-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

1/58

1Promoting the conservation and use of underutilized and neglected crops. 8.

C h a y o t eC h a y o t e

Promoting the conservation and use of underutilized and neglected crops. 8.

IPGRII

nt

ernati

onalPla

ntGeneticResou

rces

Institute

IPGRI

Rafael Lira Saade

Sechium edule (Jacq.) Sw.

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

2/58

2 Chayote. Sechium edule(Jacq.) Sw.

The International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI) is an autonomous inter-

national scientific organization operating under the aegis of the Consultative Group

on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). The international statu s of IPGRI is

conferred under an Establishment Agreement which, by December 1995, had beensigned by the Governments of Australia, Belgium, Benin, Bolivia, Burkina Faso,

Cameroon, China, Chile, Congo, Costa Rica, Cte dIvoire, Cyprus, Czech Republic,

Denm ark, Ecuador, Egypt, Greece, Guinea, Hungary, Ind ia, Iran, Israel, Italy, Jordan,

Kenya, Mauritania, Morocco, Pakistan, Panama, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Romania,

Russia, Senegal, Slovak Republic, Sudan, Switzerland , Syria, Tunisia, Turkey, Ukraine

and Ugand a. IPGRIs mandate is to advance the conservation and use of plant genetic

resources for the benefit of present and future generations. IPGRI works in partner-

ship with other organizations, undertaking research, training and the provision of

scientific and technical advice and information, and has a particularly strongprogram me link w ith the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Financial support for the agreed research agenda of IPGRI is provided by the Govern-

ments of Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, China, Denmark, France, Germany,

India, Italy, Japan, the Republic of Korea, Mexico, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain,

Sweden, Switzerland, the UK and the USA, and by the Asian Development Bank,

IDRC, UNDP and the World Bank.

The Institute of Plant Genetics and Crop Plant Research (IPK) is operated as an

indep endent foun dation un der pu blic law. The foun dation statute assigns to IPK

the task of conducting basic research in the area of plant genetics and research oncultivated p lants.

The geographical designations employed and the presentation of material in

this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part

of IPGRI, the CGIAR or IPK concerning the legal statu s of any country, terr itory, city

or area or its authorities, or concerning th e delimitation of its frontiers or bou nd -

aries. Similarly, the views expressed are those of the au thors and do not necessarily

reflect the views of these participating organizations.

Citation:

Rafael Lira Saad e. 1996. Chayote. Sechium edule (Jacq.) Sw. Prom oting the conserva-tion and use of und erutilized and neglected crops. 8. Institute of Plant Genetics and

Crop Plant Research, Gatersleben/ International Plant Genetic Resources Institute,

Rome, Italy.

ISBN 92-9043-298-5

IPGRI IPK

Via delle Sette Chiese 142 Corrensstrasse 3

00145 Rome 06466 Gatersleben

Italy Germany

Internat ional Plant Genetic Resources Institu te, 1996

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

3/58

3Promoting the conservation and use of underutilized and neglected crops. 8.

ContentsForeword 4

Acknowledgements 6

1 Introduction 72 Taxonomy and names of the species 8

2.1 History and taxonomy ofSechium edule 8

2.2 Scientific name and synonymy 10

2.3 Common names 11

3 Brief description of the crop 15

3.1 Botanical description 15

3.2 Flower biology and pollinators 17

4 The origins of chayote 19

4.1 Sechium edule wild types 234.2 Sechium chinantlense Lira & Chiang 24

4.3 Sechium compositum (J.D. Smith) C.Jeffrey 25

4.4 Sechium hintonii (P.G. Wilson) C.Jeffrey 26

5 Uses and properties 28

6 Diversity and genetic resources 30

7 Breeding 37

8 Areas of production and consumption 38

9 Ecology 41

10 Agronomy 4211 Pests and diseases 46

12 Limitations of the crop, research needs and prospects 49

13 References 51

Appendix I. Research contacts, centres of crop research, breeding

and plant genetic resources of chayote 57

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

4/58

4 Chayote. Sechium edule(Jacq.) Sw.

ForewordHumanity relies on a diverse range of cultivated species; at least 6000 such species

are used for a variety of pu rposes. It is often stated tha t only a few stap le crops

prod uce the majority of the food su pp ly. This might be correct but the imp ortantcontribution of man y minor species shou ld not be un derestimated. Agricultural

research has traditionally focused on these staples, while relatively little attention

has been given to m inor (or un derutilized or neglected) crops, par ticularly by scien-

tists in developed countries. Such crops have, therefore, genera lly failed to attract

significant research fund ing. Unlike most staples, many of these neglected species

are adapted to various marginal growing conditions such as those of the Andean

and Himalayan highlands, arid areas, salt-affected soils, etc. Furtherm ore, man y

crops considered neglected at a global level are stap les at a national or regional level

(e.g. tef, fonio, And ean roots an d tubers etc.), contribu te consid erably to food su p-ply in certain periods (e.g. ind igenous fruit trees) or are imp ortant for a nutr ition-

ally well-balanced diet (e.g. ind igenou s vegetables). The limited inform ation avail-

able on m any imp ortant and frequently basic aspects of neglected an d un derutilized

crops hind ers their developm ent and their sustainable conservation. One major

factor ham pering th is development is that the information available on germplasm

is scattered and not read ily accessible, i.e. only found in grey literature or w ritten

in little-known languages. Moreover, existing know ledge on the genetic potential

of neglected crops is limited . This has resulted , frequently, in uncoordinated re-

search efforts for most neglected crops, as well as in inefficient approaches to theconservation of these genetic resources.

This series of monographs intends to draw attention to a number of species

which have been neglected in a varying degree by researchers or have been

un derutilized economically. It is hoped th at the information compiled w ill contrib-

ute to: (1) iden tifying constra ints in and p ossible solutions to the use of the crops, (2)

identifying possible un tapp ed genetic d iversity for breeding and crop imp rovement

program mes and (3) detecting existing gaps in available conservation and use ap -

proaches. This series intend s to contribute to imp rovement of the potential value of

these crops throu gh increased use of the available genetic d iversity. In add ition, it is

hoped that the monographs in the series will form a valuable reference source for all

those scientists involved in conservation, research, improvement an d prom otion of

these crops.

This series is the result of a joint p roject between the International Plant Genetic

Resources Institute (IPGRI) and the Institu te of Plant Genetics and Crop Plan t Re-

search (IPK). Finan cial support provided by the Federal Ministry of Econom ic Co-

operation and Development (BMZ) of Germany through the German Agency for

Technical Cooperation (GTZ) is du ly acknowledged .

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

5/58

5Promoting the conservation and use of underutilized and neglected crops. 8.

Series editors:

Dr Joachim Heller

Institute of Plant Genetics and Crop Plant Research (IPK)

Dr Jan Engels

International Plan t Genetic Resources Institu te (IPGRI)

Prof. Dr Karl Hamm er

Institute of Plant Genetics and Crop Plant Research (IPK)

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

6/58

6 Chayote. Sechium edule(Jacq.) Sw.

AcknowledgementsFirst, I would like to express my gra titud e to Dr Joachim H eller (IPGRI), for having

invited me to p repare this pap er, and for his helpful suggestions and recomm enda-

tions for improving it. I am equally grateful to Jan Engels, Charles Jeffrey andAbdenago Brenes, for their valuable comm ents on the first versions of the pap er, the

International Board for Plant Genetic Resources Institute and the Institute of Biol-

ogy of the National Auton omou s University of Mexico (UNAM) for their suppor t

from 1990 to 1992. During this period, I carried out the project Taxonom ic and

Ecogeographic Studies of Cucurbitaceae in Latin America. Much of the informa-

tion presented here is based on that p roject. Special thanks are due to the Interna-

tional Plant Genetic Resources Institute, the Centre of Information for Science and

the Humanities of the UNAM and, above all, to Abdenago Brenes (Agricultural

Engineer, at the National Hered ia University, Costa Rica) for his timely and efficienthelp in obtaining m any of the bibliographical references and data which h ave been

analyzed in th is work. Gratefu l thanks is also extended to the Instituto d e Ecologa,

Xalapa, Veracruz for perm ission to reprod uce Figure 3.

Rafael Lira Saade

Mxico, D.F., Septem ber 1996

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

7/58

7Promoting the conservation and use of underutilized and neglected crops. 8.

