CASE REPORT Miniscrew-assisted nonsurgical palatal expansion before orthognathic surgery for a patient with severe mandibular prognathism Kee-Joon Lee, a Young-Chel Park, b Joo-Young Park, c and Woo-Sang Hwang c Seoul, Korea A transverse maxillary deficiency in an adult is a challenging problem, especially when it is combined with a se- vere anteroposterior jaw discrepancy. The demand for nonsurgical maxillary expansion might increase as pa- tients and clinicians try to avoid a 2-stage surgical procedure—surgically assisted rapid palatal expansion followed by orthognathic surgery—and detrimental periodontal effects and relapse. In this regard, a mini- screw-assisted rapid palatal expansion was devised and used to treat a 20-year-old patient who had severe transverse discrepancy and mandibular prognathism. Sufficient maxillary orthopedic expansion with minimal tipping of the buccal segment was achieved preoperatively, and orthognathic surgery corrected the antero- posterior discrepancy. The periodontal soundness and short-term stability of the maxillary expansion were confirmed both clinically and radiologically. Effective incorporation of orthodontic miniscrews for transverse correction might help eliminate the need for some surgical procedures in patients with complex craniofacial discrepancies by securing the safety and stability of the treatment, assuming that the suture is still patent. (Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2010;137:830-9) T ransverse maxillary deficiency is a relatively common clinical problem. It has been reported that 9.4% of whole populations and nearly 30% of adult orthodontic patients have a maxillary transverse deficiency related to a posterior crossbite. 1,2 Although rapid palatal expansion (RPE) has been a reliable treatment modality in prepubertal patients, there have been controversies regarding nonsurgical expansion in adults. 3 Surgically assisted RPE (SARPE) has been the treatment of choice to resolve the high re- sistance from the bony palate and the zygomatic but- tress, 4 in contrast to reports of successful nonsurgical expansion in young adults. 5,6 The difficulties in dealing with the transverse discrepancy are associated with the limited range of tooth movement in the transverse dimension, described by Proffit et al 2 as the ‘‘transverse envelope of discrepancy.’’ Maxillary constriction combined with severe anteroposterior discrepancy is challenging, because it usually requires 2 surgeries: SARPE followed by or- thognathic surgery. Since many patients are reluctant to undergo multiple surgical procedures, the demand for nonsurgical treatment might increase. However, even though nonsurgical palatal expansion is feasible, ample orthopedic expansion of the basal bone rather than dentoalveolar tipping is essential to prevent detri- mental periodontal effects such as bony dehiscence and to establish proper posterior occlusion. 7 In this re- gard, the appliance should be designed appropriately to maximize the skeletal effects. Since conventional rapid palatal expanders that are either tooth-borne (hyrax type) or tooth-and-tissue- borne (Haas type) cause questionable effects on the basal bone, a rigid element that delivers the expansion force directly to the basal bone could be a solution. For this purpose, a miniscrew-assisted rapid palatal ex- pander (MARPE) was designed and used in an adult pa- tient. This case report shows the treatment effects and stability of the MARPE in a patient with severe maxil- lary constriction and mandibular prognathism. DIAGNOSIS A 20-year-old man had severe mandibular progna- thism. His past medical and dental histories were not From the College of Dentistry, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea. a Assistant professor, Department of Orthodontics, Oral Science Research Center, Institute of Craniofacial Deformity. b Professor, Department of Orthodontics. c Resident, Department of Orthodontics. Supported by the 2006 research fund of the Institute of Craniofacial Deformity, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea. The authors report no commercial, property, or financial interest in the products or companies described in this article. Reprint request to: Kee-Joon Lee, Department of Orthodontics, College of Dentistry, Yonsei University, 134 Shinchon-dong Seodaemun-gu, Seoul, Korea 120-752; e-mail, [email protected]. Submitted, September 2007; revised and accepted, October 2007. 0889-5406/$36.00 Copyright Ó 2010 by the American Association of Orthodontists. doi:10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.10.065 830

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

CASE REPORT

Miniscrew-assisted nonsurgical palatalexpansion before orthognathic surgery fora patient with severe mandibular prognathism

