1 Wooden Boatbuilding: Not a Dying Art - Phil Renouf Lecture, Australian National Maritime Museum 21 March 2013, By John Young I never had the privilege of knowing Phil Renouf, so when I was asked to give this talk in his honour, I googled him. And I was delighted to find that he came to the Australian Wooden Boat Festival in Hobart in February 2001, then set out southwards on a nostalgic pilgrimage, through Franklin, on the Huon River, where I live, and on to what he described as a “Sacred Site”, Recherche Bay in the far South of Tasmania, where your famous flagship, James Craig lay derelict until February 1972, when Alan Edenborough decided that it would be possible to salvage her and triggered the long process that led to her total resurrection, 30 years later, over which Phil Renouf presided. Recherche, or Research as we call it in Tasmania, is also the starting point, every two years since 2007, for another kind of pilgrimage, in open wooden boats, known now as a “Raid”. It consists of nine days of rowing, sailing, camping and learning in company, on a passage towards the Wooden Boat Festival in Hobart. This is what it looked like last month. [Photo 1: Raid start 2013, Richard &Jill Edwards.]

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

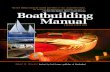

1

Wooden Boatbuilding: Not a Dying Art - Phil Renouf Lecture,

Australian National Maritime Museum 21 March 2013,

By John Young

I never had the privilege of knowing Phil Renouf, so when I was asked to give

this talk in his honour, I googled him. And I was delighted to find that he came

to the Australian Wooden Boat Festival in Hobart in February 2001, then set

out southwards on a nostalgic pilgrimage, through Franklin, on the Huon River,

where I live, and on to what he described as a “Sacred Site”, Recherche Bay in

the far South of Tasmania, where your famous flagship, James Craig lay

derelict until February 1972, when Alan Edenborough decided that it would be

possible to salvage her and triggered the long process that led to her total

resurrection, 30 years later, over which Phil Renouf presided.

Recherche, or Research as we call it in Tasmania, is also the starting point,

every two years since 2007, for another kind of pilgrimage, in open wooden

boats, known now as a “Raid”. It consists of nine days of rowing, sailing,

camping and learning in company, on a passage towards the Wooden Boat

Festival in Hobart. This is what it looked like last month.

[Photo 1: Raid start 2013, Richard &Jill Edwards.]

2

[Photo 2: Fleet tied up at night in Waterman’s dock, Richard &Jill Edwards.]

I began to think about the parallel history of two international social

movements, the restoration of “Tall Ships”, and the re-birth of wooden

boatbuilding and this led me to recognise Phil Renouf as a kindred spirit,

because these movements have a lot in common. They grew up together, and

both of them have helped to make the world a better place.

Let’s start with how things were towards the end of the last century. On 23rd

September 1987, Britain’s Prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, was interviewed

for Woman’s Own magazine: “Who is Society?” she asked, and she answered

her own question, “There is no such thing! There are individual men and

women, and there are families.”1 This was also the year of the film Wall Street,

in which the Gordon Gekko character declared that “Greed is Good”. That

wasn’t really what Adam Smith meant, but it neatly summarised the dominant

1 www.margaret.thatcher.org/document/106689

3

economic philosophy of the late 20th century. Credit cards, made of plastic,

became the currency of an increasingly indebted society. And mass-produced

boats, made of fibreglass, became popular consumer items.

Most people believed that Wooden Boats were things of the past. John

Gardner himself, a leading champion of American wooden boats, declared in

1992 that

The custom built yachts of a couple of generations ago are extinct. I

don’t believe anyone will take issue with this. I don’t see how anyone

could.”2

But while history has its mainstreams, it also has significant counter-currents

that run in an opposite direction. Like underground creeks they surface

unexpectedly at times because their sources have never been destroyed. They

irrigate our minds with alternative possibilities. And they energise

communities.

Two years after the decision to restore James Craig was made in 1974, a young

man called Jon Wilson sat down in his log cabin in the woods of Maine, USA,

next to his telephone, which was nailed to a tree, and wrote the editorial for

the first issue of WoodenBoat magazine:

For those doomsayers who might wonder just how long a magazine on

wooden boats could possibly survive, it seems fitting to remind them that

wood , is after all, our only renewable construction resource, a factor of

considerable importance at this time of diminishing supplies in other

fields.3

Jon was right, but it was never that simple. The 1973 oil crisis didn’t turn out to

be terminal as many expected. Wars over the planet’s oil supplies lay in the

future, but it remains as true now as it was then, that the resources on which

fibreglass, steel, aluminium and epoxy depend are finite. Converting finite

natural resources into building materials requires huge amounts of energy and

creates pollution. Wood is renewable. It cleans the air while it’s growing, and

2 WoodenBoat, No.115, 1992, p.44

3 WoodenBoat No.1, September/October 1974, p.2

4

stores carbon even when it’s part of a boat. Boatbuilders who use it can, if they

choose, take their place in the queue of other creatures, from eagles to

microbes that participate in the natural forest process from mature tree to

habitat for a range of animals, including humans, to soil, to new trees. Our

modest intervention temporarily interrupts this process by slotting in a bit of

boatbuilding, carbon storage, sailing and a huge amount of human well-being

along the way. Using even the earth’s best and rarest timbers can be an

ecologically sustainable activity if we are content to live off the interest of the

forest without damaging the capital.

I think this was why those slightly folksy early issues of WoodenBoat are

historically important. They document the mood of a generation which sensed,

in the aftermath of the Vietnam War, that all was not right with the ideologies

of industrial society, and wanted something more emotionally satisfying and

philosophically re-assuring. Building wooden boats became a way of doing well

by doing good. As Jon Wilson put it in each issue during the magazine’s early

age of innocence:

Re-cycle WoodenBoat. If you don’t want to keep it, give it to a friend. If

you can’t find a friend, let us know. We’ll find you one.

And he and his multiplying staff did better and better the more good they did.

Circulation grew steadily to over 100,000 by 1997, when a reader survey was

published that revealed the market power that this astute hippy movement

had created. Average annual incomes of WoodenBoat subscribers were

$97,000 US Dollars, and 28% of them expected to acquire a new boat within

the next twelve months.

More publications soon appeared that provide evidence of an expanding

international industry which caters for people of all income levels who want to

build or own boats which express their own individuality. Classic Boat followed

in Britain, then The Boatman and Watercraft, Chasse Marée in France, the

Franco-American Maritime Traditions and our own Australian Amateur

Boatbuilder, all of them dealing mainly with wood.

Ironically, the advent of epoxies contributed to the re-birth of natural timber

boats. Once seduced by the simplicity of building in plywood, a significant

5

proportion of backyard builders got confident and graduated from plywood to

natural timber. I was one of them. We were supported by splendid new books

by people like John Leather, Michael Verney, Larry Pardey and Bud MacIntosh,

who taught us to build wooden boats that could take us across the oceans of

the world if we wanted to go there, and lots of us did.

[Photo 3: Leofleda getting built, John Young.]

[Photo 4: anchored off Vatoa, John Young].

Wise people with adequate incomes created a market for a new generation of

professionals, and new schools, as well as traditional apprenticeships, began to

pass the trade on to a new generation of men and women.

6

It’s also interesting to note the increasing level of sophistication with which

the Editors, contributors and readers of the new publications discuss the ethics

of using wood, and their growing preference for their own local timbers or

timber guaranteed to come from ecologically sustainable sources.

The wooden boatbuilding revival spread quickly to the shores of Australia, and

it was boosted by the preparations that were made in every state for the

various sesquicentenary celebrations of the 1980s, and the national bi-

centennial celebrations of 1988.

A key event was the First Fleet Re-enactment, which never enjoyed the

support of the Australian Government, but stole the show on Sydney Harbour

on Australia Day. Some of the ships, from other countries, as well as Australia

were built of wood, and the event was preceded and followed by a national

flurry of wooden ship-building and restoration.

[Photo 5, One and All in Sydney]

7

Photo 6, general view of the Harbour 26/1/1988, Noni Howard]

In Tasmania, the Lady Nelson replica was built by Ray Kemp with a lot of

volunteer assistance. In Victoria the wooden fruit schooner, Alma Doepel was

restored for another twenty years of useful life. In Western Australia they built

Leeuwin out of steel, but then got inspired by the replica movement, and

started work on Cook’s Endeavour, which took a decade to complete. Then

they went on to build Duyfken.

In South Australia a community association, The Jubilee Sailing Ship Project Inc

was formed in 1980 to build One and All, a wooden Sail Training ship for young

people, just in time to join the First Fleet Re-enactment.

In Queensland, they restored Golden Plover, in Victoria they built Enterprise,

and Tasmania followed Lady Nelson with Windeward Bound and Norfolk, the

vessel that circumnavigated the island like her original, without an engine, in

2002.

These projects defied conventional wisdom, especially the early ones.

Bureaucrats and politicians usually condemned them to begin with as

unrealistic. They had come to believe by about 1980 that the skills required to

8

build or restore large wooden vessels had been lost from the community, that

the timber they needed could not be had, and people who started the projects

had to get used to being patronised as “dreamers”.

