CHARLES DICKENS AND THE ETHICS OF ACCOUNTING Senior thesis written by Leslie Chang Thesis advisor: Professor Jacob Soll 4 December 2014

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

CHARLES DICKENS AND THE ETHICS OF ACCOUNTING

Senior thesis written by Leslie Chang

Thesis advisor: Professor Jacob Soll

4 December 2014

Chang 2

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter Page

Introduction 3

I. Creating a System of Accountability 6

II. Forgetting the System of Accountability 19

III. The Rendered System, or Neglecting the Soul 29

IV. The Systemic, or the Pains of the Masses 44

V. Accounting for the Soul 55

Acknowledgements 57

Bibliography 58

Chang 3

INTRODUCTION

This paper examines the role of accounting as an ethical framework by analyzing its

historical roots, tracing its development in England in concurrence with economic progress

through the Industrial Revolution and into the nineteenth century, and close-reading Charles

Dickens’ novels for the nineteenth century perception of accounting ethics. Aspiring merchants

sought accounting educations as early as the fifteenth century because of its practical uses in

running a business. But as the Industrial Revolution spurred great entrepreneurial ventures, once

venerable writing masters and accountants were met with regressing demand for their expertise;

fewer and fewer instructors taught their craft where accounting academies once prospered.1 The

education system that aided England’s transformation into a global, commercial, and leading

force gave way to the powerful and unregulated force of capitalism.2

Dickens is famous for his acute social commentary and archetypal characters, but he was

also a staunch critic of that unregulated force. While he denounced child labor and bureaucracy

as some of his more prominent recurring themes, he also stressed the importance of financial

accountability. By all means, accounting was not a foreign concept in eighteenth century

England, and yet the upheavals created by the Industrial Revolution compelled him to reevaluate

accounting as a framework for many social issues. Despite the rich and ethical culture of

accounting that existed in the philosophical and scholarly sphere in England during the

eighteenth century, Dickens’ inspiration came from his experience in a society that no longer

recognized its importance. He criticized the culture of accounting in nineteenth century Britain

1 John Richard Edwards, Writing masters and accountants in England – a study of occupation, status and ambition

in the early modern period, HAL Archives available at Journ´ees d’Histoire de la Comptabilit´e et du Management, <halshs-00465852>, p. 10. 2 John Richard Edwards, Teaching Merchants Accompts in Britain During the Early Modern Period, Cardiff Business

School Working Paper Series in Accounting and Finance A2009/2 (2009), p. 29; Chatfield, p. 51.

Chang 4

by creating idealized, fictional accountants who understand the importance of ethics,

accountability, and happiness in an increasingly numbers-oriented society. Juxtaposed with

actual accounting practices as they were rendered in nineteenth century Britain, Dickens’

protagonists, though metaphorical, point to a historical discourse of accounting.

In shaping many of his characters’ lives into metaphors for accounting, Dickens railed

against new perspectives and ideas that regarded England’s political economy. For modern day

readers of his novels, using earlier accounting practices as an ethical framework for his plots and

characters not only provides insight into the degraded culture of ethics in nineteenth century

England, but also bureaucratic management and accountability. Keeping in mind the range of his

many literary works, I focus on Little Dorrit and A Christmas Carol. These works vary both in

time of publication and popularity, as to better trace Dickens’ inclination toward accounting. Set

in the 1820s, as the story is narrated thirty years before its publication in 1857, Little Dorrit is set

around the same time that Dickens own father was imprisoned for debt and is closely associated

with the financial situation that his family experienced. On the other hand, A Christmas Carol is

so caricatured to clearly highlight the rights and wrongs of its characters and further the

association of accounting with ethics.

Dickens thus established two kinds of accountants in nineteenth century Britain: the one

who poorly manages himself and his business and perpetuates the system of inequity in England,

and the one who is born into the system and cannot break free. His views recall the historic

importance of accounting; equally important for individuals to learn bookkeeping methods was

having managers learned in the ways of accounting, so that they might be able to balance affairs

and create stability. This distinct separation parallels the understanding of accounting based on

its historical definitions—financial and moral—and illustrates the extent to which accounting

Chang 5

was rendered in society. Both Little Dorrit and Ebenezer Scrooge are well-versed in bookkeeping

and isolated in their respective societies because of their anachronistic tendencies. The

proliferation of economic theories ran concurrent to the decline of accounting education and the

culture of accountability in England, a detrimental shift that permeated all levels of society. The

actions that these characters take to reverse their isolation and live out a well-balanced life was

Dickens’ way of suggesting an alternative to the understanding of accounting as it was in

eighteenth century Britain. Little Dorrit is the epitome of an ethical accountant, while Scrooge

must take pains to reconnect with his sense of morality. Dickens’ imaginative characters and

cautionary tales were inspired by his personal experience as well as the specific culture of

accounting that existed in nineteenth century England. By commenting on his perception of

accounting as it was rendered in society, Dickens became part of a wider English tradition of

using accounting to look at ethics.

Chang 6

I

CREATING A SYSTEM OF ACCOUNTABILITY

The cultural, philosophical, and political aspects of accounting as a nineteenth century

social phenomenon were unique to the development of British industrial processes. Prior to the

Industrial Revolution, however, accounting was developed and adopted in a linear fashion.

Seventeenth century views of accounting in England had not deviated since the origins of

double-entry accounting in fifteenth century Italy. In 1664, Thomas Mun, a British mercantilist

and writer on economics, noted that “a perfect Merchant… ought to be a good Penman, a good

Arithmetician, and a good Accountant, by that noble order of Debtor and Creditor.”3 Accounting

remained inexplicably tied to good business practices, and consequently ethics and management,

up until the turn of the eighteenth century, carried out even by economic theorists in using

accounting as a way of describing ethics.

Accounting today, however, has a quantitative connotation; it is a practice largely

understood for recording and reporting business transactions. But its history and origins reveal a

more qualitative side to accounting. In addition to its business functions, the semantics of

accounting points to an ethical awareness of money and management. The root word, account, as

a noun, can be used to describe calculations, records, or statements. As a verb, account means to

explain, to include, or to consider. This last definition—to consider—lends itself to the words

accountable and accountability, the idea of being responsible for personal actions and its effects

on others. This moral sentiment qualifies the rigidity of pure financial accounting and brings

balance to a profession that is otherwise seen as severe and removed. This disassociation of

accounting and ethics pre-dates the modern understanding of accounting, a divide that extends

3 Thomas Mun, England's Treasure By Forraign Trade (London: 1664), accessed at The John Carter Brown Library.

Chang 7

beyond semantics and had detrimental effects on society, most notably mirrored by Dickens in

his novels during the nineteenth century.

