CHAPTER THIRTEEN 1 USING SOCIAL MEDIA 2 TO BUILD HIDDEN SCREEN HISTORIES: 3 A CASE STUDY OF THE PEBBLE MILL PROJECT 4 VANESSA JACKSON 5 6 7 8 Web 2.0 (O’Reilly 2005) is impacting the landscape of television history 9 in new and often under researched ways. The rise of digital technologies 10 has meant that the screen archive has frequently been taken outside the 11 institutional domain by fans and enthusiasts, becoming an interactive 12 repository: a place for memories, comment and discussion, as much as a 13 site for preservation. 14 Through a case study of the Pebble Mill Project, an online archive 15 documenting production at the now defunct BBC studio, this chapter will 16 explore the impact of digital technologies on television archives, 17 examining how unofficial, community based archives have emerged 18 online. I will argue that online and especially social media allow us to 19 access television histories which otherwise might never be told, and that 20 they do this by widening the selection of whose views and memories can 21 be heard, and preserving ephemera perhaps deemed unworthy by 22 institutional archives. Questions are raised with a wider relevance: issues 23 concerning the rise of the citizen curator, the accuracy of recalled memory, 24 the nature of collaborative reminiscence, the motivation behind 25 contributing to such collections, as well as the challenges of intellectual 26 property protection, and what the potential of online community archives 27 might hold for television historians. 28 I will begin by outlining the project itself, examining how it sits in 29 relation to traditional television histories, before teasing out some of the 30 possibilities of online, interactive archives. Later in the chapter, I will 31 explore in more depth some of the successes, limitations and challenges of 32 the Pebble Mill Project, which are reflective of issues surrounding online 33 archives in general. 34

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

CHAPTER THIRTEEN 1

USING SOCIAL MEDIA 2

TO BUILD HIDDEN SCREEN HISTORIES: 3

A CASE STUDY OF THE PEBBLE MILL PROJECT 4

VANESSA JACKSON 5

6 7 8 Web 2.0 (O’Reilly 2005) is impacting the landscape of television history 9 in new and often under researched ways. The rise of digital technologies 10 has meant that the screen archive has frequently been taken outside the 11 institutional domain by fans and enthusiasts, becoming an interactive 12 repository: a place for memories, comment and discussion, as much as a 13 site for preservation. 14

Through a case study of the Pebble Mill Project, an online archive 15 documenting production at the now defunct BBC studio, this chapter will 16 explore the impact of digital technologies on television archives, 17 examining how unofficial, community based archives have emerged 18 online. I will argue that online and especially social media allow us to 19 access television histories which otherwise might never be told, and that 20 they do this by widening the selection of whose views and memories can 21 be heard, and preserving ephemera perhaps deemed unworthy by 22 institutional archives. Questions are raised with a wider relevance: issues 23 concerning the rise of the citizen curator, the accuracy of recalled memory, 24 the nature of collaborative reminiscence, the motivation behind 25 contributing to such collections, as well as the challenges of intellectual 26 property protection, and what the potential of online community archives 27 might hold for television historians. 28

I will begin by outlining the project itself, examining how it sits in 29 relation to traditional television histories, before teasing out some of the 30 possibilities of online, interactive archives. Later in the chapter, I will 31 explore in more depth some of the successes, limitations and challenges of 32 the Pebble Mill Project, which are reflective of issues surrounding online 33 archives in general. 34

Chapter Thirteen

240

Pebble Mill and the Pebble Mill Project 1

Until the building’s demolition in 2005, BBC Pebble Mill was the 2 production and broadcast centre for the Midland region. It opened in 1971 3 as the first purpose built radio and television broadcasting centre in 4 Britain, and played an important part of the BBC’s vision of “Broadcasting 5 in the Seventies” (BBC 1969). At its height in the 1970s and 1980s, 6 Pebble Mill produced a significant amount of BBC television output, 7 dramas like Nuts in May (Leigh 1976), and Boys from the Blackstuff (BBC 8 1982), daytime programmes like Pebble Mill at One (BBC 1972-86), and 9 factual series like Top Gear (BBC 1977- ), Countryfile (BBC 1988 10 ongoing) and Gardeners’ World (BBC 1968 ongoing). Many of the 11 programmes produced, particularly the factual series and studio shows, 12 were seen as ephemeral by the BBC, and were not necessarily preserved. 13

Pebble Mill had a significant impact on the Midlands’ cultural 14 landscape, frequently giving a non-metropolitan perspective through 15 dramas and factual programmes of life outside London. The closure of 16 Pebble Mill in 2004, and the move in 2012 of all BBC Birmingham’s 17 factual series to BBC Bristol, seriously eroded the television production 18 base in the region, leading to a loss of jobs in the Birmingham creative 19 sector, and frequently a sense of bitterness from many former employees, 20 as has become apparent through the project. I began the Pebble Mill 21 Project in 2010, with the purpose of celebrating and documenting the 22 programme making heritage of Pebble Mill

1. At the heart of the project are 23

a website, http://pebblemill.org, and an associated Facebook group. The 24 website receives around 400 hits a week, with most of the traffic directed 25 via Facebook links. The site includes video interviews with programme 26 makers, editors and designers, as well as photographs and written 27 memories. Pebble Mill is often remembered nostalgically by former 28 members of staff, myself included, and many keep photographs which 29 they are happy to share on the website. I post blogs regularly on the site, 30 and by linking, remediate them to the ancillary Facebook group. The 31 group has almost 1,200 Facebook “friends”, who have proved an 32 invaluable resource, adding comments about working on productions, 33 identifying photographs, posting their own photographs, and invoking 34 memories in others. Often, a conversation is sparked on the Facebook 35 group about a programme or a production method, which I then copy and 36 preserve on the website. A culture has grown up around the site itself, and 37

1 The Pebble Mill Project was the recipient of a Screen West Midlands Digital

Archive Fund grant.