Kee-Joon Lee,a Young-Chel Park,b Joo-Young Park,c and Woo-Sang Hwangc

Seoul, Korea

A transverse maxillary deficiency in an adult is a challenging problem, especially when it is combined with a se-vere anteroposterior jaw discrepancy. The demand for nonsurgical maxillary expansion might increase as pa-tients and clinicians try to avoid a 2-stage surgical procedure—surgically assisted rapid palatal expansionfollowed by orthognathic surgery—and detrimental periodontal effects and relapse. In this regard, a mini-screw-assisted rapid palatal expansion was devised and used to treat a 20-year-old patient who had severetransverse discrepancy and mandibular prognathism. Sufficient maxillary orthopedic expansion with minimaltipping of the buccal segment was achieved preoperatively, and orthognathic surgery corrected the antero-posterior discrepancy. The periodontal soundness and short-term stability of the maxillary expansion wereconfirmed both clinically and radiologically. Effective incorporation of orthodontic miniscrews for transversecorrection might help eliminate the need for some surgical procedures in patients with complex craniofacialdiscrepancies by securing the safety and stability of the treatment, assuming that the suture is still patent.(Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2010;137:830-9)

Transverse maxillary deficiency is a relativelycommon clinical problem. It has been reportedthat 9.4% of whole populations and nearly

30% of adult orthodontic patients have a maxillarytransverse deficiency related to a posterior crossbite.1,2

Although rapid palatal expansion (RPE) has beena reliable treatment modality in prepubertal patients,there have been controversies regarding nonsurgicalexpansion in adults.3 Surgically assisted RPE (SARPE)has been the treatment of choice to resolve the high re-sistance from the bony palate and the zygomatic but-tress,4 in contrast to reports of successful nonsurgicalexpansion in young adults.5,6 The difficulties indealing with the transverse discrepancy are associatedwith the limited range of tooth movement in the

From the College of Dentistry, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea.aAssistant professor, Department of Orthodontics, Oral Science Research

Center, Institute of Craniofacial Deformity.bProfessor, Department of Orthodontics.cResident, Department of Orthodontics.

Supported by the 2006 research fund of the Institute of Craniofacial Deformity,

Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea.

The authors report no commercial, property, or financial interest in the products

or companies described in this article.

Reprint request to: Kee-Joon Lee, Department of Orthodontics, College of

Dentistry, Yonsei University, 134 Shinchon-dong Seodaemun-gu, Seoul, Korea

120-752; e-mail, [email protected].

Submitted, September 2007; revised and accepted, October 2007.

0889-5406/$36.00

Copyright � 2010 by the American Association of Orthodontists.

doi:10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.10.065

830

transverse dimension, described by Proffit et al2 as the‘‘transverse envelope of discrepancy.’’

Maxillary constriction combined with severeanteroposterior discrepancy is challenging, because itusually requires 2 surgeries: SARPE followed by or-thognathic surgery. Since many patients are reluctantto undergo multiple surgical procedures, the demandfor nonsurgical treatment might increase. However,even though nonsurgical palatal expansion is feasible,ample orthopedic expansion of the basal bone ratherthan dentoalveolar tipping is essential to prevent detri-mental periodontal effects such as bony dehiscenceand to establish proper posterior occlusion.7 In this re-gard, the appliance should be designed appropriatelyto maximize the skeletal effects.

Since conventional rapid palatal expanders that areeither tooth-borne (hyrax type) or tooth-and-tissue-borne (Haas type) cause questionable effects on thebasal bone, a rigid element that delivers the expansionforce directly to the basal bone could be a solution.For this purpose, a miniscrew-assisted rapid palatal ex-pander (MARPE) was designed and used in an adult pa-tient. This case report shows the treatment effects andstability of the MARPE in a patient with severe maxil-lary constriction and mandibular prognathism.

DIAGNOSIS

A 20-year-old man had severe mandibular progna-thism. His past medical and dental histories were not

Fig 1. Pretreatment facial photographs.

Fig 2. Pretreatment intraoral views showing severe transverse and anteroposterior jaw discrepancy.

