Municipal councils, international NGOs and citizen participation in public infrastructure development in rural settlements in Cameroon Ambe J. Njoh * Urban & Regional Planning Program, Department of Geography, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA Keywords: Cameroon Citizen participation Public infrastructure Self-help Rural settlements abstract The study reported in this paper is premised on a belief in citizen participation (CP) as a viable cost- saving strategy for public infrastructure provisioning in rural human settlements in particular, and in the development process in general, in Africa. The prowess of CP is widely acknowledged in the development literature. However, there is a dearth of knowledge on how to go about promoting CP especially in rural human settlements. The study contributes to efforts to reverse this situation by highlighting the activities of major institutional actors involved in CP initiatives in public infrastructure development in rural Cameroon. One international non-governmental organization (NGO), Helvetas, and four government rural councils based in the Northwest Region of Cameroon constitute the empirical referent for the study. It is revealed that the NGO served as the main source of funds, technical and organizational expertise, while the councils coordinated and oversaw the CP activities designed to manage and maintain the public infrastructure projects. It is also shown that exogenous factors (e.g., interference by national authorities) and endogenous problems (e.g., scarcity of skilled labour) conspired to thwart the efforts of the councils. Furthermore, the tendency on the part of national authorities to appropriate locally-realized projects was identified as a critical barrier to CP. The paper concludes that the willingness of citizens to contribute in-kind or financially to any given self-help infrastructure project is contingent upon the extent to which they perceive the project as veritably theirs. The Cameroonian experience holds potentially valuable lessons for CP efforts in rural infrastructure development in other developing countries. Ó 2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Introduction The growing problem of resource scarcity means orthodox development strategies that depend on resource input from national governments are unlikely to succeed in sub-Saharan African countries. This dictates an urgent need for alternative strategies. One strategy that is gaining increasing popularity in this regard is citizen participation (CP) (Madu & Umebali, 1993; Njoh, 2002, 2003, 2006; Page, 2005). Also known as ‘self-reliant devel- opment’ or ‘local economic development’ (Binns & Nel, 1999), this strategy is contextually-relevant and people-centered. As such, it is compatible with post-modern thinking that frowns on the ambi- tious schemes and one-size-fits-all prescriptions characteristic of orthodox international development initiatives. However, there is a dearth of knowledge on the strategy. What does it portend in practice? Self-help projects, the appellation notwithstanding, involve more than local citizens. These projects typically involve extra-community entities. Which are these enti- ties and what are their respective roles in the CP process? The study reported in this paper addresses these questions through an anal- ysis of the respective roles of Helvetas, an international NGO and government councils in self-help development projects in select rural municipalities in the Northwest Region of Cameroon. The study is premised on a belief in CP as a potentially viable cost- saving strategy in the development policy field in Africa. In the next section, the paper begins with an overview of the debate surrounding the notion of CP particularly in the context of planning and community development in Africa. Next, it presents the research methodology. Subsequent to this, it describes the institutional context of rural development planning in Cameroon. Then, it presents the main findings of the inquiry. Finally, and prior to the conclusion, it discusses the findings and identifies some of major factors believed to impede CP efforts in the target councils and communities. * Tel.: þ1 813 974 7459; fax: þ1 813 974 4808. E-mail address: [email protected] Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Habitat International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/habitatint 0197-3975/$ e see front matter Ó 2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2010.04.001 Habitat International 35 (2011) 101e110

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

lable at ScienceDirect

Habitat International 35 (2011) 101e110

Contents lists avai

Habitat International

journal homepage: www.elsevier .com/locate/habitat int

Municipal councils, international NGOs and citizen participation in publicinfrastructure development in rural settlements in Cameroon

Ambe J. Njoh*

Urban & Regional Planning Program, Department of Geography, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA

Keywords:CameroonCitizen participationPublic infrastructureSelf-helpRural settlements

* Tel.: þ1 813 974 7459; fax: þ1 813 974 4808.E-mail address: [email protected]

0197-3975/$ e see front matter � 2010 Elsevier Ltd.doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2010.04.001

a b s t r a c t

The study reported in this paper is premised on a belief in citizen participation (CP) as a viable cost-saving strategy for public infrastructure provisioning in rural human settlements in particular, and in thedevelopment process in general, in Africa. The prowess of CP is widely acknowledged in the developmentliterature. However, there is a dearth of knowledge on how to go about promoting CP especially in ruralhuman settlements. The study contributes to efforts to reverse this situation by highlighting the activitiesof major institutional actors involved in CP initiatives in public infrastructure development in ruralCameroon. One international non-governmental organization (NGO), Helvetas, and four governmentrural councils based in the Northwest Region of Cameroon constitute the empirical referent for the study.It is revealed that the NGO served as the main source of funds, technical and organizational expertise,while the councils coordinated and oversaw the CP activities designed to manage and maintain thepublic infrastructure projects. It is also shown that exogenous factors (e.g., interference by nationalauthorities) and endogenous problems (e.g., scarcity of skilled labour) conspired to thwart the efforts ofthe councils. Furthermore, the tendency on the part of national authorities to appropriate locally-realizedprojects was identified as a critical barrier to CP. The paper concludes that the willingness of citizens tocontribute in-kind or financially to any given self-help infrastructure project is contingent upon theextent to which they perceive the project as veritably theirs. The Cameroonian experience holdspotentially valuable lessons for CP efforts in rural infrastructure development in other developingcountries.

� 2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Introduction

The growing problem of resource scarcity means orthodoxdevelopment strategies that depend on resource input fromnational governments are unlikely to succeed in sub-SaharanAfrican countries. This dictates an urgent need for alternativestrategies. One strategy that is gaining increasing popularity in thisregard is citizen participation (CP) (Madu & Umebali, 1993; Njoh,2002, 2003, 2006; Page, 2005). Also known as ‘self-reliant devel-opment’ or ‘local economic development’ (Binns & Nel, 1999), thisstrategy is contextually-relevant and people-centered. As such, it iscompatible with post-modern thinking that frowns on the ambi-tious schemes and one-size-fits-all prescriptions characteristic oforthodox international development initiatives.

However, there is a dearth of knowledge on the strategy. Whatdoes it portend in practice? Self-help projects, the appellationnotwithstanding, involve more than local citizens. These projects

All rights reserved.

typically involve extra-community entities. Which are these enti-ties andwhat are their respective roles in the CP process? The studyreported in this paper addresses these questions through an anal-ysis of the respective roles of Helvetas, an international NGO andgovernment councils in self-help development projects in selectrural municipalities in the Northwest Region of Cameroon. Thestudy is premised on a belief in CP as a potentially viable cost-saving strategy in the development policy field in Africa.