Accounting allowed merchants to keep track of their business dealings. An Italian

merchant once kept books for his own practices to have a better understanding of the flow of

money coming in and out of his business. But as the trade of eastern products stimulated demand

for the production of European exchange goods, placing geographically-strategic Italy at the

forefront of trading hubs, the ever-expansive trade routes no longer supported bookkeeping

methods used by small companies for single point transactions. Merchants were beginning to

trade through networks and form partnerships with traders and businesses from various

countries. As a result, unsystematic records caused so much disorder that owners were at risk of

losing control of distant operations.4 In order to remain financially solvent, traders needed a

sophisticated form of record keeping. This transition from single-entry accounts to double-entry

bookkeeping is largely acknowledged as a turning point in accounting history. Double-entry

accounting became widely practiced after Lucas Pacioli published his Summa de Arithmetica,

Geometrica, Proportioni et Proportionalita (Everything about Arithmetic, Geometry, and

Proportion) in 1494. Pacioli is often considered the father of accounting, not because he invented

double-entry bookkeeping, which he did not, but because he was instrumental in the proliferation

of accounting methodology as it was used in Italy at the time. There were five topics in his book:

algebra and arithmetic, their use in business, bookkeeping, money and exchange, and pure and

applied geometry. Bookkeeping, which was the third section in the Summa, was called De

4 Michael Chatfield, A History of Accounting Thought (Hinsdale: The Dryden Press, 1974), p. 33.

Chang 8

Computis et Scripturis (Of Reckonings and Writings) and had thirty-six chapters that were meant

to “give the trader without delay information as to his assets and liabilities.”5

Pacioli’s breadth and depth of subjects reveal a critical condition of being a merchant. A

good merchant was a well-rounded merchant, practiced in all crafts; accounting was not limited

to a profession. Contrary to its social standing in nineteenth-century England, accounting was an

integral and widely-accepted part of the business world. Its applications in bookkeeping were

key components of a merchant education because it made for good, honest business people.

Rather than a vehicle for profitability, its primary objective was to ensure the ethical

responsibility of individuals or firms managing the exchange of goods and services. When

mercantilism expanded and the world evolved to embrace globalization and budding empires,

accounting grew to encompass economies, trade routes, and even societies—it became a form of

management beyond personal managing purposes.

Accounting grew from an individual education to a social phenomenon that facilitated

efficient and ethical cities. Pacioli describes cities in his manual that employed accounting into

its systems as examples of proper ways to control and conduct market activity. The City of

Perosa employed a consul with mercantile officers that verified all account books merchants

brought in.6 Ideally, the officers would be made aware of everything—from who might be

entering entries, so as to differentiate between different handwriting, to what currency the

transactions were completed in—so that they could verify all the information presented in the

account books. After inspection, each book would be stamped and signed with the officer’s name

and taken back to shop, where the merchants would use these books, verified and approved by

5 J. B. Geijsbeek, Ancient Double Entry Bookkeeping: Lucas Pacioli’s Treatise (Denver: University of Colorado, 1914),

p. 32. 6 Geijsbeek, p. 41.

Chang 9

the city, to conduct business. This auditing service was part of the city’s jurisdiction, indicating

that it valued accountability and did what it could to ensure reasonable integrity within its

markets. Beyond personal finance purposes, the city used accounting practices to be accountable

for its citizens. This same application of accounting, as a form of governmental control, was

utilized by Simon Stevin in Holland during the early seventeenth century.

While Pacioli championed bookkeeping as pertinent to running a business, Stevin

extrapolated his teachings and emphasized accounting’s integral nature in running a more

effective government. A tutor and adviser to Prince Maurits of Orange, he published

Hyponmemata Mathematica (Mathematical Traditions) in 1605, an encyclopedia of

mathematics, mechanics, and astronomy, the accounting portion of which, “Account-Keeping for

Princes, according to the Italian Method,” was greatly influenced by Pacioli’s work. Stevin’s

contributions to accounting greatly influenced the adoption of double-entry accounting in

Holland and the Low Countries. By the time double-entry bookkeeping methods became widely

adopted in England, around the seventeenth century, the British likewise understood the many

applications of accounting and championed an accounting education as critical for preparing the

youth to become good merchants in the developing merchant state. This time period coincided

with the gradual industrial processes that would eventually lead to the Industrial Revolution in

England.

The unprecedented and unparalleled development of England during the eighteenth and

nineteenth centuries marked a turning point in British history. Not only did England quickly

become a dominant world power, but it also became the leading nation for teaching double-entry

accounting and boasted a powerful group of accounting teachers and practitioners. The

concurrent growth of both merchant practices and accounting literacy is not surprising, given the

Chang 10

inherent nature of accounting as a merchant craft. Contrary to the culture of accounting in

England during the nineteenth century, the rise of England as a dominant world economy during

the seventeenth- and eighteenth-centuries greatly increased the demand for writing masters and

accountants, a dual designation for instructors of “writing, arithmetic, and merchant accompts,”

qualities necessary for youths interested in pursuing commercial careers.7 This occupational title

signifies the importance of writing and bookkeeping skills during early modern England and was

equated to skills successful merchants needed. Counting houses in England facilitated the

movement of goods, money, and information, and merchants needed to be well-versed in writing

for drafting correspondences as well as bookkeeping.8 Just as Pacioli taught various subjects,

writing masters and accountants were experts on various crafts and taught all subjects to numbers

of students. The connection between accounting and business was so interwoven that schools run

by writing masters and accountants were believed to further and promote national interest.

London became the center of “pre-workplace education” for merchants and tradesmen. Edward

Cocker, a famous writing master and accountant who taught in London during the late

seventeenth-century said that “No Arts or Sciences tend more to the advancement of Trade, and

the honour of a Nation than faire Writing & Arithmetick, and Excellency in them renders a man

an Instrument of his owne and his Countreyes happinesse.”9 This view was maintained through

to the first half of the eighteenth century; George Bickham, in his writing manual published in

London in 1743, The united pen-men for forming the man of business: or, The young- man's

copy-book; containing various examples necessary in trade and merchandize, stressed the

7 Edwards, Writing masters and accountants in England, p. 9; Accompt / accomptant is an antiquated version of

account / accountant. 8 Kim Nusco, Mind Your Business, The John Carter Brown Library, Brown University,

http://www.brown.edu/Facilities/John_Carter_Brown_Library/business/index.html. 9 Edwards, Writing masters and accountants in England, p. 12.

Chang 11

importance of the writing master and accountant’s craft as critical to developing England’s

wealth:

“To the Merchants, and Tradesmen of Great-Britain. . . Writing and Accounts, no

Less than Trade & Commerce, are become the Glory of Great Britain.—And as,

by Your extensive Trading, and frequent Use of the Pen, You have increas’d the

Wealth of each particular City, and made this Island distinguish’d and honour’d

in all the known Parts of the World.”10

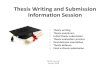

Figure One: A reproduction of George Bickham’s writing manual as it was published in 1743.

Source: The John Carter Brown Library

Instruction manuals played a major role in standardizing accounting practice in England,

and the proliferation of instruction manuals “attests to the need for employees who were literate,

numerated, and trained in the methods of bookkeeping.”11

Writing masters and accountants

10

George Bickham, The united pen-men for forming the man of business: or, The young- man's copy-book; containing various examples necessary in trade and merchandize (London: 1743), accessed at The John Carter Brown Library. 11

Kim Nusco, Mind Your Business, The John Carter Brown Library, Brown University, http://www.brown.edu/Facilities/John_Carter_Brown_Library/business/index.html.

Chang 12

promoted their craft by publishing copy-books, instructional manuals to help aid youths learning

the proper skills needed to be good merchants. These copy books allowed space for students to

practice their penmanship directly on the sheets and were widely published and distributed in

London and even more so in the countryside, where instructors were more difficult to come by

and students needed ways to educate themselves. The first English manual on bookkeeping, A

Profitable Treatyce, was written in 1543 by Hugh Oldcastle, and then reprinted in 1588 by John

Mellis in A Breife Instruction, etc.12

Mellis is the earliest known figure to hold the titles of

writing master and accountant; the preface to one of his works, published in 1594, states that he

had been “teaching writing, arithmetic and drawing for twenty-eight years.”13

After Mellis, there

is a gap in the profession of writing masters and accountants until the second half of the

seventeenth-century, when eleven professionals started to flourish in England and the craft

became more popularized. By the end of the century over sixty writing masters and accountants

were teaching in or around London.14

Copy-books, as well, appeared infrequently before 1600,

but by 1800 over one hundred publications with multiple editions were circulating in England.15

But by the time Dickens was born, in 1812, the popular pursuit of an accounting

education was nowhere to be found. His father’s imprisonment for debt suggests that the decline

in demand started much earlier than the turn of the century. Indeed, as Great Britain adapted to

accommodate new industrial processes and establish itself as a burgeoning merchant nation, the

accounting education that good merchants needed in order to be successful slowly tapered off,

even as markets became more accessible. While the publications were circulating in England,

12

Chatfield, p. 36. 13

Ambrose Heal, The English writing-masters and their copy-books, 1570-1800: A Biographical dictionary & bibliography (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1931), p. 75. 14

Edwards, Writing masters and accountants in England, p. 10. 15

Chatfield, p. 57.

