois (hellip)ldquo Glass 1967 166 bdquoThe entrance was closed with locking double doors (hellip)ldquo Radt 1999 129 bdquoDer Raum (hellip) war mit einer Tuumlr geschlossen also gut gegen Zugluft und Einblick geschuumltzt (hellip)ldquo Today no clearly identifiable threshold is visible in the opening of room L There is only an assemblage of some uncut stones and five roughly cut stones two of the latter which are located in the center of the opening rather than towards its western border as was usual each have a pair of dowel holes The plan Schazmann 1923 pl IV-V shows no threshold and no dowel holes

Modernization and change of function of Hellenistic gymnasia emsp emsp177

gymnasion itself but through an independent entrance from the terrain to the north Although clearly related to the gymnasion this temple was therefore physically and probably also conceptually separate from the gymnasion and the daily activities per-formed there Whether the square building on the lower terrace had a cultic func-tion as cautiously proposed in literature must remain hypothetical28 In addition to the open areas covered space might also have been used for athletic training this especially includes the two-aisled stoa (xystos 194 m long) that was located on the upper floor of a double-storied complex to the north of the middle terrace and the possible stoa (xystos 212 m long) over the sbquoKellerstadionlsquo29 Whether any rooms on the middle and especially on the upper terrace served the same function is unknown but this is rather unlikely because most of them seem to have been paved in their last stage of use30 Some such as exedra D (konisterion31) and room F10 (konisterion or aleipterion32) have still been identified albeit on a tenuous basis and in an overall

28enspRadt 1999 11929enspFor the possible stoa over the sbquoKellerstadionlsquo see below note 36 The stoa of the middle terrace is commonly but not unanimously identified as a running track see Mango 2004 288-289 bdquoEs fragt sich aber ob diese lange Halle wirklich als Laufanlage gedient hat - im ruumlckwaumlrtigen Bereich hinter einer inneren Saumlulenstellung die wegen der Breite der Halle (9 m) fuumlr die Konstruktion des Daches notwendig war koumlnnte eine Reihe von Raumlumen gelegen haben die unter anderem als Bankettraumlume haumltten Verwendung finden koumlnnenldquo This theory however is not substantiated by an analysis of the archaeological evidence it is crucial to discuss for example the problematic relationship of the inner colonnade of the stoa and the south faccedilades of the proposed rooms Recent publications emphasize the cultic function of the middle terrace without discussing the function of this stoa in more detail MathysStappmannsvon den Hoff 2012 271 Stappmanns 2012 237 Stappmanns 2011 33 states briefly for the stoa of the middle terrace bdquoWaumlhrend das Untergeschoss vorwiegend aus geschlossenen Raumlumen bestand wird fuumlr das Obergeschoss eine zweischiffige dorische Halle rekonstruiert Aufgrund ihrer beachtlichen Laumlnge von 197 m sah man in ihr ein Hallenstadionldquo30enspRooms B (mosaic) D (marble slabs) F10 (stone slabs) G (stone slabs) M (south part mosaic)31enspThe konisterion dedicated by Diodoros Pasapros see below notes 54-55 bdquodas zum Bestaumluben des Koumlrpers nach der Salbung dienteldquo Schazmann 1923 54 (citation) followed by Radt 1999 126 and at least in denomination also by Pirson 2006 71 - In contrast to this Delorme 1960 187-188 276-279 identifies the konisterion as bdquopas comme le magasin agrave sable (hellip) mais comme la piegravece sableacutee ougrave lutteurs et pancratiates srsquoentraicircnaient aux eacutepreuves des concours lorsque le temps ne leur permettait pas de le faire au dehors (hellip) Le seul trait que nous puissions affirmer avec certitude est que le sol en eacutetait tregraves meuble et constitueacute de sable finldquo Consequently he locates Diodorosrsquo konisterion and a separate exedra in front of it in the northeast corner of the peristyle courtyard somewhere under the current rooms E-G He is largely followed by Glass 1967 172 who however does not discuss the problems of identification and the different proposed locations at all although p 277 he states that there is currently no way to recognize a konisterion or other rooms apart from a bath and a latrine in the archaeological remains32enspWhile Schazmann 1923 55-56 assumes that the konisterion must have been displaced from room D to room F10 in the Imperial period Radt 1999 126 sees room F as a new Roman konisterion or as the aleipterion that is mentioned in I Pergamon II 466 as a dedication by Titus Claudius Vetus in the Hadrianic period For the aleipterion and its problematic identification in the archaeological

178emsp emspMonika Truumlmper

unconvincing way as rooms related to sports activities For most rooms only criteria such as size location accessibility visibility and decoration can be utilized to assess their importance and possible range of uses On the upper terrace rooms with wide openings and an overall lavish decoration ndash exedrae B D G H K M33 ndash predominate they were all well-lit freely accessible and fully visible a feature that made them inappropriate for activities such as washing that required a more intimate setting Among these exedrae two stand out exedra H because of its central location size and decoration with a niche and the sbquoKaisersaallsquo G with its two apses marble incrus-tation and dedication to the emperors and the fatherland (after AD 161) All of these exedrae could have served multiple mainly non-athletic purposes housing educa-tional-intellectual cultural cultic festive social (banquets assemblies agreeable informal sojourns) and honorific activities Only the odeion J has an architecturally more formally defined function as an auditorium or lecture and assembly hall Fur-thermore rooms A C E and in part also F10 served as access and circulation spaces

