Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

Hayat Kısa, Sanat UzunBizans’ta Şifa Sanatı

Life Is Short, Art LongThe Art of Healing in Byzantium

Pera Müzesi Yayını / Pera Museum Publication 73

ISBN 978-605-4642-42-7

KATALOG / CATALOGUE

Yayına Hazırlayan / Editor: Brigitte Pitarakis

Koordinatör / Coordinator: Zeynep Ögel

Türkçe Redaksiyon / Turkish copyediting: Gülru Tanman, Buket Kitapçı Bayrı, Begüm Akkoyunlu Ersöz, Tania Bahar, Ulya Soley

İngilizce Redaksiyon / English Copyediting: Robin O. Surratt

Çeviri / Translation: Ayşe Düzkan, Melis Şeyhun Çalışlar, Orçun Türkay, g yayın grubu, Charles Dibble, Valerie Nunn

Grafik Tasarım / Graphic DesignTimuçin Unan + Crew

Renk Ayrımı ve Baskı / Color Separation and PrintingA4 Ofset Matbaacılık San. ve Tic. Ltd. Şti. Oto Sanayi Sitesi, Yeşilce Mah., Donanma Sok. No:16Kağıthane, İstanbul Sertifika No: / Certificate No: 12168

SERGİ / EXHIBITION

Küratör / CuratorBrigitte Pitarakis

Proje Ekibi / Project TeamTania BaharGülru TanmanBegüm Akkoyunlu ErsözUlya Soley

Koordinatörler / CoordinatorsZeynep Ögel

Sergi Tasarımı / Exhibition DesignPATTU, Işıl Ünal, Cem Kozar

Katkılarıyla / By contribution:

İşbirliğiyle / In collaboration with:

KATALOG YAZARLARI / CATALOGUE CONTRIBUTORS

AD Asuman Denker, İstanbul Arkeoloji Müzeleri Istanbul Archaeological Museums

ADr Anastasia Drandaki, Benaki Müzesi Benaki Museum

AS Angeliki Strati, Bizans Müzesi Byzantine Museum

BP Brigitte Pitarakis, CNRS, Paris (Orient et Méditerranée, UMR 8167)

BT Bekir Tuluk, İstanbul Arkeoloji Müzeleri Istanbul Archaeological Museums

CF Christian Förstel, Bibliothèque nationale de France

CGH Charles G. Häberl, Rutgers University, School of Arts and Sciences

FD Feza Demirkök, İstanbul Arkeoloji Müzeleri Istanbul Archaeological Museums

GBÇ Gülbahar Baran Çelik, İstanbul Arkeoloji Müzeleri Istanbul Archaeological Museums

GK Gülcan Kongaz, İstanbul Arkeoloji Müzeleri Istanbul Archaeological Museums

GY Gülcay Yağcı, İstanbul Arkeoloji Müzeleri Istanbul Archaeological Museums

IB Ioanna Bitha, Atina Akademisi Academy of Athens

MK Mine Kiraz, İstanbul Arkeoloji Müzeleri Istanbul Archaeological Museums

MV Mara Verykokou, Benaki Müzesi Benaki Museum

NHE Nihal Hanım Erhan, İstanbul Arkeoloji Müzeleri Istanbul Archaeological Museums

PBV Petros Bouras-Vallianatos, King’s College London, Centre for Hellenic Studies

RB Rosanna Ballian, Benaki Müzesi Benaki Museum

SE Stephanos Efthymiadis, Open University of Cyprus

SH Stephen Harris, Oxford University Herbaria

ŞK Şehrazat Karagöz, İstanbul Arkeoloji Müzeleri Istanbul Archaeological Museums

Bu katalog, 10 Şubat – 26 Nisan 2015 tarihleri arasında Suna ve İnan Kıraç Vakfı Pera Müzesi’nde

açılan “Hayat Kısa, Sanat Uzun: Bizans’ta Şifa Sanatı” sergisi için hazırlanmıştır.

This catalogue has been prepared for the exhibition “Life Is Short, Art Long: The Art of Healing

in Byzantium”, opening between 10 February – 26 April 2015 at the Suna and İnan Kıraç

Foundation, Pera Museum.

Robert G. Ousterhout

Konstantinopolis’te Su ve Şifa

Mimari Kalıntıları Okumak

Water and Healing in Constantinople

Reading the Architectural Remains

65

Hem tıbbi hem de mucizevi şifa bulma süreçleri Bizans Konstan-

tinopolisi’nde farklı mimari mekânlarda gerçekleşirdi. Bazı şifa

mekânları çok iyi planlanmış, bazıları doğaçlama ortaya çıkmış, bazı-

ları ise beklenmedik yerlerdi. Arkeolojik buluntular sınırlı olmasına

rağmen suyla bağlantılı şifa mekânlarını araştırmak hâlâ mümkündür.

Metinlerde birçok şifa mekânı anlatılsa da, fiziksel izler nadiren gü-

nümüze ulaşmıştır. Birkaç ayazmayla (kutsal pınarlar) ilgili arkeolo-

jik buluntular olmakla birlikte Bizans hastanelerinden günümüze ne-

redeyse hiçbir şey kalmamıştır ve iki mekân için kurumsallaşmış bir

mimari tipolojinin olup olmadığı muğlaktır.

Örneğin Aziz Artemios’un yedinci yüzyıla ait mucize anlatıları, teda-

vilerin inkubasyon aracılığıyla yapıldığını ve ihtiyaç sahiplerinin Aziz

Ioannes’e ithaf edilmiş mütevazı bir bazilika kilisede uyuduğunu belir-

terek şifa mekânıyla ilgili çok önemli bilgiler verir. Azizin rölikleri kut-

sal mekânın altındaki bir mahzende (krypta) bulunuyordu.1 Artemios

erkek üreme organlarındaki hastalıklarda uzmanlaşmıştı ve kayda ge-

çen tedaviler genellikle pis, kokulu ve acılıydı. Modern hassasiyetleri-

mizle, korkutucu fiziksel görünümü, gürültüsü ve kokusu ile bir ibadet

mekânında açıkta yatan hastaları hayal etmek güçtür ama bunun Bi-

zans sosyal hayatında kabul edilebilir olduğu görünüyor.

Mucizeler serisindeki (miracula) anlatımlara göre Aziz Ioannes’in kili-

sesi oldukça standart bir bazilika olarak canlandırılabilir. Bu anlatılar-

da birçok mimari unsurdan bahsedilir: avlu (atrium) ve narteks, her

iki yanı galerili birer yan nefle kuşatılmış nef, nefte bir vaiz kürsüsü

(ambon), nefi kutsal mekândan (bema) ayıran templon’da bir altar ve

synthronon (yarım daire şeklinde bank) yer almaktaydı. Bemanın so-

lunda skeuophylakion ve sağında, kadın hastaların iyileştirilmesinde za-

man zaman Artemios’a yardımcı olan Azize Febronia’nın şapeli var-

dı. Kilisenin dışında bir vaftizhane, bir kuyu, bir yemekhane, bir tuva-

let ve büyük ihtimalle bir hastane (ksenon) mevcuttu, ancak hastane-

nin varlığı şüphelidir.

Olağandışı olan, merdivenlerle ulaşılabilen ve araştırmacıların en baş-

tan itibaren azizin mezarı (martyrion) olarak tasarlandığını düşündü-

ğü bir mahzenin (krypta) varlığıdır. Ancak adını oraya ulaşmak için

1 C. Mango, “On the History of the Templon and the Martyrion of St. Artemios at

Constantinople,” Zograf 10 (1979): 40–43; V. S. Crisafulli ve J. W. Nesbitt, The

Miracles of St. Artemios: A Collection of Miracle Stories by an Anonymous Author of

Seventh-Century Byzantium (Leiden, 1997), özellikle 9–19.

The process of healing, both medical and miraculous, occurred in a va-

riety of architectural spaces in Byzantine Constantinople. Some efforts

were well planned, some ad hoc, some improbable. Despite the limited

archaeological remains, it is still possible to examine the settings for heal-

ing in relation to water. While many sites for healing are described in texts,

only rarely have physical traces survived. Whereas there is archaeological

evidence of a few hagiasmata (holy springs), there is almost nothing re-

maining of Byzantine hospitals, and it is unclear if there was an established

architectural typology for either.

The seventh-century accounts of the miracles of St. Artemios, for exam-

ple, provide a fascinating look at a site where cures were effected by in-

cubation, whereby those in need slept within a modest basilican church

dedicated to St. John. The saint’s relics were housed in a crypt beneath the

sanctuary.1 Artemios specialized in diseases of the male genitalia, and the

cures recorded were often messy, smelly, and painful. With our modern

sensibilities, it is difficult to imagine the alarming physical presence, the

noise, and the odor of the diseased camped out in a place of worship, yet

this seems to have been acceptable in the Byzantine milieu.

