Nikolai Vavilov in the years of Stalin’s ‘Revolution from Above’ (1929–1932) Eduard I. Kolchinsky Abstract. This paper examines new evidence from Russian archives to argue that Soviet geneticist and plant breeder, Nikolai I. Vavilov’s fate was sealed during the ‘Cultural Revolution’ (‘Revolution from Above’) (1929–1932). This was several years before Trofim D. Lysenko, the Soviet agronomist and widely portrayed archenemy and destroyer of Vavilov, became a major force in Soviet science. During the ‘Cultural Revolution’ the Soviet leadership wanted to subordinate science and research to the task of socialist reconstruction. Vavilov, who was head of the Institute of Plant Breeding (VIR) and the All-Union Academy of Agricultural Sciences (VASKhNIL), came under attack from the younger generation of researchers who were keen to transform biology into a proletarian science. The new evidence shows that it was during this period that Vavilov lost his independence to determine research strategies and manage personnel within his own institute. These changes meant that Lysenko, who had won Stalin’s support, was able to gain influence and eventually exert authority over Vavilov. Based on the new evidence, Vavilov’s arrest in 1940 after he criticized Lysenko’s conception of Non-Mendelian genetics was just the final challenge to his authority. He had already experienced years of harassment that began before Lysenko gained a position of influence. Vavilov died in prison in 1943. Keywords. Politics, Soviet authorities, Stalinist science policies, the All-Union Academy of Agricultural Sciences (VASKhNIL), the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks), the Institute of Plant Breeding (VIR) 1. Introduction November 25, 2012 was the 125th anniversary of the birth of Russian scientist Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov (1887–1943). Biologists and historians of science know him as the author of numerous works on genetics, evolutionary theory, taxonomy, plant geography, ecology, phytopathology, immunology and the theory of selection and history of material culture. Meanwhile, social historians of science have been interested in the role he played in the establishment of the Soviet model of science organization, and as leader of an influential plant breeding and genetics school in the 1920s and 1930s. But, probably he is most widely remembered as the main opponent of Trofim Denisovich Lysenko (1898–1976), and as the man who sacrificed his life for his scientific convictions in the brutal environment of ∗ St. Petersburg Branch of the S.I. Vavilov Institute for the History of Science and Technol- ogy, The Russian Academy of Sciences, Universitetskaya nab. 5, 199034 St. Petersburg, Russia E-mail: [email protected] Centaurus 2014: Vol. 56: pp. 330–358; doi:10.1111/1600-0498.12059 © 2014 John Wiley & Sons Pte Ltd

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

Nikolai Vavilov in the years of Stalin’s ‘Revolutionfrom Above’ (1929–1932)

Eduard I. Kolchinsky

Abstract. This paper examines new evidence from Russian archives to argue that Soviet geneticist andplant breeder, Nikolai I. Vavilov’s fate was sealed during the ‘Cultural Revolution’ (‘Revolution fromAbove’) (1929–1932). This was several years before Trofim D. Lysenko, the Soviet agronomist andwidely portrayed archenemy and destroyer of Vavilov, became a major force in Soviet science. Duringthe ‘Cultural Revolution’ the Soviet leadership wanted to subordinate science and research to the task ofsocialist reconstruction. Vavilov, who was head of the Institute of Plant Breeding (VIR) and the All-UnionAcademy of Agricultural Sciences (VASKhNIL), came under attack from the younger generation ofresearchers who were keen to transform biology into a proletarian science. The new evidence showsthat it was during this period that Vavilov lost his independence to determine research strategies andmanage personnel within his own institute. These changes meant that Lysenko, who had won Stalin’ssupport, was able to gain influence and eventually exert authority over Vavilov. Based on the new evidence,Vavilov’s arrest in 1940 after he criticized Lysenko’s conception of Non-Mendelian genetics was just thefinal challenge to his authority. He had already experienced years of harassment that began before Lysenkogained a position of influence. Vavilov died in prison in 1943.

Keywords. Politics, Soviet authorities, Stalinist science policies, the All-Union Academy of AgriculturalSciences (VASKhNIL), the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks), the Institute of Plant Breeding(VIR)

1. Introduction

November 25, 2012 was the 125th anniversary of the birth of Russian scientist NikolaiIvanovich Vavilov (1887–1943). Biologists and historians of science know him as theauthor of numerous works on genetics, evolutionary theory, taxonomy, plant geography,ecology, phytopathology, immunology and the theory of selection and history of materialculture. Meanwhile, social historians of science have been interested in the role he played inthe establishment of the Soviet model of science organization, and as leader of an influentialplant breeding and genetics school in the 1920s and 1930s. But, probably he is most widelyremembered as the main opponent of Trofim Denisovich Lysenko (1898–1976), and asthe man who sacrificed his life for his scientific convictions in the brutal environment of

∗St. Petersburg Branch of the S.I. Vavilov Institute for the History of Science and Technol-ogy, The Russian Academy of Sciences, Universitetskaya nab. 5, 199034 St. Petersburg, RussiaE-mail: [email protected]

Centaurus 2014: Vol. 56: pp. 330–358; doi:10.1111/1600-0498.12059© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Pte Ltd

Vavilov in the years of Stalin’s ‘revolution from above’ 331

the Stalinist regime. These factors determine an unyielding interest in Vavilov, which istestified by an ever-expanding literature devoted to his research and career.1

A great number of these studies are devoted to the notorious confrontation betweenVavilov and Lysenko.2 From the late 1940s most foreign authors considered this episode inthe history of Soviet biology within a general context of the party-state policy. They basedtheir conclusions exclusively on published sources and a few testimonies left by Sovietgeneticists. Quite naturally, they sympathized with the opponents of Lysenko, who enjoyedthe support of the Soviet authorities (Cook, 1949; Dobzhansky, 1949; Zirkle, 1949). AfterLysenko’s downfall in 1964, Zhores Medvedev (1969) and Semen Reznik (1983) explainedVavilov’s tragedy and Lysenko’s success as a consequence of the extreme centralization ofSoviet biology and its isolation from world science in the Stalinist period. These authorsdid not use archival materials, and tended to consider events from the perspective of theparticipants. In their analysis of the confrontation between Vavilov and Lysenko, Medvedevand Reznik established a trend to portray the events in black-and-white and to passjudgments on the protagonists. They depicted the academic community of Soviet biologistsas victim of Lysenkoists. Vladimir Dudintsev’s bestseller White Garments (1988) was noless important for establishing the image of Lysenko’s opponents as disinterested truthseekers. Simon Shnoll’s book Heroes and Villains of Russian Science (Shnol’, 1997) aswell as a few recent works by foreign scholars such as V. Birstein (2001), Pringle (2008)and Nabhan (2008) conform to this tradition.3

Vavilov’s biographer, Mikhail Popovskii, gained access to the investigation file createdby the Soviet secret police after Vavilov’s arrest. In his documentary essay AcademicianVavilov’s 1000 days (1966), Popovskii named those researchers who had worked for theinstitutes chaired by Vavilov and who had precipitated, directly or indirectly, in his tragicdeath. David Joravsky (1970) in his book The Affair of T.D. Lysenko suggested that Vavilovhad played a part in Lysenko’s promotion. Later Popovskii made an even stronger claimwhen he blamed Vavilov for supporting the young agronomist (Lysenko) and in this wayensuring his rapid career advancement (Popovskii, 1991, pp. 92–95). A famous Sovietdissident and a Nobel Prize laureate, Andrei Sakharov, supported Popovskii’s accusationin his foreword to Popovskii’s book. Sakharov wrote: ‘… being subjectively an absolutelyhonest man, utterly devoted to science and the interests of his country, Vavilov dug a pitfor himself, into which he ultimately fell later in his life’ (Popovskii, 1991, p. 3). AnotherSoviet dissident, Valerii Soyfer, was even more categorical in his judgement when hegave one of the sections in his book the heading ‘Academician Vavilov’s decisive rolein promoting Soyfer’ (1994, pp. 108–115).

Loren Graham (1972, 1967) produced a complex analysis of the history of the SovietAcademy of Sciences from socio-cultural, political and ideological perspectives. Particu-lar attention was paid to the ‘Great Break’, the period of profound economic, social andpolitical transformation initiated by Stalin between 1927 and 1932 that included industri-alization, collectivization of agriculture, etc. Graham was the first to convincingly demon-strate that it was in these years that the academic community in the Soviet Union fell under

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Pte Ltd

332 E. I. Kolchinsky

tight administrative control. At the same time, in a foreword to the Russian edition ofhis book Science, Philosophy and Human Behavior in the Soviet Union, Graham empha-sized that in this period ‘there were no attempts to impose ideological interpretations ofsocial phenomena in natural sciences’, and the debates ‘did not affect leading Russian sci-entists’, even if the tendency to label a particular discipline as ‘bourgeois’ or ‘idealistic’markedly intensified in these years (Graham, 1991, pp. 17–18). In the early works producedby Mark Adams (1968) this period was defined as a very difficult one for Soviet genetics,yet Adams also believed the discipline was successfully developing in these years in theSoviet Union.

