-

8/3/2019 Psychosis Schz Neurology 1994

1/8

Epilepsy, psychosis,and schizophrenia:Clinical and neuropathologic correlationsC.J. Bruton, MD; Janice R. Stevens,MD; an d C.D. Frith, PhD

Article abstract-This study examines the relationship between epilepsy and psychosis. It compares clinical,EEG,and neuropathologic data from a group of subjects who had both epilepsy and psychosis with similar information fromanother group of patients who had epilepsy but no evidence of psychotic illness.We examined, blind to clinical diagno-sis, gross and microscopic material from whole-brain specimens from 10 patients diagnosed with epilepsy plusschizophrenia-like psychosis, nine subjects diagnosed with epilepsy plus epileptic psychosis, and 36 individuals withepilepsy (21 from an epileptic colony and 15 from the community at large) who had no history of psychosis (n= 10 + 9 +2 1 + 15= 55).We abstracted case histories without knowledge of pathologic findings. Epileptic colony patients had anearlier age at onset of seizures, while epileptic colony and epileptic psychosis patients had more frequent seizures.Epileptic individuals in the community died at a younger age than did epileptic patients in long-stay hospital care.Psychotic epileptic patients had larger cerebral ventricles, excess periventricular gliosis, and more focaI cerebral dam-age compared with epileptic patients who had no psychotic illness. Epileptic patients with schizophrenia-like psychosiswere distinguished from all other groups by a significant excess of pinpoint perivascular white-matter softenings.Wefound that mesial temporal sclerosis and temporal lobe epilepsy occurred with equal frequency in the psychotic andnonpsychotic groups; generalized seizures occurred more frequently in the psychotic epileptics and the epileptic colonyepileptics than in the community epileptic controls.

NEUROLOGY 1994;44:34-42

Despite many attempts to investigate the subject,the relationship between epilepsy and psychosis isunclear. The frequency of major psychopathologyfound in indiv iduals with epilepsy ha s variedgreatly from one study t o the next; it is very high inepileptic patient s from mental in stitu tions andhigh in subjects referred t o special epilepsy clinics,but it is only slightly greater than that of the gen-eral population i n epileptics who ar e trea ted bygeneral medical practitioners or who receive noregular medical care at all.S2 Nevertheless, sinceth e influen tial papers of Gibbs et al,3 Hill,4 andSlater and Beard,5 temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE)has been thought to carry a particularly high riskfor psychosis, including schizophrenia.6-10Otherclinical rep~rtsl-~ave not substantiated the in-creased risk, however, and the matte r remains con-troversial. Even after 30 years of debate, few prop-erly controlled studies of large epilepsy populationshave been published.In contrast t o th e widespread clinical inte rest,neuropathologists have seldom considered a linkbetween psychosis and epilepsy because, although

the pathology of epilepsy is well documented,18-22for many years there has been considerable doubtth at neuropathologic lesions occur at all in thebrains of patients who have schizophrenia. How-ever, during the last decade, well-controlled neu-roimaging and postmortem studies have convinc-ingly demonstrated the presence of structural ab-normalities in the brains of a significant number ofschizophrenic patients. These abnormalities in-clude enlargement of the lateral ventricles, en-largement of the third ventricle, and reduction inth e area or the volume of several limbic structures,notably the parahippocampal gyrus, the hippocam-pus, an d t he amygdaloid n ~ c l e u s . ~ ~ - ~ ~istologicstudies have also suggested the presence of exces-sive focal damage26 nd g l i o ~ i s ~ ~ , ~ ~nd a significantreduction in the number of nerve cells in the hip-p o c a m p u ~ , ~ ~he nucleus accumbens, and the dorso-medial nucleus of the thalamus.30 n addition, anexamination of temporal lobe tissue resected frompatients who had both intractable TLE and psy-chosis demonstrated a greater incidence of medialtemporal abnormalities that had occurred during

From the MRC Department of Neuropathology (Dr. Bruton ), Runwell Hospital, Wickford, and the Division of Psychiatry (Drs. Bruton and Frith), CRC,Harrow, U K the National Institute of Menta l Health (Dr. Stevens), St. Elizabeths Hospital, Washington, DC; and Oregon Healt h Sciences University(Dr. Stevens), Portland, OR .Supported by a gran t from the Stanley Foundation.Received April 28, 1993. Accepted for publication i n final form Jul y 19, 1993.Address correspondence and reprin t reques ts to Dr. C.J. Bruton, Neuropathology Department, Runwell Hospital, Wickford, Essex, SS11 7QE, UK.34 NEUROLOGY 44 January 1994

Epilepsy, psychosis,and schizophrenia:Clinical and neuropathologic correlations

C.J. Bruton, MD; Janice R. Stevens, MD; and C.D. Frith, PhD

Article abstract-This study examines the relationship between epilepsy and psychosis. I t compares clinical, EEG,and neuropathologic data from a group of subjects who had both epilepsy and psychosis with similar information fromanother group of patients who had epilepsy but no evidence of psychotic illness. We examined, blind to clinical diagnosis, gross and microscopic material from whole-brain specimens from 10 patients diagnosed with epilepsy plusschizophrenia-like psychosis, nine subjects diagnosed with epilepsy plus "epileptic psychosis," and 36 individuals withepilepsy (21 from an epileptic colony and 15 from the community at large) who had no history of psychosis (n =10 + 9 +21 + 15 =55). We abstracted case histories without knowledge of pathologic findings. Epileptic colony patients had anearlier age at onset of seizures, while epileptic colony and epileptic psychosis patients had more frequent seizures.Epileptic individuals in the community died at a younger age than did epileptic patients in long-stay hospital care.Psychotic epileptic patients had larger cerebral ventricles, excess periventricular gliosis, and more focal cerebral damage compared with epileptic patients who had no psychotic illness. Epileptic patients with schizophrenia-like psychosiswere distinguished from all other groups by a significant excess of pinpoint perivascular white-matter softenings. Wefound that mesial temporal sclerosis and temporal lobe epilepsy occurred with equal frequency in the psychotic andnon psychotic groups; generalized seizures occurred more frequently in the psychotic epileptics and the epileptic colonyepileptics than in the community epileptic controls.

Despite many attempts to investigate th e subject,the relationship between epilepsy and psychosis isunclear. The frequency of major psychopathologyfound in individuals with epilepsy has variedgreatly from one study to th e next; it is very high inepileptic patients from mental institutions andhigh in subjects referred to special epilepsy clinics,bu t it is only slightly greater than that of th e general population in epileptics who are treated bygeneral medical practitioners or who receive noregular medical care at all. 1,2 Nevertheless, sincethe influential papers of Gibbs et al,3 Hill,4 andSlater and Beard,5 temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE)ha s been thought to carry a particularly high riskfor psychosis, including schizophrenia.6.1o Otherclinical reports l1 .17 have not substantiated the increased risk, however, and the matter remains controversial. Even after 30 years of debate, few properly controlled studies of large epilepsy populationshave been published.In contrast to th e widespread clinical interest,neuropathologists have seldom considered a linkbetween psychosis and epilepsy because, although

NEUROLOGY 1994;44:34-42

th e pathology of epilepsy is well documented,18.22for many years there has been considerable doubtthat neuropathologic lesions occur at al l in th ebrains of patients who have schizophrenia. However, during the last decade, well-controlled neuroimaging an d postmortem studies have convincingly demonstrated th e presence of structural abnormalities in the brains of a significant number ofschizophrenic patients. These abnormalities include enlargement of the lateral ventritles, enlargement of the third ventricle, an d reduction inthe area or the volume of several limbic structures,notably the parahippocampal gyrus, the hippocampus, and the amygdaloid nucleus. 23.25 Histologicstudies have also suggested the presence of excessive focal damage26 an d gliosis27,28 an d a significantreduction in the number of nerve cells in the hippocampus,29 the nucleus accumbens, and the dorsomedial nucleus of the thalamus.30 In addition, anexamination of temporal lobe tissue resected frompatients who had both intractable TLE and psychosis demonstrated a greater incidence of medialtemporal abnormalities that ha d occurred during

From the MRC Department of Neuropathology (Dr, Bruto n), Runwell Hospital, Wickford, and the Division of Psychiatry (Drs, Bruton and Frith), CRC,Harrow, UK; the National Institute of Mental Health (Dr, Stevens), St, Elizabeth's Hospital, Washington, DC; and Oregon Health Sciences University(Dr, Stevens), Portland, OR.Supported by a grant from the Stanley Foundation,Received April 28, 1993, Accepted for publication in final form July 19, 1993,Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr, C.J, Bruton, Neuropathology Department, Runwell Hospital, Wickford, Essex, SSl l 7QE, UK34 NEUROLOGY 44 January 1994