Based on descriptions, St. John’s may be reconstructed as a rather standard

basilica, as the miracula mention many of its components: the atrium and

narthex, a nave flanked by side aisles with a gallery; an ambo in the nave;

and a templon dividing the nave from the bema, in which stood an altar

and a synthronon. To the left of the bema was the skeuophylakion, and to

its right was the chapel of St. Febronia, who occasionally assisted Artemios

with female patients. Outside the church were a baptistery, a well, a refec-

tory, a latrine, and possibly a xenon (hospital), although the existence of

the last has been questioned.

What is unusual is the presence of a crypt, accessible by stairs, which schol-

ars believe was destined from the start to be the martyrion of the saint.

The location of the church, however—on the hill of Oxeia, whose name

derives from the steepness of its slope—suggests that the crypt may have

been developed from the substructures necessary to level the site. In either

case, pilgrims frequented the crypt. The popularity of the site seems to

have resulted in the accommodation for incubation, so that those waiting

1 C. Mango, “On the History of the Templon and the Martyrion of St. Artemios at

Constantinople,” Zograf 10 (1979): 40–43; V. S. Crisafulli and J. W. Nesbitt, The

Miracles of St. Artemios: A Collection of Miracle Stories by an Anonymous Author of

Seventh-Century Byzantium (Leiden, 1997), esp. 9–19.

66

çıkılması gereken yokuşun dikliğinden almış Okseia tepesindeki bu ki-

lisede bulunan krypta, yapıyı düz bir zemine oturtmak için inşa edilen

altyapılar sonucu ortaya çıkmış olabilir. Durum ne olursa olsun, hacı-

lar kryptanın kapısını aşındırırdı. Mekânın popülerliği inkubasyon için

kullanılmasına neden olmuş ve şifa bekleyenler kilisenin içinde konak-

lamaya başlamıştı. O yüzden yan kanatlar geceleri üstlerine kilit vuru-

lan hastalardan, kankelloi (bir tür parmaklık) ile ayrılmıştı. Büyük bir

ihtimalle bu geçici çözüm, mucizevi şifalar gerçekleşmeye başlayınca ki-

lisenin iç mekânında yapılan bir tadilattır.

Birçok şifalı tedavi, azizlerin röliklerinden ziyade ayazmalarla bağlan-

tılıydı. Örneğin Blakhernai Kilisesi külliyesi mucizevi iyileşmelerin gö-

cures could camp inside the church. The aisles were thus fenced off with

kankelloi (grills of some sort), with the infirm locked in at night. This prob-

ably represents an ad hoc solution, a modification to the church interior

once the miraculous cures began to occur.

Many cures involved holy springs rather than the relics of saints. The

Blachernai Church complex, for example, seems to have been founded

next to a holy spring at which miraculous cures were noted. Originally

located outside the land walls immediately to the north of the city, the

area was enclosed by an extension of the city’s fortifications in the twelfth

century. The great basilica at the site is often attributed to the empress

Pulcheria, although it is more likely the product of the emperor Justin in

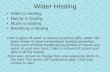

Şek. 1 Plan, altıgen bina,

Mangana civarı, 1934

(R. Demangel ve E. Mamboury,

Le quartier des Manganes

et la première région de

Constantinople [Paris, 1942],

lev. XII).

Fig. 1 Plan, hexagonal building,

Mangana area, 1934

(from R. Demangel and

E. Mamboury, Le quartier des

Manganes et la première région

de Constantinople [Paris, 1942],

pl. XII).

67

the early sixth century.2 Leon I had constructed the octagonal chapel of

the Hagia Soros several decades earlier to house the robe of the Virgin,

which had been brought from Palestine to Constantinople in 473. He

may also have been responsible for the construction of the famed hagi-

asma known as the Hagion Louma (or Lousma). Basil II restored it in

the early eleventh century.3

The Hagion Louma was domed and connected to the Soros chapel. Both

were situated to the south of the basilica. The louma (bath) included an

apodyton (dressing room); a kolymbos (described as “the inner tholos,” which

contained the basin of water); and a chapel of St. Photeinos. The walls of

the kolymbos were decorated with icons, with an image of the Theotokos

in a niche on the east side, as well as a marble image of the Theotokos with

pierced hands, from which water flowed.4

Although the descriptions remain rather vague, the components at the Blach-

ernai hagiasma—a centrally planned, domed room supplied with water,

2 C. Mango, “The Origins of the Blachernae Shrine at Constantinople,” Acta XIII

Congressus Internationalis Archaeologiae Christianae: Radovi XIII—Medunarodnog

Kongresa za Starokrscansku Arheologiju, Split-Porec 25.9–1.10.1994 (Split, 1998), 61–76.

3 R. Janin, La géographie ecclésiastique de l’empire byzantin, vol. 3, pt. 1 Les églises et les

monastères (Paris, 1969), 161–71.

4 Moutafov Emmanuel, “Blachernai, Basilica of the Virgin Mary,”

Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World, vol. 3, Constantinople, http://kassini.fhw.gr/

constantinople/forms/fmain.aspx; Constantine Porphyrogennetos, The Book of

Ceremonies, Byzantina Australiensis 18, trans. A. Moffatt and M. Tall, with the

Greek edition of the Corpus scriptorum historiae byzantinae (Bonn, 1829), 2 vols.

(Canberra, 2012), 2:R551–56: “What is necessary to observe when the rulers go away

to bathe at Blachernai.”

rüldüğü bir ayazmanın yanında kurulmuş olsa gerek. Başta şehrin he-

men kuzeyindeki surların dışına yerleşmiş olan alanın çevresi on ikin-

ci yüzyılda kent surlarının bir uzantısıyla kapatıldı. Külliyenin içinde-

ki büyük bazilika İmparatoriçe Pulcheria’ya atfedilse de altıncı yüzyı-

lın başında İmparator Ioustinos tarafından yaptırılmış olması daha

olasıdır.2 I. Leon bundan yirmi otuz yıl önce, Meryem Ana’nın 473’te

Filistin’den Konstantinopolis’e getirilen elbisesini barındırmak üze-

re sekizgen Hagia Soros şapelini inşa ettirmişti. Aynı zamanda Hagion

Louma (ya da Lousma) olarak bilinen ünlü ayazmanın inşa edilmesin-

den de onun sorumlu olması mümkündür. II. Basileios bu ayazmayı on

birinci yüzyılın başında restore ettirmiştir.3

Hagion Louma kubbeliydi ve Soros şapeline bağlıydı. İkisi de bazilika-

nın güneyinde konumlanmıştı. Louma’da (ritüel hamamı), bir apody-

ton (giyinme odası), bir kolymbos (havuzun bulunduğu “iç tholos” ola-

rak tarif edilen) ve Aziz Photeinos’a adanmış bir şapel bulunurdu.

Kolymbos’un duvarları ikonalarla bezeliydi; Meryem Ana’nın (Theoto-

kos) doğu tarafta bir nişte bulunan bir tasvirinin yanı sıra, mermer ka-

bartma bir başka tasviri daha vardı, ellerinden su akardı.4

Tariflerin biraz muğlak olmasına rağmen, Blakhernai ayazmasında-

ki unsurlar—suyun bulunduğu, merkezi olarak planlanmış kubbeli bir

oda ve yanlarda daha küçük tali alanlar—bir özel hamamda veya belki

bir vaftizhanede bulunabilecek özelliklere benzer. Nitekim Hagion Lo-

uma iki işlevi birden görmüştü çünkü imparator burada iki kere banyo

yapardı; ilkinde bedenini temizlemek için ve ardından ayin gereği üç

kez burada suya batırılırdı.5

Dahası, metinlerde anılan görevliler şüphe uyandırır bir biçimde, bal-

nearites (banyo yaptıranlar), sabuncular ve yağcılar da dâhil olmak üze-

re, hamam görevlilerine benzer. Metinler ve kazılardan öğrendiklerimi-

ze göre birçok ayazmadan farklı olarak Hagion Louma, zeminin üzerin-

de ve kiliseyle aynı seviyededir.

2 C. Mango, “The Origins of the Blachernae Shrine at Constantinople,” Acta XIII

Congressus Internationalis Archaeologiae Christianae: Radovi XIII—Medunarodnog

Kongresa za Starokrscansku Arheologiju, Split-Porec 25.9–1.10.1994 (Split, 1998),

61–76.

3 R. Janin, La géographie ecclésiastique de l’empire byzantin, c. 3, böl. 1 Les églises et les

monastères (Paris, 1969), 161–71.