Chang 13

however, copy-books remained constantly published only until the mid-eighteenth-century.16

Although accounting remains relevant in modern times as a profession, the importance of good

penmanship and writing as critical to accounting is a lost connection. The term writing master

and accountant developed because penmanship and bookkeeping were viewed as equally

important skills that merchants needed to be successful. Writing as an art form rose from “its

Serviceableness in the negotiating and managing important Affairs throughout the habitable

World, especially in all civiliz’d Nations, where Traffick, Trade, or Commerce, relating to the

Profit, Pleasure, or Well-being of human Societies, take place,” a statement that prefaced John

Hill’s best-selling manual in 1687. 17

But the increasing reliance on legible and prudent

handwriting for running businesses slowly shifted the focus away from the beautiful penmanship

and calligraphy that writing masters practiced, a practice that was historically taught alongside

bookkeeping. Out of the 121 writing masters and accountants that Ambrose Heal identifies

throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, only two were practicing during the late

eighteenth-century and Heal provides no information on writing masters and accountants that

flourished during the nineteenth century. As such, as the demand for calligraphy waned, so the

importance of accounting was viewed as less important if it was so tied to an arcane craft. The

disappearance of a joint jurisdiction over writing and bookkeeping implies that the value of such

an education was no longer valued, despite England’s rapid development as a merchant nation.

The writing master and accountant “disappeared from the commercial scene with the

term public accountant then developed to identify the practitioner with professional aspirations,”

shifting the importance of writing and bookkeeping from something to learn to simply something

16

Edwards, Writing masters and accountants in England, p. 10. 17

Eve Tavor Bannet, Empire of Letters: Letter Manuals and Transatlantic Correspondence, 1680-1820 (Cambridge University Press, 2009), p. 3.

Chang 14

“to do”.18

Bookkeeping was never taught as a singular subject and had little ground in society

with the disappearance of writing masters. This distinction critically undermined the importance

of an accounting education. Accounting as a professional career, independent from good

business practices, suggested that it was not necessary to learn accounting, so long as there were

accountants that were able to keep their books or audit public companies. This sentiment was

evidenced in the daily lives of merchants during the early years of industrialization: Sidney

Pollard writes that entrepreneurs during the Industrial Revolution had few staff members when

they first started their operations; as such, “many outside services now taken for granted or dealt

with by the single action of paying taxes, had to be provided by the large manufacturer himself,”

implying that the ‘outside services’ were a burden to the manufacturer, rather than integral to

effective management of his operations.19

Relegating accounting to professionals suggests that a

merchant no longer needed to have such control over his business dealings.

The demise of the writing master and accountant not only indicates a loss in education,

but also the connection between mismanagement and ruin. Copy books served as educational

tools, but “in addition to writing, spelling, arithmetic, and keeping accounts, manuals for training

clerks and other businessmen attempted to impart the values and behaviors deemed important for

the operation of the economy: accuracy, honesty, and trustworthiness.”20

In Nicholas Brown’s

manual, published in 1743, he explicitly cites the importance of maintaining integrity in his craft:

“art is perfect by Practice; Beauty without Virtue is like a painted Sepulcher… Misery attends

18

Edwards, Writing masters and accountants in England, p. 17. 19

Sidney Pollard, The Genesis of Modern Management: A Study of the Industrial Revolution in Great Britain (London: Edward Arnold, 1965), p. 198. 20

Kim Nusco, Mind Your Business, The John Carter Brown Library, Brown University, http://www.brown.edu/Facilities/John_Carter_Brown_Library/business/index.html.

Chang 15

Debts and Law suits.”21

Bickham, as well, combined his skill with instruction in crafting

cautionary notes in his manuals:

Figure Two: Cautionary notes in George Bickham’s manual

Source: The John Carter Brown Family

These warnings, while understood and stressed while the writing master and accountant

was still well employed, were slowly forgotten or cast aside by a society that turned its focus to

accumulating wealth. Accounting, once deemed integral to successful merchants as well as

governments—as Pacioli, Stevin, and even British writers championed—slowly became a craft

that was practiced by select individuals rather than widely taught. This education imbalance

stands in stark contrast to the rise of England as a capitalist, trading nation and its ramifications

directly affected the working classes. Without its historic applications to personal finances and

even efficient city management, both the practices of members of the working classes and the

implications of poor financial judgment made by upper management wrought society from the

top-down and bottom-up.

As a result, while Industrial Revolution powered ahead, increasing and promoting

improved standards of living and wages for a select group of people, societal constraints such as

working conditions debilitated the poor and trapped them in the cycle of urban poverty. Low

wages exacerbated the need to find and maintain a career, as unbearable as it might have been.

Although criticisms of this new era—which included but were not limited to factory conditions

21

Nicholas Brown, Handwriting Practice Book (London: 1743), accessed at The John Carter Brown Library.

Chang 16

and child labor—were prevalent prior to the advent of new manufacturing systems, rapid

globalization coupled with increased literacy rates prompted many more people to document and

comment on England’s shifting political economy.22

Indeed, Dickens’ rich social commentary

was supplied by the injustices that he, as well as members of the working classes, experienced in

light of the changing world order. His personal experience as an adolescent growing up during

the first half of the nineteenth-century greatly influenced his opinions about money, capitalism,

and government. Due to his father’s imprisonment, Dickens was sent to work at a shoeblacking

factory at the young age of twelve, a common experience for young children in England at the

time. Young as he was, it was during this time when Dickens began to shape his views on child

labor, isolation, and debt, views that would be reinforced as he grew up.

Paradoxically, Adam Smith, one of the most closely linked figures to capitalism, believed

in the necessity of accountability in society. Smith promoted the idea of laissez-faire in The

Wealth of Nations. Government should not be involved in business. Rather, putting the power of

choice into the hands of individuals and consumers would allow unparalleled progress in the

growing economy, as individuals acting for their own profit would unintentionally promote

societal interest: “The study of his own advantage, naturally, or rather necessarily, leads him to

prefer that employment which is most advantageous to the society.”23

In addition to bolstering

the economy, taking power away from the government would, in theory, reduce corruption at

high levels. Smith had a low opinion of government and believed that “in many governments the

candidates for highest stations are above the law; and, if they can attain the object of their

22

The Poor Law and Charity: An Overview, London Lives 1690 to 1800 (2012), http://www.londonlives.org/static/ThePoor.jsp#toc2. 23

Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations-A New Edition (London: G. Walker, J. Akerman, E. Edwards [et. al], 1822), at p. 178.

