Casas das Mouras Encantadas – A Study of dolmens in Portuguese archaeology and folklore Quimera 2011: A casa da moura Zaida. University of Helsinki Humanistic faculty, Department of filosophy, history, culture and art studies Master’s thesis in archaeology Henna-Riikka Lindström Supervisors: prof. Mika Lavento, lecturer Antti Lahelma October 2014

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

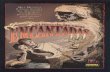

Casas das Mouras Encantadas –A Study of dolmens in Portuguese archaeology and folklore

Quimera 2011: A casa da moura Zaida.

University of HelsinkiHumanistic faculty, Department of filosophy, history, culture and art studiesMaster’s thesis in archaeologyHenna-Riikka LindströmSupervisors: prof. Mika Lavento, lecturer Antti LahelmaOctober 2014

Tiedekunta/Osasto Fakultet/Sektion – Faculty

Humanistinen tiedekunta

Laitos Institution – Department

Filosofian, historian, kulttuurin ja taiteiden tutkimuksen laitosTekijä Författare – Author

Henna-Riikka LindströmTyön nimi Arbetets titel – Title

Casas das Mouras Encantadas – A study of Portuguese dolmens in archaeology and folkloreOppiaine Läroämne – Subject

ArkeologiaTyön laji Arbetets art – Level

Pro Gradu –tutkielma

Aika Datum – Month and year

Lokakuu 2014

Sivumäärä Sidoantal – Number of pages

104 + 13 liitesivuaTiivistelmä Referat – Abstract

Mouras encantadas eli lumotut mourat ovat yliluonnollisia olentoja, jotka portugalilaisen kansanperinteen mukaan asuvatmegaliittihaudoissa ja vartioivat niiden kautta kulkevaa reittiä elävien ja kuolleiden maailmojen välillä.Tutkimus vertailee Portugalin megaliittihaudoista saatua arkeologista dataa ja kansanperinteen megaliittihautoja koskevia tarinoita,käsityksiä ja uskomuksia, tarkoituksena selvittää olisiko fragmentteja muinaisesta uskonnollisesta maailmankuvasta saattanutkulkeutua symbolien tasolla kansanperinteen mukana nykyaikaan asti.

Tutkimuksen teoreettisena taustana on käsitys kollektiivisen mytologian hitaasta muutosvauhdista ja sen ytimen, symbolien,pysyvyydestä. Symbolit ovat mytologian vanhinta kerrostumaa, joiden ympärille kaikki muu on rakentunut ja kerrostunut ajankuluessa. Myytit itsessään muuttuvat yhteiskunnan muutosten myötä, kunkin sukupolven tulkitessa vanhaa materiaalia uudelleenomaan aikaansa parhaiten sopivalla tavalla, mutta symbolit yleensä säilyvät, vaikkakin niitä tulkitaan eri tavoin eri aikoina.

Muutokset hautaustavoissa kertovat muutoksista ideologiassa ja yhteiskunnassa, ja tutkimus seuraa megaliittihautojenarkeologisessa aineistossa tapahtuneita muutoksia neoliittiselta kaudelta rautakaudelle, selvittäen mitä muutokset saattaisivatkertoa kunkin aikakauden yhteiskunnallisesta ideologiasta ja uskonnollisista käsityksistä ja siitä minkälainen merkitysmegaliittihaudoille kulloinkin annettiin. Yhdistämällä arkeologian, folkloristiikan ja historiallisten lähteiden tuottamaa tietoamenneisyydestä tutkimus luo kuvaa niistä kehityslinjoista, joita ihmisten suhteessa megaliittihautoihin on tapahtunut niiden pitkänkäyttöhistorian aikana.

Tutkimuksen tuloksena on, että hyvin todennäköisesti Portugalin megaliittihautoja koskevaan kansanperinteeseen on kertynytaineksia hyvin monilta eri aikakausilta, ja että symbolisten yhtäläisyyksien nojalla on mahdollista, että siinä on fragmentaarisiaaineksia jopa megaliittihautojen syntyaikojen uskonnollisista käsityksistä, neoliittiselta kaudelta saakka.

Avainsanat – Nyckelord – Keywords

Mouras encantadas, megalith tombs, Portuguese dolmens, Portuguese Megalith Culture, archaeology and folklore, dolmen reuse,megalithic art, folklore of dolmens

Säilytyspaikka – Förvaringställe – Where deposited

Muita tietoja – Övriga uppgifter – Additional information

Index

1. Introduction…………………………………………………………………..1

1.1 In the dolmen sat a maiden spinning a thread of gold………………………...1

1.2 Research questions and method………………………………………………..2

1.3 Earlier research……………………………………………………………………6

1.3.1 Studies in folklore…………………………………………………………6

1.3.2 Studies in archaeology…………………………………………………..8

1.4 Source material and the study structure………………………………………10

PART I

2. Megalithic phenomenon, tombs and burial practises…………........13

2.1 Different types of megalithic tombs in Portugal………..……………………..13

2.2 Chronology of different types of megalith tombs……………………………..17

2.3 Where were the megalith tombs built………………………………………….19

2.4 The megalithic phenomenon in the Western Europe and Portugal………...21

2.5 Burials in megalith tombs……………………………………………………….23

2.5.1 Burials in the Neolithic Period 4800-3000 BCE……………………...23

2.5.2 Burials in the Chalcolithic Period (approximately 3000-1800 BCE

and reburials in the Bronze and Iron Ages…………………………...31

3. The art of megalithic tombs……………………………………...………34

3.1 Paintings and drawings in the tombs………………………………………….34

3.2 Symbols in the art of the megalith tombs……………………………………..39

3.3 Some theories and interpretations on Iberian megalithic art………….…….43

3.4 The chist plaques of Alentejo…………………………………………………..46

PART II

4. Folklore on megalithic tombs and mouras encantadas…...………..56

4.1 Short introduction………………………………………………………………..56

4.2 Mouras – builders and inhabitants of megalith tombs……………………….58

4.2.1 Background………………………………………………………………58

4.2.2 The earliest known written references to mouras……………………60

4.3 Where and when to meet mouras…………………………………………….. 63

4.4 Mouras in the shape of snakes and bovines (and goats)……………………65

4.4.1 Symbolism of snake…………………………………………………….65

4.4.2 Snakes and bovines and goddesses in European mythologies…..68

4.5 Spinners of the thread of life……………………………………………………70

5. Megalithic tombs in folklore and tradition……………………...……..73

5.1 The relation between the stories and the narrators………………………….73

5.2 The traditions on megalithic tombs…………………………………………….75

5.3 Mouras and dolmens in toponyms……………………………………………..79

5.4 Church, dolmens and mouras………………………………………………….80

6. Comparing the archaeological and folkloristic data……………...…84

6.1 The symbolic similarities………………………………………………………..84

6.2 Search for the unchanged fragments in the moura –stories………………..86

7. Conclusions……………………………………………………………..….89

References …………………………………………………………………..93

Appendixes ………………………………………………………………..104

1

“On top of the hill are the remains of an ancient monument,

which people here call “anta”. Its tall, dark boulders are

supporting a horizontal stone, like the giant’s table put there for

a formidable feast. This is the house of Moura Encantada..

.. No one can boast about having gone near the dolmen. It is

guarded by a fierce bull, which paws the ground, furious mullet,

running around the dolmen. You can hear its low bellowing from

afar, when it smells a human. It chases away any reckless,

daring adventurers going too near to the “House of Moura”, like

this dolmen is called. Never have people seen a bull like that – it

is the horror of the entire neighbourhood.. “

(Chaves 1924: 209)

1.Introduction

1.1 In the dolmen sat a maiden spinning a thread of gold

Around 5000 BCE started the construction of different megaliths in Western

Europe, and continued throughout the Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods, until

about 1800 BCE (Service & Bradbery 1993:11). The use of these megaliths,

in its turn, as burial and ritual sites, continued sometimes for thousands of

years after their construction, and their use for magical purposes, mainly in

fertility magic, sometimes continued almost to the present day (Holtorf 2000-

2008). The tradition concerning megaliths is very rich in many parts of Europe,

and many themes occurring in it are common to a wide area. Some megaliths

were forgotten – they lost their significance in the lives of the communities and

disappeared from their stories, and in the end they were removed from the

fields to gain room for cultivation, or were used to construct something else.