In the next section, the paper begins with an overview of thedebate surrounding the notion of CP particularly in the context ofplanning and community development in Africa. Next, it presentsthe research methodology. Subsequent to this, it describes theinstitutional context of rural development planning in Cameroon.Then, it presents the main findings of the inquiry. Finally, and priorto the conclusion, it discusses the findings and identifies some ofmajor factors believed to impede CP efforts in the target councilsand communities.

A.J. Njoh / Habitat International 35 (2011) 101e110102

Citizen participation in spatial and developmentplanning in Africa

Planners in Africa are yet to fully embrace the concept of citizenparticipation despite the concept’s deep roots in the continent’sindigenous ethos and contemporary popularity in other parts of theworld. Throughout the continent, the view of planning as theexclusive domain of experts and government bureaucrats that wasinherited from colonial authorities is only beginning to wane. Ininstances involving international development entities such asHelvetas, which often mandate the inclusion of plan beneficiariesas a conditio sine qua non for funding, authorities often resort tomaking no more than token efforts to enlist citizen participation.Resulting from this is what Kamete (2006) has characterized as the“participation farce.” Commenting on planning practice inZimbabwe, Kamete (2006: p. 359), observed that, “spatial planningpractices inevitably confine public participation to the periphery.The most that citizens can do is provide information and raiseobjections.” More scathing criticisms charge that participatorydevelopment initiatives possess the potential for tyranny becauseof their inherent ability to promote the unjust and illegitimateexercise of power (see e.g., Cooke & Kothari, 2001a). Yet, currentthinking in planning and the worsening problem of resource scar-city accentuate the need to actively involve citizens as a cost-savingstrategy in the planning process. From the foregoing, it is clear thatthe debate surrounding the role of CP in the development processremains vibrant.

The debate

Citizens have always participated in the spatial planning processthroughout the world. This is particularly true when spatial plan-ning is taken to mean the making and shaping of human settle-ments or as others put it, ‘the production of livable space’(e.g., Campbell, 2002; Kamete, 2006; Yiftachel & Huxley, 2000).Here, no distinction is made between the act of altering spatialstructures, which humans spontaneously undertake as they seek tofulfill their real or perceived needs and the systematic and rationalordering of human activity in space undertaken by professionalplanners. To be sure, spontaneous human behaviour has done a lotmore than the deliberate efforts of professional planners to createthe extant global built environment. This notwithstanding, theliterature dedicated to citizen participation in the development ofbuilt space remains sparse and controversial. The controversy isover the role of citizens in themaking of plans and the enforcementof planning provisions. Some critics of citizen participation (CP) inplanning contend that particularly because citizens lack expertisein planning, their participation tends to be counterproductive,costly and disruptive to the routine of planning authorities andinstitutions (cf., Sutton, n.d.). Additionally, CP is said to be time-consuming at best and wasteful at worst. Others argue that citizenparticipation is exploitative and repressive, especially when itrequires that citizens contribute in-kind or in-cash to the realiza-tion of projects that are supposed to be the responsibility of thestate (Smith, 1992). Yet, others have contended that citizenparticipation possesses no economic value, particularly becausework involving unpaid labour such as that contributed by citizensat large is usually of poor quality and frequently has to be re-done(Njoh, 2005). More vituperative characterizations lambaste citizenparticipation as devoid of substance and vulnerable to manipula-tion by development agents bent on realizing their own ulterioragendas masqueraded as the community’s will (Cooke & Kothari,2001a). Those who see participation in this extreme negativelight charge that it is “tyrannical” on the following three levels(Cooke & Kothari, 2001b: pp. 7e8): ‘tyranny of decisionmaking and

control,’ wherein facilitators of participation typically overrideextant legitimate decision-making processes; ‘tyranny of thegroup,’ in which group dynamics are manipulated to buttress theexisting power structure; and ‘tyranny of method,’ connotinga situation in which participatory methods introduced by changeagents supplant more fruitful alternatives.

These fierce and overtly melodramatic criticisms appear mis-placed. This assertion is especially apropos once account is taken ofthe consequences of non-participatory planning as is the case inorthodox top-down initiatives. Community participation (CP) asa development strategy, like any other in the history of moderndevelopment, is constantly evolving. From its early days when itentailed little more than citizens participating as manual labourersin public works projects (Nye, 1963), CP currently requires devel-opment agents to craft new approaches and methods for interact-ing with, learning and knowing from, members of projectbeneficiary communities. A leading proponent of CP, RobertChambers, argues that poverty reduction efforts in developingcountries are likely to be more successful when members of thetarget populations are afforded the opportunity to analyze andarticulate their own needs as well as participate in efforts toaddress these needs (see e.g., Chambers, 1995, 1997). A widely heldview among proponents is that CP helps to ensure that planningdecisions and policies reflect the interests of the plan beneficiaries(cf., Sutton, n.d.). Another popular view is that CP enhances not onlyplanning efficiency but also sustainability (Kamete, 2006).Communities are more likely to identify with planning policies,decisions and outcomes if they are party to the plan-makingprocess. Chambers (1995) does a good job to allay the concerns ofcritics who charge that CP is employed by development agents benton realizing their own ulterior agendas. He argues that, to makethings better for the poor, development initiatives “will have toquestion conventional concepts of development; to challenge ‘us’to change, personally, professionally and institutionally; and tochange the paradigm of the development enterprise” (Chambers,1995: p. 204). More importantly, contemporary developmentefforts seek to place CP in a political context and tie it to issues ofpopular agency (Hickey & Mohan, 2004).

The popularity of CP in modern Africa is, however, not exclu-sively a function of its real, potential or theoretical merits. Rather,the popularity of this development tool is rooted in ideology. Twoideological perspectives, namely Western modern democracy andpopulism, have been especially influential (Midgley, 1986; Njoh,2003). Western modern democratic ideals advocate politicalparticipation. However, the concept of participation within thisframework is not founded on classical notions of representativedemocracy but on what some have branded neighbourhooddemocracy (see e.g. Lucas, 1956; Midgley, 1986; Pennock, 1879;Schumpeter, 1942). From this perspective, meaningful involve-ment of the citizenry is best achieved when citizens are organizedinto small and manageable groups (Njoh, 2003). This thinkingbecame a key element in the foundation of efforts to promotedevelopment in what were at the time emerging independentnations in Africa during the 1960s. In this regard, policy-makers inAfrica were urged to partition human settlements into small anddistinct groups. Njoh (2003) observes that this recommendationwas based on the erroneous assumption that human settlements inAfrica were essentially unorganized agglomerations of humanbeings. Yet, organization, particularly along the lines of extendedfamilies, tribes and ethnicity, has always been a crucial andconspicuous attribute of African human settlements.

