EN BANC G.R. No. L-63915 April 24, 1985 LORENZO M. TAÑADA, ABRAHAM F. SARMIENTO, and MOVEMENT OF ATTORNEYS FOR BROTHERHOOD, INTEGRITY AND NATIONALISM, INC. [MABINI], petitioners, vs. HON. JUAN C. TUVERA, in his capacity as Executive Assistant to the President, HON. JOAQUIN VENUS, in his capacity as Deputy Executive Assistant to the President , MELQUIADES P. DE LA CRUZ, in his capacity as Director, Malacañang Records Office, and FLORENDO S. PABLO, in his capacity as Director, Bureau of Printing, respondents. ESCOLIN, J.: Invoking the people's right to be informed on matters of public concern, a right recognized in Section 6, Article IV of the 1973 Philippine Constitution, 1 as well as the principle that laws to be valid and enforceable must be published in the Official Gazette or otherwise effectively promulgated, petitioners seek a writ of mandamus to compel respondent public officials to publish, and/or cause the publication in the Official Gazette of various presidential decrees, letters of instructions, general orders, proclamations, executive orders, letter of implementation and administrative orders. Specifically, the publication of the following presidential issuances is sought: a] Presidential Decrees Nos. 12, 22, 37, 38, 59, 64, 103, 171, 179, 184, 197, 200, 234, 265, 286, 298, 303, 312, 324, 325, 326, 337, 355, 358, 359, 360, 361, 368, 404, 406, 415, 427, 429, 445, 447, 473, 486, 491, 503, 504, 521, 528, 551, 566, 573, 574, 594, 599, 644, 658, 661, 718, 731, 733, 793, 800, 802, 835, 836, 923, 935, 961, 1017-1030, 1050, 1060-1061, 1085, 1143, 1165, 1166, 1242, 1246, 1250, 1278, 1279, 1300, 1644, 1772, 1808, 1810, 1813-1817, 1819-1826, 1829-1840, 1842-1847. b] Letter of Instructions Nos.: 10, 39, 49, 72, 107, 108, 116, 130, 136, 141, 150, 153, 155, 161, 173, 180, 187, 188, 192, 193, 199, 202, 204, 205, 209, 211-213, 215-224, 226-228, 231-239, 241-245, 248, 251, 253-261, 263-269, 271-273, 275-283, 285- 289, 291, 293, 297-299, 301-303, 309, 312-315, 325, 327, 343, 346, 349, 357, 358, 362, 367, 370, 382, 385, 386, 396-397, 405, 438-440, 444- 445, 473, 486, 488, 498, 501, 399, 527, 561, 576, 587, 594, 599, 600, 602, 609, 610, 611, 612, 615, 641, 642, 665, 702, 712-713, 726, 837-839, 878-879, 881, 882, 939-940, 964,997,1149-1178,1180-1278. c] General Orders Nos.: 14, 52, 58, 59, 60, 62, 63, 64 & 65. d] Proclamation Nos.: 1126, 1144, 1147, 1151, 1196, 1270, 1281, 1319-1526, 1529, 1532, 1535, 1538, 1540-1547, 1550-1558, 1561-1588, 1590-1595, 1594- 1600, 1606-1609, 1612-1628, 1630-1649, 1694-1695, 1697-1701, 1705-1723, 1731-1734, 1737-1742, 1744, 1746-1751, 1752, 1754, 1762, 1764-1787, 1789-1795, 1797, 1800, 1802-1804, 1806-1807, 1812-1814, 1816, 1825-1826, 1829, 1831-1832, 1835-1836, 1839-1840, 1843-1844, 1846-1847, 1849, 1853-1858, 1860, 1866, 1868, 1870, 1876-1889, 1892, 1900, 1918, 1923, 1933, 1952, 1963, 1965-1966, 1968-1984, 1986-2028, 2030-2044, 2046-2145, 2147-2161, 2163-2244. e] Executive Orders Nos.: 411, 413, 414, 427, 429- 454, 457- 471, 474-492, 494-507, 509-510, 522, 524- 528, 531-532, 536, 538, 543-544, 549, 551-553, 560, 563, 567-568, 570, 574, 593, 594, 598-604, 609, 611- 647, 649-677, 679-703, 705-707, 712-786, 788- 852, 854-857.

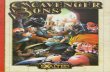

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

EN BANCG.R. No. L-63915 April 24, 1985LORENZO M. TAÑADA, ABRAHAM F. SARMIENTO, and MOVEMENT OF ATTORNEYS FOR BROTHERHOOD, INTEGRITY AND NATIONALISM, INC. [MABINI], petitioners, vs.HON. JUAN C. TUVERA, in his capacity as Executive Assistant to the President, HON. JOAQUIN VENUS, in his capacity as Deputy Executive Assistant to the President , MELQUIADES P. DE LA CRUZ, in his capacity as Director, Malacañang Records Office, and FLORENDO S. PABLO, in his capacity as Director, Bureau of Printing, respondents. ESCOLIN, J.:Invoking the people's right to be informed on matters of public concern, a right recognized in Section 6, Article IV of the 1973 Philippine Constitution, 1

as well as the principle that laws to be valid and enforceable must be published in the Official Gazette or otherwise effectively promulgated, petitioners seek a writ of mandamus to compel respondent public officials to publish, and/or cause the publication in the Official Gazette of various presidential decrees, letters of instructions, general orders, proclamations, executive orders, letter of implementation and administrative orders.Specifically, the publication of the following presidential issuances is sought:a] Presidential Decrees Nos. 12, 22, 37, 38, 59, 64, 103, 171, 179, 184, 197, 200, 234, 265, 286, 298, 303, 312, 324, 325, 326, 337, 355, 358, 359, 360, 361, 368, 404, 406, 415, 427, 429, 445, 447, 473, 486, 491, 503, 504, 521, 528, 551, 566, 573, 574, 594, 599, 644, 658, 661, 718, 731, 733, 793, 800, 802, 835, 836, 923, 935, 961, 1017-1030, 1050, 1060-1061, 1085, 1143, 1165, 1166, 1242, 1246, 1250, 1278, 1279, 1300, 1644, 1772, 1808, 1810, 1813-1817, 1819-1826, 1829-1840, 1842-1847.b] Letter of Instructions Nos.: 10, 39, 49, 72, 107, 108, 116, 130, 136, 141, 150, 153, 155, 161, 173, 180, 187, 188, 192, 193, 199, 202, 204, 205, 209, 211-213, 215-224, 226-228, 231-239, 241-245, 248, 251, 253-261, 263-269, 271-273, 275-283, 285-289, 291, 293, 297-299, 301-303, 309, 312-315, 325, 327, 343, 346, 349, 357, 358, 362, 367, 370, 382, 385, 386, 396-397, 405, 438-440, 444- 445, 473, 486, 488, 498, 501, 399, 527, 561, 576, 587, 594, 599, 600, 602, 609, 610, 611, 612, 615, 641, 642, 665, 702, 712-713, 726, 837-839, 878-879, 881, 882, 939-940, 964,997,1149-1178,1180-1278.c] General Orders Nos.: 14, 52, 58, 59, 60, 62, 63, 64 & 65.d] Proclamation Nos.: 1126, 1144, 1147, 1151, 1196, 1270, 1281, 1319-1526, 1529, 1532, 1535, 1538, 1540-1547, 1550-1558, 1561-1588, 1590-1595, 1594-1600, 1606-1609, 1612-1628, 1630-1649, 1694-1695, 1697-