-

8/3/2019 Psychosis Schz Neurology 1994

2/8

the fetal period or ea rly infancy among such pa-tients than amo n g ap p aren t ly similar t emp o ra llobectomy pati ents who did not hav e a psychotic ill-ness.31,32In this study, we investigated the relationshipbetwee n epilepsy a nd psychosis from a new per-spective, namel y that of a macroscopic and histo-logic assessment of postmortem whole-brain speci-mens from patients with a history of epilepsy whohad been hosp i ta l ized wi th psychosis comparedw i th a similar assessment of who le-brai n speci-mens f r o m a n o t h e r g r o u p of i n d i v i d ua l s withepilepsy who had no evi dence of psychosis. After wehad examined the case notes in detail, we under-took a neuropathologic investigation, blind to theclinical status of each patient. This had two objec-t ives: the first w a s t o assess the n a tu re , degree,and distribution of brain damage seen in the psy-chotic and the nonpsychotic patie nts with epilepsy;the second was to examine further those structura lan d neuroh isto log ic abnormal i t i es that h a v e re-cently become the focus of great in teres t in the in-vestigation of schizophrenic patients.Methods. Whole brains from 661 subjects with epilepsywere available for study. These form par t of an archive of8,000 psychiatric and neurologic brain specimens (theCorsellis collection) accumulated over a period of 40years (1950 t o 1990) in t he Department of Neuropathol-ogy a t Runwell Hospital, Essex, UK.Runwell Hospital is a la rge inst itution for the men-tally ill. The Neuropathology Department receives brainsfor study from deceased patients with various psychiatricdisorders, particularly schizophrenia and the senile psy-choses. In addition, under the direction of ProfessorJ.A.N. Corsellis, the laboratory has fo r many years had aspecial interest in the study of epilepsy. As a result,brains from patients with epilepsy were received not onlyfrom Runwell Hospital but also from general hospitals,coroners departments, neurosurgical units, and long-stay epilepsy instituti ons (epileptic colonies) in theGreater London area.Clinical. The case records of all 661 patients were firstscreened, without knowledge of the neuropathologic diag-nosis, for evidence of epilepsy and psychosis. Cases wereexcluded from further study if the clinical data were in-complete or if only a part of the brain were available forstu dy ( ie , following temporal lobectomy). All pat ient sunder age 18 at death and all patients who were men-tally retarded were similarly excluded. Of the originalsample of 661 patients with epilepsy, 75 individuals metthe study criteria: age 218 years a t death, availability ofthe entire brain specimen, satisfactory clinical notes, andevidence of both psychosis and epilepsy. For nonpsy-chotic epileptic controls, two groups were available: indi-viduals who had been inpatients at long-stay epilepticcolonies and whose case notes showed no evidence of apsychotic illness (n = 21) and individuals with epilepsywho had lived in the community at large until death andwho had no history of psychiatric disease ( n= 15).The case notes of these subjects (n = 75 + 21 + 15 =111)were examined in detail by J.R.S. and C.J.B. Psy-chiatric symptoms were assessed according t o DSM 111-R33 criteria. Of the 75 patients whose clinical notes men-tioned both psychosis and epilepsy, only 27 (4% of theoriginal sample of 661) had fully documented evidence of

a long-standing interictal psychotic illness in addition t olong-standing epilepsy, Forty-eight of the 75 patientswere excluded, most often because seizures had occurredfo r the first time a few months before death (13 individu-als). Schizophrenic patients whose epilepsy began shortlyafter prefrontal leukotomy were also removed from thestudy, as were all cases of dementia, mental retardation,and inadequate clinical history. Of the remaining 27 pa-tients who had both psychosis and epilepsy, 10 individu-al s (1.5% f the original sample) had psychotic symptomsthat were indistinguishable from DSM 111-R schizophre-nia apa rt from the additional diagnosis of epilepsy (group1, the schizophrenia-psychosis group).A furthe r nine pa-tients had been considered by their attending physicianst o be suffering from a n epilep tic psychosis. Many ofthese patients did n o t meet the DSM 111-R criteria fo rschizophrenia and would currently be classified as hav-ing organic psychoses (group 2, the epileptic-organic psy-chosis group). The remaining eight subjects conformed t ocriteria for other major psychoses-ie, depression (thre epatients), manic depression (two patie nts), or paranoidstate (three patients). As noted above, there were twogroups of patients who had epilepsy without psychosis-21 long-stay inpatients from an epileptic colony (group 3,the epileptic colony gr oup) an d 15 individuals withepilepsy who had lived and often worked in the commu-nity and had no recorded history of mental illness (group4, he community epilepsy group). Brains from th is la stcohort of patients were se nt to Runwell from general hos-pitals or were coroners cases.The diagnosis of epilepsy was made on the case notehistory, which frequently included descriptions ofseizures given by hospital staff o r family members.Seizures had been classified as g rand mal, petit mal,minor, or psychomotor in accordance with criter ia a t thetime of hospitalization or medical care. EEGs had beenrecorded on 4-, -, or 8-channel electroencephalographs.EEG data were obtained from factual reports written a tthe time of recording; original EEG recordings were notavailable for examination.Neuropathology. The brains of all 661 patients hadbeen reported a s part of routine departmental procedure;some epileptic colony cases had also formed part of theepilepsy study by Margerison and Corsellis.20 For thepurposes of the present investigation, we coded thebrains, macroscopic reports, photographs, and histologicslides and then reassessed them without knowledge ofthe clinical history. Extensive bilateral blocks for cel-loidin and paraffin embedding had been taken in manycases; where necessary, we took further blocks so thatrepresentative bilateral histology would be availablefrom the frontal, occipital, and temporal lobes and thecerebellum and midbrain. We stained microscopic sec-tions using histologic techniques including Nisslsmethod using cresyl violet, hematoxylin and eosin, vanGieson, Heidenhain-Woelcke for myelin, and Holzersmethod for fibrous glia. Frozen sections from the frontal,parietal, and temporal lobes were stained by von Braun-miihls method for plaques and tangles.We carefully identified both the type and the lateral-ity of any visible abnormality. On naked-eye examina-tion, we paid particular attention t o cortical atrophy,ventricular size, and the degree and distribution of focalpathology. Microscopic assessment took special accountof nerve cell loss and gliosis in the cortex and basal gan-glia; gliosis and focal damage in the white matter, theperiventricular regions, th e temporal lobes, and the cere-bellum; and the degree of vascular and senile change.

January 1994 NEUROLOGY 44 35

the fetal period or early infancy among such patients than among apparently similar temporallobectomy patients who did not have a psychotic ilJ-ness.31,32In this study, we investigated the relationshipbetween epilepsy an d psychosis from a new perspective, namely that of a macroscopic and histologic assessment of postmortem whole-brain specimens from patients with a history of epilepsy whohad been hospitalized with psychosis compared

with a similar assessment of whole-brain specimens from another group of individuals withepilepsy who had no evidence of psychosis. After weha d examined the case notes in detail, we undertook a neuropathologic inv!,stigation, blind to th eclinical status of each patient. This had two objectives: the first was to assess the nature, degree,and distribution of brain damage seen in th e psychotic and the nonpsychotic patients with epilepsy;the second was to examine further those structuraland neurohistologic abnormalities that have recently become the focus of great interest in the investigation of schizophrenic patients.Methods. Whole brains from 661 subjects with epilepsywere available for study. These form part of an archive of8,000 psychiatric an d neurologic brain specimens (theCorsellis collection) accumulated over a period of 40years (1950 to 1990} in the Department of Neuropathol-ogy at Runwell Hospital, UK.Runwell Hospital is a large institution for the mentally ill. The Neuropathology Department receives brainsfor study from deceased patients with various psychiatricdisorders, particularly schizophrenia and the senile psychoses. In addition, under the direction of ProfessorJ.A.N. Corsellis, th e laboratory has for many years had aspecial interest in the study of epilepsy. As a result,brains from patients with epilepsy were received not onlyfrom Runwell Hospital bu t also from genera] hospitals,coroners' departments, neurosurgical units, and longstay epilepsy institutions ("epileptic colonies") in theGreater London area .Clinical. The case records of all 661 patients were firstscreened, without knowledge of the neuropathologic diagnosis, for evidence of epilepsy an d psychosis. Cases wereexcluded from further study if the clinical data were incomplete or if only a part of the brain were available forstudy (ie, following temporal lobectomy). All patientsunder age 18 at death an d all patients who were mentally retarded were similarly excluded. Of the originalsample of 661 patients with epilepsy, 75 individuals me tthe study criteria: age :2:18 years at death, availability ofthe entire brain specimen, satisfactory clinical notes, andevidence of both psychosis an d epilepsy. For nonpsychotic epileptic controls, two groups were available: individuals who had been inpatients at long-stay epilepticcolonies and whose case notes showed no evidence of apsychotic illness (n = 21) and individuals with epilepsywho had lived in the community at large until death andwho had no history of psychiatric di sease (n =15).The case notes of these subjects (n = 75 + 21 + 15 =1111 were examined in detail by J.R.S. and C.J.B. Psychiatric symptoms were assessed according to DSM IIIR33 criteria. Of the 75 patients whose clinical notes mentioned both psychosis an d epilepsy, only 27 (4% of theoriginal sample of 661) had fully documented evidence of