American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics Lee et al 831Volume 137, Number 6

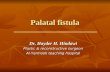

remarkable. Initial intraoral and extraoral views shiweda severe Class III malocclusion and a concave profilewith a protrusive mandible and a retrusive maxilla(Fig 1). The severe bilateral buccal crossbite was asso-ciated with relative constriction of the maxilla (Fig 2).The crossbite remained when the casts were reposi-tioned to a Class I molar relationship, indicating an ab-solute transverse deficiency.8 Maxillary and mandibularintermolar widths were 42.0 and 44.5 mm, respectively,indicating that about 8 mm of maxillary expansion wasneeded to establish proper buccal occlusion. Excessivebuccal tipping of the maxillary second molars wasalso noted. Incisor overbite was 14.5 mm, and overjetwas –7.0 mm (Fig 3).

The initial lateral cephalometric analysis showeda severe anteroposteior discrepancy with an ANB of–9.0�, SNA of 82.9�, and SNB of 91.9�, and dental

compensation represented by U1 to SN of 117.0� andIMPA of 74.0�. The Wits appraisal was –20.5 mm. TheSN-MP angle was relatively low (28.7�) (Fig 4, Table).

From the posteroanterior (PA) cephalometric analy-sis, the maxillary basal bone width measurement was66.8 mm, and interantegonial notch width was 96.0mm, with resultant a maxillomandibular differential of29.2 mm (Table).

TREATMENT OBJECTIVES

The treatment objectives were to (1) correct themaxillary deficiency with sufficient maxillary expan-sion, (2) maintain sound periodontal support in themaxillary arch throughout treatment, (3) establish anesthetic profile with maxillomandibular orthognathicsurgery, and (4) establish proper buccal occlusion.

Fig 3. Pretreatment casts.

Fig 4. Pretreatment x-rays (lateral cephalogram andpanoramic x-ray).

832 Lee et al American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics

June 2010

TREATMENT ALTERNATIVES

Because of the severe anteroposterior jaw relation-ship, orthognathic surgery was inevitable. Accordingly,several treatment options were suggested to deal withthe transverse discrepancies.

A SARPE before orthognathic surgery can be a reli-able treatment option. Because of the severe maxillo-mandibular discrepancy and the midface deficiency,2-jaw surgery with a LeFort I osteotomy was indicated.However, since SARPE and maxillary LeFort I osteot-omy cannot be performed simultaneously, the patientwould require 2 stages of surgery. The possibleincreases in surgical trauma and costs were concerns.

Maxillary segmental osteotomy for bilateral expan-sion of the maxillary posterior segments with the man-dibular surgery was also considered to correct both thetransverse and anteroposterior skeletal discrepancies in1 surgery. However, lateral movements of the maxillarysegment have been shown to be considerably unstable.9

Extraction of the maxillary premolars can be a solu-tion to reduce the relative discrepancy between the max-illary and mandibular buccal segments, since it resultsin a full-step Class II molar relationship. In this patient,however, the transverse discrepancy at the molar widthwas still there when the diagnostic casts were reposi-tioned in a Class II relationship. Furthermore, incisor re-traction would have prolonged the overall treatment.The increase in the negative overjet after maxillary

Table. Cephalometric analysis before and after treatment

Measurements Mean T0 T1 T2

Lateral cephalogram

SNA (�) 81 82.9 82.9 84.5

SNB (�) 78 91.9 92.0 83.0

ANB (�) 3 –9.0 –9.1 1.5

Wits (mm) –2 –20.5 –19.5 –4.5

SN-GoGn (�) 35 28.7 29.7 37.7

U1 to SN (�) 106 116.4 111.4 106.5

L1 to GoGn (�) 94 74.0 80.0 80.1

Upper lip to E-line (mm) 1 –8.8 –8.3 –0.2

Lower lip to E-line (mm) 2 2.5 3.5 2.0

PA cephalogram

Nasal cavity width (mm) NA 66.8 69.0 68.4

Maxillary basal bone width (mm) NA 34.0 36.5 36.0

T0, Initial; T1, before orthognathic surgery at 10 months; T2, final at

16 months; NA, not applicable.

