Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

EAST ASIAHISTORY, POLITICS, SOCIOLOGY, CULTURE

Edited by

Edward BeauchampUniversity of Hawai‘i

A ROUTLEDGE SERIES

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page i

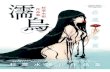

PITFALL OR PANACEA

The Irony of US Power in OccupiedJapan, 1945–1952Yoneyuki Sugita

THE RENAISSANCE OF TAKEFU

How People and the Local PastChanged the Civic Life of a RegionalJapanese TownGuven Peter Witteveen

MANAGING TRANSITIONS

The Chinese Communist Party, UnitedFront Work, Corporatism, andHegemonyGerry Groot

THE PROSPECTS FOR A REGIONAL HUMAN

RIGHTS MECHANISM IN EAST ASIA

Hidetoshi Hashimoto

AMERICAN WOMEN MISSIONARIES AT

KOBE COLLEGE, 1873–1909New Dimensions in GenderNoriko Kawamura Ishii

A PATH TOWARD GENDER EQUALITY

State Feminism in JapanYoshie Kobayashi

POSTSOCIALIST CINEMA IN POST-MAO

CHINA

The Cultural Revolution after theCultural RevolutionChris Berry

BUILDING CULTURAL NATIONALISM IN

MALAYSIA

Identity, Representation, andCitizenshipTimothy P. Daniels

LIBERAL RIGHTS AND POLITICAL CULTURE

Envisioning Democracy in ChinaZhenghuan Zhou

THE ORIGINS OF LEFT-WING CINEMA IN

CHINA, 1932–37Vivian Shen

MAKING A MARKET ECONOMY

The Institutional Transformation of a Freshwater Fishery in a ChineseCommunityNing Wang

GLOBAL MEDIA

The Television Revolution in AsiaJames D. White

ACCOMMODATING THE CHINESE

The American Hospital in China,1880–1920Michelle Renshaw

INDONESIAN EDUCATION

Teachers, Schools, and CentralBureaucracyChristopher Bjork

BUDDHISM, WAR, AND NATIONALISM

Chinese Monks in the Struggle againstJapanese Aggressions, 1931–1945Xue Yu

COOPERATION OVER CONFLICT

The Women’s Movement and the Statein Postwar JapanMiriam Murase

“WE ARE NOT GARBAGE!”The Homeless Movement in Tokyo,1994–2002Miki Hasegawa

EAST ASIAHISTORY, POLITICS, SOCIOLOGY, CULTURE

EDWARD BEAUCHAMP, General Editor

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page ii

“WE ARE NOT GARBAGE!”The Homeless Movement in Tokyo, 1994–2002

Miki Hasegawa

RoutledgeNew York & London

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page iii

Published in 2006 byRoutledge Taylor & Francis Group 270 Madison AvenueNew York, NY 10016

Published in Great Britain byRoutledge Taylor & Francis Group2 Park SquareMilton Park, AbingdonOxon OX14 4RN

© 2006 by Taylor & Francis Group, LLCRoutledge is an imprint of Taylor & Francis Group

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

International Standard Book Number-10: 0-415-97693-6 (Hardcover) International Standard Book Number-13: 978-0-415-97693-0 (Hardcover) Library of Congress Card Number 2006004798

No part of this book may be reprinted, reproduced, transmitted, or utilized in any form by any electronic,mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying, microfilming, andrecording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the publishers.

Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used onlyfor identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hasegawa, Miki."We are not garbage!" : the homeless movement in Tokyo, 1994-2002 / Miki Hasegawa.

p. cm. -- (East Asia)Includes bibliographical references and index.ISBN 0-415-97693-61. Homelessness--Japan--Tokyo--History. 2. Homeless persons--Civil

rights--Japan--Tokyo--History. 3. Homeless persons--Japan--Tokyo--Political activity--History. 4. Shinjuku Coalition--History. I. Title. II. East Asia (New York, N.Y.)

HV4607.T65H37 2006305.5'692095213509049--dc22 2006004798

Visit the Taylor & Francis Web site at http://www.taylorandfrancis.com

and the Routledge Web site at http://www.routledge-ny.com

Taylor & Francis Group is the Academic Division of Informa plc.

