The Long-Run Influence of Institutions Governing Trade: The Case of Colonial and Pirates’ Ports in Mexico Daphne Alvarez Villa § Jenny Guardado † First Draft. January 2016 Abstract In this paper we examine the long-term development impact of legal versus illegal overseas trade in colonial Mexico. While there is ample evi- dence that commercial activity may lead to sustained economic benefits, it is unclear whether these effects are driven by commercial activity per se or by the accompanying state institutions that positively impact development (e.g. tax-collection and legal enforcement). Using historical sources on the presence of smuggling and piracy in Mexican coasts from the 16th to 18th century we find that the presence of trade, either in its legal or illegal form, leads to significantly better development outcomes compared to neighboring areas where such activities were absent. Results are robust to instrument- ing trade with natural harbors and are not driven by a mechanical effect of carrying out trade in the present, by the length of colonial presence, or by substantial geographical differences. These findings suggest that the posi- tive impact of illegal trade may have compensated for the damaging effects of a weaker state presence and the culture of illegality surrounding it. Keywords: Colonial Trade, Institutions and Growth, Smuggling and Piracy, Mexico. JEL Classification: N76, N46, O17, O43. § University of Oxford. Email: [email protected]; † Georgetown University. Email: [email protected] 1

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

The Long-Run Influence of Institutions Governing

Trade: The Case of Colonial and Pirates’ Ports in

Mexico

Daphne Alvarez Villa§ Jenny Guardado†

First Draft. January 2016

Abstract

In this paper we examine the long-term development impact of legalversus illegal overseas trade in colonial Mexico. While there is ample evi-dence that commercial activity may lead to sustained economic benefits, itis unclear whether these effects are driven by commercial activity per se orby the accompanying state institutions that positively impact development(e.g. tax-collection and legal enforcement). Using historical sources on thepresence of smuggling and piracy in Mexican coasts from the 16th to 18thcentury we find that the presence of trade, either in its legal or illegal form,leads to significantly better development outcomes compared to neighboringareas where such activities were absent. Results are robust to instrument-ing trade with natural harbors and are not driven by a mechanical effect ofcarrying out trade in the present, by the length of colonial presence, or bysubstantial geographical differences. These findings suggest that the posi-tive impact of illegal trade may have compensated for the damaging effectsof a weaker state presence and the culture of illegality surrounding it.

Keywords: Colonial Trade, Institutions and Growth, Smuggling and Piracy,Mexico.

JEL Classification: N76, N46, O17, O43.

§University of Oxford. Email: [email protected]; †Georgetown University.

Email: [email protected]

1

1 Introduction

The idea that free commercial activity is economically beneficial to both house-

holds and nations dates back to David Ricardo’s Principles of Political Economy

and Taxation. Indeed, a number of studies document not only how commercial

activity creates wealth in the short and long-term (Jia, 2013) but how it may

lead to greater inter-ethnic cooperation and social peace (Jha, 2013); the emer-

gence of institutions favoring long-run growth (Acemoglu et al., 2005); and the

diversification of economic activities (Gaikwad, 2015). Despite these findings, it

is less well understood whether the “benefits” from trade are driven by commer-

cial activities per se or by its surrounding institutions enabling tax-collection,

legal enforcement, and the formal organization of the economic activity. In this

paper we exploit variation in the conditions governing overseas trade in colonial

Mexico to better understand its long run development impact.

Specifically, we trace the contemporary effect of colonial trade in Mexico

under two different historical arrangements (henceforth “treatments”): first,

commercial activities conducted in legally designated ports and overseen by the

Spanish Crown – which we denominate legal trade or puertos unicos. Second,

international trade carried-out in clandestine ports at the shadow of colonial law

– which we call smuggling or illicit commerce. Although colonial trade was a key

element in the relations between Spain and the American colonies, it was very

restrictive: commercial activity had to be conducted in specific ports, by des-

ignated carriers, and in specific quantities. To enforce these rules, the Spanish

Crown developed a cumbersome bureaucratic system in official ports to oversee

the export-import of goods, collect taxes, and control the quantities and types

of goods. Not surprisingly, alternative arrangements – namely, a large smug-

gling industry – immediately emerged to satisfy the unmet demand for goods of

the colonial population. Private individuals, generally of foreign origin (French,

Dutch and British) would bring their cargo to Mexican shores to be purchased

by local merchants or other intermediaries without the vigilant eye of the Crown.

It is estimated that a large share of goods in colonial Mexico came from contra-

band trade in “pirate-ports”.

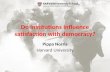

Figure 1 below displays the geographical distribution along the Mexican

coastline of known points in which smuggling and piracy took place. As no-

ticed, these were distributed all along the Pacific, Gulf of Mexico, and Caribbean

coasts. Marked with a crown were the unique ports enabled to trade by the Span-

2

ish Crown: Veracruz and Acapulco, and later Campeche. Not surprisingly, there

is less smuggling in areas sparsely populated such as the Gulf of California and

northern Mexico.

Figure 1: Points of Trade (Legal and Illegal)

Precise locations in latitude and longitude. Crown symbol: Official Ports. Skull symbol:

historical pirate presence. Note: only includes certain areas of former New Spain (Audiencia

of Mexico and Nueva Galicia). Points inland indicate that they were accessed through rivers

from the sea.

The main empirical challenge to study the impact of these different trade

arrangements is that several conditions enabling trade (either legal or illegal)

may have also led to different economic outcomes in the long-run. Pre-colonial

conditions such as proximity to population centers, mineral resources and mar-

kets, or the disease environment, may have influenced the choice of certain ports

versus others thus confounding our estimates. Our empirical strategy deals with

this concern in three ways: first, we limit our comparisons to the neighboring

areas of treated1 municipalities to control for common observable and unobserv-

able factors. Second, we identify all natural harbors along the Mexican coastline

as a source of exogenous variation in the possibility to trade, thereby limiting

the sample to those municipalities with this clear (and common) geographical

advantage. We then compare treated natural harbors with natural harbors in

the vicinity that could have been used for maritime trade but for some arbitrary

reason were not. Finally, we look at development outcomes within the munici-

pality (at the locality level) to control for potential municipality-wide effects not

1i.e. ports experiencing legal or illegal trade

3

driven directly by the presence of historical trade ports.

Our empirical findings show that municipalities containing a port with either

Spanish or pirate colonial trade display significantly better long run development

outcomes compared to neighboring areas and other natural harbors where such

activities were absent. In particular, places with historical commercial activity

exhibit a lower share of the population under conditions of poverty or lacking

basic utilities, and higher municipal tax income per capita. We further find that

these results are not driven by a mechanical effect of carrying out trade in the

present, by the length of colonial presence, or by substantial geographical differ-

ences among harbors. These findings suggest that the presence of commercial

activity per se, either under the vigilant eye of the Crown or via smuggling, had

a lasting impact on the development. As a robustness check, we also exploit the

presence of a natural harbor as an instrument for illegal trade and our estimates

are similar. Overall, results suggest that relative underdevelopment in coastal

Mexican municipalities today may be driven by a historical lack of access to the

market.

Although our results for municipalities with legal colonial trade are some-

what expected, those associated with piracy and smuggling are rather surpris-

ing. Conventional wisdom and other academic studies suggest that smuggling

may be detrimental for long-run economic growth and development for numerous

reasons: first, by fostering a culture of informality and illegality in detriment of

revenue collection; second, the weaker presence of the state may make it diffi-

cult to enforce contracts and protect property rights thus depressing economic

activity; and finally, colonial smuggling was at times accompanied by piracy and

these ports were often subject to armed attacks and pillage, particularly during

the 16th and 17th century.

Instead, our findings suggest that the presence of smuggling during colonial

times may have created the necessary conditions to benefit from trade liberal-

ization in the late 18th century (comercio libre) and after independence (1821).

