-

8/10/2019 The Upside Down Tree of the Bhagavadgt Ch. XV [v22n2_s3]

1/14

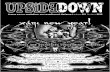

THE UPSIDE DOWN TREE OF THEBHAGAVADG T CH. XV

An Exegesis

BY

J. G. ARAPURA

McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada

rdhvamlam adhahsdkhamasvattham Prahur avyayamchandrhsi yasya par1J,niyas taik7,veda .sa vedavit

adhas co 'rdhvaiii prasrts tasya khf

gU1JaPravrddh visayapravctlcthaddaas ca mlny anusmhtatnikarmnubandhini manu?yaloke

na rpam asye'ha tatho 'palabhyaten 'nto na ca 'dir na ca sampratisth?aa.svattham enam svcvirudhamula?n

asangasastrena drdheyta chittvct.........The Bhagavadgit, XV.T-3.

Translation:

They say ]that there is [ an indestructible asvattha tree with rootsabove and branches below, whose leaves are the Vedic hymns : who

knows it is a knower of the Veda.Its branches spread below and above, being nourished by the guuas

(i.e., the strands that constitute Prakrti or Nature), objects of percep-tion being its twigs. Its [adventitious] roots are produced below, in

the world of man, bound to karma.

Its form is not obtained here as thus [or thus],. nor its end, nor its

beginning nor the ground [on which it is planted], once this asvattha

tree so well nourished [though it is], has been cut down with the mightysword of non-attachment.

-

8/10/2019 The Upside Down Tree of the Bhagavadgt Ch. XV [v22n2_s3]

2/14

132

The question is, athough the asvattlaa, described here is the "Cosmic

Tree", as all interpreters, both ancient and modern,agree,

in what senseis it that? Is it in the ordinary sense of the visible universe only or

perhaps in that scnse, no doubt, plus in the sense of something more

fundamental, that subtle human world which pervades the visible

universe,, tasted and felt in consciousness in the form of temperality,death, rebirth, etc., for which the word smhsra stands?

The symbol of the asvattha calls for an exegesis. Parallels with theCosmic Tree in other parts of the world known to us through the

history of religion can mislead one into thinking that the Gita is talk-

ing about the visible universe, its creation, implying the creator behindit, etc. The context of our exegetical effort here is some statements

by R. C. Zaehner, which reveal a profound misunderstanding. Prof.Zaehner seeks to counter-balance the Cosmic Tree with the belief inone God, Visnu-Krsna, which he sees to be the essence of the Gitu

teaching anyway! So he believes that here "the disciple is first askedto cut down the Tree of primordial creativity ( pravrtti) and then askedto take refuge in the very author of that Tree, 'from whom all thingsproceed ( pravartate)' ( io.8)" He also sees 'this as an important exampleof "mystical religion", as he adds, "this is, however, typical of mysticalreligion, and the Muslim mystic, for instance takes refuge in God's

mercy against his wrath. In Hinduism it is not the divine wrath thathides the eternal from the eyes of the worshipper but his 'divine mciyi'(7.rq.), his creative activity which conceals the timeless peace which is'his changeless [all] highest' mode of his being (7.24)". 1)

Etymology of the 'Word as?z?attlaa

In the Atharva-Veda there are references (5-4.3; 19.39.6) to theasvattha being the home of the gods and being in the third heavenlysphere, viz., the Varuna-loka.2) The Taittiriya Brahmana (3.8.12.2)says "the tree is called asvattha because Agni or Yajna-Prajpati fellfrom the sphere of the gods (i.e., the Deva-loka) during the pitr -(i.e., the path of the fathers), and taking the form of a horse (asva)

1) R. C. Zaehner, The Bhagavad-G t ,with a commentary based on originalsources, Oxford at the Clarendon Press, 1969, p. 362.

2) a vatthodevasadanas trit yasy miti tatr mrtasya caksanam dev hkusthamanvata (The a vatthatree is an abode of the gods ; it grows in the third heaven;this tree which confers immortality was acquired by the gods.)