RT6936X_Discl.fm Page 1 Thursday, March 30, 2006 2:01 PM

v

Contents

List of Acronyms vii

List of Maps ix

Acknowledgments xi

Chapter OneIntroduction 1

Chapter TwoHomelessness in Postwar Japan 23

Chapter ThreeTheoretical Framework and Hypotheses 53

Chapter FourThe Initial Period of the Movement(February 1994–January 1996) 69

Chapter FiveThe Transitional Period of the Movement(January 1996–October 1997) 97

Chapter SixThe Final Period of the Movement (October 1997–mid-2002)with Summary and Conclusions 117

Appendix ADefining and Counting the Homeless (in the U.S. and Japan) 147

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page v

Appendix BList of Surveys Used in the Study 149

Appendix CInterviews 157

Appendix DChronology of Homeless Policy (in Tokyo and Japan) 159

Notes 165

Bibliography 181

Index 205

vi Contents

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page vi

List of Acronyms

DPJ Democratic Party of Japan

GHQ General Headquarters of the Allied Occupation

JR Japan Railways

LDP Liberal Democratic Party

ME micro electronics

NPO Non-profit organization

QC quality control

RM resource mobilization

SMO social movement organization

SWG Shinjuku Ward Government

TMG Tokyo Metropolitan Government

vii

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page vii

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page viii

List of Maps

Figure 1. Map of Central Tokyo 2

Figure 2. Map of Japan 8

Figure 3. Map of Shinjuku 72

ix

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page ix

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page x

Acknowledgments

This book is an outgrowth of the dissertation that I wrote at ColumbiaUniversity. Numerous people helped me with the thesis and research onwhich it was based. I first thank my dissertation committee members. MaryRuggie, sponsor, closely checked drafts of the thesis, and Francesca Pol-letta, chair, guided me on concepts and interpretation of research findings.Charles Tilly, whom I contacted for membership in the committee onlyafter I knew what I was writing, helped me with literature. I also appreciatehis advice on how to become a professional researcher.

Bruce Link and Brendan O’Flaherty offered technical and substantivesuggestions that made the dissertation fuller than otherwise possible. In thisbook, I tried to incorporate their advice in ways that I was unable to whenI wrote the thesis, although I am solely responsible for the contents.

In Japan, between 1998 and 2000, the Institute of Social Science atthe University of Tokyo allowed me to use its facilities as a visitingresearcher. Access to one of the best university library systems in the coun-try facilitated my research. From 1998 to 2001, the Institute also hired meas a research assistant—an appointment that financially supported myfieldwork. I thank Masako Watanabe at the International Research Centerfor Japanese Studies for connecting me to the Institute. I also thank TsuneoAyabe, a professor emeritus at the University of Tsukuba, for connectingme to Shôgo Koyano, a former president of the Japan Sociological Society.Koyano introduced key yoseba researchers to me; eventually, MitsutoshiNakane, Tom Gill, Keiko Yamaguchi, Yukihiko Kitagawa, and othersoffered me important writings on yoseba and homelessness, including theirown.

In the field, the non-homeless activist who appears as Harada in thisbook took time to explain movement events as they took place. Like manyhomeless persons who knew him, I appreciated his straightforward character

xi

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page xi

as well as sense of humor, in addition to the substantive help in the field. Ialso thank Nanae Ôgai, an enthusiastic volunteer in West Shinjuku, forinforming me of developments in the locale when I had to temporarilyexcuse myself from the field for work or illness.

Outside the field, Tarô and Keiko Hasegawa, my parents, saved forme every newspaper article and TV program on homelessness that theycould find. Jun’ichi, my brother, gave me an opportunity to lecture onhomelessness in Japan at Obirin University where he teaches. It made mefeel that I did something for the homeless, not only for the students. Rie,my sister, took me out for a change when I needed it, although we tended toend up in places related to research, such as the Waterfront Sub-center atTokyo Bay. Further, Norma Fuentes, Xiaodan Zhang, and other fellow stu-dents at Columbia University, as well as Kayo Nakagawa, a long-termfriend of mine who now teaches at Kochi University, assured me of thecompletion of the project when I felt unsure.

Following research, James Wright at the University of Central Floridaand anonymous reviewers gave me an opportunity to refine a portion of mydissertation for the journal American Behavioral Scientist. Chapter 2 of thebook adopts parts of my article (Hasegawa 2005) that appeared in thejournal’s special issue on “Homelessness and the Politics of Social Exclu-sion.” I thank Sage Publications for permitting me to do so.

