Non-face-to face international business negotiation : how is national culture reflected in this medium? Citation for published version (APA): Ulijn, J. M., Lincke, A., & Karakaya, Y. (2001). Non-face-to face international business negotiation : how is national culture reflected in this medium? IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 44(2), 126-137. https://doi.org/10.1109/47.925516 DOI: 10.1109/47.925516 Document status and date: Published: 01/01/2001 Document Version: Publisher’s PDF, also known as Version of Record (includes final page, issue and volume numbers) Please check the document version of this publication: • A submitted manuscript is the version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can be important differences between the submitted version and the official published version of record. People interested in the research are advised to contact the author for the final version of the publication, or visit the DOI to the publisher's website. • The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review. • The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and page numbers. Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. If the publication is distributed under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license above, please follow below link for the End User Agreement: www.tue.nl/taverne Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us at: [email protected] providing details and we will investigate your claim. Download date: 14. Feb. 2022

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

Non-face-to face international business negotiation : how isnational culture reflected in this medium?Citation for published version (APA):Ulijn, J. M., Lincke, A., & Karakaya, Y. (2001). Non-face-to face international business negotiation : how isnational culture reflected in this medium? IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 44(2), 126-137.https://doi.org/10.1109/47.925516

DOI:10.1109/47.925516

Document status and date:Published: 01/01/2001

Document Version:Publisher’s PDF, also known as Version of Record (includes final page, issue and volume numbers)

Please check the document version of this publication:

• A submitted manuscript is the version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can beimportant differences between the submitted version and the official published version of record. Peopleinterested in the research are advised to contact the author for the final version of the publication, or visit theDOI to the publisher's website.• The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review.• The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and pagenumbers.Link to publication

General rightsCopyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright ownersand it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights.

• Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal.

If the publication is distributed under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license above, pleasefollow below link for the End User Agreement:www.tue.nl/taverne

Take down policyIf you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us at:[email protected] details and we will investigate your claim.

Download date: 14. Feb. 2022

126 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON PROFESSIONAL COMMUNICATION, VOL. 44, NO. 2, JUNE 2001

Non-Face-to-Face InternationalBusiness Negotiation: How isNational Culture Reflected in thisMedium?

—JAN M. ULIJN,ANDREAS LINCKE,AND YUNUS KARAKAYA

Abstract—With the globalization of the world economy, it isimperative that managers, both present and future, be sensitive todifferences in intercultural business communication. In particular, thecontext of global electronic commerce leads to an increasing use ofemail in negotiating deals, which to this point has been carried outalmost exclusively via face-to-face (FTF) or other high-feedback media(e.g., telephone) but not of non-FTF media. This study, involving 20participants, uses speech act theory and psycholinguistic analysis toexplore the affects of culture on non-FTF communication.

Index Terms—Culture, face-to-face (FTF) communication, negotiationstrategy, non-FTF communication, personal pronoun usage, speechact analysis.

Manuscript received September 21, 2000;revised March 16, 2001.J. M. Ulijn is with theDepartment of Organization Science,Eindhoven University of Technology,5600 MB Eindhoven,The Netherlands(email: [email protected]).A. Lincke and Y. Karakaya are withFaculty of Economics,Darmstadt University of Technology,64289 Darmstadt, Germany(email: [email protected];[email protected]).IEEE PII S 0361-1434(01)04470-8.

With the globalization of theworld economy, it is imperativethat managers, both presentand future, be sensitive todifferences in interculturalbusiness communication. Inparticular, the context of globalelectronic commerce leads toan increasing use of email innegotiating deals, which tothis point has been carried outalmost exclusively via face-to-face(FTF) or other high-feedbackmedia (e.g., telephone) but not ofnon-FTF media, such as email.The increasing popularity ofe-commerce between businesspartners has not only broughtabout a new economy aroundthis innovation in businesscommunication, but also thepossibility to bring differentnational cultures together vialow-cost email negotiation. Thequestion remains, however, as towhat extent non-FTF media cansupport intercultural negotiation?

This study provides a brief reviewof current non-FTF researchand tries to address, through asimulated study, the question ofwhether non-FTF communicationcan support the discourse ofeffective negotiation amonginternational business people.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The creation of virtualorganizations brings specificconsequences for communication(as outlined in the recent specialissue of this journal edited byEl-Shinnawy [1]). Specifically,non-FTF communication, likeemail, becomes more importantas technology shrinks the world,bringing multiple culturesinto virtual relationships, andincreases global communicationand business opportunities.

In a literature survey of Americanstudies comparing the use ofmedia in negotiation (such as

0361–1434/01$10.00 © 2001 IEEE

Authorized licensed use limited to: Eindhoven University of Technology. Downloaded on October 30, 2009 at 09:46 from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply.

ULIJN et al.: NON-FACE-TO-FACE INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS NEGOTIATION 127

FTF, text, audio, video, decisionsupport system, and electronicconference), Poole et al. report thatout of 28 situations, FTF contactwas considered superior to othermedia in only two instances [2]. Onthe other hand, FTF is perceivedas the best medium for negotiationby lay people despite the fact thatthis medium may also personalizeconflict. Poole et al. conclude that,while new media are perceived tobe overwhelmingly beneficial, threeof their characteristics may beharmful, especially in negotiation:• they reduce time spent on

listening;• they are physically demanding

and tiring; and• they encourage rigid positions.