1 Introduction

Chayote is the Nah uatl nam e used in many p arts of Latin America for the cu ltivatedspecies Sechium edule (Jacq.) Swartz. Its variable fruits, as well as its roots, have been

important elements in the d iet of the people living in these and oth er areas of the

world. However, as is the case with man y other crops, in spite of the fact that chay-

ote is widespread and is an importan t export crop for some Latin American coun-

tries, mu ch still needs to be learned abou t it. More information is needed on the

biological characteristics of this crop, on how to imp rove it, and how it is related to

wild species of the genus, as well as how to conserve its genetic resources.

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

8/58

8 Chayote. Sechium edule(Jacq.) Sw.

2 Taxonomy and names of the species

2.1 History and taxonomy of Sechium edule

The most recent classification of the Cucurbitaceae (Jeffrey 1990) places the genusSechium, to which chayote belongs, in the subtribe Sicyinae of the tribe Sicyeae, along

with the genera Microsechium, Parasicyos, Sechiopsis, Sicyosperma an d Sicyos. The

mem bers of this subtribe are characterized by h aving sp iny pollen, a single pendu-

lous ovule and single-seeded fruits. When the first monograph on the Cucurbitaceae

was published (Cogniaux 1881), Sechium was considered m onospecific and only to

contain S.edule. This species was originally d iscovered by Browne (1756) in Jamaica,

and in 1763 it was classified simultaneou sly as Sicyosedulis by Jacquin and as Chocho

edulis by Adanson.

Later, Jacqu in (1788) changed it to C.edulis and placed it in his genu s Chayota. Afew years later, Swartz (1800) became the first to include this species in Sechium,

when he p roposed the combination by which it is still know n, S.edule (Jacq.) Swartz.

During the last century, another three species were described as belonging to

Sechium. These d id not always correspond to the taxonom ic limits of this genus,

however, and they are now placed in the synonymy of other genera, or in that of

Sechium itself.

Almost a century after the pu blication of Cogniau xs monograp h, Jeffrey (1978)

widened the taxonomic limits ofSechium by including several Mexican an d Central

American taxa w hich other auth ors had described in, or later transferred to, generasuch as Cyclanthera, Ahzolia, Frantzia, M icrosechium an d Polakowskia (Cogniaux 1891;

Donnell-Smith 1903; Pittier 1910; Standley and Steyermark 1944; Wilson 1958;

Wunderlin 1976). All of these taxa share the p resence of nectaries at the base of the

flower receptacle of both sexes, a complex and variable androecium structure, and

prod uce med ium to large fleshy-fibrous fruit.

According to this new generic circumscription, Sechium includ ed seven species

arranged in two sections, Sechium an d Frantzia, which differ in the m orph ology of

the floral nectaries and the arrangement of the stamens. Thus, Sechium included

species with naked floral nectaries visible from above, partially or totally joined

filaments and free anthers. This section includ ed S.edule (Jacq.) Swartz, S.hintonii

(P.G. Wilson) C.Jeffrey, and S.compositum (J. D. Smith) C.Jeffrey, as w ell as S.tacaco

(Pittier) C.Jeffrey and S.talamancense (Wunderlin) C.Jeffrey. Frantzia, on the other

hand , was originally p roposed by Wunderlin (1976), for the genu s of the same nam e,

and placed in the Sechium synonymy by Jeffrey (1978). It included tw o species:

S.pittieri (Cogn.) C.Jeffrey and S.villosum (Wunderlin) C.Jeffrey, wh ose floral nec-

taries are covered by a cush ion- or um brella-shap ed spongy structure, whose fila-

ments m erge to form a column and whose anthers merge together to form a globose

structure.

A year before the publication of Jeffreys w ork, Wun derlin (1977) described anadditional Frantzia species from Panam a (F.panamensis Wunderlin), which he placed

in the typ ical section of this genu s. Soon afterwards, L.D. Gmez (Gmez and

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

9/58

9Promoting the conservation and use of underutilized and neglected crops. 8.

Gmez 1983), ignoring Jeffreys (1978) generic proposal, described a new species

from Costa Rica un der the genus Frantzia, using the binominal Frantzia venosa L.D.

Gmez. Apparently he failed to notice that the floral nectaries of his new sp ecies

were covered w ith the p illow-, cush ion- or umbrella-shaped sp ongy structure w hichcharacterizes species in Wunderlins (1976) Frantzia section, and he w rongly p laced

it in the section Polakowskiasensu Wunderlin (1976). Since neither of these two spe-

cies was reclassified in Sechium, either by C.Jeffrey or by any other author in the

1980s, the generic limits of this genus became vague once again.

Although Jeffreys p roposed taxonomic broadening ofSechium (1978) was not

wid ely acclaimed , there is little doubt that h is work aw akened new interest in the

genu s. As a resu lt of Jeffreys proposal, the relatives ofSechium edule were described

formally for the first time in the literature, although other authors had already sug-

gested the closeness of many of them to this species (see Standley and Steyermark1944 for Ahzolia composita=Sechium compositum). And the widening of the limits of

the genu s, to include another cultivated sp ecies, S.tacaco (Pittier) C.Jeffrey, helped

underline the importance of studying Sechium, not only from a strictly taxonomic

point of view, but also in the general context of plant genetic resources conservation

and u se.

Mainly as a result of the above, there was an increase in botanical exploration,

aimed at finding a more representative range of species in the genus, as well as

var iations of its cultivated species. At the beginning of the 1980s, for example, three

wild Sechium populations w ere discovered in the State of Veracruz (Cruz-Len 1985-86). This was und oubted ly a major step forward in the search for knowledge about

the relationship between w ild an d cultivated species in the genu s. After several

years stud y of these populations, they were d efined as wild types ofSechium edule

(Jacq.) Swartz, bu t w ere not placed in any specific taxonomic category (Cruz-Len

1985-86; Cru z-Len and Qu erol 1985).

Dur ing the same p eriod, Newstrom (1985, 1986) reported find ing several pop u-

lations in Oaxaca that were similar to those of Veracruz, and began a series of

stud ies,aimed at d efining the origin and evolution ofSechium edule. In order to do

this, she also studied the populations of some of the species transferred by Jeffrey

(1978) to the Sechium genus, as well as those of a wild species from the State of

Veracruz, recently recognized by N ee (1993) simp ly as Frantzia sp .

Newstroms work also included a new taxonomic delimitation ofSechium, in

which the genu s wou ld be reduced to only three species: S.edule (Jacq.) Swartz (rep-

resented by wild and cultivated types), S.compositum (J.D. Smith), C.Jeffrey and

S.hintonii (P.G. Wilson ) C.Jeffrey. Accord ingly, Frantzia and Polakowskia would be

reinstated as independ ent genera, thereby also discarding the proposal mad e years

before by Wund erlin (1976) to join them together. In a later w ork, how ever,

Newstrom (1990) suggested that Sechium, Polakowskia an d Frantzia could be consid-

ered as sections ofSechium, althou gh, as w ith the above case, she never formallymad e such a prop osal. Table 1 comp ares Jeffreys (1978) and N ewstrom s (1986)

taxonom ic classification proposals for Sechium.

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

10/58

10 Chayote. Sechium edule(Jacq.) Sw.

During the 1990s, the disagreement among botanists about the taxonomic limits of

Sechium gave rise to a series of studies aimed at clarifying the problem (Lira and Soto

1991; Alvarado et al. 1992; Lira and Chiang 1992; Mercado et al. 1993; Lira et al. 1994;

Mercado and Lira 1994; Lira 1995a, 1995b). The results of these studies have shown that

Sechium is a well-defined genu s composed of 11 species (Table 2). Of these, nine are wild

species distributed throughou t central and southern Mexico, up to Panama (Figs.1 and

2). Of the two remaining species, S.tacaco is only cultivated in Costa Rica, and the other,

S.edule, as mentioned above, is widely cultivated throughout the Americas and other

regions of the world, with wild popu lations in southern Mexico.

2.2 Scientific name and synonymyThe correct scientific name for chayote is Sechium edule (Jacq.) Swartz, which, as

d iscussed above, was formally published in 1800, and is based on Sicyos edulis Jacq.