The book became possible only because Benjamin Holtzman, editorat Routledge, found my dissertation interesting and helped me prepare thebook and because Edward Beauchamp taught me how to improve the dis-sertation for publication. I also benefited from comments on my researchfindings by members of the Japan Research Group at the Society for theAdvancement of Socio-Economics (SASE). I thank Greg Jackson, a friendof mine from Columbia University, and Yoshitaka Okada at Sophia Univer-sity, Tokyo, for letting me join the group. Further, a research team on glob-alization and lower-stratum people in Japan, sponsored by the Ministry ofEducation, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, helped me keep upwith new developments in policy, movements, and research surroundingthe issue of homelessness. I thank Akihiko Nishizawa at Toyo Universityfor allowing me into the team as a cooperator. Finally, Makoto Sugimura, agraduate student at Tokiwa University, helped me with the maps thatappear in this book.

I dedicate this book to the homeless persons who participated in myfieldwork (as well as others who would have participated if circumstanceshad allowed). Before the fieldwork, I had never participated in a movement.In one sense, we exchanged our projects. As I followed them around andjoined their activities, they introduced me to their friends for an interview,

xii Acknowledgments

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page xii

showed me around a homeless facility in which they were temporarilyhoused, and invited me to numerous informal gatherings among them. Spe-cial thanks go to Itchan, Mr. Andô, Matchan, Saitô, Ms. Asano, Ms. Horie,Ms. Kaneko, Mr. Kunogi, Mr. Sagawa, Mr. Sasaki, Mr. Sakamoto, Mr.Matsushita, Mr. Fukuda, Mr. Gotô, Kuma-san, Mr. Takahashi, and Mr.Fujimori. I wish that Japanese society allowed us to use our full (and real)names regardless of our past and current socio-economic status.

Acknowledgments xiii

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page xiii

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page xiv

Chapter One

Introduction

In February 1994, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government (TMG) evicted some150–200 homeless people in an encampment on the west side of Japan Rail-ways (JR) Shinjuku station. The station is located in Shinjuku Ward, a sub-center of Japan’s capital Tokyo.1 The ward has a daytime population of about800,000, and the station is used by nearly 1.5 million commuters a day. Soonafter the eviction, a couple of non-homeless activists’ groups came to the site,one from San’ya and the other from Shibuya, and restored the encampmentwith the remaining homeless persons. From the encampment, homeless per-sons and non-homeless activists began to demand welfare and employment,targeting the Tokyo and Shinjuku governments. Several months after the evic-tion, some of the activists and homeless settlers in the encampment officiallyformed a movement group, which I will call the Shinjuku Coalition in thisbook,2 to launch a full-scale struggle to win “public guarantee of employmentand livelihood” for all the homeless in Shinjuku.

The Coalition continued to struggle for about eight years. During theperiod, the group targeted not only the ward and metropolitan governmentsbut also the central government. Throughout the struggle, the overriding goalremained public provision of employment and welfare for all homeless people.Without achieving this goal at any level of government, however, the Coalitionfell apart and, in the summer of 2002, proclaimed that the homeless shouldtake responsibility for their own future instead of counting on the Coalition orgovernment. As of this writing, the group retains its name and, as it has donesince 1994, meets regularly in West Shinjuku to give out food and flyers tohomeless people. Yet, the main purpose of this activity is no longer to mobilizethe aggrieved for contentious action but to inform them of services that publicagencies offer. Much less often, the group also meets with public officials in aneffort to influence ongoing homeless measures, but mass participants usuallywait outside the building until a small delegate comes back with few fruits.

1

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page 1

* * *

In Tokyo, as in many other large cities in Japan, homelessness began toincrease sharply in the early 1990s. Since then, several movement groupshave formed to address homelessness in the city. The Shinjuku Coalition wasthe first among them, and the other groups were created to follow the leadof the Coalition. The Coalition was also the only movement group that suc-ceeded in citywide mobilization of the homeless. It did so by leading other,newer groups as well as another movement group that had long worked on

2 “We Are Not Garbage!”

Figure 1. Map of Central Tokyo.

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page 2

day labor. While these groups had their own local homeless constituen-cies, their mass mobilization was very limited in scale and frequency com-pared to that of the Coalition. The homeless movement in Tokyo, or thesubject of this book, emerged and developed along the activities of theShinjuku Coalition.