a long-standing interictal psychotic illness in addition tolong-standing epilepsy. Forty-eight of th e 75 patientswere excluded, most often because seizures had occurredfor the first time a few months before death (1 3 individuals). Schizophrenic patients whose epilepsy began shortlyafter prefrontal leukotomy were also removed from th estudy, as were all cases of dementia, mental retardation,and inadequate clinical history. Of the remaining 27 patients who had both psychosis an d epilepsy, 10 individuals (1.5% of th e original sample) had psychotic symptomsthat were indistinguishable from DSM IIl-R schizophrenia apart from the additional diagnosis of epilepsy (group1, the schizophrenia-psychosis group). A further nine patients had been considered by their attending physiciansto be suffering from an "epileptic" psychosis. Many ofthese patients did not meet the DSM III-R criteria forschizophrenia and would currently be classified as having organic psychoses (group 2, the epileptic-organic psychosis group). The remaining eight subjects conformed tocriteria for other major psychoses-ie, depression (threepatients), manic depression (two patients), or paranoidstate (three patients). As noted above, there were twogroups of patients who had epilepsy without psychosis-21 long-stay inpatients from an epileptic colony (group 3,th e epileptic colony group) an d 15 individuals withepilepsy who had lived an d often worked in the community and had no recorded history of mental illness (group4, the community epilepsy group). Brains from this lastcohort of patients were sent to Runwell from general hospitals or were coroners' cases.The diagnosis of epilepsy was made on th e case notehistory, which frequently included descriptions ofseizures given by hospital staff or family members.Seizures ha d been classified as grand mal, petit mal,minor, or psychomotor in accordance with criteria at th etime of hospitalization or medical care. EEGs ha d beenrecorded on 4-, 5-, or 8-channel electroencephalographs.EEG data were obtained from factual reports written atthe time of recording; original EEG recordings were notavailable for examination,Neuropathology. The brains of all 661 patients hadbeen reported as part of routine departmental procedure;some epileptic colony cases ha d also formed part of theepilepsy study by Margerison an d Corsellis.20 For thepurposes of the present investigation, we coded th ebrains, macroscopic reports, photographs, and histologicslides and then reassessed them without knowledge ofth e clinical history. Extensive bilateral blocks for celloidin and paraffin embedding had been taken in manycases; where necessary, we took further blocks so thatrepresentative bilateral histology would be availablefrom th e frontal, occipital, an d temporal lobes and thecerebellum an d midbrain. We stained microscopic sections using histologic techniques including Nissl'smethod using cresyl violet, hematoxylin an d eosin, vanGieson, Heidenhain-Woelcke for myelin, and Holzer'smethod for fibrous glia. Frozen sections from the frontal,parietal, and temporal lobes were stained by von Braunmtihl's method for plaques and tangles.We carefully identified both the type and the laterality of any visible abnormality. On naked-eye examination, we paid particular attention to cortical atrophy,ventricular size, and the degree and distribution of focalpathology. Microscopic assessment took special accountof nerve cell loss and gliosis in the cortex and basal ganglia; gliosis and focal damage in the white matter, th eperiventricular regions, the temporal lobes, an d the cerebellum; and the degree of vascular an d senile change.

January 1994 NEUROLOGY 4435

-

8/3/2019 Psychosis Schz Neurology 1994

3/8

Table 1. Clinical featuresGroup 1:Schizophrenia-psychosis

Number of cases 10Mean age at death iyr) 60Average age at onset 15Sex

of epilepsy (yr)Male 3Female 7

Average fit frequency1 (1-3per year)2 (4-12 per ye ar)3 (2-5per month)4 (6 per month 1

Duration of epilepsybefore psychosis (yrH

2.1

Mean/Median 21120.5Range 5-38

Clinical type of epilepsyMajor (g rand mall 100%Psychomotor ( T L E ) 20%Minor (pe tit mall 40%* Denotes significant differences.t One patient developed schizophrenia before epilepsyNS Not significant.

Group 2:Epilep ic-organicpsychosis

96713

45

3.1

17.3115.57-42100%11%33%

Group 3:Epilepticcolony

2161

7

912

3.2*

--95%15%43%

Group 4:Communityepileptics

154523

78

2.2

--73%*13813%

p Values

p < 0.001*p < 0.01*

NS

p < 0.05

NS

p < 0.02NSNS

Pertinent medical data, clinical and family history, di-agnosis, details of medical treatment, and details ofphysical o r neurologic examinations were extracted andcoded. We similarly coded EEG data fo r subsequent anal-ysis and correlation with the neuropathologic findings.Statistical information was processed by C.D.F . usingdata analysis packages incorporated in BMDP. We usedanalysis of variance f o r continuous measures andFishers exact test fo r frequencies.Results. The clinical comparisons between groupsare summarized in table 1. The group 3 epilepticcolony patients had the youngest age at onset offirst seizure (mean age = 7 years; p < 0.01). Age a tdeath also differed significantly between groups;the group 4 community epilepsy subjects (averageage at death = 45 year s) died at a significantlyyounger age ( p < 0.001) th an did subjects in groups1 through 3 , who were all long-stay hospital pa-tients and who had average ages at de ath of 60,67,and 61 years. These figures correspond closely tothe national average age at death for communityand hospitalized epileptic patients in England andWales (personal communication from the StatisticsDivision, Office of Population Censuses and Sur-veys, UK) . Seizure type and frequency also varied;grand ma1 seizures, present in 73% of communitygroup patients, were significantly less common inthe community group th an in the o ther threegroups ( p < 0.02). Furthermore, the seizure fre-quencies of both the community patients and thegroup 1 schizophrenia-psychosis patients were sig-nificantly lower than the seizure frequencies re-ported in the group 3 epileptic colony and th e group36NEUROLOGY 44 January 1994

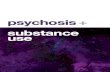

2 epileptic-organic psychosis subjects ( p < 0.05 inboth cases).Blunted affect ( p < 0.05), delusions ( p < 0.08)and incoherent speech ( p < 0.07) were all more fre-quent in the schizophrenia-psychosis subjects; irri-tability and aggression were more common in theepileptic-organic psychosis group ( p < 0.01 .The clinicopathologic correlations are itemizedin table 2 . For convenience, the neuropathologicfindings have been subdivided into typical epilep-tic damage and o ther, nonepileptic pathologies.(I n our study, typical epileptic pathology includescerebellar atrophy or gliosis, cortical scar forma-tion, Ammons horn [or hippocampall sclerosis [fig-ure 11, and mesial temporal sclerosis (MTS). MTS34incorporates both classic Ammons horn sclerosisz0and end folium sclerosis,2oalong with more wide-spread medial temporal pathology such as nervecell loss and gliosis occurring in the uncus, theamygdaloid nucleus, or the cortex of the medialtemporal gyri. However, table 2 presents the da tafor Ammons horn sclerosis and amygdaloid pathol-ogy separately.)Our da ta show th at the frequency and the degreeof typical epileptic damage did not differ betweengroups a pa rt from the occurrence of cerebellar glio-sis, which was seen less frequently in the brains ofepileptic subjects who lived in the community ( p

-

8/3/2019 Psychosis Schz Neurology 1994

4/8

able2. Pathology: Psychotic groupsand controls

Epileptic damageAmmons hornsclerosisAmygdaloid sclerosisCortical scarsCerebellumVentricularNonepileptic damageenlargementPeriventriculargliosisWhite-matter disease(small vessel)Miscellaneous macroscopicabnormalitiesCongenitalAcquiredNone

Group 1:Schizophrenia-psychosisL R

Group 2:Epileptic-organicpsychosisL R

30% 20% 33% 33%

NS Not simiticant.* Denotes significant differences.

30% 40% 44% 33%0 0 11% 22%40% 40% 22% 22%

80% 78%70% 67%60%* 11%

10%30%60%

22%44%34%

Group 3 Group 4:Epileptic Communitycolony epilepticsL R L R p Values

14% 19% 20% 13% NS20% 48% 27% 20% NS10% 15% 20% 27% NS25% 35% 7%* 7%* p

-

8/3/2019 Psychosis Schz Neurology 1994

5/8

A summary of the clinical and neuropathologicdata for each individual in the series is containedin NAPS file no. 05035 (see Note at end of article).Discussion. This clinicopathologic study examinesthe nature, degree, and distribution of brain damagein psychotic and nonpsychotic epileptic patients andinvestigat es the morphologic sub str at e of theschizophrenia-like psychoses seen in some patientswho have epilepsy.As part of this investigation, weconsider it pertinent to discuss our results in thelight of the large body of evidence produced by Slaterand Beard5 and to answer two important questions:1. Given the widespread bel ief that theschizophrenia-like psychoses of epilepsy are partic-ularly associated with temporal lobe seizures, istemporal lobe brain damage found more often in in-dividuals who have both epilepsy and psychosisthan in individuals with epilepsy who show no evi-dence of psychotic disease?