4 Moutafov Emmanuel, “Blachernai, Basilica of the Virgin Mary,”

Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World, c. 3, Constantinople, http://kassini.fhw.gr/

constantinople/forms/fmain.aspx; Constantine Porphyrogennetos, The Book of

Ceremonies, Byzantina Australiensis 18, çev. A. Moffatt ve M. Tall, Corpus scriptorum

historiae byzantinae’nin Yunanca baskısıyla birlikte (Bonn, 1829), 2 cilt (Canberra,

2012), 2:R551–56: “Hükümdarlar Blakhernai’de yıkanmaya gittiğinde gözetilmesi

gerekenler.”

5 A.-M. Talbot, “Holy Springs and Pools in Byzantine Constantinople,” Istanbul and

Water, Ancient Near Eastern Studies Supplement 47, ed. Paul Magdalino ve Nina

Ergin (Leuven, 2014), 157–70, özellikle 159.

Şek. 2 Amiral Tadfil Sokak’taki ayazmada bulunan, on ikinci yüzyıla ait Meryem Ana

freski, İstanbul (fotoğraf: Robert Ousterhout).

Fig. 2 Twelfth-century wall painting of the Theotokos at the hagiasma on Amiral

Tadfil Street, Istanbul (photo: Robert Ousterhout).

68

flanked by smaller subsidiary spaces—sound similar to the features one might

find in a private bathing establishment or perhaps a baptistery. Indeed, the

Hagion Louma functioned similarly to both, for the emperor bathed twice—

first to cleanse his body, and afterward he was ritually immersed three times.5

Moreover, the attendants mentioned in texts sound suspiciously like those of

a bath, including balnearites (bathers), soap bearers, and oil bearers. Notably,

unlike many hagiasmata known from texts or excavated remains, the Hagion

Louma lay above ground, on the same level as the church.

Nothing survives of the Blachernai complex. Today there is a nondescript

modern chapel above the spring. Nevertheless, the archaeological remains

discovered at a different location almost a century ago may help to visualize

it (Fig. 1).6 A building complex lying in the Mangana area due east of Hagia

Sophia was excavated by the French in 1923 and reexamined in 1933. The

main building was a hexaconch, preceded by a sigma (C-shaped) portico,

paved in marble, with an ancient well near its center. Enveloped by monu-

mental apses, the hexaconch was probably originally vaulted, with a dome

slightly less than thirteen meters in diameter. Doors within the niches

connected to small circular and hexagonal chambers. While early scholars

attempted to compare the features of the hexaconch with bathing estab-

lishments, many of these features—the hexagonal hall, the open plan, the

intricate geometry—compare favorably with the palace of Antiochos by

the Hippodrome, built in the early fifth century, which was subsequently

converted into the Church of St. Euphemia.7 On the basis of this compari-

son, it has been suggested, probably correctly, that this was originally a secu-

lar residence of the fifth century.8

At the center of the hexagon, however, the excavators found an enormous

font of Prokonessian marble, dodecagonal on the exterior, measuring five

and a half meters across. Inside were six stepped lobes, with entrances into

the basin awkwardly cut on the axes, suggesting its probable reuse in this lo-

cation. The basin was apparently covered by a ciborium raised above twelve

octagonal colonnettes, whose settings were visible on the upper surface of

the marble. The excavators discovered that the marble font had been laid

over a smaller (and older) octagonal basin of brick. Water conduits were

found in the conches. Among the small finds was a lead seal tentatively iden-

tified as belonging to a certain Theophanes, chartoularios of the Hodegon,

and a small bronze cross representing the Virgin of the Hodegetria type.

5 A.-M. Talbot, “Holy Springs and Pools in Byzantine Constantinople,” Istanbul and

Water, Ancient Near Eastern Studies Supplement 47, ed. P. Magdalino and N. Ergin

(Leuven, 2014), 157–70, esp. 159.

6 R. Demangel and E. Mamboury, Le quartier des Manganes et la première région de

Constantinople (Paris, 1942), 88–111 and pl. XII.

7 R. Naumann and H. Belting, Die Euphemia-Kirche am Hippodrom in Istanbul und ihre

Fresken, Istanbuler Forschungen 25 (Berlin, 1966).

8 S. Ćurčić, Architecture in the Balkans from Diocletian to Süleyman the Magnificent

(New Haven, 2010), 89.

Blakhernai külliyesinden günümüze hiçbir şey kalmadı. Bugün pına-

rın üzerinde sınıflandırması zor, modern bir şapel vardır. Yine de, nere-

deyse bir yüzyıl önce farklı bir yerde keşfedilen arkeolojik kalıntılar onu

gözümüzde canlandırmamıza yardımcı olabilir (Şek. 1).6 Ayasofya’nın

doğusuna düşen Mangana civarındaki bir bina kompleksi 1923’te Fran-

sızlar tarafından kazılmış ve 1933’te yeniden incelenmiştir. Ana bina,

ortasında eski bir kuyunun bulunduğu, mermerle kaplı sigma (C) bi-

çiminde portikolu bir girişi olan bir heksakonkhos’tur. Heybetli yarım

kubbeli nişlerin sarmaladığı heksakonkhos büyük bir ihtimalle, başlan-

gıçta on üç metreye yakın çapı bulunan bir kubbeye sahipti. Nişlerde-

ki kapılar küçük dairesel ve altıgen odalara açılıyordu. İlk araştırmacılar

bu heksakonkhos’un özelliklerini hamam tesisleriyle kıyaslamaya çalış-

mıştı, ancak bu özelliklerin çoğu—altıgen salon, açık plan, çetrefil ge-

ometri—beşinci yüzyılın başında inşa edilen ve daha sonra Azize Eup-

hemia Kilisesi’ne7 dönüştürülen, Hippodrom’un yanındaki Antiokhos

sarayıyla daha fazla benzerlik taşıyordu. Bu kıyaslamaya dayanılarak ve

büyük ihtimalle haklı olarak buranın beşinci yüzyılda seküler bir konut

olduğu ileri sürüldü.8

Ancak kazıyı yürütenler altıgenin ortasında, Prokonessos mermerin-

den yapılmış, dışı onikigen olan ve boyu beş buçuk metreyi bulan mu-

azzam bir vaftiz teknesi buldular. İçinde, tekneye açılan girişleri tuhaf

biçimde eksenlerinden kesilmiş, basamaklı yarım daire biçiminde altı

girinti bulunması, büyük ihtimalle, bu öğenin farklı bir amaçla burada

yeniden kullanılmış olduğuna işaret eder. Görünüşe bakılırsa, teknenin

üstü, yuvaları mermerin üst yüzeyinden seçilebilen on iki sekizgen sü-

tunçenin üzerinde yükselen bir kiborion’la örtülmüştü. Kazıyı yapan-

lar, mermer teknenin daha küçük (ve daha eski) sekizgen bir tuğladan

teknenin üzerini kapladığını keşfetti. Su kanalları nişlerde bulunuyor-

du. Küçük buluntular arasında, Hodegon’un khartoularios’u olan The-

ophanes adlı birine ait kurşun bir mühür ve Hodegetria tipinde Mer-

yem Ana tasvirli küçük bir bronz haç vardır.

Bu yapı, bir zamanlar Hodegon Manastırı’na ait olabilir mi? Blakher-

nai gibi, Hodegon’daki mucizevi su kaynağının adının da Hagion Lou-

ma olması dikkate değer. Araştırmacılar Mangana heksakonkhosu’nun

kimliği konusunda hâlâ karar vermiş değiller ancak topografik göster-

geler manastırın bu alanda bir yerde—yani Ayasofya’nın doğusunda,

Büyük Saray’ın ve denizin yakınında—bulunduğuna işaret eder.9 Ama

6 R. Demangel ve E. Mamboury, Le quartier des Manganes et la première région de

Constantinople (Paris, 1942), 88–111 ve lev. XII.

7 R. Naumann ve H. Belting, Die Euphemia-Kirche am Hippodrom in Istanbul und ihre

Fresken, Istanbuler Forschungen 25 (Berlin, 1966).

8 S. Ćurčić, Architecture in the Balkans from Diocletian to Süleyman the Magnificent

(New Haven, 2010), 89.

