Stravinsky, Adorno, and the Art of Displacement Author(s): Pieter C. van den Toorn Source: The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 87, No. 3 (Autumn, 2004), pp. 468-509 Published by: Oxford University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3600933 . Accessed: 06/12/2013 04:30 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. . Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Musical Quarterly. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 78.104.70.246 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 04:30:11 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Pieter Van Den Toorn - Stravinsky, Adorno, And the Art of Displacement

Nov 27, 2015

20th century music

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

Stravinsky, Adorno, and the Art of DisplacementAuthor(s): Pieter C. van den ToornSource: The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 87, No. 3 (Autumn, 2004), pp. 468-509Published by: Oxford University PressStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3600933 .

Accessed: 06/12/2013 04:30

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The MusicalQuarterly.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 78.104.70.246 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 04:30:11 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Twentieth Century and Beyond and Institutions, Technology, and Economics

Stravinsky, Adorno, and the Art

of Displacement

Pieter C. van den Toorn

Much of what is characteristic of Igor Stravinsky's music may be defined rhythmically in terms of displacement, shifts in the metrical alignment of repeated motives, themes, and chords. Stravinsky himself often began here, in fact, not necessarily with a committed set of pitch relations, one that is octatonic, for example, but with a phrase turned rhythmically, a motive or chord displaced in relation to a steady metrical framework. The many references in his published remarks to starting ideas bear this out, as do the works and sections of works themselves-Russian, neoclassical, and serial in origin. Even before the birth of concrete ideas, the composer would set himself in motion by "relating intervals rhythmically," improvising on a set of "rhythmic units." This initial exploration, he later confessed, "was always conducted at the piano."1

Adorno began here, too. Targeted in his celebrated indictment of Stravinsky's music are, above all, the composer's rhythmic practices, the frequent displacement of accents, and the disruptive effect of displace- ment on the listener. The absence of expressive timing is bemoaned, the lack of any "subjectively expressive fluctuation of the beat."2 And instead of the developmental style of the classical tradition (as defined by Arnold Schoenberg, Adorno's point of departure musically and music-analyti- cally), the repetition in Stravinsky's music was relentless and literal. No development could be inferred, no elaboration of motives or "motive- forms."3 So paradoxical in a music that could seem outwardly vital from a rhythmic standpoint, the overall effect was often one of standstill or stasis, an invention "incapable of any kind of forward motion."4 "The repetition constantly presents the same thing as though it were something different," Adorno complained. "Farcical and clownish, it has the effect of putting on airs, of straining without anything really happening."5

Such characterizations form the liveliest part of Adorno's critique. Descriptions of one kind or another, they address the psychological effect of Stravinsky's music. At the same time, however, they are often incom- plete and fragmentary, with the task of piecing them together left to the

doi: 10.1093/musqtl/gdh017 87:468-509 (? Oxford University Press 2005. All rights reserved. For permissions, please e-mail:

This content downloaded from 78.104.70.246 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 04:30:11 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Stravinsky, Adorno, and the Art of Displacement 469

reader. Adomo's approach is unsystematic to the point of being unintelligible ("anti-systematic," as some have suggested more sympathetically),6 with the analytical descriptions themselves hemmed in by sweeping philosophical and sociological conjectures often no less fragmentary in character. The stream of consciousness can be explained by the dialectical processes at work, but only up to a point, and the suggestion of many of Adorno's adherents to the effect that the critic-philosopher fetishized this particular aspect of the process (its lack of finality) can seem real enough.7 Adorno acknowledged the "constellation"-like effect of his thought and prose,8 but the results can often seem like waywardness all the same, a poetic obscurity substituting for the more determined effort to address head-on the complexity of the issues raised.

Indeed, there are problems with the analytical description as well. As Max Paddison has observed, "a strange disparity" exists between "the sophistication and radicality of [Adorno's] aesthetics and sociology on the one hand and the lack of sophistication and traditional character of his music-analytical method on the other."9 Actually, it is not so much the thematic-motivic model of analysis inherited from Schoenberg that lacks sophistication as it is its application (or lack of application). Missing not only in Adorno's Philosophy of Modern Music10 but also in a later essay on Stravinsky11 are definitions of every conceivable kind (elementary ones for terms such as "accent," for example), identifications of passages and sections of works cited, and the analytical detail that must necessarily qualify generalization if generalization is not to lapse into polemic. The need for concrete detail-for the grounding of abstract terms and con- cepts "in the structure of the music itself'-is acknowledged early on in the Philosophy of Modem Music,12 but is never allowed to materialize in the form of an effective supplement.

Yet the bits and pieces of Adoro's description are worth pursuing all the same. And they are so more for the musical illumination than for the larger philosophical and sociological ideas to which they are attached (and from which, as Adorno and his adherents have insisted, they not only derive their meaning but are "inseparable").13 They are worth pursuing for the musical and music-historical sense that can be made of the juxta- position of Schoenberg and Stravinsky, the juxtaposition of the classical or "homophonic" style as defined by Schoenberg (the style of "developing variation")14 and Stravinsky's processes of displacement. Where the con- struction of thematic material is concerned, the invention and use of such material, these two worlds can indeed seem to stand apart in ways that are immediately identifying, ways that can enliven experience and its reflection.

Confronted in Adorno's Philosophy, and in the later Stravinsky essay as well, is that single dimension in Stravinsky's music that has seemed

This content downloaded from 78.104.70.246 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 04:30:11 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

470 The Musical Quarterly

most to identify it in the ears and eyes of the listening public, namely that of rhythm and meter. The features that preoccupy Adorno are those that tend to stand out, in fact, perhaps in works of the early Russian period above all: the mechanical nature of the beat and its transmission, the displacement of accents, the rigidity of the juxtapositions, and the seem- ingly unvaried and relentless nature of the repetition. Touching on matters that pertain to the listener's immediate response to Stravinsky's music, Adorno's concerns can be made to relate to wider and more tangible ones, to the listener's "entrainment" of meter, for example, to the role of expec- tation in music, and to the way in which emotion (pleasureful or not) is aroused. In Leonard Meyer's now classic formulation of "emotion and meaning" in the Western art tradition, emotions are stirred when implica- tions or tendencies are inhibited or arrested, when established norms are broken.15 And the way in which expectations of metrical parallelism are thwarted by displacement in Stravinsky's music, with the meter often dis- rupted as a result, figures as an instance of this type of interaction. Indeed, there is little reason why Adorno's critique should not be scrutinized from perspectives of this kind, be made to relate to the world of music theory and analysis and its ties to issues of perception and cognition.

Much of this can be pursued irrespective not only of Adorno's philosophical ideas, but of the still larger framework (mainly Hegelian and Marxist) to which those ideas are attached. Indeed, it can be pursued irrespective of Adorno's critical verdict. The latter need not be accepted in order for the analytical description, harnessed as a means of support, to be appreciated. Our understanding can be reasonably sympathetic, in fact, without in any way accepting the "no" of Adorno's account. Indeed, as Virgil Thomson remarked some time ago, where matters of musical under- standing and criticism are concerned, the actual opinions of critics need not concern us unduly.16 What counts is the musical understanding that is brought to bear, the features that are noticed, described, and com- mented upon in one way or another. The Schoenbergian model of the classical style can serve as a useful foil for Stravinsky's music regardless of the larger and less tangible philosophical and sociopolitical meanings to which, in Adoro's account, that model is attached. On the more speculative side of Adorno's argument, too, many of the negative images can be detached and replaced by positive ones.

With this in mind we shall first be seeking to retrace the steps of Adorno's critique, supplementing the analytical description with the detail and exemplification often missing in the Philosophy. Following this, a detailed definition of metrical displacement and its implications in Stravinsky's music will be attempted, followed in turn by a number of rebuttals of Adorno's argu- ment. Conclusions will then lead to a somewhat less strident, less polarized

This content downloaded from 78.104.70.246 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 04:30:11 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Stravinsky, Adorno, and the Art of Displacement 471

view of the Schoenberg-Stravinsky divide, one in which the great variety of displacement in Stravinsky's music can imply processes and psychologies that are not always at odds with those of more traditional tonal contexts.

