1 Portraits and Exhibitions of “Pious Negroes” and “White Negroes” in the Eighteenth Century. Science, Arts and Entertainment revolving around the Other. Paola Martínez Pestana Let us begin with an image from 1658: the female ourang outang portrayed by Jacob Bontius, Dutch physician and explorer, in his Historiae naturalis (fig. 1). Bontius’ illustration depict s a fully upright female. He also describes her captivating modesty as she tries to cover her private parts under the watchful gaze of the male who is observing her in situ 1 . Her behaviour differs greatly from the male of the species, which is much more brutish in its ways. The face is highly humanised, with pleasant features. She is thought to be an albino because of the fair hair covering her entire body, and has a woman’s pubis and pudendal cleft. This is a time when the animal and the human – with all the radical distinction of mechanistic, Cartesian modernity – are becoming confused. In this particular case, it seems that the author, through the ourang outang’s demure and bashful appearance, combined with a certain delicacy, wants to capture a universal female trait, as noted by Londa Schiebinger 2 : modesty. At the same time, it is worth noting that this drawing is not restricted by prudishness, and reveals all – breasts and pubis – to make it quite clear that this is a female. In addition to studying medicine, Bontius was also an Arts graduate, a common feature of scientist-explorers. Edward Tyson was another Arts graduate with a doctorate in Medicine from the same century. In 1698, he dissected a chimpanzee, publishing his results in his Orang-Outang, sive Homo Sylvestris: or, the Anatomy of a Pygmie 1 Jacob BONTIUS, Historiae naturalis & medicae Indiae Orientalis libri sex, Amsterdam: 1658, p. 85. 2 Londa SCHIEBINGER, Natures’s Body, Gender in the Making of Modern Science, New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2006.

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

1

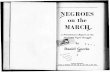

Portraits and Exhibitions of “Pious Negroes” and “White Negroes” in the

Eighteenth Century. Science, Arts and Entertainment revolving around the Other.

Paola Martínez Pestana

Let us begin with an image from 1658: the female ourang outang portrayed by

Jacob Bontius, Dutch physician and explorer, in his Historiae naturalis (fig. 1).

Bontius’ illustration depicts a fully upright female. He also describes her captivating

modesty as she tries to cover her private parts under the watchful gaze of the male who

is observing her in situ1. Her behaviour differs greatly from the male of the species,

which is much more brutish in its ways. The face is highly humanised, with pleasant

features. She is thought to be an albino because of the fair hair covering her entire body,

and has a woman’s pubis and pudendal cleft. This is a time when the animal and the

human – with all the radical distinction of mechanistic, Cartesian modernity – are

becoming confused. In this particular case, it seems that the author, through the ourang

outang’s demure and bashful appearance, combined with a certain delicacy, wants to

capture a universal female trait, as noted by Londa Schiebinger2: modesty. At the same

time, it is worth noting that this drawing is not restricted by prudishness, and reveals all

– breasts and pubis – to make it quite clear that this is a female.

In addition to studying medicine, Bontius was also an Arts graduate, a common

feature of scientist-explorers. Edward Tyson was another Arts graduate with a doctorate

in Medicine from the same century. In 1698, he dissected a chimpanzee, publishing his

results in his Orang-Outang, sive Homo Sylvestris: or, the Anatomy of a Pygmie

1 Jacob BONTIUS, Historiae naturalis & medicae Indiae Orientalis libri sex, Amsterdam: 1658,

p. 85. 2 Londa SCHIEBINGER, Natures’s Body, Gender in the Making of Modern Science, New

Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2006.

2

Compared with that of a Monkey, an Ape, and a Man3. In this famous text, the barriers

between animals and humans begin to fade. The orang outang is homo silvestris, as

classified by Linnaeus, identified in turn with what Tyson called a chimpanzee.

Dissection, and especially analysis of the brain, led him to conclude that this wild lady,

orang outang or chimpanzee, had much more in common with humans than with large

or small monkeys, which were much more primitive species. Perhaps that is why, when

copying Bontius’ illustration, Tyson showed the courtesy of covering the wild female’s

pubis with a leaf, as if she were Albrecht Dürer’s Eve (fig. 2). And if we compare the

two, it is the wild albino female who covers herself with a leaf; Eve had not yet acquired

“female” modesty (fig. 3a).

