REVIEW Surgical management of intratemporal lesions A. BOZORG GRAYELI, H. EL GAREM, D. BOUCCARA & O. STERKERS Otolaryngology/Head and Neck Surgery Department, Ho ˆpital Beaujon, Clichy, France Accepted for publication 1 May 2001 BOZORG GRAYELI A ., EL GAREM H ., BOUCCARA D . & STERKERS O . (2001) Clin. Otolaryngol. 26, 357–366 Surgical management of intratemporal lesions In order to evaluate the decisional elements in the surgical strategy of deep-seated and/or extensive intratemporal lesions, a retrospective review of cases followed up between 1985 and 1996 in our department was undertaken. Eighty-one adult patients presenting temporal bone lesions located or extending beyond the middle ear limits excluding vestibular schwannomas and surgically treated were included. The population comprised 38 men and 43 women (mean age: 43 years, range: 17–81). Pre-, intra- and postoperative data were collected from medical files. The principal factors influencing the choice of the surgical approach were the location of the lesion and its presumed aggressiveness, the tumour involvement of the internal carotid artery and the labyrinth on preoperative imaging, and the preoperative hearing loss. A coherent algorithm based on these factors can be proposed for the surgical management of intratemporal lesions. High quality preoperative imaging is mandatory for the surgical planning. Keywords intratemporal tumour surgical approach strategy Extensive intratemporal lesions have always raised surgical difficulties because of the complex anatomy of the temporal bone and the multitude of tumour extension possibilities. 1 The main objective of the surgical treatment is the complete eradication of the lesion with minimal morbidity. However, owing to the vicinity of vital structures such as the carotid artery and many cranial nerves, this objective is not achieved in all cases. 1 To improve the surgical access to different temporal bone regions, and to reduce postoperative sequelae, many surgical approaches and their variants have been described. 2,3 The choice of the surgical approach and its adaptation to individual cases is based principally on a precise radiological work-up. In addition to imaging data, preoperative neurological and audiovestibular status, and the patient’s general condition, influence the therapeutic strategy. 3 The aim of this study was to evaluate the decisional factors in the management of intratemporal lesions and to define a strategic algorithm for their surgical treatment. Material and methods population A retrospective study of 81 consecutive cases of intratemporal lesions, located or extending beyond the middle ear limits and undergoing surgery between 1985 and 1996 in our depart- ment, was undertaken. Intracanalicular vestibular schwanno- mas were excluded from this study. The population comprised 38 men and 43 women (sex ratio ¼ 1.7). The mean age was 41 years (ranging from 16 to 60). The mean follow-up period was 27 months (ranging from 2 to 94 months). Sixty-six cases were operated on for the first time (81%) and 15 were treated surgically for recurrence (19%). Clin. Otolaryngol. 2001, 26, 357–366 # 2001 Blackwell Science Ltd 357 Correspondence: Alexis Bozorg Grayeli, M.D., Ph.D., Service d’Oto-Rhino-Laryngologie, Ho ˆpital Beaujon, 100 Boulevard Ge ´ne ´ral Leclerc, F-92118, Clichy Cedex, France (e-mail: [email protected]).

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

REVIEW

Surgical management of intratemporal lesions

A. BOZORG GRAYELI, H. EL GAREM, D. BOUCCARA & O. STERKERSOtolaryngology/Head and Neck Surgery Department, Hopital Beaujon, Clichy, France

Accepted for publication 1 May 2001

B O Z O R G G R AY E L I A. , E L G A R E M H. , B O U C C A R A D. & S T E R K E R S O.

(2001) Clin. Otolaryngol. 26, 357–366

Surgical management of intratemporal lesions

In order to evaluate the decisional elements in the surgical strategy of deep-seated and/or extensive intratemporal

lesions, a retrospective review of cases followed up between 1985 and 1996 in our department was undertaken.

Eighty-one adult patients presenting temporal bone lesions located or extending beyond the middle ear limits

excluding vestibular schwannomas and surgically treated were included. The population comprised

38 men and 43 women (mean age: 43 years, range: 17–81). Pre-, intra- and postoperative data were collected

from medical files. The principal factors influencing the choice of the surgical approach were the location of

the lesion and its presumed aggressiveness, the tumour involvement of the internal carotid artery and the labyrinth

on preoperative imaging, and the preoperative hearing loss. A coherent algorithm based on these factors can

be proposed for the surgical management of intratemporal lesions. High quality preoperative imaging is

mandatory for the surgical planning.

Keywords intratemporal tumour surgical approach strategy

Extensive intratemporal lesions have always raised surgical

difficulties because of the complex anatomy of the temporal

bone and the multitude of tumour extension possibilities.1 The

main objective of the surgical treatment is the complete

eradication of the lesion with minimal morbidity. However,

owing to the vicinity of vital structures such as the carotid

artery and many cranial nerves, this objective is not achieved

in all cases.1

To improve the surgical access to different temporal bone

regions, and to reduce postoperative sequelae, many surgical

approaches and their variants have been described.2,3 The

choice of the surgical approach and its adaptation to individual

cases is based principally on a precise radiological work-up.

