Case HistoryINotes et dossiers de recherche Scurvy and Canadian Exploration* C. STUART HOUSTON The Canadian scurvy story begins over 450 years ago with Jacques Cartier, whose ships were imprisoned in the ice near Stadacona (pres- ent Quebec City) during the winter of 1535-36. Jacques Cartier in his "Bref Recit" clearly outlined the symptoms of this disease and its effects, noting that some crew "lost their very substance and their legs became swollen and puffed up while the sinews contracted and turned coal-black and, in some cases, all blotched with drops of purplish blood. Then the disease would creep up to the hips, thighs and shoul- ders, arms and neck. And all the sick had their mouths so tainted and their gums so decayed that the flesh peeled off down to the roots of their teeth while the latter almost all fell out in turn." Cartier and his crew endured this affliction throughout the winter; in all about 75 men died or were given up for dead. By accident in the spring, however, Cartier encountered "a band of natives," and noticed one who had previously suffered similar symptoms, but who now appeared in perfect health. Cartier's account continued: I The captain rejoiced to see Don Agaya well in mind and body for he hoped to learn from him the manner of his cure in order to apply the same treatment and remedy to his own men. As soon as the Indians had drawn near the fort the captain asked Don Agaya how he had been cured. The latter replied he knew of the juice and the dregs of the leaves of a tree which had healed him and was the one and only remedy for all diseases. . . . Don Agaya then sent two squaws to fetch some of that tree and they brought back nine or ten boughs. They told us how to strip off the bark and leaves from the wood, boil them in water, and drink the liquor every other day while placing the dregs on swollen and afflicted legs. This tree, they said, cured all diseases. In their language they call it Ameda.' [Spelling varies: Anneda, Annedda or Hanneda.] C. S. Houston, 863 University Drive, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N OJ8. CBMHIBCHM 1 Volume 7: 1990 1 p. 161-67 https://www.utpjournals.press/doi/pdf/10.3138/cbmh.7.2.161 - Sunday, April 02, 2023 7:09:36 PM - IP Address:27.70.129.20

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

Scurvy and Canadian ExplorationScurvy and Canadian Exploration*

C. STUART HOUSTON

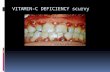

The Canadian scurvy story begins over 450 years ago with Jacques Cartier, whose ships were imprisoned in the ice near Stadacona (pres- ent Quebec City) during the winter of 1535-36. Jacques Cartier in his "Bref Recit" clearly outlined the symptoms of this disease and its effects, noting that some crew "lost their very substance and their legs became swollen and puffed up while the sinews contracted and turned coal-black and, in some cases, all blotched with drops of purplish blood. Then the disease would creep up to the hips, thighs and shoul- ders, arms and neck. And all the sick had their mouths so tainted and their gums so decayed that the flesh peeled off down to the roots of their teeth while the latter almost all fell out in turn."

Cartier and his crew endured this affliction throughout the winter; in all about 75 men died or were given up for dead. By accident in the spring, however, Cartier encountered "a band of natives," and noticed one who had previously suffered similar symptoms, but who now appeared in perfect health. Cartier's account continued:

I The captain rejoiced to see Don Agaya well in mind and body for he hoped to learn from him the manner of his cure in order to apply the same treatment and remedy to his own men. As soon as the Indians had drawn near the fort the captain asked Don Agaya how he had been cured. The latter replied he knew of the juice and the dregs of the leaves of a tree which had healed him and was the one and only remedy for all diseases. . . . Don Agaya then sent two squaws to fetch some of that tree and they brought back nine or ten boughs. They told us how to strip off the bark and leaves from the wood, boil them in water, and drink the liquor every other day while placing the dregs on swollen and afflicted legs. This tree, they said, cured all diseases. In their language they call it Ameda.' [Spelling varies: Anneda, Annedda or Hanneda.]

C. S. Houston, 863 University Drive, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N OJ8.

CBMHIBCHM 1 Volume 7: 1990 1 p. 161-67

h ttp

s: //w

w w

.u tp

jo ur

na ls

.p re

ss /d

oi /p

df /1

0. 31

38 /c

bm h.

7. 2.

16 1

162 C. STUART HOUSTON

Following Don Agaya's advice, cartier and his crew prepared their own decoction and administered it to those men who wished it; all recovered their health.

Cartier's dramatic experience, one of the best-known stories in Canadian medical history, has received the attention of many medical historians and botanists. One question remains. Which tree was it that saved Cartier's men? Fortunately, almost every historian and botanist who has studied the matter has come up with the answer. But perhaps less fortunately, they have come up with different answers!

Which of eleven trees was Cartier's anneda? The Canada Yew, Taxus canadensis, Red Pine, Pinus resinosa, and Red Spruce, Picea rubens, are not strong contenders for the title. The remaining eight trees will be presented in roughly increasing order of probability, listing in turn the authorities who have chosen each tree species.

Sassafras, Sassafras albidum: Hakluyt, 1600;2 Lescarbot, 1609;3 Drum- mond and Wilbraham, 1940.4

Drummond and Wilbraham followed Hakluyt and Lescarbot in choosing Sassafras. Drummond was misled by Dr. J. Gilmour, Assist- ant Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, who assured him that Sassafras oficinale was "native to that part of Canada." Sassafras grows in Canada only in a narrow strip of southern Ontario.

