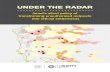

<HVK ĜPRO EDफDPSXV 7KH 7ULXPSKV DQG 7ULEXODWLRQV RI 7ZR /HIW:LQJ 6WXGHQW 8QLRQ )DFWLRQV LQ V ,VUDHO +LOOHO *UXHQEHUJ Journal of Jewish Identities, Issue 8, Number 2, July 2015, pp. 33-58 (Article) 3XEOLVKHG E\ <RXQJVWRZQ 6WDWH 8QLYHUVLW\ &HQWHU IRU -XGDLF DQG +RORFDXVW 6WXGLHV DOI: 10.1353/jji.2015.0020 For additional information about this article Access provided by New York University (17 Aug 2015 19:29 GMT) http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/jji/summary/v008/8.2.gruenberg.html

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

Yesh Śmol ba-Ḳampus! The Triumphs and Tribulationsof Two Left-Wing Student Union Factions in 1970s Israel

Hillel Gruenberg

Journal of Jewish Identities, Issue 8, Number 2, July 2015, pp. 33-58(Article)

Published by Youngstown State University Center for Judaicand Holocaust StudiesDOI: 10.1353/jji.2015.0020

For additional information about this article

Access provided by New York University (17 Aug 2015 19:29 GMT)

http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/jji/summary/v008/8.2.gruenberg.html

July 2015, 8(2) 33

Journal of Jewish Identities 2015 8(2)

Yesh Śmol ba-Ḳampus! The Triumphs and Tribulations of Two Left-Wing Student

Union Factions in 1970s Israel

Hillel Gruenberg, Jewish Theological Seminary

They say that a French student wakes up every morning, takes a bottle of cognac from his closet, drinks, and runs to protest. A British student wakes up in the morning, pulls a bottle of whiskey out of his closet, takes a gulp, and runs to learn. An Israeli student wakes up in the morning, takes a bottle out of his closet, fills it up, and races to grab an appointment with the Ḳupat Ḥolim [medical clinic].1

In February 1970, the above anecdote appeared in “Ḳampus—Daf la-Sṭudenṭ,” the Israeli newspaper Ma’ariv’s weekly section dedicated to events and issues relating to the lives of university students. Though the intention of the allegory is to be humorous, it reflects widely held popular perceptions of Israeli university students as politically obedient individuals concerned primar-ily with integrating into the state establishment and reaping its bureaucratic benefits at a time when their global counterparts were seen as focused on intel-lectual pursuits and political activism.2 Perhaps because of such views and their staying power, Israeli university students rarely appear in scholarship treating Israeli history, society, and politics, aside from brief and occasional references in work treating developments in Israeli political culture in the 1960s and 1970s.3 Most of these references to students relate either to the small but much-no-ticed extra-parliamentary movements in which a number were active, such as Matspen and Śiaḥ, or to the way in which Israel’s Student Unions were ineffec-tual and manipulated by mainstream political parties.4 In the 1970s, however, there were at least two left-wing Student Union factions,5 that, though exclu-sively based in the traditional institutional framework of Israeli Student Unions, remained completely independent of association with outside political parties and evoked the “spirit of ’68” in their ideological and practical approaches.6 One of these groups was Yesh, a group founded in Haifa in 1971 whose name means “to have” or “there is” in Hebrew.7 The other was Ḳampus, an acronym for Ḳvutsot la-Me’uravut Poliṭit ṿe-Ḥevratit Sṭudenṭialit (Groups for Social and Political Student Involvement), which was founded in Jerusalem in 1974.

Yesh and Ḳampus, both of which attracted Jewish and Arab students as members, were not the only left-wing or “bi-national” organizations that func-

Journal of Jewish Identities 34

Yesh Śmol ba-Ḳampus! The Triumphs and Tribulations of Two Left-Wing Student Union Factions in 1970s Israel

tioned on Israeli campuses in this period nor were they the only independent groups to vie for the leadership of Israeli Student Unions at this time.8 Yesh and Ḳampus stand out, however, for the support they gained in the course of their activities, which very well may have been numerically greater than that of some contemporaneous independent left-wing movements that oper-ated primarily outside of traditional institutional venues.9 It should be not-ed, however, that this consideration is based on a comparison of the number of student voters who supported Yesh or Ḳampus with inexact estimates of those who belonged to the Israeli left-wing activist groups Śiaḥ and Matspen. Though the former indeed appears to be considerably larger than the latter, it is not inconceivable that the majority of “members” of Matspen and Śiaḥ were more active than most of those students who showed up to vote for Ḳampus or Yesh. This ambiguity reflects a seemingly unavoidable challenge that comes with researching groups whose membership records are no longer available, if they ever existed. Regardless, there is no doubt that when com-pared to contemporaneous far left-wing parliamentary factions in Israel, Yesh and Ḳampus both represented a broader ideological spectrum and propor-tionally achieved greater electoral success.10 Despite this, Yesh and Ḳampus seldom appear in scholarly work covering the history of protest activities, po-litical culture, or peace advocacy in Israel in the 1960s and 1970s or in other periods.11 The general absence of Yesh and Ḳampus from the academic lit-erature, I argue, is rooted in the fact that their activities were based within Israel’s Student Unions, organizational frameworks that have been noted for the limited parameters of their members’ political activism, and their leaders’ co-optation by mainstream political parties.12 It seems that the quiescent, if not impotent, reputation of Israeli Student Unions has contributed to groups like Yesh and Ḳampus going largely overlooked, as their participation in a tra-ditional institution of power (or lack thereof) renders them less symbolically valuable as Israeli extensions of the “spirit of 1968” than extra-parliamentary left-wing groups that were active in the same period.

As domestic and foreign media outlets reported on the iconic student rev-olutionaries of the West, some in Israel sought an explanation for why their own university students were not “swept away in the waves of the global ‘student rebellion.’”13 For certain domestic observers, the divergence between Israeli university students and their supposedly “radical” global peers was a sign of greater maturity rooted in a healthy concern for self, state, and society. For others, the “deviant conformism” of Israeli students reflected intellectual lethargy, political apathy, and narcissism.14 In 1973 political scientists Rina Shapira and Eva Etzioni-Halevy published research affirming popular per-ceptions of Israeli university students as politically quiescent in general com-parison to their counterparts abroad. The scholars further argued that most Israeli students viewed higher education primarily as a means to professional advancement or integration into the central bureaucracy that dominated Is-raeli public life.15 Though such observations may hold true from the broadest perspective, they reflect assumptions about students in Israel and the world that may have led some to overlook currents of independent and surprisingly potent left-wing political activity in Israel’s Student Unions in the 1970s.

July 2015, 8(2) 35

Hillel Gruenberg

At the time Yesh and Ḳampus were active, leaders of Israel’s government and its universities recognized Israel’s Student Unions as the sole official framework for student organization.16 It is not without some justification that both scholars and popular observers have characterized Israel’s Student Unions as little more than “playgrounds” for the next generation of leaders of Israel’s mainstream political parties. The wholesale relegation of Israeli Stu-dent Unions along these lines, however, may have led exceptional groups like Ḳampus and Yesh to go mostly unnoticed, despite their success in establish-ing a broad front of left-wing Jews and Palestinian Arabs on campus to an extent that was never truly matched by the off-campus Israeli Left in the same period (or later, for that matter).17 From their platform within the Student Unions, these groups drew both explicitly and implicitly on tropes and tactics of the global student movements of the late 1960s as they loudly called for student empowerment, Israeli-Arab peace, and broad social change. None-theless, though many scholars have mentioned left-wing extra-parliamentary groups in which Israeli students took part in the late 1960s and the 1970s, they rarely, if ever, reference Student Union (SU) groups like Yesh or Ḳampus.18