In education, new media such asemail have become an importanttool. Both the studies by Zhiting[3] and Vogel et al. (see this issue)[4] show that educational software,if used in an international context,requires special cultural andcommunicative considerationbecause teaching and learningstyles vary across cultural borders,especially between the Westand the Far East. Patterns ofcommunication, to say nothingof values, are deeply rooted inlanguage–culture complexes.Understanding these patterns canbe facilitated by technology, asfor example in the internationalbusiness writing course involvingFinns, Belgians, and Americans[5]. Because today’s business ortechnical students are tomorrow’sbusiness negotiators, we requiremore sophisticated knowledgeof discourse conventions andculture in new media such asemail in order to provide studentswith negotiation skills for the21st century. Not surprisingly,readers of this journal rankedthe importance of specializeddiscourse media and types ofcommunication as the thirdmost important research topic inprofessional communication—afterreading/writing andcollaborative/organizationalprocesses [6]. Computer-mediatedcommunication was recognized

as part of the required agenda forteachers and researchers by Lovittand Goswami when they exploredthe rhetoric of internationalprofessional communication [7].Moreover, doctoral research intechnical, scientific, and businesscommunication between 1992and 1997 included 13 Ph.D.dissertations devoted to differentaspects of computer-mediatedcommunication, including culturaland communicative issues [8].

Specht’s interviews of 24German software experts innine business units of a companythat operates in four countriesranks email, together withopenness of communication,as second and third of the top10 overall success factors ininternational outsourcing ofsoftware development [9]. Butwhat is the potential of non-FTFmedia, like email, for negotiationstrategy development? The basicstrategic problem in negotiationseems to be involvement. Mostnegotiation models and theories[10]–[13] agree that the long termof cooperation in a win–win spiritwith effective relationship buildingis the best option. This requiresa high degree of involvement, ashas been recognized, for instance,in the case of home mortgage ratenegotiations and automobile sales[14].

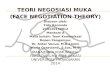

How does one develop a positiveclimate, equal power distribution,and flexible procedure usingnon-FTF media like email? Fig. 1presents a model for such asituation in two dimensions:fighting (win–lose) versuscooperation (win–win) andavoiding (including walking away)to exploring all options to come toan agreement.

What impact would non-FTFcommunication have on suchwin–win strategy? Would itfreeze positions of parties inhigh involvement situations,as Hobson seems to suggest[14]? Hobson uses Fisher andUry’s [10] integrative (win–win),

distributive (win–lose) and BATNA(Best Alternative To a NegotiatedAgreement) concepts to examinethe role of context and power inemail negotiations, for instancein online auctions. The attractionof persisting in “tit for tat” leadsoften to the easy BATNA wherenegotiators decide to walk away ifthey cannot get what they want inthe short term.

To date, there appear to be fewstudies that trace back suchstrategies of cooperation versuscompetition via linguistic analysis.Donnellon [12] presents aninteresting outline of pressure ofindividual preferences on teamswhich can be used in internationalbusiness negotiations as welland is relevant to both researchquestions. Individuals uselinguistic forms to identifythemselves in teams or as ateam, to show independenceor interdependence, low orhigh power, social distance,conflict management tactics,and win–win/win–lose strategiesof negotiations. This latteraspect is related closely to ourinterest in cooperation versuscompetition. Another possibleexception might be Ulijn andVerweij’s study on uncertaintyreduction behavior of experiencedSpanish and Dutch negotiators[15]. That study verified a majorcommunication strategy via theidentification and classificationof 480 questions in linguistictranscripts of negotiations: askingquestions of all kinds appeared tobe a critical success factor in bothmonocultural and interculturalsituations. We do not know howwell this strategy might work fornon-FTF communication, sincequestions cannot be immediatelyanswered within this medium.

The cooperation and explorationstrategy in negotiation requiresa strong involvement in theother party’s concerns. Johnsonet al. [16] pinpoint that suchinvolvement is important forcommunication of technicalinnovations between experts and

Authorized licensed use limited to: Eindhoven University of Technology. Downloaded on October 30, 2009 at 09:46 from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply.

128 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON PROFESSIONAL COMMUNICATION, VOL. 44, NO. 2, JUNE 2001

to the community, but the effect ofnon-FTF media in attaining suchinvolvement was not yet verified.Linguistic indicators were usedby Collot and Belmore [17] torank-order 25 genres (e.g., FTF,telephone, email, etc.) relative toinvolvement and informativeness.Those indicators include first-(e.g., we) and second-person(e.g., you) pronouns, contractions(e.g., it’s), hedges (e.g., could),and amplifiers (e.g., very). Basedon these indicators, FTF wasrated higher in involvement thanonline chat, which was alsorated less narrative and moreabstract, but more persuasivethan FTF. Effective negotiationwould probably require persuasiveand less narrative, but also moreconcrete and involved speech.Relationship building serves thisinvolvement and appeared to bemore difficult over email for the 78American management studentsthan FTF since there were moreoffers and fewer questions [17].Higher personal disclosure ledto a higher joint outcome andfewer impasses than did avoidingand nondisclosure behavior [18].The ideal rank order of personal

pronoun use in negotiation mightthen be (1st) you, (2nd) we, (3rd) I,and (4th) it or they.