2. Is it possible to identify any clinical or neu-ropathologic characteristic that can distinguish in-dividuals who have both epilepsy and psychosis38NEUROLOGY 44 January 1994

from individuals with epilepsy who have no evi-dence of a psychotic disorder?To the first question, the answer provided by ourdata is negative. Temporal lobe pathology in generaland MTS, either unilateral or bilateral, occurredwith equal frequency in all four groups studied. Nei-ther was a history of TLE more common in theschizophrenic patients, 100%of whom had general-ized seizures with o r without other seizure types.This last finding is consistent with the 1963 reportof Slater and Beard,5 who noted that although 70%of their patients with schizophrenia-like psychosisand epilepsy had temporal lobe seizures, these indi-viduals also suffered from generalized attacks. Theremaining 30% of their patients had either general-ized, other focal, o r petit ma1 seizures; only five oftheir 69 patients had no generalized attacks.The mean interval between the onset of seizuresand the onset of schizophrenia-like psychosis inthis study was 21 years (17 years between onset ofseizures and development of epileptic psychosis).Slater and Beard,5 who calculated the onset ofepilepsy from the time of onset of established

A

A summary of the clinical an d neuropathologicdata for each individual in the series is containedin NAPS file no. 05035 (see Note at end of article).Discussion. This clinicopathologic study examinesthe nature, degree, and distribution of brain damagein psychotic and nonpsychotic epileptic patients andinvestigates the morphologic substrate of theschizophrenia-like psychoses seen in some patientswho have epilepsy. As part of this investigation, weconsider it pertinent to discuss our results in thelight of the large body of evidence produced by Slaterand Beards and tAl answer two important questions:1. Given the widespread belief that theschizophrenia-like psychoses of epilepsy are particularly associated with temporal lobe seizures, istemporal lobe brain damage found more often in individuals who have both epilepsy an d psychosisthan in individuals with epilepsy who show no evidence of psychotic disease?

2. Is it possible to identify any clinical or neuropathologic characteristi.c that can distinguish individuals who have both epilepsy and psychosis38 NEUROLOGY 44 January 1994

B

Figure 2. (IV Corolllll sliu of I",un ahowiTlif multipll pinpoinJIO/t.eninlJl1 (PIN) in u m p o r a l l D ~ nw/ur. Th.t middle CIIrrbroJ ~ r y fAlCAI &hOWI1 a t h . t r o ~ thidf1li l\fof it . waJJ.a.(AlQjfIIifiallilm xl.6 btt{ort 44% reducMn) (8 ) L o w - ~ r myelindGin ofoccipital I . 1wwi11ll n u m e ~ pillpOinl ~ r U n 8 " { } [ ~ i o n )(1.6 bttforr 91% redudicn) fe) High.trpOUJfT ofpinpoinlllO/f.eni"lIt IMwi11ll m o d e ~ l y thi.cJI-wolled Iie'HI.,U/"POIUIlUd by r : n J . a ~ ~ r i 4 J 0 8 C U / . a r ~ p a . c u . (MQ61Ii/'icoIioII x20before 49% redu.ctiortJ (All pGlIIlh dIIpid , p e c i ~ ~ from CCM 8. )

from individuals with epilepsy who have no evidence of a psychotic disorder?To the first question, the answer provided by ourdata is negative. Temporal lobe pathology in generaland MTS, either unilateral or bilateral, occurredwith equal frequency in all four groups studied. Neither wa s a history of TLE more common in theschizophrenic patients, 100% of whom had generalized seizures with or without other seizure types.This last finding is consistent with the 1963 reportof Slater and Beard} who noted that although 70%of their patients with schizophrenia-like psychosisand epilepsy had temporal lobe seizures, these individuals also suffered from generalized attacks. Theremaining 30% of their patients had either generalized, other focal. or petit mal seizures; only five oftheir 69 patients had no generalized attacks.The mean interval between the onset of seizuresan d th e onset of schizophrenia-like psychosis inthis study was 21 years (17 years between onset ofseizures an d development of epileptic psychosis).Slater and B e a r d , ~ who calculated th e onset ofepilepsy from th e time of onset of established

-

8/3/2019 Psychosis Schz Neurology 1994

6/8

seizures, reported an average of 14 years to the de-velopment of a schizophrenia-like psychosis. How-ever, as Taylor35has pointed out, this statistic isrelatively meaningless as it represents an averagetaken from a wide range of time ( in our case, from5 t o 38 years) and thus does not suggest a direct re-lationship between the duration of epilepsy and theonset of psychosis. The seizure frequency, whileequally high in the epileptic-organic psychosis andthe epileptic colony groups ( a n average of two tofive seizures per month) was significantly lower inthe schizophrenic psychosis and the community pa-tients ( an average of four t o 12 seizures per year).As for the second question, while certain clinicalfeatures such as the early age at onset and the fre-quency of seizures did distinguish the epilepticcolony and the epileptic-organic psychosis patientsfrom the community controls, neither family his-t o ry of psychosis, nor history of birth o r head in-jury, nor an episode of status epilepticus distin-guished the schizophrenia-like psychosis patientsfrom the other groups.Neuropathologically, however, three featuresemerged that separated the psychotic patients fromthe tw o nonpsychotic groups: enlarged ventricles,periventricular gliosis, and an excess of acquiredfocal brain damage. These features cannot be at-tributed solely to the age difference between thepsychotic and nonpsychotic groups, a s the nonpsy-chotic epileptic colony patients of group 3 did notshow a similar degree of ventricular enlargement,periventricular gliosis, o r focal damage despite asimilar age at death. The group 1 schizophrenia-like psychosis patients were further distinguishedneuropathologically from all other groups by a sig-nificant excess of minute perivascular white-mattersoftenings. These tiny punctate lesions (figure 21,found around thick-walled small vessels through-out the white matter, are the result of widespreadsmall-vessel disease. They would generally be con-sidered an age-related phenomenon; theschizophrenia-psychosis patients had a mean ageat death of 60 years. However, similar lesions wererare or absent in the epileptic-organic psychosisand the epileptic colony patients (groups 2 and 3),who were of equal o r greater age at death.Although we know of no previous clinicopatho-logic comparison of whole-brain specimens of pa-tients with epilepsy and psychosis, the neuropatho-logic data from the present study give general sup-port to the evidence of previous epilepsy-psychosisinvestigation^^,^^,^^ tha t show that psychosis is asso-ciated with enlargement of the lateral ventricles, anabnormality that has been attributed to subcorticalbrain damage.5.36Apart from excess fibrous gliosisin the periventricular and periaqueductal regions,we found no special relationship between psychosisand histopathology in any specific subcortical orcortical structure. In this respect, our findings sup-port those in separate studies by Stevensz8and byBruton et a1,26 who described excess gliosis of theperiventricular regions in the brains of patients

with true schizophrenia. These authors consideredthe various etiologic implications of periventriculargliosis, including the possibility of a viral pathogen.Data from the present investigation further sup-port the findings of Bruton et a1,26who found signifi-cantly increased acquired focal pathology in thebrains of a group of schizophrenic patients comparedwith an age- and sex-matched group of normal con-trols. The neuropathologic data from the presentstudy, although retrospective, are from a totally dif-ferent cohort of patients yet have the advantage ofincluding two negative comparison groups (nos. 3and 4) ho were handicapped by epilepsy but had noevidence of psychotic illness. We assume that our re-sults a re valid and recommend th at excess acquiredfocal brain damage now be studied alongsideperiventricular fibrous gliosis, ventricular enlarge-ment, and reduced cerebral size in the search for theneuropathologic substrate of psychosis.Two additional findings emerged from our clini-copathologic study. The first of these, mentionedabove, was the significant increase of widespreadsmall-vessel disease in the cerebral white matter ofthe group 1 schizophrenia-like psychosis patientswhen compared with the three other groups. Itwould be easy and perhaps tempting t o dismiss thisapparently specific statistical association as fortu-itous were it not fo r the past work of B r u e t ~ c h , ~van der H o r ~ t , ~ ~nd Bini and Ma r~ hia fa va ,~ ~horeported excess widespread small-vessel diseasewith enlargement of perivascular spaces and withsmall foci of demyelination in the brains of a pro-portion of patients with schizophrenia. These au-thors a t t r ibu ted th e small-vessel disease torheumatic endarteritis, although this assertion waslater rejected (see C ~ r s e l l i s ~ ~or review). Other evi-dence that diffuse white-matter pathology may beassociated with psychosis was recently presented byHyde et al,42who suggested that the psychosis com-monly seen in patients with adult-onset metachro-matic leukodystrophy may be r elated to thewidespread foci of white-matter demyelination thatcharacterize this disease. The presence of diffusewhite-matter pathology may, in some cases, alsocontribute t o the degree of ventricular enlargementwidely reported in patients with schizophrenia. It isa matter of debate whether this or other reportedforms of acquired brain damage in patients withschizophrenia or schizophrenia-like p s y ~ h o s i s ~ , ~ ~rerelevant to the clinical symptoms of psychosis, t othe underlying disease process itself, t o the effectsof treatment, or t o some other confounding factor,such as the effect of excessive tobacco smoking socommonly found in patients with s~hizophrenia.~In our opinion, however, excess acquired cerebralpathology has been reported too often in patientswith psychosis t o be dismissed out of hand.The second additional finding to emerge from ourstudy was th at frequency, degree, and type of tem-poral lobe damage in the schizophrenic and otherpsychotic patients did not differ from that found inthe two nonpsychotic epilepsy groups or from that

