Previous research on whistle-blowers has tended to focus on the individual as the unit of analysis rather than on the organization or its subunits. Subunit level analysis of survey data from 15 subunits of the U.S. government was used to examine the relationship between members' values concerning wrongdoing and whistle-blowing and the organization's prac- tices. We conclude that "positive " organizational climates may discourage serious wrong- doing and encourage whistle-blowing under some conditions, but the relationship is not as straightforward as might be expected. THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN VALUES AND PRACTICE Organizational Climates for Wrongdoing JANET P. NEAR Indiana University MELISSA S. BAUCUS |'' • University of Kentucky A MARCIA P. MICELI Ohio State University In recent years, scholarly literature has been developing concerning whistle-blowing, defined as "the disclosure by organization members (former or current) of illegal, immoral or illegitimate practices under the control of their employers, to persons or organizations that may be able to effect action" (Near & Miceli, 1985, p. 4). However, most of this research has been conducted at the individual level, focusing on questions of who blows the whistle and who suffers retaliation. For example, we now know some of the factors that are most likely to cause individual employees to decide to blow the whistle (Miceli & Near, 1984, 1985, 1992). Of these, some are individual characteristics, such as beliefs about whistle-blowing, and others are contextual factors related to characteris- tics of the wrongdoing observed, for example, whether it is serious or ADMINISTRATION & SOCIETY, Vol. 25 No. 2, August 1993 204-226 © 1993 Sage Publications, Inc. 204

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

Previous research on whistle-blowers has tended to focus on the individual as the unit ofanalysis rather than on the organization or its subunits. Subunit level analysis of survey datafrom 15 subunits of the U.S. government was used to examine the relationship betweenmembers' values concerning wrongdoing and whistle-blowing and the organization's prac-tices. We conclude that "positive " organizational climates may discourage serious wrong-doing and encourage whistle-blowing under some conditions, but the relationship is not asstraightforward as might be expected.

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEENVALUES AND PRACTICEOrganizational Climates for Wrongdoing

JANET P. NEARIndiana University

MELISSA S. BAUCUS |'' •University of Kentucky A

MARCIA P. MICELIOhio State University

In recent years, scholarly literature has been developing concerningwhistle-blowing, defined as "the disclosure by organization members(former or current) of illegal, immoral or illegitimate practices under thecontrol of their employers, to persons or organizations that may be ableto effect action" (Near & Miceli, 1985, p. 4). However, most of thisresearch has been conducted at the individual level, focusing on questionsof who blows the whistle and who suffers retaliation. For example, wenow know some of the factors that are most likely to cause individualemployees to decide to blow the whistle (Miceli & Near, 1984, 1985,1992). Of these, some are individual characteristics, such as beliefs aboutwhistle-blowing, and others are contextual factors related to characteris-tics of the wrongdoing observed, for example, whether it is serious or

ADMINISTRATION & SOCIETY, Vol. 25 No. 2, August 1993 204-226© 1993 Sage Publications, Inc.

204

Near et al. / VALUES AND PRACTICE 205

especially harmful. Researchers have also investigated whether whistle-blowers are more likely to use internal or external channels for blowingthe whistle (Miceli & Near, 1985) or to do so anonymously (Miceli,Roach, & Near, 1988). Finally, characteristics of the whistle-blower andthe situation that increase the likelihood that managers in the organizationwill retaliate against the whistle-blower have been studied (Miceli & Near,1988; Near & Miceli, 1986; Parmerlee, Near, & Jensen, 1982).

These individual level analyses have contributed to our understandingof who blows the whistle and who suffers retaliation; however, littleattention has been paid to the effect that the organization or subsystem hason the whistle-blowing process. In particular, subsystems in organizationsare recognized to have separate climates (Powell & Butterfield, 1978) orcultures (Riley, 1983) that affect the values, beliefs, and practices ofsubsystem members. As Joyce and Slocum (1982) note, "Psychologicalclimate refers to individual descriptions of organizational practices andprocedures" (p. 951), whereas "organizational climate refers to a collec-tive description of this environment, most often assessed through theaverage perceptions of organization members" (pp. 951-952). Subsystemsare assumed to also have general ,response patterns that they commonlyuse in dealing with wrongdoers and whistle-blowers. Our study examinesthese general patterns, relying on rajes or frequencies of wrongdoing andwhistle-blowing as characteristics of the subsystem, with the goal ofcreating a picture of the overall climate related to wrongdoing andwhistle-blowing.

VALUES AND PRACTICES

Organizational systems may be described in terms of the values of theirmembers and their practices, among other things (Hofstede, Neuijen,Ohayv, & Sanders, 1990). In some cases, however, the espoused valuesdiffer (Hofstede et al., 1990) from the actual values shown in the practicesof the system, sometimes termed the values in use (Posner, Kouzes, &Schmidt, 1985). This is not a minor distinction; in fact, Enz and Schwenk(1989) found that subunit performance was positively associated with thevalues in use or practices, but negatively associated with the espousedvalues of the subunits. Hofstede etal. (1990) found that individuals' valueswere more strongly related to cultural values (i.e., national values) thanto organizational values, but that practices were viewed more similarly byindividual members of the organization. Further, organization and subunit

206 ADMINISTRATION & SOCIETY / August 1993

mean scores on practice differed more substantially than did averagescores on values, suggesting that practices are more unique to organiza-tions, whereas values seem to reflect societal norms (Hofstede et al.,1990). Thus results of previous research indicate that we need to examineboth the values and practices within subsystems of an organization,recognizing that practices may differ widely among subsystems.

Rather than investigate values and practices in general, we were interestedin values and practices related to the whistle-blowing process. This isconsistent with Schneider and Reichers' (1983) argument that organizationalclimates are multidimensional and thus they must be studied in reference tosomething, such as a climate for whistle-blowing (Zalkind, 1987). Wilkinsand Dyer (1988) refer to this as a specific frame rather than a general frame.Comparisons of climate across organizations or subunits of organizations canthen be made, for a specified set of values and practices.

The present study is an attempt, therefore, to identify measures oforganizational values that pertain to whistle-blowing. Another purpose isto examine these measures of values to determine their relationship tomeasures of actual practices, reflecting the occurrence and nature ofwrongdoing, whistle-blowing, and retaliation.