In addition to imaging data, preoperative neurological and

audiovestibular status, and the patient’s general condition,

influence the therapeutic strategy.3

The aim of this study was to evaluate the decisional factors

in the management of intratemporal lesions and to define a

strategic algorithm for their surgical treatment.

Material and methods

populat ion

A retrospective study of 81 consecutive cases of intratemporal

lesions, located or extending beyond the middle ear limits and

undergoing surgery between 1985 and 1996 in our depart-

ment, was undertaken. Intracanalicular vestibular schwanno-

mas were excluded from this study. The population comprised

38 men and 43 women (sex ratio ¼ 1.7). The mean age was

41 years (ranging from 16 to 60). The mean follow-up period

was 27 months (ranging from 2 to 94 months). Sixty-six cases

were operated on for the first time (81%) and 15 were treated

surgically for recurrence (19%).

Clin. Otolaryngol. 2001, 26, 357–366

# 2001 Blackwell Science Ltd 357

Correspondence: Alexis Bozorg Grayeli, M.D., Ph.D., Serviced’Oto-Rhino-Laryngologie, Hopital Beaujon, 100 BoulevardGeneral Leclerc, F-92118, Clichy Cedex, France(e-mail: [email protected]).

tumour h i stology

The histological types observed in our series are summarized

in Table 1. Two papillary, epithelial tumours (2%) were

included in the malignant group because of their high local

aggressiveness.4,5 Miscellaneous benign lesions comprised

two meningiomas (2%) and one lipoma (1%) located in the

internal auditory canal and one meningioma (1%) in the

posterior foramen lacerum.

data collect ion

Data from medical files were collected concerning past med-

ical history, preoperative symptoms, neurological and audio-

vestibular clinical status, audiometric and vestibular tests

(electronystagmography or videonystagmography, with calo-

ric, rotational tests and gaze studies), facial electromyography

(EMG) and blink reflex test in case of clinical abnormality or

tumour encasement of the facial nerve and radiological exam-

inations, including computerized tomography (CT) scan and

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Type of approach, intrao-

perative observations, surgical sacrifice of neurovascular

structures and quality of macroscopic resection were also

noted. Postoperative data were obtained regarding comple-

mentary treatment, recurrence, complications, neurological

deficits, audiovestibular tests, radiological controls and pro-

fessional activity resumption.

pr e ope r at i v e ang iogr a phy

Angiography was performed in lesions appearing highly

vascularized on CT scan and MRI, and was followed by

tumour embolization when technically possible. In case of

carotid artery wall involvement by the lesion in patients with

preserved neurological and general conditions, a balloon

occlusion test and preoperative internal carotid artery occlu-

sion were performed.

su rg e ry

The surgical approaches performed in this series are summar-

ized in Table 2.3,6–8 Endoscopic assessment of the tumour

resection was performed in cases of bilobulated lesions and

intracranial extension.

cla s s i f icat i on s

Tumour locations and extensions assessed on preoperative

imaging were classified as apical, supralabyrinthine, infra-

labyrinthine, retrolabyrinthine and translabyrinthine accord-

ing to Fisch & Mattox.3 In addition to these five extension

types, intracanalicular and cervicomastoid lesions were dis-

tinguished (Figs 1 and 2).

The carotid artery segments were designated according to

Lasjaunias & Berenstein:9 C1, cervical segment; C2, intrape-

trous vertical segment; C3, intrapetrous horizontal segment

and C4, ascending portion in the anterior foramen lacerum.

Tumour size was estimated on preoperative imaging by

Table 1. Tumour histology in our series

Histology n (relative %)

Cholesteatoma 19 (23%)Paraganglioma 18 (22%)Schwannoma 12 (15%)

Malignant lesionsEpidermoid carcinoma

8 (10%)

Chondrosarcoma 3 (4%)Osteosarcoma 1 (1%)Histiocytofibroma 1 (1%)Melanoma 1 (1%)Adenoid cystic carcinoma 1 (1%)UCNT� 1 (1%)Papillary epithelial tumour 1 (1%)

Miscellaneous benign lesionsCholesterol granuloma

3 (4%)

Facial nerve angioma 3 (4%)Haemangioma 3 (4%)Meningioma 2 (2%)Lipoma 1 (1%)Fibrous dysplasia 1 (1%)Osteodysplasia 1 (1%)Chondroblastoma 1 (1%)

Total 81

�UCNT ¼ undifferentiated carcinoma of nasopharyngeal type.

