A STUDY OF THE STAGE BAND MOVEMENT IN THE AMERICAN SCHOOLS A Paper Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School University of Minnesota Problems in Curriculum Construction Ed. C. I. 271 Under the Direction of James R. Murphy A Requirement for the Degree Master of Arts (Plan B) by Lauri J. Koskinen University of Minnesota Duluth, Minnesota August, 1969

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

A STUDY OF THE STAGE BAND MOVEMENT IN THE AMERICAN SCHOOLS

A Paper Presented to

the Faculty of the Graduate School University of Minnesota

Problems in Curriculum Construction Ed. C. I. 271

Under the Direction of James R. Murphy

A Requirement for the DegreeMaster of Arts (Plan B)

byLauri J. Koskinen

University of Minnesota Duluth, Minnesota

August, 1969

CHAPl'BR I Pace

In traduction • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1 I. The Problem • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •• 1

II. Setting of .the Stage BaD.cl , • • • • • • • • • • • • 2 III. The Approach, • • • • • • • • • o • • • • • • • • • I

CHAPl'ER II

I. B1atory.ot the Staae Baal • •• , ••••••• , • 4 II. Blues, D1x1•lan4 and • • • • • • • • • ,. • 6

III. Ohicqo Style • • • • • • , • • ,. • • • • • • • • • 6 IV. New York (Swiq) •••••••••••••••.•• ' v. Bop •. • ..• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • .• • • • • • • 10

VI. N n Trends • o • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • o • • 11 VII. The Stase Bad • • • • , , • o o • • • o • o • • • · l&

CHAP!'lilR III

The Proper Role ot the Stage Bucl • o •••• o o •• 16 I. J'azz and Popular llud. o o • o • • • • o • • • • • • 18

II. Performance Teohniquee , •• , , •••••••••. 21 III. Director's Beapona1b111ty , •.••••••••••• 83 IV. Goals ot the Stage B&Dd. • • • . • • • • • • • • • • • 84 v. Objectives ot the Stage Jaad ••••••••••• 86

OJ"ganizat ion and Mlmin1atrat1on ot the Stqe Baa4 I. Membership • • • • • • • • • • • • • , • • • ,

II. Soheduliq • • • • • • • , • , • • • • • • • • III, Instrumentation • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

IV. Personnel • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1', Rehearsals • • • • • • • • • , , • , • • • •

VI. Seating Arrangements • • • • • • , • • • • • , VII. llquipment • • • • • • • , • • • • • • • • , •

VIII. Public Appearance • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

CHAPI'D V ·

Methods and ilateriala tor Stase Ban4 • • • • • • I. Methods • • • • -o • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

II. Materials • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

.... •• ae •• 8'1 .. ., . . .. •• 11 .. u • •. H •• ae

•• to .. •o • • .M

1

· ......

u

Page

I. Summary •. • • • • • $9 II. Conclusions • • • • • • • • • • 62

BIBLIOGRAPHY • • • .. • • • • • • 63

..

Chapter I

INTRODUCTION

Since 1955 there has been a rapid growth of the stase band

in the American High Schools under the direction and auperviaiaa

of the school band director. Thia reflects

811 entire}¥ new trend in muaio atluea:Uoa ud should. be atu41ecl by

all serious educators. These ataae bBD4e are using a native Jmar•

ican art form as a basis for better mnaiaal trainins suah as

provisation, creative self•ezpreaaion and inatrumantal teehaique.

Tbe literature of th.e stage baa4 is alose to 1ihe stude:at•s om

contemporary music· and therefore, ia more meaaiqtul to him. Other

beaef'i ts gained from t41s oraaaizatioa are 1ihat 1 II8Jl1 •cUttiault'

discipline problema are diapelle4 or alleviated by au.Gll a presram.;

the student tends to maintain his intereet in hie 1natrumeat an4

music after graduation and, generally, sohool otf'ioials and ooncer.a-

ed parents have genui.ne respect tor the a44ecll student . aativttr.

I. THI PROBLllltl

Having a desire to organize stase bam4s in th• schools, direa-

tors and students vi tally needed intorm.aticm support ina the total etap

band program. Administrators, parents and atu4ents would waat to kaof •• . What is a stage band? ••• What purpo•• or fUnction would the staae baud

serve? ••• Does a stage band have Ulllaical value? ••• Doea it help improve

·the student's mus1o1ansh1p? •• ··eta.. 'l'he probl• tlilan as it eoaceraa

8

this writer, is to present a study that includes an historical view ot

the stage band; the role of the stage band in· the public school; the

organization and administration or the stage band and methods and mater-

ials for the stage band. With this at hand to present to

administrators, parents and students, the program would have a sound.

foundation in whioh to proceed an4, hopefully, succeed.

II. Sl'l'.l'IXG OF 1'HI S'l'AGll BARD

In past years, musiciaaa who played 4anoe bucls were aonsi4ere4 ._,_

to be rather unreliable characters; floaters and drifters. Tket were

road travelers and the nature of their ocoupat1on kept them workinc at

night and in an environmelit conaistinc ot :night clubs and clues halla

where spirits flowed treely. Music e4uoatora, in to avoid this

which was labeled on the dance band, begaa callina their 'daaoe•

bands, 'stage' banda. Another reason tor the chaaga is explained. by Stu

Kenton. "Not only is the attitude of muai o educators towar4 juz ohug1q

tremendously, but evan the name is beina okanged (to protect the inaoeent?).

'Dance' band is becomiuc 'stage' band, since with the acceptance of jaza

as a unique art form, the perton1n1 group is found more antl more .on

stage, playing for careful listeners, rather than in the .ballrOom or

nightclub providing functional mus1e for danoera. The school groupe

only an occasional dance, and that always under direct school

vision."1

lNeidig, Kenneth l., 'l'he BaD4 DireoteJ"' a Quid.e, Chapter 10, "The atace Bat• by Stan Kenton, Prentice-Hall Ino., Inglewood Cliffs, N.J., 1964, pp.l5-l6

III. THE APPRoACH

For this study, this writer has read various trade magazines that

presented articles featuring the stage band, i.e, Downbeat, MUsic Educators

Journal and the Instrumentalist, and attended various clinics durina

the last five years. SpecitiaallJ, I attended a week at Bemidji Band Camp;

a stage band contest at the 11n1Yarsit1 ot lfisaonsin, ·Dim Claire; aild stap

band clinics in MOorhead, Ch1c-.o aa4 11nneapol1a. Other information waa

gathered throuah the use of tazta and methol books aoncer.ntns the subject

and numerous talks with baDd directors, allminiatratora and atude:a.ta .. ia

public high schools and colleaea.

CHAPTER II

:. HISTORY OF THE STAGE BAND

The st9ge band has its beginning in jazz.

"Jazz beean about three quarters of a century ago. In New Orleans, soon· after lbancipation, there occurred an extra-ordinary concatenation of circumstances that could not have occurred elsewhere and, perhaps, can never occur again, even

From them jazz emerged. It began not merely as one more form of Negro folk musio in America but as a fusion of all the Negro musics already present here. These, the worksongs, spirituals, ragtime and blues all stemmed back more or less completely to African spirit and technique. Negro creative power, suddenly freed as the Negroes themselves ware treed from slavery, took all of this music and elements of Americaa white folk musics. It added, as wall, the music and the dis-tinct instrumentation of the marching brass band and the malo,. dies of French dances, the quadrille, polka, the rhythm end tunes of Spanish America and the Caribbean, and many other musical elements, The American Negro poured these rich and varied ingredients into his own musical melting pot and added his un-dying memories of life on the Dark Continent and the wild and tumultuous echoes of dimcing, shouting, and chanting in New Orlaaaa' Congo Square. Under the pot he built the hot fire of creative foroe and imagination and then, preparatory to a miracle, stirred th811l all together. For jtzz is no musical hybrid; it is a miracle of creative syntheses.•

Early bands in this period were called the archaic and classic bands.

Archaic jazz bands were largely street bands. Their main function was to

provide music for street parades, funerals, weddings and concerts. The

classic jazz band, a more formalized band than the archaic, provided muaic

for dancing and entertainment. Instrumentation of the classic band consist-

ed of one cornet, one or two clarinets, valve BBd/or slide trombone, guitar,

baas, piano and drums. These bands fUsed together the musical elements

1Blesh, Rudi, Shining Trumpets, A H1story of Jazz, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1958, p. 3

found in New Orleans and also, imparted a vocal timbre to wind instruments.·

Music of this was mainly polyphonic in nature. The cornet

carried the melody or lead, the trombone and clarinet the countervoioes

supporting the lead and the rhythm instruments kept a pulsating beat with

altern9tions of strong and weak aocents. Early contributors in this period

were Buddy Bolden, King Oliver, Bunk Johnson, and Freddie lCeppard.. Late

in this period, Louis Armstrong received his early training from King

Oliver.