January 1994 NEUROLOGY 4439

seizures, reported an average of 14 years to the development of a schizophrenia-like psychosis. However, as Taylor35 has pointed out, this statistic isrelatively meaningless as it represents an averagetaken from a wide range of time (in our case, from5 to 38 years) an d thus does not suggest a direct relationship between th e duration of epilepsy and theonset of psychosis. The seizure frequency, whileequally high in the epileptic-organic psychosis andthe epileptic colony groups (an average of two tofive seizures per month) was significantly lower inthe schizophrenic psychosis and the community patients (an average of four to 12 seizures per year).As for th e second question, while certain clinicalfeatures such as the early age at onset and the frequency of seizures did distinguish th e epilepticcolony and the epileptic-organic psychosis patientsfrom th e community controls, neither family history of psychosis, nor history of birth or head injury, nor an episode of status epilepticus distinguished the schizophrenia-like psychosis patientsfrom the other groups.Neuropathologically, however, three featuresemerged that separated th e psychotic patients fromthe two nonpsychotic groups: enlarged ventricles,periventricular gliosis, and an excess of acquiredfocal brain damage. These features cannot be at tributed solely to th e age difference between th epsychotic and nonpsychotic groups, as the nonpsychotic epileptic colony patients of group 3 did no tshow a similar degree of ventricular enlargement,periventricular gliosis, or focal damage despite asimilar age at death. The group 1 schizophrenialike psychosis patients were further distinguishedneuropathologically from all other groups by a significant excess of minute perivascular white-mattersoftenings. These tiny punctate lesions (figure 2),found around thick-walled small vessels throughout th e white matter, are th e result of widespreadsmall-vessel disease. They would generally be considered an age-related phenomenon; theschizophrenia-psychosis patients ha d a mean ageat death of 60 years. However, similar lesions wererare or absent in th e epileptic-organic psychosisand the epileptic colony patients (groups 2 and 3),who were of equal or greater age at death.Although we know of no previous clinicopathologic comparison of whole-brain specimens of patients with epilepsy an d psychosis, th e neuropathologic data from th e present study give general support to the evidence of previous epilepsy-psychosisinvestigations S,36,37 that show that psychosis is associated with enlargement of the lateral ventricles, anabnormality that has been attributed to subcorticalbrain damage.5,36 Apart from excess fibrous gliosisin the periventricular and periaqueductal regions,we found no special relationship between psychosisand histopathology in any specific subcortical orcortical structure. In this respect, our findings support those in separate studies by Stevens28 and byBruton et al,26 who described excess gliosis of theperiventricular regions in the brains of patients

with "true" schizophrenia. These authors consideredthe various etiologic implications of periventriculargliosis, including th e possibility of a viral pathogen.Data from the present investigation further support the findings of Bruton et al,26 who found significantly increased acquired focal pathology in thebrains of a group of schizophrenic patients comparedwith an age- an d sex-matched group of normal controls. The neuropathologic data from the presentstudy, although retrospective, are from a totally different cohort of patients yet have the advantage ofincluding two negative comparison groups (nos. 3and 4) who were handicapped by epilepsy but ha d noevidence of psychotic illness. We assume that our results are valid an d recommend that excess acquiredfocal brain damage no w be studied alongsideperiventricular fibrous gliosis, ventricular enlargement, and reduced cerebral size in the search for theneuropathologic substrate of psychosis.Two additional findings emerged from our clinicopathologic study. The first of these, mentionedabove, was th e significant increase of widespreadsmall-vessel disease in the cerebral white matter ofthe group 1 schizophrenia-like psychosis patientswhen compared with the three other groups. Itwould be easy an d perhaps tempting to dismiss thisapparently specific statistical association as fortuitous were it no t for the past work of Bruetsch,38van der Horst,39 an d Bini an d Marchiafava,40 whoreported excess widespread small-vessel diseasewith enlargement of perivascular spaces and withsmall foci of demyelination in th e brains of a proportion of patients with schizophrenia. These authors attributed the small-vessel disease torheumatic endarteritis, although this assertion waslater rejected (see Corsellis41 for review). Other evidence that diffuse white-matter pathology ma y beassociated with psychosis was recently presented byHyde et al,42 who suggested that th e psychosis commonly seen in patients with adult-onset metachromatic leUkodystrophy may be related to thewidespread foci of white-matter demyelination thatcharacterize this disease. The presence of diffusewhite-matter pathology may, in some cases, alsocontribute to th e degree of ventricular enlargementwidely reported in patients with schizophrenia. I t isa matter of debate whether this or other reportedforms of acquired brain damage in patients withschizophrenia or schizophrenia-like psychosis2,43 arerelevant to the clinical symptoms of psychosis, tothe underlying disease process itself, to the effectsof treatment, or to some other confounding factor,such as the effect of excessive tobacco smoking socommonly found in patients with schizophrenia.44In our opinion, however, excess acquired cerebralpathology ha s been reported too often in patientswith psychosis to be dismissed out of hand.The second additional finding to emerge from ourstudy was that frequency, degree, and type of temporal lobe damage in the schizophrenic and otherpsychotic patients did not differ from that found inth e two nonpsychotic epilepsy groups or from that

January 1994 NEUROLOGY 44 39

-

8/3/2019 Psychosis Schz Neurology 1994

7/8

described in patients with epilepsy since the time ofSommer18 and of S~ ie 1m ey er .l ~his information,combined with the absence of pathologic lesions lo-calized t o the frontal o r other specific areas, sug-gests that neither MTS nor macroscopic frontal lobepathology is critical t o the development of psychosisin epilepsy. This is not so surprising, however, for inschizophrenia, despite the presence of a small-sizedor dysplastic hippocampus or parahippocampalgyrus in a percentage of the patients studied, bothMTS an d frontal lobe lesions ar e ~ n c o m m o n ~ ~ , ~ ~ , ~ ~and the cause of the lateral ventricular enlargementremains unknown. We found MTS in 40% to 50% ofall four epileptic groups; this figure comparesclosely with the findings of other epilepsy studies byFalconer,jG Veith,47 Margerison and Corsellis,20 ndBrutomZzThere are other ways in which our find-ings do not support the widely accepted belief thatTLE particularly predisposes t o schizophrenia. P ar-tial (including temporal lobe) seizures were no morecommon in our schizophrenia-like psychosis pa-tients t han in our most (normalgroup of epileptics,ie, those who lived in the community. Furthermore,although Taylor et a148and B r u t ~ n ~ ~ound tha t con-genital malformations, especially gangliogliomasand hamartomas, were overrepresented in the tem-poral lobes removed at surgery from patients withepilepsy and psychosis, we found no similar lesionsamong the 27 patients with psychosis (including 10with schizophrenia-like psychosis) in th e presentstudy. Possible reasons for this discrepancy may bedue t o selection bias; the cases of both Taylor et a1and Bruton were selected for temporal lobe surgerybecause of intractability of TLE and thus, in con-trast to the earlier Slater and Beard study,5did notinclude patients who had other types of epilepsy. Aparticularly forceful case for relationship betweenTLE and psychosis was also made by Perez andTrimble.*JoThe schizophrenia-like psychoses theyreported differed greatly from those of the chronic,hospitalized patients in our study. Diagnosed by thePresent St ate Examination as having nuclearschizophrenia,8most of their patients were outpa-tients who lived and often worked in the commu-nity, many without long-term neuroleptic medica-tion. In contrast, our patients were chronic, oftendeteriorated schizophrenics, confined to a mentalhospital and generally receiving antipsychotic aswell as anticonvulsant medication. The absence of asignificant increase in temporal lobe pathology inour patients appears t o be powerful evidenceagainst a discrete connection between TLE, tempo-ral lobe pathology, and schizophrenia as Kraepelindefined the disorder. Several investigators have re-ported evidence for a preponderance of left-sidedanatomic abnormality in and inthe schizophrenia-l ike psychoses of e p i l e p ~ y . ~ ~ , ~ ~However, no evidence of lateralization of pathologyappeared in this pathologic study of whole brains.Our findings are compatible with those of Kris-tensen and S i n d r ~ p , ~ ~ho compared pneumoen-cephalograms from nearly 200 TLE patients, one-40 NEUROLOGY 44 January 1994

