EDUCATIONAL E X P E R I M E N T S COOPERATIVE QUIZZES IN THE ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY LABORATORY: A DESCRIPTION AND EVALUATION Murray S. Jensen General College, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55455 P hysiology educators read journals, such as this one, to gather ideas about curriculum and instruction. Most articles focus on curriculum (i.e., what is taught), but this paper will focus on instruction (i.e., how curriculum is implemented). Just as there are different types of curricula, there are different types of instruction. The most common strategy is lecture. Lectures are extremely efficient for delivering large amounts of information in a short period of time. A common laboratory strategy is discovery or inquiry-based learning (i.e., giving students tools, cognitive and physical, to deduce new information via investigations). A third instructional strategy is the use of cooperative learning. Proper conditions are required for each instructional strategy, and problems arise when the wrong combinations are put together. This paper will describe how a cooperative learning environment can be created in the anatomy and physiology laboratory through the use of cooperative quizzes. It will include a brief introduction to the pedagogical theory behind cooperative learning and an evaluation of the effectiveness of quizzes compared with more traditional methods. AMJ PHYSIOL. 271 (ADK PHYSIOL. EDUC. 16): S48-$54, I996 Key words: cooperative learning; instruction W-IWT IS AND IS NOT COOPERATIVE LEARNING A common mistake in both classrooms and labs is to have students work together on a project and call it cooperative learning. Cooperative learning is only one of three different ways in which students can work in groups. First is the competitive environment. Compe- tition in the lab is automatically set if students are graded on a curve: the success or failure of one student is inversely proportional to the success or failure of the next. When students are required to work in groups in a competitive environment, the question “Why should I help you?” logically arises. Unlessstudents are friends, there is no intrinsic reason to help one another in a competitive environment. The second learning environment is individualistic and is created when students are evaluated by a preset grading criterion (e.g., all individuals scoring 90% or above will receive an ‘ ‘A’ ‘). In the individualistic environment, the successor failure of one student is independent of the success or failure of another. When students are grouped together in an individual- istic environment, they again have no intrinsic reason to help one another. The first two learning environ- ments are the most common in college courses. If no grading information is given during the first day of class, most students perceive the setting to be competi- tive. The third setting is cooperative: the successof any one student is dependent on the success of their partners. When students work in a cooperative envi- ronment they have a vested interest in the perfor- mance of their partners. Instructors are often reluctant to implement coopera- tive grading because it initially seems illogical: the academically motivated will carry less able members 1043 - 4046 / 96 - $5.00 -COPYRIGHT o 1996 THE AMERICAN PHYSIOLOGICAL SOCIETY VOLUME 16 : NUMBER 1 -ADVANCES IN PHYSIOLOGY EDUCATION - DECEMBER 1996 S48 by 10.220.33.2 on October 25, 2017 http://advan.physiology.org/ Downloaded from

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

EDUCATIONAL E X P E R I M E N T S

COOPERATIVE QUIZZES IN THE ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY

LABORATORY: A DESCRIPTION AND EVALUATION

Murray S. Jensen

General College, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55455

P hysiology educators read journals, such as this one, to gather ideas about curriculum and instruction. Most articles focus on curriculum (i.e., what is

taught), but this paper will focus on instruction (i.e., how curriculum is implemented). Just as there are different types of curricula, there are different types of instruction. The most common strategy is lecture. Lectures are extremely efficient for delivering large amounts of information in a short period of time. A common laboratory

strategy is discovery or inquiry-based learning (i.e., giving students tools, cognitive and physical, to deduce new information via investigations). A third instructional strategy is the use of cooperative learning. Proper conditions are required for each instructional strategy, and problems arise when the wrong combinations are put together. This paper

will describe how a cooperative learning environment can be created in the anatomy and physiology laboratory through the use of cooperative quizzes. It will include a brief introduction to the pedagogical theory behind cooperative learning and an evaluation of the effectiveness of quizzes compared with more traditional methods.

