NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 66:3 (2003) 111 Dance in Ancient Egypt Dance in Ancient Egypt By Patricia Spencer By Patricia Spencer The “Scorpion” mace head, depicting dancers performing at a royal ceremony. Three dancers (there may have originally been more) are shown with braided hair. They have one leg raised and would seem to be clapping their hands as they perform.These dancers accompany a scene of the king (named “Scorpion”) ritually breaking soil and were therefore performing in a ceremonial context. Drawing by Richard Parkinson after Marion Cox. A ncient Egypt has left a rich and varied textual legacy. Nevertheless, evidence on dance per se from literary sources is rare, since the ancient Egyptians saw no need to describe in words something that was so familiar to them. There are a number of terms that were used for the verb “to dance,” the most common being ib3. Other terms that describe specific dances or movements are known but unfortunately these often occur simply as “labels” to scenes or in contexts where they say little or noth- ing of the nature of the dance in question. From casual references in literature or administrative documents it is, however, possible to learn something about dance and dancers in ancient Egypt, their lives and the attitudes of the ancient Egyptians towards performers.

Dance in Ancient Egypt

Oct 30, 2014

article about the symbolism of dancing in ancient egypt

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 66:3 (2003) 111

Dance in Ancient EgyptDance in Ancient EgyptBy Patricia SpencerBy Patricia Spencer

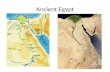

The “Scorpion” mace head, depicting dancersperforming at a royal ceremony. Three dancers (there mayhave originally been more) are shown with braided hair.They have one leg raised and would seem to be clappingtheir hands as they perform.These dancers accompany ascene of the king (named “Scorpion”) ritually breaking soiland were therefore performing in a ceremonial context.Drawing by Richard Parkinson after Marion Cox.

Ancient Egypt has left a rich and varied textual legacy. Nevertheless, evidenceon dance per se from literary sources is rare, since the ancient Egyptians saw noneed to describe in words something that was so familiar to them. There are a

number of terms that were used for the verb “to dance,” the most common being ib3.Other terms that describe specific dances or movements are known but unfortunatelythese often occur simply as “labels” to scenes or in contexts where they say little or noth-ing of the nature of the dance in question. From casual references in literature or administrativedocuments it is, however, possible to learn something about dance and dancers in ancientEgypt, their lives and the attitudes of the ancient Egyptians towards performers.

112 NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 66:3 (2003)

In the popular culture, dance was something people took forgranted and rarely described. This is, of course, not unique toEgypt in antiquity—references to dance in Egypt from theByzantine period to the eighteenth century CE are scarce butthis does not mean that dance had ceased to exist. It was onlywhen European travelers started to visit Egypt and the NearEast and to record the dance that they saw performed inprivate salons, at parties or in the context of weddings or streetfestivals, that Egyptian or other “oriental” dances weredescribed in any detail.

There are many obstacles to attempting to understand thepurpose of dance and the contexts in which it took place inancient Egypt and especially in attempting to reconstruct anyof the movements involved. The same is true of any historicalperiod for which one has to rely on textual and decorativeevidence, but is especially so for ancient Egypt where theconventions for depicting the human form were so stylizedand, essentially, static, that any accurate representation ofmovement was difficult, if not impossible.

Virtually all representations of dancers from ancient Egyptare two dimensional. They come from the walls of temples or

The god Bes dancing andplaying a tambourine.Bes, probably a god ofAfrican origin, wasusually shown as a lion-headed dwarf and wasparticularly associatedwith the warding-off ofevil spirits and thus withthe protection of themother and child duringchildbirth. The Egyptiansbelieved that his dancingand music would driveaway evil spirits and offerprotection to hischarges. Reproducedcourtesy of the Trusteesof The British Museum.

Dancers performing at the Festival of Opet, during which the state god, Amun-Re, traveled in his barque from his home at Karnak to Luxortemple. Photo courtesy of the author.

NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 66:3 (2003) 113

tombs or from depictions on ostraca and papyrus,and they were governed by the artisticconventions of ancient Egypt, which requiredthat the human form be depicted in accordancewith a strict canon that left little room forflexibility or for the artist to use his imaginationand skill to try and show three-dimensionalmovement with any degree of accuracy. There isalso the additional problem that the dancescenes that have been preserved from ancientEgypt were not intended to inform viewers aboutdance, its nature and context, but were carved orpainted on the walls of tombs or temples forpurposes that are not always obvious or even

Banquet scene from the tomb of Nebamun. Two girls are shown dancing accompanied by a group of female musicians. The two dancers aredepicted with much more freedom than was possible for earlier artists and their bodies are almost entwined as they dance and snap theirfingers to the beat of the music. Reproduced courtesy of the Trustees of The British Museum.

Scene from the tomb of lntef at Dra Abu’l Naga. Thistomb scene shows women wearing calf-length dresses,bracelets and anklets, and with white fillets tied aroundtheir long flowing hair, dancing in pairs with a wide rangeof movements, some more elegantly depicted thanothers. After Petrie (1909: frontispiece). Reproducedcourtesy of the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology,University College London.

114 NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 66:3 (2003)

intelligible to modern eyes—forexample, to demonstrate devotionto a cult, to facilitiate entry to thenext world or to show activitiesthat, hopefully, would occur inperpetuity once the deceased hadattained his eternal goal. Most ofthe scenes were never intended tobe seen by more than a handful ofcult devotees, whether of a god ora deceased individual.

With these privisos in mind,however, it is possible to survey whatis known of dance in ancient Egypt,even if a full understanding of itsnature and its context must remaintantalisingly unattainable. It shouldalso be borne in mind that theancient Egyptian civilization lastedfor over three thousand years and,while it is deservedly regarded ashaving been a very “conservative”culture, there must have beenchanges and developments in danceduring that time.

A funeral dance scene from the tomb of Niunetjer at Giza. Three of the dancers hold a throw-stick in their left hands while shaking sistra. (The sistrumis a musical instrument with small metal disks threaded horizontally to form a kind of rattle.) Throw-sticks were used by the Egyptians in hunting, tobring down birds, and their occurrence in dance scenes may indicate origins in a ritual “hunting-dance.” After Junker (1951: Abb. 44).

Acrobatic dancers in the tomb of Kagemni at Saqqara. The young women are shown standing on oneleg and leaning backwards (with the other leg and both their arms raised) to an extent that would bephysically impossible in real life. Reproduced courtesy of the Egypt Exploration Society.

NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 66:3 (2003) 115

The earliest depictions of dance in Egypt are found in rock-art and on predynastic vessels and are described in Garfinkel’scontribution to this issue. Egypt became a unified kingdomabout 3100 BCE and the political and military stability thatfollowed unification led to the flourishing of the distinctivepharaonic civilization and the establishment of the artisticconventions to which all representations of dance in ancientEgypt had to conform. The “Scorpion” mace head showing anUpper Egyptian king of the period just before unificationprovides an early representation of dancers in accordance withdynastic Egyptian artistic conventions. On the mace head thedancers are shown taking part in a royal ceremony and the vastmajority of depictions of dancers from ancient Egypt also comefrom ceremonial religious or funerary scenes.

Funerary DancesChronologically, the next series of dance depictions comes from

tomb-scenes of the Old Kingdom where dancers and singers areshown performing during the funeral procession or at the entranceto the tomb. In this period, these entertainers seem to have beengroups of, presumably, professional musicians and dancers whowere attached to temples, funerary estates and important tombs orcemeteries. The collective name for such a group during the Oldand Middle Kingdoms was the h

˘nr and they would perform at

important festivals as well as funerals. Initially all the members ofthe h

˘nr seem to have been female, with women labeled in tomb

scenes with titles such as “overseer of the h˘

nr” or “inspector of theh˘

nr” showing a high degree of organization and professionalismwithin the group. One Fifth Dynasty lady, Neferesres, had thetitles “overseer of the h

