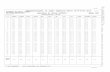

B1 Educational Expenditure Relative to Gross Domestic Product © OECD 2000 56 Table B1.1 c . Educational expenditure as a percentage of GDP for tertiary education, by source of funds (1997) Financial aid Private payments Total expenditure Public to students not to educational from public, private subsidies Total expenditure attributable Direct public institutions and international Private payments to households and from both public to household expenditure for excluding public sources for other than other private and private sources payments educational subsidies educational to educational entities excluding for educational to educational institutions to households and institutions plus institutions public subsidies for institutions institutions for other private public subsidies to student living costs educational entities households services OECD countries Australia 1.0 0.18 0.53 1.7 1.9 0.2 0.19 Austria 1.3 0.03 0.17 1.5 1.7 m 0.20 Belgium (Fl.) 0.8 0.04 0.10 0.9 1.2 m 0.22 Canada 1.2 0.45 0.35 2.0 2.2 0.4 0.19 Czech Republic 0.7 n 0.11 0.8 0.9 m 0.07 Denmark 1.1 n 0.01 1.2 1.8 0.6 0.63 Finland 1.7 0.02 x 1.7 2.0 m 0.35 France 1.0 0.03 0.14 1.2 1.2 0.1 0.06 Germany 1.0 n 0.08 1.1 1.2 0.1 0.13 Greece 1.0 m 0.18 1.2 1.2 m m Hungary 0.8 0.04 0.22 1.0 1.1 m 0.08 Iceland 0.7 x 0.04 0.7 1.0 m 0.25 Ireland 1.0 0.09 0.29 1.4 1.7 m 0.28 Italy 0.6 0.05 0.15 0.8 0.9 0.4 0.05 Japan 0.5 m 0.58 1.1 m m m Korea 0.5 m 1.95 2.5 2.5 m n Luxembourg 0.1 n m m m m 0.09 Mexico 0.8 n 0.27 1.1 1.2 n 0.07 Netherlands 1.1 0.12 0.03 1.2 1.5 0.3 0.25 New Zealand 1.0 x m m m m 0.80 Norway 1.3 x 0.09 1.4 2.1 n 0.74 Poland 1.2 m m m m m 0.05 Portugal 1.0 a 0.02 1.0 1.1 n 0.05 Spain 0.9 0.03 0.27 1.2 1.3 0.1 0.06 Sweden 1.6 n 0.16 1.7 2.4 m 0.62 Switzerland 1.1 0.01 n 1.1 1.2 n 0.04 Turkey 0.8 m m m m m m United Kingdom 0.7 0.16 0.12 1.0 1.3 m 0.25 United States 1 1.4 m 1.29 2.7 2.9 0.1 m Country mean 1.0 0.06 0.31 1.3 1.5 0.2 0.23 OECD total 1.0 0.08 0.70 1.7 2.0 0.1 0.14 WEI participants Argentina 0.8 n 0.29 1.0 1.1 n n Brazil 2 0.8 m m m m m m Chile 0.4 0.12 1.24 1.8 1.8 m 0.02 Israel 3 1.2 0.05 0.77 2.0 2.0 n n Malaysia 1.1 n 0.28 1.4 1.6 n 0.27 Paraguay 0.7 a m m m n a Philippines 0.5 0.01 0.93 1.4 1.4 0.4 a Thailand 1.0 m m m m m m Uruguay 0.6 a m m m a a Zimbabwe 1.5 n n 1.5 1.7 n 0.19 . Includes post-secondary non-tertiary data. . 1996 data. . 1995 data. ource: OECD Education Database. See Annex 3 for notes.

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

B1 Educational Expenditure Relative to Gross Domestic Product

© OECD 200

5

Table B1.1c. Educational expenditure as a percentage of GDP for tertiary education,by source of funds (1997)

Financial aidPrivate paym ents Total expenditure

Public to students notto educational from public, private

subsidies Total expenditure attributableDirect public institutions and international Private paym ents

to households and from both public to householdexpenditure for excluding public sources for other than

other private and private sources paym entseducational subsidies educational to educational

entities excluding for educational to educationalinstitutions to households and institutions plus institutions

public subsidies for institutions institutions forother private public subsidies to

student living costs educationalentities households

services

OECD countriesAustralia 1.0 0.18 0.53 1.7 1.9 0.2 0.19Austria 1.3 0.03 0.17 1.5 1.7 m 0.20Belgium (Fl.) 0.8 0.04 0.10 0.9 1.2 m 0.22Canada 1.2 0.45 0.35 2.0 2.2 0.4 0.19Czech Republic 0.7 n 0.11 0.8 0.9 m 0.07Denm ark 1.1 n 0.01 1.2 1.8 0.6 0.63Finland 1.7 0.02 x 1.7 2.0 m 0.35France 1.0 0.03 0.14 1.2 1.2 0.1 0.06Germ any 1.0 n 0.08 1.1 1.2 0.1 0.13Greece 1.0 m 0.18 1.2 1.2 m mHungary 0.8 0.04 0.22 1.0 1.1 m 0.08Iceland 0.7 x 0.04 0.7 1.0 m 0.25Ireland 1.0 0.09 0.29 1.4 1.7 m 0.28Italy 0.6 0.05 0.15 0.8 0.9 0.4 0.05Japan 0.5 m 0.58 1.1 m m mKorea 0.5 m 1.95 2.5 2.5 m nLuxem bourg 0.1 n m m m m 0.09M exico 0.8 n 0.27 1.1 1.2 n 0.07Netherlands 1.1 0.12 0.03 1.2 1.5 0.3 0.25New Zealand 1.0 x m m m m 0.80Norway 1.3 x 0.09 1.4 2.1 n 0.74Poland 1.2 m m m m m 0.05Portugal 1.0 a 0.02 1.0 1.1 n 0.05Spain 0.9 0.03 0.27 1.2 1.3 0.1 0.06Sweden 1.6 n 0.16 1.7 2.4 m 0.62Switzerland 1.1 0.01 n 1.1 1.2 n 0.04Turkey 0.8 m m m m m mUnited Kingdom 0.7 0.16 0.12 1.0 1.3 m 0.25United States 1 1.4 m 1.29 2.7 2.9 0.1 m

Country mean 1.0 0.06 0.31 1.3 1.5 0.2 0.23OECD total 1.0 0.08 0.70 1.7 2.0 0.1 0.14

WEI participantsArgentina 0.8 n 0.29 1.0 1.1 n nBrazil 2 0.8 m m m m m mChile 0.4 0.12 1.24 1.8 1.8 m 0.02Israel 3 1.2 0.05 0.77 2.0 2.0 n nM alaysia 1.1 n 0.28 1.4 1.6 n 0.27Paraguay 0.7 a m m m n aPhilippines 0.5 0.01 0.93 1.4 1.4 0.4 aThailand 1.0 m m m m m mUruguay 0.6 a m m m a aZim babwe 1.5 n n 1.5 1.7 n 0.19

. Includes post-secondary non-tertiary data.

. 1996 data.

. 1995 data.ource: OECD Education Database. See Annex 3 for notes.

0

6

ANNEX 3

© OECD 200

33

Table 2. Standardised presentation of national ISCED-97 mappings

Post-Pre-prim ary Lower Tertiary- Tertiary- Advanced

secondaryand prim ary secondary Upper secondary education type B type A research

non-tertiaryeducation education education education program m es

education

ISCED 3C ISCED 3CISCED 0/1 ISCED 2 ISCED 3B ISCED 3A ISCED 4 ISCED 5B ISCED 5A ISCED 6

Short Long

ustralia 0/1/2, 2B/2C 3B 3A, 3A/4 5B 5A 5A/6ustria 0/1/2 3B 3A 4A 5B 5A/6elgium 1 2 3CL/4 3A 5B 5A 5A/6anada 0/1/2, 2 3 4 4/5B 5A 5A/6zech Republic 0/1 2 3CL 3A, 3A/4 5A/6enm ark 1 2 3C/4C 3B/4B 3A/4A 5B 5A 6inland 0/1 2 3A 5B 5A 6rance 0, 1 2A, 2B 3CS 3CL 3B 3A 4A, 4 5B, 5AI 5A 5A/6erm any 1 2A 3B 3A 4 5B 5Areece 0/1 2 3C 3B 3A 4C 5B 5A 6ungary 0/1 2 3C, 3C/4B 3A 5A 5A/6

celand 0/1 2A, 2C 3CS 3A 4C 5B 5A 6reland 0/1 2 3A/4 5B/4 5A/6taly 0/1 2 3CS 3CL 3A/3B 4C 5A/5B 6apan 0/1/2 3A/3C 5B 5A/6orea 0/1 2 3A/3C 5B 5A/6exico 0, 1 2, 2/3A 3CL 5B 5A/6etherlands 1 2 3A/3C 4/5B/5A, 5Aew Zealand 0, 1 3CL 3A 4C 5B 5A 5A/6orway 0, 1 2A 3C 3A 4C 5B 5A 6oland 1/2 3CS 3A 4B 5B/5A/6ortugal 1 2 3/4 5B 5A 6pain 0/1, 1 2 3CS 3B 3A 4B 4C/5B, 5B 5A 6weden 1 2 3A, 3 4/5B 5A 5A/6witzerland 0/1 2A 3CL 3B/4B 3A/4A 5B 5A/6urkey 0, 1 2 3B 3A 5A/6nited Kingdom 2 3CS 3CL 3A 5B 5A 6nited States 0/1 2 3 5B, 5AI 5A 6

ote: ISCED 5AI: Tertiary-type A, interm ediate degree.

