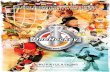

ESSAYS BY: Rosabeth Moss Kanter Christopher Lydon Ilan Stavans Joan Vennochi Alan Wolfe Re-mapping Massachusetts politics A return to Heritage Road POLITICS, IDEAS & CIVIC LIFE IN MASSACHUSETTS SPRING 2006 $5.00 THEN AND NOW A decade of change 10th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE PLUS Harry Spence: Commissioner under siege 21/04/06 08:18:05 21/04/06 08:18:05

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

ESSAYS BY: Rosabeth Moss Kanter Christopher Lydon Ilan Stavans Joan Vennochi Alan Wolfe

Re-mapping Massachusetts politics

A return to Heritage Road

P O L I T I C S , I D E A S & C I V I C L I F E I N M A S S AC H U S E T T S

SPRING 2006 $5.00

THEN AND NOWA decade of change

10th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE

PLUS Harry Spence: Commissioner under siege

10th ANN

IVERSARY ISSUE

SPRING

2006

MassINC thanks the many individuals and organizations whose support makes CommonWealth possible.

lead sponsors Bank of America • Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts • The Boston Foundation • Chris & Hilary Gabrieli Mellon New England • National Grid • Nellie Mae Education Foundation • Recycled Paper Printing, Inc. The Schott Foundation for Public Education • Fran & Charles Rodgers • State Street Corporation • Verizon Communications

major sponsors AARP Massachusetts • Ronald M. Ansin Foundation • Boston Private Bank & Trust Company • Citizens Bank • Comcast Irene E. & George A. Davis Foundation • Edwards, Angell, Palmer & Dodge, LLP • Fallon Community Health Plan Fidelity Investments • The Paul and Phyllis Fireman Charitable Foundation • Foley Hoag LLP • The Gillette Company Goodwin Procter LLP • Harvard Pilgrim Health Care • Hunt Alternatives Fund • IBM • John Hancock Financial Services • KeySpan Liberty Mutual Group • MassDevelopment • Massachusetts Foundation for the Humanities • Massachusetts Medical Society Massachusetts State Lottery Commission • Massachusetts Technology Collaborative • The MENTOR Network • Monitor Group Monster North America • NAIOP, Massachusetts Chapter • New England Regional Council of Carpenters • Oak Foundation The Omni Parker House • Partners HealthCare • Putnam Investments • Savings Bank Life Insurance • Tishman Speyer Tufts Health Plan • William E. & Bertha E. Schrafft Charitable Trust • State House News Service • The University of Phoenix

contributing sponsors A.D. Makepeace Company • Associated Industries of Massachusetts • Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center The Beal Companies LLP • Bingham McCutchen LLP • Boston Carmen’s Union • Boston Sand & Gravel Company Boston Society of Architects/AIA • Boston University • Cabot Corporation • Carruth Capital LLC • The Charles HotelGerald & Kate Chertavian • Children’s Hospital Boston • Commonwealth Corporation • Delta Dental Plan of Massachusetts Denterlein Worldwide • EMC Corporation • Philip & Sandra Gordon • Harvard University • Holland & Knight LLP Home Builders Association of Massachusetts • The Hyams Foundation • Johnson & Haley • KPMG LLP • Peter & Carolyn Lynch Massachusetts AFL-CIO • Massachusetts Building Trades Council • Massachusetts Educational Financing Authority Massachusetts Health and Educational Facilities Authority • Massachusetts High Technology Council • Massachusetts Hospital Association • MassEnvelopePlus • MassHousing • Massport • The McCourt Company, Inc. • Mercer Human Resource Consulting Merrimack Valley Economic Development Council • Microsoft Corporation • ML Strategies LLC • New Boston Fund, Inc. • New Tilt Nixon Peabody LLP • Northeastern University • Nutter McClennen & Fish LLP • Paradigm Properties • Retailers Association of Massachusetts • RSA Security Inc. • Carl and Ruth Shapiro Family Foundation • Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP The University of Massachusetts • Veritude LLC • Wainwright Bank & Trust Company • WolfBlock Public Strategies LLC

For more information on joining the sponsorship program call MassINC at 617.742.6800 ext. 101.

Visit MassINC online at www.massinc.org

18 Tremont Street, Suite 1120Boston, MA 02108

Address Service Requested

PRESORTEDSTANDARD

U.S. POSTAGEPAID

HOLLISTON, MAPERMIT NO. 72

cv griffe.indd 1cv griffe.indd 1 21/04/06 08:18:0521/04/06 08:18:05

HELP OUR HELP OUR CHILDREN CHILDREN ACHIEVEACHIEVE

WE CANHELP OUR CHILDREN ACHIEVE

IBM proudly congratulates Massachusetts Institute for a New Commonwealth for helping to improve our schools.Working in partnership with educators around the world, IBM is developing technology solutions that are helping students achieve. Together our goal is to lead and implement change in our schools and accelerate student learning.For more information on the philanthropic goals of IBM, visit ibm.com/ibm/ibmgives.

IBM

and

the I

BM lo

go a

re re

gist

ered

trad

emar

ks o

f Int

erna

tiona

l Bus

ines

s Mac

hine

s Cor

pora

tion

in th

e Uni

ted

Stat

es an

d/or

oth

er co

untri

es. O

ther

com

pany

, pro

duct

and

serv

ice n

ames

may

be t

rade

mar

ks o

r ser

vice m

arks

of o

ther

s. ©

2006

IBM

Cor

pora

tion.

All

right

s res

erve

d.

Delivering energy safely, reliably, efficiently and responsibly.

Focusing on the Future

gr d

National Grid meets the energy delivery needs of more than three millioncustomers in the northeastern U.S. through our delivery companies in NewYork, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and New Hampshire. We also transmitelectricity across 9,000 miles of high-voltage circuits in New England andNew York and are at the forefront of improving electricity markets for thebenefit of customers. At National Grid, we’re focusing on the future.

NYSE Symbol: NGGnationalgrid.com

cv griffe.indd 2cv griffe.indd 2 18/04/06 09:52:3618/04/06 09:52:36

Good Citizenship

True generosity is not measured in money alone. It’s measured in people.

At State Street, we believe being an industry leader carries with it a

responsibility for good citizenship. Active engagement with our communities

around the world, as a partner and as a leader, is one of our fundamental

values. We are proud of our heritage of corporate citizenship.

For more information, please visit www.statestreet.com.

© 2005 STATE STREET CORPORATION. 05-CAF04601205

INVESTMENT SERVICING INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT INVESTMENT RESEARCH AND TRADING

2 CommonWealth S P R I N G 2006

CommonWealtheditor Robert [email protected] | 617.742.6800 ext. 105

associate editorsMichael Jonas [email protected] | 617.742.6800 ext. 124

Robert David Sullivan [email protected] | 617.742.6800 ext. 121

staff writer/issuesource.org coordinatorGabrielle [email protected] | 617.742.6800 ext. 142

art director Heather Hartshorn

contributing writers Mary Carey, Christopher Daly,Ray Hainer, Richard A. Hogarty, James V. Horrigan,Dan Kennedy, Jeffrey Klineman, Neil Miller, Laura Pappano,Robert Preer, Phil Primack, B.J. Roche, Ralph Whitehead Jr.,Katharine Whittemore

washington correspondent Shawn Zeller

proofreader Jessica Murphy

editorial advisors Mickey Edwards, Ed Fouhy, Alex S. Jones,Mary Jo Meisner, Ellen Ruppel Shell, Alan Wolfe

publisher Ian [email protected] | 617.742.6800 ext. 103

sponsorship and advertising Rob [email protected] | 617.742.6800 ext. 101

circulation Emily [email protected] | 617.742.6800 ext. 109

interns David Undercoffler

> Full contents, as well as online exclusives,are available at www.massinc.org

CommonWealth (ISSN pending) is published quarterly by the MassachusettsInstitute for a New Commonwealth (MassINC), 18 Tremont St., Suite 1120,Boston, MA 02108. Telephone: 617-742-6800 ext. 109, fax: 617-589-0929.Volume 11, Number 3, Spring 2006. Third Class postage paid at Holliston, MA.To subscribe to CommonWealth, become a Friend of MassINC for $50 per year and receive discounts on MassINC research reports and invitations toMassINC forums and events. Postmaster: Send address changes to CirculationDirector, MassINC, 18 Tremont St., Suite 1120, Boston, MA 02108. Letters to theeditor accepted by e-mail at [email protected]. The views expressed in thispublication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of MassINC’sdirectors, advisors, or staff.

MassINC is a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt charitable organization. The mission ofMassINC is to develop a public agenda for Massachusetts that promotes the growth and vitality of the middle class. MassINC is a nonpartisan,evidence-based organization. MassINC’s work is published for educational purposes and should not be construed as an attempt to influence any electionor legislative action.

LET’SGETREAL!Making MassachusettsWork for You

RealTalk is a series of conversations

about what young professionals

and working adults can do to make

a living, raise a family, and build

stronger communities for us all. Join

in the discussion and become one

of the more than 1,000 participants

involved in RealTalk. For information

about upcoming RealTalk programs—

including our networking events —

log on to www.massinc.org.

