Historical Dictionary of Moldova Historical Dictionary of Moldova Second Edition Series: Historical Dictionaries of Europe #52 Andrei Brezianu and Vlad Spânu (click to enlarge) The Scarecrow Press, Inc. Buy at Amazon List Price: $95.00 ISBN: 0-8108-5607-7 ISBN-13: 978-0-8108-5607-3 Pub Date: Apr 2007 496 pages Binding: Cloth The A to Z of Moldova Series: The A to Z Guide Series #232 Andrei Brezianu and Vlad Spânu The Scarecrow Press, Inc. List Price: $29.95 Buy at Amazon ISBN: 0-8108-7211-0 ISBN-13: 978-0-8108-7211-0 Pub Date: May 2010 498 pages Binding: Paper The Republic of Moldova claims a European lineage reaching back in time long before its 14th century accession to statehood. In the 15th century, it managed against all odds to avoid being conquered by Islam and—albeit an

moldova

Oct 31, 2014

dictionary

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

Historical Dictionary of MoldovaHistorical Second Series: Andrei (click The Buy List ISBN: ISBN-13: Pub 496 Binding: Date: Apr Price: Scarecrow Historical Brezianu to Press, Dictionaries and of Europe Vlad Dictionary of Moldova Edition #52 Spnu enlarge) Inc. at Amazon $95.00 0-8108-5607-7 978-0-8108-5607-3 2007 pages Cloth

The Series: Andrei The List Buy ISBN: ISBN-13: Pub 498 Binding: Date:

A The A

to to Z

Z Guide

of Series Vlad Press,

Moldova #232 Spnu Inc. $29.95 at Amazon 0-8108-7211-0

Brezianu Scarecrow

and

Price:

978-0-8108-7211-0 May 2010 pages Paper

The Republic of Moldova claims a European lineage reaching back in time long before its 14th century accession to statehood. In the 15th century, it managed against all odds to avoid being conquered by Islam andalbeit an intermittent vassal after 1485it maintained its autonomy and was never turned into a province of the Ottoman Empire. After this period, however, Moldova would not be so fortunate, as it altered between Russian, Romanian, and Soviet control until it finally gained its independence in 1991 from the Soviet Union.

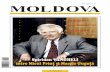

The second edition of the Historical Dictionary of Moldova, through its chronology, introduction, appendixes, maps, bibliography, and over 600 cross-referenced dictionary entries on important persons, places, events, and institutions and significant political, economic, social, and cultural aspects, traces the history of this small, but densely populated About country, providing a compass the for the direction it is heading. Authors

Andrei Brezianu is a specialist in European intellectual history and has taught at the Free University of Moldova, the Catholic University of America, and the University of Bucharest. Vlad Spnu is the president of the Moldova Foundation in Washington, DC. He served as a senior Moldovan diplomat both in Chisinau and abroad between 1992 and 2001. Read Table Editor's Preface Acknowledgments Reader's Acronyms Maps Chronology Introduction THE Appendix Appendix A: DICTIONARY Chairpersons B: of Presidents over 600 Moldova's Legislative of entries Bodies Moldova and Note Abbreviations a related of article by Jon for Woronoff, Historical by Scarecrow Press' of Series Editor

Contents Foreword

Dictionary Jon

Moldova: Woronoff

Appendix Bibliography About the Authors

C:

Prime

Ministers

of

Moldova

Preface

Introduction Entries

Entries

Entries

The Scarecrow Press, Inc. All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission Reviews: Newly Released Book: Historical Dictionary of Moldova. By Jon Woronoff, Scarecrow Press' Series Editor (USA) of the publisher.

A New Historical Dictionary of Moldova. By Paul E. Michelson, Huntington University (USA) The Historical Dictionary of Moldova - an exceptionally useful book. By John Todd Stewart, American Ambassador to Moldova from 1995 to 1998

From Abaclia to Zubcu-Codreanu. By Alex van Oss, Foreign Service Institute (USA)

http://foundation.moldova.org/pages/eng/137/

Movement for the unification of Romania and MoldovaFrom Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Left image: A potential union of Romania and Moldova, including Transnistria, as demanded by the unionists. Right image: A potential union excluding Transnistria, also called the "Belkovsky plan".

A movement for the reunification of Romaniaand Moldova (Romanian: Unirea Republicii Moldova cu Romnia) began in both countries after the Romanian Revolution of 1989 and the beginning of glasnost policy in the Soviet Union. The question of reunification is recurrent in the public sphere of the two countries, often as a speculation, both as a goal and a danger. Individuals who advocate the unification are usually called "unionists" (unioniti). Some support it as a peaceful process based on consent in the two countries, others in the name of a "Romanian historical right over Bessarabia". The supporters of the union refer to the opponents as "Moldovenists" (moldoveniti).Contents[hide]

1 Background

o o

1.1 Revival of nationalism (19881992) 1.2 Political ties and unionism

2 Political commentary 3 Current trends

o o o o

3.1 Dual citizenship for Moldovan citizens 3.2 Action 2012 3.3 The Union Council 3.4 Union Marches

4 Opinion polls

o o

4.1 Moldova 4.2 Romania

5 See also 6 Notes 7 References 8 External links

[edit]BackgroundSee also: History of Moldova and Union of Bessarabia with Romania Bessarabia had been part of the Principality of Moldavia until it was annexed by the Russian Empire in 1812. During the Russian Revolution of 1917, a newly formed Parliament (Sfatul rii) declared Bessarabia's autonomy inside a Russian state. In 1918, after the Romanian army entered Bessarabia, the makeshift parliament decided on independence, only to review its position and ultimately decide on a conditional union with Romania. The conditions, including the provisions for autonomy, were ultimately dropped.[1] In 1940, during World War II, Romania agreed to an ultimatum and ceded the region to the Soviet Union, which organized it into theMoldavian SSR. The Soviets strongly promoted the Moldovan ethnic identity, against other opinions that viewed all speakers of theRomanian language as part of a single ethnic group, taking advantage of the incomplete integration of Bessarabia into the interwar Romania. [2] The official Soviet policy also stated that Romanian and Moldovan were two different languages and, to emphasize this distinction, Moldovan had to be written in a new Cyrillic alphabet (the Moldovan alphabet) based on the reformed Russian Cyrillic, rather than the obsolete Romanian Cyrillic that ceased to be used in the 19th century in the Old Kingdom and 1917 in Bessarabia.[3]

[edit]Revival

of nationalism (19881992)

In September 1989, with the liberalization in the Soviet Union, the Moldovan SSR Parliament declared Moldovan as the official language, and also asserted the existence of a "Moldovan-Romanian linguistic identity".[4] On 6 May 1990, after several decades of strict separation, Romania and the Moldovan SSR lifted temporarily border crossing restrictions, and thousands of people crossed the Prut River which marked their common border.[5] The factors hindering the unification were complex, ranging from the caution of political leaders in Moldova and Romania, the war in Transnistria, and, perhaps more importantly, the mentality of large parts of the population in Moldova (and to some extent in Romania) who were indifferent or opposed to such a project.[6] In his address to the Romanian parliament, in February 1991, Mircea Snegur, the Moldovan president, spoke of a common identity of Moldovans and Romanians, referring to the "Romanians of both sides of the Prut River".[7] In June 1991, Snegur talked about Moldova moving toward the reunification with Romania, adding that the USSR is not making great efforts to stop it.[8]

While many Moldovan intellectuals supported the union and wanted a "reunion with the Romanian motherland",[9] there was little popular support for it, with more than 70% of the Moldovans opposing it, according to a 1992 poll. At the same time, Transnistria, the eastern part of Moldova, inhabited by a Slavic majority, used the putative danger of unification with Romania as a pretext for its own aspirations for independence.[10]

[edit]Political

ties and unionism

Following the declaration of independence on 27 August 1991, the Romanian flag defaced with the Moldovan coat of arms and the Romanian anthem "Deteapt-te, romne!" became the symbols of the new independent Moldova.[11] Following the growing tension between the pro-union governing Moldovan Popular Front and president Snegur, in particular over unification,[12] the president moved closer to the Moldovanist group of Agrarians, and appointed their candidate Andrei Sangheli as prime minister. As a result, and especially after the victory of Agrarians in the 1994 elections, Moldova began distancing itself from Romania. The state flag was slightly modified, and the anthem changed to "Limba noastr". The Moldovan referendum of 1994 for an independent Moldova was seen by many public figures to be aimed at implicitly excluding a union with Romania. Furthermore, the constitution adopted in 1994 by the new Parliament dominated by Moldovanist Agrarians and Socialists called the official language "Moldovan", as opposed to the earlier Declaration of independence that called it "Romanian". The attempt by Moldovan president Mircea Snegur in 1996 to change the name of the official language to "Romanian" was dismissed by the Moldovan Parliament as "promoting Romanian expansionism". A "Concept on National Policy" was adopted in 2003 by the Communist dominated Parliament, stating that Moldovans and Romanians are different peoples, and that the latter are an ethnic minority in Moldova. [13]

Opposition demonstration in Chiinu in January 2002. The text on the inscription reads "Romanian people-Romanian language."