9 Janin, Églises et les monastères, 206–207.

69

Could this have been part of the Hodegon Monastery? Notably, like the

Blachernai, the miraculous source at the Hodegon is also called the Hagion

Louma. Although scholars remain divided on the identification of the

Mangana hexaconch, the topographical indicators point to the monastery

being somewhere in this area—that is, east of Hagia Sophia, near the Great

Palace, and the sea.9 But the monastery only appears in the sources after

the ninth century, considerably later than the excavated foundations. One

of the earliest references, the ninth-century Patria, notes that a chapel pre-

ceded the founding of the monastery, where many blind people were cured

and miracles occurred.10 In the late twelfth century, it is referred to as a

thermokentrion (warming room), like that of a bath, which might be appro-

priate for the centrally planned room. A fourteenth-century text, however,

relates, “There is here a spring gushing forth purest water which up to this

day is in the crypt of this all-holy and divine church.”11 Kataphyge, the term

9 Janin, Églises et les monastères, 206–207.

10 Accounts of Medieval Constantinople: The Patria, Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library

24 (Cambridge Massachusetts, London, 2013), 150 (Greek text), 151 (English

translation).

11 Talbot, “Holy Springs,” 158, 163. Regarding kataphyge as refuge, Theodore

Metochites refers to the Theotokos and the Chora Monastery as his kataphyge. See

R. Ousterhout, “The Virgin of the Chora: An Image and Its Contexts,” in The Sacred

Image East and West, ed. R. Ousterhout and L. Brubaker (Urbana, 1995), 91–108,

esp. 96.

manastır sadece kazıda bulunan temellerden epey sonraya ait, doku-

zuncu yüzyıldan sonraki kaynaklarda görünür. En eski referanslardan

biri olan dokuzuncu yüzyılda yazılmış Patria’da manastırın kurulma-

sından önce birçok kör insanın iyileştiği ve mucizelerin gerçekleştiği bir

şapelden söz edilir.10 On ikinci yüzyılın sonunda, buradan, hamamlar-

da bulunanlar gibi bir thermokentrion (ısınma odası) olarak söz edil-

mektedir ki bu, merkezi olarak planlanmış oda için uygun olabilir. Öte

yandan, on dördüncü yüzyıla ait bir metin şöyle der, “Burada, bugü-

ne kadar, kutsal ve ilahi kilisenin kryptasında bulunan ve en saf suyun

taşarak aktığı bir pınar vardır.”11 Kryptanın karşılığı olan (ve metafo-

rik olarak sığınak anlamında da kullanılan) kataphyge, Silivrikapı Balık-

lı Ayazması’ndaki (Zoodokhos Pege) yeraltı pınarını tanımlamak için

kullanılan terimin aynısıydı. Benzer şekilde, Mangana’da kazı yapanlar

heksakonkhos’un bulunduğu tepenin aşağısındaki küçük bir odanın

10 Accounts of Medieval Constantinople: The Patria, Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library

24 (Cambridge Massachusetts, Londra, 2013), 150 (Yunanca metin), 151 (İngilizce

çeviri).

11 Talbot, “Holy Springs,” 158, 163. Kataphyge’nin sığınak anlamında kullanımı

bağlamında, Theodoros Metokhites, Theotokos ve Kariye Manastırı’ndan kendi

sığınağı olarak bahseder. Bkz. R. Ousterhout, “The Virgin of the Chora: An Image

and Its Contexts,” The Sacred Image East and West, ed. R. Ousterhout ve L. Brubaker

(Urbana, 1995), 91–108, özellikle 96.

Şek. 3 İncili Köşk’ün bulunduğu alanda

Philanthropos ayazmasının yerini gösteren

plan, 1934 (Demangel ve Mamboury,

Le quartier des Manganes, lev. X).

Fig. 3 Plan showing location of the

Philanthropos hagiasma in the area of the

Incili Kosk, 1934 (from Demangel and

Mamboury, Le quartier des Manganes, pl. X).

70

for crypt (and used metaphorically to mean refuge), is the same as is used

to describe the subterranean spring at the Zoodochos Pege. Accordingly,

the excavators of the Mangana suggested that a small chamber down the

hill from the hexaconch was the actual hagiasma and called the hexaconch

a baptistery.12 The identification remains contested.

Although there is no record of the Hodegon Monastery before the pe-

riod of iconoclasm, Nikephoros Kallistos Xanthopoulos attributed the

founding of the sanctuary to Pulcheria, along with the Blachernai and the

Chalkoprateia.13 It was founded allegedly to house the famed icon of the

Theotokos painted by St. Luke. Like the Blachernai, the Hodegon housed

an icon that figured prominently in the ceremonial life of the Byzantine

city. The same information appears in the account of the sixth-century his-

torian Theodore Anagnostes, although this may be a later interpolation.

The Patria assigns the foundation to Michael III.14 Perhaps as occurred at

12 See Demangel and Mamboury, Quartier des Manganes, pl. 1.

13 B. Pentcheva, Icons of Power: The Mother of God in Byzantium (University Park,

Pennsylvania, 2006), 117–22.

14 Patria, 150 (Greek text), 151 (English translation).

gerçek ayazma olduğunu ileri sürdüler ve heksakonkhos’u bir vaftizha-

ne olarak tanımladılar.12 Bu tespit hâlâ tartışmaya açıktır.

İkonakırıcılık döneminden önce Hodegon Manastırı ile ilgili herhan-

gi bir kayıt olmamasına rağmen Nikephoros Kallistos Ksanthopoulos,

Blakhernai ve Khalkoprateia ile birlikte bu kutsal mekânın kuruluşunu

Pulcheria’ya atfeder.13 Burası, Meryem Ana’nın Aziz Loukas tarafından

yapılmış ünlü ikonasını koymak için inşa edilmiş bir evdi sözde. Hode-

gon da, Blakhernai gibi, Bizans şehrinin törensel hayatında önemli rol

oynayan bir ikonayı barındırmaktaydı. Aynı bilgi altıncı yüzyılda yaşa-

mış olan tarihçi Theodoros Anagnostes’in anlatımlarında da görülür,

ancak bu bilgi daha sonra eklenmiş olabilir. Patria buranın kuruluşu-

nu III. Mikhael’e atfeder.14 Belki de Antiokhos sarayında olduğu gibi

geç antik dönemden kalma seküler bir yapı sonradan dini amaçlı bir

kullanım için, bu vakada bir vaftiz kurnası eklenerek dönüştürülmüş-

12 Bkz. Demangel ve Mamboury, Quartier des Manganes, lev. 1.

13 B. Pentcheva, Icons of Power: The Mother of God in Byzantium (University Park,

Pennsylvania, 2006), 117–22.

14 Patria, 150 (Yunanca metin), 151 (İngilizce çeviri).

Şek. 4 Philanthropos ayazmasının planı,

1923 (Demangel ve Mamboury,

Le quartier des Manganes, şek. 70).

Fig. 4 Plan of the Philanthropos

hagiasma, 1923 (from Demangel and

Mamboury, Le quartier des Manganes,

fig. 70).

71

the palace of Antiochos, a secular property from the late antique period

was subsequently converted to religious use, in this instance with the inser-

tion of a font. Whatever its identity, the Mangana hexaconch presents a

good impression of an early Byzantine hagiasma, contemporaneous with

the structures at the Blachernai.

An unidentified hagiasma of a different character was excavated during

1997–98 by the Istanbul Archaeological Museums on Amiral Tadfil Street

in Sultanahmet. The site has two contiguous levels. The upper dates from

the fifth century, with a partially preserved floor mosaic, the basis for dat-

ing the level. The area seems to have been subjected to a major building

campaign in the eleventh or twelfth century, with massive foundations that

extend to a much deeper level, executed in the recessed brick technique.

The foundations extend over a great area and are now incorporated into

the substructures of several new shops and hotels. Close to four meters

below and immediately to the north of the floor mosaics lies a hagiasma

built into a niche in the foundations (Fig. 2). Less than a meter wide and

deep and covered by a small barrel vault, the pool of water is fronted by an

unadorned marble slab. The lunette above the pool is decorated with an

image of an orans Theotokos with the Christ child before her, executed in

painted plaster. An illegible inscription surrounds the image.

The image suggests the hagiasma was dedicated to the Theotokos, al-

though the iconography does not indicate anything more specific about its

dedication. The excavator suggested that the foundations were either those

of Basil’s Nea Church or of the Hodegon Monastery, although neither

seems likely: the site lies too far south to be the Hodegon, and the masonry

dates too late to be the Nea Church. Similarly, a reading of the iconography

as the Zoodochos Pege is unlikely, as this image predates the development

of the latter.15 Whatever its identity, the hagiasma is clearly an insertion into

the substructures of a building at an upper level, now lost. It was neither

planned in advance nor lavishly appointed.