Jeffrey (1978)

Sechium sensu lato

Section Sechium

S. compositum(J.D. Smith) C. Jeffrey

S. edule(Jacq.) Swartz

S. hintonii(P.G. Wilson) C. Jeffrey

S. tacaco(Pittier) C. Jeffrey

S. talamancense(Wunderlin) C. Jeffrey

SectionFrantzia

S. pittieri(Cogn.) C. Jeffrey

S. villosum(Wunderlin) C. Jeffrey

Newstrom (1986)

Sechium sensu stricto

No sections

S. compositum(J.D. Smith) C. Jeffrey

S. edule(Jacq.) Swartz (wild and cultivated)

S. hintonii(P.G. Wilson) C. Jeffrey

Polakowskia sensu lato

P. tacacoPittier

P. talamancense(Wunderlin) NewstromFrantzia sensu stricto

F. pittieri(Cogn.) Pittier

F. panamenseWunderlin

F. venosaL.D. Gmez

F. villosaWunderlin

Table 1. Proposed taxonomic classifications of Sechiumand related genera

Table 2. Taxonomic classification of the genus SechiumP.Br. adopted in this book

Section Sechium

S. compositum(J.D. Smith) C. Jeffrey

S. chinantlenseLira & Chiang

S. edule(Jacq.) Swartz (wild and cultivated)

S. hintonii(P.G. Wilson) C. Jeffrey

S. tacaco(Pittier) C. Jeffrey

S. talamancense(Wunderlin) C. Jeffrey

Section Frantzia

S. panamense(Wunderlin) Lira & Chiang

S. pittieri(Cogn.) C. Jeffrey

S. venosum(L.D. Gmez) Lira & Chiang

S. villosum(Wunderlin) C. Jeffrey

Sechiumsp.

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

11/58

11Promoting the conservation and use of underutilized and neglected crops. 8.

Fig. 1. Distribution of the wild species of Sechiumin Mexico and northernCentral America. Question mark indicates possible S. hintoniipopulations in Jalisco.

The following are accepted synon yms for this species: Chayota edulis Jacq., Sel. Stirp .

Am er. tab. 245. 1780. Sechium americanum Poir., Lam. Encyc. Mth . Bot. 7: 50. 1806.

Cucumis acutangulus Descourt., Fl. Md. Antilles 5: 94. 1827. Non L., 1753. Sicyos

laciniatus Descourt., Fl. Md. Antilles 5: 103. 1827, non L., 1753. Sechium cayota

Hemsley, Biol. Cen tr. Am., Bot. 1: 491. 1880.

2.3 Common names

Because chayote is so widespread th roughout m any regions of the world, and is so

well know n as a useful p lant, it has come to be known by a w ide variety of nam es in

d ifferent languages. Newstrom (1986, 1991) made an excellent compilation of these,

in addition to analyzing their geographical distribution in search of patterns that

might suggest the centre of origin of this crop . More recently, additional names

have been collected by Lira (1995a). Althou gh all the above auth ors agree that the

most widely accepted term is chayote, alternative names are given to this crop

wherever it is cultivated.

In Mexico, for example, where numerous ethnic groups live in different states,

chayote is also know n by a vast variety of other names includ ing: apu po, apop u

(Michocan; Tarasco); niktin (Oaxaca; Trique); naa (Oaxaca; Mixteco); it-tse,

jit-jiap, yap e (Oaxaca; dialectal var iations of Zapoteco found in Ixtln, Tlacolulaand the Isthmus of Tehuantepec); aj-sh (Oaxaca; Mixe); rign, n (Oaxaca;

Chinan teco); mishi, cal-mishi (Oaxaca; Chontal); tzihu, tzihub (San Luis Potos;

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

12/58

12 Chayote. Sechium edule(Jacq.) Sw.

Fig. 2. Distribution of the wild species ofSechiumin Central and southern Central America.

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

13/58

13Promoting the conservation and use of underutilized and neglected crops. 8.

Huasteco); m-u (State of Mexico; Mazahua); sham, xam (State of Mexico

and Hidalgo; Mazahu a); chayoj, chayojtli (Puebla and Morelos; terms obviously

derived from the original Nahu atl nam e); macltucn, multucn, hu isquilitl,

The wild varieties are known in Veracruz as chayotes de monte and erizos demonte, and in Oaxaca as n and rign-cu, both terms of Chinanteco origin.In

Central Am erica, S.edule is known by several other names, as well as chayote. In most

of Guatemala and El Salvador, it goes by names such as gisquil, bisquil, hu isquil,

chuma, chima, chimaa, hu isayote, gisayote and perulero. In the Alta Verap az

department of Guatemala, it is known as rasi cim. In Honduras, although it is known

as hu isquil, it is also called ame, patast and patastilla, while in Nicaragua it is

known as chaya. In Costa Rica, its nam es include ps, pog-pog-iku, seuak, sur

and tsua-u, all of which app ear to derive from local ind igenous languages.

In other regions of the American continent, the names given to this crop, aspointed out by N ewstrom (1991), reflect the linguistic influence of colonialization.

Thus, names very similar to and apparently derived from chayote or chuma are

present in som e Latin Am erican countr ies. Examples of these are tayote, tayn,

chocho and chiote in Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic and Jamaica;

cidrayota and chayota in Colom bia; gayota in Peru; chayoto in Venezuela; cho

cho, xuxu or chuchu in Brazil and several Car ibbean countries; and cayota in

Argentina. In other instances, the nam es appear to derive from French. In Haiti and

the American state of Louisiana, the term christophine is used , while in Bermuda,

French Guyan a, Guad eloupe and again in Louisiana, the species is know n as mirli-ton.

In South America, the common n ames for chayote app ear to have been taken,

in some cases, from other crops, wh ich also sometimes, curiously enough, belong to

the Cucurbitaceae family. In Argentina, for example, the crop is known as papa del

aire (air potato) and in Colombia, as papa de pobre (poor m ans potato), while in

Bolivia, it is called zap allo and in Ecuad or, achocha, or achojcha. The last tw o

names are the same as those given to Cucurbita maximaDuch. ex Lam, and Cyclanthera

pedata (L.) Schrad . in these and other South American countries. These two cu lti-

vated species belong to the Cucurbitaceae family, and are native to th is area of the

continent.

Outside the Americas, the chayote is given names which clearly reflect those

used in the p laces from w hich the plant w as first introduced, although local names

do sometim es exist. In Portu gal, for example, it is known as chahiota, cahiota,

caiota, pepinella and pip inella, while in England, Australia, Mad agascar, Reunion

and Mauritius, it is called chocho or names derived from this, such as choko,

chocho, chow chow , chouchou and chouchou te. The Russian name for the plant

is cajot. On the other hand , in China, it is known as buddhass han d, while in

Italy, its comm on nam e is zucca or zucca centenaria. In several Asian coun tries, it

is given local nam es, such as vilaiti van ga (Ind ia), leong-siam (Ind onesia), laboohselyem (Malaysia), labooh tjena (Java), su-suu (Kampuchea and Vietnam),

savx, nooy thai (Laos), and ma-kheua-kreua and aeng-kariang (Thailand).

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

14/58

14 Chayote. Sechium edule(Jacq.) Sw.

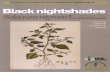

Fig. 3. Sechium edule: (a) branch with leaves, tendrils and staminate and pistillate flowers; (b)staminate flower; (c) fruits (Reprinted with permission from Nee 1993).

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

15/58

15Promoting the conservation and use of underutilized and neglected crops. 8.

3 Brief description of the crop

3.1 Botanical description

The chayote is a herbaceous, perennial, monoecious, vigorous creeper or climbingplant (Fig.3). It grow s from a single, thick root, which prod uces adventitious tuber-

ous roots (Fig.4). The stems are angular-grooved an d glabrous, and several grow

simultaneously from a single root, at least in the cultivated p lants. They thicken

towards the base and ap pear w oody, while towards the ap ex there are many thin,

firm, herbaceous branches. The leaves have grooved petioles, 8-15cm long, and are

glabrous; the blade is a firm p apiraceous-mem branou s, ovate-cordate to suborbicu-

lar, 10-30cm long, and almost as w ide at the w idest p oint, slightly 3-5 angu lar-lobed

with pointed to acum inate lobes, the m argins are totally to slightly dentate, and the

base is cordate-rectangu lar, with the sinu s open to semiclosed by th e bases of thelateral lobes (Fig.3); both blade surfaces are pubescent wh en you ng, later becoming

glabrescent, although the ad axial one is persistently pu berulent on the veins. Like

almost all Cucurbitaceae, the chayote plant d evelops tend rils for sup port. These are

sturd y, 3-5 branched, furrowed and essentially glabrous.

The flowers are un isexual; the staminates are arranged in ped unculate and erect

racemes, 10-30cm long or m ore in wild plants, and usu ally w ith the flowers arranged

in fascicular or subracemose clusters d isposed at intervals along the rachis; the pedicels

are 1-2mm long and are pu berulent; the receptacle is patelliform, 1-2mm long or less,

4-5mm wide and glabrous, with five narrow triangular sepals usually patent to re-flexed in bu ds, wh ich are 4mm long and almost 1mm wide. There are also five pet-

als, patent, green to greenish-white, wh ich are widely triangu lar, obtuse to acute, 6-

7mm long and 2-3mm wide. The stamens are five with fused filaments along almost

all of the length, forming a thick column, which normally separates into five short

branches (although sometimes three, and more rarely four, are found) (Fig.3); the

Fig. 4. Roots of chayotein a Mexican market.