Before 2005, only the Christian-Democratic People's Party, one of the political heirs of the Moldovan Popular Front, actively supported unification. However, the stance of the Christian-Democrats changed significantly after they started collaborating closely with the ruling Moldovan Communists. During the elections of April 2009, the alliance of National Liberal Party (Partidul Naional Liberal) and the 'European

Action' Movement (Miscarea Actiunea Europeana) ran on a common platform of a loose union with Romania, but accumulated only around 1% of the votes.[14]

[edit]Political

commentary

In 2004 and later, the Romanian newspaper Ziua published a series of articles and interviews with Stanislav Belkovsky, an influential political commentator from the Russian Federation, who proposed a plan of a unification between Romanian and Moldova excluding Transnistria. Speculations followed whether his plan is backed by higher circles in the Kremlin, but they were never confirmed. Nevertheless, several journalists and scholars dismissed the plan as a diversion, also pointing out several ambiguities, such as the status of the city of Tighina situated on the right bank of Dniester but under Transnistrian control, and, more importantly, the unlikelihood of Moldova's acquiescence to such a plan. In January 2006, the Romanian president Traian Bsescu declared that he strongly supported the Moldovan bid for joining the European Union and that "the minimal policy of Romania is for the unification of the Romanian nation to take place within the EU". The phrase"minimal policy" led to questions whether there is also a maximal policy. In July 2006, the Romanian president Traian Bsescu, claimed to have made a proposal to the Moldovan president Vladimir Voronin that "Moldova join the EU together with Romania in 2007" and that the alleged offer was rejected. Bsescu also added that Romania would respect this decision and would help Moldova to join EU on its own.[15] In October 2006 the Romanian newspaper Cotidianul estimated the cost of a union with Moldova at 30-35 billion euro,[16] and attracted criticism from the Romanian newspaper Ziua,[17] as well as "Timpul"[18] for exaggerating the costs and disregarding other dimensions of a possible union. After Moldovan parliamentary election of April 2009, the 2009 Moldova civil unrest, the Moldovan parliamentary election of July 2009, and the creation of the governing Alliance for European Integration, a new wave of speculations about the union followed. The Party of Communists, now in opposition, claimed that "the unionists came to power".[19] In November 2009, political commentator Stanislav Belkovsky declared in an interview with Radio Free Europe that April 2009 marks the beginning of the process of Moldova's return to Romania.[20] Traian Bsescu made a state visit to Moldova along with a number of ministers to announce several projects that would intensify ties between the two countries, and the offer of 100 million euro grant for infrastructure projects. Bsescu called Moldova his "soul project".[21] Private Romanian investments are also expected to increase significantly, with the opening of a Moldovan-Romanian business and investment office,[22] and the takeover of the online news portal Unimedia by Romanian group Realitatea-Caavencu group, owned by businessman Sorin Ovidiu Vntu.[23] On February 15, 2010, the Rdui-Lipcani border crossing between Romania and Moldova opened[24] and the remnant Soviet barbed wire fence on the Moldovan side of the border with Romania was dismantled.[25]

In January 2010, Mircea Druc, the former prime minister of Moldova between 1990 and 1991, declared that the unification of Romania and the Republic of Moldova is inevitable.[26] However, acting President Mihai Ghimpu denied in an interview with the Russian language newspaper "Komsomolskaya Pravda v Moldove" that such a move will be taken, stating that a union is not included in the program of the governing coalition.[27] On another occasion he declared that if the people wanted unification, neither he, nor anyone else could stop them.[28] He admitted on several occasions to personally share unionist views.[29] However in August 2010 he declared that the proposition of an "inter-state union" between Romania and Moldova was "a very stupid" idea.[30]

[edit]Current [edit]Dual

trends

citizenship for Moldovan citizens

Between 1991 and 2009, some 140,000 Moldovan citizens obtained Romanian citizenship.[31] According to some estimates, as many as 1 million Moldovan citizens requested Romanian citizenship by 2009.[32] In 2010, the Romanian government created the National Authority for Citizenship to process the large number of applications for Romanian citizenship coming especially from Moldovan citizens. The study "Reacquiring Romanian citizenship: historical, comparative and applied perspectives", released in 2012, estimated that 226,507 Moldovan citizens reacquired Romanian citizenship by August 15, 2011 [33][34] Between August 15, 2011 and October 15, 2012 an additional 90,000[35] reacquired Romanian citizenship, acording to the National Authority for Citizenship, bringing the total to 320,000. A poll conducted by IPP Chisinau in November 2007 shows that 33.6% of the Moldovan population is interested in holding Romanian citizenship, while 58.8% is not interested. The main reason of those interested is: feeling Romanian (31.9%), the possibility of traveling to Romania (48.9%), and the possibility of traveling and/or working in the EU (17.2%).[36]

[edit]Action

2012

In April 2011, a coalition of NGOs from Romania and Moldova created the civic platform "Aciunea 2012" (English: Action 2012), whose aim is to "raise awareness of the necessity of the unification between Romania and the Republic of Moldova". Year 2012 was chosen as a reference to the bicentennial commemoration of the 1812 division of historical Moldavia, when the Russian Empire annexed what would later be called Bessarabia. The proponents see the unification as a reversal of this historical division, a reversal inspired by the rather short-lived Union of Bessarabia with Romania (19181940) disrupted by the Soviet occupation.[37][38][39][40]

[edit]The

Union Council

In February 2012, the Union Council was created to "gather all unionists" in order to "promote the idea of Romanian national unity". Among the signatories: Mircea Druc former Moldovan prime-minister, Alexandru Mosanu former speaker of the Moldovan Parliament,Vitalia Pavlicenco president of the National Liberal Party (Moldova), Vladimir Beleag writer, Constantin Tnase director of the Moldovan newspaper Timpul de diminea, Val Butnaru president of Jurnal Trust Media, Oleg Brega journalist and activist, Nicu rn

soloist of the Moldovan rock band Gndul Mei, and Tudor Ionescu, president of the Romanian neo-fascist association Noua Dreapt, Valentin Dolganiuc, former Moldovan MP, Eugenia Duca, Moldovan businesswoman, Anton Moraru, Moldovan professor of history, Eugen Mihalache, vice president of People's Party, Dan Diaconescu and others[41][42][43]

[edit]Union

Marches

The newly-created Action 2012 and Union Council initiative groups organized several manifestations in support of the unification throughout 2012. The first one was a rally of several thousand people in Chiinu on 25 March 2012,[44] held as an aniversary of theUnion of Bessarabia with Romania on 27 March 1918. Similar rallies took place on 13 May[45] (which commemorated 200 years of theTreaty of Bucharest (1812) and the first Russian annexation of Bessarabia) and 16 September.[46] A union march was also held inBucharest on 21 October.[47] Smaller-scale manifestations took place in the Moldovan cities of Cahul and Bli on 22 July[48] and 5 August,[49] respectively. Various intelectuals and artists from both countries supported the marches,[50] while Moldovan Speaker Marian Lupu and Prime Minister Vlad Filat opposed them.[51]

[edit]Opinion [edit]Moldova

polls

The International Republican Institute in partnership with The Gallup Organization regularly conduct polls in the Republic of Moldova on several social and political issues.[52] The following results reflect the public stance in Moldova on the question of reunification

Date

Question

Fully support

Somewhat support

Somewhat oppose

Fully DK/NA oppose

Jan-Feb 2011[53]

Excluding the impact of potential Moldovan membership in the European Union, do you support unification of Moldova with Romania?

10%

18%

16%

47%

9%

Do you support or oppose the Aug-Sep reunification of the Republic of Moldova [54] 2011 with Romania?

11%

20%

16%

43%

10%

A poll conducted by IRI in Moldova in November 2008 showed that 29% of the population would support a union with Romania, while 61% would reject it.[55]

[edit]RomaniaA poll conducted in NovemberDecember 2010 and extensively analyzed in the study 'The Republic of Moldova in the Romanian public awareness' (Romanian: Republica Moldova n contiina public romneasc)[56] addressed the issue of reunification.

Question

Strongly agree

Partially agree

Partially disagree

Strongly disagree

DK/NA

Unification should be a national objective for Romania

23%

29%

23%

11%

15%

Sooner or later, the Republic of Moldova and 16% Romania should unite upon the German model

29%

16%

11%

28%

According to a poll conducted in Romania in January 2006, 44% of the population supports a union with Moldova, and 28% rejects it. Also, of those supporting the union, 28% support a union with Moldova, including Transnistria, while the rest of 16% support a union without Transnistria.[57] A survey carried out in Romania in June 2012 by the Romanian Centre of Strategic Studies showed the following results:[58]

Question

Yes

No

DK/NA

Do you believe that the language spoken in Bessarabia is Romanian?

71.9% 11.9% 16.2%

Do you believe that Bessarabia is Romanian land?

84.9% 4.7% 10.4%

Do you agree with the unification of Bessarabia with Romania?

86.5% 12.7% 0.8%

Do you consider that the unification of Bessarabia with Romania should be a priority for 55.2% 20.5% 24.2% Romanian politicians?

Question

Romanians Moldovans Russians DK/NA

Do you consider that Bessarabians are primarily: 67.5% [edit]See

28.2%

3.9%

0.3%

also Controversy over linguistic and ethnic identity in Moldova Romanian-Moldovan relations Bessarabia Romanian Land Greater Romania

[edit]Notes

1.

^ Charles King, "The Moldovans: Romania, Russia, and the Politics of Culture", Hoover Press, 2000, pg. 35

2. 3. 4.

^ King, The Moldovans...; Mackinlay, pg. 135 ^ Mackinlay, pg. 140 ^ (Romanian) Legea cu privire la funcionarea limbilor vorbite pe teritoriul RSS Moldoveneti Nr. 3465-XI din 01.09.89 (Law regarding the usage of languages spoken on the territory of the Republic of Moldova), published in Vetile nr.9/217, 1989

5.