It has to be emphasized that most rooms surrounding the peristyle had an upper floor about which little is known Some were obviously also designed as exedrae (e g rooms over K and M) others must have been abandoned in the latest phase of use when the ground floor equivalents received new much higher and vaulted ceilings (e g rooms D E G H and J) Any attempt to determine the function of these upper rooms necessarily remains hypothetical34 Finally some basement and sparsely lit structures certainly had a secondary function and might have been used as service storage or circulation spaces35 These include a long subterranean gallery on the

record see Delorme 1960 301-304 This room certainly served to anoint the body with oil and was probably heated this would definitely exclude the identification of room F10 in Pergamon as an aleipterion Delorme 1960 189 only cautiously locates it somewhere in the east baths For the use and significance of the term aleipterion in the Imperial period see Foss 1975 and especially Pont 2008 The latter argues that aleipterion in the Imperial period designated a lavishly decorated well-lit room that connected both spatially and symbolically athletic and bathing facilities In newly built bath-gymnasia these would have been the central marble halls (sbquoKaisersaumlle) whereas in the gymnasion of Pergamon room F providing a connection between the palaistra and the bath building would qualify as aleipterion Room F a courtyard in reality is neither particularly lavishly decorated however nor did it constitute the only or even main connection between the palaistra and the bath building 33ensp The sbquoexedralsquo K whose opening was relatively narrow in the last phase of use probably served mainly as an access to the odeion J The exedra M was subdivided in its last stage into a larger northern part that served as access to the west baths and a smaller southern room that is decorated with a simple mosaic and was probably designed as an exedra opening off to the south the remains of the so-called sbquoHermeslsquo-exedra that were found in the subterranean gallery S are ascribed to this room the Hellenistic exedra architecture would originally have been set up in another part of the gymnasion and transferred to this place in the Imperial period Schazmann 1923 58 66-6934enspMango 2004 288-289 proposes that the ground floor exedrae and their equivalents in the upper story could temporarily have been used as banquet rooms 35enspFor example rooms 23-33 38-51 on the lower terrace the long two-aisled sparsely lit hall on the lower floor of the complex to the north of the middle terrace

Modernization and change of function of Hellenistic gymnasia emsp emsp179

upper terrace (212 m long sbquoKellerstadionlsquo) whose reconstruction (esp illumination superstructure) and function (running trackxystos technical function as substruc-ture communicationcirculation) were for a long time debated Recent research has shown however that the dimly lit Kellerstadion never served as a xystos but as cir-culation space for easy access to the upper terrace rooms and particularly as substruc-ture and foundation of a stoa that was much more appropriate for use as the covered running track or xystos The large open terrace to the south of this stoa which is supported by a row of rooms (bdquoKammernreiheldquo) to the south of the Kellerstadion is now identified as an uncovered running track or paradromis The existence of both a xystos and a paradromis in the gymnasion of Pergamon is known from inscriptions36

This brief overview has shown that the function of many structures with the noteworthy exceptions of bathing facilities and temples cannot be determined with certainty A cautious assessment of the distribution of functions is only possible for the best-known upper terrace whereas the other two terraces only allow for a clear differentiation of open versus covered space (fig 2) On the upper terrace open areas for multifunctional or predominantly athletic use prevail followed by bathing facili-ties rooms for multifunctional non-athletic purposes secondary service and storage rooms and ndash if temple R is included in the calculation ndash cultic space37 If space for athletic training multifunctional rooms and bathing facilities is considered standard for a gymnasion at least from the Hellenistic period onwards it is clear that the lower and middle terrace could not have functioned as entirely independent gymnasia because they lacked essential features such as multifunctional rooms and bathing facilities38 Ultimately the purpose of the costly and extravagant design with three ter-

36enspFor a brief summary of recent research on the Kellerstadion and Kammernreihe with reference to earlier literature see Stappmanns 2011 35 MathysStappmannsvon den Hoff 2012 272 Stappmanns 2012 238-243 For the inscriptions see von den Hoff 2004 386 note 93 389 note 109 IGRR IV 294-29537ensp Calculation basis 210 by 80 m (maximum extension in both directions) = 16800 m2 - at least 900 m2 of which were realistically not built sbquoKellerstadionlsquo 1500 m2 total 17400 m2 All measurements are approximate and include walls they are taken from Schazmann 1923 pl IV-V and Radt 1999 fig 29 The publication Schazmann 1923 does not systematically give measurements for all structures in the text furthermore measurements differ in the various publications see e g peristyle-courtyard of upper terrace Schazmann 1923 46 36 m x about double the length Delorme 1960 175 36 x 72 m Glass 1967 163 36 x 74 m Radt 1999 116 30 x 65 m Structures such as rooms 20-60 that were never visible and accessible are not included Access and circulation space is not counted separately the eastern access ramp to the upper terrace is not included at all Since statues and votives seem to have been set up in many different areas they are not counted as a separate functional unit here - Athletic purpose (courtyard possible stoa over gallery S terrace over rooms 20-60) c 6850 m2 39 bathing facilities c 4900 m2 28 multifunctionalnon-athletic purpose (rooms and porticoes of peristyle-courtyard only ground floor) c 3350 m2 19 secondary rooms for storage circulation technical purposes etc (sbquoKellerstadionlsquo) 1500 m2 9 cultic (temple R) c 800 m2 538enspThis was already emphasized in Schazmann 1923 10 see also Delorme 1960 181-182 Radt 1999 113