ORGANIZATIONAL CLIMATES FOR WRONGDOING

To understand the relationship between organizational climate andorganizational wrongdoing, it is necessary to consider the possible waysthe organization can respond to both whistle-blowers and wrongdoers.Specifically, there is a tendency to view whistle-blowers either as dissi-dents or reformers (Near & Miceli, 1987).

'

WHISTLE-BLOWERS AS DISSIDENTS

The perspective that regards whistle-blowers as dissidents emphasizesthe importance of maintaining stability and order in organizations (e.g.,Weinstein, 1979). Bureaucratic organizations are recognized as havingformalized rules and procedures. These rules and procedures may pro-scribe wrongdoing but simultaneously define whistle-blowing as illegiti-mate (Farrell & Petersen, 1982); this may occur because whistle-blowingthreatens the hierarchical principles (Stone, 1975) or the authority struc-ture of the organization (Weinstein, 1979), or because such an organiza-tion is simply more likely to resist change (Kanter, 1983). Thus many

Near et al. / VALUES AND PRACTICE 207

organizations "have a natural self-sealing mechanism that quashes at-tempts to question organizational policy" (Stanley, 1981, p. 16).

As a result, instrumentally rational bureaucracies (Weber, 1925/1947)could be expected to punish both wrongdoers and whistle-blowers, be-cause they have broken the rules or violated procedures. If so, lower levelsof both whistle-blowing (as a proportion of responses to wrongdoing) andwrongdoing would occur, thereby resulting in a belief system amongmembers that both wrongdoing and reporting of wrongdoing are discour-aged by the organization. Thus, due to the (actual or perceived) closedcommunication channels, whistle-blowing is likely to be less frequentthan in other systems (holding the level of wrongdoing constant).

In general, research examining punitive climates and their consequencesis limited, and it has produced conflicting results. A study of retail stores(Cherrington & Cherrington, 1981) revealed that the organization with thehighest level of wrongdoing also had a negative culture (defined as highlydissatisfied employees and frequent checking of employees) and openlypunished wrongdoers as a deterrent to others. Paradoxically, this suggests thatpunishing wrongdoers may alienate workers (Taylor & Cangemi, 1979;Zalkind, 1987) and further encourage wrongdoing and the development of anegative organizational climate. In contrast, Keenan concluded that "a highsupportive and low defensive organisation climate is a major factor influenc-ing the decision of first-level managers to blow the whistle or not" (Keenan,1988, p. 250). Finally, Graham (1984) found no relationship between organ-izational climate and the response taken by the organization to whistle-blowers.

Although case studies of whistle-blowers (Nader, Petkas, & Blackwell,1972) supported the idea that retaliation deters whistle-blowing, comparativefield research found no relationship between retaliation and deterrence(Near & Jensen, 1983; Near & Miceli, 1986):Similarly, a controlled fieldexperiment showed that threatened retaliation did not discourage observ-ers of wrongdoing from reporting it through internal channels (Miceli,Dozier, & Near, 1991). In contrast, threatened retaliation was found to beassociated with a greater propensity to blow the whistle to parties externalto the organization rather than internal agents (Miceli & Near, 1985). Suchfindings suggest that an alternative view of the relationships betweenorganizational climates and whistle-blowing is needed.

WHISTLE-BLOWERS AS REFORMERS

In contrast to the view of whistle-blowers as dissidents, they may beseen as reformers who provide the organization with information that is

208 ADMINISTRATION & SOCIETY / August 1993

important for improving the organization's effectiveness (Ewing, 1983; Near &Miceli, 1985). Individuals who express dissenting views are needed toprevent the organization from making decisions and forming rigid plans thatlead to failure (Stanley, 1981). Thus whistle-blowers help to "promote theefficiency, productivity, and increased quality of performance" of organiza-tion members (Burnett, 1980, p. 5) by bringing problems and potentialsolutions to management's attention. Viewing whistle-blowers in this lightsuggests that more positive climates would encourage whistle-blowing.

The number of whistle-blowing instances is confounded, however,with the incidence of wrongdoing. Some wrongdoing must occur beforewhistle-blowing can result—otherwise, potential whistle-blowers couldnot act. The most positive climate would be characterized by low rates ofwrongdoing, but where potential whistle-blowers could feel free to actshould the need arise. Even climates where the rate of wrongdoing wassomewhat higher could be viewed as positive, if whistle-blowing wassupported and encouraged and the wrongdoing was consequently corrected.It may also be true that positive climates produce a heightened awareness ofwrongdoing. However, generally speaking, lower levels of wrongdoingwould be more desirable than higher levels, for obvious reasons.

We believe that the most positive organizational climate is one (a)where the rate of wrongdoing is low and (b) where wrongdoing that doesoccur is usually not serious. Nonetheless, wrongdoing that does occur inthese systems (c) is reported internally, (d) without reprisal toward thewhistle-blower. Together, these four dimensions constitute our definitionof a positive climate for whistle-blowing. Climates that differ on one ofthese four dimensions would be less positive, the most negative of theseclimates where incidence and seriousness of wrongdoing was high, inci-dence of whistle-blowing was low, external channels were used, and theincidence of retaliation was high. As a result, this study focuses on therelationship between a positive climate for whistle-blowing in an organi-zation (as reflected in the values of its members) and possible conse-quences for the system's practices, that is, the incidence and seriousnessof wrongdoing, the incidence of whistle-blowing, and the incidence ofretaliation against whistle-blowers.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

Our research questions reflect our prediction that the organization'svalues will be positively related to its practices. Specifically, we assume

Near etal./VALUES AND PRACTICE 209

that positive values about whistle-blowing will produce organizationalpractices that are also positive, based on our definition of positive cli-mates. Positive values would endorse the avoidance of organizationalwrongdoing, particularly serious wrongdoing, the reporting of any wrong-doing that occurs, and the discouragement of retaliation against whistle-blowers. We expect that such values, expressed by organization members,should be associated with positive organizational practices—that is, a lowincidence of wrongdoing, less serious wrongdoing, a high incidence ofwhistle-blowing as a proportion of all responses to wrongdoing, and a lowincidence of retaliation, controlling for the effects of incidence of whistle-blowing. This prediction is consistent with results produced by Hofstedeet al. (1990) that "shows values and practices to be distinct but partlyinterrelated characteristics of culture" (p. 305).