Presented by MassINC and ONEin3 Boston and supported by over a dozen Greater Boston Civic Organizations.

RealTalk is supported in part by generous contributions from the Boston RedevelopmentAuthority, The New Community Fund and State Street Bank.

S P R I N G 2006 CommonWealth 3

Anonymous (5)Tom Alperin Joseph D. Alviani & Elizabeth Bell StengelJoel B. Alvord Carol & Howard AndersonRonald M. AnsinRichard J. & Mary A. BarryDavid BegelferThe Bilezikian FamilyGus Bickford Joan & John BokFrancis & Margaret BowlesIan & Hannah BowlesRick & Nonnie BurnesAndrew J. CalamareHeather & Charles CampionMarsh & Missy CarterNeil & Martha ChayetGerald & Kate ChertavianCeline McDonald & Vin CipollaMargaret J. ClowesDorothy & Edward ColbertFerdinand Colloredo-MansfeldFranz Colloredo-Mansfeld Woolsey S. Conover William F. CoyneJohn Craigin & Marilyn Fife Cheryl CroninMichael F. CroninStephen P. Crosby & Helen R. StriederBob Crowe

Sandrine & John Cullinane Jr.Thomas G. DavisRichard B. DeWolfeRoger D. DonoghueTim DuncanWilliam & Laura EatonPhilip J. EdmundsonSusan & William ElsbreeWendy EverettNeal Finnegan David FeinbergChristopher Fox & Ellen Remmer Robert B. FraserChris & Hilary GabrieliDarius W. Gaskins, Jr.Paula GoldLena & Richard Goldberg Carol R. & Avram J. Goldberg Philip & Sandra Gordon Jim & Meg GordonJeffrey Grogan Barbara & Steve GrossmanRay & Gloria White HammondBruce & Ellen Roy HerzfelderHarold HestnesArnold HiattJoanne Hilferty Michael Hogan & Margaret Dwyer Amos & Barbara HostetterPhilip JohnstonJeffrey JonesRobin & Tripp Jones

Sara & Hugh JonesMichael B. Keating, Esq.Dennis M. KelleherTom KershawJulie & Mitchell KertzmanRichard L. Kobus Stephen W. Kidder & JudithMaloneAnne & Robert LarnerGloria & Allen LarsonPaul & Barbara Levy Chuck & Susie Longfield R.J. LymanCarolyn & Peter LynchMark Maloney & Georgia Murray Dan M. MartinPaul & Judy MatteraDavid McGrathPeter & Rosanne Bacon MeadeMelvin Miller & SandraCasagrand Nicholas & Nayla MitropoulosJames T. MorrisJohn E. Murphy, Jr.Pamela Murray Paul Nace & Sally JacksonScott A. NathanFred NewmanPaul C. O’BrienJoseph O’DonnellRandy PeelerHilary Pennington & BrianBosworth

Finley H. Perry, Jr.Daniel A. PhillipsDiana C. Pisciotta & Mark S. Sternman Maureen PompeoMichael E. PorterMark & Sarah RobinsonFran & Charles RodgersBarbara & Stephen RoopMichael & Ellen Sandler John SassoHelen Chin SchlichteKaren SchwartzmanRichard P. SergelRobert K. Sheridan Alan D. Solomont & Susan Lewis SolomontHelen B. SpauldingPatricia & David F. SquireM. Joshua TolkoffGregory Torres & Elizabeth Pattullo Tom & Tory VallelyE. Denis WalshMichael D. Webb David C. Weinstein Robert F. WhiteHelene & Grant Wilson Leonard A. WilsonEllen M. ZanePaul Zintl

For information on joining The Citizens’ Circle, contact MassINC at (617) 742-6800 ext. 101

TheCITIZENS’ CIRCLE

MassINC’s Citizens’ Circle brings together people who care about the future of Massachusetts.The generosity of our Citizens’ Circle members has a powerful impact on every aspect of our work.We are pleased to extend significant benefits, including invitations to our private Newsmaker series, to those who join with a minimum annual contribution of $1,000.

4 CommonWealth S P R I N G 2006

chairmen of the board Gloria Cordes Larson Peter Meade

board of directorsIan Bowles, ex officioDavid BegelferAndrew J. CalamareHeather P. CampionKathleen CasavantNeil ChayetGeri DenterleinMark ErlichDavid H. FeinbergRobert B. FraserC. Jeffrey GroganSteve GrossmanRaymond HammondBruce HerzfelderHarold HestnesJoanne Jaxtimer

Jeffrey JonesTripp JonesElaine KamarckPaul LevyR.J. LymanPaul MatteraKristen McCormackMelvin B. MillerHilary C. PenningtonDeirdre PhillipsMichael E. PorterMark E. RobinsonCharles S. RodgersAlan D. SolomontCelia WcisloDavid C. Weinstein

honoraryMitchell Kertzman, Founding ChairmanJohn C. Rennie, in memoriam

president & ceo Ian Bowles

vice president John Schneider

director of program development Katherine S. McHugh

director of strategic partnerships Rob Zaccardi

director of communications Michael McWilliams

webmaster Geoffrey Kravitz

research director Dana Ansel

research associate Greg Leiserson

programs & policy associate Eric McLean-Shinaman

outreach manager Emily Wood

director of finance & administration David Martin

office manager & development assistant Caitlin Schwager

board of policy advisors economic prosperity Peter D. Enrich, Rosabeth Moss Kanter,Edward Moscovitch, Andrew Sum, David A. Tibbetts

lifelong learning Harneen Chernow, Carole A. Cowan,William L. Dandridge, John D. Donahue, Michael B. Gritton,Sarah Kass, S. Paul Reville, Leonard A. Wilson

safe neighborhoods Jay Ashe, William J. Bratton, Mark A.R. Kleiman,Anne Morrison Piehl, Eugene F. Rivers 3rd, Donald K. Stern

civic renewal Alan Khazei, Larry Overlan, Jeffrey Leigh Sedgwick

Hi-tech services are our job.

Community service is our responsibility.

You know we provide the best in Digital

Cable, High-Speed Internet and Digital

Voice services. But, we do more than help

the people in our communities stay

connected — we strive to make real

connections with them. That's because

this is our home, too. So, by supportingMassINC., we're doing what we can tobuild a better community — for all of us.

Call 1.800.COMCAST or visit www.comcast.comto find out more about Comcast products in your area.

G30-081205-V1

S P R I N G 2006 CommonWealth 5

ARTICLES

76 | HERITAGE ROAD REVISITED In 1996 and 2001 CommonWealth traveled to one street in Billerica to takethe pulse of the suburban middle class. We’ve gone backagain, finding comfort and anxiety. BY MICHAEL JONAS

86 | SHIFTING GROUND In 2002, we surveyed the political landscape and found Massachusetts to be not one state but 10. Now, we draw a new map of Bay State politics,just in time for the gubernatorial race.BY ROBERT DAVID SULLIVAN

100 | HAZARDOUS DUTY Harry Spence has made a career of turning around failing public agencies. In theDepartment of Social Services, has he met his match? BY GABRIELLE GURLEY

DISCUSSION112 | CONVERSATION Historian Thomas O’Connor on making Boston

the Athens of America

121 | REVIEW Mayflower presents the Plymouth story as tragedyBY WILLIAM M. FOWLER JR.

125 | TWO BITS 150th anniversary of a caning BY JAMES V. HORRIGAN

DEPARTMENTS7 | CORRESPONDENCE

10 | PUBLISHER’S NOTE

13 | CIVIC SENSE BY ROBERT KEOUGH

17 | STATE OF THE STATES EducationWeek grades public schools BY ROBERT DAVID SULLIVAN

19 | HEAD COUNT Town selectmen with big-city constituenciesBY ROBERT DAVID SULLIVAN

20 | STATISTICALLY SIGNIFICANT The Bay State’s global twins; NewBedford’s big catch; etc.BY ROBERT DAVID SULLIVAN

23 | INQUIRIES Troubled charter schoolsget direction; public pension chaosattracts scrutiny; post-release supervi-sion gets little traction; the pilotschool concept comes to Fitchburg;Kerry gets a new aide with game;Fairhaven loses both taxes and jobsto AT&T

33 | WASHINGTON NOTEBOOK MeetJim McGovern, congressional class of ’96 and godfather of Worcesterpolitics BY SHAWN ZELLER

37 | TOWN MEETING MONITORUpscale Medway teeters on the brinkof financial ruin BY RAY HAINER

43 | MASS.MEDIA Paul La Camera takesWBUR local BY DAN KENNEDY

COVER ILLUSTRATION BY POLLY BECKER

CommonWealthtenth anniversary issue | spring 2006

50 | ON THE COVERTHEN AND NOW On the occasion of CommonWealth’s 10th anniversary, we asked five eminent writers to reflect onchanges in Massachusetts,and its place in the world,over those years. Essays by:ROSABETH MOSS KANTERCHRISTOPHER LYDONILAN STAVANSJOAN VENNOCHIALAN WOLFE

6 CommonWealth S P R I N G 2006

“I’m never goingback to paper prescriptions. Ever.”

At Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts we understand the importance technology can

play in helping doctors improve patient care. That’s why we’ve teamed up with the healthcare

community to help physicians like Dr. Baumel get the technology they need — like handheld

computers for electronic prescribing, for example. It ’s just one of the many things Blue Cross is

doing to keep all of Massachusetts healthy. For more, log on to www.bluecrossma.com.

®An Independent Licensee of the Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association.

Dr. Andrew Baumel, Framingham Pediatrics

S P R I N G 2006 CommonWealth 7

correspondence

CRIME CAN BE CURBEDTHROUGH SMART DESIGNWhy do reporters assume they havethe knowledge to judge one crime reduction strategy over another(“Crime and Puzzlement,” CW, Win-ter ’06)? Based on 35 years of experi-ence in crime prevention throughurban planning and design, I am con-stantly amazed by the shallowness ofreporters’ judgments on which pro-gram works or doesn’t work. Report-ers need to do research in crime pre-vention as they would in reporting thecrime that is committed. They mightbegin by pointing out the differencebetween apprehension and preven-tion, and then examining the differ-ent types of prevention strategies thatare available.

The reason that a program such asthe ministers-and-gangs strategy is sohard to reconstruct is that it is human-resource-based. Because it was creat-ed and led by one or more key peoplewho were able to energize others andraise special funding, this approachwas, for a short time, able to have animpact on reducing certain targetedcrimes. Once the funding runs out—or the leaders move on, are reassigned,or simply get burned out—programslike this dissolve, and the crimes comeback as strong as ever.

In contrast, crime preventionthrough urban planning and designworks well, and indefinitely, becausesuch strategies are physical and notdependent upon individual or groupenthusiasm — or, for that matter,continuous funding. Example: If ahigh school draws students from one neighborhood through anotherneighborhood, it creates a range ofcrime opportunities, and some of thestudents take advantage of theseopportunities to commit crimes. Thehigh school is unwittingly acting as

a “crime generator,” even though thecrimes are not committed on schoolgrounds. By either redrawing theschool-district lines so that studentsare not forced to walk through anoth-er neighborhood, or redesigning thestreet and sidewalk system so as not toallow pedestrian circulation from theadjacent neighborhood through thetarget neighborhood, the result willbe the prevention of all types of crimesthis “crime/environmental phenom-ena” caused. This is crime preventionthrough urban planning, or “strategiccriminology.” While this field is notwell known, it has met with significantsuccess where it has been applied.

Richard Andrew GardinerRAGA/Gardiner Associates

Urban Planning & Community DesignNewburyport

DOES SHRINKING STATENEED MORE POWER?Strange to read, in Matt Kelly’s inter-esting article (“Power Failure”), thatdemand for electricity in Massachu-setts is expected to spike up 16 per-cent by 2014, even as the state con-tinues to lose population, as notedelsewhere in the magazine. Does theshrinking population really need togobble up an increasing number ofmegawatt-hours, even as global warm-ing becomes an increasingly urgentthreat, and global supplies of the fos-sil fuels begin to get tight? When willour leaders move beyond rhetoric onenergy issues, and instead work moreaggressively to actually reduce fossil-fuel-driven energy demand? We couldall—citizens, business, and govern-ment alike—become much more effi-cient users of energy, but no one hasreally asked us to.

Viki BokJamaica Plain

IMMIGRANT STUDENTSNEED PARENTS INVOLVEDThank you for the attention to appro-priate schooling for our state’s immi-grant children (“Sink or Swim”). LauraPappano provides thoughtful insightinto the politics and policy issues andhow they impact the classroom.

The role of parents is conspicuous-ly absent from the discussion. For allthe faults of the old bilingual educa-tion law, it properly empowered par-ents. Local communities were obligedto inform and seek immigrant parents’voices on issues and to offer parenteducation opportunities. These mea-sures ensured that parents were seenas partners rather than clients, a sig-nificant change that supports bettereducational outcomes for children,whether from the suburbs or the ten-ement districts. These parent initia-tives also paid rewards in assistingimmigrant families in establishingand mobilizing social networks.

There may be fewer strands in thesafety net for immigrant families inMassachusetts today. Given that theCommonwealth’s population, econo-my, and congressional representationdepend on newcomers, we ought topay closer attention to their needs.

Jorge M. Cardoso Ed.DExecutive Director

Institute for Responsive Education Cambridge College

Cambridge

correspondence

‘ANTI-GROWTH’ LABELAPPLIED WITHOUT BASISIn the article “House Rules” (Growth& Development Extra 2006), theauthor, Michael Jonas, referred to meas an “anti-growth activist.” I cannotimagine how he came up with thatbroad characterization when the onlyconversation I ever had with him wasabout the history and appropriatenessof certain high-density developmentsin and around the South Shore andBoston, not about generalities ofgrowth. What is this, an attempt toplace a kind of “burden of proof” fora person to disprove a lie? How wouldJonas like being labeled an anti-accu-racy writer?

Joseph PecevichOcean Bluff (Marshfield)

ARLINGTON TALE FULLOF ERROR AND BIASAs an early subscriber to your maga-zine, I have come to rely upon it as animpartial source of information onpublic affairs. However, when themagazine becomes a platform for bla-tant pro-developer propaganda, sup-ported by lazy reporting and invented“facts,” I find such reliance is mis-placed.

The reference is to the article“Bitter Pill” by Alexander von Hoff-man (Growth & Development Extra2006), an article fraught with errata,selective misquotes, and advocacy ofa social engineering and land use pol-icy that may be summarized in a fewwords: Let the Arlingtons becomehopelessly dense, so that the Lincolnsand Carlisles may remain pristine.

Von Hoffman characterizes thedebates over growth as some sort ofclass warfare. In fact, by the late 1960s,Arlington’s five square miles housedover 50,000 people. It was not onlythe densest town in the state but theseventh densest community, denserthan the city of Boston. People acrossa range of social and economic groupsand from all parts of the community

were appalled by the vanishing openspace, and the intrusion of high-rise,out-of-scale apartment blocks in theirneighborhoods. Those concernedwith historical and architectural her-itage were concerned that developersseemed to pounce upon the finestold houses and buildings for demoli-tion and redevelopment. The Histori-cal Commission was established byvote of town meeting in 1970, but itwas not until many years later that itachieved the power to delay—notveto, as von Hoffman states—destruc-tion of historical resources, and manysuch resources have in fact been sincelost to developers.

His description of the 1973 “stick-er” election is almost entirely incor-rect, and an example of inventingfacts in order to support his pre-determined conclusions. Again, therewas no class warfare involved, andpro- and anti-developer figures wereactive in all four campaigns. MargaretSpengler and George Rugg, the stickercandidates, did not replace “two old-line incumbent selectmen who hadmaneuvered to keep [them] off theballot.” One selectman had been elect-ed the previous year as treasurer, andhis seat was filled by the candidatewho had finished third in the select-men’s race that year. The other incum-bent, a strongly pro-environmentpolitician, decided not to run for re-election. The question raised by anoth-er candidate, Jack Donahue, waswhether members of the FinanceCommittee, as Spengler and Ruggwere, could run for another townoffice. He persuaded the town clerkto rule them off the ballot, but theyran on a sticker campaign and wereelected overwhelmingly. They werenot seated until the case was decidedin their favor by the Supreme JudicialCourt.

The long section devoted to the re-development of the Time Oldsmobilesite is, as is typical, fraught with errors.The quote from Richard Keshian that“many only develop in Arlington

once” is unsupported by any facts,and is belied by the fact that Keshian’sown client, Michael Collins (a Win-chester resident), currently has threeprojects underway here, and severalmore to his “credit.” The Osco proj-ect was ultimately rejected by the Re-development Board because the siteis at what traffic people call a “failedintersection”—a finding that wasultimately supported by the LandCourt after the judge took a look at ithimself. Collins, who then obtaineddevelopment rights to the property,consulted with town officials andsome (but not all) neighbors, butignored whatever the latter had tosay. He obtained the support of theadjacent historic church by offeringto give them part of the land, an offerthat he later retracted. The fire chief,not the Redevelopment Board, re-quired that access for fire trucks beadequate, for the protection of theprospective residents.

My own role in this affair is gross-ly mischaracterized. I, and the chair-man of the Historical Commission,had a long meeting with Collins’sarchitect, and I was quite surprised atthe next hearing to find that not oneof the modest ideas offered to mitigatethe appearance of the project had beenadopted. (By the way, 18th-centurypatriot Jason Russell, like most peo-ple, didn’t use a hyphen between hisfirst and last names.)