^ (Romanian) "Podul de flori peste Prut. Puni de simire romneasc", in Romnia Liber, 8 May 1990.

6.

^ "Romania's relations with Moldova are more ambiguous. The instability of Ion Iliescu's pro-Moscow government in Bucharest has made both sides cautious in seeking ties with one another. In August 1990 Romania announced plans to help Moldova develop a national police force, and a month later the two signed a treaty of cooperation. Although each side has disavowed Romanian-Moldovan reunification, groups are lobbying for it in both republics" Martha Brill Olcott, "The Soviet (Dis)Union", in Foreign Policy, No. 82. (Spring, 1991), pp. 130

7.

^ Problems, Progress and Prospects in a Post-Soviet Borderland: The Republic of Moldova. Trevor Waters. "In an address to the Romanian parliament in February 1991 (on the first official visit to Romania by any leader from Soviet Moldova since its annexation), the then President Snegur strongly affirmed the common Moldovan-Romanian identity, noting that We have the same history and speak the same language, and referred to Romanians on both sides of the River Prut. In June 1991 the Romanian parliament vehemently denounced the Soviet annexation of Bessarabia and Northern Bucovina, describing the territories as sacred Romanian lands."

8.

^ "Moldavians seek to unite with Romania", in The Independent, June 4, 1991, Page 12

9.

^ King, p.345

10. ^ According to recent polls, 70 percent of Moldovans reject unification with Romania as "undesirable," while only 7-10 percent support it as necessary (Daily Report, December 30, 1992, p. 3) John B. Dunlop, "Will a Large-Scale Migration of Russians to the Russian Republic Take Place over the Current Decade?", in International Migration Review, Vol. 27, No. 3. (Autumn, 1993), pp. 605-629. 11. ^ Mackinlay, pg. 139

12. ^ George Berkin, "Secession blues", in National Review, September 9, 1991 13. ^ (Romanian) "Concepia politicii naionale a Republicii Moldova" at the Moldovan Parliament website 14. ^ http://www.e-democracy.md/elections/parliamentary/2009/results/ 15. ^ (Romanian) "Bsescu i-a dezvluit planul unionist secret", in Evenimentul Zilei, 3 July 2006 16. ^ (Romanian)"Basarabia costa bani grei" (Bessarabia costs a lot), in Cotidianul 17. ^ (Romanian) Ct ne cost idealul rentregirii? ("How Much The Ideal of Reunification Costs Us?") - Ziuay 18. ^ (Romanian) De ce Germania a numrat nemii, i nu banii din buzunarele lor? ("Why Did Germany Count The Germans, And Not Their Money?") - Timpul.md 19. ^ (Romanian) A fi sau a nu fi acestei guvernari? - aceasta-i intrebarea lui Voronin 20. ^ (Romanian) November 27, 2009. "Aprilie 2009 - nceputul procesului de revenire a Moldovei n componena Romniei" 21. ^ (Romanian) [1] (Tense relations between Romania and Moldova repaired with 100 million euros), Ziarul Financiar, 28 January 2010 22. ^ [2] (Moldovan-Romanian business and investment office to open in Chiinu), Financiarul, 4 February 2010 23. ^ (Romanian) UNIMEDIA i PUBLIKA TV i unesc eforturile pentru dezvoltarea mass-media din Republica Moldova), Realitatea TV, 9 December 2009 24. ^ (Romanian) Inaugurarea podului Lipcani-Rdui Jurnal de Chiinu, 15 February 2010 25. ^ (Romanian) "Republica Moldova a inceput daramarea gardului de sarma ghimpata de la granita cu Romania", hotnews.ro, February 10, 2010 26. ^ (Romanian) Mircea Druc este optimist i anun unirea inevitabil a Romniei cu Basarabia, tiri din Basarabia, 15 January 2010 27. ^ (Russian) .. : !, February 17, 2010 28. ^ "Interview with Mihai Ghimpu - Radio Free Europe", Radio Free Europe, 1 March 2010

29. ^ (Romanian) "Interview with Mihai Ghimpu - Timpul", September 29, 2009 30. ^ (Romanian) Ghimpu: Uniunea interstatal R. Moldova - Romnia ar fi cea mai mare prostie!. Unimedia.md, August 23, 2010 31. ^ (Romanian) [3] [4] 32. ^ (Romanian) [5] 33. ^ http://www.gandul.info/news/aproape-un-sfert-de-milion-depersoane-din-r-moldova-au-redobandit-cetatenia-romana-in-20-de-ani9566918 34. ^ http://www.soros.ro/ro/comunicate_detaliu.php?comunicat=187 35. ^ http://cetatenie.just.ro/ordine/ 36. ^ (Romanian) [6], page 89-90 37. ^ http://www.actiunea2012.ro 38. ^ http://www.hotnews.ro/stiri-cultura-8510245-webrelease-lansatplatforma-civica-actiunea-2012-sustine-uunirea-republicii-moldovaromania.htm 39. ^ http://www.publika.md/unirea-romaniei-cu-moldova--sustinuta-deplatforma-civica-actiunea-2012_294811.html 40. ^ http://www.tvr.ro/articol.php?id=102788 41. ^ http://www.radiochisinau.md/pages/view/2339 42. ^ http://www.jurnal.md/ro/news/a-fost-constituit-consiliul-unirii-216897/ 43. ^ http://consiliul-unirii.union.md/conferin-a-de-presa-i-declara-iaconsiliului-unirii 44. ^ http://www.arena.md/?go=news&n=11589&t=FOTO__Mar%C5%9Fu l_Unirii_la_Chi%C5%9Fin%C4%83u_marcat_de_incidente__ 45. ^ http://www.jurnal.md/ro/news/mar-ul-unirii-din-pman-pana-laambasada-rusiei-i-a-turciei-foto-219805/ 46. ^ http://www.ziuaveche.ro/international/externe/chisinau-16septembrie-marsul-unirii-live-video-120529.html 47. ^ http://unimedia.info/stiri/foto--video-marsul-unirii-din-bucuresti-s-aincheiat-fara-incidente-53441.html 48. ^ http://www.trm.md/ro/regional/cahul-altercatii-la-marsul-unirii/ 49. ^ http://www.jurnal.md/ro/news/violen-e-la-bal-i-video-live-text-224673/ 50. ^ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E9pBTwxZTpA 51. ^ http://www.jurnal.md/ro/news/filat-roaga-moldovenii-sa-nu-participela-mar-ul-unirii-303660/ 52. ^ http://www.iri.org/countries-and-programs/eurasia/moldova

53. ^ http://www.iri.org/sites/default/files/2011%20June%206%20Survey% 20of%20Moldova%20Public%20Opinion,%20January%2024February%207,%202011.pdf 54. ^ http://www.iri.org/sites/default/files/flip_docs/Moldova%20national%2 0voters%20survey%202010-09/HTML/index.html#/34/zoomed 55. ^ (Romanian) "29% din populatia R.Moldova este pentru unirea cu Romania", detailed statistics 56. ^ http://www.soros.ro/ro/publicatii.php 57. ^ (Romanian) Cotidianul. "Unirea cu Moldova", 23 January 2006 58. ^ http://www.rgnpress.ro/rgn_12/images/stories/2012/08/11sondaj_CRSS.pdf

[edit]References

Lenore A. Grenoble (2003) Language Policy in the Soviet Union, Springer, ISBN 1-4020-1298-5

John Mackinlay, Peter Cross (2003) Regional Peacekeepers United Nations University Press ISBN 92-808-1079-0

Charles King, "Moldovan Identity and the Politics of Pan-Romanianism", in Slavic Review, Vol. 53, No. 2. (Summer, 1994), pp. 345368.

Charles King, The Moldovans: Romania, Russia, and the politics of culture, Hoover Institution Press, Stanford University, 2000.ISBN 08179-9792-X

[edit]External

links (Romanian) Actiunea 2012 Official Website (Romanian) Romanism.net Website dedicated to Romanian-Moldovan

reunification

(Romanian) BBC Romanian: "Interviu cu preedintele PPCD Iurie

Roca" (March 2005)

(Romanian) Ziua: "Trdarea Basarabiei de la Bucureti" (June 2005) (Romanian) Hotnews.ro: March 2006 Poll (Romanian) Cotidianul: "Ci bani ne-ar costa unirea cu

Basarabia" (October 2006)

(English) Basescu Plan: Actions supporting unification with Romania

held in Chisinau (October 2006)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Movement_for_the_unification_of_Romania_and_Moldova

Controversy over linguistic and ethnic identity in MoldovaFrom Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A controversy exists over the national identity and name of the native language of the main ethnic group in the Republic of Moldova. The issue more frequently disputed is whether Moldovans constitute a subgroup of Romanians or a separate ethnic group. While there is wide agreement about the existence of a common language, the controversy persists about the use of the term "Moldovan language" in certain political contexts. The Declaration of Independence of 1991 calls the official language "Romanian",[1] and the first anthem adopted by the independent Moldova was "Deteapt-te, romne" ("Awaken, Romanian!"), the same as the anthem of Romania. Mirroring political evolutions in the country, the Constitution of Moldova (1994) calls the official language "Moldovan"[2] and establishes as anthem "Limba noastr" (Our language, without any explicit reference to its name). Moreover, the 2003 "Law of Nationalities"[3]

adopted by the Communist-

dominated Parliament explicitly designates the Romanians as an ethnic minority in Moldova. The officially sanctioned distinction between Moldovans and Romanians has been criticized by some members of the scientific community within Moldova.[4][5][6][7][8] and raised protests from certain segments of the population, especially intellectuals and students, at their turn inspired by several political forces.[9] [10][11] Furthermore, the problem strained Moldova's diplomatic relations with neighboring Romania.Contents[hide]

1 Principality of Moldavia (13591812)

o o o o

1.1 Moldavian identity in medieval chronicles 1.2 Selected foreign travelers about Moldavians 1.3 Early works in the local language of Moldavia 1.4 Diplomats' opinion

2 Bessarabia in the Russian Empire (18121918) 3 Bessarabia within Greater Romania (19181940) 4 Bessarabia within the Soviet Union (19401992) 5 Linguistic dispute 6 Popular perception 7 Political positions 8 Moldovan presidents on the language and identity of Moldovans

9 Moldovenism 10 See also 11 References 12 Bibliography

[edit]Principality

of Moldavia (13591812)

Hronicul vechimei a Romano-Moldo-Vlahilor (Chronicle of the durability of Romano-Moldo-Wallachians). Written by Moldavian Prince Dimitrie Cantemir.