We may also show another female albino ourang outing. This time she has an

entirely different physiognomy and is domesticated (fig. 3b). We are, by now, in the

eighteenth century, having jumped a long way forward to 1794, and we can see the

extent to which scholars divined a closeness between these beings and humans. She is

wielding an axe to kill a bird which resembles a cockerel. She uses tools well, according

to Ebenezer Sibly’s extensive 1794 study, An Universal History of Natural History:

Including the Natural History of Man.

These illustrations were drawn in the East Indies and were already the source of

great fascination in Europe. Travel books “are in our present days what books of

chivalry were in those of our forefathers” wrote the Earl of Shaftesbury in 17104. The

aspiration to truthfulness in these studies was now greater, as may be seen with Tyson

3 Edward TYSON, Orang-Outang, sive Homo Sylvestris: or, the Anatomy of a Pygmie Compared

with that of a Monkey, an Ape, and a Man, London, 1699, fig. 16. 4 Anthony Ashley Cooper, 3rd Earl of SHAFTESBURY (1710), quoted by Juan PIMENTEL in

Testigos del mundo. Ciencia, literatura y viajes en la Ilustración, Madrid: Marcial Pons

Historia, 2003, 215.

3

and other travellers; and yet they were still adventures, real adventures, containing

wonders to fire the imagination, which produced major bestsellers. “The travel book

was cultivated, written and read in the eighteenth century as never before” wrote Juan

Pimentel, and its readers thus obtained the honour of becoming “citizens of the world” 5.

However, in the Enlightenment, and especially in the mid-eighteenth century,

the colonial powers seemed to want more. The Age of Enlightenment illuminated the

night, and the people developed an appetite for seeing the exotic close-up, seeing it with

their own eyes (too many were still illiterate). The Court wished to flaunt its wealth

from beyond the seas, and explorers and natural philosophers served it up to them on a

silver platter, because they also wanted to show off their treasure troves: their cabinets

of curiosities.

Let us now journey to Paris in 1743, a Saturday in the Académie Royale des

Sciences, located at that time in the Louvre, and let us then visit the Hôtel de Bretagne,

in case, like the Comte de Buffon, anyone was late for the first appointment. There, on

display, was a four-year-old boy, a “white negro” – or albino as, according to Voltaire

and Blumenbach, the Spanish called them – born in a place called Maconde (apparently

near the Congo)6, and the son of black-skinned parents and ancestors. He was exhibited

in an intimate gathering of a few scholars, savants, and men of letters: Maupertuis,

Jussieu, Réaumur, Fontenelle, Buffon... and, of course, Voltaire.

There is no visual representation of this quite singular moment in those Paris

salons, although much was written about the event. But we can show the cabinet of the

5 Juan PIMENTEL, ibid., pp. 216-218. 6 In some works of literary criticism he is said to come from America, but we shall refer to the

primary literature of MAUPERTUIS and VOLTAIRE.

4

Académie Royale – the setting in which this albino child was exhibited – and so instead

we will have to make do with Louis XIV visiting the room (fig. 4).

The privilege of being one of a select coterie to witness a “white negro” resulted

in what is, for historians of the life sciences, an eighteenth-century classic: Maupertuis’

Vénus Physique (1745). In this seminal work on embryology, the author defended

epigenesis in the formation of the foetus against traditional preformation theories,

according to which the animal was already found in the sperm or the egg in the form it

would take when born, with the very same features in miniature.

The title of the work, “physical Venus” alluded to a totally different, materialist

notion of what was happening in the body of a pregnant woman. Maupertuis rejected

any kind of preformation, any divine or teleological design in the embryo. Instead he

gave us a pagan Venus, arbitrary, symbol of limitless fertility, whose very nature gave

free reign to every possible whim. “White negroes” could be born of “negro” parents

and ancestors. So, in a rather libertine style, typical of the materialists of his time,

Maupertuis considered the interaction of both sperm and egg in the womb, unlike the

preformationists, who only considered male or female action, depending on the author.

Moreover, and quite significantly, Maupertuis also took into account other physical and

chemical material accidents in the womb; note that he also believed in the agency of the

mother’s own imagination on the foetus, as we shall see below.