This had an important effect on the nature of these social enterprises. To build

a large steel, fibreglass or aluminium vessel, you need an industrial shipyard to

even think about it. Wooden Ships can start without a lot of money to begin

with. They can be built on a beach if need be, as they often were in the past.

They generate strong loyalties and become identified with local communities.

The story of South Australia’s One and All is typical of the process. She carries

the name of a ketch built at Cygnet, Tasmania in 1878 that came to South

Australia in 1898 and traded under sail til 1970.

[Photo 7: original One and All under sail, Edwardes Collection, State Library of

SA]

I started a South Australian Ketch Preservation Society to bring her back to life

as a school ship for my history students, but we lost her to Sydney and she

sank. The impending sesquicentenary of South Australia in 1986 looked like an

9

opportunity to build a new ship instead, so I formed a Jubilee Sailing Ship

Association to do it.

We soon became involved in State Politics. Our proposal was initially

welcomed, and we went through the process of business plans and grant

applications in expectation of Government support. Then we were suddenly

asked to drop the name we had chosen, because the State Government had

decided to fund an alternative proposal instead, the restoration of Falie, a steel

auxiliary motor ship, built in Holland in 1912 and brought to South Australia to

join the fleet of mostly Tasmanian built wooden ketches that constituted the

Grain Fleet. It was thought that steel would outlast wood, and be a more

reliable investment of public money.

Sir James Hardy accepted our invitation to become our President, just before

his knight hood was bestowed. But now he was asked by the chairman of the

Jubilee Board to jump ship, and head up the Falie project. Jim rang me next

day and told me how he had explained that he would “prefer to stay with the

Jubilee Ship”. He said, “I think she’ll go better to windward.”

We began serious fundraising, talking to service clubs to plead for donations,

radio and TV interviews and press releases, printing windcheaters to sell, and

barbecues and working bees. We also applied to the Federal “Wage Pause”

Employment Program, and were successful in getting a seeding fund of

$150,000 towards an eventual cost of $3 million. We spent some of the first

instalment on establishing a fund raising unit, with a crew of two, and a mobile

shop on a trailer, built by the students of Mt Barker High School, and their

teacher, Robert Ayliffe, who went on to become South Australia’s wooden

boat Guru, editor of Australian Amateur Boatbuilder, and founder of the

Goolwa Wooden Boat Festival.

Our grant was followed by a more substantial sum from the Community

Employment Program. The Falie project followed our example and applied for

a Community Employment grant as well, and got it, which was great for South

Australia at a time of high unemployment. With sponsorship in kind from

National Rail to haul timber from interstate, and TAA to enable our designer,

10

Kell Steinman to visit us regularly, and the appointment of Bill Porter as our

builder, we were ready to lay the keel at a public ceremony in October 1982.

Frosty relations with the Falie organisation soon thawed, and when the right

time came, soon after planking started, we elected Trevor Copeland, one of

our trainee shipwrights, to captain our cricket team. He visited the Falie yard

and threw his glove down before the feet of project leader Andrew Canon, as

a challenge to a match for the Shipwright’s Plate, donated by the landlord of

the Britannia hotel in Port Adelaide.

One and All batted last, and it was not until there was one wicket to go, and

one run to get, that Brian Baldwin, who had developed nerves of steel as our

Treasurer, scored the winning run. The building site between the road and the

beach, donated by the builders of the Northhaven Marina, began to attract

what became a continuous stream of supporters, seven days a week until we

launched the hull in December 1985.

Commonwealth funding was continued. John Bannon and his State

Government had become firm supporters by now, and at 6 am on a Sunday

morning, when the tide was high, a week before a State election, there were

10,000 people on the beach to see One and All take to the water. The Premier,

luckily an experienced marathon runner, had to leave his car half a mile away

and run past the growing crowd to get there in time to make his speech.

It took until 1987 to get her finished, just in time to join the First Fleet Re-

enactment at Rio on the way back to Sydney. Financially, it was a very close

run thing, and if it hadn’t been for the support of Dick Fidock and Malcolm

Kinnaird who succeeded me as Chairmen, the State Government, Port Adelaide

Council, Jonathan King, organiser of the First Fleet Re-enactment, and the

South Australian community, all of whom provided financial support, she

would not have made it. Since then she has served her supporting community

with distinction by providing sail training experience for thousands of young

South Australians, and professional experience for a new generation of

qualified masters, mates, riggers and watch keepers who have kept Australia’s

growing fleet of Tall Ships sailing and in good condition. Sadly, Falie is no

longer in survey, as her plates are no longer thick enough, and she is laid up.