METHOD

In 1980, the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board (USMSPB) mailedconfidential questionnaires to the homes of a random sample of employ-ees in each of 15 major U.S. government departments and agencies. Astheir report notes, this sample was "aihirror image of the total populationin each agency" (USMSPB, 1981, p. ii). Of the approximately 13,000employees selected, 8,587 returned usable anonymous questionnaires fora response rate of 66%. In addition, over 2,500 of these individualsprovided written comments that elaborated on and helped to validate theirquestionnaire responses (USMSPB, 1981). Our findings are based onsecondary analyses of these data. The 15 departments and agencies, whichvaried in size from fewer than 1,000 to over 200,000 employees, weretreated as separate subsystems of the federal government. That is, allquestionnaire responses were aggregated by subsystem; our analysesrepresent relationships among subsystem scores. Although individuallevel analyses of these data have been reported (Graham, 1983, 1984;Miceli & Near, 1984,1985,1989; Near & Miceli, 1986), we have seen noaggregated analyses of these data.

The use of subsystem scores represents a philosophical difference inthis study as compared to earlier research. Some of the previous studieshave focused on individual differences in belief systems in an effort topredict whether an observer of wrongdoing decided to blow the whistle.In contrast, in this study we have focused on differences in the sharedvalues of organization members and on the question of whether these

210 ADMINISTRATION & SOCIETY/August 1993

shared values predict the subsystem's practices. Practices in which wewere interested included the incidence of wrongdoing, whistle-blowingand retaliation in the agency, and the average level of seriousness of theincidents of wrongdoing occurring in the agency. Because all the measureswere aggregate subsystem scores and some were taken from differentsubsamples of the organization's respondents, the possibility of methodcovariance is drastically reduced (see Hofstede et al., 1990, for a detaileddiscussion of the appropriateness of ecological analyses).

Although the subsystems themselves varied greatly in size, we felt thatthis was the appropriate level of analysis for an important structuralreason. Each of these subsystems includes a separate office of the inspec-tor general (OIG), a structure determined by the original legislation thatcreated the MSPB. Although each of the OIGs must follow some standardprocedures, it is clear from archival materials collected earlier from theseagencies that they vary dramatically in their approach to pursuing wrong-doers and protecting whistle-blowers. Because each agency has only oneOIG, its influence is presumably felt across the agency, even when theagency is large.

MEASURES

Measures of Values

Seven items, each rated on 5-point scales, were related to values thatorganization members have about whistle-blowing. Data from all individ-ual respondents were included in a factor analysis. Thus respondentsincluded organization members who (a) had not observed wrongdoing,(b) had observed but not reported wrongdoing, and (c) had observed andreported wrongdoing (i.e., whistle-blowers). The beliefs expressed repre-sented those of the total membership of the organization and were notlimited to those of whistle-blowers.

Factor analysis with orthogonal rotation produced three factors, termed:positive beliefs about whistle-blowing, reflecting the view that whistle-blowing should be encouraged as a general rule; protection from retalia-tion, indicating a belief that management would protect whistle-blowersfrom retaliation; and knowledge about channels, suggesting that respon-dents knew where (i.e., to what agents) they could report wrongdoingwithin the organization (details are available from the authors). Organi-zations with positive values or a positive climate were those where

Near etal./VALUES AND PRACTICE 211

members felt that (a) whistle-blowing should be encouraged, (b) whistle-blowers would not suffer retaliation in their organizations, and (c) theyknew where to report wrongdoing. Results of the factor analysis areavailable from the first author.

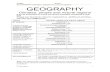

Indexes were computed by standardizing and summing the itemsloading on each factor. A mean and standard deviation were computed foreach agency on each factor scale. Higher scores indicated that morepositive values existed in the subsystem in terms of positive beliefs,protection from retaliation, and knowledge about whistle-blowing chan-nels (see Table 1).

Following Jones, James, Bruni, Hornick, and Sells (1979), we usedseveral methods of assessing the suitability of aggregating individualscores on beliefs regarding wrongdoing and whistle-blowing, to obtainsubsystem scores on values. These methods produced results that weconsider, on balance, supportive of our use of aggregated organizationmeasures of values.1

Measures of Practices i

Respondents were asked whether, within the past 12 months, theypersonally observed or had direct evidence of any of the following typesof wrongdoing: stealing funds, stealing property, accepting bribes, waste,abuse of position, unfair advantage given to a contractor, tolerating unsafepractices, or serious violation of law or regulation within their agency. Ameasure of the incidence of wrongdoing was calculated by dividing thenumber of respondent observers of wrongdoing within an agency by thetotal number of respondents from that agency ..This percentage figure thusrepresents a "per capita" measure of observed wrongdoing during the pastyear; it is concerned only with whether wrongdoing of any type—asdefined in the questionnaire—was observed. Characteristics of the wrong-doing are captured in the next measure, seriousness of wrongdoing.

Certainly the whistle-blowing process might vary somewhat with thenature of the wrongdoing observed. It is unclear, however, how thesevarious types of wrongdoing might be classified—for example, is abuseof position more similar to accepting bribes or stealing property? In aneffort to distinguish among the types of wrongdoing at the most basiclevel, we developed a measure of the seriousness of the wrongdoing; inso doing, we could assess possible differences in results associated withdifferences in a key aspect of the nature of the wrongdoing. In other words,

212 ADMINISTRATION & SOCIETY / August 1993

TABLE 1

Mean Scores and Standard Deviationsfor Each Agency on Three Measures of Values

Agency

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

PositiveBeliefs

13.86(1.99)13.70(2.02)13.81(1.89)13.62(2.14)13.27(2.61)13.71(2.32)13.83(1.81)13.70(1.99)13.76(2.06)13.75(1.98)13.80(1.92) ;13.71(2.26)13.73(2.19)14.13(1.87)12.80(2.05)

Factors

Protection fromRetaliation

5.52(2.41)5.29

(2.40)5.47

(2.37)4.99

(2.32)4.82

(2.42)5.35

(2.54)5.40

}•': (2.42)' • ' , „ 5.19

\>v(2.38)4.88

(2.39)5.41

(2.48)5.31

(2.42)5.25

(2.54)5.51

(2.40)5.05

(2.32)5.51

(2.50)

KnowledgeAbout Channels

0.26(1.85)-0.23(1.80)0.14

(1.90)0.29

(1.89)0.34

(1.93)1.00

(1.90)0.17

(1.90)0.03

(1.91)-0.08(1.92)1.25

(1.86)0.11

(1.86)0.51

(2.03)0.71

(1.94)0.94

(1.93)0.08

(1.85)

NOTE: Mean scores are given on top line followed by standard deviations in parentheses.

organizations where occasional pilfering of a few office supplies occurredwould not be lumped with organizations with serious instances of em-ployee stealing or bribe taking.