Chang 17

ambition, have no fear of being called to account for the means by which they acquired it.”24

The

lack of accountability in public life created an environment in which Smith believed

governmental officials were not accountable for their decisions and actions. Taking away the

opportunity for government to collude with businesses for profitability purposes would hedge

against corruption, both from the governmental level as well as from low levels of society, for he

saw the evils in conflating wealth with power or social status: “The corruption of our moral

sentiments that comes from this disposition to admire the rich and the great, and to despise or

neglect the downtrodden and poor”—a disposition that is echoed in Dickens work as individuals

struggle to determine what brings them happiness.25

The lack of government intervention meant

a greater need for individuals to possess a strong ethical and moral sense of control in order for

their pursuit of wealth to yield a system that benefitted those who were part of it:

“Concern for our own happiness recommends to us the virtue of (1) prudence;

concern for the happiness of other people recommends to us the virtues of (2)

justice, which restrains us from harming their happiness, and (3) beneficence,

which prompts us to promote it.”26

Smith emphasizes the importance of finding individual happiness as well as creating

happiness, a duality that seems to contrast the ideas of unregulated and unparalleled growth by

individual efforts. This belief is further reinforced by his ideals of individual accountability:

“A moral being is an accountable being. An accountable being, as the word

expresses, is a being that must give an account of its actions to some other, and

that consequently must regulate them according to the good-liking of this other.

Man is accountable to God and his fellow creatures.”27

Accountability then, means not only ensuring financial soundness, but also ensuring personal and

societal happiness in light of the pursuit of wealth. Accounting for intangibles such as happiness

24

Adam Smith, Moral Sentiments, p. 58. 25

Id. 26

Smith, Moral Sentiments, p. 263. 27

Smith, Moral Sentiments, p. 130.

Chang 18

is just as important as accounting for profitability. Only the idea of deregulation, however,

seemed to resonate with the public, and even today Smith is only associated with the idea of the

invisible hand guiding the economy, rather than the importance of ethical and financial

accountability.

Despite waning interest from the general populous, the culture of ethical accounting was

preserved by the highly educated. Even figures such as Adam Smith, famous for his

contributions to economics, incorporated accounting principles to his understanding of society

and the economy and the literature they produced. Smith held a deep understanding of the culture

of ethics surrounding accounting, as well as the double-entry philosophy of balance. His

contributions coincided with a burgeoning capitalist fever that introduced the idea of individuals

and private entities making profit, an idea that permeated all levels of European society and

fundamentally shifted the way people approached business and doing business.28

Smith,

however, never became associated with accounting or even ethics; only the theories that spurred

profit and productivity persisted. The reality of capitalism was such that it required individuals to

possess a strong sense of morals pertaining to business and money, characteristics that a good

accounting education would have taught. Dickens’ novels reveal that England developed

markedly different from the theorists’ original intentions because of this education imbalance. As

such, although capitalism and utilitarianism are purported to benefit the masses, a great wealth

and class disparity developed and persisted, leading nineteenth-century observers, in light of

rampant bureaucratic corruption and abuse of wealth and power, to question capitalism’s worth

and turn to alternative ways to view society.

28

Chatfield, p. 51.

Chang 19

II

FORGETTING THE SYSTEM OF ACCOUNTABILITY

While the philosophical debate around accounting continued, the reality of England’s

financial quandary highlighted the lack of ethical accounting methodology in the political sphere.

Despite England’s leading prowess in the previous centuries, double-entry accounting was

nowhere to be found in the British government, a government that idly watched its economy,

coupled with accounting literary, grow exponentially.

The irony and urgency of the situation was not missed. The latter years of the eighteenth

century saw the ramifications of the American War of Independence , which manifested in a vast

social disparity and created a financial storm, pushing many members of Parliament to call for an

accounting reform.29

Indeed, although the well-documented and pervasive social illness did not

immediately affect Parliament, applying double-entry accounting methods to the state’s books

could mitigate England’s increasing debt, which reached £250 million in 1784.30

Compelled to

action, Parliament ushered in “a movement which was . . . to introduce into public life a new

morality, into finance a new probity and into government as a whole new standards of efficiency

and economy.”31

This movement was centered around the ethical qualities of accounting that

were championed by esteemed economists, qualities that failed to carry over to the government.

More than ameliorating England’s fiscal disaster, an accounting reform could dissolve the

corruption that many people saw in Parliament.32

The mass cohort of accounting illiterate

government officials presented many opportunities for bureaucratic favoring and fraud. Although

29

Jacob Soll, The Reckoning (New York: Basic Books, 2014), p. 127. 30

Id. 31

Helen Roseveare, The Treasury: The Evolution of a British Institution (London: Allen Lane, 1969), p. 118. 32

Soll, p. 166.

Chang 20

accounting was no longer as prevalent in society, members of Parliament strived to reintroduce

the rich culture of accounting and its ethical implications.

Parliament wasted no time in beginning the reform. Starting in 1785, members of the

Commission of Accounts were appointed to “examine, take, and state the Public Accounts of the

Kingdom; and to report what balances are in the hands of Accountants which may be applied to

the public service; and what Defects there are in the present Mode of receiving, collecting,

issuing and accounting for public Money.”33

This was the first time England’s accounts were

thoroughly examined for release, despite the prevalence of accounting earlier in the century. The

Commissioners aimed to create a transparent, budgetary report that would be audited and

checked by different examiners “before an official statement was sent to the Lords of Treasury,

who helped make the most important national economic decisions.”34

Already, the system

employed by the administration mirrored the system of administrative auditing that the City of

Perosa employed, one that was thorough, administered, and audited by branches of the

government. Although the commissioners’ reports revealed the primitive methods of accounting

keeping and the extent of corrupt in British government finances, they offered a methodology for

reform grounded in the ideas of double-entry accounting: “Simplicity, Uniformity, and

Perspicuity, are Qualities of Excellence in every Account, both Public and Private; and Accounts

of Public Money, as they concern all, should be intelligible to all.”35

The language the

commissioners used suggests the absence of such existing bookkeeping methods and

demonstrates the bizarre financial situation that Britain was in: The industrious empire, home to

33

John Richard Edwards & Hugh T. Greener, Introducing ‘mercantile’ bookkeeping into British central government, 1828–1844, Accounting and Business Research, 33:1 (2003), p. 52. 34

Soll, p. 166. 35

Emmeline W. Cohen, The Growth of the British Civil Service 1780-1939 (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1941), p. 37; Edwards, Mercantile Bookkeeping, p. 52.

Chang 21

writing masters and accountants and their academies, was not balancing their books. Double

entry accounting was new to the government and reform was a long, overdue process.

By 1819, however, despite calls for better administrative proceedings, Britain was £844.3

million in debt and the public sphere became involved.36

That same year, over 60,000 people in

Manchester protested raised food prices and rigged elections, only to be met with military force

that not only injured but killed citizens.37

The British government was not only ineffective, but

losing support and faith. Repeated calls for applying double entry accounting principles to the

present system was thwarted by concern, objections, and differing ideas of application.38

Not

only was double entry accounting was unfamiliar to governmental officials in this time and

place, but there were also conflicting views of how much reform was needed. When the Board of

Treasury appointed a group of accountants and commissioners in 1828 “to consider how far it

may appear to be practicable and advantageous to employ the mercantile system of Double Entry

in the keeping of the Public Accounts,” bureaucratic opposition once again delayed the reform.39

Only when Whig Prime Minister Earl Grey came to power during the 1830s did England’s

accounting reform truly begin.40

Forty decades after the Commission of Accounts summarized

their recommendation for double-entry bookkeeping, the British government was slowly

reorganizing itself to parallel the industriousness of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Dickens, born in 1812, was caught in the variability of England’s economy and Parliament’s

vacillating tendencies. Well-aware of the inadequate accounting practices in his life, as well as

36

Edwards, Mercantile Bookkeeping, p. 52. 37

Soll, p. 166. 38

Edwards, Mercantile Bookkeeping, p. 55. 39

British Parliamentary Papers 1829, vi, Appendix No. I. 40

Soll, p. 166.

