PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/26915 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2022-01-25 and may be subject to change.

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University

Nijmegen

The following full text is a publisher's version.

For additional information about this publication click this link.

http://hdl.handle.net/2066/26915

Please be advised that this information was generated on 2022-01-25 and may be subject to

change.

mixing ovaries and rosaries

Catholic religion and reproduction in the Netherlands, 1870-1970

Een wetenschappelijke proeve op het gebied van de Letteren.

Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctoraan de Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen

op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof.dr. C.W.P.M. Blom,volgens besluit van het College van Decanen in het openbaar te verdedigen

op woensdag 11 mei 2005 des namiddags om 1:30 uur precies door

Marloes Marrigje Schoonheim

geboren op 6 april 1976 te Middelburg

Promotor: Prof.dr. P. KlepCopromotor: Dr. Th. Engelen

Manuscriptcommissie: Prof.dr. P. RaedtsProf.dr. K. Matthijs, k.u.LeuvenDr. J. Kok, iisg Amsterdam

Table of Contents

Introduction 9

1 Denominations and demography 15— Historiography and methodology1 Aims of the chapter 15

1.1 The Dutch fertility decline and the concept of religion 162 Ireland and the religious determinants of fertility 21

2.1 Demographic disparities and the conflict in Northern Ireland 212.2 Catholic demographic behavior and the Irish border 242.3 Evaluating two decades of Irish demographic variety 262.4 Irish demographic historiography: a case of absent Catholicism 28

3 Revisiting the matter of religion and demography: Kevin McQuillan 293.1 Goldscheider’s propositions 303.2 The curriculum of the demographic historian 313.3 The Church’s pathways to regulating behavior 33

4 The Dutch Case 344.1 The comparability of Irish and Dutch Catholics 354.2 Dutch historiography on denominations and demography 37

4.2.1 Hofstee and the secondary importance of religion 384.2.2 Following up on Hofstee 404.2.3 Opening up the debate: international publications

and cooperation 444.2.4 Dutch demographic historiography:

a case of absent religion 505 Unraveling the concept of religion: sociological methods 53

5.1 Single factors determining religiosity 545.2 Theories on the determinants of religiosity 575.3 Sociology of religion and its gains for historical demography 59

6 Mixing methods: the study of Catholic religion and reproductionin the Netherlands, 1870-1970 626.1 Religion on a macro level in the Netherlands:

social sectarianism 636.2 Competitive motives for demography: meso level 64

6.3 Transmuting dogma into demography: micro level 657 Conclusion 67

2 A nationwide ‘intercom’ for demographic directives 69— Pillarization and moralization1 Aims of the chapter 69

1.1 The emancipation of the Dutch Catholics 702 Pillarization: the denominational pathway to propagating morality 72

2.1 Pigeon-holing on a large scale: history and meaning 722.2 Periodization: rise, culmination and fall 752.3 The origins of pillarization 782.4 State discipline and the confessional pillars 80

3 The moral nation 823.1 Diagrammatized morality 833.2 The ‘moralization offensive’:

from Liberal initiative to confessional crusade 863.3 From Neo Malthusianism to the Public Decency Act 883.4 The women’s issue: a moral issue 903.5 Morality, pillarization and demography 95

4 The Catholic ‘intercom’ for demographic directives 974.1 The Catholic National Party: setting the tone in the pillar 984.2 Catholic organizational pillarization: snaring the flock 1014.3 The clergy: one and all supportive of Catholic pillarization 105

5 Conclusion 107

3 Scaling down the religious determinant in the municipality 111— Demographic, socio-economic and cultural situations of three case studies1 Aims of the chapter 111

1.1 Intentional wrong or farmers’ stubbornness:political dissent in Mheer 112

2 Getting round to case studies:selecting Dutch Catholic municipalities 1152.1 In the midst of all transitions: 1930 1152.2 The negative case analysis and the selection of municipalities 1172.3 Data and variables 120

3 General characteristics of the case studies: location and size 1233.1 Mheer and St Geertruid 1233.2 Roosteren and Ohe en Laak 1253.3 Grave and Escharen 127

4 Deviating demographic behavior? Fertility and nuptiality 1314.1 Mheer and St Geertruid 1314.2 Roosteren and Ohe en Laak 134

4.3 Grave and Escharen 1365 Demographic causes of deviating behavior: sex-ratios,

infant mortality 1395.1 Mheer and St Geertruid 1395.2 Roosteren and Ohe en Laak 1445.3 Grave and Escharen 148

6 Socio-economic causes: industrialization and agriculturalmodernization 1536.1 Mheer and St Geertruid 1536.2 Roosteren and Ohe en Laak 1576.3 Grave and Escharen 161

7 Cultural causes: mobility and religious multiformity 1657.1 Mheer and St Geertruid 1667.2 Roosteren and Ohe en Laak 1687.3 Grave and Escharen 170

8 Conclusion 173

4 “We put up with what we were told” 178— Catholic women on the regulation of fertility1 Aims of the chapter 178

1.1 The Vatican, morality and post-war restoration 1792 Affecting fertility: the doctrines of the Catholic Church 182

2.1 Sin, Church and forgiveness 1822.2 Marriage, parenthood and the gendered division of tasks 1842.3 Sexuality versus procreation 187

3 Internalizing doctrines: Catholic attitudes to family planning,contraceptives, sexuality and motherhood 1893.1 Persisting in deviance: desired family size and family planning 1913.2 Only if Church-approved: the use of methods of birth control 1933.3 Practicing what is preached: sexual experience 1963.4 Compliance and a sense of duty: the motherhood ideology 1993.5 Effectiveness of indoctrination: variation among Catholics 204

3.5.1 Socio-economic position and education:the Catholic exception 204

3.5.2 Religiosity and the obedience to Church doctrines 2064 Pathways of pronatalism: women’s accounts of indoctrination 208

4.1 The sources: letters of mothers of large families 2094.2 Imposing the rules: the Church’s means of indoctrination 211

4.2.1 The priest’s marital message 2114.2.2 Deterrence: Church punishment 2144.2.3 By courtesy of the Church:

permission to practice birth control 216

4.2.4 “Father, I abused matrimony”: confession 2204.2.5 Crossing the threshold: house visits 223

4.3 A matter of the conscience: faith, fear and guilt 2254.3.1 ‘God tempers the wind to the shorn lamb’:

faith and family size 2254.3.2 The price of sinning: guilt and fear 227

4.4 The Catholic social standard of fertility 2314.4.1 Youth: the mother-to-be 2314.4.2 A matter of mutual agreement: pronatalism in marriage 2334.4.3 Just like everyone else:

fertility and the Catholic community 2345 Conclusion 237

5 That rag freedom! 241— Catholic faith and fertility in the Netherlands, 1870-19701 Aims of the chapter 2412 Catholic religion and reproduction in the Netherlands, 1870-1970:

conclusions 2413 The final blow for Catholic fertility, 1960-1970 2444 Mixing ovaries and rosaries: observations 249

List of graphs 252List of tables and maps 254Bibliography 255Word of thanks 278Summary 281Samenvatting 284Curriculum vitae 287

Introduction

In her 1963 novel The Unicorn Iris Murdoch ventured to demythologize Christian-ity.1 The life of the leading character of the book, a woman who rejects the worldand allows herself to be imprisoned, is an imitation of the life of Christ. Togetherwith the other characters of the book, the leading character is enslaved in the‘magical’ cycle of the events that portray the odd relationship between spirituality,sex and power. Throughout the story the scene of action unfolds as an erotic prisonmasquerading as a place of religious retreat, demonstrating that the impulse toworship is ambiguous and rarely pure. Only one of the characters in The Unicornremains outside the chain of power that connects human sexuality and spirituality– a Platonist who watches the events of the story from a distance and describesthe automatic communication of power and suffering in which the others areinvolved. “In morals, we are all prisoners,” this ageing contemplative is foundarguing, “but the name of our cure is not freedom.”2

The demythologization of Christianity has been a particularly bitter pill for theRoman Catholic Church. Unlike the Anglican Church or many of the Protestantdenominations, it refused to take part in any of the shifts in moral norms and val-ues that have characterized the history of secularization in many industrializedcountries during the twentieth century. With every statement on current moralitythe Vatican, claiming to represent the whole Catholic world community, not onlydemonstrated its dismay and despair but also the growing gap between the Church’smoral doctrines and the ethical standards held by large population groups,amongst them the Church’s own members. With Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger’s July2004 letter to the bishops, for example, the Vatican officially denounced femi-nism. In its effort to blur differences between men and women, Ratzinger argued,feminism eroded the institution of the family based on a mother and a father and