1701, 1705-1723, 1731-1734, 1737-1742, 1744, 1746-1751, 1752, 1754, 1762, 1764-1787, 1789-1795, 1797, 1800, 1802-1804, 1806-1807, 1812-1814, 1816, 1825-1826, 1829, 1831-1832, 1835-1836, 1839-1840, 1843-1844, 1846-1847, 1849, 1853-1858, 1860, 1866, 1868, 1870, 1876-1889, 1892, 1900, 1918, 1923, 1933, 1952, 1963, 1965-1966, 1968-1984, 1986-2028, 2030-2044, 2046-2145, 2147-2161, 2163-2244.e] Executive Orders Nos.: 411, 413, 414, 427, 429-454, 457- 471, 474-492, 494-507, 509-510, 522, 524-528, 531-532, 536, 538, 543-544, 549, 551-553, 560, 563, 567-568, 570, 574, 593, 594, 598-604, 609, 611- 647, 649-677, 679-703, 705-707, 712-786, 788-852, 854-857.f] Letters of Implementation Nos.: 7, 8, 9, 10, 11-22, 25-27, 39, 50, 51, 59, 76, 80-81, 92, 94, 95, 107, 120, 122, 123.g] Administrative Orders Nos.: 347, 348, 352-354, 360- 378, 380-433, 436-439.The respondents, through the Solicitor General, would have this case dismissed outright on the ground that petitioners have no legal personality or standing to bring the instant petition. The view is submitted that in the absence of any showing that petitioners are personally and directly affected or prejudiced by the alleged non-publication of the presidential issuances in question 2 said petitioners are without the requisite legal personality to institute this mandamus proceeding, they are not being "aggrieved parties" within the meaning of Section 3, Rule 65 of the Rules of Court, which we quote:SEC. 3. Petition for Mandamus.—When any tribunal, corporation, board or person unlawfully neglects the performance of an act which the law specifically enjoins as a duty resulting from an office, trust, or station, or unlawfully excludes another from the use a rd enjoyment of a right or office to which such other is entitled, and there is no other plain, speedy and adequate remedy in the ordinary course of law, the person aggrieved thereby may file a verified petition in the proper court alleging the facts with certainty and praying that judgment be rendered commanding the defendant, immediately or at some other specified time, to do the act required to be done to Protect the rights of the petitioner, and to pay the damages sustained by the petitioner by reason of the wrongful acts of the defendant.Upon the other hand, petitioners maintain that since the subject of the petition concerns a public right and its object is to compel the performance of a public duty, they need not show any specific interest for their petition to be given due course.

The issue posed is not one of first impression. As early as the 1910 case of Severino vs. Governor General, 3 this Court held that while the general rule is that "a writ of mandamus would be granted to a private individual only in those cases where he has some private or particular interest to be subserved, or some particular right to be protected, independent of that which he holds with the public at large," and "it is for the public officers exclusively to apply for the writ when public rights are to be subserved [Mithchell vs. Boardmen, 79 M.e., 469]," nevertheless, "when the question is one of public right and the object of the mandamus is to procure the enforcement of a public duty, the people are regarded as the real party in interest and the relator at whose instigation the proceedings are instituted need not show that he has any legal or special interest in the result, it being sufficient to show that he is a citizen and as such interested in the execution of the laws [High, Extraordinary Legal Remedies, 3rd ed., sec. 431].Thus, in said case, this Court recognized the relator Lope Severino, a private individual, as a proper party to the mandamus proceedings brought to compel the Governor General to call a special election for the position of municipal president in the town of Silay, Negros Occidental. Speaking for this Court, Mr. Justice Grant T. Trent said:We are therefore of the opinion that the weight of authority supports the proposition that the relator is a proper party to proceedings of this character when a public right is sought to be enforced. If the general rule in America were otherwise, we think that it would not be applicable to the case at bar for the reason 'that it is always dangerous to apply a general rule to a particular case without keeping in mind the reason for the rule, because, if under the particular circumstances the reason for the rule does not exist, the rule itself is not applicable and reliance upon the rule may well lead to error'No reason exists in the case at bar for applying the general rule insisted upon by counsel for the respondent. The circumstances which surround this case are different from those in the United States, inasmuch as if the relator is not a proper party to these proceedings no other person could be, as we have seen that it is not the duty of the law officer of the Government to appear and represent the people in cases of this character.The reasons given by the Court in recognizing a private citizen's legal personality in the aforementioned case apply squarely to the present petition. Clearly, the right sought to be enforced by petitioners herein is a public right recognized by no less than the fundamental law of the land. If petitioners were not allowed to institute this proceeding, it would indeed be difficult to conceive of any other person to initiate the same, considering

that the Solicitor General, the government officer generally empowered to represent the people, has entered his appearance for respondents in this case.Respondents further contend that publication in the Official Gazette is not a sine qua non requirement for the effectivity of laws where the laws themselves provide for their own effectivity dates. It is thus submitted that since the presidential issuances in question contain special provisions as to the date they are to take effect, publication in the Official Gazette is not indispensable for their effectivity. The point stressed is anchored on Article 2 of the Civil Code:Art. 2. Laws shall take effect after fifteen days following the completion of their publication in the Official Gazette, unless it is otherwise provided, ...The interpretation given by respondent is in accord with this Court's construction of said article. In a long line of decisions, 4 this Court has ruled that publication in the Official Gazette is necessary in those cases where the legislation itself does not provide for its effectivity date-for then the date of publication is material for determining its date of effectivity, which is the fifteenth day following its publication-but not when the law itself provides for the date when it goes into effect.Respondents' argument, however, is logically correct only insofar as it equates the effectivity of laws with the fact of publication. Considered in the light of other statutes applicable to the issue at hand, the conclusion is easily reached that said Article 2 does not preclude the requirement of publication in the Official Gazette, even if the law itself provides for the date of its effectivity. Thus, Section 1 of Commonwealth Act 638 provides as follows:Section 1. There shall be published in the Official Gazette [1] all important legisiative acts and resolutions of a public nature of the, Congress of the Philippines; [2] all executive and administrative orders and proclamations, except such as have no general applicability; [3] decisions or abstracts of decisions of the Supreme Court and the Court of Appeals as may be deemed by said courts of sufficient importance to be so published; [4] such documents or classes of documents as may be required so to be published by law; and [5] such documents or classes of documents as the President of the Philippines shall determine from time to time to have general applicability and legal effect, or which he may authorize so to be published. ...The clear object of the above-quoted provision is to give the general public adequate notice of the various laws which are to regulate their actions and conduct as citizens. Without such notice and publication, there would be no

basis for the application of the maxim "ignorantia legis non excusat." It would be the height of injustice to punish or otherwise burden a citizen for the transgression of a law of which he had no notice whatsoever, not even a constructive one.Perhaps at no time since the establishment of the Philippine Republic has the publication of laws taken so vital significance that at this time when the people have bestowed upon the President a power heretofore enjoyed solely by the legislature. While the people are kept abreast by the mass media of the debates and deliberations in the Batasan Pambansa—and for the diligent ones, ready access to the legislative records—no such publicity accompanies the law-making process of the President. Thus, without publication, the people have no means of knowing what presidential decrees have actually been promulgated, much less a definite way of informing themselves of the specific contents and texts of such decrees. As the Supreme Court of Spain ruled: "Bajo la denominacion generica de leyes, se comprenden tambien los reglamentos, Reales decretos, Instrucciones, Circulares y Reales ordines dictadas de conformidad con las mismas por el Gobierno en uso de su potestad. 5

The very first clause of Section I of Commonwealth Act 638 reads: "There shall be published in the Official Gazette ... ." The word "shall" used therein imposes upon respondent officials an imperative duty. That duty must be enforced if the Constitutional right of the people to be informed on matters of public concern is to be given substance and reality. The law itself makes a list of what should be published in the Official Gazette. Such listing, to our mind, leaves respondents with no discretion whatsoever as to what must be included or excluded from such publication.The publication of all presidential issuances "of a public nature" or "of general applicability" is mandated by law. Obviously, presidential decrees that provide for fines, forfeitures or penalties for their violation or otherwise impose a burden or. the people, such as tax and revenue measures, fall within this category. Other presidential issuances which apply only to particular persons or class of persons such as administrative and executive orders need not be published on the assumption that they have been circularized to all concerned. 6

It is needless to add that the publication of presidential issuances "of a public nature" or "of general applicability" is a requirement of due process. It is a rule of law that before a person may be bound by law, he must first be officially and specifically informed of its contents. As Justice Claudio Teehankee said in Peralta vs. COMELEC 7:

