The Hermeneutics of Sacred Architecture: A Reassessment of the Similtude between Tula, Hidalgo and Chichen Itza, Yucatan, Part I Author(s): Lindsay Jones Source: History of Religions, Vol. 32, No. 3 (Feb., 1993), pp. 207-232 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1062996 Accessed: 14-06-2017 17:29 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1062996?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to History of Religions This content downloaded from 140.254.87.149 on Wed, 14 Jun 2017 17:29:53 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

s THE HERMENEUTICS OF SACRED ARCHITECTURE: A REASSESSMENT OF THE SIMILTUDE BETWEEN TULA, HIDALGO AND CHICHEN ITZA, YUCATAN, PART I

Apr 05, 2023

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

The Hermeneutics of Sacred Architecture: A Reassessment of the Similtude between Tula, Hidalgo and Chichen Itza, Yucatan, Part IThe Hermeneutics of Sacred Architecture: A Reassessment of the Similtude between Tula, Hidalgo and Chichen Itza, Yucatan, Part I Author(s): Lindsay Jones Source: History of Religions, Vol. 32, No. 3 (Feb., 1993), pp. 207-232 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1062996 Accessed: 14-06-2017 17:29 UTC

REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1062996?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted

digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about

JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

http://about.jstor.org/terms

The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to History of Religions

This content downloaded from 140.254.87.149 on Wed, 14 Jun 2017 17:29:53 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Lindsay Jones THE HERMENEUTICS OF SACRED ARCHITECTURE:

A REASSESSMENT OF THE

TULA, HIDALGO AND CHICHEN ITZA, YUCATAN, PART I

Once upon a time, a summer Sunday in 1987, I found myself sitting in the back of the huge fortress-like cathedral in Cuernavaca, Morelos, Mexico. The place was hot and packed full when the priest made his dra- matic entrance. Dressed in elaborate vestments and swinging his incense decanter, he led a very formal procession down to the altar space and then, to the oddly appropriate background music of mariachi guitars, the celebration of the Eucharist began. More memorable than the actual mass, however, was a little Mexican boy, some three feet tall, who wan- dered in the aisle in front of me and who became fascinated with a little

relief carving of an angel that, conveniently enough, was precisely the same height as this young Mexican. And so, while this meticulously choreographed mass with music, vestments, scriptural readings, and holy sacraments was being performed for hundreds of people in the con- gregation, this little boy spent the hour in the side aisle involved in a very animated conversation with this same-sized stone angel. He greeted her nose-to-nose, put his hands all over her, interrogated her, and then stepped back fully expectant, so it seemed, of a response.

AGENDA: METHODOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL PROBLEMS

This untutored exchange between the little boy and the 400-year-old stone angel, a ritual-architectural event of compelling simplicity, a

? 1993 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. 0018-2710/93/3203-0001$01.00

This content downloaded from 140.254.87.149 on Wed, 14 Jun 2017 17:29:53 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

The Hermeneutics of Sacred Architecture

hermeneutical conversation in which a human being questioned an ar- chitectural monument and then listened for its answer, provides the im- age that sustains this twice-titled essay.1 Aspiring to address both a general methodological issue and a more specific historical one, this essay discusses each of the two titles individually and then presents a working hypothesis that draws the theoretical and historical concerns together.

The first title-"The Hermeneutics of Sacred Architecture"-refers

to a set of general theoretical and methodological concerns, that is, sweeping cross-cultural concerns about sacred architecture in any his- torical context: for example, What is sacred architecture in general? What is the mechanism of sacred architecture? How does architecture

"mean" things? And how does the experience of architecture work to change people and their vision of the world? Moreover, this first title refers to the general methodological problems inherent in the study of sacred architecture: for example, What are the potentialities and the limitations of sacred architectures as data for the study of religion? Or, more general still, what are the potentialities and limitations for rely- ing on any sort of nonliterary, artistic, archaeological, or performative sorts of evidences for the study of the history of religions-a field that, after all, has typically legitimated itself via the interpretation of liter- ary texts, that is, written words.2

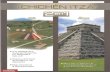

By contrast to these rangy methodological issues about the human experience of sacred architecture and the hermeneutical interpretation of sacred architecture, the second title-"A Reassessment of the Simil- itude between Tula, Hidalgo and Chichen Itza, Yucatan"-refers to a much more specific historical problem, a famous and infamous prob- lem in Mesoamerican archaeology related to the uncanny resemblance between the architectural remains of two pre-Columbian cities that lie some 800 miles apart but that find no such similar counterparts any- where in between. In other words, the "problem" of the similitude be- tween the architectures of Tula, Hidalgo and Chichen Itza, Yucatan- or simply the "Tula-Chichen problem"-assuredly among a handful of the most enduring and most significant debates in the Mesoamerican field, lies in explaining the nature of the historical relatedness between

1 This article is the first installment of a two-part essay; the second half will appear in the May 1993 issue of History of Religions. The arguments I present need to be assessed in the context of the entire piece.