180emsp emspMonika Truumlmper

races and the possible differentiation in the use of these terraces split for example according to user groups or functions currently cannot be determined39

Attempts to reconstruct the original design of the gymnasion and its later devel-opment are based on archaeological and epigraphic evidence but correlating remains and inscriptions is not an easy straightforward task and is indeed controversial40 While the lower terrace was hardly changed41 the extent of alterations on the middle terrace is debated the temple was rebuilt and modernized in the Late Hellenistic period Whether the upper story of the north complex belonged to the original design or to a remodeling in the Hellenistic period currently cannot be determined with cer-tainty42 Since the function of this upper story stoa cannot be clearly determined its construction date ndash original or later addition ndash cannot be duly evaluated in a recon-struction of the functional program

Major structural and possibly functional alterations can be identified more clearly for the upper terrace The peristyle-complex originally was surrounded by double walls on its east north and west sides which continued in the west to include at least

39enspIn literature a differentiated use according to age groups is most popular but also much debated see most recently Radt 1999 113 Alternatively one could hypothesize that for example the middle terrace was primarily used for cultic and festive purposes or for sbquoleisurelsquo purposes such as agreeable strolls and the lower terrace for honorific and publicity purposes This is suggested by the most recent research Stappmanns 2011 31-32 MathysStappmannsvon den Hoff 2012 271-273 Stappmanns 2012 23740enspAstonishingly although the building history is more or less briefly discussed in all major publications and scholars were particularly interested in the Hellenistic phase of the building (see above note 25) no phase plans or graphic reconstructions of the original building were published before the recent attempt by von den Hoff 2009b fig 6 reproduced here with kind permission of the author as fig 3 This reconstruction reflects the state of research in 2009 Fieldwork carried out after this date has shown that the row of rooms to the south of the lsquoKellerstadionrsquo the so-called Kammernreihe also belongs to the original building even if it is not yet included in the reconstruction of von den Hoff 2009b fig 6 cf esp Stappmanns 2012 238-24341enspA stoa with broad shallow rooms was inserted between the buttresses of the northern terrace wall in the late Roman period this would hardly have caused major functional changes see Radt 1999 12042enspRadt 1999 120-124 assigns all structures to the first building phase Doumlrpfeld 1907 206-213 followed by Delorme 1960 172-175 and Glass 1967 158-162 reconstructed two major building phases the first would have included only the subterranean gallery and a (fourth) open terrace on an intermediate level between the upper and middle terrace This question will finally be decided by V Stappmannsrsquo research see above note 42 she was so kind as to inform me in pers comm that she rather agrees with Radt The building phases of the middle terrace are not yet discussed in detail in recent publications however see Stappmanns 2011 MathysStappmannsvon den Hoff 2012 271 Stappmanns 2012 236-237 - In addition to the renovation of the temple several installations dedications and votives were set up in the Late Hellenistic and Imperial periods among these is a sophisticated water clock that was installed subsequently on the north wall to the east of room 58 in the Late Hellenistic or early Imperial period see Radt 2005

Modernization and change of function of Hellenistic gymnasia emsp emsp181

Fig 3 Pergamon gymnasion hypothetical reconstruction of the original plan drawing E Raming after instructions by V Stappmanns and R von den Hoff von den Hoff 2009b fig 6

182emsp emspMonika Truumlmper

Fig 4 Pergamon gymnasion upper terrace hypothetical functional plan of the original building M Truumlmper after von den Hoff 2009b fig 6

Modernization and change of function of Hellenistic gymnasia emsp emsp183

rooms N and O and probably also rooms T and Wf (figs 3 4)43 The peristyle-complex is reconstructed with double-storied Doric colonnades flanked by about 12 rooms on the ground floor (and most likely another 12 on the upper floor) six of which probably kept their original size through all phases four in the east (A B CD E) five in the north (H F G and two at the location of room J) and three in the west (K L M)44 At least two and possibly three (H K possibly M) were designed as exedrae45 and L was most likely a loutron from the beginning The decoration was simple and included only earth floors and local stone for architectural elements46 The rooms thus in theory could have been used for athletic activities as well as multifunctional pur-poses Whether the terrain to the east and west of the peristyle-complex was occupied by any structures other than temple R is unknown and nothing can be concluded about its possible original use According to the building techniques and orientation of the walls rooms N O T and Wf could have belonged to the original design of the gymnasion but their function cannot be determined with the exception of room N which served as a staircase to the subterranean gallery47

The first identifiable changes were the benefactions by the gymnasiarch Metro-doros these cannot safely be dated but are commonly assigned to the last third of the 2nd century BC48 He provided for the adduction of water to the bath of the presby-teroi and he set up public basins (lenoi) in this bath he also donated two public free-