For instance, merchants with the “know-how” and experience of clandestine net-

works had an advantage in the business once trade restrictions were lifted. Such

an early start in commercial activities (either legal or illegal) may have compen-

sated for the damaging effects of a weak state presence and supports an emphasis

on increasing returns to scale mechanisms (Krugman 1991): initial advantages

may have amplified over time even if other ports would have been equally opti-

4

mal for this activity. These effects are likely to persist even after international

trade stopped being their main economic activity2 and is consistent with findings

in other countries, such as treaty-ports in China (Jia 2013).

The paper contributes to the literature in several ways. First, our findings

indicate that historical trade in Mexico led to important developments on eco-

nomic activity not driven by the presence of formal institutions enabling rulers

to commit ex-ante to protect property rights (Acemoglu et al. 2005) or to coor-

dinate traders’ actions, such as merchant guilds (Greif 1992: 129). If anything,

the presence of smuggling weakened institutions monopolizing trade such as the

Mexican Merchant Guild (Consulado de Mexico) as well as the development of

formal institutions that may constrain rulers.

Rather, this paper highlights the importance of informal (de facto) arrange-

ments in order to understand colonial legacies. As pointed out by other studies,

the presence of extractive colonial institutions may have created lasting incen-

tives to deviate from the law, thus explaining a persistent gap between de jure

and de facto institutions (Alvarez-Villa 2016). However, deviating from an ex-

tractive colonial law may also be long-term beneficial, as illustrated by the case

of commercial contracts between indigenous producers and state officials in colo-

nial Mexico. For instance, Jha and Diaz-Cayeros (2013) find that places where

indigenous producers of cochineal were better able to renege from unfavorable

trade contracts and sell their crop on the spot market tend to be more devel-

oped in the long run. Our paper complements this perspective: circumventing

Spanish restrictions on trade and the inability of the state to enforce its laws

may have been long-term beneficial even if at the margin of the existing legal

framework.

Finally, we call for a more nuanced view on the role of informality on long-

run economic development in the context of extractive states. While most of

the contemporary literature highlights the negative aspects of informality linked

to tax-evasion, low labor productivity, and market uncertainty (Levy 2007), il-

licit trade might have provided experience with international markets otherwise

monopolized by Mexico city merchants and the two designated ports for trade

during most of the colonial period (Acapulco and Veracruz). Since the official

policy during colonial times was to de-populate coastal areas (De Ita Rubio

2Today, Mexico is not a maritime power with only a few ships and a limited number of ports(De Ita Rubio 2012:163)

5

2012: 201) – partly to protect the population from pirates and smugglers – in

the absence of smugglers, many of these ports would have lagged behind and

performed equally poor as those places that could have sustained trade during

colonial times but did not. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first paper

to explore the long-term development consequences of smuggling activities in

colonial Mexico.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents a brief

historical review on colonial trade and smuggling in Spanish America. Our data

is described in section 3. In section 4 we explain our empirical strategy for the

identification of the Spanish and piracy treatment effects. Section 5 reports main

results and robustness checks. Finally, section 6 concludes.

2 Colonial trade and smuggling in Spanish America

Overseas trade was a central feature of the colonial system linking the Iberian

metropolis to the colonial territories in the Americas and Asia. Yet, very early on

trade became a royal monopoly whose administration was granted to merchant

houses located in Seville, some of which were acquainted with Hernan Cortes (del

Valle Pavon 2012: 20). This arrangement would have important consequences

both for Seville and Mexico city: the former became one of the most important

markets and financial centers in Europe in the 16th century while the latter be-

came the economic and political center of New Spain.

The establishment of the trade monopoly between Spain and the American

was in-line with mercantilistic thinking at the time.3 Under this approach “state

authorities seek national economic self-sufficiency and organize productive activ-

ity to ensure favorable trade balances and the accumulation of precious metals”

(Mahoney 2010: 21).Hence, restricting trade with the Americas was a key in-

strument to achieve multiple objectives such as securing markets for Spanish

manufacturers, revenue collection, and keeping foreign merchants and armies at

bay.

Not surprisingly, monopolistic regulations greatly benefited a limited number

of groups (e.g. Seville and Mexico City merchants) at the expense of other mer-

chants and consumers in the colonies who paid relatively higher prices than they

3This would change towards the end of the colonial period under Bourbon rule.

6

would have otherwise. For this and other reasons, the Spanish trade framework

with the colonies is often described as “biased towards the metropolitan country

[...] for the economic exploitation of colonial territories” (Kleiman, 1976: 459).

This mercantilist approach to trade stands in stark contrast to that fol-

lowed by other nations at the time, most notably Britain and the Nether-

lands. In the latter cases, the state sought to “protect trade and production

for profit”(Mahoney 2010: 22) even if this led to economic gains to those outside

the royal circle. In fact, political development in Britain and the Netherlands,

such as the establishment of political checks on the monarchy, has been closely

linked to the rise of commercial interests and a merchant class able to bring about

institutional change in the 16th and 17th century (Acemoglu et. al. 2005). In

contrast, concentrated gains in the royal circle of Spain and Portugal hindered

the prospects of limiting the power of the Crown in the 17th century. For in-

stance, the windfall of gold and silver from the Americas allowed the Spanish

Crown to circumvent the Cortes (the closest it had to a representative institu-

tion) to obtain revenue and consolidate its power (Drelichman and Voth 2008).

From other viewpoints, the establishment of the trade monopoly was driven

by the special needs of trading with the Americas. Travel costs and risks were

specially high, making it necessary for trade to be conducted under the protec-

tion of the Spanish Crown and linked by family ties, location and patronage

networks (Del Valle Pavon 2012: 22). Such arrangements served as warranties

for individuals willing to engage in discovery, colonization and commerce. By

acting as a guarantor, the Crown’s monopolistic arrangements allowed enough

capital to be raised for these purposes, despite of long waiting periods for returns,

as well as risks involved in sailing to distant and “barbarous” places (Hamilton,

1948).

Finally, the trade monopoly also reduced the likelihood that colonial pro-

duction of gold and silver could be used to purchase foreign goods, thereby

undermining the exports of these precious metals to Spain. For instance, com-

mercial activities with foreigners using gold or silver could only be possible when

exchanging African slaves (Del Valle Pavon 2012: 49). The discovery of large

amounts of gold and silver in Spanish colonies also contributed to the creation of

“one of the most rigid systems of state regulation of colonial trade ever adopted

by any country” (Hamilton, 1948: 41).

7

2.1 Spanish trade to the colonies

Spanish trade with the colonies, molded on the mercantilistic tradition, had the

following characteristics: First, it restricted the number of actors who could of-

ficially engage in this activity. For instance, only “official fleets” were allowed

to enter and leave Spanish ports. Foreigners wishing to trade with the colonies

would need to become “naturalized” or partner with Spanish companies. The

Crown also established severe immigration restrictions for individuals of Jewish

or Arabic origin, and any foreigner more generally (Suarez Arguello 2012: 147).

By royal decree, territories under Spanish rule were obliged to buy and sell

only from authorized Spanish merchant houses; thereby, direct trade between

the colonies and other foreign powers was considered illicit (Christelow 1942:

309). These restrictions were meant to guarantee favorable terms of exchange

and rent accumulation, thus making trade highly profitable for a select group of

merchants in the metropolis.

Second, along with limiting the number of actors involved, it also limited the

designated “ports of entry”, and goods were heavily taxed upon arrival. Ships

coming directly from Spain were only allowed to arrive in major ports, where

they had to pay royal and municipal duties. According to historical records

presented by Walton (1810), duties on entry were equivalent to 9.5 percent for

Spanish goods. Foreign goods had higher duties: they paid 15 percent when

arriving in Spain, 10 percent for being re-shipped and 7 percent as royal duty on

entry, “besides municipal and other duties, which altogether amount to about 45

per cent” (Walton, 1810, p. 161). Export goods from the colonies, in turn, also

had different customs treatment depending on the importing European country.4

Finally, trade between the colonies was severely restricted during most of the

colonial period. For example, starting in 1593 only Acapulco would receive the

Manila Galleon from the Philippines and its goods were not to be distributed

elsewhere (e.g. Peru, Panama, Guatemala, etc.). Merchants from other colonies

would have to use intermediaries (Mexican merchants) to be able to sell and

obtain Asian goods to supply their colonies. Not surprisingly, merchants from

other colonies would end up arriving in Acapulco, trading with the galleon, and

using routes destined to other goods (e.g. Cacao) to illegally transport Asian

goods to Guatemala and beyond, despite the explicit prohibition of doing so

(Yuste 2012: 216).