The hagiasma of the Savior Philanthropos was built into the ramparts of the

sea wall, over which the İncili Köşk was constructed in the sixteenth century

(Fig. 3). Orthodox Christians continued to visit the spring into the nine-

teenth century, even though it lay on the grounds of the Topkapı Palace.16

The site’s identification is based on the continuity of the hagiasma through

the Ottoman period. It may date to the early twelfth century, when the

monastery was constructed under Alexios Komnenos, but it was frequented

15 F. Düzguner, “Anaplous ve Prookthoi’de Yeni Buluntular,” in Istanbul, ed. N. Basgelen

and B. Johnson (Istanbul, 2002), 32–50, suggests either the Nea Church or the

Hodegon or both as identification; F. Tülek, “A Fifth Century Floor Mosaic and

a Mural of Virgin of Pege in Constantinople,” Cahiers archéologiques 52 (2008),

23–30, dates the painting to the mid-eleventh or twelfth century and attributes the

iconography as that of the Zoodochos Pege.

16 Demangel and Mamboury, Quartier des Manganes, 49–68 and pl. 10.

tü. Kimliği ne olursa olsun Mangana heksakonkhosu, Blakhernai yapı-

larının çağdaşı olarak, erken dönem Bizans ayazması hakkında iyi bir fi-

kir verir.

Farklı yapıda, henüz tanımlanamamış bir ayazma, 1997–98 yılların-

da İstanbul Arkeoloji Müzeleri tarafından Sultanahmet’te Amiral Tad-

fil Sokağı’nda yapılan kazıda bulundu. Sit alanında ardışık iki tabaka

bulunmaktaydı. Kısmen korunmuş olan zemin mozaiği ile tarihi be-

lirlenen üst tabaka beşinci yüzyıla aittir. Gizli tuğla tekniğiyle yapıl-

mış, daha derin bir seviyeye inen muazzam temeller, bölgenin on birin-

ci ve on ikinci yüzyıllarda büyük bir yapılaşma furyasına maruz kaldı-

ğına işaret eder. Çok geniş bir alana yayılan temeller, mevcut bazı yeni

dükkân ve otellerin altyapılarına dâhil olmuştur. Neredeyse dört met-

re aşağıda ve zemin mozaiklerinin hemen kuzeyinde, temellerdeki bir

nişe inşa edilmiş bir ayazma vardır (Şek. 2). Bir metreden az genişliği

ve derinliği olan bu ayazma küçük bir beşik tonozla örtülmüştür, havu-

zun önünde bezemesiz mermer bir levha bulunur. Havuzun üzerindeki

Şek. 5 Meryem Ana’nın Mangana kazılarında bulunan mermer ikonası, günümüzde

İstanbul Arkeoloji Müzeleri’nde.

Fig. 5 Marble icon of the Theotokos found in the Mangana excavations, now in the

Istanbul Archaeological Museums.

72

by pilgrims in the late Byzantine period. The church, situated above and to

the north, was also noted for a miraculous appearance of Christ and for the

body of St. Aberkios. Set in a passageway within the Byzantine substructures

behind the kiosk, at the junction of two towers, is a deep niche with a cor-

belled brick arch. These may be the last remaining vestiges of the hagiasma

chapel. The water was apparently accessible from both inside and outside

the sea wall. Beneath the supports of the kiosk, stairs led down to a rectan-

gular basin, where the water collected, and which apparently overflowed,

thereby extending its curative powers to the sand along the beach (Fig. 4).

The area outside the sea wall was visited for its healing power in the four-

teenth and fifteenth centuries. The site is regularly mentioned in the itin-

eraries of Russian pilgrims. Zosima reports, “There is holy water below the

church, and innumerable sick and lepers receive healing by burying their

feet in the sand.” The Russian Anonymous also recounts similar activities,

of invalids burying their ailing legs in the sand along the sea near the holy

water, and “they become healthy when the worms run out of the legs and

out of the whole body.”17

Just north of this area, the excavators found the broken fragments of

a marble relief icon of the Theotokos abandoned in a cistern. Of fine

workmanship, the Theotokos is depicted standing on a pedestal, with

her arms raised orans (Fig. 5). The one surviving (right) hand is pierced,

corresponding to descriptions of the Blachernai image noted above,

17 G. Majeska, Russian Travelers to Constantinople in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Centuries, Dumbarton Oaks Studies 19 (Washington, D.C., 1984), 371–74.

kemer aynası, Meryem Ana’yı önünde çocuk İsa ile dua ederken göste-

ren ve boyalı alçıyla yapılmış bir tasvirle süslenmiştir. Tasvirin çevresin-

de okunamayan bir yazıt bulunur.

Bu tasvir ayazmanın Meryem Ana’ya adandığını düşündürse de, iko-

nografi bu ithafa dair daha belirleyici bir bilgi sunmaz. Kazıyı yapan,

temellerin Basileios’un Nea Kilisesi’ne ya da Hodegon Manastırı’na ait

olduğunu önermiştir ancak bunların ikisi de olası görünmemektedir:

Burası Hodegon olamayacak kadar güneydedir ve duvar işçiliğinin ta-

rihi Nea Kilisesi olamayacak kadar yenidir. Aynı zamanda, ikonografi-

nin Zoodokhos Pege olarak okunması da olası değildir, çünkü ayazma-

nın tarihi bu tasvirin gelişmesinden önceye dayanır.15 Kimliği ne olursa

olsun ayazmanın, günümüze ulaşmamış daha yukarı seviyedeki bir bi-

nanın altyapısının eklentisi olduğu açıktır. Ne önceden planlanmış ne

de zengin biçimde döşenmiştir.

Kurtarıcı Philanthropos ayazması, on altıncı yüzyılda üzerine İncili

Köşk’ün de inşa edildiği deniz surlarında yer alıyordu (Şek. 3). Orto-

doks Hıristiyanlar, Topkapı Sarayı’nın içinde bulunmasına rağmen, on

dokuzuncu yüzyıla kadar ayazmayı ziyaret etmeyi sürdürdü.16 Mekânın

kimliği ayazmanın kullanımının Osmanlı döneminde de sürmesiyle be-

lirlenmiştir. Aleksios Komnenos’un hükümdarlığı sırasında, manastırın

inşa edildiği on ikinci yüzyılın başlarında kurulmuş olabilir ama hacı-

lar tarafından sık sık geç Bizans döneminde ziyaret edilmiştir. Aşağıda

kuzeye doğru konumlanmış olan kilise İsa’nın mucizevi bir biçimde gö-

rünmesi ve Aziz Aberkios’un naaşının burada bulunmasıyla da dikkat

çekmiştir. Köşkün arkasında, iki kulenin birleştiği yerde, Bizans altya-

pısının içinde bir geçide tuğla bindirme kemeri olan derin bir niş yerleş-

tirilmiştir. Bunlar ayazma şapelinden kalan son kalıntılar olabilir. Suya

deniz surlarının hem içinden hem de dışından ulaşılabildiği görülmek-

tedir. Köşkün payandalarının altından, merdivenlerle dikdörtgen bir

havuza ulaşılır; su burada toplanır, görünüşe bakılırsa taşar ve böylece

şifa güçlerini sahildeki kumlara taşır (Şek. 4).

Deniz surlarının dışındaki alan, on dördüncü ve on beşinci yüzyıllarda

şifa gücü için ziyaret edilirdi. Rus hacıların seyahat notlarında da bura-

dan devamlı bahsedilir. Zosima, “Kilisenin altında kutsal su var ve sayı-

sız hasta ve cüzzamlı ayaklarını kuma gömerek şifa buluyor,” der. Adı bi-

linmeyen bir Rus da aynı biçimde, kutsal suya yakın denizin kıyısında-

ki kuma hasta ayaklarını gömen kişilerin de benzer şeyler yaptığını an-

15 F. Düzgüner, “Anaplous ve Prookthoi’de Yeni Buluntular,” Istanbul, ed. N. Başgelen

ve B. Johnson (İstanbul, 2002), 32–50, buranın Nea Kilisesi ya da Hodegon veya ikisi

birden olabileceğini ileri sürer; F. Tülek, “A Fifth Century Floor Mosaic and a Mural

of Virgin of Pege in Constantinople,” Cahiers archéologiques 52 (2008), 23–30, resmin

on birinci yüzyılın ortasına veya on ikinci yüzyıla dayandığını söyler ve ikonografiyi

Balıklı Meryemi’ne atfeder.

16 Demangel ve Mamboury, Quartier des Manganes, 49–68 ve lev. 10.

Şek. 6 Zoodokhos Pege (Balıklı) ayazmasının mevcut durumu, 2013

(fotoğraf: Robert Outsterhout).

Fig. 6 The current state of the Zoodochos Pege hagiasma, 2013

(photo: Robert Ousterhout).