I I. BLUl!B, DIXIELAND AND RAGTIME

The blues was the most important form developed by the new music.

,.When the spiritual was transformf;ld illto the blues, the content shifted

some; the emphasis was less on man's relation·to God and his future in

God's heaven, and more on man's devilish life on ea:::-th. All of the musi-

cal antecedents of late nineteenth-oentur,y song were summed up, however

indirectly, in the bluea.w2 Ragtime was another importaat form developed

at the turn of the century. It waa mostly piano musio, muoh ot it notated.,

adn eventually elements of ragtimf;l found their way into large ensemble

playing as did the blues. Disieland was the term used to describe the

efforts of white musicians in playinc jazz. Generally speaking, it

smoother sounding then Negro jazz and the·beat of dixieland seemed to be

pushed, rather than the blues style, which has the charaotaristie ot

ing the beat.

/

The new music, jazz, and its performers developed their art in a sec-

tion of New Orleans called 'S11oryv1lle', a place in which brothels, saloona

2ulanov, Barry, 4 History of 1azz in America, The Viking Press, New York, 1958

and cabarets were located and allowed to operate legally. This section of

town was created in order to curb the vices that were spreading through-

out the entire city. The closing of Storyville by the Navy Departmeat in

1917 also ended an era in jazz. With no place to work the musicians sought

jobs on the 'river boats• and in the city of Chicago. They also extended

the reach of jazz to the Eastern Seabetard and the Pacific Ooast traveling

in •road bands'.

III. CHICAGO STYLB

The music of New Orleans defined the form and style lmou aa 'Chicago'

style'. This style comprised the blues, ragtime and dixieland as it was

brought up from New Orleans. The Original Dixieland 1azz Band, founded by

Jack Laine, brought the white strain of New Orleans jazz to Chicaco and ther

weTe the first in history to out jazz recordings. Through their efforts the

style of dixieland was brought to the public and spread to New York sad

London. The Negro jazz that waa brought up f'rom New Orleans was played to

the 'black belt' of Chicago, the south side, and the white public did not

have an opnortuni ty to hear a more earthy form of musio. Along with dixielaa4

and the blues a •sweet' sound of jazz was introduced by Bix and

his Wolverine Orchestra. A major instrument change includes the

in jazz panda.

In addition to the styles mentioned musicians began experimeatins wi•a

l.arger instrumentation in their banda and therefore began to write arrance•

mente. This posed a number of problema tor musioiane and the musie they

were playing. Now the musiciaaa had to rea4 music; they had to play in

sections; no longer was improvisation unlimited; arraasera had control ot

7

the solo; the music began to be coaoaived vertically inateed ot hori-

zontally; arrangers had to have extensive musical trainina and know•

ledge, mere talent was not enough, and musicians themselves had to have a

highly dave loped performance ability in order to play the • charts'. This

experimentation laid the groundwork for the rise of the 'big baad era' ot

the 1930's.

IV. Nl!.W Yomt (SWING)

Swing is a term that derives out of the jazz style. Ia order to sell

big band jazz to the public, publicity men in Bngland in tae 30's ·leokiaa

for a new term other than 'jazz' because of the bad name and image it

curred during the '20's. Simply, they coined 'good jazz should swiag'.

"Durin& the decade of 1935 to 1945, a period known as the 'S.ina Ira', the greatest mass conversion in the history ot jazz took plaoe. Per swing music was sold -as a new kind of muaio- from coast to ooast, with all the hign-preasure tactics ot·modera publicity. It was brought to tlle attention of the public in the press au4 at tlle D10'f1••. on the stage u.cl in the ballroom, on the JU.-box aucl over the ra41o. And it made' converts for whom new words such aa 'jitterbuaa aa4 bobby-aoxer'a' were ooiae4. jad again, beeauae moat of thea were youna and likecl to d.anoe. 4i the s•e time, there wu a real 4emaad. •. With the repeal ot Prohibitioa in 1931, jazz wu broupt out ef tu speak-eaay. There was roem to apa4. The Depression HS fa41ag out as t'ar as mid4le-olaaa America waa concerae4, aa4 a vociteroue market sprang up amoag the oollece kids. !hey liked their mM810 hot and their baads big. -- the7 oould. pay tor 1 t. 3

The muai c of the swing era aouda mueh di:ftere:a.t thaa the juz of iln

Orleans. It is arranged; the instrumentation changed from tive er ai• to

twelve or more players; U amootllar, hller aa4 mere ·8Jl4 tu

rbythllla are muoll simpler tku tlle early •earo T'he 1aatl"UUI8ntatioll

included. five brass, :four reeds an4 tour :rh,_lml iDatrwaata. fte rllytllll

also ohange4 to a heavy 4/4 beat. Sect1oa work was iaportaat. ezaaple,

3staarna, Marshall w., The Story ot 1aaz, Oxford University Press, Bew York, 1958, p.200

8

all the saxes had to work tosetliler te proctuoe oae votoe. :Blen4,

matching· vibrato, etc. were all 1mpo•taat.

This arraagsaent of the music tor awtag band oame about wlta lletoker

Henderson in the eo• a. "1f1th the help of erancer Doa Re4man, a hot sole

line was harmoniz-ed and writta out tor the whole section, awincinc tocether.

Then arrangers retume4 to the W•t Mrioaa patten ot call and :respoaae, .

keepiq the two aeot1oaa aanuotaa eaell otlaer in aa af.leaa varietr·ot w.,a.

There were still hot aoloa oa t•P• wit:t& cme Ol" 1aoth aeo·Uoaa playiDC a auU-

ably arrauae4 bacqr0Ull4. At tu ._. uae, 1KJrJ!'CMie4 trca •1"0..-harmony to dress up the ':rift'. the t011r •-• weul4 repeat a

phrase in tour-part harmo.,, aa4 the five b»eaa would reply with a phrase

in tire-part htll'llllOny-all ot U tt.Bp4 with blue

Paul Whitma'a •aymphcm.io jas• strle ot saio aolcl the b11 b•cl to tlle

American public. In his OOiloe:rt at Rew YRk'a .Aaolia Ball 1A liM, he iB•

troduced a watePed down version of jus te the pUlalle and music oritiu u

well. It was rsceive4 with wide aa4 aaaure4 Wh1t...a ot oeumero1al

success for the next elevea year.. Ia the .... procraa, 1B Blue•

by George Gershwin, repreaotat tile •n 8U'1oua attempt to GOiloertize jus.

The most notable figu.re iD the ntaa era wu Beanr a.otmaa. •ot all

the talented mueiciaua who o811l8 out et Ohlaaao, )I.e was clearly tlle

polished, the most assured, the moat p«r&Q&81Ye atyliat • .S Ia ·the e .. ly

30' a, e band d.14D' t oatoh a aa he tra'Vele4 trom Bew York 'lie

California. oame attar hie style ranee& over moat of the possible

styles of the rJ!i.ddle and lata twenties ud. early thirties; attar ezpe:riuoea

in every possible king of eett1q1 raclie atucUoa, nipt oluba ud. 'ballrooms.

4stearns, Marshall w., 'l'b.e Story of laza, Oxror4 Un1versit7 Preas, Bn York, 1956, P• 199

5ulanov, Barry, A Histort ot lazz ill Ap!!l:ioa, The Vikin& Preas, ·N.Y., p. 187

..

...

' The National Broadcasting Compay sponson4 a Pl'Of11'8111 called 'Let • a Dace'

from 10 P.M. to I A.M. on Saturday evenings with Benny Goodman taking up the

last hour. In hie band were the best musicians in New York. With the

arranger, Fletcher Henderson, Goodman's music had a quality that only a few

big bands have had before, and it reached more people than jazz musicians

had ever dreamed of for an audienoa. "Fletcher's writing was so tight,

so adroitly scored in its simplicity, that each ot the sections soUD4e4 lik8

a solo musician; the collective effect was of a jam session •. A -is baa4

style was set that was never lost again, as the distinguished qualities ot

New Orleans and Chicago jazz ha4 beaD, at least to the public at larse.

after their peak periods. Attar the emergence of the Gooamaa baa4, all

the commercial bands tightened their.ensambles, offered momenta ot awingilll

section performance and even a solo or .two that were jazz-infected.• 0

Numerous bands and leading swins musicians also were deatine4 for auooess

and popularity in this era. Notably, Barry James, the Dorsey Brot-.ra,

Glen Miller, Gene Krupa, Duke lllinston and Woody Herlll81l to na• a tew.