0

0

© OECD 2000

83

BB4

EDUCATIONAL EXPENDITURE PER STUDENT

• Educational expenditure per student at the primary and secondary levels increased in mostcountries between 1990 and 1996, even though enrolment increased in many of them at thesame time.

• At the tertiary level, expenditure per student decreased in eight out of 14 countries, largely asa result of large increases in enrolment.

• There is a positive relationship between spending per student and per capita GDP, poorercountries spending relatively less per student than richer countries.

• In some countries, low annual expenditure translate into high overall costs of tertiary educationbecause of the long duration of the tertiary programme.

200

180

160

140

120

100

80

60

40

200

180

160

140

120

100

80

60

40

268

Expenditure on institutions

Chart B4.1. Index of changes in spending on education, enrolment, and expenditureper student for tertiary education between 1990 and 1996 (1990 = 100)

Enrolment Expenditure per student

1. Public institutions only.

Countries are ranked in ascending order of total expenditure on institutions.

Source: OECD Education Database.

Italy

Switzer

land1

Nethe

rland

s

Canad

a

Mex

ico

Finlan

d

Austri

a1

Franc

e

Norway

Spain1

Austra

lia

United

King

dom

Portu

gal

Irelan

d

200

180

160

140

120

100

80

60

40

200

180

160

140

120

100

80

60

40

268

Expenditure on institutions

Chart B4.1. Index of changes in spending on education, enrolment, and expenditureper student for tertiary education between 1990 and 1996 (1990 = 100)

Enrolment Expenditure per student

1. Public institutions only.

Countries are ranked in ascending order of total expenditure on institutions.

Source: OECD Education Database.

Italy

Switzer

land1

Nethe

rland

s

Canad

a

Mex

ico

Finlan

d

Austri

a1

Franc

e

Norway

Spain1

Austra

lia

United

King

dom

Portu

gal

Irelan

d

200

180

160

140

120

100

80

60

40

200

180

160

140

120

100

80

60

40

268

Expenditure on institutions

Chart B4.1. Index of changes in spending on education, enrolment, and expenditureper student for tertiary education between 1990 and 1996 (1990 = 100)

Enrolment Expenditure per student

1. Public institutions only.

Countries are ranked in ascending order of total expenditure on institutions.

Source: OECD Education Database.

Italy

Switzer

land1

Nethe

rland

s

Canad

a

Mex

ico

Finlan

d

Austri

a1

Franc

e

Norway

Spain1

Austra

lia

United

King

dom

Portu

gal

Irelan

d

Chart B4.1. Index of changes in spending on education, enrolment, and expenditure per student for tertiary education between 1990 and 1996 (1990 = 100)

Overall Participation in Education

© OECD 2000

125

CC1

Chart C1.2. Net enrolment rates by single year of age and level of education(head counts, 1998)

Pre-primary Lower secondary Post-secondary non-tertiary Tertiary-type A andadvanced research programmes

Primary Upper secondary Tertiary-type B

Australia Austria

Finland

Czech Republic Denmark

Belgium (Flemish Community) Canada

Germany1 Greece

France

% %100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

% %

% %

% %

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654 3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654 3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654 3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

03 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654 3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

3 28272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

% %

Chart C1.2. Net enrolment rates by single year of age and level of education(head counts, 1998)

Pre-primary Lower secondary Post-secondary non-tertiary Tertiary-type A andadvanced research programmes

Primary Upper secondary Tertiary-type B

Australia Austria

Finland

Czech Republic Denmark

Belgium (Flemish Community) Canada

Germany1 Greece

France

% %100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

% %

% %

% %

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654 3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654 3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654 3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

03 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654 3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

3 28272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

% %

Chart C1.2. Net enrolment rates by single year of age and level of education(head counts, 1998)

Pre-primary Lower secondary Post-secondary non-tertiary Tertiary-type A andadvanced research programmes

Primary Upper secondary Tertiary-type B

Australia Austria

Finland

Czech Republic Denmark

Belgium (Flemish Community) Canada

Germany1 Greece

France

% %100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

% %

% %

% %

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654 3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654 3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654 3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

03 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654 3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

3 28272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

% %

C1 Overall Participation in Education

© OECD 2000

126

Chart C1.2. Net enrolment rates by single year of age and level of education(head counts, 1998) (cont.)

Pre-primary Lower secondary Post-secondary non-tertiary Tertiary-type A andadvanced research programmes

Primary Upper secondary Tertiary-type B

Hungary2 Iceland

Netherlands

Korea Mexico3

Ireland3 Italy1

Norway Poland

New Zealand

% %100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

% %

% %

% %

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654 3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654 3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654 3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

03 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654 3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

% %

Chart C1.2. Net enrolment rates by single year of age and level of education(head counts, 1998) (cont.)

Pre-primary Lower secondary Post-secondary non-tertiary Tertiary-type A andadvanced research programmes

Primary Upper secondary Tertiary-type B

Hungary2 Iceland

Netherlands

Korea Mexico3

Ireland3 Italy1

Norway Poland

New Zealand

% %100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

% %

% %

% %

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654 3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654 3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654 3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

03 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654 3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

% %

Chart C1.2. Net enrolment rates by single year of age and level of education(head counts, 1998) (cont.)

Pre-primary Lower secondary Post-secondary non-tertiary Tertiary-type A andadvanced research programmes

Primary Upper secondary Tertiary-type B

Hungary2 Iceland

Netherlands

Korea Mexico3

Ireland3 Italy1

Norway Poland

New Zealand

% %100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

% %

% %

% %

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654 3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654 3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654 3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

03 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654 3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

% %

Overall Participation in Education

© OECD 2000

127

CC1

1. Italy and Germany: Data are missing for advanced research programmes.2. Hungary: Data are missing for tertiary-type B programmes.3. Ireland, Sweden and Mexico: Tertiary-type A and advanced research programmes include data for tertiary-type B programmes.Source: OECD.

Chart C1.2. Net enrolment rates by single year of age and level of education(head counts, 1998) (cont.)

Pre-primary Lower secondary Post-secondary non-tertiary Tertiary-type A andadvanced research programmes

Primary Upper secondary Tertiary-type B

Portugal Spain

United States

Turkey United Kingdom

Sweden3 Switzerland

% %100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

% %

% %

% %

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654 3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654 3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654 3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

1. Italy and Germany: Data are missing for advanced research programmes.2. Hungary: Data are missing for tertiary-type B programmes.3. Ireland, Sweden and Mexico: Tertiary-type A and advanced research programmes include data for tertiary-type B programmes.Source: OECD.

Chart C1.2. Net enrolment rates by single year of age and level of education(head counts, 1998) (cont.)

Pre-primary Lower secondary Post-secondary non-tertiary Tertiary-type A andadvanced research programmes

Primary Upper secondary Tertiary-type B

Portugal Spain

United States

Turkey United Kingdom

Sweden3 Switzerland

% %100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

% %

% %

% %

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654 3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654 3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654 3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

1. Italy and Germany: Data are missing for advanced research programmes.2. Hungary: Data are missing for tertiary-type B programmes.3. Ireland, Sweden and Mexico: Tertiary-type A and advanced research programmes include data for tertiary-type B programmes.Source: OECD.