Using Social Media to Build Hidden Screen Histories 241

codes of practice have evolved naturally, for example, members 1 themselves “police” the Facebook group, and ask for any irrelevant posts 2 to be taken down. 3

Traditional TV histories 4

Helen Wheatley provides a taxonomy of the different approaches that 5 television histories can examine, including the meta-narratives of 6 television as an institution; the micro histories of making programmes; 7 viewing in relation to social or political change; form, aesthetics and 8 representations; and the technological history of television (2007, 7). The 9 Pebble Mill Project addresses most of Wheatley’s categories, aside from 10 exploring viewing in relation to change, because the site concentrates on 11 the programme makers, rather than audience impact. The posts, and 12 readers’ responses to them, can tell us much about BBC production in 13 Birmingham as an institution, its culture and working practices; although 14 we must be conscious that the official BBC perspective tends not to be 15 presented, and we are therefore only seeing a partial picture. The project is 16 adept at detailing the making of television, giving programme makers the 17 opportunity to talk about how specific series were produced. We can 18 access voices, which are unlikely to be included in an institutional archive, 19 for instance crew who worked on a particular show. Representation can 20 certainly be addressed on the site, and it has, for instance, been particularly 21 gratifying to hear from some of the families of contributors from impactful 22 documentaries like Philip Donnellan’s film, The Colony (BBC 1964), an 23 early example of West Indian immigrants’ experiences of life in the West 24 Midlands, told through their own voices. The technological history of 25 television is frequently demonstrated on the site. Engineering and post-26 production staff are well represented in the Pebble Mill Facebook group, 27 and actively contribute, prolifically documenting their working lives 28 through photographs. This is particularly fruitful when illustrating how 29 production and broadcasting technologies have developed. That the Pebble 30 Mill Project can address most approaches to historical television research 31 goes some way to demonstrate that online and social media can be a 32 valuable tool in creating a historiography of production, particularly if 33 used alongside institutional archives. 34

Catherine Johnson argues that the huge volumes of the most everyday 35 television programmes are difficult subjects for historians; they come 36 without critical acclaim and often with questions regarding quality, 37 particularly in relation to aesthetics (2007, 65). However, it can be said 38 that all television programming is transient and of the moment: broadcast, 39

Chapter Thirteen

242

viewed and then discarded to be replaced by the next transmission; this 1 was particularly true in the 1970s and 1980s, when Pebble Mill was at its 2 height, although arguably less so in the digital age, with the changes in the 3 way that people consume TV. Are only those programmes with the highest 4 production values, the biggest budgets, the most critical acclaim, to be 5 considered by television historians? What makes one programme worthy 6 of attention over another? Is it the audience size, the fact that some erudite 7 critic deems it to have value, or that the production company or 8 broadcaster has thought fit to archive it? It can be argued that researching 9 the most ubiquitous of television programmes has a value, particularly in 10 terms of understanding the production culture, the economies of scale, the 11 pressures of delivery and the relationship between production teams and 12 craft roles in programme making, as well as exploring how these 13 programmes were consumed and by whom (Bonner 2003). There is no less 14 effort for the production team in making a low budget programme than a 15 high end one. Frequently, producers and directors have to think more 16 creatively to make a less well funded programme look as good as possible, 17 and deliver within a tighter timeframe. The series that are uppermost in the 18 memories of the programme makers are not necessarily those that 19 academic television historians canonise, but those where a new piece of 20 technology was implemented, where a particular incident happened, or 21 perhaps those that ultimately failed, and such programmes seem worthy of 22 academic attention. 23

With the exception of some of the dramas made at BBC Pebble Mill, 24 for example Nuts in May, Boys from the Blackstuff, and Penda’s Fen 25 (BBC 1974), many of the centre’s productions did not enjoy critical 26 esteem at the time of transmission, and have remained beneath the radar of 27 most television historians. Output consisted largely of both live and 28 recorded daytime studio programmes, like Pebble Mill at One, Good 29 Morning with Anne and Nick (BBC 1992—6), Call My Bluff (BBC 30 1996—2005), Style Challenge (BBC 1996—8) and Going for a Song 31 (BBC 1995—9), as well as long running factual series for both daytime 32 and primetime, such as Gardeners’ World, Countryfile, Top Gear, Real 33 Rooms (BBC 1997—2002), The Clothes Show (BBC 1986—2000), and 34 the programming of the Multicultural Unit, later becoming the Asian 35 Programmes Unit. If television historians neglect the programmes 36 produced by centres like Pebble Mill, then much will be lost; both 37 knowledge of those everyday series and perhaps, more importantly, of the 38 culture of network production in some English regions in the latter part of 39 the twentieth century. Since many of the programmes made at Pebble Mill 40 no longer exist, due to tapes being recorded over or discarded, the 41

Using Social Media to Build Hidden Screen Histories 243

programme makers are an invaluable resource, with their memories, 1 photographs and documents, and one that digital Web technologies make 2 easy to access. 3

Digital technologies provide new opportunities 4

Web 2.0 (O’Reilly 2005) refers to the contemporary, communal Internet 5 and websites which, unlike their static predecessors, utilise digital 6 technologies to allow for interactivity and collaboration. Social media 7 sites, like Facebook, are prime examples of the way in which Web 2.0 8 provides new opportunities for online community building and creation: 9 end-users can interact, comment, or post an artefact, whether that is a 10 photograph, an audio or video clip, or a piece of writing. Media 11 production, and indeed archiving, is therefore no longer the preserve of 12 production companies and broadcasters: 13

A shift in power relations is occurring, such that the powerful archiving 14 force of the institution (museum, government, church, law or mass media) 15 and corporations that may seek to preserve knowledge and history on their 16 own terms seems to be challenged by the personal archiving power of 17 increasingly popular and easy-to-use digital media (Garde-Hansen 2009, 18 147-8). 19