AMJ PHYSIOL. 271 (ADK PHYSIOL. EDUC. 16): S48-$54, I996

Key words: cooperative learning; instruction

W-IWT IS AND IS NOT COOPERATIVE LEARNING

A common mistake in both classrooms and labs is to have students work together on a project and call it cooperative learning. Cooperative learning is only one of three different ways in which students can work in groups. First is the competitive environment. Compe- tition in the lab is automatically set if students are graded on a curve: the success or failure of one student is inversely proportional to the success or failure of the next. When students are required to work in groups in a competitive environment, the question “Why should I help you?” logically arises. Unless students are friends, there is no intrinsic reason to help one another in a competitive environment. The second learning environment is individualistic and is created when students are evaluated by a preset grading criterion (e.g., all individuals scoring 90% or

above will receive an ‘ ‘A’ ‘). In the individualistic environment, the success or failure of one student is independent of the success or failure of another. When students are grouped together in an individual- istic environment, they again have no intrinsic reason to help one another. The first two learning environ- ments are the most common in college courses. If no grading information is given during the first day of class, most students perceive the setting to be competi- tive. The third setting is cooperative: the success of any one student is dependent on the success of their partners. When students work in a cooperative envi- ronment they have a vested interest in the perfor- mance of their partners.

Instructors are often reluctant to implement coopera- tive grading because it initially seems illogical: the academically motivated will carry less able members

1043 - 4046 / 96 - $5.00 -COPYRIGHT o 1996 THE AMERICAN PHYSIOLOGICAL SOCIETY

VOLUME 16 : NUMBER 1 -ADVANCES IN PHYSIOLOGY EDUCATION - DECEMBER 1996

S48

by 10.220.33.2 on October 25, 2017

http://advan.physiology.org/D

ownloaded from

EDUCATIONAL E X P E R I M E N T S

of the group, creating academic hosts and parasites. Several hundred research studies, however, show that cooperative groups, when used correctly, improve the academic performance of all individuals and also provide many residual benefits, such as increased communication between students, improved class retention rates, and even improved attitudes toward the subject matter (2).

ELEMENTS OF THE COOPERATIVE LEARNING ENVIRONMENT

There exist several different models of cooperative learning, but two of the more research based are from Slavin (4) from Johns Hopkins, and Johnson et al. (I), from the University of Minnesota. Both maintain that specific conditions or elements must exist in the classroom or lab for the learning to be cooperative. Johnson et al. (1) list five key elements. First, there must exist positive interdependence between stu- dents. All members of a group must be directly linked to the success or failure of their partners. Positive interdependence encourages students to monitor and assist the progress of the other members of the group. The second and third elements are face-to-face promo- tive interaction and the proper use of interpersonal and small-group skills. These items may seem obvious to professors, but for students living in a Beavis and Butthead world, group members frequently do not know how to be complimentary or supportive of each other; therefore, efforts must occasionally be made by the instructor to teach students how to communicate with each other in a positive tone. The fourth element is termed group processing; it involves members of a group talking with each other about how well their group is operating (e.g., what actions of the group were or were not helpful in completing the activities, what processes should or should not be continued next time, and even the possibility of discontinuing the group if major problems exist). The fifth element is individual accountability; this refers to individual students being ultimately responsible for their own learning. This condition can be met by administering tests or other evaluations on an individual basis after group work has been performed.

Many initial attempts at implementing cooperative learning fail because either the positive interdepen- dence or the individual accountability elements are

missing from the assignment. Both elements, how- ever, can be achieved via the use of a testing proce- dure called a cooperative quiz. Although the actual implementation of the cooperative quiz takes only minutes out of the lab period, it sets a cooperative atmosphere for the full lab and, if used on a daily basis, for the whole course.