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

16/58

16 Chayote. Sechium edule(Jacq.) Sw.

anthers develop at the apex of the short branches of the filaments, they are oblong and

when three are found , two of them are bithecous and one monothecous, and when

there are more than three, apparently all are bithecous, the thecas are flexuou s and the

connective has some scattered short hairs with an enlarged base. A total of 10 pore-like uncovered nectaries are found at the base of the receptacle surrou nd ing the stam i-

nal column. These are densely pu berulent to tomentose on the up per surface, and

only slightly projected beneath, in the form of a sac.

The pistillate flowers develop in the same axilla as the staminate ones. They are

usually solitary, althou gh occasionally they m ight grow in pairs or, on rare occasions,

three grow from the same pedicel; the pedicel is thin, grooved, glabrous and is 1-

3.5cm long, growing up to 8-9cm in the fruit. Many different shapes of ovary are

found , from completely unarmed and glabrous to variously indum ented or armed;

the perianth is like that of the staminate flower, but reduced in the receptacle; thestyles are joined together in a thin colum n, and the stigma is subglobose and 2-lobate;

the nectaries of the receptacle base are similar to those of the stam inate flowers.

Fig. 6. Diversity of fruits

of cultivated Sechiumedulefound in theMexican states ofChiapas and Oaxaca.

Fig. 5. Export type of fruits.

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

17/58

17Promoting the conservation and use of underutilized and neglected crops. 8.

The fruits grow either ind ividually or in p airs (rarely in greater nu mbers) on a

shared peduncle (Fig.5). They are fleshy or fleshy-fibrous, may have longitud inal

ridges or furrows, and come in many different shapes (globose, ovoid, subovoid,

pyriform, elongated pyriform), sizes (4.3-26.5cm long, 3-11cm wide), and colours

(from w hite to pale yellow colours not found in wild pop ulations to dark or light

green) (Figs.3, 6); they may be unarmed and smooth, or with varied ind um entumor armatu re, althou gh they generally conserve the characteristics of the ovary. They

may have w oody ridges or lenticels on the surface, especially when ripe; the pu lp is

pale green or whitish and tastes bitter in wild p lants and pleasant, sweet or insipid

in cultivated plants; the seed is ovoid, compressed and smooth, and germinates

within the fruit (Fig.7); in cultivated plants the seed germinates w hen the fruit is

still on the plant, while in w ild plants on ly once the fruit becomes detached.

A wide variation in the S.edule chromosome number has been documented in

the literature. Some stud ies agree that the haploid and d iploid numbers of this

species are n=12 and 2n=24 respectively (Sugiura 1938, 1940; Sobti and Singh 1961;

Goldblatt 1981, 1984), while others report accounts ofn=13 and 2n=26 (Goldblatt

1990), 2n=28 (Giusti et al. 1978) or 2n=22 (Singh 1990).

3.2 Flower biology and pollinators

To judge from the num ber of detailed stud ies available, flower biology and pollina-

tors must rank among the most researched auto-ecological aspects of S.edule

(Martinez-Crovet to 1946; Merola 1955; Giusti et al. 1978; Wille et al. 1983; Newstrom

1986, 1989). Some of the conclusions reached by these stud ies are of relevance to

chayote cultivation and conservation. Among cultivated types, for example, varia-

tions have been found in the sexual rate of prod uction of staminates and pistillateflowers. These app ear to be the result of genetic, environm ental and seasonal fac-

tors, as well as the age of the p lant. A better understanding of these factors would

Fig. 7. Vivipary.

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

18/58

18 Chayote. Sechium edule(Jacq.) Sw.

be important w hen improving the crop, and , in p articular, in the selection of types

with high productivity of female flowers and, therefore, of fruits.

As far as pollination is concerned , it is know n th at this is carried ou t by several

insect species. Additionally, there appears to be no d ifference in fru it productionrates between p lants w ith open p ollination and those which are self- or cross-polli-

nated (Newstrom 1986; Ramrez et al. 1990). On the other hand , it seems that fruit

prod uction is not affected by the nu mber of pollen grains app lied to th e stigma, or

by how often they are app lied. It also has been show n that when chayote was grown

un der greenhou se cond itions, in th e absence of pollinating insects, imm ature fruits

failed to develop and abscised p rematu rely (Aung et al. 1990).

The fact that chayote pollination d epend s on insects may be one of the reasons

why it has spread so successfully, bu t it also makes it very difficult to preserve pu re

strains, which is important not only for commercial or traditional plantation, butalso for genebanks. The relative imp ortance of chayote pollinators has been ob-

served to increase not just with ecogeograph ical and environmental factors such as

altitud e and latitud e, bu t also with the use of pesticides (Giusti et al. 1978; Wille et al.

1983; Newstrom 1986). Thus, some species of bees of the genu s Trigona that have

been identified as very efficient chayote p ollinators are foun d mostly at m edium to

high altitudes, which are pesticide-free. In contrast, other importan t pollinators,

such asApis mellifera, are most comm only foun d mainly in commercial plantations,

where pesticides are frequen tly used. Second ary pollinators of chayote include

wasps from the genera Polybia, Synoeca an d Parachrataegus as well as other smallerspecies ofTrigona.

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

19/58

19Promoting the conservation and use of underutilized and neglected crops. 8.

4 The origins of chayoteUnlike that which exists for many other crops, there does not appear to be any

archaeological evidence to establish how long S.edule has been cu ltivated . It seems

tha t the fleshy fru it, w ith its sing le soft testa seed , does not lend itself to conserva-tion and , until now, the presence of pollen grains or other structures of this spe-

cies at archaeological sites has not been reported . Instead , the most comm only

used sources for establishing the possible origin of this crop have been

ethnohistoric, artistic and linguistic, together with information on the

ecogeograph ic d istribu tion of the genetic diversity of both th e w ild and cultivated

species.

From the ethnohistorical record, we know that, at least in Mexico, chayote has

been cultivated since pre-Colombian times. The first description of chayote was

probably that of Francisco Hernnd ez, who was in Mexico from 1550 to 1560 (Cook1901), but the crop was not introdu ced into the southern par t of the continent u ntil

after the ar rival of the Spanish (Newstrom 1986, 1991). Lingu istic evidence for th is

is provided by the comm on names given to th e species in d ifferent parts of Latin

America. These clearly ind icate that the species was originally concentrated in

Mexico and Cen tral America. In many cases, these same names (especially that of

Nahu atl origin, chayote) with only slight m od ifications, are used in other areas of

the world wh ere the species was introduced. Pre-Colombian decorated p ottery has

been found in Mexico and Central America which clearly depicts chayote (Prez

1947 in N ewstrom 1991).It is the ecogeograph ic d istribution ofS.edule und er cultivation, and that of its

wild relatives, however, wh ich provides the greatest evidence for establishing the

centre of origin of this crop. Reports of explorations carried ou t du ring d ifferent

periods by variou s people an d institutions (Len 1968; Bukasov 1981; Engels 1983;

Maffioli 1983; Cruz-Len and Querol 1985; Newstrom 1985, 1986; Lira 1995a) all

concur th at the w idest variety of cultivated chayote is foun d in southern Mexico,

Guatemala and Costa Rica, at altitudes of 500-1500m.

As far as the d istribution of the w ild species and its relation to chayote is con-

cerned , there app ears to be little dou bt that the crop m ust have originated in this

area. As shown above, most of these species, and especially those most morp ho-

logically similar to chayote, are known to grow w ithin the geographic and altitud e

limits mentioned p reviously. The wild taxa ofSechium that are morph ologically

closest to chayote include the so-called wild types ofS.edule wh ich grow in the

southern part of Mexico, and Lira and Chiang (1992), a recently described endemic

species from the n orth of the State of Oaxaca (Fig.8), which w as p reviously identi-

fied sim ply as a w ild type of chayote (New strom 1985, 1986, 1990, 1991).