Other megaliths instead maintained their central position in the traditions and

in the physical and mental geography1 of the human societies, as part of the

1 I´m basing the conception of physical and mental geography on Bintliff´s (2013) article, in which he iscommenting Tilley´s theory about the phenomenology of landscape. According to Tilley´s view, says

2

local identities. Who raised the megaliths? The answer to the question given

by folklore is perhaps a little unexpected, but there has been a rare consensus

about it across Europe – megaliths were built by women. The megalith –

constructing women of the legends are supernatural; they are able to change

their shape and take often the form of a snake or a bull (see e.g. Romero 1998,

Amades 1941). They are simultaneously young and old and have everlasting

life. They are reported to have taught people many skills from herbal medicine

to the manufacturing of iron. They are able to move in different elements –

upon earth and in the underground world, as well as in the watery realm. They

guard the boundaries between the worlds, control the weather and the

seasons, and appear to people in times when the boundaries between the

worlds have become blurred – in the times of approaching death, childbirth,

equinoxes and solstices, or at midnight and at midday (Cuba & al. 1999

[2006]). Besides the megaliths, the supernatural women also built the

landscape itself – hills, mountains and riverbeds are sometimes mentioned to

be their creations (Hull 1927). In other words, they seem to be more or less

omnipotent. No wonder that some scientists have linked them to the old

goddesses (e.g. Almeida, 1974). Where did they go? Nowhere! They still live

in the caves and in the dolmens and create the rainbow on the sky by combing

their golden hair.

1.2 Research questions and method

Travelling through different towns and villages in Portugal my attention was

caught by the many “moura” related place names. Almost wherever I went, I

soon encountered a “Cova da Moura” (Moura’s cave), a “Fonte da Moura”

(Moura’s fountain) and what made me to get interested – many “Casas das

Mouras Encantadas” (Houses of Enchanted Mouras) – by which name the

Portuguese people have been often calling the Neolithic dolmens. If I made

Bintliff, landscape is purely a social construct – a blank space, before it is filled with emotional andsymbolical significance. This is what I call mental landscape. But besides this, comments Bintliff, therehas to be also the landscape of practical and functional resources and work. This is what I call physicallandscape. In my view, these two concepts are intermingling and effecting each other in everyday life ofthe people who are living in the landscape and creating and shaping it with their actions.

3

questions about these mouras, people usually answered that they were

Moorish princesses who had been living in the country hundreds of years ago.

But this didn’t sound satisfactory enough, taking into account that the Moorish

occupation was a fairly short period in Portuguese history, and that it didn’t

cover the whole area of historical Portugal, while the legends of mouras do.

The mouras of the legends and the legends of the mouras show characteristics

which seem to be hinting to more ancient than mediaeval origins, as well as

does the wide spread of similar kind of legends in Europe, and the all-inclusive

way the mouras appear everywhere in the Portuguese folklore.

I started to explore for more information about the mouras and their relations

to dolmens, and found a rich tradition of legends, beliefs, customs and magic

practises recorded by the researchers mainly in the 19th century. Discovering

the mouras as they were seen in the early narratives – powerful, godlike

beings, I started to become enchanted by the subject myself.

In this study I focus on the Portuguese dolmens and the rich folkloristic tradition

surrounding them. I use two different sources of information – archaeological

data and folkloristic material. My aim is to find out how these two fields combine

and cross each other – trying to find out if it would be possible that some

vestiges of the worldview of the people, who built and used the dolmens

thousands of years ago, would have been carried on, on a symbolic level, with

stories and legends, beliefs and practises, to our days.

I will proceed by gathering together material about the oral and practical

traditions associated to the megalithic graves in Portugal, and comparing it to

the material produced by archaeological research. My intention is to figure out

whether the information produced by archaeological research about ancient

rituals in megalithic graves has confluence with folkloristic material. In addition,

my intention is to find out how well the archaeological and ethnological material

is compatible with the recontructions of the religion of the Neolithic megalith

cultures. (For example Almagro Gorbea 1973; Frazão & Morais 2009;

Gimbutas 1989, 1991; Gonçalves 1989, 2004, 2006, 2008, 2009; Muniz 2010;

Rodrigues 1986, 1986b).

4

One starting point for the study is a vision about the religious worldview of the

builders of the megaliths, shared by many researchers (e.g. Almagro Gorbea

1973, Dames 1977, Frazão & Morais 2009, Gimbutas 1989, 1991; Gonçalves

1989, 1992, 2004, 2006, 2008, 2009; Muniz 2010, Rodrigues, 1986, 1986b),

according to which the cycle of life, death and rebirth personified in Mother

Earth had a key role in it. In this view, megalithic tombs would have been built

to express the faith in reincarnation – they would have been built to serve as

wombs of the Earth itself, into which (all) the members of the community were

buried in a collective manner, so that they would be born again.

Another starting point is the idea that the stories, beliefs and traditions related

to the megalithic graves could still carry fragmentary material of the religious

worldview which prevailed thousands of years ago. The idea is based on the

theory outlined by for example Mircea Eliade (Eliade 1952 [1979]: 160-161),

Marshall Sahlins (1985), Jean-Pierre Vernant (1992), Anna-Leena Siikala

(2002) Fernanda Frazão and Gabriela Morais (Frazão & Morais 2009:25-40)

according to which the collective mythology of human societies might carry on

fragments of the ancient worldview, and that by following its symbolism it would

be possible to try to reach the ancient religious concepts.

By the human collective mythology I refer to the story tradition which is

essential to the self-identification of a community. The tradition presents the

criteria and the conditions for the existence of the community and its social

order. It tells about the birth of the community and the birth of its residential

area, and about the community’s ties to the area and its justification over it. It

defines how the community is different from other communities, and includes

moral norms and custom rules which unite the members of the community –

teachings about what kind of behaviour is acceptable within its moral

framework. The collective mythology is closely linked to the community’s own

living space. Often it includes a direct requirement to pass the tradition on to

new generations as a condition for the continuing of the community, thus

guaranteeing its own continuity. It is opposed to change, but changes when

5

necessary. The myths grow from the community and the community from the

myths, and one would not exist without the other. (Eliade 1959:149-150.)

Myths have a central position in world view and thus they are able to illuminate

past models of thought. By codifying the structures of a world view, myths carry

mental models of the past. The most fundamental areas of cultural

consciousness are related to the community’s world view and basic values;

mythology is constructed as a representation of precisely such basic structures

of consciousness. (Siikala 2002: 15-16.) The time, history and the change of

the social structures pile up additional meanings to the symbolism of the stories

and change them, but neither the symbols nor their structure change much

(Eliade 1952 [1979]: 160-161). Hartsuaga Uranga (2011), talking about

Basque mythology, compares it to an onion – the outermost peel is dirty and

of varied colouring. It is also the youngest layer. If we want to see how the

onion looked when it was young, we have to peel off layer after layer.

Stories themselves change over time and space, as society changes and the

geographical distance increases, but their most important elements, the core,

symbols, would remain unchanged. (Eliade 1952 [1979]: 160-161). The

surface elements come and go and take new forms, but the most essential

elements of the mythology form the structures of consciousness, needed to

sustain a world view and to resolve contradictions. Thus they are deeply rooted

and conservative. Myths are amongst the most tenacious forms of mental

representation. (Siikala 2002:16.) According to Hartsuaga Uranga (2011) the

folk stories, beliefs and legends are often fragmented myths or myth

fragments. The fragmentation happens when the social change is slowly

changing the traditional world view, so that the myth becomes, generation after

generation, in a very slow process, partly incomprehensible for the people

reciting it. When all else is gone, the symbols remain. The symbols are able to

put us in touch with the mind-set of societies that developed codes of

symbolism over thousands of years (Tresidder 2004).

Legends respond to social change by changing too. Looking at Portuguese

prehistory and the social changes taking place in its course I’m trying to keep

6

track of the layers the social changes have been piling onto the story tradition,

and look at what is left when the layers are removed - what is the unchanging

core of the tradition common to all the stories. I’m not searching for a

continuum extending uninterrupted and unchanged from the megalithic period

to the present day – I study a hypothetical possibility of fragmentary religious

material being carried through legends and practices. What interests me is:

Could the story tradition still alive in some areas of Portugal, and the beliefs of

clearly non-Christian origin about megalith tombs have their basis in the beliefs

and customs of the megalith period? After all, the idea that we would be able

to truly reach even fragments of the worldview of the people who lived

thousands of years ago is incredibly fascinating.