Israeli Political Culture and Israeli Students in the Shadow of Two Wars

After Israel’s sweeping military victory in 1967, a wave of euphoric con-fidence washed over the Jewish public, as the existential threat that once loomed over it appeared to have been extinguished. This collective feeling of self-assurance receded to some extent in the wake of the War of Attrition with Egypt (1967–1970) and then dropped sharply following the surprise attack by Syria and Egypt that set off the 1973 Yom Kippur War. The public saw Israel’s unpreparedness for the 1973 War as a colossal failure on the part of the state’s leadership, then still synonymous with the Alignment party.19 The Alignment was formed in 1969 from the alliance of the socialist-Zionist Mapam party with the Israeli Labor Party, which itself grew out of a 1968 merger of Mapai, the dominant Zionist faction since the Mandate period, with two other par-ties.20 Mapai/Labor/Alignment had long gone uncontested as Israel’s hege-monic ruling party, though its prestige dropped sharply in the aftermath of the Yom Kippur War, which coincided with an economic downturn in Israel. Herut, the main party of the Israeli right wing, welcomed in 1973 a number of centrist and right wing groups into its extant alliance with the Israeli Liberal Party to form the Likud bloc that with a 1977 electoral triumph brought an end to the Alignment’s hegemony. The political and cultural changes wrought in the wake of the wars of 1967 and 1973 were not limited to the electoral realm, however, they were also seen in the rise of extra-parliamentary movements. Such groups broke free of Israel’s conventional partisan structure and operat-ed outside the traditional institutional bodies that had until then served as the dominant framework of political organization in the State of Israel and pre-state Yishuv. Two prominent Israeli examples of such groups are the left-wing Peace Now and the right-wing Gush Emunim. Both of these groups professed views that may have overlapped at times with one or more of Israel’s parlia-

Journal of Jewish Identities 36

Yesh Śmol ba-Ḳampus! The Triumphs and Tribulations of Two Left-Wing Student Union Factions in 1970s Israel

mentary factions, but their operational approaches were focused on appealing directly to the public through protest, rather than on legislative achievement. These and other extra-parliamentary movements in post-1967 Israel engaged in public protest to a degree previously unseen in Israel society, in the wake of which the wider Israeli public came to accept protest as a primary mode of political behavior.21

The aforementioned political-cultural shifts also might have been influ-enced by the rise of television in Israel, and the domestic media’s presentation of foreign developments including the 1968 student uprisings, the American civil rights movement, and the organized opposition to the Vietnam War. More than ever before, Israelis of all political stripes felt increasingly empow-ered to engage the state and its functionaries through acts of protest, whether they were initiated on an ad hoc basis or by incipient independent groups. The late 1960s also marked the coming of age of a new generation of Israe-lis who had not lived through the collective trauma of the battle for Israel’s independence. This development came to the fore in 1970 with the first of several Michtav ha-Shministim (letters by high school seniors), sent directly to Prime Minister Golda Meir protesting their impending military conscrip-tion. Although the government, press, and general public were highly critical of such a brash display of nonconformism, “such actions were tolerated and therefore became more frequent.”22

Israeli-Jewish university students were as susceptible to the post-1967 wave of confidence that washed over Israel as the rest of the Israeli-Jewish public in this period. This pervasive popular sentiment explains, in part, why Israeli university students did not take part in the groundswell of student dis-sent that spread throughout the globe in the late 1960s.23 While not a single undifferentiated mass, many if not most student protestors elsewhere were motivated not only by discontent with domestic issues, but also with the for-eign policy of their respective governments, especially in relation to American military intervention in Vietnam. Opposition to the American war in Vietnam played a central role in the 1965 student-led “sit-ins” and “teach-ins” in Berke-ley, and the 1968 students’ occupation of Columbia University buildings in New York, street demonstrations in Paris and Germany, and clashes with the police in Tokyo.24 Though some Jewish Israeli students may have been frus-trated to a limited extent with elements of the domestic situation, the majority of appear to have been party to the Zionist consensus on Israeli foreign policy. Most Jewish Israeli students (and citizens of all ages) at this time likely sup-ported their own state’s nascent military occupation of territories acquired in war because of a widely held siege mentality in Israel.25 They were according-ly unlikely to follow in the footsteps of foreign student protestors who were motivated in part by explicit opposition to the aggressive military policies of the United States, a country whose support for Israel grew after 1967.

Looking to the United States may also help explain the seemingly obse-quious political attitudes of most Israeli students in the years following the Six Day War, if we compare them to American university students after the conclusion of World War II. J. Angus Johnston argues that the American stu-

July 2015, 8(2) 37

Hillel Gruenberg

dent activism of the late 1960s stands out not entirely in its own right, but because it followed a protracted period of student quiescence in the 1940s and 1950s.26 Johnston shows how the GI Bill facilitated the matriculation of masses of veterans in American universities so that by 1947 they comprised half of the student population nationwide.27 American veterans were less interested in extracurricular pursuits than their younger peers and much like the major-ity of their Jewish Israeli counterparts were inclined to see higher education as a conduit to gaining secure employment and building a family.28 In this last point, Johnston’s work dovetails with Shapira and Halevy’s analyses of Israeli students in the 1960s, ‘70s, and ‘80s, the vast majority of whom were veterans and similarly concerned with issues of career and family develop-ment. Israel’s student population, however, unlike America’s, continued to be comprised by a large percentage of veterans. But Israeli university campuses would nonetheless serve as spaces in which some students would exercise their agency as proponents of social and political change.

Regardless of the geographic context, the political activism of students is often limited by the fact that, as Philip G. Altbach puts it, “student ‘genera-tions’ are short, and this makes sustained political movement difficult as both leaders and followers change.”29 Gerard Degroot strikes a similar chord, say-ing that, “the great weakness of student protest is that it is conducted by stu-dents” who by definition tend to be young, naïve, and “fail to take account of the cruel realities of institutional power.”30 Though this statement was in refer-ence to European students in 1968, it applies equally to those Israeli students in groups like Matspen and Śiaḥ who aspired to generate mass movements but failed to gain a substantial popular following.31 By contrast, while promot-ing their progressive agenda in a traditional institution, Yesh and Ḳampus garnered extensive support in their respective constituencies as reflected in the results of the Student Union elections in which they participated.

Though Jewish Israeli university students seem to have been very support-ive of the state in the time of the 1967 war, a number did indicate their mistrust in some of the traditional institutions and leaders of Israel and its universities. Opposition to Mapai was seen even before 1967 and the sociocultural chang-es that came in its wake. In 1966, a faction of the SU calling itself the Likud (bearing no relation to the Likud party that took over Israeli government in 1977) unseated the Mapai student cell in elections.32 Shortly after its victory, the students’ Likud held a much-publicized protest against a visit by German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, which provoked a forceful police reaction. The independent student faction’s leaders also criticized Prime Minister Levi Esh-kol to his face in March 1967 for visiting the university as a guest of the Mapai student cell rather than as a guest of the Likud-controlled Student Union.33 Though the latter case of protest is reminiscent of Yesh’s and Ḳampus’s critical attitude toward the establishment, the former demonstrators objected to the state’s association with a theoretical enemy of the Jewish people, rather than to the state’s neglect of the rights and welfare of all its citizens. The students’ Likud further differed from Yesh and Ḳampus in its almost exclusive focus on increased student involvement in management of the university’s academic

Journal of Jewish Identities 38

Yesh Śmol ba-Ḳampus! The Triumphs and Tribulations of Two Left-Wing Student Union Factions in 1970s Israel

affairs, not to mention its active avoidance of association with explicitly left-wing groups.34 In line with Halevy and Shapira’s assessment of Israeli student activism, Hebrew University students’ multi-year campaign for greater stu-dent empowerment abated in 1972, when the university agreed to allow stu-dent leaders limited, and mostly symbolic, representation in university organs dealing with academic affairs.35 Though the attribution of quiescence to Israeli university students after 1967 may be accurate to some extent, there were stu-dents who sought to exert a deep impact upon Israeli society. A number of these students utilized Israel’s university campuses as a space for promoting emergent ideas and movements that challenged the traditional institutional, ideological, and operational parameters of political activity in Israel.

The Israeli “New Left” On and Off Campus

Though the Alignment was the main object of declining trust in established political parties in Israel, membership in all political parties began to fall in 1969, especially among younger Israelis, while the number of extra-parlia-mentary political groups increased.36 Two of the most notable, if short-lived, extra-parliamentary movements that rose to prominence in the late 1960s were the Movement for Peace and Security on the left and the Movement for the Greater Land of Israel on the right. These now long-defunct organizations’ respective positions continue today, to some extent, to frame the debate in Israeli society regarding Israel’s relationship with the Occupied Territories.37 Both of these groups were short-lived and overshadowed by groups that came later, particularly Peace Now and Gush Emunim. Both the Movement for Peace and Security and the Movement for the Greater Land of Israel were comparatively moderate in political terms, though the period in which they were active also saw increased activity among more radical groups, namely Śiaḥ and Matspen.