Another style of bis band also was takinc shape i:a this era. The place

was Kansas City and the south west area. MUsic up to this time tor the moat

part recei vacl 1 ts maJor influence directly trom Hew Orleua with its blues

tradition. William 'Count' Basie was ltora in Red Bank, New Jersey. la!it•

had been playing with the Bennie MOten band in K&Daaa Oity and both mea

traded orr on piano. In 1935 Mote:a died., so Basie took over the baad..

Both piano players were steeped in rastime traclition althoush Basie leaa.ed

toward the blues tradition. His first band consisted ot nine pieces; tiM

horns and four rhythm The aooent was on rhythmic foundation.

6tnanov, Barry, A History of 1azz in America, The Viking Press, X.Y. 19&2, p. 187

10

Later, Basie expanded band to fifteen pieces •.

"Basis's whole band became a personification of the piano, not in the Bolden way of horizontal horn polyphony, but in

riffs of brass and reads and in solos over the riffs. As a direct result of the Count's early conditioning in rag-time's forceful delicacy, his band not only wailed and stomped with the southwest sound, but also really swung. Real swing, like the rolling momentum of the New Orleans band, is a thing both delicate and rugged, incompatible as the two may seem. But then, so is African drumming, with its imperious force expressed iD the most aonplexly delicate rhythms and cross rhythms. Any Baster.a ragtimer might conceivably have made this large orchestral syn-thesis of ragtime with the blues. Only Basie did.•7

Therefore, Basie showed us how the big band could exist in jazz with-out using the New Orleans formula.

V. BOP

Following the era of the swing banda the big banda declined 1a popular1t7•

The result of the Second World War; possibly the fickle taste of the Americaa

public and more probably, the in the musicians themselves toward this

by now commercialized big band style led to the opposite end of the scale •••

small groups, the 'combo' • However, the bia bands did not perish. Woody

Herman, Stan Kenton, Lea Brown, Duke Ellington an4 Count Basie kept the era

alive although in a very limited way compared to the 1935-40 period.

The new trend called 'Bop' was a reaction against the swing band, their

arranged music, their heavy 4/4. beat. and commercial sound·. Leading advocates

of the new school were Gillespie and Charlie Parker. Both musicians

resided in York. Basically the new form changed the beat to a lighter

quality,· introduced new harmonies and emphasized a style of playtac •cool'.

"Technically, one must first point to the weakening of the riff under the impact of bop, and the broad invention with which bop musicians have treated the twelve-bar form, departing·rrom the oonatr1ot1ng tonio-subdominant-dominant roundelay which has worn so many ears to a frazzle, carryiaa the melody from the first through the 1st bar, punctuating

?Blesh, Rudi, Shining Trumpets, A History of J"azz, Altred A. Knopf, Bn York, 1958, P• 363

ll

both the melody and its harmonia underpinning with bright and fresh interjections. Next in order are the up-beat accents of bop, the double-time penchant of such soloists aa Dizzy (Gillespie), and the vigorous change that has overtaken drumins under the ministrations of Kenny Clarke, Max Roach, and their followers. The bass drum was replaced by the top cymbal as

of the beat, and added a multitude of irregular accents and so1mds. Finally, in the key section of any analysis of bop, one comes to the use of unusual intervals, of passing notes and passing chords in the caastruotion of bop lines and their supports, ending with the celebrate4 identifying note of the medium, the flatted fifth, with which almost every bop performance comes to a close. Bop also discarded collective improvisation and placed all emphasis on the single line. Improvisation takes oa the character of a line that is primarily 4iatonic. The arpeggio has ceased to be important. The procedure is not up one chord and down another, nor is it up one scale and down another; the use of skips of thaa a third precludes this seesaw motion. The skillful use of fosters the evolution of many more ideas than does the use of arpeggios, since an arpeggio merely restates the chord. The bop . rhythm section used a system of chordal punctuation. By this mesas, the soloist is able to hear the chord without having it shoved down his throat, He can think as he plays. A chorus of bop may consist of any number of phrases which very in length. A pbrase may ooasiat of two bars or twelve bars. It may contain one or several ideas. The muaio is thoughtful as opposed to the kind of muaio whioh ia DO more than an endless series of notes, sometimes bent.•S

VI. NEW 'l'RJtlDS

Other trends in jazz introduced in the 1950's were 'Progressive Jazz•,

'Modern Jazz', 'Bast Coast Jazz' and 'West Coast Jazz'. Basically, these

styles had the same elements of music aa bop but the main difference was

in how the musicians played. For instance, the term 'Modern Jazz', a

school of jazz that appealed to the intellect. The musicians in this school

did not display any visable emotions. They looked •oool• ••••• that 1s, the

dynamics were kept moderately soft to soft. The tenor sax would pl87 in a

sub-tone quality which sounded very airy. The trumpet would produce muffled

tones instead of the normal which is its oharaoteristic aoun4.

Bu1anov, Barry, A History of Jazz in America, The Viking Press, New York, 1952, PP• 2?4-6

...

12

. Leaders in this style were Davia and Stan Getz. S.rd swing was a

term used to describe the 'West Coast' school of jazz. Essentially, it

was hard swinging bop with a hard driving rhythm section and full blow-

ing horns. Big bands incorporated elements of bop, such as change in

rhythm and harmony.

Presently, jazz musicians are experimenting with expandad rhythmic

structure such as.lA 1/2 /4; in harmony with twelve tone series of co.-

position, and atonality. Tape reoordera are also beina used for special·

sound effects in jazz.

Since the decline of the 'Big Band' era of the 30's and earlJ 40'•• the people also stopped dancing. Reasons for this are probably that they

had enough of the big banda, televiaioa ushered in a new form of home

entertainment, and moat likely, the new style of music (Bop) a&d the ra•

actions of the musicians toward the .public discouraged danctns. l81S hal

become music to listen to. HOwever, in .the early 1950's, a h1p-ewinataa,

guitar playing singer named Blvia Prealey started a music 1a

popular l!luaic. It was called 'Rook and Boll•.. It caueht on like· wildfire.

Practically all of America's youth joined the movameat a:acl adoptecl 1t ..

. their music. It was dancing msio aD4 new dances were 1atrotuce4. auoh aa 111le

trua, twist, swim, etc •• Instrumentation consisted of gultara an4·4rums . .

exclusively and almost all aonae were It waa basically an ott•

shoot of the atyld of 'Rhythm and Blues' ot au. earl1ea era·. It' a au•tlaul.11

to call early rock and roll muaio because the rbythm had a dull heav,r beat

and didn't ohange, harmony of three baaio ohorda, (to:nio-aub-

dominant-dominant ) , . the melod.J wae because there was so IIUOh

emphasis on the dynamics ••• which waa double ·forte ooaaiatently. 'l'llle ld.cla

13

didn't mine; it was their music. Presentty, rock and roU has calmed down.

Ona can the basic ingredients of melody, rhythm and harmony and

the 'Rook and Rollers' have contributed some very lovely songs in the

:Jopular style.

VII. THE STAGE BAND

Historically, the instrumentation and music style of the stage band

was developed through practical experience and experimentation of jazz

musicians and jazz bands. With the styles .of the blues, dixieland, rag-

time, the riff, .bop and modern jazz; from freely improvised music to arr&Bg-

ed and changes in instrumentation from five to six instruments, to

twelve and finally, to seventeen, the model was set. The first school staae

bands were organized Joliet, Illinois in 1915 with Archie McCallister as

director; in the A.ilstin High School in Chicago in 1924 with H.E. Nutt as the

director, and Clevel&ld Heights, Ohio, with Ralph Rush as the director.