11

These 1980’s projects changed the way people felt about wooden ships. The

justification for ship preservation used to be that they were living documents

of construction methods of the past. Now we have gone beyond that with a

new generation of young men and women who have learned how to build, rig,

sail and maintain long lasting vessels using natural timbers. If the art is

preserved and forests are sustainably managed we can build new ships and

restore old ones for as long as we want to. The old claim that no one knows

how to do it anymore has lost credibility.

As you might expect, social movements on this scale have significant impacts

at different levels: on individuals who participate directly, on communities and

at national level.

Let me start by giving you an example of the impact of the wooden ship revival

on an individual person.

David Nash, sixteen years old, started an apprenticeship with a boat building

company in Port Adelaide that closed in 1981 and laid him off, just as we felt

able to start lofting Kell Steinman’s design for One and All.

We had no money, and Bill Porter, our Shipbuilder, had a yard to run in Port

Adelaide, but he met a retired loftsman, Jock Geddes, who had worked at a

shipyard in Glasgow for most of his life, so Bill asked Dave to volunteer to do

the lofting with Jock, and make the moulds from radiata pine, donated by the

Woods and Forests Department. It took them six months. By that time we had

secured the wage pause funding from the Commonwealth and Dave started

getting paid as our first apprentice.

When the ironbark keel was sent by National Rail for free, from Kyogle in New

South Wales, it was his job to go down, every morning at 7.30 am while a

donated shed was being built around it. The aft half of the timber was held

down on a concrete slab by bolted steel brackets so that a three foot rocker

could be slowly achieved by jacking up and wedging the bow end of it over

many weeks. David soaked the keel timber with repeated applications of raw

linseed oil and took a turn or two with the jack at the for’ard end, every

morning until the correct curve was achieved.

12

[Photo 8: Dave Nash and the keel, A touch of Magic: Young, John, The Building

of the One and All, Jubilee Sailing Ship Project Inc., 1984, Adelaide, p.11]

David completed his apprenticeship with One and All four years later, sailed to

Britain as a crew member of Bounty, then headed for Denmark to gain further

experience as a shipwright. Now he has published an account, in WoodenBoat

magazine last year, of how he heard of Yukon, an old wooden ship, 65 feet on

deck, built in 1935, lying on the bottom of a harbour, waiting to be rescued

from the worms. He bought her for a case of beer, borrowed money, and with

the girl who is now his wife and the mother of his children, and a group of

good friends, he raised the ship and rebuilt her over a seven year period.

Dave and Ea ran a charter business in the Baltic, and then sailed with their

young family back to Australia. Yukon was the mother ship for the Raid last

month and she’s now tied up in Franklin. Dave is planning a tourist business

with his ship. Ea, is a qualified social worker, now a youth co-ordinator for a

13

community centre in Geeveston. The two boys, Kristopher and Aron, are at the

stage when they need friends of their own age, and they are going to Franklin

school.

[Photo 9, Yukon as mother ship, Richard & Jill Edwards]

[Photo 10, Yukon under sail, Richard & Jill Edwards]

14

The global revival of wooden boat building in the last 30 years has affected

communities as well as individuals all over the world, and Franklin is one of

them. I first saw Franklin in 1987 after coming to Tasmania for a conference on

environmental politics at the University. I borrowed a car to visit Cygnet,

where the original One and All was built in 1878 by the Wilson brothers.

But I missed the turning to Cygnet and went on across the Huon River and

down the western side of it. By the time I realised my mistake I was already

entering an extraordinary narrow street at the northern entrance to Franklin,

founded by Jane, Lady Franklin, in 1838. In 1912, Franklin’s population was

765. It’s now around 360. To my left was the empty river, not a boat to be

seen, and a row of six timber cottages right in front of me was in the process of

demolition. Yellow machines tore at them like hungry sharks. In the pub at the

southern end of the town I asked why no one had chained themselves to the

cottages to save them from what struck me as an act of vandalism. I was told

the road had to be widened for the log trucks: they were having to slow up too

much.

[Photo 11: Photo of North Franklin, Eye in the sky]

15

Franklin wasn’t looking too good then. Shop fronts were boarded up. Paint

peeled from houses that were up for sale. Litter blew down the street, but half

a kilometre further on there was an old orchard property for sale, right next to

the river. Most of the trees had been bulldozed into heaps and burnt after

Britain joined the European market in 1970, and the apple industry re-

discovered the instability of a dependent economy for the third time.

