-

8/13/2019 My Life Under The Trees: The Story of a Lost Boy from South Sudan

1/19

-

8/13/2019 My Life Under The Trees: The Story of a Lost Boy from South Sudan

2/19

PRAISEFOR

MYLIFEUNDERTHETREES

Abraham Mangars account of his journey from the South

Sudan to Omaha opens the world of the lost boys who were

wrenched from their families during turbulent times in their

homeland. Each boy has a unique story, and Abraham tells his

tale with an honest heart, placed in the historical context of the

time. He survived to tell the experiences he and others faced, and

we are enlightened by his willingness to tell the truth.

Steve Jordon,Te Omaha World-Herald

Author,Te Oracle & Omaha: How Warren Buffett

And His Hometown Shaped Each Other

In Abrahams deeply personal account, he not only gives

clarity to this important part of South Sudans history and helps

you gain a greater appreciation for the struggle and hardshipsendured, he also inspires us with a story of the strength and

resiliency of the human spirit as well as a story of Gods presence

and providence, even in the darkest of places and circumstances.

Rev. Gregory Berger,

Messiah Lutheran Church, Omaha, Nebraska

-

8/13/2019 My Life Under The Trees: The Story of a Lost Boy from South Sudan

3/19

The Story of a Lost Boyfrom South Sudan

MY LIFE- UNDER -

THE TREES

ABRAHAMMANGARWITHJIMTHOMPSON

JIENGPUBLISHING

Omaha, NE

-

8/13/2019 My Life Under The Trees: The Story of a Lost Boy from South Sudan

4/19

2014 Abraham Mangar. All rights reserved. No part o this book maybe used or reproduced by any means, graphic, electronic or mechanical,including photocopying, recording, taping or by any inormation storageretrieval system without the written permission o the publisher except in the

case o brie quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Jieng Publishing books may be ordered rom your avorite bookseller.www.JiengPublishing.com

Jieng Publishingc/o CMI13518 L. StreetOmaha, NE 68137

Because o the dynamic nature o the internet, any web addresses or linkscontained in this book may have changed since publication and may nolonger be valid.

ISBN: 978-0-9913365-0-0 (paperback)ISBN: 978-0-9913365-1-7 (Mobi)ISBN: 978-0-9913365-2-4 (epub)

LCCN data on file with the publisher

Printed in the USA10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

-

8/13/2019 My Life Under The Trees: The Story of a Lost Boy from South Sudan

5/19

AbrahamwithhiswifeAcholandtheirdaughteralsonamedAchol.

-

8/13/2019 My Life Under The Trees: The Story of a Lost Boy from South Sudan

6/19

CONTENTS

PREFACE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1

A BRIEFHISTORYOFSOUTHSUDANANDTHESPLM/A . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

INTRODUCTION. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7

CHAPTER1 THEPROPHECYUNDERTHETAMARINDTREE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

CHAPTER2 PLEAFORSAFETYINTHEWILDERNESS. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

CHAPTER3 REST, REVIVAL, ANDTHERIVERS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

CHAPTER4 ONESHOTMEANSWEFOUNDWATER . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

CHAPTER5 DEADLYCROSSINGINTOETHIOPIA . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

CHAPTER6 SUCHANUNDESIRABLELIFE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

CHAPTER7 LONGLINESTOSEETHEDOCTOR . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

CHAPTER8 NEVERADAYWITHOUTDEATH . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

CHAPTER9 EATINGJUSTTOSURVIVE. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .43

CHAPTER10 GROUPTENANDTHEWILDANIMALS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

CHAPTER11 NEVERLOSEYOURHOSPITALCARD. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53

CHAPTER12 THEDIRTDOESNOTLIE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 59

CHAPTER13 UNITEDNATIONSRATIONSARRIVE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65

CHAPTER14 COLLECTINGGRASSBRINGSMOREPROBLEMS. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71

CHAPTER15 A BEDFORGEUANDOTHERSURPRISES. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .77

-

8/13/2019 My Life Under The Trees: The Story of a Lost Boy from South Sudan

7/19

CHAPTER16 A SPECIALGUEST . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 85

CHAPTER17 MILITARYTRAINING . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93

CHAPTER18 THEWEAPONISOURFATHERANDMOTHER . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 99

CHAPTER19 WHATKINDOFCAMPISTHIS?. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107

CHAPTER20 PUNISHMENT. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 113

CHAPTER21 GEUBECOMESABRAHAM . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 117

CHAPTER22 HOWTOMAKEABEDINCAMP . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 119