1 Iris Murdoch, The Unicorn (London 1963), Peter Conradi, The saint and the artist: a studyof the fiction of Iris Murdoch (London 2001) 133-166.2 Murdoch (1963) 114.

created a “virtual” equivalency of homosexuality and heterosexuality.3 However,Ratzinger’s moral reprimand has hardly affected the activities of feminists or thegrowing numbers of advocates for same-sex marriage – nor will many nominalCatholics feel concerned about his message.4 The consequences of the statementimpinged mainly on the devout part of the flock, as the document formed a possi-ble occasion for Church conservatives to condemn any form of advocacy forwomen in the Catholic community. Additionally, Ratzinger’s letter affected devoutCatholics in particular because it forced them to divide their loyalty between theirdoctrinal Church and a modernizing secular society with entirely different moralstandards. An early 1990s study on the factor of religion in the psychological prob-lems of Catholic women showed the troubles of Catholics brought up in a closed,hierarchic community before the 1960s when the Church still decided how onelived. Nowadays, members of this group in particular find little countenance in theChurch to give a meaning and direction to their life. “In the present society inwhich consciousness and autonomy occupy the center stage, they are not able tomanage with the doctrine that has been preached to them.”5 Moral norms and val-ues that have been enforced, and which the Vatican still holds true, clash withthose of the non-Catholic society and cause moral dilemmas.

The gap between the behavioral norms and values of the Catholic Church andthose of society developed when, at the end of the nineteenth century, in industrial-izing countries the demographic transition started. Mortality, in particular infantmortality, declined. While a higher number of children reached adulthood, socio-economic motivations to have children diminished with the end of child labor. Theintroduction of compulsory school attendance and the professionalization of thelabor market required investment in higher education. As a result, fertility plan-ning, for a large part of the population of industrialized countries, in the course ofthe twentieth century became financially as well as socially a most reasonable thingto do. With the wider large-scale practice of birth control, the postponement orabandonment of marriage was no longer required as a means to limit a popula-tion’s fertility. Hence, from the first decades of the twentieth century a third aspectof the demographic transition manifested itself with the decline of the age at firstmarriage and the increase of proportions married.

10 mixing ovaries and rosaries

3 Joseph Ratzinger and Angelo Amato, ‘Letter to the bishops of the Catholic Church on thecollaboration of men and women in the Church and the world’ (May 31, 2004). RetrievedJanuary 26, 2005, from http://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/ cfaith/ documents/rc_con_cfaith_doc_20040731_collaboration_en.html4 United Press International, ‘Analysis: gay marriage around the globe’ (July 15, 2003).Retrieved January 26, 2005 from http://www.upi.com/view.cfm?StoryID=20030714-073510-5671r5 Hennie Derksen, De parel in het zwarte doosje: de rol van het geloof in de psychische pro-blemen van katholieke Limburgse vrouwen (Nijmegen 1994) 28.

Though the demographic transition theory holds an established position in his-toriography, several anthropologists have formulated severe criticisms of the waythe concept has been studied by demographers, historians and social scientistsalike. Scholars studying aspects of the demographic transition have tended to iso-late cause and effect in empirical generalizations or ‘laws’ in order to focus on onedimension through time – and have been criticized of overdoing this tendency.Additionally, scholars working on the demographic shift were inclined to picturecountries as on a single continuum of change from traditional to modern andfocused too much on Western demographic behavior – two aspects of the studieson the demographic transition that have also been disputed by anthropologists.“There is little question about the fact of the demographic transition in very broadterms,” argued Dudley Kirk from Stanford University, usa. The late professor insociology and population studies wrote the foreword to Culture and reproduction: ananthropological critique of demographic transition theory, a volume to which bothdemographers and anthropologists contributed. But, Kirk admitted, for the an-thropologists, the research on the topic focused too much on the “how” rather thanthe “why” of the transition. “Thus demographers point with a certain justifiablepride to the sophisticated and meticulous measurement of levels and trends in fer-tility and mortality and to multivariate analysis of the association between socio-economic measures, especially education, with progress in the reduction of fertil-ity. Demographers are much more involved with the objective mechanics thanwith the subtleties of attitudes, motivations and behavior of individuals that collec-tively bring this about. They all too often ignore the cultural and historical contentwhich promotes or retards reduction of the birth rate (…),” Kirk argued in Cultureand reproduction. “Why fertility occurs at all and why it occurs at different ratesand in different ways in different countries is inadequately explained by demogra-phers.”6

The anthropological perspective on the way the processes and causes of thedemographic transition have been studied has provided scholars working on thetheory with constructive criticism. Multivariate analyses of data sets that have beencarefully collected on an individual level showed the correlation between religionand demography. However, few studies have focused on the interpretation of thiscorrelation. For example, historiography indicated that the Catholic religion hashad a particular strong effect on fertility levels and development in industrializedcountries – at least until the last quarter of the twentieth century. But what is themechanism behind the influence of religion on demographic behavior? That is thematter this book addresses while researching fertility and nuptiality among Cath-olics in the Netherlands.

introduction 11

6 Penn Handwerker, Culture and reproduction: an anthropological critique of demographictransition theory (Boulder and London 1986) xi-xii.

At the time of the population census of 1930, in the middle of the fertilitydecline, only 14% of the Dutch declared they did not to belong to any denomina-tion. Back then, the Netherlands were still a profoundly Christian nation where themajority of the population was Protestant. In 1930 the majority of the Protestantswere members of the Dutch Reformed Church (Nederlandse Hervormde Kerk),divided in four ‘branches’ ranging from liberal to conservative, who made up34.4% of the whole population.7 Catholics made up over 36.4% of the population ofthe Netherlands.8 Despite their minority in numbers, the fertility behavior of theCatholic part of the population deviated from that of the Protestant and non-denominational Dutch to the extent that that it altered the average birth rate of thewhole of the Dutch nation. Only in the second half of the twentieth century didCatholic fertility rates subsequently converge with those of other religious groupsin the Netherlands.

This study will focus on the nature of the religious determinants of Catholicreproductive behavior in the Netherlands between the start of the fertility declinein the late 1870s until the end of it in the early 1970s. In doing so, the scope of thisthesis extends beyond merely the strong ideas of the Catholic Church on the issuesof reproduction and the practice of birth control. This research includes an investi-gation into the influence of religion on Catholic fertility on different levels of Dutchsociety. Only by gaining insight into the way Dutch Catholicism affected fertilityboth on a macro, meso and micro level, can the mechanism behind the effects ofreligion on demographic behavior be revealed as well as the particularity of thatinfluence in the Netherlands.

The question of how the organization of the Catholic religion on national,municipal and individual levels affected the fertility levels of the Catholic popula-tion will be preceded by a historiographical and methodological introduction to thesubject. Chapter 1 deals with the way the influence of religion on demographicbehavior in general and Catholicism in particular have been studied abroad as wellas in the Netherlands. This chapter covers the way the fertility decline developed inthe Netherlands as well as the current status quo maintained in Dutch researchwhere it concerns the Catholic determinant of fertility. Taking stock of both natio-nal and international historiography entails not only the Dutch characteristics ofthe research topic but also provides us with a clear understanding of what the anal-ysis of Catholic determinants of fertility in previous research has lacked. In chapter1 it will also become clear that because Western European fertility was restrainedby nuptiality, marriage behavior will be mentioned frequently in this thesis despiteits main focus on the effects of religion on fertility.

12 mixing ovaries and rosaries

7 Hans Knippenberg, De religieuze kaart van Nederland: omvang en geografische spreiding vande godsdienstige gezindten vanaf de Reformatie tot heden (Assen 1992) 106-120, 268.8 Ibid, 273.