4Llama, vicuna and sheep’s wools were, for example, duty-free if they were sent to Spain,whereas they bore heavy taxes when shipped to a foreign country (Walton, 1810).

8

All major aspects of trade were regulated by the House of Trade (Casa de la

Contratacion), which was first established in Seville in 1503, and then moved to

Cadiz in 1717. Trade, navigation and migration licenses to America had to be

requested there and all ships were to be rigorously inspected by Spanish officials

upon returning to Spain (Hamilton, 1948).

2.2 Contraband trade

The natural consequence of strict trade regulation was the emergence of a highly

lucrative contraband trade in which French, British, Dutch and even Spanish

officials would participate in. According to the British naval commander Sir

John Narborough “. . . the inhabitants of Chile had silver buckles to their belts

and golden hilts to their swords but lacked the commonest of European man-

ufactures” (Sir John Narborough’s Voyage to the South Sea: 85-87, cited by

Christelow (1942: 311)), thus highlighting the numerous opportunities for those

willing to engage in this business.

Highly visible pirate attacks on Mexican ports (Francis Drake, John Hawkins,

Lorenz de Graaf, among others) have long-captured the imaginations of many

writer’s and historians alike. For instance, the widely publicized theft of Moztecuma’s

treasure sent by Hernan Cortes in 1522 to King Carlos V of Spain by French pi-

rates (Juan Florin). The most prevalent and “expensive” problem for the colonial

government at the time was smuggling (comercio ilicito). However, the distinc-

tion between piracy and smuggling is often blurred. Pirates and smugglers were

often the same person, or smugglers would rely on coercion and intimidation to

facilitated trade. For example, in 1567 in Riohacha (Colombia) the known pirate

John Hawkins recalls trading with the population at nighttime while bombard-

ing Spanish military positions during the day (De Ita Rubio 2012: 184).

As mentioned, Spanish customs tariffs, quantity restrictions and temporal

constraints were largely responsible for extremely high prices of imported goods.

Foreign traders could not only offer goods at much lower prices if avoiding the

legal course through Spain, but they could obtain a much higher profit rate,

equivalent to that of the Spanish exporter in Cadiz (Walton, 1810). Therefore,

as reported by Brown (1926), English traders never had difficulties in selling

their goods and were even able to sell on credit. Conversely, Mexican producers

were also more willing to trade with foreigners than to send their products back

9

to Spain. For example, in California (now part of the US) foreigners were willing

to pay more for local goods such as pearls than if they were sent back to Spain

(Trejo Barajas 2012: 280).

Goods smuggled varied by region. For instance, in the Caribbean and Gulf of

Mexico most of the goods smuggled involved slaves and manufactures. Northeast

Mexico and the Californias exchanged silver, gold and pearls for manufactures,

mostly textiles (Trejo Barajas 2012: 280). However, the Spanish Inquisition in

Mexico was also worried about the potential impact of foreign ideas and beliefs

brought by pirates and smugglers, particularly from Reformist countries (De Ita

Rubio 2012: 190).

The considerable extent of smuggling during the Spanish colonial period is

estimated to be sizeable but it is not exactly known for obvious reasons.5 Yet,

there is indirect evidence that foreign goods coming to Spanish colonies, both

legal and contraband, exceeded by a large amount Spanish goods. For instance,

Yuste (2012: 223) finds rather surprising that merchants from Guadalajara were

practically absent from the Acapulco trade fairs. The author suggests that since

the Manila Galleon ran parallel to the Mexican west coast prior to reaching Aca-

pulco these merchants had plenty of opportunities to get close to the galleons in

smaller ships and clandestinely purchase its goods. More dramatically, Jose de

Galvez (royal envoy to reform the colonial government in 1765) noted how all

officials supposed to safeguard the royal interest in Acapulco have contributed

to illegal trade “in every imaginable way” (AGI Mexico 1248 cited by Pinzon

Rios 2012: 248).

Contraband trade was also greatly facilitated by the role played by foreign

actors. Both France and England promoted and directly financed pirate ex-

peditions to intercept Spanish galleons carrying gold or took advantage of the

undersupplied colonial consumers by providing British or French manufactures.

The presence of British colonies in the Caribbean served as a base for contraband

ships to reach the shores of Spanish colonies in the mainland. Boats loaded with

contraband goods would follow licensed vessels until these have consumed their

supplies, so that smuggled goods could then be transferred. English warships

could also escort illegal vessels until they were safe, where it was customary

that captains of such warships received a percentage of the profits of contra-

5See, among others, Brown(1926), Brown(1928), Nettels(1931), Goebel(1938) and Chris-telow(1942).

10

band trade. Although British law constantly sought to foster and legalize trade

between the British West Indies and the Spanish colonies, such attempts were

ultimately unsuccessful. Historical accounts suggest that the large contraband

trade carried-out with the aid of these British colonies during the first half of the

18th century was useful in undermining the Spanish monopoly (Goebel, 1938).

Wars in Europe also increased the value of contraband trade and provided

further incentives to foreign merchants to engage in it. For instance, during the

war between England and Spain in 1796 and the English blockade, trade was

closed between Seville and the colonies, therefore, smuggling became even more

necessary in order to secure metals and essential commodities for the population

in the colonies. In addition, until the end of the Napoleonic Wars, communi-

cation and trade between Spain and its colonies was also frequently disrupted,

which the British exploited by meeting the material needs of the colonial pop-

ulation (Goebel, 1938). Finally, during the war of Independence (1810-1821),

lack of land routes to safely transport goods privileged to use of maritime ones,

dominated by smugglers (Trejo Barajas 2012: 289).

The Spanish Crown was well aware of these contraband activities and sought

to counteract them: first, by channeling trade through a reduced number of

ports in order to facilitate the control of goods’ flows and the enforcement of tax

payment. Second, the Spanish government also conducted random searches of

foreign vessels in the Caribbean, and maintained the presence of a coastguard or

guarda costas at all times in the region (Hamilton, 1948; Goebel, 1938). Despite

such efforts, contraband trade was a lucrative business in the Americas during

the whole colonial period of restrictive trade and even when trade was increas-

ingly freed under Bourbon rule although never fully implemented.

2.3 New Spain’s Ports

Despite the vast Mexican coastline, Veraruz in the Gulf of Mexico and Aca-

pulco in the Pacific were the unique points of entry for Spanish merchandise.

Campeche, close to the Yucatan peninsula, would join in the late 18th century

(1770). These three ports were the only ones fortified and built to withstand

multiple attacks to the city and defend merchant boats stationed there or in the

vicinity.

Not only ports were limited, but coastal settlements were discouraged alto-

11

gether during colonial times. Early on in the colonial period (1543), Philip II

approved the “Orders for the discovery, population and pacification [of new ter-

ritory]” (Ordenanzas de descubrimiento, nueva poblacion y pacificacion) which

dictated how the colonies ought to be populated. Article 41 established to not

choose coastal towns for settlement due to the presence of pirates (corsairs),

the lack of suitable land for cultivation, and the disease environment. The goal

should be to establish the minimal ports necessary for the entry, commerce and

defense (De Ita Rubio 2012: 203). Yet, this early depopulation policy in the

coastal areas did not put an end to piracy, since deserted coasts were left ex-

posed and even facilitated contraband activities (Gerhard, 1993). Rather, its

main effect was to contribute to the inland concentration of population which

persists until today.