A measure of the seriousness of wrongdoing, based on dollar amountor frequency of the wrongdoing, and developed by Miceli and Near (1985)

Near etal./ VALUES AND PRACTICE 213

was used in the analysis. Observers of wrongdoing indicated the amountof money involved in the wrongdoing they observed, which was rated ona 3-point scale (1 = less than $999,2 = $1,000 to $100,000, and 3 = morethan $100,000). For types of wrongdoing where respondents could notassess the amount of money involved (e.g., abuse of position or unsafepractices), observers indicated how frequently the wrongdoing oc-curred and responses were also rated on a 3-point scale (1 = rarely, 2 =occasionally, and 3 = frequently). A measure of the seriousness of wrong-doing (ranging from 1 to 3) was created by giving each observer a scorebased on the cost of wrongdoing; when the cost could not be assessed, thefrequency was used instead. An average score was then computed for eachagency.

Our approach to assessing seriousness of wrongdoing is consistent withapproaches used in studies of illegal corporate behavior. In these studies,researchers have pointed out the problem of trying to assess the serious-ness of violations where some violations do not involve specific dollarlosses, monetary damages are not awarded (e.g., an injunction may be theremedy sought), violations continue for different lengths of time, and soforth; thus researchers have developed criteria to use in assigning a levelof seriousness to each violation (B^icus, 1987; Clinard, Yeager, Brissette,Petrashek, & Harries, 1979). Our assigning a value representing dollaramount or frequency of the wrongdoing is similar to these approaches.

Another indicator of subsystem practices was the incidence of whistle-blowing, measured by asking respondents who had observed wrongdoingin the organization whether they had reported it. The percentage ofobservers of wrongdoing who blew the whistle was created by dividingthe number of respondent observers within an agency who blew thewhistle by the total number of respondents in the agency who hadobserved wrongdoing (whether or not they had reported it).

Finally, respondents indicated whether they had experienced any or allof nine types of retaliation: poor performance appraisal, denial of promo-tion, denial of opportunity for training, assigned less desirable or lessimportant duties, transfer to less desirable job or other geographic loca-tion, suspension, or grade-level demotion. Respondents could also selectan other category. We computed an index of incidence of retaliation bydividing the number of retaliation incidents experienced by identified(i.e., nonanonymous) whistle-blowers in an organization by the numberof whistle-blowers who had been retaliated against, following Near andMiceli (1986). This represents a "per whistle-blower" percentage measureof the number of types of retaliation experienced by those whistle-blowers

214 ADMINISTRATION & SOCIETY / August 1993

who suffered retaliation. As noted by Parmerlee et al. (1982), the use ofincidence (in their terms, "comprehensiveness"), rather than intensity,provides an indication of "the degree to which the retaliation representeda generalized organizational reaction to the complaint, as opposed to anisolated incident sparked by one or two vindictive individuals" (p. 22);that is, it measures the degree to which the retaliation is a widespreadpractice within the subsystem rather than a limited one.

In computing the average scores for each agency on the three measuresof values and when computing the scores for the four practice measures(i.e., incidence and seriousness of wrongdoing, incidence of whistle-blowing, and incidence of retaliation), only responses of internal whistle-blowers were included. This was done because whistle-blowers whoreport wrongdoing externally may do so precisely because they do notfeel encouraged by a positive climate to report internally. Thus, if "exter-nals" were included, a high level of whistle-blowing would be difficult tointerpret.

Data Analysis'i.i

Zero-order correlational analysis was used to examine the relationshipsamong the scales measuring vahi^s—positive beliefs, protection for re-taliation, and knowledge of channels—and the measures of practice, thatis, incidence of wrongdoing, seriousness of wrongdoing, incidence ofwhistle-blowing, and incidence of retaliation. Although regression anal-ysis would have been preferred as a method of analysis, the small numberof cases (i.e., 15 agencies) made it inappropriate. Partial correlationanalysis was also used so that each of the hypotheses could be examinedwhile controlling for the relationships that might exist among wrongdo-ing, whistle-blowing, and retaliation. Because of the small number ofcases, these latter estimates may be somewhat unreliable, so they shouldbe viewed with caution.

RESULTS

Zero-order correlations, means, and standard deviations are presentedin Table 2. The zero-order correlations suggested moderately strongrelationships among some variables; to control for confounding of find-ings due to these intercorrelations, results of partial correlation analysis(see Table 3) were also calculated.2

Near etal./VALUES AND PRACTICE 215

TABLE 2

Mean Scores, Standard Deviations, andZero-Order Correlations Among Variables

Variable U SD 1 2 3 4

ValuePositive beliefsProtection from

retaliationKnowledge about

channelsPractice

Incidence ofwrongdoing

Seriousness ofwrongdoing

Incidence ofwhistle-blowing

Incidence ofretaliation

N=15.*p<. 05; **;><. 01.

13.97

4.84

0.57

42.33

2.16

0.31

0.26

0.34

0.48

0.58

4.58

0.20

0.07

0.18

j

.48*

.21 .27

-.29 -.31 -.11

-.49* -.63** .36 .22

.28 .12 .76** .29 .27

.17 -.42 .50* -.09 .53* .46*

We predicted that positive values would be negatively associated withthe incidence of wrongdoing. Although the relationships were all in thedirection predicted, none of the three measures of values—positive be-liefs, protection from retaliation, and knowledge about channels—wassignificantly related to the incidence of wrongdoing. Thus this hypothesiswas not supported.

A negative relationship between the measures of positive values andseriousness of wrongdoing was hypothesized. Strong support was ob-tained for the relationship between two of the measures of values, positivebeliefs and protection from retaliation, and the seriousness of wrongdoing.Another measure of values, knowledge about channels, was not signifi-cantly related to seriousness of wrongdoing. Overall, the hypothesisreceived moderate support.