CHAPTER23 SPLM/A ISOUSTEDFROMETHIOPIA . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 125

CHAPTER24 REFUGEESINOUROWNCOUNTRY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 129

CHAPTER25 FIGHTINGSTARVATION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 133

CHAPTER26 WORSTPOSSIBLENEWS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 141

CHAPTER27 UNPLEASANTDUTIESANDTROUBLEDEYES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 147

CHAPTER28 WARREACHESTHEBOYS CAMP. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 151

CHAPTER29 A LITTLERELIEFFORGEU . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 159

CHAPTER30 GODMUSTBECLOSERTOTHEM . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 165

CHAPTER31 THEKAKUMAREFUGEECAMP. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 171

CHAPTER32 LIVINGOFFTHELAND. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 181

CHAPTER33 REFLECTIONSONTHESPLM/A. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 187

-

8/13/2019 My Life Under The Trees: The Story of a Lost Boy from South Sudan

8/19

As one o the Lost Boys o Sudan, I have always elt thatone o the hardest parts o our story is the one sometimestold by those who did not actually live that story. Also, I would

like to clariy that most o us were not separated rom our parents

because our villages were attacked in the middle o the night andwe had to run to a sae place, although that may have happened

to some people that I did not meet. I just hated this part o the

history because that makes our parents look like they were the

most careless parents in the entire world. In reality, we were not

boys who got lost, magically met somewhere, and somehow led

ourselves to saety many hundreds o miles away. Like I state in

the beginning o the book, Dr. John Garang, himsel, ordered the

South Sudanese governors to send boys rom different regions to

Ethiopia so they could (eventually) attend school.

My biggest motivator or writing this book, though, is the

act that many o my ellow Lost Boys think some o the things we

went through are degrading to our image and also humiliating,

but I simply look at them as the scars o our many struggles.

o me, there is nothing embarrassing about our past since, most

o the time, we had no other choice but to try to survive. For

example, i I did not try to eat things that looked inedible, then

I might not be here todayI could have died o hunger. Since

most o the Lost Boys in my new hometown in Omaha, Nebraska,

PREFACE

-

8/13/2019 My Life Under The Trees: The Story of a Lost Boy from South Sudan

9/19

MY LIFE UNDER THE TREES 2

are not rom the same groups in the Pignudo reugee camp,

every time we were together we told each other what happened

in our groups. Te stories sound unny now, even though the

experiences were horrible. I know that or most people readingthis book, it will be hard to believe that we are still alive afer

some o the things that happened to us. Tere are also parts in

the book that can make you laugh, tear up, and shake your head.

When I and five other Lost Boys immigrated to Omaha in

2001, we were sponsored by Lutheran Family Services and settled

into a house provided by that organization. About three weeks

later, a man named Bob Head and his wie Willow came to seeus and offered their help afer reading an article about us in the

Omaha World Heraldnewspaper. Te next week, Bob talked to

his pastor at Christ the King Church to see i they would sponsor

us, and they did. In the meantime, Bob helped us find jobs and

an apartment.

Afer living in America or our years, I decided to get a

commercial class A drivers license so I could drive semi trucks.I called Bob Head to see i he could help me find a commercial

driving school where I could be trained and get my license. Afer

driving cross-country or five months, I knew I needed a job

closer to home. I was happy to quit cross-country driving due to

the truck-stop ood and, worst o all, the loneliness.

Bobs riend, Jim Tompson, gave me a job driving or the

company at which he worked. Jim and I came to know each other

better and became close riends. Every time we had a chance to

talk, I would tell him a little bit more about the Lost Boys beore

we came to the United States.

He ofen told me that I should write a book about my

experiences because it would be so interesting. Afer thinking

about it or some time, I called Jim and asked him i he had the

time to edit my memoir i I wrote it. Afer he read my first three

pages, he asked many questions to help me clariy the narration

o the story. So as I wrote, he helped me greatly; sometimes the

editing went ast and sometimes we would spend a lot o time

editing just a hal a page until the book was finally done. Te

-

8/13/2019 My Life Under The Trees: The Story of a Lost Boy from South Sudan

10/19

-

8/13/2019 My Life Under The Trees: The Story of a Lost Boy from South Sudan

11/19

Sudan has not been ree rom civil war since 1955. Tere wasalways a divide between the Arab-Muslim north o Sudanand the Arican-Christian south o Sudan. Tis divide was caused

by the uneven distribution o natural resources and development,

as well as an effort by the north to impose Islam on the Christiansouth. Even though most o the natural resources were located

in the south, the primarily Arabic north held all o the power

by using the South-Sudanese resources or urther development

in the north, to the exclusion o the south. In addition, South-

Sudanese students were generally only allowed to study at higher

levels o education i they became Muslim.

