The GutHub: Designing Edible Interactions and Fermented Friendships A Proposal of Human – Computer – Bacteria Interaction Design Markéta Dolejšová Abstract The GutHub is a social platform for online - offline exchanges of fermentation starter cultures and knowledge related to the practice of fermentation. The GutHub interface features an open source repository of recipes operated at GitHub hosting service; a physical open access ‘bank’ of various starter cultures; and regular community meet-ups organized around it. The project is an experiment in HCI (human-computer interaction) performed beyond the anthropocentric limits, while promoting a technologically mediated human-to-bacteria interplay. The goal of the GutHub initiative is to test the usability of peer-to-peer collaboration and data crowdsourcing for the support of local DIY food production.

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

The GutHub: Designing Edible Interactions and Fermented Friendships

A Proposal of Human – Computer – Bacteria Interaction Design

Markéta Dolejšová

Abstract

The GutHub is a social platform for online - offline exchanges of fermentation starter cultures

and knowledge related to the practice of fermentation. The GutHub interface features an open

source repository of recipes operated at GitHub hosting service; a physical open access ‘bank’

of various starter cultures; and regular community meet-ups organized around it. The project is

an experiment in HCI (human-computer interaction) performed beyond the anthropocentric

limits, while promoting a technologically mediated human-to-bacteria interplay. The goal of the

GutHub initiative is to test the usability of peer-to-peer collaboration and data crowdsourcing for

the support of local DIY food production.

Introducing fermentation

I was born as an only child. I always thought that people will automatically think I am a little

spoiled brat. As my parents did not show any interest in doing that, I always wanted to grow a

little brother by myself. Thank goodness, I found out about fermentation!

Humans have used fermentation, a metabolic process that converts sugar to acids, gases,

and/or alcohol to produce food and beverages since Neolithic times (Klein, Lansing, Harley,

2006). Fizzy reactions of bacteria, fungi and other microbial cultures that produce the prickling

sour taste of delicacies such as kimchi, yogurt, kefir or cider are favored by humans of all

continents. Be it for medicinal purposes, taste indulgences, joy of tinkering or for budget

reasons; the coexistence of people and bacteria slowly fermenting each other is a symbiotic

one. These non-anthropocentric relationships are perpetuated over the hybrid interface

embodied first by the glass jar and the gentle movements of its lid (done by human hand, to

release the unwanted oxygen and let the ferment burp), and then by the human gut (pampered

by the good healing bacteria).

Moreover, most of the fermentation starter cultures (microbiological cultures which actually

perform the fermentation; often called simply as ‘starters’) need to be regularly fed by sugars or

complex carbohydrates in order to proliferate.

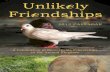

Kefir milk grains – a starter culture necessary for kefir fermentation. (Picture © Raw and Pure, n.d.).

Hence, it is a truly sweet, long-term bond, or even a form of human-bacteria love. No wonder

that some enthusiastic fermentation fans call their starters with cute names, proudly enouncing

that their “little Joey has grown a bit again last week” (PečemPecen, 2015). These symbiotic

trans-species collectives resemble the Latourian Parliament of things (Latour, 2005), the

cosmopolitical systems (Stengers, 2010), the structure of rhizome (Deleuze & Guattari, 1988),

or, as I will show later, the organic form of Thingiverse (an online service dedicated to the

sharing of user-created design prototypes).

An important aspect of fermentation is the self-propagating process of starter cultures‘ growth: If

you take good care of it, the culture will grow constantly and make your jar bottomless, such as

in the famous Czech fairy tail “Hrnečku vař!” (“Cook mug, cook!”). The starters are self-

reproducing organic commodities and the fermented delicacies therefore become abundant. If

their human partner invests enough care into it, the mutual hippie-ish relationship between

human and ferment can last forever. However, as most of the “little Joeys” suffer from (or are

rather gifted by) the hyperactivity disorder, the human caretakers welcome the option to share

them, and pass them to other fermentation fans. There is no place for conservative monogamy

within the hippie love.

Not only the starters, but the jars with ferments can too get their nicknames. These names also tell a lot about the ferment’s human caretaker. (Picture © GutHub, 2015).