-

8/10/2019 The Upside Down Tree of the Bhagavadgt Ch. XV [v22n2_s3]

3/14

133

remained invisible in it for a year. The same is repeated in the Anugitaof the illahdbhctrata (in Anu.sana Parva, 85). Several etymologistshave argued that a.svattha means horse-sable, because the horses of thesun took rest under it in the Yama-loka (the sphere of duringthe night of the pitrydna.

In the commentaries on the Gita - particularly in those of Sankaraand his followers - we find a radical philosophical etymology - asis usually the case when certain significant words are involved. San-kara's comment on Gitd XV.r, explains it as follows : na svo 'pi sthtiti asvatthau2, ksana pradhva?izsa?-a,swatthaz?2 - not abiding even till

tomorrow destroyed momcntarily - hence the word asvattha. 3)It is further described as smns,ra-nuly - the my of the cycle ofsmnsra.

Madhusclana Sarasvati in his exposition (vycikhyd) of Sankara'scomment carries it even further as he defines the word thus: suvin-satvena na 'pi stht iti visvasanarhan2 asz?attham - on account of

quick perishability and not deserving to be relied on, not abiding eventill tomorrow - hence the word asz.?attha. Srdhara makes this deriva-tion even more emphatic, as he has it: vinasvaratvevca sva prabhtapa-ryantarn api na stlaatayati iti visz?asazlarhatv?d asvatthavv? prdhu - theycall it a.svattha 'because it is unreliable on account of the fact that it willnot abide even till tomorrow morning.

Now it would appear on the surface, that the etymology of Sankaraand his followers is far-fetched, but when we remember that there areso many 'links between iva (t01nOrrO'lu), aizia (horse) and su (quick,fast and also - in the 6gveda - horse ) it ceases to look fanciful. Itwill be recalled that 'the horses of the Sun' (Chronos) stands for time

in Greek mythology also, and hence the association of the horse - andthe sun - with speed and time will become irrepudiable. The horsesof the sun resting during the night of the soul's progress in the path ofthe fathers (pitrydna) eventually becomes identified with the god oftime (Kala), who emerges finally as the mythological god of death. Weare at his point inevitably brought to the Katha Upanisad where the

imagery of the upside down tree occurs - evidently earlier than in theGita - the revealing god here being Yania, the official deity who pre-

3) All quotations from Sankara's C t commentary and the sub-commentariesof Anandagiri, Madhus danaSarasvati and r dharaare taken from the combinedtext edited by W. Laxman Shastri Pansikar, Bombay, Pandurang J waji, 1936.

-

8/10/2019 The Upside Down Tree of the Bhagavadgt Ch. XV [v22n2_s3]

4/14

134

sides over death. When we bear all these associations in mind, the objec-'tions of recent writers including B. G. Tilak (Gitdrahasya, Englishtranslation, p. 1136) that ?ankara's etymology is far-fetched will cease

to be valid, ?ankara would seem not to be speaking from mere imagina-tion as even Tilak suggests.

Asz?attha is no doubt tree bu't the word vrksa (tree) as such is used

only once in the CUd (X.26) - asvatthah sarvavrks?znam (of all trees

[I am] aSvattha) in the same way in which (Krsna speaking of him-

self) "of Rsis, I am Narada, of Gandharvas I am Citraratha, of Munis,

Kapi,la, meaning either the primordial, the original or in some ways the

most puzzling and mysterious member of each class of significantbeings. In the Upanisads the word appears several times, e.g., Kausitalai,I. 3 and 5. Chndogya, 6.9.1 ; 6.11.1; Brhadra1!yaka 3.9. 27 and 28;

Taittiriya, 1.10. I; S'lJetsvatara, 3.9; 4.6 and 7; 6.6. In fact strangely,.it does not occur in the Katha Upa?isad, in which the parallel passagesto the Git4 text is found.