Chang 22

how society perceived its importance, he crafted tales of personal and financial reform based on

the ethics of accounting for more than numbers.

While the government was struggling to learn bookkeeping, however, accounting

principles continued to influence the social sphere. England’s inability to shape itself based on

the ethical model of accounting was conversely reflected in the development and popularity of

friendly societies. These organizations were voluntarily formed by groups of people who pooled

money together to hedge against incurring debt due to unforeseen circumstances such as

illnesses, or supporting families whose patriarchs have passed away.41

Although they were

prevalent during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, presumably developed in line with the

Industrial Revolution and foreign, urbanizing forces, friendly societies were most active during

the nineteenth century.42

Members of the societies even attempted to quantify their contributions

relative to different levels of risk, creating a unique, combined approach to financial and moral

accountability. Friendly societies represented not only mutual aid, obligation, and community,

but a cycle of exchange, and thus accountability, in a society that increasingly counted and

measured even human productivity and worth.43

Mutual dependency and this cycle of exchange

created a moral bond between different people and helped communities realize the importance of

being accountable for one another. This model, although seemingly contradictory to capitalism

and the pursuit of individual wealth, seamlessly represents both Smith’s views from Wealth of

Nations as well as The Theory of Moral Sentiments. The pursuit of individual wealth would, in

turn, benefit the community based on the cycle of exchange and accountability.

41

Friendly Society, Encyclopædia Britannica, http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/220217/friendly-society. 42

Id. 43

Daniel Weinbren, The Good Samaritan, friendly societies and the gift economy, Social History, 31:3 (2006), pp. 321.

Chang 23

Tenets of the evils of capitalism also continued to percolate through society. One of the

most recurring themes in Dickens’ novels is that of the workhouse, introduced into British

society by the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834. That the same government struggling with its

finances would give jurisdiction to friendly societies and pass welfare amendments, all of which

had vastly different missions and end goals, speaks to the capricious nature of nineteenth century

England. More commonly known as the New Poor Law, this amendment revised the British

welfare system by taking the burden of caring for the destitute off taxpayers, funneling, instead,

support into special workhouses, which became the only place the poor could go for relief.

Workhouses operated like small communities, providing sustenance, lodging, work, care,

clothing, schooling, as well as all the facilities or stores that might be present in a town. These

institutions operated on the idea of helping the poor help themselves and break out of their

poverty by working for their food and lodging, rather than relying on a welfare system to live,

thereby reducing idle folk in the streets.

Although workhouses were benevolent in theory, the assistance to the poor was

undoubtedly lacking. In order to prevent able-bodied poor from becoming dependent on the

system, its conditions were deliberately harsh. All members were ordered to wear uniforms and

even within the workhouse were different levels of poverty.44

Workhouses were often equated to

factories or prisons for the poor, both in the standardization of treatment and dealing with

poverty and in the draconian regulations that dictated life inside a workhouse. Members of the

workhouse and even the common people of England were “subjected to set of grating,

inconvenient, and tyrannical laws, totally inconsistent with the genuine spirit of the constitution”

44

Parliamentary Papers, 1842, XIX, pp.42-43.

Chang 24

so that the workhouse could persist.45

It was the worst manifestation of friendly societies,

wrought so because it lacked the idea of accountability and moral responsibility.

The New Poor Law also reflected tenets of utilitarianism, a theory partially developed by

Jeremy Bentham that suggested success can be measured by the greatest good for the greatest

number of people. Bentham’s Panopticon, a thought experiment about the ideal prison, focused

on the way to force prisoners to self-regulate and thus decrease the need for a large number of

guards. In addition, the Panopticon held the idea that the level of comfort the prisoners

experienced would be that experienced by the lowest level of society. The goals for the

workhouse were similar to Bentham’s goals for the Panopticon: “Morals reformed—health

preserved—industry invigorated—instruction diffused—public burthens lightened—Economy

seated, as it were, upon a rock—the Gordian knot of the poor law not cut, but untied—all by a

simple idea in Architecture!”46

Utilitarianism delineates that the greatest happiness principle

entails securing everyone from starvation and fear of want. But the government ran the

workhouse the same way Bentham expected his Panopticon to function; people feared

workhouses and its existence relied on those living on the lowest rungs of society to self-

regulate, lest they become dependent on the workhouse. The workhouse served as a central

authority for regulating the number of people who were poor. The fewer people who sought

relief, the greater success the government would have on maintaining the poverty rate. The

wretched conditions that were offered, however, turned the idea of relief into a deterrent, so that

many people avoided the workhouse not from necessity, but choice. This misconception assumed

that poverty was not a structural ramification, but rather a self-inflicted one. The workhouse

45

David Englander, Poverty and Poor Law Reform in Nineteenth-Century Britain, 1834-1914: From Chadwick to Booth (Harlow: Addison Wesley Longman: 1998), p. 93. 46

Jeremy Bentham, Panopticon (Dublin: Thomas Byrne, 1791), p. 2.

Chang 25

expected to free society from poverty. Instead, it exacerbated the situation. Both the Panopticon

and the workhouse profited off fear as the primary motivator of self-regulation. Both were

economical, but neither allowed room for human dignity. While the Panopticon never came to

fruition, the workhouse was created into a system that was impossible for the poor to escape.

Even in developing utilitarianism, however, Bentham returned to accounting ideas to

further his theories. His view of double-entry accounting shifted dramatically from the late

eighteenth century to the mid-1830s, a change that was brought about by the government’s

ineffective financial management and points toward the extent to which the public was exposed

to the government’s mishaps. Bentham offered his scathing view of double-entry accounting in

Pauper Management Improved (1797): “Would public accounts be rendered the clearer, by

translating them into a language composed entirely of fictions, and understood by nobody but the

higher class of merchants and their clerks?”47

Bentham believed that the technicalities of double-

entry accounting as proffered by Pacioli was not intelligible for all of society, creating instead an

accounting technique that “emphasised uniformity and comparability by utilising an

unambiguous nomenclature and the tabular format.”48

His method for calculating the greatest

happiness principle and determining ‘utility’ entailed “[summing] up all the values of all the

pleasures on one side, and those of all the pains on the other.”49

Like Smith, Bentham understood

accounting’s applications beyond monetary valuation. His idea of utility encompassed abstract

emotions as well as tangible rewards, unifying these different qualities in life and giving them

weight and extension on a balance sheet.

47

Jeremy Bentham, ed. John Bowring, The Works of Jeremy Bentham (Edinburgh: William Tait, 1841), p. 393. 48

Edwards, Mercantile Bookkeeping, p. 54. 49

Jeremy Bentham, An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (Kitchener: Batoche Books, 2000), p. 32.

Chang 26

The importance of applying double-entry accounting to the failed British government,

however, was not lost. In 1831, Bentham uncharacteristically wrote about the necessity of

bookkeeping and government accounts: “From the giving employment to the system of Double

Entry, in the accounts of its subordinate functionaries, Government has every[thing] to gain,

nothing to lose.”50

The cries of corruption against Parliament continued to tear society apart and,

thirty years after the Commission of Accounts first gave their reports on fiscal reform, England

still could not balance its books, and had to look toward France and Holland for help.51

Although

Dickens argues against the workhouse for diminishing the value of a human life in attempting to

provide for as many people as possible, Bentham similarly moved “beyond profit-oriented

accounting” and recognized that everything could and should be valued and properly managed in

order to create a more equitable society.52

These conditions allowed Dickens to indict his times in his novels, using the moral

grounds set in place by an earlier discourse of economics as well as the reality of its importance

as reflected in England’s finances. Dickens was by no means against capitalism and all its

benefits, but he clearly understood the dangers of pursuing a path of wealth and forgetting the

importance of accountability. Three centuries after the father of accounting published his

manual, Dickens created narrative arcs that embodied Pacioli’s idea of “duality, integrating

tendencies, and balancing features underlying double entry procedure” by highlighting the

versatility of accounting and its application to all aspects of life, society, and government.53

In

the same way Stevin understood the power of accounting and used his knowledge to precipitate

Holland’s rise as a great world power, Dickens applied double entry accounting to government

50

Louis Goldberg, Jeremy Bentham, critic of accounting method, Accounting Research (July 1957), p. 241. 51

Soll, p. 167. 52

Soll, p. 130. 53

Chatfield, p. 46.

