Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

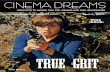

THE BAD SEED 1956lecinemadreams.blogspot.com/2012/04/the-bad-seed-1956.html

For the most part, I don’t see anything inherently bad in a film morphing from one kind of entertainment into anotherover the course of its “screening life.” By this I mean, films - a populist entertainment/art form presumed of a certainmarketable topicality at the time of their release, are, by nature, vulnerable to the vagaries of time. A movie can startout as one kind of entertainment—say, thoughtful social drama—but, due to changing public tastes, evolve over timeinto something that gives pleasure to countless hundreds in new, totally unexpected ways (e.g., high camp).

Some films, like John Huston’s The Treasure of Sierra Madre (1948) and George Stevens’ A Place in the Sun(1951), feel every bit as powerful and affecting today as I imagine they did to audiences some six decades ago.While other films, dismissed or misunderstood in their own time (Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo, Orson Welles’ CitizenKane, Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter) benefit from revisionism and the kind of clear-eyed, contextualreassessment of art only possible with the distancing effect of time. But more often than not, older films just taketheir place in our collective consciousness as works superficially cloaked in the trappings of their time. Datedvehicles addressing otherwise timeless concerns of love, death, humanity, and hope. If the emotions are true andthe stories compelling, we don’t necessarily care if the costumes are out-of-date, the dialog archaic, or style offilmmaking passé; the movie still works in the ways originally intended.

What seems to play havoc with a film’s continuing relevance is a non-scientific equation that takes over-emphatic,up-to-the-minute immediacy, multiplies it by sensationalism, and adds a dash of self-seriousness. The result isusually something so mired in a particular time, place, and mindset that they become near-impossible to enjoy ortake seriously on any of the levels once deemed effective. We see it in highly-stylized dramatic films from the '30sand '40s; where stage-bound acting techniques (characters speaking into the distance rather than to one another,over-broad gestures and facial expressions) have a distancing effect on our ability to become involved in thenarrative. In these instances, a film’s elder status becomes an intractable element contributing to how it is viewed bycontemporary audiences. A variable which establishes the terms and boundaries of its broader acceptance.

1/12

When psychoanalysis was new, juvenile delinquency in its infancy, and post-war conformity at its height, MaxwellAnderson’s Broadway 1954 play The Bad Seed (adapted from the 1954 novel by William March) must have beenquite the eye-opener. A thriller about a sociopathic 8-year-old serial killer sounds like a weed among the roses in aBroadway season that saw the premieres of Peter Pan and The Pajama Game, but the chillingly original premiseand by-all-accounts remarkable performance of little 9-year-old, anti-Shirley Temple, Patty McCormack, made TheBad Seed into a solid hit. Co-star Nancy Kelly won the Tony Award for Best Actress that year, and in a rarity forHollywood, virtually the entire principal cast was recruited to recreate their roles for the 1956 film adaptation.

But not everything that plays well across the footlights survives the magnification of the movie screen. Suffering froma perhaps too-faithful adaptation that had characters doing nothing but conversing for fitfully long stretches whileengaged in a lot of theatrically fussy “stage business,” the close-up lens trained on The Bad Seed seemed toamplify the dubious premise of the plot (hereditary homicidal tendencies) while doing nothing to add verisimilitude orspontaneity to the progressively melodramatic proceedings.

Nancy Kelly as Christine Penmark

2/12

Patty McCormack as Rhoda Penmark

Eileen Heckart as Hortense Daigle

3/12

Henry Jones as Leroy Jessup

Navy Colonel Kenneth Penmark and wife Christine seem to have the ideal child in their little Rhoda: an angelic,near-perfect package of pigtails and ruffles, adorned with girlish grace and good manners. When Kenneth is calledaway to Washington for business, Christine (who’s wound a little tight from the get-go) begins to suspect thatRhoda’s immaculate façade isn’t perhaps masking a more disturbed, darker personality dysfunction. The mysteriousdeath of a local schoolboy and Christine’s own epiphanic discovery of her birth lineage lead her to believe that littleRhoda might be a budding serial killer: a possessor of a hereditary “bad seed” gene passed on to Rhoda byChristine herself. What to do? What to do? What to do?

Al Hirschfeld

I make light of the preposterous-sounding premise, but quite honestly, when removed from the gimmicky “serial killergene” plotline, The Bad Seed is pretty solid thriller material and might have even tapped into the post-war/McCarthy-era “banality of evil” zeitgeist of Invasion of the Body Snatchers (released the same year) had it managedto sidestep the theatrical histrionics and showed more faith in presenting a dark vision of idealized suburbanperfection.* Spoiler Alert! If you've never seen The Bad Seed, read no further. Run, don't walk, and get your hands on a copy ofthis film NOW! You're in for a treat. Come back later...we'll still be here.