Feliks Perchenok, however, showed a less optimistic picture of the impact of the Stalinist‘Great Break’ on the Soviet academic community (1991). His research based on archivalmaterials was published originally in New York and later in Russia. True, the scale ofrepressions during the ‘Great Break’ was much more modest than during the Great Terror(1936–1938), but they still affected dozens of prominent scientists, who lost their jobs andwere often arrested, exiled or even executed. These purges in the institutions of highereducation and research that targeted ‘bourgeois specialists’ and replaced them with youngcommunists with insufficient academic training but impeccable social origins are knownas the ‘Cultural Revolution’. In recent years the use of archival material has increasedand there are now many studies that have explored the impact of the ‘Great Break’ uponbiographies of individual scholars and the fate of different disciplines (Fitzpatrick, 1984;Winer, 1988; David-Fox, 1997).

Particularly important is a recent book by Nils Roll-Hansen The Lysenko Effect.The Politics of Science (2005). It examines radical changes in the relations betweenscience and politics, scientists and the party-state administration and fundamental andapplied research in the Soviet Union in the period of the ‘Cultural Revolution’. Hisresearch specifically focuses on agricultural sciences. Roll-Hansen has overcome the rigiddichotomy between ‘heroes’ and ‘villains’; he does not blame Vavilov for promotingLysenko’s career in the early 1930s. Instead, he demonstrates how the adoption ofcentralized planning in agricultural sciences, which enjoyed Vavilov’s support, inevitablyled to accusations against Vavilov because he failed to demonstrate efficiency in his ownresearch (Roll-Hansen, 2005, pp. 92–94).

As more archival materials become available to scholars, we need to reconsider theconflict between Vavilov and Lysenko within a broader socio-political context and longertime-span. (Kolchinsky, 1991; 1999; Krementsov, 1997). Recent academic debates thathave taken place outside of Russia have focused on the Cold War period. They haveanalysed socio-political and scientific factors that led to the proliferation of Lysenkoism inthe post-war decades not only in the countries of the Soviet Bloc but also in Italy, Franceand Japan (Krementsov, 1996, 2000; Hossfeld and Olson, 2002; Schneider, 2003; Fujioka,2010; Wolfe, 2010; DeJong-Lambert, 2012). These factors were considered in depth ata few recent symposia devoted to Lysenkoism as a phenomenon of world science (NewYork 2009, Wien 2012, Tokyo, 2012). Some of the materials presented at these events

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Pte Ltd

Vavilov in the years of Stalin’s ‘revolution from above’ 333

have been published as special issues of the Journal for the History of Biology (Cassata,2012; deJong-Lambert and Krementsov, 2012; Gordin, 2012; Selya, 2012) and Studies inthe History of Biology (Argueta and Argueta, 2011; Köhler, 2011; Fujioka, 2013).

In the Russian Federation, however, the situation is quite different. Lysenko has becomequite a popular figure, even in some academic circles, and many people campaign forrestoring his reputation and the credibility of his research.4 The confrontation betweenVavilov and Lysenko is increasingly perceived as a mere disagreement between tworival scientific schools that competed for research funding. Too frequently, Vavilov isaccused of wasting money on useless expeditions and voyages abroad, interpreted asluxury tourist trips.5 There is also a tendency for his critics to emphasize his lack ofpatriotism. Sometimes these accusations go as far as suggesting that geneticists were luckyto become victims of Stalinist repressions, as their victimhood earned them undeservedfame. Lysenko, as the argument goes, has been misrepresented and his contribution to plantselection and animal breeding ignored by those who do not tolerate his patriotic sentimentsand his commitment to the struggle against eugenics. Sometimes Lysenko’s championsgo as far as claiming that he opposed Khruchshev’s risky experiments with agriculture.6

As a rule, these authors cite no new archival evidence. Instead, they base their claims onpublications produced in the Stalinist epoch or a few works written by historians of science.In order to refute these claims we need new studies based on new archival testimonies.

In this paper I will consider new documents that I discovered in the Archive of theRussian Academy of Sciences in Moscow (hereafter – ARAN), in its St. Petersburg Branch(SPF ARAN) and in the St. Petersburg Archive of the Communist Party (TsGAIPD).7

Many of these documents were only declassified in the last few years. These materialsdemonstrate the existence of important centres of opposition to Vavilov even beforeLysenko entered the scene. These centres were located in the All-Union Institute forApplied Botany and New Cultures (VIPBINK), the All-Union Institute of Plant Breeding(VIR),8 the Communist Academy and its Leningrad Division.9

Firstly, I will consider the relations between Vavilov and the Soviet authorities in the1920s when the party-state administration tried to use scientists as a means to overcomethe isolation of the Soviet Union in international politics, to restore the country’s industrialbase ruined in the Civil War and to solve the problem of food security. Before 1932Vavilov managed to persuade the party-state authorities that his research program was veryimportant. He received considerable financial and human resources. Later in this paper,I will try to demonstrate how the Stalinist ‘Cultural Revolution’ in science spurred anassault against Vavilov, who was accused of failing to mobilize science for the socialistreconstruction of agriculture. This conflict disorganized research and led to personnelchanges in the Institute of Plant Breeding. Thanks to a new turn in the party policies in1932, Vavilov was able to retain his position as an acknowledged leader of agriculturalsciences in the USSR. Yet his freedom to choose his personnel and define the researchagenda was substantially curtailed. For example, the People’s Commissar of Agricultureasked Vavilov to support Lysenko even though their views on genetics and agronomics

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Pte Ltd

334 E. I. Kolchinsky

were very different. I will discuss the implications that these early attacks had on Vavilovpersonally, for the system of research institutes that Vavilov created and the subsequentconflict with Lysenko.

2. ‘The Union of Science and Labour in the Renovated Land’

Vavilov, like many other scientists in pre-revolutionary Russia, believed that state fundedscience could solve all the global problems faced by humankind. He devoted his life tothe ‘grain problem’; that is how to mobilize world plant resources to overcome recurrentfamines. Finding a solution to this problem was a pressing issue in Soviet Russia as thecountry often experienced famines caused by environmental factors and state agriculturalpolicies (Tauger, 2011). Particularly tragic were the famines of 1921 and 1932, in whichmillions died (Dronin and Bellinger, 2005; Tauger, 2008).

Vavilov tried to find scientific means to solve the food security problem. He developedhis theory of plant immunity towards infectious diseases (Vavilov 1935, 1919), formulatedthe law of homologous series in hereditary variation (Vavilov, 1922), identified the maincentres of origin of cultivated plants (Vavilov, 1926, 1931a) and laid the foundations forthe theory of the intraspecific structure of cultivated plants (1931b, 1940). His research wasmeant to facilitate the search for original plant forms, which could be used in the selectionprocess. That was the aim of his numerous expeditions to five continents (1922–1934).These expeditions earned him the reputation of the best ‘plant hunter’ in the world(Vavilov, 1962). By 1940 the collection of seeds, which was amassed under his supervision,consisted of 250,000 specimens. In a series of works on plant resources of various countries(1935–1937), Vavilov justified the principles of selection, seed and plant breeding from theperspectives of botany, geography, genetics and ecology.

In the 1920s the world was passing through an acute economic crisis, which meantthis type of research was only possible in most countries if there was large-scale statesupport. Such support was generally only forthcoming if projects promised immediatepractical applications. This was particularly true in the case of the USSR. But the Bolshevikleaders, in particular the chair of the Soviet government Aleksei Rykov and his executiveofficer Nikolai Gorbunov both supported Vavilov and his research. Vavilov also had a goodworking relationship with a great favourite of the Communist Party leadership, who wasalso the main party’s theoretician, Nikolai Bukharin. The Soviet leadership consideredVavilov to be a prominent scientist who had accepted the socialist ideas and was able tocombine theory with practice. In a certain sense, we can say that Vavilov belonged tothe ruling elite: he was a member of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR andthe All-Russian Central Executive Committee of the Russian Soviet Federative SocialistRepublic. Although not a Communist Party member, Vavilov nevertheless took part in theparty congresses and conferences.

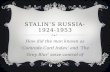

With the support of the Soviet government Vavilov organized the First All-UnionCongress on Genetics and Plant and Animal Breeding which took place in 1929 (Figure 1).

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Pte Ltd

Vavilov in the years of Stalin’s ‘revolution from above’ 335

Fig. 1. The members of the Presidium of the First All-Union Congress on Genetics and Plant and AnimalBreeding, from left to right: N.I. Vavilov, N.A. Tataev, N.P. Gorbunov (1929).