Śiaḥ, meaning “discussion” or “dialogue” and also an acronym for ‘Śmol Yisraeli Ḥadash (New Israeli Left), and Matspen, literally meaning “compass,” have been mentioned briefly in the work of many scholars, and in recent years have been the subject of more extensive research.38 In 1962, a number of dis-gruntled members of Maki, then Israel’s dominant and adamantly pro-Soviet communist party, left the group to form Matspen. Though Matspen was tech-nically part of the “old left,” they were most active and prominent in the later 1960s.39 Moreover, the group fostered connections with activists in the Euro-pean student-led “new left,” and even brought Daniel Cohn-Bendit, one of its most prominent members, to speak at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.40 Matspen’s activities both at home and abroad also attracted the attention of Israel’s General Security Services (GSS), well known by its Hebrew acronym, Shabak.41 Even as the group’s level of activity and public visibility increased, its following remained small after the 1967 war, which it interpreted as confir-mation of its interpretation of Zionism as a colonialist movement.42 Śiaḥ was started by two groups of students. One group, based in Tel-Aviv, was com-

July 2015, 8(2) 39

Hillel Gruenberg

prised mainly of those who previously belonged to Mapam and were frus-trated by its merger with Mapai to form the Alignment in 1968. The other group, originating in Jerusalem, was made up primarily of non-Zionists, and some anti-Zionists, who found the approach of Matspen and other commu-nist groupings too radical.43

Matspen, perhaps Israel’s most iconic Jewish anti-Zionist group, has re-ceived greater attention from scholars, though Śiaḥ has also been mentioned in a number of well-known studies of Israeli history and politics.44 These small groups, both of which splintered into even smaller ones by 1973, may have at-tracted both popular and scholarly attention, at least in part, for their symbolic value as Israeli incarnations of the “revolutionary” left-wing movements of the West. We might consider this trend, in and of itself, something of an Israeli embodiment of a tendency rooted in the West. Even in recent years, it is still the often ill-defined “spirit of 1968” that attracts those scholars who seek to revive and reinforce its central themes, as well as those who seek to cast doubt on some of the popular mythology about the student movements of the 1960s and 1970s.45 Though official student organizations did at times take part in social and political struggles in these years, in general researchers have paid more attention to the then “new” movements that stood in total opposition to established authorities and were active mostly, if not exclusively, outside the framework of traditional institutions, such as Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), both the U.S. and German versions, or the French Situationist Interntionale (SI).46 Similarly in the Israeli context, extra-parliamentary and “extra-institutional” groups such as Śiaḥ and Matspen, mirroring youth-led movements elsewhere, have merited at least occasional mention by scholars. Though Yesh and Ḳampus evoked the same “spirit of 1968” in promoting protest, participation, and tolerance, they did so from within Israel’s Student Unions, institutional organs that have long been regarded as having little, if any, political significance.47

Even with the advent of extra-parliamentary activist groups, traditional political parties and institutions remained dominant in many areas of the Israeli public sphere, including student government. Despite this, Yesh and Ḳampus gained considerable popularity as factions of Israeli Student Unions in the 1970s. In doing so, they set themselves apart from, and possibly achieved greater popularity than, groups such as Matspen and Śiaḥ by focusing their ef-forts in a traditional institutional venue, and no less one regarded as little more than a “sandbox” in which the younger generation of Israel’s mainstream po-litical parties played.48 It is true that before the rise of Yesh and Ḳampus some Israeli student leaders strayed from Israel’s traditional political parties while demanding greater student input in academic affairs, though this was moti-vated more by self-interest than by an overarching critique of Israel’s socio-political order.49 By contrast, Yesh and Ḳampus appropriated Israeli Student Unions, organs of traditional institutions of power, not only as a platform for advocating academic reforms, but as a vehicle through which to promote broad social and political change. In this vein, the efforts of the student activ-ists of Yesh and Ḳampus are noteworthy at least insofar as they represent an

Journal of Jewish Identities 40

Yesh Śmol ba-Ḳampus! The Triumphs and Tribulations of Two Left-Wing Student Union Factions in 1970s Israel

attempt to adapt some of the idealistic tropes of the student uprisings of 1968 to the institutional and political realities of Israel and its universities in the 1970s. A group of Israeli students established the first branch of Ḳampus at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in 1974 and at other Israeli universities in the years that followed. Though the group engaged in sustained activity through the 1980s, it never succeeded in the leadership contests for any of Israel’s Stu-dent Unions. Yesh did not survive as long as Ḳampus, nor did the group ex-tend its reach past the University of Haifa, the initial campus on which it was established. Unlike Ḳampus, however, Yesh emerged as the ruling group of its school’s SU in 1972, though its reign would be short-lived.

Yesh: The Rise and Fall of an Independent Left-Wing Student Movement in Israel

The triumph and tragedy of Yesh is a peculiar story of ethnically and so-cially disparate groups of students uniting in support of a common politi-cal agenda. Unlike the Israeli students whose campaign for academic reform abated in 1972, Yesh was founded on a broad platform of social and political activism inspired by the student activists of 1968 and it counted some then-recent immigrants from South America and France as members.50 The group stands out for both cobbling together a wide coalition of students at the Uni-versity of Haifa, and for rising to lead the school’s SU, if only for a short pe-riod, while actively criticizing state leaders’ failure to address growing prob-lems such as widening socioeconomic gaps and the increasingly entrenched presence of Israeli military forces and civilian settlements in the territories occupied since 1967 . . . .

Yesh did not start out as a formal bloc within the Haifa University SU; rather, it evolved from a student discussion group in the 1968–1969 academic year and only later became an active faction of the SU from 1971 to 1973.51 Responsibility for the initial spark that led to the formation of Yesh lies with a group of South American Jews who came to Israel after the Six-Day War.52 In their dormitory in Haifa’s Romemah neighborhood, these students estab-lished a club for discussing and debating social and political issues. The South American founders of the Romemah club eventually welcomed a number of Arab students as members, as well as some Jewish students of North African descent who immigrated to Israel from France after taking part in the stu-dent uprisings of 1968. In the Romemah group, these students found common ground in their disaffection from an Ashkenazi elite and a government that failed to fulfill its promises to them either as Israeli citizens or recent Jew-ish immigrants. Their ranks were further bolstered by a number of left-wing “veteran” Israelis, including some kibbutz members who had previously be-longed to Mapam and its affiliates but were frustrated by what they saw as its submission to Mapai/Labor in forming the Alignment.

As the Romemah discussions continued into its second year, the Latin American students expanded their communal activity. They set up an inde-

July 2015, 8(2) 41

Hillel Gruenberg

pendent immigrant absorption center on campus to provide student immi-grants with services they felt the Jewish Agency was neglecting to provide as promised.53 They also published their own newspaper, Aliyah v’Kotz Bah, which takes its name from a Talmudic aphorism that translates roughly as “a fly in the ointment.” The paper’s title bore particular meaning for the recent immigrants as aliyah, the Hebrew word meaning “ascent,” is the discursive term in the Zionist lexicon for immigration to the Land of Israel. Accordingly, Aliyah v’Kotz Bah as an adage conveyed these students’ collective frustration with Israel’s enticement of Jewish immigrants, on one hand, and its failure to properly attend to their needs or promote their absorption upon arrival, on the other.

In early 1971, students affiliated with the Alignment proposed to members of the increasingly visible Romemah club that they run on a joint list in elec-tions to Haifa University’s Student Union. It was decided that the joint list would be called Yesh, though the Alignment-affiliated students split off from the bloc not long after elections.54 Ironically, it is possible that figures within Israeli political and security agencies may have contributed to, if not indirect-ly caused, Yesh’s rise to power. On March 30, 1970, Yoram Katz wrote to Shm-uel Toledano, then the prime minister’s Advisor on Arab Affairs, reporting a request from GSS agents for him to interfere55 in the upcoming SU elections in Haifa to prevent the formation of an independent Arab student organiza-tion.56 Katz, the director of the northern branch of Toledano’s office, promptly asked the leaders of two student factions to integrate Arab students into their party lists and though they complied with his request, neither placed an Arab candidate high enough on their party list for them to be elected as a represen-tative. As part of Yesh’s alliance with the Alignment student cell in the 1971 elections, however, four Yesh representatives, one of whom was a Palestinian Arab, gained seats on the central council of the Student Union. Though no indisputable line of causation can be drawn here, it is worth noting Katz’s involvement in the 1970 student elections at Haifa University in light of the subsequent rise of Yesh through its alliance with the Alignment student cell.