But we are now more than five decades behind the 60s’ flower power, and even more decades

behind the Neolithic age. People are still sharing their fermentation starters on the

neighbourhood door-to-door basis. The urban lifestyle augmented by superfluous supply of

smartphones and wifi networks (such as the one you are likely to adopt in Singapore), however,

opens a brand new universe of ‘smarter ‘exchanges.

GutHub prototyping

Singapore has a great variety of shopping malls and supermarkets, as well as a dense online

infrastructure, but also a great lack of locally grown food. Sitting inside the airconned university

classroom accessible only through the chip-card secured doors, we started to crave for a taste

of hippie reality. We wanted to mitigate the cold pampering care of our Alma Mater, and even

more importantly, we wanted to eat sauerkraut. The decision to focus our Design for Public

Engagement class on fermentation issues, and designing of a local initiative formed around

them, was quickly agreed upon.

During the initial hands-on sessions and experiments with carrots, cauliflower, cucumbers,

cabbage, or yoghurt fermentation, we started to talk about the (trans)national food policy and its

possible DIY counterparts. The open source ethos of licence-free sharing and peer-to-peer

development of products design or blueprint (Lakhani & von Hippel, 2003) turned out to be quite

resonating with our fermentation plans. To design a sustainable interaction between humans

and ferments within the tech-savvy urban community, we decided to employ not only the open

source lingo, but also its ethics and strategies.

The discussions have opened some interesting questions to us: Can we utilize the existing local

infrastructure of human and nonhuman actors connected over the ubiquitous wifi signal, to

create a network for open source development of fermentation practice? How would the

principles of HCI design apply to a development of a local DIY food initiative? How would the

model of peer-to-peer economy work within the urbanized food market? Or, in other words, can

we connect microbes, binary code and human guts to create a new kind of urban trans-species

interactions? Trying to find the answers, we conducted some ethnographic research, as well as

several fermentation trials and design probes, and eventually came to a decision to start the

GutHub – an open source community of “human-bacteria hookups with no yeasts attached”.

Communities of fermentados

First, we conducted some nethnographic trips into several virtual communities of fermentation

fans. The most engaging was the field trip into the facebook forum of Czech community

PečemPecen (“We Bake Bread”) that focuses on sourdough fermentation.

We encountered huge portions of positive sentiments and emotional interactions there, both

among human members and humans and their leavens (starters used for bread making). The

users would enthusiastically share pictures of their beloved dough, as well as tips and

recommendations on its procurement (where to store it, for how long, which ingredients to add,

what temperature should be maintained etc.). Pictures of bread loaves shaped as hearts would

generate some 1000+ likes. The interesting habit adopted by this community are regular leaven-

swaps performed in local cafés or city parks: The fermentados meet, exchange their leavens,

discuss their experiences, and also informally chitchat about a variety of topics related (not

exclusively) to fermentation. The leavens connect them and motivate them to get out of their

apartments or offices, and interact with each other.

A beloved bread loaf. (Picture © PečemPecen, 2015).

The swaps are performed on a non-monetary basis, and the bread lovers would either

exchange one kind of leaven for another; ‘pay’ with a cup of coffee if they do not have a leaven

to share, or offer their starter for free. The leaven is an abundant commodity that seems to be

naturally designed for this form of gift- or barter-trade, and serves as a communication interface

that sparks public interaction among friends as well as strangers. The benefits of these

exchanges are pluripotent: The owner (or rather a partner) of the leaven is happy to get rid of

the relentlessly growing bacterial matter, and the receivers get the starter to begin their own

fermentation adventure. Along with that, new human-to-human and human-to-leaven friendships

are likely to be formed. These transactions occur largely outside the capitalist system of money

exchanges, and have a potential to disrupt the common form of urban food business. The

starters’ ampleness thus helps to constitute an alternative local food sub-market based on a

friendly barter, rather than on anonymized purchase. This model of food sharing greatly inspired

our GutHub design proposal.

GutHub fermentation trials: Open source jars and GutHub forking

Our initial idea was to design an open decentralized community of starter culture swappers. The

starters would work similarly as bitcoins (a form of an open source digital currency operated

collectively, with no central authority). However, we realized that to create a system of bacteria

blockchains and initiate the very first contacts within the GutHub network, we need to include at

least some minimal form of centralization. To create a non-hierarchical system of interconnected

ledgers who would be storing, procuring and sharing their starters in a long-term manner, we

needed to create some initiatory springboard, where all of these people and bacteria would

meet.