Portuguese megalithic tombs suit as a material for this study very well,

because the traditions related to them are exceptionally strong, and because

many of the tombs have been used in one way or other in religious, magical or

communal practices from the Neolithic time almost to the present day. The

significance of the megaliths in the lives of the people who live around them

certainly has changed many times over – what people think about them, what

meaning they give to them in their own personal lives and in the life of the

community, and how they do explain their existence. Change is particularly

significant for this study. Meanings change, but the Portuguese megaliths have

never lost their significance – become meaningless.

1.3 Earlier research

1.3.1 Studies in Folklore

There is no earlier study combining the archaeological data and folkloristic

material about the Portuguese mouras encantadas and the dolmens in the way

I’m going to do. Luckily there is plenty of folkloristic material collected mainly

in the 19th century, and the archaeological studies of the dolmens relevant to

this study, focusing on the continuity of their use, the art in and around them

and the studies on the burial practices etc. are numerous.

7

The greatest part of the traditions associated with mouras were collected in

the end of the 19th century. The most central early collectors were José Leite

de Vasconcellos (1858 –1941), Francisco Xavier d´ Ataíde de Oliveira (1842

– 1915), Teófilo Braga (1843 – 1924), Consiglieri Pedroso (1851 – 1910) and

Luís Chaves (1889-1975), who collected Portuguese folklore in different parts

of Portugal and of various fields, including traditions conserning mouras

encantadas.

During the Portuguese dictatorship (1926-1974) studying the non-christian

traditions was in disfavour. Some studies concerning mouras were made

outside Portugal – by Galicians Juan Amades (1890-1959), who collected

traditional stories about the megalith builders and beliefs related to dolmens

in the Iberian Peninsula, and Fernando Alonso Romero, who compared the

Galician tradition of mouras as constructors of the megaliths to other

European traditions of megalith builders; and by English Eleanor Hull (1860 –

1935), who connected the Gaelic Cailleach Bheara –traditions to Iberian

mouras.

Newer studies have been made e.g. by Fernanda Frazão & Gabriela Morais,

who published a comprehensive study in three volumes: Portugal – O Mundo

dos Mortos e das Mouras Encantadas in 2009, in which they wrote about the

connections of mouras to various aspects in Portuguese culture in a wide

range from linquistics to mediaeval legends and to certain characteristics of

the cult of Virgin Mary(s); Alexandre Parafita, who published 2006 “A

mitologia dos mouros” – a study about the legends considering mouros and

mouras in the Trás-os-Montes area, northern Portugal; and young

archaeologists Jesus Chaparro, Andrés Blanco and Valentín Martínez, who

interviewed local people about the moura -traditions and other traditions

related to megalithic monuments during their archaeological field studies in

Galicia 2010, and published the results in an article Percepciones míticas y

pautas de comportamiento en tornoa los espacios megalíticos de montaña,

2011.

8

1.3.2 Studies in Archaeology

The earliest studies about Portuguese megaliths were done mainly by the

same people who collected Portuguese folklore, since the two scientific fields

had not yet been grown apart. In his article Megalithic monuments in Spain

and Portugal (1887) Jean-François-Albert du Pouget de Nadaillac mentions

that at a conference held in connection with the International Exposition in

Paris in 1867, Gabriel Pereira, a Portuguese anthropologist, had presented a

list of 118 megalithic constructions in Portugal.

In the 19th and early 20th century the focus was on typologies of tombs and

archaeological artefacts and objects. In the excavations much attention

wasn’t given to the human remains, because, typically for the megalith

burials, the remains were deliberately scattered. Most descriptions of tombs

excavated in past centuries gave a picture of broken and commingled bones,

without any clear contexts, except when artefacts or better preserved skeletal

remains were detected. (Boaventura et al. 2014: 184.)

One of the most noticeable achievements in the first half of the 20th century

was the work of Georg and Vera Leisner. They excavated, documented and

published a huge amount of megalithic tombs, starting in the early 1930´s.

Their main work is the monumental publication Megalithgräber der Iberischen

Halbinsel 1943.

From the 1920´s to 1960´s the main focus in studies of megaliths was on

theories trying to explain the routes and directions of cultural influences, and

to figure out if the megalith builders in Portugal were indigenes or colonists

(Jorge 1987). According to the most prevalent view whole European

megalithic phenomenon was itself an indirect reflection of contemporary

oriental civilization, carried as part of a mortuary cult by seaborne

missionaries along the Atlantic coastlands (see e.g. Childe 1949).

Radiocarbon chronologies turned this theory upside down during the 1960´s.

The new technologies of dating, excavating, sampling and material analysis,

and also the social changes after the 1974 revolution changed the course of

9

interests. Most research relevant to this study has been done from the

1980´s onwards. I’m going next to list shortly some of the research lines most

significant for this study.

The life histories and reuse of West-European megalithic graves in later

prehistory has been studied widely in the 21th century, in Iberia for example

by Leonardo García Sanjuán, Pablo Garrido González & Fernando Lozano

Gómez (Sanjuán 2005, Gómez et al. 2007, 2008) and Rui Mataloto (Mataloto

2007). Katina Lillios has also been doing research on different mnemonic

practices, for example on the reuse of the Iberian decorated schist plaques

by later generations (Lillios 2010). Katarina Oliveira contributed this line of

study with her book Lugar e Memória (Oliveira 2001), in which she discusses

megalithic monuments as places of memory.

The art in the megalith tombs in Iberia has been studied for example by

Primitiva Bueno Ramírez, Rodrigo de Balbín Behrmann & Rosa Barroso

Bermejo (Balbín Behrmann & Bueno Ramirez 2000, 2006; Balbín Behrmann

et al 2010, 2012), Vitor Oliveira Jorge (1998, 2003) and Leonor Rocha (2004,

2012). Jorge’s and Rocha’s studies have focused on the distribution and

interpreting on different symbols. Bueno Ramirez et al. have been for

example comparing the symbolics found in the tombs to the symbolics in

open air rock art sites and in the different types of idols. They have been

breaking many old conceptions with their studies about the distribution and

chronology of paintings and engravings in Iberian megalith tombs.

The studies of Victor S. Gonçalves cover many themes, which are very

important to this work. He has been comparing the artefacts and burial

practices in different types of megalithic tombs and studied the chronology

and the symbolics of the slate plaques (Gonçalves 1989, 1998, 2004, 2006,

2008, 2009, 2011). Katina Lillios had been doing also lots of research about

the schist plaques. ESPRIT, the digital Engraved Stone Plaque Registry and

Inquiry Tool is her creation. ESPRIT is the first comprehensive and

searchable catalogue of the engraved stone plaques of late prehistoric Iberia

(Lillios 2004).

10

Osteology in megalithic tombs has been developing in Portugal from the

1990´s onwards. It´s results are important, telling about people buried into

the graves – information about their sex, age, health and about the treatment

of the bodies. Ana Maria Silva and Rui Boaventura are amongst the most

notable researchers on this field (Silva 1997, Ferreira & Silva 2007,

Boaventura et al. 2012, 2014).

The research of the orientations of the megalith tombs according to

astronomic events or towards special features in the landscape is still young

in Portugal. One of the most published authors is Fabio Silva (2011, 2013).

1.4 Source material and the study structure

The selection of source material for this work is the result of weeks spent in

the libraries of IGESPAR (Instituto de Gestão do Património Arquitectónico e

Arqueológico), Biblioteca e Arquivo Histórico do Museu Nacional de

Arqueologia and the Bibilioteca Nacional de Portugal in Lisbon, reading and

copying material. Some material I have found through internet. All the

folkloristic material I’m using is from secondary sources – from studies and

collections already published, because it has not been possible for me to go

through archives or to make interviews myself.