As for populism, it is based on two important assumptions. Thefirst is that virtue resides with ordinary citizens, who by the way,are in the overwhelming majority (Midgley, 1986; Njoh, 2003:p. 87; Wiles, 1969). The second assumption is that ordinary citizens

A.J. Njoh / Habitat International 35 (2011) 101e110 103

are victims of exploitation by an arrogant and rigid politico-administrative machinery.

These two assumptions have been instrumental in informingefforts to promote the notion of self-help and self-sufficiency asimportant goals of development in Africa, especially in the 1950sand 1960s. Efforts to promote cooperatism, communitarianism andsocialism have also drawn inspiration from populism. Here, it isimportant to note that populism is not entirely an importedideology in Africa. Traditional African politico-administrativesystems are replete with elements of populism. Perhaps the best-known instance in which this ideology was promoted on a large-scale basis in modern times was in Nyerere’s Tanzania. The latePresident Julius Nyerere was forceful in promoting the populistnotion of ‘familyhood’ or what he called in Kiswahili, Ujamaa. Thebackbone of Ujamaa, Nyerere proclaimed, was the extended family.This, Nyerere believed constituted the basis of what would havebeen an indigenous brand of African socialism (Khapoya, 1998).Nyerere’s philosophy was inspired by the fact that in pre-colonialAfrica, communities were organized into well-knit networks ofextended families, which embraced a collective ethos in whichcritical resources such as land were communally owned andshared.

In Cameroon, the CP tradition was fostered in the Anglophoneregion by the British colonial policy of ‘indirect rule,’ whichencouraged self-reliant development. Kwo (1984, 1986) notes thatearly community development efforts in the region focusedparticularly on education, agriculture, women, and health care.Participants in the community development field included, interalia, Christianmissionaries, colonial corporations, international andlocal philanthropic agencies, and the colonial government.

The institutional context of rural development in Cameroon

For more than three decades following independence in 1960,Cameroon functioned under a highly centralized governmentstructure. The country’s 1961 Constitution established two deci-sion-making bodies, the Presidency and the National Assembly,which operated at the national level (Ndongko, 1974). These insti-tutions were endowed with enormous political and economicpowers and were solely responsible for matters relating to national

Table 1Institutional actors in Cameroon’s rural development policy field.

Item Institutional body Nationality Sector

01. Ministry of Agriculture Domestic Gov’t02. Ministry of Public Works Domestic Gov’t03. Ministry of Women’s Affairs Domestic Gov’t04. Ministry of Mines, Energy & Water Domestic Gov’t05. Ministry of Public Health Domestic Gov’t06. Ministry of Basic Education Domestic Gov’t07. Ministry of Culture Domestic Gov’t

08. Ministry of Forestry & Natural Resource Protection Domestic Gov’t09. Parent Teacher Association Domestic Commun

10. Association of Women and Progress Domestic NGO11. Rural Training Support Unit Domestic NGO12. Positive Vision Domestic NGO13. Local Development Initiative Support Service Domestic NGO14. French Association of Progress Volunteers (AFVP) French Int’l NGO15. CARE International Multi-

national???Int’l NGO

16. German Volunteer Service (DED) German Int’l NGO17. German Technical Cooperation (GTZ) German Int’l NGO18. Dutch Volunteer Service (SNV) Dutch Int’l NGO19. Swiss International Cooperation (Helvetas)

(Agency discontinued its activities in Cameroonin 2007 after 40 years of operation).

Swiss Int’l NGO

and local development planning, economic policies, nationalbudgeting, and taxation. Under the Second Five-Year DevelopmentPlan, the country was divided into 6 administrative regions, 39divisions and 129 sub-divisions. The June 1972 Decree creating theUnited Republic of Cameroon also raised the number of adminis-trative regions from 6 to 7 and re-named them provinces, whileretaining the same number of divisions and sub-divisions. Withinthis framework, rural development fell under the auspices of RuralAction Committees, which were chaired by sub-divisional officers(sous-prefets). Within this set-up all policy initiatives were formu-lated by national-level bureaucrats, with local authorities havinghardly any say.

Cameroon embarked on a course towards government decen-tralization in January 1996when the government promulgated LawNo. 96-06, which effectively amended the 1972 Constitution(Ischer, Tamini, Asanga, & Sylla, 2007). A major decentralizationinitiative, the holding of municipal elections, was also undertakenin 1996. The country has also witnessed a number of territorial re-organization activities. Currently, it includes 10 administrativeregions (previously, provinces), 56 administrative divisions(départements) and 399 municipalities.

The rural development policy field in Cameroon now includesseveral institutional actors that fall under four broad categories,namely government ministerial bodies, local non-governmentalorganizations (NGOs), and international NGOs. The most notable ofthese institutional actors, their status and major roles in the ruraldevelopment policy field are summarized in Table 1.

Municipal councils occupy the lowest rung of the governmentadministrative ladder in Cameroon. They are charged with theresponsibility of executing local development projects, deliveringbasic social services and executing other tasks aimed at amelio-rating the living conditions of citizens within their respectivejurisdictions. Within the framework of the country’s currentdecentralization initiative, the state has devolved special powersand resources to enable the councils discharge their obligations. Intheory, this framework further permits the councils to augmenttheir resource pool from other sources, such as their local residents,civil society organizations, regional and local state or privateinstitutional bodies, as well as international agents of development.However, in practice, councils, especially those based in rural areas,

Major role

Agricultural extension services.Construction & maintenance of rural roads.Responsible for programmes dealing with all women’s welfare.Responsible for safeguarding water & other rural-based resources.Protection of public health.Lead efforts to improve literacy levels among rural children & adults.Responsible for preserving indigenous cultural artifacts and practices, foundmainly in rural areas.Involved in management of forest and related rural resources.

al Involved in rural school-related development, e.g., school supplies, buildingrepairs, contributions towards teachers’ salaries.Involved in efforts to improve rural women’s conditions.Involved in efforts to build and improve the skills of rural residents.Promotion of rural development initiatives.Advocates interests of rural inhabitants.Provides technical & financial support for rural development projects.Provides technical & financial support for rural development projects.

DittoDittoDittoProvide financial & technical support for rural water supply, farm-to-marketroad, and other rural public infrastructure development projects.

A.J. Njoh / Habitat International 35 (2011) 101e110104

have no independent sources of revenue and depend on paltryfunds from the central government to function.

Data sources and methodology

The data for this study were collected during the summers of2008 and 2009. The data collection process involved the use ofa combination of strategies including traditional ethnographictechniques, archival research/content analysis involving the reviewof local newspapers in Cameroon and informal conversations withgovernment authorities in relevant central and sub-nationaladministrative units as well as key members of the selectedcommunities.