In a time of proliferating decrees, orders and letters of instructions which all form part of the law of the land, the requirement of due process and the Rule of Law demand that the Official Gazette as the official government repository promulgate and publish the texts of all such decrees, orders and instructions so that the people may know where to obtain their official and specific contents.The Court therefore declares that presidential issuances of general application, which have not been published, shall have no force and effect. Some members of the Court, quite apprehensive about the possible unsettling effect this decision might have on acts done in reliance of the validity of those presidential decrees which were published only during the pendency of this petition, have put the question as to whether the Court's declaration of invalidity apply to P.D.s which had been enforced or implemented prior to their publication. The answer is all too familiar. In similar situations in the past this Court had taken the pragmatic and realistic course set forth in Chicot County Drainage District vs. Baxter Bank 8 to wit:The courts below have proceeded on the theory that the Act of Congress, having been found to be unconstitutional, was not a law; that it was inoperative, conferring no rights and imposing no duties, and hence affording no basis for the challenged decree. Norton v. Shelby County, 118 U.S. 425, 442; Chicago, 1. & L. Ry. Co. v. Hackett, 228 U.S. 559, 566. It is quite clear, however, that such broad statements as to the effect of a determination of unconstitutionality must be taken with qualifications. The actual existence of a statute, prior to such a determination, is an operative fact and may have consequences which cannot justly be ignored. The past cannot always be erased by a new judicial declaration. The effect of the subsequent ruling as to invalidity may have to be considered in various aspects-with respect to particular conduct, private and official. Questions of rights claimed to have become vested, of status, of prior determinations deemed to have finality and acted upon accordingly, of public policy in the light of the nature both of the statute and of its previous application, demand examination. These questions are among the most difficult of those which have engaged the attention of courts, state and federal and it is manifest from numerous decisions that an all-inclusive statement of a principle of absolute retroactive invalidity cannot be justified.Consistently with the above principle, this Court in Rutter vs. Esteban 9

sustained the right of a party under the Moratorium Law, albeit said right had accrued in his favor before said law was declared unconstitutional by this Court.

Similarly, the implementation/enforcement of presidential decrees prior to their publication in the Official Gazette is "an operative fact which may have consequences which cannot be justly ignored. The past cannot always be erased by a new judicial declaration ... that an all-inclusive statement of a principle of absolute retroactive invalidity cannot be justified."From the report submitted to the Court by the Clerk of Court, it appears that of the presidential decrees sought by petitioners to be published in the Official Gazette, only Presidential Decrees Nos. 1019 to 1030, inclusive, 1278, and 1937 to 1939, inclusive, have not been so published. 10 Neither the subject matters nor the texts of these PDs can be ascertained since no copies thereof are available. But whatever their subject matter may be, it is undisputed that none of these unpublished PDs has ever been implemented or enforced by the government. In Pesigan vs. Angeles, 11 the Court, through Justice Ramon Aquino, ruled that "publication is necessary to apprise the public of the contents of [penal] regulations and make the said penalties binding on the persons affected thereby. " The cogency of this holding is apparently recognized by respondent officials considering the manifestation in their comment that "the government, as a matter of policy, refrains from prosecuting violations of criminal laws until the same shall have been published in the Official Gazette or in some other publication, even though some criminal laws provide that they shall take effect immediately. WHEREFORE, the Court hereby orders respondents to publish in the Official Gazette all unpublished presidential issuances which are of general application, and unless so published, they shall have no binding force and effect.SO ORDERED.

FIRST DIVISIONA.M. No. MTJ-00-1329 March 8, 2001(Formerly A.M. No. OCA IPI No. 99-706-MTJ)HERMINIA BORJA-MANZANO, petitioner, vs.JUDGE ROQUE R. SANCHEZ, MTC, Infanta, Pangasinan, respondent.R E S O L U T I O NDAVIDE, JR., C.J.:The solemnization of a marriage between two contracting parties who were both bound by a prior existing marriage is the bone of contention of the instant complaint against respondent Judge Roque R. Sanchez, Municipal Trial Court, Infanta, Pangasinan. For this act, complainant Herminia Borja-

Manzano charges respondent Judge with gross ignorance of the law in a sworn Complaint-Affidavit filed with the Office of the Court Administrator on 12 May 1999.Complainant avers that she was the lawful wife of the late David Manzano, having been married to him on 21 May 1966 in San Gabriel Archangel Parish, Araneta Avenue, Caloocan City.1 Four children were born out of that marriage.2 On 22 March 1993, however, her husband contracted another marriage with one Luzviminda Payao before respondent Judge.3 When respondent Judge solemnized said marriage, he knew or ought to know that the same was void and bigamous, as the marriage contract clearly stated that both contracting parties were "separated."Respondent Judge, on the other hand, claims in his Comment that when he officiated the marriage between Manzano and Payao he did not know that Manzano was legally married. What he knew was that the two had been living together as husband and wife for seven years already without the benefit of marriage, as manifested in their joint affidavit.4 According to him, had he known that the late Manzano was married, he would have advised the latter not to marry again; otherwise, he (Manzano) could be charged with bigamy. He then prayed that the complaint be dismissed for lack of merit and for being designed merely to harass him.After an evaluation of the Complaint and the Comment, the Court Administrator recommended that respondent Judge be found guilty of gross ignorance of the law and be ordered to pay a fine of P2,000, with a warning that a repetition of the same or similar act would be dealt with more severely.On 25 October 2000, this Court required the parties to manifest whether they were willing to submit the case for resolution on the basis of the pleadings thus filed. Complainant answered in the affirmative.For his part, respondent Judge filed a Manifestation reiterating his plea for the dismissal of the complaint and setting aside his earlier Comment. He therein invites the attention of the Court to two separate affidavits5 of the late Manzano and of Payao, which were allegedly unearthed by a member of his staff upon his instruction. In those affidavits, both David Manzano and Luzviminda Payao expressly stated that they were married to Herminia Borja and Domingo Relos, respectively; and that since their respective marriages had been marked by constant quarrels, they had both left their families and had never cohabited or communicated with their spouses anymore. Respondent Judge alleges that on the basis of those affidavits, he agreed to solemnize the marriage in question in accordance with Article 34 of the Family Code.

We find merit in the complaint.Article 34 of the Family Code provides:No license shall be necessary for the marriage of a man and a woman who have lived together as husband and wife for at least five years and without any legal impediment to marry each other. The contracting parties shall state the foregoing facts in an affidavit before any person authorized by law to administer oaths. The solemnizing officer shall also state under oath that he ascertained the qualifications of the contracting parties and found no legal impediment to the marriage.For this provision on legal ratification of marital cohabitation to apply, the following requisites must concur:1. The man and woman must have been living together as husband and wife for at least five years before the marriage;2. The parties must have no legal impediment to marry each other;3. The fact of absence of legal impediment between the parties must be present at the time of marriage;4. The parties must execute an affidavit stating that they have lived together for at least five years [and are without legal impediment to marry each other]; and5. The solemnizing officer must execute a sworn statement that he had ascertained the qualifications of the parties and that he had found no legal impediment to their marriage.6

Not all of these requirements are present in the case at bar. It is significant to note that in their separate affidavits executed on 22 March 1993 and sworn to before respondent Judge himself, David Manzano and Luzviminda Payao expressly stated the fact of their prior existing marriage. Also, in their marriage contract, it was indicated that both were "separated."Respondent Judge knew or ought to know that a subsisting previous marriage is a diriment impediment, which would make the subsequent marriage null and void.7 In fact, in his Comment, he stated that had he known that the late Manzano was married he would have discouraged him from contracting another marriage. And respondent Judge cannot deny knowledge of Manzano’s and Payao’s subsisting previous marriage, as the same was clearly stated in their separate affidavits which were subscribed and sworn to before him.The fact that Manzano and Payao had been living apart from their respective spouses for a long time already is immaterial. Article 63(1) of the Family Code allows spouses who have obtained a decree of legal separation to live separately from each other, but in such a case the marriage bonds are not severed. Elsewise stated, legal separation does not dissolve the

marriage tie, much less authorize the parties to remarry. This holds true all the more when the separation is merely de facto, as in the case at bar.Neither can respondent Judge take refuge on the Joint Affidavit of David Manzano and Luzviminda Payao stating that they had been cohabiting as husband and wife for seven years. Just like separation, free and voluntary cohabitation with another person for at least five years does not severe the tie of a subsisting previous marriage. Marital cohabitation for a long period of time between two individuals who are legally capacitated to marry each other is merely a ground for exemption from marriage license. It could not serve as a justification for respondent Judge to solemnize a subsequent marriage vitiated by the impediment of a prior existing marriage.Clearly, respondent Judge demonstrated gross ignorance of the law when he solemnized a void and bigamous marriage. The maxim "ignorance of the law excuses no one" has special application to judges,8 who, under Rule 1.01 of the Code of Judicial Conduct, should be the embodiment of competence, integrity, and independence. It is highly imperative that judges be conversant with the law and basic legal principles.9 And when the law transgressed is simple and elementary, the failure to know it constitutes gross ignorance of the law.10