Adoro Interpreted

Adorno is struck above all by the "concentration of accents and time rela- tionships" in Stravinsky's music. The "most elementary principle" of this "concentration" is displacement: melodic fragments and motives are constructed in such a way that "if they immediately reappear, the accents on their own accord fall upon notes other than they had upon their first appearance."17 Because of their irregularity, the shifting accents "can appear to be the result of a game of chance." They can seem to be "under a spell."18 The game they play is an "arbitrary" one, according to Adorno, one whose rules lie beyond the control of the listener. And the arbitrariness of the game precludes participation and engagement on the part of the performer or listener. The listener's role is reduced to that of a spectator.

Stravinsky's displaced accents resist assimilation. They cannot be anticipated, and so appear as "shock effects."19 And while "shock" is accorded a legitimate place in the reception of much contemporary music (in that of Schoenberg's atonal and twelve-tone music, above all, where Adorno identifies it with a sudden recognition of the horrors of the modern world), its effect in Stravinsky's music is viewed as debilitating. Deprived of the ability to anticipate, listeners cannot absorb the irregu- larly shifting accents of displacement. "Shock" overwhelms them, and they lose their "self-control." "In Stravinsky, there is neither the anticipa- tion of anxiety nor the resisting ego; it is rather simply assumed that shock cannot be appropriated by the individual for himself. The musical subject makes no attempt to assert itself, and contents itself with the reflective absorption of the blows. The subject behaves literally like a critically injured victim of an accident which he cannot absorb and which, there- fore, he repeats in the hopeless tension of dreams."20

Reference here and elsewhere in Adorno's account to a "musical subject" implies dramatization. "The musical subject" rather than the listener falls victim to Stravinsky's arbitrarily displaced accents. (The listener is seldom mentioned in Adorno's account, in fact, although "listener" and "subject" are clearly interchangeable in this regard, with each viewed as the victim of the same set of musical circumstances.) Thus, the music lacks an overriding pattern according to which the irregularly shifting accents could be organized. In Adorno's descriptions, the listener's inability to organize these accents becomes the subject's

This content downloaded from 78.104.70.246 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 04:30:11 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

472 The Musical Quarterly

inability. Just as the listener loses his or her metrical bearings, so, too, the subject cannot "heroically reshape" the displaced accents in his or her image: the accents are experienced as "convulsive blows and shocks."21 And although the specifics of this listener-to-subject translation are omit- ted from the record, they are an integral part of the equation. Without them, Adorno's characterizations would make little sense.

Central to Adorno's argument is the idea of a balance in music of the highest quality, a balance between the four musical dimensions of melody, harmony, rhythm, and form. In Stravinsky's music, this is overturned by an emphasis on rhythm and, more specifically, on displacement and its effect of shock. That "great" music could consist of such an ideal equilibrium-one good for all seasons, as it were-is an idea traceable to Schoenberg (Adorno's likely source, in any case),22 although it appears in other guises early in the twentieth century as well. Schoenberg wrote of the need for music to develop consistently and "equally" in all direc- tions.23 Not only were these directions inseparable, but an emphasis on one could come only at the expense of the others. Ideas similar to these were expressed in a number of critical surveys during the 1920s and 1930s, including Cecil Gray's A Survey of Contemporary Music (1924). There, each parameter is viewed similarly as being "at its highest when all are in complete equilibrium, when one does not predominate over the others."24 Music "of the greatest masters" is neither harmonic, rhythmic, nor melodic, according to Gray; "it is all and it is none."25 Adorno's version of this ideal runs as follows:

Stravinsky's admirers have grown accustomed to declaring him a rhythmist and testifying that he has restored the rhythmic dimension of music- which had been overgrown by melodic-harmonic thinking-again to honor.... Rhythmic structure is, to be sure, blatantly prominent, but this is achieved at the expense of all the other aspects of rhythmic organization.... Rhythm is underscored, but it is split off from content, it results not in more, but rather in less rhythm than in compositions in which there is no fetish made of rhythm.26

Melody is the first casualty of these imbalances. Instead of a formation of shapes and contours, the melodies subjected to displacement in Stravinsky's music are "truncated, primitivistic patterns."27 No indepen- dent melodic life may be inferred from these "patterns," no structure to speak of. Melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic features are not subjected to a "developing variation" along the lines implied by the Schoenbergian model, but are repeated literally and relentlessly. They are not varied, and without variation, progress and development are thwarted as well. For it is

This content downloaded from 78.104.70.246 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 04:30:11 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Stravinsky, Adorno, and the Art of Displacement 473

only by means of a process of elaboration that the repetition of motives and thematic segments can add up to an overreaching design or train of thought, something other than a mere sum or total. With Stravinsky's "primitivistic patterns" and their repetition, there are only "fluctuations of something always constant and totally static."28 The much ballyhooed rhythmic invention "consists of varied recurrence of the same; of the same melodic forms; of the same harmonic patterns, indeed, of the very same rhythmic patterns."29

Evidence of a musical nightmare of this kind may be found on virtually any page of Stravinsky's music, but see, as a starting point here, the repeti- tion of the A-D-C-D fragment in the horns in the "Ritual of the Rival Tribes" and "Procession of the Sage" in The Rite of Spring (1913; see Ex. 1). Repeats of this "primitivistic pattern" (ten in all) are without elaboration, transposition, or changes in articulation, dynamics, or instrumental assignment. All is fixed from start to finish in these respects: the first two notes of the fragment are always accented, while the last three, D-C-D, are always slurred. What changes is the fragment's alignment in relation to the steady 4/4 meter and the accompanying parts. Entering on the fourth, first, third, and second quarter-note beats, respectively, the frag- ment falls on and off the half-note beat, the likely tactus here with a met- ronome marking of 83. (The half-note beat, along with the sensation of falling on and off it, is likely to define the conditions of displacement in this passage. At a level of pulsation just below the tactus, the quarter-note beat becomes a subtactus unit, the level of the pulse, as we shall presently be defining it.)

In turn, the steady meter on which displacements of this kind hinge is likely to impose itself independently and prior to the entrances of the horn fragment and its sustained Ds. The repetition of the G-F-E-D frag- ment in the first violins is crucial in this regard. As a point of departure and return, the pitch G in this fragment falls on the downbeat, while the fragment's division into two segments, or "cells" (labeled A and B in Ex. 1), with each of these segments spanning the 4/4 bar line, lends further sup- port for the 4/4 framework. Further along, repeats of the accompanying segments in the tuba, although irregularly spaced at rehearsal nos. 64-67, serve as an additional means of support-indeed, following the removal of the reiterated fragment in the violins at rehearsal no. 66, as a constant backdrop in this respect. The spans of these entrances are multiples of two and four; repeats of the segments G-sharp-F-sharp(G)-(G-sharp) and G-sharp-A-sharp-C-sharp-A-sharp-(G-sharp) are aligned in a metrically parallel fashion.

In sum, while repeats of the various segments in the first violins and tubas are spaced irregularly, they are metrically parallel in relation to the

This content downloaded from 78.104.70.246 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 04:30:11 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

474 The Musical Quarterly

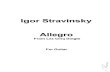

"Ritual of the Rival Tribes"

164]

Vln. I -- a I e~ AV-a -l - -b -- , a-

_ . -a

65] -b , a

164 r rr r rj r- r - r- rrr r gr r rf Tenor Tuba (col8ve) 20

Tuba

B.d. rT-3 3 3 3-- 3 --

\66\ 3b

Hns. 6 Hns. 6 , 8 ,, 13

9 tt-

:? 1 -

11-16 8I -

12

Bns. etc.

3 3 3 - 3 ] etc.

^1_J- I I J :- ̂ ,-- I J- ,- , etc.