Two studies provide evidence thatcontext is what makes interactionconcrete and involved. In thefirst study, researchers analyzedthe use of email by secretarialand administrative staff of theUniversity of Queensland inAustralia over a three-monthperiod [18]. This study investigatedpersonal language style, suchas politeness markers, reducedsubject-matter representation(more abstract style), and absenceof metalanguage. In the secondstudy, Murray investigatedspeech acts in email dialogues[19]. Both studies support theabove empirical evidence that anemail interaction requires morecontext (as measured via concrete,personalized style using politenessmarkers and metalanguage) toget the other party involved thanFTF or even telephone interaction.Again, the effect of missingcontext in non-FTF negotiation isuncertain.

As has been shown by the work byHall [20], [21], the degree of context

required is culturally sensitive,ranging from low context cultures,such as Anglo and Nordic, tomedium context cultures, such asLatin American, to high contextcultures in Far East cultures,symbolized in the onion modelby Hofstede going from the lowcontext outer layer to the veryhigh context deepest layer ofcultural programming (Hofstede[22]). Possible consequences forcommunication behavior havebeen outlined by Ulijn and Kumar[23]. We do not, however, knowthe impact of context levelson non-FTF communication. Acontext-reflecting culture (high)would need less language todisambiguate context, whereasa context-creating culture wouldrequire more.

Non-FTF communication, likeemail, can equalize people (e.g.,it is more difficult to expressstatus using standard forms, asrequired in some Latin contexts,over email). Such equalization,however, may contradict Latinand Oriental cultural values. Ma[24] was able to confirm some ofthose elements in his interviewwith 18 U.S. and 25 East Asian

Fig. 1. Successful negotiation strategy: Fighting versus cooperating and avoiding versus exploring.

Authorized licensed use limited to: Eindhoven University of Technology. Downloaded on October 30, 2009 at 09:46 from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply.

ULIJN et al.: NON-FACE-TO-FACE INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS NEGOTIATION 129

students about their experiencesin using computer-mediatedcommunication with each other.East Asians judged that they weremore direct and self-disclosing,but the U.S. students thought thatthe Asians were polite, reserved,indirect, and did not talk aboutthemselves over email.

Mutual perception is crucialin such encounters becausecorrespondents cannot see eachother (see Ulijn and St. Amant[25] for the effect of this in aChinese–Dutch FTF businessnegotiation). If a Chinese studentsays: I can’t stay on relay for toolong during a relay chat to turnan invitation to a private channel,this statement would be perceivedas explicit and rude by a FarEastern student but as beatingaround the bush by a NorthAmerican. But computer-mediatedcommunication also seems tobe seen by East Asians as rare,worry-free, and involving littlerisk. Therefore, it is uncertainwhether new media wouldreally contribute to a seriousinterpersonal relationship leadingto business involvement in Asians’perception in the same way FTFinteraction does.

In this study, we limit ourlinguistic check on simulatednon-FTF negotiation to threespecific cultures with respectto two research questions thatexplore two major aspects ofnegotiation strategy that are dealtwith in a non-FTF setting:

RQ1: Cooperation versuscompetition—How does simulatednon-FTF communicationcontribute to a win–win strategy innegotiation?

RQ2: Involvement andmedium—How does simulatednon-FTF communication affect theparticipants’ ability to empathizewith each other?

The answers to both researchquestions might be affectedby important variables in

(international) negotiations, suchas national culture, seller/buyerroles, and gender. RQ1 is tooqualitative in nature to test thoseeffects, but RQ2 allows us totest seven specific hypotheseson this matter. Our methods foraddressing these questions arediscussed in the following section.

METHODS

This study is an attempt to test anegotiation strategy by linguisticmeans. In their psycholinguisticanalysis of the technical andbusiness communicator, Ulijnand Strother [14] argue thatlinguistic analysis can be used, inboth written and oral negotiationsituations, to provide evidence ofthe effectiveness of communicationstrategies if the experimentalsetting meets some design andbusiness relevance requirements.Specifically, in contrast toother deductive, descriptive,ethnographic speech act analyses,this study attempts to applythe quantitative methods offormulating and testing researchquestions in the hope of increasingthe reliability and validity of thespeech act analysis.

A simulated buyer–seller case,called “ALYK,” was developed bythe second and third authors togather data from 20 students inthe first author’s “InternationalBusiness Negotiation” class. Thesimulation was planned for theend of the semester to evaluate thesuccess of the course objectives asstated in the research questions.The simulation was designedto mimic interactive non-FTFcommunication. As part of thesimulation, participants wereasked to negotiate the terms of abusiness deal, where they had toplay either the role of a seller ora buyer. Specifically, participantswere instructed to write downtheir statements on a blanksheet of paper and hand it to theopponent. Speaking to each other,gestures, laughing, shaking hands,etc., was not possible becausethe participants did not know

with whom they were negotiating(although they did know each otherfrom class). These restrictions weregiven to simulate the nonpersonalatmosphere of written, non-FTFcommunication, like email.