2 These are particularly poignant questions for the study of pre-Columbian Mesoamer- ican religion because there is, on the one hand, an enormous fund of architectural and ar- chaeological evidences-i.e., ruined monuments-yet, on the other hand, particularly in the Maya area (other than the abundant hieroglyphic inscriptions), a near-total void of contemporaneous written texts. Accordingly, in the Maya zone, architecture becomes, by its handsomeness and by default, the datum of priority.

208

This content downloaded from 140.254.87.149 on Wed, 14 Jun 2017 17:29:53 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

History of Religions

these two far-flung twin cities. In short, why do these two sets of pre- Hispanic buildings look so much alike when nothing between looks that way?

The conventional explanation of Tula-Chichen Itza relatedness, al- though there has never really been a consensus on the historical par- ticulars, holds that, at some point in the pre-Columbian past (perhaps the ninth or tenth century C.E.), a small but fiercely militant contingent of Toltec renegades from Tula marched out of their central Mexican homeland into the Yucatan Peninsula, where they overpowered the more intellectually predisposed Maya and then built (or forced the in- digenous Maya to build) that portion of Chichen Itza that so resembles the original Toltec capital of Tula. Despite burgeoning evidence that this tawdry tale of the so-called Toltec Conquest of the Maya corre- sponds only faintly, if at all, to anything that actually happened in pre- Hispanic Mesoamerica, scholars and tour guides alike continue to recite variations of this glamorous story with vigor and conviction. Nevertheless, while the historical problems about who was where when (let alone why) are fascinating in their own right-and a primer on those specific problems is forthcoming in the next few pages-it is the methodological even more than the historical dimensions of this fa-

mous debate that are fascinating to the comparative historian of reli- gions. And with that as a segue, the discussion returns to that initial set of broadly theoretical issues about the hermeneutical experience and the hermeneutical interpretation of sacred architecture.

METHODOLOGICAL PROBLEMS: THE HERMENEUTICAL EXPERIENCE OF

ARCHITECTURE

Like mothers of men, the buildings are good listeners. [ADRIAN STOKES, 1951]3

In the last analysis, Goethe's statement "Everything is a symbol" is the most comprehensive formulation of the hermeneutical idea. It means that everything points to another thing . . the universality of the hermeneutical perspective is all-encompassing. [HANS-GEORG GADAMER, 1964]4

Hermeneutical reflection arises from the encounter with strangeness or otherness. By the grace of hermeneutics, distant meanings are brought close, strangeness becomes familiar, and bridges arise between the

3 Adrian Stokes, Smooth and Rough (London: Faber & Faber, 1951); excerpt reprinted in The Image in Form: Selected Writings of Adrian Stokes, ed. Richard Wollheim (New York: Harper & Row, 1972), p. 74.

4 Hans-Georg Gadamer, "Aesthetics and Hermeneutics," in Philosophical Hermeneu- tics, trans. and ed. David E. Linge (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976), p. 103.

209

This content downloaded from 140.254.87.149 on Wed, 14 Jun 2017 17:29:53 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

The Hermeneutics of Sacred Architecture

once and the now. When the sense of a text, an action, or an institution

is immediately self-evident understanding proceeds unimpeded; inter- pretation is noncontroversial and no hermeneutical reflection is re- quired. But the sense of symbols and of religiohistorical phenomena is nearly always more elusive, at once beckoning us to understand and yet withholding the abundance of their meanings. This elusive double- ness of meaning-a conjoined familiarity and foreignness-gives rise to hermeneutical inquiry. Hermeneutical reflection involves, in other words, a circumstance in which a person feels interested or compelled to make sense of something or someone but in which the process of understanding meets resistance because the meanings of the situation are somehow obscured. When the process of human understanding meets resistance, that is, when meanings are not immediately apparent, the hermeneut is cast into a kind of questioning and being answered, a cycle of projection and revision as one catches glimpses of the object or circumstance of his/her attention, makes guesses or hypotheses about that circumstance, and then eventually has those guesses either confirmed or rejected after moving into position for a better view.