Carte Romneasc de nvtur (Romanian Book of Learning). Written by Metropolitan of Moldavia, Varlaam Mooc.

[edit]Moldavian

identity in medieval chronicles

The chronicles of medieval Moldavia attested the names used by the inhabitants of Moldavia to refer to themselves as well as the common language and origin of Moldavians, Wallachians and Transylvanians. Stephen the Great, Prince of Moldavia (14571504), had ordered a chronicle to be written by a German royal courtier. The chronicle covered the years 14571499 and was titled Dy Cronycke Des Stephen Woywoda auss Wallachey or The Chronicle of Stephen Voivode of Wallachia.[12] The first important

chronicler of Moldavia, Grigore Ureche (15901647), states that the Romanians of theHungarian Kingdom and Moldavians have the same origin, since both "come from Rome".[13]Later, chronicler Miron Costin (16331691) wrote in one of his works that the "rightest and most authentic" name of Moldavians is Rumn (Romanian), a changed form of "Roman", and that this name was kept by them from the beginnings till to that day. He also mentioned that Moldavians never ask "do you speak Moldavian?", but rather "do you speak Romanian?".[citation needed] His son, chronicler Nicolae Costin (16601712), shared his father's opinion.[citation needed]The Wallachian chronicler Constantin Cantacuzino (16551716) explains that by Romanians he means Romanians from Wallachia, Transylvania, and Moldavia, as they all speak essentially the same language and have a common origin[citation needed] Dimitrie Cantemir (16731723), Prince of Moldavia and member of the Royal Academy of Berlin, wrote a history book called Hronicul vechimei a Romano-Moldo-Vlahilor (Chronicle of the Ancientness of the Romanian-Moldavian-Vlachs). In the introductory part, he calls it "a chronicle of the entire Romanian land" (Hronicon a toat ara Romneasc) that "later was divided into Moldavia, Wallachia and Transylvania" (care apoi s-au mprit n Moldova, Munteneasc i Ardealul) and mentions that the book was first written in Latin and then translated into Romanian (pre limba romneasc). He also claims that the usual name of Transylvanians, Moldavians and Wallachians is Romanian (carii cu toii cu un nume de obte romni s chiam).[citation needed]

[edit]Selected

foreign travelers about Moldavians

Several foreign travelers through Moldavia since the 16th century noted that locals called themselves "Romanians"[14] and their language "Romanian".[15] They also mention the awareness of a common Roman origin among the inhabitants of Moldavia and neighbouring Wallachia and Transylvania .[16] Georg Reicherstorffer (14951554), a Transylvanian Saxon, was the emissary of Ferdinand I of Habsburg in Wallachia and Moldavia. Reicherstorffer had traveled in 1527 and 1535 in the Principality of Moldavia and wrote his travel memoirs - Moldaviae quae olim Daciae pars, Chorographia (1541) and also Chorographia Transylvaniae(1550). Describing the geography of Moldavia he finds that "besides this name it is also called Wallachia" and then speaking about the Moldavian people he says that "the Roman [Italian] language still endures in this nation...so the Wallachians [from Moldavia] are an Italian nation, as they claim, from the old Romans".[17] A chronicler and mercenary from Verona, Alessandro Guagnini (15381614), traveled twice in Moldavia and helped Despot Vod (Ioan Iacob Heraclid) gain the throne in 1563. In his biography of the prince, "Vita despothi Principis Moldaviae", he described to the people of Moldavia:"This nation of Wallachians refer to themselves as Romana and say that they originate from exiled Romans of Italy. Their language is a mixture of Latin and Italian languages, so that an Italian can easily understand a Wallachian".[18] After a visit to Moldavia an anonymous traveler, probably an Italian Jesuit, wrote in 1587 a description of the people and found that "these people [Moldavians] belong to the Greek faith, they take kindly to everything that is Roman, maybe because of their corrupted language from Latin, or for the belief they have about their descent from the Romans, as they call themselves Romans".[19] Also, according to these sources, the Slav neighbours called Moldovans "Vlachs" or "Volokhs", a term equally used to refer to all the Romance speakers from Wallachia, Transylvania, and the Balkan peninsula.[20] Nicolaus Olahus (14931568), proeminent humanist, writes in Hungaria et Attila that the Moldavians have the same

language, rituals and religion as the Wallachians and that the only way to distinguish them is by their clothes. He also mentions that the language of Moldavians and other Vlach peoples was once Roman (Latin), as they all were colonies of the Roman Empire.[21] Thomas Thornton (17621814) wrote a book in 1807 about his numerous travels inside the Ottoman Empire and says that the Wallachian and Moldavian peasants call themselves "Rumun, or Roman", to distinguish themselves from boyars (local nobles), and that their language is a corrupt Latin.[22]

[edit]Early

works in the local language of Moldavia

Similarly, in 1643, The Moldavian Prince Vasile Lupu sponsored a book of homilies translated by Metropolitan Varlaam of Moldavia fromSlavonic into Romanian (pre limba Romeniasc) and titled Carte Romneasc de nvtur (Romanian Book of Learning) .[23] The foreword by Prince Lupu says that it is addressed to the entire Romanian nation everywhere (la toat semenia romneasc de pretutindeni). The book, also known as "Cazania of Varlaam" (Varlaam's Homiliary), was the very first printed in Moldavia and large numbers of copies spread in the neighboring provinces inhabited by Romanian speakers.[24] Furthermore, as a reaction to the translation in Transylvania of the Calvinist catechism into Romanian, Metropolitan Varlaam wrote in 1645 a "Response to the Calvinist Catechism" (Rspuns la Catehismul calvinesc) addressed to "the beloved Christians and with us one Romanian nation" from Transylvania [25] Vasile Lupu sponsored the printing in 1646 of the first code of laws in Moldavia titled Romanian Book of Learning (Carte romneasc de nvtur de la pravilele mprteti i de la alte giudee). The book was inspired by Byzantine tradition and in 1652 a virtually identical code of laws appeared in Wallachia, sponsored by Prince Matei Basarab.[26] Moldavian Metropolitan Dosoftei printed Dumnezaiasca Liturghie (Divine Liturgy) in Romanian (tiparita romneste). In his "Foreword to the Romanian nation" (Cuvnt depreuna catra semintia rumaneasca), Dosoftei calls the book a gift to the Romanian language (acest dar limbii rumnesti) translated from Greek (de pre elineasca) into Romanian (pre limba rumneasca).[27] Later, after the annexation of Bessarabia by the Russian empire, religious books written in the region commonly called the language "Moldavian". Thus a menologium printed in Chiinu in 1819 states it was translated from Slavonic into Moldavian ( ), as does a typicon from 1821 ( ).[28][29]

[edit]Diplomats'

opinion

Joseph II, Ruler of the Austrian Empire and Catherine II, Empress of Russia between 17621796, were willing to unite Moldavia and Wallachia, then under Ottoman sovereignty, in order to create an independent buffer state between Russia and Austria. The proposed independent state, named Dacia, would have contained Moldavia, Bessarabia and Wallachia, but Catherine wished it under Russian influence as it was presented in the so-called "Greek Project".[30] During the British Parliament debates of 1793, Mr. Whitebread, speaking about the initiative of France to erect an independent Belgium from Austro-Hungaria,

mentions Edmund Burke's initiative to form an independent state from the Ottoman Empire, named Circle of the Danube comprising Wallachia, Moldavia and Bessarabia.[31]Also, the memoirs of Sir James Porter (17201786), British diplomat, ambassador to the Sublime Porte in Istanbul from 1747 to 1762, mentions that, inside the Ottoman Empire, next in number to the Slavonians are the Rumelians or Romani, to whom the Moldavians and Wallachians belong, who call themselves Rumuryi.[32]

[edit]Bessarabia

in the Russian Empire (18121918)

In 1812, the eastern part of the Principality of Moldavia, called Bessarabia, which includes the current territory of Republic of Moldova (except for Transnistria) was ceded by the Ottomans to the Russian empire. The idea of a unified state including all Romanian speakers from Transylvania, Moldavia and Wallachia did not emerge before the 18th century, as it was "foreign to the spirit of the age"[33]