The participants represented threedifferent cultural backgrounds:Anglo (North American), Nordic,and Latin (European) and wereplaced in a monocultural andan intercultural setting. Wemade an attempt to rule outgender and buyer/seller rolebias and to keep independentvariables such as mono- andintercultural dyads under controlas much as possible within theconstraints of an interculturalnegotiation class (Tables I andII). In sum, half of the simulatednegotiations were interculturaland half monocultural, of whichtwo involved participants of thesame nationality. It is important tonote that five of the 20 studentshad professional experience.

The exact terms to be negotiated,as quoted from the experimentaltask, were:

Task: Seller wants to sellcomputers for the below mentionedconditions:

Price per computer: $1650–$2000.

Delivery time: 30, 60, 90 days.The aim of the seller is to deliveras late as possible. The aim of thebuyer is to get delivery as soon aspossible.

Payment conditions: 30, 60, 90days after delivery. The aim of theseller is to get paid as soon aspossible. The aim of the buyer is topay as late as possible.

Since there are obvious collidinginterests in each negotiation, theseinterests have to be balanced.Therefore, one seller and onebuyer have to negotiate the deal.Imagine that buyer and seller arefar away from each other and

Authorized licensed use limited to: Eindhoven University of Technology. Downloaded on October 30, 2009 at 09:46 from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply.

130 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON PROFESSIONAL COMMUNICATION, VOL. 44, NO. 2, JUNE 2001

communicating via Internet relaychat.

Participants were given 15 minutesto negotiate the terms of the deal.From the 20 participants, wereceived 10 usable negotiationtranscripts. The combined text ofmost of the simulations containedone page of written statements.The negotiation almost alwaysbegan when the buyer stated hisor her interest in purchasing somecomputers from the computerdealer. Introductions were rare. Adiscussion and mutual statementof objections, suggestions,and explanations were mostcommon steps toward reachingan agreement. Disagreements orpartial agreements to suggestionswere followed by explanations ofthe negotiators’ positions. Thegeneral discourse was aboutthe facts and terms of the deal.Further proposals for a long-termrelationship were also made soboth the seller and the buyer couldbroaden the discussion base.

To explore both of ourresearch questions, we usedpsycholinguistic analysis toidentify cooperative attitude(including its lack) andmetacommunicative behaviorto verify the involvement ofthe negotiation parties on thebasis of the nonpublishedcluster-factorized list of Vander Wijst and Noordman [26]quoted by Ulijn and Strother[13]. Our methods relate tothe findings by Condon andCech [27], who comparedFTF with computer-mediateddecision-making interactions

and ascertained a three timeshigher use of metalanguage in theelectronic condition to stimulatesocializing at a distance. Electronicdiscourse seems to be situatedbetween the purely oral andwritten modes of communication.A linguistic analysis by Werry [28]indicated that Internet RelayedChat (IRC) is shaped at manydifferent levels by the drive toreproduce and simulate thediscursive style of FTF spokendialogues.

The transcripts of our simulatednegotiations were categorizedinto four clusters of speech actsfor each turn identified in thetranscripts of the 10 negotiationinteractions:

• Noncooperative Behavior(N): i.e., criticize, deny,disapprove, object, reject,show indignation, irritation,etc.

• Cooperative Behavior(C): i.e., admit, approach,be forthcoming, confirm,inspire confidence. emphasizecooperation, show goodwill,etc.

• General Speech Acts (G): i.e.,ask (for understanding,confirmation, information),explain, request, stipulate,suggest, etc.

• Metacommunicative SpeechActs (M): i.e., conclude,close, engage, offer, promise,propose, remind, repeat,resume, specify, etc.

For illustration purposes, thetranscript of one negotiation after

speech act categorization appearsin the Table II.

Personal pronoun analysishas been used to identifyinvolvement and empathy. Yates[29] compared computer-mediatedcommunication with the writtenand spoken modes. For electroniccommunication, the first personpronouns (I, we) were used most,followed by the second personpronoun (you). In contrast, inemailed negotiation the thirdperson pronoun (s/he, it, they) wasused much less. The predominantuse of the first person pronounhas been confirmed for a corpusof 115 618 words of electronicEnglish language by Collot andBelmore [17]. Their findings werecomparable in frequency of usewith Biber’s corpus of one millionwritten and 500 000 spokenEnglish words in which the useof the first person pronoun wastwice as frequent in the ElectronicLanguage Corpus, with the useof third person pronouns equal.Unfortunately, the use of thesecond person pronoun was notanalyzed. It will be possible tocompare our findings with thosetwo studies.

Applying this earlier work by Yates[29] and Collot and Belmore [17],we identified all personal pronounsin the transcripts of the simulatednegotiations as a measureof involvement and empathy.Because of the small scale of thesample and potential differencesin languages, a nonparametricstatistical interference analysiswas used to analyze personalpronoun use [30]. Since most of

TABLE IDISTRIBUTION OF SIMULATED NEGOTIATION SUBJECTS BY NATIONAL

CULTURE, GENDER, AND PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE

Authorized licensed use limited to: Eindhoven University of Technology. Downloaded on October 30, 2009 at 09:46 from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply.