Contrary to von Hoffman’s asser-tions, opponents made it quite clearwhy they were unhappy with certainaspects of the project. A block northof this site is another Collins projectcrowded densely onto a site adjacentto one of the few remaining ballfieldsand widely derided as the ugliestdevelopment in town. (At the oppo-site corner, by contrast, is a beautifulrenovation of historic houses doneby a more sensitive Arlington devel-oper.) Surrounding Collins’s Mill/Summer St. project at the sidewalk isa low stone wall, described by someas a tank barricade, behind which is a

8 CommonWealth S P R I N G 2006

high fence. We didn’t want to see thatat the important Mill/MassachusettsAvenue intersection. The quote “wedon’t do walls in Arlington” is takenout of context, the full statement being“except in the case of an 18th-centu-ry farm house, appropriately sur-rounded by its stone wall, we don’t dowalls in Arlington.” Every member ofthe Redevelopment Board expressedunhappiness with the overly denseproposal, with its minimal setbacksand traffic issues.

Collins then said at a Redevelop-ment Board hearing he’d do a singlebuilding “that would rival the Rob-bins Library in magnificence” if onlyhe could exceed the height limitationsby a few feet. I wrote his attorney stat-ing my concern that such a buildingnot overshadow the adjacent historicchurch. I never mentioned a courtchallenge, and as I am not an abutterto the premises, I would not havestanding. Collins and his attorneychose to imagine this “threat of liti-gation” in order to justify cramming,“by right,” double family houses, eachcheek-by-jowl with its neighbor, onthe site, thereby avoiding the afford-able housing requirement of ourinclusionary zoning bylaw.

Anyone who looks at the statisticswould agree that Arlington has doneits share, and then some, in accom-modating population density. Ourzoning bylaw allows between 17 and79 units per acre depending on thedistrict; single and two-family housescan be built on lots as small as 6,000square feet. Does anyone really thinkit’s evil or selfish for the people of aneighborhood, or a town, to want toretain a little open space, have recre-ational areas for young and old, pre-serve a few remnants of the past, andnot have their neighborhoods over-whelmed with out-of-scale apartmentblocks and the extra automobiles suchdevelopments would bring to theirnarrow side streets?

John L. Worden IIIArlington

correspondence

S P R I N G 2006 CommonWealth 9

• Do you wonder how families are coping with the rising cost of college?

• Do you want to know more about college affordability?

• Are you worried about paying for college?

Then, check out the new MassINC research report:

Paying for College: The Rising Cost of Higher Education

Paying for

CollegeThe Rising Cost of

Higher Education

IT’S AVAILABLE FOR FREE ON MASSINC’S WEBSITE WWW.MASSINC.ORG

10 CommonWealth S P R I N G 2006

publisher’s note

CW comes of agewinston churchill said, “History will be kind to mebecause I intend to write it.” In much the same vein, I intend,on the occasion of CommonWealth’s 10th anniversary issue,to say a few admittedly biased words of praise for the mag-azine I am proud to publish, and especially the team thatputs it together four (and occasionally five) times a year, ledby our very talented editor, Robert Keough.

CommonWealth is unique. It is the only magazine of itssort anywhere. There are, in some other states, magazineson state government, on tourism, and on business matters,though these are shrinking in number, even as magazines onshopping,wealth,and celebrity proliferate.California Journalgave up publication in January 2005 after 35 years.New JerseyReporter recently resumed publication after a yearlong hia-tus. But even at their best, none of these other magazines hasthe editorial ambition of CommonWealth, which is to be notjust a trade journal of state government but rather a journal-istic forum for exploring the dilemmas and possibilities ofcivic life. And none draws the same community support inthe form of sponsorship. More than 100 sponsors and over125 major individual donors (our Citizens Circle) providematerial support to the magazine and to MassINC. Thisbreadth of support is a strength that grows by the day.

In each issue,our editors grapple with a big challenge: howto enliven and elucidate the politics, ideas, and civic realitiesof our state. From Robert David Sullivan’s novel analyses, in2002 and again this issue, of the 10 states of Massachusettspolitics—a franchise he has taken national with the acclaim-ed Beyond Red & Blue series, still available (and still draw-ing traffic) on www.massinc.org—to Michael Jonas’s in-depthreporting on such meaty topics as the future of health care,the middle-class housing squeeze, and the challenges of mi-nority political leadership, CommonWealth does somethingno other publication does, in each and every issue.

And I am pleased that we were able to add staff writerGabrielle Gurley to the CommonWealth masthead. She hasalready produced for the magazine two outstanding profilesof public-agency managers even as she manages the Issue-Source.org Web site, maintained in partnership with StateHouse News Service, on a daily basis.

I am especially proud of the thorough treatment the ed-itors gave to both health care and growth & development intwo full-length extra issues produced in the last two years. Inboth cases, CommonWealth’s reputation for fairness, depth,balance, and insight attracted broad-based consortia to un-derwrite the special issues. In both cases, we had labor andbusiness leaders and the full spectrum of interest groups atthe table as sponsors.That these backers would put their faithin a journalistic venture over which they had no control isa testament to the quality of CommonWealth’s journalism.

But what I like the most about CommonWealth is whatI learn from it every issue. It’s not light reading, I will admit.But it is unfailingly thoughtful and insightful. Every issue isa crash course in civics,Massachusetts-style, something that’sincreasingly hard to come by—in print, on the air, or on theWeb. In today’s world, the profusion of information andproliferation of opinion make balanced, thoughtful sourcesof news and analysis ever more precious. CommonWealthmeets that ever-growing need.

Being publisher, I’ve found, is like being the owner of abrand-new car, but riding in the back seat as it barrels downthe highway. You don’t quite know where your drivers aretaking you, but you have faith—and hope for the best. Formy part, I have full confidence in my drivers, and I’m glad tobe along for the ride. Serving as publisher of this still-youngmagazine is a joy and a privilege.

It’s also a joy to present to you CommonWealth’s new look—full color throughout, with a striking new design, devel-oped entirely in-house under the leadership of art directorHeather Hartshorn, and with advice and input from manyfriends and advisors. I hope it pleases our readers, and oursponsors, as much as it pleases me.

As for history, I’m sure it will be kind to CommonWealth,whether I write it or not.

ian bowles, publisher

Other magazines like itdon’t have its ambitionor its breadth of support.

S P R I N G 2006 CommonWealth 11

This year, MassINC turns 10.To mark this milestone, MassINC is taking on a new set of initiatives to put the opportunityand challenge of living the American Dream in Massachusetts into the civic spotlight in2006. Our initiatives are being supported by a special 10th Anniversary Fund.

We would like to acknowledge the individuals, organizations, foundations and companiesthat have made early pledges to help us build our Fund. Everyone at MassINC thanks themfor their generosity, civic leadership and commitment to building a new Commonwealth.

$50,000 and above

Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts The Boston Foundation Nellie Mae Education Foundation

$25,000 – $49,999

Anonymous Rick and Nonnie Burnes Citizens BankFidelity InvestmentsBruce Herzfelder and Ellen Roy HerzfelderLiberty Mutual New Community Fund

$10,000 – $24,999

Neil and Martha Chayet Maurice & Carol Feinberg Family Foundation Chris and Hilary GabrieliHarold HestnesHouseworks LLC & Alan SolomontKeyspan Mellon New England Mitchell KertzmanGloria and Allen Larson The MENTOR NetworkMonitor GroupSavings Bank Life InsuranceState Street Bank and Trust Company David Weinstein

$5,000 – $9,999

Heather and Charles Campion Children’s Hospital BostonDenterlein Worldwide William Gallagher AssociatesArnold Hiatt Philip and Sandy Gordon MassHousing Partners HealthCarePaul and Barbara Levy NAIOP, Massachusetts ChapterSchrafft Charitable Trust

$1,000 – $4,999

Bob Fraser IBM Jeffrey JonesRJ Lyman Peter Meade and Roseanne Bacon Meade Mellon New England Pam Murray Ellen Remmer and Chris Fox Mark and Sarah RobinsonHelen Spaulding

M A S S I N C 1 0 T H A N N I V E R S A RY F U N D D O N O R S

12 CommonWealth S P R I N G 2006

The security of our Commonwealth.

The safety of our neighborhoods.

Our ability to pursue the American

dream without fear for personal safety.

Liberty Mutual is proud to work together with MassINC’s Safe Neighborhoods

Initiative. Helping people live safer, more secure lives is what we do best.

© 2006 Liberty Mutual Group

S P R I N G 2006 CommonWealth 13

civic sense

Re-readingCommonWealthby robert keough

originally, i planned to treat the 10th anniversary of themagazine as an excuse to re-read—and,I must confess,whenit comes to some older issues and articles, read for the firsttime—the collected works of CommonWealth. But as dead-line approached, it became evident that wasn’t going tohappen. The 44 issues of CW published to date measurenearly a foot and a half on the bookshelf, and with each issuecontaining up to 50,000 words (this one has 56,700,but don’tlet that intimidate you), a straight read-through was out ofthe question. But as editor for all but 16 of those issues, anda contributor since the third, I think I can comment on whatMassachusetts has looked like over the past 10 years throughthe CW lens, even without a word-by-word refresher.