F671 68i 13 F 13

II: X $ C: -:

0 t

Ff 7 OJ- i 6I- , -

7. - 7 #. o r16. 1 -

Example I. Stravinsky, The Rite of Spring, "Ritual of the Rival Tribes," "Procession of the Sage." ? Copyright 1912, 1921 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Copyright renewed. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

This content downloaded from 78.104.70.246 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 04:30:11 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Stravinsky, Adorno, and the Art of Displacement 475

"Procession of the Sage" 69

17 17 A I

6 , i

I I, .

16 16

8 l 8 , , 8 8

i9j if r- `j -_1 16 l l j16 16

' ~ l'frt ~' #r #l' # I-r rI 1'#r ' b f # l' f~0

Example continued Example 1. continued

4/4 bar line. The two fragments are not ostinati, strictly speaking, but the

displacement that results from the irregular spanning of their repeats is

hypermetrical rather than metrical. Typical of the melodic invention in

Stravinsky's Russian-period works, the reiterated G-F-E-D fragment in the first violins is sliced up into smaller segments. Labeled A and B in

Example 1, these segments are reshuffled: after each repeat of segment A, segment B is repeated once, sometimes twice. Significantly, however, all

repeats of these segments fall on the downbeat of the 4/4 bar line. And this parallelism is likely to reinforce the sense of a 4/4 hierarchy. At the outset of this passage, the effect is likely to be one of at least relative stability, and in preparation for the entrances of the sustained Ds and A-D-C-D

segment in the horns. The latter are not only irregularly spaced, they are metrically nonparallel as well; the latter entrances are the troublemakers in this passage: the cause, as we shall see, of metrical conflict. (The conflicting cycle of the bass drum noted in Ex. 1 will come to the fore fur- ther along, and then only in the form of a challenge; even at rehearsal no. 70, where the notated meter changes to 6/4, the sense of a duple or 4/4 bar line is likely to persist.)

8

I, . 1 '7.

This content downloaded from 78.104.70.246 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 04:30:11 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

476 The Musical Quarterly

Pitch relations in this example follow an analogous path. The octa- tonicism at the outset is explicit and relatively unimpaired. Consisting in the main of the tritone-related 0-2-3-5 Dorian tetrachords G-F-E-D and C-sharp-(B)-A-sharp-G-sharp in the first violins and tubas, respec- tively, octatonic relations are qualified diatonically by the D-scale on G, implied by the accompanying parts in the strings (see Ex. 2: the dotted line beneath the quotation signifies octatonic-diatonic interaction in terms of the single octatonic transposition Collection II and the D-scale on G, shared by these two interacting orderings of reference is the G-F-E-D tetrachordal fragment, which serves as a connecting link).30 And this, too, would seem to be in preparation for the entrances of the A-D-C-D fragment in the horns. Articulating another 0-2-(3)-5 incomplete Dorian tetrachord, here in terms of D-C-(B)-A, the latter entrances are foreign to Collection II. The clash with the C-sharp-(B)-A-sharp-G-sharp tetrachord in the tubas is likely to be especially harsh in this regard.

Typical of Stravinsky's music as well is the layered or stratified struc- ture that may be inferred. Fixed registrally as well as instrumentally, frag- ments in the first violins, tubas, and horns repeat according to cycles that vary independently of one another.31 The varying cycles in the horns and tubas result in an alignment or coincidence that changes vertically or "harmonically" as well as metrically. Yet the "harmonic" changes are locked into a limited set of variables from the start; harmony in the large is exceedingly static. The sound of the superimposed fragments midway through this passage is little different from what it is at the beginning or

64 [~ Strings

f etc.

9:4 " f Tuba , '1- I'-

mf

7

<j' ^ -* .) (-, ( ' ' ) (- b . -

' ' #: . #. #* . ' - - b. .

Octatonic scale Dorian scale Collection II

Example 2. Stravinsky, The Rite of Spring, "Ritual of the Rival Tribes," opening. C Copyright 1912, 1921 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Copyright renewed. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

This content downloaded from 78.104.70.246 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 04:30:11 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Stravinsky, Adorno, and the Art of Displacement 477

the end. As with the separately moving parts of a giant locomotive, the individual fragments churn away with little, if any, local, over-the-bar-line sense of harmonic movement or progress.

A starker contrast to the world of developing variation would be difficult to imagine. There are motivic variations, as we have indicated, changes in motivic succession (reshuffling), durational spanning, and metrical placement. But the sort of melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic vari- ations identified with the earlier developmental style are missing altogether. There are only "fluctuations of something always constant and totally static," as Adorno complained. The invention consists merely of"a varied recurrence" of the same melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic "patterns."

Indeed, processes of metrical displacement, along with the stratification of this passage, preclude the sympathetic give-and-take of the world of developing variation, in the way in which motivic particles, detached from themes, are exchanged between instrumental parts. In Example 1, the horn fragment is not tossed about from one instrument to the next, made the subject of a "dialogue" in this respect (as it might have been in, say, a string quartet of Haydn or Mozart). It is not treated "humanistically" by such means (as the character of such treatment has often been imagined, at the very least, in modern times, since the dawn of chamber music).32 And it is not treated expressively, either. If the displacement of the A-D-C-D fragment in the horns is to have its effect, then the beat must be held evenly (mechanically) throughout, with little if any yielding to the conventions of expressive timing and nuance, the means by which, traditionally, performers have made their mediating presence felt.

So stark is the contrast, in fact, with so many of the familiar givens of the developmental style missing, that anything but the most negative of accounts on the part of a critic such as Adorno would have been difficult to imagine. It can almost seem as if the impression gained would have had to have been that of a cold, stiff, and unyielding music. Here, however, the point concerns the "protest" that, according to Adorno, music has always represented: "the protest, however ineffectual, against myth," against "the inexorable bonds of fate."33 No cry in the dark could be heard in Stravinsky's music, no "inner self' in its struggle with "outrageous for- tune," expressing the inexpressible. All this seemed missing as well, replaced by barking proclamations: "Thus it is, and not otherwise," the composer seemed to be saying from one unvaried repeat to the next. And the proclamations seemed to be those of an authority, of someone in charge, not those of the lone individual. "Stravinsky's music identifies not with the victims," Adorno complained in one of his more provocative pro- nouncements, "but with the agents of destruction."34 Indeed, it identifies with the fascists who were just then appearing on Europe's horizon.35

This content downloaded from 78.104.70.246 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 04:30:11 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

478 The Musical Quarterly

More generally, the "identification" of Stravinsky's music "with the collec- tive" admits of two interpretations: Adomo makes reference to a "primitive," pre-individual age, and to a modern, industrial one.36 The musical subject behaves ritualistically in these worlds, "regressively" and in an "infantile" manner.37 Stravinsky's music is "anti-humanistic" in these respects. Its sympathies are not with the "suffering subject," but with the powers that be, various "agents of destruction."

In contrast, the developmental style symbolized for Adorno the ability of the subject to mature with time, to meet the day's challenges and to develop accordingly.38 While the subject remained locked in repetitive gesture in Stravinsky's music, unable to move beyond the trancelike stupor of ritual, he was relatively free in the world of developing varia- tion.39 This was the nature of the musical opposition Adorno sought to unravel, the split he attributed to Stravinsky's music, its tear from tradition and traditional sensibility.

A sampling of Adorno's analytical descriptions appears in Figure 1. Incomplete and fragmentary in the writings themselves, they are here compressed into a single train of thought. All are ultimately traceable to a single musical condition, namely that of metrical displacement. Two subsidiary conditions result from displacement: 1) inflexibly held beats (beats lacking in expressive timing); and 2) a repetition of themes, motives, and chords that, apart from the displacement itself, is literal and lacking in the traditional modes of elaboration or developing variation. The characterizations triggered by these conditions are relatively concrete, neutral, and observational to begin with in Figure 1, increasingly less so further on down the line. Indeed, the more specific the imagery, the less tangible and the more speculative. On the left side of Figure 1, the need for strict metricality in the performance of Stravinsky's music (the need for "expressive fluctuation" or nuance to be kept to a minimum) is made to imply mechanization and impersonality, which in turn are made to imply "anti-humanism" and a collective authority of one kind or another. On the right side, a lack of variation in the repetition of Stravinsky's motives is made to imply a similar lack of "identification" with the individual, the plight of the musical subject.