ULIJN et al.: NON-FACE-TO-FACE INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS NEGOTIATION 131

our samples comprise one sheetof written text (the negotiationtranscript) and the participantsonly had 15 minutes of time, weassume that the average usageof pronouns is symmetricallydistributed around a mean value.Therefore, the Wilcoxon rank sumtest (as part of SPSS, a standardsocial sciences software package)could be used because it canbe considered a nonparametricequivalent of the unpaired t-test. Itis used to test the hypothesis that

two independent samples havecome from the same population.Because it is nonparametric, itmakes no assumptions about thedistribution of the data.

RESULTS

We begin our discussion in thissection by focusing on the tworesearch questions posed earlier.

Cooperation VersusCompetition In this section,

we address our question: How doessimulated non-FTF communicationcontribute to a win–win strategy innegotiation? (RQ1). Fig. 2 presentsthe distribution of the total of187 speech acts found in the 10simulated negotiation transcripts.

The balance between cooperativeand noncooperative behavior (e.g.,as indicated by the use of confirmor inspire versus reject or deny)and between general (as indicatedby the use of ask or request)

TABLE IISAMPLE ANALYZED NEGOTIATION TRANSCRIPT

Fig. 2. Proportion of four speech act clusters in transcripts of a simulated negotation.

Authorized licensed use limited to: Eindhoven University of Technology. Downloaded on October 30, 2009 at 09:46 from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply.

132 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON PROFESSIONAL COMMUNICATION, VOL. 44, NO. 2, JUNE 2001

and metacommunicative speechacts (as indicated by the use ofrepeat or explain) is roughly equal.However, about two-thirds of allspeech acts were either generalor metacommunicative ratherthan indicative of negotiationstrategy (cooperative or “win–win”versus noncooperative or“win–lose”). Thus, the generaland metacommunicative speechacts were used two times morefrequently than the noncooperativeand cooperative ones. Both sets ofclusters are in balance, confirminga negotiation interactionsomewhere between fightingand cooperating with a tendencyto more win–win (see Fig. 1 again).This is in line with the objectiveof most negotiation training: inthe long run, one wins morethrough cooperation than through

competition. The predominantuse of general and, in particular,metacommunicative speech actssuggests that negotiators whowere interacting non-FTF had toexpress their involvement in thenegotiation more explicitly, thususing the language of negotiationstrategy less.

Involvement and Medium Inthis section, we address ourquestion: How does simulatednon-FTF communication affect theparticipants’ ability to empathizewith each other? (RQ2). Table IIIgives the results of the frequencycount of the three types ofpersonal pronouns in three cultureclusters distributed over sevennationalities, seller and buyerroles, and gender in our simulatednegotiations.

One can generally say thatexpressions about their ownpositions were used and objectionsto the other party were made.This means that the usage offirst and second person pronounswas quite frequent, with bothsellers and buyers using only11 instances of the third personpronouns. The overall underuse ofthe third person pronoun mightalso be the result of the nature ofthe simulation case itself, sinceit does not involve third partiesexplicitly. An additional commentfor the figure of first personpronouns is needed because thepronoun we can have an inclusive(you and I equals we) and anexclusive (me and others equalswe) meaning. This distinction isimportant because by frequentlyusing the inclusive version of

TABLE IIIPRONOUN USAGE IN A SIMULATED BUSINESS NEGOTATION BY

NATIONAL CULTURE, SELLER OR BUYER ROLE, AND GENDER ON PERSONAL

Authorized licensed use limited to: Eindhoven University of Technology. Downloaded on October 30, 2009 at 09:46 from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply.

ULIJN et al.: NON-FACE-TO-FACE INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS NEGOTIATION 133

the first person pronouns, theperson’s language indicates anatmosphere of solidarity andpoliteness and that he or shewants to bind the other entityto himself and build a long-termrelationship. By often using theexclusive meaning of the firstperson pronoun, the negotiatorindicates a more distant, notnecessarily disrespectful, positiontoward the other party. As a matterof fact, nearly every usage of thefirst person pronoun was intendedto have an exclusive meaning, evenin a multicultural environmentof the classroom, where differentcultures were represented. Thisbrings us to the conclusion thatthe earlier mentioned ideal rankorder of personal pronoun use innegotiation (1st you, 2nd we, 3rdI, 4th it, they) is not yet reached atthe end of this course.

Table IVpresents the resultsofhypotheses aboutpossiblestatisticaldifferencesbasedonpersonalpronounusage.Althoughthere isnosignificantdifferencebetweensellersandbuyers,sellersusedfewersecondpersonpronouns,whichmakes itmoredifficult forthemtoputthemselvesintheshoes

of theotherparty—animportantobjective for theseller.Moreover,theuseof inclusivewewouldallowthesamestrategyofempathyandinvolvement thantheexclusivewe that is nearly equivalentto I. Empathyor involvementbuilding inasimulatedemailednegotiationmaybepossible,butitwould requiremanygeneralandmetacommunicativespeechacts.Andstillcomputer-mediatedcommunicationmight seducethenegotiators tooveruse Iandnotan inclusiveweoraninvitingyou.Awin–winstrategythroughnoon-FTF,as it issimulatedhereinanon-FTFsettingwouldrequireadditionaltrainingtogetawayfromanegocentricbargainingposition.