Juniper, Juniperus communis: Rich, 1976;5 Savours and Deacon, 19816 E. E. Rich, the noted historian of the Hudson's Bay Company, chose

"Juniper, Pinette blanche" as the tree that had saved Cartier's men from scurvy. Two errors are involved. Juniper is a shrub that could not possibly fit Cartier's description of "a whole tree as large and tall as any oak in France." Epinette blanche spelled correctly would be the White Spruce, a better candidate. Rich's reputation was such that Savours and Deacon, reputable maritime historians, in their contribution to Sir James Watt's Staming Sailors, repeated Rich's errors verbatim.

I

Eastern Hemlock. Tsuga canadensis: Stewart, 1806;7 Parker, 1928;8 Fen- ton, 1942;9 Macnamara, 1940,1° 1943;" Vogel, 1970.12

Stewart told of the virtues of taking an infusion of hemlock three times daily as an antiscorbutic. Parker, a Seneca Indian and a distin- guished anthropologist, and Fenton chose hemlock as Cartier's anneda. Macnamara claimed that hemlock had more medicinal uses among the Indians than any other conifer infusion.

Balsam Fir. Abies balsamea: Shortt and Doughty, 1914;13 Ihde and Becker, 1971.14

The needles and bark of virtually all evergreens contain potentially curative amounts of Vitamin C,'"ut the Balsam Fir has the highest levels, 270 mg in 100 g of needles.l8

h ttp

s: //w

w w

.u tp

jo ur

na ls

.p re

ss /d

oi /p

df /1

0. 31

38 /c

bm h.

7. 2.

16 1

Scurvy and Canadian Exploration 163

Eastern White Pine, Pinus strobus: ~ ~ v e z a c , 1863;17 Pickering, 1879. ls

D'Avezac's carefully edited Cartier manuscript was the best to that time. The Micmac Indians used White Pine in treating scurvy, accord- ing to Chandler.l9 White Pine is "ohnehta" in the Mohawk language (James Herrick and Don Moerman-personal communication).

Black Spruce, Picea mariana: Millspaugh, 1887;20 Weiner, 1972.21 Black Spruce and Red Spruce were the main sources for the manu-

facture of spruce beer, used by whites as an antiscorbutic and by Indians over two centuries.

White Spruce, Picea glauca: C. S . Rafinesque, 1830;22 Thomas B. Cos- tain, 1954;23 Erichsen-Brown, 1979.24

Erichsen-Brown has compiled the most complete, authentic study of the medicinal use of North American plants. The needles of the White Spruce are the most appetizing to chew. White Spruce is "onnita" in Mohawk and "onnetta" in Onandaga.

Eastern White Cedar. Thuja occidentalis: Thevet, 1568;2s Parkman, 1894;26 Harlow, 1942;27 Rousseau, 1954;28 Hosie, 1979;29 Elias, 1980.30

The White Cedar is the best candidate for Cartier's anneda, as chosen by Th6vet in 1568 and over three centuries later by Francis Parkman, the eminent American Indian historian. The most convincing evidence was collected by Jacques Rousseau, a leading Quebec botanist who methodically assessed the botanical, linguistic, folkloric, and biochem- ical aspects of the problem. Seeds of the Eastern White Cedar were delivered to the royal garden at Fontainebleau during the reign of King Francis I, before 1547. The resulting tree was given the name of arbor vitae-but later generations then appear to have forgotten why it had been given this name!

Those who followed Cartier unfortunately failed to benefit from this I experience. Knowledge can be fleeting. Samuel de Champlain and his

men fared even worse. There were no longer any Indians residing near Quebec City to direct the white men to the appropriate tree. In 1604-05, 35 of Champlain's men died of scurvy at the St. Croix Islands and in the following two winters Champlain lost 12 and 7 men, respectively, at Port RoyaL31 Champlain observed that scurvy could be avoided by "good bread and fresh meat."32 The new settlements in Quebec con- tinued to be ravaged by scurvy for another 25 years.33

Indians and those fur traders whose diet included fresh meat were free from scurvy throughout most of North Ameri~a.~" However, the sailors who explored Hudson Bay in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries had varying degrees of difficulty from scurvy. Jens Munk lost 62 of his party of 65, nearly all from scurvy, while wintering at Church- ill in 1619-20. Munk and the other two survivors sucked the roots of

h ttp

s: //w

w w

.u tp

jo ur

na ls

.p re

ss /d

oi /p

df /1

0. 31

38 /c

bm h.

7. 2.

16 1

164 C. STUART HOUSTON

plants and ate green shoots to get streng'th to set nets for fresh fish and to shoot birds.35 Thomas James used the Spruce infusion externally for his men in 1631-32, but only two men died of apparent scurvy.36 Christopher Middleton, who left the service of the Hudson's Bay Company to join the Royal Navy, led an exploring expedition in search of the Northwest Passage along the west coast of Hudson Bay. Eleven of his men died of scurvy.37

As has been well documented, it was during the mid- to late- eighteenth century that the remedial effects of lime or lemon juice for the prevention of scurvy were demonstrated. It was not until 1795, however, that British sailors were forced to consume a daily issue of lemon juice; but often there was a problem of compliance.