The advances in digital technologies have allowed for interactive and 20 community archives to emerge, outside of any institutional control, in a 21 way that was not previously possible. It is this potential for interactivity, 22 and the empowerment of the individual outside of the institution that 23 makes for exciting opportunities. The importance of the individual should 24 not be underestimated here, the technological possibilities require human 25 participation to make use of them and to orchestrate the conversation with 26 fellow enthusiasts. It is this combination of social and technological 27 factors that is important; having the means of expression is pointless if you 28 have nothing to say, and no one to share it with (Leadbeater 2008). 29

It is the ability to consult with a diverse but well-informed community, 30 each member with their own piece of the jigsaw, that is significant for the 31 Pebble Mill Project. Most members of the Facebook group were staff at 32 BBC Pebble Mill, but other contributors include relatives of people who 33 worked there, academics and historians, those interested in the Birmingham 34 cultural scene, and people who simply enjoyed the programmes. Facebook 35 is adept at constructing imagined communities, and the group is predicated 36 on a shared identity, through members’ association with the project. Many 37 members knew each other in their working lives at Pebble Mill, and for 38

Chapter Thirteen

244

them the group has become a valuable tool for social interaction. Several 1 people have been in contact to thank me for creating the website and 2 Facebook group, which have enabled them to get back in touch with 3 former colleagues they have not seen or heard from in a number of years. 4 This is an example of “maintained social capital”, where valuable 5 connections are reinstated, even when one’s life has progressed, and 6 previous social ties are severed (Ellison, Steinfeld and Lampe 2007, 3). 7 Online social networking tools can re-ignite these connections in a way in 8 which is socially beneficial to those involved, but that also can have a 9 wider purpose, for example, in allowing the collaborative building of a 10 memory or archive. 11

Perhaps a more surprising, and potentially more “revolutionary” aspect 12 of Internet technology, than the project’s potential for reconnecting old 13 friends, is the trust and co-operation that has grown between people in the 14 group who did not know each other previously, and the connections that 15 are formed through their shared enthusiasm. This resonates with studies of 16 interaction via social media, for example see Putnam and Feldstein (2003, 17 227). For instance, I am now in regular on and off-line contact with a 18 number of prolific contributors to the website and Facebook group, whom 19 I did not know before the inception of the project. It is difficult to imagine 20 how these ties could have been nurtured efficiently before the advent of 21 social media, as group participants are so widely geographically scattered, 22 with people accessing the site from as far afield as India, Australia and the 23 United States as well as those across Europe and specifically from the 24 United Kingdom. Although the primary purpose of the project was to 25 create an interactive and democratic archive of programme making at the 26 BBC in Birmingham, this positive social aspect, the building of an online 27 community, has been an unintentional but interesting development. 28

What does a television archive mean in an online world? 29

The traditional television archive is deeply entwined in issues of 30 institutional power (Spigel 2010, 55); artefacts are selected as worthy of 31 inclusion by some quality threshold not normally visible to outsiders. 32 Materials are catalogued, preserved and made accessible (or not), by the 33 institution and its stewards. From an institutional perspective this control 34 makes perfect sense: there are commercial, ethical and legal considerations, 35 as well as issues surrounding copyright. It is a “top-down” approach, 36 ordered and rule driven, and the traditional archive is a physical space, a 37 repository for items such as film, tapes, production files and documents. 38 Digital interactivity democratises the archive in a way that is difficult for 39

Using Social Media to Build Hidden Screen Histories 245

institutions to control. The amateurisation, and subsequent lack of archival 1 process causes issues for television historians. As Lynn Spigel has 2 suggested, sites like YouTube which fail to provide vital programming 3 information such as original broadcast channels or dates, complicate or 4 otherwise ignore the wider contexts of the programmes they hold clips 5 from (Spigel 2010, 65). 6

Conversely, the digital archive opens up previously untapped 7 possibilities that can both change and enrich the television historian’s 8 view. What is worth preserving and discussing is no longer at the 9 institutional archivist’s discretion, but is now under the control of a 10 collaborative online community. The relationship of personal memory and 11 television history comes in to effect here. As Spigel suggests: “As the 12 archive goes viral, the nature of television history changes not only 13 because of what is available, but also because of well-entrenched tastes 14 and presuppositions about what counts as official history and what counts 15 as popular memory or nostalgia” (Spigel 2010, 70). This observation is 16 very relevant to the Pebble Mill Project. The majority of the artefacts 17 displayed on the site would never have been archived in the traditional 18 sense. Whilst some of the photographs, such as publicity stills, or records 19 of studio sets were taken in a professional context, many more are simply 20 informal shots of friends at work. Alongside the stills, blogs written by 21 former staff at BBC Pebble Mill make up most of the content of the site. It 22 is this access to personal memory and first hand testimony that makes the 23 site so rich in terms of anecdotes and opinion, and it is particularly the 24 interplay between posts on the site and the associated discussions on the 25 Facebook group, that provides a potentially important record of ephemeral 26 television series not otherwise deemed worthy of inclusion in the canon of 27 historically significant programmes preserved by the BBC. Production and 28 broadcast technologies and how they evolved, adapted and changed, along 29 with the culture of working in television production during the second half 30 of the twentieth century are also captured in the project, and are frequent 31 topics of conversation within the online community. This community 32 created archive does what Susan Douglas (2010) suggests: it is 33 complementary to the traditional institutional collection, rather than 34 duplicatory; it documents and records different materials, and tends to be 35 more centred on the people involved in production and their memories, 36 rather than the official documentation around the output and the 37 programmes themselves. 38