I’m the first to admit that anyone using CommonWealthas sole source might get a distorted view of what took placehere over our first full decade. Many of the events and em-barrassments that dominated headlines in those years getmentioned only in passing, if at all. That’s because CW wasnot conceived as a quarterly synopsis of current events, noras a running commentary on them. While not indifferentto the news of the day, CommonWealth aims to explore in abroader, but also more consistent, way the challenges ofliving up to the designation Massachusetts goes by in placeof “state”—that is, “commonwealth.”

In the very first Civic Sense essay, in the Spring ’96 de-but issue, founding editor Dave Denison wrote at lengthabout the notion of “commonwealth” that has its roots inPuritan Massachusetts but provides civic inspiration eventoday. In the preamble to the state Constitution, written byJohn Adams, the “body politic” of the Bay State is definedas “a social compact, by which the whole people covenantswith each citizen,and each citizen with the whole people, thatall shall be governed by certain laws for the common good.”

“In 200 years of economic and political history the veryidea of ‘the common good’ has fallen upon many tensions,”observed Denison.“And the notion that government is thenatural guarantor of our common interests is today verymuch taken for granted and at the same time called cyni-

cally into question.”But he also noted “a quiet revival of cer-tain intellectual traditions that may lead us to a new con-sideration of the idea of commonwealth,” including newthinking about “civil society” as a realm of citizen activityoutside of formal government that could impact both pol-itics and the economy. “If theorists tell us that more civic activity not only will revitalize democratic government butlead to better economic development,”concluded Denison,“that is an idea worth pursuing.”

For 10 years now, CommonWealth has pursued that idea,

recognizing that the “common good”has both civic and ma-terial dimensions. Our coverage of politics in Massachusettshas left the food fights to others, and concentrated insteadon what our state’s elected and civic leaders, on their bestdays, are trying to accomplish, based on their conceptionsof the common good.At the same time, CommonWealth hasneither glossed over the sausage-making messiness of gov-erning nor idealized some sort of good-government utopi-anism. CW has sounded the alarm on evidence of politicaldysfunction, the effect of which is to depress engagement inthe public realm and encourage retreat into the private.Some examples: Dave Denison’s departing “screed”againstthe deterioration of democracy into two-man rule (“TheLast Harrumph,”CW, Fall ’99), my own plea for Massachu-setts to be a bit less “exceptional”in its bungling of budgetaryand other matters (“Aren’t We Special?” Winter ’02), and associate editor Michael Jonas’s incisive reports on legisla-tive sclerosis (“Beacon Ill,”Fall ’02) and hopes for new lead-ership (“Great Expectations,” Winter ’05).

At the same time, CW has expended as much energy out-side the State House as inside, exploring the nature and vari-ability of Massachusetts civic culture through such vehiclesas associate editor Robert David Sullivan’s mapping of statepolitics (Summer ’02 and the current issue) and his politicalcharacter study “Bay State Nation”(Summer ’04),as well as our

CW has sounded thealarm on evidence ofpolitical dysfunction.

civic sense

14 CommonWealth S P R I N G 2006

regular dispatches from the front lines of self-governmenton the local level, Town Meeting Monitor.

even as we examine the Massachusetts body politic,CommonWealth has been every bit as attentive to the bodyeconomic. After all, any reasonable definition of the “com-mon good”for the individuals and families of the Common-wealth would have to include good jobs, good schools, andgood places to live.

In our first 10 years we have plumbed no topic moredeeply than education reform, which seems to be a never-ending saga. CommonWealth’s treatment has included themagazine’s one and only double issue (Spring/Summer ’97)and its first full-length extra edition (Education ReformExtra ’02),along with scores of other feature stories, Inquiries,State of the States rankings, analytical essays, and Argument& Counterpoints debates on everything from school financeto charter schools. CW’s coverage of education has been aneducation in and of itself, as the often predicted (even by us)train wreck of widespread MCAS-denied diplomas nevermaterialized but, by the same token, academic achievementremains maddeningly gap-ridden even today.

Also consistent have been CW’s warnings of a certain ten-uousness in the means of achieving and maintaining a mid-dle-class existence. Such status is an American state of grace,the material basis not only for the Jeffersonian “pursuit ofhappiness” but for a civic life not distorted by desperationand want.

In 1996, 2001, and again this issue, CommonWealth trav-eled to Heritage Road in Billerica to check the heartbeat ofthe suburban middle class, and each time found it strong butirregular. Massachusetts has not been, and is not today, lack-ing in opportunity. But the basis of economic security hasbeen steadily eroding, making the Holy Grail of middle-classcomfort not only more elusive for those striving for it butmore fragile for those who have attained it.

This is perhaps surprising, given that CommonWealth be-gan publication at a time when Massachusetts was on a re-assuring upswing from one of its deepest economic shocks,complete with job losses, bank failures, and home foreclo-sures. By 1996, the Bay State high-tech sector had gotten “itsgroove back,” in the words of a Winter ’98 article, and washeaded toward an economic run-up that would soon be theenvy of the nation (even if no one dared to invoke the word“miracle”this time around). By the turn of the millennium,Massachusetts incomes were among the highest in the na-tion, and unemployment, at less than 3 percent, was amongthe lowest. Then the bubble burst, and we discovered, muchto our dismay, that the New Economy acted very much likethe Old Economy: What went up did come down.

More fundamentally, the economy Massachusetts de-pended on was becoming less stable even as it became more

This is what social change looks like.

Visit our website to learn more about AARP Massachusetts.

At www.aarp.org/ma you will find articlesrelated to Medicare Rx, Social Security,AARP Tax-Aide, mature workers and healthcare. We also provide up-to-the-minute webannouncements about legislative issuesimportant to Massachusetts residents.

To learn more about AARP Massachusetts’involvement in advocacy, community serviceand state happenings, visit www.aarp.org/mafor the latest information.

Call us at 1- 866 -448-3621 orvisit our website at www.aarp.org/ma.

civic sense

S P R I N G 2006 CommonWealth 15

dynamic. Jobs in our most forward-looking economic sec-tors—technology, financial services—looked less and lesslike the lifetime-employment, full-benefits Rocks of Gibraltarof an earlier era. Rather, these jobs were subject to stock-market volatility (“The New Economy’s Dubious Dividend,”Spring ’02), global competition (“Offshore Leave,”Summer

’04), and what might be called the deinstitutionalization ofemployment, as competition, corporate restructuring, tech-nology, and lifestyle changes made for the growth of inde-pendent contractors and other free-agent workers (“LoneRangers,”Summer ’05). Even traditional employees came tocarry more of the burden of health insurance and retirementsavings. Only health care, with its firm institutional base inhospitals, looked anything like a traditional employer, andfor all its promise as an economic engine of the future, thelife-sciences industry threatened to be as much a drag ongrowth as a boon, given the costs health care inflation im-poses on other industries (See “Prognosis: Anticipation and

Anxiety,” Health Care Extra 2004).Meanwhile, cost of living became an ever-bigger challenge

to middle-class life in Massachusetts. The price of housing,in particular, emerged as a threat to our economic future,as municipal self-interest impeded the development ofmodest-priced homes. The effects fell hardest on youngfamilies (“Anti-family Values,” Spring ’02), who began tovote with their feet (“Moving In or Moving On?” Winter’04). The state responded with “smart growth” policiesaimed at spurring housing development in an environ-mentally sensitive way, but they have been slow to take hold(“House Rules,” Growth & Development Extra ’06). It alladds up to a Massachusetts version of that 1970s economicanomaly, stagflation: sluggish job growth, declining popu-lation, yet precious goods priced out of reach.

Not a pretty picture, but it’s one that reinforces the real-ity that “commonwealth” is not just a state of being but anideal to strive for. In both civics and economics, the socialcompact binding the residents of Massachusetts together for the common good is subject to constant renegotiation.As we head into our second decade, you can count onCommonWealth to subject the shifting terms of that com-pact to the closest scrutiny. That will be our contribution tothe Commonwealth living up to its name.

‘Commonwealth’ is notjust a state of being but

an ideal to strive for.

Viewfrom the

CornerOffice

Former governors on the

American Dream in Massachusetts

View from the

Corner Office:

Come celebrate MassINC and CommonWealth Magazine’s 10th Anniversary by

attending a panel discussion with Governors Cellucci, Dukakis, King, Swift, and Weld.

thursday may 25, 2006 • 4 to 6pm • faneuil hall, boston, ma

reception to follow at quincy market

For more information, please contact Emily Wood at 617-224-1709

Supported by the MassINC 10th Anniversary Fund

16 CommonWealth S P R I N G 2006

Bank of America, N.A. Member FDIC.

©2004 Bank of America Corporation.

We live here. We work here. We play here, too. That’s why Bank of America is

committed to giving more back to the community we share, the community we

all call home.

Visit us at www.bankofamerica.com.

We have personal We have personal reasons for giving back reasons for giving back to our community.to our community.

SPN-42-AD

STATE GRADES FROM QUALITY COUNTS 2006

Source: Quality Counts 2006, from Editorial Projects in Education, publisher of Education Week (www.edweek.org) *Hawaii has a single school district for the entire state and is not counted in this category.