Table 2. Surgical approaches in our series

Surgical approach n (relative%)

Mastoidectomy þ neck dissection� parotidectomy

10 (13%)

Infralabyrinthine 1 (1%)Infratemporal type A� labyrinthine resection� 14 (18%)Infratemporal type B� labyrinthine resection� 2 (2%)Middle cranial fossa�mastoidectomy 8 (9%)Extended middle cranial fossay 12 (15%)Retrolabyrinthinez 2 (2%)Subtotal petrosectomy� 4 (5%)Transotic� 20 (26%)Translabyrinthine 4 (5%)Transcochlear þ posterior re-routing of

facial nerve§2 (2%)

Total petrosectomy þ internal carotidartery resection

2 (2%)

Total 81

�According to Fisch & Mattox (1988).3

yAccording to Wigand (1998).6

zAccording to Darrouzet et al. (1997).7

§According to House & Hitselberger (1976).8

358 A. Bozorg Grayeli et al.

# 2001 Blackwell Science Ltd, Clinical Otolaryngology, 26, 357–366

measuring the greatest diameter of the lesion on coronal or

axial planes.

Mean hearing thresholds were calculated on air conduction

audiometry at 500, 1000, and 2000 Hz. These were considered

within normal limits when <25 dB, as mild hearing loss when

�25 and <45 dB, as moderate hearing loss when �45 and

<65 dB, as severe hearing loss when �65 and <85 dB, and as

profound hearing loss when �85 dB.10

Facial function was assessed clinically according to House

and Brackmann.11

stat i st ical t e st

Values presented are means� SEM. The statistical test used

was an unpaired t-test. Significant difference was considered

at P< 0.05.

Results

pr e s ent i ng symptom s

The mean delay between the onset of the symptoms and the

diagnosis was 38 days, ranging from five to 270 days. No

relation between the diagnosis delay and the histology, or the

tumour location, could be evidenced. Hearing loss, tinnitus

and imbalance were the most frequently reported symptoms

(Table 3). No tumour location or histology could be statisti-

cally related to these symptoms. In contrast, among 11 cases

of intense headache, seven (64%) were related to tumours with

an inflammatory component (cholesteatoma and cholesterol

granuloma) and the remaining four (36%) to malignant

tumours. Similarly, among nine cases of otalgia, six (67%)

malignant lesions, two aggressive paragangliomas and one

cholesteatoma were observed. Among the 22 cases of lesions

with intense pain, preoperative imaging indicated an apical

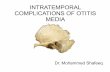

Figure 1. Classification of tumour locations. Locations are repre-sented on a lateral view of a right temporal bone with the projectionof the principal anatomical structures.

Figure 2. Preoperative imaging of six illustrative cases. White arrow heads show the lesion. (a) T1-sequence MRI coronal section showing aright supralabyrinthine cholesteatoma in contact with the temporal lobe; (b) T1-sequence MRI with gadolinium injection and axial viewdemonstrating a translabyrinthine epithelial papillary tumour; (c) axial CT scan with contrast product injection showing an apical epidermoidcarcinoma; (d) infralabyrinthine paraganglioma on T2-sequence MRI and coronal section; (e) CT scan axial view of left temporal boneshowing cervicomastoid schwannoma in its mastoid portion; (f) T2-sequence MRI showing the cervical extension of a left cervicomastoidfacial schwannoma.

# 2001 Blackwell Science Ltd, Clinical Otolaryngology, 26, 357–366

Surgical management of intratemporal lesions 359

location in 11 cases (50%) and an infralabyrinthine location in

eight cases (36%). Facial paresis, as a presenting symptom,

was observed in 24 cases (30%). This symptom was associated

with cholesteatoma in nine cases (38%), with lesions originat-

ing from the nerve (schwannoma and haemangioma) in seven

cases (29%) and with malignant lesions or aggressive para-

ganglioma in five cases (21%). No relationship between this

symptom and the tumour-extension type could be observed.

pr e ope r at i v e audiov e st i bular and

n eurolog ical status

Preoperative audiometry showed 32 cases (40%) of profound,

seven cases (9%) of severe, 17 cases (21%) of moderate and 10

cases (12%) of mild hearing loss. The 15 remaining patients

(19%) presented normal hearing. Among patients presenting

mild to severe hearing loss, 10 (29%) presented conductive

hearing loss, seven (21%) presented mixed conductive and

sensorineural hearing loss and the remaining 17 patients

(50%) presented pure sensorineural hearing loss.

Electronystagmography or videonystagmography results

were available in 70 patients (86%). The vestibular function

assessed by these tests was considered normal in 18 cases

(26%). A hyporeflectivity was observed in 16 cases (20%),

areflexia was reported in 19 cases (27%) and vestibular

hyporeflexia, associated with central nervous system abnorm-

alities, were evidenced in seven cases (10%).

Preoperative facial function was assessed as grade I in 38

patients (47%), grade II in 23 (28%), grade III in eight (10%),

grade IV in three (4%), grade V in two (2%) and grade VI in

seven patients (9%).

