-

8/13/2019 TRATEGICSUPPLY CHAINMANAGEMENT: IMPROVINGPERFORMANCETHROUGHA CULTURE OF COMPETITIVENESSAND KNOWLEDGE DEVELOPMENT

1/19

Strategic Supply Chain Management: Improving Performance through a Culture ofCompetitiveness and Knowledge DevelopmentAuthor(s): G. Tomas M. Hult, David J. Ketchen Jr. and Mathias ArrfeltSource: Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 28, No. 10 (Oct., 2007), pp. 1035-1052Published by: Wiley

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20141968.Accessed: 19/11/2013 11:07

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at.http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

WileyandJohn Wiley & Sonsare collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Strategic

Management Journal.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 168.156.40.175 on Tue, 19 Nov 2013 11:07:50 AM

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=blackhttp://www.jstor.org/stable/20141968?origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/stable/20141968?origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=black -

8/13/2019 TRATEGICSUPPLY CHAINMANAGEMENT: IMPROVINGPERFORMANCETHROUGHA CULTURE OF COMPETITIVENESSAND KNOWLEDGE DEVELOPMENT

2/19

Strategie Management JournalStrat. Mgmt. J, 28: 1035-1052 (2007)

Published online 17May 2007 inWiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com) DOI: 10.1002/smj.627Received 14 October 2005; Final revision received 20 March 2007

STRATEGICSUPPLY CHAINMANAGEMENT:IMPROVINGPERFORMANCETHROUGHA CULTUREOF COMPETITIVENESSAND KNOWLEDGEDEVELOPMENT

G. TOMAS M. HULT,1*DAVIDJ. KETCHENJR2 and MATHIAS ARRFELT11Eli Broad Graduate School of Management, Michigan State University, East Lansing,Michigan, U.S.A.2 College of Business, Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama, U.S.A.

For many firms, using their supply chains as competitive weapons has become a central elementof

thestrategic management process

in recent years. Drawing on the resource-based view andtheory from the organizational learning and information-processing literatures, this study usesa sample of 201 firms to examine the influence of a culture of competitiveness and knowledge

development on supply chain performance in varied market turbulence conditions. We foundthat synergies exist between a culture of competitiveness and knowledge development: theirinteraction has a positive association with performance. In addition, based on behavioral andcontingency theories, we found that market turbulence moderates these relationships, having a

positive influence on the knowledge development-performance link and a negative influence onthe culture of competitiveness-performance link. Managers who are confident about the level of

market turbulence they will face can use this sense to decide whether to emphasize developingeither a culture of competitiveness or knowledge development in their supply chains. For those

firms whose managers are unlikely to be able to predict the degree of turbulence they will faceover time, a focus on both a culture of competitiveness and knowledge development is critical toensuring success. Copyright ? 2007 JohnWiley & Sons, Ltd.

INTRODUCTIONThe quest to discover the determinants of firm performance has long been central to the strategicmanagement field. Indeed, many leading scholars have argued that building knowledge aboutwhy some firms outperform others is the cornerstone of the field (e.g., Hitt, Boyd, and Li,2004; Rumelt, Schendel, and Teece, 1994; Summer et al., 1990). In recent years, the nature ofcompetition has increasingly shifted toward 'supply chain vs. supply chain' struggles (Handfield

Keywords: strategic supply chain management; performance; culture; knowledge development; resource-basedview

^Correspondence to: G. Tomas M. Huit, Eli Broad GraduateSchool of Management, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824-1121, U.S.A. E-mail: [email protected]

Copyright ? 2007 JohnWiley & Sons, Ltd.

and Nichols, 2002; Slone, 2004). Supply chainsare value-adding relations of partially discrete, yetinter-reliant, units that cooperatively transform rawmaterials into finished products through sequential, parallel, and/or network structures (Bowersox,

Closs, and Stank, 1999). When rivals such as UPSand FedEx clash, it is not merely their individualcapabilities, but rather the collective capabilities oftheir respective supply chains, that determine theoutcome.