·rhesa banda were organized at the request and with the approval of the sohool

administration. A closer look at the Austin band reveals this organization:

"Mr. !:iutt the Austin High School Stage Band in 1984 upon the. request of the administration, the student body and to fill a need for a group of students to play at school parties and dances. In order to be a member of the school stage band, the student was required to be a member in good standing in either the concert ban• or the orchestra. There were usually around forty students signed for this program. Mr. Nutt states that· these were in general the more ambitious youngsters who wanted ·to devote additional time for music. The instrumentation of' the large stage band was three violins, fi v& saxophones, threa trumpets, two trombones and rhythm. Mr. Nutt reports that in these early days of the roaring 20's, many arrugera would boot-leg arrangemeRts which they had supposedly·made exclusively for one band. Mr. Nutt states that the prosram was still in full swias when he left in 1934. At that time, he felt that the stage band proar• was a great asset to the school and of' considerable benefit to the students participating. As a matter of fact, many of' the students

14

graduating from the Austin Blgh School Stage Band wsnt on to earn their livings and win their fortunes in-the modern muaio field."9

Today there are stage band programs in the curriculum_ of more than

5,000 high schools. Student enthusiam has made stage bands the fastest

growing part of music education, and there will surely be increasing

fzom students to begin similar programs in other schools.

Charles Suber, publisher of Down Beat Magazine, has this to say: "The most

reliable estimate we have today ia that one out of every six high schools

in the United States has an organized stage baAd supervised by a school

paid educator. These stage banda are new as a movement, relatively old aa

each school's individual history. The real development of a dance music

movement in the schools did not eame until after lbrld War II. A number

ot factors then combined to make it possible for music students to pertora

in the 20th century iaiom. The years trom 1946 to the present have seeD&

American music accepted by our State Department, our concert halls, our

communities and our schools; new band directors with dance and/or jazz

training; the disappearance of bis •name• bands during World War II having

left a vacuum waiting to be filled.•l0

In 1955, educator Dr. Gene Hall, North Texas State College, Denton,

began to organize stage band clinics and festivals where the neophyte

banda could learn from each other and from the new stage band clinicians

that began to emerge. Professionals like Don Jacoby, Marshall Brown, Matt

Don, Organizing the Sohool Dance Band, San Antonio, Texas, Southern Music Company, 1955 p. 10

lOWiskirshan, Rev. George, c.s.c., Developmental Techniques tor the School Danae Band MUsician, Berklee Preas Publications, .Boston 15, Mass. 1961, p.3

15

Betton, and Buddy DeFranco started to hi.t the olinic t.rail and were

soon very much in demand. Also, on m teacher training level, prior to l955o

only Dr. Hall at Deuton was equipping· his music graduates with suitable

techniques for the stage band direction. Today, many colleges and univer-

sitiea are offering courses in jazz and in modern American music.

r·

16

.CHAP'.L'ER III

THE PROPER HOLE OF THE STAGE BAND

There are muny educators sad musicians who consider that the forms

of jazz and music are tru• art forma and are to be considered as

a valid unit of study to be included in the high school curriculua4 Also,

there are many educators and musicians who do not believe that jazz and . .

popular music are true art forma an4 are not to considered as a val14 unit

of study to be included in the curriculum. Tarioua other points of view

separate these groups. Namely; 1) the value of the literature performed

by the stage band is of little significance; 2) performance techniques

concernins 'concert' style and jazz (danae) style are not compatible; 3)

the curriculum of the total music suffers an improper balance.

These opposing viewpoints lead to confusion and especially trustratioa for

the 'band director who wishes to include a stase band in his music prosraa.

I. JAZZ AND POPULAR· MUSIC

Dr. M.E. Hall states in his text, 'Teacher's Guide to tae Bigb School

Stage Bw1d'; "It is odd that popular music, or jazz, has so little azpresaed

status in America. Our European relatives .consider jazz to be our one . original contribution to the arts and treat jazz musicians with the higbast

respect. Perhaps have a better appreciation of the artistey

involved in the performance of good jazz because its demands are· so 41tteraat

from their own.wl

1Hall, M.E.,Teaoher'a Guida to the High School Stage Band, Selmer, Ina., Elkhart, Indiana, 1961, p. 1

'.l

.,

·J;:

17

Noted composers have rao.opizad. jazz as an ·art form. and have aeea

valuable elements in the music. Ravel has been quoted. as coa-

sidering jazz to be the only original contribution America has ao tar made

to music. A posthumously published magazine article by Sergie Rachmaninott

stated, 'The seed of.the future music of America lies in Negro music•. The

French composer, Darius Milhaud stated: 'Among the Negroes we find the.souree

itself of this music - ita profoundly humaa side, which caa be as completelr

moving as any uni recocniz.ecl msical masterpiece. • Vir111 'l'ho1180D

stated 'This sort of music _is an ouUural an activitr as any. and more so \ha

moat. Certainly it is more rarely to be encountered at a higb ot

purity than the-symphonic stuff. Both kinds of music, of course, are de-

plorably commercialized tkese d.,a. · Ita purity, nevertheless, a aoacommaroial

quality, is wherein any music's cultural value lias.•2 Professional jus

musicians such as. StB;U Kent an Wfl'he change in the musician hiuelf hu

been especially significant. Today the typical jazz mDa1cian is a oollece

graduate who is extremely serious about his instruaeat aDd to.tally de4ioate4

to his art."3 Music educators racosalza the valua.of the art, jazz, and ita

many fol'IU. "A school sponsored. stace band is trowae4 upoa 1a some oirolea

but can offer valuable educative ezperianoea. It should be ramemberel that

popular music is well established as a social phaDDmenon and tirst haa4

familiarity with the style ia an appropriate tunctioa ot masio etuoatioa •••

Do not allow bland, pseudo- jazz style, but tea-ch autheatic atrle. w4

2Blesh, 'Rudi, Shininc 'l'rumpeta, A Bistorr ot .ruz, .Altret A. hoph, Bew York, 1958, P• 327-31 . .

3Naidig, Kenneth L., The Band J)1reotor's Guide, 'l'lla Stage Baacl by Staa Kea11ea• Prentice-Hall, Inc. 1 Inglewood Olitta, N.1., 19M, Chapt X

4House, Robert w. 1 Instrume:atal -lllaio tor Today' a SehOQlsl Prentice-Ball, Iae. Inglewood Oliffs, N • .r., p.l75

18

Charles R. Hoffer states in his hxt, 'Teaching 16ls1o in the SecondaJ7

School', "A strong case oau be made f'or some popular musical forma,

mainly jazz, as valid musical experiences, those which the schools

should not ignore.•5 Dr. Lowell 1. Weitz, supports the study of stage

band in the school when he states ia an article in Meyrea Band News:

"Jazz is as American as baseball or the hot doa. Attar seeking an

environment suitable for its deTelopment, it has at last taken root ta

our high schools and oolleses, where it provides study literature for

the stage band •••• It would seem wise to consider the various aspects

of each type of music and the purpose for whleb. it was oonatructel ·

if we are to fulfil our abligations as music educators. The challense

of' the e:xtensioa of jazz forms now rests with the music educator. It

he accepts it, there is an excellent opportunity for the step band

to become a valid and contributina part ot the hish school or

music program. Validity is governed by quality, aad quality ia tura

by the individual's musical tastaa. Even thou&D we each have our owa

musical preferences, as music educators we should be broad enougk to

acknowledge and prepare future musicians tor all types or music and

musical performance."6

-Ernst Krenek, the European composer, attacks jazz in this

'Jazz is anti-music; it explodes the tonal or4er in tae JUropean sense.•

This is the old idea that j&za is not a music in its ou ript but a

movement to destroy the European. 'In its character of anti-musio, jaza

5noffer, Charles R., Teaching Music in the Secondary School, Wadsworth

< . '

,J'

'

'i ·1

..i i

Publishing Company, Inc., Belmont, California, p.3l3 6wei tz, Lowell E. • The Stage Band aa a Part of the Kip School llusio ,; Program, Meyers Band News, 1965, p. 4

lV

generally takes an unscrupulous attitude toward the trad.i Uonal choice

of musical elements, and of harmonia elements in particular, since the

latter are the most direct characteristics of the sound language.•

Jazz, of course, has its own traditions line with the true nature

of music. Melody and rhythm are the most direct and natural character-

istios of the sound language while harmony ia an artificial developmeat.

Aaron Copland writes: "trom the oomposer•s viewpoint, jazz haa only

two expressions: either it was the well-kaowa 'blues', or the wild,

abondoned, almost hysterical and grotesque mood so dear to the youth ot

all ae;es. These two moods encompass the whole gamut of jazz emotion.