Yet, from the beginning to the quiescence of the movement,3 theCoalition faced a series of difficulties. Although it set out to gain publicguarantee of employment and provision of full welfare, it found itselfspending tremendous amounts of time and energy in realizing mass negoti-ations with public officials because they refused to sit down with the home-less to talk about policy. In particular, before regular talks became possiblewith TMG officials, the group had to busy itself with an anti-eviction cam-paign as the TMG threatened to dismantle the encampment in West Shin-juku. Thus, despite their centrality in the group’s raison d’etre, theCoalition was able to focus on policy matters only after mass negotiationsand survival of the encampment were assured.

Moreover, although the Coalition, upon focusing on policy issues, suc-cessfully scaled up the movement to the city level by forging an alliance withthe other movement groups in Tokyo, the alliance did not perform well. Allthe groups agreed that public guarantee of employment and full welfare wasan important goal and, as a step toward that goal, jointly sought severalhomeless shelters that the TMG had planned but suspended because of oppo-sition by ward governments. However, as the shelter campaign dragged onwithout success, the other groups became much less interested in these facili-ties. After all, it took as long as three years for the alliance to see the firstthree shelters in operation. Although the Coalition wanted to eventuallyintroduce a public employment program into these shelters, the alliance col-lapsed even before it discussed the feasibility of this idea.

When the Coalition scaled up the movement, it also lost internal soli-darity. Initially, the relations between non-homeless activists and homelesspersons were more or less equal, although the activists officially took lead-ership of the group. In a communal setting, the two parties jointly decidedwhat to do next and how, and engaged in unruly collective action to maketheir voice heard. As a result, the group made a number of gains, althoughthey were far short of the overriding goal. These relations changed, how-ever, as the leadership began to subordinate homeless persons and shiftedfrom community-based mobilization to mobilization of diffuse homelessindividuals. The leadership sometimes expelled from the group homelesspersons who did not conform to its policy. The group no longer used dis-ruptive tactics and, although it continued to make small gains, overall, theyturned out to be fewer and less universal in nature.

Introduction 3

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page 3

After the opening of the three shelters became certain, in mid-2000,the Coalition further tried to scale up the movement to the national level asthe central government had become interested in devising a national home-less policy. Yet, the leadership was unable to agree on for what to conductnational mobilization of the homeless. It split into two camps, with oneseeking a workable policy from administrators and the other, passage of acontroversial homeless assistance bill that seemed to endorse eviction. Theformer succeeded in mobilizing a number of movement groups and theirhomeless constituencies from across the country under the slogan “employ-ment and livelihood without eviction.” It was the first nationwide mobi-lization of the homeless in Japanese history. After all, however, neithercamp affected the central government in any significant way. The billpassed in mid-2002, and shortly after, the group officially became a “pres-sure group,” thereby phasing out the movement in Tokyo.

* * *

The objective of this study is to explain the emergence, trajectory, andgains of the movement in Tokyo. In particular, it concerns the followingquestions. First, how was organization of the homeless possible? Homelessindividuals are generally believed to be “unorganizable” (Rocha 1994) fora variety of reasons, including their alleged tendency to suffer apathy andlack of self-confidence and their high mobility resulting from the constantneed to find food, employment, and safe space (Snow and Anderson 1993).Even when homeless persons create an encampment to lead a more settledlife, it does not necessarily facilitate organization of the homeless. Althoughthere were in the early 1990s at least several other homeless encampmentsin central Tokyo, the movement began in West Shinjuku and not in otherplaces. Why did the movement emerge in West Shinjuku? How did non-homeless activists (and homeless persons) there succeed in organizing thehomeless?

Second, why did the Shinjuku Coalition evolve in the way it did?Despite the initial success in organizing the homeless, non-homelessactivists could not sustain solidaristic relations with the aggrieved. As themovement became routinized, the non-homeless leadership created a dualinternal structure by lowering the position of homeless participants. Therelations between the leadership and the constituency became unequal,with the former often exerting power over the latter. Relatedly, the leader-ship could not maintain communal mobilization, either. This mode ofmobilization was far more powerful than mobilization of homeless individ-uals because, in a communal setting, homeless persons, with established ties

4 “We Are Not Garbage!”

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page 4

and networks, could respond readily to action requirements in order toprotect and advance their common interests. However, the leadership aban-doned communal mobilization and resorted to mobilization of diffusehomeless individuals, settled or mobile. Why did the leadership-con-stituency relations become unequal? Why did the group shift its mode ofmobilization?