ACCORDINGLY, the recommendation of the Court Administrator is hereby ADOPTED, with the MODIFICATION that the amount of fine to be imposed upon respondent Judge Roque Sanchez is increased to P20,000.SO ORDERED.A.M. No. MTJ-92-706 March 29, 1995LUPO ALMODIEL ATIENZA, complainant, vs.JUDGE FRANCISCO F. BRILLANTES, JR., Metropolitan Trial Court, Branch 28, Manila, respondent.QUIASON, J.:This is a complaint by Lupo A. Atienza for Gross Immorality and Appearance of Impropriety against Judge Francisco Brillantes, Jr., Presiding Judge of the Metropolitan Trial Court, Branch 20, Manila.Complainant alleges that he has two children with Yolanda De Castro, who are living together at No. 34 Galaxy Street, Bel-Air Subdivision, Makati, Metro Manila. He stays in said house, which he purchased in 1987, whenever he is in Manila.In December 1991, upon opening the door to his bedroom, he saw respondent sleeping on his (complainant's) bed. Upon inquiry, he was told by the houseboy that respondent had been cohabiting with De Castro.

Complainant did not bother to wake up respondent and instead left the house after giving instructions to his houseboy to take care of his children.Thereafter, respondent prevented him from visiting his children and even alienated the affection of his children for him.Complainant claims that respondent is married to one Zenaida Ongkiko with whom he has five children, as appearing in his 1986 and 1991 sworn statements of assets and liabilities. Furthermore, he alleges that respondent caused his arrest on January 13, 1992, after he had a heated argument with De Castro inside the latter's office.For his part, respondent alleges that complainant was not married to De Castro and that the filing of the administrative action was related to complainant's claim on the Bel-Air residence, which was disputed by De Castro.Respondent denies that he caused complainant's arrest and claims that he was even a witness to the withdrawal of the complaint for Grave Slander filed by De Castro against complainant. According to him, it was the sister of De Castro who called the police to arrest complainant.Respondent also denies having been married to Ongkiko, although he admits having five children with her. He alleges that while he and Ongkiko went through a marriage ceremony before a Nueva Ecija town mayor on April 25, 1965, the same was not a valid marriage for lack of a marriage license. Upon the request of the parents of Ongkiko, respondent went through another marriage ceremony with her in Manila on June 5, 1965. Again, neither party applied for a marriage license. Ongkiko abandoned respondent 17 years ago, leaving their children to his care and custody as a single parent.Respondent claims that when he married De Castro in civil rites in Los Angeles, California on December 4, 1991, he believed, in all good faith and for all legal intents and purposes, that he was single because his first marriage was solemnized without a license.Under the Family Code, there must be a judicial declaration of the nullity of a previous marriage before a party thereto can enter into a second marriage. Article 40 of said Code provides:The absolute nullity of a previous marriage may be invoked for the purposes of remarriage on the basis solely of a final judgment declaring such previous marriage void.Respondent argues that the provision of Article 40 of the Family Code does not apply to him considering that his first marriage took place in 1965 and was governed by the Civil Code of the Philippines; while the second marriage took place in 1991 and governed by the Family Code.

Article 40 is applicable to remarriages entered into after the effectivity of the Family Code on August 3, 1988 regardless of the date of the first marriage. Besides, under Article 256 of the Family Code, said Article is given "retroactive effect insofar as it does not prejudice or impair vested or acquired rights in accordance with the Civil Code or other laws." This is particularly true with Article 40, which is a rule of procedure. Respondent has not shown any vested right that was impaired by the application of Article 40 to his case.The fact that procedural statutes may somehow affect the litigants' rights may not preclude their retroactive application to pending actions. The retroactive application of procedural laws is not violative of any right of a person who may feel that he is adversely affected (Gregorio v. Court of Appeals, 26 SCRA 229 [1968]). The reason is that as a general rule no vested right may attach to, nor arise from, procedural laws (Billones v. Court of Industrial Relations, 14 SCRA 674 [1965]).Respondent is the last person allowed to invoke good faith. He made a mockery of the institution of marriage and employed deceit to be able to cohabit with a woman, who beget him five children.Respondent passed the Bar examinations in 1962 and was admitted to the practice of law in 1963. At the time he went through the two marriage ceremonies with Ongkiko, he was already a lawyer. Yet, he never secured any marriage license. Any law student would know that a marriage license is necessary before one can get married. Respondent was given an opportunity to correct the flaw in his first marriage when he and Ongkiko were married for the second time. His failure to secure a marriage license on these two occasions betrays his sinister motives and bad faith.It is evident that respondent failed to meet the standard of moral fitness for membership in the legal profession.While the deceit employed by respondent existed prior to his appointment as a Metropolitan Trial Judge, his immoral and illegal act of cohabiting with De Castro began and continued when he was already in the judiciary.The Code of Judicial Ethics mandates that the conduct of a judge must be free of a whiff of impropriety, not only with respect to his performance of his judicial duties but also as to his behavior as a private individual. There is no duality of morality. A public figure is also judged by his private life. A judge, in order to promote public confidence in the integrity and impartiality of the judiciary, must behave with propriety at all times, in the performance of his judicial duties and in his everyday life. These are judicial guideposts too self-evident to be overlooked. No position exacts a greater demand on

moral righteousness and uprightness of an individual than a seat in the judiciary (Imbing v. Tiongzon, 229 SCRA 690 [1994]).WHEREFORE, respondent is DISMISSED from the service with forfeiture of all leave and retirement benefits and with prejudice to reappointment in any branch, instrumentality, or agency of the government, including government-owned and controlled corporations. This decision is immediately executory.SO ORDERED.FIRST DIVISIONG.R. No. 133978 November 12, 2002JOSE S. CANCIO, JR., represented by ROBERTO L. CANCIO, petitioner, vs.EMERENCIANA ISIP, respondent.D E C I S I O NYNARES-SANTIAGO, J.:The instant petition for review under Rule 45 of the Rules of Court raises pure questions of law involving the March 20, 19981 and June 1, 19982

Orders3 rendered by the Regional Trial Court of Pampanga, Branch 49, in Civil Case No. G-3272.The undisputed facts are as follows:Petitioner, assisted by a private prosecutor, filed three cases of Violation of B.P. No. 22 and three cases of Estafa, against respondent for allegedly issuing the following checks without sufficient funds, to wit: 1) Interbank Check No. 25001151 in the amount of P80,000.00; 2) Interbank Check No. 25001152 in the amount of P 80,000.00; and 3) Interbank Check No. 25001157 in the amount of P30,000.00.4

The Office of the Provincial Prosecutor dismissed Criminal Case No. 13356, for Violation of B.P. No. 22 covering check no. 25001151 on the ground that the check was deposited with the drawee bank after 90 days from the date of the check. The two other cases for Violation of B.P. No. 22 (Criminal Case No. 13359 and 13360) were filed with and subsequently dismissed by the Municipal Trial Court of Guagua, Pampanga, Branch 1, on the ground of "failure to prosecute."5

Meanwhile, the three cases for Estafa were filed with the Regional Trial Court of Pampanga, Branch 49, and docketed as Criminal Case Nos. G-3611 to G-3613. On October 21, 1997, after failing to present its second witness, the prosecution moved to dismiss the estafa cases against respondent. The prosecution likewise reserved its right to file a separate civil action arising from the said criminal cases. On the same date, the trial court granted the motions of the prosecution. Thus-

Upon motion of the prosecution for the dismissal of these cases without prejudice to the refiling of the civil aspect thereof and there being no comment from the defense, let these cases be dismissed without prejudice to the refiling of the civil aspect of the cases.SO ORDER[ED].6