S P R I N G 2006 CommonWealth 17

massachusetts is about as good as it gets when it comesto setting standards for public school teachers and holdingschools accountable for outcomes, according to QualityCounts 2006, the latest annual report compiled by Educa-tion Week. The report’s editors gave the Bay State an “A” inthose areas, the same grade as last year, citing academicstandards that are “clear, specific, and grounded in content”(as determined by the American Federation of Teachers),and approving the two-pronged strategy of using bothsanctions and additional aid in dealing with low-performing schools.

In other areas of education, the Bay State was closer tothe national norm. It got a “C”for “efforts to improve teacher

equality,” along with ascolding for its lack ofmentoring programsfor new teachers and itsinadequate funding ofprofessional develop-ment programs. Worse

was a “C-” for “resource equity,” thanks to wide disparitiesin per-pupil funding among school districts. For “school cli-mate,” Massachusetts got high marks for providing choicesto students and parents (in particular, through the avail-ability of charter schools) but lost some ground on schoolsafety, for an overall grade of “B-”. That was the only changein the four major grades since the 2005 report, when the statereceived a “C+” for school climate and was criticized by thereport’s authors for not doing enough to reduce class sizes.

While not providing a letter grade in student achieve-ment, Quality Counts did include a good amount of data inthat area. For example, at an even 70 percent, the 2002 highschool graduation rate in Massachusetts was virtually iden-tical to the national rate (69.4 percent), but there were no-ticeable differences within two ethnic groups: The gradua-tion rate was 66 percent among Asian-American students inMassachusetts, versus 78 percent nationally, and 42 percentamong Hispanic students, versus 55 percent nationally.(Graduation rates of 55 percent among black students and75 percent among white students lined up pretty closely withrates at the national level.)

state of the states

Grading the graders by robert david sullivan

ALABAMA B B C - C +ALASKA C - D D + D +ARIZONA B D C + D +ARKANSAS C + A - C + B -CALIFORNIA B + B - C B -COLORADO B C B C -CONNECTICUT B - A - B - CDELAWARE B + C + B B -FLORIDA A C C B -GEORGIA A - C + C + CHAWAII B + C - C *IDAHO B D C + FILLINOIS B + C C + D +INDIANA A B - C B -IOWA F C + B - B +KANSAS C B + B - C +KENTUCKY B + B C CLOUISIANA A A C - BMAINE C D B C -MARYLAND A - C + D + C -MASSACHUSETTS A C B - C -MICHIGAN B D C - C -MINNESOTA C + C B BMISSISSIPPI C + C D + C -MISSOURI D + B - B CMONTANA D D + C - D -NEBRASKA D C C + C +NEVADA B - C C - A -NEW HAMPSHIRE C C - B - DNEW JERSEY B + B B - C -NEW MEXICO A B C B +NEW YORK A B - C CNORTH CAROLINA B B C + C -NORTH DAKOTA C - D + C D -OHIO A - B C + COKLAHOMA B + B C + B -OREGON C + D C + C -PENNSYLVANIA B - B C C -RHODE ISLAND C C - B DSOUTH CAROLINA A A C + CSOUTH DAKOTA B - D + C + C +TENNESSEE B C + C + CTEXAS B - C - C C -UTAH C + C - C B +VERMONT B - C - B - FVIRGINIA B B + C D +WASHINGTON B C C + CWEST VIRGINIA A B C + BWISCONSIN B - C + B B -WYOMING D D + B C +

STANDARDS IMPROVING AND TEACHER SCHOOL RESOURCE

STATE ACCOUNTABILITY QUALITY CLIMATE EQUITY

‘Clear, specific’school standardsearned the state

a gold star.

18 CommonWealth S P R I N G 2006

www.naiopma.org

National Association of Industrial and Office PropertiesMassachusetts Chapter

144 Gould Street, Needham, MA 02494781-453-6900 • Fax 781-292-1089

email: [email protected]

Making Informed Decisions is what

growing your business is all about.

It can be tough to keep up with the latest events and trends in

the commercial real estate world.And you’re either in the know,

or out of it.

As a member of NAIOP, youreceive highly effective legislative

advocacy and access to a limitlessresource of contacts and insideinformation you just can’t get

anywhere else.

From networking opportunities toeducational programs and strong

public affairs, NAIOP offers you achance to focus on your businesswith the critical information youneed to make intelligent choices.

For more information, visit ourwebsite at www.naiopma.org,

or call 781-453-6900.

NAIOPLeading the Way

head count

Constituent service by robert david sullivan

Fewer than 1,5001,500 to 3,0003,000 to 6,000More than 6,000

PLYMOUTH

EVERETT

NUMBER OF RESIDENTS PER MUNICIPAL POLICY-MAKER**City councilors, city aldermen, or town selectmen

AREA OF DETAIL

Sources: Massachusetts Municipal Association (www.mma.org); Massachusetts Election Statistics 2004.

S P R I N G 2006 CommonWealth 19

one effect of the ongoing shift in population from city tosuburb is that more and more town selectmen in Massa-chusetts have constituencies that dwarf that of city coun-cilors. The Bay State’s largest town, Framingham (popula-tion 65,598), has regular town meetings but is otherwisegoverned by five selectmen,or one for every 13,000 residents.That’s a higher ratio than in 48 of the 51 communities witha city form of government—the only exceptions beingBoston, Worcester, and Springfield.

In North Adams, the state’s smallest city (population14,167), there are nine councilors, or one for every 1,600 res-idents. There, a sharp drop in population has helped bringcitizens closer to their representatives: In 1940, there was onecouncilor for every 2,500 residents.

Larger constituencies may mean lower voter turnout.In the town elections of 2004, the last year for which state-compiled figures are available, the median turnout among300 municipalities was 24 percent. But the five largest com-

munities that have stuck with town government recordedturnouts near or well below that figure: Framingham (11percent), Brookline (17 percent), Plymouth (25 percent),Arlington (12 percent), and Billerica (20 percent). In the five smallest towns that have five-member boards of se-lectmen (as opposed to the state-mandated minimum ofthree), turnout was noticeably higher: Truro (34 percent),Wellfleet (35 percent), Millville (40 percent), Provincetown(36 percent), and Oak Bluffs (47 percent).

The number of representatives may be a factor in cityelections as well. Everett has by far the biggest legislativebranch in the state—consisting of 18 city councilors and a second chamber of seven aldermen—and logged an impressive turnout of about 49 percent in November 2005.But in Lawrence, which has a nine-person city council buta population almost double that of Everett, turnout was only about 30 percent, even though both cities had hotlycontested mayoral races that year.

FRAMINGHAMNORTH ADAMS

MILLVILLE

global soul mates We usually compare Massachusetts with other states, but there’s a wholeworld out there to search for possible doppelgängers. According to the 2006World Almanac, Massachusetts matches up almost exactly with Paraguayfor total population (about 6.4 million), El Salvador for population den-sity (820 people per square mile), Serbia/Montenegro for birth rate (12.1per 1,000 women each year), Belgium for infant mortality (4.7 per 1,000births), and Egypt for gross state or national product ($320 billion).

It’s tougher to find a country that resembles Massachusetts in themake-up of its workforce, which has advanced beyond—or simply lost—agricultural and manufacturing jobs. Barely more than 10 percent ofthe Bay State’s workers are in those two sectors. Outside of Vatican City,the only nation that comes close to that figure is the Grand Duchy ofLuxembourg, where only 14 percent of its half million people areinvolved with growing or making things.

please your employees with pavement “Onsite parking for employees” is the top factor for companies decidingwhether to locate (or stay) in a particular location, according to RevenueSharing and the Future of the Massachusetts Economy, a recent report by the Massachusetts Municipal Association and Northeastern University’sCenter for Urban and Regional Policy. Authors Barry Bluestone, Alan Clayton-Matthews, and David Soule surveyed 230 industrial and commercial develop-ers across the US, who also ranked the “availability of appropriate labor” in aregion and the “timeliness of approvals/appeals” in a municipality as amongthe most important factors in decision-making. The least important factorwas whether a particular location was subject to a municipal minimum wage law. (State and local tax rates were deemed far more important.) Other low-ranked factors included access to railroads and — sorry, Harvardand MIT — proximity to research institutions and universities.

The authors conclude that local factors can outweigh statewide condi-tions when companies decide where to locate facilities. The choice, they say,is often not between “Massachusetts, North Carolina, and Texas” as much as

between “Worcester, Raleigh–Durham–Chapel Hill, and Austin.”

new bedford’s big haul According to figures released bythe US Commerce Departmentlate last year, New Bedford wasthe most profitable fishing portin the nation in 2004, helped by a 35 percent jump in the sea scal-lop catch. The total value of fishbrought into the port was $207million, up from $176 million theprevious year, and it was the fifthconsecutive year that the dollarfigure increased.

The NOAA Fisheries Service,part of the Commerce Depart-ment, also reported that Ameri-cans ate a record 16.6 pounds offish and shellfish per person in2004, including a record 4.2pounds of shrimp per person. Butwhile the consumption of freshand frozen fish has been steadilyrising, the popularity of cannedtuna has slipped from 3.5 poundsper person in 2000 to 3.3 poundsin 2004. Sorry, Charlie.