I would argue that there are different motivations behind the institutional 39 and online community archive. Whilst both aim to preserve artefacts, what 40 they determine worthy of preservation differs. The institution has to be 41

Chapter Thirteen

246

careful to preserve its image and brand, selection has to be made due to 1 space restrictions, and issues of “quality” programming and reputation 2 have to be addressed and prioritised. The number of visitors to the archive 3 and its ease of use are perhaps secondary concerns. For the online 4 community archive, like the Pebble Mill Project, viability is determined 5 by its usage and accessibility. It needs visibility and support to build its 6 archive and serve its community, and as it is not run by a professional 7 archivist, it is perhaps less focussed on the categorisation and preservation 8 of the physical artefact, which indeed, it may not actually hold. Equally, 9 the online community archive has, because of its interactivity, the ability 10 to develop organically in response to community interest; it is shaped by 11 its users, and is not a static entity. 12

The opportunities which digital technologies provide cause us to 13 question who the archivists are, and what online archives might consist of. 14 We have seen the rise of the “citizen journalist”, and we are now perhaps 15 seeing the rise of the “citizen curator”. In receiving artefacts, particularly 16 photographs, from the Pebble Mill community to place on the website, it is 17 possible to see a pattern in who contributes, and what type of material they 18 choose to share. We can divide the photographs contributed into three 19 categories: those taken as a requirement of someone’s job, those taken 20 informally to document programmes or working environments, and snaps 21 of friends at work. Included in the first category are publicity stills taken 22 by professional photographers, particularly of dramas, used to promote 23 forthcoming programmes in the press. Also in this category are 24 photographic records of sets and lighting rigs taken by designers, as well 25 as Polaroids taken by costume and make-up for continuity reasons. There 26 is a wealth of this kind of material on the Pebble Mill website. 27

The second category of photographs were often taken by staff, not as 28 part of their job, but recording for themselves to document programmes 29 they were working on, or machinery they were using. The majority of the 30 photos submitted are from former post-production staff, documenting the 31 equipment they used and the editing suites they worked in. It is unclear 32 why post-production workers chose to take more photographs than other 33 craft staff, whether it is related in some way to the nature of their work, or 34 the culture of the department, or indeed simply because of the particular 35 individuals that are in the group. I rarely receive photographs from 36 producers, it was much more common for former production assistants or 37 other, more junior, members of teams to take photographs. This task was 38 not expected or required of production teams, and producers would 39 probably be preoccupied by the shoot itself and have little time for taking 40 photos. 41

Using Social Media to Build Hidden Screen Histories 247

The third category of more casual photographs again tends to be 1 dominated by post-production staff, as well as design crews and some 2 production teams. These photographs of parties, of informal gatherings in 3 the bar or canteen, or of fun on location are perhaps less interesting from 4 the point of view of documenting the programme making itself, but tell us 5 much about the culture of a relatively stable workforce who knew each 6 other well, and developed lasting friendships. 7

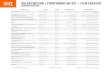

In terms of written blogs on the website, the contributors are often 8 former engineering or post-production staff; sometimes writing about 9 working on a particular programme, or documenting the technology used 10 in a particular era, or reminiscing about their career at Pebble Mill. Blogs, 11 and even short written comments, can prove a worthwhile resource, 12 frequently providing a wider context and arguably more value than 13 photographs alone can give. Assigning significance to particular artefacts 14 is something that an institutional archive does habitually, in contrast to 15 online community archives, which allow for a conglomeration of material, 16 easily accessible and searchable, but where users must employ their own 17 judgment and interest in valuing the contributions. However, adding value 18 to an original post is something that online communities can accomplish 19 with ease. The following exchange posted on the Facebook group in 20 response to a photograph (see Fig. 13-1) of the crew of the 1980’s drama, 21 Morte D’Arthur (BBC 1984), pictured with a studio camera, an EMI 2001, 22 illustrates how the process can work: 23

24 Lighting director: 25 Looks like a 2001 - nasty things! 26 27 Engineer: 28 Nasty things? From what I heard, once they were lined up they stayed lined 29 up, not like the Links that needed realigning twice a day! 30 31 Lighting director: 32 Just stirring it! I never liked the tinted-monochrome feel of the EMIs but I 33 was a voice crying in the wilderness when I arrived at Pebble Mill in 1984. 34 Criticising the EMI 2001 was not a move guaranteed to endear me as the 35 new boy. 36 37 Cameraman: 38 Ask any cameraman who worked during the 70’s or 80’s what was the best 39 camera to operate, and the EMI 2001 would come out tops. 40 41

Chapter Thirteen

248

1 Fig. 13-1: The crew of Morte D’Arthur. © Willoughby Gullachsen 2 3 We hear three different perspectives, from skilled craftsmen, each with a 4 valid reason for their view. It would be impossible to anticipate such a 5 conversation happening offline, and therefore difficult to capture it using 6 another method—for example via interview—and yet this is the type of 7 encounter which happens organically in a social media context. The 8 comments tell us much about the production culture, they hint at the 9 rivalry between different specialisms within the crew, as well as 10 displaying their professionalism, and the importance of fitting in and being 11 accepted. Such spontaneous conversations cannot be predicted, but 12 capturing them does add to our understanding of screen histories in ways 13 that would be difficult without social media. 14

Occasionally, I post a photograph on the website for which I have very 15 little information, and the Facebook group are invited to identify what a 16 particular piece of equipment was and discuss the working practices 17 surrounding it: in effect crowd sourcing information. Usually, within a 18 remarkably short space of time, interesting and informative comments are 19 posted. A case in point is the following response to a photograph of an 20 editing block used on two-inch videotape in the 1960s and 1970s (see Fig. 21 13-2): 22

23 Videotape editor: 24 It is indeed a 2” Quad editing block. The magnetic recording was revealed 25 by applying iron filings onto the tape and then viewed through a 26 microscope to find the correct place to cut and splice the tape to make a 27 synchronous join. 28