The geographical outlines for this study are not very firmly set because of the

nature of the subject. The main focus of the study is in the graves of the

megalithic culture in Portugal, and in the folklore connected to them, but as

far as the archaeological material is concerned I have found it useful to

include research material from the whole Iberian Peninsula, and allow

comparisons between contemporaneous megalithic cultures in other parts of

Europe as well. I defend this procedure with the clear connections and

similarities amongst the West-European megalithic cultures, especially when

it comes to the symbolic level, which is essential for this study. The same

11

principle goes with the folkloristic material – although the legends and

customs related to the megalithic monuments are very local and usually

connected to the monuments of a certain area, the similarities in the

folkloristic material are very obvious in a wide geographical area in Europe,

and thus it would seem an artificial attempt to outline strict geographical

limits, which don’t exist in reality, for the study, or to use the now existing

state borders, which certainly didn’t exist in the prehistoric times.

Chapter 1 of the study works as an introduction. In it I’m discussing the

research questions, earlier studies and the methodology of this study. I’m

also telling shortly about my personal interest in the subject.

Chapters 2 and 3 form the Part I of the study, in which I deal with the

archaeological data, while chapters 4 and 5 form Part II, in which I discuss

the folkloristic material. In chapter 2 I give first a short general overview onto

the megalithic phenomenon – an introduction to the megalith graves and the

burial practices in them, and to the megalith grave types in Portugal, their

dating, distribution and the regional differences. I deal also with the possible

link between the spreading of the neolithism in Europe and the spreading of

the megalithic culture in Portugal, and with the main characteristics of the

Mesolithic and Neolithic culture in Portugal. Next I discuss in a more detailed

way the burial practices in the Portuguese megalith graves throughout the

whole time span of their use, from the Neolithic period to the reuse in iron

age, simultaneously carrying along the parallel theme of the social change,

taking into account the possible reflections of the changes in the burial

practices through some example cases.

In chapter 3 I deal with the art in the megalithic graves. In it I give a

description of the art and the symbols included in it, cover the disposition of

the painted and engraved art inside the graves, give some interpretations

made of it and discuss its connections to the contemporary rock art. The

Alentejo schist plaques are discussed in a separate sub chapter, in which I’m

dealing with their manufacture, distribution, dating, positioning in the graves,

12

the symbols engraved onto them and some interpretations made about them,

the link between their amount and the amount of the bodies buried into the

graves, and their connection to the other art in the megalithic graves.

Chapter 4 starts with a short introduction to the second part of the study,

which deals with the folkloristic material. In this chapter I discuss first

generally the mythological characters, called mouras encantadas, living in

the dolmens in the Iberian tradition, and then in a more detailed way – their

role as the guardians of the borders between the worlds, and as escorts of

souls between the worlds, their role as helpers and as benefactors of fertility.

Next I tell about the different manifestations of mouras in the shape of snakes

and bovines, and the symbolic values traditionally given to those animals in

question. Then I tell about the connections of mouras to some of the

shapeshifting characters in the folklore of other parts of Europe. Next I

describe shortly the snake cult in Iron Age Portugal. Then I discuss about the

mouras in the role of spinners of the thread of life, the dichotomy of life and

death and the view of cyclic course of life and time.

In chapter 5 I discuss the megalith graves in folklore. I tell about the

collecting of the oral tradition – when and where it was collected, who were

the people telling the stories and what was their relation to the stories they

were telling, what was told about the megaliths, what was the relation of the

communities to the megaliths, what role did the megaliths and mouras have

in the life of the community. I tell about the practical traditions connected to

the megaliths – what did people do to them or with them – beliefs and fertility

magic. Next in the chapter six I give some typical examples of the moura

stories from the folkloristic collections, examples of place names with linking

to dolmens and mouras, and then I discuss the reactions of the church to the

beliefs and practises concerning dolmens and mouras amongst common

people.

13

In chapter 6 I’m comparing the archaeological and folkloristic data, piece by

piece, and demonstrating the possible confluences.

In chapter 7 I give the conclusions I’m making on the basis of the studied

material.

PART I

2.Megalithicphenomenon,tombsandburialpractises

2.1 Different types of megalithic tombs in Portugal

The building of megalithic constructions started between 4800 and 3800 BCE

on a wide area of Western Europe (Map 1). The earliest megaliths were

menhirs or individual standing stones, and cromlechs i.e. stone circles. In

Portugal their erecting started round 4800 BCE. Thus far the oldest dating for

a megalithic construction in Portugal has been made for the first building phase

of the Cromlech of the Almendres near Évora, 4800 cal BCE. (Gomes

1997:28.) (Fig.1.) Building of megalithic graves started some hundred years

later (Boaventura 2011). The radiocarbon datings for the earliest megalithic

14

graves in Portugal places them to the turn of the 5th and 4th millennia BCE

(Senna-Martinez et al. 2008).

Map 1. The megalithic cultures in Western Europe. Source: Cromwell 2014.http://www.cromwell-intl.com/travel/megaliths/

The basic types of megalithic graves in Portugal are a) dolmens, consisting of

large vertical upright wallstones i.e. orthostats, with a large flat capstone

forming the roof (Fig.2.) and b), tholoi – vaulted chamber tombs, in which the

roof structure is a corbelled dome supported by the orthostats (Figuereido

2004). (Fig.3.)

15

Fig. 1. Cromeleque dos Almendres. Photo by author 2013.

Fig 2. Dolmen Anta 2 do Barrocal (Évora). Photo by author 2013.

The stone chamber served as the burial chamber. Some graves have a

corridor leading to the chamber (Fig.4). Sometimes the graves are, or were

originally covered by a mound of earth or stones or a mix of both, though in

many cases the covering has weathered away, leaving only the stone

"skeleton" of the burial mound intact. Some graves have also had a special,

outside space, in front of the entrance, called “atrium”. This space was

separated from the surrounding area for example with a pavement done from

16

small pebbles, which sometimes were of a special color. The atrium was

possibly used in rituals connected to the burials done in the grave, and possibly

also in other ceremonies which took place around the dolmen. (Sanches

2006.) (Fig.5.)

Fig.3. Source: The history of Spanish architecture 2012.http://www.spanisharts.com/arquitectura/i_inicio.html

In Portuguese language dolmens are usually called with the word “anta”, or

with the word “orca/arca/urca” in Northern Portugal and Galicia. Other, more

locally used words for dolmens are “altar” and “mamaltar” = mama + altar

(breast/mother + altar). (Chaves 1951: 96-97.) Dolmens still covered by the

mound are called mamoa – a name which refers to the female breast, because

of the shape of the mound. In the case of Portugal, also the caves and artificial

caves or rock cut tombs have to be included into the study of the burial

practices of the Megalithic cultures, as they form part of it – the material

remains and the symbolic language in them are similar to that in the dolmens

and tholoi, and the burial rituals practiced in them have probably been similar

too. Apparently they belonged to the same magic-religious tradition.

(Gonçalves, 2009: 239.) According to Boaventura et al. (2014), over 3000

17

megalithic tombs – natural caves, dolmens, artificial caves and tholoi – have

been recognized in Portugal since 1850´s. (Map 2.)

Fig.4. Anta Grande da Comenda da Igreja. The entrance to the passage in front, theburial chamber on the back. Photo by author 2013.

2.2 Chronology of different types of megalithic tombs

The collective burial practice is typical for megalithic culture, but it pre-dates

the megalithic graves. It started in the natural caves – the caves were used as

burial sites long before, since Paleolithic era, but somewhere between 5000

and 4000 BCE there started to emerge changes to the burial ritual and to the

composition of grave goods. This far the earliest radiocarbon dated burial site

in Portugal, which can be linked to the megalithic culture, is from the Gruta do

Cadaval natural cave in Estremadura, Central Portugal. With an individual

covered by a big slab of stone, were the remains of artifacts typical also for the

earliest burials in dolmens – thin blades, axe, adze, shell beads, geometric

microliths and fragments of ceramics (although the ceramics is a rarer find). In

the cave were bones from at the least 24 individuals, who had been buried

there inside a fairly short time span. The radiocarbon date obtained from

human bones for this burial is 4150-3790 cal BCE (limited to 4060-3790 cal

18

BCE with 94.8% probability). The use of natural caves for collective burials

continued until the middle or third quarter of the 3rd millennium BCE,

simultaneously with dolmens and other types of tombs. (Boaventura et al.

2012.)