APPLICATION

The course in which cooperative quizzes were used and evaluated was a human anatomy and physiology lab (GC 1137) taught in the General College at the University of Minnesota. Students in the course are socially and ethnically diverse and are typically afraid of science, afraid of dissections, and even afraid of each other. During each quarter of the academic year, three to five sections of the lab are offered, with each section enrolling between 6 and 14 students. Small class sizes are maintained for two reasons: first, because sections are taught by teaching assistants and, second, for space limitations. The lab focuses on the dissection of the major organs (heart, brain, eye, etc.), some microscope work (histology and some microbi- ology), and a few physiology activities. A five-credit anatomy and physiology lecture course is a pre- or corequiste for the lab. Grading in the lab is divided into three parts: cooperative quizzes, midquarter ex- ams, and final exams. Midquarter and final exams are taken individually and graded on preset criteria. Quiz- zes account for only 20 or 30 percent of the total course grade.

ANATOMY OF A COOPERATIVE QUIZ

The events leading up to a cooperative quiz start at the beginning of the lab session when the instructor sets up a list of objectives (e.g., structures to be identified, procedures to be performed, graphs to be constructed and interpreted, etc.). The list must be clearly commu- nicated to the students, written either on a chalkboard or in handouts. The first lab of the quarter in GC 1137 is an introduction to the microscope; Table 1 shows the list of objectives for the day.

After the instructor shows students what to do (e.g., identifies all the structures and models all of the required procedures), students are divided into groups of two, with maybe one group of three, but never

VOLUME 16 : NUMBER 1 - ADVANCES IN PHYSIOLOGY EDUCATION - DECEMBER 1996

s49

by 10.220.33.2 on October 25, 2017

http://advan.physiology.org/D

ownloaded from

EDUCATIONAL E X P E R I M E N T S

TABLE1 Students’ objectives for microscope lab

Be Able to Identify Be Able to

Stage, ocular, objective lens, illuminator, iris, nosepiece, coarse and fine adjustment, base, arm, “and also the names of your group mem- bers.

1. Properly carry a micro- scope.

2. Focus a microscope using different objectives.

3. Prepare and focus an oil immersion slide.

“This item was used for the first two lab sessions.

more than three per group. On the first day of the quarter, random groups are used, but during subse- quent labs students choose their own partners. Next, the “criteria for success” are set for the cooperative quiz. For example, “Today’s cooperative quiz will involve six questions taken from the objectives (Table 1). Four of the six questions will be individual; that means one of you will be asked to identify a structure or perform a task with no help from your partner. The final two questions will be group questions; your group will have to produce one answer or perform a single procedure. ’ ’ A scoring criterion is then devel- oped (e.g., 6 out of 6 answers correct = 6 points, 5 correct = 5 points, etc.). For weighting purposes, total quiz points do not have to relate directly to the number of questions (for example, answer 5 or 6 out of 6 questions and get 3 points, answer 4 out of 6 questions and get 2 points, etc.). As in most anatomy and physiology labs, cooperative or not, the largest portion of time in the GC 1137 lab is spent on students engaged in activities. Students work in their groups to dissect eyes, brains, etc., or, in our first lab, to operate a microscope. Students are told that when they are ready to take their cooperative quiz they should raise their hands or time limits can be set (e.g., “We’ll start the quizzes in 50 min, ready or not”).

Implementing a cooperative quiz can be done in two different modes. First, the instructor can choose questions from the objectives (Table 1), maybe even targeting more difficult questions at better students; or second, students can select their own questions at random by drawing cards with questions on them from a hat. For example, a card may have written on it “point out the stage of the microscope” or “prepare and focus an oil immersion slide. ” Questions are administered first on an individual basis (e.g., “Jane,

show me the stage of the microscope”) and second, in group form (e.g., “I want both of you to prepare and focus an oil immersion slide”). The last group question is sometimes omitted because the group may have already met the criteria for the maximum points. The final score on the cooperative quiz is given to all members of the group.

After a student has supplied an answer, the instructor has several different response options. Two standard replies sound something like, “Yes, you are correct” or “No, that’s not right.” But two alternative re- sponses are also available. First, the use of wait time, i.e., the instructor remains silent from 3 to 6 s after the initial answer to observe whether the student changes the answer (3). Wait time can be modified by adding negative body language (squinting, for example) in conjunction with a long pause. A second option is to respond to students’ answers with a phrase such as, “Are you sure?” Both wait time and the question, “Are you sure?” are especially effective when a group of students must supply one answer. These alternative responses are also effective at producing tension when students’ initial answers are correct. Eventually, the instructor will have to evaluate the correctness of the response, but much cognitive processing can be detected in the time between a student’s initial response and the final evaluation.