Figure 2: Population Density in 2000

Source: http://geografia.laguia2000.com/geografia-de-la-poblacion/mexico-poblacion

This pattern of not settling in the coast even resisted explicit attempts to

populate the coastline. For instance, in the 16th century, Nuno de Guzman

founded four villas in the western coast of Mexico which were later abandoned

due to a lack of supplies (Olveda Legaspi 2012: 232-233). The same occurred

with a number of other natural harbors found in the Mexican west coast, which

were never effectively enabled to host commercial activities. Rather, these har-

bors were used as point of departure for expeditions to explore the Californias,

hosted small military units, or were used by the Manila galleon as a stop for

provisions (Olveda Legaspi 2012: 238-239). For example, the port of San Blas

in Nayarit served as a military post and cargo distribution. The overall lack of

ports linking Mexican regions to international trade proved a handicap to mar-

12

itime power after independence despite its maritime importance during colonial

times.

2.3.1 Veracruz, Acapulco and Campeche

The most important colonial port was that of Veracruz, which held the monopoly

of shipments going to and from Spain for three hundred years. To illustrate the

magnitude of its importance, between 1540 to 1650, Veracruz controlled 85% of

the volume of exports from the Americas (including Peru) (Chaunu 1960: 522).

Even today, it is an important commercial port in the region. The municipality

of Veracruz was the first one founded in continental America (circa 1519), even

before the conquest of Mexico was completed (1521). This port, together with

that of Campeche, were the most exposed to pirate activity due to its direct

access to vessels coming from Europe as well as to the numerous islands of the

Caribbean, where a number of pirates found shelter. Figure 3 below shows the

routes used by John Hawkins, a British naval commander, to smuggle goods to

the colonies and traffic with African slaves in the Caribbean-Veracruz area in

the 17th century.

Figure 3: Pirate Routes: John Hawkins

Source: De Ita Rubio (2012: 179) from Lombardi (1983:42).

13

The second most important port, Acapulco, was designated the exclusive

point of exchange from the Americas to the Spanish colonies in Asia (Gerhard,

1993) due to its privileged geography and closeness to Mexico City (Yuste, 1992:

101; Miranda, 1994: 29). Such assignment occurred around the mid 16th cen-

tury and remained in place until the end of the colonial period.6 Trade volumes

along the Pacific were never as high as those involving the Gulf of Mexico and

the Atlantic, yet, it did lead to certain economic dynamism in the region (Yuste

2012: 210).

Figure 4 below shows the two officially sanctioned trade routes from Spain

to Veracruz, by land to Acapulco, from where they would ship to and from the

Philippines in Asia.

Figure 4: Official Trade Routes

Source: De Ita Rubio (2012: 167) from Lombardi (1983: 35).

Finally, Campeche was the third colonial port mainly devoted to the export

of goods from the Yucatan Peninsula abroad. Due to its location, it was also

frequently “visited” by pirates, particularly in the 17th century. However, con-

traband trade carried out by pirates and professional smugglers remained an

important concern during most of the colonial period, and it blossomed in the

6Guatulco, on the Pacific, was a main Spanish port at the beginning of the colonial period,however, Acapulco took its place in 1573. Guatulco bay, as many others, continued to be usedfor smuggling activities (Gerhard, 1993).

14

mid 18th century just prior to independence.

During the late colonial years, trade was slowly liberalized. In 1770 the port

of Campeche opened to trade with Spain; in 1774 ports of New Spain, New

Granada (roughly Colombia and Venezuela) and Peru were opened for inter-

colony trade; finally, in 1789 New Spain opened to trade with non-Spanish com-

panies. It is during this period that a number of ports saw greater dynamism.

Yet, this will prove short-lived due to the English blockade and re-imposition of

some restrictions. After independence in 1821, the country entered a period of

high political instability, during which colonial ports were recurrently seized by

one insurgent group or another as a way to collect taxes on incoming merchan-

dise and finance war activities (Miranda 1994: 34). Undoubtedly, these events

severely hampered their functioning throughout much of the 19th century, thus

undermining the commercial monopoly and importance of Acapulco in the Pa-

cific and in Veracruz, in the Gulf of Mexico. Although a number of other ports

would gain prominence during this period Mexico in general would lose impor-

tance against other ports such as New York, Buenos Aires and Montevideo (De

Ita Rubio 2012: 163).

3 The Data

Data for this paper comes from several sources. In terms of the contemporane-

ous outcomes of interest, we use different measures of public good provision, tax

collection and poverty at the municipal level in Mexico. There are 2456 Mex-

ican municipalities, distributed along 32 states; 17 of which are coastal states

involving 1535 municipalities. Measures of municipal poverty and percentage of

the population lacking basic utilities in 2010 come from CONEVAL (Consejo

Nacional de Evaluacion de la Polıtica de Desarrollo Social)7, which tracks the

performance of social policies across Mexico. In addition, measures on the av-

erage tax collection (municipal tax income) per capita in 1995-2010, the length

of roads as a share of municipal surface, and the number of agents at the Public

Prosecution Office per 100 thousand inhabitants in 2010 are provided by INEGI

(Instituto Nacional de Estadıstica y Geografıa)8.

The key explanatory variables are indicators capturing whether trade in a

7http://www.coneval.gob.mx8http://www.inegi.org.mx/

15

given place was conducted under Spanish institutions or based on informal smug-

gling arrangements. To code Spanish presence we use historical sources of the

main maritime ports during colonial times in New Spain (now Mexico). These

locations are reported by Gerhardt (1993), from which we also code the distribu-

tion of Spanish colonial towns in general to measure the importance and length

of colonial presence. In addition, we identify those places in which contraband

trade was rampant due to the presence of professional smugglers or pirates. The

location of these ports is coded from historical narratives of the presence of pi-

rates on both coasts of Mexico. On the Pacific side, detailed accounts on the

presence of piracy are provided by Gerhardt (1990) which covers the 16th cen-

tury until the late 18th century. In the Caribbean –Gulf of Mexico- the main

sources come from regional histories (Alsedo y Herrera (1883); Munoz (2007,

2004)).

As a result, we identify 34 main ports or areas in which goods where ex-

changed during colonial times either legally, as in the royal ports of Acapulco,

Campeche and Veracruz, or illegally via non-official ports (e.g. Banderas Bay or

Bahia de Banderas, now close to Puerto Vallarta). Although there is also evi-

dence of pirates’ presence in royal ports, these will be considered to be Spanish-

treated (and not treated by pirates), given the relative prevalence of Spanish

state institutions in these places. A visual representation of the main treated ar-

eas is provided in Figure 1, which portrays the regional distribution of all known

points of entry of merchant goods (legal or not).

It is important for our empirical strategy to compare treated ports with places

that are most similar in a number of observed and unobserved covariates. Since

places more similar to a given port are its neighbors, we identify municipalities

in the vicinity, namely, those that fall within a radius of 100, 50 or 20 kilometers

from each treated port. These neighboring regions, and the municipalities they

encompass, are shown in figures 5 and 6.

16

Figure 5: Vicinities around treated ports

Figure 6: Neighboring municipalities

Aside from historical sources of pirate activity and official colonial ports, we

separately identify the universe of natural harbors along Mexican coastlines as

an exogenous measure of the possibility to trade. We determine the location of

natural harbors by the presence of water inlets, bays, estuaries or river mouths

on the coastline. Following this approach, pioneered by Jha (2013),9 we identify

226 natural harbors for all of Mexico, which could have plausibly provided nat-

ural protection to mercantile activities. These harbors are distributed along 82

9Our procedure is slightly different since Jha (2013) relies on all natural indentations orwater bodies within 10 kilometers of the coastline as potential medieval harbors, whereas werequire that water bodies are connected with the sea.

17

municipalities (out of 152 coastal municipalities), and they constitute our set of

“all natural harbors”.

Additionally, following Gaikwad (2015), we place restrictions on the suit-

ability of harbors based on the relative elevation of the surrounding territory.