Chapters 2, 3 and 4 discuss the way Catholic religion in the Netherlands wasorganized to such an extent that it was able to affect reproductive behavior of thewhole of the Catholic population group. In the last decades of the nineteenth cen-tury a social compartmentalization along ideological lines developed that madereligion into the fundament of the social structure of the Netherlands. This pro-vided (Christian) religious institutions with considerable capacity to check onobedience to their doctrines, a power extending from the political organizations viathe leisure clubs to the bedrooms of the believers. Moreover, it made respect paidto the church’s moral authority into a standard – even for people without a reli-gious denomination. This infrastructure for the interference of religion withdemographic behavior on a national level remained intact until the 1970s. Evenmore so than the orthodox Protestant churches (including the Gereformeerde kerkenand the more conservative branches of the Dutch Reformed Church), the RomanCatholic Church (or simply the Church) profited immensely from the socialcompartmentalization in the Netherlands – and in particular its promotion of the‘pronatalist ideology’ stemming from the Catholic doctrines that stimulated fertil-ity.9

The study of the relationship between religion and demography on a macrolevel offers an explanation for the conditions that provided the Church with socialpower to impose a code of behavior on parts of the population. The third chapterfocuses attention on the influence of Catholicism on reproduction on the mesolevel of Dutch society. The motivations for couples to limit their family size, a pres-sure that increased with the ongoing development of the industrialization andmarket-oriented economy during the twentieth century, by no means passed theCatholics in the Netherlands by. Data from particular Catholic municipalitiesshow the socio-economic and cultural circumstances that increased or rather di-minished the influence of religion on fertility behavior. Descriptive statistics cover-ing the middle of the fertility decline show why in some Catholic municipalitiesmotivations for family planning strengthened to the extent that fertility behaviorwas altered, while other municipalities maintained the fertility levels that corre-sponded with Catholic pronatalism.

introduction 13

9 In this publication, orthodox Protestants refer to Christelijk gereformeerden, members of(Vrije) evangelische gemeenten, (Oud-)gereformeede gemeenten, (Synodaal) gereformeerden andGereformeerden (vrijgemaakt), together constituting 9.4% of the 1930 Dutch population, butalso to moderate conservative (Ethischen) and conservative branches of the Dutch ReformedChurch (Confessionelen and Gereformeerden) that included 78% of its members in 1920.Knippenberg (1999) 66-119.The collective term ‘liberal Protestants’ refers to Remonstran-ten, (Hersteld) Lutheranen, Doopsgezinden, Baptisten, Apostolischen and members of the Sal-vation Army, together constituting 3% of the 1930 Dutch population, and the 22% Vrij-zinnigen among the 1920 Dutch Reformed Church members. Knippenberg (1999) 110-156.

Chapter 4 reports on an investigation into the influence of the Catholic religionon fertility related decisions on a micro level. Both abroad and in the Netherlands,surveys conducted from the 1930s onwards have shown in what ways Catholic doc-trines affected norms and values of individuals, resulting in reproduction behaviorthat deviated from members of other denominations. In chapter 4, the directives ofthe Catholic Church that particularly affected reproductive behavior will be dis-cussed, as well as the pathways via which they could be enforced on individuals.Testimonies of Catholic women bear witness to the moral codes they were pro-vided with and of the way they turned into a standard of behavior.

For her research on the causes, content and consequences of domestic service asa stage of life for Dutch women in the second half of the nineteenth and first half ofthe twentieth century, the demographic historian Hilde Bras combined the analysisof life course data of domestic servants with qualitative research based interviews,biographies and letters.10 Like Bras’ study, this research into the role of religion infertility behavior ventures to use a multi-method approach. Both quantitative andqualitative research has been performed to retrieve the mechanism behind correla-tions between religion and the reproduction behavior of the Catholic population ofthe Netherlands. While investigating the reproductive behavior of Dutch Catholicsduring the period of the national fertility decline, this study intentionally did not de-velop into a quantitative research based on highly advanced statistical methods. Nei-ther did the exploration of religion, as an ideology that is a complex of convictionsand attitudes by which means people give meaning to their existence, result in atheological reference book. Mixing ovaries and rosaries is a historical research on theinfluence of religion on Catholic reproduction in the Netherlands and aims at beinginterdisciplinary both in its audiences and in the methods it applies. As Bras showsin her excellent study of the maidservants, the combination of quantitative and quali-tative data proves that attention to historical patterns does not rule out notice of theexceptional, the multidimensional character of time and the whimsicality of change.

Historical demographers rightfully have indicated that in industrialized, moredeveloped countries fertility and nuptiality characteristics of Catholics deviatedfrom those of other denominations – differences that declined with the progres-sion of the national fertility decline. Anthropologists on the other hand have beenright in emphasizing that, to speak with Murdoch, the circumstances under whichCatholics have been ‘morally imprisoned’ have been different. The characteristicsand causes of fertility behavior of Dutch Catholics between 1870 and 1970 offer agood opportunity to show how both approaches complement each other well.

14 mixing ovaries and rosaries

10 Hilde Bras, Zeeuwse meiden: dienen in de levensloop van vrouwen, ca. 1850-1950 (Amster-dam 2002).

Chapter 1

Denominations and demography

— Historiography and methodology

1 Aims of the chapter

“Now they tell us they’ll breed us out,” the prominent loyalist politician Ian Paisleyremarked in 1988 about high fertility among Catholics in Northern Ireland. “Iwould say to them Protestants also breed” he added.1 Paisley’s statement mirrors adespair that, even in the 1980s, was not completely groundless where it concernedthe future of the Protestant majority in numbers in Northern Ireland. In severalWestern European countries as well as in the usa, fertility rates among Catholicpopulation groups remained high while those among other denominations de-clined during the late nineteenth and twentieth century. Apparently, Catholic reli-gion determined a particular reproduction pattern, resulting in deviant demo-graphic behavior that, eventually, could even change political balances.

This chapter concerns the quest for a well-considered method to study theinfluence of religion on Catholic reproduction in the Netherlands during the sec-ond phase of the demographic transition period. How has the subject been treatedin international and national historiography? Regarding the former, studies onreligion and Irish demography at the end of the transition period offer an interest-ing case in paragraph 2: demographic characteristics of Catholics were studiedboth in the homogeneous Catholic Republic and in Northern Ireland where Catho-lics constituted a minority. Subsequently, in paragraph 3, Kevin McQuillan’s ideason the best way to study religious determinants of demography will be discussed,as advocated in his recent contribution to the methodology of the subject. Afterhaving established several do’s and don’ts in the international research field of thesubject, methods used in the demographic historiography of the Netherlands willbe focused on in paragraph 4. What have the views of Dutch scholars been on themechanism behind the influence of religion on demography? In paragraph 5 theevaluation of international and national methods of research will be put into thecontext of definitions and methods developed by sociologists of religion. Finally,

1 Ian Paisley in the Irish Times 11 June 1988 quoted in Cormac Ó Gráda and BrendanWalsh, ‘Fertility and population in Ireland, North and South’, Population Studies 49 (1995)259-279, 259.

paragraph 6 shows how the stock taken of historical and social scientific ap-proaches used abroad and in the Netherlands to study the impact of religion ondemography results in the methodological structure of Mixing ovaries and rosaries.But first the development of fertility and nuptiality in the Netherlands will be dis-cussed briefly. Subsequently the subject will be religion as it left its mark on thedemography of the period between 1870 and 1970.