half with and one-half without psychosis, and re-ported diffuse ventricular enlargement without lat-eralizatio n of pathology as the distinguishinganatomic feature of patients with psychosis.Aggressive, violent, and impulsive behavior wasgenerally considered t o be characteristic of patientsdiagnosed with epileptic psychosis.54However, incontrast t o the anecdotal reports of links betweenaggressive personality disorders and TLE 55 ,56 wefound th at a separate analysis of aggression a s a be-havioral trai t did not correlate with type of epilepsyo r medial temporal pathology. Moreover, the rela-tive independence of epilepsy and psychosis is fur-ther emphasized by our study in that among 661brain specimens from individuals with epilepsy inthe Runwell Hospital collection, only 75 patients(11%) ad a diagnosis of epilepsy and psychosis. Ofthese, we excluded two-thirds as the onset of theirseizures had occurred either in late life, after leukot-omy, following insulin therapy, or in associationwith other organic disease. This leaves the coinci-dence of epilepsy followed by psychosis at around4% in this highly selected population of mentally illindividuals. We therefore conclude th at , under mod-er n conditions of tr ea tm ent, clinical epilepsy-in-cludin g TLE-is an uncommon ante cede nt ofschizophrenia or psychosis. The mean age a t onsetof epilepsy for patients who subsequently developedan epileptic or a schizophrenic psychosis was 13 and15 years, compared with 7 years for epileptic colonypatients and 23 years for community patients. Thisfinding is in keeping with observations by Taylor57and Ounsted and Li n d~ ay ~hat epilepsy beginningin o r enduring through puberty is more likely to beassociated with subsequent psychosis.

Conclusions. The results of our neuropathologicinvestigation were unexpected yet clear-cut. Indi-viduals with psychosis in this study were character-ized by their pubertal age a t onset of seizures and apreponderance of generalized (grand mal) epilepsy.They were not characterized by degree, type, later-ality, o r bilaterality of MTS. The brains of psychoticindividuals were distinguished by larger ventriclesand more focal pathology, including periventriculargliosis. I n p atien ts with schizophrenia-like psy-chosis, the brains also contained a significant excessof punctate white-matter lesions. Our findings showth at epileptic pa tients with psychosis have more se-vere and widespread brain damage than do epilep-tic patients with no evidence of psychotic illness.The results also suggest tha t the additional pathol-ogy is unrelated t o the cerebral lesions commonlyassociated with epilepsy bu t resembles both th estructural abnormalities and the acquired pathol-ogy recently described in patients with schizophre-nia. White-matter lesions similar to those reportedhere are common in elderly patients who are notpsychotic, but such lesions were significantly lessfrequent in the similarly aged epileptic colony andepileptic psychosis groups in this study. We con-clude that psychoses associated with epilepsy areno t the result of classic epileptic pathology of the

described in patients with epilepsy since the time ofSommer18 and of Spielmeyer,19 This information,combined with th e absence of pathologic lesions localized to th e frontal or other specific areas, suggests that neither MTS nor macroscopic frontal lobepathology is critical to the development of psychosisin epilepsy. This is not so surprising, however, for inschizophrenia, despite th e presence of a small-sizedor "dysplastic" hippocampus or parahippocampalgyrus in a percentage of the patients studied, bothMTS and frontal lobe lesions are uncommon24.26.45and the cause of the lateral ventricular enlargementremains unknown. We found MTS in 40% to 50% ofall four epileptic groups; this figure comparesclosely with the findings of other epilepsy studies byF a l c o n e r ; ~ 6 Veith,47 Margerison and Corsellis,20 an dBruton.32 There are other ways in which our findings do no t support th e widely accepted belief thatTLE particul arly predisposes to schizophrenia. Partial (including temporal lobe) seizures were no morecommon in our schizophrenia-like psychosis patients than in our most "normal" group of epileptics,ie, those who lived in th e community. Furthermore,although Taylor et al 41:l an d Bruton32 found that congenital malformations, especially gangliogliomasan d hamartomas, were overrepresented in the temporal lobes removed at surgery from patients withepilepsy an d psychosis, we found no similar lesionsamong the 27 patients with psychosis (including 10with schizophrenia-like psychosis) in the presentstudy. Possible reasons for this discrepancy may bedue to selection bias; the cases of both Taylor et alan d Bruton were selected for temporal lobe surgerybecause of intractability of TLE and thus, in contrast to the earlier Slater an d Beard study, 5 did no tinclude patients who had other types of epilepsy. Aparticularly forceful case for relationship betweenTLE and psychosis was also made by Perez andTrimble.8.10 The schizophrenia-like psychoses theyreported differed greatly from those of th e chronic,hospitalized patients in ou r study. Diagnosed by th ePresent State Examination as having "nuclearschizophrenia,"8 most of their patients were outpatients who lived and often worked in th e community, many without long-term neuroleptic medication. In contrast, our patients were chronic, oftendeteriorated schizophrenics, confined to a mentalhospital and generally receiving antipsychotic aswell as anticonvulsant medication. Th e absence of asignificant increase in temporal lobe pathology inour patients appears to be powerful evidenceagainst a discrete connection between TLE, temporallobe pathology, and schizophrenia as Kraepelindefined th e disorder. Several investigators have reported evidence for a preponderance of left-sidedanatomic abnormality in schizophrenia49.51 and inthe schizophrenia-like psychoses of epilepsy.''i2,53However, no evidence of lateralization of pathologyappeared in this pathologic study of whole brains.Our findings are compatible with those of Kristensen and Sindrup,36 who compared pneumoencephalograrns from nearly 200 TLE patients, one-40 NEUROLOGY 44 January 1994

half with and one-half without psychosis, and reported diffuse ventricular enlargement without lateralization of pathology as the distinguishinganatomic feature of patients with psychosis.Aggressive, violent, an d impulsive behavior wasgenerally considered to be characteristic of patientsdiagnosed with epileptic psychosis.54 However, incontrast to th e anecdotal reports of links betweenaggressive personality disorders and TLE,55,s6 wefound that a separate analysis of aggression as a behavioral trait did no t correlate with type of epilepsyor medial temporal pathology. Moreover, th e relative independence of epilepsy an d psychosis is further emphasized by our study in that among 661brain specimens from individuals with epilepsy inth e Runwell Hospital collection, only 75 patients(11%) had a diagnosis of epilepsy and psychosis. Ofthese, we excluded two-thirds as the onset of theirseizures ha d occurred either in late life, after leukotomy, following insulin therapy, or in associationwith other organk disease. This leaves the coincidence of epilepsy followed by psychosis at around4% in this highly selected population of mentally il lindividuals. We therefore conclude that, under modern conditions of treatment, clinical epilepsy-including TLE-i s an uncommon antecedent ofschizophrenia or psychosis. The mean age at onsetof epilepsy for patients who subsequently developedan epileptic or a schizophrenic psychosis was 13 an d15 years, compared with 7 years for epileptic colonypatients and 23 years for community patients. Thisfinding is in keeping with observations by Taylor5?an d Ounsted an d Lindsay58 that epilepsy beginningin or enduring through puberty is more likely to beassociated with subsequent psychosis.