Historically, the strategic management field hasnot devoted much empirical attention to supplychains, while related disciplines such as marketingand operations management have long emphasized the performance implications of operationalactivities. For example, in a review of the operations management literature, Anderson, Cleveland,and Schroeder (1989: 134) noted: 'proper strategic

?WILEYlitferScience'

This content downloaded from 168.156.40.175 on Tue, 19 Nov 2013 11:07:50 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 TRATEGICSUPPLY CHAINMANAGEMENT: IMPROVINGPERFORMANCETHROUGHA CULTURE OF COMPETITIVENESSAND KNOWLEDGE DEVELOPMENT

3/19

1036 G. T. M. Huit, D. J. Ketchen Jr and M. Arrfeltpositioning or aligning of operations capabilities can significantly impact competitive strengthand business performance of an organization.' Inrecent years, a small body of strategic management research has begun to examine 'strategicsupply chain management'?the use of a supplychain not merely as ameans to get products wherethey need to be, but also as a tool to enhancekey outcomes (e.g., Huit, Ketchen, and Nichols,2002; Huit, Ketchen, and Slater, 2004). The valueof strategic supply chain management is reflectedin how firms such as Wal-Mart, Zara, Toyota,and Dell have used their supply chains as competitive weapons to gain advantages over peers.

Meanwhile, failing to strategically manage supplychains offers serious negative consequences. AsLee (2004) describes, for example, supply chaindifficulties led Cisco to write off $2.25 billion ininventory in 2001 and led Motorola to lose manycrucial early camera phone sales in 2003. Giventhe implications for profits and sales, it is perhapsnot surprising that the announcement of a majorsupply chain problem erodes a firm's market valueby an average of 10 percent (Hendricks and Singhal, 2003).Like the Huit et al. studies, we focus on explaining order fulfillment cycle time?the length oftime between taking an order and delivery of theneeded product to the customer. As Ray, Barney,and Muhanna (2004) note, measuring the effectiveness of business processes helps test resourcebased logic and taps into the competitive advantages developed within important activities. Cycletime is a key metric for directly assessing supply chain functioning (Nichols, Retzlaff-Roberts,and Frolick, 1996). More importantly, cycle timeis central to a firm's strategic success. As Handfield and Nichols (2002: 13) note, cycle time notonly has 'a direct linkage to profits' at the firmlevel, but excellence in cycle time allows firmsto 'grow faster and earn higher profits relative toother firms in their industry, increase market sharethrough early introduction of new products, control overhead and inventory costs, and move topositions of industry leadership.' In contrast to thesingle-organization focus of the Huit et al. studies,we examine the supply chains of multiple firms.This design feature allows us to shed new light onthe critical issue of why some firms outperform

others.This paper is devoted to taking what we viewas a next logical step in the emerging stream

Copyright ? 2007 JohnWiley & Sons, Ltd.

of research on strategic supply chain management. We build on Huit et al. (2002), who introduced the concept of 'cultural competitiveness'as a reflection of innovativeness, entrepreneurial,and learning orientations,1 and Huit et al. (2004),who examined the knowledge development process, both within the context of achieving superior performance. Learning is a key element ofboth studies but the frameworks tested are distinct. Taking the previous studies' shared concern for learning as our point of departure, webuild on the resource-based view (Wernerfelt,1984), and theory from the organizational learning(Huber, 1991) and information-processing (Daftand Weick, 1984) literatures to argue that neithera culture of competitiveness nor knowledge development by itself is sufficient to achieve superiorperformance in varied market conditions. Instead,these phenomena operate in tandem to achievedesired outcomes. Using data from 201 firms,we apply a sophisticated technique?parsimoniouslatent-variable interaction modeling (e.g., Ping,1995)?to highlight the potential value of two phenomena that together can facilitate superior cycletime.

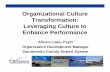

THEORETICAL FOUNDATION ANDHYPOTHESESRecent research by Ray et al. (2004) andSchroeder, Bates, and Junttila (2002) highlightsthe value of examining resources within a firm'soperations management process. In line with thiswork, Figure 1 presents our conceptual model,which is intended to explain cycle time in supplychains. The model includes two higher-order factors?culture of competitiveness and knowledgedevelopment?composed of seven first-order indicators (each of which, in turn, has a set of reflectiveindicators?see Appendix 1), as well as their interaction. Culture of competitiveness (CC) is definedas the 'degree to which [supply] chains are predisposed to detect and fill gaps between what

Strat. Mgmt. J., 28: 1035-1052 (2007)DOI: 10.1002/smj

1Huit, Ketchen, and Nichols (2002) introduced the concept of'cultural competitiveness.' As an anonymous referee pointed out,the term 'cultural competitiveness' seems to denote a comparisonof one firm's competitive characteristics against those of anotherto see which is more successful. Based on this referee's suggestion, we adopt the term 'culture of competitiveness.' This betterreflects the underlying concept's focus on the degree to whichvalues and beliefs centered on customer service are developed.We

appreciate the referee's insightson this issue.