Third and finally, what accounts for movement gains? Although theShinjuku Coalition failed to win public guarantee of employment and liveli-hood for the aggrieved, between 1994 and 2002, it brought a number ofbenefits to the homeless in Shinjuku and beyond by mobilizing up to hun-dreds of homeless people at one time. For example, while the Coalitioncould not guarantee public welfare for all the needy homeless in Shinjuku,it at least made it easier for them to obtain it. Also, by mobilizing othermovement groups to stage a sit-in protest against an eviction that the TMGplanned, the group succeeded in drawing public attention to homelessnesswhen it was not yet fully recognized as a social problem, as the protest wastelevised live and reported in Japan’s major newspapers. Over time, how-ever, the number of gains declined and their substance changed from uni-versal to selective. What gains did the Coalition achieve and how? Why didthe gains change in the way they did?

The present study draws on the relational perspective of social move-ments (McAdam, Tarrow, and Tilly 2001) to answer these questions. Therelational perspective is useful for present purposes because, in contrast tothe resource mobilization (RM) and political process perspectives that pre-ceded it, it treats movements as dynamic, creative interactions amongactors, including the state. The emphasis on the interactive, creative natureof movements facilitates analysis of how non-homeless activists organizedthe homeless in West Shinjuku and how the movement in Tokyo emerged asthe two parties interacted with opponents. The treatment of the state as amovement participant is crucial in explaining the evolution of the ShinjukuCoalition, since, as I will argue in this study, state agencies, particularly atthe metropolitan level, played a decisive role in undermining solidaritybetween the non-homeless leadership and homeless people. By alteringtheir relations, the TMG also profoundly affected the Coalition’s goals, tac-tical choices and, consequently, achievements.

* * *

By tracing the history of the movement in Tokyo, I seek to draw atten-tion to recent lower-stratum movements in which challengers have beencomprised not only by the aggrieved but also by external collaborators who

Introduction 5

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page 5

are outside the political establishment. Social movement researchers havetended to assume that movements are either exogenous or endogenous totheir constituencies. A number of studies on movements among lower-stra-tum people in the past couple of decades (Cress 1993; Cress and Snow1996; Delgado 1986; Demirel 1999; Hirsch 1993; Rocha 1994; Wagnerand Cohen 1991; T. Wright 1995, 1997) indicate, however, that externalcollaborators that operate outside the polity, such as activists’ and advo-cacy groups, have been deeply involved in these movements. Along withmass participants, they have played a significant role in the emergence anddevelopment of the movements. This raises the question of whether con-ventional arguments on the rise and fall of movements apply to these mixedmovements.

The same can be said of the effectiveness of indigenous and proxymovements. Some researchers have argued that, in affluent societies, for-mal, increasingly professional movement organizations are more efficient inbringing benefits to the poor and powerless than mass-based movements.Others have maintained that, given the right opportunities and indigenousresources, the poor and powerless can mount successful movements ontheir own. While both proxy and indigenous movements can generate fruit-ful results, studies on lower-stratum mobilization in recent years suggestthat mixed movements can also generate substantial gains at least on thelocal level. The proxy-indigenous dichotomy misses these less visible gainsand leaves unanswered the question of how the aggrieved and their collab-orators produce gains. By detailing how homeless people and their exter-nally originated collaborators formed a movement, developed it, andgenerated gains along the way, the present study aims to deepen our under-standing of how mixed movements work.

THE SHINJUKU COALITION: ITS BACKGROUND ANDCHARACTERISTICS

Growth and spread of homelessness

Homelessness in Japan4 first became noticeable in and around yoseba dur-ing the 1980s. Yoseba denotes an informal day labor market (Nakane2002). Since the latter half of the 1970s, it has operated largely for the con-struction industry (ibid.). Yoseba exist, or open up, in cities across thecountry, but the largest and most institutionalized are Kamagasaki inOsaka City (Osaka Prefecture), San’ya (covering parts of Arakawa andTaito Wards) in Tokyo, Kotobuki in Yokohama City (Kanagawa Prefec-ture), and Sasajima (which is also called Sasashima) in Nagoya City (Aichi

6 “We Are Not Garbage!”

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page 6

Prefecture). The first three are embedded in flophouse quarters and areoften compared to skid row in the United States (Ezawa 2002; Gill 2001).For the yoseba day laborer, temporary homelessness was part of life sinceevery lean season meant possible or actual loss of any form of housing.During the 1980s, especially in the latter half of the decade, however, long-term homelessness began to increase among older yoseba men (K. Shima1999; Umezawa 1995).