This sort of to-and-fro conversation process of hermeneutical under- standing may find its most technical and most self-conscious expres- sion in the interaction between scholars and the arcane texts that they aspire to decipher. Gadamer (among others) argues convincingly, how- ever, that this sort of dialogical process of understanding applies not simply to the scholar's critical interpretation of texts but to any circum- stance in which human beings have invested themselves in understand- ing objects and phenomena whose meanings are not immediately clear.5 Moreover, to cite Gadamer's own prime example (and to recall the quaint image of the little Mexican boy interrogating the stone an- gel), nowhere is the notion of dialogical, interactive, to-and-fro herme- neutical reflection more applicable than in the human experience of sacred architecture, in the human confrontation with a cathedral, a mosque, or a Mesoamerican pyramid whose fund of potential meanings is intriguing and profound but not at all obvious.6

5 David E. Klemm, Hermeneutical Inquiry (Atlanta: Scholars, 1986), traces the histor- ical evolution and "universalization to the hermeneutical problem" from Schleiermacher through Dilthey and Heidegger to Gadamer and Ricouer. See especially Hans-Georg Gadamer, "The Universality of the Hermeneutical Problem," in Philosophical Herme- neutics, pp. 3-17. In the same vein, Gerardus van der Leeuw, e.g., in his famous "Epile- gomena" to Religion in Essence and Manifestation, trans. J. E. Turner (Gloucester, Mass.: Smith, 1967), pp. 675-76, argued on the basis of his reading of Edmund Husserl that "phenomenology [like hermeneutics] is not a method that has been reflectively elab- orated but is man's true vital activity."

6 In the context of his discussion of the open and "eventful" character of works of art, Gadamer says that "we shall find the most plastic of the arts, architecture, especially

210

This content downloaded from 140.254.87.149 on Wed, 14 Jun 2017 17:29:53 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

History of Religions

THE SUPERABUNDANCE OF ARCHITECTURE

[Mesoamerican] architecture goes beyond metaphor; it is the space of power, sacred and secular; it is the meeting place of the real and the supernatural. Architecture becomes deity, as a ruler becomes a god. Architecture transcends the manifest elements of which it is composed in a way that is awesome to the imagination. [ELIZABETH P. BENSON, 1985]7

We have only to interpret that which has a multiplicity of meanings. [HANS-GEORG GADAMER, 1961]8

Thus the experience of art-and most especially the experience of ar- chitecture9-not only falls within the sweep of hermeneutical reflec- tion, it wins a priority in Gadamer's exposition of understanding because the experience of art lays bare that which is less obvious in other realms of understanding. According to Gadamer, works of art and architecture are available to endless reinterpretation and revalori- zation because they hold within them inexhaustible reservoirs of "on- tological possibility"; the work of art "stands open for ever new integrations" and buildings, like works of art, are loci from which "strangenesses" perpetually emerge. Thus, in remarks that are particu- larly relevant to the centuries-old architectural ruins of Mesoamerica, Gadamer argues: "The creator of a work of art may intend the public of his own time, but the real being of his work is what it is able to say, and this being reaches fundamentally beyond any historical confine- ment. In this sense, the work of art occupies a timeless present."10

Owing to this superabundance of meanings, religious monuments, especially those that endure over a long stretch of time, have a kind of autonomy, an independence or unpredictability, a "personality" of sorts. Religious buildings arise as human creations, but they persist as

instructive"; his remarks explicitly on architecture are, however, brief and difficult. See Gadamer, Truth and Method, trans. W. Glen-Doepel (London: Sheed & Ward, 1975), pp. 119, 138-42.

7 Elizabeth P. Benson, "Architecture as Metaphor," in Fifth Palenque Round Table, 1983, vol. 7, ed. Merle Grene Robertson (San Francisco: Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute, 1985), p. 199.

8 Hans-Georg Gadamer, "Composition and Interpretation," in The Relevance of the Beautiful and Other Essays, ed. Robert Bernasconi (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), p. 69.

9 It has been commonplace to attribute to architecture a special status among the arts by virtue of its unique complementary participation, on the one hand, in the "functional" realm of utility (i.e., shelter) and, on the other hand, in an aesthetic realm that transcends the merely practical. In the same vein, Gadamer, Truth and Method, pp. 138-42, consid- ers architecture to be the paramount exemplar of the revealment-concealment interplay that characterizes all hermeneutical reflection because a work of architecture is both a

very accessible element of the practical sphere of utility and a genuine work of art with an "excess of meaning."