On December 15, 1997, petitioner filed the instant case for collection of sum of money, seeking to recover the amount of the checks subject of the estafa cases. On February 18, 1998, respondent filed a motion to dismiss the complaint contending that petitioner’s action is barred by the doctrine of res judicata. Respondent further prayed that petitioner should be held in contempt of court for forum-shopping.7

On March 20, 1998, the trial court found in favor of respondent and dismissed the complaint. The court held that the dismissal of the criminal cases against respondent on the ground of lack of interest or failure to prosecute is an adjudication on the merits which amounted to res judicata on the civil case for collection. It further held that the filing of said civil case amounted to forum-shopping.On June 1, 1998, the trial court denied petitioner’s motion for reconsideration.8 Hence, the instant petition.The legal issues for resolution in the case at bar are: 1) whether the dismissal of the estafa cases against respondent bars the institution of a civil action for collection of the value of the checks subject of the estafa cases; and 2) whether the filing of said civil action violated the anti-forum-shopping rule.An act or omission causing damage to another may give rise to two separate civil liabilities on the part of the offender, i.e., (1) civil liability ex delicto, under Article 100 of the Revised Penal Code;9 and (2) independent civil liabilities, such as those (a) not arising from an act or omission complained of as felony [e.g. culpa contractual or obligations arising from law under Article 3110 of the Civil Code,11 intentional torts under Articles 3212 and 34,13

and culpa aquiliana under Article 217614 of the Civil Code]; or (b) where the injured party is granted a right to file an action independent and distinct from the criminal action [Article 33,15 Civil Code].16 Either of these two possible liabilities may be enforced against the offender subject, however, to the caveat under Article 2177 of the Civil Code that the offended party "cannot recover damages twice for the same act or omission" or under both causes.17

The modes of enforcement of the foregoing civil liabilities are provided for in the Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure. Though the assailed order of the trial court was issued on March 20, 1998, the said Rules, which took effect

on December 1, 2000, must be given retroactive effect in the instant case considering that statutes regulating the procedure of the court are construed as applicable to actions pending and undetermined at the time of their passage.18

Section 1, Rule 111, of the Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure provides:SECTION 1. Institution of criminal and civil actions. – (a) When a criminal action is instituted, the civil action for the recovery of civil liability arising from the offense charged shall be deemed instituted with the criminal action unless the offended party waives the civil action, reserves the right to institute it separately or institutes the civil action prior to the criminal action.The reservation of the right to institute separately the civil action shall be made before the prosecution starts presenting its evidence and under circumstances affording the offended party a reasonable opportunity to make such reservation.x x x x x x x x xWhere the civil action has been filed separately and trial thereof has not yet commenced, it may be consolidated with the criminal action upon application with the court trying the latter case. If the application is granted, the trial of both actions shall proceed in accordance with section 2 of this Rule governing consolidation of the civil and criminal actions.Under the 1985 Rules on Criminal Procedure, as amended in 1988 and under the present Rules, the civil liability ex-delicto is deemed instituted with the criminal action, but the offended party is given the option to file a separate civil action before the prosecution starts to present evidence.19

Anent the independent civil actions under Articles 31, 32, 33, 34 and 2176 of the Civil Code, the old rules considered them impliedly instituted with the civil liability ex-delicto in the criminal action, unless the offended party waives the civil action, reserves his right to institute it separately, or institutes the civil action prior to the criminal action. Under the present Rules, however, the independent civil actions may be filed separately and prosecuted independently even without any reservation in the criminal action. The failure to make a reservation in the criminal action is not a waiver of the right to file a separate and independent civil action based on these articles of the Civil Code.20

In the case at bar, a reading of the complaint filed by petitioner show that his cause of action is based on culpa contractual, an independent civil action. Pertinent portion of the complaint reads:x x x x x x x x x

2. That plaintiff is the owner/proprietor to CANCIO’S MONEY EXCHANGE with office address at Guagua, Pampanga;3. That on several occasions, particularly on February 27, 1993 to April 17 1993, inclusive, defendant drew, issued and made in favor of the plaintiff the following checks:CHECK NO. DATE AMOUNT1. Interbank Check No. 25001151 March 10, 1993 P80,000.002. Interbank Check No. 25001152 March 27, 1993 P80,000.003. Interbank Check No. 25001157 May 17, 1993 P30,000.00in exchange of cash with the assurance that the said checks will be honored for payment on their maturity dates, copy of the aforementioned checks are hereto attached and marked.4. That when the said checks were presented to the drawee bank for encashment, the same were all dishonored for reason of DRAWN AGAINST INSUFFICIENT FUNDS (DAIF);5. That several demands were made upon the defendant to make good the checks but she failed and refused and still fails and refuses without justifiable reason to pay plaintiff;6. That for failure of the defendant without any justifiable reason to pay plaintiff the value of the checks, the latter was forced to hire the services of undersigned counsel and agreed to pay the amount of P30,000.00 as attorney’s fees and P1,000.00 per appearance in court;7. That for failure of the defendant without any justifiable reason to pay plaintiff and forcing the plaintiff to litigate, the latter will incur litigation expenses in the amount of P20,000.00.IN VIEW OF THE FOREGOING, it is prayed of this Court that after due notice and hearing a judgment be rendered ordering defendant to pay plaintiff as follows:a. the principal sum of P190,000.00 plus the legal interest;b. attorney’s fees of P30,000.00 plus P1,000.00 per court appearance;c. litigation expenses in the amount of P20,000.00PLAINTIFF prays for other reliefs just and equitable under the premises.x x x x x x x x x.21

Evidently, petitioner sought to enforce respondent’s obligation to make good the value of the checks in exchange for the cash he delivered to respondent. In other words, petitioner’s cause of action is the respondent’s breach of the contractual obligation. It matters not that petitioner claims his cause of action to be one based on delict.22 The nature of a cause of action is determined by the facts alleged in the complaint as constituting the cause of action. The purpose of an action or suit and the law to govern it is to be

determined not by the claim of the party filing the action, made in his argument or brief, but rather by the complaint itself, its allegations and prayer for relief.23

Neither does it matter that the civil action reserved in the October 21, 1997 order of the trial court was the civil action ex delicto. To reiterate, an independent civil action arising from contracts, as in the instant case, may be filed separately and prosecuted independently even without any reservation in the criminal action. Under Article 31 of the Civil Code "[w]hen the civil action is based on an obligation not arising from the act or omission complained of as a felony, [e.g. culpa contractual] such civil action may proceed independently of the criminal proceedings and regardless of the result of the latter." Thus, in Vitola, et al. v. Insular Bank of Asia and America,24 the Court, applying Article 31 of the Civil Code, held that a civil case seeking to recover the value of the goods subject of a Letter of Credit-Trust Receipt is a civil action ex contractu and not ex delicto. As such, it is distinct and independent from the estafa case filed against the offender and may proceed regardless of the result of the criminal proceedings.One of the elements of res judicata is identity of causes of action.25 In the instant case, it must be stressed that the action filed by petitioner is an independent civil action, which remains separate and distinct from any criminal prosecution based on the same act.26 Not being deemed instituted in the criminal action based on culpa criminal, a ruling on the culpability of the offender will have no bearing on said independent civil action based on an entirely different cause of action, i.e., culpa contractual.In the same vein, the filing of the collection case after the dismissal of the estafa cases against respondent did not amount to forum-shopping. The essence of forum-shopping is the filing of multiple suits involving the same parties for the same cause of action, either simultaneously or successively, to secure a favorable judgment. Although the cases filed by petitioner arose from the same act or omission of respondent, they are, however, based on different causes of action. The criminal cases for estafa are based on culpa criminal while the civil action for collection is anchored on culpa contractual. Moreover, there can be no forum-shopping in the instant case because the law expressly allows the filing of a separate civil action which can proceed independently of the criminal action.27