Even by the early nineteenth century, therefore, scurvy also lurked behind the scenes during British Naval explorations of the Canadian Arctic, searching for the fabled Northwest Passage to the riches of the Orient. Sir W. E. Parry's most successful Arctic sailing voyage, in which he sailed beyond 110" W. longitude to Melville Island in 1819- 20, was aided by growing mustard and cress in his cabin, collecting wild sorrel and providing 3,766 pounds of fresh meat. When the first man came down with scurvy at four months, the lemon juice ration was doubled. Although many lemon juice bottles froze and burst, there were no deaths from scurvy.38

On Parry's second expedition, 1821-23, he carried 6,000 gallons of lemon juice in wooden kegs, 30 jars of sliced lemons, 200 gallons of cranberries, and 150 pots of essence of spruce. Cress was sown. The first slight symptoms of scurvy were reported after 27 months but no one succumbed. His third voyage in 1824-25 was free from any sign of

John Ross did equally well. His journey in 1818 carried 2,775 pounds of lemon juice.40 Even though his men were trapped for four winters in the ice in 1829-33, and were given up for lost, there was no scurvy.41

On John Franklin's Overland Expedition of 1819-21, 11 of the 20 I

participants died, chiefly from s t a r v a t i ~ n . ~ ~ Contrary to the official naval medical history, Medicine and the Navy, 1200-1900, by Lloyd and C ~ u l t e r , ~ ~ scurvy played no part. Franklin's Second Overland Expedi- tion 1825-27 was well supplied so scurvy did not occur.44 George Back, who had been with Franklin on his first two expeditions, led an expedition of his own in 1834-35, without incidence of scurvy.45 In Back's sea voyage of 1836-37 he took 798 pounds of lemon juice, 100 pots of essence of syrup and 100 gallons of cranberries. When 20 of his 60 men came down with scurvy, his surgeon Dr. Donovan served extra lemon juice and cranberries. They had no access to fresh game and three men died of scurvy.46

Franklin's ill-fated third voyage in 1845 carried a good supply of antiscorbutics including onions, cranberries, preserved vegetables,

h ttp

s: //w

w w

.u tp

jo ur

na ls

.p re

ss /d

oi /p

df /1

0. 31

38 /c

bm h.

7. 2.

16 1

Scuwy and Canadian Exploration 165

and 9,300 pounds of lemon juice. Owen Beattie's recent studies of the remaining skeletons still lying on the beach of King William Island about 10 years ago, show evidence of scurvy and cannibalism, and three disinterred bodies showed signs of excess lead suggesting that they were harmed by lead poisoning.47

There was no problem with compliance on the McClure voyage searching for Franklin in 1850-54. Even though the juice had been prepared from lemons by boiling, a layer of olive oil to exclude air preserved it. Dr. Armstrong personally supervised the "pipe to lime juice" at 11 a.m. each day and observed each seaman swallowing his ounce. Although they were immobilized in the ice, and on short rations, there was no scurvy for 27 months. Scurvy was universal in the third winter and death was imminent when McClurels men were fortunately rescued by Lieutenant Pim of the Res~lufe.~~ Collinson's five-year Arctic search in 1850-55 had no scurvy at all4g and Dr. McCor- mick, the surgeon with Kellett in the Investigator, spent seven years in the Arctic without a case of Of the search expeditions, only McClintock's suffered from scurvy with a single death. When Thomas Blackwell, the ship's steward, died of scurvy Surgeon David Walker ascertained the cause: Blackwell had a dislike of preserved meats and potato and had lived the whole winter upon salt pork.51 Doctor John Rae, who followed the native method of living off the land, led four expeditions in the Arctic between 1846 and 1854. One man drowned in rapids, but no one died of scurvy.52

The last major Arctic exploring expedition to suffer from scurvy was that led by George S. Nares in 1875-76. Every man on his sledging parties developed scurvy. They could not thaw out the lime juice stored in 60-pound jars.53

Clearly, as this discussion has shown, there are strong connections between scurvy and Canadian exploration. From the sixteenth century to the nineteenth century, this affliction has been one of the many

I hardships facing sailors in their exploration attempts.

NOTES

* Excerpted from the Presidential Address delivered before the Canadian Society for the History of Medicine at its annual meeting in Quebec City, 1 June 1989.

1 Jacques Cartier, "Bref R6cit et Succincte Narration," trans. Jean L. Launay, Iacques Cartier et "La Grosse Maladie" (Montreal: Ronalds Printing Co. for the XIXe Congres International de Physiologie, 1953), p. 97-102.

2 Richard Hakluyt, The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques and Discoveries of the English Nation (London, 1600; reprinted Glasgow: James MacLehose, 1914), Vol. 8, p. 249-51.

3 Marc Lescarbot, The History of New France, trans., notes and appendices by W. L. Grant, intro. H. P. Biggar (Toronto: Champlain Society, 1911), Vol. 2, p. 257-71.

4 J. C. Drummond and Anne Wilbraham, The Englishman's Food (London: Jonathan Cape, 1939), p. 162-64.

5 E. E. Rich, "The Fur Traders: Their Diet and Drugs," Beaver, 307 (1976): 43-53.

h ttp

s: //w

w w

.u tp

jo ur

na ls

.p re

ss /d

oi /p

df /1

0. 31

38 /c

bm h.

7. 2.

16 1

166 C. STUART HOUSTON

6 Ann Savours and Margaret Deacon, "Nutritional Aspects of the British Arctic (Nares) Expedition of 1875-76 and Its Predecessors," in James Watt, E. J. Freeman, and W. F. Bynum, eds., Starving Sailors (Greenwich: National Maritime Museum, 1981), p. 131-62.