Chart C1.2. Net enrolment rates by single year of age and level of education(head counts, 1998) (cont.)

Pre-primary Lower secondary Post-secondary non-tertiary Tertiary-type A andadvanced research programmes

Primary Upper secondary Tertiary-type B

Portugal Spain

United States

Turkey United Kingdom

Sweden3 Switzerland

% %100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

% %

% %

% %

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654 3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654 3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654 3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

3 2928272625242322212019181716151413121110987654

C1 Overall Participation in Education

© OECD 2000

130

they are theory-based and designed to prepare students to enter advancedresearch programmes or professions with high skill requirements (tertiary-type A), or tend to focus on occupationally-specific skills intended for directlabour market entry (tertiary-type B). While the institutional location ofprogrammes used to give a relatively clear idea of their nature (e.g., universi-ties versus non-university status), these distinctions have become blurred.

Upper secondary completers in a number of systems also have the optionof taking relatively short programmes (less than two years) to prepare them toenter trades or specific vocational fields. While these programmes are offeredas advanced or second cycle upper secondary programmes in some countries(e.g. Austria, Germany and Spain), they are offered in the post-secondary sectorin others (e.g., Canada and the United States). From an internationallycomparative point of view, these programmes straddle the boundary betweenupper secondary and tertiary education. In 22 out of 27 countries programmesof this nature are offered to upper secondary completers. In Austria, Canada, theCzech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Ireland and Spain over 9 per cent of 18 and19 year-olds are enrolled in such post-secondary non-tertiary programmes(ISCED 4).

The transition from secondary education to post-secondary educationoccurs at different ages in different countries (Charts C1.2 and C1.3). At the ageof 17 secondary students still form more than 90 per cent of the total enrolmentin all but three countries: only in Austria, Ireland and Turkey do we see morethan 10 per cent of enrolment at the age of 17 at the post-secondary level.

By the age of 19,the majority of students

in more than halfof the OECD countries

are enrolled at thepost-secondary level.

By the age of 19, the majority of students in more than half of the OECDcountries are in post-secondary education and by the age of 20, only inDenmark, Iceland, Sweden and Switzerland are more students still insecondary than in post-secondary education (Table C1.3). In many countries,the transition to tertiary-level education continues up to the age of 25 andover (Table C1.2).

Participation in tertiary education

On average in OECDcountries, a 17-year-old

can expect to attend2.3 years of tertiary

education.

On average in OECD countries, a 17-year-old can expect to attend 2.3 yearsof tertiary education over his or her lifetime. Both tertiary entry rates and thetypical duration of study affect the expectancy of tertiary education. In Australia,Finland, Korea and the United States this value exceeds three years. In theCzech Republic, Hungary, Mexico, Turkey and Switzerland, by contrast, theexpectancy of tertiary education is 1.6 years or less (see Table C1.1 andIndicators C3 and C4).

Policies of expandingyouth education have,

in many countries,increased pressurefor greater access

to tertiary education.

Policies of expanding youth education policies have, in many countries,increased pressure for greater access to tertiary education. Thus far, thispressure has more than compensated for declines in cohort sizes which untilrecently led to predictions of stable or declining demand from school leaversin several countries, including Australia and Japan. In some countries, there arenow signs of a levelling off in the demand for tertiary education, but the overalltrend remains upward.

Overall Participation in Education

© OECD 2000

131

CC1

% %100

% %

% %

% %

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

BEL (Fl.)

SWE

NORDEU

FINFRA

CHENLD

DNKPOL

GRCIR

LIT

AAUT

ISL

AUSESP

PRTCZE

USAHUN

NZLKOR

CANUKM

MEX

TUR

BEL (Fl.)

SWE

NORDEU

FINFRA

CHENLD

DNKPOL

GRCIR

LIT

AAUT

ISL

AUSESP

PRTCZE

USAHUN

NZLKOR

CANUKM

MEX

TUR

BEL (Fl.)

SWE

NORDEU

FINFRA

CHENLD

DNKPOL

GRCIR

LIT

AAUT

ISL

AUSESP

PRTCZE

USAHUN

NZLKOR

CANUKM

MEX

TUR

BEL (Fl.)

SWE

NORDEU

FINFRA

CHENLD

DNKPOL

GRCIR

LIT

AAUT

ISL

AUSESP

PRTCZE

USAHUN

NZLKOR

CANUKM

MEX

TUR

Chart C1.3. Transition characteristics at each year of age from 17 to 20:Net enrolment by level of education, based on head counts (1998)

Age 17

Countries are ranked in descending order of net enrolment rates at 18 years of age.

Source: OECD.

Age 18

Age 19

Age 20

Tertiary educationPost-secondary non-tertiarySecondary education

% %100

% %

% %

% %

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

BEL (Fl.)

SWE

NORDEU

FINFRA

CHENLD

DNKPOL

GRCIR

LIT

AAUT

ISL

AUSESP

PRTCZE

USAHUN

NZLKOR

CANUKM

MEX

TUR

BEL (Fl.)

SWE

NORDEU

FINFRA

CHENLD

DNKPOL

GRCIR

LIT

AAUT

ISL

AUSESP

PRTCZE

USAHUN

NZLKOR

CANUKM

MEX

TUR

BEL (Fl.)

SWE

NORDEU

FINFRA

CHENLD

DNKPOL

GRCIR

LIT

AAUT

ISL

AUSESP

PRTCZE

USAHUN

NZLKOR

CANUKM

MEX

TUR

BEL (Fl.)

SWE

NORDEU

FINFRA

CHENLD

DNKPOL

GRCIR

LIT

AAUT

ISL

AUSESP

PRTCZE

USAHUN

NZLKOR

CANUKM

MEX

TUR

Chart C1.3. Transition characteristics at each year of age from 17 to 20:Net enrolment by level of education, based on head counts (1998)

Age 17

Countries are ranked in descending order of net enrolment rates at 18 years of age.

Source: OECD.

Age 18

Age 19

Age 20

Tertiary educationPost-secondary non-tertiarySecondary education

% %100

% %

% %

% %

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

BEL (Fl.)

SWE

NORDEU

FINFRA

CHENLD

DNKPOL

GRCIR

LIT

AAUT

ISL

AUSESP

PRTCZE

USAHUN

NZLKOR

CANUKM

MEX

TUR

BEL (Fl.)

SWE

NORDEU

FINFRA

CHENLD

DNKPOL

GRCIR

LIT

AAUT

ISL

AUSESP

PRTCZE

USAHUN

NZLKOR

CANUKM

MEX

TUR

BEL (Fl.)

SWE

NORDEU

FINFRA

CHENLD

DNKPOL

GRCIR

LIT

AAUT

ISL

AUSESP

PRTCZE

USAHUN

NZLKOR

CANUKM

MEX

TUR

BEL (Fl.)

SWE

NORDEU

FINFRA

CHENLD

DNKPOL

GRCIR

LIT

AAUT

ISL

AUSESP

PRTCZE

USAHUN

NZLKOR

CANUKM

MEX

TUR

Chart C1.3. Transition characteristics at each year of age from 17 to 20:Net enrolment by level of education, based on head counts (1998)

Age 17

Countries are ranked in descending order of net enrolment rates at 18 years of age.

Source: OECD.