,

The word vrksa (tree) has also been subjected to etymological treat-

ment by ?ankara in his Katha Tl?,anisad Bh-fya, a propos the tex't in

theUpa?isad II.3. 1,4)

which has the notablesimilarity

with the first

Gita passage about aSvattha (XV. I). Sankara writes: vrksasca vraicant

(the word vrksa [is used] owing to cutting down.). This etymologyis given in the context of expounding sari2sdra-vrksa (smhsra-tree).

Gopala Yatindra in his Tika (sub-commentary) expands Sankara's

etymology even further: .sayvcsara eva vrksah savvc.sd??avrk.sah vrk.sa-

,vabda-pravrtti-nintittan,t aha vraicant iti. 5) (The tree [is] that which

is indeed samsra, that is the samsra-tree; the word vrksa is spokenbecause of instrumentality of becoming [that is] due to its being cut

down). Despite this kind of etymological elaboration, it is well to bearin mind that actually in the Upanisad text in question neither the word

savi'csara nor the term smhsra-vrk-fa nor the notion of cutting down

appears. On the contrary the tree here is apparently Brahman. In the

4) rdhva-m lo'v k- khaeso ' atthas san tana ,tad eva ukramtad braham,tad ev mrtamucyate. tasmin lok rita sarve tad u n tyetika cana.etat vai tat.With roots above and branches below (stands) this timeless a vattha; that aloneis the pure ; that is Brahman ; that alone is said to be immortal. In it all the worlds

rest, andno one ever

goes beyondit. This indeed is that.

5) Ka hopanisad) with ankara's commentary and its T kas, ( nand ramasamkrta grandh val No. 7.), Poona, 1965, p. 109. This etymology is from theNirukta of Yaska, 2.6.

-

8/10/2019 The Upside Down Tree of the Bhagavadgt Ch. XV [v22n2_s3]

5/14

-

8/10/2019 The Upside Down Tree of the Bhagavadgt Ch. XV [v22n2_s3]

6/14

136

as it were by accident while they ought to have been identical? Or,rather, is it possibly the case that these differences in the texts

represent two aspects of the same truth concerning safimsfra ? Radha-krishnan observes: "The tree of life has its unseen roots in Brahma.The tree, roots and branches represent Brahman in its manifestedform. While the tree of life is said to be imperishable Brahman, the

Bhagavadgitct, which uses this illustration, asks us to cut of the treeof existence by the potent weapon of non-attachment." s) The treeof Brahman represented in the one, not depicted as cleavable, is pic-tured in the other as the tree of existence eminently deserving to be

cut down.. ?ankara in fact seems to assume that, far from being inter.tionallyopposed or accidentally different, the texts are co-ordinated in thesame ultimate ontology. Hcnce while interpreting the Gita passage, hemoves toward the Ka!ha passage with this observation: "[It is called] ]rdhvamlam (with roots above) because of subtlety with respect to

time, because of causality, because of eternality and because of malaat-h.ood. Hence the unmanifest Brahman is said to possess the powerof ??2ayd. That (i.e., the unmanifest Brahman) is its (i.e., the tree's)root. Hence this sam sara-tree has its roots above." 9)

?ankara quotes a "Purana" text, which is in fact a text (47: 12-14)of the Asvamedha parva of the Mahbhiirata 10) being part of the

8) Radhakrishnan, S. (ed.) The Principal Upanisads, London, George Allen &Unwin, Ltd. 1953, p. 642.

9) rdhvamulam k lata s ksmatv t-k ranatv t-nityatv t-mahatv tca- rdhvam,ucyate brahma avyaktam m y - aktimat,tanm lasyaiti so 'yam samis ravrksa

rdhvam la .

10) avyakta-b ja-prabhavo buddhi-skandha-mayo mah nmah hamk ra-vitapaindry ntara-kotara.mah bh tavs kha cavi esaprati- khavansad -parna sad -puspah ubh ubha-phalodayahaj va sarvabh t n mbrahmavrksa san tana etat-chittv ca bhittv ca j nana param sin .hittv c marat mpr pya jahy dyau mrtyujanman mirmamo nirahamkaro mucyate n trasam ayah.From the Mah bh rata,A vamedhikaparvan, (critical edition) Poona, 1960.