The conversations with key government officials were designedspecifically to elicit information on their diverse perspectives withrespect to citizen participation in the planning process and theinevitable interplay amongst these perspectives. The archivalresearch and other efforts to secure secondary data were designedto elicit information on the institutional framework for ruraldevelopment policy administration.

The largely qualitative nature of research on communityparticipation (CP) has resulted in a dearth of indicators in the field.Consequently, researchers and practitioners often resort to devel-oping indicators to serve their specific needs. Following in thistradition, the present research effort developed a set of indicatorsfor use in the present study. The indicators, which are summarizedin Table 2, are derived especially from narratives contained in theofficial reports of Helvetas, the international NGO that played themost instrumental role in the projects discussed here. Some back-ground information on this NGO is in order.

The Swiss Cooperation for International Development (Helve-tas) is a private Swiss development organization, which wasestablished in 1955. It is involved in infrastructure developmentprojects in rural areas, sustainable management of naturalresources, education, culture, and civil society in 22 countries inLatin America, Africa and Asia. Its numerous activities in Cameroon,where it operated from 1962 to 2007, included in-cash assistance to

Table 2Indicators of citizen & stakeholder participation.

Item Participation mode/indicator Rationalization of indicator & i

01. Ordinary sessions The number of ordinary sessiopromoting stakeholder participthis connection.

02. Number of committees The number of committees sugbe involved in the communityto tell us something about the

03. Labour (in-kind) contributions In-kind contributions are depeactually get involved is anothe

04. Meeting attendance Sacrificing time to attend localis the rate of attendance at couWhat is the level of youth atte

05. Commitment to democratic values& inclusiveness.

Citizen participation flourishesHow balanced are the meeting

06. Distributive justice Citizen participation is essentiof labour. How accessible are s

07. Post-implementation participation The viability of especially infraare committed to maintainingPolicy and Strategy? Does it ha

08. Water fees/rates Citizens often expect to pay litHowever, maintenance costs ureasonable?

09. Skill and talent improvement Meaningful CP depends on theinclude training/re-training prexisting skills and learn new o

10. Local economic development andother initiatives

A good indicator of the willingthey, on their own initiate dev

rural communities, technical and financial support for soft projects,such as capacity building, and hard projects such as water supplyand other infrastructure development. During the twilight of itstenure in the country, Helvetas crafted instruction manuals andprovided training on how local communities can maintain andmanage the water supply schemes they had helped to develop. Amajor feature of the manuals and training is their emphasis oncitizen participation as an indispensable element in local infra-structure development, maintenance and management.

Apart from seeking to understand the extent of citizen partici-pation (CP) in rural development projects, the study reported hereis also interested in shedding light on the climate that exists for CPin Cameroon.

The empirical referents for the study include four rural councilsinvolved in self-help local development projects that werecompleted under the auspices of Helvetas. To facilitate CP andensure the functioning of local self-help projects, Helvetas instructsrural councils and communities to adhere to the following guide-lines (Anembom Consultants & Helvetas, 2007):

� Set up a committee in charge of every aspect of the commun-ity’s development (e.g., water, health, social, finance, education,etc.);

� Ensure that the committees and all other local decision forumsreflect the community’s demographic composition in terms ofsex, age, socio-economic status, and tribe.

� Ensure that the committees meet regularly and frequently;� Organize regular training and re-training sessions foremployees;

� Ensure transparency of all official community business;� Operate a bank account;� Have some funds (about 50,000 frs CFA) in the treasurer’skeeping for emergency infrastructure repairs purposes;

� Have a trained, full-time andpaidmaintenance crew (caretakers)for the infrastructure, especially water supply systems; and

� Constitute committees and actively promote citizen involve-ment in the operation and management of local infrastructure.

ndicative questions

ns that a council schedules is a theoretical indication of the council’s interest ination. The number of such sessions held indicates the council’s real interest in

gests in theory that the council and members of the community are willing to’s planning process. The actual number of committees functioning goes furtherreality of this willingness.ndable measures of CP. To express a willingness to be involved is one thing. Tor.council events says a lot about citizens commitment to their community. Whatncil meetings?ndance?in a democratic environment. What is the level of involvement in elections?s in terms of gender composition?al not only in relation to labour input, but also with respect to enjoying the fruitservices resulting from CP initiatives?structure projects such as water supply depends on the extent to which citizensand safeguarding the system. Does the community have a Water Managementve a caretaker for its water system?tle to nothing for services (e.g., water supply) they contributed to realizing.sually dictate the need for fees and rates. What are these fees/rates? Are they

knowledge and skill level of the citizens. Thus, efforts to promote CP mustogrammes. What is the level of involvement of the councils in efforts to upgradenes necessary in the community?ness of citizens to be involved in self-reliant development is the extent to whichelopment projects. How involved are the citizens in this regard?

A.J. Njoh / Habitat International 35 (2011) 101e110 105

Research question, sampling strategyand sampled rural councils

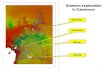

To what extent did the councils adhere to the guidelines stipu-lated by Helvetas for maintaining and managing local infrastruc-ture projects? To respond to this question, the maintenance andmanagement records for the self-help water schemes of four ruralcouncils were examined. The four sampled councils include: Batibo,Belo, Jakiri, and Tubah. After Helvetas, the following guidelineswere adhered to in selecting councils for inclusion in the study(Anembom Consultants & Helvetas, 2007). First, only councils thathad collaborated with Helvetas in the realization of one or morecommunity self-help projects between 2002 and 2006 wereincluded. Second, the selected councils had to be geo-administra-tively distributed in such a manner that no two councils originatedin the same administrative division. Finally, the councils had to bedeliberately heterogeneous in terms of their management capacity.It was not possible to include councils, which reflected the politicallandscape in Cameroon in terms of the political affiliation of theircouncilors. This is because the Northwest Region, the locale of theselected councils (see Fig. 1), is the base of the country’s mainopposition party, the Social Democratic Front (SDF). Consequently,all of the councils examined were dominated by SDF members.

The selected rural councils

The selected rural council areas include Batibo, Belo, Jakiri andTubah (see Fig. 1; Anembom Consultants & Helvetas, 2007). TheBatibo Rural Council, which covers an area of 415.9 km2 andcontains a population of 92,000, is located in Momo Division. BeloRural Council is located in Boyo Division and covers an area of346 km2. It has a population of 80,000. Jakiri Rural Council islocated in Bui Division and encompasses 675 km2.

It contains a population of 70,000. Tubah Rural Council is part ofMezam Division, which is also the locale of the Northwest Regionalcapital, Bamenda. The council has jurisdiction over an area of363 km2 and about 68,700 inhabitants.