The only reply necessary to suoh an observation is that one should know

whereof he speaks. Let the authors of sueh dicta taka the trouble to

hear jazz, real jazz and enough ot it."7

Peter w. Dykema and Karl W. Gehrkens state this about jazz: "Jazz

music impresses the musical listener as being essentially saperfioial;

it is rhythm and tone quality glorified by a thousand trioks and con-

tortions; it is toot mnaic; it raaohea back into the jungle. But art

music springs from a deeper source; it has ita origin tar baek in the

mind and deep down in the heart; this is the aesthetic exparieaoe aD4

it is this that gives musio ita trem.odoua power in the hearts ot men

and women. But no such effect is experienced in response to jazz • .&

An answer to this charge is simply; jazz music i$ art music, the music

of the American jazz musician. These glorified tones and rhythms are

7 Blesh, Rudi, Shining Trumpets, A History of' .razz, Alfred A. Knopf', New York, 1958, p.333-335

8nykema, Peter W. and Gel1rkens, Karl W., The Teaching au4 .Administratioa of High School Musio, 0.0. Birchard and Company, BOston, l94l, p.i03

20

his aesthetic responses to his enTironment and represent his feelings.

The charges against the art form of jazz have been answered •••• to

the credit of j szz. If generalizat i_ons are in order, 1 t seems to me

that the critics have not had real experiences connected with authentic

jazz. At any rate, these·attaoks on jazz cio not seem to affect the

music or the growth of the art torok Also, they do not seem to affect

the continued perfoJ;"manoe of jazz by its players, or ita followers.

It the idiom did not offer some aesthetic experiences to trained (and

untraine4) musicians and ita supporters, it would have died loag ap.

Mr. Lehman states in an artiola in the •Music Educators Journal' J

"In any discussion of the stage band or of popular music, the ambiguity

ot terms constitutes a severe haadioap. On one hand, the term "popular

music" may refer to folk songs and to the genuine musical expression ot :'

sincere people. No one will deny a place in the academic milieu to

music of this sort. Indeed, ar-t music is profoundl7 indebted to folk

musie. On the other hand, the term "popular music• Dl8.J' refer to the··

commercial musical insanity that is manuf'actu.red and foisted upon a

public for no motive other than financial gain. Between

these two extremes is a vast array of' literature representing

an almost infini ta number of' qualitative graduations. Suspended vacua),;,- "

within this unbroken continuum is an 111 defined but sizable body of' ·

musio (including most jazz) whioh may ba termed pseudo-popular and which

constitutes a large portion of th-e repertoire of' the stage band. • 9 The

point stressed here is that the value of' most literature tar the stage

band is questionable. To be sura, this may be true. On the other haad

9Lehman, Paul R., The Stage Band; A Critical Evaluation, Musio Educators Journal, February-March, 1965, p.56

j

I .,, ,,

21

the stage band as well as the concert band, the concert orchestra, the

concert choir, have to wade through suoh literature to arrive at the

great masterpieces ot music. 'Possibly the task is not so great a chore

or as sustained for established music units such as concert band,

orchestra, or choir because of their very existence. The choir and

orchestra literature dates back wo well over three-hundred years ago

and the concert bailcl literature has transcriptions of the same literature.

They have had MSD7 years in which to accept or reject literature of value.

The stage band existence in the high school is new. Literature of any

lasting value has been around half a century ••••• in the minds of great

jazz musicians. The nature jazz is essentially c't'eative composition

through improvisation. It is truly a different art form from European

tradition. The road to this art form in the purest sense is through the

stage band where the students can learn the basic, at;thantic style deal-

ina with (now) writtan·soores and recordings. In the past the interested·

students in jazz had to learn the form in its environment, which hasn't

been morally acceptable. Now the student can legitimately learn the jazz

idiom in a prope·:t- setting in the stage band. Written li tf-lrature that is

suitable for high school use for study and performance has been in exist-

ence for leas than ten years. Time will correct this shortage.

II. PERFOBWNCE TiXlBNIQU&S

Many critics of the stage band state that perforrr.ance techniques

of the stage band are not compatible with •concert' technique. It is the

view of the supporters of the stage band that a good concert technique

22

is necessary in order to play stage band literature. A composite

position for this is held by Rev. George Wiskirchen, C.s.c., in his text, 'Developmental Teoru1iques for the School Dance Band Musio-

1!!!.', P. 3-6; Dr. M.l. Hall, 'Teacher's Guide to the High School Stage

Band •, p. 2; Paul w. Tanner, 'The Musical Values of the Stage Band',

Music Educators Journal, April/Cay, 1965, p. Walter L. Anslinger,

'The Stage Ba:nd: A Defense and an .Answer', Music .l!klucators Journal, .April-

May, 1965, i• 84-85; Philip N. Jones, Jr., 'The Stage Band; A Student's

View, MUsic·Jduoators Journal, February/March, 1965, p. 25. These

composite views of performance techniques are as follows:

l) The stage band will help develop tone. In playing stage band

musio, the performer must concentrate on a clean tone, its projection and

endurance •. Proper breath support must be stressed. Stage band performing

is ensemble performing. One player to a part. Therefo-re, the player

beoomes aware of tone it cannot be hidden in.a large reed or brass

sect ion. Also, the performer mus.t be constantly aware of blending and

balancins his tone with the section in which he is playing.

2) The stage band will help develop intonation. In the stage band

the player can easily hear his part both internally by himself and in

clear relationship with the rest of hie section and band. The student

is encouraged to 'listen'. He must develop a sense of tuning when.he

plays.

3) The stage band will help develop a sense of balance. An effec-

tive ensemble performance whether it be stage band or brass quintet de-

pends on each player 'balancing' his part in relation to the other voices.

The lead trumpet part for example, is clearly heard because 1t has the

23

top voice in a melody or phrase. The other trumpet players must match

their volume and vibrato to this lead. Many times the lead part is too

This is also true of the other sections.

4} The band will help develop precision. The band

does not nornally have a director aa we know it in the concert sense.

The let chair player is essentially the 'conductor'. The section ss a

whole must listen to his attacks, releases, his phrasing his various

jazz nuances and try to emmulate him as closely as possible.

5} The stage band will help develop reading skill. The syncopated

rhythms found in stage band music will reveal to the student a clearer

understanding and concept of note values. Any one who has played dance

music will admit that some of the passages are as difficult, if not more

so, than the average concert band or orchestral music. Another slight

is that dance band arrangements are written in keys not common

to the average concert band literature.

III. DIRECTOR'S RESPONSIBILITY

It may be true that the members of the stage band could consider

themselves the 'elite' members of the music program. In many oases the

stage band is the most popular performing group in school, with the

student body as well as the musicians. It is the director's responsi-·

bility to curb any resentment or conflicts that arise when this is the

situation. It is also the director's responsibility to curb any an-

tagonism that comes from band members other than the stage band members.

Popularity is no excuse for members or the stage band Qr non-members to

antagonize one another.

24

The stage band in the music program should in no way interfere

with the other musical organizations. It should not take rehearsal time

away from concert band, ensembles, marching band or solo study. Instead

it should assume the place of an additional 'ensemble' and scheduling

tor rehearsals, eto., be added in its proper place. In this

ensemble, the students will round out their range of musical experiences

to include the forms of popular music and jazz.

IV. GOALS OF THE STAGE BAND

The goals ot the stage band should be;

l} Music studeBts should derive a great deal of satisfaction in

playinc in the correct style ot popular music. and jazz.

8) Music students should appreciate the musicianship involved

in playing popular music and jazz and strive to master the

styles.

3) Music students should develop an understanding of the various

styles of popular music and jazz.

V. OF THE STAGE BAND

The objectives ot the stage band should be:

Knowledge of: l) musical literature from all jazz periods 8) basic musical jazz patterns and usages 3) jazz's development as an art form 4) the principal forma and performers

UndArstanding of: .l) problems of popular and jazz performance 2) elements of popular and jazz r:rusical interpretation

Skill in: l) producing a rich tone with good intonation 2) performing through ·improvisation 3) reading popular and jazz music 4) performing with others, independently, yet in proper

relation to the ensemble section and full band 5) playing with good technical facility

Attitudes of:

25

1) respect for popular and jazz music as an art and a profession 2) intention to improve one's popular and jazz musicianship

Appreciation of: l) skilled and tasteful popular and jazz performance 2) good popular and jazz music

Habits of:

1) frequent and efficient individual practi.ce 2) participating wholeheartedly i.n: pop•.Jl •Jr and Jazz r1us i cal

groups 3) regular and proper rehearsal attendance a:1d ettantion 4) selection of good popular and jazz recordi'lgs and concerts

86

ORGANIZATION .<\ND ADMINISTRATION OF THE STAGE BAN»

The organization and administration ot the stage band are similar,

and in some respects, different, to that of other musical units in the

high school. Responsibilities of the band director aonoerniDI sohedul-

ing, membership, rehearsals, publio performance, etc., have to be met.