EVALUATION

An evaluation of the cooperative quizzes took place during the 1992-93 and 1993-94 academic years. A comparison was made between students’ perfor- mance in lab sections that used cooperative quizzes and sections that used individual quizzes. Quizzes administered on an individual basis were similar to cooperative quizzes in that both were based on the same learning objectives, contained the same total number of questions, had the same point totals, and were given to students at the end of each day’s activity. In lab sections that used individual quizzes, no regulations were in place either promoting or inhibiting student-student interaction.

Four different lab instructors taught during the evalua- tion period (Table 2). Practice sessions were con- ducted before the beginning of the evaluation to ensure that all instructors were familiar with the

VOLUME 16 : NUMBER 1 - ADVANCES IN PHYSIOLOGY EDUCATION - DECEMBER 1996

s50

by 10.220.33.2 on October 25, 2017

http://advan.physiology.org/D

ownloaded from

EDUCATIONAL E X P E R I M E N T S

TABLE 2 Distribution of students and instructors participating in the evaluation

Instructor Fall 92 Winter 93

Individual Cooperative

Spring 93

Individual

Fall 93

Cooperative

Winter 94

Individual

Spring 94

Cooperative

1 5 14* 12

2 21* 10 10 5 9 3 12 13* 9 6 6 10 4 17* 7 1 6:‘:

Totals 38 27 31 33 18 35

*Instructor taught 2 sections.

individual and cooperative quiz procedures. All instruc- tors were involved with establishing the learning objectives for each lab, and those objectives were strictly maintained for the duration of the study. The decision was made to implement one type of quiz (cooperative or individual) per quarter to prevent conflict between students in different lab sections. Students were included in the study if they missed fewer than three lab sessions and completed all exams. Table 2 outlines the distribution of students included in the study per quarter per instructor.

Evaluations were completed by comparing achieve- ment data for students in lab sections that used the cooperative quizzes and in lab sections that used individual quizzes. Three different variables were used for the analysis. First was student performance on the daily quizzes (cooperative or individual). All instruc- tors were given directions as to the point values and number of questions for each quiz. The first quiz of the quarter was conducted with the instructor choos- ing questions to ask students, but all other quizzes were administered with students drawing question cards from a hat (i.e., random selection of questions). Quiz scores were summed over the quarter and had a maximum of 40 points. The second variable was students’ exam scores. Scores from the two midquar- ter exams and the final exam were summed, with a total of 120 points possible. Midquarter and final exams were administered on an individual basis and were composed of -50% lab practical questions and 50% multiple-choice/fill-in-the-blank questions. The third variable was difference scores derived from an anatomy test given to students on the first day of class and again with the final exam. The anatomy tests contained 45 fill-in-the-blank questions and were used to determine change scores (pretest score to posttest

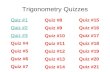

score) to account for students who might have had a similar class in high school. Figure 1 shows an example item from the anatomy test.

Data from sections that used individual and coopera- tive quizzes were compared with the use of t-tests. Results showed sections that used the cooperative quizzes outperformed sections that used individual quizzes in both exam scores and anatomy gain scores (Table 3). No statistical differences were detected for quiz scores. A ceiling effect was detected in the quiz data for both cooperative and individual sections (average score = 38 out of 40 maximum points), indicating that students using either type of quiz

28 FIG. 1.

Example item from the anatomy test.

VOLUME 16 : NUMBER 1 - ADVANCES IN PHYSIOLOGY EDUCATION - DECEMBER 1996

$51

by 10.220.33.2 on October 25, 2017

http://advan.physiology.org/D

ownloaded from

EDUCATIONAL E X P E R I M E N T S

TABLE 3 Results of the t-tests comparing cooperative

to individual quiz sections

Variable Section n Mean Std. t

Dev. Value P

Exam score Cooperative 95 89.32 18.50 2.82 0.005 Individual 87 82.47 14.09

Anatomy gain Cooperative 95 35.11 29.85 2.54 0.013 score Individual 87 27.23 24.74

Quiz score Cooperative 95 38.03 1.76 -0.14 0.890

Individual 87 38.07 1.88

Std. Dev., standard deviation.

found them easily mastered. Results from students’ performance data support the use of cooperative quizzes over individual quizzes.