Fig. 5. Atrium of dolmen de Antelas. Source: Laranjeira 2013.http://antelas-omeulugar.blogspot.pt/2013/01/dolmen-pintado-de-antelas.html

The building of dolmens started fairly simultaneously in different areas of

Portugal, round 4000 BCE. This far the earliest dating for dolmens in Southern

Portugal are from Alentejo – The dolmens 2 and 3 of Vale de Rodrigo were

dated (3940-3520 cal BCE and 3940-3700 cal BCE). The radiocarbon dating

for these dolmens was based on charcoal. (Boaventura et al. 2012.) In

Northern Portugal for example dolmen de Antelas has given early datings:

4328-3998 cal BCE 2 sigmas and 4315-3981 cal BCE 2 sigmas (Senna-

Martinez et al. 2008). The artificial caves, also called rock-cut tombs, are a

slightly younger type of graves than dolmens. The earliest known dating is from

Sobreira de Cima, Alentejo, based on the bones of one individual, which were

dated 3640-3350 cal BCE. The radiocarbon dating for other artificial caves in

Alentejo and Algarve fall on between 3300 and 2900 BCE. (Boaventura et al

2012.)

The tholoi tombs seem to have been built mainly between 2900 – 2400 BCE

(Boaventura et al. 2012). There is no very reliable radiocarbon dating for this

type of tombs – the existing bone samples being taken from contexts possibly

19

mixed with earlier rock-cut tomb burials (Boaventura 2011). All four types of

tombs – the caves, dolmens, artificial caves and tholoi, were in use at the same

time and in the same areas. Ideologically, what was in stake, was probably

only the different implementations of the same theme. (Gonçalves 2009:249.)

Map 2. Distribution of megalithic tombs in Iberia. Source: Rocha 2004.https://dspace.uevora.pt/rdpc/bitstream/10174/2301/1/SinaisPedra.pdf

2.3 Where the megalith tombs were built

The selection of the spot in which the dolmen was erected seems to have been

very relevant. Dolmens were often built on places which possibly had

preceding ritual significance. In Portugal it was common to erect the dolmen

on a site where there already was a menhir (Lillios 2010). The mound which

was piled over the dolmen also swallowed the menhir in some cases (Alvim

2010: 29-30). In some cases the menhirs were reused in building a dolmen

(Calado & Rocha 2008: 61).

20

Also the reuse of the old living sites as burial places was common throughout

Europe in the megalithic cultures, and that is the case in Portugal too. The

phenomenon has been linked for example to the cult of the ancestors, the want

to incorporate the structures made some generations earlier to the new cult

complex. (Goméz et al. 2008.)

Excavations have shown that various ritual acts were performed during the

process of building a dolmen. For example the stones for the dolmen were

chosen carefully – they were often of unusual colour or texture, and were

sometimes brought behind long distances (see for example Boaventura 2000,

Kalb 1996). On the bottom of some dolmens were deposited rare pebbles, and

fires were burned in many phases of the construction. It seems that the

headstone of the dolmen (opposite the entrance) was erected first. In the ready

dolmen the headstone played a significant role – in decorated dolmens it is

always the most decorated stone. Often the headstone is also the biggest

orthostat, and frequently sculpted as a stele. It is possible that it had a central

meaning in the rituals performed already before rest of the dolmen was

erected. (Sanches 2006.)

During some excavations, under the dolmens has been found a layer of

scorched earth. This has been interpreted for example to be a part of

“purification” of the land prior erecting the dolmen. Under the dolmen number

3 in Vale de Rodrigo (Alentejo) was found a thick layer of dark clay, which had

been brought to the site from a nearby river bottom to cover up the remains of

earlier residential layers. (Armbruester 2006: 53.)

Another suggestion made about the process of selecting certain places as

sites to erect dolmens, is a theory based on the studies by Flores et al. about

dolmens as signposts, erected along the herding routes to outline the

landscape and to serve as road signs, from which the ancestors would be

guiding the footsteps of their descendants, quite literally (Flores et al. 2010).

It is clear that the orientating of the dolmens (the entrances of the dolmens)

towards different astronomical events, or towards meaningful spots in the

landscape, have also had its impact for the choice of place. Most Iberian

21

dolmens are orientated towards east, to the rising sun (Jorge 1998:77) or

towards the Spring Equinoctial full moon (Silva 2011). In Mondego Valley in

the Central Portugal the dolmens are orientated towards Serra da Estrela (Star

Mountain Range) and towards the rise of particular red stars, Betelgeuse and

Aldebaran, over the mountain range at the onset of spring. The Neolithic

transhumance community moved in spring with their flocks up onto the Serra

de Estrela, and back down to the Mondego valley in autumn. (Silva 2013.)

From that point of view the rise of the stars over the Serra de Estrela in spring

was a significant event.2

2.4 The megalithic phenomenon in Western Europe and Portugal

Under the title “Megalith Culture” has been placed various different cultures

in wide area of Western Europe. Nevertheless, they seem to have been

connected by similar symbolism, burial practises and presumable also by

similarities in the ideology behind those. The regional differences in

decorating and constructing of megaliths, the differences in grave goods and

their positioning inside the graves, and the differences in the treatment of the

bodies, are probably partly results of different resources, for example building

materials, in different environments, and partly caused by local traditions, the

roots of which are farther back in the prehistory.

The beginning of the megalith construction – erecting the menhirs and

cromlechs aka stone circles – seems to go in Portugal fairly well hand in

hand with the neolithization. The earliest monuments were, according to

Calado and Rocha (2008:61), the result of the absorption of the Neolithic way

of life by the indigenous late Mesolithic communities. In the Mesolithic time

2 It is interesting that the local folklore gives support for the idea of transhumant community followingthe stars – a popular legend tells about a shepherd who loved a star. “There once lived a shepherdwhose only friend was his dog. This shepherd longed to travel to the mountains beyond his village. Onenight while gazing at the starry sky a star with the face of a child came down and spoke to him, sayingthat it would guide the shepherd to where he wished to go. So the shepherd walked for years and years,looking for his destiny, with the star smiling down on him. One day he came to the top of the highestmountain he could find. Because it was closer to the sky and his star he decided to stay there and go nofurther. This, according to the legend, would explain the name of this mountain range. (Beyondlisbon2013.)

22

the population in Portugal was concentrated in estuarine and coastal regions,

where resources were varied and abundant. Stable isotope analysis of

carbon and nitrogen in bone of human remains from Mesolithic burials in

Portugal has shown that the Mesolithic groups had a diet comprising 50%

marine foods. They built their houses over huge shell middens formed of the

shells of marine molluscs, and buried their dead into them. In the later part of

the period, many of these Mesolithic sites were utilised all year round and

reflect a semi-sedentary settlement pattern In Portugal. (Chandler et al.

2005.)

Neolithic phenomena first began in Portugal in the fertile southern riverside

plains (Cardoso & Carvalho 2003). In the archaeological record the

neolithization shows first as ceramics and domesticated sheep or goats.

Probably also small scale horticulture was part of the economy, but the

neolithization process in Portugal was very slow. The economy of most

communities was based on mixed – new and traditional – resources,

combining gathering, hunting, herding and horticulture. The proper farming

based economy started somewhat later. (Frank & Silva 2013.) For example,

in the Algarvian shell midden site Barranco das Quebradas, only the

youngest, surface layers, contain ceramics (Bicho et al. 2003).

The megalithic burial practices began a little bit later than acquiring new

Neolithic economical practises. The burials were made in caves, but the

burial practice and probably the ideology behind it were already similar than

in the megalith graves a bit later (Cruz 2000: 74). The earliest known

Neolithic residential site in Portugal is the Cabranosa site in Sagres, Algarve.

It was a sedentary settlement with domesticated sheep or/and goat and

locally produced cardial vases. The radiocarbon dating from sheep/goat bone

gave the result 5700 cal BCE. (Cardoso & Carvalho 2003.) There is other

early datings from different regions of the country, fro example from Pena

d´Aqua in Estremadura (5400 cal. BCE 1 sigma) and from the Mondego

valley, about 5000 BCE. There is, though, big variation even inside small

regions in adopting the new Neolithic practices. (Bellwood 2005.) And on the

other hand, there was also communities who continued their Mesolithic

23

lifestyle based on hunting and gathering and sea resources, but who

nevertheless started to erect megaliths at the same time (4800-4400 BCE)

with the communities who had, at least partly, adopted the Neolithic economy

(Señóran Martín 2008:438).