4/12

I personally love the Hays Code-mandated, tacked-on ending that has God’s retribution striking down little Rhoda inthe middle of her most Godless act (in the play, Rhoda lives and it's the mother who dies), but feel it would havebeen even more powerful without the survival of the mother and her guilt-leaden hospital bed confession.Thematically, The Bad Seed is ill-served by how deeply the plot (and seemingly interminable chunks of dialog) ismired in outmoded Freudian psychological theorems. Stylistically, its effectiveness as a suspense thriller isundermined by an overwrought theatricality that turns every scene that should be gripping melodrama into a satireof American suburban ideals.

Although not easy to make out, that little crinoline blur in the upper left-hand corner of this screencap is an airborne Rhoda, avoiding the passive-

aggressive spray of the garden hose Leroy (Henry Jones) is intent on training onher plot-significant Mary Jane shoes.

I couldn’t have been much older than Rhoda myself when I first saw The Bad Seed on TV (definitely the last time Iever took the film as seriously). I was raised in a middle-class neighborhood during a time when kids were broughtup to be seen and not heard. To be obedient and polite, to say "Please" and "Thank you," and to never, but NEVERspeak back to grownups. So it shocked the hell out of me to see a little girl who could have stepped out of anepisode of Father Knows Best or Leave it to Beaver behaving so monstrously. The idea that a kid could exert anypower over their own lives at all was alien enough, let alone plan and carry out vicious murders with nary a trace ofremorse.

I certainly didn’t mind that the deaths of little Claude Daigle or handyman Leroy were never shown (somethingunthinkable today, especially if that talentless hack Eli Roth makes good on a long ago threat/promise to remake thisfilm) because my fertile kid’s imagination furnished all the gory details. I remember being very torn up by the grief ofEileen Heckart’s Mrs. Daigle and the sound of the gunshot near the end nearly sent me flying off the sofa. Thestrongest memory I have is of Rhoda’s final trip to the boathouse. It was spooky enough that she was out by herselfat night in a rainstorm, but I thought maybe her maddeningly clueless father was going to wake up and catch herred-handed with the medal. That bolt of lightning hit me like ...well, a bolt of lightning. OMG! I had NEVER seen akid killed in a movie before and that image stayed with me for many a nightmare.

5/12

Evelyn Varden portrays annoying landlady and neighbor, Monica Breedlove.

Naiveté definitely has its advantages with some films, so at least I get to say that I had one pure experience of TheBad Seed. Perhaps the closest one can get without time-traveling back to 1953.Over the course of the next several years however, The Bad Seed, almost imperceptibly, went from serious tohilarious in my eyes. The pitch of the film had always been a little high, but with maturity, the passing of time, andchanging tastes, The Bad Seed started to look as dated and reactionary as one of those “social guidance” films ofthe '50s and '60s. A turn of events that’s had the curious effect of making The Bad Seed more watchable, not less.

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILMAlthough I consider a great many real-life children to be monsters, I think it’s extremely difficult to make them lookmenacing on the screen. The 1976 film The Omen sidestepped the pitfall the wan 2006 remake fell into (headfirst)by framing the action in ways which left the child’s evil nature left ambiguous. In the 1976 film, the child merelybehaves in a normal fashion and the audience is left to project whatever we wanted onto his angelic pan. In theremake, the child actor is directed to continually glower into the camera...the result: the surely-unwanted effect of achild suffering a tummy ache rather than the conveyance of a subterranean malevolence within the spawn of Satan.What makes Patty McCormack so memorably creepy in The Bad Seed is that she's like a schoolyard bully dreamtup by Murder, Inc.

6/12

"You better bring them back here! Right here to MEEEEEEE!"

The only reason this scene gets laughs is because Patty McCormack is scarierthan hell in it. You can't believe a little girl in pigtails and a pinafore can make the

hairs on the back of your neck stand up.

These days, when the bratty behavior of children is business-as-usual in every sitcom and movie I see (seriously,the sociopath at the center of the 2011 thriller We Need to Talk About Kevin is indistinguishable from and no morehorrific than today's average over-entitled teen ...which may be the point) little Rhoda Penmark comes off more likea miniature Alexis Carrington than homicidal maniac. Her outbursts and threats make us giggle certainly because ofthe incongruity presented by her size and appearance contrasted with her behavior; but also because she’s carryingon in a way we’ve long come to associate with grown-up entertainment industry brats and divas. Rhoda is rude,ruthless, selfish, self-involved, single-mindedly determined to get what she wants, and impervious to the suffering ofothers. Now, who doesn't think that sounds like Madonna or Elton John?