Trigeminal nerve deficiency was reported in seven cases

(9%). These cases were related to apical lesions in five

patients (71%) and to infralabyrinthine lesions with apical

extension in two cases (29%). Involvement of cranial nerves

IX, X and XI was clinically observed in 10 cases of infra-

labyrinthine (12%) and one case of translabyrinthine lesions

(1%). Hypoglossal paresis was noted in six infralabyrinthine

lesions (7%). Pyramidal syndrome was evidenced in one case

of giant fibrous dysplasia with cerebral temporal lobe com-

pression (1%). Cerebellar syndrome was reported in four

infralabyrinthine (5%) lesions and in one translabyrinthine

(1%) lesion.

factors i n flu enc i ng th e surg ical st r at egy

Tumour location on preoperative imaging

Extension types determined on preoperative imaging in each

type of surgical approach are summarized in Table 4. The

majority of the lesions (n¼ 60, 74%) were located in the

infralabyrinthine and apical compartments. Infralabyrinthine

lesions were removed through an approach preserving the

labyrinth in 13 cases (38%) and through a non-conservative

approach in 21 cases (62%). Among the latter subgroup the

labyrinthine sacrifice was decided based on the tumour exten-

sion to the otic capsula in 13 cases (62%) and to a preoperative

unserviceable hearing with an intact otic capsula on the

preoperative imaging in eight cases (38%).

Apical lesions extending to middle cranial fossa were

removed through an extended or a combined middle fossa

approach in 13 cases (50%). These lesions included limited

extensions to the C3 portion of the carotid canal (n¼ 4, 31%),

and to the cochlea (n¼ 2, 15%). Other conservative approaches

were employed in seven apical lesions (27%), which did not

involve the carotid canal or the inner ear structures. Finally, six

apical lesions (23%) were approached through the transotic

route. These lesions extended to the cochlea (n¼ 4, 66%) or to

the C2 and C3 segments of the intrapetrous carotid artery

(n¼ 3, 50%).

Supralabyrinthine lesions were approached exclusively

through the middle fossa route. In this group, one case of

superior semicircular canal fistula (33%) and one patient with

large cochlear destruction (33%) were noted.

Intracanalicular lesions were removed by translabyrinthine

or middle fossa approaches depending on preoperative hearing

loss.

Presumed histology

Relationship between tumour location and its histological

type was noted in this series (Table 4). Supralabyrinthine

lesions comprised exclusively cholesteatomas. Similarly,

intracanalicular lesions comprised exclusively benign lesions.

Table 3. Presenting symptoms

Symptom n (relative %)

Hypoacusis 39 (48%)Vertigo and/or imbalance 26 (32%)Facial paresis 24 (30%)Tinnitus 22 (27%)Pain

Headaches10 (12%)

Otalgia 9 (11%)Facial 2 (2%)Cervical 1 (1%)

Depression 8 (10%)Miscellaneous neurological signs(tremor, amnesia, seizures, ataxia, behavioural

abnormalities)

7 (9%)

Aspiration 5 (6%)Otorrhagia 5 (6%)Otorrhea 4 (5%)Intracranial hypertension 3 (4%)Facial hypo/paresthesia 3 (4%)Shoulder paresis 2 (2%)Visual acuity deficiency 1 (1%)Dysphonia 1 (1%)Cutaneous fistula 1 (1%)

# 2001 Blackwell Science Ltd, Clinical Otolaryngology, 26, 357–366

360 A. Bozorg Grayeli et al.

Infralabyrinthine lesions comprised 17 over the 18 paragan-

gliomas (94%) in our series. The remaining infralabyrinthine

lesions were principally composed of caudal nerve schwan-

nomas and malignant lesions.

Paragangliomas necessitated large surgical exposure

through infratemporal, transotic or total petrosectomy in 13

cases (87%). In contrast, the majority of cholesteatomas,

schwannomas and other benign lesions were managed by

approaches preserving the labyrinthine structures.

Carotid artery involvement

Tumour involvement of different carotid artery segments for

different tumour types and surgical approaches is summarized

in Table 5. The majority of paragangliomas (13 out of 18,

72%) and malignant lesions (12 out of 18, 66%) encased the

cervical or intrapetrous carotid artery. Carotid artery was

sacrificed in two extensive paragangliomas removed by total

petrosectomy (2%). In contrast, the carotid canal involvement

was observed in a low proportion of cholesteatomas (four out

of 19, 21%). The involvement of the cervical portion of the

carotid artery, which was only observed in paragangliomas

and malignant tumours, necessitated a cervical dissection

associated to the temporal bone approach.

Tumour size on preoperative imaging

Mean tumour size was 38� 2.4 mm. Lesion size was related to

its location. Translabyrinthine lesions measured 59� 12.4 mm

and were larger than infralabyrinthine (39� 2.1 mm), apical

(37� 3.5 mm) and cervicomastoid lesions (35� 5.0 mm)

(P< 0.05). Infralabyrinthine lesions were larger than supra-

labyrinthine lesions (25� 2.9 mm) (P< 0.05). The only

retrolabyrinthine lesion measured 25 mm and was similar to

supralabyrinthine lesions in size. Intracanalicular lesions

represented the smallest lesions in comparison with all

other locations with a mean diameter of 11.0� 1.35 mm

(P< 0.05).

Tumour size on preoperative imaging appeared to be related

to its aggressiveness. Malignant and epithelial papillary

lesions measured 46� 4.6 and 53� 7.5 mm respectively.

These tumour types had a larger diameter than cholesteatomas

(33� 2.1 mm) and schwannomas (33� 3.0 mm) (P< 0.05).