These similarities and difteranoea will be discussed in.this chapter.

I. KIIIIBIRSHIP

in the school staaa. baild. should be open to any member

of the school orchestra, concert or.marohing band, and alao, anyone in

.the school student 8ody who can meet the requirements and

the musical experiences obtained t.rom the stase band. TO beoome a member

ot the stage band a student should pass minimum requirements suailar to

those set up tor the concert band. Ja examination consisting of playiac

ot scales, chorda, and sight. readiaa aa wall as a demoastration ot a

written knowledge ot music and lllllsical terms oan be used as an antranoa •:

requirement. Members should be selected by audition with emphasis ·plaoel

on the same factors ot musicianship as is emphasized tor the oonoart

band. Excellent tone quality, olean teohniqua, accurate time couatins

and goo4 intonation are just aa important in the stage band aa in the

concert band."l

lMcCathren, Don. 1 Organizing the Sohool Dance Band, San .Antonio, Texas, Southe.rn Music Company, 1955, p. 15

27

Membership in the stage band, to a large extent, is dependent on the

size of the school. In a large school, the senior high students could

be members of the ".A" band and the freshman and sophmore students could

form the •B" band. In smaller schools, the stage band membership would

include total senior high students (lOth, 11th, 12th srades). In many

cases, Jr. high school studeats would benefit from in the stage

band because they could gain experience by sitting next to the older

players.

II. SCH:EDULING

It scheduling permits, the stage band should rehearse on school time.

It this is not possible, noon hours, before and attar school and evenings

fill this need. Possibly sectionals from the stage band could be worked

in during the sohool day because of the fewer students involved. This

would be very advantageous for the band director because more time could

be devoted to the tull &and when they rehearse. Individual instruction

could be held during the school day for the same reason.

III. INSTRUMENTATION

The standard instrumentation of the school stage band generally

accepted is five saxophones, eight brass and four rhythm. These sect-

ions are broken down as follows:

Sax Section First Eb Alto Second Tenor Third Jib Alto Fourth Tenor Baritone Sax

Brass Section First Bb Trumpet Second Bb Trumpet Third Bb Trumpet Fourth Bb Trumpet First Trombone Second Trombone Third Trombone Four.th Trombone {Baas)

Rhythm Section Drume Piano Bass Guitar

18

It this instrumentation cannot be tilled, many stage band arranse-

meDta, specials and combo arrancftlenta are available.· For example,

Leeds Music Corporation has the "Basic 8 Dance Library Series.• (Piano,

Clarinet, 'l'rumpet, Tenor Sax, Trombone; Baas, ·Guitar and Druma). .Also,

uny atqe band can be played with two trumpeta, and one

trombone. One thiDC.to remember, though, is, it the instrumentation has

to lte lilllitecl, there must always be three saxophones, two altos 8Ild one

tenor,. when playina theae arrangements.

saxophone playa.rs on the high school level generally do not

4ou1Dle on other reecl inatl'WUntB such as clarinet and f'lute.. When these .,

instruments are scored for ta an arranaemant, it would be advantageous

to have cl&rinet players an4 flute players sit along side the saxophone

players to play tae part. MOst desirable though is to have the saxophone

players basin laarniq the clarinet, flute and other reed instruments.

Possibly the .flute players and clarinet players could begin on. saxophone

and contribute the band in this manner.

In the rhythm section, the string bass is the most desirable to play

the bass part. If an instrument or player is not available, then a tuba

could substitute for this instrument. In many arrangements both a string

bass and tuba would give a tuller sound. In the past few years, an

electric bass guitar has become to be used quite frequently. This instru-

ment could be used as a third alternative.

If the school music program includes an orchestra, possibly a string

section could be added for greater variety and color. Another tone color

that could be used very effectively would be that o.r a French horn section.

A third posaibility would be to use a choral group in special arrangement&.

89

When the stage band instrumentation is enlarged, this calls tor

special arrangements. This provides an excellent opportunity for members

to arrange for the band. New arrangements have been published by Kendor

Music this year featuring the stage band.· This series offers

the band director an opportunity to present material of a special nature

to highli&bt his stage band program. It also generates interest in those

students who heretofore were excluded by the standard. stage band instru-

DUtD.t at ion.

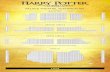

SUgaated Seatiy Ohar1i for the Augmented Stage Band

Perouaaion iat

Baas Clar. Bassoon

'luba

J'renoh horn

Bud Clar. Piano lst Clar.

Oboe 2nd Flute

let J'luta

Baas Guitar

Drums 2nd Trumpet

lst Trumpet 2nd Trom 3rd Trumpet

lst Trom 4th Trumpet let Tenor

8nd .Alto let .Alto

2nd Tenor Bari Sax

IV. PIBSONDL

3rd Trom 4th Trom

The director of the stage·band will have a distinot advantage if

he has had some first hand dance band experience. The notation, rhythm,

style and interpretation of stage band music will be far easier to explain

to his students and a mora authentic sounding stage band be the re-

sult. It a director has had· little or no experience, he may find·that

some of his students know mora about stage band music than he does. It

this be the oaaa, there are many ways in which to learn the stage band

style ot performance. First, many colleges offer stage band courses

dealing with performance, arranging and composition. Secondly, in many

30

sections or the country there are stage band clinics held during the

school year and during the summer months which provide the inexperi-

enced band director the opportunity to learn the stage ban4 style.

Correspondence courses devoted to the ttage band are available for the

band director. Fourth, m&n7 or his teaching colleagues could be of

assistance in explainin& demonstrating stage band style. It would

be desirable to have the band director in oharge and promote a stage

band instead or havinc the students form one qn their own. Problems

such as conflicts in rehearsals and playina dates between the concert

baud aad stage band will be avoided if the director has the respon-

stbllitJ tor both groups.

•The school stage band is an excellent training ground for the

development of leadership· qualities. A student director should be

selected either by the students with the. approval of the regular

director, or by the director, with the .approval of the students. The

main function of the student director is to take charge of the band

at rehearsals and engagements where the director is not present. This

student must show leadership qualities: reliability, congenial per-

sonality and musicianship. If the student does take charge of the band,

he must be sure sure to set the right tempo for the arrangements. '!'his

is a difficult task that requires study, concentration and

It ia a good idea that this student leader have an assistant. In this

way, the assistant oan gain experience fill in in case of emer-

gencies.

Section leaders are also appointed in each of the sections. In

31

the trumpet section, it is the first trumpet player, in the sax section,

the first alto, and the first trombone in the trombone section. The •

most experienced and talented will assume leadership in the rhythm

section. The sections leaders are responsible for the playing of each

member in their sections and should take charge at rehearsals. It is

also his responsibility to mark phrasing and dynamic.markings into his

parts of his section ao that the section functions together.

A librarian should also be appointed to charge of handling

the musio being use4 aa well as maintaining a suitable filing system

tor arrangements not beina currently in use. Chairs, stands, lighting,

public address system and other equipment is the of the pro-

party manager. Quite often this involves a lot of work so he should

have at least two appointed aasistants."2

The band director should handle all publicity and keep the school

and public informed on the activities the stage band. Organizing

the personnel is important to keep a smooth fUnctioning stage band.

The students also receive invaluable training in their offices.

V.

The atmosphere in a stage band rehearsal should be no different

than a concert band rehearsal. The students should enter and

warming up on lons tones, scales, and other materials that ere suitable.

Wild blowing and horseplay have no place in the rehearsal room. The

2McCathren, Don., Organizing the School Dance Band, San &1tonio, Texas, Southern Music Company, 1955, p. 19 ·

32

rehearsals should begin and end on time. The same factors of rnustoian-

ship that make a concert band or orchestra sound well will also make .

the atage band sound goo4. Rich tone, accurate intonation, expressive-

ness, precise playina, blend and balance are of extreme im-

portance and must constantly be considered during rehearsal.

Sectional rehearsals will save a great deal of tiMe,

in getting the correct notes and balance within each section. In the

sectional rehearsal, a student should strive to obtain the same kind

ot tone quality as ia played by the leader. Precision, vibrato, and

phrasing should also be worked out in sectionals. A pencil is an

invaluable piece ot equipment for any rehearsal. If ;;>layers will mark

phrases that are not obvious, and any other special effects such as

fortissimos, crescendos, decrescendos, etc. in their parts, they are

muoh more likely to remember these points when the music is performed •

.After the band is warmed up, (bands and other r.rusic groups warm

up by playing scales, iip siurs, arpeggios, etc.)individual tuning should

take place. Sometimes the sazophones tune with a tight embouchure, thus

causing the pitch to be sharp. When they use in playing than,

the pitch tends to be flat. Players should tune up with the same tech-

nique that they use while playing arrangements.