Main findings

Table 3 summarizes the intensity of community participation(CP) in the maintenance and management of the water supply

Fig. 1. Sampled councils, N.W. Region.

schemes of the sampled councils. In the specific context of thisstudy, the table shows the extent to which each council adhered tothe guidelines for managing and maintaining local infrastructureprojects in a participatory fashion. The first column of the tablecontains the different CP modes examined in the study. The secondthrough fifth columns contain information on each council’sperformance with respect to each CP mode. The sixth columncontains information on the extent to which each of the 15 CPmodes was employed. The data in this column are standardized bymeans of averaging to enable meaningful comparison of thefrequency with which the different CP modes were employed.

As the table shows, ‘councilor-initiated community develop-ment action,’ which includes local community developmentactivities organized by the council on a ‘as-needed-basis,’ emergedas the most frequently employed mode of CP. The frequency withwhich this mode was employed ranged from a high of 45 times forBelo to a low of 1 for Tubah, for an average of 27.75 during theperiod under examination. The second most popular CP modeemployed by the councils was the organization of training eventsfor councilors and/or members of the local communities. Thespecific number of such events organized ranged from 34 for Tubahto 3 for Batibo and Belo respectively, for an average of 19. Thecouncils were also very likely to promote CP by setting up watermanagement committees. This was the third most popularly usedCP mode. The number of these committees ranged from 0 for Beloto 22 for Batibo, for an average of 10 per council. The leastfrequently employed CP modes were the holding of committeemeetings and the maintenance of paid caretaker staff. Each had anaverage frequency of 1.5. In fact, one council, Belo, held no watercommittee meeting for the entire period under examination. Thatcommittee meetings ranked at the bottom of all modes of inter-actions while the setting up of committees was sold as the mostpromising strategy for promoting CP constitutes a paradoxicalrevelation of this study.

It is surprising that Belo, which had organized the highestnumber of ‘councilor-initiated development activities’ appears atthe bottom of the ladder for ‘water committee meeting.’ Onepossible explanation for this apparent contradictory revelation isthat the development activities organized by the councils includedperforming tasks of the genre typically executed by watercommittees. However, there is no way of knowing with certainty ifthis was indeed the case since interviewees were not required tospecify the type of ‘councilor-initiated development activities’ theyhad organized.

The Batibo Rural Council, comprising 41 members, scheduled 4ordinary sessions but held only 2 in 2006. The Council had 4 councilcommittees, namely Works, Social Affairs, Finance and NaturalResources. However, only one of them, the Social Affairs Committeemet once in 2006. The Works Committee, which is supposed to beactively involved in every public works project, neither met norworked on the three water supply projects that were completedthat year. Another citizen-based group operating in the BatiboCouncil Area is the local economic development pole. This entityheld 8 meetings and one joint evaluation session in 2006. Thecouncil effectively utilized the Water Resource Management Policyand Strategy (WRMPS). In this regard, the council scheduled andheld 4 water-related meetings. In addition, all the communitieswithin the council area, including those whose water supplyprojects were yet to be realized, organized a few water forums.

The 35-member Belo Rural Council held two ordinary sessionsin 2006. AWater Management Committee (WMC) was elected intooffice in Belo in February 2006. The council’s internal rules andregulations (IRR) provided for 6 meetings per year. Although theWMC was elected two months into the year, it did well to hold allthe 6 meetings required by the IRR before the end of 2006.

Table 3Community & stakeholder participation for the four councils.

CP Indicator Participation activity by rural council area Average

Batibo Belo Jakiri Tubah

Council sessions 2 2 3 3 2.5Council committees 4 4 5 5 4.5Functioning committees 1 4 5 2 3.75Council committee meetings (2005e2006) 1 1 5 2 3.75Training events 3 15 24 34 19Training for councilors 0 6 13 6 5.25Training for staff 0 6 1 6 2.75Training, communities 3 3 10 34 8Community dev. action initiated by councilors 38 41 35 1 27.75Number of council-organized water forum meetings held. 4 0 1 1 1.5Number of councils with Water Management Committee 22 0 13 5 10Number of communities with internal rules & regulations 3 1 6 4 3.5Number of Water Mgt Committees with bank account. 1 1 1 4 1.75Trained caretakers 3 5 1 2 2.75Paid caretakers 1 2 1 2 1.5

Source: Anembom Consultants and Helvetas (2007: p. 28).

A.J. Njoh / Habitat International 35 (2011) 101e110106

The Jakiri Rural Council completed four self-help waterprojects in the villages of Mantum, Yer, Sop and Nkar. In 2006, thecouncil, which has 35 members, held 3 council sessions, operatedfive committees, namely Health/Social Affairs, Works and Infra-structure, Finance, Education, and Natural Resources. The SopWater Scheme developed its internal rules and regulations (IRR)in June 2006, organized one election, and held several meetingsabove the required minimum before the end of that year. Thewater scheme now has 241 public stand taps up from the 64 it hadprior to 2005. Inhabitants of the village pay 1000 frs CFA foraccess to the public stand pipe, while private home connectionscost 20,000 frs each.

In 2006, the Tubah Rural Council had 35members, and operatedfive council committees, namely Finance, Welfare, Works, NaturalResources and Contracts. However, only two of these committees,the Finance andWelfare, function on a regular basis. Only these twocommittees held council committee meetings in 2006. On its part,the council organized 34 training sessions for members of thecouncil, and the community at large. One of the villages within theTubah Rural Council area, Bambui, has a successful self-help watersupply scheme. The scheme operates a functional Water Manage-ment Committee (WMC) that meets once a month. There are twotrained and paid caretakers in charge of the community’s watersystem.

A major revelation of this study is that citizen or communityparticipation (CP) assumes several forms, ranging from in-cashcontributions towards implementing public infrastructure facili-ties, to direct involvement in the management and maintenance ofthe projects. This latter is suggested by the meetings that broughttogether local government council officials and members of thelocal communities in which the councils operated. Another majorrevelation is that more intense modes of CP such as organizingtraining sessions and setting up infrastructure maintenancecommittees emerged as some of the most frequently employed.This contradicts charges by critics to the effect that only less intensemodes of CP are likely to be employed in practice. One criticconcedes that NGOs register more positive results when theirleaders build close personal relationships with members of thecommunities in which they operate (Hailey, 2001). Along similarlines, it is arguable that the frequent meetings observed in thisstudy plausibly succeeded in nurturing fruitful relationshipsbetween local government officials and members of their hostcommunities. Statements by members of some of these commu-nities lend credence to this assertion. One resident of the TubahRural Council area, for instance, stated as follows.

“We and the councilors are one. The councilors are not like thepeople from Bamenda or Yaounde who do not live here and do notknow us and our problems” (Author’s field notes).