Paragangliomas’ mean diameter (41� 3.5 mm) was inter-

mediate between malignant lesions and cholesteatomas and

was not significantly different from these two groups. The

mean diameter of miscellaneous benign lesions, to the exclu-

sion of a giant fibrous dysplasia which measured 150 mm in its

greatest diameter, was 24� 4.1 mm. This group had the

smallest diameter in comparison with malignant lesions

(P< 0.01), epithelial papillary lesions, paragangliomas and

cholesteatomas (P< 0.05).

The diameter of lesions for which a labyrinthine preserva-

tion was decided (31� 2.1 mm) was smaller than the diameter

of those for which the labyrinth was sacrificed (46� 3.9 mm)

(P< 0.01).

Table 4. Surgical approaches in different tumour types and locations

�LR ¼ labyrinthine resection.

# 2001 Blackwell Science Ltd, Clinical Otolaryngology, 26, 357–366

Surgical management of intratemporal lesions 361

Labyrinthine involvement on preoperative imaging and

preoperative audio-vestibular status

Labyrinthine involvement by the lesion on preoperative

imaging was evidenced in 34 cases (42%). In this group,

24 patients (71%) presented with profound, two (6%)

with severe, six (18%) with moderate, one (3%) with mild

hearing losses and one patient (3%) presented with normal

hearing. For this patient, a superior semicircular canal

fistula was reported on preoperative imaging. Among cases

with labyrinthine fistula on preoperative imaging, eight

conservative surgical approaches were attempted (26%). In

these cases, the mean preoperative hearing loss on pure

tone air conduction audiometry was 53 dB (ranging from

20 to 90 dB).

Surgical approaches in each hearing loss subgroup are

summarized in Table 6. Approaches preserving the inner

ear structures were used in 88% of normal hearing and mild

hearing loss subgroups, in 50% of moderate, in 71% of severe

and in 17% of profound hearing loss subgroups.

As regards the preoperative vestibular function, approaches

preserving the labyrinth were decided in 67% of cases with

normal vestibular tests and in 63% of hyporeflexia cases. In

contrast, these conservative approaches were employed in

only 21% of patients presenting with areflexia and 28% of

cases with hyporeflexia associated to central nervous system

abnormalities.

po stope r at i v e r e sult s

Hearing loss and other cranial nerve function

The labyrinth was preserved during surgery in 41 cases (51%).

In this group, nine patients (22%) had preoperative profound

or severe hearing loss and postoperative profound hearing

loss. Among eight patients (20%) with preoperative moderate

hearing loss and preserved labyrinth, seven profound (88%)

and one moderate hearing losses (13%) were observed post-

operatively. In the group of eight patients (20%) with pre-

operative mild hearing loss and labyrinthine preservation,

three profound (38%), three moderate (38%), and one mild

(13%) hearing losses and one normal hearing (13%) were

reported. Finally, in the group of 16 patients (39%) with

preoperative normal hearing undergoing conservative surgery,

Table 5. Involved carotid artery segments by intratemporal lesions, their histology and surgical approaches

�Carotid artery segments according to Lasjaunias & Berenstein (1987):9 C1, cervical segment; C2, intrapetrous vertical segment; C3,intrapetrous horizontal segment, C4, ascending portion in the anterior foramen lacerum.�� LR ¼ labyrinthine resection.��� Transotic approach with neck dissection.

# 2001 Blackwell Science Ltd, Clinical Otolaryngology, 26, 357–366

362 A. Bozorg Grayeli et al.

data on postoperative hearing were available in eight cases

(50%). In these patients, six normal hearing (75%) and two

mild hearing losses (25%) were observed.

Postoperative facial function was evaluated as grade I in 23

cases (28%), grade II in 10 cases (12%), grade III in 12 cases

(15%), grade IV in 13 cases (16%), grade V in seven cases

(9%) and grade VI in 16 cases (20%). Among the 43 patients

presenting preoperative facial palsy (FP), five cases of

improvement (12%), 16 cases of stable function (37%) and

22 cases of deterioration (51%) were observed postopera-

tively. In 38 patients presenting preoperative normal facial

function, a postoperative FP was observed in 19 cases (50%).

Facial nerve rerouting was performed in 14 cases (17%).

Among these cases, 13 (93%) were of anterior type and

associated to an infratemporal approach and one (7%) was

posterior and associated to a transcochlear approach. The

nerve was interrupted during surgery in 14 cases (17%). In

this group, the surgical sacrifice was due to a lesion originating

from the facial nerve (schwannomas, haemangiomas) in six

cases (46%), malignant or aggressive lesions invading the

nerve (epidermoid carcinoma, epithelial papillary lesion,

paraganglioma) in five cases (38%) and to benign lesions

encasing the nerve (cholesteatoma, internal auditory canal

meningioma) in two cases (15%). Facial nerve was grafted

after surgical interruption in eight cases (53%). Facial nerve

graft was performed in six cases of facial nerve benign lesions

(75%), in one case of epithelial papillary lesion (13%) and

in one intracanalicular meningioma (13%). In these cases,

preoperative facial function assessed as grade II in three cases

(38%), grade III in two (25%), grade IV in two (25%) and

grade VI in one case (13%).