7 John Stewart, An Account of Prince Edward Island in the Gulph of St. Lawrence (London: W. Winchester & Sons, 1806), p. 50-51.

8 Arthur C. Parker, "Canadian Medicine and Medicine Men," in 36th Annual Archaeo- logical Report (Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Education, 1928), p. 9-17.

9 William N. Fenton, "Contacts Between Iroquois Herbalism and Colonial Medicine," in Annual Report, Smithsonian Institution (Washington: Smithsonian, 1941), p. 503- 26.

10 Charles Macnamara, "The Identity of the Tree 'Annedda,' " Science, 92 (1940): 35. 11 Charles Macnamara, "Vitamin C in Evergreen-Tree Needles," Science, 98 (1943):

242. 12 Virgil J. Vogel, American Indian Medicine (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press,

1970), p. 3, 4, 316. 13 Adam Shortt and Arthur G. Doughty, Canada and Its Provinces (Toronto: Glasgow,

Brook, 1924), p. 38. 14 Aaron J . Ihde and Stanley L. Becker, "Conflict of Concepts in Early Vitamin

Studies," Journal of the History of Biology, 4 (1971): 1-33. 15 A. Scheunert and J. Reschke, "Coniferennadeln und deren absude als Vitamin

C-trager," Klinische Wochenschrift, 19 (1940): 976-79. 16 Jacques Rousseau, "The Annedda Mystery," in Jacques Cartier et "La Grosse

Maladie," p. 117-29. 17 D'Avezac, Bref rkcit et succincte narration de la navigation faite en MDXXXV et

MDXXXVl par le capitaine Jacques Cartier aux iles de Canada, Hochelaga, Saguenay et autres. Reimpression figuree de l'edition originale rarissime de MDXLV avec les variantes des manuscrits de la bibliotheque imperiale. Pr6c6de d'une breve et succincte introduction historique par M. D'Avezac (reprinted Paris: Librairie Tross, 1863).

18 Charles Pickering, Chronological History of Plants (Boston: Little, Brown, 1879), p. 872-76.

19 R. Frank Chandler, Lois Freeman, and Shirley N. Hooper, "Herbal Remedies of the Maritime Indians," Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 1 (1979): 49-68.

20 C. F. Millspaugh, American Medicinal Plants (New York: Boericke and Tafel, 1887). 21 Michael A. Weiner, Earth Medicine- Earth Foods (New York: Macmillan, 1972), p. 4,

117. 22 C. S. Rafinesque, Medical Flora or Manual of Medical Botany of the United States

(Philadelphia: Samuel C. Atkinson, 1830), Vol. 2, p. 183. 23 Thomas B. Costain, The White and the Gold (Toronto: Doubleday Canada, 1954),

I p. 35-37. 24 Charlotte Erichsen-Brown, Useof Plants (Aurora: Breezy Creek Press, 1979), p. 8-14. 25 Andre Thevet, Les singularites de la France Antarctique (Paris: Maissonneuve, 1878),

p. 404-05. 26 Francis Parkman, Pioneers o f France in the New World (Boston: Little, Brown, 1894),

p. 214. 27 William M. Harlow, Trees of the Eastern United States and Canada (New York:

Whittlesey House, 1942), p. 69-72. 28 Jacques Rousseau, "L'annedda et l'arbre de vie," Revue $Histoire de I'Amkrique

Francaise, 8 (1954): 171-212. 29 R. C. Hosie, Native Trees of Canada (Toronto: Fitzhenry & Whiteside and the Cana-

dian Government Publishing Centre, 1979), p. 98. 30 Thomas S. Elias, The Complete Trees of North America (New York: Van Nostrand

Reinhold, 1980), p. 126-27. 31 H. P. Biggar, ed., The Works of Samuel de Champlain (Toronto: Champlain Society,

1922), Vol. 1, p. 303-06, 375-76, 449.

h ttp

s: //w

w w

.u tp

jo ur

na ls

.p re

ss /d

oi /p

df /1

0. 31

38 /c

bm h.

7. 2.

16 1

Scumy and Canadian Exploration 167

32 H. P. Biggar, ed., The Works of Samuel de Chainplain (Toronto: Champlain Society, 1922), Vol. 2, p. 59-62.

33 Rousseau, "L'annedda," p. 183. 34 Vihjalmur Stefansson, The Fat of the Land (New York: Macmillan, 1936), p. 174-75,

212. 35 Thorkild Hansen, The Way to Hudson Bay: The Life and Times of Jens Munk (New York:

Harcourt Brace & World, 1970), p. 252-94. 36 Miller Christy, ed., The Voyages of Captain LukeFoxeof Hull and Captain ThomasJames of

Bristol in Search of a North-west Passage (London: Hakluyt Society, 1894). 37 Alan Cooke and Clive Holland, The Exploration of Northern Canada, 500 to 1920: A

Chronology (Toronto: Arctic History Press, 1978). 38 William Edward Parry, Journal of a Voyage for the Discovery of a North-west Passage from

the Atlantic to the Pacific Performed in the Years 1819-20 in His Majesty's Ships Hecla andGriper (London: John Murray, 1821), and Edward Parry, Memoirs of Rear-Admiral Sir W. Edward Parry (London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans and Roberts, 1859), p. 114.