Clearly, therefore, the trial court erred in dismissing petitioner’s complaint for collection of the value of the checks issued by respondent. Being an independent civil action which is separate and distinct from any criminal prosecution and which require no prior reservation for its institution, the

doctrine of res judicata and forum-shopping will not operate to bar the same.WHEREFORE, in view of all the foregoing, the instant petition is GRANTED. The March 20, 1998 and June 1, 1998 Orders of the Regional Trial Court of Pampanga, Branch 49, in Civil Case No. G-3272 are REVERSED and SET ASIDE. The instant case is REMANDED to the trial court for further proceedings.SO ORDEREDFIRST DIVISIONG.R. No. 163707 September 15, 2006MICHAEL C. GUY, petitioner, vs.HON. COURT OF APPEALS, HON. SIXTO MARELLA, JR., Presiding Judge, RTC, Branch 138, Makati City and minors, KAREN DANES WEI and KAMILLE DANES WEI, represented by their mother, REMEDIOS OANES, respondents.D E C I S I O NYNARES-SANTIAGO, J.:This petition for review on certiorari assails the January 22, 2004 Decision1

of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. SP No. 79742, which affirmed the Orders dated July 21, 20002 and July 17, 20033 of the Regional Trial Court of Makati City, Branch 138 in SP Proc. Case No. 4549 denying petitioner's motion to dismiss; and its May 25, 2004 Resolution4 denying petitioner's motion for reconsideration.The facts are as follows:On June 13, 1997, private respondent-minors Karen Oanes Wei and Kamille Oanes Wei, represented by their mother Remedios Oanes (Remedios), filed a petition for letters of administration5 before the Regional Trial Court of Makati City, Branch 138. The case was docketed as Sp. Proc. No. 4549 and entitled Intestate Estate of Sima Wei (a.k.a. Rufino Guy Susim).Private respondents alleged that they are the duly acknowledged illegitimate children of Sima Wei, who died intestate in Makati City on October 29, 1992, leaving an estate valued at P10,000,000.00 consisting of real and personal properties. His known heirs are his surviving spouse Shirley Guy and children, Emy, Jeanne, Cristina, George and Michael, all surnamed Guy. Private respondents prayed for the appointment of a regular administrator for the orderly settlement of Sima Wei's estate. They likewise prayed that, in the meantime, petitioner Michael C. Guy, son of the decedent, be appointed as Special Administrator of the estate. Attached to private respondents' petition was a Certification Against Forum Shopping6

signed by their counsel, Atty. Sedfrey A. Ordoñez.

In his Comment/Opposition,7 petitioner prayed for the dismissal of the petition. He asserted that his deceased father left no debts and that his estate can be settled without securing letters of administration pursuant to Section 1, Rule 74 of the Rules of Court. He further argued that private respondents should have established their status as illegitimate children during the lifetime of Sima Wei pursuant to Article 175 of the Family Code. The other heirs of Sima Wei filed a Joint Motion to Dismiss8 on the ground that the certification against forum shopping should have been signed by private respondents and not their counsel. They contended that Remedios should have executed the certification on behalf of her minor daughters as mandated by Section 5, Rule 7 of the Rules of Court. In a Manifestation/Motion as Supplement to the Joint Motion to Dismiss,9

petitioner and his co-heirs alleged that private respondents' claim had been paid, waived, abandoned or otherwise extinguished by reason of Remedios' June 7, 1993 Release and Waiver of Claim stating that in exchange for the financial and educational assistance received from petitioner, Remedios and her minor children discharge the estate of Sima Wei from any and all liabilities.The Regional Trial Court denied the Joint Motion to Dismiss as well as the Supplemental Motion to Dismiss. It ruled that while the Release and Waiver of Claim was signed by Remedios, it had not been established that she was the duly constituted guardian of her minor daughters. Thus, no renunciation of right occurred. Applying a liberal application of the rules, the trial court also rejected petitioner's objections on the certification against forum shopping. Petitioner moved for reconsideration but was denied. He filed a petition for certiorari before the Court of Appeals which affirmed the orders of the Regional Trial Court in its assailed Decision dated January 22, 2004, the dispositive portion of which states:WHEREFORE, premises considered, the present petition is hereby DENIED DUE COURSE and accordingly DISMISSED, for lack of merit. Consequently, the assailed Orders dated July 21, 2000 and July 17, 2003 are hereby both AFFIRMED. Respondent Judge is hereby DIRECTED to resolve the controversy over the illegitimate filiation of the private respondents (sic) minors [-] Karen Oanes Wei and Kamille Oanes Wei who are claiming successional rights in the intestate estate of the deceased Sima Wei, a.k.a. Rufino Guy Susim.SO ORDERED.10

The Court of Appeals denied petitioner's motion for reconsideration, hence, this petition.

Petitioner argues that the Court of Appeals disregarded existing rules on certification against forum shopping; that the Release and Waiver of Claim executed by Remedios released and discharged the Guy family and the estate of Sima Wei from any claims or liabilities; and that private respondents do not have the legal personality to institute the petition for letters of administration as they failed to prove their filiation during the lifetime of Sima Wei in accordance with Article 175 of the Family Code. Private respondents contend that their counsel's certification can be considered substantial compliance with the rules on certification of non-forum shopping, and that the petition raises no new issues to warrant the reversal of the decisions of the Regional Trial Court and the Court of Appeals.The issues for resolution are: 1) whether private respondents' petition should be dismissed for failure to comply with the rules on certification of non-forum shopping; 2) whether the Release and Waiver of Claim precludes private respondents from claiming their successional rights; and 3) whether private respondents are barred by prescription from proving their filiation.The petition lacks merit. Rule 7, Section 5 of the Rules of Court provides that the certification of non-forum shopping should be executed by the plaintiff or the principal party. Failure to comply with the requirement shall be cause for dismissal of the case. However, a liberal application of the rules is proper where the higher interest of justice would be served. In Sy Chin v. Court of Appeals,11 we ruled that while a petition may have been flawed where the certificate of non-forum shopping was signed only by counsel and not by the party, this procedural lapse may be overlooked in the interest of substantial justice. 12

So it is in the present controversy where the merits13 of the case and the absence of an intention to violate the rules with impunity should be considered as compelling reasons to temper the strict application of the rules.As regards Remedios' Release and Waiver of Claim, the same does not bar private respondents from claiming successional rights. To be valid and effective, a waiver must be couched in clear and unequivocal terms which leave no doubt as to the intention of a party to give up a right or benefit which legally pertains to him. A waiver may not be attributed to a person when its terms do not explicitly and clearly evince an intent to abandon a right.14

In this case, we find that there was no waiver of hereditary rights. The Release and Waiver of Claim does not state with clarity the purpose of its execution. It merely states that Remedios received P300,000.00 and an

educational plan for her minor daughters "by way of financial assistance and in full settlement of any and all claims of whatsoever nature and kind x x x against the estate of the late Rufino Guy Susim."15 Considering that the document did not specifically mention private respondents' hereditary share in the estate of Sima Wei, it cannot be construed as a waiver of successional rights. Moreover, even assuming that Remedios truly waived the hereditary rights of private respondents, such waiver will not bar the latter's claim. Article 1044 of the Civil Code, provides:ART. 1044. Any person having the free disposal of his property may accept or repudiate an inheritance.Any inheritance left to minors or incapacitated persons may be accepted by their parents or guardians. Parents or guardians may repudiate the inheritance left to their wards only by judicial authorization.The right to accept an inheritance left to the poor shall belong to the persons designated by the testator to determine the beneficiaries and distribute the property, or in their default, to those mentioned in Article 1030. (Emphasis supplied)Parents and guardians may not therefore repudiate the inheritance of their wards without judicial approval. This is because repudiation amounts to an alienation of property16 which must pass the court's scrutiny in order to protect the interest of the ward. Not having been judicially authorized, the Release and Waiver of Claim in the instant case is void and will not bar private respondents from asserting their rights as heirs of the deceased.Furthermore, it must be emphasized that waiver is the intentional relinquishment of a known right. Where one lacks knowledge of a right, there is no basis upon which waiver of it can rest. Ignorance of a material fact negates waiver, and waiver cannot be established by a consent given under a mistake or misapprehension of fact.17 In the present case, private respondents could not have possibly waived their successional rights because they are yet to prove their status as acknowledged illegitimate children of the deceased. Petitioner himself has consistently denied that private respondents are his co-heirs. It would thus be inconsistent to rule that they waived their hereditary rights when petitioner claims that they do not have such right. Hence, petitioner's invocation of waiver on the part of private respondents must fail.Anent the issue on private respondents' filiation, we agree with the Court of Appeals that a ruling on the same would be premature considering that private respondents have yet to present evidence. Before the Family Code