Positive values were predicted to be positively associated with inci-dence of whistle-blowing. Strong support for this relationship was ob-tained for one of the values' measures, knowledge about channels. Theother two measures of values, positive beliefs and protection from retali-ation, were unrelated to the incidence of whistle-blowing. Thus supportfor the third hypothesis was weak.

216 ADMINISTRATION & SOCIETY / August 1993

TABLE 3Partial Correlations Among Variables8

Agency

Incidence of wrongdoingSeriousness of wrongdoingIncidence of whistle-blowingIncidence of retaliation

PositiveBeliefs

-.26-.68**

.42

.39

Values

Protection fromRetaliation

-.56*-.52*

.66**-.55*

KnowledgeAbout Channels

-.59*.38.81**

-.10

a. Partial correlation calculated as the correlation between each measure of values and eachmeasure of practices, controlling for the remaining three dependent variables.*/><.05;**p<.01.

A negative relationship was hypothesized to exist between positivevalues and the incidence of retaliation. Support for this hypothesis wasweak. Protection from retaliation, one of the values' measures, wasnegatively related to the incidence of retaliation but the relationship wasonly marginally significant (p( < .06). Further, a second measure ofvalues—knowledge about channels—was significantly related to theincidence of retaliation, but in a positive direction (contrary to prediction).No relationship was found between the third measure of values, positivebeliefs, and incidence of retaliation.

; DISCUSSION

This study differs from earlier research On whistle-blowing, because itfocuses on the role of values in influencing organization practices in theareas of wrongdoing, whistle-blowing, and retaliation. In general, theresults suggest that values are not strongly associated with practices. Ofcourse, this may be due to the limitations of the data that are discussedbelow.

Our concern is whether a subunit's values—defined as shared beliefsamong all subunit members—are related to subunits' practices. Theanswer is a qualified no. Instead, subunit members seem to commitwrongdoing and to retaliate against whistle-blowers irrespective of theirvalues; likewise, a higher incidence of observers of wrongdoing who blowthe whistle seems to result for reasons other than values, as measured here.Other unmeasured variables may be better predictors of wrongdoing,

Near etal./ VALUES AND PRACTICE 217

whistle-blowing, and retaliation than values, but the point remains thatvalues seem not to be strongly related to practices in organizations. Thisis consistent with path-breaking research on general organizational valuesand practices that showed values and practices to be only partly interre-lated (Hofstede et al., 1990)—contrary to the contention of popular writersthat the two are strongly correlated (e.g., Peters & Waterman, 1982).

Methodologically, our research differs from earlier studies of individ-ual whistle-blowers, because such studies often involved method covari-ance among the measures; for example, the same individual respondentdescribed his or her attitudes toward whistle-blowing and perceptions ofthe wrongdoing incident, likely causing some respondents to color theirperceptions so as to increase the consistency of their responses. Becausethe measures here were collected from different subsamples and wereaggregated to the subsystem level, this potential method covariance wouldnot influence our results, unless it had been particularly severe (this is notto say that other methodological problems did not occur but only that thisparticular problem did not arise).

As noted above, this interpretation of our findings assumes that theyare valid. The issue of validity must be considered for each of the specificfindings and it is to this task that we next turn our attention.

VALUES AND WRONGDOING

Our results indicated that incidence of wrongdoing was not signifi-cantly related to values. This is consistent with earlier research showingthat the use of codes of ethics, presumably a statement of the organization'svalues, was unrelated to corporate wrongdoing (Mathews, 1988). Valuesregarding whistle-blowing may be unrelated to the incidence of wrong-doing; on the other hand, the measures in this study may not have fullytapped all relevant values, and range restrictions in the values' measuresmay have attenuated the results.

However, managers and researchers need to be concerned not onlywith the incidence of wrongdoing in organizations but also with theseriousness of wrongdoing that occurs. More serious wrongdoing is likelyto be more costly to the organization and may also harm the organization'sability to compete and survive. Our results indicated that values encour-aging whistle-blowing and protection from retaliation are associated withless serious wrongdoing. Unfortunately, causality cannot be inferred fromthese results. Organization members' beliefs that whistle-blowing benefitsthe organization and that whistle-blowers will be protected from retalia-

218 ADMINISTRATION & SOCIETY / August 1993

tion may prevent individuals from engaging in serious wrongdoing (e.g.,out of fear that they will be reported or because they identify more closelywith the organization). On the other hand, very low levels of seriouswrongdoing may create a climate in which individuals believe that whistle-blowing would be regarded favorably and that an effort would be madeto see that retaliation against whistle-blowers could not occur. Alterna-tively, some other, unknown variable may even intervene in the relation-ship between these measures. These questions can be answered onlythrough future research; however, the findings do indicate the need toseparate wrongdoing into variables measuring both the incidence andseriousness of wrongdoing, because each of these was related differentlyto different dimensions of values.

VALUES AND WHISTLE-BLOWING

Likewise, in this study, a climate where individuals had knowledgeabout where to report wrongdoing was positively related to the incidenceof whistle-blowing. Future research should investigate the causal relation-ship existing between these variables, that is, whether more whistle-blowing leads to more knowledge about where to report wrongdoing orvice versa. However, incidence o!fxwhistle-blowing was unrelated to eitherof the other two values' measures.

VALUES AND RETALIATION

Because whistle-blowers tend to be visible in the organization (Naderetal., 1972;Weinstein, 1979; Westin, 1981) and may serve as role modelsin helping to establish the beliefs and norrns regarding both wrongdoingand whistle-blowing, it is important to also consider what happens toindividuals who do report wrongdoing. In particular, it was expected thatthe organization's values would be negatively associated with the inci-dence of retaliation, but this received very little support.

Although we cannot determine the causal ordering, it is clear fromTable 2 that incidence of whistle-blowing was positively correlated withincidence of retaliation; further, the measure of values, knowledge aboutchannels, was positively associated with both of these incidence figures.In other words, in organizations where whistle-blowing occurred fre-quently, the average number of retaliation incidents suffered by those whoreported retaliation was likely to be higher than in those organizationswhere the frequency of whistle-blowing was lower. Moreover, both the

Near et al. / VALUES AND PRACTICE 219

incidence of whistle-blowing and the incidence of retaliation were likelyto be higher where organization members reported greater levels ofknowledge about channels for whistle-blowing. We could speculate thatthis knowledge led observers of wrongdoing to be more sensitive to themeans for reporting it (therefore resulting in whistle-blowing) and moresensitive to retaliation actions.