American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics Lee et al 833Volume 137, Number 6

incisor retraction would then necessitate excessive sur-gical jaw movement that could be detrimental for thestability of the surgery.

Sufficient orthopedic expansion of the maxilla couldeliminate the need for invasive surgery, if appropriatelyperformed. However, in this patient, maximum skeletalexpansion without severe dental tipping and undesiredperiodontal side effects would be necessary, and the re-sults would need to be stable after treatment. Specialconsiderations were needed in designing the appliancefor nonsurgical expansion.

TREATMENT PROGRESS

A MARPE was fabricated with some modificationof the conventional RPE. An impression was madewith the bands on the first premolars and first molars,and a conventional hyrax expander was constructed onthe cast. Four rigid connectors of stainless steel wirewith helical hooks were soldered on the base of hyraxscrew body. Two anterior hooks were positioned onthe rugae region, and the other 2 posterior hooks wereplaced on the parasagittal area (Fig 5, A). The hookswere adjusted for passive contact with the underlyingtissues. The MARPE was then placed and cementedon the patient’s first premolars and molars. Orthodonticminiscrews (Orlus, Ortholution, Seoul, Korea) witha 1.8-mm collar diameter and a 7-mm length wereplaced in the center of the helical hooks under local in-filtration anesthesia. The wires were adjusted to main-tain passive contact with the collar of the miniscrews.Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were prescribedfor pain control (Fig 5, B).

The hyrax screws were turned once a day starting thenext day. Separation of the midpalatal suture was con-

firmed with intraoral radiographs and a PA cephalogram(Figs 5-7). The miniscrews were maintained in place withno notable positional change throughout the expansionphase. Expansion was terminated at 6 weeks, resultingin an 8.3-mm increase in intermolar width. After activeexpansion, the MARPE was maintained for 3 monthsto allow bone formation in the separated palatal suture.The buccolingual molar inclination did not change afterexpansion and alignment (Fig 8). Transitional soft-tissue inflammation around the miniscrews in the poste-rior palate occurred during expansion but subsided afterremoval of the appliance. The maxillary second molaraxis was corrected by applying elastic chains to the hooksattached to the molar bands.

The transverse increases were 2.4 mm in maxillarybasal bone width and 2.5 mm in nasal width, respec-tively (Fig 7, Table).

Complete arch alignment and coordination wereperformed for the orthognathic surgery. At 10 months,a 2-jaw orthognathic surgery was performed involvinga maxillary LeFort I osteotomy for posterior impactionand advancement and mandibular setback by 18.0 mmwith bilateral vertical ramus osteotomies (Fig 9).

Occlusal settling was performed with vertical elas-tics. All brackets and bands were removed after 16months of treatment (Figs 10-12). Fixed retainerswere attached on the maxillary and mandibularanterior teeth. A maxillary circumferential retainerwas also used to secure the stability of the expandedmaxillary arch.

There was no remarkable change in the clinicalcrown heights at debonding compared with the initialstatus. There was no notable gingival recession orbony dehiscence in the posterior segments.

Stable posterior occlusion was maintained for 18months after debonding. Gingival recession or attach-ment loss was not remarkable compared with the initialstatus at 18 months after debonding (Fig 13, A-E). Anaxial computed tomogram was taken 12 months afterdebonding to view the periodontal status of the maxil-lary buccal segment. An axial section at 3 mm fromthe proximal cementoenamel junction showed soundperiodontal surroundings in both the anterior and poste-rior regions around the roots (Fig 13, F).

TREATMENT RESULTS

Adequate nonsurgical bodily expansion of the max-illary buccal segments was achieved. Desirable buccalsegment occlusion was established. The patient hadsound and stable periodontal support after expansionand completion of treatment. Balanced facial estheticsresulted from the orthognathic surgery.

Fig 5. Fabrication and application of the MARPE: A, fabrication on the cast; B-D, placement of theappliance and expansion procedure for 6 weeks; E, after consolidation and arch alignment at 10months.

Fig 6. Periapical views during maxillary expansion: A, before expansion; B, after 4 weeks of expan-sion, with the upper diastema temporarily closed by resin buildup for esthetic reasons; C, afterconsolidation and arch alignment at 6 months.