˘nr of the king” and “overseer of the dances

of the king.” The female dominance of the h˘

nr seems to haveended towards the close of the Old Kingdom when maleperformers start to be depicted and male officials are named (Nord1981: 29–38). Usually the dancers depicted in these scenes arefemale, though there are also men and occasionally a dwarf, as in a

well-preserved scene from thetomb of Niunetjer at Giza.The dancers are describedcollectively as ib3wt and theyare accompanied by akneeling group of threefemale singers (h. swt) whoare marking the beat byclapping. The costume of thedancers in this tomb istypical of the period, withshort skirts and crossedbands across their chests.The three dancers are led bya fourth who carries a

sistrum but no throw-stick, and are followed by a female dwarf,who also plays a sistrum. Another three dancers face in theopposite direction and have neither throw-sticks nor sistra. Theentire group may be an attempt to represent (in so far as it waspossible for the Egyptian artist within the prevailingconventions) seven women dancing around the dwarf in theirmidst (Anderson 1995: 2563).

Similar scenes, though the details vary, are found in manyOld Kingdom tombs. The dancers are often shown in rows(though this, of course, may simply reflect Egyptian artisticconventions) and their dance would appear to have been verystylized with a limited number of movements. Many of themovements depicted are “acrobatic” in nature, as in the scenefrom the tomb of Kagemni. Here the dancers are accompaniedby women clapping (and probably singing) as in so many otherfunerary paintings of dancers. In these Old Kingdom tomb scenes,male dancers wear what might be regarded as “everyday” clotheswith a short kilt. Female dancers, however, at a time when mostwomen were depicted with long ankle-length dresses, usually alsowore short skirts, probably to free their legs for the dance.Occasionally they are depicted as if naked, or with just a belt aroundtheir hips. Male dancers have short hair and often so do femaledancers, though some wore their hair long and tied back with a diskat the end of the “pony-tail” to weigh it down and make the hair’smovement more dramatic. There are tomb scenes which showcouples dancing together, often holding hands, but these are alwaystwo men or two women—men and women never dance together.

One of the most uninhibited depictions of dance to havesurvived from ancient Egypt features pair-dancers (see p. 113).The scene originally came from the tomb of Intef (SecondIntermediate period, ca. 1795–1550 BCE) at Dra Abu’l Naga onthe west bank at Luxor but is now preserved in the AshmoleanMuseum, Oxford. The relaxation of rigid state control thatalways occured during an “Intermediate period” (whencentralized government broke down in Egypt) has allowed the

Dancers depicted in the tombof Antefiker at Thebes. AfterNorman de Garis Davies (1920:pls. 23, 23a).

116 NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 66:3 (2003)

artist of this scene the freedom to depict the dancers’ evidentenjoyment of their performance.

In the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2135–1985 BCE) funerary dances,as depicted in, for example, the tombs at Beni Hasan, Meir andDeir el-Gebrawi, also often included movements that wouldseem to our eyes to be more “acrobatic” than representative of“dance” but we should not assume that the ancient Egyptiansmade the same distinction between “dancers” and “acrobats”that we do. One interesting scene in the Twelfth Dynasty tombof Antefiker and his wife Senet at Thebes shows three womenclapping while two groups of dancers move towards each other,in front of the clapping women. Both groups, each made up oftwo dancers, are female but, unlike the clapping women whowear long shifts, they are simply dressed in short kilts and floralcollars. The dancers approaching from the right have short hairwhile the pair coming towards them from the left both have longpony-tails with the weighted disk at the end.

Perhaps the most important of the funerary dances was thatof the Muu dancers, which is attested in scenes from the Old

Kingdom to the end of the NewKingdom (ca. 1069 BCE). They wereoften (though not always) shownwearing distinctive headdresses,which make them instantlyrecognizable.

The story of the Twelfth Dynasty official Sinuhe offers a gooddescription of an Egyptian funeral involving the Muu dancers:

A funeral procession will be made for you on the day of burial,with a gold coffin, a mask of lapis lazuli, heaven above you, youbeing placed in the portable shrine, with oxen pulling you, andsingers going before you. The dance of the Muu will be performedat the entrance to your tomb and the offering list shall be recitedfor you. (Sinuhe, lines 194–195)

There were also dancers who would seem to have beenpermanently attached to the headquarters of the embalmers. Ademotic story of the Ptolemaic period lists “dancers, whofrequent the emblaming rooms” among those to be summonedfor a royal funeral (Spiegelberg, quoted by Lexova 1935: 67–68).