20 CommonWealth S P R I N G 2006 ILLUSTRATIONS BY TRAVIS FOSTER

statistically significant

by robert david sullivan

unions rally (but quietly)The Bay State’s shift to a serviceeconomy has generally coincidedwith a drop in union member-ship, but the labor movementhere was able to rebound slightlyin 2005 after three years offalling numbers. According toFebruary data from the USBureau of Labor Statistics,402,000 workers, or 13.9 per-cent of the state’s workforce,belonged to unions last year,up from 393,000 people, or 13.5 percent, in 2004. That putMassachusetts in 19th placeamong all states in union mem-bership. Rhode Island was firstamong New England states, butits rate fell last year from 16.3percent to 15.9 percent. Nation-ally, the most unionized statewas New York (26.1 percent,up from 25.3 percent), and lastplace goes to South Carolina(2.3 percent, even lower than its 2004 rate of 3.0 percent).

nothing tops pizzaNew figures from the Census Bureau also confirm the popularity of seafood in the US. As of 2002, there were 0.48 restaurants that primarily served seafood for every 10,000 people,compared with 0.33 steakhouses for the same group. Unsurprisingly, the gap was larger inMassachusetts, where there were 1.04 seafood restaurants and 0.21 steakhouses for every10,000 people. Among ethnic cuisines, Mexican was the most popular nationwide (1.01 forevery 10,000 people, compared with 0.38 in Massachusetts), but Chinese was first in the Bay State (2.25 for every 10,000 people, compared with 0.99 in the US). But pizzerias werecommon everywhere: 1.45 per 10,000 people nationally and 1.91 for the same group inMassachusetts.

Overall, there were 13.29 “full-” or “limited-service” restaurants for every 10,000 people in the US, or one for every 753 potential diners. Bay Staters either eat out more or prefersmaller places, as there are almost exactly 15 restaurants for every 10,000 people, or one forevery 667 diners.

get me stats — stat!Massachusetts is sec-ond only to California intreating and preventingemergency health situa-tions, according to a Januaryreport by the American College ofEmergency Physicians. With an overall grade of “B”, the Bay State scoredhighly in the number of physicians and nurses per capita, as well as ininjury-prevention programs and immunization efforts. Mandatory helmet use for motorcyclists also got a thumbs up. But the state gota “D-” in the category of “medical liability,” thanks to what the ACEP considers too high a cap on non-economic damages in malpractice suits.It also came out below average in the number of emergency departmentsand trauma centers per capita.

Every state in the Northeast was in the top half of ACEP’s rankings,though New Hampshire barely made it at 25th place, with low numbersof hospital beds and emergency physicians relative to its population. (Itslibertarian stance on motorcycle helmets — use them if you want — alsogot the Granite State a demerit.) Arkansas, Idaho, and Utah were at thebottom of the 50 states.

S P R I N G 2006 CommonWealth 21

22 CommonWealth S P R I N G 2006

Empowering youth to take charge of their future . . .

and make their dreams a reality.

Mellon CityACCESS* creates meaningful

work apprenticeships for high school students at

non-profit organizations in and around Boston.

At Mellon New England we’ve long been committed

to the communities we serve and through our

Mellon CityACCESS program we are working to enrich

the quality of life for young people in our community.

www.mellon.com ©2006 Mellon Financial Corporation

*Mellon CityAccess

An Investment in Youth

Funded by the

Arthur F. Blanchard Trust

S P R I N G 2006 CommonWealth 23

Can review panel bringorder to pension chaos?> by m i c h a e l j o n a s

when he was fired three years ago as the state’s correction commissioner,Michael Maloney stood ready to take his medicine—but hoped for a little sugarto help it go down. Maloney, who was ousted in the wake of the controversyover the prison killing of defrocked priest John Geoghan, sought to be placedin the same retirement category as corrections officers and other front-line pub-lic safety officials, a change that would have increased his annual pension pay-out from $41,000 to more than $82,000, according to a Boston Globe accountat the time. The state retirement board turned Maloney down, but his requestcast a spotlight on the case-by-case way in which individuals and groups ofemployees sometimes get favored pension status.

“Confusion is the only way to react to a system that has no logic to it what-soever,”says state Rep. Jay Kaufman, a Lexington Democrat who is House chair-man of the Legislature’s Joint Committee on Public Service. As many as 200bills are referred to the committee each session petitioning to have an individualposition or group of workers moved up, by statute, in the state’s four-tier sys-tem for classifying retirement benefits. Meanwhile, the state retirement board

reviews 30 to 50 applications a monthfrom workers asking to be assigned to ahigher pension group administratively.

Hoping to tame a retirement-classifi-cation beast that has fed for decades offpolitical influence, Kaufman and his pub-lic service committee colleagues in March

appointed a blue-ribbon panel of outside experts to recommend reforms tothe retirement classification system.

The rationale behind the tiered system is that those in more hazardous occupations should be able to retire earlier with full pensions than those inlower categories. But over the years, the statute that defines who falls into thehighest categories has come to look like a Christmas tree, loaded up with moreand more job titles.

Among those at one time added to the second tier, whose members can re-tire five years earlier than those in the first tier at the same level of pension ben-efits, were all employees of Cushing Hospital, a now-shuttered state facility inBrockton. The highest pension category, Group 4, includes, along with vari-ous public safety officials, “licensed electricians” at the Massachusetts PortAuthority, along with a handful of other Massport trades. The long list of Group4 jobs also includes “the conservation officer of the city of Haverhill.”A Group4 classification allows workers to retire 10 years earlier than those in Group 1

kaufman: thetiered system‘has no logic toit whatsoever.’

No charter schoolto be left behindCharter schools burst onto the scene as a bold challenge to the status quo.Supporters said that charters — whichare publicly funded but operate free ofbureaucratic and contractual constraints— would blaze a trail of innovation andserve as models for failing district schools.But what happens when charter schoolsare themselves failing?

Until now, it’s been sink or swim,with the state Department of Educationsticking to its role as authorizing agent.DOE approves new charter schools andreviews them every five years,with char-ters revoked from those judged to benot making the grade.

But after a year in which DOE revokedcharters from two schools and found itself pulled into an ugly internecine bat-tle over school leadership at a third (see“In Need of a Renaissance,”CW,Fall ’05),state education officials are laying plansfor a new office to aid troubled charterschools.

The blueprint for a “MassachusettsCharter School Technical Assistance andResource Center,”outlined in a recent re-port commissioned by DOE, calls for amix of public and private funding for acenter to help charters with everythingfrom governance and school operationsto facilities planning.

Charter supporters say the schoolsneed these sorts of resources,which dis-trict schools get from their local schooldepartments.Critics are likely to see themove as a bulking up of bureaucracy,aimed at helping schools that claimedthey would thrive if only freed from suchnettlesome strictures.

> m i c h a e l j o n a s

inquiries

inquiries

24 CommonWealth S P R I N G 2006 PHOTO BY MEGHAN MOORE

at the same level of pension benefits.“It’s nuts. It’s no way to run a railroad,” says Alan Mac-

donald, executive director of the Massachusetts BusinessRoundtable and a member of the special review panel.“Frankly, if you happen to have an influential legislator onyour side, you’re likely to be able to make the switch.”

Alicia Munnell, director of the Center for RetirementResearch at Boston College and chairman of the special pen-sion panel, says even the premise of favorable retirementbenefits for more hazardous jobs may be ripe for review. Thepromise of reward in retirement may “inhibit movement inand out” of these jobs, impeding career advancement, saysMunnell, a former member of the President’s Council ofEconomic Advisors. Higher pay during the working yearsmight be a more appropriate reward, she says.

Pensions are a touchy subject in the public sector, whererich benefits are often seen as compensating for modest payscales. That makes pensions a “potential third-rail issue,”says Macdonald. Kaufman describes union leaders as “understandably at least attentive, if not nervous,”about theclassification review.

But one union official says changes would be welcomeif they leveled the pension paying field.“An evaluation of thegroup classification system is long overdue,”says Jim Durkin,a spokesman for AFSCME Council 93, which has about35,000 members in Massachusetts.“Dealing with inequitiesin the system through hundreds of petitions each legislative

session has clearly proven to be problematic.”“My whole life is devoted to making sure people have

secure retirements, so we’re not out to hurt people,” saysMunnell, a nationally recognized expert on retirement issues.“But we want a system that will stand up scrutiny.”

But it will be the recommendations of the eight-memberpanel, due June 15, that first undergo scrutiny.Any changesin the retirement system will have to pass muster with law-makers who have shown little appetite for tinkering withpublic-employee perks.

“Could this be a hard sell?” asks Kaufman. “Yes.”

Reentry plan forex-offenders stilllooking for entrée> by m i c h a e l j o n a s

a new yorker cartoon captured the problem succinctly.It showed a prison cellblock with a large banner hangingoverhead: WELCOME BACK, RECIDIVISTS!