This content downloaded from 168.156.40.175 on Tue, 19 Nov 2013 11:07:50 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 TRATEGICSUPPLY CHAINMANAGEMENT: IMPROVINGPERFORMANCETHROUGHA CULTURE OF COMPETITIVENESSAND KNOWLEDGE DEVELOPMENT

4/19

Strategie Supply Chain Management 1037

LearningOrientation

InnovativenessOrientation

EntrepreneurialOrientation

KnowledgeAcquisition

InformationDistribution

SharedMeaning

AchievedMemory

MarketTurbulence

Culture ofcompetitiveness

InteractionH3 (+) I EffectsiCC'Km

KnowledgeDevelopment H2(+)

Cycle TimePerformance?.

Firm Age

Firm Size

- Hypothesized Relationship? First-Order Latent IndicatorsControl Relationship

Figure 1. A model of culture of competitiveness, knowledge development, and cycle time performance in supplychains

the market desires and what is currently offered'(Huit et al., 2002: 577). Drawing on the resourcebased view (Wernerfelt, 1984), CC is conceptualized as an unobservable latent factor (Godfreyand Hill, 1995) that is reflected in three orientations?innovativeness, entrepreneurial, and learning?that affects performance. The latter orientation?learning?is the critical element that helpsintegrate CC and knowledge development. Specifically, learning orientation focuses on the valuesand beliefs that direct supply chains toward thebehaviors required for knowledge development.

Knowledge development (KD), on the otherhand, is a phenomenon wherein actions lead toknowledge acquisition, information distribution,shared meaning, and achieved memory in the supply chain (Huit et a/., 2004; cf. Huber, 1991). Assuch, a learning orientation is reverberated in a setof knowledge-seeking values (Baker and Sinkula,1999) while KD is reflected by knowledge

producing behaviors (e.g., Grant, 1996). Researchon organizational learning (e.g., Huber, 1991) andinformation processing (Daft and Weick, 1984)serve as the primary foundation for the fourfirst-order indicators of KD?knowledge acquisition, information distribution, shared meaning,and achieved memory?and its higher-order relationship with performance in supply chains. TheCopyright ? 2007 JohnWiley & Sons, Ltd.

broader learning literature (i.e., learning orientation and organizational learning) is the basis forintegrating CC and KD in the model (e.g., Argyrisand Sch?n, 1978; Hedberg, 1981; Nystr?m andStarbuck, 1984).

Culture of competitiveness in supply chainsAs Barney and Mackey (2005: 5) note, the continued theoretical development of the resource-basedview requires scholars to not 'simply correlateaggregate measures of resources' at the firm levelbut rather tomove their investigations to the levelsof analysis 'where resources reside.' Thus, theoryand empirical attention should be aimed 'at thelevel of the resource, not the level of the firm.'The supply chain offers one such level of analysis where resources reside, and resources' role atthis level can be prominent. Indeed, as Huit et al.(2002: 580) observe, because chain members donot all share 'a common organizational affiliation,the development of unique resources ... may bevital to chain outcomes.' In this sense, shared sup

ply chain resources can substitute for traditionalfeatures that bind members of a firm, such as structure, culture, and strategy (cf.Weick, 1987).

Building on the resource-based view, Huit et al.(2002) argue that a culture of competitiveness

Strut. Mgmt. 7., 28: 1035-1052 (2007)DOI: 10.1002/smj

This content downloaded from 168.156.40.175 on Tue, 19 Nov 2013 11:07:50 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 TRATEGICSUPPLY CHAINMANAGEMENT: IMPROVINGPERFORMANCETHROUGHA CULTURE OF COMPETITIVENESSAND KNOWLEDGE DEVELOPMENT