It is easy to glean the general apprehension and mistrust ofbureaucrats from the regional headquarters (e.g. Bamenda) andnational capital (Yaounde in this case) on the part of local elements.

Analysis and discussion

External institutional bodies, particularly the state, local andinternational non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are alwaysinvolved in self-help development projects in developing countries.As Table 1 suggests, at least five international NGOs are, or have atsome point been, involved in such initiatives in rural Cameroon.However, very little is known about the role of these internationalbodies besides the fact that they contribute financially to therealization of self-help initiatives. As the activities of Helvetas in therural council areas discussed here demonstrate, international NGOsdo a lot more than contribute financially towards these initiatives.In fact, the appellation, ‘self-help,’ tends to distort the picture ofwhat actually happens in infrastructure and other projects witha high citizen participation (CP) component.

In ancient times, activities such as hunting large game, fellinga tree to serve as a bridge across a river, building sheds in a villagemarket, and so on, which required citizen participation, wererelatively less complicated. This is hardly the case today.Contemporary self-help projects include, but are not limited to,constructing potable water supply systems, constructing farm-to-market roads, building and equipping modern health clinics ordeveloping electrification systems. Projects such as these requiretechnical expertise and sophisticated logistical knowledge that isoften locally unavailable especially in rural communes. Thisaccentuates the need for international NGOs and governmentrural councils.

As shown in the study reported here, international NGOs such asHelvetas possess the resources, particularly the administrativeknowledge necessary for developing, implementing, monitoringand maintaining self-help infrastructure projects. As the studyrevealed, Helvetas developed highly valuable manuals intended tohelp rural councils and communities manage, monitor and main-tain their water supply systems. The study also underscored theindispensable role of government rural councils as coordinators oflocal infrastructure development, management and maintenanceactivities.

A.J. Njoh / Habitat International 35 (2011) 101e110 107

As Table 3 shows, some councils did a better job than others inpromoting citizen participation (CP). In general, the councils hada mixed record on this score. What factors account for the poor CPrecord of some councils? The remainder of this paper is dedicatedto addressing this question. In particular, it identifies a number offactors that are believed to have accounted for the poor perfor-mance of the councils on different measures of CP. Following inthe footsteps of Botes and Van Rensburg (2000) and Njoh (2002),the factors are categorized as either external or internal withrespect to the target councils and communities under theirjurisdiction. The external factors are deemed to include thefollowing:

� lack of political support,� colonial legacy of excluding women from the public sphere,� paternalistic orientation of national authorities, and� negative trends in the national and global economy.

Lack of political support

The Cameroonian government has customarily promoted ruraldevelopment. In fact, rural development was emphasized by thecountry’s pioneer president Ahmadou Ahidjo, and for abouta decade by his successor beginning in 1982. This emphasis waspart of the leadership’s effort to promote regional equilibrium indevelopment. However, this emphasis was terminated in the1990s when the leadership succumbed to international pressuresand reluctantly agreed to initiate political reforms that haveincluded authorizing the existence of multiple political parties inthe country. Since then, regions and rural councils in areas thatare not controlled by the ruling party, the Cameroon People’sDemocratic Movement (CPDM) have been neglected. Asmentioned above, all of the councils examined here are under thecontrol of the Social Democratic Front (SDF). The SDF is not onlyan opposition party but the ruling CPDM’s nemesis. Neglectingcouncils and areas under the control of opposition parties hastranslated into under-funding and denying these areas the benefitof essential resources such as competent employees from thecentral government. Consequently, even councils with the will todo so often lack the resources necessary to promote communityparticipation.

Fig. 2. A community planning session. Notice the underrepresentation of w

Colonial legacy of excluding women from the public sphere

Women were terribly underrepresented in the affairs of thecouncils under examination here. Evidence of this can be found onthe membership rosters for council committees, and photographstaken at various events of some of the councils (see Figs. 2e4). Onewoman, a leader of a prominent women’s organization in Batibooffered the following response when asked why she was nota member of one the water or other project committees. Speakingin pidgin English, she said (Author’s field notes):

Me I know book? No bi na so so book peupil dem flop for datcommuti dem?Me I no sabi book for seka say ma papa be wan say Igo marret.

The foregoing statement contains two rhetorical questions: “am Iliterate? Aren’t the committees comprised exclusively of literatepeople?” Thewomanwent on to add that she hadno chance of goingto school because her father wanted her to get married (which shedid). The woman’s insightful response speaks to a larger issue thatcannot be ignored in any meaningful discourse of CP in particularand development planning in general. The issue has to do with thehigher levels of illiteracy among women vis-à-vis men throughoutAfrica. In Cameroon, this problem is rooted in colonial developmentpolicies that overtly discriminated against females. Prior to theEuropean conquest, African women, just like their male counter-parts, were active in both the public and domestic spheres. Duringthe colonial era, Europeans succeeded in spreading the Westernnotions of domesticity, thereby effectively confining Cameroonianwomen to the private space of the home. Oneway bywhich colonialauthorities articulated the Western notions of domesticity inCameroon was by creating institutions of formal education exclu-sively for boys. For instance, in the Anglophone portion of thecountry, the first secondary schools, St. Joseph’s College Sasse, Buea,Cameroon Protestant College, Ombe, Bali, and Government TradeCentre (now, Technical High School), which were established in1938, 1948, and 1952, respectively enrolled only boys.

Paternalistic orientation, and negative perception,of national authorities

National authorities in the context of this discussion includecentral government officials attached to the ministerial bodies

omen. Source: Stucki and Ischer (Online): www.helvetascameroon.org.

Fig. 3. Photo op. following a community planning meeting. Again, no women. Source: Stucki and Ischer (Online): www.helvetascameroon.org.

A.J. Njoh / Habitat International 35 (2011) 101e110108

involved in rural development. Conversations with these authori-ties reinforced the popular belief that they generally considerregional units of national institutional bodies and members of thecommunities under their charge as inept. Further credence to thisbelief can be easily gleaned from reports in the national press andother media regarding the relationship between national authori-ties and provincial or peripheral entities in the country. Thefollowing statement, which the government national daily,Cameroon Tribune once attributed to a high-ranking official of theMinistry of Territorial Administration, the ministerial body underwhose jurisdiction rural government councils fall (see above), isillustrative.

Even though Cameroon has adopted decentralisation, thegovernment can only “share power with autonomous or semi-autonomous sub-systems that are competent to exercise thepowers that are conferred on them” (Cameroon Tribune, 2003,para. 2).