The descriptions and characterizations are Adorno's, as has been suggested, while the outline converts both the description and the charac- terization into actual features of the music, features that are then con- nected in the form of an explanatory path. A larger rationale is thus imposed along lines that are more specifically musical. (The outline is not Adorno's, in other words, but represents an attempt to piece the various descriptions together as a single line of thought.)

This content downloaded from 78.104.70.246 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 04:30:11 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Stravinsky, Adorno, and the Art of Displacement 479

Metrical Displacement

"convulsive blows and shocks"

I I~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

(1) inflexiblility of the beat; relative lack of expressive timing

non-espressivo secco

mechanical, lacking "nuance" or "expressive fluctuation" (pianola)

non-individual impersonal "depersonalization" unfeeling

(2) literal (unvaried) repetition; relative lack of elaboration or developing variation

incantatory style, ritualistic "primitive patterns" static quality immobi ity

non-individual impersonal "collective" "murderous collective"

"anti-humanistic" "agents of destruction"

Figure 1. Adoro's Characterizations in the Form of an Explanation.

Displacement Defined

Often missing from Adorno's account, in fact, is precisely the sense of a larger rationale for Stravinsky's music, what it is that connects the various musical components, motivates or triggers one factor in relation to the others. No doubt, as Adorno insists, the concern in Stravinsky's music (and in his settings of displacement more specifically) is not with the features of a motive and their elaboration, but with just the opposite, namely the literal repetition of such features. Yet there are reasons for the unvaried nature of the repetition, reasons that are musically specific. The repetition in Stravinsky's music follows a different logic. In works of the Russian period above all, Stravinsky repeats not to elaborate or to develop along traditional lines, but to displace. And in seeking metrically to

This content downloaded from 78.104.70.246 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 04:30:11 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

480 The Musical Quarterly

displace a repeated theme, motive, or chord, the composer seeks to retain features other than alignment in order that alignment itself (and its shifts) might be set in relief. The literalness of the repetition acts as a foil in this respect. As features of pitch, duration, and articulation are retained, the metrical alignment of the given theme, motive, or chord shifts.

This is not the whole of it, however. Literalness in the repetition of a fragment acts as a counterforce, too, a way of referring the listener back to the fragment's original placement. In direct opposition to displacement, it implies metrical parallelism, a repetition of the original alignment along with all else that is repeated literally.40 And the more that is repeated literally, the more fully aroused are these conflicting expectations of metrical parallelism likely to be.

The implications here are quite fiendish. To repeat a theme, motive, or chord literally and without variation so as to highlight and expose its metrical displacement is to undermine that displacement at the same time. It is to raise a conflicting signal of metrical parallelism. Typically, and with varying degrees of intensity, listeners are caught off guard. Unable to commit themselves initially one way or the other, to a reading of displacement or one of metrical parallelism, they are apt to lose their metrical bearings.41 This is the origin of the disruptive effect of displace- ment, indeed, of the "convulsive blows and shocks" to which Adorno refers. It has to do not with one or the other of these two signals, not with metrical displacement or parallelism strictly speaking, but with their con- flict, with the fact that there is insufficient evidence for an easy, automatic ruling in favor of one or the other. Crucially, too, the two sides are not reconcilable. Listeners cannot attend to both simultaneously.42

In Example 1 from The Rite of Spring, the horn fragment A-D-C-D is introduced on the fourth quarter-note beat of a 4/4 measure, only to be displaced to the first quarter-note beat several bars later. In half-note beats, it falls first off and then on the beat. How is this shift likely to be interpreted? Will listeners read through the displacement with the steady 4/4 meter sustained as a frame of reference? Or, alternatively, will they be taken in by the literalness of the repetition, by the fixed character of the articulation of accents and slurs? Will they attempt to match that literalness with the fragment's original placement off the half-note beat? And will they do so by interrupting the meter at the half-note beat, adding an irregular (or "extra") quarter-note beat to the count at rehearsal no. 68?43

The first of these alternatives is "conservative" in nature.44 An established meter is sustained (conserved) in order that the "same" fragment might be read through placed and displaced. The second alter- native is "radical." The meter is interrupted in order that the repeat of the fragment might be aligned as before, that is, in a fashion that is metrically

This content downloaded from 78.104.70.246 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 04:30:11 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Stravinsky, Adorno, and the Art of Displacement 481

parallel. The reciprocity of the relationship between these two metrical interpretations is summarized graphically in Figure 2.

Reading from left to right, "conservative" listeners adjust the align- ment of a repeated theme, motive, or chord ("change") by holding on to an established meter ("no change"), while "radical" listeners do the reverse, adjusting their metrical bearings ("change") in order to persevere with an established alignment. A measure of conservation thus underlies both interpretations, whether it be meter, in the case of the conservative response, or alignment, in that of the radical one.

Stravinsky's notation will tend to reflect one or the other of these responses. It may not always reflect the one to which a given listener is drawn, but it will tend to reflect one or the other all the same. And it will do so categorically. If, at any given moment of the listening experience, the repetition of a fragment may be heard as placed or displaced but not both, then the notation is no less categorical. It, too, acknowledges either the displacement or the fixed placement of a repeated fragment.

The principal fragment in the clarinet in the opening allegro of Renard (1916) can serve as an additional illustration. The alternative bar- rings in Examples 3a and 3b are derived from the finished score and an early sketch of Stravinsky's, respectively.

Typical of Stravinsky's music, the fragment is sliced up into smaller segments or "cells," units that are then repeated independently of one another; the series of irregularly spaced entrances that results is 5 + 2 + 5 quarter-note beats. (The quarter-note beat is the likely tactus here with a marking of 84.) In the finished score (see Ex. 3a), the resultant displace- ments lie exposed to the eye. The assumption here is that the passage will be heard and understood conservatively, that is, with the clarinet

change no change

"conservative" -- placement meter (displacement)

"radical" * meter placement

Figure 2. Alternative Responses to Displacement.

This content downloaded from 78.104.70.246 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 04:30:11 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

482 The Musical Quarterly

a) Cl. A ?- ,--N.

/L ;I I T-T I I I I T I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I i

3 3

9:2 Tf

3 3 3

?l @

f .i 4 f f rI 4 2 L__f___

@ E

c _ ~~ X _ i- . _' , t- -. _ ~ - r_ - ^ -^ - ,N'i.^_

Example 3a-c. Stravinsky, Renard, opening allegro, mm. 7-13, score (conservative), early sketch (radical), and rebarred (still more radical). ? Copyright 1917 by J. & W. Chester, Ltd. (Chester Music), London. Reprinted by permission of G. Schirmer, Inc.

fragment newly placed at m. 9 and m. 10. Introduced on the bar line or half-note beat, the fragment falls off the beat twice and then on the beat

again at m. 13. The steady 2/4 meter on which these displacements hinge is introduced and then maintained in large part by the basso ostinato, which acts as a metrical backdrop.

The radical alternative, shown in Example 3b, stems from an early sketch of Renard.45 One of many in the sketchbook that would seem to indicate the composer's awareness of these conservative and radical

options, the sketch follows several drafts in which the conservative solution of the finished score is in place. (The sketch may have arisen as an afterthought, in fact, with the composer having wanted to test the radical option on paper.) Here, the meter shifts in order that the repeats of the clarinet fragment might be aligned in parallel fashion. All repeats fall on the downbeat. And much of the motivation for the notated metri- cal irregularity in Stravinsky's music may be traced accordingly, that is, to

attempts to expose these opposing forces of metrical parallelism. The parallel

- _- _ - F I

_ _ - _ F r FE _ ' _ Im - F- E I F -

h^L.fflU l Ff PI H- \iU Fr1 PIl I

,o_ '.