Age 18

Age 19

Age 20

Tertiary educationPost-secondary non-tertiarySecondary education

C1 Overall Participation in Education

© OECD 2000

134

Table C1.1. School expectancy (in years) under current conditions1

1998 1990

Full-tim eFull-tim e and part-tim e Full-tim e Part-tim e and part-

tim e

Prim ary Post- All levels All levelsUpper All levels

All levels and lower secondary Tertiary of ofsecondary of education

of education com bined secondary non- education education educationeducation com bined

education tertiary com bined com bined

M +W M en W om en M +W M +W M +W

OECD countriesAustralia 20.0 m m 11.4 4.3 0.6 3.1 14.2 5.8 16.4Austria 16.0 16.2 15.9 8.2 3.7 0.5 2.2 15.8 0.2 14.3Belgium (Fl.) 17.3 17.0 17.7 8.6 4.8 0.5 2.4 15.4 1.9 mCanada 16.7 16.4 16.9 8.9 3.5 0.7 2.8 15.4 1.3 16.5Czech Republic 15.1 15.0 15.1 9.1 2.9 0.5 1.3 14.9 0.2 13.9Denm ark 17.5 17.1 17.9 9.8 3.3 0.1 2.4 17.5 n 16.1Finland 17.9 17.3 18.6 9.1 4.0 n 3.8 17.9 n 15.5France 16.6 16.4 16.8 9.5 3.3 n 2.6 16.6 n mGerm any 16.8 17.0 16.7 10.1 2.9 0.5 2.0 16.8 0.1 mGreece 15.5 15.4 15.6 9.0 2.8 0.5 2.4 15.4 0.2 mHungary 15.6 15.4 15.8 8.2 3.7 0.5 1.6 14.4 1.2 13.8Iceland 17.7 17.3 18.1 10.0 4.8 0.1 2.0 16.6 1.0 16.0Ireland 15.9 15.5 16.2 10.7 2.3 0.6 2.3 15.1 0.8 14.5Italy 15.7 15.5 15.9 8.2 4.2 n 2.3 15.5 0.1 mJapan m m m 9.1 3.0 m m m m mKorea 15.5 16.4 14.7 8.9 2.9 a 3.3 15.5 n mLuxem bourg m m m m 3.2 m m m m mM exico 12.2 12.2 12.0 9.1 1.3 a 0.9 12.2 n 11.8Netherlands 17.2 17.4 17.0 10.6 3.3 0.1 2.2 16.4 0.8 16.7New Zealand 17.1 16.5 17.7 10.2 3.8 0.3 2.9 15.3 1.8 14.8Norway 17.7 17.2 18.1 9.9 3.9 0.1 3.0 16.9 0.8 16.0Poland 15.6 15.3 15.9 8.0 4.0 0.3 2.0 14.0 1.6 mPortugal 16.9 16.6 17.2 11.0 3.0 a 2.2 16.9 n 13.7Spain 17.3 16.9 17.7 8.8 4.3 0.5 2.7 16.7 0.6 15.4Sweden 19.4 18.1 20.8 9.8 5.5 m 2.4 16.6 2.8 mSwitzerland 16.2 16.7 15.8 9.6 3.2 0.2 1.6 15.9 0.3 15.3Turkey 9.7 10.7 8.7 6.9 1.6 a 1.2 9.7 n mUnited Kingdom 17.1 16.4 17.8 8.9 5.7 x 2.5 14.2 2.9 15.4United States 16.8 16.1 17.5 9.5 2.6 0.4 3.5 14.9 1.9 16.3

Country mean 16.4 16.1 16.5 9.3 3.5 0.3 2.3 15.4 1.3 15.1

WEI participants Argentina 15.4 14.8 16.0 10.2 1.7 a 2.4 13.6 1.8 mBrazil 14.8 14.6 15.0 10.5 2.2 a 0.7 14.8 n 11.8Chile 14.2 m m 8.3 3.3 a 1.5 14.2 n 13.1China 10.1 m m 8.5 1.2 0.1 0.3 2.1 8.0 mEgypt m m m 7.7 2.0 m m m m mIndonesia 9.6 9.8 9.3 7.6 1.0 n 0.6 m m mJordan 11.6 m m 9.0 1.4 a 1.0 m m mM alaysia 12.1 11.9 12.3 8.4 1.6 0.1 0.8 12.0 0.1 10.7Paraguay 11.2 11.1 11.2 9.0 1.1 a 0.4 11.2 n mPhilippines 12.3 11.9 12.6 9.5 0.7 0.2 1.6 12.0 0.3 mThailand m m m 9.0 3.0 m 1.5 m m mUruguay 14.9 14.0 15.7 9.9 2.2 a 1.7 14.9 n mZim babwe 9.6 10.2 9.2 8.9 0.7 a n 9.6 n m

. Education for children under the age of five is excluded.ource: OECD Education Database. See Annex 3 for notes.

Educational Expenditure per Student

© OECD 2000

89

BB4

8 000

0 5 000 10 000 15 000 20 000 25 000 30 000

0 5 000 10 000 15 000 20 000 25 000 30 000

0 5 000 10 000 15 000 20 000 25 000 30 000

10 000

20 000

6 000

4 000

2 000

0

8 000

6 000

4 000

2 000

0

8 000

6 000

4 000

2 000

0

10 000

8 000

6 000

4 000

2 000

0

18 000

16 000

14 000

12 000

10 000

8 000

6 000

4 000

2 000

0

20 000

18 000

16 000

14 000

12 000

10 000

8 000

6 000

4 000

2 000

0

POLMEX

HUN1

PRT1KOR

ESP

SWE

FIN

DNK

JPN USA

AUT1CHE1

NOR1

BEL (Fl.)2

AUSNLD

DEUFRAUKM2

IRL

MEX HUN1

CZE

CZE

PRT1

KOR

ESP

GRC2

GRC2

UKM2

IRL

SWEFRA

FINNLD

AUS

DEUBEL (Fl.)2

AUT1

DNK

CHE1

USANOR1

JPN

MEXPOL

HUN1

TUR1

GRC2

CZE

KOR

ESP

UKM2

SWE

FINFRA

DEUIRL

NLD

AUS

JPN NOR1

DNKBEL (Fl.)2

CHE1 USA

AUT1

CAN

Chart B4.4. Annual educational expenditure per student in relation to GDP per capita,by level of education (1997)

Expenditure per student (US$ converted using PPPs) Expenditure per student (US$ converted using PPPs)

Primary education

1. Public institutions.2. Public and government-dependent private institutions.Source: OECD.

GDP per capita (US$ converted using PPPs)

GDP per capita (US$ converted using PPPs)

GDP per capita (US$ converted using PPPs)

Expenditure per student (US$ converted using PPPs) Expenditure per student (US$ converted using PPPs)

Expenditure per student (US$ converted using PPPs) Expenditure per student (US$ converted using PPPs)

Secondary education

Tertiary education

8 000

0 5 000 10 000 15 000 20 000 25 000 30 000

0 5 000 10 000 15 000 20 000 25 000 30 000

0 5 000 10 000 15 000 20 000 25 000 30 000

10 000

20 000

6 000

4 000

2 000

0

8 000

6 000

4 000

2 000

0

8 000

6 000

4 000

2 000

0

10 000

8 000

6 000

4 000

2 000

0

18 000

16 000

14 000

12 000

10 000

8 000

6 000

4 000

2 000

0

20 000

18 000

16 000

14 000

12 000

10 000

8 000

6 000

4 000

2 000

0

POLMEX

HUN1

PRT1KOR

ESP

SWE

FIN

DNK

JPN USA

AUT1CHE1

NOR1

BEL (Fl.)2

AUSNLD

DEUFRAUKM2

IRL

MEX HUN1

CZE

CZE

PRT1

KOR

ESP

GRC2

GRC2

UKM2

IRL

SWEFRA

FINNLD

AUS

DEUBEL (Fl.)2

AUT1

DNK

CHE1

USANOR1

JPN

MEXPOL

HUN1

TUR1

GRC2

CZE

KOR

ESP

UKM2

SWE

FINFRA

DEUIRL

NLD

AUS

JPN NOR1

DNKBEL (Fl.)2

CHE1 USA

AUT1

CAN

Chart B4.4. Annual educational expenditure per student in relation to GDP per capita,by level of education (1997)

Expenditure per student (US$ converted using PPPs) Expenditure per student (US$ converted using PPPs)

Primary education

1. Public institutions.2. Public and government-dependent private institutions.Source: OECD.

GDP per capita (US$ converted using PPPs)

GDP per capita (US$ converted using PPPs)

GDP per capita (US$ converted using PPPs)

Expenditure per student (US$ converted using PPPs) Expenditure per student (US$ converted using PPPs)

Expenditure per student (US$ converted using PPPs) Expenditure per student (US$ converted using PPPs)