Using Social Media to Build Hidden Screen Histories 249

Sound recordist: 1 If I remember correctly the sound edit was at a different point from the 2 video, making the edit not a straight cut. Also in Scotland the editors cut 3 football matches on a single quad machine using this technique. On play 4 out the tape ran continuously even when we cut back to the studio for 5 links, which made studio presenting a hazardous activity. The link simply 6 had to fit the gap in the tape. 7 8 Lighting director: 9 It’s thanks to the policy of avoiding editing a 2” tape that so many early 10 programmes have been lost—they were recorded over! 11 12 Radio producer/presenter: 13 Exactly! I think if they cut the tape it had to be costed in the programme 14 budgets. 15 16

17 Fig. 13-2. Editing block © Ian Collins 18

19 We learn from this online conversation not only about the time consuming 20 and intricate disciplines of working with this piece of equipment, but about 21 its implications in terms of both the production process and viewing 22 experience. The explanation about expensive tape costs being passed on to 23 programmes only if they were edited gives us an insight into why so many 24 programmes were wiped rather than being archived. The participants draw 25 on their experiences in other production centres beyond BBC Pebble Mill, 26

Chapter Thirteen

250

widening the frames of reference, and giving the website relevance outside 1 of the geographical locality. The production process of recording and 2 editing today appears so simple and straightforward in comparison to this 3 era, and as someone who is used to operating semi-professional camcorders 4 today, an understanding of the technological history of programme making 5 has provided me with a new found respect for these craftsmen. 6

Many of the programmes produced at Pebble Mill were high volume, 7 low budget productions, often for BBC1 Daytime: programmes with 8 perceived low cultural value, which tend to be omitted from the major 9 online television databases, such as the British Film Institute (BFI) 10 database, and International Movie Database (IMDb). Such series can be 11 difficult to research, and therefore having an online community to refer to 12 can prove very effective. The BBC1 food quiz Eat Your Words (BBC 13 1996), is a case in point. I had a photograph of the set, from the production 14 designer, but knew no other details about the show. Through posting the 15 photograph on the website and linking it to the Facebook group, additional 16 information was offered. The researcher who had developed the idea and 17 devised the title added a comment, as did the show’s celebrity booker, 18 advising that Loyd Grossman was the presenter, as well as identifying the 19 two team captains, and providing the names of many of the celebrity 20 guests. This information certainly enriches the archive of series which 21 could otherwise be forgotten entirely, and demonstrates the potential of 22 online interactive archives in supplementing traditional institutional 23 archives. 24

When I began the Pebble Mill Project I had assumed that I would be 25 generating all the content. Former post-production staff had provided a lot 26 of photographic material for the site, but I assumed that the pages would 27 be fairly static once built. The associated Facebook group was initially 28 seen as an aside. Facebook, however, has become integral to the project, 29 and from the analysis of users it is clear that most traffic is directed via the 30 Facebook links to the website. What was even more surprising was that 31 the Facebook group grew and grew, and people began posting their own 32 material. With their permission I was then able to copy photographs and 33 comments and publish them again on the actual website, so that they are 34 preserved, and searchable. Instead, therefore, of having to rely on 35 information that I could source myself from interviews, or photographs in 36 my possession, the site became community generated. 37

The informality of Facebook, and the fact members can join and leave 38 the conversation at will, makes people comfortable in commenting on a 39 post in a way in which they seem more reticent to do on the website. This 40 leads to interesting stories coming to light, which would otherwise risk 41

Using Social Media to Build Hidden Screen Histories 251

being lost. The following anecdote was posted as a Facebook comment in 1 response to a photograph about a different Pebble Mill at One programme: 2

3 Assistant Floor Manager: 4 And then, of course, there was the ‘World War III’ PM (Pebble Mill at 5 One) from about 1981. My job was to cue in about 15 tanks and armoured 6 personnel vehicles at the beginning of the show. Unfortunately, the engines 7 were so loud that X’s (the director’s) ‘stand by to cue’ sounded like ‘and 8 cue’; with the wonderful outcome that the war was over even before a 9 bewildered and slightly smoky Bob Langley opened the show. I remember 10 X’s rage becoming audible over the departing army ... To be fair, the 11 centurion tanks didn’t help, but of course, absolutely, all X’s fault. I was so 12 annoyed, I even swapped my earpiece for a headset... 13 14

The story illustrates the unpredictability of live television, and the 15 repercussions of things going wrong on air, as well as the scale and 16 ambition of a daily daytime magazine show. This kind of incident is 17 unlikely to be recorded in the official BBC archive; there was probably no 18 incriminating paper trail. Even if the programme as broadcast still exists, 19 without the background knowledge the casual viewer would probably not 20 realise that what was seen on screen was not intended to happen that way. 21 The comment also demonstrates how one post can inspire another 22 different, yet related, one. 23

Through the interactivity of digital web technologies, the online 24 community has the ability to build a story collectively, with each 25 contributor adding a small piece to the jigsaw. An example of this took 26 place when I posted a comment about comedian Frank Carson’s funeral in 27 March 2012, mentioning that he had been a guest on Pebble Mill (BBC 28 1990—6), and had, I believed, attended the staff Christmas party. A 29 member of staff confirmed: 30

He came in through the double doors, saw an audience in party hats and 31 went for it. He was fabulous. It was a real treat. Took our mind off sprouts 32 that had been cooking since September. 33

An engineer then commented that he had a photograph of Carson at the 34 party, which I was able to add to the post (see Fig. 13-3). After this the 35 researcher who was looking after the comedian on the day added the 36 following: 37