Trans. :The great tree of Brahman is timeless, having risen out of the seed of the

Unmanifest, with buddhi (intelligence) for its trunk, the great ego for itsbranches, the senses for its sprouts, the great elements for its sub-branches, thesense-objects for its side-branches; ever covered with foliage and ever bearing

-

8/10/2019 The Upside Down Tree of the Bhagavadgt Ch. XV [v22n2_s3]

7/14

137

Anugit?z. The discrepancies between the ?ankara quotation and the

original are purely verbal, and inconsequential. The main reason for

quoting the ll2ahccbharata text is to show that the reality representedby the tree is the lower (saprapaiica) Brahman, and that even so Brali-man is the ground or the real being of the tree and, vice-versa, thetree is the resort of Brahman. Anandagiri observes in this context thatthe tree is grounded in Brahman, and also Brahman dwells in the treeand that because the tree cannot be cut without that knowledge it is

called timeless and enduring. 11 )Now there is the mention of a tree in the Svettisvatara tl"tanisad.,

111-7-9. The question is, is there any connection between the asvattlza(the saJnsra-tree) or the tree of Brahman and the tree in this partic-ular Upanisad passage? The two seem wholly unrelated to each other

except for the fact that the word 'tree' occurs in the latter too. YetZaehner thinks that in both the same concept of the tree exists, per-

forming the same function. He further assumes that the theistic inter-

pretation of the cosmos, which he obviously sees as implicit in the

Gita, the Kailha and the Anugit(7 texts has been made explicit in the

Svetsvatara text; apropos the last of which he observes "it is Go

-

8/10/2019 The Upside Down Tree of the Bhagavadgt Ch. XV [v22n2_s3]

8/14

-

8/10/2019 The Upside Down Tree of the Bhagavadgt Ch. XV [v22n2_s3]

9/14

139

we have an ontology not by virtue of any pressure that being puts uponbecoming - there is no such pressure and indeed apart from becomingtaken problematically there would be no need for the concept of beingat all. There is, on the contrary, a pressure that comes from within the

realm of smnsra, of becoming, and that is an existential pressurecalling for an answer. Hence Brahman is to be understood as the

ground of the tree of saiz2sara, and the tree inevitably grows down-ward. That tree is the a.svattl?,a of the Bhagavadgt. This has been

pointed out by the present author in his book Religion as Anxiety and

Tranquillity. 15) The symbol of the a,.,(vattlw then would seem to be a

characteristic way of articulating ontology as an answer to the questionthat sG1nsra poses. Hence it is not to be construed as something"typical of mystical religion" as is done by Professor Zaehner.

It is in view of this ontology that the a.vattha is called both saznsara-

tree and the tree of Braham; and the two apparently different signifi-cances attached to the tree in the Git4 and the Katha are not really con-

trary to each other. Because of this ontology the concept of God enters

into it naturally, not in any partisan manner, however, to be construed as

an expression of theism, so to say as against Advaita, as ProfessorZaehner seems to see it. The concept of God is always natural and

ontologically necessary for the Advaita. Brahman the ground or the

root of the sG1nsra-tree is in that relation to be necessarily referred

to as God. Hence there is no contradiction between Madhusudana

saying smnsra-vrk:msya hi mlam brahma (Braman is the groundof the sathscira-tree) and ?ridhara saying sG1nsra-vrktJasya 111lam-

isvarah sri raardyanah lgvara, Sri Narayana is the ground of the

savbcsara-tree). 16) Again, God mediates betwecn two eternities, onethat belongs intrinsically with Brahman and another that belongs with

becoming: hence the distinction between the svarpanityat (of Brah-

15) "The true foundations of Indian religious perspectives are the tranquillitystructures mediated through the teaching (dharma in Buddhism and differentdar anasin Hinduism) ; and the structures of suffering are placed as appendix tothem, to be always seen from the tranquillity end like the upside down tree of theBhagavadg t with its roots above and branches below." Religion as Anxiety and

Tranquillity: An Essay in Comparative Phenomenology of the Spirit, The Hagueand Paris, Mouton, 1972, p. 80.16) In their respective sub-commentaries on the G t ,in the context of the

a vatthatext.