Conclusions. The results of ou r neuropathologicinvestigation were unexpected yet clear-cut. Individuals with psychosis in this study were characterized by their pubertal age at onset of seizures and apreponderance of generalized (grand mal) epilepsy.They were not characterized by degree, type, laterality, or bilaterality of MTS. The brains of psychoticindividuals were distinguished by larger ventriclesand more focal pathology, including periventriculargliosis. In patients with schizophrenia-like psychosis, the brains also contained a significant excessof punctate white-matter lesions. Our findings showthat epileptic patients with psychosis have more severe and widespread brain damage than do epilepti c patients with no evidence of psychotic illness.The results also suggest that th e additional pathology is unrelated to th e cerebral lesions commonlyassociated with epilepsy but resembles both thestructural abnormalities an d th e acquired pathology recently described in patients with schizophrenia. White-matter lesions similar to those reportedhere are common in elderly patients who ar e no tpsychotic, but such lesions were significantly lessfrequent in th e similarly aged epileptic colony andepileptic psychosis groups in this study. We conclude that psychoses associated with epilepsy ar enot th e result of classic epileptic pathology of th e

-

8/3/2019 Psychosis Schz Neurology 1994

8/8

temporal lobe o r of TLE but may arise as a result ofother degenerative o r regenerative changes in thebrain. The nature of this pathologic response maybe found using neurotransmitter or neuroreceptortechniques beyond those of classic neu ro pa th ~lo gy .~ ~Note. Readers can obtain 8 pages of supplementary material from theNational Auxiliary Publications Service, do Microfiche Publications, POBox 3513, Grand Central Station, Ne w York, NY 10163-3513.Requestdocument no. 05035. Remit with your order (not under separate cover), nU S funds only, $7.75 fo r photocopies or $4.00 for microfiche. Outside theUnited States and Canada,add postage of $4.50for the first 20 pages and$1.00 for each 10 pages of material thereafter, or $1.75 for the first mi-crofiche and $.50 for each fiche thereafter. There is a $15.00 invoicingcharge on all orders filled before payment.

References1.2.

3.4.5.6.7.

8.

9.

10.11.12.13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

Zielinski J J . Epilepsy and mortality rat e an d cause of death.Epilepsia 1974;15:191-201.Toone BK, Garralda ME, Ron MA. The psychoses of epilepsyand the functional psychoses: a clinical and phenomenologi-cal comparison. Br J Psychiatry 1982;141:256-261.Gibbs EL, Gibbs FA, Fuster B. Psychomotor epilepsy. ArchNeurol Psychiat ry 1948;60:331-339.Hill D. Psychiatric disorders of epilepsy. Medical PressSlater E, Beard AW. The schizophrenia-like psychoses ofepilepsy. Br J Psychiatry 1963;109:95-150.Flor-Henry P. Psychosis and temporal lobe epilepsy: a con-trolled investigation. Epilepsia 1969;10:363-395.Taylor DC. Factors influencing t he occurrence of schizophre-nia-like psychosis in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy.Psychol Med 1975;5:249-254.Perez NM, Trimble MR. Epileptic psychosis-diagnosticcomparison with process schizophrenia. Br J PsychiatryShukla GD, Srivastava ON, Katiyar BC, Joshi V, MohanPK. Psychiatric manifestations in temporal lobe epilepsy: acontrolled study. Br J Psychiatry 1979;135:411-417.Trimble MR. Interi ctal psychoses of epilepsy. Acta PsychiatrScand [Suppll 1984;313:9-20.Bartlet JEA. Chronic psychosis following epilepsy. Am JPsychiatry 1957;114:338-343.Ste vens JR. Psychiat ric implications of psychomotorepilepsy. Arch Gen Psychia try 1966;14:461-471.Betts TA. A follow-up study of a cohort of patients withepilepsy admitted t o psychiatric care in an English city. In:Harris P, Mawdsley C, eds. Epilepsy: proceedings of theHans Berger Centenary Symposium. Edinburgh, UK:Churchill Livingstone, 1974:326-336.Parnas J , Korsgaard S, Krautwald 0, Stigaard Jensen P.Chronic psychosis in epilepsy: a clinical investigation of 29patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1982;66:282-293.Hermann BP, Whitman S. Behavioral and personality corre-late s of epilepsy: a review, methodological crit ique, and con-ceptual model. Psychol Bull 1984;95:451-497.Rodin EA, Katz M, Lennox K. Differences between patientswith temporal lobe seizures and those with other forms ofepileptic attacks . Epilepsia 1976;17:313-320.Standage KF, Fenton GW. Psychiatric symptom profiles ofpatients with epilepsy: a controlled investigation. PsycholMed 1975:5:152-160.

1953;229:473-475.

1980;137:245-249.

18. Sommer W . Erkrankung des Ammonshornes als aetolog-isches Moment der Epilepsie. Arch Psychiatr Nervenkr19. Spielmeyer W. Die pathogenese des epileptischen Krampfes.Histopathologischer Teil. Z Dtsch Ges Neurol Psychiatr20. Margerison JH, Corsellis JAN. Epilepsy a nd th e temporallobes. Brain 1966;89:499-530.21. Dam AM. Hippocampal neuron loss i n epilepsy and af ter ex-perimental seizures. Acta Neurol Scand 1982;66:601-642.22. Meldrum BS, Bruton CJ. Epilepsy. In: Adams JH, DuchenLW, eds. Greenfields neuropathology. 5th ed. London: Ed-

1880;10:631-675.

1927;109:501-520.

ward Arnold, 1992:1246-1283.23. Johnstone EC, Crow TJ, Frith CD, Husband J, Kreel L.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.29.30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.45.

46.

Cerebral ventricular size and cognitive impairment inchronic schizophrenia. Lancet 1976;2:924-926.Bogerts B, Meertz E, Schonfeldt-Bausch R. Basal gangliaand limbic system pathology in schizophrenia: a morpho-metric study of brain volume and shrinkage. Arch Gen Psy-chiatry 1985;42:784-791.Brown R, Colter N, Corsellis JAN, Crow TJ , Fri th CD. Post-mortem evidence of structural brain changes in schizophre-nia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986;43:36-42.Bruton CJ, Crow TJ, Frith CD, Johnstone EC, Owens DGC,Roberts GW. Schizophrenia and the brain: a prospective clin-ico-neuropathologica1study. Psychol Med 1990;20:285-304.Nieto D, Escobar A. Major psychoses. In: Minckler J , ed.Pathology of the nervous system, vol3. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1972:2654-2665.Steven s JR. Neuropathology of schizophrenia. Arch GenPsychiatry 1982;39:1131-1139.Falkai P, Bogerts B. Cell loss in hippocampus of schizo-phrenics. Eu r Arch Psychiatry Neurol Sci 1986;236:154-161.Pakkenberg B. Pronounced reduction of total neuron num-ber in mediodorsal thalamic nucleus and nucleus accumbensin schizophrenics. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990;47:1023-1028.Taylor DC. Mental state and temporal lobe epilepsy: a cor-relative account of 100 patients treated sur aca lly . EpilepsiaBruton CJ. The neuropathology of temporal lobe epilepsy.Maudsley Monograph No. 31. Oxford, U K Oxford UniversityPress, 1988.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statisticalmanual of mental disorders. 3rd ed, rev. Washington, DC:APA Press, 1987.Falconer MA, Serafet inides EA, Corsellis JAN. Etiology andpathogenesis of temporal lobe epilepsy. Arch Neurol 1964;Taylor DC. Epileptic experience, schizophrenia and th e tem-poral lobe. In: Blumerd, Levin K, eds. Psychiatric complica-tions in the epilepsy: current research and treatment.McLean Hosp J 1977;suppl:22-39.Kristensen 0, Sindrup EH. Psychomotor epilepsy and psy-chosis. I. Physical aspects. Acta Neurol Scand 1978;57:361-379.Stevens JR. Epilepsy and psychosis: neuropathologic studiesof six cases. In: Bolwig T, Trimble M, eds. Aspects of epilepsyand psychiatry. London: John Wiley & Sons, 1986:117-146.Bruetsch WL. Specific structural neuropathology of the cen-tral nervous system (rheuma tic, demyelinating, vasofunc-tional etc.) in schizophrenia. In: First Intern ational Con-gress of Neuropathology. Turin, Italy: Rosenberg & Sellier,1952:487-499.van der Horst L. Histopathology of clinically diagnosedschizophrenic psychoses or schizophrenia-l ike psychoses ofunknown origin. In: Fi rst Interna tional Congress of Neu-ropathology. Turin, Italy: Rosenberg & Sellier, 1952:501-513.Bini L, Marchiafava G. Schizophrenia. In: First Interna-tional Congress of Neuropathology. Turin, Italy: Rosenberg& Sellier, 1952:670-672.Corsellis JAN. Psychoses of obscure pathology. In: Black-wood W, Corsellis JAN, eds. Greenfields neuropathology.3rd ed. London: Edward Arnold, 1976:903-915.Hyde TM, Ziegler JC, Weinberger DR. Psychiatric distur-bances in metachromatic leukodystrophy. Arch NeurolDavison K, Bagley CR. Schizophrenia-like psychoses associ-ated with organic disorders of the central nervous system: areview of the literature. In: Herrington RN, ed. Currentproblems in neuropsychiatry, schizophrenia, epilepsy, thetemporal lobe. Kent, U K Headley Brothers, 1969:113-184.Lohr JB, Flynn K. Smoking and schizophrenia. SchizophrRes 1992;8:93-102.Jakob H, Beckmann H. Prenatal developmental distur-bances in the limbic allocortex in schizophrenics. J NeuralTransm 1986;65:303-326.Falconer MA. Mesial tempora l (Ammons horn) sclerosis as acommon cause of epilepsy: aetiology, treatment, and preven-tion. Lancet 1974;2:767-770.