It became a large-scale ideological campaign. It was meant to demonstrate that geneticistsand plant and animal breeders were able to overcome the main agricultural problems.On the day of the congress’ opening Vavilov, who liked publicizing the achievementsof Soviet geneticists, wrote a piece for the newspaper of the Leningrad Regional PartyCommittee in which he named a few Soviet academic institutions that were ‘well aheadof scientific research centres anywhere in the world’ (Leningradskaia Pravda, 10 January1929, p. 5). In the same issue Nikolai Gorbunov wrote about an important contributionmade by Vavilov himself. Both articles were published under a headline ‘Soviet sciencecomes to the aid of the fields: Higher yields’. Vavilov took the opportunity of his speechat the opening ceremony to emphasize the unprecedented pace of industrialization ofagricultural science in the USSR. Meanwhile, the first secretary of the Leningrad RegionalParty Committee, Sergei Kirov, used his speech on behalf of the Soviet government to callfor ‘the union of science and labour in renovated Lenin’s land’ and for the ‘enriching ofagricultural practice with science’ (Leningradskaia Pravda, 11 January 1929, p. 1). Otherspeeches stressed the fact that the congress had attracted the attention of scientists fromaround the world. Indeed, it was attended by German geneticists Erwin Baur and RichardGoldschmidt, as well as by a former Russian geneticist Harry Federley who had emigratedto Finland after the revolution. These eminent scientists well understood what was expectedof them. They eagerly acknowledged that the Soviet geneticists and plant breeders wereahead of their foreign colleagues. Erwin Baur, who edited the first academic journal ongenetics, Zeitschrift für induktive Abstammung und Vererbungslehre, even claimed that

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Pte Ltd

336 E. I. Kolchinsky

foreign geneticists envied their Soviet colleagues for their achievements in selection andapplied genetics.10 Vavilov and a few other participants portrayed genetics as a science thatwas already able to work miracles in producing new breeds of animals and plants (Vavilov,1929, p. 6). Comparing geneticists to the Creator, Vavilov emphasized that a geneticistmust ‘not only know his construction materials but take part in the construction. To be anengineer in his own domain – this is the objective of a geneticist’ (Leningradskaya Pravda,16 January 1929, p. 3).

Soviet newspapers provided extensive coverage of the congress. They cited speechesmade by leading Soviet geneticists and plant breeders who spoke about new varietiesof grains produced in their laboratories, which promised to extend the borders of wheatproduction areas to the far north (Andrei Sapegin, Georgii Meister), the prospects ofinterspecific and intergeneric hybridization (Viktor Pisarev, Georgii Karpechenko), anincrease in grain yields of 25-40 per cent thanks to the introduction of fast-ripening varieties(Viktor Talanov) and even about a transformation of winter crops into spring ones (NikolaiMaksimov). On every congress day the Leningradskaia Pravda – the newspaper of theLeningrad Communist Party Organization – published a detailed account of the congressevents under catchy headlines: ‘A broad stream of knowledge will flow to the fields of ourcountry. Two thousand scientists hasten to aid agriculture’ (11 January 1929, p. 3); ‘Victoryof Soviet science. New cereal crop has been created. From experimental fields – to peasantfields’ (12 January 1929, p. 5); ‘In a renovated land. High quality seeds for the peasantry.Soviet science will raise yields on our fields’ (13 January 1929, p. 2); ‘Soviet science goesto peasant fields. Success of animal husbandry. Kholmogor cow beats world records’ (15January 1929, p. 3); ‘Success of Soviet science. German scientists use our experience.Winter crops can be transformed into spring ones’ (16 January 1929, p. 3).11

The specialists who presented their papers at the congress were not quite so reck-less when they spoke about the potential practical applications of their research in theshort-term. For example Nikolai Maksimov, who reported on research concerned withmodifying the vegetation period of certain crops was careful to emphasize that, althoughin principle these crops could be transformed from their winter breeds into spring ones,at that time such a transformation was still possible only in the laboratory environment(Maksimov, 1929, p. 19).

Lysenko was present at the congress. He and Donat Dolgushin gave a joint paper onwinter crops and their vernalization.12 Contrary to the legend, neither Vavilov, nor theSoviet press paid any particular attention to this speech (Dolgushin and Lysenko, 1929)13.Yet Lysenko had a chance to learn how to exploit the trust of the Soviet leadership in thefast-moving area of agricultural modernization. Many congress participants consideredvernalization – a method that had been known for some time - as a promising means toaccelerate plant selection. Very soon Lysenko would appropriate it as his own uniqueachievement, which allegedly allowed agronomists to produce new high-yielding breedsof crops.

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Pte Ltd

Vavilov in the years of Stalin’s ‘revolution from above’ 337

At the time of the congress, however, it seemed that the Soviet party-state administrationconsidered Vavilov the undisputed leader of agricultural science and genetics. In the sameyear, he was entrusted with the task of establishing the All-Union Academy of AgriculturalSciences (VASKhNIL) and the Institute of Plant Breeding (VIR). Vavilov became thefirst VASKhNIL president and VIR director. He was also appointed as a member of theCollegium of the People’s Commissariat of Agriculture of the USSR established on 7December 1929, and was charged with the task of providing centralized planning andadministration for agricultural production across the whole country. In the next year hewas elected to the Leningrad City Council. From 1930 he was also appointed the headof the genetics laboratory at the Academy of Sciences, and in 1934 Vavilov oversaw itsreorganization into the Institute of Genetics.

Vavilov could independently define the institute’s research agenda in the early days,as well as manage its personnel and keep an eye on the day-to-day administration. Soonhowever it became clear that the 1929 congress which he had organized, was both thepinnacle and the final episode in the ‘union of science and labour’. The congress met atthe moment when the Soviet state paid ‘its utmost attention to the problems of plant andanimal breeding’ (an expression used by Vavilov in his opening speech) (LeningradskaiaPravda, 10 January 1929, p. 5). The implications of the ‘utmost attention’ were evident, asit was also the time of elections to the Academy of Sciences.14 On 13 January 1929, whilethe congress was still in progress, the Leningradskaia pravda published a letter ‘On behalfof the Presidium of the Academy of Sciences’. The letter contested the election results andcalled for casting a new ballot, so that the Communist Party candidates, who had failed inthe elections, would nevertheless become its members.15

It was also around this time that Vavilov faced the first challenges to his authority inthe institutions he administered. The State Institute of Experimental Agronomy’s (GIOA)which developed in 1930 into the V.I. Lenin All-Union Academy of Agriculture; partybureau had requested Vavilov to ‘include Marxist forces into a list of speakers at thecongress’ (TSGAIPD, f. 304, op. 1, d. 4, l. 1).16 Because this request had not beenappreciated, the bureau decided ‘to inform higher party organizations about the fact thatthe bureau was not consulted when party members were elected to the congress organizingcommittee’ (TSGAIPD, f. 304, op. 1, d. 4, l. 1).

3. Vavilov under Fire

By mid-1929, when a party cell was created at the All-Union Institute for Applied Botanyand New Cultures (VIPBINK) some of its members became visibly hostile to Vavilov. Atthe party meetings its members began to speak about reactionary tendencies and moraldecay among the institute’s personnel. They criticized recruitment strategies when peoplewere hired regardless of their social background and party affiliation, and emphasized theresistance of old specialists to socialist construction. The institute’s leadership was accusedof privileging theoretical research to the detriment of applied agronomy. (TSGAIPD, f. 304,

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Pte Ltd

338 E. I. Kolchinsky

op. 1, d. 1, l. 1–2). Usually, Vavilov’s opponents were more outspoken when he was onresearch trips abroad; when he returned to the institute they were perceptibly less active.

It was not only the contradictions between the party members and the rest of theinstitute’s employees that provoked the attacks on Vavilov. Plant breeders, agronomistsand seed producers also envied the success of geneticists. From the mid-1920s, thesepeople began to voice an opinion that Vavilov’s institute paid excessive attention toamassing its collections of seeds and plants. Among the critics was the dendrologistDmitry Artsybashev, who had served on the Academic Committee of the Ministry ofAgriculture and State Domains before the revolution and who was supported by N.P.Gorbunov. In VIPBINK he chaired a section for plant naturalization. Artsybashev’s viewswere shared by the head of a Bureau for Plant Introduction, Aleksandr Kol’ and a plantbreeder Aleksandr Lorkh, who specialized in breeding potatoes. Soon Artsybashev andLorkh left the institute but Kol’ remained. Kol’ supported Mechano-Lamarckist viewsabout the inheritance of acquired characteristics as the principle cause of evolution. Heinsisted that the institute should have focused on the introduction of new plant breeds, theirtesting and regionalization, and accused Vavilov of his excessively academic approach,unnecessary fascination with expeditions and authoritarian methods of administration.Later on he began to claim that Vavilov was reluctant to promote young specialists andwas even engaged in sabotage (TSGAIPD, f. 304, op. 1, d. 3, l. 83–84). In 1929 Kol’ losthis position as head of the section but continued his campaign against Vavilov. Later onhe would become one of the principal supporters of Lysenko and Lysenkoism in VIR.In 1929 VIPBINK recruited a few people who studied at the Leningrad PostgraduateInstitute of the VASKhNIL. They supported Kol’ in his struggle against Vavilov and theinstitute’s leadership. Between 1930-1932 the conflict within the institute acquired politicalconnotations. This conflict contained the seeds of the future tragedy.