Secondary education

Tertiary education

8 000

0 5 000 10 000 15 000 20 000 25 000 30 000

0 5 000 10 000 15 000 20 000 25 000 30 000

0 5 000 10 000 15 000 20 000 25 000 30 000

10 000

20 000

6 000

4 000

2 000

0

8 000

6 000

4 000

2 000

0

8 000

6 000

4 000

2 000

0

10 000

8 000

6 000

4 000

2 000

0

18 000

16 000

14 000

12 000

10 000

8 000

6 000

4 000

2 000

0

20 000

18 000

16 000

14 000

12 000

10 000

8 000

6 000

4 000

2 000

0

POLMEX

HUN1

PRT1KOR

ESP

SWE

FIN

DNK

JPN USA

AUT1CHE1

NOR1

BEL (Fl.)2

AUSNLD

DEUFRAUKM2

IRL

MEX HUN1

CZE

CZE

PRT1

KOR

ESP

GRC2

GRC2

UKM2

IRL

SWEFRA

FINNLD

AUS

DEUBEL (Fl.)2

AUT1

DNK

CHE1

USANOR1

JPN

MEXPOL

HUN1

TUR1

GRC2

CZE

KOR

ESP

UKM2

SWE

FINFRA

DEUIRL

NLD

AUS

JPN NOR1

DNKBEL (Fl.)2

CHE1 USA

AUT1

CAN

Chart B4.4. Annual educational expenditure per student in relation to GDP per capita,by level of education (1997)

Expenditure per student (US$ converted using PPPs) Expenditure per student (US$ converted using PPPs)

Primary education

1. Public institutions.2. Public and government-dependent private institutions.Source: OECD.

GDP per capita (US$ converted using PPPs)

GDP per capita (US$ converted using PPPs)

GDP per capita (US$ converted using PPPs)

Expenditure per student (US$ converted using PPPs) Expenditure per student (US$ converted using PPPs)

Expenditure per student (US$ converted using PPPs) Expenditure per student (US$ converted using PPPs)

Secondary education

Tertiary education

B7 Ratio of Students to Teaching Staff

© OECD 2000

118

� DEFINITIONS

Data refer to the schoolyear 1997/98 and are

based on the UOE datacollection on educationstatistics, administeredin 1999 (for details see

Annex 3).

This indicator shows the ratio of students to teaching staff and is obtainedby dividing the number of full-time equivalent students at a given level ofeducation by the number of full-time equivalent “ teachers” at that same leveland in the same type of institution. The classification of educational personnelused is intended to serve as a framework for classifying school personnel for alllevels of education. The classification is based on functions and organises staffinto four main functional categories. The classification is: i) InstructionalPersonnel; ii) Professional Support for Students; iii) Management/QualityControl/Administration; iv) Maintenance and Operations Personnel. Instruc-tional Personnel is sub-classified in teaching staff, i.e. classroom teacher, andteacher aides.

Teaching staff at includes professional personnel involved in directstudent instruction. The classification includes: classroom teachers; specialeducation teachers; and other teachers who work with students as a whole classin a classroom, in small groups in a resource room, or one-on-one inside oroutside a regular classroom. It includes chairpersons of departments whoseduties include some amount of student instruction. It does not include non-professional personnel who support teachers in providing instruction tostudents, like teachers’ aides and other paraprofessional personnel.

Staff reported as “ teachers” in early childhood education are generallysimilar to those reported in primary education.

Tertiary-type A and advanced research programmesTertiary-type B

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

Chart B7.2. Ratio of students to teaching staff for tertiary education(1997)

Number of students per teacher in full-time equivalents

Countries are ranked in descending order of number of students per teacher for tertiary-type A and advancedresearch programmes.

Source: OECD.

Greec

e

Tertiary-type Aand advanced research programmes mean

Tertiary-type B mean

Irelan

dSpa

in

New Z

ealan

d

Austri

a

United

Sta

tes

Czech

Rep

ublic

Japa

n

Germ

any

Hunga

ry

Austra

lia

Icelan

d

Sweden

Poland

Belgium

(Fl.)

With the exception ofGermany, the ratio of

students to teaching staffis higher in tertiary-type A

than in tertiary-type Bprogrammes.

Tertiary-type A and advanced research programmesTertiary-type B

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

Chart B7.2. Ratio of students to teaching staff for tertiary education(1997)

Number of students per teacher in full-time equivalents

Countries are ranked in descending order of number of students per teacher for tertiary-type A and advancedresearch programmes.

Source: OECD.

Greec

e

Tertiary-type Aand advanced research programmes mean

Tertiary-type B mean

Irelan

dSpa

in

New Z

ealan

d

Austri

a

United

Sta

tes

Czech

Rep

ublic

Japa

n

Germ

any

Hunga

ry

Austra

lia

Icelan

d

Sweden

Poland

Belgium

(Fl.)

With the exception ofGermany, the ratio of

students to teaching staffis higher in tertiary-type A

than in tertiary-type Bprogrammes.

Tertiary-type A and advanced research programmesTertiary-type B

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

Chart B7.2. Ratio of students to teaching staff for tertiary education(1997)

Number of students per teacher in full-time equivalents

Countries are ranked in descending order of number of students per teacher for tertiary-type A and advancedresearch programmes.

Source: OECD.

Greec

e

Tertiary-type Aand advanced research programmes mean

Tertiary-type B mean

Irelan

dSpa

in

New Z

ealan

d

Austri

a

United

Sta

tes

Czech

Rep

ublic

Japa

n

Germ

any

Hunga

ry

Austra

lia

Icelan

d

Sweden

Poland

Belgium

(Fl.)

With the exception ofGermany, the ratio of

students to teaching staffis higher in tertiary-type A

than in tertiary-type Bprogrammes.

Ratio of Students to Teaching Staff

© OECD 2000

119

BB7

Table B7.1. Ratio of students to teaching staff by level of education, calculations based on full-timeequivalents (1998)

Early Lower Upper Tertiary-type APrim ary All secondary Tertiary- All tertiary

childhood secondary secondary and advancededucation education type B education

education education education research prgs.

OECD countriesAustralia m 17.9 14.7 16.8 15.5 m 9.9 mAustria 18.6 12.7 9.3 9.7 9.5 m 15.7 mBelgium (Fl.) 18.0 14.0 m m m 10.5 m mCanada 16.2 21.0 21.0 23.1 22.1 m m mCzech Republic 15.9 19.2 18.1 13.0 15.4 11.4 14.3 13.5Denm ark m m m m m m m mFinland 11.9 17.7 11.0 m m m m mFrance m m m m m m m mGerm any 23.2 21.6 16.3 13.6 15.5 13.6 12.2 12.4Greece 15.9 13.6 11.4 11.6 11.5 21.9 28.5 26.3Hungary 12.1 11.0 11.1 10.5 10.8 m 11.8 11.8Iceland 5.6 14.1 m m m 8.4 9.5 9.3Ireland 14.7 22.6 x x 16.3 14.5 18.0 16.6Italy m m m m m m m mJapan 19.3 21.4 17.3 14.4 15.7 9.5 13.1 11.8Korea 23.6 31.0 22.5 23.1 22.8 m m mLuxem bourg m m m m m m m mM exico m m m m m m m mNetherlands x 17.8 m m 18.5 x x 18.7New Zealand 5.6 24.7 25.9 16.8 21.0 12.4 16.6 15.5Norway m 12.6 10.1 8.1 m x x 13.0Poland m m m m m m m mPortugal m m m m m m m mSpain 18.3 16.0 x x 12.1 10.2 17.9 17.2Sweden m 13.4 13.2 17.0 15.3 x 9.0 9.0Switzerland 1 18.7 16.3 12.1 17.6 14.0 m m mTurkey m m m m m m m mUnited Kingdom 21.5 22.0 16.7 16.7 16.7 x x 17.7United States 18.0 16.5 17.1 14.7 15.9 12.5 15.2 14.6

Country mean 15.5 17.1 14.9 15.1 15.2 12.5 14.8 14.6

WEI participantsArgentina 1 m 24.8 19.0 17.4 x m m mBrazil 1 m 27.3 35.2 36.3 x m m mChile 1 m 29.4 29.4 27.8 x m m mEgypt 1 m 14.2 21.6 12.6 x m m mJordan 1 m 20.7 20.1 16.9 x m m mM alaysia 1 m 21.6 19.7 20.4 x m m mParaguay 1 m 19.6 10.4 10.4 x m m mPhilippines 1 m 38.4 33.7 33.7 x m m mThailand 1 m 20.9 24.3 26.3 x m m mUruguay 1 m 20.7 14.0 29.8 x m m mZim babwe 1 m 37.2 22.5 5.5 x m m m

. Public institutions only.ource: OECD Education Database. See Annex 3 for notes.

© OECD 2000

123

CC1

OVERALL PARTICIPATIONIN EDUCATION

• The 1990s have seen big rises in the rate at which the population participates both in initial andcontinuing education.