Mountainous topography around harbors, more than any other feature necessary

in modern times10 to safely navigate harbors, was necessary to store ships as it

provided shelter from winds and bad weather (Gaikwad, 2015). Hence, we define

a subset of ‘protected natural harbors’ as follows: for each detected natural har-

bor we calculate the mean terrain elevation within 10 kilometers radial distance

from the coastline. If elevation is above the 30th percentile of elevation among

all natural harbors, this place is considered a ‘protected natural harbor’ in our

main analyses. We further consider harbors with elevation above the median in

the Appendix to verify our results. Figures 7 and 8 show the distribution of our

set of protected natural harbors (those with elevation above the 30th percentile)

which are present along 51 municipalities. If we only consider harbors surround-

ing elevation above the median, the number of municipalities drops to 26.

Figure 7: Harbors above 30th pct elevation

10Larger ships increased requirements for the suitability of ports.

18

Figure 8: Harbors above median elevation

We also code the presence of current maritime ports in Mexico. This informa-

tion is obtained from the Mexican state office for communications and transport

–SCT (Secretarıa de Comunicaciones y Transportes). Current maritime ports

are distributed along 71 municipalities, 22 of which were also treated in the colo-

nial period.

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the different variables mentioned

in this section for municipalities in coastal states under the two different treat-

ment status.11

[Table 1 here]

Finally, we further look at within municipality outcomes, namely, develop-

ment measures at the locality level. Data comes from the 2010 census which

collects information for locations, defined as settlements of up to 30,000 people.

We identify all localities within a radius of 30 kms of natural harbors that still

belongs to the municipality and created an average of the shareof population

with access to basic assets (radio, tv, fridge, washing machine, car, computer,

telephones, cell-phones or internet); we also examine access to sewage, water,

quality of household floor, and electricity, as well as the illiteracy rate in the

population.

11Table A1 in the Appendix reports descriptive statistics for municipalities directly on thecoastline (panel A) and for all Mexican municipalities (panel B).

19

4 Empirical Strategy

Overseas trade in colonial Mexico was either legally conducted under colonial

rule, or via extra-legal means by pirates.12 The underlying institutions estab-

lished under these two scenarios implied markedly different degrees of state ca-

pacity, compliance with the law, and thus a different market structure and social

organization around trade. Because of the importance of this economic activity

during the colonial period in places used as legal ports, and the length of the

presence of state institutions, we expect that those places with trade and higher

state capacity do better in the long-run than those that could have conducted

trade but did not. This hypothesis is consistent with previous findings in the

literature (Jia 2013; Gaikwad 2013; Fujita and Mori 1996). Yet, the effect for

pirate ports is ambiguous a priori: informality and illegality often undermine

sustained growth due to legal uncertainty. Yet, smuggling may also provide the

“spark” (e.g. initial investment) for sustained development following an increas-

ing returns mechanism (Krugman 1991).

Estimating the different treatment effects is not straightforward, since it is

likely that these ports were not chosen at random and are therefore not compa-

rable with other coastal places. Several pre-conquest or pre-treatment character-

istics affecting future development might have explained the selection of these

places as trade ports. Proximity to native labor force and natural resources

may have, for instance, acted as such driving forces. As a result, estimation of

the treatment effect is only possible among places sharing similar pre-treatment

characteristics.

4.1 Linear model with vicinity fixed effects

Our first strategy to allow for this quasi-experimental setting is to compare

municipalities in close vicinity. Their proximity guarantees that a number of

observable and unobservable factors will be common to treated and control ar-

eas. For each treated municipality we find its close neighbors within different

radii of geodetic distances, namely 20, 50 and 100 km.13 We then introduce

vicinity fixed effects at a given distance, to compare each treated municipality

12Although we are aware that corruption also existed in official ports, as a matter of degree,pirate-ports were completely devoted to this activity.

13Our procedure provides at least one closest neighbor for each treated municipality regardlessof its radius of distance.

20

with its neighbors.14 Neighboring municipalities in Mexico do not only share

pre-treatment conditions as population and geographic features, but they still

share today cultural traits, federal laws and institutions, labor markets, disease

environment, among other factors. The idea of having several distances is to

observe the sensitivity of our estimates to neighboring areas of different sizes,

where smaller vicinities have arguably more common factors. Our baseline model

is given by:

Yij = ηj + β Spanish portij + γ P irate portij + θ colonial townij + εij (1)

where Yij is an outcome variable for municipality i in vicinity j, ηj is a fixed

effect for vicinity j, and colonial town takes the value of 1 if municipality i was a

town in the colonial period thus capturing municipality-specific features related

to the size of settlements and their history, in particular, whether it enjoyed

the presence of a local state. This variable controls for potential agglomeration

effects whereby those places early established will continue to be prominent over

time. As outcome variables we consider the mean municipality tax income per

capita between 1995 and 2010, and for year 2010, the share of poor individuals,

share of people lacking basic utilities, ratio of the length of roads network over

municipal surface and number of agents at the Public Prosecution Office for each

100 thousand inhabitants.

4.2 Natural harbors approach

Even after controlling for common features at the vicinity level, being a pirate or

Spanish treated port could be related to municipality-specific unobservable traits

that might explain later outcomes. Our second strategy deals with this concern

by using a source of exogenous variation in the possibility to trade, namely, the

presence of a natural harbor.

Until the mid-19th century, navigation in maritime ports depended on the

availability of natural harbors. These were places able to provide shelter and

safe anchorage for ships and vessels. Natural harbors were then key for carrying

out trade by allowing the loading and unloading of goods. This exogenous con-

14Treated municipalities that are neighbors within 20 km distance have perfectly or almostperfectly overlapping vicinities; in these cases, a single fixed effect is defined.

21

dition for trade has been already used in other studies for other purposes. Jha

(2013) relies on natural indentations or water bodies along the coastline, whereas

Gaikwad (2015) focuses on natural indentations protected by mountainous to-

pography in their surroundings. We use these two approaches in order to define

our set of natural harbors, as well as a subset of protected natural harbors.15

Whether a municipality contains a natural harbor is thus an exogenous condi-

tion for the presence of historical trade, which significantly restricts the number

of treated municipalities.16 We argue that the presence of a natural harbor in-

duced the selection of a given place by its clear geographical advantages, which

are either unrelated to future development, or common to all natural harbors

(e.g. the possibility of maritime trade in the colonial period).17 Therefore, we

compare the restricted set of treated municipalities with all other natural-harbor

municipalities along Mexican coastlines that had the same likelihood of being

chosen. In other words, among natural harbors in the vicinity, the choice of any

given one can be considered as-if random.

In a baseline exercise, we estimate the following model among municipalities

with the presence of a natural harbor:

Yh = α+ β Spanish porth + γ P irate porth + θ colonial townh + εh (2)

Finally, as mentioned above, we consider the sample of natural-harbor (or

protected-natural-harbor) municipalities under our initial approach. That is:

Yhj = ηj + β Spanish porthj + γ P irate porthj + θ colonial townhj + εhj (3)

where h denotes a natural-harbor (or protected-natural-harbor) municipality

and j denotes its vicinity.

15See definition criteria in the previous section of the data.16Treated municipalities are now 19, or 14 with the presence of a protected natural harbor,

out of 34 in the original sample.17It can be safely claimed that natural harbors influenced trade since the colonial period, and

not just thereafter. In particular, the introduction of steamships in the 19th century increasedthe size of vessels, which required port structures and greater depth in already active harbors.This infrastructure was also increasingly built at other coastal places (not natural harbors),which made them suitable for trade.