When he arrived, he told me his flight back home to Blackpool wasn’t 38 until 6pm, so we had to find something for him to do, the Christmas lunch 39 was a Godsend. […] I love the earlier comments because since that day 40 I’ve felt slightly guilty at disrupting everyone’s lunch. He was a lovely 41

Chapter Thirteen

252

man, but I remember being glad to get him into the taxi and on his way to 1 the airport—exhausting! 2

The post became richer through the addition of each comment. It is hard to 3 imagine how this kind of incident could be effectively documented 4 without the collaborative nature of social media. That the comments 5 assuaged the guilt the researcher had felt from letting Carson loose at the 6 Christmas lunch was an added and totally unforeseen benefit. The 7 exchange also tells us a lot about the culture of the organisation – that 8 there was a Christmas lunch for all the staff, and that programme guests 9 might be included, demonstrates a closely knit, yet informal working 10 community. 11

Limitations of virtual archives 12

There are a number of challenges that unofficial community archives such 13 as the Pebble Mill Project are faced with. The site has no official status, 14 and I did not consult the BBC before I started it, although I did talk to 15 some former colleagues about the issues I might face. Some members of 16 BBC management are aware of the project and are supportive, for instance 17 the outgoing Head of Vision Productions Birmingham, and now Head of 18 Vision Productions Bristol, Nick Patten, has told me personally that he 19 enjoys the site. The project is clearly not commercial and remains below 20 the radar of much of the Corporation. 21 22

23 Figure 13-3. Frank Carson at a staff party. © Stuart Gandy 24

Using Social Media to Build Hidden Screen Histories 253

Intellectual Property 1

The question of intellectual property rights is an important and at times 2 complex one. The BBC, like other broadcasters, is protective of the 3 copyright of its programmes, despite its public service remit and its 4 attempts to make some of its archived programmes more widely accessible 5 online. This defensiveness is understandable given the BBC’s commercial 6 activities, through BBC Worldwide, such as DVD sales, and sales of 7 programmes abroad, as well as the complex rights considerations of its 8 archived programmes. From my experience of working as a producer at 9 the BBC, I know that during the Pebble Mill era many shows were 10 licensed for two UK and Eire terrestrial transmissions only, and anything 11 above that (including online) would require a renegotiation with rights 12 holders such as artists, directors, composers etc.; this would be unfeasible, 13 both logistically and (potentially) financially. There is no BBC video on 14 the http://pebblemill.org site; to breach the BBC’s rights in this manner 15 could invite unwelcome official attention, and possibly sanction. All video 16 material has been specially shot for the website and does not pose rights 17 issues. I am careful to add a copyright disclaimer on all posts, stating that, 18 “copyright resides with the original holder, no reproduction without 19 permission”. 20

Accuracy and authenticity 21

Other major considerations with an archive sourced from an online 22 community are questions of accuracy and authenticity. Frequently, little 23 verification is possible, and an individual’s memories may prove factually 24 unreliable. This was illustrated with a Facebook discussion over the 25 location of former BBC Birmingham studios in Broad Street. The writer of 26 a blog post said that he thought the building was still there, near the canal, 27 another person said that it had been demolished, and had been where a 28 hotel now stands, and a third person described it as being further up Broad 29 Street altogether. It was possible to check this information using other 30 sources, but for memories of specific programmes or working practices, 31 this is not necessarily the case, and therefore information in blogs or 32 online comments cannot be assumed to be entirely accurate. Whilst much 33 of this inaccuracy is unintentional there are also questions of deliberate 34 embellishment with incidents gaining greater impact in the re-telling than 35 they originally enjoyed. The fact that the online community is made up of 36 programme makers, people whose careers were often founded on their 37 ability to tell a good story, seeks to cast a question of doubt over the 38

Chapter Thirteen

254

veracity of some aspects of incidents re-told through website blogs or 1 comments. The following is an edited excerpt from a cameraman’s blog 2 about the occasion when a harrier jump jet appeared on the Pebble Mill at 3 One programme: 4

5 Ah, the Harrier. As you can see, it’s a bloody expensive way of getting 6

a bloke from Rutland to Pebble Mill. Now, when these guys say they’ll 7 land at 13:12 they land at 13:12. The director was screaming that they 8 were early but really he should have asked them what time they’ll get 9 close enough to be seen, which is obviously 4 or 5 minutes earlier. So, the 10 ensuing interview had to be cut short and we all legged it out the back. A 11 helpful squaddie from the advanced party suggested I keep a respectable 12 distance to prevent self-immolation. I’m so glad he told me because it 13 allowed me to pin several rounds of bread to my chest both as protection 14 and for a late breakfast. 15

What a racket this thing makes when it hovers and the down-draught is 16 incredible, much worse than a helicopter. However, because it’s a jet, it’s 17 the heat that gets you. The bread proved a winner, but he landed a little too 18 quickly for my liking. 19

Despite this thing costing hundreds of millions, I couldn’t believe it 20 when they used an extremely old wooden window cleaning ladder for his 21 dismount. Presumably, there’s a window cleaner in Rutland using a very 22 expensive set of steps to ply his trade. 23

Once in the grasp of mother earth, he was beckoned for the interview 24 with Marian Foster. If I remember rightly the answer to the first question 25 was, ‘10 years’, the second, ‘head for Leicester, straight down the M69, 26 right at the M6 and left at Spaghetti Junction’ and the third, ‘in time for 27 afternoon tea’. 28 29

The writer was a little annoyed when readers commented on small details 30 of the blog, such as questioning if the plane had actually come from 31 Rutland. In a subsequent message to me, he explained that they were 32 missing the point of the story, which he’d written to be amusing, as well as 33 informative. To him it did not matter if the plane had come from Rutland 34 or Somerset, he couldn’t actually remember Marian Foster’s questions, 35 and the window cleaner’s ladder and the toast were obviously pure 36 fabrication. This brings into question the purpose of material on the 37 website: should it always be objective and as accurate as possible, or is it 38 just as acceptable to tell an amusing story in the spirit of a particular 39 incident? The problem arises if the tone of a particular piece is not clear, 40 resulting in ambiguity for the reader. Across the website the tone of the 41 material is generally factual and objective, but blog posts, authored by 42 individuals, sometimes have a more humorous tone. 43