Both taxa have stam inate flowers, which are very similar to those of cultivated

chayote (naked nectaries at the base of the receptacle, and partially joined filaments

and side branches, with anther tissue at the apex), and fleshy fruit with very bitterpu lp. Furtherm ore, they are the only members of the genus which, like those of

S.edule, have a cleft at the ap ex from w hich the plantu le sprouts once the seed has

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

20/58

20 Chayote. Sechium edule(Jacq.) Sw.

germ inated . It has been suggested (Newstrom 1986, 1990) that the bitter taste of the

fruit is probably due to the presence of high concentra tions of cucurbitacines. These

second ary chemical comp oun ds of the plant are very frequent am ong the m embers

of the Cucurbitaceae family, and are considered to be am ong the m ost bitter sub-

stances know n. They app ear to serve as a defence against herbivores (Metcalf and

Rhod es 1990).Another two species that are morphologically similar to chayote are

S.compositum and S.hintonii (Figs.9, 10); the former is endemic to the states of

Mexico and Guerrero (Wilson 1958; Lira and Soto 1991; Lira 1995a, 1995b) and the

latter is only know n from the Mexican state of Chiapas and neighbouring areas of

Guatem ala (Donnell-Smith 1903; Standley and Steyermark 1944; Dieterle 1976; Lira

1995a, 1995b). These two sp ecies are similar to cultivated chayote in their floral

nectary and and roecium structure, but their fruit, although also fibrous and bitter,

do not have the apex cleft mentioned above. The remaining w ild sp ecies ofSechium

are morp hologically m ore similar to th e other cultivated species, S.tacaco, and , apart

from the as yet u nd escribed species from Veracruz (Nee 1993), they all grow in sou th-

ern Central America (from Nicaragua to Panama) (Pittier 1910; Wunderlin 1976,

1977, 1978; Gmez and Gm ez 1983; New strom , 1986, 1990, 1991; Lira and Chiang

1992; Lira 1995a, 1995b).

The importan ce of these wild taxa as genetic resources and their relationships

with the cu ltivated chayote mu st be verified . Further stud ies need to be carried out

on cross-breeding between m any of these species and chayote and , of course, their

poten tial for improving it should be d etermined. There follows below a synthesis of

what is know n about those taxa, wh ich app ear to be most related to chayote. In

addition, some characteristics with potential for use as genetic resources are high-lighted.

Fig. 8. Fruits of wild

Sechium edule(spiny)and S. chinantlense(unarmed).

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

21/58

21Promoting the conservation and use of underutilized and neglected crops. 8.

Fig. 9.Sechium compositum.

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

22/58

22 Chayote. Sechium edule(Jacq.) Sw.

Fig. 10. Sechium hintonii.

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

23/58

23Promoting the conservation and use of underutilized and neglected crops. 8.

4.1 Sechium edulewild types

Ecogeographical distribution The wild typ es ofS.edule mentioned here were

registered and classified as su ch by Cruz-Len (1985-86) for the State of Veracruz ,on the Gu lf of Mexico, and were later reported in the State of Oaxaca by Newstrom

(1985, 1986, 1989, 1990). It is now known that this typ e of pop ulation thrives in the

States of Veracru z, Puebla, Hidalgo and Oaxaca (Lira 1995a, 1995b; Fig.1) in south-

ern Mexico, at heights of 500-1700masl, where plan ts can be found in huge, thick

clusters. Typical habitats for these plants are damp areas such as ravines, waterfalls

and rivers or streams, where the vegetation is predominantly montane rainforest.

They are also found in the lower parts of ecotone zones with evergreen or semi-

evergreen seasonal forest.

Although some presumably wild populations ofS.edule have been reportedfrom the island of Java, Reunion (Backer and Bakhuizen 1963, Cordenoy 1895), and

in som e parts of Venezu ela (Brcher 1989), these reports h ave yet to be confirm ed,

as they have not been backed up by collections. It is also possible, at least in the case

of Venezuela, that th ese popu lations m ight have resulted from plants escaped from

cultivation (C.Jeffrey 1991, pers. comm.; L.Lpez 1991, pers. comm.).

Intraspecific variation Wild types ofS.edule have very similar (or in some cases

almost id entical) morp hological characteristics to those of the cultivated typ es of

this species. The flowers of these plan ts, for examp le, althou gh slightly biggerthan those of cu ltivated plants, have an id entical staminal structure. Their fruit

also has an ap ex cleft from w hich th e plantu le sprou ts, once the seed has germ i-

nated.

The most significant morphological differences between cultivated and wild

chayote are the d ifference in size of the vegetat ive and reprod uctive structures. Wild

plants are more robust, for example, and their leaves, flowers and staminate inflo-

rescence are bigger than those foun d in cultivated plants. On the other hand , as will

be seen below, althou gh the fruit of most of the populations of the State of Veracruz

have a d ifferent m orphology, strict comparisons between this species and cultivated

typ es are obviously not possible. Yellow or w hite fru its, for examp le, have not been

recorded for these plants. Moreover, as pointed ou t above, the pu lp has a bitter

taste and is usually more fibrous.

Such differences are even more accentuated in the populations from Oaxaca.

The fruits, as well as having fibrous p ulp and a bitter taste, are more hom ogeneous

in shape (globulate), colour (dark green) and prickles (very prickly) (Lira 1995a,

1995b). Another important d ifference between these wild pop ulations is their chro-

mosome number: for those of Veracruz the haploid number reported is n=12

(Palacios 1987), while for those of Oaxaca the haploid number of n=13 has been

determined (Mercado et al. 1993; Mercado an d Lira 1994). Accord ing to N ewstrom(1991), the morphological variation of the p opulations of Veracruz, their p roximity

to cultivated areas, and the fact that six fruits have been obtained from experimental

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

24/58

24 Chayote. Sechium edule(Jacq.) Sw.

that these pop ulations could be of hybrid origin.

Phenology Wild pop ulations ofS.edule flower from Apr il to December an d give

fruit from Septem ber to Janu ary.

Potential importance Studies have not been carried out on the potential these

plants m ight have as a resource for improving chayote. However, given their mor-

phological similarity, and their potential for successful hybrid ization with cultivated

chayote p lants, these populations should be among the first to be evaluated, espe-

cially for resistance to disease and pests. Hybridization program mes with culti-

vated typ es shou ld clearly be started.

4.2 Sechium chinantlenseLira & Chiang

Ecogeographic distribution This species is endemic to a very sm all region of Mexico,

in the north of the State of Oaxaca, near the boundary with the State of Veracruz

(Fig.1). It thrives at altitudes of 20-800m. In lower-lying areas, it grows in rainforest,

and in higher zones in the ecotone with montane rainforest. The S.chinantlense spe-

cies shou ld be p laced on the list of endangered species, since natural vegetation in the

very restricted areas where it is found is currently seriously threatened.

Representative m aterial from the p opulations of this species was first collected

by G. Martnez-Caldern between 1940 and 1941 (G. Martnez-Caldern 369, 458,826 in GH , MICH and MEXU) and R. McVaugh in 1962 (R. McVaugh 21801 in MICH)

and were identified asAhzolia composita (J.D. Smith) Standley and Steyermark. Years

later, New strom (1986, 1989, 1990, 1991) included them in wild typ es III ofS.edule.

She pointed out that the characteristics of their staminate flowers, the presence of

smooth fru it and some of their chemical properties ind icated a close relationship to

S.compositum . She also suggested that they might have resulted from hybridization

between this last species and cultivated types of chayote. However, it was precisely

the stru cture of the stamens of these p lants, the morp hological and biological char-

acteristics of the fruit (with germination apex cleft), and their reproductive incom-

patibility with cultivated an d w ild p lants ofS.edule(Castrejn and Lira 1992), which

permitted them to be identified as a new species (Lira and Chiang 1992). The fact

that S.compositum is not foun d in Oaxaca d oes not ind icate that it is a plant of hy-

brid origin, at least not a hybrid between this and any other species in the genus.

Phenology Sechium chinantlense flowers from Augu st to Novem ber and gives fruit

from Septem ber to February. In the southern par t of its area of d istribu tion, the

phenological effects are seen earlier than in the populations found further north,

where it is lower and drier. Thus, in the former areas, flowering begins in August,

and fruit from October to December, wh ile in the latter areas, flowering d oes notbegin until Novem ber, and fruit can be found from December to February.

Common names This species is know n in Spanish as cabeza de chango, chayote

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

25/58

25Promoting the conservation and use of underutilized and neglected crops. 8.

cimarrn and chayote d e mon te, and in Chinanteco as n , rign-cua and rign-

kiu-moo.