1.1 The Dutch fertility decline and the concept of religion

The last phase of the demographic transition in the Netherlands developed differ-ently from that of other western European countries.2 The onset of the fertilitydecline was late in the nineteenth century – only after 1875 marital fertility passed,as Onno Boonstra and Ad van der Woude observed, “what has turned out to be itslasting downward turning point.”3 Moreover, in the Netherlands the fertility de-cline was more gradual than in other countries and lasted longer throughout thetwentieth century. The birth rate decreased from 37‰ to 33‰ between 1875 and1890, dropped under the level of 30‰ after 1900 and settled under the 20‰ levelonly in the late 1960’s and 70’s. The languid development of the Dutch fertilitydecline contrasted sharply with for example that of Belgium. While in the nine-teenth century the average marital fertility rate of the Netherlands had been quiteequal to that of Belgium (about 355 per 1000 married women), from 1900 until the1960s Dutch marital fertility remained about 35% higher than that of the Belgianpopulation.4

The decline of fertility formed the last phase of the demographic transition.After a decline in the mortality rates, particularly those among infants, populationincreased.5 Nuptiality changed when the proportion married among the Dutchpopulation increased slightly from 85% in the first half of the nineteenth century to

16 mixing ovaries and rosaries

2 Ansley Coale and Roy Treadway, ‘A summary of the changing distribution of overall fer-tility, marital fertility, and the proportion married in the provinces of Europe’, AnsleyJ. Coale and Susan Cotts Watkins (ed.), The decline of fertility in Europe (Princeton 1986)31-181.3 Onno Boonstra and Ad van der Woude, ‘Demographic transition in the Netherlands: astatistical analysis of regional differences in the level and development of the birth rate andof fertility, 1850-1890’, A.A.G. Bijdragen 24 (Wageningen 1984) 1-59, 12.4 Evert Hofstee, Korte demografische geschiedenis van Nederland van 1800 tot heden (Haarlem1981) 132; Ron Lesthaeghe, ‘Vruchtbaarheidscontrole, nuptialiteit en sociaal-economischeveranderingen in België, 1846-1910’, Bevolking en gezin 72 (1972) 251-305; Chris Vanden-broeke, ‘Karakteristieken van het huwelijks- en voortplantingsgedrag in Vlaanderen enBrabant, 17e-19e eeuw’, Tijdschrift voor sociale geschiedenis 21 (1976) 107-145.5 Hofstee (1981) 143.

90% in the subsequent part of the century.6 The decline of the marital age, anotherinvariable component of the demographic transition in Europe, preceded thedownward trend of fertility too. Between 1860 and 1910, the average age at firstmarriage declined from 29 to 27,5 for males and 28 to 26 for females. The dropcontinued during the 1930s and again after the Second World War to reach a bot-tom level of 25 years for men and 22.5 for women in 1975.7

The causes for the changes in nuptiality behavior were diverse. Economic andsocial trends, like the introduction of family planning and the emancipation ofwomen, determined public values regarding the ‘appropriate’ marital age thatdirected the long-term development of nuptiality behavior.8 Changes in socio-eco-nomic circumstances, such as the economic crisis of the 1930s, affected develop-ments in marital cohorts, resulting in small, temporary fluctuations in the process.Regional variations in marriage patterns, however, to some extent were deter-mined by religious denominations.9 Catholics, showing a nuptiality behavior thatdeviated from Protestants, mainly lived in two provinces in the south of the Nether-lands. As graph 1 shows, in 1930, in the middle of the period of national fertilitydecline, the provinces of Limburg and Noord-Brabant had an almost homoge-neous Catholic population while consisting of Catholics for 93.5% and 88.6%respectively – rates that did not differ much with those in other years.10 The averageage at first marriage and the proportion married in these provinces differed from,for example, that in Drenthe, the Dutch province with the highest percentage ofmembers of the Dutch Reformed Church (63.7% in 1930, see graph 1), of which inthis province a large proportion was of the liberal kind.11 Nuptiality in the Catholicprovinces also differed from that in Noord-Holland. That province not only count-ed mainly liberal branches of the Dutch Reformed Church but, compared to otherprovinces, also had the highest proportion of people indicating not to belong to any

denominations and demography: historiography and methodology 17

6 Frans van Poppel, Trouwen in Nederland: een historisch-demografische studie van de 19e envroeg-20e eeuw (Wageningen 1992) 21.7 Ibid, 21-23.8 Ibid, 29-117.9 Ibid, 272.10 In the province of Limburg, the population consisted of 97.7% Catholics in 1869;98.1% in 1899; 93.5% in 1930 and 94.4% in 1960. In Noord-Brabant, these percentageswere 88.0 in 1869; 87.9 in 1899; 88.6 in 1930 and 89.0 in 1960. Erik Beekink, OnnoBoonstra, Theo Engelen en Hans Knippenburg (ed.), Nederland in verandering: maatschappe-lijke ontwikkelingen in kaart gebracht 1800-2000 (Amsterdam 2003) 62.11 For the geographical distribution of liberal branches of the Dutch Reformed Church, seeKnippenberg (1999) 110-111. In the province of Drenthe, members of the Dutch ReformedChurch constituted 81.8% of the population in 1869; 75.5% in 1899; 63.6% in 1930 and55.8% in 1960. Historische Databank Nederlandse Gemeenten (HDNG), public database oncd-rom included with Beekink, Boonstra, Engelen and Knippenburg (2003).

denomination. The proportion inhabitants without a denomination increasedfrom 4.5% in 1899 and 28.5% in 1930 (see graph 1) to reach 37.7% in 1960.12

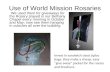

Graph 1 Average proportion Catholics, members of the Dutch Reformed Church, citizens without reli-

gious denomination and other denominations among provincial populations, 1930. Source:

HDNG.

Regional diversity in faith not only affected marital ages and rates but also leftits mark on the Dutch fertility pattern. The late onset of the fertility decline and itslanguid development to a large extent were caused by the exceptional birth rates ofthe two Catholic provinces. In Limburg and Noord-Brabant, two provinces in thesouth of the Netherlands, marital fertility rates commenced to decline severaldecades after they had started to fall in the rest of the country – and kept the natio-nal average high. Moreover, in Limburg and Noord-Brabant birth rates remainedhigher than in any other province, at least up to the 1970s. Graph 2 shows thedevelopment of marital fertility in the provinces of Noord-Holland, Drenthe,Noord-Brabant and Limburg and the national average of all eleven provinces.

18 mixing ovaries and rosaries

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Groninge

n

Friesla

nd

Drenth

e

Overij

ssel

Gelder

land

Utrech

t

Noord-H

olland

Zuid-Holl

and

Zeelan

d

Noord-B

raban

t

Limburg

Prop

ortio

npe

rpro

vinc

e

Roman Catholic Church Dutch Reformed Chuch no religious denomination other denomination

12 At the time of the 1869 census there was no category for people who did not belong toany denomination. Only from 1977 onwards a distinction was made between the denomina-tion to which a person counted him or herself and the regularity of church visits (at leastonce a month). HDNG, see footnote 11.

As graph 2 proves, the marital fertility rates of Limburg and Noord-Brabantlagged behind the national average – only after 1900 the fertility decline in the twoCatholic provinces showed a downward trend. In the mainly liberal Protestantprovince of Drenthe, marital fertility in 1875 was much lower than the Dutch aver-age and continued to decrease gradually throughout the twentieth century. From1945 onwards, marital fertility in Drenthe completely corresponded with the natio-nal average. In the fast secularizing province Noord-Holland, marital fertility divedunder the national average in the 1880s and remained much lower during themajor part of the twentieth century. Compared to Drenthe and Noord-Holland, fer-tility in the Catholic provinces remained strikingly high throughout the major partof the period of national fertility decline.

Graph 2 Dutch marital fertility rates 1876-1975: births per 1000 married women (aged 15-45).

Source: Hofstee (1981) 132.

At the end of the fertility decline, the balance between the provincial fertility rateschanged completely. During the early 1970s, Limburg and Noord-Brabant, theCatholic provinces that had been notorious for their high marital fertility ratesthroughout the nineteenth and twentieth century, had rates below those ofDrenthe and Noord-Holland. Between 1971 and 1975, Drenthe counted 117 birthsper 1000 women; Noord-Holland 105 and Noord-Brabant 111 (like the nationalDutch average). The province of Limburg had the lowest marital fertility rate ofonly 95 births per 1000 married women. During the first decades of the twentiethcentury, the national fertility decline, then, not only brought to light the mostextreme demographic differences between Catholic and Protestant regions but

denominations and demography: historiography and methodology 19

75

125

175

225

275

325

375

425

1876

-80

1881

-85

1886

-90

189

1-9

5

189

6-1

90

0

190

1-0

5

190

6-1

0

1911

-15

1916

-20

1921

-25

1926

-30

1931

-35

1936

-40

1941

-45

1946

-50

1951

-55

1956

-60

196

1-6

5

196

6-7

0

1971

-75

Num

ber

ofbi

rths

per

100

0m

arri

edw

omen

(age

d15

-45)

Noord-Holland Drenthe Noord-Brabant Limburg Netherlands

also witnessed first the total convergence, and later on even the inversion, of thedemographic differences between these denominations in the Netherlands.