This content downloaded from 78.104.70.246 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 04:30:11 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Stravinsky, Adorno, and the Art of Displacement 483

alignment in the analytical notation of Example 3c is still more radical from this standpoint. (Like the passage cited in Ex. 1 from The Rite of Spring, the opening allegro of Renard is a layered structure.)

No doubt, compromises can sometimes be worked out in the nota- tion, often by crossing the bar line with beams-attempts, at least on paper, to preserve both an established meter and an established align- ment. But such solutions cannot alter perception or, indeed, the role played by an orientation, a frame of reference against which "events" are located, timed, and weighed. Listeners orient themselves as a matter of course, seeking a reliable groove, a context in this respect, a backdrop against which to organize "events." They can respond conservatively or radically to a displacement, but not in both ways simultaneously (however much, by means of a crossing of the bar line, the notation may imply the possibility of such an option). Opposing forces are set in motion, forces that are ultimately not reconcilable.

Yet the equivocation implied by the crossing of a bar line is not without perceptual implications. At least initially, the experience is likely to be conflicted, subject to a good deal of qualification or sensed opposition. A displacement is felt not in isolation, obviously, but as it relates to previously established placements. It implies those earlier placements, intimations of which surface not as part of an evolving sense of structure (an overriding pattern, in other words), but as something that conflicts. And this is crucial. The feeling is that of a prevailing assumption gone amiss, and of being taken unaware by this. Assumptions about meter and the metrical alignment of the repeated fragment or chord, inferred reflexively and internalized at some earlier point, cannot be sustained.46 The process may be likened to that of a rug being pulled suddenly and unexpectedly from under the listener's feet. And this is likely to be the case even with highly conservative readings, in which established levels of metrical pulsation may be clung to tenaciously. If only for a split second, a change in the metrical alignment of a repeated theme, motive, or chord is likely to bring about a disruption of that which underlies alignment, namely meter.

As depicted in Figure 2, the reciprocal nature of meter and metrical alignment is crucial. For it is not as if meter arose independently of place- ment and displacement, as if the materials of Stravinsky's music fell automatically (or mechanically) into place, wholly at the mercy of such a design. Themes, fragments, and motives may be introduced within an established metrical hierarchy, to be sure, acquiring, as a result of that introduction, a strong sense of placement (or location). Yet the processes themselves are reciprocal and work both ways. If alignment emerges from meter, so, too, in the mind of the listener, does meter emerge from alignment. The renewed parallel alignment of a given fragment may

This content downloaded from 78.104.70.246 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 04:30:11 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

484 The Musical Quarterly

confirm and reinforce an established sense of meter, just as a change in alignment (displacement) may disrupt that sense.47

At the first signs of change, in fact, confusion is likely to reign. A repeated fragment familiar to the listener is treated in an unfamiliar way, and the listener may be uncertain as to how to proceed. The specific nature of the change may not be known at first, but it may be sensed all the same. Figure 3 traces a possible response-pattern from an initial point of contact. Lasting anywhere from a split second to the lifetime of a listener's engage- ment with the context in question, an initial state of confusion is followed by a retrospective scramble to reestablish the lost frame of reference. Since the feeling is indeed likely to be that of an assumption gone amiss, assumptions in general are put to the test. Was the fragment's earlier alignment correctly inferred? Was the meter correctly inferred? Should it be sustained, allowing for a perception of displacement? Alternatively, should it be interrupted, allowing for a parallel alignment? Much of this can pass in a few seconds.

What listeners seek is a relationship, a way of relating the old with the new. Sought is a means of connecting the various placements, acknowl- edging all as part of a single train of thought.

At some point in their retrospective analyses, however, listeners are likely to read through the repeated fragment conservatively or radically. An attempt of this kind is likely to proceed with a good deal of sensed

retrospectively displacement Response No. 1

"conservative"

displacement; meter is sustained

doubt, continued

Listener uncertainty, doubt, >

d uncertainty disruption

placement; + meter is interrupted

displacement Response No. 2 "radical"

Figure 3. Responses to Replacement.

This content downloaded from 78.104.70.246 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 04:30:11 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Stravinsky, Adorno, and the Art of Displacement 485

opposition, however. One response is likely to qualify the other.48 And although retrospective analyses can facilitate subsequent readings, the stages outlined in Figure 3 are unlikely to be eliminated altogether. Listeners may proceed in an automatic, unconscious, or "bottom-up" way,49 according to which they are free to renew their initial experiences, includ- ing those of displacement and its disruption. They may proceed free of conscious memory, in other words, and in a way that allows them to go through "pretty much the same motions" from one hearing to the next, as Ray Jackendoff has phrased it in a related study of the cognitive implica- tions of renewed hearings; listeners can continue to hear the piece "as if for the first time."50 Hearings of this kind stand in contrast to "top-bottom" approaches, in which prior or immediate learning intervenes. Two systems of listening are thus at stake, each interacting yet independent of the other.51

And so the timings of the various stages outlined in Figure 3 are left open. They are likely to vary considerably not only from one context to the next, but from one listener to the next as well. Some displacements may be sensed fairly readily. Evidence in their support may be overwhelming, and the listener's initial doubt may be momentary and scarcely conscious. At other times, however, considerable thought and analysis may be required before the listener, retrospectively and with repeated hearings, "live" as well as "in his or her head," is able to arrive at a conservative or radical reading, an integration of the disputed passage with an evolving sense of structure. (Worst-case scenarios involve outright dismissals, cases in which a passage of disruption is never made a part of such an emerging sense. Radical responses can often arise by default in this way, the result of a listener's inability to follow through conservatively by sustaining an established meter against the forces of parallel alignment.)

So, too, details are likely to vary from one listener to the next. The same listener may react conservatively to one context, radically to another. And still another listener may switch in midstream, succumbing quite suddenly to the conflicting evidence that, up to that point, had served merely as a form of opposition. And the possibility of a conservative or radical predisposition cannot be discounted either. The degree to which steady meters are internalized and made physically a part of the listener (the degree to which they are entrained, to use the terminology of the psychologist,52 synchronized with our biological and cognitive func- tions, our "internal clock mechanisms"),53 may vary. Some listeners may be more susceptible than others in this regard. And their conservative responses may be a function of that susceptibility. Quite apart from the musical context in question, in other words, listeners may be predisposed to respond in the way they do. Figure 4 takes this possibility into account,

This content downloaded from 78.104.70.246 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 04:30:11 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

486 The Musical Quarterly

retrospectively displacement "conservative"

displacement; meter is

t * sustained '

doubt,

uncertainty, continued t~ I~ doubt,

disruption uncertainty

I I placement; - meter is interrupted

displacement "radical"

Figure 4. Responses to Displacement (with predisposition).

rearranging Figure 3 accordingly. Listeners arrive on the scene inclined to react conservatively or radically, to sustain an established meter or to yield in this respect.

The variables are numerous and complexity interwoven. Firmly established metrical frameworks favor conservative reactions, obviously, while literalness in the displaced repeat of a theme, motive, or chord will tend to favor the radical alternative, metrical parallelism and an interrup- tion of the meter. Size can make a difference, too. With lengthier fragments, the difficulties in adjusting to a new metrical alignment are likely to increase: displaced chords are more easily assimilated. Tempo plays a decisive role in the disruptive potential of a displacement, as does metrical location. And both these factors are open to measurement.