43enspFor the reconstruction of a double wall in the east see Pirson 2006 68-71 von den Hoff 2007 38-40 Pirson 2006 70 concludes that the terrain of the later east baths was bdquourspruumlnglich nicht in das Nutzungskonzept des Gymnasions einbezogenldquo It remains to be clarified 1) whether this terrain was built at all when the gymnasion was constructed and how it was possibly used (no remains were found in the eastern sondage in courtyard 4 of the east baths Pirson 2006 71) and 2) when the east faccedilade of the east baths which appears as partially Hellenistic on older plans such as Doumlrpfeld 1910 348 fig 1 and Schazmann 1923 pl IV-V (here fig 1) was built Von den Hoff 2009b fig 6 (here fig 3) does not include this wall as a feature of the original gymnasion also his plan does not include the partition walls between rooms N and O O and T and T and W that are identified as features of the original building on earlier plans44enspSchazmann 1923 46-69 Radt 1999 124-130 von den Hoff 2009b A sondage in room G did no confirm the previous assumption that this room had been subdivided into two rooms in the Hellenistic period von den Hoff 2008 10845enspThe exedrae reconstructed on the upper floor above rooms K and M are also assigned to the original building see Schazmann 1923 pl XVII von den Hoff 2009b catalog no 7 reconstructs only two exedrae (H and K) for the first phase but Stappmanns 2011 34-36 fig 7 three (H K M)46enspNo marble was used yet this was confirmed by the recent research Pirson 2006 71-72 von den Hoff 2007 36 40 MathysStappmannsvon den Hoff 2012 27347enspSee above note 4348enspI Pergamon 252 Hepding 1907 273-278 no 10 Radt 1999 128 - Schuler 2004 192 dates this inscription shortly after 133 BC which corresponds with Amelingrsquos second period in the history of the gymnasion Ameling 2004 145-146 Von den Hoff 2004 386 note 93 dates the inscription to 140130 BC Woumlrrle 2007 509 note 48 to 133-130 BC von den Hoff 2009a 164 note 64 assigns this inscription more broadly to the late 2nd century BC (bdquospaumlteres 2 JhvChrldquo)

184emsp emspMonika Truumlmper

standing round basins (louteres) and sponges for the sphairisterion and established a regulation for the surveillance of clothes His efforts were rewarded with two statues one dedicated by the people and located in the paradromis and one dedicated by the neoi and placed in an unknown location While the bath of the presbyteroi was unani-mously identified as room L where Metrodoros would have installed the niche in the west wall and the marble basins that are still visible the sphairisterion was located with more reserve in the adjacent exedra K because it has evidence of water installa-tions on its west wall49 Both identifications however are far from certain the marble basins in L and the various water management installations of this room currently cannot be dated precisely and Metrodoros donated public but not expressly marble basins Since marble seems not to have been used in the original gymnasion and the donation of marble elements was explicitly mentioned in other later inscriptions50 it would have been astonishing if Metrodoros had not emphatically emphasized such an unusual expense Furthermore the reference to the bath of the presbyteroi sug-gests that there existed at least one other bathroom used by another (age) group at the time when Metrodoros made his contribution Jean Delorme had already pointed out that the freestanding louteres set up in the sphairisterion are incompatible with the fixtures in room K because the latter would have required a placement of the basins along the west wall51 In addition recent excavations in Room K have shown that the room and particularly its floor was heavily remodeled in the 1st century BC so that the stone slabs currently visible on the west wall could not have supported the

49enspSchazmann 1923 65-66 Delorme 1960 186 189 Glass 1967 174 Radt 1999 128-129 von den Hoff 2009a 164 note 64 The evidence in room K consists of a series of dowel holes on at least three different levels on the west wall and is far less conclusive than a similar feature in the adjacent loutron L (one series of dowel holes on the north east and south walls immediately over the basins) No attempt has been made so far to reconstruct the possible installation connected with the dowel holes in room K - Woumlrrle 2007 511-512 note 64 states that Metrodoros was the first to open the gymnasion to the presbyteroi and within this context had bdquodie Waschraumlume mit zusaumltzlichen Becken versehenldquo he does not attempt to identify these bathrooms (in the plural) in the archaeological record50enspSee e g donations by Diodoros Pasaparos below notes 54-55 While a sondage in room L allowed for the identification of three different building phases von den Hoff 2009a 163-164 and above note 27 no diagnostic stratified material was found that would provide a secure date for the second and third phase In von den Hoff 2009a 164 note 64 both phases are linked without further discussion however with improvements of bathing facilities by Metrodoros and Diodoros Pasparos that are known from inscriptions 51enspDelorme 1960 189 see also Glass 1967 174 - Woumlrrlersquos intriguing assumption Woumlrrle 2007 512-513 note 48 that Metrodoros merely supplied existing bathrooms with additional washbasins for the presbyteroi cannot be substantiated from the archaeological record in general an increase in the capacity of bathing facilities in Hellenistic gymnasia seems rather to have been achieved by adding separate rooms see e g the gymnasion of Eretria (rooms B-D) Mango 2003 passim or the gymnasion of Amphipolis Wacker 1996 141-144

Modernization and change of function of Hellenistic gymnasia emsp emsp185

basins donated by Metrodoros52 The sphairisterion therefore cannot be safely locat-ed53 Whether room K was nevertheless transformed into an additional (makeshift) bathroom with the typical basins along its wall at a yet unknown date must remain open its wide opening and the possible lack of a waterproof pavement are in any case highly atypical for such a function and the doubtful evidence of water instal-lations does not help to substantiate this theory What remains to be emphasized is that Metrodoros was exclusively concerned with improving the hygienic facilities of the gymnasion

The same trend was pursued after 69 BC by the gymnasiarch Diodoros Pasparos whose rebuilding works were of such a vast scale that he was celebrated as second founder of the gymnasion54 He did something unknown to the peripatos constructed a new konisterion with a marble exedra in front of it and next to the konisterion built (or renovated) a marble loutron whose ceiling was (re)painted and whose walls were revetted55 In recognition of his benefactions he was honored with a lavishly decorated exedra and at least four statues (three of marble one of bronze) in the gym-nasion56 While the identification of the exedra with room B is commonly accepted the location of all the other rooms is debated57 Scholars agree that the konisterion