Starting with the 18th

century, a pan-Romanian national idea appeared, inspired by the German and French romantic nationalism. The young boyars from Moldavia and Wallachia educated in western universities returned home with ambitious political goals to modernize their countries, and sought to accomplish the ideal of a unified Romaniannation state. One important step was achieved in 1859, in a favorable international context, with the election of Alexandru Ioan Cuza as a common ruler of the autonomous principalities of Wallachia and (western) Moldavia. The newly formed Romanian state set among its primary tasks to inculcate the sentiment of belonging to a common Romanian nation to the illiterate rural majority through state-funded universal elementary school. The Romantic historical discourse reinterpreted history as a march towards the unified state. The creation of a standardized Romanian language and orthography, the adoption of the Roman alphabet to replace the older Cyrillic were also important elements of the national project.[33][34] Although still under foreign rule, the masses of Romanians in the multiethnic Transylvania developed a Romanian national consciousness, owing to their interaction with the ethnic groups, and as a reaction to the status of political inferiority and the aggressive nationalist politicies of the later Hungarian national state.[35][36] Such developments were not reflected in the Russian controlled Bessarabia. The Russification policy of the regime, more successful among the higher strata of the society, did not have an important effect on the majority of rural Moldavians. As Romanian politician Take Ionescu noted at the time, "the Romanian landlords were Russified through a policy of cooptation, the government allowing them to maintain leading positions in the administration of the province, whereas the peasantry was indifferent to the national problem: there were no schools for de-nationalization, and, although the church service was held in Russian, this was actually of little significance"[37][38] Furthermore, as University of Bucharest lecturer Cristina Petrescu noted, Bessarabia missed "the reforms aimed at transforming the two united principalities [Wallachia and Moldavia] into a modern state"[37][39] Irina Livezeanu claims that, moreover, at the beginning of the 20th century, peasants in all regions of the former principality of Moldavia were more likely to identify as Moldavians than the inhabitants of the cities.[40] In 1849, George Long writes that Wallachia and Moldavia are separated only by a political boundary and that their history is closely connected. About the latter he says that it is inhabited mainly by Wallachians who

call themselves Roomoon (Romanian).[41]Ethnologist Robert Gordon Latham, writes in 1854, that the name by which a Wallachian, Moldavian or a Bessarabian designates himself is Roman or Rumanyo (Romanian), a name the author also applies to the Romance speakers of Macedonia.[42] Similarly, in 1845, German brothers Arthur Schott and Albert Schott (historian) write in the beginning of their book - Walachische Mhrchen(Wallachian Fairy Tales) - that Wallachians live in Wallachia, Moldavia, Transylvania, Hungary, Macedonia and Thessaly.[43] The authors also mentions that Wallachians respond Eo sum Romanu (I am Romanian) when asked what they are.[44]

[edit]Bessarabia

within Greater Romania (19181940)

In 1918, Sfatul rii voted for the union of Bessarabia with the Kingdom of Romania. At the time, the Romanian army was already present in Bessarabia. US historian Charles Upson Clark notes that several Bessarabian ministers, Codreanu, Pelivan and Secara, and the Russian commander-in-chief Shcherbachev had asked for its intervention to maintain order.[45] He also mentions that after the arrival of Romanian army "all classes in Bessarabia, except the Russian revolutionaries, breathed a sigh of relief".[46] However, he adds that, at the beginning, the intervention had "roused great resentment among those who still clung to the hope of a Bessarabian state within the Russian Federated Republic" such as Ion Inculet, president of Sfatul Tarii and prime-minister Pantelimon Erhan who initially demanded the prompt withdrawal of the Romanian troops to avoid a civil war.[47] However, Inculet later welcomed Romanian general Brosteanu, who was in charge with the intervention, to a formal reception at Sfatul Tarii.[46] Given the complex circumstances, some scholars such as Cristina Petrescu and US historian Charles King considered controversial the Bessarabian vote in favor of the union with Romania.[48][49] On the contrary, historian Sorin Alexandrescu thinks that the presence of the Romanian army "did not cause the unification, [...] but only consolidated it". .[50] Similarly, Bernard Newman, who traveled by bike in the whole of Greater Romania, claimed there is little doubt that the vote represented the prevailing wish in Bessarabia and that the events leading to the unification indicate there was no question of a "seizure", but a voluntary act on the part of its people.[51] Quoting Emmanuel de Martonne, historian Irina Livezeanu mentions that, around the time of the union, Bessarabian peasants "still called thesemlves Moldovans". She adds Ion Nistor's explanation from 1915 of a similar earlier phenomenon in the Austrian-ruledBukovina, where peasants had called themselves Moldovans but "under the influence of the [Romanian] literary language, the term 'Moldovan' was then replaced by 'Romanian'", while "in Bessarabia this influence has not penetrated yet"[52] After the unification, a few French and Romanian military reports from the period mentioned the reticence or hostility of the Bessarabian ethnic minorities, at times together with Moldovans, towards the new Romanian administration.[53] Livezeanu also notes that, at the beginning, the Moldovan urban elite educated under Russian rule spoke predominantly Russian, and despised Romania as "uncivilized" and the culture of its elite, of which it knew very little.[54]

Owing partly to its relative underdevelopment compared to other regions of Greater Romania, as well as to the low competence and corruption of some of the new Romanian administration in this province, the process of "turning Bessarabian peasants into Romanians" was less successful than in other regions and was soon to be disrupted by the Soviet occupation.[55][56] Cristina Petrescu thinks that the transition between the Tsarist-type of local administration to the centralized Romanian administration alienated many Moldovans, and many of them felt they were rather occupied than united with "their alleged brothers".[57] Based on the stories told by a group of Bessarabians from the villages of the Balti county, who, notably, chose to move to Romania rather than live under the Soviet regime, Cristina Petrescu suggests that Bessarabia seems to be only region of the Greater Romania where the central authorities did not succeed "in integrating their own coethnics", most of whom "did not even begin to consider themselves part of the Romanian nation, going beyond their allegiance to regional and local ties" .[56]

[edit]Bessarabia

within the Soviet Union (19401992)

In 1940, Bessarabia, along with northern Bukovina, was incorporated into the USSR following an ultimatum sent to the Romanian government. The Soviet authorities took several steps to emphasize the distinction between the Moldovans and the Romanians, at times using the physical elimination of pan-Romanian supporters, deemed as "enemies of the people".[58] They were repressed by theNKVD and KGB for their "bourgeois nationalism".[59] The Soviet propaganda also sought to secure a separate status for the varieties of the Romanian language spoken in the USSR. Thus, it imposed the use of a Cyrillic script derived from the Russian alphabet, and promoted the exclusive use of the name "Moldovan language", forbidding the use of the name "Romanian language". The harsh anti-Romanian Soviet policy left a trace on the identity of Moldovans.[55]

[edit]Linguistic

dispute

Main articles: Languages of Moldova, Moldovan language, and Romanian language

A Limba noastr social ad in Chiinu, Moldova with the word "Romn" sprayed onto it.

There is essentially no disagreement that the standard form of the official language inMoldova (called Moldovan by the Constitution of 1994, also called Romanian or "the official language"/"limba de stat") is identical to standard Romanian. The spoken language of Moldova, in spite of small regional differences, is completely understandable to speakers from Romania and viceversa. [citationneeded]

The slight differences are in pronunciation and the choice of vocabulary. For

example, cabbage, drill and water melon are respectively "curechi", "sfredel" and "harbuz" in Moldova and Moldavia (Romania), but their synonyms "varz", "burghiu" and "pepene" are preferred in Transylvania and Wallachia. However, Daco-Romanian speakers might know and understand both forms of each term. Moldovan is widely considered merely the political name used in the Republic of Moldova for the Romanian language.[60]

[edit]Popular

perception

A poll conducted in Moldova by IMAS-Inc Chiinu in October 2009 presented a somewhat detailed picture of the perception of identity inside the country. The participants were asked to rate the relationship between the identity of Moldovans and that of Romanians on a scale between 1 (entirely the same) to 5 (completely different). The poll shows that 26% of the entire sample, which includes all ethnic groups, claim the two identities are the same or very similar, whereas 47% claim they are different or entirely different. The results vary significantly among different categories of subjects. For instance, 33% of the young respondents (ages 1829) chose the same or very similar, and 44% different or very different. Among the senior respondents (aged over 60), the corresponding figures were 18.5% and 53%. One of the largest deviation from the country average was among the residents of capital Chiinu, for whom the figures were 42% and 44%. The poll also shows that, compared to the national average (25%), people are more likely to perceive the two identities as the same or very similar if they are young (33%), are native speakers of Romanian (30%), have higher education (36%) or reside in urban areas (30%), especially in the capital city (42%).[61] Until 2007, some 120 000 Moldovan citizens received Romanian citizenship. In 2009, Romania granted 36 000 more citizenships and expects to increase the number up to 10 000 per month.[62][63]

Romanian

president Traian Bsescu claimed that over 1 million more have made requests for it, and this high number is seen by some as a result of this identity controversy. The Communist government(20012009), a vocal advocate of a distinct Moldovan ethnic group, deemed multiple citizenship a threat to Moldovan statehood.[64][65]

[edit]Political

positions

The major Moldovan political forces have diverging opinions regarding the identity of Moldovans. This contradiction is reflected in their stance toward the national history that should be taught in Moldovans schools. Forces such as the Liberal Party (PL), Liberal Democratic Party (PLDM) and Our Moldova Alliance

(AMN) support the teaching of the history of Romanians. Others, such as the Democratic Party (PD) and the Party of Communists (PCRM) support the history of Republic of Moldova.[66][67] [68] [69]

[edit]Moldovan

presidents on the language and identity of Moldovans

Mircea Snegur, the first Moldovan President (19921996), a somewhat versatile supporter of the common Romanian-Moldovan ethnic and linguistic identity "n suflet eram (i sunt) mai romn dect muli dintre nvinuitori." [70] "In my soul I was (and am) more Romanian than most of my accusers." Vladimir Voronin, President of Moldova (20012009), an adversary of the common Romanian-Moldovan ethnic identity, acknowledged at times the existence of a common language. Limba moldoveneasc este de fapt mama limbii romne. S-o numeti romn nseamn s neli istoria i s-i nedrepteti propria mam.[71] "Moldovan is in fact the mother of the Romanian language. To call it Romanian is to betray history and to commit injustice to your own mother." "Vorbim aceeai limba, chiar dac o numim diferit."[72] "We speak the same language [in Romania and Moldova], even though we call it differently." Mihai Ghimpu, speaker of the Moldovan Parliament and interim president (20092010), a staunch supporter of the common Romanian-Moldovan ethnic identity: "Dar ce am ctigat avnd la conducere oameni care tiau c limba e romn i c noi suntem romni, dar au recunoscut acest adevr doar dup ce au plecat de la guvernare? Eu nu am venit s manipulez cetenii, ci s le spun adevrul." [73] "What have we gained having as leaders people who knew that the language is Romanian and that we are Romanians, but acknowledged this truth only after they left office? I have not come to manipulate the citizens, but to tell them the truth."