Figure 5 shows a way of classifying displacements on the basis of their location within a given metrical hierarchy or grid. (The given hier- archy here derives from the opening allegro of Renard. The signature is 2/4, and the likely tactus is the quarter-note beat with a marking of 84). Loca- tion is defined by two interacting levels of pulsation, a slower level that "interprets," "groups," or marks off the beats of a faster, "pulse" level.54 The pulse level is the highest level at which the placed and displaced entrances of a given fragment are beats, while the interpretative level is the next highest level at which those beats are marked off as onbeats or offbeats. In this way, displacement follows meter.55 At least two levels of

This content downloaded from 78.104.70.246 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 04:30:11 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Stravinsky, Adorno, and the Art of Displacement 487

Levels of pulsation location

1/16 .......................... -1

1/8 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

0

tactus /4 . . . .

+1

1 measure /2 . . +2

2 measures 1

Figure 5. Displacement and Metrical Location (Renard, Nos. 0-9).

pulsation must interact to meet its conditions, even if the effect of a given displacement may be felt at levels above and beyond that initial interaction.

The levels of pulsation in Figure 5 are grouped in overlapping twos. At a degree marked 0, beats at the level of the tactus "interpret" beats at the subtactus level just below. Here, the potential for disruption is at its highest: repeated fragments fall on and off the tactus, specifically in Figure 5, the quarter-note beat. At the degree marked +1, beats at the level just above the tactus "interpret" the tactus. Here, repeated fragments fall on and off the half-note beat rather than the quarter-note beat. In Example 3a, entrances of the clarinet fragment are defined in this way, falling on and off the half-note beat (or bar line). Beats of the half note rather than the quarter note are subject to interruption (quarter-note beats may con- tinue uninterrupted), the disruptive effect of which is likely to be milder. This concerns time and timing as well as human psychology. The actual disturbance of the half-note beat at the degree of + 1 may equal that of the quarter-note beat at the degree of 0. At a slower pace, however, displace- ment or the radical alternative of adding "extra" beats to the meter may be negotiated with greater ease.

Traditionally, too, this is where meter is centered, namely, with the regularity of the tactus and the identification of that regularity with the human pulse. This where "the beat" is, so to speak, where the sense of a steady alternation between downbeats and upbeats or onbeats and off- beats is likely to be most vivid. Meter's internalization is likely to be at its most sensitive, with immediate contact of this kind manifesting itself

This content downloaded from 78.104.70.246 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 04:30:11 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

488 The Musical Quarterly

outwardly as well; at the level of the tactus or just above, with beats synchronized with the "rhythmic" character of biological or cognitive processes, feet are tapped, steps taken, and so forth.

Then, as this acute sense of meter fades when moving away from the tactus, displacement fades, too. Extended beyond the degrees of 0 and + 1 in the direction of hypermeter, displacements are felt less keenly. Interalization or entrainment is less marked, so that when a fragment is displaced and the meter threatened or interrupted as a result, the sense of disruption is less severe. With more time, the listener is likely to have less of a struggle with what may indeed have become entrained, made physically a part of him or her. Conservative or radical adjustments or readjustments are made more easily.

Examples 4a-d show the displaced repeats of another fragment from the opening allegro in Renard, arranged here according to the graduated scale of locations of Figure 5. The initial placement is followed by three displacements at increasingly shallow locations: introduced on the beat of a two-measure span in Exam- ple 4a, the fragment falls off the beat of that span in Example 4b, off the half-note beat or bar line in Example 4c, and finally off the quarter-note beat in Example 4d. While the last of these alignments is purely analytical in conception, the first three do indeed occur in Renard, and in the order given in Examples 4a-c: following the initial placement, the degrees are progressively shallower, the displacements themselves progressively more disruptive in their potential.

Rebuttals

But is there no interaction at all between the style of developing variation and that of metrical displacement? Is the music of Schoenberg and Stravinsky wholly antithetical, as Adorno implies? And are Adorno's "convulsive blows and shocks" altogether unforgiving? Is there no merit in displacement and the disruption it can cause?

Even in the passage quoted from The Rite of Spring (see Ex. 1), where displacements in the repetition of the horn fragment A-D-C-D are likely to be disruptive of the meter, the experience can be mixed. Introduced off the half-note beat at rehearsal no. 67, the A-D-C-D fragment falls on the beat just before no. 68. Assuming that the shock of this initial shift can be absorbed without too much hesitation (assimilated either as a form of dis- placement or, by interrupting the meter with an "extra" quarter-note beat, as a parallel alignment), a second displacement on the beat a few bars later is likely to be more destructive. The uncertainty caused by the initial shift is likely to be renewed and strengthened. The possibility of such a

This content downloaded from 78.104.70.246 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 04:30:11 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Stravinsky, Adorno, and the Art of Displacement 489

a

/I th6 -

I nozh-nish ko zdes - ya,

/r- II - 'I I b , - 7 _ _: 2 ]

- 0

<p ̂ J^^# 4 J # i guzh - ish ko zdes - ya,

(9 X: , J b

(analytical)

'-^l-i; T ^ L I_^ b

.)=2 r3 3 I 6

Example 4a-d. Stravinsky, Renard, opening allegro.

second displacement is likely to be questioned first; the meter underlying it, second. While the quarter-note beat (here, at the pulse level) may con- tinue uninterrupted, its interpretation by the half-note beat is likely to be the subject of a breakdown, with the distinction between onbeats and offbeats lost. In the listener's scramble to reestablish his or her bearings (to reclaim, above all, a sense of the interpreting half-note beat), even the metrical character of the accompanying tuba fragment, otherwise consistent and in phase up to this point, is likely to be questioned. Indeed, the breakdowns are likely to continue through much of this passage. Introduced off the beat and on the fourth quarter-note beat of the 4/4 bar

A

d

(9X

( 0 X J ^nr=n_^ j~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

_ v A _ _

A

\-4; J J .

I

I

b

I I ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~I

I I I

This content downloaded from 78.104.70.246 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 04:30:11 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

490 The Musical Quarterly

line, the horn fragment shifts to the first, third, and second quarter-note beats, respectively. Although effectively "spotting" each quarter-note beat in this way, the displaced repeats are not strictly cyclical in relation to the bar line, and the spans they define are highly irregular (see the brackets in Ex. 1).

Yet the disturbances may remain temporary. Although irregularly spaced at first, repeats of the horn fragment reach the stable duration of eight quarter-note beats at rehearsal no. 70; seven successive repeats fol- low off the beat and on the second quarter-note beat. (Although the notated meter shifts to 6/4 at this point to accommodate a number of con- flicting periods in the accompanying parts, the 4/4 framework is likely to persist in the mind of the listener.) And the accompanying tuba fragment is stabilized even earlier, with repeats reaching the duration of sixteen quarter-note beats. Something of a resolution is thus forged as the two dance movements in question draw to a close. Alignment and harmonic coincidence are stabilized, with the disruption of the earlier bars (Adorno's "shocks") capable of being heard and understood as part of a larger plan of action, one with a beginning and an end. Far from being iso- lated and isolating, the disturbances may be reconciled within a larger, evolving structure.

More specifically, at rehearsal no. 70, the final placement on the sec- ond quarter-note beat of the 4/4 bar line may be heard and understood as the "correct" reading of the horn fragment A-D-C-D. In turn, earlier alignments on the fourth, first, and third beats, respectively, may be read as displacements. Crucial here is the fragment's concluding pitch D and the agogic accent of this pitch. The final placement on the second quar- ter-note beat allows D to fall on the downbeat of the 4/4 bar line, and in this way to acquire the metrical acknowledgment and support withheld from earlier repeats at rehearsal nos. 64-70. This, too, may contribute to the sense of resolution at rehearsal no. 70. It is as if, after much trial and error, the horn fragment had finally stumbled into place, finding the met- rical location from which a maximum degree of stability could be derived.

Indeed, displacements in Stravinsky's music are not typically as dis- ruptive in their potential as the ones cited in Example 1. Examples 5a-c show thematic statements from three works of the Russian era. Each of these statements consists of a displacement, whether notated or concealed by the radical notation; a short motive falls first on and then off the likely tactus, the half-note beat in Example 5a, the quarter-note beat in Examples 5b and 5c. And despite the shallowness of the location and the disruptive potential (the degree of location is 0 in all three cases), a conservative reading is likely to fare with little resistance, with the displacements read as a form of syncopation.