39 William Edward Parry, Journal of a Second Voyage for the Discovery of a North-west Passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific in the Years 1821-22-23 in His Majesty's Ships Fury and Hecla (London: John Murray, 1824).

40 John Ross, A Voyage of Discovery Made for the Purpose of Exploring Baffin Bay (London: John Murray, 1819).

41 John Ross, Narrative of a Second Voyage in Search of a North-west Passage (London: A. W. Webster, 1835).

42 John Franklin, Narrative of a Journey to the Shores of the Polar Sea in the Years 1819,20,21 and 22 (London: John Murray, 1823).

43 Christopher Lloyd and Jack L. S. Coulter, Medicine and the Navy, 1200-1900 (Edin- burgh: E. & S. Livingstone, 1963), Vol. 4, p. 71.

44 John Franklin, Narrative of a Second Expedition to the Shores of the Polar Sea in the Years 1825, 1826 and 1827 (London: John Murray, 1828).

45 George Back, Narrative of the Arctic Land Expedition to the Mouth of the Great…

C. STUART HOUSTON

The Canadian scurvy story begins over 450 years ago with Jacques Cartier, whose ships were imprisoned in the ice near Stadacona (pres- ent Quebec City) during the winter of 1535-36. Jacques Cartier in his "Bref Recit" clearly outlined the symptoms of this disease and its effects, noting that some crew "lost their very substance and their legs became swollen and puffed up while the sinews contracted and turned coal-black and, in some cases, all blotched with drops of purplish blood. Then the disease would creep up to the hips, thighs and shoul- ders, arms and neck. And all the sick had their mouths so tainted and their gums so decayed that the flesh peeled off down to the roots of their teeth while the latter almost all fell out in turn."

Cartier and his crew endured this affliction throughout the winter; in all about 75 men died or were given up for dead. By accident in the spring, however, Cartier encountered "a band of natives," and noticed one who had previously suffered similar symptoms, but who now appeared in perfect health. Cartier's account continued:

I The captain rejoiced to see Don Agaya well in mind and body for he hoped to learn from him the manner of his cure in order to apply the same treatment and remedy to his own men. As soon as the Indians had drawn near the fort the captain asked Don Agaya how he had been cured. The latter replied he knew of the juice and the dregs of the leaves of a tree which had healed him and was the one and only remedy for all diseases. . . . Don Agaya then sent two squaws to fetch some of that tree and they brought back nine or ten boughs. They told us how to strip off the bark and leaves from the wood, boil them in water, and drink the liquor every other day while placing the dregs on swollen and afflicted legs. This tree, they said, cured all diseases. In their language they call it Ameda.' [Spelling varies: Anneda, Annedda or Hanneda.]

C. S. Houston, 863 University Drive, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N OJ8.

CBMHIBCHM 1 Volume 7: 1990 1 p. 161-67

h ttp

s: //w

w w

.u tp

jo ur

na ls

.p re

ss /d

oi /p

df /1

0. 31

38 /c

bm h.

7. 2.

16 1

162 C. STUART HOUSTON

Following Don Agaya's advice, cartier and his crew prepared their own decoction and administered it to those men who wished it; all recovered their health.

Cartier's dramatic experience, one of the best-known stories in Canadian medical history, has received the attention of many medical historians and botanists. One question remains. Which tree was it that saved Cartier's men? Fortunately, almost every historian and botanist who has studied the matter has come up with the answer. But perhaps less fortunately, they have come up with different answers!

Which of eleven trees was Cartier's anneda? The Canada Yew, Taxus canadensis, Red Pine, Pinus resinosa, and Red Spruce, Picea rubens, are not strong contenders for the title. The remaining eight trees will be presented in roughly increasing order of probability, listing in turn the authorities who have chosen each tree species.

Sassafras, Sassafras albidum: Hakluyt, 1600;2 Lescarbot, 1609;3 Drum- mond and Wilbraham, 1940.4

Drummond and Wilbraham followed Hakluyt and Lescarbot in choosing Sassafras. Drummond was misled by Dr. J. Gilmour, Assist- ant Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, who assured him that Sassafras oficinale was "native to that part of Canada." Sassafras grows in Canada only in a narrow strip of southern Ontario.

Juniper, Juniperus communis: Rich, 1976;5 Savours and Deacon, 19816 E. E. Rich, the noted historian of the Hudson's Bay Company, chose

"Juniper, Pinette blanche" as the tree that had saved Cartier's men from scurvy. Two errors are involved. Juniper is a shrub that could not possibly fit Cartier's description of "a whole tree as large and tall as any oak in France." Epinette blanche spelled correctly would be the White Spruce, a better candidate. Rich's reputation was such that Savours and Deacon, reputable maritime historians, in their contribution to Sir James Watt's Staming Sailors, repeated Rich's errors verbatim.

I

Eastern Hemlock. Tsuga canadensis: Stewart, 1806;7 Parker, 1928;8 Fen- ton, 1942;9 Macnamara, 1940,1° 1943;" Vogel, 1970.12

Stewart told of the virtues of taking an infusion of hemlock three times daily as an antiscorbutic. Parker, a Seneca Indian and a distin- guished anthropologist, and Fenton chose hemlock as Cartier's anneda. Macnamara claimed that hemlock had more medicinal uses among the Indians than any other conifer infusion.