Hence, we proposed a first public fermentation meet-up, where we introduced the core GutHub

ideas and discussed them over a decent variety of fermented refreshments: Yoghurt, water

kefir, labneh, bread, pickles and sauerkraut. We invited the participants to bring their own

fermented goods, and so we additionally tasted some pineapple champagne, ginger cider,

honey brew, rice wine and dosa. We also managed to gather some starter cultures that we

ceremonially placed inside the world’s very first Fermentation Bank (a spacious fridge in a local

community garden), which was thereby officially inaugurated. The Bank is now open to the

public and invites anyone to come, withdraw a sample of any starter stored inside, and deposit

their own. Those who do not have any starters yet, can share some ideas, experiences, or any

other kind of skills in exchange for their starter withdrawal. As one of our members said, the

progress of the GutHub community is based on unlimited KrautSourcing.

The first public GutHub meet-up. (Picture © GutHub, 2015).

Maintaining the open-source ethos, we also opened a GitHub account (GitHub is a web-based

hosting service for peer-to-peer software development and code sharing), and invited the

audience to upload their fermentation recipes. Following the common GitHub practice, these

would then be edited and iterated (or in the GitHub lingo “forked”) by any member of the

community. This virtual extension of the physical Bank offers a remote access and non-direct

interactions that should, however, eventually transform into the real face-to-face encounters

around the fridge. Furthermore, we started a Fermentation GutHub facebook group, and also a

publicly accessible Google document that lists the starters currently present inside the Bank as

well as neccessary information on how to feed it and store it, and where does it come from. The

GutHub interface made of the Bank loaded with fermentation starters, the virtual platforms

storing the crowdsourced theoretical knowledge, and the community of fermentados based

around all that, then embodies an organic Thingiverse of the human – computer – bacteria

interactions and fermented remixes.

Future human-bacteria hookups

Having done this initial ethnography and the public introduction of the Bank with all related

virtual platforms, we now have a small pioneering community of GutHub early adopters (the

facebook group has 50 members at the time). We plan to continue with regular meet-ups, and

observe the encounters around the Bank as well as the forking activities on our GitHub. We plan

to create an online map mashup of starter culture ledgers based all around the city, and slowly

decentralize the system of GutHub swaps. Together with few more tech-savvy GutHub

members, we have also started to work on a prototype of DIY fermentation incubator for

convenient storage and maintenance of the starters. Along with these activities we hope to elicit

answers to our questions proposed above, and to report our findings about the open source HCI

design utilized for the development of local self-contained food initiative.

I eventually did not grow a little brother along with the GutHub tinkering. However, I did grow

some new bacteria in my gut, as well as some new human friends. As a GutHub member

Ibrahim told me the other day: “Hey bro, good to see you again”.

Resources:

Cuketka, p. (July 2011). Český Chleba. Retrieved from http://www.cuketka.cz/?p=6889

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1988). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia:

Bloomsbury Publishing.

Fermentation GutHub (2015). [Facebook group page]. Retrieved from

http://www.facebook.com/groups/1606102762957274

GutHub Fermentation bank [Google document] Retrieved from http://bit.ly/1EtVLDZ

Klein, Donald W.; Lansing M.; Harley, John (2006). Microbiology (6th ed.). New York: McGraw-

Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-255678-0.

Lakhani, K.R.; von Hippel, E. (June 2003). "How Open Source Software Works: Free User to

User Assistance". Research Policy 32 (6): 923–943.

Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network Theory. Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

PečemPecen. (2015). [Facebook group page]. Retrieved from

http://www.facebook.com/groups/386548024763970

Raw and Pure. (n.d.). [Website]. Retrieved from http://rawandpure.co.uk/kefir-kitchen/

Stengers, I. (2010). “Including Nonhumans in Political Theory: Opening Pandora’s Box?” In

Political Matter: Technoscience, Democracy, and Public Life, edited by Bruce Braun and Sarah

J. Whatmore, 3–35. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Related Documents