-

8/10/2019 The Upside Down Tree of the Bhagavadgt Ch. XV [v22n2_s3]

10/14

140

man) and the pravhanityat (of the cosmos). In terms of the formerthe asvczttha is perishable; in terms of the latter it is unending, ever-

enduring.l7) _

The Philosophical significance based on survey of further texts

In order to understand the context in which the symbol of the treeas sathscira it will be well to go back to the Vedic texts. By doing sowe will be able to perceive more clearly than otherwise two importantphilosophical truths contained in the asvattha symbol, as we will learnof its very early gcnesis also:

I. The upside-down tree is no new innovation, its inverted positionhaving been there from the genesis of the concept in the Vedas as

representing, no doubt, clear anticipations of an ontology of the cosmos

(rather than cosmology), re-appearing in the Citd, the Katha and theIl?lahabharata (the Anugt), expressing essentially what has been vastlymore elaborately set forth in the Vedanta philosophy in subsequenttimes.

2. The ontology of the cosmos is something which goes hand in hand

with a particular kind of self-knowledge, a wisdom by means of whichas a sword is alone one able to deal with the world: knowledge isalso detachment - hence asazaga.sastrev?a drdhena (the Gita) or iiiclileilaparamsin (the AnugU).

Let us consider these two philosophical points as presented in theVedic literature.

I. In the Rgveda 1.24.7, we have a very striking mantra: It is the

oldest one referring to the tree. Rsi Sunahsepa, while describingVaruna's greatness speaks of a tree that the latter planted in the bottom-less with its roots above and branches below:

abudhne rj varuno vanasyordhvam stupam dadate ;?utadak?s?ahnicinjh sthur upari budhnaasyne antar nihitah k?etavah syuh

17) Madhus danawrites, sa ca sams ravrksah svar pena vina varahprav ha-r pena ca ananta ; and Sridhara likewise writes, sa ca sams ra-vrkso vina vara prav har penanitya ca,loc. cit. in both cases

-

8/10/2019 The Upside Down Tree of the Bhagavadgt Ch. XV [v22n2_s3]

11/14

41

(King Vauna placed the orb of a tree in the bottomless in a down-

ward position, with his holy power. Of these the roots remained above.

They are the clues (ketavc?h) concealed inside us.)

The domain of Indra is described as transcendent, not accessible even

to the high-soaring birds (metaphorically standing for the flight of

the intellect). But the clues are inside us. The poem goes on to

describe how Varuna made the path for the sun to traverse.This symbol of the tree is also evidently linked with the Rgveda

X.72.3, a poem connected with B rhaspati, where the famous image of

Uttnapada (what has feet upward) occurs; it goes as follows:

dev,anam yuge prathame

'satah sad ajayatatad anv ajdyatatad ittttinapatias pari

(In the first epoch of the gods the existent arose from the non-

existent. Afterwards arose the directions, whereafter [there grew]around [it] what has feet upwards.)

These two are the most express references to the tree (or the cos-

mos) with roots above (or feet upwards) and the body (or boughs)downwards. There are several other less express ones, which must beomitted from this investigation.