Because o these and other inequities, the first civil war

broke out in 1955 when some South Sudanese ormed a

rebellion that was called the Anyanya (which means snake/

scorpion venom in the Madi language). Te Anyanya lasted

or seventeen years until the Addis Ababa Agreement and

peace treaty was signed in 1972.

As time passed, however, the north started violating the

terms o the agreement, so actions in the south started meeting

secretly to discuss these inequities and treaty violations. Te

government in Khartoum (Sudans capital city which is located

in the northern part o the country) began to suspect rebellion

in the south. So it ordered Unit 105, a group o five-hundred

A BRIEFHISTORYOFSOUTH

SUDANANDTHESPLM/A

-

8/13/2019 My Life Under The Trees: The Story of a Lost Boy from South Sudan

12/19

MY LIFE UNDER THE TREES 6

southern soldiers stationed in Mading-Bor (now simply known

as Bor own) suspected o being rebels, to be reassigned to the

north so the government could monitor their activities. Unit

105 was under the command o Kerubino Kuanyin Bol and theyreused to obey the order, so the government sent troops to Bor

to orce the relocation.

When the government troops arrived in May 1983, Unit 105

opened fire on them, retreated into the bush, and later escaped to

Ethiopia. A day later, Unit 104, under the command o William

Nyoun Bany, killed some government officials in Ayod and then

fled to Ethiopia, where they joined orces with Kerubino andUnit 105.

Many South Sudanese intellectuals sympathetic to the

rebellion had gathered in Bor to support the rebellion. However,

when Units 105 and 104 attacked the government troops, they

had to pretend (or their own security) that they were not part o

that rebellion.

Only when the South-Sudanese intellectuals knew it was

sae could they lead students, police, and others to Ethiopia and

join Units 105 and 104 who were already there. Tis is where

they ormed the SPLM/A (Sudan Peoples Liberation Movement/

Army). Dr. John Garang, Kerubino Kuanyin Bol, William Nyoun

Bany, and Salva Kiir Mayardit, who is the current president o

South Sudan, became the leaders o the SPLA (the Army). Te

political-movement branch (SPLM) was led by Joseph Oduho,

Martin Majier Gai, and others.

-

8/13/2019 My Life Under The Trees: The Story of a Lost Boy from South Sudan

13/19

Several months afer the SPLM/A organized in the mid 1980s,some o the SPLA officers returned to their villages orpolitical visits. Tese visits were an effort to send rebel members to

encourage the local men to join the SPLA. During these enlistment

campaigns, the villagers were not told exactly what they wereabout to get themselves into; they were just told what they wanted

to hearlike they would be given ree weapons or the protection

o their cattleand this encouraged them to volunteer. Many boys

and men considered this good news and they lef with the SPLA.

Afer several years, some o the newly trained and ully

equipped SPLA soldiers returned to their villages or visits. o

those o us who had not gone away to train, it was as i we had

missed out on something important. Tree o my amily had

already joined, and every time one o my cousins or uncles who

was in the military visited, I would go to him so I could check out

his gun and ask questions. We younger boys always wished we

were old enough that we could be in the army and have an AK-

47. Everything about military lie sounded and looked good to

me in my small Dinka village in the Bor region o South Sudan,

and I would copy the way the new soldiers walked.

One day an SPLM/A soldier who was passing by decided to

stop at the tamarind tree where my riends and I were playing.

He told us to gather around him, and he started to teach us the

INTRODUCTION

-

8/13/2019 My Life Under The Trees: The Story of a Lost Boy from South Sudan

14/19

-

8/13/2019 My Life Under The Trees: The Story of a Lost Boy from South Sudan

15/19

1

As a six-year-old, I didnt think leaving home meantbeing separated rom my parents; it sounded morelike visiting some relatives in another village. I thought that

maybe I would be gone or a ew years because I remembered

that many young men rom my home area had lef to receivemilitary training and had been gone or about that same period

o time. So I was hoping I would return afer about two years to

see my parents.

But as it turned out, that did not happen. Neither our parents,

nor we, had any choice in this matter. Our parents rights were

taken away when Dr. John Garang ordered the boys in South

Sudan to go to Ethiopia or schooling. Dr. Garang ordered the

governors o all the southern states to collect the boys in their

villages with no regard or how the parents might eel. All o the

village chies were called to a special assembly where they were

told that each o them had to register all o the boys in his village.