• In OECD countries, the expected length of young people’s education rose since 1990, in threeout of four countries by more than a year.

• Today, children can expect to enrol for more than 15 years in education; in a third of all OECDcountries for even more than 17 years.

• In addition, adults in almost all OECD countries participate for more than one year full-timeequivalent in continuing education and training.

20

18

16

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

20

18

16

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

Chart C1.1. Full-time and part-time school expectancy under current conditions (1998)1

Years of schooling Years of schooling

Austra

lia

Pre-primary, primary and lower secondary education

Post-secondary non-tertiary education

1. Education for children under the age of 5 is excluded.Source: OECD.

Sweden

Finlan

d

Icelan

d

Norway

Denm

ark

Belgium

(Fl.)

Spain

Nethe

rland

s

New Z

ealan

d

United

King

dom

Portu

gal

Germ

any

United

Sta

tes

Canad

a

Franc

e

Switzer

land

Austri

a

Irelan

dIta

ly

Hunga

ry

Poland

Korea

Greec

e

Czech

Rep

ublic

Mex

ico

Turk

ey

All levels of education – 1990

Upper secondary education

Tertiary education

20

18

16

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

20

18

16

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

Chart C1.1. Full-time and part-time school expectancy under current conditions (1998)1

Years of schooling Years of schooling

Austra

lia

Pre-primary, primary and lower secondary education

Post-secondary non-tertiary education

1. Education for children under the age of 5 is excluded.Source: OECD.

Sweden

Finlan

d

Icelan

d

Norway

Denm

ark

Belgium

(Fl.)

Spain

Nethe

rland

s

New Z

ealan

d

United

King

dom

Portu

gal

Germ

any

United

Sta

tes

Canad

a

Franc

e

Switzer

land

Austri

a

Irelan

dIta

ly

Hunga

ry

Poland

Korea

Greec

e

Czech

Rep

ublic

Mex

ico

Turk

ey

All levels of education – 1990

Upper secondary education

Tertiary education

20

18

16

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

20

18

16

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

Chart C1.1. Full-time and part-time school expectancy under current conditions (1998)1

Years of schooling Years of schooling

Austra

lia

Pre-primary, primary and lower secondary education

Post-secondary non-tertiary education

1. Education for children under the age of 5 is excluded.Source: OECD.

Sweden

Finlan

d

Icelan

d

Norway

Denm

ark

Belgium

(Fl.)

Spain

Nethe

rland

s

New Z

ealan

d

United

King

dom

Portu

gal

Germ

any

United

Sta

tes

Canad

a

Franc

e

Switzer

land

Austri

a

Irelan

dIta

ly

Hunga

ry

Poland

Korea

Greec

e

Czech

Rep

ublic

Mex

ico

Turk

ey

All levels of education – 1990

Upper secondary education

Tertiary education

Chart C1.1. Full-time and part-time school expectancy under current conditions (1998)

EE5

EARNINGS ANDEDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT

• Education and earnings are positively linked. Upper secondary education is a break-point inmany countries, beyond which additional education attracts a particularly high premium. In allcountries, graduates of tertiary-level education earn substantially more than upper secondarygraduates. Earnings differentials between tertiary and upper secondary education are generallymore pronounced than those between upper secondary and lower secondary or below.

• Earnings of people with education below upper secondary tend to be 60-90 per cent of those ofupper secondary graduates.

• Tertiary education enhances earnings relative to upper secondary education much more forwomen than for men in five countries, whereas the reverse is true in the remaining countries.

0

200

160

120

80

40

0

200

160

120

80

40

0

200

160

120

80

40

0

200

160

120

80

40

HUNFI

NPRT

USACZE FR

AIT

AESP

UKMDEU

NZLCAN

PRTSW

EUKM

USAFI

NCZE

AUSDNK

NORNLD

SWE

CHE

CANCHE

DEUHUN

AUSESP

NZLNLD

NORDNK

ITA

FRA

Chart E5.1. Relative earnings of 25 to 64 year-olds with income from employmentby level of educational attainment and gender

Upper secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education = 100

Source: OECD.

Men

Tertiary-type B educationBelow upper secondary education

Tertiary-type A and advanced research programmes

Women

0

200

160

120

80

40

0

200

160

120

80

40

0

200

160

120

80

40

0

200

160

120

80

40

HUNFI

NPRT

USACZE FR

AIT

AESP

UKMDEU

NZLCAN

PRTSW

EUKM

USAFI

NCZE

AUSDNK

NORNLD

SWE

CHE

CANCHE

DEUHUN

AUSESP

NZLNLD

NORDNK

ITA

FRA

Chart E5.1. Relative earnings of 25 to 64 year-olds with income from employmentby level of educational attainment and gender

Upper secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education = 100

Source: OECD.

Men

Tertiary-type B educationBelow upper secondary education

Tertiary-type A and advanced research programmes

Women

0

200

160

120

80

40

0

200

160

120

80

40

0

200

160

120

80

40

0

200

160

120

80

40

HUNFI

NPRT

USACZE FR

AIT

AESP

UKMDEU

NZLCAN

PRTSW

EUKM

USAFI

NCZE

AUSDNK

NORNLD

SWE

CHE

CANCHE

DEUHUN

AUSESP

NZLNLD

NORDNK

ITA

FRA

Chart E5.1. Relative earnings of 25 to 64 year-olds with income from employmentby level of educational attainment and gender

Upper secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education = 100

Source: OECD.

Men

Tertiary-type B educationBelow upper secondary education

Tertiary-type A and advanced research programmes

Women

Chart E5.1. Relative earnings of 25 to 64 year-olds with income from employment by level of educational attainment and gender

© OECD 2000

293

E5 Earnings and Educational Attainment

© OECD 200

29

� POLICY CONTEXT

This indicator shows theearnings of workers

of differing educationalattainment relative

to those of individualswith upper secondary

attainment.

One way in which markets provide incentives for workers to develop andmaintain appropriate levels of skills is through wage differentials, in particu-lar through the enhanced earnings accorded to persons completing addi-tional education. The pursuit of higher levels of education can also be viewedas an investment in human capital. Human capital is the stock of skills thatindividuals maintain or develop, usually through education or training, andthen offer in return for earnings in the labour market. The higher earnings thatresult from increases in human capital are the return on that investment andthe premium paid for enhanced skills and/or to higher productivity. Earningsdifferentials are a measure of the current financial incentives in a particularcountry for an individual to invest in further education. Earnings differentialsaccording to educational attainment may also reflect differences in thesupply of educational programmes at different levels or the barriers in accessto those programmes.

� EVIDENCE AND EXPLANATIONS

Education and earnings for men and women

Education and earningsare positively linked,

whatever the typeof socio-economic systemor the degree of economic

development.

A substantial body of empirical research has shown the statistical connec-tions between educational attainment and earnings. In many of these studies,educational attainment is regarded not only as a qualification that offers accessto particular kinds of jobs and careers but also – in the absence of variablesthat measure skills directly – as an indicator of individuals’ knowledgeand skills.

The economic benefit of completing tertiary education can be seen bycomparing the ratio of the mean annual earnings of those who attended andgraduated from tertiary education with the mean annual earnings of upper sec-ondary graduates. The earnings disadvantage from not completing uppersecondary education is apparent from a similar comparison (Chart E5.1 andTable E5.1). Variations in relative earnings (before taxes) between countriesreflect a number of factors, including skill demands in the workforce, minimum-wage legislation, the strength of unions, the coverage of collective-bargainingagreements, the supply of workers at the various levels of educational attain-ment, the range of work experience of workers with high and low educationalattainment, the distribution of employment between occupations and therelative incidence of part-time and part-year work among workers with varyinglevels of educational attainment.

Upper secondaryeducation is a

break-point in manycountries, beyondwhich additional

education attractsa particularly high

premium.

The data in Table E5.1 show a strong positive relationship between edu-cational attainment and earnings. In all countries, graduates of tertiary-leveleducation earn substantially more than upper secondary graduates. Earningsdifferentials between tertiary and upper secondary education are generallymore pronounced than those between upper secondary and lower secondaryor below, suggesting that upper secondary education is a break-point in manycountries, beyond which additional education attracts a particularly highpremium. Among those countries which report gross earnings, the earningspremium for men aged 25-64 years with tertiary-level education ranges fromless than 40 per cent in Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden, to80 per cent or more in Finland, Hungary, Portugal and the United States.