Chang 27

establishments for effective and efficient management practices in a way that Britain could not.

He drew attention to the dichotomy of capitalism in theory and capitalism as it manifested, as

well as the misalignment of accounting in theory and accounting education in nineteenth-century

London. The cyclical nature of poverty trapped the poor, while capitalism increased the wealth

gap and allowed the affluent more privilege and riches. Bureaucratic efforts taken to mitigate

poverty worsened conditions on the streets, while the lack of proper accounting education placed

humble merchants at the whim of those who retained bureaucratic power. Characters in A

Christmas Carol and Little Dorrit include both perpetrators of the systemic nature of society as

well as characters suffering from the constraints they are forced to live in. At a time when money

and the pursuit of wealth spurred society and served as a marker for greatness, Dickens created

protagonists who are well aware of the power of accounting and must grapple with the

challenges posed by a broken economy in order to resume their ethical responsibility to society.

A Christmas Carol is a classic, Christmas novella that espouses the importance of

showing compassion, generosity, and kindness to those that are less fortunate. Published in 1843,

the novella introduced the world to Ebenezer Scrooge, the antagonist-turned-protagonist of the

fable. Scrooge is the miserly owner of a counting house, a man who despises the very idea of

celebrating the holidays and forcefully pushes away family members and those who could be

friends. “Bah, humbug,” he replies to his nephew Fred, wishing him a Merry Christmas,

embodying what is now aptly known as a scrooge.54

But as fate would have it, he is visited by

his former business partner, Jacob Marley, who admonishes Scrooge for his sinful ways and

summons three spirits to give him the opportunity to atone for his wrongdoings: the Ghosts of

Christmas Past, Present, and Yet to Come. Each spirit takes him to their respective domains,

54

Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol (New York: James H. Hieneman, Inc., 1967), p. 10.

Chang 28

allowing Scrooge to relive his life and recognize his wrongdoings in the wake of his forecasted,

untimely, and isolated death. Seeing his own tombstone terrifies Scrooge, and as he is brought

back to reality, he exalts the importance of his ethical responsibility and accountability to other

people, changing his miserly ways and becoming the ideal manager of his personal affairs as

well as society’s well-being.

Little Dorrit similarly warns against the transformative properties money can have on

human nature, by weaving together multiple, complex plotlines that include both families of

extreme poverty and wealth. Albeit exaggerated to be provocative, the tale is representative of

society as the working classes experienced it. Wealth passes from family to family in Little

Dorrit, giving characters the opportunity to make more money and also to lose more money, all

the while changing the lives of those who recklessly deal with their finances. Mr. Dorrit is

imprisoned in the Marshalsea, the very same debtor’s prison that Dickens’ father was in, for

debt. Although Mr. Dorrit is indeed financially irresponsible, the Dorrit family was kept

imprisoned largely in part by Mrs. Clennam, the matron of a large and mysterious business, who

withheld information that could have freed the Dorrits from Marshalsea. When Mr. Dorrit gains

a large lump sum of money, freeing him from jail, he immediately resumes living a pompous life

and invests his money in a scheme that ruins his family and places them back in the situation

where they were at the start of the novel. Arthur, Mrs. Clennam’s son, who helps the Dorrits

uncover the strange family fortune plot, suffers a similar fate as he invests all his earnings into

the same scheme. Only Little Dorrit, Mr. Dorrit’s youngest daughter and an accountant, emerges

unscathed by the destructive properties of wealth.

Chang 29

III

THE RENDERED SYSTEM, OR NEGLECTING THE SOUL

Without an effective, managing government, British society became a hotbed of financial

and moral questionability. But the government did not have the means to audit itself, much less

the numerous corporations in England. The “recurring business crises during the nineteenth

century resulted in a series of new statues and a continuing demand for men trained in

bookkeeping;” accountants were needed to dictate and regulate the terms of modern capitalism.55

Consequently, the British Parliament passed the Bankruptcy Act of 1831, which gave

accountants the authority and legality to manage bankruptcies, auctions, liquidations, and debt

trials.56

Corporations in the private sector began to take action as well. By the 1840s, major

accounting firms like Deloitte, Touche, and Ernst & Young, appeared across Britain.57

Although

this was Parliament’s attempt at mitigating the effects of the financial crises, relegating financial

management responsibility to a designated profession exacerbated the government’s own crisis.

The widespread acceptance of professional accountants and auditors decreased the heightened

need for accountability.

The blatant corruption festering in Parliament also spread to corporations, looming over

society and producing ever more financial information. While accounting methodology used to

shape business practices, the advent of the corporation and the decline in accounting literacy

reversed its role.58

Rather than melding accounting ethics with business objectives, as learned

members of management once did, changes in management, policy, and business conditions

55

Soll, p. 172; Chatfield, p. 112. 56

Soll, pp. 172-173. 57

Soll, p. 173. 58

Chatfield, p. 112.

Chang 30

served as the foundation for corporate accounting practices.59

Business and profit always came

first, and increasingly, “bookkeeping ‘error’ which misstated profits [were] not always

accidental.”60

Opportunities for unethical business or financial transactions during nineteenth

century England was characterized by the convergence of “the spread of capitalist enterprise, the

lack of information on where to invest and on the validity of ventures, together with a relatively

lax system of regulation in the money market.”61

Even members of Parliament participated in the embezzling nature that swept society. In

1855, John Sadleir, Irish banker and MP, sold 19,000 ficticious shares in the Royal Swedish

Railroad Company and then falsified a balance sheet for the Tipperary Bank.62

He and his

brother James, together directors of the bank, owed over £200,000 of their own debt to the bank,

which became insolvent one year later.63

Soon after public realization of his wrongdoings,

Sadleir committed suicide.64

For many Victorian authors, including Dickens, who immortalized

Sadleir as Mr. Merdle in Little Dorrit, Sadleir represented the financial swindler of the times.65

In his private correspondences, Dickens wrote that his fraudulent characters were based on the

capitalist tendencies of the era: “The railroad-share epoch, in the times of a certain Irish bank,

and of one or two other equally laudable enterprises.”66

While the government gingerly approached the crisis, crippling debt, fraudulent figures,

and the negligent governance forced Dickens’ hand. Ineffective, corrupt government officials as

59

Id. 60

Chatfield, p. 113. 61

Paul Schlicke, The Oxford Companion to Charles Dickens: Anniversary Edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), pp. 130-131. 62

Soll, p. 171; Schlicke, p. 130. 63

Id. 64

Id. 65

Soll, p. 171. 66

Frederic George Kitton, The Novels of Charles Dickens: A Bibliography and Sketch (London: Elliot Stock, 1897), p. 164.

Chang 31

well as the wealthy—the very same that Adam Smith warns against—hold the most power in

Dickens’ novels. In light of their own wants and needs, these high-status, money-wielding

individuals forgo the happiness of the general public, despite the latter’s overreliance on the very

people who put them in their precarious situation in the first place, creating a cycle of

dependency and yet disregard.