A more plausible explanation is that the correlation between knowl-edge and retaliation was spurious and was based solely on the confound-ing of each of these variables with incidence of whistle-blowing. Thislatter explanation was supported by the results of partial correlation,which indicated that the correlation between knowledge of channels andretaliation disappeared when the effects of incidence of whistle-blowingwere controlled; however, we must regard this interpretation as tentativebecause the use of partial correlation with a small sample may produceunreliable findings.

IMPLICATIONSi

Our results are important because they call into question some of thecurrent advice given to managers in organizations. For instance, managingcorporate culture has gained much attention since popular writers (e.g.,Peters & Waterman, 1982) maintained that organization culture is animportant predictor of organization actions; however, our results do notsupport this widely held assumption. Instead, organizational values arenot always related to the actual practices or events taking place currentlywithin the organization. There are at least three possible reasons for this.

One explanation is that an organization's values are based on its history.We would expect a time lag between the period in which new eventsoccurred that might require revision of the value system and the period inwhich actions based on that value system are finally changed to reflectthe new knowledge.

A second and related reason is that the lag is not merely one of timebut is rather due to differential knowledge among an organization'smembers. Although values must, by definition, be widely shared, morerecent events in the organization's life may not be completely known byall of its members. Communication of these events will of necessitydepend on the efficacy and breadth of the organization's communicationsystem, which, in turn, depends on other variables such as organizationalsize, complexity, and geographic dispersion. This finding is analogous tothe widely understood proposition in social psychology that individuals'

220 ADMINISTRATION & SOCIETY / August 1993

attitudes are not always related to their behaviors. At the system orsubsystem level, as well, the organization's values may not always predictthe actual behavior of its members, except in highly ritualized situations(Goodenough, 1981).

Third, our study has not considered whether precursors of the organiza-tion's values or other variables might mediate or moderate the effects ofvalues on wrongdoing, whistle-blowing, and retaliation. Measures of suchvariables were not available in our data set but should be considered infuture research.

For example, organization structures or reward systems might create agap between values and practices that are consistent with subsystemvalues. Likewise, the depth of commitment to the organizational climate—orits strength—may be more important than the existence of a positiveclimate; in a similar vein, Hofstede et al. (1990) found that the strength of anorganization culture (measured as the standard deviation on the organizationaggregate measure) was an important predictor of practice.

Because there is a trend toward holding top managers accountable forwrongdoing that occurs in their organizations (Ermann & Lundman,1982), managers must be concerned not only with whistle-blowing orreporting of wrongdoing but alsp with the occurrence and seriousness ofthe wrongdoing itself. Manager^ l^eed to pay attention to the shared valuesorganization members have about the appropriateness of whistle-blowingand the degree of protection from retaliation whistle-blowers will receive,because these values appear to be significantly associated with less seriouswrongdoing. Research investigating the causal nature of this relationshipis necessary so researchers will know whether current efforts to preventretaliation or protect whistle-blowers ("Beyond Unions," 1985; Malin,1983; USMSPB, 1981) will eventually pay off in less serious wrongdoing.

On the other hand, such research may discover that efforts are betterspent on reducing wrongdoing, particularly serious wrongdoing, improv-ing communication channels or reporting relationships and reducingwidespread retaliation (e.g., punishing individuals who engage in retali-atory behaviors), because this eventually establishes a climate whereindividuals feel positively about whistle-blowing and believe they will beprotected from retaliation.

LIMITATIONS

Six potential limitations of these results should be noted. First, ourdefinition and measurement of variables should be examined in future

Near etal./VALUES AND PRACTICE 221

research. For example, our measure of climate is idiosyncratic, a propertythat may be important in measuring a construct that is unique to a set oforganizations or to a particular issue within those organizations (Fryxell,Enz, & Grover, 1989). As such, it is of necessity an ambiguous concept.Following Fryxell et al. (1989), we have defined values narrowly as sharedbeliefs about wrongdoing, whistle-blowing, and retaliation—rather thanusing the more general approach exemplified by Hofstede et al. (1990).Similarly, our measure of seriousness of wrongdoing attempted to deter-mine a relatively objective indication of the damage caused by thewrongdoing; the meaning of this assessment to the respondent was notdetermined. Our measure of retaliation also was specifically defined, anddid not include potential sources of retaliation from co-workers (e.g.,ostracism) or from others besides managers.

Second, we report ecological correlations (correlations betweengroups of persons) that can be expected to be somewhat larger thanindividual correlations (Robinson, 1950). However, the strength of thesignificant correlations suggests that this is not a major limitation inthis study; even if they were somewhat inflated, the results indicatestrong relationships.

Third, as noted earlier, the collusions that can be drawn from thisstudy are limited by the use of cross-sectional data analysis, which doesnot permit causal interpretations.

Fourth, the small number of agencies sampled precludes the use ofmore sophisticated methods of analysis. Thus the results must be viewedwith caution. The present study should be regarded as exploratory; futureresearch should use a larger sample to permit the use of more sophisticatedstatistical analyses (e.g., regression).

Fifth, as noted earlier, there were small differences among agencies invalues variables, which likely weakened the relationships with the prac-tices variables.

Finally, the use of data of U.S. government agencies in 1980 for thissample may limit generalizability of the results to other samples. How-ever, Miceli and Near (1984) described several reasons why the whistle-blowing process may be similar in public and private sector organizationsand suggested that generalizability can be addressed by future empiricalwork. Further, research completed somewhat more recently in theseorganizations (USMSPB, 1984) suggests little real difference in organi-zation practices over that time period (Miceli & Near, 1989). In fact,despite substantial changes in state statutes, whistle-blowers do not seemto be much better off in 1990 than they were in 1980 (Dworkin & Near,

222 ADMINISTRATION & SOCIETY / August 1993

1987). Further, our focus here is not on absolute levels of current valuesand practice but in the relationship between the two, which we would notexpect to fluctuate greatly. It should be noted, however, that cross-culturalvariations in employment law and practice potentially limit the generalizabil-ity of our results to the United States.

In summary, understanding the relationships between an organization'svalues and the incidence, seriousness and reporting of wrongdoing, andcomprehensiveness of retaliation has important implications for manag-ers, as well as organization theory. Being able to understand and predictthese relationships and their effects on an organization will elucidateprocesses of change in organizations.