The·main responsibility of the rhythm section is that or keeping

a steady beat. Rehearsing the rhythm section, using a Metronome, 'is an

excellent idea. It helps the rhythm section to become conscious of a

steady beat and assists in the mastery of this important aspect of stage

band playing.

The same rehearsal procedure that a conductor uses in a concert

band should be applied to the stage band. Then the director will be

assured of positive results.

33

Proper ohoioe ot material is, of course, important. The arrange-

ments selected should be challenging, and yet must not be beyond the

ability of the players. Be certain that the players understand the in-

terpretation and meaning ot each arrangement, and that they know where

the real playin& problems are. Also, make su.re that the players listen

as they play •••• not only to themselves, but to the whole band. In-

dividual reading problema can often be allowing the student

to take the part home tor praotioe. If cost o! the band has trouble

playing an arrangement, it is too hard.

Exposure to hand manuscript is importan·t since most published stage

band arrangements and certainly all arrangements that night be specially

written for your band will be notated this

VI. SUTING AIUUNG.1114ENT

Seating arrangements of the stage band is very important. "One

of the m4tin differences betwe.en the professional 1md amateur stage band

is the important aspect of balance. I have heard many high school stage

banda in which the performers were exceptionally talented, but because

of lack of correct balance, they 'sounded' like an amateur group. All

school stage bands, I feel, should strive a 'professional sound'.

And, as we well know, a truly professional sound can only be obtained

with proper balance. In order to make it :·ossibl'9 to achieve the correct

balance, it is essential that the stage band be properly 'set up'.

Porky Panico's Recommended Saho)l Stage Band •set Up'

drums 2nd trpt 1st trpt 3rd trpt •th trpt

piano baas 2nd trom 1st tram

1st alto

3rQ. trom

3rd alto

4th trom

4th tenor guitar bari sax 2nd tenor

This is the ideal setup tor many reasons. The 'immediate harmony•

trumpets, the 2nd and 3r4, flank the 1st trumpet. This gives the 1st

trumpet, the 'lead', a stronger feeling of support, and permits a better

blend through the section. Notice that the 4th trumpet is immediately

to stage right· of the 3rd trumpet. The 4th trumpet is still oloae enough

to the lat trumpet to be able to judge the volume interpretation,

but or greater importance, it is next to the 3rd trumpet, which is the

immediate harmonJ.

The 2nd trumpet is on the extreme stage left of the section,

right next to the rhythm side. This arrangement is qui6t intentional,

because the 2nd trumpet is .considered the 'ad lib' soloist, and therefore,

should be as close to the rhythm section as possible. The 2nd trumpet is

sometimes referred to·aa 'jazz trumpet•, in that this is the part which

takes the solos, playing his own interpretation within the chord pro-

gressions of the arrangement.

You will notice on the chart that the trombone section is set up in

the same manner as the trumpet section. The 2nd trombone is placed next

to the rhythm section. The lst trombone is flanked by the 2nd and 3rd

trombones, and the 4th trombone (bass) is located on the extreme stage

right. The saxophone section is composed of the lst alto, 2nd tenor,

3rd alto, 4th tenor and Bth baritone. The lst alto is surrounded by

35

the 'immediate harmony• saxophones, 3rd alto 'and 2nd tenor. The 4th

tenor is on the right 3r4 alto because there is a span of harmony

between them of at least a fifth. This eliminates the low notes being

plaged in thirds, suob you will have if you place the two tenor sax-

ophones together. When 2nd and 4th saxophones are placed together, the

'rumblina' from these two instruments (caused by the ?armonio structure

of the arrangements), will disturb the balance of the reed section and

consequently, the entire band.

The baritone saxophone is on the ext.reme stage-left in order to re-

intoroe the string bass and 'piano baas•. Also you will note that between

the baritone saxophone and the 2nd tenor, there is a span of harmony,

thus eliminating the rumbling from this side of the reed section. The

2nd tenor saxophone ia on the left for still another reason. He is con-

sidered the 'ad lib' soloist, and should therefore be olose to the rhythm

section. On the chart, you will see that the baritone sax is on the left

aide of the band, whereaa·the 4th (bass) trombone is on the right side.

This arrangement is beat in order to give your band 'bottom• on each side.

By doing this, you will have a much better balance, and it will be easier

to achieve a full, rich sound.

Now, here is a point that should always be kept in mind. Never

split your rhythm section. They are an integral section, just as.the

trombones, trumpets, or the saxophones, and should be kept as cl.ose to-

gether as possible. If the rhythm section is split, chances are you will

have a fluctuation of the 'beat'."3

3Panico' s, Porky; 'Balancing Your School Stage Band', Conn Chord, 1964, p. 7

• . .:

36

VII. EQUIPMENT

The equipment usedby the stage band should be of excellent quality.

This applies to the instruments and mouthpieces as well as risers and

stands. Equipment should be selected within a section which will match

up in tone quality and volume. In the brass section, extremely shallow

mouthpieces should be avoided. UOuthpieoas and instruments should be

selected on the basis of obtaining a full sound. Also, small bores on

the brass instruments should be avoided. It will be almost impossible

to get a good bland and balance of tone within a section if one instru-

ment has a very small bore and shallow mouthpiece, while the others are

ot a aood bore and played with a standard mouthpiece.

IXtreme mouthpiece racings are to be avoided in the reed section.

One saxophonist or clarinetist using a 'wide open' facing may produce a

harsh, spreading type of tone which will not blend or the same carry-

ing characteristics as tones produced on more legitimate type mouthpiece

facings.

Students should obtain the best instruments that they can afford

and keep them in good condition. It is impossible to play well on a

poor instrument or one which is not working properly. Members of the

aohool stage band should take pride in their equipment and keep it in the

bast possible condition.

Attractive dance band stands will add greatly to the appearance of

the stage band. These can be obtained in a variety of colors and· styles.

Stand lights should be used during performances. They add more lustre to

the appearance of the stage band. Uniforms will add greatly to the total

37

appearance and morale of the stage band members. More •esprit de corps'

will be evident.

Cases should be used by each member of the stage band to carry his

own music. Music oases .will protect the music, keep it from getting lost

and allow the player an easy way of carrying it to jobs, rehearsals and

to hie home for practice •.

The brass should be outfitted with cup and straight mutes.

As the stage band earns more money, additional equipment such as hats,

bucket mutes, and plungers can be purchased • Instrument stands for

saxophones, clarinets, trumpets and trombones will insure that the in-

struments are not damaaed when they are not being played by the performer.

A public address system is a must. The vocalist needs one if she

ia to be heard above the band and announcements of the sets and numbers

to be performed by the band have to be heard by the audience. It is

well worth to purchase a 'quality• P.a. system. One that is in-

adequate is worse than none at all.

•The full drum set is used in the band. This consists of the

.snare drum, baas drum, hi-hat cymbals, at least one large sizzle cymbal,

two pair of brushes and sticks, a cowbell and two tom-toms. That which

is demanded is an arrangement whereby the drummer can comfortable play

the bass drum with his right foot and the ride cymbal with his

hand, hi-hats with his left foot and the snare drum with either hand.

The tom-toms should be nearby, within easy reaoh. In case of left-handed

drummers, the hi-hat is switched over to the right side. It is necessary

to fix the bass drum so that it will not slide. underneath will

36

help. As far as the drums themselves are concerned, the baas drum

. ' should be twenty to twenty two inches. The standard five inch saara

drum is the one in most common use for the stage band."'

VIII. PUBLIC .APPE.AR.ANClB

"One of the finest means ot motl vatioa for the members of tha school

stage band is that of attending a •'age baad. contest or {p.39-A)

.&iucaUve values to be gained by attendin& such an evant are: l) the

students and director receive an evaluation of the sroup•a performance

will be very beneficial to the group; 8) the studeata an4 director

will receive recognition for their work; 8) the students and 41reotor

will gain valuable experience and knowledaa; 4) the students and director

have an opportunity to meet and work with outstandlna ol1nio1aDS.