5/19

1038 G. T. M. Huit, D. J. Ketchen Jr and M. Arrfeltfunctions as an intangible strategic resource thatcan be developed by interaction and cooperationamong supply chain members. CC provides supply chain members with a pattern of shared valuesand beliefs that assert the importance of certainelements (and omit others) and drive the chain'sapproach to themarketplace. As such, CC is rootedin the broad phenomenon of 'culture' but is narrowly focused on a distinct set of cultural orientations?entrepreneurial, innovativeness, and learning?that lead supply chains to strategically fillgaps between customers' future desires and whatis currently offered.An entrepreneurial orientation is defined as thechain members' values associated with the pursuit of new market opportunities and the renewalof existing areas of supply chain activities (e.g.,Naman and Slevin, 1993). An innovativeness orientation refers to supply chain members' valuesassociated with new idea generation (i.e., members' openness to new ideas; Hurley and Huit,1998). A learning orientation is defined as members' values associated with the generation of newinsights that have the potential to shape supplychain activities (cf. Huber, 1991). Each of thesethree orientations is necessary, but individuallyinsufficient, for the emergence of the higher-orderintangible strategic resource of culture of com

petitiveness (Huit et al, 2002). Most importantly,rooted in the resource-based view, CC appearsto be a valuable, rare, and inimitable strategicresource in supply chains (Barney, 1986; Wernerfelt, 1984) that can provide a sustainable competitive advantage and enhanced performance (Huitet al., 2002). Thus, we expect that:

Hypothesis 1: Culture of competitiveness hasa positive association with cycle time performance.

Knowledge development in supply chainsHuber (1991: 90) describes four dimensions thatare paramount to learning efforts. Huit et al. (2004)built on these elements to develop a model ofknowledge development. The first dimension isknowledge acquisition?the process by whichentities, such as organizations or supply chains,obtain wisdom. Information distribution is the process by which information from different sourcesis shared. In supply chains, this sharing occursthroughout the chain, including its various nodes

Copyright ? 2007 JohnWiley & Sons, Ltd.

and members (Kohli, Jaworski, and Kumar, 1993).Information interpretation, or shared meaning, isthe process by which members develop commonunderstandings about data and events (Corner,Kinicki, and Keats, 1994). Given the lack of astrong culture in typical supply chains, shared

meanings of supply chain data and events areneeded to harness collective action (Huit et al,2004). Perhaps themost integral component of KDis 'organizational memory' (Huber, 1991), labeled'achieved memory' for the supply chain context byHuit et al. (2004) based on work by Moorman andMiner (1997). Memory is defined as the amountof knowledge, experience, and familiarity with thesupply chain process, its operations, and behaviors;it serves as the mechanism by which knowledgeis stored for future strategic use and, as such, iscritical as a 'launching' point for future learningbehaviors.

Theory from the organizational informationprocessing literature provides the basis for expecting that, as a group, the four dimensions shouldenhance supply chain performance. Informationprocessing theory argues that gathering, processing, and interpreting information is the primary jobof organized collectivities (Daft and Weick, 1984)such as supply chains (Bowersox et al., 1999).Research on 'strategic sensemaking' has extendedthis argument to demonstrate that informationprocessing activities profoundly shape the strategic decisions made within firms and the resultant outcomes (Meyer, 1982; Thomas, Clark, andGioia, 1993). The knowledge-based view (Grant,

1996) also supports a knowledge developmentperformance link. Building on the resource-basedview's notions of value, rarity, and inimitability,the knowledge-based view centers on the notionthat unique abilities to create and exploit wisdomcreate competitive advantages and thereby enhanceoutcomes

(e.g.,Huit et al., 2004). As such, withinthe supply chain context, our contention is that:

Hypothesis 2: Knowledge development has apositive association with cycle timeperformance.

Synergy between culture of competitivenessand knowledge developmentThe broader learning literature (e.g., Argyris andSch?n, 1978; Hedberg, 1981; Nystr?m and Starbuck, 1984) serves as the theoretical foundation

Strat. Mgmt. J., 28: 1035-1052 (2007)DOI: 10.1002/smj

This content downloaded from 168.156.40.175 on Tue, 19 Nov 2013 11:07:50 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 TRATEGICSUPPLY CHAINMANAGEMENT: IMPROVINGPERFORMANCETHROUGHA CULTURE OF COMPETITIVENESSAND KNOWLEDGE DEVELOPMENT