Advancements in genetics and H.J. Muller’s discovery of artificial mutagenesis (1927),in particular, undermined the idea of inheritance of acquired traits (Gaissinovich, 1980).At the second All-Union Conference of Marxist-Leninist Research Institutions, which tookplace on 8–13 April 1929, its participants condemned Mechano-Lamarkism as a theory thatwas incompatible with Marxism. Its advocates were removed from positions of authorityin the Communist Academy. Young Marxist geneticists (I.I. Agol, S.G. Levit and M.L.Levin) took over their positions in the Timiriazev Biological Institute within the Society ofMarxist Biologists. However, Mechano-Lamarckists were unwilling to accept their defeatand some of them were irritated by Vavilov’s popularity and the support he still enjoyed.

Still, these sentiments alone cannot explain the massive assault on Vavilov that tookplace over the next few years. This was determined by a unique combination of political,ideological and socio-economic factors. The spring of 1929 marked the beginning of theStalinist ‘Cultural Revolution’, an attack on the intelligentsia, and the ‘dialectization’ ofbiology (Fitzpatrick, 1984; David-Fox, 1997; Kolchinsky, 1999, 2012). Vavilov’s reservetowards the drive for ‘proletarian biology’ left ample room for accusations of ideological

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Pte Ltd

Vavilov in the years of Stalin’s ‘revolution from above’ 339

mistakes, sympathy towards ‘bourgeois specialists’ and the prevention of young scientistsfrom being promoted.

Even greater danger came from accelerated collectivization, which caused a sharpdecline in agricultural production and famine. N.I. Bukharin, A.I. Rykov and a few otherleaders of the ‘right-wing deviation’ in the Communist Party were made responsible forthis failure. Many members of the intelligentsia faced false criminal charges. EconomistsNikolai Kondrat’ev, Lev Litoshenko and Alekhsandr Chaianov, who were arrested in 1930in the ‘Case of the Labour Peasant Party’, were Vavilov’s long-time friends and colleagues.He petitioned for their release – an act that obviously did not please those who initiatedtheir persecution. When A.I. Rykov and N.P. Gorbunov were removed from their positions,Vavilov lost the support of those people in the government with whom he had earlierdeveloped large-scale projects designed to promote agricultural research in the USSR.When the People’s Commissar of Agriculture Andrei Berzin was arrested, Vavilov lostanother communication channel with the Soviet leadership. Just one of these factors wouldhave been sufficient to terminate a career in science administration. Vavilov, however, stillhad many advantages. He had cultivated a broad network of international contacts, enjoyeda reputation as the best ‘plant hunter’ and still had many supporters. He was extremelywell respected by the academic community, and he was viewed quite favourably by theLeningrad Regional Party organization. Nevertheless, just a few months after the All-UnionConference of 1929, elements within the Communist party organizations at the VIR andthe Leningrad Postgraduate Institute at the VASKhNIL began to attack Vavilov.

The party organization at the Leningrad Postgraduate Institute (Leningradskii InstitutAspirantury) at the VASKhNIL was lead by a former seaman Grigorii Bykov. Until veryrecently historians of science knew him only through the memoirs written by EvgeniiaSinskaia (1991, p. 148). She characterized Bykov as a man ‘with a loud voice, whowas unusually keen on giving awesome speeches at rallies’. Verbatim minutes of theparty meetings at the institute enable us to understand better this person who becamethe formal leader of the opposition to Vavilov. Bykov took an active part in all partyand academic meetings when the VIR was discussed. He had little understanding of theacademic problems yet he had a keen sense of the moment and knew when to criticizeVavilov and when to admonish or even to defend him. It is unlikely that he harboured anyplans to remove Vavilov from his office. Bykov sincerely cared about the institute; buthe was equally convinced that his own ideas were right. Only when Vavilov initiated theclosure of the Leningrad Postgraduate Institute did Bykov begin to declare that ‘Vavilov’sreputation has been exaggerated’ (TSGAIPD, f. 304, op. 1, d. 19, l. 115).

The strategy adopted by Vavilov’s opponents was determined by the resolutions of theNovember plenary session of the Party Central Committee (1929). The session decidedon a major reorganization of higher schools and academic institutions; their personnelhad to be ‘strengthened’ by the recruitment of party members and people with a workingclass background, while the Communist Party assumed control over academic researchand the training of young scientists. In December 1929, A.K. Timiriazev – a man who

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Pte Ltd

340 E. I. Kolchinsky

was one of the key figures in the ‘dialectization’ of the natural sciences – wrote a letterto the presidium of the Communist Academy. In this document, he criticized the facultyand curriculum of the postgraduate program: the program was excessively focused onspecialized subjects; it could not provide students with a broad theoretical framework(ARAN, f. 350, op. 1, d. 285, l. 1–3). The letter evidently matched Stalin’s speech ‘Onthe questions of agricultural policy’, which was delivered on 27 December 1929 at aconference of Marxist agriculturalists at the Communist Academy (Stalin, 1955a). In thisspeech, Stalin indicated that the ‘theoretical front’ was lagging far behind ‘the advancesmade in the socialist construction’. The speech unleashed a campaign aimed at discreditingestablished scientists.

The new party line on establishing control over the training of research personneldirectly affected the VIR. In 1929 the institute recruited 19 postgraduate students, amongwhom 13 (or 72.2 per cent) were communists or Komsomol members; in terms of theirsocial background these postgraduate students were predominantly ‘workers – 3 persons(15.78 per cent) and peasants – 10 persons (52.63 per cent)’ (TsGAIPD, f. 304, op. 1, d.4, l. 4). Most of them had no previous experience of academic research. But they hadtaken part in the civil war; they also had held positions of authority in the party and thestate administration. They sincerely believed in their right to control ‘bourgeois specialists’and framed existing disagreements over research policies and objectives as a political andideological controversy. Those postgraduate students, who were reluctant to speak againstVavilov, were accused of being apolitical, egotistic and unscrupulous (TsGAIPD, f. 304,op. 1, d. 9, l. 13). Everyday life in the institute became a series of incessant meetings,resolutions and denunciations. New party functionaries were appointed and replaced on theallegations that they ‘betrayed the trust’ and ‘sheepishly followed the directorate’. Within18 months the party bureau and its secretaries had been re-elected five or six times.

Among the most ambitious postgraduate students were Anatoly Al’benskii and GrigoriiShlykov, who would be known later as one of the most active supporters of Lysenko inthe VIR. Before his admission to the postgraduate program, Shlykov had received onlythe most basic education in a village school (TsGAIPD, f. 304, op. 1, d. 65, l. 2). Yet asa postgraduate student, he soon started criticizing Vavilov. He certainly knew a lot aboutpolitics and was very apt at following the party line.

However, contrary to prevailing assumptions, in those years it was not Shlykov oreven Bykov but Al’benskii, who was the real mastermind behind the attacks on Vavilov.A former student of a theological seminary in Yaroslavl’, he made a career of being aSoviet activist. In 1930 he graduated from a university in Perm’, and was enrolled asa postgraduate student in the VIR. Al’benskii specialized in dendrology but in all hisspeeches he made a show of his familiarity with philosophy and its great names. Hemasked his careerism with speculations about a detrimental philosophical, methodological,political, ideological, social and economic impact exercised by all scientific theories, apartfrom those that he supported himself. It was Al’benskii who persecuted pre-revolutionaryspecialists in the VIR, who insisted on their replacement by communists. When in May

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Pte Ltd

Vavilov in the years of Stalin’s ‘revolution from above’ 341

1931 Al’benskii became the secretary of the VIR party organization, he changed hisstance for a while: instead of criticizing the administration of the institute, he became itssupporter. He even claimed that Vavilov was reconsidering his concepts, coming closer tothe ‘Darwinian’ and dialectical Marxist understanding of evolution. He would speak abouthis former attacks against Vavilov as ‘petty sins’ of his youth (Sinskaia, 1991, p. 149).Later he would become a prominent figure in dendrology and afforestation.