One of Dickens’ more nonsensical allegories in Little Dorrit is the Circumlocution

Office, a creation that highlights and critiques the ineffective, self-serving bureaucracy of

England. Its exaggerated nature is fitting for the absurdity of the character Mr. Tite Barnacle, a

caricature of administrative government officials, a man known by many as “a man of great

power. He was a commissioner, or a board, or a trustee, ‘or something,’” says Little Dorrit, when

Arthur Clennam decides to help the Dorrits and inquire about their debt.67

As a man high up in

government, Barnacle is linked very closely to the Circumlocution Office and is the most

influential figure in detaining the Dorrits in Marshalsea. No one, however, seems to quite

understand what his role in office is, but everyone knows that he is an important figure. Indeed,

Dickens reveals that the Barnacle family is inextricably tied to England’s affairs:

“They were dispersed all over the public offices, and held all sorts of public

places. Either the nation was under a load of obligation to the Barnacles, or the

Barnacles were under a load of obligation to the nation. It was not quite

unanimously settled which; the Barnacles having their opinion, the nation

theirs.”68

Even the narrator does not fully understand how the Barnacles grew to have so much power. The

opacity that surrounds Barnacle reduces his accountability and the opportunity for his wiles and

ways to be revealed. But it seems as if the Barnacles, as administers of the Circumlocution

Office, made their living by becoming the main perpetuators of the art of “how not to do it,” or

67

Charles Dickens, Little Dorrit (New York, New York: Signet Classics, 1980), p. 95. 68

Dickens, Little Dorrit, p. 103.

Chang 32

the Office’s approach to tackling “whatever was required to be done.”69

This was the “sublime

principle involving in the difficult art of governing a country,” and the Circumlocution Office

“had been early in the field” in discovering such principle and applying it to the way they ran

their office.70

“No public business of any kind could possibly be done at any time without the

acquiescence of the Circumlocution Office,” which is why Arthur pays a visit to the Barnacles,

only to discover that it is altogether impossible to extract any information out of anyone at the

office, for everyone makes their living by circumventing questions and answering instead with

their take on “how not to do it.”71

The Barnacles are the highest-ranking government officials in

Little Dorrit¸ and yet their inability to effectively solve problems and manage the disparate

financial situations that are presented demonstrate a society in which the government is no longer

accountable for its actions and its citizens. Bookkeeping allows the accountant to follow the trail

of money, and yet the paper trail disappears with a government that seems to have no concern for

accounting or their obligation, moral or not, to their people.

Despite their very real concern with running the office in the best manner of how not to

do it, the Barnacles are very concerned with what can be exactly counted and measured. The

narrator describes that

“If another Gunpowder Plot had been discovered half an hour before the lighting

of the match, nobody would have been justified in saving the parliament until

there had been half a score of boards, half a bushel of minutes, several sacks of

official memoranda, and a family-vault full of ungrammatical correspondence, on

the part of the Circumlocution Office.”72

The Circumlocution Office is ineffective because of the pains taken to account for everything, as

illogical as it may be. The Barnacles are numbers-oriented to a fault, focusing on what can be

69

Dickens, Little Dorrit, p. 100. 70

Id. 71

Id. 72

Id.

Chang 33

weighed, counted, and measured instead of what really matters; in the case of the hypothetical

Gunpowder Plot, scores of people dying. This is again represented in individual business

dealings. Barnacle Jr., when approached by Arthur, brushes him off and presses multiple times

whether Arthur is there to inquire about tonnage, a measure that contrasts greatly with the

complexity of the Dorrits’ debt and yet one that can easily be accounted for in the books as well

as for profit.73

These are the very people who might understand why the Dorrits are in prison, but

provide neither reason nor explanation, and yet is the most important department under the

government, rendering hopeless individuals, rather than accounting for those in need.74

This was

a prime example of capitalism gone wrong. The Circumlocution Office and the Barnacles

account only for what can be measured, neglecting the wrongs of society in lieu of their own

petty grievances and desires.

In evaluating the uselessness of bureaucracy, Dickens also warned against another

phenomenon of the time: speculation, fraud, and risky investments. Bubbles that brought ruin to

people were not uncommon in England at the time. Fraudulent figures such as Mr. Merdle in

Little Dorrit, a mysterious, wealthy financier who controls Parliament seats, are able to swindle

innocent folks into investing into their schemes, only for it to unfold and crumble, leaving the

investors in debt and very much in desperation. Mr. Merdle similarly represented all the negative

capitalist tendencies that were reflected in the nineteenth century:

“Mr. Merdle was immensely rich; a man of prodigious enterprise; a Midas

without the ears, who turned all he touched to gold. He was in everything good,

from banking to building. He was in Parliament, of course. He was in the City,

necessarily. He was Chairman of this, Trustee of that, President of the other.”75

73

Dickens, Little Dorrit, p. 105. 74

Dickens, Little Dorrit, p. 100. 75

Dickens, Little Dorrit, p. 239.

Chang 34

He was Sadleir in book form: equal parts bureaucratic official, financier, and sham. Merdle

falsifies a scheme that both Arthur and William Dorrit heartily invest in, only to lose all their

earnings. While Arthur is sent to Marshalsea, Mr. Dorrit passes away shortly after he invests

with Merdle when he hallucinates about being back in prison.76

Despite his newfound wealth, he

is mentally trapped within the confines of his wealth and the prospect of more money,

foreshadowing not only the grim hold the pursuit of wealth has on people and its potential to

bring about ruin, but also the questionable origins of his wealth and his investing.

In addition to warning the public about the dangers of investing, Dickens underscored the

importance of learning accounting and its integral part in managing money—neither Arthur nor

Mr. Dorrit are trained in bookkeeping and invest with Merdle, but Mr. Pancks, who is a trained

accountant, decides not to invest, even though he remarks that it is a highly enticing offer. Mr.

Pancks is the assistant to his landlord, Mr. Rugg, who advertises himself and his services as

“RUGG, GENERAL AGENT, ACCOUNTANT, DEBTS RECOVERED.”77

In starting to work

for Mr. Rugg, the narrator describes Mr. Pancks as a “fortune-teller,” someone who can predict

the future. This line of thought was closely associated with the benefits of accounting, as closely

keeping track of money and where it was going was seen as a way to forecast what was yet to

come. Consequently, Pancks felt that “some new branch of industry made a constant demand

upon him.”78

This new branch of industry was capitalism, and the lack of proper accounting

education explains why he and Mr. Rugg, both professional accountants, are in such high

demand, demonstrating yet again the reduction of accounting to something that is simply ‘done’

by public accountants.

76

Dickens, Little Dorrit, p. 628. 77

Dickens, Little Dorrit, p. 288. 78

Dickens, Little Dorrit, p. 289.

Chang 35

Without individuals looking over their personal financial statements and learning about

the dangers of mismanagement, society fell victim to the dangers of ignorance, from which

grows the tendency to conflate wealth with power. Dickens highlighted the wealth and societal

disparity between the rich and the poor by stressing the implausibility of breaking out of the

vicious, lower-class cycle. While Arthur’s punishment seems more fitting for Merdle, who

created this system and ensnared those who did not know any better, Merdle receives no earthly

punishment. Like Sadleir, he commits suicide, escaping—in a macabre fashion—the

ramifications of his design. Only the poor are left to fend for themselves in a society that does

not value the destitute, counting, instead, what they purported as valuable to themselves.

Similarly numbers-oriented is Ebenezer Scrooge of A Christmas Carol, a single

individual who encompasses all the faults of the Barnacles and the Circumlocution Office.