We meet with the upside down tree in the Chandogya Upanisad( VI.12. i ) in the form of the nyagrodJw. 18) The word myagrodha is

made of two parts nyag (downward) and rodlaa (growing). (Markan-daya Risi also is said to have secn l?vara sitting on the branches of

the awyaya tree (vatavrksa or nyagrodha) at the time of the greatDeluge). The great tree (l1whn nyagrodha) - called so because it is

the cosmos itself -, it is declared in the next verse, had ariscn out ofthat extremely minute entity residing imperceptibly within the fruit

18) The object of inquiry is the fruit of the tree rather the tree itself.nyagrodha-phalam ata haret; idam bhagava ,iti ;bhinddh ti ;bhinnam bhagava ;kim atra pa yasiiti ;anvaya ivema dh n hbhagavah iti; s mangaikam bhinddhanti ; binna, bhagavah, iti ;kim atra pa yati; na kim cana bhagavah, iti.

(Bring hither a nyagrodha fruit; this my Lord. Break it. It is broken, my Lord.What do you see here? Extremely small seeds, my Lord. Break one of those. It isbroken, my Lord. What do you see here? Nothing at all, my Lord.)

-

8/10/2019 The Upside Down Tree of the Bhagavadgt Ch. XV [v22n2_s3]

12/14

142

and the seed - (etant anivv?anazv na nibhiilayase .. eso etc.).2. Now the relation between the ontology of the cosmos and knowl-

edge must be considered. Knowledge here is definitely an inward-

turning knowledge, (which is the essential meaning of iiicina), awisdom by means of which one achieves an existential disconnexionfrom the things which bind one to savvcsara.

In the context of the tree planted by Varuna, described in the

Sunahsepa hymn, the question is, what is above, namely the bottom-

less, where the roots are placed? We learn that it is light. 19) The rootof the tree is in the region of light. Bust for gaining light man must

seek clues within: the seeing of light is wisdom. Man comes to lightby means of the inward quest, that is to say, the searching of con-

sciousness.The theme of searching within for knowledge - and freedom -

come fully to light in the Upanisads (and re-stated in the Gita-, no

doubt.) It was echoed faithfully by Sankara. 20) Cutting down the

tree of the cosmos is not refusing to see it, but rather seeing it in the

Self: he who sees so truly sees. 21)The tree of the Cosmos is not only mysterious but also fearful -

not an object of comfort but of dread. And knowledge of the tree must

comprehend the dread too; dread is an element of human and cosmic

19) The hymn of Suna epawas sung by him, we learn from the AitareyaBr hmana.(the Rgveda does not recount the story) where he, the young boy thathe was, was bound to the stakes to be sacrificed to Varuna; by this hymn he praysto Varuna for freedom and light (wisdom), and he found the answer: searchwithin.

20) tm tu satatam pr pto 'pr pyavadavidyay tann epr ptavad-bh tisvakanth bharanam yath

(The Self which is ever present, yet due to ignorance it remains unrealized,as a man looks for his ornaments which he is wearing on his neck). tmabodhaof ankara, stanza 44. (See tmabodha-Self-knowledge, Swami Nikhilananda,Madras, Sri Ramakrishna Mutt, 1962, p. 207).

21) samyagvijan v nyogi sv tmayev khilam jagatekam ca sarvam tm nam- ksate j na-caksus

(The yogi endowed with complete wisdom sees the entire universe in his ownself; through the eye of knowledge he sees everything as one), tmabodha, Stanza47. (See Ibid., p. 210).

tmaivedam jagatsarvam tmano 'nyanna vidyatemrdo yadvad-ghat d nisv tm namsarvam iksate

(He knows the entire universe to belong to the Self, and to be nothing other;he sees everything to be of the Self just like things like pottery to be clay.)

tmabodha, Stanza 48, (see ibid., p. 211).

-

8/10/2019 The Upside Down Tree of the Bhagavadgt Ch. XV [v22n2_s3]

13/14

143

consciousness which must be brought to the open through knowledge.The Katha Upanisad verses (II.3.2-3) following the one concerningthe asvattha speaks about it. In describing this there occurs the meta-

phor of the great fear, the upraised thunderbolt (mahad bhayaiii7,airam udyatavvc) for the way the cosmos and its forces impress man.

They who know it become immortal (ya etad vidur amrtcts te bhavanti),says the Katha text.