We will now review the possibleeffects of national culture,seller/buyer role, and gender.

National Culture Although theparticipants are from differentcultures, the general distributionover the usage of the first, second,and third person pronouns isapproximately the same. Everyculture uses more first and secondthan third person pronouns. Amore sophisticated analysis here

is not possible because of thedifferences in sample scales (forboth the Anglo and Latin culture5 and for the Nordic culture 12).There seem to be, however, a slighttendency toward a cultural effect:Anglos (U.S. and Canada) wereusing more first person pronouns,but Nordics (The Netherlands,Sweden, and Finland) fewer firstperson pronouns than Latins(France and Colombia). BothAnglos and Latins used thesignificantly more inclusive we(Wilcoxon test at p<0.05 andp<0.10, respectively, see Table IV)and I and exclusive we (bothat p<0.10) than the two othernational culture clusters. Alwayslumping Anglos and Nordicstogether in one Anglo-Germaniccamp is not wise. The Nordicsseem to be less egocentric in thesedata, but the general order ofdescending frequency of use ofpronouns is still first, second,third, whereas the negotiationstrategy advice says: Use more youthan we, than I being indifferentto third person pronouns (second,first, third). In general, all cultureshave problems with empathy andinvolvement building through theuse of second person pronouns.

TABLE IVSIGNIFICANCE EFFECTS OF SELLER OR BUYER ROLE AND CULTURE

ON PRONOUN USE

Authorized licensed use limited to: Eindhoven University of Technology. Downloaded on October 30, 2009 at 09:46 from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply.

134 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON PROFESSIONAL COMMUNICATION, VOL. 44, NO. 2, JUNE 2001

Seller and Buyer For sellers, thetotal absolute usage of the firstperson pronoun is 56 and forbuyers 68. The average usage ofthe exclusive first person pronounsis nearly the same for both (nosignificant difference on theWilcoxon test), but for the usageof the second person pronouns theWilcoxon signed ranks-test givesa significant difference at p<0.05(Table IV). Sellers might have usedsignificantly more you to addressbuyers directly because they wantto sell. In general, both sellersand buyers have problems withempathy and involvement buildingthrough the use of second personpronouns, but sellers more so thanbuyers. This is OK if buyers acceptmore aggressive marketing, butnot when buyers have easy accessto other suppliers, such as in theALYK simulation.

Male and Female The samplesfor males and females areindependent, since the genders didnot necessarily take part in thesame simulations. Females usesignificantly more first and secondperson pronouns than males (p<0.05, Table IV). Are they moreperson-oriented than males? Thereis an indication also that for malesthe distribution between the usageof the first and second personpronouns is more balanced. Bothgenders use first person pronounsmost often instead of second orthird, but females seem to be morebiased toward the use of the firstperson pronoun. Are females moreprudent to be empathetic or to getinvolved in such depersonalizedinteraction, as in this simulation?In general, both genders inour study have problems withempathy and involvement buildingthrough the use of second personpronouns, but females seem tohave more than males.

In sum, on the basis of this pilotstudy we may state that empathyor involvement building in asimulated non-FTF negotiationis possible but needs not onlymore metacommunicative and

general speech acts, but alsomore explicitly yous and inclusivewes to realize the importantnegotiation strategy of showingempathy for other party to get awin–win deal. We would argue thatthis finding would apply to othernon-FTF negotiations, since thereal FTF would always need lessmetacomminicative acts and havemany types of nonverbal incentivesto use you, such as eye contact,gestures, and other body languagewith the possibility of immediatefeedback which is absent from anynon-FTF.

DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONSFOR FUTURE RESEARCH

On the basis of these preliminaryresults, we can surmise thatnon-FTF communication doesallow negotiators to employ acooperative win–win strategy (asrecommended by negotiationstrategy training), but that theempathy or involvement buildingrequired in non-FTF interactiondetracts from the win–win strategyby requiring an excessive andperhaps cumbersome use ofgeneral and metacommunicativeacts to compensate for the lackof the context and nonverbalcues available. The need for thismetalanguage might also drivean excessive use of first personpronouns as negotiators produceself-disclosure statements,contradicting the dictates ofwin–win negotiation strategy.In these respects, our findingssupport those of earlier studies[27], [29], [17]. In contrast, ourfindings do not corroborateHall’s [20], [21] or Hofstede’s[22] distinction between lowcontext (Anglo, Nordic) and highcontext (Latin) negotiators in thissimulated non-FTF context.