We should also note that this same work, virtually unaltered, had been named

Dissertation Physique à l’occasion du Nègre Blanc by the same author a year earlier

(1744)7. In Vénus Physique his concern throughout the text was also the “white

7 P.-L.M. de MAUPERTUIS (1744), Dissertation physique a l’occasion du Nègre Blanc,

Leyden. The edition was expanded in 1745 under the name Vénus physique, with very little

change in its approach.

5

negroes”, as a great example of the accidents or whims of Nature, to explain the

phenomenon of embryology in general and to defend epigenesis, as well the accident

and chance linked to it. How otherwise could a child with snow-white skin come from

totally black ancestors?

Voltaire, for his part, did not even see a human child in those salons, but a

different and bizarre animal whose species, he supposed, were quite normal inhabitants

of central Africa8. We should not for this reason accuse him of being an Eurocentric of

the worst sort. At that time almost everyone was. Similarly, the positions of Maupertuis

and Buffon could be considered hierarchising as they saw these persons’ pale skin as a

return to the origin of the “natural” human being: the “white” man9. According to these

authors, the black man was a degeneration that needed to revert back to the original

white man, natural man, and this albino was proof of this, along with the pious negroes,

as we shall see. Moreover, human or animal, Voltaire, Maupertuis and Buffon coincided

in descriptions that reduced them to brutish caricature: they all spoke of wool instead of

hair, and Voltaire himself said he could prove, using Newton’s optics, that they do not

see like us and that they have eyes like a mule or a goat, and can look both left and right

at the same time.

The whiteness of their skin was, in one way, a blessing in that it was not

considered to have the toughness and resilience for work that was often attributed to

people with black skin10

. In fact, “the white negro” could not be used for forced labour,

since they could barely leave the enclosure without catching skin and eye diseases.

8 VOLTAIRE, Relation touchant un maure blanc amené d’Afrique à Paris en 1744, 1745.

9 G.-L Leclerc, Comte de BUFFON, Histoire naturelle, générale et particulière: avec la

description du cabinet du roi (1749-1788), vol. IV, pp. 381-382, Paris: Imprimerie Royale,

1749. 10 Charles WHITE (1799), in Milton CANTOR “The image of the negro in colonial literature”, The

New England Quarterly, 36 (4), p. 467.

6

Perhaps that is why they were used more as pages, as was the case of Benedetto Silva,

from Angola, first portrayed in his natural condition and environment, but without the

painter, Antonio Franchi, having to leave Italy, and later being baptised in the chamber

of Grand Duke Cosimo III of Tuscany in 1710 (fig 5 and 6).

These were oddities of Nature, but the colour change in the skin of black adults

affected by depigmentation, turning to entirely white hues, or those who were already

born with these large white patches, were even more bizarre. The Philosophical

transactions of the Royal Society of London documented several of these cases. Another

case of a “white negro” child, whose ancestry was thoroughly traced and faithfulness of

the mother proven, was recorded in 1766. Other new cases were added, such as the

woman whose black skin had turned to large white patches all over her body, in 1760.

Back in 1696 the case of a “negro” child born with white patches on his skin was

recorded; in this case, too, the ancestors and the faithfulness of the mother were taken

into account. Research published by the Royal Society raised a number of doubts and

conjectures that read like a comedy of errors. It was no wonder, then, that William

Hogarth’s satirical gaze produced the engraving, The Discovery, in which onlookers and

a bewildered husband (or maybe father) are surprised to find a “negro” woman in a bed

previously occupied by what must have been a “white” woman, by the portrait of a

European woman hanging in the bedroom and the legend that reads, “qui color albus

erat, nunc est contrarius albus” (fig. 7)11.

It was often not possible to resort to maternal imagination to safeguard the

honour of the mother when the mother had never before seen a “white” man. Maternal

imagination was a scientific notion deeply rooted in the eighteenth century. It came

11 William HOGARTH, The Discovery, c. 1743, engraving, Royal Library, Windsor Castle,

Windsor, UK.

7

about when the mother, particularly during sex, but also in her daily life, had a fixation

on a colour, an animal, a type of person, object, etc. The child, due to the power of the

mind over the womb, therefore took on the characteristics of its mother’s fixation.