NOTES

1. First, we used three analyses of variance to determine significant differences in beliefsassociated with organization members. The results (available from authors) indicated thateach of the three indexes of values showed significantly smaller levels of variance withinsubsystems than between subsystems. This is not particularly surprising, because theagencies included very different subsystems of the government, ranging from Health andHuman Services to the Department of Uabor to the Department of Agriculture, each of whichis located in a different geographical area and with vastly different goals and mandates. Infact, additional data collected earlier from these agencies indicated that the kinds of materialsconcerning whistle-blowing that each agency made available to its members varied radicallybetween subsystems (Miceli & Near, 1985). Specifically, each of the agencies was requestedto send copies of their code of ethics and any other supporting materials that they routinelygave employees outlining their policies on the assessment and reporting of organizationalwrongdoing. Each agency had prepared different materials, presumably reflecting theirofficial or institutional view of wrongdoing and whistle-blowing. All employees within eachagency were given access to these materials, suggesting that similar institutional values wereespoused within each subsystem but that these varied across subsystems. In addition, theagencies have mounted different forms of employee involvement programs (U.S. MeritSystems Protection Board [USMSPB], 1986) that reflect their different subsystem climatesand should certainly impact their frames (Wilkins & Dyer, 1988) regarding whistle-blowing.Beyond this, actual practice differed dramatically between agencies, because the incidenceof wrongdoing and the types of wrongdoing were very different in each subsystem (USMSPB,1981).

Second, we assessed interperceiver reliability or agreement within subsystems, using etasquared, a measure of linear and nonlinear association between the individual values scoresand membership in a particular agency. Here, the results were less supportive, as theeta-squared figures were very small, ranging from .004 to .03. In other words, althoughthe values expressed in each of the 15 agencies differed significantly in a statistical sense,the strength of the difference is low. This is probably not surprising, because each of thesubsystems is part of the U.S. government and is subject to a fairly standard set of regulationsand personnel procedures. Moreover, this result is consistent with the work of Hofstede et al.

^

Near etal./VALUES AND PRACTICE 223

(1990), in which between-organization scores on general values were found to vary signif-icantly but not substantially; national identity was a stronger predictor of values than wasorganizational culture. Thus our findings may suggest an American value supportingwhistle-blowing that would hold in most American organizations, including agencies of thefederal government. We cannot assess whether this reflected a measure of respondents' views(i.e., valid Americans generally believe in reporting wrongdoing) or lack of sensitivity ofthe measures to true differences among respondents. In any event, the lack of heterogeneityin the agencies may have reduced the variance in the values' measures.

Third, Jones, James, Bruni, Hornick, and Sells (1979) argue that aggregation scoresshould be taken only when the situational characteristics of the subsample are similar. It isnot clear here which characteristics to select, but the subsystem mission, job types, andorganization context of respondents in the agencies were probably similar. For example, thevarious mechanisms for blowing the whistle should be fairly standard for all members of aparticular agency.

Finally, we should see "meaningful relationships between the aggregated score andvarious organizational, subunit, or individual criteria" (Jones et al., 1979, p. 208). Thiscriterion is probably impossible to apply to this sample, because organizational climate, bydefinition, has no corresponding measure at the individual or subunit level of analysis.

2. Results of the partial correlation analysis were somewhat more supportive of thehypotheses and are available from the authors. These results may be instructive, becausethey were based on an analysts that allowed us to control for the intercorrelation amongthe measures of values. On the other hand, the results of the partial correlation analysis maybe unreliable due to the small number of cases. ".

xTv. • -

REFERENCES

Baucus, M. (1987). Antecedents and consequences of illegal corporate behavior. Unpub-lished doctoral dissertation, Indiana University.

Beyond unions: A revolution in employee rights is in the making. (1S85, July). BusinessWeek, pp. 72-76. i

Burnett, A. L. (1980). Management's positive interest in accountability through whistleblow-ing. The Bureaucrat, 9, 5-10.

Cherrington, D. J., & Cherrington, J. O. (1981, July). The climate of honesty in retail stores.Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association, LosAngeles, CA.

Clinard, M. B., Yeager, P. C, Brissette, J., Petrashek, D., & Harries, E. (1979). Illegalcorporate behavior. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute forLaw Enforcement and Criminal Justice.

Dworkin, T., & Near, J. P. (1987). Whistle-blowing statues: Are they working? AmericanBusiness Law Journal, 25, 241-264.

Enz, C. A., & Schwenk, C. R. (1989, August). Performance and the sharing of organizationalvalues. Paper presented at the meeting of the Academy of Management, Washington,DC.

Ermann, M. D., & Lundman, R. J. (1982). Corporate deviance. New York: Holt, Rinehart &Winston.

Ewing, D. (1983). Do it my way—or you 're fired! New York: Wiley.

224 ADMINISTRATION & SOCIETY / August 1993

Farrell, D., & Petersen, J. C. (1982). Patterns of political behavior in organizations. Academyof Management Review, 7, 403-412.

Fryxell, G. E., Enz, C. A., & Grover, R. (1989, April). Flexible instrumentation: A guide formeasuring partially idiosyncratic constructs. Paper presented at the meeting of theMidwest Academy of Management, Columbus, OH.

Goodenough, W. H. (1981). Culture, language and society. Menlo Park, CA: Benjamin/Cummings.

Graham, J. W. (1983). Principled organizational dissent. Unpublished doctoral dissertation,Northwestern University.

Graham, J. W. (1984). Organizational response to principled organizational dissent. Paperpresented at the meeting of the Academy of Management, Boston, MA.

Hofstede, G., Neuijen, B., Ohayv, D. D., & Sanders, G. (1990). Measuring organizationalcultures: A qualitative and quantitative study across twenty cases. Administrative ScienceQuarterly, 35, 286-316.

Jones, A. P., James, L. R., Bruni, J. R., Hornick, C. W., & Sells, S. B. (1979). Psychologicalclimate: Dimension and relationships of individual and aggregated work environmentperceptions. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 23, 201-250.

Joyce, W. F., & Slocum, J. (1982). Climate discrepancy: Refining the concepts of psycho-logical and organizational climate. Human Relations, 35(11), 951-972.

Kanter, R. M. (1983). The change masters: Innovation for productivity in the Americancorporation. New York: Addison-Wesley.