Beginning in 1971, Yesh launched its initiatives from within the institu-tional framework of the Student Union; many of its members’ activities were reminiscent of the student movements in Europe and the United States that had gained worldwide attention in the late 1960s. Drawing on the French stu-dent movements’ model of solidarity with labor, Yesh publicly supported and participated in the protest activity of local striking workers whose company had been sold and were faced with losing their jobs.57 Inspired by the feminist movement that emerged in tandem with student-led civil rights and anti-war campaigns in the United States, Yesh members led by the American-born lec-turer (and later founder of Israel’s Women’s Party and Member of Knesset) Marcia Freedman lobbied for the university to provide daycare to the mothers among its students and faculty who aspired to expand their professional and educational horizons.58 In reaction to allegations that the university had re-fused to give employment to an Arab student based on a negative review from the Shabak, the group cooperated with a number of lecturers to set up a “free

Journal of Jewish Identities 42

Yesh Śmol ba-Ḳampus! The Triumphs and Tribulations of Two Left-Wing Student Union Factions in 1970s Israel

university.”59 The free university gained popularity among student activists following its initial conception at University of California, Berkeley in 1965 and was replicated at myriad U.S. universities in the years that followed.60 The free university provided space for more participatory learning, experimental pedagogy, and unconventional courses that were unlikely to be offered by es-tablished universities, such as “Revolutionary Thought and Action” at Berke-ley in 1965, and “Guerilla Theater” in Haifa in 1972.61 In the United States, the free university also served as a launch pad for campaigns challenging tradi-tional universities to make their curricula more relevant to modern society, particularly in relation to women and minorities.62 Similarly in Israel, the free university exposed students to content and critical approaches that were lack-ing in the established curriculum, and also served as symbolic criticism of the rigid structure and limited parameters of the state’s universities.

On November 3, 1971, Gideon Spiro, “the driving force in Yesh,” launched what was arguably the most group’s most noticeable and innovative initia-tive, the newspaper Posṭ Morṭem.63 As the editor, Spiro drew on previous expe-rience as a professional journalist in Israel and America. Posṭ Morṭem covered a wider array of subjects than its predecessor at Haifa University or most other contemporaneous Israeli student bulletins.64 Spiro adamantly encouraged his writers to tackle sensitive and controversial issues whether they related to the university or to society at large, believing that, “Just as a student must influ-ence the society in which he lives, they also have the right and the obligation to influence the curricular and administrative approach of the institution in which he studies.”65 And, far from being the mouthpiece of one segment of the student body, Posṭ Morṭem welcomed viewpoints from throughout the Israeli political spectrum.66 Though the paper quickly earned the ire of Haifa Univer-sity leaders as it accused figures in the administration of improprieties and mismanagement, Spiro insisted that the paper would maintain its approach as it upheld the highest journalistic standards and continued not to be another “arm of the system.”67

In Posṭ Morṭem we see a clear example of how Israeli students managed to reach a wide audience (the student body of Haifa University) with content that was innovative but conventional in form. While it may have been a new publication, the “student newspaper” itself is an institutional tradition that transcends Israeli history, and had proven itself useful in student protest and criticism in the U.S. civil rights and anti-war movements.68 Spiro’s leadership of a stridently independent student journal reflects how Israeli students could raise the level of critical debate through a traditional institutional framework. This was no more apparent than in February 1972, when Spiro published an article alleging that Shabak agents harassed Adel Manna, a Palestinian Arab and an Israeli citizen who was then finishing his undergraduate degree at Haifa University and today is a well-known scholar. Israeli censors might have suppressed this story had they gotten wind of its intended appearance in print, though Spiro claims to have ignored the censor’s repeated requests to review issues of Posṭ Morṭem prior to print release.69 Manna reported that when he was first approached by a Shabak agent in the summer of 1971 he was

July 2015, 8(2) 43

Hillel Gruenberg

asked to collaborate with the agency, and was told that his open expression of “radical,” “anti-Israel” views could “cause him harm,” at least insofar as his prospects for employment were concerned.70 Manna claimed to have respond-ed to the Shabak agent by saying that his views were relatively moderate and in no way “anti-Israel,” and that if he knew of anyone associated with terror-ist activity he would have already reported it. In the weeks and months that followed the disclosure of Manna’s experiences, a number of Arab students came forth to share similar reports in the pages of Posṭ Morṭem.71 And while it is clear that Spiro was critical of the Shabak’s tactics, as editor he nonetheless allowed for the publication of another student’s op-ed defending the Shabak’s approach in the context of its larger efforts to keep Israel’s citizenry secure.72

Not long after Manna’s story was published in Posṭ Morṭem, Yesh won a com-manding majority of mandates to the Haifa University Student Union, earning thirty-two of forty seats on the SU council in March 1972.73 Though Israeli stu-dents tended to be apathetic about such elections, 40 percent of Haifa Univer-sity students participated in the 1972 Student Union election, as opposed to 27 percent in 1971 and 25 percent in 1975.74 Yesh’s victory did not last, however, as later in 1972 the group was ousted from power before its term was set to expire. Students affiliated with the Alignment and Ḥerut colluded to unseat a plurality of Yesh members in the student council by utilizing an obscure administrative regulation.75 Regardless, the sudden ascent of Yesh drew attention throughout Israeli society, as the unprecedented victory of a student faction seen by many as radical or “anti-establishment” was shocking to many. In contrast to the limited academic reforms pushed by Israeli students between 1967 and 1972, Yesh touted a comprehensive platform of social and political change.76 Many domestic observers saw Yesh’s intentions as revolutionary, and feared that it would foment a student uprising like that seen in Europe.77 Yesh’s victory also came as something of a surprise as right-wing parties were rising in other Is-raeli Student Unions in this period, and the independent student groups that had gained power in Israeli student government in preceding years advocated reforms strictly relating to academic affairs while Yesh promoted broad social and political changes within Israeli society.78

Yesh’s victory is reported to even have caught the attention of Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir, who allegedly reacted to the victory of Yesh by publicly announcing that their name should be eyn (the antonym of yesh), meaning “not to have” or “there isn’t.”79 Yesh was also subject to scathing attacks from multiple sources in the Israeli press and despite the diversity of its members, and the group’s self-proclaimed Zionist character, Yesh was mischaracter-ized blithely as being in league with Raḳaḥ (the successor to Maḳi and the main Israeli communist party at the time) and Matspen.80 Editorials in Yedi‘ot Aḥaronot and Al ha-Mishmar, two mainstream Israeli periodicals, criticized Yesh for its “communism” and accused it of flouting the “rules of the game.”81 Ironically, despite allegations that Yesh was allied with Raḳaḥ, the latter’s Ara-bic language newspaper, al-Ittihad, discussed the groundbreaking victory of Yesh with only a brief reference on the paper’s sixth page and later reported on the group’s downfall in a similarly cursory manner.82

Journal of Jewish Identities 44

Yesh Śmol ba-Ḳampus! The Triumphs and Tribulations of Two Left-Wing Student Union Factions in 1970s Israel

The rise of Yesh also prompted explanatory assessments from members of the student body. Eli Nahmias, a Haifa University student associated with the Alignment, blamed Yesh’s victory on the state for having failed to properly absorb recent immigrants.83 Shlomo Frankel, who succeeded Spiro as editor of Posṭ Morṭem, interpreted Yesh’s victory as the fruit of mainstream Israeli politi-cal parties’ excessive intervention into student politics. Frankel believed that the superficial partisan politicization of Israeli student organizations had led students to lose faith in the potential of the Student Unions to exert any real influence on student affairs, let alone on society at large.84 The triumph of Yesh also bothered at least one, and likely more than one, member of the admin-istration of Haifa University. Rector Benjamin Akzin sought to tarnish Yesh’s public image by generally accusing the student faction of being in league with the anti-Zionist Matspen, and specifically indicted Spiro for using Posṭ Morṭem as a pro-Yesh propaganda machine.85 Akzin’s accusations ring hollow when we consider Posṭ Morṭem’s inclusion of opinions from all sides of Israeli politi-cal debate, and Yesh’s official stance that, though critical of the Israeli socio-political status quo, fell well within the Zionist consensus supporting Israel’s right to exist as a Jewish state.86

Issam Mahoul was one of the Arab students in Yesh at the time of the 1972 victory and would later go on to become the chairman of the National Arab Students’ Committee in Israel, a leading figure in the Israeli far-left Ḥadash party, and later one of its representatives in the Knesset. He describes Yesh’s victory, despite its eventual reversal, as bearing deep symbolic and practical meaning for those involved:

You felt that you recreated what happened in Europe with the student rebel-lions in Haifa…[Yesh] did not deal with the questions of students as discon-nected from the questions of politics, there is no university politics discon-nected from the general politics and I discovered this the hard way. There was a strike with an automobile plant in Nesher, and the student newspaper and the whole protest of the workers—we would bring delegations there, we would bring the workers’ committee to make speeches to recruit the students of the university to lecture halls, you are already in a different place[,] you are already thinking in a different way . . . .87

Mahoul’s description reflects the way in which the students in Yesh sought to use the platform of the Student Union for activism that transcended the bound-aries of the university. In this way, Yesh may have pursued radical reform, but neither the later recollections of its members nor their statements at the time in-dicate that the groups sought to foment a revolution, as some claimed. Yesh thus represents a middle ground between the “revolutionary” activists of Matspen and Śiaḥ and the partisan “apparatchiks” who could commonly be found at the helm of Israel’s Student Unions. Recognizing the resilience of institutional power, as student movements elsewhere failed to do, the members of Yesh sought to use the privileges and rights afforded to them by active participation in the Univer-sity of Haifa Student Union to take down what they saw as an arbitrary barrier between university and society in order to promote meaningful change in both.