73

which had water flowing from the hands. The excavators suggested that

this was originally part of a hagiasma, perhaps that associated with the

Savior Philanthropos Monastery.18 Although elegantly carved, the origi-

nal context of the relief remains unclear. The Virgin’s orans pose with

pierced hands corresponds to a variety of surviving relief sculptures now

in Athens, Thessalonike, Berlin, Venice, and Ravenna.19 Of course, it also

resembles the description of the famed relief in the imperial bath at the

Blachernai, noted above. While it is unlikely that the relief found at the

Mangana came from the Blachernai, it indicates the popularity of the

image in the middle Byzantine centuries. Moreover, it suggests that the

same iconography could be used interchangeably at holy springs, perhaps

in the process borrowing from the aura of the Blachernai shrine, using

the miraculous associations of one site to empower another. The pose

of the Theotokos in the Amiral Tadfil hagiasma is also similar; the later

development of the Zoodochos Pege iconography maintains the same

pose, although the water flows from the fountain beneath the orans The-

otokos. A much later reflection of the same iconography may be found in

the Tyler Davidson Fountain in Cincinnati, Ohio, in which the “Genius

of Water” raises both hands, with water gushing from her palms.20

The best documented of the hagiasmata of Byzantine Constantinople

was the kataphyge at the Monastery of the Zoodochos Pege, which lay

just outside the land walls near the Pege (Balıklı) Gate.21 The monastery

buildings disappeared in the Ottoman period, although the spring con-

tinued to be visited. The present structures were built after 1833 (Fig.

6). Texts attribute the discovery of the miraculous spring to Leon I prior

to his accession, and describe several churches within the monastery: a

large, domed church, built by Justinian and rebuilt by Basil, dedicated

to the Theotokos; chapels dedicated to St. Eustratios and St. Anne; and

the famous refuge dedicated to the Theometor, built by Leon I in the

late fifth century. This latter structure “descends into the ground no less

than that which is seem above ground.”22 Its nave was three times as long

as it was wide, with a dome raised above arches. From either side, marble

stairs led down to the spring, set within a space said to be about twelve

feet wide. Additional steps led to the upper part of the spring, which was

fronted by a perforated font from which the water was distributed. All

18 Ibid., 153–61 and pl. 14; see also A. Paribeni, “La Vergine e l’acqua: le icone in

marmo dell’Oriente nel contest dei santuari mariani di Costantinopoli, “ in Deomene:

l’immagine dell’orante tra Oriente e Occidente, ed. A. Donati and G. Gentile (Ravenna,

2001), 40–43.

19 For the iconography, see Ousterhout, “Virgin of the Chora,” 94–96; N. P. Ševčenko,

“Virgin Blachernitissa,” Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium (Oxford, 1991), 3:2170–71.

20 See the Fountain Square Web site, http://myfountainsquare.com/features-of-the-

square/the-fountain.

21 Janin, Églises et les monasteries, 223–32; Talbot, “Holy Springs,” 160–67, for much of

what follows.

22 Xanthopoulos, Ecclesiastical History 15: A.-M. Talbot, trans., “The Anonymous

Miracles of the Shrine of the Pege,” in Miracle Tales from Byzantium, trans. S. Johnson

and A.-M. Talbot (Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2012).

latıyor ve şunları söylüyor; “Kurtçuklar bacaklarından ve bütün beden-

lerinden çıktığında sağlıklarına kavuşurlardı.”17

Bu alanın tam kuzeyinde kazı yapanlar Meryem Ana’nın mermer kabart-

ma bir ikonasının kırılmış parçalarını, bir sarnıçta buldular. İnce işçilikli

eserde, Meryem Ana bir kaidenin üzerinde, ellerini dua eder şekilde kal-

dırırken betimlenmiştir (Şek. 5). Günümüze ulaşan tek (sağ) el, yukarı-

da belirtilen, ellerinden su akan Blakhernai tasvirinin tanımlarına uyan

bir biçimde delinmiştir. Kazı yapanlar bunun aslen bir ayazmaya ait ol-

duğunu, belki de Kurtarıcı Philanthropos Manastırı’yla bağlantılı ol-

duğunu iddia ediyor.18 Çok zarif biçimde oyulmuş olmasına karşın, ka-

bartmanın özgün bağlamı belirsiz kalmıştır. Meryem Ana’nın elleri de-

linmiş halde dua eder şekildeki pozu, Atina, Selanik, Berlin, Venedik ve

Ravenna’da bulunan, bugüne kadar gelmiş çeşitli kabartmalara benzer.19

Tabii bu aynı zamanda, yukarıda anılan Blakhernai’deki imparatorluk ha-

mamındaki ünlü kabartmanın tarifine de uyar. Mangana’da bulunan ka-

bartmanın Blakhernai’den gelmiş olması muhtemel değil ama bu tasvirin

orta Bizans döneminde ne kadar popüler olduğuna işaret etmektedir. Ay-

rıca, aynı ikonografinin değişimli olarak farklı ayazmalarda kullanılma-

sı, Blakhernai’deki kutsal mekânın aurasının ödünç alınıp, bu mekânın

17 G. Majeska, Russian Travelers to Constantinople in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Centuries, Dumbarton Oaks Studies 19 (Washington, D.C., 1984), 371–74.

18 A.g.e, 153–61 ve lev. 14; ayrıca bkz. A. Paribeni, “La Vergine e l’acqua: le icone in

marmo dell’Oriente nel contest dei santuari mariani di Costantinopoli, “ Deomene:

l’immagine dell’orante tra Oriente e Occidente, ed. A. Donati ve G. Gentile (Ravenna,

2001), 40–43.

19 İkonografi için bkz. Ousterhout, “Virgin of the Chora,” 94–96; N. P. Ševčenko,

“Virgin Blachernitissa,” Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium (Oxford, 1991), 3:2170–71.

Ş ek. 7 Zoodokhos Pege Mozaiği, Kariye, yak. 1340 (fotoğraf: Carroll Wales, Dumbar-

ton Oaks Image Collection and Fieldwork Archives’ın izniyle).

Fig. 7 Mosaic of the Zoodochos Pege, Chora, ca. 1340 (photo by Carroll Wales, cour-

tesy Dumbarton Oaks Image Collection and Fieldwork Archives).

74

of this sounds similar to the situation one finds today inside the crypt,

whose lateral walls look suspiciously Byzantine. The crypt was divided

into two parts by a covered channel with two openings. Mud was extract-

ed from one channel to be used in cures.

The waters of the spring are credited with numerous miraculous cures. Some

pilgrims chose to take vials of the holy water with them, but the texts indicate

that many of the infirm incubated at the site as well. Both the crypt itself and

the large Justinianic church were used as places of incubation, the latter pos-

sibly as an overflow area when all the space around the spring was occupied.

According to the descriptions of the site, the most impressive element in the

crypt was the mosaic image of the Theotokos in the dome above the font,

which is described by Xanthopoulos. It seems to have represented what was

to become the standard iconography for representing the Virgin as the Life-

giving Source (or Life-receiving Spring), bust length, with or without the

Christ child, above a basin from which water flows, perhaps derived from

the Blachernitissa iconography. An early version, without the child, appears

in a tomb at the Chora Monastery, ca. 1340 (Fig. 7). Xanthopoulos writes:

mucizevi çağrışımlarının diğer mekânların kutsallığını güçlendirmek

için kullanıldığını da akla getiriyor. Amiral Tadfil ayazmasındaki Mer-

yem Ana’nın pozu da buna benzemektedir; Zoodokhos Pege ikonogra-

fisi daha sonra gelişmiş olmasına rağmen aynı pozu muhafaza eder, an-

cak su dua eden Meryem Ana’nın altındaki çeşmeden akar. Aynı ikonog-

rafinin çok daha geç bir yansıması, Ohio-Cincinnati’deki Tyler Davidson

Fıskiyesi’ndeki, kaldırdığı iki elinin avuçlarından su fışkıran “Suyun Da-

hisi” adlı eserde de görülebilir.20 Bizans Konstantinopolisi ayazmalarının

en iyi belgelenmiş olanı, surların hemen dışında Balıklı (Pege) Kapısı’nın

yakınında bulunan Zoodokhos Pege Manastırı’ndaki kataphyge’dir.21

Manastır binaları Osmanlı döneminde yok olsa da ayazma ziyaret edil-

meye devam etti. Bugünkü yapılar 1833’ten (Şek. 6) sonra inşa edilmiştir.

Metinler mucizevi ayazmanın keşfini, tahta çıkmasından önce I. Leon’a

atfeder ve manastırın içinde çeşitli kiliseler bulunduğunu anlatır: Iousti-

20 Fıskiye Meydanı’nın web sitesi için bkz., http://myfountainsquare.com/features-of-

the-square/the-fountain.

21 Janin, Églises et les monasteries, 223–32; Talbot, “Holy Springs,” 160–67, birçok

anlatılacak konu için.