The Original Material Girl

PERFORMANCESNancy Kelly and Eileen Heckart give the kind of robust, herculean performances that garner Oscar nominations, andindeed both (along with McCormack) were in fact nominated for Academy Awards. Both are very good but neither

7/12

actress lets up “acting” for even a second, making every ill-tempered intrusion by McCormack a welcome one.Kelly’s stylistic excesses and singsong way of conveying sincerity may induce laughter, but the anguish hercharacter goes through is really rather affectingly played. Heckart has some great material and much of it she playswith real poignance, but a little too much theatrical “drunk” shtick creeps into the characterization for it to avoid theoccasional lapse into overkill. The film’s true star and absolute marvel is 10-year-old Patty McCormack. Althoughher performance is over-rehearsed to within a hairsbreadth, her Rhoda is a hilariously two-faced—creation an identifiable hyper-phony like Leave it to Beaver's Eddie Haskell—whose absolute refusal tobehave in accordance to her appearance (and gender) feels like an act of guerrilla rebellion against the stuffymiddle-class blandness surrounding her. Rhoda Penmark is one of my favorite movie villains. The film positivelydrags whenever she’s not onscreen.

Rhoda has intimacy issues

THE STUFF OF FANTASYNo longer a viable suspense thriller (not for me, anyway), The Bad Seed does work remarkably well as a satiricalblack comedy of American paranoia in the mid-'50s. McCarthyism took root when post-war America was just startingto look within its own backyard for threats to the so-called "American Way of Life." What did it find? Well, juveniledelinquency, for one. And what else is Rhoda but a steely-eyed juvenile delinquent in Mary Janes? (OK, a juvenilehomicidal delinquent, but I’m trying to make a point.) As the perfect little angel who’ll stop at nothing to get thatcoveted Penmanship Medal, Rhoda is unassuming anarchy let loose on the stiff, airless “normalcy” of the falselyidealized world inhabited by the adults.Like many a con man, crooked politician, and gangster throughout history, Rhoda manages to get away with murder(heh-heh) by presenting a false (but reassuring) front of conformity. Everyone is so slow to pick up on the ratherobvious clues of Rhoda’s guilt because….well, little girls just don’t do that. If The Bad Seed were to be remade,possibly with Rhoda's guilt left ambiguous for much of the film, the drama would have to hinge on Rhoda makingpeople uncomfortable by her too-perfect adherence to the image of the "good little girl", or by a reluctance to accepthow she could ever be be anything other than what her image projects. (1985 saw a predictably unsubtle and over-obvious TV remake...a waste of time.)

8/12

Little Rhoda Penmark having one of her "moments"

THE STUFF OF DREAMSIn spite of its daringly original premise and first-class credentials, I’m afraid the movie that once promoted itself as“The most shocking motion picture ever made!” and containing “The most chilling moment the screen has everunleashed!” is now an enduring camp staple, no more frightening and every bit as riotous as this scene of holy terrorJane Withers laying into Shirley Temple in 1934’s Bright Eyes (YouTube link). In her adult years, actress Patty McCormack has embraced the cult/camp status of The Bad Seed and frequentlyappears at screenings, judging Rhoda look-alike contests, and answering questions about the making of the film(her DVD commentary offers a wealth of behind-the-scenes info). Mining the camp-factor, the play version of TheBad Seed has become a favorite of 99-seat theater productions, often with an adult male cast as Rhoda. Peopleseem to have a deep affection for The Bad Seed, either due to childhood exposure to the then-frightening film, or alater-in-life cult appreciation for the way the laughs come at the expense of the film’s sincere over-earnestness and'50s mind-set, not the performances.

9/12

In the Censorship Code sanctioned denouement, Rhoda goes back to the pier toretrieve the coveted Penmanship Medal and gets more than she bargained for. In

the play Rhoda survives while her mother commits suicide.

Some time ago I had the chance to see a stage production of The Bad Seed and was surprised to discover that oneof the big shocker set pieces of the play was a nocturnal walk through the house by a restless Christine after thedeath of Leroy. It’s a stormy night full of thunder and lightning, and as Christine moves to close an open window, aflash of lightning reveals the charred corpse of Leroy lunging out at her. It must have a been a big "gotcha" momentback in its day, but on the night I attended, the actress playing Christine had so much trouble lifting the window blind,she was ultimately obliged to politely hold the stubborn curtain aside to facilitate her own persecution. Mattersweren't helped by Leroy missing his key light, leaving him thoroughly in the shadows, resulting in Christineappearing to be engaged in hand-to-hand combat with her living room curtains.

10/12

More shocking than anything you'll see in the film itself is this bitof mind blowing behind-the-scenes cheesecake showing primNancy Kelly keeping the crew "entertained" between setups

(more likely, giving her gams some air on the hot set).Meanwhile, Joan Croydon (Miss Fern) doesn't seem to be getting

into the spirit of things.

11/12

Hard-to-argue-with logic"But it was his fault. If he gave me the medal like I told him to, I wouldn't have hit

him!"

Copyright © Ken Anderson

12/12

Related Documents