July 2015, 8(2)

Hillel Gruenberg

45

In contrast to the picture painted by its detractors, Yesh was not just a vehicle for the promotion of “left-wing” policies or alleged “anti-Zionist” be-liefs. Rather the group was intended as a platform for those in Israeli society who felt they had been overlooked, neglected, or exploited by an Israeli elite comprised of Alignment-affiliated Jews of European descent who failed to de-liver on the promises the State of Israel had made to all of its inhabitants. As opposed to groups like the Israeli Black Panthers, the Arab Students’ Commit-tees, or Śiaḥ, Yesh’s membership reflected a diverse cross section of Israelis including women, “veteran” leftist Zionists, immigrants, kibbutzniks, Pales-tinian Arabs, and Jews of Middle Eastern and North African descent. Yesh, according to Mahoul,

Was for anyone whose interest was different from the dominant interest…We won a great victory, we managed the newspaper, we had the stage, we man-aged the public relations of the Student Union… And then we saw the force of those opposing us, not just the administration of the university, not just the directorate and administrator etc., not even just the Ministry of Education, but when you hear on the day of elections that the prime minister calls upon the students to vote so that the left won’t rule over the University of Haifa and so that it won’t be a university of the enemies of Israel etc., then you realize that this must be important and is truly a significant endeavor.88

Mahoul carried the positive and negative lessons of his experience in Yesh into his later life, and put them into action as he worked to promote progres-sive policies from within an established institution as a Member of Knesset for Ḥadash, which was formed as part of an effort to create a wide Israeli left-wing alliance, including the non-Zionist Raḳaḥ and various smaller groups. In a limited sense, Yesh and Ḳampus were more successful than Ḥadash in building a broad and popular front of leftist Zionists, non-Zionists, and anti-Zionists, even if Ḥadash still exists while Yesh and Ḳampus have long since disappeared.89

In what was perhaps a demonstration of good faith and support for inclu-sive politics, leaders of Yesh appointed Arthur Cohen, a member of the Ḥerut-affiliated student cell, to chair the Audit Committee of the Student Union at Haifa University. Cohen worked with members of the Labor student cell to wrest control of the SU from Yesh months before its term was set to conclude. Citing an SU bylaw that mandated the removal of student council members who missed three consecutive meetings, the Herut and Labor students forced the resignation of fifteen of the thirty-two Yesh representatives, causing the latter faction to lose its majority on the SU council.90 Yesh members argued that the regulation used to unseat their faction was obscure; that the specific meeting of the council in which the group was voted out was not announced with forty-eight hours’ notice; and that many of their representatives had been absent because they were spending the summer away from Haifa, in their homes in distant villages, on kibbutzim, or even outside Israel, and were accordingly unable to travel to the university on a regular basis.91 A local court approved the campus “coup” while Yesh students claimed that they had not

Journal of Jewish Identities

Yesh Śmol ba-Ḳampus! The Triumphs and Tribulations of Two Left-Wing Student Union Factions in 1970s Israel

46

been given an opportunity to present justification for their absences as man-dated by the very regulation used to force their dismissal.92

Shortly after this affair, Yesh member Simone Ḥadad, who had just been elected to the position of Coordinator for Arab Students at Haifa University, was found guilty of espionage and treason as part of a Jewish-Arab militant cell uncovered in northern Israel. The group was associated with the Revo-lutionary Communist Alliance, an offshoot of Matspen popularly known as the “Red Front.”93 When the spy ring had been exposed in December 1972, Yesh issued a statement condemning all acts of violence and terrorism: “While there are differences of opinion about Israel’s government and policies, it is agreed from the outset that the existence of the State of Israel is not up for de-bate or negotiation.”94 Despite this affirmation of the group’s support for the security, legitimacy, and continued survival of Israel, the involvement of one of its Arab members in an espionage network prompted many of its Jewish members to leave the group.95

In the 1973 elections to Haifa University’s Student Union, the Alignment and Ḥerut cells ran on a joint list called Yaḥdav, meaning “together,” while members of several groups originally integral to Yesh—kibbutzniks, social-ist Zionists, and Jews of Middle East and North African descent—formed separate independent factions.96 Voting was suspended in the wake of a con-frontation, when Yesh members staged a sit-in protesting alleged electoral improprieties on the part of Yaḥdav students. In response, the university ad-ministration cancelled that year’s elections altogether, allowing the leaders of the Alignment–Ḥerut alliance to retain its hold over the SU for an additional year.97 As Yesh’s public image, already slandered by several sources on and off campus following its victory, was further tarnished by the association of one of its members with the Red Front, Yesh dissolved by the beginning of the following academic year.98

While Yesh’s time in the Haifa SU was short, the group demonstrated how students might use Israel’s establishment-sanctioned Student Unions as a venue from which to promote an agenda for wide-ranging social and politi-cal change. Yesh’s promotion of social responsibility among the students of Haifa University was evident in the unprecedented number of students who showed up to vote in support of the group, and was further reflected in the group’s advocacy for the rights of minorities, workers, women, and, of course, students. The student newspaper Yesh launched was unprecedented in its provocative and investigative approach.99 Through Posṭ Morṭem, and other initiatives undertaken during its short existence, Yesh elevated the level of on-campus debate at Haifa University, increased administrative transparency, and facilitated a critical discussion about Israeli society and Israel’s presence in the Occupied Territories.

While some have commented that the lasting achievements of the global student movements of 1968 were mainly in the realms of cultural symbolism and popular mythology, the same cannot be said about Yesh.100 Though its success prompted vociferous reactions from several corners in Israel, and de-spite the group’s promotion of greater student agency in Israeli society, Yesh

July 2015, 8(2)

Hillel Gruenberg

47

nonetheless seems to have mostly faded from historical memory.101 Unlike Śiaḥ or Matspen, which have merited some scholarly attention, Yesh has gone almost altogether unnoticed alongside the pervasive perception of Israel’s Student Unions as the facile playgrounds of tomorrow’s partisan functionar-ies. The group nonetheless serves as an example of how disparate groups in Israeli society might unite in their disaffection with the ruling elite and pursue a common goal.

Operating from within the Student Unions provided Yesh a useful insti-tutional foothold and led to its well-publicized conflict with rival student factions and even university administrators.102 Despite this and the group’s successful formation of a broad coalition of left-wing Zionists, non-Zionists, and anti-Zionists—to an extent never seen with off-campus Israeli leftist fac-tions—scholars have, by and large, overlooked Yesh. At the same time, observ-ers have paid greater attention to the “radical” students who formed the ranks of groups like Matspen and Śiaḥ on one hand and Israel’s politically quiescent student majority on the other. Despite the deep differences between these two groups, both possess symbolic value that has attracted the attention of schol-ars.103 , both The vast obsequious majority of students conform to widely held assumptions about the nature of the Israeli students who abstained from the spirit of protest that animated many of their global peers in the 1960s and 1970s. Similarly, the infinitesimal minority of Israeli students in groups such as Śiaḥ and Matspen represent an Israeli replication of Western “revolution-ary” left-wing movements. The students of Yesh, however, don’t fit neatly in either category. Instead, Yesh sought a middle ground and worked within the framework of a traditional academic institution to actively promote a message that was fiercely critical of the sociopolitical and academic status quo in Israel. And though right-wing factions were rising in Student Unions throughout the country in the first half of the 1970s (perhaps foreshadowing Likud’s 1977 victory in national elections), Ḳampus, a group similar to Yesh in its spirit and mission, emerged in the Student Union of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in 1974.