Using Social Media to Build Hidden Screen Histories 255

Allied to issues of accuracy and authenticity is the propensity of 1 individuals reflecting on incidents through the prism of ‘rose-tinted 2 spectacles’: remembering things as better than they actually were at the 3 time, although this is not always the case. We obviously remember the 4 past through the actuality of the present, and this colours our recollections, 5 and distorts the memory. The experience of particular incidents may 6 become heightened in the act of remembering, resulting in a greater 7 polarisation between positive and negative. Sometimes the posting of a 8 photograph on the website elicits a very strong response; this was the case 9 with a production still from the 1992 drama Witchcraft (BBC 1992). Here 10 are a couple of the comments: 11

12 First assistant director: 13 This show was a nightmare. As 1st AD I ended up being the go-between 14 between a ‘difficult’ director and the crew – many of whom used to be in 15 tears because of something the aforesaid director had said/implied. I went 16 prematurely grey and X (the designer) left show-business as a result! 17 18 Assistant editor: 19 I was assistant editor, working with Y (the editor). A bonkers production. 20 Z (the director) was hideously good at divide (and rule) and the best advice 21 we were given right at the start was to take notes of what he said so that 22 when someone else said, ‘Oh no, he said that’ we could point to our notes 23 and say ‘Oh no he didn’t’ and thus maintain unity […] We had a cutting 24 room bottle of brandy, which I’d hide so that Y couldn’t drink it all at 25 once. Great to have after some crazy viewing or other. It lasted right 26 through to final cut, I can remember the final toast. 27 28

Similar sentiments were offered by a number of people working on the 29 drama. There seemed to be a collective sense of wanting to discuss and 30 remember the problematic production, ameliorating the experience even 31 though it was twenty years on. Despite the negative experience, there are 32 touches of humour prevalent in these comments. The cutting room bottle 33 of brandy hints at what was, and was not, perceived as acceptable working 34 practice. Such a solace would be unlikely to be tolerated in today’s 35 workplace. 36

Negative comments on website posts have to be considered carefully, 37 and may require moderation, or removal, particularly if they are 38 defamatory, offensive, overtly political or risk infringing someone’s 39 privacy. There can be a tendency, particularly when commenting on 40 platforms like Facebook, to make unguarded or ill-judged remarks. On one 41 occasion photographs were posted on the website of a long running 42 popular drama series recorded at Pebble Mill. The make-up designer on 43

Chapter Thirteen

256

the series added information about the location recordings, remembering 1 how the lead actress, who was very well known, had sadly suffered a 2 miscarriage during filming, although this was not common knowledge at 3 the time. Fortunately she realised that this comment was inappropriate for 4 a public forum shortly after posting it, and deleted it, but it highlights the 5 dangers of failing to think through the implications of a particular 6 comment. 7

Whilst online and social media enjoy wide participation, many people, 8 and perhaps particularly older people, are reluctant to become involved 9 with it; research by Ofcom shows that adults over the age of 60 are less 10 likely to use the Internet than younger people (Ofcom 2009). BBC Pebble 11 Mill was operational from 1971-2004 and therefore many of the former 12 staff are an ageing population, and could be unwittingly self-excluded 13 from the project. The result is that particular viewpoints, artefacts or 14 information could be lost if the website and Facebook group are the only 15 ways of engaging with potentially interested individuals. Besides the 16 online activity there have been a number of offline events, such as 17 screenings, which have helped to bring other perspectives to the project. 18 Additionally, some former employees hold regular reunions, which could 19 prove another valuable source of contributions. Another potential 20 limitation of the archive being online is the reluctance of some former staff 21 members to share their photographs or memories. For some people this is 22 due to concerns over how materials might be used by third parties, whilst 23 others wish to keep their memories private, and whilst the archive might 24 well benefit from these people’s contributions, their views must obviously 25 be respected. 26

Fragility 27

The website and Facebook group are by their nature perhaps as ephemeral 28 as some of the television programmes that they document. Online digital 29 archives, whilst widening participation, should not be thought of as 30 necessarily synonymous with the long-term preservation of artefacts. They 31 are virtual rather than physical spaces, and therefore particularly 32 vulnerable. This was illustrated recently when the server that hosts the 33 Pebble Mill website crashed. The website was unavailable for a number of 34 hours, highlighting not only the intangibility of the online world, but also 35 the lack of control, and potential impingement by forces totally unrelated 36 to the project. The success of the project hinges on the contributions of the 37 Facebook group, and yet Facebook seems even more vulnerable and 38 impermanent than the actual website. Facebook comprises of global and 39

Using Social Media to Build Hidden Screen Histories 257

corporate-designed systems, where users’ contributions are rule-bound and 1 homogenised (Garde-Hansen 2009). Facebook claim intellectual property 2 rights over contributions, and can change the site in any way at any time; 3 users therefore have very little control. It is also impossible to search by 4 subject, therefore in order to provide this function, I copy the majority of 5 the Facebook comments and update the original website post with the new 6 information, explaining where it has come from. In this way the Facebook 7 conversations are preserved and searchable, on the website at least. 8