22

5 Results and robustness checks

Estimates of model (1) are shown in Table 2 including all Mexican municipalities,

and in Table 3 including only municipalities in coastal states. The three panels

in each table correspond to different sizes of vicinities around treated places,

which determine vicinity fixed effects in each case (within 100 km, 50 km or 20

km distance). We find robust evidence that the presence of Spanish and pirate

ports is related to better development outcomes in the long run (except for the

length of roads explained by piracy trade). In particular, coefficients for both

treatments are statistically significant and related to less poverty, greater access

to basic utilities and higher municipal tax income per capita when comparing

neighboring municipalities located at different distances (20,50 or 100 kilome-

ters).

Estimates from a restricted sample of municipalities in coastal states, consid-

ering variation within a 100 km radius (Panel A in Table 3), indicate that being

a Spanish colonial port (pirate port) is significantly related to a 23.17 (11.83)

percentage points lower share of poor individuals, to a 21.34 (15.93) percent-

age points lower share of population lacking basic utilities and to a 0.17 (0.12)

thousand Mexican pesos higher tax income per capita. The magnitude of these

effects are important, equivalent to 1.3 (0.66), 0.71 (0.53) and 1.45 (1.03) stan-

dard deviations of their respective dependent variables.

Both treatments are in general associated with a greater number of agents

at the Public Prosecution Office per 100 thousand inhabitants, although this

relationship is not significant. On the other hand, the presence of a pirate port

is associated with a lower availability of road infrastructure while a Spanish port

has the opposite relation, and this result is robust to the different vicinity sizes.

[Table 2 here]

[Table 3 here]

Results for the baseline exercise among natural harbors are reported in Table

4. The first panel in the table restricts our original sample to all identified natural

harbors along Mexican coasts, whereas the second panel only considers natural

harbors protected by a mountainous topography. Estimates of the treatments

are similar across panels and to those in previous tables, although piracy is no

longer significant to explain higher tax collection per capita. It is interesting to

note that colonial towns among natural harbors, after controlling for the ports

23

treatments, are on average significantly worse off in terms of poverty measures

and tax income. Only road infrastructure seems to be positively related to the

fact of being a town in the colonial period. This suggests that results are not

merely driven by the length of Spanish presence, or the early presence of the

state.

[Table 4 here]

Table 5 further includes vicinity fixed effects at a 100 km radius from each

treated natural harbor.18 Results lead to the same conclusions as before: Spanish

and pirate harbors in the colonial period are today relatively richer, have better

access to basic utilities and a larger municipal taxing capacity. Royal harbors

display a greater presence of the state, whereas current road infrastructure is on

average lower in former pirate harbors.19

One difference is worth noting in this exercise. Whereas the significance

of the coefficients is robust in almost all cases, magnitudes relating to poverty

measures are now smaller, and this drop is particularly clear for the Spanish

treatment effect. This suggests an upward bias in our initial estimates with

all municipalities in coastal states (or all Mexican municipalities), which was

corrected by limiting the comparison between treatment and control group to

close-neighboring natural harbors that had arguably the same likelihood to be

chosen.20 This potential bias would be consistent with the intuition that Spanish

colonizers, acting under the colonial state guarantee, could choose the best places

for carrying out trade. On the other hand, pirates, who were performing an illegal

and hidden activity, were less able to choose, and their selection for trading ports

was more likely random.

[Table 5 here]

In the following section we seek to understand these findings by discussing

relevant channels or direct consequences of the two treatments.

18For some 50 km vicinities there is no variation or even no neighboring harbors. Estimatesusing this vicinity size support results explained here, and they are presented in the Appendix(Table A2, panels A and B), despite the fact that the presence of many treated harbors will becaptured by the vicinity fixed effects.

19Table A3 in the Appendix uses elevation above the median of all harbors as criterion fordefining protected natural harbors.

20Magnitudes of the Spanish treatment effect are still important. In the most conservativeestimates, this effect is between 0.54 and 1.3 standard deviations of the dependent variables.

24

State Capacity, Increasing Returns and Trade.

Clearly, the experience of smuggling during colonial times is positively as-

sociated with development outcomes today. This effect cannot be explained by

simple geographical traits or the length of colonial presence. Moreover, this re-

sult runs against conventional wisdom: places lacking state presence and with

established “criminal” activities are rarely a paragon of development. The key

question then is: why these ports became relatively more developed than similar

ones that did not host these trade activities?

A priori there are two main reasons. First, it is possible that smuggling led

to permanent settlements and the steady rise of an incipient merchant class and

petit-bourgeoisie promoting development. Yet, numerous accounts coincide that

most coastal areas (particularly in the Mexican West) were sparsely populated

throughout the 18th century and smuggling constituted a sporadic event bring-

ing together merchants, smugglers and local suppliers (for example, when foreign

vessels or the Manila galleon appeared). Olveda Legaspi (2012: 238) describes

how Matanchen and Chacala (ports in the Pacific coast) had a “floating popu-

lation” sustained by sporadic trade. Moreover, it appears that during colonial

times trade restrictions and the lack of roads connecting ports with inland towns

made it very difficult to capitalize on illegal trade then (but not later). Thus

suggesting that the benefits from trade appeared “later” in the colonial period.

The second possibility suggested by our findings is that the presence of smug-

gling during colonial times may have created the necessary conditions to benefit

after trade was liberalized in the late 18th century (comercio libre) as part of

the Bourbon Reforms and after independence (1821). This process started in

1770 by opening Campeche to trade with Spain and continued until 1789 when

other European powers were able to trade with all ports in New Spain (now

Mexico).21 Routes already used for smuggling, such as those bringing (illegal)

Cacao from Guayaquil to Acapulco blossomed when such restrictions were lifted.

In the case of Acapulco, trade was no longer limited to the periodical arrival of

the Manila galleon leading to more permanent settlements (Pinzon Rios 2012:

249). Other ports, such as San Blas, used as a maintenance stop and military

ward, also became an “indispensable stop” in the Mexican northwest after trade

liberalization (Pinzon Rios 2012: 269). Similarly, Mazatlan and Guaymas blos-

21This disposition actually lasted until 1796 when the English blockade interrupted all formsof trade with the colonies and restrictions were reinstated.

25

somed after independence in the early 19th century (Olveda Legaspi 2012: 244),

precisely the ports where American merchants have engaged in illegal trade with

Durango’s and Chihuahua’s merchants (Trejo Barajas 2012: 280). Presidios and

others forts located in the Californias and northern Mexico thrived commercially

in the late 18th century due to the presence of “merchant boats, foreign smug-

glers and their own demands” (Trejo Barajas 2012: 278).

The underlying mechanism we find more convincing is one of increasing re-

turns (Krugman 1991), whereby initial investments, in this case “know-how” or

the experience of clandestine networks, leads to an initial advantage in the busi-

ness once trade restrictions were lifted. This initial advantage also comes from

the fact that smuggling brought about efficiency gains from free trade relative to

the Spanish monopoly: larger volumes of trade at lower cost fostered consump-

tion, an incipient merchant class, as well as the networks and knowledge which

may have offset the lack of state capacity, law and order. Such developmental

advantage might have persisted even after trade stopped being the main eco-

nomic activity in Mexico more generally22 and in those places in particular. For

instance, during the 19th century colonial trade suffered heavily at the hands of

different insurgent factions.

It is important to note, however, that the magnitude of the effect of pirate

ports on development is always smaller than that of Spanish presence. In all

tables we report the p-values from a test of the equality of the coefficients un-

der both treatments. Results generally indicate a significant lower magnitude of

the piracy treatment effect relative to the Spanish effect in the general sample.

Among natural harbors this difference is not so clear, although point estimates

are in general smaller for the piracy treatment. This lower effect is consistent

with the idea that pirate ports have established slightly more unfavorable con-

ditions for the development of state institutions in comparison to Spanish ports.

Yet, piracy still had a developmental advantage over those natural harbors that

did not experienced trade.

This is evident considering results for some of our outcome variables: the

presence of piracy is negatively related to some state presence outcomes as road

infrastructure and number of agents at the Public Prosecution Office relative

to population, for which the presence of a Spanish port is positively associated.