Scrooge can hardly be more disliked. Even the narrator emphatically describes him as “a

squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous, old sinner,” a man whose “cold

within him froze his old features, nipped is pointed nose, shriveled his cheek, stiffened his gait;

made his eyes red, his thin lips blue… He carried his own low temperature always about with

him.”79

Although it is wintertime, Scrooge is icier and more unfeeling than the elements. The

holiday season evokes warmth and joy, despite the snow, and yet Scrooge remains solitary and

stoic. He stands in great contrast to his assistant, Bob Cratchit, and his nephew Fred, both of

whom are elated to celebrate Christmas with friends and family. He reluctantly grants Cratchit

the day off for Christmas Day, complaining that “it’s not convenient and it’s not fair” to pay

Cratchit wages on a day of no work, even for one day of the year, and asks Fred what right he

79

Dickens, A Christmas Carol, p. 8.

Chang 36

has to be merry when he is so poor.80

His lack of empathy is qualified with an over-calculating

nature. Scrooge counts his time to the second and his money to the penny but never his friends

nor his family. He does not understand the value that the holiday season brings to families and

friends, especially when they spend time with each other, counting instead the wasted time that

could have been put into running his businesses and making more money.

Scrooge is not a crook, but as the sole proprietor of a counting house, he is a

moneylender and profits off the interest on the loans he provides to others. Even in his vocation,

Scrooge is far removed from human interaction, dealing not with exchange of goods or services,

but with cash and credit, further isolating himself from society. He is well-versed in balancing

his books and thus cannot understand why people celebrate when Christmas is just a time when

people “[pay] bills without money… a time for balancing… books and having every time in’em

through a round dozen of months presented dead.”81

He looks down on the very people he

provides credit to for spending on what he believes is unnecessary because Scrooge does not

spend a single penny on himself. The uncomfortable and dreary nature of his home, if it can even

be called a home, is meager and bare: “The fog and frost so hung about the black old gateway of

the house, that it seemed as if the Genius of the Weather sat in mournful meditation on the

threshold.”82

He eats gruel for dinner and hardly lit a fire on such a cold night, unfeeling both in

body and spirit. More than being alone, Scrooge is neglected—either by society or himself. For

someone as cold as Scrooge, his empty, melancholy home possesses a graveyard-like quality,

fitting for a man who seems as if he has lost his soul. Indeed, Scrooge interacts with Jacob

80

Dickens, A Christmas Carol, p. 20; Dickens, A Christmas Carol, p. 10. 81

Dickens, A Christmas Carol, p. 12. 82

Dickens, A Christmas Carol, p. 20.

Chang 37

Marley’s ghost as if he were conversing with human folk; he even wisecracks with the

apparition, the most human he acts toward anyone since the novella began.

Marley, however, has different matters to discuss with Scrooge. He wears a heavy chain

around him, “made (for Scrooge observed it closely) of cash-boxes, keys, padlocks, ledgers,

deeds, and heavy purses wrought in steel.”83

Marley was Scrooge’s business partner while he

was alive and although he did not deal in fraud, he bears the ramifications of his actions in the

afterlife. More than just the money he dealt with in his life, he bears ledgers—it was his penchant

to account for everything that put the banker in purgatory, or perhaps hell. Even though Marley

was more charitable than Scrooge, as he was in the habit of making donations during

Christmastime, he nonetheless made a living on the inability of others to fulfill timely payments

in full. Marley thought he fulfilled his duty by making monetary donations, rather than becoming

active and involved with bettering society, although he certainly had the means to. Contributing

to charity once a year was hardly enough to compensate for the imbalance of personal wealth and

charitable actions he accumulated in his lifetime. He was never wholly accountable for the

welfare of others, saying now that he “[wears] the chain [he] forged in life… link by link, and

yard by yard; [he] girded it on of [his] own free will.”84

Recognizing that he might be fated to a similar path, Scrooge exalts Marley for being “a

good man of business,” to which Marley responds: “Mankind was my business. The common

welfare was my business; charity, mercy, forbearance, and benevolence, were, all, my business.

The dealings of my trade were but a drop of water in the comprehensive ocean of my

business!”85

Dickens provided a caveat to Scrooge’s idea of business, or how he makes money,

83

Dickens, A Christmas Carol, p. 26. 84

Dickens, A Christmas Carol, p. 32. 85

Dickens, A Christmas Carol, p. 34.

Chang 38

with the idea of his business extending beyond his day job. Marley recognizes now that what he

did for a living was a mere portion of how he could have influenced society with “the dealings of

[his] trade.”86

As Adam Smith suggested, happiness is two-fold. True benevolence is accounting

for the happiness of those around him. Scrooge is similarly so absorbed with his vocation that his

attention to detail extends outside his office, only in a pernicious rather than benevolent manner.

Marley’s admonition stresses that Scrooge’s duty as a citizen is not only to further his own well-

being, but also that of the society he lives in. Scrooge spends neither on himself nor others,

hoarding instead his profits for selfish gain. He rightly earns every cent but does not indulge in

health or happiness because he sees no monetary value in such gains. His penchant to rational his

actions and that of others leads him to dismiss the poor and believe that his effort in accounting

for his money, time, and business is why he is better off than many townspeople. Scrooge

believes that the poor should be sent to workhouses and prisons, institutions that serve to house

the “surplus population” because those “who are badly off must go there”—the very people

Dickens despised for rendering and perpetrating the welfare system as it was in England.87

Scrooge’s life ledger, then, has no pleasure, only the pain he extracts from accounting for too

much, and forgetting to account for the intangible rewards in life.

And indeed, the spirit reminds Scrooge why his fiancée leaves him. She recognizes that

he has become overcome with greed. She knows that he would never pursue her now that he

“[weighs] everything by Gain” because even if he did, he would be filled with repentance and

regret.88

“I release you,” she says,

“with a full heart, for the love of him you once were… You may—the memory of

what is past half makes me hope you will—have pain in this. A very, very brief

86

Dickens, A Christmas Carol, p. 34. 87

Dickens, A Christmas Carol, p. 16. 88

Dickens, A Christmas Carol, p. 62.

Chang 39

time, and you will dismiss the recollection of it, gladly, as an unprofitable dream,

from which it happened well that you awoke. May you be happy in the life you

have chosen!”89

She rightly parallels their relationship as an unprofitable dealing, as Scrooge already entered the

stage in his life when he values human interactions and society by their monetary worth. He

gives up the chance for earthly happiness for the opportunity to profit more, replacing warmth

and emotions with cold, hard cash, or what he can physically count. Despite the love they once

shared, Scrooge would rather be without her to further his wealth, and indeed chooses so, a

pointed statement that reveals Scrooge’s decision-making factors and how he came to be.

Before the Ghost of Christmas Future takes Scrooge to see his own untimely death, the

Ghost of Christmas Present says the following to him:

“If man you be in heart, not adamant, forbear that wicked cant until you have

discovered What the surplus is, and Where it is. Will you decide what men shall

live, what men shall die? It may be, that in the sight of Heaven, you are more

worthless and less fit to live than millions like this poor man’s child.”90

Dickens attacked the contemporary society here by remarking on the harmful effects of

utilitarianism in society. In viewing humanity through such a statistical lens, one crafted from

financial or physical metrics, questions arose about what should be done about those outside the

realm of societal protection, or the people that did not constitute that greatest number of people.

Dickens challenged utilitarianism and Bentham’s line of thinking by emphasizing the importance

of a human life. The workhouses and prisons that Scrooge suggests represent the solutions for

dealing with what society felt was the surplus population, as he (and many others) believed that