[edit]MoldovenismMain article: Moldovenism The Soviet attempts, which started after 1924 and were fully implemented after 1940, to strongly emphasize the local Moldovan identity and transform it into a separate ethnicity, as well as its reiteration in the postindependence Moldovan politics, especially during theCommunist government (20012009), is often referred to as Moldovanism. The Moldovanist position refutes the purported Romanian-Moldovan ethnic identity, and also at times the existence of a common language.[74] US historian James Stuart Olson, in his book - An Ethnohistorical dictionary of the Russian and Soviet empires - considers that Moldavians and Romanians are so closely related to the Romanian language, ethnicity and historical development that they can be considered one and the same people.[75]

Since "Moldovan" is widely considered merely a political term used to designate the Romanian language,[76] the supporters of a distinct language are often regarded as anti-scientific or politicianist. A typical example is the Moldovan-Romanian dictionary.

[edit]See

also

A language is a dialect with an army and navy Movement for the unification of Romania and Moldova The case of Moldova is not singular. For instance, similar controversies exist in some republics originating from the formerYugoslavia. In spite of their linguistic and religious identity, there is a question whether Montenegrin and Serbian are the same or different ethnic groups. In most such cases, the tension seems to be between a stronger local identity and a weaker but wider identity. The questions are not solely cultural, but also political.[77]

[edit]References This article uses bare URLs for citations. Please consider adding full citations so that the article remains verifiable. Several templates and the Reflinks tool are available to assist in formatting. (Reflinks documentation) (October 2011)

1.

^http://www.europa.md/upload/File/alte_documente/Declaratia%20de%20Independenta%20a%20Repu blicii%20Moldova%202(1).doc

2.

^ Constitution of the Republic of Moldova. Article 13, Chapter 1. 1994-06-29. "The official language of the Republic of Moldova is Moldovan, written in Latin script."

3. 4.

^ "L E G E privind aprobarea Conceptiei politicii nationale de stat a Republicii Moldova". ^ Raisa Lozinschi. "SRL "Moldovanul"" (in Romanian). Jurnal de Chiinu. Archived from the original on 2008-08-22. Retrieved 2008-11-20. "Conf. Univ. Dr. Gheorghe Paladi, preedintele Asociaiei Istoricilor din R. Moldova: Noi ntotdeauna am susinut comunitatea de neam i ne-am considerat romni ca origine, etnie, limb."

5.

^ "Primul manifest tiinific mpotriva conceptului de limb moldoveneasc" (in Romanian). Observator de Bacu. 2008-03-05. Retrieved 2008-11-20.

6.

^ Alina Olteanu (2007-11-22). "Academia Romn combate "limba moldoveneasc"" (in Romanian). Ziua. Retrieved 2008-11-20.

7.

^ Eugenia Bojoga (2006). "Limb "moldoveneasc" i integrare european?" (in Romanian). Chiinu: Contrafort. Archived from the original on 2008-07-10. Retrieved 2008-11-20.

8.

^ "Rezoluie a lingvitilor privind folosirea inadecvat a sintagmei: "limba moldoveneasc"" (in Romanian). Gndul. 2007-11-01. Retrieved 2008-11-20.

9.

^ Michael Wines (2002-02-25). "History Course Ignites a Volatile Tug of War in Moldova". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-11-19.

10. ^ "A country-by-country update on constitutional politics in Eastern Europe and the ex-USSR". East European Constitutional review. NYU Law. 2002.

11. ^ About the controversy over Moldovan identity and language, in French : N. Trifon, "Guerre et paix des langues sur fond de malaise identitaire" in Rpublique de Moldavie : un tat en qute de nation, Paris, Non Lieu, 2010, P. 169-258. 12. ^ [Vladimir Beleag, tefan cel Mare ntr-o cronic german din secolul XVIhttp://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:GgSfLotgQ6kJ:www.contrafort.md/2004/1 15-116/721.html+Cronica+germana+stefan+cel+mare&cd=1&hl=ro&ct=clnk&gl=ro] 13. ^ Rumnii, ci s afl lcuitori la ara Ungureasc i la Ardeal i la Maramorou, de la un loc suntu cu moldovnii i toi de la Rm s trag. 14. ^ After a journey through Wallachia, Moldavia and TransylvaniaFerrante Capecci reports in 1575 that the inhabitants of these provinces call themselves "romneti" ("romanesci") : "Anzi essi si chiamano romanesci[= indeed they call themselves romanesci], e vogliono molti che erano mandati qu quei che erano dannati a cavar metalli..." in: Maria Holban, Cltori strini despre rile Romne, Bucharest, Editura Stiinific, 1970, vol. II, p.158 161. 15. ^ Frenchman Pierre Lescalopier writes in 1574 that those who live in Moldavia, Wallachia and most of Transylvania, "think they are true heirs of the Romans and call their language "romnete", that is Roman: "Tout ce pays: la Wallachie, la Moldavie et la plus part de la Transylvanie, a est peupl des colonies romaines du temps de Trajan l'empereur Ceux du pays se disent vrais successeurs des Romains et nomment leur parler romanechte, c'est--dire romain " in Voyage fait par moy, Pierre Lescalopier l'an 1574 de Venise a Constantinople, in: Paul Cernovodeanu, Studii i materiale de istorie medieval, IV, 1960, p. 444. 16. ^ The Croat Ante Verani states in 1570 that " Vlachs from Transylvania, Moldavia and Wallachia say that they are romani " : "...Valacchi, qui se Romanos nominant..." "Gens quae ear terras (Transsylvaniam, Moldaviam et Transalpinam) nostra aetate incolit, Valacchi sunt, eaque a Romania ducit originem, tametsi nomine longe alieno..." De situ Transsylvaniae, Moldaviae et Transaplinae, in Monumenta Hungariae Historica, Scriptores; II, Pesta, 1857, p. 120. 17. ^ "...pe lng aceasta se mai cheam i Valahia, de la Flacci o gint roman, cci romanii dup ce au nfrnt i nimicit pe gei, au adus aci coloniti sub conducerea unui oarecare Flaccus, de unde s-a numit mai nti Flaccia, apoi, prin stricarea cuvntului, Valahia. Aceast prere este ntrit de faptul c vorbirea roman mai dinuiete nc la acest neam, dar att de alterat ntru toate, nct abia ar mai putea fi neleas de un roman. Aadar, romnii sunt o seminie italic ce se trage, dup cum zic ei, din vechii romani..." Adina Berciu-Drghicescu, Liliana Trofin. Culegere de documente privind istoria Romanilor din secolele IV XVI, Partea I, Editura Universitatii, Bucureti, 2006 18. ^ Adolf Armbruster, Romanitatea romnilor: istoria unei idei, Editia a II-a, Editura Enciclopedic, Bucureti, 1993, pg. 47 19. ^ S.J. Magyarody, The Tsangos of Romania: The Hungarian minorities in Romanian Moldavia, Matthias Corvinus Publishing, pg. 45 20. ^ Roger-William Seton Watson, A history of the Romanians, Cambridge University Press, 1934 21. ^ Hungaria et Attila, pg. 59

22. ^ Thomas Thornton, The present state of Turkey, London, 1807 23. ^ CARTE ROMNEASC // DE NVTUR // DUMENECELE // preste an i la praznice mprte- // ti i la sfini Mari. // Cu zisa i cu toat cheltuiala // LUI VASILIE VOIVODUL // i domnul rii Moldovei din multe // scripturi tlmcit. din limba // sloveneasc pre limba Romeniasc. // DE VARLAAM MITROPOLITUL // De ara Moldovei. // n Tipariul Domnesc. n Mnstirea // a trei S(feti)teli n Iai de la Hs. 1643, The Book description on Biblioteca Judeean Petre Dulfu, Baia Mare 24. ^http://bisericaromanaortodoxalessandria.wordpress.com/video-3/sfantul-ierarh-varlaam-mitropolitulmoldovei/cazania-mitropolitului-varlaam-2/ 25. ^ iubiilor cretini i cu noi de un neam romni, pretutindeni tuturor ce se afl n prile Ardealului i n alte pri pretutindeni ce suntei cu noi ntr-o credin [1] 26. ^ http://moldova650.asm.md/node/42 27. ^ Nicolae Fustei, 330 de ani a celei de a doua editii a Liturghierului lui Dosoftei 28. ^ Mineiu de obte. Chiinu, Exarhiceasca Tipografie a Bassarabiei. 1819. preface 29. ^ Tipic biserices, adunat n scurt. Chiinu, Duhovniceasca Tipografie a Bessarabiei. 1821. preface 30. ^ Keith Hitchins, The Romanians: 1774-1866, Clarendon Press Oxford, 1996, pg44, pg.47 31. ^ The parliamentary register, Vol. 34, London, Burlington House, 1793, pg. 405 32. ^ Sir James Porter, Turkey: its history and progress, Hurst and Blackett, London, 1854, pg 25 33. ^a b