Şek. 8 Aziz Sampson Hastanesi alanındaki

sarnıçların yerini gösteren plan (W. Müller-

Wiener, Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls

[Tübingen, 1977], şek. 95).

Fig. 8 Plan showing the location of cisterns in

the area of the Hospital of St. Sampson (from

W. Müller-Wiener, Bildlexikon zur Topographie

Istanbuls [Tübingen, 1977], fig. 95).

75

In the middle of the dome, where there is the ceiling of the church, the artist

perfectly depicted with his own hands the life-bearing Source [i.e., the Vir-

gin] who bubbles forth from her bosom the most beautiful and eternal infant

in the likeness of transparent and drinkable water which is alive and leaping;

upon seeing it one might liken it [the Source] to a cloud making water flow

down gently from above, as if a soundless rain, and from there [sc. above]

looking down toward the water in the phiale so as to render it effective [i.e.,

miracle-working], incubating it, so to speak, and rendering it fertile.23

23 Xanthopoulos 15.25–26: trans. Talbot, “Holy Springs,” 165; for the iconography,

see N. Teteriatnikov “The Image of the Virgin Zoodochos Pege: Two Questions

Concerning Its Origin,” in Images of the Mother of God: Perceptions of the Theotokos in

Byzantium, ed. M. Vasilaki (Aldershot, 2005), 225–38.

nianos tarafından yaptırılan ve Basileios tarafından tekrar inşa ettirilen,

Meryem Ana’ya adanmış büyük kubbeli bir kilise; Aziz Eustratios ve Azi-

ze Anna’ya adanmış şapeller ve beşinci yüzyılın sonunda I. Leon tarafın-

dan inşa ettirilen, Theometor’a (Tanrı’nın Anası) adanmış ünlü sığınak.

Bu son yapının “toprağın üstünde görünen kısmı kadar zeminin altına

inen kısmı vardır.”22 Nefi genişliğinin üç katı kadardır, kubbesi kemerle-

rin üzerine oturur. İki taraftan da, mermer merdivenlerle, dört metreye

yakın genişlikte olduğu söylenen bir alana kurulmuş olan ayazmaya ini-

lir. Başka merdivenler ayazmanın üst kısmına uzanır, ayazmanın önün-

de, suyun dağıtıldığı oluklu bir kurna bulunur. Bütün bunlar, yan duvar-

ları şüphe götürmeyecek biçimde Bizans dönemine ait görünen krypta-

nın bugünkü haline benzer. Krypta, iki açıklığı olan örtülü bir kanalla iki-

ye ayrılmıştır. Bir kanaldan şifalarda kullanılmak üzere çamur çıkartılır.

Ayazmanın sularının sayısız mucizevi şifayı sağladığına inanılır. Bazı ha-

cılar kutsal suyla dolu şişeleri yanlarında götürmeyi tercih etmişlerdi ama

metinler birçok hastanın mekânda gecelediğini de gösterir. Hem krypta

hem de büyük Ioustinianos kilisesi inkubasyon mekânıydı ve kilise büyük

bir ihtimalle, ayazmanın çevresindeki alan dolduğunda kullanılıyordu.

Mekânın tanımlarına bakılırsa, kryptadaki en etkileyici unsur,

Ksanthopoulos’un anlattığı, havuzun üstündeki kubbede yer alan Mer-

yem Ana’nın mozaik tasviridir. Bu, daha sonra Meryem Ana’nın Hayat

Veren Kaynak (veya Hayat Pınarı) olarak tasvirinin standart bir ikonog-

rafisi haline gelecektir; büst şeklinde, yanında bazen çocuk İsa’yla ba-

zen yalnız, içinden su akan bir kurnada belki de Blakhernitissa ikonog-

rafisinden alınmış bir tasvir. Çocuksuz, daha eski bir versiyon Kariye

Manastırı’ndaki bir mezarda (yak. 1340) görülür (Şek. 7). Ksanthopo-

ulos şöyle yazar:

Kilisenin tavanının bulunduğu kubbenin ortasında, sanatçı kendi el-

leriyle, göğsünden, saydam ve temiz suya benzeyen, en güzel ve ebe-

di çocuğun köpükler halinde, canlı sıçradığı hayat veren Kaynağı

[yani, Meryem Ana’yı] mükemmel biçimde resmetmiştir; bunu gö-

renler, onu [Kaynağı], yukarıdan aşağıya sanki sessiz bir yağmur gibi,

usulca su akıtan ve oradan [sc. yukarıdan] aşağıya phiale‘deki suya ba-

kan ve onun etkili olmasını (yani mucize yaratmasını) sağlayan, de-

yim yerindeyse onu istihare eden ve verimli hale getiren bir buluta

benzetebilir.23

22 Ksanthopoulos, Ecclesiastical History 15: A.-M. Talbot, çev., “The Anonymous

Miracles of the Shrine of the Pege,” Miracle Tales from Byzantium, çev. S. Johnson ve

A.-M. Talbot (Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2012).

23 Ksanthopoulos 15.25–26: çev. Talbot, “Holy Springs,” 165; ikonografi için bkz. N.

Teteriatnikov “The Image of the Virgin Zoodochos Pege: Two Questions Concerning

Its Origin,” Images of the Mother of God: Perceptions of the Theotokos in Byzantium, ed.

M. Vasilaki (Aldershot, 2005), 225–38.

Şek. 9 Pantokrator Manastırı alanındaki sarnıçların yerini gösteren plan (Müller-Wien-

er, Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls, şek. 237).

Fig. 9 Plan showing the location of cisterns in the area of the Pantokrator Monastery

(from Müller-Wiener, Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls, fig. 237).

76

It is an evocative and poetic image: the reflection of the glittering mosaic

upon the surface of the water fills it with life and provides its miraculous

power. One can imagine the image seeming to move with the ripples on the

surface of the water. At the Hodegon and at the Blachernai, the miraculous

associations originally assigned to the hagiasmata seem to have been subse-

quently overshadowed by the important site-related icons—the so-called

Hodegetria and the Blachernitissa. In contrast, if one follows the text of

Xanthopoulos, the mosaic image at the Pege empowered the spring, trans-

ferring the life-giving associations of the icon to the water and vice versa.

The iconography of the image depends upon and represents the miracu-

lous associations of the waters of the spring, as the Virgin becomes identi-

fied with the source. Perhaps it is best to say that the two—the image and

the water, the icon and the substance—worked in concert.

* * *

As water functioned as an agent in miraculous cures, one wonders if

it also played a similar role in hospitals and medical establishments. A

brief look at the hospitals of Byzantine Constantinople indicates that a

bath was a standard feature in the architecture and that the bathing of

patients was common in treating the infirm. From the establishment of

the empire, xenones (hospitals) were common philanthropic establish-

ments, often associated with monasteries.24 Of the early hospitals, the

one associated with St. Sampson was the most important. Although it

is unclear when it was founded or when exactly St. Sampson lived—

he is credited with curing Justinian—its founding may be as old as the

fourth century.25 The complex was rebuilt by Justinian after the Nika

riots. Extensive but only partially excavated substructures between

Hagia Sophia and Hagia Eirene are usually assigned to the hospital, and

these include extensive cisterns. The limited evidence suggests build-

ings and rooms organized around large internal courtyards, perhaps

with a connection to the narthex of Hagia Eirene (Fig. 8).26 The area

outside the present Topkapi Palace wall and closer to Hagia Sophia has

not been excavated.

Following ancient writings, medical texts popular in the early Byzantine

period indicate the importance of bathing regimens in curing diseases. As a

consequence, xenones regularly included a bath, which allowed the medi-

cal staffs to integrate bathing into their treatments. One can see that the ex-

tensive cisterns at the Hospital of St. Sampson were required for the regular

operation of the therapeutic baths.

24 T. Miller, The Birth of the Hospital in the Byzantine Empire (Baltimore, Maryland,

1985).

25 Ibid., 80–82.

26 W. Müller-Wiener, Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls (Tübingen, 1977), 112–13.

Bu çok canlı ve şiirsel bir tasvirdir: ışıltılı mozaiğin suyun üzerindeki

yansıması onu yaşam dolu bir hale getirir ve mucizevi gücünü sağlar.

Tasvirin, suyun dalgalanmasıyla hareket ediyormuş gibi görüneceğini

hayal etmek mümkün. Hodegon ve Blakhernai’deki ayazmalara atfedi-

len mucizevi unsurlar zaman içinde mekânla bağlantılı önemli ikona-

ların—Hodegetria ve Blakhernitissa—gölgesinde kalmıştır. Bu duru-

mun aksine, Ksanthopoulos’un metni, Balıklı’daki mozaik tasvirinin,

ikonanın hayat-veren unsurlarının suya ve aynı şekilde sudan ikonaya si-

rayet etmesiyle, ayazmayı güçlendirdiğini belirtir. Tasvirin ikonografi-

si ayazmanın sularının mucizevi unsurlarıyla bağlantılıdır ve bunu tem-

sil eder çünkü Meryem Ana kaynakla özdeşleştirilmiştir. Belki de, ikisi-

nin—tasvir ve suyun, ikona ve özün—uyum içinde çalıştığını söylemek

en doğrusudur.