1972;13:727-765.

10:233-248.

1992;49:401-406.

January 1994NEUROLOGY 44 41

temporal lobe or of TLE bu t may arise as a result ofother degenerative or regenerative changes in thebrain. The nature of this pathologic response maybe found using neurotransmitter or neuroreceptortechniques beyond those of classic neuropathology.59Note. Readers can obtain 8 pages of supplementary material from theNational Auxiliary Publications Service, c/o Microfiche Publications, POBox 3513, Grand Central Station, New York, NY 10163-3513. Requestdocument no. 05035. Remit with your order (not under separate cover), inUS funds only, $7.75 for photocopies or $4.00 for microfiche. Outside th eUnited States and Canada, add postage of $4.50 for the first 20 pages and$1.00 for each 10 pages of material thereafter, or $1.75 for the first microfiche and $.50 for each fiche thereafter. There is a $15.00 invoicingcharge on all ord ers filled before payment.

References1. Zielinski JJ . Epilepsy and mortality rate an d cause of death.

Epilepsia 1974;15:191-201.2. Toone BK, Garralda ME, Ron MA. The psychoses of epilepsyand the functional psychoses: a clinical an d phenomenological comparison. Br J Psychiatry 1982;141:256-261.3. Gibbs EL, Gibbs FA, Fuster B. Psychomotor epilepsy. ArchNeurol Psychiatry 1948;60:331-339.4. Hill D. Psychiatric disorders of epilepsy. Medical Press1953;229:473-475.5. Slater E, Beard AW. The schizophrenia-like psychoses ofepilepsy. Br J Psychiatry 1963;109:95-150.6. Flor-Henry P. Psychosis and temporal lobe epilepsy: a controlled investigation. Epilepsia 1969;10:363-395.7. Taylor DC. Factors influencing the occurrence of schizophrenia-like psychosis in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy.Psychol Med 1975;5:249-254.8. Perez NM, Trimble MR. Epileptic psychosis-diagnosticcomparison with process schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry1980;137:245-249.9. Shukla GD, Srivastava ON, Katiyar BC, Joshi V, MohanPK. Psychiatric manifestations in temporal lobe epilepsy: acontrolled study. Br J Psychiatry 1979;135:411-417.10. Trimble MR. Interictal psychoses of epilepsy. Acta PsychiatrScand [Suppl] 1984;313:9-20.11. Bartlet JEA. Chronic psychosis following epilepsy. Am JPsychiatry 1957;114:338-343.12. Stevens JR. Psychiatric implications of psychomotorepilepsy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1966;14:461-471.13. Betts TA. A follow-up study of a cohort of patients withepilepsy admitted to psychiatric care in an English city. In:Harris P, Mawdsley C, eds. Epilepsy: proceedings of th eHans Berger Centenary Symposium. Edinburgh, UK:Churchi ll Livingstone, 1974:326-336.14. Parnas J, Korsgaard S, Krautwald 0, Stigaard Jensen P.Chronic psychosis in epilepsy: a clinical investigation of 29patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1982;66:282-293.15. Hermann BP, Whitman S. Behavioral an d personality correlates of epilepsy: a review, methodological critique, and conceptual model. Psychol Bull 1984;95:451-497.16. Rodin EA, Katz M, Lennox K. Differences between patientswith temporal lobe seizures an d those with other forms ofepileptic attacks. Epilepsia 1976;17:313-320.17. Standage KF, Fenton GW. Psychiatric symptom profiles ofpatients with epilepsy: a controlled investigation. PsycholMed 1975;5:152-160.18. Sommer W. Erkrankung des Ammonshornes als aetologisches Moment del' Epilepsie. Arch Psychiatr Nervenkr1880;10:631-675.19. Spielmeyer W. Die pathogenese des epileptischen Krampfes.Histopathologischer Teil. Z Dtsch Ges Neurol Psychiatr1927;109:501-520.20. Margerison JH , Corsellis JAN. Epilepsy and the temporallobes. Brain 1966;89:499-530.21. Dam AM. Hippocampal neuron loss in epilepsy and after experimental seizures. Acta Neurol Scand 1982;66:601-642.22. Meldrum BS, Bruton CJ. Epilepsy. In: Adains JH, DuchenLW, eds. Greenfield's neuropathology. 5th ed. London: Ed-

ward Arnold, 1992:1246-1283.23. Johnstone EC, Crow TJ , Frith CD, Husband J, Kreel L.Cerebral ventricular size an d cognitive impairment inchronic schizophrenia. Lancet 1976;2:924-926.24. Bogerts B, Meertz E, Schonfeldt-Bausch R. Basal gangliaand limbic system pathology in schizophrenia: a morphometric study of brain volume an d shrinkage. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1985;42:784-791.25. Brown R, Colter N, Corsellis JAN, Crow TJ , Frith CD. Postmortem evidence of structural brain changes in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986;43:36-42.26. Bruton CJ, Crow TJ , Frith CD, Johnstone EC, Owens DGC,Roberts GW. Schizophrenia an d the brain: a prospective clinico-neuropathological st udy. Psychol Med 1990;20:285-304.27. Nieto D, Escobar A. Major psychoses. In: Minckler J, ed.Pathology of the nervous system, vol 3. New York: McGrawHill, 1972:2654-2665.28. Stevens JR. Neuropathology of schizophrenia. Arch GenPsychiatry 1982;39:1131-1139.29. Falkai P, Bogerts B. Cell loss in hippocampus of schizophrenics. Eur Arch Psychiatry Neurol Sci 1986;236:154-161.30. Pakkenberg B. Pronounced reduction of total neuron numbe r in mediodorsal thalamic nucleus an d nucleus accumbensin schizophrenics. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990;47: 1023-1028.31. Taylor DC. Mental state an d temporal lobe epilepsy: a correlative account of 100 patients treated surgically. Epilepsia1972;13:727 -765.32. Bruton CJ. The neuropathology of temporal lobe epilepsy.Maudsley Monogra ph No. 31. Oxford, UK: Oxford UniversityPress, 1988.33. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic an d statisticalmanual of mental disorders. 3r d ed, rev. Washington, DC:APA Press, 1987.34. Falconer MA, Serafetinides EA, Corsellis JAN. Etiology andpathogenesis of temporal lobe epilepsy. Arch Neurol 1964;10:233-248.35. Taylor DC. Epileptic experience, schizophrenia and the temporal lobe. In: Blumerd, Levin K, eds. Psychiatric complications in th e epilepsy: current research and treatment.McLean Hosp J 1977;suppl:22-39.36. Kristensen 0, Sindrup EH. Psychomotor epilepsy an d psychosis. 1. Physical aspec ts. Acta Neurol Scand 1978;57:361-379.37. Stevens JR. Epilepsy and psychosis: neuropathologic studiesof six cases. In: Bolwig T, Trimble M, eds. Aspects of epilepsyan d psychiatry. London: John Wiley & Sons, 1986:117-146.38. Bruetsch WL. Specific structural neuropathology of the central nervous system (rheumatic, demyelinating, vasofunctional etc.) in schizophrenia. In: First International Congress of Neuropathology. Turin, Italy: Rosenberg & Sellier,1952:487 -499.39. van der Horst L. Histopathology of clinically diagnosedschizophrenic psychoses or schizophrenia-like psychoses ofunknown origin. In: First International Congress of Neuropathology. Turin, Italy: Rosenberg & Sellier, 1952:501-513.

40. Bini L, Marchiafava G. Schizophrenia. In: First International Congress of Neuropathology. Turin, Italy: Rosenberg& Sellier, 1952:670-672.41. Corsellis JAN. Psyc hoses of obscure pathology. In: Blackwood W, CorseIlis JAN, eds. Greenfield's neuropathology.3r d ed. London: Edward Arnold, 1976:903-915.42. Hyde TM, Ziegler JC, Weinberger DR. Psychiatric disturbances in metachromatic leukodystrophy. Arch Neurol1992;49:401-406.

43. Davison K, Bagley CR. Schizophrenia-like psychoses associated with organic disorders of the central nervous system: areview of the literature. In: Herrington RN, ed. Currentproblems in neuropsychiatry, schizophrenia, epilepsy, thetemporal lobe. Ke nt, UK: Headley Brothers, 1969:113-184.44. Lohr JB, Flynn K. Smoking and schizophrenia. SchizophrRes 1992;8:93-102.45. Jakob H, Beckmann H. Prenatal developmental disturbances in the limbic allocortex in schizophrenics. J NeuralTransm 1986;65:303-326.46. Falconer MA. Mesial temporal (Ammon's horn) sclerosis as acommon cause of epilepsy: aetiology, treatment, and prevention. Lancet 1974;2:767-770.

January 1994 NEUROLOGY 44 41