834 Lee et al American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics

June 2010

DISCUSSION

It has been a general perception that the predictabil-ity of orthopedic expansion is greatly reduced after 15years of age, when SARPE may have to be used.3,10

However, the validity of surgical or nonsurgicaltreatment should be reexamined in terms of feasibility,safety, and stability.

Early histologic studies showed that palatal sutureobliteration or synostosis begins when people are intheir thirties, and fusion of facial sutures is rare in olderskulls, unlike the cranial sutures,11-15 which were

confirmed by Knaup et al,16 who claimed that bony fu-sion in the midpalatal suture was rare in subjects under25 years. These findings substantiate anecdotal case re-ports in which conventional RPE produced successfulorthopedic effects.5

Nevertheless, a recent study showed that nonsurgi-cal expansion even in prepubertal patients leads to thin-ning of the buccal alveolar wall, which could developa bony dehiscence.17 This effect was more evident in pa-tients with tooth-borne expanders than tooth-and-tissue-borne expanders. This demonstrates the increased risksof transverse expansion in postpubertal patients, in

Fig 7. PA cephalograms: A, before expansion; B, after expansion; C, superimposition.

Fig 8. Changes in arch width and molar inclination: A, occlusal molds made of pattern resin (GC, To-kyo, Japan) with wire for standardized measurement of the molar inclination; B-E, changes in molarwidth and inclination before and after expansion.

American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics Lee et al 835Volume 137, Number 6

whom stronger bone-borne anchorage is needed thanconventional expanders. Taken together, the maximumskeletal effect during and after expansion is a crucialfactor whether the expansion is surgical or nonsurgical.

Although surgical osteotomies obviously allowmaxillary skeletal expansion in adults, there have beencontroversial opinions about the stability of the archwidth. Phillips et al9 reported considerable relapse afterexpansion with LeFort I and segmental osteotomy in 39patients. SARPE, therefore, was expected to show supe-rior stability compared with segmental osteotomy, sinceit allows tissue adaptation during the expansion andsubsequent consolidation period. However, an empiricalcomparison between SARPE and nonsurgical expan-

sion has been difficult, mainly because of the problemsin designing a controlled experiment between age-matched groups.18,19 Berger et al20 stated that the1-year stability of SARPE in postpubertal subjects wasnot significantly different from that of nonsurgical ex-pansion in prepubertal patients. Therefore, it can bespeculated that the treatment effects and the stabilityof nonsurgical expansion in adults are comparablewith those of SARPE, when the orthopedic expansionis secured.

Diagnostic criteria for surgical intervention havebeen suggested in several ways. Handelman et al6 statedthat surgically assisted expansion should be used whenthe required expansion of intermolar width exceeds 8

Fig 9. Treatment progress: A-C, after expansion at 6 weeks; D-F, before orthognathic surgery; G-I,after orthognathic surgery.

Fig 10. Posttreatment facial photographs.

836 Lee et al American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics

June 2010

mm. Betts et al21 suggested the maxillomandibularwidth differential measured from the PAview, as a guidefor surgical expansion. According to those criteria, ourpatient would need 2-stage surgery. However, Baileyet al18 favored simultaneous segmental osteotomy andmandibular surgery over 2-stage surgery in long-facepatients with narrow maxillae, due to surgical trauma,morbidity, and cost. Thus, nonsurgical expansion maybe justified when it leads to treatment effects similar tothose of SARPE.

MARPE is a simple modification of the conven-tional RPE appliance; the main difference is the incor-poration of several miniscrews to ensure expansion ofthe underlying basal bone and maintain the separatedbones during the consolidation period. Posterior minis-crews were placed close to the midpalatal suture to usethe bone thickness of the nasal crest.22,23 The treatmenteffects in this case can be defined as a combination ofskeletal and dentoalveolar expansion, since theappliance is tooth-and-bone-borne. The literature shows

Fig 11. Posttreatment casts.

Fig 12. Posttreatment x-rays and cephalometric superimposition.