Elaborating on the fertility decline in the Netherlands is one thing – but howshould the concept of religion that, apparently, affected its development, be stud-ied in a demographic research? The Dutch social scientist Peter van Rooden fromthe University of Amsterdam distinguished two aspects of religion. The first oneis personal: religion to a greater or lesser extent has a moral influence on humanbeings. This angle concerns the field of research of social scientists specializing indevelopments on a micro scale, like anthropologists and psychologists. Accordingto Van Rooden, historians working with religion should focus on its second, socialaspect: the influence of religion in the society.13 As Van Rooden separated religionon micro and macro level, a historian interested in both the personal and thesocial aspect of religion requires a different approach to the concept. “In our natio-nal history, religion is not only a phenomenon of the consciousness, but also partof the social order,” three prominent Dutch sociologists of religion from Nij-megen University Albert Felling, Jan Peters and Osmund Schreuder stated in ajoint publication, suggesting a less stringent division between religion on a microand macro level.14 In his dissertation on illegitimacy in one of the Dutch provincesduring the nineteenth century, the socio-economic historian Jan Kok from theInternational Institute of Social History (iisg) in Amsterdam refrained from dis-tinguishing between the functioning of religion on different levels altogether. Hedepicted religion as a social force among others, like economic and demographicdevelopments, that works equally on all levels of society.15 Apparently, various dif-ferent views and propositions on the study of religion offer an approach toresearch on the influence of religion on Catholic demography in the Netherlands.Before investigating the way Dutch demographic historians have dealt with theconcept of religion as a determinant of fertility behavior, especially among Catho-lics, a particular part of the international historiography will be discussed. Dealingwith an island where Catholics occupy both a majority and minority position,Irish demographic historians more than their colleagues abroad have had theopportunity to study the influence of religion in the context of other factors deter-mining demographic behavior. How did the Irish approach Catholic religion indemographic research?

20 mixing ovaries and rosaries

13 Peter van Rooden, Religieuze regimes:over godsdienst en maatschappij in Nederland 1570-1990 (Amsterdam 1996) 13-14.14 Albert Felling, Jan Peters and Osmund Schreuder, Geloven en leven. Een nationaal onder-zoek naar de invloed van religieuze overtuigingen (Zeist 1986) 7.15 Jan Kok, Langs verboden wegen: de achtergronden van buitenechtelijke geboorten in Noord-Holland 1812-1914 (Hilversum 1991) 5.

2 Ireland and the religious determinants of fertility

The reconstruction of religious determinants in the demographic history ofIreland deserves particular attention. Irish scientists working in the field mighthave faced the same difficulties with methods and theoretical frameworks as theircolleagues elsewhere – but the context in which they performed their research, wasdifferent. The topic of the influence of Catholicism on reproduction had, and per-haps still has, a distinctive political edge. The fertility of the Catholic population ofthe island has been part of an opposition against the British occupation. Duringthe last decades, high fertility levels of the Catholics have been regarded as one ofthe weapons against Northern Ireland’s joining of Britain. Apart from politics, thesocio-economic changes of the last years accelerated the demographic transitionsin the Republic. In particular Ireland’s entry into the European Economic Com-munity in 1973 and the welfare increase that followed had considerable impact onthe development of the Irish fertility and nuptiality. Despite these changes, theRoman Catholic Church maintained its social and political authority and still in-fluenced policymaking and decisions concerning the legal system – much unlikeits position in Northern Ireland. The political situation of and socio-economicchanges in the Republic and Northern Ireland both before and after the 1970s havedrawn attention of historians to the demographic heterogeneity of Irish Catholicsin the north and south. The historiography that was the result not only showed thecomplexity but also the importance of the study of the religious determinant of fer-tility and nuptiality behavior.

2.1 Demographic disparities and the conflict in Northern Ireland

The press coverage of the conflict in Northern Ireland has made it evident thatthe two disputing communities involved feel they have distinctly different nation-alities. Whether portrayed as a fight for the dominion of the geographical area oras the struggle of the Catholic minority for rights that the Protestants haverefused them for decades, few reports and analyses of the conflict have given evi-dence of its demographic aspect. Much to the surprise of P.A. Compton, a geog-rapher from Belfast, who discussed it in his 1976 article ‘Religious affiliation anddemographic variability in Northern Ireland’.16 “If the Roman Catholic popula-tion were a small and declining minority as are Protestants in the Irish Republic,the extremes of nationalism in Ulster would in all likelihood be a more manage-able phenomenon”, Compton believed. The implications of demographic con-trasts between the conflicting groups in Northern Ireland were even more com-

denominations and demography: historiography and methodology 21

16 P.A. Compton, ‘Religious affiliation and demographic variability in Northern Ireland’,Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, New Series 1 (1976) 433-452.

plicated than in terms of majority in numbers only. The Catholics’ larger familiesalso played a role in finding appropriate housing and employment. “A lower birthrate,” Compton suggested, “would also mean a lower rate of emigration and sohelp prevent the social disruption caused by the breakup and uprooting of thefamilies.”17

During the twentieth century, only a third of the Northern Irish population wasCatholic. As census data show, Roman Catholics constituted 34.8% of the North-ern Irish population in 1901. During the 1950s and 60s the proportion Catholicsslowly rose to 36.8% in 1971, due to Catholic reproduction rates.18 In 1961, thecrude birth rate of Northern Irish Catholics was estimated to be 28.3 per 1000against 19.5 among Protestants in the region.19 In spite of a high age at first mar-riage and a very high level of permanent celibacy, the rate of reported extramaritalchildbearing in Ireland remained low up to the 1970s.20 During the 1970s, theoverall fertility disparity between the two denominations narrowed as the crudebirth rates of the Catholics declined with 9% and that of the Protestants with 7%.However, by 1971 Catholic fertility was still some 50% higher than that of Protes-tants in Northern Ireland when measured in terms of total fertility rates.21 For theCatholic community, this demographic disparity stimulated its hope for unifica-tion with Ireland whereas for the Protestants it was a cause for fear of the futureratios.

For decades, the growth of the Catholic population in Northern Ireland wasrestrained by their mass emigration.22 The Catholic Irish that left Northern Irelanddid not constitute a representative part of the population. In the middle of the nine-teenth century, 70% of the emigrants were clustered in the age group 16-34.23 Emi-gration of biologically reproductive citizens, therefore, must have had a negativeeffect on the Irish birth rate. Emigration also affected nuptiality in Ireland: it mighthave resulted in the postponement or even cancellation of marriages and threw sex

22 mixing ovaries and rosaries

17 Ibid, 433.18 In reality the proportion of Catholics might have been bigger because of those not stat-ing their religion in the census. Ibid, 436.19 Ibid.20 The marital fertility rate is estimated to have accounted for at least 96% of all births inIreland in each intercensal period from 1871 to 1961. Robert Kennedy, The Irish: emigration,marriage and fertility (Berkeley 1975) 174.21 Compton (1976) 436-438.22 Timothy Guinnane, The vanishing Irish: household, migration and the rural economy inIreland, 1850-1914 (Princeton 1997) and R.C. Geary and J.G. Hughes, ‘Migration betweenNorthern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland’, Brendan M. Walsh (ed.), Religion and demo-graphic behaviour in Ireland (Dublin 1970).23 Joel Mokyr and Cormac Ó Gráda, ‘New developments in Irish Population History,1700-1850’, The Economic History Review, New Series 37 (1984) 473-488, 487.

ratios off balance.24 Hence, if it weren’t for the high emigration rates, Catholic fer-tility in Northern Ireland would have been even higher during most of the twenti-eth century.

In the 1960s, Catholics in Northern Ireland suddenly joined the European fer-tility decline. Marital fertility fell with a dazzling speed of 18% from 241 in 1961 to198 per 1000 Catholic women aged 15 to 49 in 1971. Among Protestants, the ratesdeclined less sharply, with 12% from 126 per 1000 women in 1961 to 110 in 1971.During the same period, nuptiality increased: among Catholic women of the agegroup 20-24 for example it rose over 8% (from 32.1% in 1961 to 40.3% in 1971).The proportion married among the Protestant population group increased too,though less drastically with 5.7% from 44.5% to 50.2%. In other age groups, Catho-lics showed a stronger rise in the proportion married than Protestants too.25 Ob-viously, the Irish, and particularly the Catholics among them, experienced the sec-ond phase of the demographic transition later than other parts of Western Europe– but at a much higher speed.