10 Gadamer, "Aesthetics and Hermeneutics," p. 96.

211

This content downloaded from 140.254.87.149 on Wed, 14 Jun 2017 17:29:53 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

The Hermeneutics of Sacred Architecture

life-altering environments; they are, at once, expressions and sources of religious experience. As both created and creator, a religious build- ing manifests the aspirations and intentions of its builders, yet the meaning of a building "not occasionally, but always" surpasses those original intentions.1l For all the careful intentions of architects, build- ings-religious, civic, or otherwise-invariably (and usually almost immediately) spring free from those carefully contrived programs of meaning and begin to evoke feelings and ideas that had never even oc- curred to their original designers. We can well imagine, for instance, that whatever idiosyncratic issues about which the Mexican boy and the stone angel were conversing, it was not a conversation that had been anticipated by the seventeenth-century builders of the cathedral.12

The superabundance of religious monuments has profound con- sequences not simply for the experience of sacred architecture but, likewise, for the academic interpretation of sacred architecture. Appre- ciating the inherent versatility and inexhaustibility of, for instance, a pre-Columbian pyramid both threatens and enlivens its interpretation. The malleability, openness, and character of possibility within religious buildings ensures a wealth of meanings that will never be given over in their description as static constructional forms; in other words, even the most rudely honed megalithic menhirs do not just stand there mute and available for their once-and-for-all analysis as objects. Wrenched from its relatedness to human beings and to some particular function or cere- monial occasion, a religious building loses its meaning, or, more likely, its diverse meanings are set adrift without context or perspective. More- over, beyond the flux in meanings and functions between different cer- emonial occasions at a single monument, the decipherment of sacred architecture is complicated more still because, invariably, the built en- vironment simultaneously evokes a range of disparate meanings from the heterogeneous constituency that is experiencing it-obviously, for instance, the clergy, the committed laypersons, and the casual tourist each have very different experience of the mass in the Cuernavaca cathedral. Like actors in an intricately choreographed pageant, individ- uals and social factions play different roles and bring different pre- parednesses to their respective experiences of the architectonic world, and, not surprisingly, their sentiments and perceptions of that world are similarly variegated.

1 I borrow this phrase from Gadamer, Truth and Method, p. 280, where he is speak- ing of the inexhaustibility of texts.

12 In the phrasing of architectural semiology, "certain 'symbolic' functions, especially in ancient architecture, survive the obliteration of their actual connotative and denotative functions"; in other words, the original intention of a building is but the first of countless re-creations. See, e.g., Francoise Choay, "Urbanism and Semiology," in Meaning in Ar- chitecture, ed. Charles Jencks and George Baird (New York: Braziller, 1969), p. 31.

212

This content downloaded from 140.254.87.149 on Wed, 14 Jun 2017 17:29:53 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

History of Religions

That religious buildings invariably overstretch the original inten- tions of their builders to mean many different things in different his- torical epoches to different people, or even to the same person during different ritual circumstances, seems painfully obvious (whether we learn this from Gadamer or dozens of other theorists). Nevertheless, the failure to acknowledge the incontestable multivocality of monu- mental architecture has been perhaps the foremost obstacle in the reso- lution of the Tula-Chichen problem. Neglecting all too often to consider either the diversity of ritual circumstances in which various monuments must have participated or the diverse disposition of the various human actors (and fixating instead on the formal and technical properties of buildings),13 the art historical and archaeological litera- ture on pre-Columbian architecture (and Tula and Chichen Itza are hardly exceptions in this regard) is overbrimming with presumptions as to the meaning of this pyramid, or the significance of that serpent mo- tif, or the "real" message of this elaborate staircase.

Alternatively then, if historians of religions are to transcend this pre- occupation with the formal attributes of buildings and if we are to ap- preciate that the meanings of religious buildings are never disembodied from the situational context in which those meanings arise, then it is essential that we shift the inquiry away from the study of buildings per se, that is, physical forms of granite, limestone, wood, steel, or what- ever, and concentrate instead (in the spirit of Gadamer's inquiry into the "ontology of works of art") on the human experience of buildings. In other words, because buildings do not have one fixed meaning ("re- ligious" or otherwise) for all people in all times, it is essential that any study into the meanings of sacred architecture be constituted not in terms of static buildings (as though there were somehow one meaning per architectural form) but rather in terms of occasions, ritual circum- stances-or "ritual-architectural events," if you will-in which the buildings are active participants and some subset of the reservoir of potential meanings arises from those built forms.14 It is not, after all,