0

4

Earnings and Educational Attainment

EE5

For women in the same age group, the premium for tertiary over uppersecondary education ranges from around 30 per cent in Italy and Sweden toalmost 90 per cent in Ireland, Portugal and the United Kingdom. Tertiary edu-cation enhances earnings relative to upper secondary education much morefor women than for men in Australia, Canada, Ireland, Switzerland and theUnited Kingdom, whereas the reverse is true in the remaining countries, espe-cially in Hungary, Italy and Spain.

Earnings of people with below upper secondary education tend to be 60-90 per cent of those of upper secondary graduates.

Earnings of men and women with below upper secondary attainment tendto be between 60 and 90 per cent of those of individuals who have completedupper secondary education. In 14 out of 19 OECD countries, men with lowerlevels of education fare slightly better than women relative to individuals ofthe same gender who have completed upper secondary education.

The earnings data shown in this indicator differ between countries in anumber of ways that may render some country-to-country comparisons of rela-tive earnings unreliable. Caution should therefore be exercised in interpretingthe results. In particular, in countries reporting annual earnings, differences inthe incidence of part-year work among individuals with different levels of edu-cational attainment will have an effect on relative earnings that is not reflectedin the data for countries reporting weekly or monthly earnings (see definitionsbelow).

� EDUCATION AND GENDER DISPARITY IN EARNINGS

Women still earn less than men with similar levels of educational attainment.

Although both men and women with upper secondary or tertiary attain-ment have substantial earnings advantages compared with those of the samegender who do not complete upper secondary education, earnings differen-tials between men and women with the same educational attainment remainsubstantial, reinforced by the incidence of part-time work for women.

In some countries the gender gap in earnings narrows with increasing educational attainment; in others it widens.

When all levels of education are taken together, women’s earningsbetween the ages of 30 and 44 range from about one-half of those of men inSwitzerland and the United Kingdom to around 77 per cent of those of men inHungary and Spain (Table E5.2). In a number of countries, but especially in theNetherlands, New Zealand and the United Kingdom, earnings differentialsbetween men and women narrow with increasing educational attainment. In anumber of other countries, by contrast, including Italy and Sweden, the reverserelationship tends to be true: earnings differences between men and womentend to be particularly high at the tertiary level. Thus, although higher educa-tional attainment is generally associated with higher earnings for both men andwomen, it does not seem to contribute systematically to reductions in genderinequality in earnings.

Some of the differences in earnings between men and women may beexplained by differences in career and occupational choices between menand women, differences in the amount of time men and women spend in thelabour market, and the relatively high incidence of part-time work amongwomen.

© OECD 2000

295

E5 Earnings and Educational Attainment

© OECD 200

29

There may be amovement towards more

equality of earningsbetween younger men

and women.

Earnings data by age suggest that there may be a movement towards moreequality of earnings between men and women of comparable educationalattainment. In eight countries out of 18, the ratio of female to male earnings atthe tertiary level is more than 10 percentage points higher among 30-44 year-olds than among 55-64 year-olds (Table E5.2). Hungary is the only countrywhere the gender gap in earnings is considerably wider for younger than forolder workers. Although the trend towards gender equality in earnings is lessobvious for the other levels of educational attainment, it is clearly reflected inthe overall numbers as well. This result might also be influenced by theincreased proportion of women among younger tertiary graduates.

� DEFINITIONS

Data are derived fromnational labour force

surveys (for details seeAnnex 3).

Relative earnings from employment are defined as the mean earnings(income from work before taxes) of persons at a given level of educationalattainment divided by the mean earnings of persons with upper secondaryschool attainment. This ratio is then multiplied by 100. The estimates arerestricted to individuals with income from employment during the referenceperiod.

Earnings data in Tables E5.1 and E5.2 are annual for most countries; forFrance, Spain and Switzerland they are monthly. In France, data cover theearnings of employees only. The Spanish data exclude people who work fewerthan fifteen hours a week.

The observed differences in relative earnings between countries there-fore reflect variations not only in wage rates but also in coverage, in the numberof weeks worked per year and in hours worked per week. Since lower educa-tional attainment is associated with fewer hours of work (in particular with part-time work) and with less stable employment (more likelihood of temporaryemployment or more susceptibility to unemployment over the course of ayear), the relative earnings figures shown for higher educational attainment inthe tables and charts will be greater than what would be observed from anexamination of relative rates of pay. The observed differences in relativeearnings of men and women within a country can likewise be affected by someof these factors.

0

6

Earnings and Educational Attainment

EE5

Table E5.1. Relative earnings of 25 to 64 and 30 to 44 year-olds with income from employment(ISCED 3/4 = 100) by level of educational attainment and gender

Below upper secondary Tertiary-type A and advancedTertiary-type B education

education research program m es

ISCED 0/1/2 ISCED 5B ISCED 5A/6

Ages 25-64 Ages 30-44 Ages 25-64 Ages 30-44 Ages 25-64 Ages 30-44

ustralia 1997 M en 87 83 120 116 144 138W om en 85 84 113 112 154 154M + W 79 75 103 101 136 131

anada 1997 M en 83 81 110 112 146 143W om en 74 69 117 118 164 165M + W 82 79 107 109 151 149

zech Republic 1998 M en 75 77 176 181 178 176W om en 72 76 127 124 172 176M + W 68 70 150 150 180 182

enm ark 1997 M en 86 86 124 121 139 139W om en 88 88 119 115 136 144M + W 85 85 115 110 140 142

inland 1996 M en 95 92 129 125 189 174W om en 101 99 123 122 179 172M + W 97 96 121 117 186 173

rance 1998 M en 88 88 130 137 176 175W om en 80 81 132 138 161 168M + W 84 85 126 132 169 171

erm any 1997 M en 88 87 106 108 156 144W om en 87 84 111 110 156 159M + W 81 82 108 106 163 153

ungary 1998 M en 74 76 x(5A/6) x(5A/6) 213 210W om en 66 69 x(5A/6) x(5A/6) 154 152M + W 68 70 x(5A/6) x(5A/6) 179 173

reland 1997 M en 76 83 114 122 165 177W om en 63 65 114 122 199 187M + W 76 80 117 122 183 184

taly 1995 M en 73 77 x(5A/6) x(5A/6) 173 161W om en 76 77 x(5A/6) x(5A/6) 129 133M + W 76 80 x(5A/6) x(5A/6) 156 148

etherlands 1996 M en 87 86 x(5A/6) x(5A/6) 136 129W om en 75 74 x(5A/6) x(5A/6) 141 145M + W 84 84 x(5A/6) x(5A/6) 137 132

ew Zealand 1998 M en 82 82 x(5A/6) x(5A/6) 148 126W om en 69 76 x(5A/6) x(5A/6) 143 146M + W 77 80 x(5A/6) x(5A/6) 148 134

orway 1997 M en 85 85 x(5A/6) x(5A/6) 138 140W om en 84 90 x(5A/6) x(5A/6) 140 143M + W 85 87 x(5A/6) x(5A/6) 138 138

ortugal 1997 M en 60 58 149 153 188 193W om en 62 59 129 135 189 205M + W 62 59 139 144 192 201

pain 1995 M en 74 73 98 103 171 158W om en 61 61 78 86 151 156M + W 76 71 96 104 161 151

weden 1997 M en 88 88 x(5A/6) x(5A/6) 135 135W om en 89 87 x(5A/6) x(5A/6) 125 121M + W 90 89 x(5A/6) x(5A/6) 129 128

witzerland 1998 M en 81 82 119 122 145 139W om en 74 82 123 122 157 164M + W 74 79 137 140 162 156

nited Kingdom 1998 M en 73 70 125 124 157 157W om en 64 61 135 133 188 192M + W 64 63 125 125 168 172

nited States 1998 M en 69 67 113 114 183 182W om en 62 60 127 130 180 191M + W 70 68 116 116 184 184

ource: OECD Database. See Annex 3 for notes.