Some scientists, like Senna-Martinez (1995), connect the shift to the

collective burial and the removing of the individuality of the bodies with the

social transition towards more democratic society ideal, which probably

happened during the Neolithic period. This, in turn, would be a reflection of

the collective form of farming in its early stages, before the emerging of the

idea of private landowning (Silva, T. 1997: 580). Some researchers (e.g.

Getty 1990, Pennick 2000) reckon that the continuously increasing

dependence on the fertility of the land and the production of the fields led to

worship of the earth and to a fertility cult, which would have been focused

around the goddes personificated as Mother Earth. According to this

interpretation, the megalithic tombs would not actually have been graves, but

symbols built to represent the uterus of the Earth itself, where the dead

bodies or parts of them would have been positioned – like a seed – so that

they would be able to be born again (Dames 1977:30, Gonçalves, 1992:37-

50).

Most likely the transition to the Neolithic economy has further increased the

interest to follow the cycle of nature, celestial bodies and time, and may have

led into a cyclic conception of time, in which everything, including humans,

are part of the endless cycle (Gómez et al. 2007:123). The astronomical

orientations of the stone circles and megalithic tombs towards the sunrise of

solstices or equinoxes also tell about the importance for megalithic cultures

to monitor the flow of time. (Alinei & Benozzo 2009:36).

2.5 Burials in megalith tombs

2.5.1 Burials in the Neolithic Period 4800 – 3000 BCE

The existing knowledge about funerary customs in Portuguese megalithic

24

graves is far from complete. The acidic soil preserves bone poorly. The

bones placed on the bottom of the dolmen are at the mercy of the animals,

roots, weather and geological factors. Completely intact dolmens are found

only rarely. Large proportion of dolmens has been used continuously for

hundreds of years, and often also reused in later times, and the layers are

mixed. (Silva 1997:211.) Treasure seekers have also caused destruction. A

large part of the excavated dolmens were excavated during the so-called

”Black Period” of Portuguese Archaeology, 1930 -1974 – i.e. during the

dictatorship – when the study of the past was in disfavour, the publishing was

infrequent, and the methods used were sometimes haphazard. (Gonçalves

2006.) Systematic study of human remains of megalith tombs started in

Portugal only in the 1990´s.The fragmental, scattered bone material wasn´t

earlier in the focus of archaeological interest. (Boaventura et al. 2014.)

It seems that there was great variability in the funerary customs as well as in

the ways the dead bodies were treated, which is understandable taking into

account the long period of usage of the megalithic graves. Different

secondary burial practices seem to have been common. Probably only the

bones were placed into the smaller dolmens, after the body had first been

either buried to the ground until the soft parts had decomposed, or the flesh

was separated from the bones in some other way. Into the bigger dolmens

the bodies were placed as whole. When new corpses were brought in, older

remains were moved aside or bones grouped according to a specific formula

– femurs in one stack, skulls in another etc, or they could be arranged

according to age groups – one stack for adult’s bones, another for children’s

bones and a third pile for the bones of infants. In two intact dolmens the

bones were arranged on the floor ornamentally to form patterns which

resembled the geometrical motifs seen in the contemporary rock art and in

the art of the dolmens. (Silva 1997:212.)

In some cases there are cutmarks in the bones, which has been interpreted

most likely to be caused by disarticulation and defleshing connected to the

bone cleaning of secondary burial practices. This is the case for example in

dolmen of Carcavelos, Central Portugal, which has a very long period of

25

usage, from about 3500 BCE to 2200 BCE, according to the fact that

amongst the grave goods both geometric microliths (typical to early

Neolithics) and bellbeaker ceramics (late Neolithic/Calcolithic period) were

present. In the dolmen were bone remains from 80 adults MNI (minimum

number of individuals). In the microscopic and macroscopic analysis 24

cutmarks were recognized. The children’s bones were not studied. (Antunes-

Ferreira et al. 2008.)

The minimum number of individuals (MNI) in the megalith tombs varies

greatly – from under 10 to over 400. In the tholos of Paimogo 1 there is an

estimate of 413 individuals (Silva 2003). This is probably partly explained by

the long span of usage of some tombs. It seems that the number of

individuals in the graves was growing towards the late Neolithic and

Calcolithic periods. (Boaventura et al. 2014.) Both sexes and all age groups

are represented amongst the bone material of the dolmens – there is no

signs for example of favouring one sex at the expense of the other (Ferreira

& Silva 2007:14-15), although the bone material analyzed from megalithic

tombs in Algarve and Estremadura indicate a sex ratio in favor of females

(Boaventura et al. 2014). Due to the lack of preservation of the bone material,

it is difficult to assess how big proportion of the community members were

buried into the dolmens, but the blending of the bones and the deliberate

destruction of the individuality of the deceased has usually been interpreted

as signifiers of a prevailing ideal of a somewhat democratic society, in which

everyone was guaranteed a share of the life after death (Gonçalves 2008).

In some dolmens the bones have been burnt, and also the artefacts in the

dolmens sometimes show signs of fire. In some dolmens there is a mixture of

burnt and unburnt bones. (Cunha et al. 2007:110.) Sometimes there is radial

lines carved into the bones which have been interpreted to represent the rays

of the sun (Cunha et al. 2007: 116). (Fig.6.)

26

Fig. 6. Carved lines on a bone from dolmen Anta do Olival da Pega 2. Source:Cunha et al. 2007. http://www.uc.pt/en/cia/publica/AP_artigos/AP24.25.07_Silva.pdf

The bones are often cleaned by light sanding and then painted with red ochre

(Gonçalves 2003: 274-275). The grave goods are situated inside the

dolmens in a way which makes it impossible to connect them with any

individual deceased. For example, the ceramics are sometimes set on line in

accordance with the longitudinal axis of the dolmen (Leisner et al.

1951[1985]). (Fig. 7.)

27

Fig.7. Ceramics along the longitudal axis of the dolmen. Anta 1. do Poço da GateiraSource: Leisner & Leisner 1951[1985].

The most common artefacts situated into the megalithic graves in the earlier

phase of their use were geometric microliths, pottery, usually plain and

globular (Fig. 8), polished stone axes and chisels and small zoomorphic

sculptures (Leisner et al. 1951[1985]:145-146). (Fig.9.) In the later phase the

28

arrowheads, big flint blades and the decorated schist plaques (the plaques

after 3500 BCE) are common finds. The ceramic styles wary more and the

zoomorphic sculptures are still present.

Fig.8. On the left: ”Dolmen type” pot, Middle-Neolithic period, Anta Grande daComenda da Igreja. On the right: Late Neolithic pot with three nipples, Anta 1 doPoço da Gateira, Source: Museu Nacional de Arqueologia 2014www.Museuarqueologia.pt

The manufacture of the so called Alentejan schist plaques began around

3500 BCE and continued for about thousand years (Gonçalves2011). They

are about palm-sized, thin plaques made of schist or slate and decorated

with engravings and sometimes with paint (Fig.10). Their manufacture was

professional, and was concentrated into specific "workshops" in the interior

Alentejo region, from where they spread towards the coast and to the

Andalusia in Southern Spain, with which the Alentejo region already had

strong cultural connections (Calado 2010). I’ll discuss the slate plaques more

detailedly in chapter 3, which deals with the art in the megalithic tombs.

A rare, but interesting group of artefacts are bâculos de xisto (schist crusiers)

(Fig. 11.) Some dozens of them have been found, exclusively in Portugal, in

megalithic burial context. They are decorated in the same style than the

schist plaques. Their purpose and significance is unknown, but similar kind of

objects has been found pictured engraved in some menhirs and in other rock

art context, and as decoration motive on ceramics. (Gonçalves 2011.) In the

tombs the bâculos are placed near the headstone of the dolmen, which is

29

considered to have a special significance (Museu de Évora 2014).

Fig.9. Bone rabbit/hare figures from various megalithic burials. Source: Leisner, G. &

Leisner, V. 1951[1985]:151. 1-3 Cova da Moura; 4,5 and 15-17 Cabeço da Arruda; 6

and 7 Anta Grande do Olival da Pega; 8,13 and 14 caves in Cascais; 9 Gruta da

Carrasca; 12 Anta Grande da Comenda da Igreja; 18 Portalegre; 19 Gruta da

Galinha; 20 Elvas region.

In Late Neolithic Period into the megalithic graves in the coastal area

appeared lime stone idols (Fig.12.) and mortars, which are related to the

Mediterranean cultural influences. The mortars were used to grind red ochre.