13 Irwin Panofsky's discussion of "the law of disjunction"-a principle derived from the observation that medieval European art borrowed forms from classical antiquity but assigned entirely different significances to those forms-illustrates in a quite different way both (1) that the hinge between architectural form and meaning is never locked tight and, consequently, (2) that to study and compare various architectures strictly on the ba- sis of their formal attributes is certain to lead to serious mistakes; see Panofsky, Renais- sance and Renascences in Western Art (Stockholm: Almquist & Wiksells, 1960); also see George Kubler, "Period, Style and Meaning…

REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1062996?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted

digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about

JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

http://about.jstor.org/terms

The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to History of Religions

This content downloaded from 140.254.87.149 on Wed, 14 Jun 2017 17:29:53 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Lindsay Jones THE HERMENEUTICS OF SACRED ARCHITECTURE:

A REASSESSMENT OF THE

TULA, HIDALGO AND CHICHEN ITZA, YUCATAN, PART I

Once upon a time, a summer Sunday in 1987, I found myself sitting in the back of the huge fortress-like cathedral in Cuernavaca, Morelos, Mexico. The place was hot and packed full when the priest made his dra- matic entrance. Dressed in elaborate vestments and swinging his incense decanter, he led a very formal procession down to the altar space and then, to the oddly appropriate background music of mariachi guitars, the celebration of the Eucharist began. More memorable than the actual mass, however, was a little Mexican boy, some three feet tall, who wan- dered in the aisle in front of me and who became fascinated with a little

relief carving of an angel that, conveniently enough, was precisely the same height as this young Mexican. And so, while this meticulously choreographed mass with music, vestments, scriptural readings, and holy sacraments was being performed for hundreds of people in the con- gregation, this little boy spent the hour in the side aisle involved in a very animated conversation with this same-sized stone angel. He greeted her nose-to-nose, put his hands all over her, interrogated her, and then stepped back fully expectant, so it seemed, of a response.

AGENDA: METHODOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL PROBLEMS

This untutored exchange between the little boy and the 400-year-old stone angel, a ritual-architectural event of compelling simplicity, a

? 1993 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. 0018-2710/93/3203-0001$01.00

This content downloaded from 140.254.87.149 on Wed, 14 Jun 2017 17:29:53 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

The Hermeneutics of Sacred Architecture

hermeneutical conversation in which a human being questioned an ar- chitectural monument and then listened for its answer, provides the im- age that sustains this twice-titled essay.1 Aspiring to address both a general methodological issue and a more specific historical one, this essay discusses each of the two titles individually and then presents a working hypothesis that draws the theoretical and historical concerns together.

The first title-"The Hermeneutics of Sacred Architecture"-refers

to a set of general theoretical and methodological concerns, that is, sweeping cross-cultural concerns about sacred architecture in any his- torical context: for example, What is sacred architecture in general? What is the mechanism of sacred architecture? How does architecture

"mean" things? And how does the experience of architecture work to change people and their vision of the world? Moreover, this first title refers to the general methodological problems inherent in the study of sacred architecture: for example, What are the potentialities and the limitations of sacred architectures as data for the study of religion? Or, more general still, what are the potentialities and limitations for rely- ing on any sort of nonliterary, artistic, archaeological, or performative sorts of evidences for the study of the history of religions-a field that, after all, has typically legitimated itself via the interpretation of liter- ary texts, that is, written words.2

By contrast to these rangy methodological issues about the human experience of sacred architecture and the hermeneutical interpretation of sacred architecture, the second title-"A Reassessment of the Simil- itude between Tula, Hidalgo and Chichen Itza, Yucatan"-refers to a much more specific historical problem, a famous and infamous prob- lem in Mesoamerican archaeology related to the uncanny resemblance between the architectural remains of two pre-Columbian cities that lie some 800 miles apart but that find no such similar counterparts any- where in between. In other words, the "problem" of the similitude be- tween the architectures of Tula, Hidalgo and Chichen Itza, Yucatan- or simply the "Tula-Chichen problem"-assuredly among a handful of the most enduring and most significant debates in the Mesoamerican field, lies in explaining the nature of the historical relatedness between

1 This article is the first installment of a two-part essay; the second half will appear in the May 1993 issue of History of Religions. The arguments I present need to be assessed in the context of the entire piece.