Ipsilateral trigeminal deficit was reported in six cases (7%).

Immediate postoperative caudal nerve deficit with swallowing

difficulties was observed in 23 cases (28%). In this group, 22

(96%) necessitated nutrition by temporary nasogastric tube

and four (17%) necessitated tracheotomy owing to aspiration.

At the last follow-up visit, five patients (22%) presented with

complete regression of the deficit, 15 (65%) showed a com-

pensated deficit and three (13%) complained of persisting

swallowing difficulties and aspiration.

Tumour resection quality

The tumour resection was macroscopically complete in 65

cases (80%). In these cases, postoperative imaging evidenced

residual lesion in two cases (3%). The incomplete resection

was reported in 16 cases (20%) and concerned malignant (11

cases) or aggressive lesions (four paragangiomas and one

meningioma). In this group, 14 lesions (88%) measured

35 mm or higher. Residual lesion encased the intrapetrous

carotid artery in four cases (25%), involved the temporal fossa

dura in four cases (25%), was located in the petrous apex,

clivus and cavernous sinus in three cases (19%), in the

cerebello-pontine angle in two cases (13%), in the posterior

foramen lacerum in two cases (13%) and encased the vertebral

artery in one case (6%). All malignant lesions underwent

postoperative radiotherapy.

Table 6. Preoperative hearing loss and type of surgical approach

Surgical approach

Hearing loss�

Profound(�85 dB)

Severe(�65 to >85 dB)

Moderate(�45 to >65 dB)

Mild(�25 to >45 dB)

Normal(<25 dB) Total

With inner ear preservationMastoidectomy – – 1 2 7 10 (12%)Infralabyrinthine – – – – 1 1 (1%)Retrolabyrinthine 1 – 1 – – 2 (2%)Middle fossa – – 1 2 1 4 (5%)Extended middle fossa 2 2 3 3 2 12 (15%)Middle fossa þ Mastoid – 1 1 – 2 4 (5%)Subtotal petrosectomy 1 1 1 – 1 4 (5%)Infratemporal Type A 1 – 1 1 2 5 (6%)

Type B – 1 – – – 1 (1%)With inner ear resection

Translabyrinthine 1 – 3 – – 4 (5%)Transotic 13 2 4 – 1 20 (25%)Transcochlear 1 – 1 – – 2 (2%)Infratemporal Aþ

labyrinthine resection7 – 1 1 – 9 (11%)

Infratemporal Bþlabyrinthine resection

– – – – 1 1 (1%)

Total petrosectomy 2 – – – – 2 (2%)Total 29 (36%) 7 (9%) 18 (22%) 9 (11%) 18 (22%) 81

�Mean hearing loss assessed on preoperative pure tone air conduction audiometry at 0.5, 1 and 2 KHz.

# 2001 Blackwell Science Ltd, Clinical Otolaryngology, 26, 357–366

Surgical management of intratemporal lesions 363

A recurrence was observed in five patients (6%). The mean

delay of recurrence detection after surgery was 26 months,

extremes ranging from 20 to 38 months. These recurrences

concerned two cholesteatomas and one adenoid cystic carci-

noma of the petrous apex, and two paragangliomas located in

infralabyrinthine and translabyrinthine regions.

Postoperative morbidity and mortality

Local or general infectious complications occurred in seven

cases (9%). They were managed medically in all cases.

Cerebrospinal fluid leak by the incision or as rhinorrhea

was noted in 13 cases (16%). These patients were treated

medically in 10 cases (12%) and necessitated surgical revision

in three cases (4%).

Three cases of postoperative ischaemic cerebral accident

were reported (4%). In one case (1%), this complication

occurred after the resection of a giant fibrous dysplasia with

temporal lobe compression. The two remaining cases (3%)

with extensive intratemporal and intracranial paragangliomas

presented with a fatal ischaemic neurological complication

during the immediate postoperative period. Other neurologi-

cal complications (seizures, intracranial hypertension and

brainstem compression by abdominal fat graft) were observed

in three cases (4%). These complications were regressive after

medical or surgical treatment. Patients who underwent inter-

nal carotid artery ligation did not present neurological com-

plications. Two patients (2%) died from a malignant tumour

evolution.

Information concerning postoperative professional activity

resumption was available in 46 cases (57%). Among these

cases, 30 patients (65%) resumed anterior professional

activity.

Postoperative mortality and morbidity was related to

tumour size. Lesions measured 90� 30.5 mm in patients

deceased by postoperative complication, 60� 20.0 mm in

patients deceased by tumour evolution, 44� 4.5 mm in con-

valescent patients at the last follow-up examination, and

32� 2.1 mm in patients having resumed their professional

activity at the last follow-up visit. No significant difference

was evidenced in the lesion’s size between patients deceased

by complication and those deceased by tumour evolution.