This content downloaded from 78.104.70.246 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 04:30:11 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Stravinsky, Adorno, and the Art of Displacement 491

E1211 radical (notated)

1 t7 1 r >R

conservative

,r 7 r r r r r ,

Example 5a. Thematic Statements. Stravinsky, The Rite of Spring (1913), autograph.

conservative (notated) 7

radical 7

Example 5b. Thematic Statements. Stravinsky, Les Noces, IV (1917-23).

radical (notated) 7 ,

> > > ~ x--

ip1 18I v 1? ?1 I v l? F T -- v I

conservative 7

tt F If f 1 f e^ ^F Example 5c. Thematic Statements. Stravinsky, Symphonies of Wind Instruments (1920; 1947 version).

There are qualifications, no doubt. In Examples 5a and 5c, not only are the displaced repeats concealed by the radical notation (which retains a single, fixed alignment for the repeated fragments), but the repetition is also somewhat shortened. In Example 5c, the motive D-D-D-B is shortened to D-D-B. And instead of a series of displacements, there is but one immediate shift. Yet the radical resistance to a conservative reading is still

likely to be minimal. The evidence can still seem to be tipped heavily in favor of the effect of syncopation. And this has mainly to do with the

strength of the meter that may be inferred in each case. In Example 5c from the opening of the Symphonies of Wind Instruments, the 2/4 meter of

:-L :1- A l

This content downloaded from 78.104.70.246 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 04:30:11 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

492 The Musical Quarterly

the rebarred, conservative reading is above all a product of the bell-like repetition of the pitch D in the opening bars. The regularity of this attack- pattern could not have been more forceful in this respect.56

In fact, the displacements in Examples 5a-c are more likely to be binding than disruptive. The syncopation is likely to allow for a smoother and more continuous connection between the motives and their subsequent repeats. With the initial spans of the three motives reduced to seven beats (see the brackets in Ex. 5a-c), the repeats arrive "too soon" and may actu- ally have the effect of increasing the listener's anticipation of the bar line. The reduced and irregular spans are a part of a process of compression.

Examples 6a-d show an analysis of the opening statement of the Symphonies alone. Example 6a reproduces the notated barring of Example 5c; Example 6b rebars the statement conservatively with a steady 2/4 meter, exposing the displacement concealed by the irregular barring (the motive [D]-D-D-B falls first on and then off the quarter-note beat); Example 6c eliminates the displacement by adding an eighth-note beat to the initial span (expanding the span from seven to eight quarter-note beats); and Example 6d eliminates both the displacement and the shortening of

a) radical (notated)

=72 7 clf f f-f f. 1 1 JC C l.

b) conservative (rebarred)

c) 8

4gF f f |f f?T h -1 .

d) r 8

,i2 f 1^ l 1ii 294;

f~itl~ f

4, ?

Example 6a-d. Stravinsky, Symphonies of Wind Instruments, opening.

This content downloaded from 78.104.70.246 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 04:30:11 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Stravinsky, Adormo, and the Art of Displacement 493

the repeat. With the repetition of the bell-like motive stripped of its invention in this way, something of the nature of that invention is revealed. The displacement of the motive may be heard and understood as a departure from an underlying stereotype, a variation in this respect. Sig- nificantly, too, at the end of the thematic statement at m. 6 (see Exx. 6a and 6b), the conservative reading arrives "on target" with the radical notation, a point of intersection that is likely to enhance the sense not only of a downbeat, but of an arrival as well. The pitch D returns at this point, with E likely to be interpreted as a metrically accented neighbor note. The syncopation of the repeat can heighten the listener's sense of anticipation as the thematic statement as a whole draws to a close.

Indeed, why not interpret the displacements in Examples 5a-c as variations (even as developing ones), metrical alignment itself as a feature of the motive along with other such features identified in Schoenberg's Fundamentals of Musical Composition?57 Conservative responses would seem to invite such a consideration, in any case, the idea of a motivic profile followed by its variants (displacements, in this case). The psychol- ogy of the conservative response would seem to correspond to that of the motive and its apprehension: reading through the displacement of a motive as it relates to an earlier alignment, listeners are likely to be struck above all by the change or relationship itself, not necessarily by the alignments considered separately or in an idealized adjacency or juxtaposition. Something of the transformation itself is sensed automatically (effortlessly), and this is what is likely to excite and to direct their attention conservatively. In these respects, the experience is little different from what we know of the phenomenology accompanying the perception of more traditional motivic relations.58

No doubt, there are qualifications here as well. In a lengthy study of metrical nonparallelism and the varied repetition of motives in traditional, tonal contexts, David Temperley has compared the difficulties of the former with the fast, automatic way in which ordinary motivic relation- ships are assimilated.5 When reinforced metrically by parallelism, motivic relationships "tend to be detected automatically," he concludes, while, when not so enforced, they tend to be detected "only with difficulty" if at all.60 J. A. Fodor's theories of perception are invoked as a means of explanation, the idea being that the detection of nonparallel relationships is "non- modular" in character; that of parallel relationships, "modular."61

Yet the analogy with ordinary motivic variation is difficult to dispel. In the listener's attempt to read through the displacement of a motive as it relates to an earlier placement (doing so by sustaining the meter against the forces of parallelism), it would indeed seem as if he or she were attempting to read through the displacement as a variation or modification.

This content downloaded from 78.104.70.246 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 04:30:11 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

494 The Musical Quarterly

Attempts of this kind are difficult to explain in terms other than these. The displacement is read through motivically, in other words, as if metrical placement were indeed a feature of the motive. And to interpret a dis- placement conservatively in this way would indeed seem to be to interpret it motivically.

With Adorno's negative account of disruption generally, however, the concern is less with the variety of displacements in Stravinsky's music and the severity of the disruption than with the nature of the experience itself. If meter is a "mode of attending," as one theorist has claimed,62 a way of focusing the listener's attention, what are we to make of its disrup- tion? If there is satisfaction in letting go, in giving up and breaking away for a time (allowing, radically, for the regularity of a higher level of pulsa- tion to take effect), what of the initial confusion of displacement, the disorientation into which, with varying degrees of intensity, the listener may be plunged?

Theorists engaged with perceptual/cognitive issues have long stressed the emotional arousal that expectation can bring when inhibited or interrupted. And it has been some time now since Leonard Meyer first began discussing the affective experiences that "the deviation of a particu- lar event from the archetype of which it is an instance" can cause.63 Surely the disruption of an established meter fits behavior of this kind.

At the same time, however, the larger psychological and aesthetic question has to do not with arousal as such, not with the state of alertness to which the listener may be propelled, but with the nature of the emo- tions stirred in one way or another. Are Stravinsky's displacements and the disruption they can cause traumatic and psychologically damaging, as Adorno insists, or can they be "exciting" and a "delight," as Meyer contends in his description of implication and delay more generally?64 And if displacement can be a "delight," why should this be? Why should listeners of Stravinsky's music be attracted to processes of displacement that disrupt their metrical bearings?

Not just meter but meter internalized is the subject of the disruption. That to which meter attaches itself physically is affected and, in this way, brought to the surface of consciousness. (As we have suggested, even if the source of the disturbance is not known at first, it is likely to be sensed and felt all the same.) And this may be what alertness is, of course: the heightened sense of engagement brought about by disruption. By means of disruption, we are brought into closer contact with what we are internally, so to speak, with what we are, deep, down, and under.

Meyer's theory of arousal in music was derived in large part from John Dewey's "conflict theory" of human emotion.65 The idea here was that emotion in music arose from the same general set of circumstances,

This content downloaded from 78.104.70.246 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 04:30:11 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Stravinsky, Adoro, and the Art of Displacement 495

namely, from the blocking of expectations, implications, or tendencies. Accompanied by a belief in the eventual resolution of the conflict (or clarification of the ambiguity), the inhibition, blockage, or arrest had the effect of heightening a sense of anticipation and suspense.66 "Delay plea- sures play," Meyer reasoned.67 "Expectation and reverie" could indeed be imagined as being "better than actuality."