Dancers also played a major role in the funerary rituals ofthe most important of the sacred bulls of Egypt. The Apis andMnevis bulls were accorded royal and divine honors duringtheir l ives and were given elaborate burials in specialcemeteries on their deaths. Their funerals must have rivaledthose of members of the royal family and would have beenprocessional in nature with dancers employed along the route.The dwarf Djeho, who lived during the Thirtieth Dynasty,describes himself on his sacrophagus (Egyptian Museum,Cairo CG 29307) thus:

I am the dwarf who danced in Kem on the day of the burial ofthe Apis-Osiris … and who danced in Shenqebeh on the day of theeternal festival of the Osiris-Mnevis … (Spiegelberg 1929: 76–83;see also Dasen 1993: 150–55 and pl. 26, 2).

The presence of ritual dancers at a funeral, whether for aking, a sacred bull or a private individual, seems to have beenvery important to the ancient Egyptians. The dancers helpedthe mourners to bid farewell to the deceased and alsocelebrated his passing into the next world.

Temple DancesAn early textual reference to a “divine” dance in dynastic

Egypt comes from the well-known letter written by the six-yearold king Pepi II (ca. 2087 BCE) to his official Harkhuf who had

Dances of the Gods

Certain gods and goddesses were particularlyassociated with dance in ancient Egypt. The goddess,Hathor, for example, was, with her son Ihy, associatedwith music and dance and dancers were often describedas having been performing in her honor. Sometimesdancers are shown carrying musical instruments (sistraand clappers) or objects (such as mirrors or menat-collars) that were sacred to Hathor. Another Egyptiangod, the popular Bes, was often shown dancing andplaying musical instruments. This association with Besmay account for the popularity of dwarves in Egyptiandance scenes. Dwarves, as we have seen, werefrequently shown dancing at the funerals of individuals,and they were involved in temple dances.

Muu dancers, with their distinctiveheadresses, as shown in the tomb ofAntefiker at Thebes. These headdresseswere made of woven papyrus stalksand recalled dwellers in the marshy NileDelta where the cites of Sais, Pe andDep were located. After Norman deGaris Davies (1920: pl. 22).

NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 66:3 (2003) 117

led an expedition into what is now Sudan to bring back to thecourt at Memphis a dwarf, in this case possibly a pygmy, for the“dances of the gods.” Harkhuf ’s success in acquiring the“dwarf ” earned him a personal letter of thanks from theexcited young king which Harkhuf proudly had carved on histomb walls:

You have said in this letter of yours that you have brought adwarf for the dances of the god … come north to the palaceimmediately … bring this dwarf with you … alive prosperous andhealthy for the dances of the god, to distract the heart and gladdenthe heart of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt … My Majestywishes to see this dwarf more than the produce of the miningregion or of Punt.

We don’t know exactly what the “dances of the gods” were,but presumably they took place in a religious context, probablywithin a temple precinct. Most Egyptian temples seem to havehad dancers and musicians on their staff. A papyrus from theTwelfth Dynasty temple of Senwosret II at Lahun describes intabular form the occasions on which dances were performedwith the name and nationalities of the singers anddancers/acrobats concerned. From this we learn that thetemple employed Asiatic and Nubian performers, in additionto Egyptians. These dancers were paid to perform at religiousfeastivals to mark the end of the old year, the New Year, thecoming of the annual inundation, the full and new moon andthe feasts of specific gods (Griffith 1898: 59–62).

Most of the rituals of Egyptian state religion took place withinthe temple itself, to which only the priests and the king wereallowed entry, so the temple singers and dancers would haveperformed only for the eyes of the priests and the gods whom theyserved. However ordinary Egyptians were able to watch dances forthe gods on the occasion of public religious festivals, which oftentook the form of processions. It was standard practice at Egyptian

cult temples for the divine image to be brought out of its shrine andcarried out of the temple at the time of important feasts. Usuallyplaced in a sacred barque and carried on the shoulders of thepriests, the divine image would process around the god’s local area,or be taken to visit other gods in neighboring towns. The processionaccompanying the sacred barque included dancers/acrobats as inthe important festivals at Thebes (modern Luxor) in the NewKingdom (ca. 1550–1069 BCE). In addition to the “Festival ofOpet” there was the “Festival of the Valley” when Amun-Re’simage crossed the river Nile to visit the royal mortuary temples ofthe west bank. Scenes of both festivals, depicted in tombs andtemples, show dancers/acrobats accompanying the procession.