(Gonçalves 2006:53.) The limestone idols were arranged in the graves so

that they formed an equilateral cross on the bottom of the tomb. The

appearing of the lime stone idols is probably connected to the emerging

Chalcolithic period and to the international metal processing and trading

centers starting to evolve on the coastal area. (Gonçalves 2006:505-507.)

Simultaneously, for the first time, the fortificated habitations appeared into the

Portuguese landscape. They may be a sign telling that the hierarchisation of

the society had begun. (Gonçalves 1989:299.)

30

Fig.10. Slate plaques, Granja de Céspedes. Source: Heitlinger 2007.http://arqueo.org/index.html

Fig. 11. Chist crusier from dolmen Anta 4. Da Herdade das Antas, Montemor-o-Novo. Photo: Museu Nacional de Arqueologia 2014. Artefact No: 989.29.1www.Museuarqueologia.pt

31

Fig. 12. Chalcolithic idols from megalithic burials in collections of MuseuArchaeológico do Carmo. Photo by author 2010.

2.5.2 Burials in the megalithic graves in the Chalcolithic period(approximately 3000 -1800 BCE) and reburials in the Bronze and IronAges

During the Chalcolithic period the burials in the Portuguese megalithic graves

turned towards the direction of individual burials – instead of mixing the

bones of the deceased, the bones of each individual were now stacked onto

separate piles. It is thought that the cult of the ancestors would have been

growing at this time, as well as its harnessing to serve the justification of the

rising ideology of private landowning. (Goméz et al. 2008.)

The schist plaques were situated under each skull (while earlier they were

mixed amongst other grave goods and bones). Novelties amongst the grave

goods were copper arrowheads and bellbeaker vessels. Starting from the

final part of the Chalcolithic period, approximately 1800 BCE, the skeletons

were not anymore dismantled. The grave goods were given individually for

each deceased. For example in the dolmen number 1 of Poço da Gateira,

near Évora, the dead were placed to rest in a half-sitting position, leaning

against the walls of the dolmen. All the corpses in the dolmen had still

received equal treatment and equal grave goods – a polished axe and a

32

polished chisel. (Gonçalves 2006.) However, in some Chalcolithic tombs we

can see signs of different treatment of the corpses deposited in them (Castro

et al. 2009:49-57).

Inside some dolmens were built slate coffins, and the corpses positioned into

the coffins got more grave goods than the corpses placed outside them. At

the same time the internal hierarchy of the tombs began to take shape – the

corpses with biggest amount of grave goods were placed in middle of the

burial chamber and as near as possible to the big headstone opposite the

entrance of the dolmen, which seems to have carried a special importance.

The deceased who received less gifts were positioned on the peripheries of

the burial chamber. (García-Martinez de Lagran et al. 2010:257.)

Possibly in response to the march of the hierarchisation the bones and grave

goods in some megalithic graves were subsequently mixed with each other

and the slate coffins were eradicated, and the grave thus ”democratized”.

Similar interpretation has been made about so called ”lime-kiln tombs”.

(García-Martinez de Lagran et al. 2010:272.) Lime-kiln tombs were tholos

tombs built of limestone, which were intently demolished by fire after few

generation´s use. A wind shelter was built on top of the tholos to enable the

burning, and the fire was maintained for days, until the limestone

constructions were melted, according to the results of experimental

archaeology. 3 Water was poured over the melted limestone, in consequence

of which a hard, about half a meter thick lime-cement layer was formed. The

residual remnants of the wall constructions were scattered. Archaeological

studies found out that the past generations had built slate coffins inside the

3 In the archaeological experiment 1999 a replica of the La Peña de la Abuela tomb in Ambrona (Soria, Spain)was built and fired. “Once the replica was finished it was surrounded by a wooden screen and covered by heatherand mud, as was found in the La Peña de La Abuela excavation, which would protect the combustion from thewind.. ..During the firing it was necessary to restock with a considerable amount of quick lighting dry fuel as hasbeen widely recorded in the local traditional ‘lime-kilns’” The amount needed proved to be 20 tons. “After 35 hoursof experimental firing, only the top of the structure had been transformed into quicklime (CaO), whereas in the restof the replica, only a thin layer was sufficiently dehydrated to form quicklime. It is important to note that thethickness of the replica walls (70 cm) would have required a much more prolonged fire (perhaps two more days andnights) to melt the whole structure.. ..To obtain 2000–3000 kg of quicklime, a minimum of ten hours of continuousand intense fire was required. This clearly shows that the large quantity of quicklime found in La Peña (4 m3) or ElMiradero (10 m3) is impossible to produce accidentally and obviously reflects a deliberate and complex behaviour.”(Garcia-Martinez de Lagran et al. (2010:271-272)

33

tholos tombs. The corpses buried inside the coffins were all male, and they

had been given more grave goods than the female corpses buried outside

the coffins. The burning of the tombs and concealing all their contents inside

a lime shell has been interpreted as an effort to restore equality among the

dead. After the ”democratization” a similar tholos tomb was built over one of

the burned tombs, and in it the burials continued in the traditional, more equal

manner. Over the other burned graves were piled stone heaps, and on top of

one was erected a menhir. ”Lime-kiln tombs” have been thus far found few in

Portugal, Spain and France. (García-Martinez de Lagran et al. 2010.)

On the early Bronze Age (1800 – 1500 calBC) the burials changed to

individual burials. The deceased was put into a stone coffin, which was

surrounded by a stone circle, over which was erected a mound. The Bronze

Age barrows are often located next to or on top of the Neolithic grave

mounds. The megalithic graves were also often reused. Reuse was common

throughout Europe. For example a study made on the Mecklenburg-

Vorpommern area in Germany has shown that of the 144 megalithic graves

in the area one third was in reuse, if only the internal use of the burial

chamber is taken into account, and 50 per cent, if the outside ritual activity

closely connected to them is taken into account as well. About 30 per cent of

the reburials were made in the Pre-Roman Iron Age (Holtorf 2000) and it was

still rather common throughout the Roman era (Goméz et al. 2007). The

studies made in Northern France and in UK indicate continuous reuse of

megalithic burial sites in Bronze Age, Middle Iron Age and even in the

mediaeval period (Sanjuán 2005:601-603). Thus, the secondary use of

megalithic tombs cannot be considered a marginal phenomenon.

During the Middle Bronze Age (1500 -1000 calBC) the reuse of Neolithic

graves accelerated (Mataloto 2007:130), and at the same time into the

villages and homes appeared shrines apparently dedicated to the cult of the

ancestors – artificial podiums on which were brought Neolithic schist plaques

from the graves, and in two cases also bellbeaker vessels from the

Chalcolithic period. It is possible that also the reuse of the megalithic graves

in the Bronze Age had to do with the ancestor´s cult. (Mataloto 2007:131-

34

132.)

In Bronze Age it was common to resettle earlier settlements or turn them into

burial sites. There is also evidence about attempts to mimic the artefacts of

earlier periods, for example the ceramic bowls imitating the female breast

have been made in the same settlement sites both in the end of the fourth

millennium and in the Bronze Age. (Sanjuán 2005:597.) The use of

megalithic graves continued also in Iron Age. Funeral urns were deposited

into them. Urns were deposited for example into the Dolmen of Tera near the

town of Mora as late as during the 5th and 6th centuries ACE. In the context

of the urn burials has been found Venus and Matres figures, which are

connected to the fertility cult. (Gómez et al. 2007:123.)

3.Theartofmegalithictombs

3.1 Paintings and drawings in the tombs.

The painted and engraved art of the Iberian megalithic graves represents the

same technique and style than the Neolithic schematic rock art in the open

rock art sites (Balbín Behrmann & Bueno Ramirez 2003). (Fig. 13.)The rock

art was mainly done in rock shelters, connected to river crossings, along the

waterways and engraved in stones, which are thought to have marked the

grazing land borders or the locations of settlements and water sources

(Rocha 2004). The engravings on the menhirs are also part of the same art

tradition, as well as the decorated schist plaques and other mobile art (Balbín

Behrmann & Bueno Ramirez 2006). The art sites form a network into the

landscape, and fills it with meanings, which can be identified and understood

even by a stranger wandering thither (Rocha 2004).