4. ‘Here, in the VASKhNIL, We are Fighting for the Marxist Methodology’

The words quoted in the title of this section were used by the participants of a meeting,which took place on 9 February 1931 at the biological unit of the Science Sectionof the Leningrad Division of the Communist Academy (LOKA). They referred to thesituation in the VASKhNIL (SPF ARAN, f. 240, op. 1, d. 5, l. 56). By that timethe leading Soviet newspapers - the Pravda, Komsomol’skaia Pravda, EkonomicheskaiaZhizn’, Leningradskaia Pravda - had already published critical articles either written byVIR employees or produced at their instigations. Vavilov’s opponents were comfortableeven to denounce the OGPU (Joint State Political Administration, or the Soviet secretpolice) and the Peasants’ and Workers’ Inspectorate. In 1930–1931, various ‘brigades’carried out investigations of the VIR and the VASKhNIL on numerous occasions; theinstitute’s administration was publicly criticized at meetings and many leading researcherswere accused of misconduct.

On 4 October 1930, the Komsomol’skaya Pravda published an article written by thesecretary of the VIR Communist Party organization, Geilikman. It propelled the conflict toa new level as the article forced the October District Party Committee and the LeningradRegional Party Committee to intervene. On 8 October 1930, the article was discussed at aplenum of the VASKhNIL party and Komsomol organizations; the plenum was closed tothe public. Opening the floor for debates, Geilikman pointed out that the VASKhNIL and itsinstitutes had neither research plans, nor research output that could be of any significancefor agricultural practice: ‘people do know what has to be done’; but no one could givedetailed recommendations as to ‘where to sow, what to sow and how to sow’; ‘communistsand Komsomol members fail to see that saboteurs are working in the institutes’. Manyspeakers laid responsibility on Vavilov, as the VASKhNIL president. He was accused ofsupporting and defending those ‘specialists of noble social origins’, almost all of who wereallegedly engaged in sabotage (SPF ARAN, f. 240, op. 1, d. 5, l. 36–39). Part of the blamewas attributed to various party institutions and other watchdog agencies. Thus, for example,a postgraduate student called Alexander Luss noted that a special commission of the partyCentral Committee had been investigating the situation and even promised to appoint a few‘Red professors’, yet these appointments had not been made, and ‘no practical measureshad yet been adopted’ (TsGAIPD, f. 304, op. 1, d. 5, l. 39). Summarizing the debates,the secretary of the VASKhNIL party bureau Degtiarev assured the audience that ‘ourmeeting can be considered as the first stage in the struggle for a truly Leninist academy’

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Pte Ltd

342 E. I. Kolchinsky

and promised to ‘consider specialists from a political standpoint’ (TsGAIPD, f. 304, op. 1,d. 5, l. 40).

Another similar article in the Leningradskaia Pravda (7 December 1930) soon followedthe publication in the Komsomol’skaia Pravda. Together, they opened the way for a wave ofinvestigations by the party authorities, the Leningrad Section of the Communist Academy,the Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspection. When in January 1931 Vavilov returned to theinstitute from a 6-month research trip in the southern parts of the USA, Mexico and CentralAmerica, he was shocked by the situation he encountered at his home institute:

From about 1920, I have not seen the institute in such a miserable state: half of its building hasno heating, lecture rooms have no heating, the library, which is the brain of the Academy, has noheating. It is impossible to train future scientists when the temperature is about 5 or 6 degrees.Postgraduate students are deprived of a normal working environment. (TsGAIPD, f. 304, op. 1, d.19, l. 111)

He was even more shocked by the ‘moral dislocation’ created by a few party members.Nevertheless, Vavilov did not hesitate to step into the battle. At a meeting on 9 February1931, G.I. Bykov was the first one to voice criticisms against Vavilov: he demanded theimposition of proletarian dictatorship in the institute. In his reply, Vavilov explained theproblems faced by the institute’s administration and accused his opponents of ignorance(TsGAIPD, f. 304, op. 1, d. 3, l. 44–56). Vavilov also threatened to resign if Kol’ remainedin the institute. His opponents responded by saying that the party would not succumb toblackmail: Kol’ would not be dismissed from his position in the institute. Degtyarev wasquite explicit in his speech:

Vavilov is wrong. [… ] Young people are right in their attacks. [… ] The revolution is a wind thatcasts away everyone who is resisting us. (TsGAIPD, f. 304, op. 1, d. 3, l. 56)

As we can see from the documents that I asked to be declassified, those members ofthe institute’s personnel who spoke against Vavilov followed the directives that PavelArtem’ev, the secretary of the institute’s party organization, had given to the communistson the eve of the meeting. Artem’ev emphasized:

Submission to Vavilov’s authority has led to sad results. The results of our work have not improvedthe state of agriculture in the country. It is necessary to pose a question to Vavilov, whether he iswith us, or not… It is Vavilov against whom we have to fight. If the vice-director and the academicsecretary are not with us, we have no one to rely upon. All the time we sense two lines – Vavilov’sline and ours. (TsGAIPD, f. 304, op. 1, d. 21, l. 34)

Calling for a change of VIR leadership, Atrem’ev suggested the kinds of human resourcethat could be used to replace old personnel.

The Postgraduate Institute should provide us with suitable folk. At this meeting, we should pose thequestion bluntly. We should start the battle. The sessions that have been planned by Vavilov shouldnot be permitted. (TsGAIPD, f. 304, op. 1, d. 21, l. 35)

It was a well-orchestrated campaign against Vavilov, which was coordinated and inspiredfrom above. The brigade dispatched by the Party Central Committee to investigate the

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Pte Ltd

Vavilov in the years of Stalin’s ‘revolution from above’ 343

VASKhNIL presented its report at the party conference at the VASKhNIL presidium inearly 1931. The resolution adopted by the conference reproduced the very same accusationsagainst the VASKhNIL leadership that had been voiced at the meetings in the VIR.The resolution also contained a plea to the Party Central Committee and the People’sCommissariat of Agriculture to replace the members of the VASKhNIL presidium andthe heads of its research institutes with postgraduate students who were party members(TsGAIPD, f. 304, op. 1, d. 15, l. 75–76).

Also in 1931, several Marxist organizations were created within the Leningrad Sectionof the Communist Academy: the Society of Marxist biologists (OBM), a section fornatural sciences at the Society of Militant Dialectical Materialists (OVMD), the biologicalsection of the Institute of Natural Sciences. Isaak Prezent, who later became Lysenko’sright-hand man and the main ideologist of Lysenkoism,17 chaired all these organizations.The overarching aim of the institutions was to develop a ‘proletarian’ or ‘dialectical’biology. In February 1931, at the first meeting of the biological section of the Instituteof Natural Sciences, Prezent pontificated:

The October revolution is just about to begin in relation to theoretical framework. We need to takeall the work on our shoulders. Our main objective is self-criticism and shaking-up. We need to do allbackground work by collecting materials so that we can familiarise ourselves with all the reactionaryapproaches. We need to criticise everyone. Large-scale preliminary research, mass data collectionshould be done in all institutions. We need to propose [people for nomination to] a brigade. Itwould determine the order, in which we would attack all the approaches and [particular] figures.(SPF ARAN, f. 240, op. 1, d. 5, l. 58)

Prezent explicitly suggested that the young opponents of Vavilov should assume the roleof the Regional Party Committee’s henchmen in the field of science:

We must follow the line that is approved by the Regional Committee, whom and how we shouldattack and whom we should support. The main criterion is a scientist’s political outlook. (SPFARAN, f. 240, op. 1, d. 5, l. 58)

Indeed, all the decisions taken by the OBM and the biological section of the Institute ofNatural Sciences at the LOKA referred to the Regional Party Committee and stressed theneed to secure its approval (Figure 2).

Prezent had already selected the VASKhNIL and Vavilov as primary targets for investi-gation. In fact, the February meeting was devoted to this particular issue. But, not all thepostgraduate students were keen to criticize their teachers. One postgraduate student calledS.N. Reznik was, however, happy to speak about his own poor professional training:

Dialectical materialism is taught perfectly well, but we receive very poor methodological trainingin the areas of our specialisation [… ] to be able to link Marxist methodology with experimentalresearch. (SPF ARAN, f. 240, op. 1, d. 5, l. 56)

He also claimed that there were only 73 communists and 42 Komsomol members among200 postgraduate students at the VASKhNIL, and he pointed out that even they had ‘littleinterest in the work done by the LOKA brigades’, in unmasking ‘reactionary theories’

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Pte Ltd

344 E. I. Kolchinsky

Fig. 2. Isai I. Prezent (in first line, right) and his colleagues (1945) (personal archive of author).

promoted by cytogeneticist Grigorii Levitskii, ichthyologist Lev Berg and entomologistAleksandra Liubishcheva. Elena Pruzhanskaia, a postgraduate student and the secretaryof the Biological Association of the USSR Academy of Sciences voiced her support forthis view. She pointed out that the only communists among the postgraduate studentswere those who were still taking preparatory courses, and their education was certainlyinsufficient to criticize specialists.