took effect, the governing law on actions for recognition of illegitimate children was Article 285 of the Civil Code, to wit: ART. 285. The action for the recognition of natural children may be brought only during the lifetime of the presumed parents, except in the following cases:(1) If the father or mother died during the minority of the child, in which case the latter may file the action before the expiration of four years from the attainment of his majority;(2) If after the death of the father or of the mother a document should appear of which nothing had been heard and in which either or both parents recognize the child.In this case, the action must be commenced within four years from the finding of the document. (Emphasis supplied)We ruled in Bernabe v. Alejo18 that illegitimate children who were still minors at the time the Family Code took effect and whose putative parent died during their minority are given the right to seek recognition for a period of up to four years from attaining majority age. This vested right was not impaired or taken away by the passage of the Family Code.19 On the other hand, Articles 172, 173 and 175 of the Family Code, which superseded Article 285 of the Civil Code, provide: ART. 172. The filiation of legitimate children is established by any of the following:(1) The record of birth appearing in the civil register or a final judgment; or(2) An admission of legitimate filiation in a public document or a private handwritten instrument and signed by the parent concerned.In the absence of the foregoing evidence, the legitimate filiation shall be proved by:(1) The open and continuous possession of the status of a legitimate child; or(2) Any other means allowed by the Rules of Court and special laws.ART. 173. The action to claim legitimacy may be brought by the child during his or her lifetime and shall be transmitted to the heirs should the child die during minority or in a state of insanity. In these cases, the heirs shall have a period of five years within which to institute the action.The action already commenced by the child shall survive notwithstanding the death of either or both of the parties.ART. 175. Illegitimate children may establish their illegitimate filiation in the same way and on the same, evidence as legitimate children.The action must be brought within the same period specified in Article 173, except when the action is based on the second paragraph of Article 172, in

which case the action may be brought during the lifetime of the alleged parent. Under the Family Code, when filiation of an illegitimate child is established by a record of birth appearing in the civil register or a final judgment, or an admission of filiation in a public document or a private handwritten instrument signed by the parent concerned, the action for recognition may be brought by the child during his or her lifetime. However, if the action is based upon open and continuous possession of the status of an illegitimate child, or any other means allowed by the rules or special laws, it may only be brought during the lifetime of the alleged parent. It is clear therefore that the resolution of the issue of prescription depends on the type of evidence to be adduced by private respondents in proving their filiation. However, it would be impossible to determine the same in this case as there has been no reception of evidence yet. This Court is not a trier of facts. Such matters may be resolved only by the Regional Trial Court after a full-blown trial. While the original action filed by private respondents was a petition for letters of administration, the trial court is not precluded from receiving evidence on private respondents' filiation. Its jurisdiction extends to matters incidental and collateral to the exercise of its recognized powers in handling the settlement of the estate, including the determination of the status of each heir.20 That the two causes of action, one to compel recognition and the other to claim inheritance, may be joined in one complaint is not new in our jurisprudence.21 As held in Briz v. Briz:22

The question whether a person in the position of the present plaintiff can in any event maintain a complex action to compel recognition as a natural child and at the same time to obtain ulterior relief in the character of heir, is one which in the opinion of this court must be answered in the affirmative, provided always that the conditions justifying the joinder of the two distinct causes of action are present in the particular case. In other words, there is no absolute necessity requiring that the action to compel acknowledgment should have been instituted and prosecuted to a successful conclusion prior to the action in which that same plaintiff seeks additional relief in the character of heir. Certainly, there is nothing so peculiar to the action to compel acknowledgment as to require that a rule should be here applied different from that generally applicable in other cases. x x xThe conclusion above stated, though not heretofore explicitly formulated by this court, is undoubtedly to some extent supported by our prior decisions. Thus, we have held in numerous cases, and the doctrine must be considered well settled, that a natural child having a right to compel acknowledgment,

but who has not been in fact acknowledged, may maintain partition proceedings for the division of the inheritance against his coheirs (Siguiong vs. Siguiong, 8 Phil., 5; Tiamson vs. Tiamson, 32 Phil., 62); and the same person may intervene in proceedings for the distribution of the estate of his deceased natural father, or mother (Capistrano vs. Fabella, 8 Phil., 135; Conde vs. Abaya, 13 Phil., 249; Ramirez vs. Gmur, 42 Phil., 855). In neither of these situations has it been thought necessary for the plaintiff to show a prior decree compelling acknowledgment. The obvious reason is that in partition suits and distribution proceedings the other persons who might take by inheritance are before the court; and the declaration of heirship is appropriate to such proceedings.WHEREFORE, the instant petition is DENIED. The Decision dated January 22, 2004 of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. SP No. 79742 affirming the denial of petitioner's motion to dismiss; and its Resolution dated May 25, 2004 denying petitioner's motion for reconsideration, are AFFIRMED. Let the records be REMANDED to the Regional Trial Court of Makati City, Branch 138 for further proceedings.SO ORDERED.FIRST DIVISIONG.R. No. 174689 October 22, 2007ROMMEL JACINTO DANTES SILVERIO, petitioner, vs.REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES, respondent.D E C I S I O NCORONA, J.:When God created man, He made him in the likeness of God; He created them male and female. (Genesis 5:1-2)Amihan gazed upon the bamboo reed planted by Bathala and she heard voices coming from inside the bamboo. "Oh North Wind! North Wind! Please let us out!," the voices said. She pecked the reed once, then twice. All of a sudden, the bamboo cracked and slit open. Out came two human beings; one was a male and the other was a female. Amihan named the man "Malakas" (Strong) and the woman "Maganda" (Beautiful). (The Legend of Malakas and Maganda)When is a man a man and when is a woman a woman? In particular, does the law recognize the changes made by a physician using scalpel, drugs and counseling with regard to a person’s sex? May a person successfully petition for a change of name and sex appearing in the birth certificate to reflect the result of a sex reassignment surgery?

On November 26, 2002, petitioner Rommel Jacinto Dantes Silverio filed a petition for the change of his first name and sex in his birth certificate in the Regional Trial Court of Manila, Branch 8. The petition, docketed as SP Case No. 02-105207, impleaded the civil registrar of Manila as respondent.Petitioner alleged in his petition that he was born in the City of Manila to the spouses Melecio Petines Silverio and Anita Aquino Dantes on April 4, 1962. His name was registered as "Rommel Jacinto Dantes Silverio" in his certificate of live birth (birth certificate). His sex was registered as "male."He further alleged that he is a male transsexual, that is, "anatomically male but feels, thinks and acts as a female" and that he had always identified himself with girls since childhood.1 Feeling trapped in a man’s body, he consulted several doctors in the United States. He underwent psychological examination, hormone treatment and breast augmentation. His attempts to transform himself to a "woman" culminated on January 27, 2001 when he underwent sex reassignment surgery2 in Bangkok, Thailand. He was thereafter examined by Dr. Marcelino Reysio-Cruz, Jr., a plastic and reconstruction surgeon in the Philippines, who issued a medical certificate attesting that he (petitioner) had in fact undergone the procedure.From then on, petitioner lived as a female and was in fact engaged to be married. He then sought to have his name in his birth certificate changed from "Rommel Jacinto" to "Mely," and his sex from "male" to "female."An order setting the case for initial hearing was published in the People’s Journal Tonight, a newspaper of general circulation in Metro Manila, for three consecutive weeks.3 Copies of the order were sent to the Office of the Solicitor General (OSG) and the civil registrar of Manila.On the scheduled initial hearing, jurisdictional requirements were established. No opposition to the petition was made.During trial, petitioner testified for himself. He also presented Dr. Reysio-Cruz, Jr. and his American fiancé, Richard P. Edel, as witnesses.On June 4, 2003, the trial court rendered a decision4 in favor of petitioner. Its relevant portions read:Petitioner filed the present petition not to evade any law or judgment or any infraction thereof or for any unlawful motive but solely for the purpose of making his birth records compatible with his present sex.The sole issue here is whether or not petitioner is entitled to the relief asked for.The [c]ourt rules in the affirmative. Firstly, the [c]ourt is of the opinion that granting the petition would be more in consonance with the principles of justice and equity. With his sexual [re-assignment], petitioner, who has always felt, thought and acted like a

woman, now possesses the physique of a female. Petitioner’s misfortune to be trapped in a man’s body is not his own doing and should not be in any way taken against him.Likewise, the [c]ourt believes that no harm, injury [or] prejudice will be caused to anybody or the community in granting the petition. On the contrary, granting the petition would bring the much-awaited happiness on the part of the petitioner and her [fiancé] and the realization of their dreams.Finally, no evidence was presented to show any cause or ground to deny the present petition despite due notice and publication thereof. Even the State, through the [OSG] has not seen fit to interpose any [o]pposition.WHEREFORE, judgment is hereby rendered GRANTING the petition and ordering the Civil Registrar of Manila to change the entries appearing in the Certificate of Birth of [p]etitioner, specifically for petitioner’s first name from "Rommel Jacinto" to MELY and petitioner’s gender from "Male" to FEMALE. 5