2 These are particularly poignant questions for the study of pre-Columbian Mesoamer- ican religion because there is, on the one hand, an enormous fund of architectural and ar- chaeological evidences-i.e., ruined monuments-yet, on the other hand, particularly in the Maya area (other than the abundant hieroglyphic inscriptions), a near-total void of contemporaneous written texts. Accordingly, in the Maya zone, architecture becomes, by its handsomeness and by default, the datum of priority.

208

This content downloaded from 140.254.87.149 on Wed, 14 Jun 2017 17:29:53 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

History of Religions

these two far-flung twin cities. In short, why do these two sets of pre- Hispanic buildings look so much alike when nothing between looks that way?

The conventional explanation of Tula-Chichen Itza relatedness, al- though there has never really been a consensus on the historical par- ticulars, holds that, at some point in the pre-Columbian past (perhaps the ninth or tenth century C.E.), a small but fiercely militant contingent of Toltec renegades from Tula marched out of their central Mexican homeland into the Yucatan Peninsula, where they overpowered the more intellectually predisposed Maya and then built (or forced the in- digenous Maya to build) that portion of Chichen Itza that so resembles the original Toltec capital of Tula. Despite burgeoning evidence that this tawdry tale of the so-called Toltec Conquest of the Maya corre- sponds only faintly, if at all, to anything that actually happened in pre- Hispanic Mesoamerica, scholars and tour guides alike continue to recite variations of this glamorous story with vigor and conviction. Nevertheless, while the historical problems about who was where when (let alone why) are fascinating in their own right-and a primer on those specific problems is forthcoming in the next few pages-it is the methodological even more than the historical dimensions of this fa-

mous debate that are fascinating to the comparative historian of reli- gions. And with that as a segue, the discussion returns to that initial set of broadly theoretical issues about the hermeneutical experience and the hermeneutical interpretation of sacred architecture.

METHODOLOGICAL PROBLEMS: THE HERMENEUTICAL EXPERIENCE OF

ARCHITECTURE

Like mothers of men, the buildings are good listeners. [ADRIAN STOKES, 1951]3

In the last analysis, Goethe's statement "Everything is a symbol" is the most comprehensive formulation of the hermeneutical idea. It means that everything points to another thing . . the universality of the hermeneutical perspective is all-encompassing. [HANS-GEORG GADAMER, 1964]4

Hermeneutical reflection arises from the encounter with strangeness or otherness. By the grace of hermeneutics, distant meanings are brought close, strangeness becomes familiar, and bridges arise between the

3 Adrian Stokes, Smooth and Rough (London: Faber & Faber, 1951); excerpt reprinted in The Image in Form: Selected Writings of Adrian Stokes, ed. Richard Wollheim (New York: Harper & Row, 1972), p. 74.

4 Hans-Georg Gadamer, "Aesthetics and Hermeneutics," in Philosophical Hermeneu- tics, trans. and ed. David E. Linge (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976), p. 103.

209

This content downloaded from 140.254.87.149 on Wed, 14 Jun 2017 17:29:53 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

The Hermeneutics of Sacred Architecture

once and the now. When the sense of a text, an action, or an institution

is immediately self-evident understanding proceeds unimpeded; inter- pretation is noncontroversial and no hermeneutical reflection is re- quired. But the sense of symbols and of religiohistorical phenomena is nearly always more elusive, at once beckoning us to understand and yet withholding the abundance of their meanings. This elusive double- ness of meaning-a conjoined familiarity and foreignness-gives rise to hermeneutical inquiry. Hermeneutical reflection involves, in other words, a circumstance in which a person feels interested or compelled to make sense of something or someone but in which the process of understanding meets resistance because the meanings of the situation are somehow obscured. When the process of human understanding meets resistance, that is, when meanings are not immediately apparent, the hermeneut is cast into a kind of questioning and being answered, a cycle of projection and revision as one catches glimpses of the object or circumstance of his/her attention, makes guesses or hypotheses about that circumstance, and then eventually has those guesses either confirmed or rejected after moving into position for a better view.