According to a 2002 report by the MassachusettsSentencing Commission, 49 percent of those released fromstate and county correctional facilities commit a new offensewithin one year, a figure that is in line with national recidi-vism rates.“Incarceration works—until you let people out,”says Lt. Gov. Kerry Healey.

So the search is on for ways to break the revolving-doorsyndrome of offenders going in and out of prison.One strat-egy gaining favor here is to require a mandatory period ofsupervision for every offender released from incarceration.But that doesn’t mean the idea is gaining traction.

Of the 17,000 inmates let out of Massachusetts jails andprisons each year, nearly half have no mandated post-releasesupervision. One reason is tougher sentencing laws that of-ten allow little room for parole. And as a 2002 MassINCstudy, From Cell to Street, pointed out, an increasing num-ber of prisoners who are eligible for parole opt to competetheir full sentences rather than apply for it—making surethey leave prison with no ongoing oversight.

“It’s beyond ironic, it is madness, that we allow peopleto determine themselves whether they are supervised whenthey get out,”Jeremy Travis, the president of John Jay Collegeof Criminal Justice in New York and a leading authority onprison reentry, told CommonWealth last year (“ApproachingReentry,” CW, Summer ’05).

In February 2005 the Romney administration filed leg-

Panel member Alicia Munnell says even the idea of higherpensions for hazardous jobs may be ripe for review.

islation calling for mandatory post-release supervision of allreleased offenders. The bill would revamp sentencing lawsto include post-release supervision of every inmate for ninemonths or for a period equal to 25 percent of the maximumsentence they received, whichever is longer. Similar legisla-tion has been filed by Democratic state representativesMichael Festa, Barry Finegold, and Marie St. Fleur, whileDemocratic Sen. Cynthia Creem is sponsor of a bill combin-ing post-release supervision with parole eligibility for drugoffenders serving mandatory minimum sentences.

Despite support on both sides of the aisle, however, theidea of expanded post-release supervision seems stuck at thestarting gate. In November, the Legislature’s Joint Com-mittee on the Judiciary heard testimony on the bills. But thecommittee has yet to take action, and there is little prospectof anything happening before the end of formal legislativesessions July 31.

Former attorney general Scott Harshbarger,who resignedin December from a state advisory commission on correc-tions reform, voiced frustration with the failure to move aggressively to implement the top-to-bottom changes thepanel recommended, including mandatory post-release su-pervision of ex-offenders. Harshbarger says the Legislature

has largely “abdicated”responsibility for corrections reform,with House leaders not even filling the two slots on the advisory panel designated for state representatives.

Rep. Eugene O’Flaherty, the House chairman of the judiciary committee, says there may be a good case for post-release supervision of those convicted of violent crimes ordrug offenses, but he’s not sure it is warranted for every

offender. What’s more,though the committeeheard compelling argu-ments in favor of post-release supervision,“what we didn’t hear a

lot of testimony on was the fiscal side of this,” saysO’Flaherty. Nonetheless, the House budget released in Aprilincludes an additional $1 million for prisoner reentry services.

Advocates say reduced recidivism rates would eventuallysave the state money by lowering the population behindbars, where costs per inmate exceed $40,000 a year. But thosesavings, if they materialize at all, would come down theroad, while the bill for an expanded supervision systemwould come due much sooner.

inquiries

S P R I N G 2006 CommonWealth 25

healey: no needfor ‘anothertask force.’

The #1 health plan in America.

Right where you live.

Harvard Pilgrim Health Care is the first health plan in the nation to be rated #1 in both member

satisfaction and clinical quality, according to the National Committee for Quality Assurance (2004).

26 CommonWealth S P R I N G 2006

6 5 0 L A W Y E R S B O S T O N N E W Y O R K W A S H I N G T O N W W W . G O O D W I N P R O C T E R . C O M

Goodwin Procter is proud to serve our local communities and the industries that fuel the economy of Massachusetts —from technology and life sciences to real estate and financial services.

GP057-Tchdwn_7_5x10_5_jc2.indd 1 12/20/05 2:30:56 PM

O’Flaherty says he plans to form a small “work-ing group” representing different facets of the criminal justice community to shape a post-releasesupervision bill that could be taken up next session.But Healey says the time for that has come and gone.

“This bill was filed over a year ago as a result ofover a year of work where all the key stakeholdersfrom the criminal justice world were in place,” saysHealey.“Another task force to look at this is proba-bly not necessary. Now is the time to move forward.”

“We know what works,”says Harshbarger.“Whatwe lack is the political will.”

Political will may well be lacking, but there arealso questions about what does work. A 2005 studyby the Urban Institute found little difference in re-cidivism rates among those released under paroleversus those with no post-release supervision.

Leslie Walker, executive director of Massachusetts Cor-rectional Legal Services, says she is not surprised.With cor-rections spending already approaching $1 billion, Walkerthinks post-release supervision would be throwing “goodmoney after bad”unless it’s part of a broader set of reforms,including intensive education and job training within pris-ons, plus help in navigating the employment hurdles ex-offenders face because of their criminal records.

“Those two things would be much more helpful to re-cidivism than following these guys around who get dumpedon the street with a $50 check and no skills,” she says.

Still, if lawmakers are not jumping on the bandwagon forpost-release supervision, an approach with a considerablepublic safety component, it’s hard to imagine mustering the“political will” for a more ambitious reentry agenda.

In Fitchburg, an arts pilot school takes off but may hit turbulence> by ga b r i e l l e g u r l e y

would you lend ancient Chinese masterpieces to a mid-dle school? Maybe not, but the Sackler Foundation didn’tblink before sending 33 priceless artifacts, among themChinese Buddhas and tomb figures dating from 2000 BC,for use at Fitchburg’s Museum Partnership School.

“We think that’s a unique situation,” says Roger Dell,education director at the Fitchburg Art Museum, which hasbeen affiliated with the public arts magnet school since itopened in 1995.

The long-term loan by the renowned New York City–based Asian art collection made in August 2005 was just an-other milestone for the Museum Partnership School. TheFitchburg middle school was already the only one outsidethe Big Apple to participate in the Lincoln Center’s FocusSchools Collaborative. Under this program, Fitchburg teach-ers train in New York, then invite a dance, music, or theatergroup affiliated with the center to perform back home.

“Unique”is the watchword again this fall, as the school—along with the Fitchburg Public Schools district—becomesthe first outside of Boston to adopt the pilot school model.

First established in Boston in 1995, pilot schools are pub-lic schools that get charter school–like management auton-omy, but remain part of a local school district, with the bless-ing of the local teachers’ union. At least, that was the case inBoston until 2004, when Boston Teachers Union presidentRichard Stutman blocked the conversion of Allston’s Gard-ner Elementary School to pilot status, despite approval fromthe school’s teachers. After protracted negotiations, whichresulted in limits to how many hours pilot-school teacherscould work, even voluntarily, without additional compen-sation, the public schools, the teachers’ union, and city of-ficials agreed in February to open seven new pilot schoolsby 2009, including one that the teachers’union will run sansprincipal, a Massachusetts first.

“The pilot idea really came from teachers themselves.This is not a top-down reform that was imposed on resistantfaculty or unions,”says Paul Grogan, president of the BostonFoundation. “It was really a tremendous process of coop-eration and thinking that led to this in the mid ’90s, and nowit may have the opportunity to reach its full potential.”

Now that’s true in Fitchburg as well as Boston. FitchburgSuperintendent of Schools Andre Ravenelle says the schooldistrict, the teachers’ union, and the art museum wanted toformalize the their relationship and give the school more in-

inquiries

S P R I N G 2006 CommonWealth 27PHOTO BY MEGHAN MOORE

The Fitchburg Art Museum’s Roger Dell inspects an itemloaned from the SacklerFoundation.

GP057-Tchdwn_7_5x10_5_jc2.indd 1 12/20/05 2:30:56 PM

28 CommonWealth S P R I N G 2006

This year, more than 720 non-traditional adult learners who face barriers to academic success will have an opportunity to earn a college degree.

Through the New England ABE-to-College Transition Project, GED graduates and adult diploma recipi-ents can enroll at one of 25 participating adult learning centers located across New England to take freecollege preparation courses and receive educational and career planning counseling.They leave the pro-gram with improved academic and study skills, such as writing basic research papers and taking effectivenotes. Best of all, they can register at one of 30 colleges and universities that partner with the program.

Each year, the Project exceeds its goals: 60 percent complete the program; and 75 percent of these graduates go on to college.

By linking Adult Basic Education to post-secondary education, the New England ABE-to-College TransitionProject gives non-traditional adult learners a chance to enrich their own and their families’ lives.

To learn more, contact Jessica Spohn, Project Director, New England Literacy Resource Center, at (617) 482-9485, ext. 513, or through e-mail at [email protected]. (The Project is funded by the NellieMae Education Foundation through the LiFELiNE initiative.)

1250 Hancock Street, Suite 205N • Quincy, MA 02169-4331Tel. 781-348-4200 • Fax 781-348-4299