Now , following the decline of the apple industry, the forest industry had

switched from producing timber, with a woodchip by-product to a woodchip

industry with a timber by-product. Small saw mills were closing. Large scale

industrial logging and over investment in heavy machinery led to recurrent

debt and unemployment. Young people were leaving to look for work on the

Mainland. The house, together with 50 acres of mature re-growth forest was

going cheaply. Back home in Adelaide, I told Ruth, my wife, about it and she

went to have a look for herself. We bought it, found people to live in it, and

began to visit Franklin to do it up when we could, and plan for an eventual

move in 1991 when our children were grown up.

It was impossible not to suspect that Franklin had once been a busy port at the

head of tide-water navigation, and could be again. A little research soon

verified the suspicion. An “Old Resident” who didn’t identify himself, wrote a

letter to the Hobart Mercury in 1923:

It must not be assumed that even fifty years back, [i.e. in 1873] ,that

Franklin was the proverbial one-horse village. It was really a thriving

community, for ship-building was carried on so extensively that the clang

of hammers from the building of several vessels at the same time lent an

air of importance to the place and caused it to be regarded as a hive of

industry.4

The writer went on to list the several shipyards that once occupied the sites at

the northern end of town: Cuthbert , Griggs, Hawkes, and Thorp. It was here

that Alexander Lawson built May Queen in 1867, eventually owned by the

4 Huon Times 26

th January 1923

16

Chesterman family of Hobart, where she remains as a stationary museum

piece.

With the removal of the six cottages in 1987, the Crown land between the road

and the river, once full of shipyards, soon became an urban wilderness of

snakes and weeds, sodden in winter and dusty in summer.

By this time Ruth and I had moved to Franklin and established a modest school

of wooden boatbuilding in an old boatshed, at Shipwright’s Point. We ran

Skillshare courses for the long term unemployed, and recreational courses for

grown-ups who wanted to build their own boats, and groups of children and

parents who built dinghies, financed by Huon Valley Council’s youth service.

Some of our Skillshare students told us that a recognised trade qualification in

wooden boatbuilding would be a good thing to have, so we spent a year in

1994 becoming a Registered Training Organisation and devising a two year

Level 5 Diploma in Wooden Boatbuilding.

We found that the site at Port Huon could not be expanded so we applied to

lease crown land where Cuthbert’s shipyard had been in Franklin, and re-

erected a wooden shed we got from the demolition of the Hydro village at

Tarraleah in the central Highlands. This enabled us to accommodate ten

students for two years at a time. We kept the Port Huon workshop and slipway

for teaching repair and maintenance.

A man called Bill Cromer dropped in one day to discuss getting our students to

build a thirty foot yacht for him and took a shine to a design by Eric Cox of New

Zealand. Soon, other people asked us to build a series of Lyle Hess cruising

yachts for them. Retired shipwrights like Adrian Dean and Bill Foster, naval

architect Murray Isles and other professionals welcomed the chance to pass on

their skills. I was only an amateur boat builder so I took the opportunity to

become a mature age student myself, until I felt confident enough to start

teaching in the clinker dinghy department.

Most of all, we depended on our students, men and women from Tasmania

and other states, the United States, Britain and Japan, who were a constant

delight. Some brought their families. They included some of the best

professionals of the present, like Mark Singleton, Chris Burke, and Ned

17

Trewartha, Cody Horgan, Doug Watson and Brendan Riordan, who went back

to Maine to work as a designer/shipwright for Rockport Marine. And they

made a big collective contribution to the social and sporting life of Franklin.

Initial recruitment would have been difficult if it had not been for another

important component of the international wooden boat revival: Wooden Boat

Festivals. Andy Gamlin, Ian Johnston and Cathy Hawkins followed the lead of

Newport, USA and Brest in France and established the Australian Wooden Boat

Festival as a bi-ennial event in Hobart.

Ordinary boat shows around the world are simple exercises in salesmanship.

Wooden Boat Festivals are different. They have their roots in local history.

They are celebrations of regional culture, and the diversity of wooden boat

building and design all over the world. They include music, sculling races, food

and drink, boatbuilding demonstrations, public lectures, discussions, plays and

art shows.

Hobart’s first wooden Boat festival in November 1994 attracted a hundred

boats, mostly from Tasmania. By the fifth one in 2003, the number of boats

had risen to 300 from all over Australia and some from abroad. In 2007 there

were 620 boats. Someone must have been building and restoring them, which

testifies to the growth of a sizeable industry. Visitor numbers rose from 10,000

or so in 1994 to over 150,000 in 2011, and over 200,000 in 2013.

For the Boat School, the timing of the first Hobart Festival was great. We

recruited our first seven students at the show, in two days. After that we relied

mainly on word of mouth, but also got applications from overseas and the

other states of Australia through WoodenBoat magazine.