My Position 9

Both a benefit and a potential limitation of online, community archives, 10 such as the Pebble Mill Project, is the individual, or group of people who 11 run the site and post the content, who could be termed “citizen curators”. 12 The Pebble Mill Project would have been highly unlikely to flourish if it 13 had not been set up by a former member of staff. Although I do not 14 personally know, offline at least, many of the people who contribute to the 15 site, we are likely to have mutual contacts. This builds trust, and therefore 16 gives me access to information that would be very difficult for an outsider 17 to negotiate. There is a shared understanding of the production culture, 18 which can begin to add meaning to a seemingly dull artefact. This trust is 19 very important, and could be seen to be abused if, for example, I decided 20 to try and commercialise, or politicise the site. At present there is an 21 unspoken contract between myself and the contributors to the site, that the 22 purpose of the site is as stated: to document and celebrate the programme 23 making that went on at Pebble Mill. 24

When the website began I did not anticipate its popularity, nor the 25 implications or responsibilities of running it. It has become a community 26 archive, and therefore it needs to serve the needs of the community: 27 material should be structured in a logical way, categorised, and searchable, 28 so that it can be retrieved easily, as is the case with a more orthodox 29 archive. Material needs to be checked for factual accuracy, where possible, 30 and posts should not be offensive or defamatory. If posts are inaccurate or 31 substandard in some other way then this reflects on the quality of the site 32 and diminishes the esteem users hold it in. Additionally the copyright of 33 the artefacts on the site needs to be protected as much as is possible within 34 the scope of digital interactivity, and amidst the sometimes conflicting 35 desire to share information as freely as possible. 36

Running the website takes a considerable amount of time, and whilst I 37 find it very rewarding, I may not want to do it indefinitely; equally I would 38 not want the website to stagnate, or worse, to become defunct or 39

Chapter Thirteen

258

decommissioned. The long-term future of the website—and its 1 relationship with curators—therefore needs further consideration. 2

Conclusion 3

The Pebble Mill Project provides material which informs a historiography 4 of television production at BBC Pebble Mill, concentrating particularly on 5 exploring the relationship of evolving television production technology 6 with innovation in programme making. The website and Facebook group 7 have been a valuable resource for academics not directly involved in the 8 project; for example Rachel Moseley (2013), Ben Lamb (2012) and Paul 9 Long (2011) have all used the archive and community to further their 10 research. This impact is beyond the scope of the initial project, and hints at 11 the potential of online community archives to feed in to wider research 12 into television histories. 13

Despite its obvious limitations and challenges, social media does 14 provide television historians with a potential new tool in documenting 15 screen histories, particularly for those programmes or practices less likely 16 to be archived in any detail through traditional methods. We obviously 17 need to be mindful that the results may only provide us with a partial 18 picture, but perhaps one that is not easily accessed elsewhere, and one that 19 can be supplemented by resource to the institutional archives. The Pebble 20 Mill Project is perhaps a singular case, but it does illustrate the potential 21 for using social media in the research of television history, and could 22 provide a model for developing other projects along similar lines. 23

Bibliography 24

BBC. 1969. Broadcasting in the Seventies. London: British Broadcasting 25 Corporation. 26

Brandt, George ed. 1993. British Television Drama in the 1980s. 27 Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 28

Bonner, Frances. 2003. Ordinary Television. London: Sage Publications. 29 Cooke, Lez. 2005. “Regional British television drama in the 1960s and 30

1970s”. Journal of Media Practice 6:3: 145-155. 31 Douglas, Susan. 2010. “Writing From the Archive: Creating Your Own”. 32

The Communication Review, 13:1. 5-14 33 Ellison, Nicole, Charles Steinfield and Cliff Lampe. 2007. “The Benefits 34

of Facebook ‘Friends’: Social Capital and College Students’ Use of 35 Online Social Network Sites”. Journal of Computer-Mediated 36 Communication 12:4, article 1. Available at: 37

Using Social Media to Build Hidden Screen Histories 259

http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol12/issue4/ellison.html 1 Garde-Hansen, Joanne ed. 2009. Save as…Digital Memories. Basingstoke, 2

Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. 3 Johnson, Catherine. 2007. “Negotiating value and quality in television 4

historiography”. In Re-viewing Television History: Critical Issues in 5 Television Historiography, ed. Helen Wheatley, 55-66. London: I. B. 6 Tauris. 7

Lamb, Ben. 2012. “The Roses of Eyam: reassessing the theatrical legacy of 8 studio-shot television drama”. Conference: Theatre Plays on British 9 Television. University of Westminster, 19 October. 10

Leadbeater, Charles. 2008. We-think: Mass innovation, not mass 11 production: The Power of Mass Creativity. London: Profile Books 12

Long, Paul. 2011. “Representing Race and Place: Black Midlanders on 13 Television in the 1960s and 1970s”. Midland History, 36:2: 262–77. 14

Moseley, Rachel. 2013. “‘It’s a Wild Country. Wild … Passionate … 15 Strange": Poldark and the Place-image of Cornwall”, Visual Culture in 16 Britain, 14:2: 218-237. 17

O’Reilly, Tim. 2005. Design Patterns and Models for the Next Generation 18 of Software. [Online]. 19

http://www.oreillynet.com/oreilly/tim/news/2005/09/30/what-is-web-20 20.html. Accessed October 19, 2012. 21

Ofcom, 2009. Digital Lifestyles: Adults aged 60 and over. [Online]. 22 http://stakeholders.ofcom.org.uk/market-data-research/media-23

literacy/archive/medlitpub/medlitpubrss/digitallifestyles/ 24 Accessed February 22, 2013. 25

Putnam, Robert, D. and Lewis, M Feldstein. 2003. Better Together. New 26 York: Simon and Schuster. 27

Rolinson, Dave. 2005. Alan Clarke. Manchester: Manchester University 28 Press. 29

Spigel, Lynn. 2010. “‘Housing Television’: Architecture of the Archive”. 30 The Communication Review 13:1: 52-74. 31

Wheatley, Helen ed. 2007. Re-viewing Television History: Critical Issues 32 in Television Historiography. London: I. B. Tauris. 33

Related Documents