Potential importance The plants of this species are found in areas with highrelative humid ity, and , as mentioned above, there is a p henological variation which

is apparent ly related to the microclimatic differences of the p laces where its popula-

tions grow. However, whether these characteristics are imp ortant for the improve-

ment of chayote has still to be determined . Although detailed stud ies do not exist

on the crossability ofS.chinantlense with S.edule, preliminary data from Castrejn

and Lira (1992), show that hybr ids cannot be obtained from these two species. It

may be that they are not crossable, because of the difference in their chromosome

number. For S.edule, diploid numbers of 2n=22, n=24 and n=26, among others,

have been registered, while for S.chinantlense, a diploid number of 2n=30 (Mercadoet al. 1993) has been reported .

4.3 Sechium compositum(J.D. Smith) C.Jeffrey

Ecogeographic distribution Distribution ofS.compositum covers some of the south-

ern part of the State of Chiapas in Mexico, as well as neighbouring areas in Guatemala

(Quetzaltenango, Escuintla and Suchitepequez) (Fig.1). This species is found at a wide

range of altitudes (50-2100m), on sites which usually contain ravines, riverbanks and

waterfalls. Vegetation m ay be primary or secondary, derived from montane rainforestor evergreen or semi-evergreen seasonal forest. It is also frequently found growing in

coffee plantations. Many S.compositum populations have been found in the south of

Mexico, in the State of Chiapas, within the confines of the Biosphere Reserve El Triunfo,

thereby ensuring its conservation und er natu ral cond itions (Lira 1995a, 1995b).

Intraspecific variation The S.compositum fruits have been d escribed in the litera-

ture as longitudinally ridged, with prickles on the ridges (Dieterle 1976; Donnell-

Smith 1903). However, dur ing field work in Chiapas and Guatem ala, some popu la-

tions were foun d with fruit, as described in the literature, wh ile others were com-

pletely smooth and unarmed (Lira 1995a, 1995b).

Phenology This species flowers from September to January, and presents fruits

from October-November to February.

Common names S.compositum is known by several common names, most of

which are similar to those ofS.edule. Thus, in Chiapas, it is know n mainly as chay-

ote de caballo, or hu isqu il de cochi and also as xmasil or xmasin, both of Mm e

origin, bu t the mean ings of which are unknown. In Guatem ala, nam es such as

huisquil de monte have been recorded, and Dieterle (1976) reports the namehu isquil de ratn (forAhzolia composita).

Uses In Chiapas, the chop ped -up roots are mixed w ith water, and used as a soap

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

26/58

26 Chayote. Sechium edule(Jacq.) Sw.

substitute and to kill horse fleas. Moreover, some of the comm on names (chayote

de caballo, chayote d e burro and hu isquil de cochi) seem to suggest that the fruit,

in spite of being b itter and possibly having a h igh cucurbitacines content, could be

used for consump tion by domesticated animals.

Potential importance The fruit ofS.compositum can be stored for several mon ths,

with no recorded effect on turgid ity or hu mid ity. Attemp ting to incorporate this

characteristic into cultivated chayote may be of interest in solving storage or conser-

vation problems. Cross-breeding between th is species and cultivated chayote has

not been explored. However, a hybrid p lant obtained from the cross between

S.compositum and a cultivated p lant ofS.edule has been reported. This plant even

produced fruit in the CATIE genebank in Costa Rica (Newstrom 1986). It shou ld be

pointed out that the hap loid chromosom e num ber of this species is n=14 (Mercadoet al. 1993; Mercad o an d Lira 1994).

4.4 Sechium hintonii(P.G. Wilson) C.Jeffrey

Ecogeographic dis tribution Sechium hintonii is a species end emic to a small

area of Mexico. Unt il a short tim e ago, it was only know n from the types col-

lected w ithin the Tem ascaltep ec District in the State of Mexico. Recent ly, it was

red iscovered on a site near on e of these localities (Lira and Soto 1991) and , shortly

afterward s, a small pop ulation w as foun d a little furth er south, in the State ofGuerrero (Lira 1995a; Fig.1). This species has been fou nd on sites at altitud es of

1300-1510masl, in a climat ic-vegetation t ran sition zon e. The climate in this re-

gion is hot to semi-hot. The site in the State of Mexico cou ld be d escribed a s an

ecotone, between deciduous seasonal forest and Quercus forest, but it is seri-

ously threatened by seasonal agricultu ral activities. Although the vegetation in

the Gu errero site is similar, it ap pears to h ave more in comm on w ith the d ecidu -

ous seasonal forest, and it is in a mu ch better state of conservation than that of

the State of Mexico.

A few specimens from sites located in the municipalities of Autln and

Cuautitln, in the State of Jalisco in western Mexico (Wilbur 2456, McVaugh 19958

in MICH, Vzqu ez 4069, Cuevas and Lpez 3247 en ZEA), could belong to this spe-

cies. They do, however, differ in some respects from th e most typ ical samples, mainly

in the size of the fruit and the pedicels of the staminate flowers, as well as in the

outline of the leaves and the shape of the lobules. Other characteristics of the fruits

also differ (they are smaller with prickles only at the base, and they do not have

backward -turning p rickles). If this material could be identified as belonging to

S.hintonii, then its area of d istribution w ould be widened considerably towards the

nor thw est. A recent visit to the sites failed to do th is, how ever, which is unfortu -

nate, since the vegetation is in a far better state of conservation than in th e States ofMexico and Guerrero (Lira 1995a, 1995b).

Phenology Sechium hintonii flowers from Augu st to Novem ber, and prod uces fruit

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

27/58

27Promoting the conservation and use of underutilized and neglected crops. 8.

from October to December. Field observat ions revealed that the aerial parts of this

species dry after December, bu t sprou t again the following year in April, just before

the start of the rainy season.

Common names In the State of Mexico, it is known as chayotillo.

Potential importance No information is available and all that can be said is that,

as in the case of wild types ofS.edule, this species could be a sou rce of resistance to

d iseases and p ests. It is not know n, unfortun ately, whether it can be crossed with

chayote. All that is known in this respect is that its haploid chromosome num ber is

n=14 (Mercado et al. 1993; Mercado and Lira 1994). Sechium hintonii is clearly an

endangered species, as it is end emic to a relatively small area, with know n p opu la-

tions that thrive only in areas which are currently seriously affected by deforesta-tion and agricultural activities. In add ition, germplasm collections wh ich w ould at

least guarantee its conservation ex situ do not exist.

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

28/58

28 Chayote. Sechium edule(Jacq.) Sw.

5 Uses and propertiesChayote is basically used for human consumption, not just in the Americas but in

many other countries. In add ition to the fruit, stems and tender leaves (usu ally known

as quelites), the tuberous parts of the adventitious roots (in Mexico calledchayotextle, cueza, camochayote, chayocamote and chinchayote, and in Gu ate-

mala and El Salvador ichintla, echintla, chintla or chinta) are also eaten. They are

mu ch appreciated as a vegetable and are either just boiled or used in stews and des-

serts (Cook 1901; Terraciano 1905; Mattei 1907; Hoover 1923; Lionti 1959; Ory et al.

1979; Bukasov 1981; Williams 1981; Esquinas and Gulick 1983; Orea-Coria and

Englemann 1983; Cruz-Len 1985-86; Cruz-Len and Querol 1985; New strom 1985,

1986, 1990, 1991; Dubravec 1986; Lira 1988; Flores 1989; Walters 1989; Au ng et al. 1990;

Chakravar ty 1990; Lira and Bye 1992; Yang and Walters 1992; Engels and Jeffrey 1993;

Lira and Torres 1993; Baral et al. 1994; Cheng et al. 1995; Sharma et al. 1995).

Table 3. Chemical composition (% or mg/100 g) of fruit, young stems and roots of

Sechium edule

Component Fruit Seed Stem Root

Calories 26.0-31.0 60.0 79.0

Humidity (%) 89.0-93.4 89.7 79.7

Soluble sugar (%) 3.3 4.2 0.3 0.6Starch (%) 0.2 1.9 0.7 13.6

Proteins (%) 0.9-1.1 5.5 4.0 2.0

Fats (%) 0.1-0.3 0.4 0.2

Carbohydrates (%) 3.5-7.7 60.0 4.7 17.8

Fibre (%) 0.4-1.0 1.2 0.4

Ashes (%) 0.4-0.6 1.2 1.0

Ca (mg) 12.0-19.0 58.0 7.0

P (mg) 4.0-30.0 108.0 34.0

Fe (mg) 0.2-0.6 2.5 0.8Vitamin A (mg) 5.0 615.0

Thiamin (mg) 0.03 0.08 0.05

Riboflavin (mg) 0.04 0.18 0.03

Niacin (mg) 0.4-0.5 1.1 0.9

Ascorbic acid (mg) 11.0-20.0 16.0 19.0

Sources: Engels 1983; Aung et al. 1990.