Prezent’s wife, Basia Potashnikova, agreed with Prezent in general, yet she believed thatthe Leningrad party leadership should approve all actions against Vavilov:

We should investigate the VASKhNIL because it plays an important role in our socialist construc-tion. Postgraduate students have been right in criticising some members of its staff. Vavilov’s viewscertainly obstruct our attempts to make the Institute of Plant Breeding more involved in the socialistconstruction. It is very difficult to fight against them, as they have a very tight bunch of specialists.They have many real specialists, without whom we still cannot dispense. The question about Vavilovshould be discussed with the Regional Party Committee. (SPF ARAN, f. 240, op. 1, d. 5, l. 57).

Potashnikova was a geneticist. She was appointed to chair the LOKA brigade sentto investigate the Genetics Laboratory of the Academy of Sciences. In those days thelaboratory came under Vavilov’s administration. Potashnikova worked at this laboratoryuntil 1932 (TsGAIPD, f. 2012, op. 2, d. 75, l. 31–31ob.) and Prezent was also a frequentvisitor. These circumstances apparently provided some factual basis for later rumours aboutPrezent ‘consulting’ Vavilov on philosophical issues of genetics. It is also known that

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Pte Ltd

Vavilov in the years of Stalin’s ‘revolution from above’ 345

Potashnikova, as the secretary of the organizing committee, helped Vavilov convoke theAll-Union congress on planning genetics research (25–29 June 1932).

Prezent’s position reflected the stance adopted by embryologist Boris Tokin, who chairedthe OBM in Moscow. On 14 March 1931, in a paper read at the OBM general meetingTokin imposed on Marxists-Leninists the duty of overcoming their contemplative atti-tude towards living nature: biologists were called upon to transform winter breeds intospring varieties, supply the USSR with home-produced cotton and rubber and preventdroughts. Tokin was particularly irritated by ‘non-interference into Vavilov’s methodolog-ical framework’ (Bondarenko et al., 1931, p. 12). He demanded an investigation of thewhole system of the institutions of agricultural science, yet he was quite careful to stipu-late: ‘it does not mean we should put forward a slogan of criticism of Vavilov’ (Bondarenkoet al., 1931, p. 12).

When one of the most respected members of the academic community, thebio-geo-chemist Vladimir Vernadsky had a chance to look through the published materialspresented at this meeting, he wrote:

It is impossible to read, so sick, so ignorant. For a psychiatrist. A picture of moraldegradation… Small-minded people lacking a basic understanding of what academic research isabout… .(Vernadsky, 2001, p. 258)

Yet it was these people who aspired to exercise methodological control ‘over the recentand future network of research institutions subordinated to the People’s Commissariat ofAgriculture (the VASKhNIL was the first one among them)’. They planned to ‘hear areport on research at the VASKhNIL institutes of animal breeding and plant breeding at theplenary session of the OBM’, and organize ‘a brigade to investigate and assess Vavilov’swork’. The brigade was meant to ‘prepare a paper on genetics, selection and the problemsof plant breeding for the plenary session’ (Bondarenko et al., 1931, p. 92–93).

5. ‘Former Saboteurs make a Fairly Good Contribution to the SocialistConstruction’

Endless conflicts and inspections not only demoralized the institute’s personnel, they alsodestabilized the party organization in the VIR. The Leningrad Regional Party Committeehad to intervene. On 9 July 1931, a meeting of the committee secretariat chaired byS.M. Kirov adopted a resolution ‘On the work of the Leningrad institutions of the LeninAcademy of Agricultural Sciences’(TsGAIPD, f. 24, op. 1, d. 323, l. 2). Boris Pozern, whowas the LOKA president and the Regional Party Committee secretary for ideology, wasthe editor. Given the circumstances, the document certainly showed Vavilov in a favourablelight, as it acknowledged:

a certain break-through in the direction of promoting practical applications to the problems of thesocialist reconstruction of agriculture (testing new varieties of seeds, increasing yields, problems ofanimal husbandry, fodder ingredients, technical cultures, etc.).

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Pte Ltd

346 E. I. Kolchinsky

At the same time, the document noted the lack of ‘Bolshevik perseverance in eradi-cating’ right-wing opportunism, ‘insufficient efforts in the struggle against saboteurs’,‘excessive presence of alien elements within the personnel’ and ‘weak links with socialistproduction’. But the overall recommendation was that Vavilov’s opponents should stoppersecuting those specialists who took part in the socialist construction. To some extent,the personality of Vavilov’s new deputy, Nikolai V. Kovalev, affected the content of theresolution. Kovalev was appointed to this position in May 1931. He was an experiencedscience manager, much respected by the Communist Party authorities.18 But, in the wordsof the secretary of the October District Party Committee Moisei Kolchinskii, who wasappointed to control the VIR, the best social background could not compensate for a lackof knowledge (TsGAIPD, f. 304, op. 1, d. 22, l. 14).

This drastic turn in personnel management policy followed in the wake of Stalin’s speech‘New environment and new goals’ delivered on 23 June 1931. Stalin called a halt to theharassment of the old intelligentsia (Stalin, 1955b). A few days later, while B.N. Pozernwas still editing the resolution of the Leningrad Regional Party Committee, N.I. Vavilovtook part in the second International Congress for the History of Science in London.His inclusion in the Soviet delegation at the congress (proposed by N.I. Bukharin) wasapproved only on 5 June 1931 (Esakov, 2000, p. 109).19 At the congress he read a paper onthe origins of agriculture, in which he tried to demonstrate potential practical applicationsof his expeditions (Vavilov, 1931a).20 In other words, in early summer 1931 Vavilov’sposition was very uncertain, yet the party line suddenly changed, and the signals indicatedthat despite the vicious criticisms in the party press Vavilov was still trusted by the topleadership of the country. Most likely, the Leningrad Party Organization considered thesesignals when it supported Vavilov’s application to attend the London congress.

By that time the party leadership realized that the activists of the ‘Cultural Revolution’had failed to formulate an alternative program of agricultural research. Ideological accu-sations and calls for adopting Marxist methodology had produced no tangible results. Inpractice, the Mechano-Lamarkists had advocated mass introduction of high yielding cropvarieties from abroad. But the country had no money to fund this program, and there-fore it was found pragmatically and ideologically unacceptable. Mechano-Lamarckismwas rejected as a theory incompatible with Marxism.

Most critics of Vavilov agreed with this judgement, and in line with the previouspolicy of replacing old regime specialists with new cadres, many of these people werepromoted to chair research units in the VIR, even if Vavilov spoke out against theseappointments. Thus, for example, in 1931 Shlykov became the chair of the section forplant introduction, even if a few months earlier Vavilov publicly accused him of ignoranceand demagoguery (TsGAIPD, f. 304, op.1, d. 3. l. 50). Al’benskii was elected as secretaryof the VIR party organization, despite the fact that on 3 April 1931 Vavilov publicly calledhis methodological statements void of any substance (TsGAIPD, f. 304, op.1, d. 19. l.107–108).

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Pte Ltd

Vavilov in the years of Stalin’s ‘revolution from above’ 347

On 3 August 1931, Pravda published the Council of People’s Commissars’ resolutionon plant selection, which set out unrealistic objectives for agriculture: within 3 or 4 years’time existing varieties of grain crops had to be replaced by new ones, so that the yieldswould increase dramatically. On 11 August 1931 the party members at the VIR convenedto discuss the resolution, which had been adopted by the Regional Party Committee on 9July. The resolution authorized ‘the investigation of the Academy in Leningrad’. Al’benskiiread the resolution (TsGAIPD, f. 304, op. 1, d. 22, l. 53). The discussion was very formal.Shlykov suggested acknowledging:

‘The resolution reflects our situation. We need to take it as the guidelines for our work in the VIRand we need to correct the work of the VIR.’

Konstantin Semakin threatened to take to task those who ‘keep silence and do not assumeresponsibility for production’, among whom he meant primarily ‘specialists in selectionand geneticists’.

On 22 August 1931, another meeting discussed the measures that needed to be takenin order to implement the Regional Party Committee’s resolution (TsGAIPD, f. 304, op.1, d. 22, l. 55–56ob., 58). It was decided to establish circles for the study of dialecticalmaterialism; and it was also agreed that postgraduates would be evaluated not so much fortheir political and ideological work but their real contribution to research. The party bureauknew it had to share the responsibility for the alleged shortcomings, so to demonstrate itsactive position it formulated a long list of measures intended to improve the situation.