Apart from generally believing that provincial or regional unitsare incompetent, central authorities in Cameroon are well knownfor their tendency to issue policy directives without regard for localrealities. This is one of the problems that have preoccupied inter-national NGOs such as Helvetas. A recent study revealed that rural

Fig. 4. Attendants at a high-level urban planning meeting. Notice the absence o

dwellers in the council areas under examination here harboura negative view of these authorities (Stucki, 2006). In particular,rural residents are perturbed by the possibility of central and otherexternal entities appropriating locally-realized infrastructureprojects such as water supply systems. Their fears are not baselessas there have been cases in which the national state has used everymeans necessary, including military force, to appropriate suchprojects. The case of the Kumbo Water project, which is located inthe general area of the councils examined here, is illustrative(see Njoh, 2006; Page, 2005). This tendency for appropriating localprojects on the part of the Cameroonian government serves todiscourage rural dwellers from fully participating in self-helpdevelopment projects. This is especially so when efforts to realizethese projects are coordinated by rural government councils, whichare units of the national government.

A related problem has to dowith the feeling of powerlessness onthe part of local government councils throughout the country. Localgovernment authorities have never spared an opportunity toexpress this feeling to the national leadership since decentraliza-tion initiatives were re-introduced in the country in the 1990s. Forinstance, at the end of a workshop that was held in Bamenda(March 30eApril 3, 2003) and drew participants from urban andrural councils in the Northwest and Southwest Regions, the

f women. Source: Stucki and Ischer (Online): www.helvetascameroon.org.

A.J. Njoh / Habitat International 35 (2011) 101e110 109

participants underscored the need for powerful local governmentcouncils. As reported in Cameroon Tribune of April 3, 2003, thecouncilors seized the opportunity offered by the workshop torequest the national government to devolve more authority to theurban and rural councils (Cameroon Tribune, 2003).

Negative trends in the national and global economy

The Cameroonian economy has been experiencing negativetrends since the 1990s. During the last couple of years, this situationhas been aggravated by the ongoing global economic crisis. Ruralareas have suffered the most from these economic problems asrural products, especially agricultural commodities are no longerable to fetch enough money to enable rural residents meet therising cost of basic needs. Consequently, rural residents have had tospend larger amounts of time toiling. This effectively leaves themwith very little or no time to allot to activities such as attendingcouncil committee meetings and/or participating in self-helpproject development.

It is in order to now turn to impediments to CP located withinthe target councils or communities under their jurisdiction. Thesefactors include the following:

� scarcity of skilled personnel,� financial difficulties,� the elitist orientation of the formally educated class, and� questionable nature of self-help development projects.

Scarcity of skilled personnel

As Table 3 shows, the number of trained caretakers ranged fromonly 1 for Jakiri to 5 for Belo, for an average of almost 3 suchpersonnel per council area. To appreciate the importance of skilledcaretakers for projects such as water supply systems, one must firstacknowledge frequent technical glitches as a major characteristic ofsuch systems. Belo, which has the highest number of caretakers, forinstance, suffers water shortages for an average period of threemonths a year (Anembom Consultants & Helvetas, 2007, 2007:p. 17). Therefore, such systems need more, not less, trained care-takers. However, skilled personnel such as plumbers who can serveas caretakers for water supply systems are rare or completelyabsent in most rural areas in Cameroon. The guidelines for post-project implementation management issued by Helvetas suggestthat to be functional, a community should have at least 2 caretakersfor its water system. Thus, the communities under examinationhere suffer from a dire shortage of trained personnel serving ascaretakers. One reason for this is that the skilled technicians aredrawn to urban centres, which, in contrast to rural areas, offer thembetter opportunities for socio-economic advancement.

Financial difficulties

Rural communities in Cameroon, as in other developing coun-tries, are by definition, impoverished. This problem is compoundedby the fact that Cameroonian rural councils have few, if any inde-pendent sources of revenue and receive very little financial supportfrom central authorities. This is especially true for councils underthe control of members of the ruling regime’s opposition parties(see above). The council’s and local communities’ impoverishedstate accounts, at least partially, for the fact that fewer than half ofall the councils’ caretakers are serving in a paid capacity (see Table3). As unpaid workers, these caretakers are unlikely to bemotivatedto execute their assigned tasks.

Elitist orientation of the formally educated class

Illiteracy levels tend to be higher in rural than in urban areasthroughout Cameroon. At the same time, the literacy culture, withits propensity for formality entailing the written documentation ofall transactions and activities relating to local development hasusurped traditional documentation alternatives. Concomitant withthis has been a tendency to implicitly make functional literacya precondition for effective participation in the local developmentdecision-making process. This tendency is attested to by the rapidsupplanting of native languages by English and French as the mediaof communication in all discussions relating to local developmentthroughout Cameroon. Resulting from this has been the effectiveexclusion of the majoritydthe functionally illiteratedfrom thelocal decision-making process. Recall that the woman in Batibo(quoted above) gave her illiteracy status as the reason why shecould not participate in council-organized development projectcommittees.

Doubtful nature of self-help projects

Rural dwellers generally harbour doubts about the exact natureof so-called self-help infrastructure development projects. Theperturbing question in the mind of most rural dwellers inCameroon is, ‘who owns self-help projects once they arecompleted?’ Citizens generally see the government and otherpowerful societal entities as the owners of such projects. They pointto the fact that they are charged water rates, for instance, as proofthat self-help water projects belong to the state or other powerfulsocietal entities and not to citizens. A recent study dedicated totackling the local infrastructure ownership question found that theresponse varies markedly from one stakeholder to another (Stucki,2006). As mentioned above, instances in which the national statehas attempted to forcefully assume control over water projectsrealized through self-help initiatives are not uncommon in thecountry. Consequently, local communities tend to view withskepticism any call to contribute towards the realization of self-help projects. Most tend to believe that eventually, the centralgovernment would find a reason to confiscate, own and operatesuch projects. This belief leads members of local communities tooffer passive resistance and withhold active support to suchprojects.

Recommendations and concluding remarks

Self-help projects, their name notwithstanding, do not andcannot ‘just happen.’ Some entity needs to initiate and coordinatetheir implementation. The increasing exodus of rural dwellers has,among other things, compounded the problem of creating well-staffed institutions to coordinate self-help development efforts inrural locales in developing countries such as Cameroon. The ruralcouncils present themselves as the only institutions viable enoughto handle this task. As units of the central government, councils arestable enough to guarantee the continuity necessary for imple-menting and ensuring the sustainability of self-help rural infra-structure projects. It is unrealistic, and in fact foolhardy, to expectindividuals who have migrated in search of greener pastures inurban areas throughout the country or abroad to return to managethese projects.

However, rural councils are unlikely to succeed in the role beingproposed herewhile they continue to be viewedwith skepticism byrural inhabitants. Therefore, central authorities will dowell to grantmore autonomy to, and empower, these councils. Such empower-ment should entail the provision of additional funds from thenational budget, and the authority for rural municipalities to

A.J. Njoh / Habitat International 35 (2011) 101e110110

generate and control their own revenues. Doing so will go a goodway in providing the funds required for hiring the caliber of skilledpersonnel necessary to coordinate the implementation, manage-ment and maintenance of local infrastructure projects.