American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics Lee et al 837Volume 137, Number 6

Fig 13. A-E, Follow-up intraoral photographs18 months after debonding; F, axial computed tomo-gram showing the 3-mm apical level from the cementoenamel junction 12 months after debonding.

838 Lee et al American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics

June 2010

that considerable dentoalveolar expansion also occurredwith SARPE,24 and the amount of expansion at the max-illary basal bone was not as much as the dentoalveolarexpansion.25 A triangular expansion represented bygreater dentoalveolar expansion with less basal bone ex-pansion seems unavoidable because of the anatomicstructure and the appliance design, whether the expan-sion is surgical or nonsurgical.

Some bone-borne maxillary expanders have beenproposed in reports to facilitate the skeletal expansionfollowing lateral osteotomies.26-28 In contrast, ourtooth-and-bone-borne appliance required a simple proce-dure for miniscrew placement and definitely did not needan osteotomy, implying that an effective replacement ofSARPE with MARPE in young adults may be possible.

In spite of our promising clinical results, theMARPE appliance cannot be expected to force the sep-aration of obliterated sutures in older adults. Therefore,the indications for MARPE should be confined to youngadults from the late teens to the midtwenties, based onthe earlier studies.11,29 SARPE can still be a treatmentof choice for older patients.18 The primary objectiveof the appliance is to gain maximum skeletal effectsin the patent sutures but not necessarily in the obliter-ated sutures. Possible mechanical resistance from thecircummaxillary sutures could be another limiting fac-tor even when the suture is patent.4 Because of the var-iations in suture development and the complexity ofcraniofacial structures, a prospective study needs to beconducted to evaluate the reliability of this appliancein adults compared with growing children.

CONCLUSIONS

This case report introduced an RPE reinforced byorthodontic miniscrews (MARPE) positioned on thepalatal bone. It demonstrated the clinical effects in treat-ing a young adult with severe maxillary constriction andmandibular prognathism. To avoid multiple surgeries,nonsurgical maxillary expansion was performed withthe MARPE to achieve both skeletal and dentoalveolarexpansion for transverse correction. Subsequent orthog-nathic surgery corrected the mandibular prognathismand vertical excess. The stability of the expansion andthe periodontal status were favorable from the follow-up clinical and radiologic findings. This report proposeseffective incorporation of orthodontic miniscrews fortransverse correction; this can eliminate the need formultiple surgeries in patients with complex craniofacialdiscrepancies and secure the safety and stability of thetransverse correction.

REFERENCES

1. Brunelle JA, Bhat M, Lipton JA. Prevalence and distribution of se-

lected occlusal characteristics in the US population, 1988-1991.

J Dent Res 1996;75(Spec No):706-13.

2. Proffit WR, Phillips C, Dann CT. Who seeks surgical-

orthodontic treatment? Int J Adult Orthod Orthognath Surg

1990;5:153-60.

3. Melsen B. Palatal growth studied on human autopsy material. A

histologic microradiographic study. Am J Orthod 1975;68:

42-54.

4. Shetty V, Caridad JM, Caputo AA, Chaconas SJ. Biomechanical

rationale for surgical-orthodontic expansion of the adult maxilla.

J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1994;52:742-9.

American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics Lee et al 839Volume 137, Number 6

5. Stuart DA, Wiltshire WA. Rapid palatal expansion in the young

adult: time for a paradigm shift? J Can Dent Assoc 2003;69:

374-7.

6. Handelman CS, Wang L, BeGole EA, Haas AJ. Nonsurgical rapid

maxillary expansion in adults: report on 47 cases using the Haas

expander. Angle Orthod 2000;70:129-44.

7. Thilander B, Nyman S, Karring T, Magnusson I. Bone regenera-

tion in alveolar bone dehiscences related to orthodontic tooth

movements. Eur J Orthod 1983;5:105-14.

8. Jacobs JD, Bell WH, Williams CE, Kennedy JW 3rd. Control of

the transverse dimension with surgery and orthodontics. Am J

Orthod 1980;77:284-306.

9. Phillips C, Medland WH, Fields HW Jr, Proffit WR, White RP Jr.

Stability of surgical maxillary expansion. Int J Adult Orthod

Orthognath Surg 1992;7:139-46.