22Today, Mexico is not a maritime power with only a few ships and a limited number of ports(De Ita Rubio 2012:163)

26

Thus, whereas the presence of piracy may have led to less poverty, state pres-

ence outcomes are not so clearly benefited. For instance, in the case of roads

– a long-term investment – these differences are most likely driven by the fact

that the colonial government early on invested in roads linking Veracruz, Mexico

City and Acapulco. Yet, roads linking major cities such as Guadalajara, Tepic

or other Gulf cities to the coast will still be lacking for a number of years making

inland communications difficult.

5.1 Robustness checks

Current trade

An alternative explanation for our findings is that the effect we see today is

merely because historical (legal or illegal) ports also conduct trade in the present.

If this is the case, then we should see that among current ports in Mexico – that is,

open to maritime trade – there should be no effect of smuggling or legal colonial

trade on current development outcomes. We then cross-check our estimates

by restricting the sample to present port municipalities in Mexico. Results for

model (1) among maritime ports today are shown in Table 6. Conclusions remain

robust: those ports with a colonial history of trade of any kind are significantly

better off today, and the effect of Spanish trade is even larger.23

[Table 6 here]

This exercise provides further insights on the mechanisms operating in the

long run. It can now be claimed that the positive effects of Spanish and pirates’

ports are not driven by the fact that many of these places carry out trade today.

Hence, supporting the idea that other mechanisms are at play, arising probably

from the early history of these ports – such as the presence of early ”know-how”

and smuggling networks.

Correcting for a potential measurement error in smuggling

Although historical records are very detailed in the location of piracy in New

Spain, we might be concerned that these records are not exhaustive, given the

illegal and hidden character of this activity.

23See Panel C in Table A2 for vicinity fixed effects within 50 km.

27

In order to correct for this potential measurement error, we employ an IV

strategy relying on the presence of a protected natural harbor as an instrument

for current trade. As previously discussed, geographical features of natural har-

bors provided necessary conditions for trade, allowing the entrance, shelter and

storage of ships. These features were of particular importance five centuries ago,

when sophisticated port infrastructure was not available, and part of it was not

even needed due to the smaller size and tonnage of ships.

Our assumption is that the particular combination of geographical features

making a natural harbor are not related to any factor determining development

today, except for the possibility in the past to access continental places from the

sea and the ability to exchange. Therefore, natural harbors should have affected

current outcomes only through their effect on historical trade carried-out by ves-

sels who found it suitable prior to the maritime revolution.24

In order to properly predict the piracy treatment with the presence of a

protected natural harbor, we exclude Spanish royal ports from the first stage.25

IV estimates are presented in Table 7. The first stage is reported for each sample

size (which slightly varies across dependent variables) in columns (1), (4), (6)

and (8), and we can verify that the presence of a protected natural harbor is a

strong predictor of piracy ports. IV estimates lead to the same conclusions as

before, except for the relative magnitude of the piracy treatment effect. It is

now larger than the effect of the presence of a Spanish port.

[Table 7 here]

These results further support the importance of having access to free trade

in the past. The consequences of this trade are, according to these estimates,

even bigger than those from trade under the control of state institutions which

fostered a monopolistic market structure.

Locality level (within municipality) outcomes

One final concern is that by looking at municipality aggregate outcomes

(e.g. the average across the whole municipality), findings may be driven by

24We are not aware of any reported evidence of arrival of large sized ships and vessels inMexico before the colonial period.

25A protected natural harbor will then only predict the presence of trade in those harbors, forwhich the absence of royal ports is known; i.e. it will predict the presence of pirate commercialactivities.

28

municipality-wide factors unrelated to the presence of historical trade, or by ar-

eas that were not actually affected by historical trade but nonetheless belong to

the same municipality. To address this concern, we look at development patterns

within a municipality, namely outcomes at the locality or village level.

We consider the provision of public goods, household assets and education

in localities within a 30 kilometers radius of each harbor that still lie within the

municipality. Since these are directly in contact or in close proximity to the

harbor, it is easier to attribute the observed effects to the presence of trade, as

opposed to other municipality-wide events.

We then estimate the following model:

Ylh = α+ β harbor treatedlh + θ colonial townlh + φlh + εlh (4)

where Ylh is an outcome variable for locality l that is within a 30 km radius

of harbor h; harbor treated indicates whether the natural harbor close to locality

l had the presence of colonial trade or not; colonial town takes the value of 1

if locality l belongs to a municipality already established during colonial times;

and φ captures locality specific traits such as altitude.

Results are presented in Table 8 and they show that localities close to treated

harbors are less likely to lack household assets such as radio, fridge or television,

and less likely to lack sewage. Although we do not find significant differences in

education and electricity provision, the coefficients hold a negative sign suggest-

ing higher literacy levels and electricity coverage for treated localities. Finally

and rather surprisingly, households in localities close to treated harbors have,

on average, less access to potable water – although the strength of this statisti-

cal association is weak. In sum, using evidence at different levels of aggregation

(within municipalities) we are able to find some support for our previous findings.

[Table 8 here]

6 Conclusion

Despite extensive evidence on the long term impact of overseas trade, the role

of state institutions accompanying commercial activities has not been exten-

sively studied. This paper examines the long run effect on development of over-

seas trade in colonial Mexico, conducted under two institutional arrangements,

29

namely, Spanish rule and smugglers. We use historical records on the location of

piracy and Spanish ports in New Spain (now Mexico), identify natural harbors

along Mexican coasts as a source of exogenous variation in the possibility to

trade, and compare harbors in the close neighborhood.

We find that being a Spanish or pirate port in the colonial period significantly

led to better development outcomes in terms of poverty measures and municipal

taxing capacity today, which are not driven by the fact of carrying out trade in

the present. The positive piracy effect, although in some cases lower than the

Spanish, is interpreted as a strong support to the long term impact of trade,

whether it was developed legally or not. We further argue that free trade under-

lying piracy activities, as opposed to a trade monopoly under Spanish rule, may

have led to an important volume of traded goods and consumption, an incipi-

ent merchant class, as well as important networks and know-how which allowed

these places to capitalize on trade liberalization.

Piracy, although not classifiable as a formal colonial institution, was spread

throughout Spanish America and emerged as as a result of a rigid trade monopoly.

Therefore, this study contributes not only to the understanding of heterogeneous

legacies from colonial activities, but also to the knowledge of important long run

effects of de facto institutions. Future work will examine the inland impact of

smuggling in transportation networks and other distribution centers.

30

Bibliography

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., and Robinson, J. (2005). The Rise Of Eu-rope: Atlantic Trade, Institutional Change, And Economic Growth. AmericanEconomic Review, v95, 546-579.

Alsedo y Herrera, D. (1883). Piraterias y Agresiones de los Ingleses yde otros pueblos de Europa en la America Espanola, Zaragoza, Madrid.

Alvarez-Villa, D. (2016). Explaining Informality: Extractive States andthe Persistent Incentives for Being Lawless. Unpublished.

Banerjee, A. and Iyer, L. (2005). History, Institutions, and EconomicPerformance: The Legacy of Colonial Land Tenure Systems in India. AmericanEconomic Review, 95(4), pages 1190-1213.

Baum, C. F., Nichols, A., & Schaffer, M. E. (2010). Evaluating one-way and two-way cluster-robust covariance matrix estimates. In presentationmade for the 16th UK Stata User Group Meeting.

Berger, D. (2009). Taxes, institutions and local governance: evidencefrom a natural experiment in colonial Nigeria. Unpublished manuscript.

Bernecker, W. (1994). El debate acerca del comercio exterior mexicano enla primera mitad del siglo XIX: Comercio libre, proteccionismo, prohibicionismo?Anuario de Historia de America Latina 31(1): 155188.

Brown, V. L. (1926). The South Sea Company and contraband trade.The American Historical Review, 31(4), 662-678.

Brown, V. L. (1928). Contraband trade: A factor in the decline of Spain’sEmpire in America. The Hispanic American Historical Review, 8(2), 178-189.