In order to accelerate the production of new breeds that could be used in large mechanizedagricultural production units, the section for genetics and selection is to work out a plan forsupplying selection centres with the necessary equipment, in accordance with the most recenttechnology and improved methods of selection. The plan has to be presented as soon as possible(no later than 15 November). (TsGAIPD, f. 304, op. 1, d. 22, l. 55ob.)

Vavilov realized that the institute had suffered a heavy blow. On 7 October 1931, hewrote:

This spring (it has passed by now) was not an easy time for specialists21 … Many specialists wereremoved from positions of authority. A few of them even stayed under arrest for a while, beingaccused of counter-revolutionary activities. (Cited in Savina, 1995, p. 19)

6. ‘Vae Victis’: Woe to the Conquered!

These were the very words that Vernadsky wrote in his diary in spring 1932 when hethought about Vavilov’s position (2001, p. 288). However, it was a premature assessment.22

Vavilov remained the leader of Soviet geneticists and plant breeders. This fact was demon-strated at the All-Union conference on planning genetics research and plant breeding,which took place in Leningrad on 25–29 June 1932. Of course, it was quite different fromthe grandiose academic and political event that had taken place in January 1929. Yet itwas still supported by local authorities and was extensively covered in the media. The

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Pte Ltd

348 E. I. Kolchinsky

USSR Academy of Sciences, the VASKhNIL and the LOKA organized the conference.Al’benskii, Potashnikova and Prezent sat on its organizing committee and Vavilov was thehead of the conference’s organizing committee. In his opening speech he suggested:

Making the work of plant and animal breeders more thoughtful from the genetics perspective, whilethe work of geneticists must be linked in the most decisive way with selection. (Vavilov, 1933, p. 22)

Thanks to the support given by the Leningrad Regional Party Committee and theOctober District Party Committee, Vavilov had remained in his position as the head ofthe VASKhNIL and VIR. Moreover, the Postgraduate Institute was closed, and with itsclosure G.I. Bykov disappeared from the stage (TsGAIPD, f. 304, op. 1, d. 22, l. 4–5). Inautumn 1931, when G.I. Shlykov was appointed as head of the section for new cultures andplant introduction, he immediately forced Kol’ to resign even though he had previouslysupported Kol’s ideas (TsGAIPD, f. 304, op. 1, d. 22, l. 27). Kol’ was arrested initially,and then when he was released he was forced to retire. Achieving the position he hadbeen dreaming of, Shlykov kept a low profile for a while. He would resume his struggleagainst Vavilov a few years later, when he began to support Lysenko and his ideas. But firstVavilov was to witness the departure from the institute of both Petr Artem’ev, the formersecretary of the party bureau, and Nikolai Pereverznev who had been Vavilov’s deputy andhad supported his opponents in 1931 (TsGAIPD, f. 304, op. 1, d. 22, l. 16–17).

Al’benskii, however, did start to plot against Vavilov and Kovalev. But on 9 April1932 A.S. Bondarenko requested that Al’benskii comply with the principle of undividedauthority and suggested to ‘use carefully such words as “sabotage” or “procrastination”’(TsGAIPD, f. 304, op. 1, d. 48, l. 3ob). Al’benskii got the message and transferred to theInstitute for Agricultural and Forest Melioration; as time passed, he became the head ofthis institution and abstained from taking sides in the confrontation between Vavilov andLysenko.

For a while, Prezent also ceased criticizing Vavilov. Between January and April 1932Prezent never mentioned Vavilov’s name in his papers and speeches about the class struggleon the biological front, while he stigmatized almost any other prominent biologist inLeningrad as a class enemy (Prezent, 1932). But Prezent evidently sensed that the ‘CulturalRevolution’ was about to end, and the ‘Great Break’ would soon be replaced by a ‘GreatRetreat’, which would mean first the liquidation of institutions and journals establishedduring the ‘Cultural Revolution’ and then the death of its heroes. He began looking fora patron who would be popular with the party leadership. Prezent realized that he couldnot hope for ‘collaboration’ with Vavilov and was closely watching the rise of Lysenko. Hestarted citing Lysenko more frequently. On 11 February 1932 Prezent reached an agreementwith Lysenko about their collaboration (SPF ARAN, f. 240, op. 1, d. 3, l. 1–5; d. 22, l. 12),and in summer of the same year Prezent with a group of his colleagues and postgraduatestudents went to see Lysenko, who had worked in Odessa since the autumn of 1929 (SPFARAN, f. 232, op. 1, d. 24, l. 11–20). The correspondence exchanged between Lysenko and

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Pte Ltd

Vavilov in the years of Stalin’s ‘revolution from above’ 349

Prezent shows that by the autumn of that year they had already written joint publications(ARAN, f. 1593, d. 128, l. 1), and it was these that formed the basis of Lysenkoism.

At this point Vavilov’s position became precarious. Even though with the advent of the‘Great Retreat’ some of the day-to-day criticism had subsided, he was still at the mercy ofthe party and its institutions, including the party organizations of the VIR and VASKhNIL;he was also still vulnerable to attacks launched by his own subordinates, some of whomhe had been forced to appoint and who subsequently gained positions of authority, evenif Vavilov felt they were poorly qualified for these positions. It was not long before theparty and state administration began to view Vavilov as someone who was losing powerand becoming unable to maintain order in his own fiefdom. Instead of being a paragon ofa Soviet scientist, he began to be the subject of endless investigations despite his attemptsto collaborate with the Soviet authorities. These attempts to meet party demands affectedthe language and style of his publications. In 1932, for instance, Vavilov’s publicationsincluded phrases such as ‘decaying capitalism, which is engaged in a frenzied struggleagainst scientific biology’, ‘broken chains of metaphysics’, ‘a sceptical geneticist who ispowerless against Darwinism’, ‘a mortal blow against vitalism’, a ‘biological front’, etc.,and his arguments became indistinguishable from the demagoguery of his opponents.

But his critics did not back down. Those who had failed to achieve their objectives on the‘biological front of the Cultural Revolution’ and in the Leningrad party structures, beganto concentrate their efforts on trying to attract the attention of the punitive institutions. InSeptember 1932, while Vavilov was on a research trip abroad, the People’s Commissariatof Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspection established a brigade charged with the task ofinvestigating research at the VIR. As a result of the investigation, more than 20 leadingresearchers who had supported Vavilov were arrested and sent to exile. Among themwere the corresponding members of the Academy of Sciences, G.A. Levitskii and N.A.Maksimov. It was at this point that academic debate ended and repression reigned.

The subsequent history is well known. In early 1932 the People’s Commissar forAgriculture Iakov Iakovlev instructed Vavilov to render all possible assistance to Lysenko,who had already acquired the image of a ‘talented agronomist from the masses’ (Esakov,Levina and Mikulinskii, 1987, p. 165). In order to follow these orders Vavilov had to accepta resolution adopted by the VIR Academic Council in his absence. Lysenko had presentedhis paper on ‘the question of winter crops’ to the council (Levina, 1995, pp. 50–52), andthe council had approved the paper, stipulating, however, that Lysenko’ss results had to betested by new experiments. Lysenko was not interested in the testing process. Vavilov, whowished to avoid confrontation with the authorities, tried to keep the disagreements withinthe limits of an academic discussion. He spoke about Lysenko’s research as a brilliantwork and called Lysenko’s method of vernalization ‘the most impressive achievement inselection’ (Vavilov, 1933, p. 29). However, the conflict between geneticists and lysenkoistsescalated. The fourth VASKhNIL session, which took place on 19–24 December 1936,was devoted to ‘disputable questions in genetics and selection’. Many geneticists andselectionists who spoke against Lysenko were arrested during the session.