© OECD 2000

297

E5 Earnings and Educational Attainment

© OECD 200

29

Table E5.2. Mean annual earnings of women as a percentage of mean annual earnings of men aged 30 to 44and 55 to 64, by level of educational attainment

Upper secondaryTertiary-type A and

Below upper and post- All levelsTertiary-type B advanced research

secondary education secondary non- of educationprogram m es

tertiary education

ISCED 0/1/2 ISCED 3/4 5B 5A/6 Total

Ages Ages Ages Ages Ages Ages Ages Ages Ages Ages30-44 55-64 30-44 55-64 30-44 55-64 30-44 55-64 30-44 55-64

ustralia 1997 60 55 59 54 57 59 66 57 61 56anada 1997 52 53 61 57 64 55 70 58 64 55zech Republic 1998 66 58 67 64 46 62 67 63 63 61enm ark 1997 74 72 72 69 69 67 75 73 73 68inland 1996 77 80 72 79 70 76 71 70 73 73rance 1998 68 65 74 70 75 76 71 65 73 62erm any 1997 60 52 63 53 64 68 69 59 62 48ungary 1998 77 81 85 107 x(5/A6) x(5/A6) 61 74 78 89

reland 1997 64 67 78 85 78 78 94 90 81 83taly 1995 69 72 69 49 x(5/A6) x(5/A6) 57 37 70 56

etherlands 1996 47 42 54 46 x(5/A6) x(5/A6) 61 48 56 43ew Zealand 1998 53 44 57 64 x(5/A6) x(5/A6) 66 41 59 54orway 1997 64 66 60 63 x(5/A6) x(5/A6) 61 64 62 61ortugal 1997 73 71 72 70 63 56 76 70 73 68pain 1995 62 m 74 m 62 m 73 m 77 mweden 1997 72 72 73 68 x(5/A6) x(5/A6) 65 66 71 69witzerland 1998 54 44 53 47 54 54 63 51 52 41nited Kingdom 1998 45 45 51 59 55 58 62 62 52 53nited States 1998 53 52 59 57 67 61 62 44 62 49

ource: OECD Database. See Annex 3 for notes.

0

8

An

nex

An

nex 3

Annex 3SOURCES, METHODS AND TECHNICAL NOTES

This annex provides notes on the coverage of the indicators as well as on methods, sources and the interpretation of the indicators. Itis organised by indicator. Only indicators requiring additional comment appear in this annex.

INDICATOR A2: Educational attainment of the adult population

� General notes

The most important change between ISCED-97 and ISCED-76 is the introduction of a multi-dimensional classi-fication framework, allowing for the alignment of the educational content of programmes from different countriesusing multiple classification criteria (Table 1). These dimensions include: 1) the type of subsequent education or des-tination to which the programme leads; 2) the programme orientation (whether it be general education or pre-vocational education or vocational education); 3) the programme duration (for the ISCED Levels 3, 4 and 5, whereprogrammes that vary widely in duration exist); and 4) position in the national degree and qualification structure. InISCED-76, there was no such provision. For detailed notes see glossary and the OECD publication Classifying Educa-tional Programmes, Manual for ISCED-97 Implementation in OECD Countries, Edition 1999.

� Notes on countries

In order to classify national educational attainment levels straddling two or more ISCED-97 levels, a simple ruleis used consisting of attributing the programme to the ISCED-97 level where most of the national educationalactivities are concentrated.

Table 2 comprises for each level of ISCED-97 the national programmes that are included in the respectiveindicators.

France: There is a clear distinction in France between the ISCED 3C short level (National level V, first levelof qualification equivalent to CAP-BEP) and the higher levels which groups together 3C long, 3B and3A programmes (national level IV, second level of qualification, the general, technological, and professionalBaccalauréats). For France therefore, students who have successfully completed secondary education and thosewho have a level of qualification corresponding to a short ISCED 3C programme are considered to have completedthe ISCED 3 level.

United Kingdom: United Kingdom attainment data at upper secondary level (ISCED 3) include a sizeable pro-portion of persons (about 7 per cent of the population) whose highest level of attainment will in general have beenreached at age 16. Although the programmes which they have completed do not formally satisfy the duration criterionfor the completion of ISCED level 3, they can lead to a qualification (5 A-C grades in GCSEs) that the United Kingdomconsiders to be at the same attainment level as that conferred by completion of a number of programmes which dosatisfy the ISCED criterion. In other words, the usual ISCED classification criteria have been relaxed for this group, forreasons of consistency with the national qualification structure.

© OECD 2000

327

AN

NE

X 3

© O

EC

D 2000

328

Table 1. Description of ISCED-97 levels, classification criteria, and sub-categories

0. PRE-PRIMARY LEVEL OF EDUCATION Main criteria Auxiliary criteria

Initial stage of organised instruction, designed Should be centre or school-based, be designed Pedagogical qualifications for the teachingprimarily to introduce very young children to a to meet the educational and developmental staff; implementation of a curriculum w ithschool-type environment. needs of children at least 3 years of age, educational elements.

and have staff that are adequately trained(i.e ., qualified) to provide an educationalprogramme for the children.

1. PRIMARY LEVEL OF EDUCATION Main criteria Auxiliary criteria

Normally designed to give students a sound Beginning of systematic studies characteristic In countries where the age of compulsor ybasic education in reading, writing of primary education, e.g . reading, writing attendance (or at least the age at whichand mathematics. and mathematics. Entry into the nationally virtually all students begin their education)

designated primary institutions comes after the beginning of systematic studyor programmes. in the subjects noted, the first year

of compulsory attendance should be usedto determine the boundary between ISCED 0and ISCED 1.

The commencement of reading activities aloneis not a sufficient criteria for classificationof an educational programmes at ISCED 1.

Destination for which2. LOWER SECONDARY LEVEL OF EDUCATION Main criteria Auxiliary criteria the programmes have been Programme orientation

designed to prepare students

The lower secondary level of education Programmes at the start of level 2 should If there is no clear break-point for this A. Programmes designed 1. Education which is not designed explicitlygenerally continues the basic programmes correspond to the point where programmes organisational change, however, then countries t o prepare students for direct to prepare participants for a specific class ofof the primary level, although teaching are beginning to be organised in a more should artificially split national programmes acces s to level 3 in a sequence occupations or trades or for entry into further

s which would ultimately lead vocational/technical education programmes.to tertiary education, that is, Less than 25 per cent of the programme

entrance to ISCED 3A or 3B. content is vocationa l or technical.

etween B. Programmes designed 2. Education mainly designed as an introductionry to prepare students for direct to the world of work and as preparationary access to programmes for further vocational or techn ical education.rs, only at level 3C. Does not lead to a labour-ma rket relevantducation qualification. Content is at least 25%ndary vocational or technical.

C. Programmes primarily designed 3. Education which prepares participantsfor direct access to the labour for direct entry, without further training, intomarket at the end of this specific occupations. Successful completionlevel (sometimes referred to as of such programmes leads to a labour-market‘‘terminal’’ programmes). relevant vocational qualification.

Destination for whichthe programmes have been Programme orientationdesigned to prepare students

n a A. ISCED 3A: programmes 1. Education which is not designed explicitlyat level 3 d esigned to provide to prepare participants for a specific class of

e dire ct access to ISCED 5A. occupations or trades or for entry into furtherents. vocational/technical education progra mmes.

Less than 25 per cent of the programmecontent is vocational or technical.

t have B. ISCED 3B: programmes 2. Education mainly designed as an introductionarket at level 3 designed to provide to the world of wo rk and as preparationme direct access to ISCED 5B. for further vocational o r technical education.

Does not lead to a labour-market relevantqualification. Content is at least 25%vocational or technical.

ssified C. ISCED 3C: programmes 3. Education which prepares participants to the at level 3 not designed to lead for direc t entry, without further training, intoation directly to ISCED 5A or 5B. specific occupat ions. Successful completion

Therefore, these programmes of such programmes leads to a labour-marketlead directly to labour market, relevant vocational qualification.ISCED 4 programmes or otherISCED 3 programmes.

is typically more subject-focused, often subject-oriented pattern, using more into ISCED 1 and 2 at the end of 6 yearemploying more specialised teachers who specialised teachers conducting classes of primary education.conduct classes in their field of specialisation. in their field of specialisation.

If this organisational transition point does not In countries with no system break bcorrespond to a natural split in the boundaries lower secondary and upper secondabetween national educational programmes, education, and where lower secondthen programmes should be split at the point education lasts for more than 3 yeawhere national programmes begin to reflect the first 3 years following primary ethis organisational change. should be counted as lower seco

education.

3. UPPER SECONDARY LEVEL OF EDUCATION Main criteria Modular programmes