Balsam Fir. Abies balsamea: Shortt and Doughty, 1914;13 Ihde and Becker, 1971.14

The needles and bark of virtually all evergreens contain potentially curative amounts of Vitamin C,'"ut the Balsam Fir has the highest levels, 270 mg in 100 g of needles.l8

h ttp

s: //w

w w

.u tp

jo ur

na ls

.p re

ss /d

oi /p

df /1

0. 31

38 /c

bm h.

7. 2.

16 1

Scurvy and Canadian Exploration 163

Eastern White Pine, Pinus strobus: ~ ~ v e z a c , 1863;17 Pickering, 1879. ls

D'Avezac's carefully edited Cartier manuscript was the best to that time. The Micmac Indians used White Pine in treating scurvy, accord- ing to Chandler.l9 White Pine is "ohnehta" in the Mohawk language (James Herrick and Don Moerman-personal communication).

Black Spruce, Picea mariana: Millspaugh, 1887;20 Weiner, 1972.21 Black Spruce and Red Spruce were the main sources for the manu-

facture of spruce beer, used by whites as an antiscorbutic and by Indians over two centuries.

White Spruce, Picea glauca: C. S . Rafinesque, 1830;22 Thomas B. Cos- tain, 1954;23 Erichsen-Brown, 1979.24

Erichsen-Brown has compiled the most complete, authentic study of the medicinal use of North American plants. The needles of the White Spruce are the most appetizing to chew. White Spruce is "onnita" in Mohawk and "onnetta" in Onandaga.

Eastern White Cedar. Thuja occidentalis: Thevet, 1568;2s Parkman, 1894;26 Harlow, 1942;27 Rousseau, 1954;28 Hosie, 1979;29 Elias, 1980.30

The White Cedar is the best candidate for Cartier's anneda, as chosen by Th6vet in 1568 and over three centuries later by Francis Parkman, the eminent American Indian historian. The most convincing evidence was collected by Jacques Rousseau, a leading Quebec botanist who methodically assessed the botanical, linguistic, folkloric, and biochem- ical aspects of the problem. Seeds of the Eastern White Cedar were delivered to the royal garden at Fontainebleau during the reign of King Francis I, before 1547. The resulting tree was given the name of arbor vitae-but later generations then appear to have forgotten why it had been given this name!

Those who followed Cartier unfortunately failed to benefit from this I experience. Knowledge can be fleeting. Samuel de Champlain and his

men fared even worse. There were no longer any Indians residing near Quebec City to direct the white men to the appropriate tree. In 1604-05, 35 of Champlain's men died of scurvy at the St. Croix Islands and in the following two winters Champlain lost 12 and 7 men, respectively, at Port RoyaL31 Champlain observed that scurvy could be avoided by "good bread and fresh meat."32 The new settlements in Quebec con- tinued to be ravaged by scurvy for another 25 years.33

Indians and those fur traders whose diet included fresh meat were free from scurvy throughout most of North Ameri~a.~" However, the sailors who explored Hudson Bay in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries had varying degrees of difficulty from scurvy. Jens Munk lost 62 of his party of 65, nearly all from scurvy, while wintering at Church- ill in 1619-20. Munk and the other two survivors sucked the roots of

h ttp

s: //w

w w

.u tp

jo ur

na ls

.p re

ss /d

oi /p

df /1

0. 31

38 /c

bm h.

7. 2.

16 1

164 C. STUART HOUSTON

plants and ate green shoots to get streng'th to set nets for fresh fish and to shoot birds.35 Thomas James used the Spruce infusion externally for his men in 1631-32, but only two men died of apparent scurvy.36 Christopher Middleton, who left the service of the Hudson's Bay Company to join the Royal Navy, led an exploring expedition in search of the Northwest Passage along the west coast of Hudson Bay. Eleven of his men died of scurvy.37

As has been well documented, it was during the mid- to late- eighteenth century that the remedial effects of lime or lemon juice for the prevention of scurvy were demonstrated. It was not until 1795, however, that British sailors were forced to consume a daily issue of lemon juice; but often there was a problem of compliance.

Even by the early nineteenth century, therefore, scurvy also lurked behind the scenes during British Naval explorations of the Canadian Arctic, searching for the fabled Northwest Passage to the riches of the Orient. Sir W. E. Parry's most successful Arctic sailing voyage, in which he sailed beyond 110" W. longitude to Melville Island in 1819- 20, was aided by growing mustard and cress in his cabin, collecting wild sorrel and providing 3,766 pounds of fresh meat. When the first man came down with scurvy at four months, the lemon juice ration was doubled. Although many lemon juice bottles froze and burst, there were no deaths from scurvy.38

On Parry's second expedition, 1821-23, he carried 6,000 gallons of lemon juice in wooden kegs, 30 jars of sliced lemons, 200 gallons of cranberries, and 150 pots of essence of spruce. Cress was sown. The first slight symptoms of scurvy were reported after 27 months but no one succumbed. His third voyage in 1824-25 was free from any sign of

John Ross did equally well. His journey in 1818 carried 2,775 pounds of lemon juice.40 Even though his men were trapped for four winters in the ice in 1829-33, and were given up for lost, there was no scurvy.41