6/19

for learning being the key integrator of a culture of competitiveness and knowledge development in supply chains. While Huit et al. (2002,2004) developed both the CC and KD constructswithin supply chains, they did not integrate the twoconcepts. This is unfortunate because the learningorientation construct within the CC framework isfocused on the supply chain's knowledge-seekingvalues (Baker and Sinkula, 1999) that guide itsknowledge-producing behaviors within the KDdevelopment framework (e.g., Grant, 1996; Huber,1991). As such, learning is both themissing link inthe conceptualizations by Huit et al. (2002, 2004)and the resultant integrator of the two frameworks.In other words, their shared concern for learningsuggests that neither CC nor KD is sufficient tomaximize performance. Instead, they supplementand reinforce each other for a stronger strategiceffect than either alone can provide.For example, Baker and Sinkula (1999: 416)argue that 'if members of an organization [e.g.,supply chain] have an enhanced learning orientation, they will not only gather and disseminate information about markets but also constantlyexamine the quality of their interpretive storagefunctions and the validity of the dominant logicthat guides the entire process.' At the same time,stressing knowledge-producing behaviors in thesupply chain is likely to lead to the 'culture of competitiveness' infrastructure exemplified by the values inherent in a learning orientation (e.g., Slaterand Narver, 1995). Applied within supply chains,the expectation of a synergistic interaction betweenCC and KD is also consistent with Day's (1994)inside-out and outside-in processes that center onthe strategic interaction between superiority in process management, integration of knowledge, anddiffusion of learning. Based on this logic, weexpect that:

Hypothesis 3: The interaction between cultureof competitiveness and knowledge developmenthas a positive association with cycle time performance.

The moderating role of market turbulenceStarbuck's (1976) review of organizational taskenvironments provided a wealth of potentialdimensions that can affect firm strategy and operations. In our study, we draw from this literature to focus on market turbulence?the rateCopyright ? 2007 JohnWiley & Sons, Ltd.

Strategie Supply Chain Management 1039of change in the composition of customers andtheir preferences (Jaworski and Kohli, 1993)?asone critical element of the environment that theoretically has an influence on the relationshipsstudied in this research (e.g., Dess and Beard,1984). In addition, we place particular emphasison the notion thatmanagerial perceptions, particularly regarding market uncertainty, shape strategicchoice and decision making (Child, 1972; Duncan, 1972; Lawrence and Lorsch, 1967). Similarly,Sharfman and Dean (1991: 682) state that 'theenvironment is those parts of the external information flow that the firm enacts through attentionand belief.' One logical extension is that environmental perceptions and beliefs shape culture andbehavior (Dutton and Jackson, 1987).We expect that this argument also will holdtrue in supply chains. For example, one of behavioral theory's tenets is that organizational memory is dependent on the conditions in which thefirm operates (Cyert and March, 1963; Levitt and

March, 1988). Thompson (1967: 159) considereddealing with uncertainty to be the 'essence ofthe administrative process.' Accordingly, supplychains are likely to realize a positive influenceof market turbulence on the knowledge develop

ment-cycle time relationship given the dynamicnature of the behaviors involved in KD. Indeed,applying the concept of requisite variety (Ashby,1956) suggests that, as the environment's pace ofchange increases, a premium on developing knowledge emerges. Requisite variety means that organizational entities, such as supply chains, must matchthe environment's complexity with their own internal strategies and activities. A supply chain adeptat developing knowledge possesses a greater arsenal of wisdom for overcoming the complexitiescreated by rapid change than do other supplychains. Thus:

Hypothesis 4: Market turbulence has a positiveinfluence on the relationship between knowledgedevelopment and cycle time performance.

Structural contingency theory suggests that thevalue of a resource depends on the context withinwhich it is deployed (Lawrence and Lorsch, 1967).Building on this general tenet, we expect marketturbulence to suppress the culture of the competitiveness-performance relationship. As definedabove, CC reflects a supply chain's predispositionto spot and strategically plug gaps between what

Strat. Mgmt. /., 28: 1035-1052 (2007)DOI: 10.1002/smj

This content downloaded from 168.156.40.175 on Tue, 19 Nov 2013 11:07:50 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 TRATEGICSUPPLY CHAINMANAGEMENT: IMPROVINGPERFORMANCETHROUGHA CULTURE OF COMPETITIVENESSAND KNOWLEDGE DEVELOPMENT

7/19

1040 G. T. M. Huit, D. J. Ketchen Jr and M. Arrfeltthe market desires and what the chain currentlyoffers (Huit et al, 2002). Under low levels of tur

bulence, these gaps are relatively consistent andslow developing, suggesting that CC can be effectively targeted at filling the gaps. When turbulenceis high, however, the market's desires shift rapidlyand unpredictably, leading the gaps that CC seeksto fill to be fluid and nebulous.