This was the explanation given in the famous case of Mary Sabina, from

Cartagena de Indias. Her mother had a dog with black spots whom she adored and was

always by her side. The Jesuit missionary and explorer, José Gumilla, told the story of

this girl, along with other similar cases, in his celebrated 1745 work, El Orinoco

ilustrado y defendido, historia natural, civil y geográfica de este gran río12

. He assumed

that the mother’s fixation with her spotted dog must have been the cause of the girl’s

appearance. He also reported that several portraits were painted of the girl, and that one

of the first was sent to England, although it seems that the English ship was captured by

the French privateer La Royale, along with the original painting. So, thanks to a certain

Monsieur Taverne it ended up in the hands of Buffon, who immortalised it in his

Natural History (fig. 8).

Gumilla also noted that people wanted to buy the girl herself, but they did not

want to cause her parents grief (would not they be the ones who decided to sell?), and

he advised them not to exhibit her too much so that she would not be exposed to the evil

eye. In the end, the image of Mary Sabina became the most famous of the “pious” or

“variegated” negroes. Buffon included her in his Natural History, but it does give us

pause for thought that, in his extensive work, he only speak of animals and “negroes”,

“pious negroes” and albinos, never of Europeans, or of the natural history of humans.

Many copies were made of this girl’s portrait; even John Hunter had to have one

in his collection, and managed to obtain one. But it is notable how this most dishonest

12 José GUMILLA, El Orinoco ilustrado y defendido, historia natural, civil y geográfica de este

gran río, volume I, Madrid: Manuel Fernández, 1745, pp. 95-115.

8

of “resurrectionists” (fig. 9) – here we see the surgeon fleeing from some watchmen –

has Mary Sabina covered like Christ with a sheet over her pubis. Buffon, however, a

Frenchman well accustomed to the libertinism of his time, or a faithful historian of

Nature, shows her naked, her pubis on display.

However, his other famous engraving (1777) of a “white negro”, Geneviève

(fig. 10), has her pubis covered, almost certainly because she was already a woman:

she was 18 when the engraving was done. At first Buffon doubted that “white negroes”

could have children with “negro” or “white” men or women, as if they were a different

species; but he soon dismissed these ideas when he adopted the epigenetic theories of

Maupertuis13

. It seems he had not had much contact with the casta paintings of Spanish

America, in which he would have seen countless examples of mestizaje

(miscegenation), as well as albinos (fig. 11).

Buffon was able to observe Geneviève in the flesh, since she was brought from

Santo Domingo to Paris. In her case, it was also noted that her ancestors had completely

black skin. He commissioned a lithograph in which the setting was similar to her place

of origin; a basket of exotic fruits went some way towards achieving the right effect, but

the space was completely closed and could just as well have been a room in France.

One whom Buffon would not have met in person was an Amerindian woman

from los Caparachos. She was albino, very beautiful, but anthropophagous, according to

the Quadro de la Historia Natural, Civil y Geográfica del Reyno del Perú (1799)

illustrated by the French painter Louis Thiébaut, with texts by José Ignacio de Lecuanda

(fig. 12 and 13): an authentic pictorial representation which in turn contains

13 Andrew CURRAN, “Rethinking Race History: the Role of the Albino in the French

Enlightenment Life Sciences”, History and Theory, 48, October 2009, pp. 151-179.

9

encyclopaedic information about Peru. It may be found in the National Museum of

Natural Sciences in Madrid, and it is quite fascinating to see how image and text

combine to provide information, somewhat like an eighteenth-century computer.

But let us return to the “pious negroes”. A growing fascination with these figures

brings together scientific curiosity with an idle curiosity more typical of fairs and

entertainment: carnivals (fig. 14 and 15). Here we see the famous Bartholomew

Fair on a summer’s night in London. It was just one of many. The public were delighted

by magicians, exotic animals, comedians, tightrope walkers, acrobats, contortionists,

men playing with newly-discovered electricity, exotic animals, and monsters –

including the “piebald negroes”. Here is a very amusing image in which we can make

out, amidst the wild abandon of the fair, the figure of John Boby, an adult “pious negro”

who was exhibited at this fair in 1795 and other years. His hat prevents us from seeing

the white streak of hair that fell over his forehead (fig. 16). Boby came from the

island of Saint Lucia, and his mother was so frightened at the sight of a baby with such

marks that she refused to breastfeed him. A Liverpool merchant seized this opportunity

to put him on display. These exhibitions must have been grotesque, but portraits of him,

with the exception of that shown above, were done with a certain dignity. John Hunter

obtained a portrait for his collection (fig. 17) and the other image, a poster, represents

him with even more elegance and dignity (fig. 18). If we look closely, the large

triangular white streak that reaches the forehead of the “negro” is common to all the