On John Franklin's Overland Expedition of 1819-21, 11 of the 20 I

participants died, chiefly from s t a r v a t i ~ n . ~ ~ Contrary to the official naval medical history, Medicine and the Navy, 1200-1900, by Lloyd and C ~ u l t e r , ~ ~ scurvy played no part. Franklin's Second Overland Expedi- tion 1825-27 was well supplied so scurvy did not occur.44 George Back, who had been with Franklin on his first two expeditions, led an expedition of his own in 1834-35, without incidence of scurvy.45 In Back's sea voyage of 1836-37 he took 798 pounds of lemon juice, 100 pots of essence of syrup and 100 gallons of cranberries. When 20 of his 60 men came down with scurvy, his surgeon Dr. Donovan served extra lemon juice and cranberries. They had no access to fresh game and three men died of scurvy.46

Franklin's ill-fated third voyage in 1845 carried a good supply of antiscorbutics including onions, cranberries, preserved vegetables,

h ttp

s: //w

w w

.u tp

jo ur

na ls

.p re

ss /d

oi /p

df /1

0. 31

38 /c

bm h.

7. 2.

16 1

Scuwy and Canadian Exploration 165

and 9,300 pounds of lemon juice. Owen Beattie's recent studies of the remaining skeletons still lying on the beach of King William Island about 10 years ago, show evidence of scurvy and cannibalism, and three disinterred bodies showed signs of excess lead suggesting that they were harmed by lead poisoning.47

There was no problem with compliance on the McClure voyage searching for Franklin in 1850-54. Even though the juice had been prepared from lemons by boiling, a layer of olive oil to exclude air preserved it. Dr. Armstrong personally supervised the "pipe to lime juice" at 11 a.m. each day and observed each seaman swallowing his ounce. Although they were immobilized in the ice, and on short rations, there was no scurvy for 27 months. Scurvy was universal in the third winter and death was imminent when McClurels men were fortunately rescued by Lieutenant Pim of the Res~lufe.~~ Collinson's five-year Arctic search in 1850-55 had no scurvy at all4g and Dr. McCor- mick, the surgeon with Kellett in the Investigator, spent seven years in the Arctic without a case of Of the search expeditions, only McClintock's suffered from scurvy with a single death. When Thomas Blackwell, the ship's steward, died of scurvy Surgeon David Walker ascertained the cause: Blackwell had a dislike of preserved meats and potato and had lived the whole winter upon salt pork.51 Doctor John Rae, who followed the native method of living off the land, led four expeditions in the Arctic between 1846 and 1854. One man drowned in rapids, but no one died of scurvy.52

The last major Arctic exploring expedition to suffer from scurvy was that led by George S. Nares in 1875-76. Every man on his sledging parties developed scurvy. They could not thaw out the lime juice stored in 60-pound jars.53

Clearly, as this discussion has shown, there are strong connections between scurvy and Canadian exploration. From the sixteenth century to the nineteenth century, this affliction has been one of the many

I hardships facing sailors in their exploration attempts.

NOTES

* Excerpted from the Presidential Address delivered before the Canadian Society for the History of Medicine at its annual meeting in Quebec City, 1 June 1989.

1 Jacques Cartier, "Bref R6cit et Succincte Narration," trans. Jean L. Launay, Iacques Cartier et "La Grosse Maladie" (Montreal: Ronalds Printing Co. for the XIXe Congres International de Physiologie, 1953), p. 97-102.

2 Richard Hakluyt, The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques and Discoveries of the English Nation (London, 1600; reprinted Glasgow: James MacLehose, 1914), Vol. 8, p. 249-51.

3 Marc Lescarbot, The History of New France, trans., notes and appendices by W. L. Grant, intro. H. P. Biggar (Toronto: Champlain Society, 1911), Vol. 2, p. 257-71.

4 J. C. Drummond and Anne Wilbraham, The Englishman's Food (London: Jonathan Cape, 1939), p. 162-64.

5 E. E. Rich, "The Fur Traders: Their Diet and Drugs," Beaver, 307 (1976): 43-53.

h ttp

s: //w

w w

.u tp

jo ur

na ls

.p re

ss /d

oi /p

df /1

0. 31

38 /c

bm h.

7. 2.

16 1

166 C. STUART HOUSTON

6 Ann Savours and Margaret Deacon, "Nutritional Aspects of the British Arctic (Nares) Expedition of 1875-76 and Its Predecessors," in James Watt, E. J. Freeman, and W. F. Bynum, eds., Starving Sailors (Greenwich: National Maritime Museum, 1981), p. 131-62.

7 John Stewart, An Account of Prince Edward Island in the Gulph of St. Lawrence (London: W. Winchester & Sons, 1806), p. 50-51.

8 Arthur C. Parker, "Canadian Medicine and Medicine Men," in 36th Annual Archaeo- logical Report (Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Education, 1928), p. 9-17.

9 William N. Fenton, "Contacts Between Iroquois Herbalism and Colonial Medicine," in Annual Report, Smithsonian Institution (Washington: Smithsonian, 1941), p. 503- 26.