52enspVon den Hoff 2008 109 bdquoReste des zur ersten Nutzungsphase gehoumlrigen Fuszligbodens konnten nicht beobachtet werden Die uumlber der Fuumlllschicht der Erbauungsphase eingebrachte Auffuumlllung ent-hielt vielmehr spaumlthellenistisches Keramikmaterial und einen Fundkomplex weiblicher Terrakotten die eine grundlegende Neugestaltung des Raumes mit Entfernung der aumllteren Schichten fruumlhestens im 1 Jh v Chr nahelegenldquo 53enspFurthermore the function of the sphairisterion is debated While Delorme 1960 281-286 interprets it as a boxing room that was provided with a special floor Radt 1999 128 sticks to the older identification of a room for ball games Neither comments that the combination of an unpaved floor which was necessary for boxing as well as ball games and water installations is astonishing and requires an explanation54enspFor Diodoros Pasparos see most recently Chankowski 1998 and Ameling 2004 142-145 with older literature Musti 2009 55enspThe precise extent and nature of the renovation program is debated Hepding 1907 266 suggests that Diodoros renovated the peripatos Delorme 1960 184 and Glass 1967 167-168 admit that it is not known what Diodoros did with the peripatos Ameling 2004 143 note 82 assumes that he built the peripatos Pirson 2006 68 71 with reference to Radt 1999 126 argues that Diodoros dedicated and built a bdquoGarten mit Peripatosldquo which according to recent research could well have been located at the spot that is currently occupied by the east baths - Hepding 1907 267 Schazmann 1923 52 Glass 1967 168 and Ameling 2004 143 think that Diodoros built the marble loutron but Delorme 1960 184 and Chankowski 1998 176 translate Hepding 1907 259-260 l 22 bdquoἀπογράψανταldquo (for the loutron) and l 38 bdquoἀπογραφείσηςldquo (for the exedra of Diodoros) with bdquorepaintingldquo (the ceiling) which suggests just a renovation or redecoration Radt 1999 125 also states that Diodoros had bdquodas Bad (Lutron) in Marmor neu erbautldquo which suggests that there was only one single bath that was renovated This also seems to be assumed by von den Hoff 2009a 164 note 6456enspVon den Hoff 2004 388-390 with older literature57enspAccording to von den Hoff 2009b 256 note 41 however recent excavations have revealed a Π-shaped bema in room B that could have served as a couch for dining and was probably installed

186emsp emspMonika Truumlmper

with its exedra and the loutron were placed somewhere in the northeast corner of the peristyle-complex so that all the structures linked to Diodoros formed a coherent unit but they differ in assigning the number of rooms (two or three) and their relation-ship to the eastern wing (within the confines of this wing or to the east of it)58 This question cannot be decided until extensive excavations under rooms C-F and the east baths reveal conclusive evidence but recent excavations did not discover any clues that would safely corroborate the existence of a konisterion under rooms C and D and of a loutron under room F nor did they confirm the so far unanimous identification of room B as Diodorosrsquo exedra59 What can safely be concluded however is first that Diodoros was again concerned with an improvement and embellishment of some sports facilities and the bathing facilities which were obviously still in the old-fash-ioned simple Greek style60 and second that he clearly strove for a more prestigious

in the 1st century BC This would clearly be incompatible with Diodorosrsquo exedra which included an agalma of Diodoros see von den Hoff 2004 389 notes 113-114 It would therefore require a complete reassessment of the possible location of Diodorosrsquo donations in the gymnasion58enspFor the konisterion see above note 31 - Delorme 1960 188 reconstructs the loutron in the center of the east wing at the place of rooms C and D with an entirely hypothetical north-south extension of 9 m and the exedra of the konisterion to its north (DE with architecture of room D) followed by the konisterion in the northeast corner (F and G) Apart from the fact that the distance between the north wall of exedra B and the foundation of an abraded wall in exedra D is c 15 m instead of 9 m this reconstruction does not take into account the Doric architecture of room E which is commonly assigned to the period of Diodoros Glass 1967 173-174 suggests that the loutron bdquois probably to be sought somewhere in the badly destroyed northeast corner of the courtldquo Radt 1999 126 following Schazmann 1923 55 assumes that the loutron was placed on the terrain of the later east baths accessible through room E Nobody discusses what realistically could have been of marble in this loutron probably only the frame of the - preferably narrow - door and the basins while a marble pavement and revetment of the walls would still have been unusual at this time - Hepding 1907 266 and Glass 1967 170 identify the peripatos with the porticoes of the peristyle-courtyard in contrast to this Delorme 1960 189-190 (followed by Pirson 2006 71) interpreted it as bdquoun lieu de promenade et speacutecialement des alleacutees ombrageacutees On pensera donc (hellip) agrave des jardins (hellip)ldquo This garden-promenade could have been located at the spot currently occupied by the east baths or on the middle terrace He does not discuss the possible function of this complex athletic recreational sbquointellectuallsquo (for discussions while walking) etc Delormersquos idea is more intriguing the more so because evidence for a Late Hellenistic remodeling or repair of the porticoes of the peristyle-courtyard is still missing59enspFor recent sondages in rooms B C D F and 4 see Pirson 2006 68-72 von den Hoff 2007 and in more detail below note 74 Nothing which would indicate the presence of a loutron in the northeast corner of the peristyle-courtyard (e g paved floor water installations traces of basins on the walls) was found in room F Room CD might have been provided with a water installation (basin drainage) which was added subsequently (in the Late Hellenistic or early Imperial period) but was related to an earth floor and probably to other features such as a statue base and a bench None of these features seems to be very well compatible with a konisterion of either definition see above note 31 For room B see above note 5760enspAs those sponsored by Metrodoros some 50-60 years earlier Diodoros could at least have donated a more fashionable sweat bath