Lucian Boia, History and Myth in the Romanian consciousness, p 129

34. ^ Goina, Clin. How the State Shaped the Nation: an Essay on the Making of the Romanian Nation in Regio - Minorities, Politics, Society. Nprajzi Mzeum. No 1/2005. pp. 158-160, 161-163 35. ^ Sorin Mitu, National identity of Romanians in Transylvania 36. ^ Goina, Clin. How the State Shaped the Nation: an Essay on the Making of the Romanian Nation in Regio - Minorities, Politics, Society. Nprajzi Mzeum. No 1/2005. pp. 165-167 37. ^a b

Petrescu, Cristina. Contrasting/Conflicting Identities: Bessarabians, Romanians, Moldovans in

Nation-Building and Contested identities: Romanian & Hungarian Case Studies. Editura Polirom. 2001. pp. 154-155 38. ^ Livezeanu, Irina. Cultural Politics in Greater Romania: Regionalism, Nation Building, and Ethnic Struggle, 1918-1930.Cornell University Press, 2000. p.94 39. ^ Goina, Clin. How the State Shaped the Nation: an Essay on the Making of the Romanian Nation in Regio - Minorities, Politics, Society. Nprajzi Mzeum. No 1/2005. p. 165 40. ^ Livezeanu, Irina. Cultural Politics in Greater Romania: Regionalism, Nation Building, and Ethnic Struggle, 1918-1930.Cornell University Press, 2000. p.92 41. ^ George Long, Penny Cyclopaedia, volume XV, London, 1849, published by Charles Knight, pg. 304 42. ^ Robert Gordon Latham, The native races of the Russian Empire, London, 1854, pg.268 43. ^ Arthur Schott, Albert Schott, Walachische Mhrchen, Cotta, Stuttgart and Tbingen, 1845, pg. 3 44. ^ Arthur Schott, Albert Schott, Walachische Mhrchen, Cotta, Stuttgart and Tbingen, 1845, pg. 44 45. ^http://depts.washington.edu/cartah/text_archive/clark/bc_19.shtml

46. ^

a b

http://depts.washington.edu/cartah/text_archive/clark/bc_20.shtml#bc_20

47. ^ Charles Upson Clark, Anarchy in Bessarabia in Bessarabia: Russia and Roumania on the Black Sea. Dodd, Mead & Co., N.Y., 1927 48. ^ Petrescu, Cristina. Contrasting/Conflicting Identities: Bessarabians, Romanians, Moldovans in NationBuilding and Contested identities: Romanian & Hungarian Case Studies. Editura Polirom. 2001. p. 156 49. ^ King, Charles. The Moldovans: Romania, Russia, and the politics of culture. Hoover Press. 2000. p. 34 50. ^ Sorin Alexandrescu, Paradoxul roman, page 48. "Prezenta militara romaneasca in Basarabia nu a cauzat deci unirea - vointa politica pentru aceasta exista oricum - ci doar a consolidat-o 51. ^ Bernard Newman, "The new Europe", p. 245 52. ^ Livezeanu, Irina. Cultura si Nationalism in Romania Mare 1918-1930. 1998 p.115 53. ^ Livezeanu, Irina. Cultural Politics in Greater Romania: Regionalism, Nation Building, and Ethnic Struggle, 1918-1930.Cornell University Press, 2000. pp. 98-99 54. ^ Livezeanu, Irina. Cultura si Nationalism in Romania Mare.Humanitas 1998, p.123 "rusa era considerata adevarata limba publica a elitei urbane si a birocratiei. Moldovenii ce devenisera parte a acestei elite sub carmuirea ruseasca, desi nu-si uitasera neaparat limba materna, n-o mai foloseau in afara relatiilor de familie. Faptul ca moldovenii aveau un precar al identitatii culturale romanesti se reflecta in dispretul lor fata de Romania, tara pe care multi dintre ei o priveau ca . De asemenea dispretuiau cultura elitelor din Romania, desi o cunosteau foarte putin, sau poate tocmai de aceea" 55. ^a b

Charles King, The Moldovans: Romania, Russia, and the politics of culture, Hoover Institution

Press, Stanford University, 2000 56. ^a b

Petrescu, Cristina. Contrasting/Conflicting Identities: Bessarabians, Romanians, Moldovans in

Nation-Building and Contested identities: Romanian & Hungarian Case Studies. Editura Polirom. 2001. p. 154 57. ^ Petrescu, Cristina. Contrasting/Conflicting Identities: Bessarabians, Romanians, Moldovans in NationBuilding and Contested identities: Romanian & Hungarian Case Studies. Editura Polirom. 2001. p. 157 58. ^ Bugai, Nikolai F.: Deportatsiya narodov iz Ukainyi, Belorussii i Moldavii - Deportation of the peoples from Ukraine, Belarus and Moldova. Druzhba Narodov, Moscow 1998, Dittmar Dahlmann & Gerhard Hirschfeld. - Essen 1999, pp. 567-581 59. ^ John Barron, The KGB, Reader's Digest inc., 1974, ISBN 0-88349-009-9 60. ^ http://www.interlic.md/2008-05-26/5119-5119.html 61. ^ http://www.interlic.md/download/988/ 62. ^ http://www.gandul.info/news/basescu-vrea-sa-adopte-lunar-10-000-de-basarabeni-gandul-a-fost-azila-botezul-a-300-dintre-ei-de-ce-raman-studentii-moldoveni-in-romania-6074646 63. ^ http://www.interlic.md/2009-08-27/cetatzenia-rom-na-pentru-basarabeni-redob-ndire-saurecunoashtere-11649.html

64. ^ "Voronin acuz Romnia c pune n pericol statalitatea Republicii Moldova" (in Romanian). Bucharest: Realitatea TV. 2007-11-06. Retrieved 2008-11-19. 65. ^ Constantin Codreanu (2007-03-08). "Chiinul spune c Bucuretiul submineaz statalitatea Moldovei" (in Romanian). Bucharest: Ziarul Financiar. Retrieved 2008-11-19. 66. ^ http://www.adevarul.ro/international/europa/Istoria-Marian-Filat-Lupu-Vlad_0_128987562.html Vlad Filat, president of PLDM "Vom nva istoria noastr - cea a romnilor, aa cum este i firesc"/"We will teach our history - that of Romanians, as it is natural" Marian Lupu, president PD: "Dup prerea noastr, cea mai bun variant [...] ar fi istoria statului nostru istoria Republicii Moldova. Fr a pune accente pe momente sensibile, care ar putea duce la o scindare n societate.", a zis liderul Partidului Democrat, Marian Lupu/"In our opinion, the best option [...] would be the history of our state - the history of the Republic of Moldova. Without focussing on the sensitive moments, which would bring division in our society" 67. ^ http://www.formula-as.ro/2010/902/spectator-38/petru-bogatu-republica-moldova-nu-mai-poate-fiorientata-spre-moscova-12015 68. ^ http://www.pl.md/libview.php?l=ro&video_id=57&idc=69&id=832 69. ^ http://www.jurnalul.ro/stire-caravana-jurnalul-2007/scandalul-manualelor-de-istorie-integrata99589.html 70. ^ Mircea Snegur - Labirintul destinului. Memorii, Volumul 1-2, Chiinu, 2007-2008 71. ^ http://politicom.moldova.org/news/voronin-limba-moldoveneasca-este-mama-limbii-romane-38764rom.html 72. ^ http://www.evz.ro/articole/detalii-articol/847673/Voronin-ataca-Romania-din-toate-partile/ 73. ^ (Romanian)http://politicom.moldova.org/news/interviul-timpul-cu-mihai-ghimpu-203629-rom.html 74. ^ Gheorghe E. Cojocaru, The Comintern and the Origins of Moldovanism (Chiinu: Civitas, 2009) 75. ^ James Stuart Olson, An Ethnohistorical dictionary of the Russian and Soviet empires, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1994, pg. 477 76. ^ [2]: "It is widely accepted among linguists that Moldovan is the same language as Romanian" 77. ^ About the controversy over linguistic identity in Montenegro : Pavle Ivi in Standard Language as an Instrument of Culture and the Product of National History

[edit]Bibliography

John Barron, The KGB, Reader's Digest inc., 1974, ISBN 0-88349-009-9 Bugai, Nikolai F.: Deportatsiya narodov iz Ukainyi, Belorussii i Moldavii - Deportation of the peoples from Ukraine, Belarus and Moldova. Druzhba Narodov, Moscow 1998, Dittmar Dahlmann & Gerhard Hirschfeld. Essen 1999, pp. 567581

Charles Upson-Clark, Bessarabia, Dodd, Mead & Co., N.Y., 1927 Frederick Kellogg, A history of Romanian historical writing, Bakersfield, Ca., 1990

Charles King, The Moldovans: Romania, Russia, and the politics of culture, Hoover Institution Press, Stanford University, 2000. ISBN 0-8179-9792-X