The Ulster Pregnancy Advisory Association, a Belfast based organization thathas been assisting women in obtaining a legally induced abortion, mirrored thefast pace of the fertility decline among Catholics in Northern Ireland in the 1960sand 70s. In the early 1960’s, Ireland still had the highest fertility rates of the wholeof Europe.26 From its foundation in 1970 onwards, the Ulster Pregnancy AdvisoryAssociation witnessed a continuously rising percentage of Catholic women amongits clients.27 Two-fifths of these women were using some form of contraceptive,which, according to Compton, was not strikingly lower than among Protestants atthe time.28

Compton failed to explain why one section of the Northern Irish populationdelayed the transition from a high to a low fertility rate for so long. In every so-cio-economic group the average size of Catholic families was significantly largerthan that of Protestants, Compton deduced. Discrepancies in socio-economicstructure of the population groups, hence, can only partly account for the differ-ence in fertility behavior between Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland.Rather then socio-economic causes, Compton surmised the demographic varia-

denominations and demography: historiography and methodology 23

24 Shipping lists from the usa in the middle of the nineteenth century showed uneven sexratios: the ratio of males to females aged 15-34 was 58.6 to 41.4 in Boston and 57.6 to 42.4 inNew York. Compton (1976) 487.25 Ibid, 438-439.26 Kennedy (1975), Coale and Treadway (1986).27 In 1999, the Ulster Pregnancy Advisory Association in Belfast had to close after anti-abortion campaigns. bbc, ‘Campaigners force pregnancy centre closure’ (August 5, 1999).Retrieved January, 26, 2005 from http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/413184.stm28 Compton (1976) 442 and R.S. Rose, An outline of fertility control, focusing on the elementof abortion, in the Republic of Ireland to 1976 (Stockholm 1976).

tions to arrive from “disparities in the practice of family limitation”. Cultural andpolitical values among the Catholic population group, the author believed, in thismatter might be just as important as “the specific normative structure of theirChurch”. Blaming the lack of in-depth studies on “the awareness, attitudes andpractice of family planning” by Northern Irish women, Compton remained indis-tinct with regard to the determinants of Catholic fertility.29

2.2 Catholic demographic behavior and the Irish border

If it weren’t for the partition of the island, Catholics would form the majority of thepopulation in Northern Ireland. In Ireland as a whole, Catholics constituted three-quarters of the population by the 1970s. The partition of 1921 divided the islandinto a Republic with an almost completely Catholic population (94% in 1971) andthe Northern part in which Catholics were a minority (approximately 38% ofthe 1971 population).30 Using the 1971 Census Fertility Reports, John Coward, lec-turer in Geography at the New University of Ulster, in his 1980 article focused hisattention on the differences between Catholic fertility in Northern Ireland and theRepublic.

Following on Compton’s results, Coward found that the fertility rates in thesouth of Ireland were much higher than in most other Western European Coun-tries.31 As in Northern Ireland, marital fertility among Catholics appeared to beextraordinarily high and the proportion married among members of this denomi-nation was lower than among non-Catholics in the Republic. In both parts of theisland, nuptiality increased and marital fertility declined between 1961 and 1971.The drop in Northern Ireland, however, began from a much higher level – in 1961the index of marital fertility was 0.70 and by 1971 only 0.55. For that reason the fer-tility decline in the north, according to Coward, was much more important than inthe south, where marital fertility index dropped ‘only’ from 0.63 to 0.56.32 In 1961,

24 mixing ovaries and rosaries

29 Compton (1976) 441.30 John Coward, ‘Recent Characteristics of Roman Catholic Fertility in Northern andSouthern Ireland’, Population Studies 34 (1980) 31-44, 32.31 Coward compared the index of 1971 marital fertility and proportions married of North-ern Ireland (0.42 and 0.63 respectively) with those of the Republic (0.56 and 0.51 respec-tively) and for example England and Wales (0.26 and 0.71 respectively), Belgium (0.25 and0.70 respectively) and the Netherlands (0.28 and 0.67 respectively). Ibid, 34 (table 1).32 Ibid, 35. Coward derived the data from Ansley Coale who for his indices used threeyearly averages of births around each census and took into account births to women inreproductive ages, differences in age structure within the 15-49 age group and the separatecontributions of marital fertility and proportions married to overall fertility. Ansley Coale,‘The decline of fertility in Europe from the French Revolution to World War Two’, SamuelBehrman, Leslie Corsa and Ronald Freedman (ed.), Fertility and family planning: a world view(Ann Arbor 1969) 3-24.

Coward continued, the “reluctance” among women in Northern Ireland to limittheir fertility was mainly found among women over 30 years old – whereas in thesouth women younger than 30 were less inclined to practice birth control.33 Adecade later, this disparity in age-specific fertility had almost completely vanished.From 1971 onwards, the crude birth rates in both Northern Ireland and the Repub-lic declined, in the former though at a higher pace than in the latter.34 Nuptiality, onthe other hand, was higher among Catholics in Northern Ireland and their familiesremained slightly bigger than in the south both in 1961 and 1971. Demographicdifferences, like variations in duration of marriage, age of the wife at marriage, lev-els of childlessness or even occupation of the husband, failed to completely explainthis continued difference.35

After having determined to what extent fertility and nuptiality differed amongCatholics in Northern Ireland and the Republic, Coward tried to find an explana-tion for his results. Did the apparent similarity of the post-1961 declining maritalfertility rates and increasing nuptiality in the north and the south of the island con-ceal different origins for the demographic changes, the author wondered. For one,Coward stated, the influence of the Roman Catholic Church had been particularlystrong in both countries: its persistent opposition against artificial forms of birthcontrol “undoubtedly” contributed to the high levels of marital fertility amongstCatholics both north and south of the border. Contrasting social-economic circum-stances in Northern Ireland and the Republic contributed to the characteristic fer-tility decline. But the similarities between the north and south, like high employ-ment in agriculture, low urbanization rates and high emigration rates, were morestriking than the differences, according to Coward.36

In his attempt to explain the slightly higher marital fertility among Catholics inNorthern Ireland, Coward seriously considered their minority status. One of thepossible links, he suggested, was that “Roman Catholics in Northern Ireland arestrongly drawn towards their Church as a means of security and identity and thustend to conform more closely to the Church’s teaching on family life.”37 On top ofthis Coward added a strong awareness of minority status, sentiments with regardto political underrepresentation and discrimination in housing and employment.The high degree of residential segregation by religion in Northern Ireland mightwell have stimulated the adherence to communal, Catholic norms too. After all,Coward argued, Catholics in Northern Ireland have lived within the confines oftheir own denomination for decades.

denominations and demography: historiography and methodology 25

33 Ibid, 35-36.34 In the Republic of Ireland, the crude birth rate had fallen from 22.7 in 1971 to 21.6 in1975, in Northern Ireland from 20.7 in 1971 to 17.1 in 1976. Ibid, 36.35 Ibid, 37-39.36 Ibid, 40.37 Ibid, 41.

If indeed minority status stimulated fertility, something must have changedeither with regard to the Northern Irish Catholic identity, the emigration rates orthe economic situation of the north – because between 1961 and 1971 fertility inNorthern Ireland declined even more dramatically than in the Republic. In fact,Coward stated, while the influence of the Roman Catholic Church remainedstrong in Ireland, “indications of changing attitudes to family life” became evidentin the 1970s when popular aversion towards the ban on advertisement and sell ofcontraceptives increased.38 Besides the growing disloyalty to the morals of theRoman Catholic Church, Coward pointed to the falling rates of emigration andagricultural employment between 1961 and 1971.

Coward concluded that the fertility decline must be understood in changing so-cio-economic structures of the Northern Irish Catholic population. The fact that heleft the subject of the relation between the Catholics’ minority status and their fer-tility behavior was most regrettable. During the period Coward wrote his article,tensions between the religious communities in Northern Ireland only increased.In spite of socio-economic changes, awareness of minority status apparently hadnot altogether disappeared among Catholics in the north. Moreover, in the Repub-lic of Ireland the Roman Catholic Church continued to interfere with matters oflegislation and education. If socio-economic developments after 1961 in only adecade brought about a transformation of the fertility pattern, where does thatleave the Catholic nature of the demographic features?