Tumour size in these two groups was larger than those in

convalescent and professionally active patients (P< 0.01 and

P< 0.001). Patient having resumed professional activity had

smaller lesions than convalescent patients at last follow-up

visit (P< 0.02). Follow-up duration was not significantly

different between convalescent and active patients (19� 5.9

and 21� 3.4 months respectively).

Discussion

Intratemporal extensive lesions represent a heterogeneous

pathologic entity as different tumour types and locations make

each case a unique situation. Despite this heterogeneity, the

surgical strategy for these lesions follow general rules that can

be highlighted.2

The aim of this retrospective study was to assess different

decisional elements in the surgical treatment of extensive

intratemporal lesions in the light of postoperative results

and to deduce an algorithm for the surgical approach.

The location of the lesion evaluated by preoperative

imaging represents the major decisional factor in the choice

of the surgical approach.2,3 The tumour location indicates

the possible involved neurovascular structures and is

helpful in predicting the type of the lesion.12 Consequently,

this data is the basis of many proposed classifications for

intratemporal lesions.2,13 The classification that we have

used in our series was first proposed by Fisch & Mattox,3

based on clinical observations and temporal bone cell

tract anatomy that offers a low resistance to tumour invasion.1

This classification subdivides the petrous pyramid into

four compartments around the labyrinthine block: apical,

supralabyrinthine, infralabyrinthine and retrolabyrinthine.

In addition, the translabyrinthine subgroup was assigned to

large lesions destroying the labyrinthine structures and

extending to the cerebellopontine angle. In order to include

all the possible locations for intratemporal lesions, intracanali-

cular and cervicomastoid lesions were also distinguished in

our series. Although this classification leads to a coherent

algorithm for the surgical strategy, it does not take in account

the extensions of the lesion to principal neurovascular

structures such as the internal carotid artery, the middle fossa

dura, the labyrinth or the facial nerve. As observed in our

series, this type of information is crucial in predicting the

functional results and the possible complications, and directly

influences the surgical approach.

The presumed tumour histology based on preoperative

imaging also influences the surgical strategy. In our series,

this information was deduced from the location, the imaging

characteristics, and clinical data including past medical his-

tory, preoperative symptoms and rapidity of evolution. The

tumour types encountered in our series can be divided into

three categories:4

1. Benign lesions with a slow growth, not invading the

adjacent neurovascular structures and presenting a low

recurrence risk after complete macroscopic resection. In

our series, this group is mainly represented by apical

cholesteatomas for which surgical strategy has been

reported,14 but also comprises schwannomas, cholesterol

granulomas, lipomas, haemangiomas and osteoblastomas.

2. Aggressive benign lesions comprising paragangliomas

and chordomas in our series. This group includes

benign lesions presenting at least one of the following

characteristics: rapid growth, invasion of neurovascular

structures, high recurrence risk after complete macroscopic

resection, and possibility of malignant transformation with

# 2001 Blackwell Science Ltd, Clinical Otolaryngology, 26, 357–366

364 A. Bozorg Grayeli et al.

metastasis. These lesions necessitated large surgical access

in order to control involved vessels and extensions.

3. Primary malignant or metastatic lesions with maximal

aggressiveness (rapid regional extension, adjacent structure

invasion and metastasis). These lesions necessitated the

largest surgical access possible with important resection

margins and complementary radiotherapy. This group

mainly included middle ear carcinomas, but also malignant

melanoma, sarcomas, adenoid cystic carcinomas, and

undifferentiated carcinoma of nasopharyngeal type invad-

ing the petrous apex in our series. Considering their high

potential of local invasion, papillary epithelial tumours can

also be included in this group.5

The tumour size in our series was related to its location and

aggressiveness and influenced the labyrinthine preservation.

Lesions measuring 35 mm or higher constituted the majority

of incomplete resection cases. Moreover, the lesion’s size was

related to postoperative mortality and morbidity. Many clas-

sifications take this parameter in account to determine the

surgical attitude and the prognosis.2,3

Tumour extensions are directly related to its size.3,13 In our

series, these extensions influenced the surgical attitude

towards the labyrinth, the facial nerve and the intrapetrous

carotid artery. Infralabyrinthine lesions, extending to the C3

(intrapetrous horizontal) portion of the internal carotid artery

and to the internal auditory canal through the infralabyrinthine

cell tracts, necessitated labyrinthine sacrifice. Similarly, apical

lesions extending to the internal aspect of the carotid canal and

the intradural space underwent approaches with labyrinthine

destruction. Surgical approach to intracanalicular lesions

Figure 3. Algorithm for surgical managementof deep-seated or extensive intratemporallesions based on tumour location, tumouraggressiveness (M, malignant; A, aggressive;B, benign) and preoperative hearing (þ,serviceable; – non serviceable). �LR ¼ labyr-inthine resection.

# 2001 Blackwell Science Ltd, Clinical Otolaryngology, 26, 357–366

Surgical management of intratemporal lesions 365

mainly depended on the extension of the lesion to the fundus

and the preoperative hearing function. Supralabyrinthine and

cervicomastoid lesions could be treated by conservative sur-

gical approaches owing to their type of extension. Suprala-

byrinthine lesions extended towards the middle fossa and

cervicomastoid lesions towards the stylomastoid forman.