10. Baccetti T, Franchi L, Cameron CG, McNamara JA Jr. Treatment

timing for rapid maxillary expansion. Angle Orthod 2001;71:

343-50.

11. Miroue M, Rosenberg L. The human facial sutures: a morphologic

and histologic study of age changes from 20 to 95 years [thesis].

Seattle: University of Washington; 1975.

12. Brandt HC, Shapiro PA, Kokich VG. Experimental and postexper-

imental effects of posteriorly directed extraoral traction in adult

Macaca fascicularis. Am J Orthod 1979;75:301-17.

13. Jackson GW, Kokich VG, Shapiro PA. Experimental and postex-

perimental response to anteriorly directed extraoral force in young

Macaca nemestrina. Am J Orthod 1979;75:318-33.

14. Cohen MM Jr. Transforming growth factor beta s and fibroblast

growth factors and their receptors: role in sutural biology and

craniosynostosis. J Bone Miner Res 1997;12:322-31.

15. Kokich VG. Age changes in the human frontozygomatic suture

from 20 to 95 years. Am J Orthod 1976;69:411-30.

16. Knaup B, Yildizhan F, Wehrbein H. Age-related changes in the

midpalatal suture. A histomorphometric study. J Orofac Orthop

2004;65:467-74.

17. Garib DG, Henriques JF, Janson G, de Freitas MR, Fernandes AY.

Periodontal effects of rapid maxillary expansion with tooth-

tissue-borne and tooth-borne expanders: a computed tomography

evaluation. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2006;129:749-58.

18. Bailey LJ, White RP Jr, Proffit WR, Turvey TA. Segmental LeFort

I osteotomy for management of transverse maxillary deficiency.

J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1997;55:728-31.

19. Koudstaal MJ, Poort LJ, van der Wal KG, Wolvius EB, Prahl-

Andersen B, Schulten AJ. Surgically assisted rapid maxillary ex-

pansion (SARME): a review of the literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac

Surg 2005;34:709-14.

20. Berger JL, Pangrazio-Kulbersh V, Borgula T, Kaczynski R. Stabil-

ity of orthopedic and surgically assisted rapid palatal expansion

over time. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1998;114:638-45.

21. Betts NJ, Vanarsdall RL, Barber HD, Higgins-Barber K,

Fonseca RJ. Diagnosis and treatment of transverse maxillary

deficiency. Int J Adult Orthod Orthognath Surg 1995;10:75-96.

22. Kyung S. A study on the bone thickness of midpalatal suture area

for miniscrew insertion. Korean J Orthod 2004;34:63-70.

23. Wehrbein H, Merz BR, Diedrich P. Palatal bone support for

orthodontic implant anchorage—a clinical and radiological study.

Eur J Orthod 1999;21:65-70.

24. Chung CH, Goldman AM. Dental tipping and rotation immedi-

ately after surgically assisted rapid palatal expansion. Eur J

Orthod 2003;25:353-8.

25. Altug Atac AT, Karasu HA, Aytac D. Surgically assisted rapid

maxillary expansion compared with orthopedic rapid maxillary

expansion. Angle Orthod 2006;76:353-9.

26. Harzer W, Schneider M, Gedrange T, Tausche E. Direct bone

placement of the hyrax fixation screw for surgically assisted rapid

palatal expansion (SARPE). J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2006;64:

1313-7.

27. Tausche E, Hansen L, Hietschold V, Lagravere MO, Harzer W.

Three-dimensional evaluation of surgically assisted implant

bone-borne rapid maxillary expansion: a pilot study. Am J Orthod

Dentofacial Orthop 2007;131(Suppl):S92-9.

28. Ramieri GA, Spada MC, Austa M, Bianchi SD, Berrone S. Trans-

verse maxillary distraction with a bone-anchored appliance:

dento-periodontal effects and clinical and radiological results.

Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2005;34:357-63.

29. Wehrbein H, Yildizhan F. The mid-palatal suture in young adults.

A radiological-histological investigation. Eur J Orthod 2001;23:

105-14.

Related Documents