The occasions on which dancers, musicians and singersperformed within an Egyptian temple would, presumably, havebeen very formal and, one imagines, somewhat sedate innature. The entertainers would have been called upon topraise the god or goddess at particular festivals throughout theyear and their performances would have been witnessed byonly a small select group of priests and temple officials.However, when the divine image was taken out of the templeat the time of more public feasts, then the entertainers,including dancers and acrobats, who performed as part of thegod’s procession would have been seen by the large crowdswho gathered to watch what must have been one of the mostimpressive occasions in the local calendar. Dancing on suchoccasions, in the open air, might well have been less inhibitedthan it normally was inside the peaceful sanctity of the temple.

Dance in Everyday LifeAlthough most of the depictions of dance which have

survived from ancient Egypt relate to funerary or religiousrituals, there is sufficient evidence to show that dance was notconfined to ritual contexts and played a very real, and important,role in the life of ordinary Egyptians. Ancient Egypt had notheatrical tradition, with the possible exception of mythological

Muu dancers performing at the Delta shrines. Scene from the tomb of Rekhmire at Thebes. The Muu dancers originally represented theancestors of the deceased who greeted the funeral cortege after it had made a sacred pilgrimage to the ancient Delta cities of Sais, Pe andDep. Whether the deceased had actually been taken on the pilgrimage or was just regarded as having done so magically, the Muu performedwhen the funeral procession reached the tomb. After Norman de Garis Davies (1943: pl. XCII).

118 NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 66:3 (2003)

plays performed at religious feasts, and any public entertainmentas such must have been limited in scope at a time when mostpeople probably rarely strayed far from their home town orvillage. Entertainment on festive occasions would have been to alarge extent “homemade” and provided either by members ofthe celebrant’s family or by hiring professional performers.

In addition to scenes of funerary and temple cult dances, theEgyptians also showed dance as it occured in secular situations,particularly in the New Kingdom, essentially at privateentertainments, and it is from these depictions, less rigid instyle and convention than those in formal religious or funeraryscenes, that we can learn most of the context of dance in thelives of ordinary people in ancient Egypt, and can attempt toreconstruct the situations in which dance occurred and thenature of the dance itself. It must, however, always be borne inmind that even these “domestic” scenes served a funerarypurpose since most of them are found on the decorated walls oftombs and depict an idealised view of the next world—a worldin which good living and entertainment was to be anticipated.

Dance in a domestic context is shown in scenes from theOld Kingdom to the end of the New Kingdom. Its absencefrom later tomb decoration is a reflection of the differentnature of funerary decoration after the New Kingdom, whenthe “daily life” scenes that previously had been regarded asessential, were replaced by more religious themes.

Dancers in tomb scenes at private banquets are often shownwith accompanying musicians clapping hands or playinginstruments. The most elaborate of these scenes is that fromthe tomb of Nebamun at Thebes, now in the British Museum.Both dancers shown are virtually naked wearing only a narrowbelt around their hips, and jewelry. In the register above the

dancers and musicians is their audience, who would, of coursehave been on the same level as the dancers—Egyptian artisticconvention could not show them all in one register, as thiswould have obscured parts of or whole figures. Dancers inthese New Kingdom tomb scenes are usually women and themusicians are also often women, though men can be foundplaying to accompany female dancers. The Egyptians seem notto have had any form of musical notation so we cannot knowwhat ancient Egyptian music sounded like, any more than wecan reconstruct dance movements with any degree of accuracy,but percussive instruments certainly played a major role. In theearlier periods, most dancers were accompanied only bypercussive instruments or by clapping. The introduction in theNew Kingdom of a greater variety of stringed instruments,such as the lute and the lyre, would have increased the rangeof music available and may in turn have influenced themovements of dancers.