10 Charles Macnamara, "The Identity of the Tree 'Annedda,' " Science, 92 (1940): 35. 11 Charles Macnamara, "Vitamin C in Evergreen-Tree Needles," Science, 98 (1943):

242. 12 Virgil J. Vogel, American Indian Medicine (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press,

1970), p. 3, 4, 316. 13 Adam Shortt and Arthur G. Doughty, Canada and Its Provinces (Toronto: Glasgow,

Brook, 1924), p. 38. 14 Aaron J . Ihde and Stanley L. Becker, "Conflict of Concepts in Early Vitamin

Studies," Journal of the History of Biology, 4 (1971): 1-33. 15 A. Scheunert and J. Reschke, "Coniferennadeln und deren absude als Vitamin

C-trager," Klinische Wochenschrift, 19 (1940): 976-79. 16 Jacques Rousseau, "The Annedda Mystery," in Jacques Cartier et "La Grosse

Maladie," p. 117-29. 17 D'Avezac, Bref rkcit et succincte narration de la navigation faite en MDXXXV et

MDXXXVl par le capitaine Jacques Cartier aux iles de Canada, Hochelaga, Saguenay et autres. Reimpression figuree de l'edition originale rarissime de MDXLV avec les variantes des manuscrits de la bibliotheque imperiale. Pr6c6de d'une breve et succincte introduction historique par M. D'Avezac (reprinted Paris: Librairie Tross, 1863).

18 Charles Pickering, Chronological History of Plants (Boston: Little, Brown, 1879), p. 872-76.

19 R. Frank Chandler, Lois Freeman, and Shirley N. Hooper, "Herbal Remedies of the Maritime Indians," Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 1 (1979): 49-68.

20 C. F. Millspaugh, American Medicinal Plants (New York: Boericke and Tafel, 1887). 21 Michael A. Weiner, Earth Medicine- Earth Foods (New York: Macmillan, 1972), p. 4,

117. 22 C. S. Rafinesque, Medical Flora or Manual of Medical Botany of the United States

(Philadelphia: Samuel C. Atkinson, 1830), Vol. 2, p. 183. 23 Thomas B. Costain, The White and the Gold (Toronto: Doubleday Canada, 1954),

I p. 35-37. 24 Charlotte Erichsen-Brown, Useof Plants (Aurora: Breezy Creek Press, 1979), p. 8-14. 25 Andre Thevet, Les singularites de la France Antarctique (Paris: Maissonneuve, 1878),

p. 404-05. 26 Francis Parkman, Pioneers o f France in the New World (Boston: Little, Brown, 1894),

p. 214. 27 William M. Harlow, Trees of the Eastern United States and Canada (New York:

Whittlesey House, 1942), p. 69-72. 28 Jacques Rousseau, "L'annedda et l'arbre de vie," Revue $Histoire de I'Amkrique

Francaise, 8 (1954): 171-212. 29 R. C. Hosie, Native Trees of Canada (Toronto: Fitzhenry & Whiteside and the Cana-

dian Government Publishing Centre, 1979), p. 98. 30 Thomas S. Elias, The Complete Trees of North America (New York: Van Nostrand

Reinhold, 1980), p. 126-27. 31 H. P. Biggar, ed., The Works of Samuel de Champlain (Toronto: Champlain Society,

1922), Vol. 1, p. 303-06, 375-76, 449.

h ttp

s: //w

w w

.u tp

jo ur

na ls

.p re

ss /d

oi /p

df /1

0. 31

38 /c

bm h.

7. 2.

16 1

Scumy and Canadian Exploration 167

32 H. P. Biggar, ed., The Works of Samuel de Chainplain (Toronto: Champlain Society, 1922), Vol. 2, p. 59-62.

33 Rousseau, "L'annedda," p. 183. 34 Vihjalmur Stefansson, The Fat of the Land (New York: Macmillan, 1936), p. 174-75,

212. 35 Thorkild Hansen, The Way to Hudson Bay: The Life and Times of Jens Munk (New York:

Harcourt Brace & World, 1970), p. 252-94. 36 Miller Christy, ed., The Voyages of Captain LukeFoxeof Hull and Captain ThomasJames of

Bristol in Search of a North-west Passage (London: Hakluyt Society, 1894). 37 Alan Cooke and Clive Holland, The Exploration of Northern Canada, 500 to 1920: A

Chronology (Toronto: Arctic History Press, 1978). 38 William Edward Parry, Journal of a Voyage for the Discovery of a North-west Passage from

the Atlantic to the Pacific Performed in the Years 1819-20 in His Majesty's Ships Hecla andGriper (London: John Murray, 1821), and Edward Parry, Memoirs of Rear-Admiral Sir W. Edward Parry (London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans and Roberts, 1859), p. 114.

39 William Edward Parry, Journal of a Second Voyage for the Discovery of a North-west Passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific in the Years 1821-22-23 in His Majesty's Ships Fury and Hecla (London: John Murray, 1824).

40 John Ross, A Voyage of Discovery Made for the Purpose of Exploring Baffin Bay (London: John Murray, 1819).

41 John Ross, Narrative of a Second Voyage in Search of a North-west Passage (London: A. W. Webster, 1835).

42 John Franklin, Narrative of a Journey to the Shores of the Polar Sea in the Years 1819,20,21 and 22 (London: John Murray, 1823).

43 Christopher Lloyd and Jack L. S. Coulter, Medicine and the Navy, 1200-1900 (Edin- burgh: E. & S. Livingstone, 1963), Vol. 4, p. 71.

44 John Franklin, Narrative of a Second Expedition to the Shores of the Polar Sea in the Years 1825, 1826 and 1827 (London: John Murray, 1828).

45 George Back, Narrative of the Arctic Land Expedition to the Mouth of the Great…

Related Documents