In 1991 Franklin Progress Association volunteers restored Franklin’s old public

wharf as a means of keeping forestry contractors occupied when they lost their

jobs because of the final closure of the pulp mill at Port Huon. It was also a

statement about Franklin’s history as a working port. Visitors began to arrive

by water, and boats anchored once more in the river, providing more to look at

for visitors driving past the empty houses. New people began to take

advantage of the low prices to settle in the area, and the near derelict Palais

18

Theatre began to be used. Soon volunteers began renovation to postpone, and

in the end, to remove the threat of demolition.

The boatbuilding Diploma included a module on small business management,

and students were asked to do a business plan for the first five years of their

lives after finishing the course. Many planned to build boats, but Chris Burke,

and his wife, Pip, planned to establish a community association, functioning as

a working museum of traditional seamanship, restoration and boatbuilding.

They called it The Living Boat Trust.

We thought it was such a good idea that we encouraged them to actually do it,

and in Franklin, where there was vacant land and where it was needed.

While Chris was still a student, they applied for a Crown lease for the land

adjoining the Boat School, and drew up a constitution. Another student, Grant

Wilson, went over to Christchurch, New Zealand to get permission for the Trust

to build a replica of Swiftsure, the last surviving Tasmanian whaleboat in the

world, built in 1860, but sold to New Zealand in 1863, and donated to the

Canterbury Museum at the end of her career in 1915.

Grant brought the plans back, with detailed notes, and soon, a temporary

workshop with a plastic roof was erected next to the Boat School and students

from Geeveston High School began construction, supervised by a sequence of

Boat School graduates and local boatbuilders.

With the approach of the centenary of Australian Federation, the Franklin

Progress Association, now infused by a new generation of recent arrivals from

interstate, joined the Boat School and the Living Boat Trust in a joint

application for Federation funding to build a Community Boat Harbour, which

was eventually opened by our local members of both state and federal

parliaments on 24th March 2000.

By then Ruth and I were ready for a second retirement and we sold the School

to a local community association and employment provider. Chris Burke

became a teacher of the School in 1998 and then got a contract to build a 32

foot Lyle Hess cruising cutter. This meant moving house and devoting his

whole being to what he was doing.

19

That put me and Ruth in the frame to kick -start the Living Boat Trust. I was

soon working full time again, as volunteer labourer for local builder Kevin

McMullen, erecting the Living Boat Trust workshop .

In 2003, Swiftsure II moved into the new shed, where she attracted increasing

numbers of volunteers, every Monday night, led by a sequence of ex-student

boat builders and teachers. She was eventually launched on 26th November

2004.

[Photo 12: Launch of Swiftsure II, Southerly Dolling]

We were used by that time to a large gathering of volunteers meeting each

Monday evening to build a boat, so we decided to continue, using the time to

maintain our growing fleet of small wooden boats, and to build the occasional

new one, pausing around 7pm for a good meal and a bit of social interaction.

20

[Photo 13: Dinner at the shed, The Living Boat Trust Inc.]

[Photo 14: dinner outside, LBT]

21

This has now become a vital institution and is supplemented by women’s

rowing groups twice a week, a men’s group who do the serious repair work

and build bespoke boats for members who provide materials and supply

professional tuition where needed.

[photo 15: Men’s group building and restoring, Richard Forster.]

Now the Women on Water, have built their own St Ayles skiff, the first built in

Australia. They named her Imagine, and have entered the inaugural World

championships at Ullapool, Scotland, this coming August.

22

[Photo 16: Building Imagine, Jane Johnson, Women On Water]

Photo 17: Rowing Imagine, Feb 13, 2013, Jane Johnson,WOW]

23

The annual Swiftsure regatta was the initial stimulus for the On The Water

program.

[Photo 18: On the Water Programme, LBT]

It started as a volunteer activity to provide local school students with

experience in basic seamanship and sailing. For one amazing year we got state

funding for it but we always knew that was a one-off grant. Since then we have

resumed the volunteer version and, as we train more of our members as

qualified instructors, we will be able to expand the programme.

[Photo 19: OWP deliberate capsize, LBT.]

24

[Photo 20: Bailing after capsize, LBT]

[Photo 21: Maintenance, LBT]

We got the Raid idea, an expedition of un-powered wooden boats, in the

Viking tradition, dependent entirely on wind and muscle, from the French

Albacore Company, who ran a series of communal open boat voyages in the

1990s in French Polynesia, Portugal, Scotland and Sweden. In 2004 they were

looking for exotic locations beyond Europe for the next one. So the LBT, invited

Charles-Henri Le Moing and his team to come to Tasmania and check out the

D’entrecasteaux Channel. The French were very impressed, and asked the

Tasmanian Government to pay them to stage the event as other countries had

25

done. That didn’t work. So we decided to do it ourselves as a community event

rather than a commercial operation.