Although in earlier periods dancers were usually shownwearing skirts or dresses, by the New Kingdom they are morescantilly dressed, often with just a scarf or band around theirhips, though sometimes with what would seem to be adiaphonous robe on top—their bodies are clearly visiblethrough the transparent cloth. Their hair, or a wig, is usuallylong and loose and the dancer’s head could be topped by thecone of scented beeswax, which the Egyptians liked to havemelt over their heads during entertainment. Dancers are alsousually bejeweled, with heavy floral collars, bracelets, ankletsand long dangling earrings. Their eyes are always heavilyoutlined with kohl. The impression is certainly given thatthese are professional performers, dressed for their part.Nubians (from the very south of Egypt or from what is now

northern Sudan) wereoften shown dancingwith other Egyptiandancers or musicians,the difference in skintones being accuratelydepicted. These Nu-bians probably per-formed a different,perhaps more African,dance which mayhave seemed moreexotic to Egyptian

Musicians and a Nubiandancer as shown in thetomb of Djeser-karesoneb. The littledancer, who seemstotally absorbed by herperformance, is nakedapart from her jewelryand floral collar.Courtesy of the EgyptExploration Society.

NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 66:3 (2003) 119

eyes. A famous scene (nowdestroyed) from the tomb ofDjeserkaresoneb at Thebesshows a small Nubian girldancing with a group offemale Egyptian musicians.The scene was a copy of onein the nearby tomb ofAmenhotep-Siese (Davies1923: pl. V), illustrating theway in which Egypt ianart ists often worked from“patterns” with l i t t lef reedom of choice as tosubject matter and sty le .Interestingly the copy in thetomb of Djeserkaresoneb ismore skillfully executed than the original.

Dancers would also have performed out of doors (as indeedthey frequently do in modern Egypt) where there was morespace. A less-rigid outdoor scene is shown in the Theban tombof Huy (reign of Tutankhamun) where a group of women isshown dancing to welcome Huy home from his travels.

Performing out of doors could however lead to problems. Inthe narrow streets of an Egyptian village, spectators (again ascan be seen today) would have crowded into any vantagepoint, often watching from the windows of upper stories orroof-tops. This led to a tragedy at the village of Senepta, nearOxyrhynchus, when an eight-year old slave leaning out from aroof to watch the “castanet dancers” who were performing at a

nearby house, fell to his death(P. Oxy 475; 182 CE).

Itinerant performers arefound in many cultures andare known to have existedin ancient Egypt. A storyabout the divine births ofthe kings of the Fi f thDynasty describes how somegoddesses and a goddisguised themselves as agroup of traveling musiciansand dancers. They carriedwith them clappers andsistra. Although the groupdid not actually perform inthe story, they did assist at

the birth of the triplets who would become the first threekings of the Fi f th Dynasty and were rewarded by thegrateful father with a bag of grain, which they asked to bekept safely for them until they returned from their travels.Since there was no currency in ancient Egypt, itinerantperformers, like everyone else in the country, would havebeen paid “in kind.” Even by the Graeco-Roman period,after money had been introduced into Egypt, payments todancers were still made partly in kind.

Can we say anything of the social status of professionalentertainers, including dancers, in ancient Egypt? Today,professional dancers, though they may be admired for theirskills, are not accorded high status in Egyptian village society.

They travel around, often in thecompany of men to whom theyare not related and may stay awayfrom home at night—behavior onwhich society frowns. The factthat performers in ancient tomb-scenes are sometimes identified inthe accompanying texts asmembers of the tomb-owner ’sfamily might suggest that to be amusician or a dancer was sociallyacceptable, but in such cases,these are unlikely to beprofessional performers. They arerelations of the deceased dancingfor him in private in both his

Dancers welcoming Huy home. Scenein the tomb of Huy at Thebes. At thistime, at the end of the Amarna Period,artistic conventions were more relaxedand the artist took advantage of this totry and give more of an impression ofthe movements of the dancers. AfterNina de Garis Davies (1926: p. XV).

The Depiction of Dancers in Tomb Scenes

Dancers were often depicted, according to Egyptianartistic conventions, in one register while theiraudience was shown in other registers. The audiencecould be made up both of men and women, but theywere seated and grouped separately, with the exceptionof prominent married couples. This should, of course,as with the celebrated scene from the tomb ofNebamun (page 113), be interpreted as a scene ofdancers and musicians in the midst of a party, probablysurrounded on at least three sides by the diners.