Our governor took a stick, showed it to the chies, and said,

Te youngest has to be at least the height o this stick, and i you

ail to bring the boys rom your village by the date mentioned,

you will be arrested and your cattle will be confiscated. Te

chies did not question these directives, and they registered every

boy in their villages with or without the parents knowledge. So

I, my ten-year-old brother Nhial, and our o our cousins were

THEPROPHECYUNDER

THETAMARINDTREE

-

8/13/2019 My Life Under The Trees: The Story of a Lost Boy from South Sudan

16/19

MY LIFE UNDER THE TREES 10

registered to go to Ethiopia by our chie. My our-year-old

younger brother Jacob was too small to go.

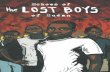

The Lost Boys of Sudan

Most of the children who became known as

the Lost Boys of Sudan were from the Dinka and

Nuer ethnic groups, which are the primary tribes in

South Sudan. While many were ofcially taken by

the SPLM/A for schooling, others were the survivors

of the destruction and devastation inicted on

South Sudan by the Khartoum government in the

north that was trying to squash rebellion.

The common local term for those children who

later became known as the Lost Boys was jesh al-

hamer, which literally means Red Army in Arabic.It came from the Russian/Communist term for those

who rebelled against the current government. It is

commonly thought to refer to children in the militia

who were under the age of eighteen, but became

a term that refers to all of the boys and girls who

were taken by the SPLM/A. In fact, there is now aRed Army Foundation in South Sudan.

It is also important to note that the term

Lost Boys of Sudan was coined by aid workers

in the Ethiopian refugee camps. It referred to

the characters in Peter Panby J.M. Barrie called

the Lost Boys, who were orphans left to fend for

themselves.

-

8/13/2019 My Life Under The Trees: The Story of a Lost Boy from South Sudan

17/19

ABRAHAM MANGAR 11

Many o the parents o the boys, but especially our mothers,

were not happy about the idea that the SPLM/A was going to

take their boys to Ethiopia or schooling. Most o them would

cry and curse the chies and the SPLM/A leaders at the same

time or taking their children away at such a young age. We were

ignorant about such things, however, and the journey to Ethiopia

just sounded exciting to us.

Te SPLM/A leaders tried to make it sound interesting by

telling our parents and us that we would live in a well-organizedplace and that we would do nothing but go to school and study.

Tey said our ood would be prepared by cooks like they did here

in our school, but it was still hard to convince our parents. Yet

Dr. John Garang, 19452005

John Garang was a Dinka who completedhis higher education in Tanzania and the United

States and earned his Ph.D. in economics in 1981

at Iowa State University. Upon his return to South

Sudan, he became a leader in the rebellion. After

the 1972 peace agreement, he remained in the

military and due to his intelligence and abilities

as a military strategist, he eventually rose to a

military-planning position within the Khartoum

government. However, when sent to Bor in 1983 to

quell the Unit 105 rebellion, he sided with his own

people and ed with the rebels to Ethiopia and

started the SPLM/A. Garang died in a helicopter

crash in 2005 and did not live to see South Sudan

become an independent nation at midnight on

July 9, 2011.

-

8/13/2019 My Life Under The Trees: The Story of a Lost Boy from South Sudan

18/19

-

8/13/2019 My Life Under The Trees: The Story of a Lost Boy from South Sudan

19/19

ABRAHAM MANGAR 13

or change your position. I you need to relieve yoursel, dont go

so ar that we cannot hear you, just in case something happens.

Afer all o the instructions were given, we were told that it

was time to leave. Some SPLM/A soldiers went ahead o us, somewalked on each side o us, and another group stayed behind or

about hal an hour to make sure that there was nobody lef. Te

lead army group was to make sure that there were no enemy

ahead o us and to find drinkable water.

On the first day o our journey, around our thousand o us

only walked or about three hours and then slept on the ground

or the rest o the night. We walked bareoot on cattle or animaltrails through the grassland carrying nothing. Te next day, we

stayed under the trees waiting or cooler conditions. At around

three oclock in the afernoon, a whistle was blown to inorm

everybody that we were about to leave.

Te first whistle was to inorm us that we would be leaving

in thirty minutes, and then a second whistle meant to assemble

and prepare to leave. We assembled by subdivision and all o the

boys in Makuac (my subdivision that indicated where I was rom

in the Bor) gathered. Afer about ten minutes, it was announced

that we would be leading the way that day. We were so happy to

hear that our subdivision was the one to lead the way, and we

immediately lef going toward the east.