This study demonstrates thatlinguistic analysis both at thepersonal pronoun level and thespeech act level is an excellentway to test negotiation strategies.Linguistic analysis can also be amethod for identifying intercultural

effects between experiencednegotiators, as has been evidencedfor FTF in Dutch/French [26],Dutch/Spanish [13] and inDutch/Finnish/Chinese [31]business negotiations. We hopeour methods will prompt othersto test specific hypotheses forbusiness communication. Inaddition, we feel our methodssuggest a way of use non-FTFcommunication, like email, innegotiation training courses.

Our findings require verificationin well-controlled experimentalstudies to meet some obviousmethodological shortcomings.Some suggested starting points forfuture research follow.

1. Although present-daystudents are the businessmanagers/negotiators of thenear future, studies involvingprofessional negotiators areneeded to validate linguisticusage in the business world.

2. To allow a confidentmeasurement of effectsof culture on non-FTFnegotiation, adequatesampling is needed to followup the results of this pilotstudy. For instance, femaleand male negotiators shouldbe compared in the samebuyer and seller roles withmore adequate samplingthan was possible in thisstudy. In general, femalesare reputed to be betterlisteners, but the females inour sample appeared morereluctant to build businessrelationships throughnon-FTF communication.

3. Studies should compare theeffects of computer-mediatedand FTF communicationon business relationshipsfor “strangers” to ascertainwhether non-FTF is moreeffective after a relationshipis developed FTF.

4. Studies might comparesimulations where variablesare controlled with actualbusiness negotiations to

Authorized licensed use limited to: Eindhoven University of Technology. Downloaded on October 30, 2009 at 09:46 from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply.

ULIJN et al.: NON-FACE-TO-FACE INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS NEGOTIATION 135

increase ecological validity offindings.

We hope these recommendationswill lead to future work on how

national culture reflects discoursein non-FTF international businessnegotiation.

REFERENCES

[1] M. El-Shinnawy, “Communication in virtual organizations,” IEEETrans. Prof. Commun., vol. 42, no. 4, 1999.

[2] M. S. Poole, D. L. Shannon, and G. DeSanctis, “Communication mediaand negotiation processes,” in Communication and Negotiation, L. L.Putnam and M. E. Roloff, Eds. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1992,pp. 46–66.

[3] Z. Zhiting, “Cross-cultural portability of educational software: Acommunication-oriented approach,” Ph.D. dissertation, Universityof Twente, Twente, The Netherlands, 1996.

[4] D. Vogel, M. van Genuchten, D. Lou, S. Verveen, M. van Eekhout,and A. Adams, “Exploratory research on the role of national andProfessional cultures in distributed learning project,” IEEE Trans. Prof.Commun., vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 114–125, 2001.

[5] J. P. Verckens, T. DeRycker, and K. Davis, “The experience ofsameness in difference: A course on international business writing,”in The Cultural Context in Business Communication, S. Niemeier, C.P. Campbell, and R. Dirven, Eds. Amsterdam, The Netherlands:Benjamins, 1998, pp. 247–261.

[6] K. S. Campbell, “Editorial: Invitation,” IEEE Trans. Prof. Commun.,vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 93–96, 1998.

[7] C. R. Lovitt and D. Goswami, Exploring the Rhetoric of InternationalProfessional Communication: An Agenda for Teachers andResearchers. Amityville, NY: Baywod, 1999.

[8] K. T. Rainey, “Doctoral research in technical, scientific, and businesscommunication, 1989–1998,” Tech. Commun., vol. 46, no. 4, pp.501–531, 1999.

[9] G. Specht, “International outsourcing of software development,”paper, unpublished, 1998.

[10] W. T. Fisher and M. C. Ury, Getting to Yes: Negotiating AgreementWithout Giving In. New York: Penguin, 1991.

[11] W. Mastenbroek, Negotiate. Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell, 1989.[12] A. Donnellon, Team Talk: The Power of Language in Team

Dynamics. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 1996.[13] J. M. Ulijn and J. B. Strother, Communicating in Business

and Technology: From Psycholinguistic Theory to InternationalPractice. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Europaeischer Verlag derWissenschaften, 1995.

[14] C. A. Hobson, “Creating a framework for online commercialnegotiations,” Negotiation J., vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 201–218, 1999.

[15] J. M. Ulijn and M. J. Verweij, “Question behavior in monocultural andintercultural business negotiations: The Dutch–Spanish connection,”in Discourse Studies. London, U.K.: Sage, 2000, vol. 2, pp. 217–248.

[16] J. D. Johnson, W. A. Donohue, and Ch. K. Atkin, “Differences betweenorganizational and communication factors related to contrastinginnovations,” J. Bus. Commun., vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 65–80, 1995.

[17] M. Collot and N. Belmore, “Electronic language: A new variety ofEnglish,” in Computer-Mediated Communication: Linguistic, Socialand Cross-Cultural Perspectives, S. J. Yates, Ed. Amsterdam, TheNetherlands: Benjamins, 1996, pp. 13–28.

[18] J. Nadler, T. Kurtzberg, M. Morris, and L. Thompson, “Getting toknow you: The effects of relationship-building and expectations one-mail negotiations,” presented at the IACM Conf., San Sebastian,Spain, 1999.

[19] D. E. Murray, Conversation for Action: The Computer Terminal asMedium of Communication. Amstedram, The Netherlands: Benjamins,1991.