120 NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 66:3 (2003)

earthly and his eternal home and they should not beequated with public performers, just as modern Egyptianwomen will dance in the privacy of their own homes fortheir family but would never perform for strangers in public.We must also remember that these tomb scenes were notintended ever to be seen, except by family members bringingofferings to the tomb chapel.

Temple performers—dancers, musicians and singers—wouldhave been accorded high status in line with their dedication tothe service of the gods but it is possible that professionalperformers might not have been so highly regarded in ancientEgyptian society.

Has Ancient Egyptian Dance Survived into Modern Times?

Egypt, as noted above, is a very “conservative” countryand many similarities with ancient activities can still be seenin Egypt, even today. Dancing, with or without engagingprofessional entertainers, was certainly important as a meansof celebration in ancient Egypt as it is in modern Egypt. Onlya drum is needed or, if no instrument is available, a flatsurface, for someone to mark the beat and people will startdancing. Can we make any attempt to interpret themovements and steps of ancient Egyptian dance, and if so,can they be compared with those that can be seen today? In1935 Irena Lexova, the daughter of a Czech Egyptologist,attempted this exercise and her interesting little book on thesubject has recently been reprinted. She makes an importantpoint that must always be borne in mind when trying toassess Egyptian dancing scenes in that the draughtsmenmust often have selected for portrayal those movements andsteps that were the simplest to draw or the most easilyrepresented in accordance with the conventions of Egyptianart. As in the case of the Theban tombs of Amenhotep Si-

Professional Dancers of Ancient Egypt

The best evidence for the lifestyle of professionaldancers comes from late in ancient Egyptian history.A papyrus found at the Graeco-Roman ci ty ofArsinoe descr ibes how a “castanet dancer”(krotalistria) named Isidora was engaged by awoman called Artemisia to perform in her village,together with another dancer:

To Isidora, castanet dancer, from Artemisia of the village ofPhiladelphia. I request that you, assisted by another castanetdancer—total two—undertake to perform at the festival at myhouse for six days beginning with the 24th of the month of Payniaccording to the old calendar, you (two) to receive as pay 36drachmas for each day, and we to furnish you in addition 4

artabas of barley and 24 pairs of bread loaves, and on conditionfurther that, if garments or gold ornaments are brought down, wewill guard these safely, and that we will furnish you with twodonkeys when you come down to us and a like number whenyou go back to the city. (Westerman 1924: 134–44)

A similar papyrus, written some thirty years earlier alsodescribes the engagement of entertainers (this time calledorchstriai) from Arsinoe to perform in the city ofBacchias, interestingly for the same rate of pay (36drachmas a day) as that offered to Isidora a generationlater. It should be noted, however, that this daily rate seemsgenerous compared with the daily average rate (less than 3drachmas) that laborers received at the time. The higherrate of pay for dancers and singers probably reflected theparttime and uncertain nature of their employment.

A professional dancer with the bride’s father at a village wedding inthe Nile Delta in 1993. Anyone who has seen Egyptians dancing forsheer pleasure at village weddings or at street festivals will knowthat, even if the music is different and the movements have changed,the Egyptian joy of the dance, which first developed over fivethousand years ago, is still there for all to see. Photo by Penny Wilson.

Patricia Spencer is SecretaryGeneral of the London-basedEgypt Exploration Society andEditor of the Society’s magazineEgyptian Archaeology. She is theauthor of The Egyptian Temple:A Lexicographical Study andAmara West I and II. Since 1982,she has been a member of theBritish Museum’s excavation teamin Egypt, at el-Ashmunein, TellBelim and (currently) at Tell el-Balamun. It was while attending village weddings in Egyptthat Dr. Spencer became interested in Egyptian dance (bothancient and modern) and she participates regularly inamateur Raqs Sharqi performances in the London area.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Patricia Spencer

NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 66:3 (2003) 121

ese and Djeserkaresoneb, they also would have worked from“patterns” of typical scenes so that there was a limit to thesponteneity possible for the Egyptian artist. Lexova had littleadmiration for or sympathy with the dances of “modern”(1930s) Egypt as witnessed by her and her father, anddismissed any similarity between the dances she hadreconstructed from ancient depictions and what shedescribed as the ‘angular movements in bending of limbs,witnessing to jerky movements” and “those tastelessmovements and postures” of dance as practiced in Egypt inthe twentieth century. Certainly in its most obvious andcommercial form, usually known as “belly-dancing,” dancein Egypt today can seem far-removed from the graceful linesof New Kingdom dancers.