[Photo 22: Mickey’s Bay, Bruny Island, Feb 2013, Richard & Jill Edwards]

The other inspiration was Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales of the 14th

century, when a group of pilgrims of all social classes met each spring at the

Tabard Inn in London, to walk from London to Canterbury, entertaining each

other each evening by telling stories.

We wanted to fulfil our constitutional obligation of community development,

by bridging the gap between Aboriginal culture and the colonial mentality of

the British invaders, so we sought permission from the South Eastern

Tasmanian Aboriginal Council to use the title Tawe Nunnugah5 for the first

expedition in 2007.They lent us their flag as well, to fly as our courtesy flag,

5 Tawe= To go; Nunnugah = canoe, in the language of the local Nueone people of the D’Entrecasteaux Channel.

26

[Photo 23 Rowing to Hobart, L. Biggs] not, as some misunderstood, to pose as

Aborigines, but in accordance with international protocol, to fly the flag of the

people who owned the country in 1803, and, in the absence of any treaty to

the contrary, still own it. Evenings are spent exercising not only the elbow, but

our minds as well, fuelled by local entertainments, and literary, philosophical

or historical discussions. The expeditions of 2007, 2009 and 2011 and 2013

that followed have established The Living Boat Trust as a regular contributor to

the cultural life of Tasmania.6

All these exercises, from building large wooden ships and getting crowds of

people to come to boat shows, to building dinghies or teaching kids how to

row; women taking collectively to the water, making people think about

Aboriginal ownership, and the meaning of sustainability, have been part of a

social counter-current that runs against the general run of mainstream

ideology, and they emphasise community building and intergenerational

responsibility rather than individual achievement.

6 For an account of this expedition, see Young, John, “Tawe Nunnugah: a Raid with a Difference”, Classic Boat

No 239, May 2008, pp.42-46.

27

It’s worthwhile to consider why such a romantic movement as community boat

building actually works, and achieves things beyond its immediate purpose.

Probably it’s because of the nature of the task of building a wooden boat, and

the other things that get built when a group of people get together to do it.

For most people, the transition from a stack of timber on the floor to a work of

art with a practical function like a wooden boat is a bit miraculous and hard to

comprehend. But once you start, the process explains itself. Lofting stimulates

the imagination, as the fair curves on the floor describe the shapes that will

give the vessel its aesthetic value and its functionality. Achieving accuracy

builds trust in the person at the other end of the tape, and honesty at your

end. Knowledge grows as the ship does, about the timbers and their uses for

different parts of the structure. And this builds humility, and respect for the

wider community of life that we all belong to.

When Ned Trewartha was asked at the last Wooden Boat Festival, if he had

“personally crafted” the grown Huon Pine breast hook of one of his dinghies,

he famously replied, “No. Nature did that. I just cut it.” As the structure comes

together, with all the parts relying on other members for their ability to play

their own part in the functionality of the boat, like a healthy ecosystem, it

becomes a powerful metaphor for the individual builders as they become part

of something bigger than themselves, while getting to understand the

importance of their individual contribution.

Knowing that if anything is skimped, the boat will leak develops skill and builds

integrity. Setting the standards you need to build a good boat builds leadership

at the start and self-confidence at the end, when finally, the wood swells, and

she takes up successfully. Completing a task of this duration and complexity

builds persistence. It’s an experience that joins people to an expanding circle of

renewed skills and traditions. To say that it builds teamwork is an

understatement. Ultimately it contributes to the health and stamina of

communities.

The scheme for the next step in Franklin’s economically turbulent history is to

build on the achievements of the past, and the example set in the 19th century

of what a small place can achieve on the foundation of its own natural assets.

28

The Franklin Working Waterfront Association was formed last year in response

to the news that Franklin School was likely to be closed, and attracted support

and membership from all of the community associations in Franklin that

already exist, and the Tasmanian Wooden Boat Centre, (the new name for the

Boat School) with the common purpose of gaining public ownership of the old

Franklin Evaporators apple drying factory, to re-cycle it as a multi discipline

shipyard, including essential services such as a sail loft, a bronze foundry, a

rigging shop, a marine engineer, a timber store and marine electrician. This

foundation is intended to become the authentic focus of a tourist destination

including a steam museum, renewable energy workshops and training

facilities, modelled on the most successful overseas examples of this form of

small scale urban renewal; places like Port Townsend, Mystic Seaport, and

Rockport in the United States, and Svendborg, Denmark, Dournanez, France,

and 9 other places, whose economic recovery is well documented.7 We

calculate that 41 new sustainable jobs can be created in two years.