2.3 Evaluating two decades of Irish demographic variety

Both with regard to politics and historiography, little seems to have changed in thetwo decades after Compton’s article was published. The conflict between Catholicsand Protestants in Northern Ireland continued. In historiography, no stock had beentaken of the importance of the religious, economic and social determinants of fer-tility and nuptiality, of which some remained controversial.39 The two elapseddecades, however, did provide Cormac Ó Gráda and Brendan Walsh, both from thedepartment of Economics of the University College in Dublin, with data.40 In their1995 article the authors were able to test various hypotheses using data from bothNorthern Ireland and the Republic, supplied by the census of 1991.

Since 1961, the shares of the denominations in the population of the Republicof Ireland have changed. This trend started in 1911 and was caused by emigration,low fertility rates and mixed marriages.41 As a result, the proportion of Catholics in

26 mixing ovaries and rosaries

38 Ibid, 43.39 Mokyr and Ó Gráda (1984) 488.40 Ó Gráda and Walsh (1995) 259-279.41 In mixed marriages in the Republic, children with only one Protestant parent were usu-ally raised as Catholics. Ibid, 263.

the Republic increased from 90% in 1911 to 95% in 1961 – until the census of1961 when it became possible to indicate not to have a religion or leave the matter‘not stated’.42 Based on the 1981 census, Ó Gráda and Walsh confirmed the con-vergence of Catholic and Protestant fertility patterns in the Republic, as noted byCompton: “much of the substantial gap in fertility between Catholics and othershad been eliminated among those who had married in the 1970s.”43 The authorsadded that the difference in migration rates between the two population groupsstarted to change at that time too: from the 1960s and 1970s onwards, Protestantsinstead of Catholics were the ones that were more likely to leave the Republic ofIreland.

As Ó Gráda and Walsh showed, the data of the 1981 and 1991 census in North-ern Ireland deviated from those of the Republic on several points. Although thepopulation in the north of the island hardly increased, it showed a dynamic patternon a regional level. Moreover, the Catholics’ share in the population increased sur-prisingly – it rose from 31% in 1971 to over 38% in 1991 – even to 42% if respon-dents who did not state their religion (but mainly lived in Catholic regions), areincluded.44 Not only population numbers, but also birth rates changed in NorthernIreland, as marital fertility declined and general fertility showed an even biggerdrop – particularly among Catholics.45 Nonetheless, by 1991 Catholic fertility stillwas significantly higher than that of Protestants: in 1971 the marital fertility of thetwo populations in the north was in the proportion of 173 to 100, in 1991 of 142 to100.46 Demographic differences between Catholics and Protestants remained farmore “interesting” than those between the various Protestant denominations.47

Interestingly enough, the 1981 and 1991 data contradict the suggested conver-gence of Catholic and Protestant demographic behavior – at least where it con-cerned Northern Ireland. “Only in a few districts in the Belfast suburbs has Catho-lic fertility converged to Protestant levels during the last two decades, while in anequal number of areas the difference actually widened over the period,” Ó Grádaand Walsh stated.48 In Northern Ireland, religion still appeared to determine repro-duction: Catholic fertility rates dropped most heavily in regions outside the tradi-tional denominational ‘ghettoes’. The Protestants in Northern Ireland, however,were not only “bred out”, as Ian Paisley said; their majority in numbers was threat-

denominations and demography: historiography and methodology 27

42 Ibid, 262.43 Ibid, 263.44 Ibid, 269.45 Cormac Ó Gráda, ‘New evidence on the fertility transition in Ireland 1880-1911’, Demog-raphy 28 (1991) 535-548.46 Cormac Ó Gráda and Brendan Walsh (1995) 266.47 Presbyterian women in Northern Ireland showed a slightly lower fertility than femalemembers of the Church of England. Ibid, 270.48 Ibid, 266-268.

ened by a declining emigration among Catholics too: “there can be little doubt thatCatholics were less likely to leave than others during the 1970s and 1980s.”49

In 1991, even the fertility rates of cities like Dublin and Cork in the Republicwere still below those with the lowest fertility rates in Northern Ireland, illustratingthe continuous difference between Catholic fertility in Northern Ireland and theRepublic. Nevertheless, Ó Gráda and Walsh showed, the demographic differencesbetween Catholics and Protestants in both parts of the island remained more strik-ing and could not be explained by socio-economic factors only. “Detailed compari-sons controlling for social class,” Ó Gráda and Walsh stated, “showed that a mark-ed Catholic/Protestant differential existed on both sides of the Irish political bor-der in 1961.”50 And although the difference declined between 1971 and 1991, theresearch of Ó Gráda and Walsh showed that the differences between Catholics andProtestants in Northern Ireland remained significant. In that sense, the border be-tween Northern Ireland and the Republic might be misleading for existing differ-ences between demographic: Catholic determinants of fertility behavior appearedto be much stronger than those characteristic of the region.

2.4 Irish demographic historiography: a case of absent Catholicism

Compton and Coward as well as Ó Gráda and Walsh showed that even during thelate 1980s, Irish Catholics and Protestants had different attitudes regarding familysize. When region or socio-economic background were controlled for, the differ-ences did not disappear. “Catholic religiosity or ‘culture’ remains the best explan-ation for the gap,” Ó Gráda and Walsh concluded their article.51 In this matter, notall Catholics on the island seemed to behave the same – Northern Irish Catholicsappeared less enthusiastic to limit their family size than their fellow believers inthe Republic.

Whilst the authors optimally utilized census data and carefully indicated theirlimits in order to precisely map the context of Catholic fertility in Northern Irelandand the Republic, it remained obscure how the influence of religion on Catholicfertility came about. Ireland is famous for the powerful social position of theRoman Catholic Church.52 But how did the Church use its position in the socio-political arena to organize interference with demographic issues? What local so-cial, political or economic circumstances motivated a community to obey or ignore

28 mixing ovaries and rosaries

49 Ibid, 273.50 Ibid, 277.51 Ibid, 278.52 David Miller, Church, state and nation in Ireland 1898-1921 (Dublin 1971), DermotKeogh, Ireland and the Vatican: the politics and diplomacy of church-state relations, 1922-1960(Cork 1995) and Maaike den Draak and Inge Hutter, Fertility in the Irish Republic: nurtured byIrish law and the Catholic church (Groningen 1996).

Church directives with regard to reproduction? What did the Church actually haveto say to its flock about sexuality and procreation and what methods did it use toimpose fertility behavior on individuals? In a country where religious affiliationapparently usually implied a radical political orientation, how could Catholicismcontinue to appeal to a code of conduct for procreation?

The Irish case demonstrated the importance and consequences of the effect ofreligion on demographic behavior. Scholars working on the subject sometimes didnot even manage to impartially report the differences between Catholic and Prot-estant demography. Compton in 1976 for example referred to the high Catholicbirth rate as the “demographic irritant” and the cause of social inequality betweenProtestants and Catholics.53 The historiography of Catholicism as determinant ofIrish fertility has proven that religion, like economy, can influence fertility behav-ior. The next paragraph will show that, with that conclusion, the trouble has justbegun.

3 Revisiting the matter of religion and demography: Kevin McQuillan

Ireland is not the only country where fertility of Catholics converged with those ofother denominations. In many other industrialized societies, differences be-tween Catholic demographic characteristics and those of other denominationshave eased during the last decades of the twentieth century. Unfortunately, thisresulted in a decline of enthusiasm for the subject among demographers anddemographic historians. Unjustly so; during the 1980s and 90s, studies thatwere part of the ‘Princeton Project’, short for the ‘European Fertility Project’ fromPrinceton University in the usa, offered a new perspective on cultural factorsbehind the fertility transition.54 Kevin McQuillan from the Department of Sociol-ogy of the University of Western Ontario in Canada in 1999 published a study ondemographic behavior in Alsace that was motivated by the same kind of interestfor cultural circumstances that, besides social and economic factors, pressed fer-tility and nuptiality developments.55 In 2004 this publication was followed by anevaluation of three decades of research on religious affiliation as a determinant ofdemographic behavior. McQuillan wished to seize the opportunity to “revisit thequestion of religion and fertility in the light of a generation of new theoretical and

denominations and demography: historiography and methodology 29

53 Compton (1976) 451.54 Barbara Anderson, ‘Regional and cultural factors in the decline of marital fertility inEurope’, Coale and Watkins (1986) 293-313 and Ron Lesthaeghe and Chris Wilson, ‘Modesof production, secularization and the pace of the fertility decline in Western Europe, 1870-1930’, Coale and Watkins (1986) 261-292.55 Kevin McQuillan, Culture, religion and demographic behavior: Catholics and Lutherans inAlsace, 1750-1870 (Montreal and Kingston 1999).

empirical work”.56 The resulting article put forward convincing suggestionsabout the way religious determinants of demography should be approached inresearch.