Ḳampus: Jerusalem 1974 and Beyond

The rise of right-wing parties in Israel’s Student Unions reflected simmer-ing popular discontent with the long hegemonic Alignment that accelerated considerably following the 1973 Yom Kippur War. Israeli Student Unions held elections with greater frequency than the Knesset, and are thus a prime venue for observing the spreading disaffection with the Alignment between the 1973 and 1977 national elections. At the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, a number of left-wing and independent alternatives to the Alignment student cell had sprung up even before the war; however, elections were cancelled in Jerusa-lem as they were in Haifa that year in the wake of disputes between students of opposing political camps.104 When elections were held the following year, those Hebrew University students seeking a platform for representation and

Journal of Jewish Identities

Yesh Śmol ba-Ḳampus! The Triumphs and Tribulations of Two Left-Wing Student Union Factions in 1970s Israel

48

action outside the traditional parameters of Israel’s Student Union or its parti-san political establishment formed a new organization called Ḳampus.105

In the 1977 Knesset elections, a number of former Alignment support-ers disinclined to vote for Likud turned to the center, casting their ballot for the nascent Democratic Movement for Change. In elections to the Hebrew University Student Union, however, many voters found an alternative to the Alignment not in the center, but further to the left, in Ḳampus.106 Ḳampus first proved its mettle in 1974 by gaining the backing of almost a third of students who voted in elections to the Hebrew University’s Student Union, receiving nine hundred votes while the Alignment student cell received only fifty.107 Ḳampus demonstrated its popular support again in 1975, when it won a plu-rality of votes cast. However, because of the electoral system by which rep-resentatives were allocated according to academic department, the left-wing faction earned the same number of mandates to the student council as the Likud-affiliated student group, Kastel, Ḳvutzat Studentim Leumi’yim (Group of Nationalist Students). Ḳastel took control of student government by allying with the faction representing religiously observant Jewish students, Yavneh.108 From its position of power, the Ḳastel leadership allotted Ḳampus only four out of thirty seats on the central council of the Student Union.109 Though it may seem unfair, the actions of Ḳastel and its allies were in line with the coalition-based approach that might give a bare majority total dominance over political life in Israel, both on and off the university campuses.110 Ḳampus, like Yesh, contended with smears and mischaracterizations in the press, both from its organized student opponents who warned against “The radical leftist, anti-re-ligious, and anti-nationalist group called Ḳampus,” and from journalists who alleged that it was essentially the student cell of the anti-Zionist Matspen.111 Ḳampus did, however, welcome members of the Arab Students’ Committee (ASC) into its ranks. Established in Jerusalem in 1958, the ASC was intended to serve as a vehicle of communal support and political advocacy for Arab stu-dents but was not recognized by the leadership of the Hebrew University or its Student Union. Ḳampus afforded Arab students a conduit through which they could be represented or even actively participate in student government without compromising their membership in the ASC.112

Ḳampus called for a “politicization of the campus” through public debates and discussions on campus about Israeli society and government policies.113 Ḳampus activists hoped that this would help counteract the socio-politically numbing effects of the long-practiced manipulation and cooptation of stu-dents via Student Unions by Israel’s major political parties. Ḳampus’ efforts to spread awareness about social and political issues were part of its larger objective of tearing down the walls separating the university from the rest of society. This goal was evident, for example, in the group’s demand that community service be integrated into the official curriculum of the university. Such ideals and aspirations are, at the very least, implicitly evocative of the “spirit of ‘68,” even if several years had lapsed between Ḳampus’s activity and the global student “uprising.” Moreover, it is not readily apparent that Ḳampus, like Yesh, counted so-called “sixty-eighters,” as the individuals who

July 2015, 8(2)

Hillel Gruenberg

49

participated in student protests in 1968 were known. Explicit references to the “revolution of 1968” and the recent “decades of global student activism” in Ḳampus’s publications from the latter 1970s, however, reflect how at least some of its members consciously drew inspiration from the most prominent examples of student activism in recent history.114

Ḳampus also struggled to increase student influence over university af-fairs, an issue that likely broadened the group’s appeal. By publicly and vo-cally advocating for the rights, responsibilities, and interests of students, Ḳampus might have attracted students who would otherwise be opposed or indifferent to its stances on controversial political and social issues. The He-brew University possessed something of a tradition of protest in support of student empowerment when we consider the struggle initiated by the stu-dents’ Likud in 1966 that eventually resulted in symbolic student representa-tion on a limited number of the Hebrew University’s administrative organs.115 Unlike groups that preceded them in the quest for increased student influence at Hebrew University, however, Ḳampus activists would not be content with symbolic gestures and limited concessions.

The group’s failure to gain the reins of student government limited its abil-ity to steer the official activities of Hebrew University’s student body. The student activists of Ḳampus, however, much like those of Yesh that preceded them, were not content to wait for the leadership of the university or its SU to put their agenda into action. In 1975, several delegations of Ḳampus students, echoing French students who reached out in solidarity with workers in 1968, visited port workers engaged in a wildcat strike in Ashkelon, and even met with the leaders of the strike who were hiding in order to evade arrest.116 The group also worked to set up their own “open university,” similar to the earlier versions in Haifa and the United States, with a curriculum they considered more relevant to students at the time, in both content and critical approach.117 The “open campus” program allowed students to shape the content and for-mat of their education and offered courses that were then unavailable at the university, such as “Select Problems in the Economy of Israel” and “Marxist Theory and Practice.”118

Beginning in July 1975, Ḳampus activists also took a leading role in protest-ing the administration’s decision to force mandatory guard duty upon Arab students residing in the dormitories of Hebrew University.119 Ḳampus wasted no time in announcing its support for those Arab students who refused to per-form guard duty. The student group openly acknowledged that the Palestin-ian identity of Israel’s Arab citizens and students was a matter of fact and not a political choice. It was because of the conflict between the civic and national identities of Palestinian Arab Israelis, Ḳampus publicly contended, that the state did not compel them to serve in the Israeli military, and the university had previously not required them to perform guard duty.120 After months of debate, the affair was resolved through the establishment of an alternative framework of service in January 1976, though a month later Jewish-Arab ten-sions on campus flared once again after the government announced plans to expropriate thousands of acres of Arab land. In the mounting opposition that

Journal of Jewish Identities

Yesh Śmol ba-Ḳampus! The Triumphs and Tribulations of Two Left-Wing Student Union Factions in 1970s Israel

50

led to the first nationwide strike of Arabs in Israel on March 30, 1976—now referred to as the first Land Day—Ḳampus publicly stood in solidarity with Palestinian Arab Israelis and organized protests together with the National Arab Student Committee.121

Though Ḳampus continued to make impressive showings in elections to the Hebrew University SU over the following years the group was repeatedly frustrated in its efforts to ascend to the leadership of the organization. Even af-ter it allied with Ma’as, the Alignment student cell, and won a sizable plurality of votes cast in 1977, the Student Union’s indirect electoral system frustrated Ḳampus’s quest for leadership of the Hebrew University Student Union yet again.122 On one hand, by participating in the Student Union Ḳampus recog-nized the reality of institutional power, avoiding, at least in part, a “fatal flaw of student activism.”123 On the other hand, the group’s failure to gain the reins of the Student Union left it with no capacity to alter the structure or policies of the Hebrew University or its official framework of student organization.