[20] E. T. Hall, The Silent Language. New York: Doubleday, 1959.

Authorized licensed use limited to: Eindhoven University of Technology. Downloaded on October 30, 2009 at 09:46 from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply.

136 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON PROFESSIONAL COMMUNICATION, VOL. 44, NO. 2, JUNE 2001

[21] , “Three domains of culture and the triune brain,” in The CulturalContext in Business Communication, S. Niemeier, C. P. Campbell,and R. Dirven, Eds. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Benjamins,1998, pp. 11–30.

[22] G. Hofstede, Culture and Organization: The Software of the Mind. NewYork: McGraw-Hill, 1991.

[23] J. M. Ulijn and R. Kumar, “Technical communication in a multiculturalworld: How to make it an asset in managing international businesses,lessons from Europe and Asia for the 21st century,” in ManagingGlobal Communication in Science and Technology, P. J. Hager and H.J. Scheiber, Eds. New York: Wiley, 2000.

[24] R. Ma, “Computer-mediated conversations as a new dimension ofintercultural communication between East Asian and North Americancollege students,” in Computer-Mediated Communication: Linguistic,Social and Cross-cultural Perspectives, S. J. Yates, Ed. Amsterdam,The Netherlands: Benjamins, 1996, pp. 173–186.

[25] J. Ulijn and K. St. Amant, “Mutual intercultural perception: Howdoes it affect technical communication, some data from China, TheNetherlands, Germany, France and Italy?,” Tech. Commun., vol.47, no. 2, pp. 220–237, 2000.

[26] P. Van der Wijst and J. M. Ulijn, “Politeness in French/DutchNegotiations: The linguistic realization of politeness strategies,” inThe Discourse of International Negotiations, K. Ehlich and J. Wagner,Eds. Berlin, Germany: Mouton de Gruyter, 1995, pp. 313–348.

[27] S. L. Condon and Cl.-G. Cech, “Functional comparisons offace-to-face and computer-mediated decision making interactions,”in Computer-Mediated Communication: Linguistic, Social andCross-Cultural Perspectives, S. J. Yates, Ed. Amsterdam, TheNetherlands: Benjamins, 1996, pp. 65–80.

[28] C. C. Werry, “Linguistic and interactional features of internet relaychat,” in Computer-Mediated Communication: Linguistic, Social andCross-Cultural Perspectives, S. J. Yates, Ed. Amsterdam, TheNetherlands: Benjamins, 1996, pp. 47–64.

[29] S. J. Yates, “Oral and written linguistic aspects of computerconferencing,” in Computer-Mediated Communication: Linguistic, Socialand Cross-Cultural Perspectives, S. J. Yates, Ed. Amsterdam, TheNetherlands: Benjamins, 1996, pp. 29–46.

[30] J. D. Gibbons, Nonparametric Statistical Inference. New York:Marcel Dekker, 1985.

[31] J. M. Ulijn and X. L. Li, “Is interrupting impolite? Some temporalaspects of turn switches in Chinese–Western and other interculturalbusiness encounters,” TEXT, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 589–627, 1995.

Jan M. Ulijn holds an endowed Jean Monnet chair in Euromanagement at Eindhoven

University of Technology (The Netherlands) in the Department of Organization Science

and is a member of the Eindhoven Center of Innovation Studies. He regularly fulfills

part-time (visiting) professorships in other European countries, recently in Belgium

(Ghent), Germany (Darmstadt), and Denmark (Aarhus). His research and past

professional experience in the areas of innovation management, psycholinguistics,

technical communication, and culture has brought him to the United States (Stanford

and Fulbright) and China (Shanghai). His current research interests include

innovation culture as a mix of professional, corporate, and national cultures, with

implications for communication practice. He is a fellow of STC and earned the 1998

Association for Business Communication’s outstanding researcher award.

Authorized licensed use limited to: Eindhoven University of Technology. Downloaded on October 30, 2009 at 09:46 from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply.

ULIJN et al.: NON-FACE-TO-FACE INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS NEGOTIATION 137

Andreas Lincke started his studies of industrial engineering at the faculty of

Economics at the University of Technology, Darmstadt, Germany, in 1994. After

having gained intercultural experience while working at a large industrial company in

Ireland, in 1997, he earned a scholarship which enabled him to study at Eindhoven

University of Technology, The Netherlands, in 1998. There he did research in the

field of e-based international business negotiations together with Yunus Karakaya

under the supervision of Professor Ulijn. He was involved in a similar project for

his final thesis at Tilburg University, The Netherlands. He graduated in November

2000, and he is now working on his Ph.D. dissertation in the field of intercultural

negotiations in e-commerce.

Yunus Karakaya is currently a student of industrial engineering with electronics

engineering as his technical interest. In addition to his education, he has been

involved in several business consulting projects. Being a son of a Turkish worker in

Germany, he has much personal experience with intercultural communication. Mr.

Karakaya is studying at Darmstadt University of Technology, Darmstadt, Germany

and will graduate at the end of 2001.

Authorized licensed use limited to: Eindhoven University of Technology. Downloaded on October 30, 2009 at 09:46 from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply.

Related Documents