Informal evaluations of the two treatment groups were conducted by interviewing lab instructors and comparing students’ end-of-the-quarter course evalua- tions. All instructors reported more talking between students in sections that used the cooperative quizzes. Conversations typically centered on the day’s activi- ties and the preparations required for the quiz, al- though informal discourse was also common. Instruc- tors also reported that students in cooperative sections spent a large portion of their time rehearsing for quizzes via drill and practice sessions conducted between group members. Students in individual sec- tions also rehearsed for quizzes, but typically did so by going over the questions silently. Students’ lab evalua- tions (see APPENDIX 1) were completed anonymously and were not used for any inferential statistics. Data from those evaluations showed the majority of stu- dents in both treatment groups having a positive experience in the lab and agreeing that the use of the daily quizzes (cooperative or individual) was an effec- tive preparation device for exams. Of the students in the cooperative sections, 83% reported that the use of the cooperative quizzes should be continued in the lab, whereas 58% of students in the individual sections agreed that daily individual quizzes should be contin- ued. Sixty percent of the students in the cooperative sections reported “group studying” at least once for an exam, whereas only a few students (21%) from individual sections reported studying in groups. This investigation, however, does not have any data as to the effectiveness of studying in groups outside of class

in preparation of exams. Results of this study can report only that group studying was more frequent in the cooperative learning sections and that students in those sections scored higher on exams than did students in the individual learning sections.

DISCUSSION

Results of the investigation show two benefits to using cooperative quizzes in conjunction with individual exams in the anatomy and physiology lab. First, students in the cooperative sections performed better on large exams than students in sections that used individual quizzes. The second benefit was that, by implementing cooperative quizzes, two of the more difficult elements of cooperative learning were met: positive interdependence and individual accountabil- ity. Positive interdependence was met via the sharing of one common quiz grade. It is important to note that the magnitude of the shared grades was relatively small, only about 30% of the total course grade, but yet was large enough to stimulate students to be inter- ested in each other’s learning. Because of the shared grades, students paid close attention to each other’s progress and frequently taught one another the mate- rial (i.e., reciprocal teaching). Individual accountably was promoted in two ways: first, by having the largest component of the cooperative quiz administered individually and, second, by administering exams individually. Each student was ultimately responsible for all the course material, thus no one could succeed in the class just by riding the success of the group.

CONCLUSION

This study is only one of hundreds or perhaps even thousands that supports the use of cooperative educa- tion (2). It is unique, however, in that it shows how cooperative quizzes can be used in the anatomy and physiology lab and also how the environment pro- moted by the quizzes fulfills at least two of the conditions for a cooperative learning atmosphere. Cooperative learning environments are difficult to create, but implementing cooperative quizzes can provide a simple method that promotes the condi- tions required for a cooperative learning environment.

Cooperative quizzes work well in situations where a predefined list of objectives can be developed. Our

VOLUME 16 : NUMBER 1 - ADVANCES IN PHYSIOLOGY EDUCATION - DECEMBER 1996

S52

by 10.220.33.2 on October 25, 2017

http://advan.physiology.org/D

ownloaded from

EDUCATIONAL E X P E R I M E N T S

efforts to use cooperative quizzes in other labs have met with mixed results. For example, the quizzes work very well when students are learning how to perform a series of procedures, such as setting up an experiment (e.g., “Joe, what are the dependent and independent variables?“) or learning how to run a computer program (e.g., “Sarah, show me how to transfer the data to the spreadsheet”), but have had poor results when the lab activities potentially possess large amounts of experimental error. When no preset list of objectives is produced for a laboratory exercise, we omit any type of daily quiz for that lab.