Indeed, as Aldrich (1979: 69) stresses, a highlevel of turbulence 'leads to externally inducedchanges ... that are obscure to administrators anddifficult to plan for.' Weiss and Heide (1993) alsonote that rapid change in the marketplace canbe destructive and detrimental to already-existingcultural competencies (e.g., a culture of competitiveness) that are deeply ingrained and embeddedin the values and belief system of supply chainmembers. Thus, while greater market turbulenceincreases the supply chain's knowledge development requirements (Levinthal and March, 1981),greater turbulence in the marketplace also servesas a detriment to a culture of competitiveness. Assuch, we expect that:

Hypothesis 5: Market turbulence has a negativeinfluence on the relationship between a culture

of competitiveness and cycle time performance.

METHODData collectionPrior to collecting the data in 1999, we pretestedour scale items with eight academics and sevensupply chain management executives. Also, weperformed a pilot study with 36 supply management executives to assess the research design'squality. These steps resulted in some changesbeing made, mainly to the instructions to respondents and the need to keep the responses anonymous to secure study participation (i.e., we optednot to code the surveys for identification purposes based on concerns raised in the pretests andpilot study). Following Huber and Power's (1985)guidelines on how to get quality data from keyinformants, a survey was developed using Dillman's (1978) method and administered to supply chain management executives drawn from the

membership of the Institute of Supply Management (ISM). Founded in 1915, ISM is a not-forprofit professional organization of about 45,000Copyright ? 2007 JohnWiley & Sons, Ltd.

individuals who have responsibilities in supplychain management. ISM is best known for itsPurchasing Managers' Index (PMI)?a compositeindex of purchasing activity among manufacturingfirms that is closely monitored by financial institutions and economists.We restricted our sample tomanufacturing firms,and instructed respondents to focus on the lastorder fulfillment process within their supply chains.The sampling frame consisted of a total of 2000supply chain management professionals with 201responding for an effective response rate of 10.73percent (127 were non-deliverable). These individuals had been with their firms an averageof 11 years, and they represented firms that hadexisted for an average of 64 years, employedan

average of 13,688 people, and had an average of 38 people in their supply managementunit. The executives who responded had titlessuch as Director of Purchasing, Director of Purchasing and Materials Management, Vice President of Procurement, and Chief Purchasing Officer.

We used Armstrong and Overton's (1977)extrapolation procedure to assess non-responsebias. Table 1 summarizes the results. Although wefound a significant difference (p < 0.05) betweenthe first and fourth quartiles of the respondents forfirm age (with early respondents firms' averaging55 years and late respondents averaging 74 years),no systematic differences were found between theearly and late respondents. Thus, non-response biasis likely not an inhibitor in our analyses.

MeasuresTables 2 and 3 present the results of the measurement assessment. Table 2 summarizes the variables' means, standard deviations, correlations,and shared variances. Table 3 reports the averagevariances extracted, construct reliabilities, factorloadings, and fit indices. Established scales wereused tomeasure culture of competitiveness (learning, innovativeness, and entrepreneurial orientations), knowledge development (knowledge acquisition, information distribution, shared meaning,and achieved memory), market turbulence, andcycle time performance. Also, firm age and sizewere included as control variables (e.g., Amburgeyand Rao, 1996). Appendix 1 lists the scales usedand their sources.

Strat. Mgmt. J., 28: 1035-1052 (2007)DOI: 10.1002/smj

This content downloaded from 168.156.40.175 on Tue, 19 Nov 2013 11:07:50 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 TRATEGICSUPPLY CHAINMANAGEMENT: IMPROVINGPERFORMANCETHROUGHA CULTURE OF COMPETITIVENESSAND KNOWLEDGE DEVELOPMENT

8/19

Table 1. Comparison of early and late respondents

Respondents N Mean S.D.

Learning Early 50 5.67 1.19orientation Late 51 5.92 0.83Innovativeness Early 50 5.13 1.23

orientation Late 51 5.08 1.29Entrepreneurial Early 50 3.97 1.29orientation Late 51 4.36 1.31Knowledge Early 50 4.22 1.21acquisition Late 51 4.19 1.14Information Early 50 4.62 1.32distribution Late 51 4.75 1.32Shared Early 50 4.78 1.11meaning Late 51 4.78 1.33Achieved Early 50 5.31 1.12memory Late 51 5.51 0.87Market Early 50 4.95 1.21turbulence Late 51 4.82 1.17Cycle time Early 50 4.35 0.96Late 51 4.70 1.09Firm age* Early 50 55.24 42.06Late 50 74.29 45.39Firm size Early 50 15158.94 32458.88Late 50 15625.24 25446.49*p < 0.05.