Keenan, J. P. (1988). Communication climate, whistle-blowing, and the first-level manager:A preliminary study. Academy of Management Best Papers Proceedings, 49, 247-251.

Malin, M. (1983). Protecting the whistle-blower from retaliatory discharge. University ofMichigan Journal of Law Reform, I& 277-318.

Mathews, M. C. (1988). Strategic intervention in organizations: Resolving ethical dilemmas.Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Miceli, M. P., Dozier, J. B., & Near, J. P. (1991). Blowing the whistle on data-fudging: Acontrolled field experiment. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 21, 271-295.

Miceli, M. P., & Near, J. P. (1984). The relationships among beliefs, organizational position,and whistle-blowing status: A discriminate analysis. Academy of Management Journal,27, 687-705.

Miceli, M. P., & Near, J. P. (1985). Characteristics of organizational climate and perceivedwrongdoing associated with whistle-blowing decisions. Personnel Psychology, 38,525-544.

Miceli, M. P., & Near, J. P. (1988, August). Retaliation against role-prescribed whistle-blow-ers: The case of internal auditors. Paper presented at the 48th annual meeting of theAcademy of Management, Anaheim, CA.

Miceli, M. P., & Near, J. P. (1989). Incidence of wrongdoing, whistle-blowing, and retalia-tion: Results of a naturally occurring field experiment. Employee Responsibilities andRights Journal, 2, 91-108.

Miceli, M. P., & Near, J. P. (1992). Blowing the whistle: The organizational and legalimplications for companies and employees. New York: Lexington.

Miceli, M. P., Roach, B. L., & Near, J. P. (1988). The motivations of anonymous whistle-blowers: The case of federal employees. Public Personnel Management, 17, 281-296.

Nader, R., Petkas, P., & Blackwell, K. (1972). Whistle-blowing: The report on the conferenceof professional responsibility. New York: Grossman.

Near etal./VALUES AND PRACTICE 225

Near, J. P., & Jensen, T. C. (1983). The whistle-blowing process: Retaliation and perceivedeffectiveness. Work and Occupations, 10, 3-28.

Near, J. P., & Miceli, M. P. (1985). Organizational dissidence: The case of whistle-blowing.Journal of Business Ethics, 4, 1-16.

Near, J. P., & Miceli, M. P. (1986). Retaliation against whistle-blowers: Predictors andeffects. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71, 137-145.

Near, J. P., & Miceli, M. P. (1987). Whistle-blowers in organizations: Dissidents or reform-ers? In L. L. Curamings & B. M. Staw (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior(pp. 321-368). Greenwich, CT: JAI.

Parmerlee, M. P., Near, J. P., & Jensen, T. C. (1982). Correlates of whistle-blowers'perceptions of organizational reprisal. Administrative Science Quarterly, 27, 17-34.

Peters, T., & Waterman, R. (1982). In search of excellence. New York: Harper & Row.Posner, B. Z., Kouzes, J. M., & Schmidt, W. H. (1985). Shared values make a difference:

An empirical test of corporate culture. Human Resource Management, 24(3), 293-309.Powell, G. N., & Butterfield, D. A. (1978). The case for subsystem climates in organizations.

Academy of Management Review, 3, 151-157.Riley, P. (1983). A structurationist account of political culture. Administrative Science

Quarterly, 28, 414-437.Robinson, W. (1950). Ecological correlations and the behavior of individuals. American

Sociological Review, 15, 351-357.Schneider, B., & Reichers, A. (1983). On the etiology of climates. Personnel Psychology,

36, 19-39. \Stanley, J. D. (1981). Dissent in organizatipns. Academy of Management Review, 6, 13-19.Stone, C. D. (1975). The culture of the corpora^tm^ Where the law ends. New York: Harper & Row.Taylor, W., & Cangemi, J. (1979). Employee theft and organizational climate. Personnel

Journal, 58, 686-688.U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board (USMSPB). (1981). Whistle-blowing and the federal

employee. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board (USMSPB). (1984). Sexual harassment in the federal

government: An update. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board (USMSPB). (1986). Getting involved: Improving

federal management with employee participation. Washington, DC: U.S. GovernmentPrinting Office.

Weber, M. (1947). The theory of social and economic organization (A. H. Henderson &T. Parsons, Trans.). Glencoe, IL: Free Press. (Original work published 1925)

Weinstein, D. (1979). Bureaucratic opposition. New York: Pergamon.Westin, A. (1981). Whistle-blowing. New York: McGraw-Hill.Wilkins, A. L., & Dyer, W. G. (1988). Toward culturally sensitive theories of cultural change.

Academy of Management Journal, 13(4), 522-533.Zalkind, S. S. (1987, August). Is whistle-blowing climate related to job satisfaction and other

variables? Paper presented at the meeting of the American Psychological Association,New York, NY.

Janet P. Near is Professor and Chairperson of the Department of Management andAdjunct Professor in the Department of Sociology at Indiana University. She receivedher B.A. degree from the University of California, Santa Cruz, and her M.A. and

226 ADMINISTRATION & SOCIETY / August 1993

Ph.D. degree from the State University of New York, Buffalo. Her research interestsinclude (a) whistle-blowing in organizations and (b) the relationship between workand nonwork domains of life, focusing especially on the correlation between job andlife satisfaction. She has published over 40 journal articles on these topics and hastaught in the areas of organization design and development. She is an officer of theBoard of Governors of the Academy of Management Association and a member ofthe editorial board of the Journal of Business Ethics.

Melissa S. Baucus received her Ph.D. degree from Indiana University and iscurrently Assistant Professor in the Department of Management at the University ofKentucky. Her research interests include illegal corporate behavior, wrongful firing,and whistle-blowing and she has published several articles on these topics. Sheteaches courses on organization design and strategic management.

Marcia P. Miceli earned the A.B. with honors in psychology, the Master of BusinessAdministration, and the Doctorate of Business Administration from Indiana Univer-sity. She is currently Professor and Chair of the Department of Management andHuman Resources at Ohio State University. Professor Miceli has taught courses inhuman resources management, compensation, and staffing. She has published andpresented numerous articles, primarily on pay satisfaction and on whistle-blowing(the reporting of organizational wrongdoing). Professors Miceli and Near are theauthors of Blowing the Whistle: The Organizational and Legal Implications forCompanies and Employees (Lexington Books, 1992).

\'U

Related Documents