Modernization and change of function of Hellenistic gymnasia emsp emsp187

and lavish decoration of the gymnasion which hitherto most likely had been rather modest if not dingy

The archaeological remains provide evidence of further building activities in the Late Hellenistic period first the construction of two further marble exedrae one ded-icated to Hermes by an unknown person and another donated by Pyrrhos61 These correspond well with Diodorosrsquo endeavors to enhance the appearance of the gymna-sion albeit on a much smaller scale Another building activity may have been the installation of a large (10 x 1250 m) rectangular sweat bath in room W This room is barely published and its date and reconstruction are debated (figs 5 6 )62 It is paved with terracotta slabs and was provided with quarter-circular structures in three corners while the fourth southeast corner was occupied by the entrance door these structures as well as the pavement and walls showed strong traces of fire when they were excavated63 Several factors suggest that room W was built before the west baths but at the expense of an earlier Hellenistic room its terracotta pavement covers an earlier wall64 Its east and north walls seem to have been overbuilt by walls of the

61enspSchazmann 1923 58 66-69 pl XIX followed by Delorme 1960 178-179 186-188 and Radt 1999 129-130 assumes that both exedrae originally occupied the spot currently taken by room G and were transferred in the Imperial period to the south end of room M and to the area of rooms W and f - Glass 1967 166 note 458 170 is more skeptical and states that their locations (both the original and the possible later one) are totally uncertain and that it is not even clear whether the architectural remains belong to exedrae Both exedrae were dated based only on the style of their architectural elements and were commonly compared to the donations of Diodoros (notably the entrance architecture of rooms B D E) Glassrsquo skepticism is confirmed by recent research which did not yield evidence of an original subdivision of room G into two rooms see von den Hoff 2008 108 and above note 4462enspDoumlrpfeld 1908 345-346 349 dates this room to the end of the royal period or the beginning of Roman rule because its foundations would have been made of soft tufa stone without lime mortar he cannot explain the function of this room - Schazmann 1923 81 followed by Radt 1999 131-132 identifies this room as a later addition to the west baths its foundations would have been made of soft fireproof bdquoArasteinldquo the room would have been provided with hypocausts and tubuli (of which nothing is preserved although remains of both are well preserved in rooms 2 3 6 and 7 of the east baths) which were connected with the quarter-circular structures in the corners the room would have been heated from praefurnium V but there is in reality no evidence of a connection between the two rooms - Neither Delorme 1960 nor Glass 1967 discusses room W because it presumably belonged to the Imperial period not treated by them This room is not included in the reconstruction of the original gymnasion by von den Hoff 2009b fig 6 (here fig 3) and it is not discussed in any of the publications that present recent fieldwork and research see above note 2263enspSchazmann 1923 83 Exactly which walls were covered with traces of fire and soot and up to what height is not indicated was it the north wall and the northern half of the east wall which were preserved to a considerable height or could it also include the southern half of the east wall the south and the west walls of which only the foundations survive This information is crucial for the reconstruction of the history of this room see below note 6564enspThis is at least suggested by the plans Doumlrpfeld 1908 pl XVII and Schazmann 1923 pl IV-V V Stappmanns also has kindly informed me that this is still visible at one spot on the site

188emsp emspMonika Truumlmper

Fig 5 Pergamon gymnasion west baths hypothetical phase plan M Truumlmper after Schazmann 1923 pl IVndashV

Modernization and change of function of Hellenistic gymnasia emsp emsp189

Fig 6 Pergamon gymnasion west baths room W (sweat bath) overview from northeast M Truumlmper

Fig 7 Pergamon gymnasion west baths Fig 8 Pergamon gymnasion westpassageway between rooms M and N baths room Z south wall with blockedpavement with terracotta slabs from east arched opening from north M TruumlmperM Truumlmper

190emsp emspMonika Truumlmper

Imperial period65 Finally rooms T and MN were also paved with terracotta slabs roughly on the same level as room W66 probably at the same time that room W was installed and the whole room suite NOTW was transformed into a bathing complex (fig 7)67 As a large sweat bath that was not yet heated by hypocausts but probably by some devices placed in the corner-structures and by braziers or other heat sources set up in the middle of the room this room would fit well into the above-mentioned development of bathing facilities in Late Hellenistic gymnasia also it would finally have provided this large gymnasion with a modern luxurious bathing standard that had so far been lacking While the precise date of the construction of this room and its possible initiator and donor are unknown it is intriguing to date it after Diodorosrsquo renovation program which had included only a simple cold-water bathroom

The predominant focus of building activities on an improvement of bathing facili-ties in the Hellenistic period was continued in the Imperial period albeit on a different scale and with much more sophisticated Roman-style facilities first with the con-struction of the west baths in the mid-1st century AD and its expansion at an unknown date and second with the installation in the Trajanic or Hadrianic period of the much larger east baths a structure which was also subsequently remodeled Since both com-plexes and particularly the west baths require a reexamination to safely reconstruct their history and precise functioning some preliminary remarks must suffice here