3.1 Goldscheider’s propositions

While discussing the most important theoretical approaches to the relationshipbetween religion and demography, McQuillan starts off with Calvin Gold-scheider’s 1971 publication of Population, Modernization and Social Structure.57

Goldscheider, who worked as a sociologist at the University of California, Berkeleyin the usa, divided demographers, attempting to explain the influence of religionon demography, into two groups. The first category concerned scholars who main-tained a “characteristics proposition”, hypothesizing that “the distinct fertility ofreligious subgroups merely reflects a matrix of social, demographic, and economicattributes that characterizes the religious subgroup.”58 According to Goldscheider,these scholars regarded denominational affiliation as an indication of social classand degree of social mobility. Membership of a certain religious group, thisapproach held true, is not significant but the implied social, demographic and eco-nomic characteristics determine deviating demographic trends. Fertility differ-ences between religious groups, therefore, were of a temporary nature according tothis approach and represented a social or cultural gap. The fallacy of this approach,Goldscheider argued, was that it regarded religion, religious affiliation and reli-gious institutions as independent factors – while in reality they have become inex-tricably bound up with other (economic, political) components of society. More-over, the ‘characteristics approach’ failed because even while controlling for vari-ables like education and income, socio-economic factors could not completelyaccount for the religious determinants of demography – as Irish historiographyhas illustrated.

The second approach to demographic contrasts between denominations didnot meet with Goldscheider’s approval either. The ‘particularized theology’ propo-sition implied that “the impact of religion on fertility behavior and attitudes oper-ates with particular church doctrine or religious ideology on birth control, contra-ceptive usage, and norms of family size”.59 According to this point of view, reli-gious ideology affected variables that in their turn shaped fertility levels. Thishypothesis, Goldscheider wrote, did not come up to the mark at all. “It is analogousto explaining the unique voting or political behavior of Catholics in terms of spe-

30 mixing ovaries and rosaries

56 Kevin McQuillan, ‘When does religion influence fertility?’, Population and developmentreview 30 (2004) 25-56, 25.57 Calvin Goldscheider, Population, Modernization and Social Structure (Boston 1971).58 Ibid, 272.59 Ibid.

cific church norms with respect to voting or political behavior”. Distinctionsbetween fertility of, for example, Irish and Italian Catholics in the usa cannot beexplained by “specific commitments of these ethnic subgroups to the family sizeand contraceptive norms of the church”, but rather to the “integration of thesegroups into the institutionalized Catholic structure”, their “assimilation-accultura-tion patterns” and the “more general social and cultural milieu” of the Catholicsubgroup in the usa.60 While studying determinants of Catholic behavior, scholarshad to include not only denominational teachings on fertility control but the wholecontent of the social organization of a denomination, Goldscheider argued. Addi-tionally, the social status of a religious group had to be taken into account. A minor-ity status with accompanying social and economic barriers would stimulate a re-duction of fertility, Goldscheider continued – a statement that was refuted by theNorthern Irish Catholics who, in spite of their minority status, for decades did notseem to be inclined to limit the number of their children. Notwithstanding hisharsh words with regard to the ‘particularized theology’ approach, Goldscheiderattached great importance to religion as “the most common although not the onlymanifestation of value orientations”. Religion, according to this sociologist, has re-mained “a vigorous and influential institution in modern, secularized, economiclydeveloped, educated, industrialized societies” touching the very core of socialbehavior, attitudes and values.61

3.2 The curriculum of the demographic historian

Like Goldscheider, McQuillan in his 2004 article stressed the role of religiousnorms: “religions have elaborated moral codes that are meant to guide humanbehavior and,” he continued, “many of the great religious traditions have givenspecial attention to issues of sexuality, the roles of men and women, and the placeof the family in society.”62 McQuillan however managed to supplement his plea forthe importance of denomination-specific norms with relevant instructions fordemographers who stumble across a religious variable while studying determi-nants of demography.

McQuillan advocated distinguishing two types of religious values: first thedirectives that are quite specific in regulating behavior “that is directly connected tothe proximate determinants of fertility”, and, secondly, broader norms that have amore indirect influence on fertility.63 During the last centuries, the Roman Catho-lic Church stood out among other religions and denominations in unconditionally

denominations and demography: historiography and methodology 31

60 Ibid, 293.61 Ibid, 270.62 McQuillan (2004) 27.63 Ibid.

repudiating almost all means of contraception and abortus provocatus.64 But,McQuillan underlined, religions like Catholicism have designed other directivesstimulating or restraining fertility than just those regarding the use of contracep-tion and the practice of abortion. Among these are conditions under which one isallowed to form a sexual union: the minimal age, the number of spouses, andwhether or not one is allowed to marry again after divorce or widowhood. More-over, McQuillan argued, religious prohibitions regarding sexual activity outsidethe officially recognized unions are important – illustrative is the negative connota-tion unmarried motherhood still has in many industrialized, secularized coun-tries. Rules regarding sexual matters within wedlock have been part of a denomin-ation’s impact on fertility too: in Catholicism these directives include for examplethe fact that partners are not allowed to refuse their spouse sexual gratification.

McQuillan’s second category of religious directives that affect demographyconcern broader norms that have a more indirect impact on fertility behavior.Interest in this category of church regulations is in line with Goldscheider’s advicefor demographic historians to study the social organizations of the religions andtheir possible impact on fertility rather than their dogma’s. However, McQuillan’selaboration on this approach has given considerable space to a broad interpretationof the category: he referred to “values that speak directly to issues of fertility, al-though they do not involve specific rules about practices of fertility regulation”.65

Among these indirect religious influences on fertility are the division of gender-specific tasks between men and women and the eulogium of the family as the soci-ety’s ‘cornerstone’ – values that were detached from their religious base and havebecome social institutions on their own.

As Goldscheider described, many scholars first try to explain demographiccharacteristics of a religious group with its socio-economic characteristics. Onlywhen they’re absolutely sure that some part of a demographic profile remains reli-giously determined, they turn to religious teachings to explain the discrepancies intheir statistics. McQuillan agreed with Goldscheider that conjuring dogma out ofthe demographic hat in this way is too shallow. In addition, he proposed to switcharound the method of research and start off with religious directives regardingdemographic behavior, “because fertility differentials among religious groups thatare not tied in to variations in their religious beliefs are likely to be the result of dif-ferences in their socio-economic situation, and thus do not constitute examples ofa true religious effect”. Religious determinants of fertility form the net result of a

32 mixing ovaries and rosaries

64 John Noonan, Contraception: a history of its treatment by the Catholic theologians andcanonists (Cambridge 1965) 387-438, Barbara Brooks, Abortion in England 1900-1967 (Lon-don 1988), Hanneke Westhoff, Natuurlijk geboorteregelen in de twintigste eeuw: de ontwikkelingvan de periodieke onthouding door de Nederlandse arts J.N.J. Smulders in de jaren dertig (Baarn1986) 34-42.65 McQuillan (2004) 29.

sum, of which denominational directives are but one element – yet a distinct, inevi-table component. McQuillan hence added another task to the curriculum of thereligiously challenged demographic historian. Not only the elements of religiousdirectives that may control fertility should be identified, but also pathways had tobe traced that, as McQuillan formulated it, “lead from these values to the proximatedeterminants of fertility”.66

3.3 The Church’s pathways to regulating behavior

The example of Ireland has shown that Catholics north and south of the Irish bor-der may share a faith, but not all demographic characteristics. The differencesbetween Catholics in Ireland and France, of which certain regions are regarded asthe leaders in the European fertility decline, are bigger still.67 A religious institu-tion’s success in imposing rules of behavior onto believers, McQuillan stated, com-pletely depended on the means required to get the directives to the believers and onthe development of “mechanisms to promote compliance and punish noncon-formity.”68