The edible parts ofS.edule (Table 3) are relatively low in fibre, protein and vita-mins compared w ith other vegetables. Nevertheless, they have a high caloric and

carbohyd rate content, especially in you ng stems, root and seed, and the m icro and

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

29/58

29Promoting the conservation and use of underutilized and neglected crops. 8.

macronu trient content of the fruit is adequ ate. The fruits, and the seed especially,

are rich in several importan t am ino acids such as aspar tic acid , glutamic acid, ala-

nine, arginine, cistein, phenylalanine, glycine, histid ine, isoleucine, leucine, methion -

ine (only in the fru it), proline, serine, tyrosine, threonine and valine (Flores 1989).Many of these nu tritional characteristics make chayote part icularly suitable for hos-

pital d iets (Liebrecht and Seraphine 1964; Silva et al. 1990).

Chayote is also used in other w ays in different parts of the world. The softness

of the fru it flesh makes it particularly suitable for giving consistency to baby foods,

juices, sauces an d pastes. Because of th e flexibility an d strength of th e stems, they

are used in some p laces, such as Reun ion, in handicrafts to make baskets and hats

(Cordenoy 1895 in Newstrom 1991). In India, as in the Americas, the fruit and roots

are not only used as food bu t also as fodder for cattle (Chakravar ty 1990).

Medicinal use of chayote has also been d ocum ented in th e literature. Data com-piled in recent stud ies highlight the u se of decoctions mad e from the leaves or fruits

to relieve urine retention and bu rning d ur ing urination or to dissolve kidney stones,

and as a comp lementary treatment for arteriosclerosis and hyp ertension (Lira 1988;

Flores 1989; Yang and Walters 1992). In the Yucatan Pen insu la, where kidn ey disor-

ders are frequent, these decoctions are considered to be effective and have been in

use since colonial times (Lira 1988). The diu retic properties of the leaves and seeds,

and the cardiovascular and anti-inflammatory properties of the leaves and fruit,

have been confirmed by p harm acological stud ies (Bueno et al. 1970; Lozoya 1980;

Salama et al. 1986, 1987; Ribeiro et al. 1988).Dehydration of the fruit has been carried ou t in Mexico and other countries in

an attempt to increase the shelf life of chayote and make it more widely available,

perhap s even for industrial use (A. Cruz-Len, pers. comm.). Results are said to be

prom ising; jams and other types of sweets have been man ufactured and dehydrated

fruits have been conserved for later use as a vegetable. On the other hand , some

coun tries, such as the Philipp ines, have successfully u sed chayote p lants in m ixed

plantations designed specifically for soil recovery and/ or conservation (Costales

and Costales 1985).

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

30/58

30 Chayote. Sechium edule(Jacq.) Sw.

6 Diversity and genetic resourcesFew cultivated sp ecies produ ce fru its with such d iverse morph ology, mainly with

regard to form , size, surface textu re and , to a lesser degree, colour. In add ition to

this morph ological d iversity, chayote also has been d ocum ented as having a yieldwhich varies considerably. All this wou ld seem to point to the fact that this genus

app ears to have enorm ous p otential for genetic resources. However, very little is

known in this field, mainly because experimental materials are needed and, until

now, efforts to conserve and stud y these resources have had less than satisfactory

results. The endocarp ic and precocious germination of the S.edule seed seriously

hind ers these tasks because it means that conservation cannot be carried ou t u sing

orthod ox methods. Instead , this has to be done in field genebanks wh ich are expen-

sive and comp licated to ad minister and maintain, or in vitro. In spite of this, during

the 1980s, several institutions show ed interest in d eveloping germp lasm banks inorder to conserve and stud y mainly cu ltivated chayote p lants, but also some of its

wild relatives. This section attemp ts to give a general overview of the diversity

docum ented for the plants in these collections as well as of the few samp les of what

migh t be som e of its closest relatives.

The morphological characteristics of cultivated chayote fruit are the most obvi-

ous sign of its diversity. Different authors have attemp ted to catalogue this varia-

tion which also has been useful in ind icating the place of origin of chayote. Jacquin

(1788), for example, said there were two cultivated types in Cuba, chayote and

chayote francs. Herrera (1870) gave d ifferent nam es to cultivated Mexican chay-otes. Although he d id not describe them, the names he chose obviously reflected

the more salient characteristics chayote peln (bald chayote), chayotito (small

chayote) and chayotito gachu pn (well-bred or elegant chayote).

In Puerto Rico, Cook (1901) distinguished five different varieties of fruit with

varying combinations of shape and colour (roun d wh ite, long wh ite, pointed green,

broad green, oval green). Years later, Guzm n (1947) reported two var ieties from El

Salvador with fruit of different colours (white and green) while Whitaker and Davis

(1962) said that there w ere 24 varieties in Guatemala with fruits of different shapes,

colour and surface textu re. More recently, Len (1968) show ed th at the greatest

variety is to be found between Gu atemala and Panam a, where there are at least 25

varieties.

However, these and other attempts to classify the d iversity of cultivated chayote

were never based on systematic collections and so the variation observed was not

comp letely representative. A wider samp le of chayote variation was not stud ied,

catalogued and classified more systematically un til the beginn ing of the 1980s. This

was possible thanks to several collecting efforts (Engels 1983; Maffioli 1983; Cruz-

Len and Querol 1985; Newstrom 1985, 1986), which resulted in the setting up of

the two most imp ortant germplasm collections to date. One of these was located in

the CATIE in Turrialba, Costa Rica, and the other was in the Regional UniversityCentre in H uatusco, Veracruz, Mexico. Duplicates of some of these collections are

known to have been sent to the Institute for Forestry and Farming Research, in

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

31/58

31Promoting the conservation and use of underutilized and neglected crops. 8.

Guanajuato, Mexico (New strom 1986; Bettencourt an d Konopka 1990).

Unfortunately, factors such as frost, drought an d root disease, together w ith the

difficulties involved in handling the physical and biological variables (control of

pollination for examp le) grad ually led to the decline of these collections. Accord ingto N ewstrom (1986), between 1975 and 1980 the CATIE collection grew to 375 acces-

sions, mostly from Costa Rica, Guatem ala and H ond uras. This nu mber, how ever,

was red uced to almost half by 1981 (202 accessions accord ing to Newstrom, 1986)

and , although there w as a slight increase in 1983 (215 accord ing to Engels, 1983), in

1985 the number was redu ced drastically to 111 (Newstrom 1986). The same thing

happen ed to the Mexican collections and between 1988 and 1991, the three collec-

tions were destroyed, app arently because of lack of fun ds for their upkeep (Cruz-

Len, pers. comm .).

According to a recent directory of germplasm collections (Bettencourt andKonopka 1990), another two institutions also conserve (or have conserved) collec-

tions of cultivated S.edule; one of these is the Cam pos Azu les Experimental Centre

of the Higher Institute of Farming Sciences of Nicaragua (12 accessions of appar-

ently local Nicaraguan types), and the other is the National Centre of Plant Re-

search-EMBRAPA in Brazil (50 accessions of local Brazilian types). Unfortu nately,

this is all that is known abou t these two collections. In the references, no ad ditional

information is given on activities or the current state of the collections, although

Brenes (1996) points ou t that the Brazilian collection also has d isapp eared. These

losses are un fortun ate, since at some point these genebanks betw een them h ousedmore than 500 accessions. Most of them came from trad itional market gard ens in

the west, centre, south and southeast of Mexico as well as from Brazil and several

Central American countries (mainly Costa Rica and Guatemala), as well as some

obtained from commercial plantations.

Fortun ately, some d etailed stud ies were published (Engels 1983; Maffioli 1983;

Cruz-Len and Querol 1985; Newstrom 1985, 1986) documenting the variation in

the sam ples collected in Mexico and Central America and making it possible to ana-

lyze this. A summ ary of the most relevant data is given in Table 4. It can be seen

that these collections were, withou t any doubt, very representative of the d iversity

of this crop since they includ ed sam ples from d ifferent areas of Mexico and Centra l

America where this crop has originated and developed its distinctive features.