The west baths seem to have been squeezed into an unfavorably cut building lot probably in order to continue a pre-established use of this area and also because the much larger terrain to the east of the peristyle-complex was not yet available for such a purpose (fig 5)68 The priorities of its original design which most likely included only

65enspThe plans Doumlrpfeld 1908 pl XVIII and Schazmann 1923 pl IV-V are not very clear in this area but the Roman west wall of room U which according to Schazmannrsquos reconstruction should be contemporary with the east wall of W 1) is not aligned with the southern preserved half of the east wall of W 2) is also made of different material and 3) is preserved to a considerable height while only the foundation of the southern half of the east wall of W remains - The plan Yeguumll 1992 288 fig 366 simply omits these problematic walls or shows them as dashed lines without further explanation66enspThis could only roughly be evaluated by visual judgment Schazmann 1923 pl V-VII probably shows a few terracotta slabs at the western border of room T that are still visible today but not the terracotta slabs that are preserved today in the passageway between rooms M and N - The sparse indications of levels on the plans Doumlrpfeld 1908 pl XVIII and Schazmann 1923 pl IV-V are not really conclusive and would have to be checked the more so because the terracotta slabs in rooms T and N are not mentioned anywhere in the text nor are they indicated in the plans (all indications in m above sea level) N 8683 O 8730 T none given W 8685 P 8750 (in the northern niche) U 8750 X 8689 V 8680 Z none given67enspIn theory rooms O T and Wf could have been used for bathing earlier maybe even from the first building phase onwards this would imply an intriguing continuity of use for this part of the upper terrace see also below68enspOnly further research can show however for how long if at all the potential sweat bath W next to the new Roman-style west baths was used For the west baths see Schazmann 1923 80-84 Radt 1999 131-132 Nielsen 1990 II 38 C308 Yeguumll 1992 288

Modernization and change of function of Hellenistic gymnasia emsp emsp191

the construction of rooms P U X and a praefurnium at the spot of room Z are easily recognizable the focus was on the caldarium X which was heated by hypocausts and provided the gymnasion with its first hot water bath69 by contrast the frigidarium P is very small and only had a relatively small cold water tub in its northern niche Room U (sbquotepidariumlsquo) was not heated by hypocausts and contained no water instal-lations This bathing program can be compared to those of baths from the early Impe-rial period in the western Mediterranean particularly Italy and thus it betrays the first clearly identifiable Roman influence in the Pergamenian gymnasion This also can be seen in the employment of the contemporary innovative hypocaust technique and possibly the decoration of the caldarium and frigidarium with symmetrically arranged semi-circular and rectangular niches70 The original decoration of this bath was simple and it remained so even though it was remodeled at least once when the caldarium was expanded to the west (room Z) Whether room Z contained an alveus and how this was heated and whether room X still served as a caldarium after this extension however is highly questionable (figs 8 9 )71 An understanding of the date and purpose of this remodeling is important for an assessment of the relationship between the west baths and the much larger and more lavish east baths were the first still used when the latter were built and if so how

The construction of the east baths was part of the most extensive remodeling process of the gymnasion in the Imperial period72 This seems to have been funded by a group of various donors and included the renewal of the double-storied Doric

69enspAn alveus which was most likely placed in the niche of the west wall and heated from an installation (praefurnium) on the spot that is currently occupied by room Z 70enspAll traces of the hypocausts were removed when the west baths were transformed into a cistern in the Byzantine period - The origin of the design with niches and recesses is however debated According to Nielsen 1990 I 103 this was first used in baths of the eastern Mediterranean71enspThe wall between room Z and the sbquopraefurniumlsquo V originally included a wide high arched opening which was only subsequently partially blocked (although indicated on the plan Schazmann 1923 pl IV-V it is not described in the text Schazmann 1923 83-84 here fig 8) the resulting small rectangular opening comprises in its interior bricks traces of fire and a round cavity for a boiler (fig 9) All this is hardly compatible with a typical Roman praefurnium and hypocaust heating The very brief description of room V in Schazmann 1923 83-84 is insufficient and unclear for example a staircase on the south wall is identified as access to a hot water boiler although it is built against a wall which is marked as Byzantine on the plan and room W as a potential sweat bath would not have required hot water 72ensp The various measures are dated from the Trajanic through the Antonine periods Radt 1999 124-134 the dates are not consistent however for example the renewal of the peristyle-colonnades is dated p 125 to the Trajanic and p 127 to the Hadrianic period A Trajanic date is again confirmed by MathysStappmannsvon den Hoff 2012 273 According to von den Hoff 2007 38-40 recent excavations confirm that the east baths were built in the Hadrianic period at the earliest but in Mathysvon den Hoff 2011 44 the east baths are dated to the Trajanic period It cannot be determined whether either of the two remodeling phases identified in louton L belonged to the Imperial period and particularly to the large remodeling program in the 2nd century AD see above notes 27 50

192emsp emspMonika Truumlmper

andesite colonnades of the peristyle in marble and in the Corinthian order the con-struction of the east baths on terrain of unknown function as well as the construc-tion of room F the sbquoKaisersaallsquo G73 and the odeion J at the expense of several earlier rooms the remodeling of the faccedilade architecture of room H and probably also of room K and alterations in the eastern wing (rooms C-E) with reuse of older faccedilade