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Pte Ltd

350 E. I. Kolchinsky

Vavilov was uncompromising once he realized that Lysenko’s activities endangered thevery existence of his discipline. It was at this moment that he said his famous words: ‘Wewill go to a stake, we will be burned but we will not surrender our convictions’. Thesewords were a challenge to the Stalinist regime, which forced any person to change his orher convictions upon the orders from above. So, at this point in the mid-1930s, Vavilov’sstruggle against Lysenko acquired political connotations. Stalin supported Lysenko whoalso had the backing of the party-state apparatus with its well-functioning mechanismof mass repression. Vavilov and his fellow geneticists and plant breeders who haddemonstrated the fallacy of Lysenko’s work in their laboratories did not have such support.This made it easy for Vavilov’s opponents to increase the pressure. Vavilov was chargedwith anti-Soviet activities and sabotage; he was arrested on 6 August 1940 and sentenced tothe death penalty. On 26 January 1943, the man who had dreamed of rescuing humankindfrom famine died of starvation in a prison in Saratov. His closest associates – the specialistin selection Leonid Govorov, geneticist Georgii Karpechenko, cytogeneticist GrigoriiLevitskii, plant breeder Konstantin Fliaksberg and a few others - were also arrested anddied in prison. Many dozens of scientists were dismissed from the academic institutionsthat had been chaired by Vavilov. Some of Vavilov’s early opponents (I.I. Prezent, B.G.Potashnikova and G.N. Shlykov) took an active part in these arrests and the persecutionof geneticists. It is also true that many former critics of Vavilov died in the year of the‘Great Terror’; among them were D. Artsybashev, P. Artem’ev, A. Bondarenko and N.S.Pereverznev. In the 1930s the VIR alone lost more employees than the total number ofbiologists who perished in Nazi Germany (Dragavtsev, 1994).23

7. Conclusions

New documents found in archival collections left by the Leningrad party administrationand the Communist Academy testify that the conflict between Vavilov and the youngerresearchers who were promoted in the period of the ‘Cultural Revolution’ for their militantMarxism and appropriate class background was far from a competition between rivalacademic schools. These documents enhance our knowledge significantly. Previously,discussions revolved around published materials and Vavilov’s letters (Beliaev, Mikulinskiiand Esakov, 1980; Esakov, Levina and Mikulinskiı, 1987; Levina, 1995; Esakov, 2008). Inthis confrontation, the scientific content of the debates (e.g. the Mechano-Lamarckist ideaof inheritance of acquired characteristics) was of little significance. Far more important wasan ability to persuade the party-state authorities that a particular research program couldproduce immediate practical results in agriculture. Vavilov’s position became increasinglyvulnerable in this respect, as the system of institutions he created under the VASKhNILumbrella was inefficient: it failed to achieve visible success in improving agriculturalproduction (Roll-Hansen, 2005, pp. 89–92).

Vavilov’s opponents were primarily motivated by ideological, political considerations.They were inspired and controlled by the party-state administration, which often acted

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Pte Ltd

Vavilov in the years of Stalin’s ‘revolution from above’ 351

through its own ‘fifth column’ in the VIR. In the years of the ‘Cultural Revolution’ thetension between the party policies and the principle of autonomy of scientific expertisereached its peak, as the party-state authorities tried to subject scientists to tight administra-tive and ideological control, while the latter attempted to retain their autonomy in research.On the surface, however, this conflict took the form of a generational conflict in science(Graham, 1987, p. 9).

The outcomes of the conflict, as we have seen, were determined by the particularalignment of forces in the top echelons of the party-state administration and by thechanging party policies. True, in 1929–1932 no one could predict which side would win inthe end. The uncertainty was produced by dramatic oscillations of the party line. Vavilovwas able to retain his position because of the ‘Great Retreat’ of 1931, when the policy ofreplacing the ‘bourgeois specialist’ with new proletarian cadres was abandoned.

In the years of the ‘Cultural Revolution’ many other prominent scientists, like V.I.Vernadsky, A.F. Ioffe and A.N. Krylov faced attacks by younger researchers supportedby the Communist Party. Yet most of them were lucky to escape direct repressions andretained their leading positions in their respective academic communities. Vavilov’s fatewas quite unusual in this respect, especially if we recollect the enormous authority andrespect he enjoyed at the peak of his career. In respect of his academic stature and politicalinfluence he had no rival in the Soviet academic establishment. Nevertheless, in 1929–1931even he became an object of vicious criticisms. True, he was able to manage the situationand survive. But he was powerless to defend some of his closest aides (N.P. Avdulov,N.N. Kuleshov, G.A. Levitskii, N.A. Maksimov, V.E. Pisarev, M.G. Popov and K.M.Chingo-Chingas).

To a great extent this unique experience can be explained by the very special positionoccupied by life sciences (as well as agricultural and medical sciences) in the Soviet Union.These disciplines were directly concerned with the social and economic sphere; they werealso perceived as most closely related to the construction of socialism. Therefore even bythe 1920s the task of making them ‘proletarian’, ‘dialectical’ and ‘Soviet’ had becomepolitically important. For this cause, a high number of postgraduate students and activistswere drafted into various Marxist societies in biology and agricultural sciences in the1920s – early 1930s. The numbers were much higher than those found in similar circlesand associations in physics, for example.

Many scientists with good academic reputation, and not just some semi-literate Bolshe-viks, voluntarily took part in this process. Among them were even a few geneticists witha solid academic background, for example, Izrail I. Agol, Nikolaı P. Dubinin, SolomonG. Levit, Aleksandr S. Serebrovskiı and Vasiliı N. Slepkov (Kolchinsky, 1999). Evenbefore the ‘Cultural Revolution’ they began criticizing biology and its particular conceptsfrom a Marxist-Leninist standpoint. Gradually a peculiar language and ritual of criticismevolved. Particularly dangerous was a discursive link between science and practice. Thisrhetoric device was employed in order to enhance the credibility of a research program byits advocates and to discredit competing research projects. Good research was expected to

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Pte Ltd

352 E. I. Kolchinsky

produce immediate practical impact. This language backfired in the years of the Stalinist‘Great Break’ when the fate of biology became inextricably linked with the politics ofcollectivization. As Stalin remarked on 27 December 1929, with the start of collectivisa-tion, the agricultural sciences had found themselves on the front line, and the disciplinesubsequently underwent a large-scale rapid institutional rearrangement (Stalin, 1955a).But with a dramatic fall in agricultural production, practitioners soon became an easytarget for political accusations.

Most poignantly, in the course of the conflict Vavilov was forced to adopt the methods,language and professional rituals of his opponents (Krementsov, 1997, p. 32). He activelyadvertised his research program and the achievements of his institutes in the Izvestiia(edited by N.I. Bukharin) and Sotsialisticheskoe zemledelie (an official newspaper of thePeople’s Commissariat of Agriculture), and at party conferences and congresses of Sovietsof the Soviet Union. He accepted the system of tight centralized planning in academicresearch. He became accustomed to compromises that he had to make for the sake ofpreserving his institute. Moreover, he supervised a large-scale project that aimed to producehigh-yielding plant and animal breeds within the shortest possible time. Vavilov madepromises to create within the Second Five-Year Plan period (1933–1937) the genetic basisfor advanced socialist agriculture and to breed high-yield varieties of cultivated plants andanimals (Vavilov, 1933). He actively defended the idea that Soviet agricultural sciencewas a unique discipline; an idea that was later exploited by Lysenko and Prezent whenthey advocated Michurinist biology as a true Soviet science.

In other words, Vavilov encountered many elements of Lysenkoism even before Lysenkoentered the historic stage, if we understand Lysenkoism not as a set of scientific orpseudo-scientific ideas but as the language and social practice that appeal to the party-state,and invite it to become a supreme arbiter in intra-disciplinary controversies and measurethe success of a research program by criteria external to science. Recent research onLysenkoism in other national contexts (Japan, France and Italy) shows that confrontationbetween competing groups of scientists is unavoidable in any academic community(Fujioka, 2010, 2013). However, the forms and outcomes of this confrontation in the SovietUnion were predetermined by a particular vision of science that was promoted by theparty-state structures. In normal situations in most countries, the results of competitionbetween research groups have been, and still are, negotiated by scientists, the stateand society, but in the Soviet Union they were ultimately solved by the party-stateadministration alone.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to Nikolai Goncharov and Sergei Shalimov, whoassisted me with collecting materials for this paper and shaping its ideas. Marina Loskutovaboth translated this paper from Russian and helped me to clarify some of its key statements.

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Pte Ltd

Vavilov in the years of Stalin’s ‘revolution from above’ 353

I am also indebted to Ida Stamhuis, Claire Neeshan, Anastasia Fedotova and the anony-mous reviewers of Centaurus. I did my best to consider and respond to their criticismswhile working on the final version of this paper. This research was been supported by theRussian Foundation for Humanities, grant no. 12-03-00239a.

NOTES

1. A bibliographic reference book on N.I. Vavilov includes more than 1300 works in Russian and morethan 100 works in foreign languages that are available in Russian libraries (Petrov, Osiaeva andIvoilova, 2012). Ninety-four works on Vavilov and his collaborators were published between 2008and 2011. More than 100 works were published in 2012 – the year of his 125th anniversary.

2. For more details see: Soyfer, 1994; Krementsov, 1997; Roll-Hansen, 2005; Kolchinsky, 2007; Esakov,2008; Pringle, 2008; and Nabhan, 2008.

3. In subsequent editions Shnol’ (2001) considerably modified the title, so acknowledging that thesituation had been much more complex than a simplistic binary opposition.

4. Here I have no opportunity to discuss this campaign in leading Russian newspapers and TV channels.For details see my paper ‘Current attempts at exonerating “Lysenkoism” and their causes’ producedfor a volume on Lysenkoism edited by W. deJong-Lambert (forthcoming).