In addition, the characteristics of the sam ples d iscussed in the above-mentioned

studies show the significant variation of external features of the fruits such as colour,

shape, size and nu mber of spines and/ or lenticels present on the surface. In some

cases (Maffioli 1983; Cruz-Len and Querol 1985; Newstrom 1986) information is

given on the internal characteristics of the fruit such as fibre content and consis-

tency of the flesh, and reference is also mad e to p lant p rodu ctivity (Cruz-Len and

Querol 1985) and even to the taste of the fruit flesh (Cruz-Len and Querol 1985;

Newstrom 1986). Although these collections were intended m ainly to conserve thediversity of cultivated S.edule plants, the Costa Rica collection also had one

S.compositum and several S.tacaco accessions, while that of Huatu sco managed to

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

32/58

Table 4. Summary of the variation for the most important characteristics* of chayote fruits and p

Central America, as recorded in the germplasm collections from Mexico and Costa Rica

Costa Rica Guatemala Honduras/Panama

Length (cm) 4.8-26.5 4.9-16.4 7.1-15.9

Width (cm) 4.7-19.3 4.6-11.6 6.6-10.9

Thickness (cm) 4.4-11.0 4.3-8.7 6.8-9.9Weight (g) 58-1207 48-540 299-398

Volume (cm3) n.a. n.a. n.a.

Colour white, light green, white, light green, light green,

dark green dark green dark green

Shape pyriform,subpyriform, pyriform,subpyriform, pyriform,subpyriform,

ovoid, flattened, spheroid ovoid, flattened, spheroid ovoid, spheroid

Spines absent, few, absent, few, few, intermediate,

intermediate, many intermediate, many many

Furrows absent, shallow, absent, shallow, shallow,intermediate,intermediate, deep intermediate deep

Ridges n.a. n.a. n.a.

Lenticels absent, few, absent, few, few, intermediate,

intermediate,many intermediate many

Texture of pulp n.a. n.a. n.a.

Taste of pulp n.a. n.a. n.a.

Fibres of pulp n.a. n.a. n.a.

Days to harvest n.a. n.a. n.a.

Fruits/plant n.a. n.a. n.a.

* The most common data found for each characteristic are printed in bold.n.a. = not available.Sources: Engels 1983; Maffioli 1983; Cruz-Len and Querol 1985; Newstrom 1985, 1986.

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

33/58

Table 5. Summary of the variation recorded for 11 fruits, collected in wild populations of Sechiu

from Veracruz, Mexico.

Length Width Thickness Weight Volume Shape Colour of Taste

(cm) (cm) (cm) (g) (cm3) skin

7.1 6.2 4.7 109.9 106.7 pyriform light green bitter

8.1 6.8 5.3 155.7 152.7 spheroid dark green bitter

9.1 5.6 4.7 116.8 114.0 oblong dark green bitter7.6 5.6 4.8 108.7 106.8 pyriform dark green bitter

7.2 5.7 4.8 104.3 102.2 spheroid light green bitter

8.5 6.4 5.1 132.8 129.1 pyriform dark green bitter

7.5 6.0 4.9 114.6 113.0 pyriform dark green bitter

7.7 6.6 5.3 144.2 140.8 spheroid dark green bitter

7.8 5.2 4.2 94.8 93.6 pyriform dark green bitter

5.9 5.2 4.6 79.4 77.7 spheroid dark green bitter

6.1 5.6 4.5 87.3 85.0 spheroid light green bitter

Source: Cruz-Len and Querol 1985.

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

34/58

34 Chayote. Sechium edule(Jacq.) Sw.

conserve several representative plants from wild S.edulepopulations from Veracruz.

These were also described and a certain d egree of diversity was found in the charac-

teristics of the fruit (Table 5).

The analyses carried out by Engels (1983) and Newstrom (1986) on the variationin cultivated types contained in the collections revealed the following:

The variation registered for characteristics referring to size and shap e of the fruit is

app arently continu ous.

In most cases, the descriptors w ith no app arent relation to the size of the fruit w ere

independent among themselves, and no significant differences were found in the

diversity of samp les from Central American coun tries, nor between them and those

of Mexico.

Consequently, it is very difficult to catalogue the variation of chayote as cultivars

and it has been d ecided , therefore, to refer to them as landraces.Another outstand ing aspect of the information available in chayote germplasm cata-

logues is the m arked d ifference between the d iversity handled by trad itional farm-

ers and th at wh ich is produced for comm ercial reasons. For examp le, in the vast

majority of cases, samples of fruit collected from trad itional market gard ens vary in

size, colour and taste, and generally they are par tially or entirely covered with spines.

Comm ercial prod uction, how ever, has to conform to the demand s or quality norms

imp osed by export m arkets (FAO 1982, in Flores 1989). Accord ing to these, the fru it

should be relatively uniform in size and other external morp hological features (py-

riform fruit, light green or white, smooth or unarmed, approximately 15cm longand weighing app roximately 450g), in p resentation (no signs of prematu re germi-

nation, physical damage or marks produced by pathogens) and in texture and flesh

flavou r (soft and pleasant) (Fig.6).

Taking th ese commercial restraints into accoun t, and the fact tha t little or noth -

ing is known abou t the h ered ity of man y m orph ological features of chayote fruit,

we can expect that it will be difficult to use trad itional m arket gard en cultivated

types of chayote in imp rovement p rogramm es wh ich breed for comm ercialization

of chayote. How, then , can the variation wh ich exists in trad itionally cultivated

chayote be exploited ? Or, in other w ords, what is the justification for conserv ing

and studying it?

Although the resistance of chayote germplasm accessions to abiotic and biotic

environmental variables, such as p ests and d isease, has never been determined, it

can be assumed that there must be d iversity with regard to these factors. Data pro-

vided by Cruz-Len and Querol (1985) on plant behaviour during a yearly cycle

(Table 4) clearly show ed there is diversity in how early plants p rodu ce fruit (nu mber

of days to harvest) and how productive chayote plants are (number of fruits per

plant). Some typ es produced fruit from 102 to 331 days after sowing, with p rodu c-

tion varying from 374 to 521 fruits on plants w ith medium-du ration fruit formation

(208-239 days) and up to 402 fru its for more precocious p lants (102 days). Furtheranalysis of this variation may make it p ossible for some of these types to be u sed for

improving comm ercial chayote yields.

-

8/3/2019 Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under Utilized and Neglected Crops. 08 - Chayote

35/58

35Promoting the conservation and use of underutilized and neglected crops. 8.

In spite of failures experienced to date in the ex situ conservation ofSechium

genetic resources, interest in the su bject has not been comp letely lost. In Costa Rica,

for example, in vitro conservation was another method w hich w as explored to see if

there was any w ay it could be used as an alternative to field genebank collections(Alvarenga and Villalobos 1988; Alvarenga 1990). Althou gh the p reliminary resu lts

obtained are still at experimental level, they ap pear to be prom ising. These results

showed that it is possible to stop the growth of explants by submitting them to

individu al and / or combined treatment using osm otic stress (4-8% sucrose), low tem-

perature (16-22C) or acetylsalicylate acid (10-9 up to 10-3M). The most effective

combinations, which neither damaged nor caused m orph ological change in the ex-

plants, were osmotic pressure at 6% sucrose and a temperatu re of 18C.

In 1992, a new chayote germ plasm collection w as set up in the Ujarras Valley in

Costa Rica. This is an extensive conservation initiative based on the Costa RicanSechium Germplasm Bank Project which was set up by private and governmental

institutions from Costa Rica and Spain (National University of Costa Rica,

Coopechayote R.L. and the Spanish International Cooperation Agency) with the

sup por t of the Costa Rican National Comm ission for Plant Genetic Resources (Brenes

1996). The project has been w ell received an d it has recently been joined by other

institutions from Costa Rica such as The Association of Sustainable Agricultural

Prod ucers of the Ujarras Valley (in place of Coopechayote R.L.), the University of

Costa Rica and the Ministry of Agricultu re and Poultry.

The main objective of this project is not just to set up a field genebank collectionof cultivated chayotes in Costa Rica, but also to form a world reservoir of genetic

resources of the genu s Sechium. One of the essential parts of the project will be to

collect systematically germ plasm for the entire genu s. This will be conserved ini-

tially as field genebank collections and a d atabase consisting mainly of information

related to characterization, conservation, improvement and use w ill be established .

Additionally, it is hop ed that the p roject w ill encourage the in situ conservation of

wild species, the d evelopm ent of efficient m ethods for the p hytosanitary hand ling

of collections as w ell as the stu dy of seed germ ination of wild and cultivated species

in the genu s and the vegetative propagation of wild species and of the other culti-

vated species S.tacaco. Medium-term aims of the project include fur thering stud ies

on the biochemical characterization of the collections, carrying out the research

needed to be able to set up an in vitro collection representative of the main field

genebank collection, and identifying prom ising material for th e genetic imp rove-

ment of the two cu ltivated species.