Could anything have survived in Egypt today of thedance depicted on the walls of ancient temples and tombs?This is really impossible to say, though some of the ancientdancers have s imi lar i t ies to per formers of “modern”Egyptian or oriental dancing (raqs sharqi). The emphasis onhip -movements , as shown by the many depict ions inantiquity of dancers with scarves or belts around their hips,for example, is one of the essential similarities betweenancient and modern Egypt ian dancing. However therelat ionship between the hieroglyphic scr ipt andaccompanying scenes must a lways be borne in mind.Figures in Egyptian wall scenes often served as a kind ofpictographic determinative to the accompanying text. Theintention of the artist would, therefore, have been to showa figure that was recognizably “dancing” rather than todepict accurately specific movements as made by genuineperformers . Thus dancers were shown in dist inct ive“dancing” poses, with their arms raised and often with oneleg bent, or one foot resting on its toes as if the dancer wasabout to move. The actual steps and movements of ancientdance in Egypt might have been quite different from thosedepicted in tomb or temple scenes.

Since the time of the pharaohs, Egypt has been subject to agreat deal of outside influence and modern raqs sharqi hasdeveloped over several centuries. In its present form, itreflects the merging of the ancient traditions with those ofthe Arab world, introduced after the coming of Islam toEgypt (641 CE). In recent centuries dance in Egypt, andthroughout the near east, has also been influenced by contactwith “western” music and movement.

Ancient Egyptian art was possibly the least effectivemedium for showing the spontaneity of dance and theenjoyment of its participants. Dance just for the pleasure ofit was hardly ever depicted, but ancient Egypt would havebeen a strange and unusual country if dancing for pleasurehad not existed and despite the conventions of Egyptianart, this love of dancing does sometimes show through.Even the Egypt ian art i s t , governed by his formalconventions and rigid grids, could not totally obscure thespirit of the dance.

ReferencesAnderson, R.

1995 Music and Dance in Pharaonic Egypt. Pp. 2555–68 inCivilizations of the Ancient Near East, Vol. IV, edited by JackM. Sasson. New York: Scribner’s.

Dasen, V.1993 Dwarfs in Ancient Egypt and Greece. Oxford: Clarendon.

de Garis Davies, Nina1926 The Tomb of Huy, Viceroy of Nubia in the Reign of Tutankhamun

(No. 40). London: Egypt Exploration Society.de Garis Davies, Norman

1920 The Tomb of Antefoker Vizier of Sesostris I and of His Wife Senet(No. 60). London: Egypt Exploration Society.

1923 The Tombs of Two Officials of Tuthmosis the Fourth (Nos. 75 and90). London: Egypt Exploratioin Society.

Griffith, F. Ll.1898 Hieratic Papyri from Kahun and Gurob. London: Quaritch.

Junker, H.1951 Gîza X. Vienna: Rudolf M. Rohrer.

Lexova, I.1935 Ancient Egyptian Dances . Prague: Oriental Institute.

(Reprinted: Mineola, New York: Dover Publications 2000).Nord, D.

1981 The Term hnr: “Harem” or “Musical Performers”? Pp. 29–38in Studies in Ancient Egypt, the Aegean and the Sudan: Essays inHonor of Dows Dunham, edited by W. K. Simpson and E. S.Meltzer. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts.

Petrie, W. M. F.1909 Qurneh. London: School of Archaeology in Egypt.

Spiegelberg, W. 1929 Das Grab eines Großen unde seines Zwerges aus der Zeit des

Nektanebês. Zeitschrift für Altägyptischen Sprache 64: 76–83. Westerman, W. L.

1924 The Castanet Dancers of Arsinoe. The Journal of EgyptianArchaeology 10: 134–44.

)

Related Documents