Bruhn, M., and Gallego, F.A. (2012). Good, Bad, and Ugly Colo-nial Activities: Do They Matter for Economic Development? The Review ofEconomics and Statistics, 94(2): 433461.

Chaunu, P. (1960). Veracruz en la segunda mitad del siglo XVI y primeradel XVII. Historia Mexicana (Apr.-Jun.) 9(4):521-557.

Depetris-Chauvin, P. (2014). State History and Contemporary Conflict:Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. Mimeo.

Christelow, A. (1942). Contraband trade between Jamaica and the Span-ish Main, and the Three Port Act of 1766. The Hispanic American HistoricalReview, 22(2), 309-343.

Cuenca-Esteban, J. (1981). Statistics of Spain’s colonial trade, 1792-1820: Consular duties, cargo inventories, and balances of trade. Hispanic Amer-ican Historical Review, 381-428.

De Ita Rubio, L. (2012) “Pirateria, costas y puertos en America colonial yla organizacion del espacio novohispano” in De Ita Rubio, L. (coord.) Organiza-cion del Espacio en el Mexico Colonial: Puertos, Ciudades y Caminos. Morelia:Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolas de Hidalgo p. 163-207.

Del Valle Pavon, G. (2012) “Origenes de la centralidad comercial y fi-nanciera de la ciudad de Mexico” in De Ita Rubio, L. (coord.) Organizacion delEspacio en el Mexico Colonial: Puertos, Ciudades y Caminos. Morelia: Univer-sidad Michoacana de San Nicolas de Hidalgo p. 19-63.

31

Diaz-Cayeros, A., & Jha, S. (2014) Can Contract Failures Foster EthnicAssimilation? Evidence from Cochineal in Mexico. Unpublished.

Durand, R., & Vergne, J. (2013) The Pirate Organization: Lessons fromthe fringes of capitalism. Cambridge: Harvard Business Press.

Drelichman, M., & Voth, H. J. (2008). “Institutions and the resourcecurse in early modern Spain” in Institutions and Economic Performance, byElhanan Helpman (ed.) p.120-47.

Engerman, S. L. and Sokoloff, K. L. (1997). Factor Endowments,Institutions, and Differential Paths of Growth among New World Economies: AView from Economic Historians of the United States. In Haber, S., editor, HowLatin America Fell Behind. Stanford University Press.

Fujita, M., and Tomoya M. (1996). The role of ports in the making ofmajor cities: Self-agglomeration and hub-effect” Journal of Development Eco-nomics, 49(1): 93120.

Gaikwad, N. (2015). East India Companies and Long-Term EconomicChange in India. Unpublished.

Gerhard, P. (1990). Pirates of the Pacific 1575-1742. Glendale Calif.:A.H. Clark Co.

Gerhard, P. (1993). A guide to the historical geography of New Spain.Rev.ed., University of Oklahoma Press. 402 pp.

Goebel, D. B. (1938). British trade to the Spanish colonies, 1796-1823.The American Historical Review, 43(2), 288-320.

Greif, A. (1993). Contract enforceability and economic institutions inearly trade: The Maghribi traders’ coalition. The American economic review,525-548.

Guardado, J. (2015). Office-Selling, Corruption and Long-Term Develop-ment in Peru. Unpublished.

Hamilton, E. J. (1948). The role of monopoly in the overseas expansionand colonial trade of Europe before 1800. The American Economic Review,33-53.

Hersh, J., & Voth, H. J. (2009). Sweet diversity: Colonial goods andthe rise of European living standards after 1492. Available at SSRN 1443730.

Huillery, E. (2009). History matters: The long-term impact of colonialpublic investments in French West Africa. American Economic Journal: AppliedEconomics, 176-215.

Jha, S. (2013). Trade, institutions, and ethnic tolerance: Evidence fromSouth Asia. American Political Science Review, 107(04), 806-832.

Jia, R. (2014). The Legacies of Forced Freedom: China’s Treaty Ports.Review of Economics and Statistics, 4(96), 596-608.

Kleiman, E. (1976). Trade and the decline of colonialism. The EconomicJournal, 459-480.

Krugman, P. (1991).“Increasing Returns and Economic Geography” Jour-nal of Political Economy 9(3): 483-499.

Levy, S. (2007). Can Social Programs Reduce Productivity and Growth?A Hypothesis for Mexico. International Policy Center (IPC) - Working PaperSeries.

32

Lombardi, C. L. (1983). Latin American history: a teaching atlas (Vol.29). University of Wisconsin Press.

Maloney, W. F., & Valencia Caicedo, F. (2012). The persistence of(subnational) fortune: geography, agglomeration, and institutions in the newworld. Agglomeration, and Institutions in the New World (August 29, 2012).

Michalopoulos, S. and E. Papaionnau (2013).Pre-colonial Ethnic Insti-tutions and Contemporary African Development, Econometrica, 81(1): 113-152,

Munoz, L. (2007). El Golfo-Caribe, de limite a frontera de Mexico. His-toria Mexicana 57(2): 531-563.

(2004). Los puertos mexicanos del golfo durante los primerosanos del Mexico independiente: fuentes para su estudio. America Latina en laHistoria Economica 11(1): 59-78.

Naritomi, J., Soares, R. and Assuncao, J. (2012). Institutional Devel-opment and Colonial Heritage within Brazil. The Journal of Economic History,vol. 72(02), pages 393-422.

Nettels, C. (1931). England and the Spanish-American trade, 1680-1715.The Journal of Modern History, 3(1), 1-32.

Ogborn, M. (2012) “Making Connections: Port Geography and GlobalHistory” in De Ita Rubio, L. (coord.) Organizacion del Espacio en el MexicoColonial: Puertos, Ciudades y Caminos. Morelia: Universidad Michoacana deSan Nicolas de Hidalgo p. 19-63.

Pinzon Rios, G. (2012) “De Acapulco a San Blas: reestructuracion delos puertos del Pacifico novohispano durante el siglo XVIII” in De Ita Rubio,L. (coord.) Organizacion del Espacio en el Mexico Colonial: Puertos, Ciudadesy Caminos. Morelia: Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolas de Hidalgo p.245-273.

Olveda Legaspi, J. (2012) “Las villas y los puertos del Pacifico nortenovohispano” in De Ita Rubio, L. (coord.) Organizacion del Espacio en el MexicoColonial: Puertos, Ciudades y Caminos. Morelia: Universidad Michoacana deSan Nicolas de Hidalgo p. 229-245.

Suarez Arguello, C. (2012) “El Puerto de Veracruz ante un asalto pirata:mayo de 1683” in De Ita Rubio, L. (coord.) Organizacion del Espacio en el Mex-ico Colonial: Puertos, Ciudades y Caminos. Morelia: Universidad Michoacanade San Nicolas de Hidalgo p. 145-163.

Trejo Barajas, D. (2012) “Comercio maritimo y nacimiento de los puertosdel golfo de Baja California” in De Ita Rubio, L. (coord.) Organizacion del Espa-cio en el Mexico Colonial: Puertos, Ciudades y Caminos. Morelia: UniversidadMichoacana de San Nicolas de Hidalgo p. 273-305.

Walton, W. (1810). Present state of the Spanish colonies: including aparticular report of Hispanola, or the Spanish part of Santo Domingo; with ageneral survey of the settlements on the south continent of America (Vol. 2).Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown.

Yuste Lopez, C. (2012) “El eje transpacifico: la puerta novohispana alcomercio con Asia” in De Ita Rubio, L. (coord.) Organizacion del Espacio en elMexico Colonial: Puertos, Ciudades y Caminos. Morelia: Universidad Michoa-cana de San Nicolas de Hidalgo p. 207-229.

33

Tab

le1:

Desc

rip

tive

stati

stic

sfo

rm

un

icip

aliti

es

incoast

al

state

s

No

trea

ted

Spanis

hp

ort

Pir

ate

port

All

obs.

Obs

mea

nsd

Obs

mea