Fig 9 Pergamon gymnasion west baths wall between rooms Y and Z bricks traces of fire rounded cavity from south M Truumlmper

architecture74 Despite the relatively restricted building lot the design and bathing program of the east baths was oriented on contemporary standards particularly

73ensp This room could have been modeled after the so-called imperial halls (sbquoKaisersaumllelsquo) or marble halls that are characteristic of many bath-gymnasia these rooms commonly bdquoopened into the palaistra through a screen of colonnades and displayed strikingly rich marble facades of superimposed aediculaeldquo See Yeguumll 1992 422-423 (citation 422) see also Steskal 2003b 234 where he still votes for a cultic function of these rooms and Steskal 2003a 161-163 where he is more critical regarding the cultic function and advocates a more multifunctional purpose bdquoOrte der Selbstdarstellung der Stifter der Repraumlsentation sowie (hellip) Versammlungs- oder sbquoClubsaumllelsquoldquo For a critical assessment of the cultic function of these rooms see also Newby 2005 238-23974enspRecent excavations have shown that the rooms in the east wing were remodeled many times during the Late Hellenistic and Imperial periods Pirson 2006 71-72 von den Hoff 2007 36-40 Exedra B several decoration phases - Room C 1) Hellenistic earth floor and polychrome stucco 2) earth floor from the early Imperial period with two molded supports for a bench and probably a drain to the east 3) floor of stone slabs from the 2nd century AD 1) and 2) when room C was still united with room D 3) when it was transformed into an access to the east baths - Exedra D 1a + b) Hellenistic earth floor to which were later added two foundations that probably supported a water basin and a statue base 2) and 3) two Roman floor levels and decoration phases The relationship between the different phases in rooms C and D has not yet been safely determined - Rooms E and F were used

Modernization and change of function of Hellenistic gymnasia emsp emsp193

those established in the eastern bath-gymnasia furthermore these baths were now lavishly decorated with marble and mosaic floors75 Compared to the west baths with its one single entrance from the peristyle-complex via exedra M access to the east baths was far superior in the form of three entrances from the eastern portico via corridor C room F and finally room E which was the most lavish and sbquomonumentallsquo example of all three and most likely served as the main access76 As in the west baths the focus was on the warm bathing rooms which originally included rooms 3 and 7 The frigidarium 9 is small and located outside the main flight of bathing rooms and half of it is taken up by a cold water immersion basin The L-shaped suite that con-sisted of the lavish multipurpose halls 5 and 8 and to which the most richly decorated room of the bath room 11 also belonged originally occupied more terrain than any other rooms Such long halls or galleries are characteristic of eastern bath-gymnasia and have been interpreted as multipurpose rooms bdquoserving a variety of uses ndash chang-ing rooms entrance halls lounges for resting or promenading or even as spaces for light indoor sports during unfavorable weatherldquo77 Obviously the builders of the Per-gamenian bath did not want to dispense with these highly prestigious luxury halls78 These rooms were reduced in favor of two new sweat rooms (2 and 6) however when the bath was remodeled in the 3rd century AD79

without drastic changes and with the same floor levels from the 2nd century BC through the Trajanic period and both had earth floors both were altered when the east baths were built and were again remodeled later in the Imperial period75enspFor the east baths see Doumlrpfeld 1910 347-350 Schazmann 1923 85-92 Nielsen 1990 II 38 C310 Yeguumll 1992 288 Radt 1999 132-13476enspRadt 1999 132 emphasizes the lack of a monumental accentuated entrance to the east baths bdquoOffenbar war immer noch die Palaumlstra der Mittelpunkt des Gymnasions die Thermen waren ein Zusatz der unter funktionalen Gesichtspunkten errichtet wurdeldquo Apart from the fact that room E was the clearly highlighted main entrance to the east baths in most newly built bath-gymnasia the entrances to the bath-complexes proper that is the doorways between palaistrai and baths were relatively small and inconspicuous and monumental propyla were rather a prerogative of the palaistrai See Yeguumll 1992 307-313 and the many plans in his chapter on baths and gymnasia in Asia Minor 250-313 77enspYeguumll 1992 414-416 (citation p 414 synopsis of plans of such halls fig 501) - Since room 8 is paved with a mosaic floor and room 5 with stone slabs however their use for light indoor sports seems questionable - See already Schazmann 1923 88 for an assessment of room 85 bdquoeigentliche(r) Repraumlsentationsraum der Anlageldquo bdquogroszlige Wandelhalle mit einer anschlieszligenden groszligen Exedraldquo bdquoAuskleideraumldquo bdquoWarte- und Ruhehallenldquo78enspOther characteristics of many newly built bath-gymnasia such as an axial-symmetrical layout could not be implemented here however due to the lack of space 79enspThis modernization of the bath included changes in the praefurnium 1 and in the heating systems of rooms 3 and 7 as well as the construction of an alveus in room 7 cf Schazmann 1923 86 88 90-91 Radt 1999 132-133 Recent excavations have discovered further alterations in rooms E and F von den Hoff 2007 38-40 It is unknown however whether all of these building measures belonged to one single remodeling program

194emsp emspMonika Truumlmper

Several other alterations that are commonly dated to the later Imperial period namely the 3rd century AD show that the gymnasion was still in use during this period but it is unknown when and how it was finally abandoned80