Conclusion

Yesh and Ḳampus transcended not only the conventional partisan param-eters of Israeli political culture but also challenged the traditionally restricted role of organized student activity in Israel. In contrast to the usual role of Israeli student leaders, the members of Yesh and Ḳampus did not limit their activity and public discourse to only those issues and policies that related explicitly to student affairs, such as tuition hikes or curricular content. Both groups fostered critical public debate about issues of broad sociopolitical concern through a variety of means including organizing protest demonstra-tions, facilitating extracurricular educational opportunities, and publicizing perceived injustices on and off campus. That the discourse and tactics of both Yesh and Ḳampus were often reminiscent of the “spirit of 1968” is plain to see, as they reached out in solidarity to working class activists, stood in defense of ethnic minorities, and loudly called for the rigid barrier dividing universi-ties and students from the rest of society to be torn down.124 Although most factions in Israel’s Student Unions in the 1970s served as lesser subsidiaries of major Israeli political parties, to which they were connected in all but name, Yesh and Ḳampus succeeded in using these organizational frameworks as a platform to publicly challenge the mainstream social and political consensus. In doing so, their members encouraged thousands of Israeli students to recon-sider Israel’s sociopolitical status quo and to rethink the limited role afforded to students in shaping Israeli society and higher education.125

By promoting their divergent views from within the state- and university-sanctioned Student Unions, Ḳampus and Yesh successfully used traditional institutional avenues of political engagement to spread their message to the students of their respective universities. The two groups interacted with audi-ences—the student bodies of the universities in which they were active—that were, by definition, more captive and concentrated than the general public,

July 2015, 8(2) 51

Hillel Gruenberg

and perhaps likelier to contain individuals more inclined towards left-wing sympathies than the general populace.126 At least in some sense, activity in established institutions rewarded the organizational coherence and ideologi-cal clarity that Yesh and Ḳampus possessed and Matspen and Śiaḥ lacked. Moreover, the popular followings of both Matspen and Śiaḥ were smaller than those of Yesh and Ḳampus, which reaped the benefits of the institution-al foothold they were afforded through participation in the Student Unions. However, despite their comparatively smaller ranks, scholars have paid much greater attention to Śiaḥ and Matspen than they have to Ḳampus or Yesh.127

Based as they were in Israeli Student Unions, both Ḳampus and Yesh have faded more quickly from scholarly and popular historical memory than left-wing groups like Matspen and Śiaḥ that were active mostly outside of institutional frameworks. Even though the latter groups had smaller popular followings, their symbolic value as Israeli manifestations of foreign “radical” or “revolutionary” movements appears to have made them a more attrac-tive subject for investigation. In retrospect, Yesh and Ḳampus do not appear to have exercised a readily discernible impact on the universities in which they were active and it would be difficult, if not impossible, to gauge with any certainty the extent to which their activities influenced the thinking of the students who comprised their target audiences. Ḳampus, like Yesh be-fore it, showed multiple Israeli “student generations” that the Student Unions could be more than mere training camps for future leaders of major political parties by providing spaces of political debate, protest, innovation, and, per-haps most importantly, “Jewish-Arab cooperation on a day-to-day basis.”128 Also, these student factions both constituted broad left-wing coalitions that remained “a relevant factor in the ideological and electoral aspects of student politics,” while the Zionist, non-Zionist, and anti-Zionist left-wing factions in national Israeli politics remained divided on the margins.129 It is also worth noting that though it was students associated with the Alignment who initi-ated the “Officers’ Letter,” widely regarded as the spark of Israel’s best known peace movement, Shalom Achshav (Peace Now), at least some members of Ḳampus were included among the signatories.130 In lieu of the extensive inter-views or documentary evidence that would be necessary to assert a stronger connection between Ḳampus and Peace Now, we can consider how Ḳampus may have helped foster an intellectual and political climate on a campus in which “348 students at the Hebrew University” were motivated to put their names on the “Officers’ Letter.”131

The student activists of Yesh and Ḳampus utilized Israel’s Student Union as a platform for asserting a new and expanded role for university students in the state’s social and political life. In doing so, they demonstrated new forms of political activity and advocated controversial positions to captive student audiences at their respective universities. Though neither group’s message was by any means positively received by all the members of a student body, their activities and their ideas were less easily overlooked than those of left-wing groups outside of the Student Unions. For many relieved Israeli observ-ers, the wave of student protest that washed over much of the globe in 1968

Journal of Jewish Identities 52

Yesh Śmol ba-Ḳampus! The Triumphs and Tribulations of Two Left-Wing Student Union Factions in 1970s Israel

seemed to have passed over Israel, aside from a negligible number of extra-parliamentary activists. However through the activities of Yesh and Ḳampus, many Israeli students did experience the “spirit of 1968” a few years late. Like the “individual actors and collective social movements which engendered ‘1968,’” the student activists of Yesh and Ḳampus “opened up possibilities that fundamentally questioned the social, political, economic, and cultural status quo.”132

At first glance, Yesh and Ḳampus do not seem like groups whose members are ripe for analysis in the context of Jewish student activism as the Jewish content of the groups’ programs is not readily apparent, and many of their members were not even Jewish! Shlomo Swirski provides a useful framework for doing so, however, in highlighting the Jewish-Zionist roots that informed the political activities of the Jewish members of Yesh.133 He interviewed sev-eral former Jewish members of Yesh and found that despite their different ethnic backgrounds and countries of origin, they shared a common inspira-tion for their activism in Yesh. The students all related that they were driven to activity in Yesh by their perception of a deep disparity between the idea of a Zionist utopia on which they had been raised, and the deeply unequal Jew-ish state in which they found themselves. If we assume that at least some of Ḳampus’s Zionist, and even non-Zionist, members were similarly inspired, this adds another dimension to our analysis of both student groups examined in this study. The members of Ḳampus and Yesh were not only student re-formers adapting the “spirit of ‘68” to an institutional setting. They were also agents of Jewish activism, seeking to refashion an Israel that they perceived as increasingly ethnocentric in the egalitarian vision of the Jewish State pre-sented to them as children, starting from the university and moving outward.

July 2015, 8(2) 53

Hillel Gruenberg

Endnotes

1 Ḳupat Ḥolim may refer to a health maintenance organization (HMO), or an individual clinic associated with an HMO, in the Israeli healthcare system; “Ḳampus—Daf la-Sṭudenṭ: Baḳbuḳim, Baḳbuḳim,” Ma‘ariv, February 1, 1970.

2 Rina Shapira and Eva Etzioni-Halevy, Mi Atah ha-Sṭudenṭ ha-Yiśraʼeli (Tel Aviv: ‘Am Oved, 1973).

3 Tamar Hermann, The Israeli Peace Movement: A Shattered Dream (New York: Cambridge Uni-versity Press, 2009); Sam N. Lehman-Wilzig, Stiff-Necked People, Bottle-Necked System: The Evolution and Roots of Israeli Public Protest, 1949–1986 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990); Sam N. Lehman-Wilzig, Wildfire: Grassroots Revolts in Israel in the Post-Socialist Era (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1992); Peretz Merhav, The Israeli Left: His-tory, Problems, Documents (San Diego: AS Barnes, 1980); Yael Yishai, Land or Peace: Whither Israel? (Stanford: Hoover Institution Press, 1987); Yael Yishai, Land of Paradoxes: Interest Poli-tics in Israel, SUNY Series in Israeli Studies (Albany: SUNY Press, 1991). For general expla-nations of the right–left continuum in Israeli politics, see Alan Arian, Politics in Israel : The Second Republic (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2005); Alan Dowty, The Jewish State: A Century Later (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001).

4 Gadi Wolfsfeld, The Politics of Provocation: Participation and Protest in Israel (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1988), 64; Yishai, Land of Paradoxes, 79–80, 119; Yishai, Whither Israel, 143, 147; Lehman-Wilzig, Stiff-Necked People, 35.

5 In Hebrew usage and the Israeli-political/legislative context, faction, si’ah, is frequently used interchangeably with party, miflagah. In contemporaneous writing about Yesh/Ḳampus, the term faction is used to refer to both groups at various times, in addition to terms such as group, movement (only Yesh), bloc (only Yesh), and list (only in the context of elections), and neither group is ever referred to by others or itself as a party. In keeping with this context, I use faction, which seems the appropriate catch-all term; for further explanation, see the en-try for Si’ah in Amos Carmel, ha-Kol Poliṭi: Leḳsiḳon ha-Poliṭiḳah ha-Yiśreʼelit (Lod, Dvir 2001).

6 In The Spirit of ’68: Rebellion in Western Europe and North America, 1956–1976 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), Gerd-Rainer Horn defines “the spirit of ‘68” according to the achieve-ments of the individuals and “collective social movements” that “opened up possibilities that fundamentally questioned the social, political, economic, and cultural status quo,” 231.

7 Adel Manna said that the name of the group was meant to imply that “there is [yesh] a way to peace, there is a way to equality,” interview with Adel Manna, Beit Berl, Israel, June 19, 2012.