The surgical attitude in our series based on tumour location

and aggressiveness, and the inner ear involvement on pre-

operative imaging is summarized in Fig. 3.

The functional results in our series could not be directly

compared to other series owing to differences in the tumour

types, locations and extensions.15–17 The poor auditory prog-

nosis in our series was mainly as a result of the tumour

destruction of the cochlea or the tumour extension to the

C3 portion of the intrapetrous carotid artery that necessitated

the cochlear sacrifice. Incomplete resection was observed

principally in aggressive tumours and its proportion in our

series was similar to that reported by Briner et al. (17%).16

Malignant lesions had a high mortality despite aggressive

surgical treatment in our series. In other series, this mortality

rate is reported to be 44% and 80%, 18 and 30 months after

surgery respectively.13,15 The rate of postoperative complica-

tions (28%) and consequent mortality (4%) in our series was

also similar to that reported in the literature.1,12,15 The possible

occurrence of fatal complications in the treatment of such

lesions underlines the importance of a complete preoperative

assessment of the lesion and the patient’s general condition.

In conclusion, the location and the size of the lesion, its

presumed aggressiveness, the internal carotid artery involve-

ment on preoperative imaging and the degree of preoperative

hearing loss were the principal decisional elements for the

choice of the surgical approach and the conservation of

the labyrinth in our series. Thus, a high quality preoperative

imaging is mandatory in the surgical planning for extensive

intratemporal lesions.

References

1 LEONETTI J.P., SMITH P.G., KLETZKER G.R. et al. (1996)Invasion patterns of advanced temporal bone malignancies.Am. J Otol. 17, 438–442

2 HIRSCH B.E, SEKHAR L.N. & KAMERE D.B. (1993) Transtem-poral and infratemporal approach for benign tumors of jugularforamen and temporal bone. In Surgery of Cranial Base Tumors,pp. 267–289. Raven Press, New York

3 FISCH U. & MATTOX D. (1988) Subtotal petrosectomy, transoticapproach to the cerebellopontine angle, infratemporal fossaapproach type A, and infratemporal fossa approach type B. InMicrosurgery of the Skull Base, pp. 4–609. Theime MedicalPublishers, New York

4 NAGER G.T. (1993) Tumours of the brain, nerve sheath,meninges, brain, and other space occupying lesions of thetemporal bone. In Pathology of the Ear and Temporal Bone, pp.515–895. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore

5 FEGHALI J.G., LEVIN R.J., LLENA J. et al. (1995) Aggressivepapillary tumors of the endolymphatic sac: clinical and tissueculture characteristics. Am. J. Otol. 16, 778–782

6 WIGAND M.E. (1998) The enlarged middle fossa approach to thecerebello-pontine angle. Technique and indications. Rev. Lar-yngol. Otol. Rhinol. 119, 159–162

7 DARROUZET V., GUERIN J., AOUAD N. et al. (1997) The widenedretrolabyrinthine approach: a new concept in acoustic neuromasurgery. J. Neurosurg. 86, 812–821

8 HOUSE W.F. & HITSELBERGER W.E. (1976) The transcochlearapproach to the skull base. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg.,102, 334–342

9 LASJAUNIAS P. & BERENSTEIN A. (1987) Carotid artery. InSurgical Neuroangiography, pp. 2–11. Springer–Verlag, Berlin

10 STELMACHOWICZ P.G. & GORGA M.P. (1992) Auditory functiontests. In Otolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery, pp. 2699–2717. Mosby-Year Book, St. Louis

11 HOUSE J.W. & BRACKMANN D.E. (1985) Facial nerve gradingsystem. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 3, 184–193

12 CONSTANTINO P.D. & JANECKA I.P. (1993) Cranial base surgery.In Head and Neck Surgery: Otolaryngology, pp. 1411–1430.Lippincott, Philadelphia

13 POMERANZ S., SEKHAR L.N., JANECKA I.P. et al. (1993)Classification, technique and results of surgical resection ofpetrous bone tumors. In Surgery of Cranial Base Tumors, pp.317–335. Raven Press, New York

14 BOZORG GRAYELI A., MOSNIER I., EL GAREM H. et al. (2000)Extensive intratemporal cholesteatoma: surgical strategy. Am. J.Otol. 21, 774–781

15 SEKHAR L.N., POMERANZ S., JANECKA I.P. et al. (1992)Temporal bone neoplasms: a report on 20 surgically treatedcases. J. Neurosurg. 76, 578–587

16 BRINER H.R., LINDER T.E., PAUW B. et al. (1999) Long termresults of surgery for temporal bone paragangliomas. Laryngo-scope 109, 577–583

17 POE D.S., JACKSON G., GLASSCOCK M.E. et al. (1991) Longterm results after lateral cranial base surgery. Laryngoscope 101,372–378

# 2001 Blackwell Science Ltd, Clinical Otolaryngology, 26, 357–366

366 A. Bozorg Grayeli et al.

Related Documents