Professor Zaehner does not omit to note the Kallha theme of fearin his exposition of the Gita text under consideration, as he observes:*It may paralyze through fear, yet it is none the less the ladder by

which and through which the immortal can be found." 22) But surely,the fear here described is not an individual fear, but one of a cosmic

nature, governing the very principle by which the forces of the universeare sustained. This the h'atha verses in question make abundantly clear.

Agni, Indra, Vayu, Death (the physical forces as well as the deities)do their work through fear of Him (Atman, Brahman). Sankaraclarifies that the universe itself trembles in Brahman (parasminbrahmaii,i saty ejati kmnpate).

Yet the knowledge which comprehends the dread that moves theentire cosmos and all the forces in it - thus generating a genuineself-knowledge pertaining to man's situation in the universe of be-

coming - also liberates him from that dread. The dread is therein the first place as a vague, unclarified individual experience -

an unexplored sense of the wrongness of existence, 23) which afflicts

man, but its true ontological genesis and depth, its cosmic character,must be explored by means of knowledge. This constitutes part ofthe essential theological knowledge that Vedanta not only permitsbut warrants. To know the depth and the universality of dread,the point at which it touches the divine is an indispcnsable act of

religious knowledge. 24) It must be complemented by another act of

religious knowledge, that of taking refuge in God. Hence the Git4a

enjoins:

22) op cit., p. 362.23) This theme is elaborated phenomenologically in the author's book, Religion

as Anxiety and Tranquillity.

24)na

r pam asye'ha tatho

'palabhyaten 'nto na c dirna ca smpratisth (Its form is not perceived here, nor its end, nor its beginning, nor its founda-

tion) The Bhagavadg t XV. 3. a, b.

-

8/10/2019 The Upside Down Tree of the Bhagavadgt Ch. XV [v22n2_s3]

14/14

144

tatah padam na pariindrgitavyamyasmin gat na nivartanti bluyahtarn eva ca 'dyam purn:ravr2 prapadyeyatah pravrttih prasrti purani 25)

(Therefore, that path must be followed, from whence those whohave walked it never return. And in Him, that Primal Person, I take

refuge, from whom has flowed this ancient current [of the cosmos].

Knowledge is both the comprehension of Dread and the flight for

Refuge, - fully these, and yet more. The thrust of knowledge accord-

ing to the Upanisads and the Gitd is not exhausted by these, however.The experience of the dread and the taking of refuge are two co-

ordinate steps, both being of the character of knowledgeand focussed on the Divine. In both respects Sunhsepa is the trueVedic prototype. And strangely, perhaps not so strangely, but ratheras we should expect, the substance of this knowledge is built into theconstitution of the cosmos, as the Vedas are its leaves - and the Vedashave meant shelter, refuge. And here we recall the Cha?Ldogya Upanisad1.4,s, where we read that "the gods fearing death took refuge in thethree-fold knowledge (trayim vidyan2), i.e., the three Vedas. TheVedas were their cover, hence they are known by the word chandas.

Knowledge has a paradoxical location in the cosmos. It is not alien,and yet it is alien, particularly insofar as it is the sword uTith whichto cut it down. But the quest for understanding it must lead one

inevitably to the complex doctrine of the Word - the world itselfcomes from the Word, which is another side of the matter. 2G)

Lastly, the purpose of doing this particular piece of exegesis has

been to show that the real siginificance of the a,vattha symbol issomething other than what is described by Professor Zaehner as

"typical of mystical religion" and is not something into which an ulti-mate and terminal devotional theism can be read.

Professor Zaehner is right in calling attention to the theistic

emphasis, but it is also necessary to make sure that that legitimateemphasis must not lend support to the view that the theism here isof a terminal or ultimate kind. The exegetical placing of the a,?7.7atthais

onlyone

exampleof how the Gita theism must be seen.

25) Ibid., XV. 4.26) Vedanta-s tras 1.3.2.8. But it is Brahman, not the Word, which is the

material cause of the world.