The need to promote the active participation of rural dwellers inthe development process dictates a serious revamping of standardoperating procedures. First, local and other authorities interactingwith rural communities must make a conscious effort to commu-nicate in the indigenous languages of members of these commu-nities. Alternatively, they can employ the regional lingua franca. Ina good many parts of Cameroon, this will be Pidgin English. Doingso will dispel the sense of alienation felt by those not proficient ineither English or French, thereby encouraging their indispensableparticipation in the development decision-making process. Second,authorities must actively seek to promote the participation ofwomen in this process as well. Women constitute more than 52% ofthe Cameroonian population. However, one could never deducethis from their proportion in key decision-making forums. Finally,the national government must seek to clarify the meaning of self-help projects to rural and other communities involved in theimplementation of such projects. Given previous, albeit failed,attempts on the part of the government to appropriate suchprojects, the national government will do well to issue and publi-cize a statement assuring the public that it has no intention ofappropriating self-help schemes.

The study discussed in this paper has highlighted the impor-tance of rural councils as coordinating authorities in self-helpdevelopment initiatives. The study is premised on a belief in citizenparticipation (CP) as a viable cost-saving strategy in the develop-ment process in resource-scarce settings. The prowess of CP iswidely acknowledged in the development literature. However,there is a dearth of knowledge on how to go about promoting CP.This study contributes to efforts to reverse this situation by high-lighting the activities of major institutional actors involved in CPinitiatives in Cameroon. The discussion holds important lessons forefforts to promote citizen participation in the rural developmentprocess not only in other parts of Cameroon but the world ingeneral.

References

Anembom Consultants, & Helvetas. (2007). What is Helvetas leaving behind inCameroon: A tool for monitoring sustainability of Helvetas interventions in 4councils in the NW Province, Batibo, Belo, Jakiri, Tubah. Bamenda, Cameroon:Helvetas-Cameroon.

Binns, T., & Nel, E. (1999). Beyond the development impasse: the role of localeconomic development and community self-reliance in South Africa. TheJournal of Modern African Studies, 37(3), 389e408.

Botes, L., & Van Rensburg, D. (2000). Community participation in development:nine plagues and twelve commandments. Community Development Journal, 35,41e58.

Cameroon Tribune. (April 3, 2003). Northwest: councilors ask for greater decen-tralization. Cameroon Tribune. Available online. http://www.cameroontribune.cm/article.php?lang¼Fr&oled¼j22092009&idart¼7249&olarch¼j07042003.

Chambers, R. (1995). Poverty and livelihoods: whose reality counts? Urbanizationand Development, 7(1), 173e204.

Chambers, R. (1997). Whose reality counts?: Putting the first last. London: Interme-diate Technology Publications.

Cooke, B., & Kothari, U. (Eds.). (2001a). Participation: The new tyranny? London/NewYork: Zed Books.

Cooke, B., & Kothari, U. (2001b). The case of participation as tyranny. In B. Cooke, &U. Kothari (Eds.), Participation: The new tyranny? (pp. 1e15). London/New York:Zed Books.

Hailey, J. (2001). Beyond the formulaic: processes and practice in South Asian NGOs.In B. Cooke, & U. Kothari (Eds.), Participation: The new tyranny? (pp. 88e101).London/New York: Zed Books.

Hickey, S., & Mohan, G. (Eds.). (2004). Participation, from tyranny to transformation?:Exploring new approaches to participation in development. London/New York:Zed Books.

Ischer, M., Tamini, J., Asanga, C., & Sylla, I. (2007). Cameroon: Strategic planning andmonitoring of municipal development. Bamako, Mali: Communicances.

Kamete, A. Y. (2006). Participatory farce: youth and the making of urbanplaces in Zimbabwe. International Development Planning Review, 28(3),359e380.

Khapoya, V. (1998). The African experience: An introduction (2nd ed.). Upper SaddleRiver, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Kwo, M. (1984). Community education and community development in Cameroon:the British colonial experience, 1922-1961. Community Development Journal, 19(4), 204e213.

Kwo, M. (1986). Community education and community development: Anglophonecameroon experience since 1961. Community Development Journal, 21, 161e168.

Lucas, J. R. (1956). Democracy and participation. Harmondsworth: Penguin.Madu, E. N., & Umebali, E. (1993). Self-help approach to rural transformation in

Nigeria. Community Development Journal, 28, 141e153.Midgley, J. (1986). Community participation, social development and the state. Lon-

don/New York: Methuen.Ndongko, W. A. (1974). Regional economic planning in Cameroon. Research Report

No. 21. The Scandinavian Institute of African Studies, Upsala.Njoh, A. J. (2002). Barriers to community participation: lessons from the mutengene

(Cameroon) self-help water supply project. Community Development Journal, 37,233e248.

Njoh, A. J. (2003). The role of community participation in public works projects inLDCs: the case of the Bonadikombo, Limbe (Cameroon) self-help water supplyproject. International Development Review, 25, 85e103.

Njoh, A. J. (2006). Determinants of success in community self-help projects: thecase of the Kumbo water supply scheme in Cameroon. International Develop-ment Planning Review, 28(3), 381e406.

Nye, J., Jr. (1963). Tanganyinka's self-help. Transition, 11, 35e39.Page, B. (2005). Communities as the agents of commodification: the Kumbo water

authority in Northwest Cameroon. Geoforum, 34, 483e498.Pennock, J. R. (1879). Democratic political theory. Princeton: Princeton University

Press.Schumpeter, J. (1942). Capitalism, socialism and democracy. London: Allen & Unwin.Smith, B. C. (1992). Participation without power: Subterfuge or development.?

Community Development Journal, 33, 197e204.Stucki, U. (2006). Local ownership. Bamenda, Cameroon: Swiss Association for

Technical Cooperation (Helvetas). Available online. http://www.helvetascameroon.org.

Sutton, K. (n.d.). (On-line). Local citizen participation: case study of a CommunityDevelopment Board. Unpublished paper available on the Internet at: http://naspaa.org/initiatives/paa/pdf/Karen_Sutton.pdf.

Wiles, P. (1969). A syndrome, not a doctrine. In G. Ionescu, & E. Gellner (Eds.),Populism: its meaning and national characteristics. New York: Macmillan.

Yiftachel, O., & Huxley, M. (2000). Debating dominance and relevance: notes on the‘communicative turn’ in theory. International Journal of Urban and RegionalResearch, 24, 907e913.

Related Documents