It is remarkable that the majority of decorated dolmens in Portugal are in the

Central and Northern part of the country, while the decorated schist plaques

fill the dolmens in the South. It seems that the permanent art in the North and

the mobile art in the South played similar role in the burial context. (Rocha

2004.) The division is not totally exclusive – there is some decorated

35

dolmens in Southern Portugal and some schist plaques found in Northern

Portugal. (Map 3.) Since the 1980´s many more decorated megalith tombs

have been found in Southern Portugal too (Sanches 2006).

Fig. 13. The head stone of Dolmen de Areita, Viseu – the same schematic style thanin contemporaneous rock art. Source: Carvalho et al. 1998:66.

36

Map 3. Megalithic art in Iberia.Besides megalith tombs the map covers decoratedmenhirs and cromlechs. White dots mark the sites known in 1981, black dots marksites found between 1981 and 2003. Source: Balbín Behrmann & Bueno Ramirez2003.

Many scientists (e.g. Balbín Behrmann et al. 2000, Cruz 1995, Jorge 1995,

O´Sullivan 2002) divide Neolithic art into the art of public space and into the

secret art of the graves. The motifs of the art in the megalithic monuments

differ from the motifs of the art of the public space mainly by there being

more anthropomorphic symbols amongst them. The painting and drawing

techniques has been used in Iberia supporting each other, both in the graves

and in other art sites. The art of the graves is polychrome (fig. 14.) – the

colors are red, white and black, while the open air art is monochrome – the

only color being red. The schist plaques and other idols in the graves also

represent the same art tradition, and they should be seen as part of it.

(Balbín Behrmann & Bueno Ramirez 2003.)

37

Fig. 14. Polychrome art in dolmen Anta de Antelas. On the left twoanthropomorphic figures and on right the sun between ziguezague lines. Source:Laranjeira 2013. http://antelas-omeulugar.blogspot.pt/2013/01/dolmen-pintado-de-antelas.html

Regardless of the size of the megalithic grave, it is the so called headstone,

opposite the entrance (often the largest orthostat), and the orthostats next to

it, on which majority of the art is located. (Fig.15.) Art is often also lining the

entrances, through which people (or deceased) are moving from one space

into another. (Behrmann et al. 2006.) There is also often art in the so called

threshold stones, which don´t have any structural role in the dolmens, but

which are thought to serve as space dividers, by stepping over which a

person moves from one space into another – from profane to sacred and

even holier (O´Sullivan 2002).

38

Fig. 15. The decorated orthostats of the dolmen 2. In Portela do pau. Source:

Sanches 2006.

According to the radiocarbon datings of the pigments, the art in the

megalithic graves is from the same period than the megaliths themselves,

and so they should be seen as a part of the architectural whole. They have

been already part of the design of the dolmen. (Balbín Behrmann & Bueno

Ramirez 2000:287-289.) For example in the dolmens of Dombate and Pedra

Cuberta in Galicia, Spain, the entire inner surface of the burial chamber has

been first painted with white colour, over which has been painted

representative art with red (Jorge 1998).

In some cases some symbols have been repaired or altered during the later

use of the dolmens. For example in the dolmen of Antelas (Oliveira de

Frades) has been recognized two different shades of red colour, but in spite

of this, ”archaeological data points to an individualized iconographic and

architectonic programme for each dolmen”. (Sanches 2006:129.)

39

3.2 Symbols in the art of the megalith tombs

Art in the megalithic graves follows a particular set of norms, be it in a

dolmen, tholos tomb, cave or artificial cave in whatever part of Portugal,

maybe in whole Iberia or even in the whole vast area of the European

megalithic culture – the same motifs are present, and their positioning inside

the graves is similar. The central motifs of the megalithic art are:

anthropomorphic symbols, symbols probably representing sun, snake and

horned animals, weapons and geometric figures – triangles, quadrangles,

rhombs, zigzag lines and circles. (Fig.16) The symbols are appearing in the

art in certain combinations, like anthropomorph with a snake or

anthropomorph with sun. Often the anthropomorph is combined with some

animal, which is commonly thought to symbolize fertility and rebirth – like

snake, hare or a horned animal, usually deer. (Fig. 17.) The same symbols

are central to the mythology of the entire Western farming culture for a long

time. (Balbín Behrmann et al. 2000:293.)

40

Fig. 16. On top: Drawings of details in dolmen Anta de Antelas (Rodrigues 1991).On bottom: Drawing of a detail in dolmen Anta de Antelas. Two anthropomorficfigures and a comb over the smaller figure. (Gonçalves 2004:12.)

The fact that there is pictures of deers, and also hunting scenes present in

the megalith tombs, which, one should imagine, would not have been very

central themes anymore in Neolithic culture, tells, according to Balbín

Behrmann & Bueno Ramirez (2006b), that the artists were picturing the life of

mythical ancestors.

In studies made about the visibility of the symbols in the dolmens using

different artificial lightning, it has been noticed that some of the symbol

combinations seem to have been planned in a way that they seem to be

moving or dancing seen in the light of a torch (Sanches 2006:135). There is

evidence that large part of the megalithic graves in Iberia, which today are

undecorated, were once decorated. If the capstone of the dolmen is

removed, erosion eats the paintings and more delicate engravings from the

orthostats in few years. For example the dolmen Mamoa 2 do Alto da Portela

do Pau in the Northern Portugal is the only one in the group of five dolmens,

which has its capstone unremoved, and also the only one with art inside – six

of its seven orthostats are painted. It is very probable that there has been art

also in the other dolmens of the group. In some cases traces of the

decorations are only left in the basal parts of the ortostaths, where the

deposition of sediments has been conserving them. (Jorge 1998.)

41

Fig. 17. On the left: Horned animal, snake, and a possible mix of these two. .Engravings of dolmen de Aliviada, Portugal. (Silva 1984.)On the right: Deer or elk in dolmen de Châo Redondo, Portugal (Shee 1981).

The use of red ochre is widespread in all megalithic graves, but its volume

fluctuates greatly. In the cave of Lapa do Fumo in Sesimbra there is so much

red ochre that the cultural layer has been named according to it as ”Camada

vermelha” – Red layer. Also in some dolmens the whole burial chamber is

painted red. (Jorge 1998.)

The orthostats are sometimes divided vertically or horizontally into different

image fields either with straight or wavy lines. Sometimes the lines are

framing a picture. Most thus framed pictures are in the headstone, opposite

to the entrance of the dolmen. For example the headstone of the dolmen

Mamoa 2 do Alto da Portela do Pau is divided into horizontal areas with

groups of zigzag or wavy lines, which alternate with the unengraved zones.

The impression is very similar than the decorations in the schist plaques in

the Southern Portugal. This raises the question whether the headstones of

Northern Portugal decorated in this style share the same ideological meaning

with the schist plaques found in the megalithic graves in the South. Similarly

decorated headstones are found for example in the dolmen Rapido 3

(Esposende, Portugal), in the dolmen Forno dos Mouros (Coruña, Galicia)

and in the dolmen Castaneira 2 (Pontevedra, Galicia). (Jorge

1998:74.)(Fig.18.)

42

Fig.18. On the left: orthostat in Dolmen de Santa Cruz (Bueno Ramirez 2010).http://www.man.es/man/dms/man/estudio/publicaciones/conferencias-congresos/MAN-2009-Ojos-cierran/MAN-Con-2009-Ojos-cierran.pdfOn the right: The headstone of Dolmen 2 de Chão Redondo, Sever do VougaSource: Castela 2013. http://www.portugalnotavel.com/

Sometimes on the dolmen headstone is pictured a human-animal hybrid, and

sometimes a ”hieratic” figure, who is holding hands, as if protectively, over

smaller anthropomorphic figures. There is something projecting from the

figure, which may represent the rays of light, or possibly a skirt. (Jorge

1998:76.) The left hand side of the dolmens (watched from the entrance) is

always more decorated than the right hand side, and majority of the

anthropomorphic and zoomorphic images are also located there (Jorge

1998:73). It is possible that the left side of the dolmen was esteemed as

”holier” than the right hand side. The sun symbols, instead, are located on

the right side, which may be explained by the fact that the majority of the

Iberian dolmens are oriented towards east, and the sun shining through the

entrance of the dolmen has illuminated the right side, that is the north side of

the dolmen, for a longer duration. (Jorge 1998:77.)

43