8 Uri Cohen and Eithan Orkibi, “Ha-Profesurah ṿe-ha-Sṭudenṭim ba-Universiṭah ha-‘Ivrit 1967–1972,” Cathedra: For the History of Eretz Israel and Its Yishuv, no. 129 (September 1, 2008): 137–64; Lion Hadar, “Beyn ha-Mishṭaṭfim la-Agudah ha-Yerushalmit: ‘Memsadiyim’ ‘180 Ma‘alot’ ‘Ḥizḳe ha-Aton’ ṿe-‘Maṭaṭe,’” Ma‘ariv, March, 12, 1973; “Kenes Artsi shel Sṭudenṭim Ḳomunistiyim Ḳore le-Ma’avaḳ neged Ha‘alat Ś’char ha-Limud,” Zu ha-Derekh, February 18, 1976. Dan Gur of the of the Labor Party’s Arab Department told Shmuel Toledano, the Prime Minister’s Advisor for Arab Affairs, about a Jewish-Arab student group called “The Sons of Shem” in a report on “Student groups at Tel Aviv University in 1971,” June 29, 1971, Israeli Labor Party Archiṿe-2-926-1971-189.

9 According to available sources, the number of students who voted for Yesh and Ḳampus in most of the Student Union elections in which they participated in the 1970s was greater than the number of people believed to have belonged to Śiaḥ (which numbered around 500 members at its peak) and the followers of Matspen and its offshoots (which were likely even smaller in number),Adi Portugheis, “T’nuat Śmol Yiśra’eli Ḥadash: Śmol Ḥadash be-Yiśra’el,” Yiśra’el, K’tav ’Et le-Ḥeḳer ha-Tsionut u-Medinat Yiśraʼel--Hisṭoriyah, Tarbut, Ḥevrah 21 (2013): 225–52. Relative to the electoral arena in which they were competing, Ḳampus and Yesh fared far better than the party lists in which Śiaḥ and Matspen members were included in the 1969, 1973, and 1977 Knesset election. For election results in relevant years see: Shimon Rappaport, “‘Hamahapakh’ ba-Universiṭat Haifa Hevi le-Nitsaḥon Reshimat ‘Yesh,’” Ma‘ariv, March 13, 1972; “Heseg le-Lo Taḳdim be-Toldot ha-Universiṭa’ot be-Yiśra’el: ha-Śmol Zakha be-Nitsaḥon Moḥets,” Posṭ Morṭem [Haifa University Student Newspaper], May 9, 1972; “Likud–37, Śmol–37, Yavneh–19,” Pi ha-Aton [Hebrew University Student Newspaper], May 21, 1975; “Ṿe‘idat H.H. Nidḥata le-Shavu‘a ha-Ba,” Pi ha-Aton, June 16,

Journal of Jewish Identities 54

Yesh Śmol ba-Ḳampus! The Triumphs and Tribulations of Two Left-Wing Student Union Factions in 1970s Israel

1976; Campus, “Summary of Student Association Elections for CAMPUS Activists,” June, 1977 Israeli Left Archive (ILA), accessed September 9, 2013, http:// israeli-left-archive.org/greenstone/collect/ campus/index/assoc/ HASH0178.dir/770601.jpg. While I transliterate the name of the group as Ḳampus, in accord with the Library of Congress guidelines, it appears as “CAMPUS” on the ILA website. Though most material from the ILA is in Hebrew, my citations refer to the English language titles of documents as they appear on the ILA website.

10 For election results and left-wing representation from relevant years see: http://main.knes-set.gov.il/mk/ elections/Pages/ ElectionsResults9.aspx; http://main.knesset.gov.il/mk/elec-tions/Pages/ ElectionsResults8.aspx, accessed July 5, 2014. For student election results in relevant years see note 7.

11 Groups including Matspen and Siah have are mentioned at least briefly in much of the pub-lished research on Israeli politics, including that cited in notes 3 and 4, and have been at the focus of a number of works including: Nitza Erel, Matspen: ha-Matspun ṿe-ha-Fanṭazyah (Tel Aviv: Resling, 2010); Nira Yuval-Davis, Matspen: Ha-Irgun Ha-Sotsiʼalisti Be-Yiśraʼel, Mehkarim Be-Sotsyologyah (Jerusalem: Hebrew University, Department of Sociology, 1977); David J. Schnall, “Native Anti-Zionism: Ideologies of Radical Dissent in Israel,” The Middle East Jour-nal 31.2 (Spring 1977): 157–174; Ehud Sprinzak, Nitsane Politikah shel Deh-legitimiyut be-Yiśraʼel 1967–1972 (Jerusalem: Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1973); Adi Portugheis, “T’nuat Śmol Yiśra’eli Ḥadash,”; David J. Schnall, Radical Dissent in Contemporary Israeli Politics: Cracks in the Wall (New York: Praeger, 1979). Virtually all published references to Yesh and Kampus (most of which are short and many not entirely accurate), on the other hand, can fit in this note, Shlomo Swirski Ḳampus, Ḥevrah, u-Medinah, ‘al Toda’ah ha-Politit shel Sṭudenṭim be-Yisra-el (Je-rusalem: Mifrash Publishing House, 1982). Erel, Matspen, Sprinzak, Nitsane Politikah; Ḳantsler, Ha-Śemolanut Be-Yiśraʼel : Inṭeligentsyah bi-Sevakh ha-Nikur (Tel Aviv: Otpaz, 1984); Shapira and Halevy, “Israel,” in Philip G. Altbach, Student Political Activism: An International Reference Handbook (New York: Greenwood Press, 1989), 135n1; Motti Regev, “Sof ’Onat ha-Tapuzim” in Te’oriyah u-Biḳoret (1999): 252, 254, 256; Portughies, “T’nuat Śmol Yiśra’eli Ḥadash,” 247–48; Sami Shalom Chetrit, Intra-Jewish Conflict in Israel: White Jews, Black Jews (New York: Routledge, 2010), 163; Reuven Kaminer, The Politics of Protest: The Israeli Peace Movement and the Palestinian Intifada (Brighton, England: Sussex Academic Press, 1996), 28–9.

12 See note 4.13 “Du-Śiaḥ Profesorim be-Beit Ma‘ariv: Lamah lo Nis-ḥaf ha-Student ha-Yiśraʼeli be-Galei

‘Mered ha-Sṭudenṭim’,” Ma‘ariv, July 26, 1968. 14 Tsvi Magan,“P’nei ha-Sṭudenṭ ki-P’nei ha-Dor,” Davar, October 10, 1969; Professor Yeḥezkel

Kutsher, “Professor Yigael Yadin—ṿe-ha-Sṭudenṭim be-Amerika v-Yiśraʼel,” Ma‘ariv, Octo-ber 30, 1971; “Students in Israel Protest,” Journal of Palestine Studies 1.4 (Summer 1972).

15 Shapira and Halevy, Mi Atah, 34n3. 16 Letter from Dean’s Office to the Arab Students’ Committee, October 16, 1974, Central Ar-

chive of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem-3501-1974-5; hereafter HUA. 17 See note 10. 18 See notes 3, 4, and 10. It should be noted that this study serves an initial inquiry into two

Israeli Student Union factions that, along with similar groups that may have existed, de-serve further investigation. In addition to contemporaneous Israeli periodicals, this study draws on archival resources from a number of Israeli archives, and the internet-based ILA. I initially consulted the university archives in Haifa and Jerusalem while researching the related subject of Arab university students in Israel in after 1967, before approaching the topic at hand. Accordingly, I have no doubt that the archives of these and other Israeli uni-versities have more material and insight to offer than the present work provides. The ILA is an extremely useful source of information about Ḳampus, though it should be noted that former left-wing activists who were involved in some of the groups discussed in this article established the database, and the materials contained in it may accordingly suffer to some degree from selection bias. Ascertaining more than a few of the personalities who drove the groups discussed in this study proved rather challenging, as the groups are often discussed in a collective sense in both archival and periodical records, and it is unclear if any member-ship rolls are still attainable, if they existed in the first place. While there is certainly room for further investigation into groups like Yesh and Ḳampus, and the students who comprised their membership and leadership, this study is a first step in shedding light on two groups that have largely evaded scholarly attention.

July 2015, 8(2) 55

Hillel Gruenberg

19 A good general description and analysis of changes in Israel after the wars of 1967 and 1973 can be found in Joel S. Migdal, Through the Lens of Israel: Explorations in State and Society (Al-bany, NY: SUNY Press, 2001), Chapter 7.

20 Arian, Politics in Israel, 107–8.21 Rael Jean Isaac, Israel Divided: Ideological Politics in the Jewish State (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins

University Press, 1976); Hermann, The Israeli Peace Movement; Lehman-Wilzig, Stiff Necked People; Wolfsfeld, The Politics of Provocation; Migdal, Through the Lens of Israel.