This sort of to-and-fro conversation process of hermeneutical under- standing may find its most technical and most self-conscious expres- sion in the interaction between scholars and the arcane texts that they aspire to decipher. Gadamer (among others) argues convincingly, how- ever, that this sort of dialogical process of understanding applies not simply to the scholar's critical interpretation of texts but to any circum- stance in which human beings have invested themselves in understand- ing objects and phenomena whose meanings are not immediately clear.5 Moreover, to cite Gadamer's own prime example (and to recall the quaint image of the little Mexican boy interrogating the stone an- gel), nowhere is the notion of dialogical, interactive, to-and-fro herme- neutical reflection more applicable than in the human experience of sacred architecture, in the human confrontation with a cathedral, a mosque, or a Mesoamerican pyramid whose fund of potential meanings is intriguing and profound but not at all obvious.6

5 David E. Klemm, Hermeneutical Inquiry (Atlanta: Scholars, 1986), traces the histor- ical evolution and "universalization to the hermeneutical problem" from Schleiermacher through Dilthey and Heidegger to Gadamer and Ricouer. See especially Hans-Georg Gadamer, "The Universality of the Hermeneutical Problem," in Philosophical Herme- neutics, pp. 3-17. In the same vein, Gerardus van der Leeuw, e.g., in his famous "Epile- gomena" to Religion in Essence and Manifestation, trans. J. E. Turner (Gloucester, Mass.: Smith, 1967), pp. 675-76, argued on the basis of his reading of Edmund Husserl that "phenomenology [like hermeneutics] is not a method that has been reflectively elab- orated but is man's true vital activity."

6 In the context of his discussion of the open and "eventful" character of works of art, Gadamer says that "we shall find the most plastic of the arts, architecture, especially

210

This content downloaded from 140.254.87.149 on Wed, 14 Jun 2017 17:29:53 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

History of Religions

THE SUPERABUNDANCE OF ARCHITECTURE

[Mesoamerican] architecture goes beyond metaphor; it is the space of power, sacred and secular; it is the meeting place of the real and the supernatural. Architecture becomes deity, as a ruler becomes a god. Architecture transcends the manifest elements of which it is composed in a way that is awesome to the imagination. [ELIZABETH P. BENSON, 1985]7

We have only to interpret that which has a multiplicity of meanings. [HANS-GEORG GADAMER, 1961]8

Thus the experience of art-and most especially the experience of ar- chitecture9-not only falls within the sweep of hermeneutical reflec- tion, it wins a priority in Gadamer's exposition of understanding because the experience of art lays bare that which is less obvious in other realms of understanding. According to Gadamer, works of art and architecture are available to endless reinterpretation and revalori- zation because they hold within them inexhaustible reservoirs of "on- tological possibility"; the work of art "stands open for ever new integrations" and buildings, like works of art, are loci from which "strangenesses" perpetually emerge. Thus, in remarks that are particu- larly relevant to the centuries-old architectural ruins of Mesoamerica, Gadamer argues: "The creator of a work of art may intend the public of his own time, but the real being of his work is what it is able to say, and this being reaches fundamentally beyond any historical confine- ment. In this sense, the work of art occupies a timeless present."10

Owing to this superabundance of meanings, religious monuments, especially those that endure over a long stretch of time, have a kind of autonomy, an independence or unpredictability, a "personality" of sorts. Religious buildings arise as human creations, but they persist as

instructive"; his remarks explicitly on architecture are, however, brief and difficult. See Gadamer, Truth and Method, trans. W. Glen-Doepel (London: Sheed & Ward, 1975), pp. 119, 138-42.

7 Elizabeth P. Benson, "Architecture as Metaphor," in Fifth Palenque Round Table, 1983, vol. 7, ed. Merle Grene Robertson (San Francisco: Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute, 1985), p. 199.

8 Hans-Georg Gadamer, "Composition and Interpretation," in The Relevance of the Beautiful and Other Essays, ed. Robert Bernasconi (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), p. 69.

9 It has been commonplace to attribute to architecture a special status among the arts by virtue of its unique complementary participation, on the one hand, in the "functional" realm of utility (i.e., shelter) and, on the other hand, in an aesthetic realm that transcends the merely practical. In the same vein, Gadamer, Truth and Method, pp. 138-42, consid- ers architecture to be the paramount exemplar of the revealment-concealment interplay that characterizes all hermeneutical reflection because a work of architecture is both a

very accessible element of the practical sphere of utility and a genuine work of art with an "excess of meaning."