On August 18, 2003, the Republic of the Philippines (Republic), thru the OSG, filed a petition for certiorari in the Court of Appeals. 6 It alleged that there is no law allowing the change of entries in the birth certificate by reason of sex alteration.On February 23, 2006, the Court of Appeals7 rendered a decision8 in favor of the Republic. It ruled that the trial court’s decision lacked legal basis. There is no law allowing the change of either name or sex in the certificate of birth on the ground of sex reassignment through surgery. Thus, the Court of Appeals granted the Republic’s petition, set aside the decision of the trial court and ordered the dismissal of SP Case No. 02-105207. Petitioner moved for reconsideration but it was denied.9 Hence, this petition.Petitioner essentially claims that the change of his name and sex in his birth certificate is allowed under Articles 407 to 413 of the Civil Code, Rules 103 and 108 of the Rules of Court and RA 9048.10 The petition lacks merit.A Person’s First Name Cannot Be Changed On the Ground of Sex ReassignmentPetitioner invoked his sex reassignment as the ground for his petition for change of name and sex. As found by the trial court:Petitioner filed the present petition not to evade any law or judgment or any infraction thereof or for any unlawful motive but solely for the purpose of making his birth records compatible with his present sex. (emphasis supplied)

Petitioner believes that after having acquired the physical features of a female, he became entitled to the civil registry changes sought. We disagree.The State has an interest in the names borne by individuals and entities for purposes of identification.11 A change of name is a privilege, not a right.12

Petitions for change of name are controlled by statutes.13 In this connection, Article 376 of the Civil Code provides:ART. 376. No person can change his name or surname without judicial authority.This Civil Code provision was amended by RA 9048 (Clerical Error Law). In particular, Section 1 of RA 9048 provides:SECTION 1. Authority to Correct Clerical or Typographical Error and Change of First Name or Nickname. – No entry in a civil register shall be changed or corrected without a judicial order, except for clerical or typographical errors and change of first name or nickname which can be corrected or changed by the concerned city or municipal civil registrar or consul general in accordance with the provisions of this Act and its implementing rules and regulations.RA 9048 now governs the change of first name.14 It vests the power and authority to entertain petitions for change of first name to the city or municipal civil registrar or consul general concerned. Under the law, therefore, jurisdiction over applications for change of first name is now primarily lodged with the aforementioned administrative officers. The intent and effect of the law is to exclude the change of first name from the coverage of Rules 103 (Change of Name) and 108 (Cancellation or Correction of Entries in the Civil Registry) of the Rules of Court, until and unless an administrative petition for change of name is first filed and subsequently denied.15 It likewise lays down the corresponding venue,16

form17 and procedure. In sum, the remedy and the proceedings regulating change of first name are primarily administrative in nature, not judicial.RA 9048 likewise provides the grounds for which change of first name may be allowed:SECTION 4. Grounds for Change of First Name or Nickname. – The petition for change of first name or nickname may be allowed in any of the following cases:(1) The petitioner finds the first name or nickname to be ridiculous, tainted with dishonor or extremely difficult to write or pronounce;(2) The new first name or nickname has been habitually and continuously used by the petitioner and he has been publicly known by that first name or nickname in the community; or

(3) The change will avoid confusion.Petitioner’s basis in praying for the change of his first name was his sex reassignment. He intended to make his first name compatible with the sex he thought he transformed himself into through surgery. However, a change of name does not alter one’s legal capacity or civil status.18 RA 9048 does not sanction a change of first name on the ground of sex reassignment. Rather than avoiding confusion, changing petitioner’s first name for his declared purpose may only create grave complications in the civil registry and the public interest.Before a person can legally change his given name, he must present proper or reasonable cause or any compelling reason justifying such change.19 In addition, he must show that he will be prejudiced by the use of his true and official name.20 In this case, he failed to show, or even allege, any prejudice that he might suffer as a result of using his true and official name.In sum, the petition in the trial court in so far as it prayed for the change of petitioner’s first name was not within that court’s primary jurisdiction as the petition should have been filed with the local civil registrar concerned, assuming it could be legally done. It was an improper remedy because the proper remedy was administrative, that is, that provided under RA 9048. It was also filed in the wrong venue as the proper venue was in the Office of the Civil Registrar of Manila where his birth certificate is kept. More importantly, it had no merit since the use of his true and official name does not prejudice him at all. For all these reasons, the Court of Appeals correctly dismissed petitioner’s petition in so far as the change of his first name was concerned.No Law Allows The Change of Entry In The Birth Certificate As To Sex On the Ground of Sex ReassignmentThe determination of a person’s sex appearing in his birth certificate is a legal issue and the court must look to the statutes.21 In this connection, Article 412 of the Civil Code provides:ART. 412. No entry in the civil register shall be changed or corrected without a judicial order.Together with Article 376 of the Civil Code, this provision was amended by RA 9048 in so far as clerical or typographical errors are involved. The correction or change of such matters can now be made through administrative proceedings and without the need for a judicial order. In effect, RA 9048 removed from the ambit of Rule 108 of the Rules of Court the correction of such errors.22 Rule 108 now applies only to substantial changes and corrections in entries in the civil register.23

Section 2(c) of RA 9048 defines what a "clerical or typographical error" is:

SECTION 2. Definition of Terms. – As used in this Act, the following terms shall mean:xxx xxx xxx(3) "Clerical or typographical error" refers to a mistake committed in the performance of clerical work in writing, copying, transcribing or typing an entry in the civil register that is harmless and innocuous, such as misspelled name or misspelled place of birth or the like, which is visible to the eyes or obvious to the understanding, and can be corrected or changed only by reference to other existing record or records: Provided, however, That no correction must involve the change of nationality, age, status or sex of the petitioner. (emphasis supplied)Under RA 9048, a correction in the civil registry involving the change of sex is not a mere clerical or typographical error. It is a substantial change for which the applicable procedure is Rule 108 of the Rules of Court.The entries envisaged in Article 412 of the Civil Code and correctable under Rule 108 of the Rules of Court are those provided in Articles 407 and 408 of the Civil Code:24

ART. 407. Acts, events and judicial decrees concerning the civil status of persons shall be recorded in the civil register.ART. 408. The following shall be entered in the civil register:(1) Births; (2) marriages; (3) deaths; (4) legal separations; (5) annulments of marriage; (6) judgments declaring marriages void from the beginning; (7) legitimations; (8) adoptions; (9) acknowledgments of natural children; (10) naturalization; (11) loss, or (12) recovery of citizenship; (13) civil interdiction; (14) judicial determination of filiation; (15) voluntary emancipation of a minor; and (16) changes of name.The acts, events or factual errors contemplated under Article 407 of the Civil Code include even those that occur after birth.25 However, no reasonable interpretation of the provision can justify the conclusion that it covers the correction on the ground of sex reassignment.To correct simply means "to make or set aright; to remove the faults or error from" while to change means "to replace something with something else of the same kind or with something that serves as a substitute."26 The birth certificate of petitioner contained no error. All entries therein, including those corresponding to his first name and sex, were all correct. No correction is necessary.Article 407 of the Civil Code authorizes the entry in the civil registry of certain acts (such as legitimations, acknowledgments of illegitimate children and naturalization), events (such as births, marriages, naturalization and deaths) and judicial decrees (such as legal separations, annulments of