Franklin will provide a restoration site, to start with, for Cartela, Hobart’s

century old wooden steamship, while preparation is made for the construction

of a merchant schooner to carry high quality local produce, and adventure

tourists to metropolitan destinations in Hobart, Melbourne and Sydney. This

will keep local marine trades-people in Franklin, attract more young families,

promote renewable energy, keep the school open and create an authentic port

of refreshment for wooden ships.

7 Gamlin, Andy, Wooden Boat Organisations: Preservation and promotion of Maritime Cultures, Winston

Churchill Memorial Trust 2002/3 www.churchilltrust.com.au. Andy visited and reported on 14 communities in

the USA, France, Scandinavia and the Baltic.

29

[Photo 24: Cartela , Navy 1914-16, Ross James.]

[Photo 25: construction drawing Schooner, Adrian Dean.]

30

Photo 26: Sail Plan, schooner, Adrian Dean.]

One of the main problems is that, though now old skills have been re-learnt,

the other question, do we still have the timber, and will we have it in the

future, still hangs in the balance. We don’t know the answer yet, and the

failure of the Tasmanian Forest Agreement means that fund raising for

anything is going to be difficult. But here’s what we are doing about it.

When Dave Nash arrived in Hobart, on the way to Franklin, one of the first

people he met was Ross James, who had recently been appointed as project

manager of the Cartela Steamship Company. Ross was looking for someone to

work out a plan to restore this famous 100 year old wooden vessel. David

agreed to help him out technically, hoping that the day would come when he

might get paid. As plans for the Franklin Waterfront developed, the advantages

of Franklin as an ideal base for both building a schooner and restoring a

31

steamer, became obvious. David persuaded us that the instant public presence

in Franklin of Cartela will provide immediate support for the development of a

Working Waterfront. The nest of workshops needed for her restoration will

remain when Cartela returns to Hobart, because by then the schooner build

will be well on its way. That will mean that the skilled people who now leave

the Huon Valley and commute to the Mainland regularly to maintain

Australia’s fleet of Tall Ships will be able to attract some of the smaller ships to

come to Franklin, enabling it to build on its history and establish an Australian

equivalent of the overseas success stories.

It’s a situation which doesn’t even require a cricket match to clear the air. So

we held a public meeting about it and agreed to combine authentic restoration

with new construction in the same place.

At one level, things look grim. The sequence of closely repeated economic

crises since the “recession we had to have” in the 1990s may be symptomatic,

like the tremors that precede an earthquake, of a continuing global slide

towards terminal financial disaster. Local setbacks like ongoing floods and bush

fires as climate change becomes more difficult to ignore, make it hard to raise

funds.

But on the other hand economic policy based on hopes of perpetual growth in

a finite planet has led to an increasingly unequal and dangerous world. It’s got

so bad that many people, including more and more economists, are ready to

think outside the box.8 There has never been a stronger need for sustainable

jobs based on local skills and local resources. Fund-raising began, with a

donation of $200 from Women on Water in return for some help in making

oars for Imagine. As a Social Enterprise that re-invests profits in its purpose of

generating sustainable local employment, the Working Waterfront is eligible

for a combination of grants and low interest loans from government and

philanthropic institutions. The first of a chain of applications was made last

month. We’ll also need to do a lot of our own public fundraising.

8 For example, Jackson, Tim, Prosperity Without Growth: Economics for a Finite Planet, Earthscan, London and

Washington, 2009

32

On a national scale, a multiplicity of independently prosperous, diverse

communities each taking advantage of their own assets, adds up to a

prosperous regional Australia. The world we live in now is one in which many

local communities have learnt by long experience that to fight, but not to heed

the wounds, to toil and not to seek for rest, to labour and seek for no reward

as they develop their own authentic sense of place, is a proven path to

sustainable prosperity.

Forty-two years ago, a group of young volunteers took it into their heads to

restore the wreck of James Craig, derelict at Recherche Bay since the beginning

of the Great Depression. She had over 1000 holes in her. One of them was 3

metres wide. They reckoned it would cost $180, 000 to fix her. It took thirty

years to find the place and the people, the materials and the 30 million dollars

of money that it took to enable her to sail again in 2001 as your flagship. We

saw her last month at the Wooden Boat Festival in Hobart, where she is

regularly accepted as an iron sister if not an honorary wooden ship. We are all

inspired by her story. We intend to follow the example of her resurrection and

to discover the power of a local community when it takes control of its own

future.

Related Documents