In much music of the nineteenth century, delay can seem to have taken on a life of its own. The ways in which completion or closure is averted, suspense sustained, can seem to have grown ever more elaborate, and from both a harmonic and melodic standpoint. In poetic terms, the outwardly fragmentary and incomplete nature of much music of this period can be identified with a yearning that is endless, "longing eternally renewed," as Charles Rosen has expressed it in his discussion of the open- ing song of Schumann's Dichterliebe.68 The emphasis on the purely negative side of pleasure ("negative pleasure," as some have termed it)69 can seem sadistic or sadomasochistic as well. Pleasure is derived from the inhibition or blockage itself, the pain of want and desire, in other words, the withholding of a sense of arrival, completion, resumption, or release. Adorno himself acknowledged the "sadomasochistic" strains in Stravin- sky's music,70 in the composer's "perverse joy in self-denial," and in the shocks of his metrically displaced accents.71

Implications of this kind have doubtless been a part of music in the Western art tradition since, at the very least, the dawn of tonality itself. And there has been no dearth of acknowledgment. Heinrich Schenker likened the circuitous routes of his linear progressions to real-life experi- ences of "obstacles, reverses, detours, retardations, interpolations, and interruptions";72 famously, the half-cadence at the close of an antecedent phrase was dubbed an "interruption" in the progress of such a progres- sion.73 In recent studies of the psychology of anxiety, emotions have been identified more generally as "interrupt phenomena" that arise from the "interruption (blocking, inhibiting) of ongoing, organized thought or behavior."74 More specific versions of this equation involve not one but simultaneously aroused and conflicting tendencies.

Here, of course, the fit could not be tighter. Settings of metrical displacement in Stravinsky's music involve the opposition of irreconcil- able forces, those of meter and metrical displacement on the one hand, metrical parallelism on the other. To inhibit, arrest, block, delay, or interrupt one of these forces (an "ongoing thought or behavior") is to stir the emotions. To displace a repeated theme, motive, or chord metrically is to thwart implications of parallelism and to disrupt the meter. It is to invite the "convulsive blows and shocks" to which a sizable portion of Adorno's more specific criticism is directed.

This content downloaded from 78.104.70.246 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 04:30:11 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

496 The Musical Quarterly

And so the question arises: if interruption and inhibition can be an accepted and even expected part of the listening experience of the tonal (or atonal) repertory to which Adorno adheres, why can it not be of the experience of Stravinsky's music? Even if we grant the distinction in application-the emphasis on pitch structure in the tonal repertory, on rhythm and meter in Stravinsky's-the processes substantiate the same general psychology. Moreover, metrical disruption is not unique to Stravinsky's music. The disruption is less relentless in tonal works, as well as less immediate. There are fewer displacements, which in turn tend to be confined to less immediate levels of metrical pulsation, specifically to the bar line and above. Crucially, too, conflicting alternatives to meter and its continuation tend to surface in the form of alternative meters, ones that are often hemiola-related, while in Stravinsky's music alterna- tive meters of this kind are seldom an option, the conflict materializing in the form of an outright disruption or interruption of a prevailing scheme. A series of displaced repeats is invariably patterned and regular in earlier contexts, while in Stravinsky's music it is often highly irregular (as it is in the passage from The Rite of Spring quoted in Ex. 1). And the repetition is far less literal in earlier settings; motives are transposed and varied melodically and harmonically as part of a more extensive process of developing variation.

In the opening theme of the "Minuet" in Mozart's Eine kleine Nachtmusik, K. 525 (see Ex. 7a), a rising two-note motive, straddling the 3/4 bar line at mm. 1-2 and 2-3, is displaced at m. 3.

(derivation)

a J)

9: x , r7T rrT~i~ J~ rr F r ~-r RLE

Example 7a-b. Mozart, Eine kleine Nachtmusik, Minuetto.

I I I I

This content downloaded from 78.104.70.246 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 04:30:11 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Stravinsky, Adorno, and the Art of Displacement 497

In the consequent phrase at mm. 5-7, the same motive, entering once again on the third quarter-note beat of the 3/4 bar line, is subjected to a cycle of displacement as part of a hemiola cadence (see the brackets in Ex. 7a). (Hemiolas in traditional contexts are often punctuated in this way by cycles of displacement.)75 In the "Preambule" from Schumann's Carnaval, another two-note motive, starting on the downbeat in the left hand of the piano part, runs through two full cycles of displacement (see the brackets in Ex. 8).76

And in Example 9, from the second movement of Brahms's Piano Quartet, op. 25, no. 2, a thematic phrase introduced and repeated on the third dotted quarter-note beat of the 9/8 meter (the likely tactus; see Ex. 9a) is subsequently displaced to the second beat (Ex. 9b) and to the first (Ex. 9c).

In this third illustration, the displaced repeats do not make for an immediately patterned sequence, as they do in Examples 7a and 8. Yet they exemplify large-scale development all the same.77 The ambiguity of the tonic harmony over the bar line at mm. 1-2 (see Ex. 9a; the pitch B on the downbeat is most likely nonharmonic) is clarified by the motive's subsequent displacement to the second beat of the 9/8 bar line (see Ex. 9b), a variation accompanied in turn by a modulation. Accordingly, extensive melodic and harmonic changes accompany the metrical dislocation, serv- ing in this way as a form of mediation. There are mitigating circumstances, in other words, with metrical alignment, but it is one of many features affected in a more comprehensive process of development.

In all three of these examples, the repetition, apart from the dis- placement itself, is far from literal. The motive is transposed and subjected to a variety of melodic and harmonic changes, all in keeping with an overreaching pattern of development and growth. In Example 7a, the cycle of displacement in the consequent phrase of the theme is a further development of the earlier motivic occurrences at mm. 1-2 and 2-3. More specifically, the earlier occurrences are compressed. As can be seen by the Schenkerian graph in Example 7b, the cycle defines a descending-third

II. 1

ib _

sf sempre ff sf sf sf sf

I I I II I J Ib I I J II I I

Example 8. Schumann, "Preambule," Carnaval.

This content downloaded from 78.104.70.246 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 04:30:11 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

p dolce ed espress.

n<^^bbaW :? fr r r ~r ^f rf ^r ri moltop dolce ed espress.

: [,,r rr r rrr rrrrrrrrr rr Lr rr r

b)

@ bl'l, , ? y t^; f 4;

'

4 pp dolce

i* Y

c)

147

| ,, ~ . ~ br -

I ^J . . r r r. i' p dolce espress.

|#tbb? #r $: r 1r. b 5 r r' f Tr 7- f pp olce

r T "r f f ' y

pp dolce

Example 9a-c. Brahms, Piano Quartet, op. 25/II.

progression from scale degree 3 to 1, a B-A-G passing motion that, inter- rupted by the half-cadence of the antecedent phrase, is completed by the consequent. The descriptive terms here are in themselves reflective of the larger distinctions that can be brought to bear.

At the same time, however, and notwithstanding differences of this kind, the many points of overlap cannot be ignored. Processes of implica- tion, inhibition, and delay are as much a part of Stravinsky's displacements as they are of the world of developing variation. As we have seen, significant overlapping occurs even in matters of metrical displacement. The effect of syncopation that typically accompanies hemiola patterns such as those illus- trated in Examples 7a and 8 may accompany Stravinsky's displacements as well. Displacement, read conservatively, can be read motivically, in other

498 The Musical Quarterly

a)

I

Violin

Viola

Cello

Piano

Violin

Viola

Cello

This content downloaded from 78.104.70.246 on Fri, 6 Dec 2013 04:30:11 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Stravinsky, Adorno, and the Art of Displacement 499