“pious negroes”: it may also be observed on Mary Sabina. This other poster from 1790

(fig. 19) is also quite endearing. John Primrose Boby is holding another portrait of

10

himself in earliest infancy, being announced as always, and he stares at himself with

feelings of melancholy, simple sadness, or who knows, maybe even a little pride.

There was not that much difference between the collections of men of science

and fair exhibits: they sought the same objects. Boby was exhibited through the medium

of art in the collection of John Hunter and in person at the fair – which the anatomist

would almost certainly have visited. John Hunter also collected an engraving of “pious

negro” girls from the island of Saint Lucia, according to the surgeon’s print (fig. 20).

It bears an excessive similarity to the illustration shown by Curtius (fig. 21), the great

wax sculptor, the magician of the Palais Royal in Paris, who made excellent full-size

wax figures of the great men of France and of exotic beings such as “pious negroes”, as

well as many other spectacles, such as shadow puppets. The man who taught Mme

Tussaud the art of wax modelling had a salon at number 7, where the portrait of these

three girls was exhibited, but in this case they came from Guadeloupe. Naturally, it was

visited by people of every class and distinction – leisure was a universal right – and men

of science developed theories about the oddities on view, or at least collected them for

their own cabinets. Another example hangs in the gallery of anthropology in the

Museum of Natural History in Paris: two small portraits from 1782 depicting a little

“pious negro” girl from Martinique being cared for by her mother, who has completely

black skin (fig. 22 and 23).These pictures are by Le Masurier.

Speaking of wax figures, we may also mention the wax figure of Madeleine

(fig. 24), a young “pious negro” girl from Martinique whose parents had entirely

black skin. Her right arm is raised, fist clenched, and she is smiling. This figure was

acquired by the Warren Anatomical Museum in Harvard, Boston, in 1782.

11

If we look at the theories, however, they were somewhat uglier. One of these

theories about the “pious negroes” (and also about all “negroes”!) was developed by

Benjamin Rush, a physician and one of the founding fathers of the United States. For

Rush14

, “pious negroes”, like all other “negroes”, suffered from a benign leprosy; this

theory was shared by the art theorist and creator of the fateful facial angle thesis, Petrus

Camper. Rush recommended rubbing peach juice on the skin as a remedy.

To conclude, we shall cast doubt on the “pintado do natural” (painted from life)

legends. The Portuguese artist, Manoel Joaquim Leonardo da Rocha, claimed to have

painted, from life, the portrait of a pubescent “pious negro” girl in 1786 on the island of

Santo Domingo. Her portrait could, in turn, be found in the Faculty of Medicine of

Paris, the Museum of Natural History in Madrid and the Zoological Museum (!) of the

Polytechnic School of Lisbon (fig. 25). What is truly impressive is that he created

this painting without ever setting foot outside Portugal, copies of which were highly

successful. Perhaps, through descriptions of Santo Domingo, he managed to create a

work of art in which the expression of the protagonist – in the museum in Madrid she is

still considered to be a boy – does not show the universal female emotion criticised by

Schiebinger. This girl did not only appear in academic circles. Curtius, he of the Palais

Royal, made a life-size wax figure of her. Such was the fame of Da Rocha’s protagonist.

Finally, we shall journey to a wedding in which this girl also appears, a Bridal

Masquerade painted by another Da Rocha, José Conrado, also dated 1786 (fig. 26).

“Negro” dwarves following European customs, indigenous people, and the famous

“pious negro” girl subvert the established beliefs of the European world, as in a

14 Benjamin RUSH, “Observations intented to favour a supposition that the black colour (as it is

called) of the Negroes is derived from the leprosy”, Transactions of the American Philosophical

Society, IV, p.297.

Related Documents