S. Orifici, The Republic of Moldova in the 1990s : from the declaration of independence to a democratic state, Geneve 1994

A. Pop, The Soviet-Romanian controversy & Moldova's independence policy, Romanian review of international studies, 26, 1992

Hugh Seton-Watson, New nations & states, London 1997 Roger-William Seton-Watson, A history of the Romanians, Cambridge Univ. Press 1934 G. Simon, Nationalism & Policy toward nationalities in the Soviet Union, Boulder, S.F., Ca, & Oxford, 1991

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Controversy_over_linguistic_and_ethnic_identity_in_Moldova

Soviet occupation of Bessarabia and Northern BukovinaFrom Wikipedia, the free encyclopediaPart of a series on the

History of Moldova

Antiquity

Chernyakhov culture

Dacia, Free Dacians

Bastarnae

Early Middle Ages

Origin of the Romanians

Tivertsi

Brodnici

Golden Horde

Principality of Moldavia

Foundation

Stephen the Great

Early Modern Era

Phanariotes

United Principalities

Bessarabia Governorate

Treaty of Bucharest

Moldavian Democratic Republic

Sfatul rii

Greater Romania

Union of Bessarabia with Romania

The Holocaust in Romanian-controlled territories

Moldavian ASSR

Moldovenism

Moldavian SSR

Soviet occupation of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina

Soviet deportations

Republic of Moldova

Independence of Moldova

War of Transnistria

History of independent Moldova

Moldova portal

Part of a series on the

V

T

E

History of Romania

Prehistory

Cucuteni-Trypillian culture

Hamangia culture Bronze Age in Romania

Prehistory of Transylvania Dacia

Dacian Wars Roman Dacia

Origin of the Romanians Early Middle Ages Middle Ages

History of Transylvania Foundation of Wallachia Foundation of Moldavia Early Modern Times

Principality of Transylvania

Phanariotes

Danubian Principalities National awakening

Transylvanian School Organic Statute

1848 Moldavian Revolution 1848 Wallachian Revolution United Principalities

ASTRA

War of Independence Kingdom of Romania

World War I

Union with Transylvania Union with Bessarabia Greater Romania

Soviet occupation of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina World War II

Socialist Republic of Romania

Soviet occupation 1989 Revolution Romania since 1989 Topic

Timeline Military history Christianity

Romanian language By region

Banat

Bessarabia

Bukovina Dobruja

Criana

Maramure Moldavia

Muntenia

Oltenia Transylvania

Wallachia Commons

Centuries in Romania Romania portal

V

T

E

During June 28 - July 4, 1940, as a consequence of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, the Soviet Red Army militarily occupied[1][2][3]

the formerly Romanian held regions of Bessarabia, Northern Bukovina,

and Hertza, after the Romanian government, following the Soviet ultimatum, agreed to evacuate its troops and administration. The Soviet Union had planned to accomplish the annexation with a full-scale invasion, but the Romanian government, under a Soviet ultimatum delivered on June 26, agreed to withdraw from the territories in order to avoid a military conflict. Germany, who had acknowledged the Soviet interest in Bessarabia in a secret protocol to the 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, had been made aware prior to the planned ultimatum on June 24, but had not informed the Romanian authorities, nor were they

willing to provide support.

[4]

The Fall of France on 22 June is considered an important factor in the[5]

Soviet decision to issue the ultimatums.

On August 2, 1940, the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic was proclaimed as a constituent republic of the Soviet Union, encompassing most of Soviet-controlled Bessarabia, as well as the former Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic on the left bank of the Dniester. The regions inhabited by Slavic majorities (Northern Bukovina, the region of Khotin and Southern Bessarabia) were included in the Ukrainian SSR. The Soviet administration was marked by a series of campaigns of political persecution, including arrests, deportations to labour camps and executions. In July 1941, Romanian and Nazi German troops recaptured Bessarabia during the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union. A military administration was established and the region's Jewish population was either executed on the spot or deported to Transnistria, where further numbers were killed. In August 1944, during the Soviet Jassy-Kishinev Offensive, the Axis war effort on the Eastern Frontcollapsed, also due to a coup d'tat in Romania on 23 August 1944. Following this, the Romanian army ceased resisting the Soviet advance and later joined the fight against Germany, Romania thus effectively switching sides. Soviet forces not only entered Bessarabia, but also occupied entire Romania. Instrumental in this endeavor was the fact the Soviets captured most of the troops of the Romanian army they were facing before the start of the Jassy-Kishinev offensive, without a fight. This happened because the Romanian army obeyed the orders of the new Romanian administration not to oppose the Soviets. On September 12, 1944, Romania signed the Moscow Armistice with the Allies. The Armistice, as well as the subsequent peace treaty of 1947, confirmed the Soviet-Romanian border as it was on January 1, 1941.[7][8] [6]

Bessarabia, Northern Bukovina, and Hertza remained part of the Soviet Union until its dissolutionin 1991, when they became part of the newly independent states of Moldova and Ukraine. In its declaration of independence of August 27, 1991, the government of Moldova condemned the creation of Moldavian SSR, declaring that it was done in the absence of any real legal basis.Contents[hide][9]

1 Background

o o o

1.1 Soviet-Romanian relations during the interwar period 1.2 The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact 1.3 International context at the beginning of World War II

2 Political and military developments

o o o

2.1 Soviet preparations 2.2 Soviet ultimatum 2.3 Romanian withdrawal

o

2.4 Incorporation of the annexed territories into the USSR

3 Aftermath

o o o o

3.1 International reactions 3.2 Political developments in Romania 3.3 Romanian recovery of Bessarabia and wartime administration 3.4 Restoration of Soviet administration

4 Social and cultural consequences

o o o

4.1 Population movements 4.2 Deportations and political repression 4.3 Religious persecution

5 Legacy

o o o o

5.1 In the Soviet Union 5.2 Pre-independence Moldova 5.3 United States 5.4 Modern Moldova

6 Notes 7 References 8 External links

[edit]Background [edit]Soviet-Romanian

relations during the interwar period

Interwar Romania (1920-1940)

The Bessarabian question was both political and national in nature. According to the 1897 census,Bessarabia, at the time a guberniya of the Russian Empire, had a population 47.6% Moldovans, 19.6% Ukrainians, 8% Russians, 11.8% Jews, 5,3% Bulgarians, 3.1% Germans, 2.9% Gagauz.[10][11]

Which represents a strong decrease of the proportion of Moldovans/Romanians in

comparison to the census of 1817, conducted shortly after the Russian Empire annexed Bessarabia in 1812. According to the data of this census, the Moldovans/Romanians represented 86% of the

population.

[12]

The decrease was due to the settling by the Tsarist authorities of inhabitants of other[11]

nationalities on the territory of Bessarabia.

During the 1917 Russian Revolution, a National Council was formed in Bessarabia to manage the province in the new political situation.[13]

The council, known locally as Sfatul rii, initiated several[14][15]

national and social reforms, and on December 2/15 1917 declared Bessarabia an autonomous republic within the Russian Federative Democratic Republic. A rival council loyal to the Petrograd[14][16]

Soviet, the Rumcherod, was also formed and by late December the latter gained control over the capital, Chiinu, and proclaimed itself the sole authority over Bessarabia. With the consent of the Entente, and, according to the Romanian historiography, on the request of Sfatul rii, the Romanian troops entered Bessarabia in early January, and by February had pushed the Soviets over the Dniester.[17][18]

Despite later declarations by the Romanian prime-minster that the military[19]

occupation was made with the consent of the Bessarabian government,[20]

the intervention was met

with protest by the locals, notably by Ion Incule, president of Sfatul rii, and Pantelimon Erhan, head of the provisional Moldavian executive. The executive even authorised the badly-organised[21]

Moldavian militia to resist the Romanian advance, although with little success.[22]

In the wake of the

intervention, Soviet Russia broke diplomatic relation with Romania and confiscated the Romanian Treasure, at the time in Moscow for safekeeping. To calm the situation, the Entente representatives[18]

in Iai issued a guarantee that the presence of the Romanian Army was only a temporary military measure for the stabilisation of the front, without further effects on the political life of the region. In

January 1918, Ukraine declared independence from Russia, leaving Bessarabia physically isolated from the Petrograd government, and leading to the declaration of independence of the Moldavian Republic on January 24/February 5. Romanian pressure.[17] [22]

Some historians consider that the declaration was made under

Following several Soviet protests, on February 20/March 5, the Romanian

prime-minister, General Alexandru Averescu, signed a treaty with Soviet representative in Odessa, Christian Rakovsky, which provided that Romanian troops be evacuated from Bessarabia in the following two months in exchange for the repatriation of Romanian POWs held by the Rumcherod.[23]

After the White Army forced the Soviets to withdraw from Odessa, and the German[17][24]

Empire agreed to the Romanian annexation of Bessarabia in a secret agreement part of the Buftea Peace Treaty on March 5/18, the Romanian diplomacy repudiated the treaty, claiming the Soviets[18]

were unable to fulfil their obligations.

On March 27/April 9, 1918, Sfatul rii voted for the union of Bessarabia with Romania, conditional upon the fulfilment of the agrarian reform. There were 86 votes for union, 3 votes against union, 36 deputies refrained from voting and 13 deputies were absent from this session. The vote is regarded as controversial by several historians, including Romanian ones such as Cristina Petrescu and Sorin Alexandrescu.[25]

According to United States historian Charles King, with Romanian troops already in[26]