Other activities that the school stage baad may perform for are

school concerts, athletic events, dances and community tunotiona. With

regard to the school band and orchestra the stage bSDd should

be given equal time with other anaemblas. The concert ban4, ot course,

is the main or 11ajor perf'o:rmiq group. PossiblJ, the stage btm4 could,

from time to time, give their own ooncena, but they should aot iDter-

f'ere. with other scheduled The· stage band, oonoernina

athletic events, could alternate with the pap band for indoor events.

It is beet to have a larger group pl&JiD& tor outdoor eveata. !he staae

band should provide musio tor daaeea ani parties at the sahool. It a

4 LaPorta, John, Developing the Jllb School Stage Bead, Southera MUsto _Company • San .Antonio • Texas • 1905, p. XV 1lcCathren, Don. • Organizing the School Denes Baud, Sem Antonio, Texaa,

Southern Music Company, 1955, p. 36

dance or party is sponsored by a student activity group and charges

admission, the stage band should charge a small fee and e.nter that into

the music :f'und. If no admission is charged, the stage band should render

their services free. Under no condition should the stage hand play for

public functions unless it is given sanction from the adMinistration and

the band director.. If' the administration gives permission, the band .,

director must be responsible tor the appearance of' the group.

i .

' I· .•

r '

STAGE BAND

ADJUDICATION SHEET

39A

Close ________________ Instrumentation: Trucpet ( ) Trombone ( ) Srutee ( ) Rhythm ( other_· --------------------

Ne.me ot Faculty Director: ___________________ _

•

School ..... ________________ ..... ______ C.ity _____ ..... __________ ..... __________

Selections (1) _________ (2) __________ (3) ______ ;,;

St&Ddards 1 2 1 h li Constructive Comment & Particular BLIHD (Quality ot en-semble sound or tone)

IB'l'OlfATIOif ( Inst ru-I menta in ttme vi th each ..

other) ·/

BALAICE (Balanced dy-namic levels ot indi-Yidual instruments &Dd sections) RHYTHM (Does band mo.in-tain accurate rhythmic pulsation?)

PRICISIOB (Do sections and band pla, together precisely?)

DYBAMICS (Does band makE aoat ot con-trasts • ahadiD88?) :

..

INTERPRETATION (Phras-ing ot the .uaic in proper style)

ARRANGEMENTS (Are they well sui ted to band capabilities?)

PRESENTATION {Does band communicate well with & to an audience?)

Total Points: (9-16, Div. I; 17-26, Div. II; Div. III) .

Comments on individual musicians:

Suggestions for improvement of band'a· perfor.ance:

Rating: Division (I, II, or III) ------------

Judge's Signature -------------------------------------------

CHJPTJ§l V

METHODS AND MATERIALS FOR STAGE BAND

. I. METHODS

Method: Ralph, Alan, Dance Band Reading and Interpretation, Sam Fox Publiahins Company, New York 23, N.Y., 1962

40

Alan Ralph states: "This book is for those instrumentalists who

would like to familiarize themselves with, and become proficient in

playing toda.y's danae and jazz rhythms with a correct conception. The

book's basic principle combines a group of five comprehensive rules.

Basic Rules

I Quarter-notes are played short.

II Any nota lonaer than a quarter-note is given ita f'ull time value.

I

....

ll

"" , .........

.,- r

I

1

... D

I r

I I

/ • I

.... .... - "'" .. "" • •

.,:

III Single eight-notes are played short often r,. _..

,. ,.. ,.trl1 '

I I I .l I,,. Jl r I I 'li IV Lines of eighth-notes are played with.a

lift in a long-short manner, the same as eighth-nota triplets.

V Two or mora eighth-notes are slurred up to a quarter note (or ita equivalent), what aver follows is started by tonguing. (T)

J - I I I -· I. -I J_. I r

These are to be learned and applied to dance and jazz parts.

examples of the moat commonly used rhythms are presented, explained and

used in context with figurn and etudes throughout the book and presented

•

D. _D ..

41

in a variety of keys. As in dance arrangements, this book utilize&

the fUll range of most wind instruments."

Other basic material used in this text includes a section (with

examples) on 'special effects' or standardized stage band articulations.

The presentation of the material is very clear and easily under-

stood. First, an unmarked example of nusic is given followed by a dance

band interpretation of the same figure' n l • l n _ ......

- t' I r'a

I ;1. u/..1!- '3 t

I .., l" r _t, r u· I I , ••• l L 1,. J. . .. .l_:.t C_

... 1._ .:. I ·-I i/Jl . . .. .. ... I I , I I ,

ul.£

Next,a primer for one bar figures is presented:

I · The last eighth-note anticipates, and should 'f9el like'

the downbeat of the-following bar. This is why it is accented. Five primer examples are given.

When the student understands this clearly, he continues with a study

of thirty examples of one bar figures. Different rhythms and keys are

presented. Followina this section, five etudes are presented mixing all

ot the one bar figures. Baoh different figure in the etude is referred

to by number from the preoaeding one bar figure example.

The mora complex rhythms, syncopated quarters and eighths, antici-

pations, dotted eighth and sixteenth note rhythm and triplets are pre-

sented in the same manner as the basic rhythm patterns. Ten etudes are

included at thA end or the text which covers all the material presented.

...

Slllt

z.dar

·(/ize

d St

age B

and

Art

icul

atio

ns coM

PIL

ED

B

Y

M.\

TT

R

ET

TO

N

> F A r A • F • r F F - F

1/ra

r.u

Al·

rr11

f H

old

full

valu

e.

llea

ry A

ccen

t H

old

less

tha

n fu

ll va

lue.

Hea

t'Y A

ccen

t as

pos

sibl

e.

-"ta

ct·u

to

:-:.ho

rt·-

not

heav

y.

l.ryu

to T

oT

I!II

II'

Hol

d fu

ll va

llll'.

The

8hak

e .\

var

iati

on o

f t

tone

up

war

ds-

mur

h lil.

.t> a

tri

ll.

/,jp

TriU

:-'i

uula

r ln

sha

ke

hut

slow

t•r a

nd w

ith m

ore

lip <

·ont

rol.

Wid

e Li

p Tr

ill S

ame

as

ahov

e ex

<>ep

t slo

wer

and

w

ith w

ider

inte

rval

.

/ F ) r + r 0 r

The

Flip

Sou

nd n

ote,

rai

se

pitc

h, d

rop

into

follo

win

g no

te (

done

with

lip

on b

rass

).

The

Smea

r Sl

ide

into

not

e fr

om b

elow

and

n.-a

ch c

orre

ct

pitc

h ju

st b

efor

e ne

xt n

ote.

D

o no

t ro

b pr

eced

ing

note

.

The

Doi

t Sou

nd n

ote

then

gl

iss

upw

ards

from

one

to

five

step

s.

Du

Fals

e or

muf

fle-d

ton

e

Wah

l<

'ull

tone

--nu

t m

uffle

d.

Shor

t lJl

iN,,

1·,,

:o'lid

e in

to

note

fro

m l

wlu

w (

usua

lly o

ne

to t

hret

" sl

t>JI

S).

Lang

Glu1

1 {.'

p Sa

me

as a

bove

exc

ept

long

er e

ntra

n<'t'

.

Sho

rt Gli

1111

Dou

on

n.>Vf

'rst"

on th

e ab

c;wt g

)iu

up .

• _r

..

r

Long

Gli1

1s D

ouon

Sam

f' as

lon

g gl

iss

up in

rev

erse

.

Slw

rl L

ift E

nter

not

e vi

a ch

rom

atic

or

diat

onic

!K'al

e be

ginn

ing

abou

t a

thir

d be

low

.

Long

Lift

Sa

me

as a

bove

exc

ept l

onge

r en

tran

ce.

Sho

rt S

piU

Rap

id d

iato

nic

or c

hrom

atic

dro

p. T

he r

ever

sf'

of t

he s

hort

lift

.

Long

.o..; p

ill S

auw

as

aho\

't'

exce

pt

t·xit.

The

Plop

:\

rapi

d sl

ide

duw

n ha

rmon

ic o

r di

aton

i(' S

<·alt>

be

fnre

sou

ndin

g no

te.

lnde

jirll.

lt' S

l)und

D

f'ade

ned

toot

"-in

defi

nite

pi

tch.

.Vot

e:

No

indi

ridu

al

notn

ar

t he

ard

when

e.re

cutin

g a

gliu

.

43

Basically, the method covers quite comprehensively the rhythmic

aspect of the stage band style. The stage band director with experi-

enoa will find this method useful for instructional purposes. The

band director with little or no experience may have some difficulty be-