Lists of learning objectives in our classes were rela- tively short, and students typically mastered them, as indicated by the threshold effect in both cooperative and individual learning sections’ quiz scores. If objec- tive lists are extensive, more stress is added to the cooperative group dynamics. Long lists of objectives are not necessarily inhibiting to the group, but we have found that groups work best when they initially experience a high degree of success, and then, as the course progresses, we challenge them more and more. If the cooperative groups initially fail at produc- ing good quiz scores, students will be skeptical of the utility of working together. If the lists of learning objectives are excessively long, one possibility is to create a subset of items for the cooperative quiz and then have the complete list required for the larger exams.

We have found that the combination of cooperative quizzes and individual exams works best when preset grading criteria are used to determine final grades. If a standard curve were used, students would have been more reluctant to assist one another (e.g., one stu- dent’s ability to earn an “A” reduces the chances of the next student to earn an “A”). Because students were graded on preset criteria, students could help each other prepare for exams without being penalized for the success of their partners.

APPENDIX 1

The following questions were extracted from the lab evaluations completed by students at the end of the quarter. The evaluations were completed anonymously, thus there were a few students in each treatment group whose data are included in the following table but who were excluded from the performance analysis because they did not meet the minimum criteria for inclusion.

How would your rate your overall experience in this lab?

very Positive Neutral Negative very To- Positive Negative tals

Cooperative 37 (36%) 28(27X) 18 (17%) 12 (12%) S(S%) 103 Individual 30 (32%) 31 (33%) 12 (13%) 12 (13%) lO(ll’%) 95

How would you rate the effectiveness of the cooperative quizzes in preparing you for exams? (This question was posed to students in sections that used cooperative quizzes.)

very Inef- very

Effective Effective Neutral

fective Inef-

To-

fective tals

Cooperative 41 (40%) 30(29%) 16(16x) lO(lO%) 6(6x) 103

How would you rate the effectiveness of the daily quizzes in

preparing you for exams? (This question was posed to students in sections that used individual quizzes.)

very Inef- very

Effective Effective Neutral

fective Inef-

To-

fective tals

Individual 25 (27%) 32 (33%) 16 (17%) 8 (8%) 14 (15%) 95

Should cooperative quizzes be continued in this course? (This question was posed to students in sections that used cooperative quizzes.)

Yes No Totals

Cooperative 85 (83%) 18 (17%) 103

Should individual quizzes be continued in this course? (This question was posed to students in sections that used individual quizzes .)

Yes No Totals

Individual 55 (58%) 40 (42%) 95

VOLUME 16 : NUMBER 1 - ADVANCES IN PHYSIOLOGY EDUCATION - DECEMBER 1996

s53

by 10.220.33.2 on October 25, 2017

http://advan.physiology.org/D

ownloaded from

EDUCATIONAL E X P E R I M E N T S

I met with other members of the class outside of class time to prepare for at least one exam,

Yes No Totals

Cooperative 62 (60%) 41 (40%) 103 Individual 20 (21%) 75 (79%) 95

Address for reprint requests: M. S. Jensen, University of Minnesota, 220 Appleby Hall, 128 Pleasant St., SE, Minneapolis, MN 55455 (E-mail: jenseOO5Qmaroon.tc.umn.edu).

Received 16 February 1996; accepted in final form 21 August 1996.

References

1. Johnson, D. W., R. T. Johnson, and K. A. Smith. Active

Learning: Cooperation in the College Classroom. Edina, MN: Interaction Book, 199 1.

2. Johnson, D. W., and, R. T. Johnson. Cooperation and

Competition: Theory and Research Edina, MN: Interaction Book, 1989.

3. Rowe, M. B. W ar ‘t t ime: slowing down may be a way of speeding up. J. TeacberEduc. 37: 43-50, 1986.

4. Slavin, R. Cooperative Learning. New York: Longmans, 1980.

VOLUME 16 : NUMBER 1 - ADVANCES IN PHYSIOLOGY EDUCATION - DECEMBER 1996

s54

by 10.220.33.2 on October 25, 2017

http://advan.physiology.org/D

ownloaded from

Related Documents