* * *

Su mucizevi şifalarda bir araç olarak işlev gördüğünden, hastanelerde ve

tıbbi kurumlarda da benzer bir rol oynayıp oynamadığını merak edebili-

riz. Bizans Konstantinopolisi’nin hastanelerine kısa bir bakış hamamın

hastane mimarisinin standart bir özelliği ve hastaların yıkanmasının da

yaygın bir tedavi olduğunu gösterir. İmparatorluğun kuruluşundan iti-

baren ksenones (hastaneler), genellikle manastırlara bağlı, yaygın hayır-

sever kurumlar olmuştur.24 İlk hastanelerden Aziz Sampson’la bağlantı-

lı olanı en önemlisiydi. Ne zaman kurulduğu ve Aziz Sampson’un tam

olarak ne zaman yaşadığı belirsiz olmasına rağmen—Ioustinianos’u te-

davi ettiği iddia edilir—kuruluşu dördüncü yüzyıla kadar dayanıyor

olabilir.25 Tesis, Nika ayaklanmasının ardından Ioustinianos tarafın-

dan tekrar inşa ettirilmiştir. Ayasofya ve Aya İrini arasındaki geniş an-

cak kısmen kazılabilmiş olan altyapıların genellikle hastaneye ait oldu-

ğu düşünülür ve bunlara muazzam sarnıçlar da dâhildir. Sınırlı bulun-

tular, geniş iç avlular çevresinde, belki Aya İrini’nin narteksiyle bağlan-

tısı olan binalar ve odaların varlığını akla getirir (Şek. 8).26 Bugünkü

Topkapı Sarayı duvarlarının dışında bulunan alan ve Ayasofya civarı ka-

zılmamıştır.

Erken Bizans döneminde popüler olan tıbbi metinler hastalıkların iyi-

leşmesinde hamamın tedavi şekillerindeki önemine işaret eder. Bunun

bir sonucu olarak ksenon’larda düzenli olarak, tıbbi personelin tedavile-

rini banyoyla tamamlamalarına imkân veren bir hamam dâhil edilmiş-

tir. Aziz Sampson Hastanesi’ndeki muazzam sarnıçların sağaltıcı ban-

yoların düzenli işlemesi için gerekli olduğu görülebilir.

24 T. Miller, The Birth of the Hospital in the Byzantine Empire (Baltimore, Maryland,

1985).

25 A.g.e, 80–82.

26 W. Müller-Wiener, Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls (Tübingen, 1977), 112–13.

77

The typikon of the Pantokrator Monastery, dated 1136, provides the

most detailed information about the physical form and organization of a

Byzantine hospital.27 The monastery also supported an old-age home and

presumably a leprosarium some distance away. The hospital was designed

to serve fifty patients suffering from different maladies, with ten beds as-

signed to those with wounds or fractures; eight to those with ophthalmia,

stomach illnesses, or other painful maladies; twelve for women; and the

remainder for the moderately ill. The fifty beds were to be arranged in five

ordines (wards or rows), with an extra bed in each ward for emergencies and

six additional beds for people unable to move. Each bed was to be provided

with a mattress and coverings. The building was heated by a large brazier,

with a smaller brazier in the surgery and another in the women’s ward. The

establishment also included two chapels (for men and women to worship

separately), a mill and bakery, a kitchen, and dining room. There were also

two latrines and a bath, the latter necessitated, as the typikon states, “since

those who are ill need to bathe.” Patients were to be routinely bathed twice

a week unless their condition required more frequent bathing. Doctors, as-

sistants, and orderlies were to assist in bathing the patients.

By contrast, the monks of the monastery and those in the old-age home

bathed twice a month in the monastery’s bath. As with the St. Sampson

hospital, the extensive cisterns around the Pantokrator likely supported the

regular operation of the monastery’s baths although it is unclear where in

relationship to the monastery the hospital stood.28 Unfortunately the area

around the great triple church has never been properly excavated, and the

hagiasma immediately to the west of the church appears to date from the

Ottoman period (Fig. 9). The waters used in the therapy of the hospital

came from manmade reservoirs, not miraculous springs, just as the cures

came from the hand of man and not a divine source.

27 Robert Jordan, trans., “Pantokrator,” in Byzantine Monastic Foundation Documents,

ed. J. Thomas and A. Hero (Washington, D.C., 2000), 2:757–68 (trans. R. Jordan);

Miller, Birth of the Hospital, 12–29; for an imaginative reconstruction see A. K.

Orlandos, Monasteriake architektonike (Athens, 1958), 223–30.

28 Müller-Wiener, Bildlexikon, pl. 237; N. Fıratlı and E. Yücel, “Some Unknown

Byzantine Cisterns of Istanbul,” Bulletin officiel du Touring et Automobile Club

Turquie, 120 ( January 1962).

Pantokrator Manastırı’nın 1136 tarihli typikon’u (vakfiyesi) bir Bizans

hastanesinin fiziksel biçimi ve örgütlenmesiyle ilgili en ayrıntılı bilgi-

yi verir.27 Manastırda aynı zamanda bir huzurevi ve biraz ileride olası-

lıkla cüzzamlılar için bir hastane de vardı. Hastane farklı hastalıklardan

muzdarip elli hastaya hizmet vermek üzere tasarlanmıştı, yarası veya kı-

rığı olanlara ayrılmış on tane, göz hastalıkları, mide hastalığı ve diğer

ağrılı hastalıklardan muzdarip olanlar için de sekiz tane yatak vardı; on

iki yatak kadınlara ayrılmıştı ve kalan yataklar ise daha hafif hastalıkla-

rı olanlar içindi. Elli yatak beş ordines (koğuş ya da sıra) halinde düzen-

lenmişti, her koğuşta acil durumlar için fazladan bir yatak bulunuyor-

du ve hareket edemeyen insanlar için de altı ek yatak mevcuttu. Her ya-

takta bir döşek ve örtüler vardı. Bina büyük bir mangalla ısıtılıyordu,

ameliyathanede daha küçük bir mangal ve kadınlar koğuşunda bir tane

daha mangal vardı. Tesiste aynı zamanda (kadın ve erkeklerin ayrı ayrı

ibadet etmesi için) iki şapel, bir değirmen ve bir fırın, bir mutfak ve bir

yemek odası bulunuyordu. Ayrıca iki açık tuvalet ve typikon’un ifade et-

tiği üzere “hasta olanların banyo yapması gerektiğinden” zaruri olan bir

hamam da vardı. Hastalar, durumları daha sık banyo yapmalarını gerek-

tirmedikçe düzenli olarak haftada iki kez yıkanırdı. Doktorlar, asistan-

lar ve hademeler hastaların yıkanmasına yardımcı olurdu.

Buna karşılık, manastırın rahipleri ve huzurevindekiler ayda iki kere

manastırın hamamında banyo yapardı. Hastanenin manastırın ne tara-

fında olduğu muğlaktır ancak Aziz Sampson hastanesinde olduğu gibi,

Pantokrator’un etrafındaki muazzam sarnıçlar da büyük ihtimalle ma-

nastırın hamamlarının düzenli işlemesine destek veriyordu.28 Büyük

üçlü kilisenin çevresindeki alan maalesef hiçbir zaman doğru düzgün

kazılmamıştır ve kilisenin hemen batısındaki ayazma Osmanlı dönemi-

ne ait görünmektedir (Şek. 9). Hastanenin tedavisinde kullanılan sular,

mucizevi pınarlardan değil, insan eliyle yapılmış haznelerden geliyor-

du; tıpkı burada şifa verenin ilahi bir kaynak değil insan eli olduğu gibi.

27 Robert Jordan, çev., “Pantokrator,” Byzantine Monastic Foundation Documents, ed.

J. Thomas ve A. Hero (Washington, D.C., 2000), 2:757–68 (çev. R. Jordan); Miller,

Birth of the Hospital, 12–29; hayali bir rekonstrüksiyon için bkz. A. K. Orlandos,

Monasteriake architektonike (Athens, 1958), 223–30.

28 Müller-Wiener, Bildlexikon, lev. 237; Fıratlı ve Yücel, “Some Unknown Byzantine

Cisterns of Istanbul,” Bulletin officiel du Touring et Automobile Club Turquie,

120 (Ocak 1962).

Related Documents