10 Gadamer, "Aesthetics and Hermeneutics," p. 96.

211

This content downloaded from 140.254.87.149 on Wed, 14 Jun 2017 17:29:53 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

The Hermeneutics of Sacred Architecture

life-altering environments; they are, at once, expressions and sources of religious experience. As both created and creator, a religious build- ing manifests the aspirations and intentions of its builders, yet the meaning of a building "not occasionally, but always" surpasses those original intentions.1l For all the careful intentions of architects, build- ings-religious, civic, or otherwise-invariably (and usually almost immediately) spring free from those carefully contrived programs of meaning and begin to evoke feelings and ideas that had never even oc- curred to their original designers. We can well imagine, for instance, that whatever idiosyncratic issues about which the Mexican boy and the stone angel were conversing, it was not a conversation that had been anticipated by the seventeenth-century builders of the cathedral.12

The superabundance of religious monuments has profound con- sequences not simply for the experience of sacred architecture but, likewise, for the academic interpretation of sacred architecture. Appre- ciating the inherent versatility and inexhaustibility of, for instance, a pre-Columbian pyramid both threatens and enlivens its interpretation. The malleability, openness, and character of possibility within religious buildings ensures a wealth of meanings that will never be given over in their description as static constructional forms; in other words, even the most rudely honed megalithic menhirs do not just stand there mute and available for their once-and-for-all analysis as objects. Wrenched from its relatedness to human beings and to some particular function or cere- monial occasion, a religious building loses its meaning, or, more likely, its diverse meanings are set adrift without context or perspective. More- over, beyond the flux in meanings and functions between different cer- emonial occasions at a single monument, the decipherment of sacred architecture is complicated more still because, invariably, the built en- vironment simultaneously evokes a range of disparate meanings from the heterogeneous constituency that is experiencing it-obviously, for instance, the clergy, the committed laypersons, and the casual tourist each have very different experience of the mass in the Cuernavaca cathedral. Like actors in an intricately choreographed pageant, individ- uals and social factions play different roles and bring different pre- parednesses to their respective experiences of the architectonic world, and, not surprisingly, their sentiments and perceptions of that world are similarly variegated.

1 I borrow this phrase from Gadamer, Truth and Method, p. 280, where he is speak- ing of the inexhaustibility of texts.

12 In the phrasing of architectural semiology, "certain 'symbolic' functions, especially in ancient architecture, survive the obliteration of their actual connotative and denotative functions"; in other words, the original intention of a building is but the first of countless re-creations. See, e.g., Francoise Choay, "Urbanism and Semiology," in Meaning in Ar- chitecture, ed. Charles Jencks and George Baird (New York: Braziller, 1969), p. 31.

212

This content downloaded from 140.254.87.149 on Wed, 14 Jun 2017 17:29:53 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

History of Religions

That religious buildings invariably overstretch the original inten- tions of their builders to mean many different things in different his- torical epoches to different people, or even to the same person during different ritual circumstances, seems painfully obvious (whether we learn this from Gadamer or dozens of other theorists). Nevertheless, the failure to acknowledge the incontestable multivocality of monu- mental architecture has been perhaps the foremost obstacle in the reso- lution of the Tula-Chichen problem. Neglecting all too often to consider either the diversity of ritual circumstances in which various monuments must have participated or the diverse disposition of the various human actors (and fixating instead on the formal and technical properties of buildings),13 the art historical and archaeological litera- ture on pre-Columbian architecture (and Tula and Chichen Itza are hardly exceptions in this regard) is overbrimming with presumptions as to the meaning of this pyramid, or the significance of that serpent mo- tif, or the "real" message of this elaborate staircase.

Alternatively then, if historians of religions are to transcend this pre- occupation with the formal attributes of buildings and if we are to ap- preciate that the meanings of religious buildings are never disembodied from the situational context in which those meanings arise, then it is essential that we shift the inquiry away from the study of buildings per se, that is, physical forms of granite, limestone, wood, steel, or what- ever, and concentrate instead (in the spirit of Gadamer's inquiry into the "ontology of works of art") on the human experience of buildings. In other words, because buildings do not have one fixed meaning ("re- ligious" or otherwise) for all people in all times, it is essential that any study into the meanings of sacred architecture be constituted not in terms of static buildings (as though there were somehow one meaning per architectural form) but rather in terms of occasions, ritual circum- stances-or "ritual-architectural events," if you will-in which the buildings are active participants and some subset of the reservoir of potential meanings arises from those built forms.14 It is not, after all,

13 Irwin Panofsky's discussion of "the law of disjunction"-a principle derived from the observation that medieval European art borrowed forms from classical antiquity but assigned entirely different significances to those forms-illustrates in a quite different way both (1) that the hinge between architectural form and meaning is never locked tight and, consequently, (2) that to study and compare various architectures strictly on the ba- sis of their formal attributes is certain to lead to serious mistakes; see Panofsky, Renais- sance and Renascences in Western Art (Stockholm: Almquist & Wiksells, 1960); also see George Kubler, "Period, Style and Meaning…

Related Documents