All perceptual measures were subjected toassessments of dimensionality, reliability, andvalidity. The psychometric properties of the ninelatent constructs involving 44 items were evaluatedsimultaneously in one confirmatory factor analysis(CFA) using LISREL 8.80 (J?reskog et al., 2000).

Additionally, we examined the higher-order structure of CC and KD to provide empirical support, inaddition to the theoretical rationale, for the focuson these constructs at the higher-order aggregatelevel.

Fit of the measurement modelThe model fit was evaluated using a series ofindices recommended by Gerbing and Anderson(1992) andHu and Bentler (1999)?the DELTA2,relative noncentrality (RNI), comparative fit (CFI),Tucker-Lewis (TLI), and the root mean squareerror of approximation (RMSEA) indices. Afterremoving inadequate items (see Appendix 1), anexcellent fit to the data was achieved for the firstorder based CFA, with DELTA2, RNI, CFI, andCopyright ? 2007 JohnWiley & Sons, Ltd.

Strategie Supply Chain Management 1041TLI all being 0.96, and RMSEA = 0.07 (X2 =986.92, d.f. = 491).

Higher-order cultural competitiveness (CC) andknowledge development (KD) modelGiven the theoretical arguments underlying theCC and KD constructs in Figure 1, we next conducted a higher-order assessment of these constructs, including all purified items, the first-orderindicators, and the second-order indicators. Theresults indicate that, in addition to the item loadings reported in Table 3 for each of three CC andfour KD dimensions, there is support for eachconstruct's higher-order structure. As such, learning (loading = 0.64, ?-value = 8.26, p < 0.01),innovativeness (loading

=0.88, ?-value

=11.25,p < 0.01), and entrepreneurship (loading = 0.81,?-value = 8.91, /? < 0.01) function as first-orderindicators of the higher-order construct of CC (R2$

range from 40% to 78%), where the first-orderindicators are composed of the reflective indicators included inAppendix 1. Likewise, knowledgeacquisition (loading = 0.80, ?-value = 8.72, p CT isinsignificant, the results indicate thatMT serves asa pure moderator of the CC -? CT (negative) andthe KD -> CT (positive) relationships (Sharma,

Durand, and Gur-Arie, 1981). The inclusion of theinteraction and moderator terms (CC x KD, KD xMT, and CC x MT) in step 3 explained significantvariance beyond step 2 (AR2 = 0.04, p < 0.01).The fully specified model (i.e., including steps 1, 2,and 3) resulted in R2

= 0.34 (p < 0.01). Overall,all five hypotheses were supported in the hierarchical regression analysis.Parsimonious latent-variable interactionanalysisAs a second step in testing the hypotheses, we useda parsimonious latent-variable interaction technique via LISREL 8.80. This technique, developed by Ping (1995, 1998), is a more parsimonious estimation technique for latent interactionand quadratic variables than its predecessors byKenny and Judd (1984) and Hayduk (1987). Ouruse of this technique to examine the hypotheses adds to the hierarchical regression analysisin two ways. First, the latent-variable techniqueallows us to incorporate measurement errors forthe main and interaction effects (Ping, 1995, 1998)in order to assess whether such errors under

mine any statistical significant links within theresults (Busemeyer and Jones, 1983). Second, weare able to incorporate a test of potential CMVissues at the hypothesis-testing level to determinewhether CMV inflates or curtails the magnitudeof the obtained effects (e.g., Netermeyer et al,

1997; Podsakoff et al, 2003). Appendix 2 containsdetails on this analysis.The results of the parsimonious latent-variableinteraction analyses mirror those in the hierarchical regression analysis, with the exception that KDis not significant in either the unconstrained or theconstrained models (i.e., Hypothesis 2 is not supported). Consistent with the hierarchical regressionanalysis, we followed Ganzach's (1997) hierarchical procedure to SEM testing to estimate whetherCopyright ? 2007 JohnWiley & Sons, Ltd.

Strategie Supply Chain Management 1045the inclusion of main and interaction effects isempirically meaningful (the results for each of thethree steps are included in Table 4).In the full three-step and constrained model,the results indicate that CC (p < 0.01) and thehypothesized interaction term CC x KD (p