Homelessness then started to rise sharply beyond yoseba in largecities across the country, around 1992 when a recession hit the economy(Iwata 1997a; K. Shima 1999; Tamaki 1997). In central Tokyo, the TMGcounted on one day about 460 homeless in certain public places in 1992,but the number grew to more than 1,000 by the following year (TMG1995: 11–12). In 1995, railway companies as well as the ward and metro-politan governments found a total of 3,300 people who slept in publicplaces on one day (TMG 2001: 2). In Osaka, in and around Kamagasaki,the number of homeless people rose from about 1,600 to nearly 4,000between 1994 and 1998 (K. Shima 1999: 20–22). In Yokohama, in 1995,volunteer patrollers met on one day an average of around 550 homelesson several spots around Kotobuki, but the corresponding number ofencounters exceeded 1,000 by 1999 (Gill 2001: 216). In Nagoya, anothergroup of volunteer patrollers counted in areas beyond Sasajima about200 homeless in 1991, 360 in 1992, and 550 in 1994 (Mizutani and Sug-iura 1999: 61).

The size of homelessness in Japan showed upward trends throughoutthe 1990s and, in 2003, slightly more than 25,000 people were said to besleeping rough on one day (Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry 2003: 7).5

The surge of homelessness is not without its predecessor. As I will show inChapter Two, in postwar Japan, there was another time when homelessnessspread across the country. It was immediately after World War II, and, infact, much more people experienced homelessness in the early postwaryears than in the 1990s. Moreover, sizeable homelessness remained wellinto the 1960s. The recent homeless population has differed from its earliercounterparts, however; whereas the homeless populations in the earlierperiods included a number of families, women, and children, the over-whelming majority, or at least 90 percent, of the homeless in recent yearshave been middle-aged and older single men.6

In addition, while their demographic characteristics coincide withthose of the homeless in yoseba, 40–60 percent of the recent homelesspopulation had never had contact with yoseba before they became home-less. A majority of these non-yoseba men had held regular or casual jobs ina range of industries other than construction, and, while the rest had been

Introduction 7

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page 7

construction day laborers, they were not from yoseba but from laborcamps elsewhere. In the early 2000s, an even higher rate of homelessnesswas found among non-yoseba men than in the 1990s (Health, Labor andWelfare Ministry 2003).

8 “We Are Not Garbage!”

Figure 2. Map of Japan.

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page 8

The question of why homelessness began to appear among non-yosebamen, especially among non-construction workers, will be dealt with in Chap-ter Two where I will also discuss plausible causes of the recent rise in home-lessness, but it needs to be mentioned here that this particular phenomenonsignified the shrinking capacity of yoseba to absorb downwardly mobile sin-gle men. For long, yoseba had taken in men who lost employment in variousindustries and turned them into day laborers. Over the years, however, thebuffer role of yoseba against unemployment had weakened.

As described below, the decline in the role of yoseba as an economicbuffer had a due effect on the movement communities in large yoseba.

Responses in large yoseba

Postwar yoseba have a history of labor struggle (Funamoto 1985; Imagawa1987; Kaji 1977; Kanzaki 1974; Takenaka 1969; Yamaoka 1996).Although different movement groups appeared and disappeared at differentpoints in time, the main current of ongoing activism in large yoseba wascreated in the early 1980s with the formation of the National Federation ofDay Laborers’ Leagues.7 The federation, comprised by the Kama, San’ya,Kotobuki, and Sasajima Leagues, representing the four largest yoseba, wasestablished for the purpose of spreading day laborers’ struggle across thecountry (Kazama 1993). Although yoseba struggle did not develop into anational movement, during the 1980s, the four groups, individually or incooperation, achieved considerable gains, including higher wages, elimina-tion of yakuza attacks on organized day labor, and better working condi-tions at inferior labor camps in which day labor was increasingly enclosed(Munemura 1993; Yamaoka 1996).

Around 1990, however, the core of movement activities in theseyoseba began to shift from labor struggle to relief giving and demanding.In Kamagasaki, the largest yoseba district in Japan with about 25,000day laborers at that time (Koyanagi 1991: 131), public employment andwelfare for older day laborers became the main demands of local move-ment groups (Koyanagi 1997). The Winter Struggle, or a commonannual event of movement communities in yoseba in which food, med-ical consultation and other services are offered to homeless day laborers,was rescheduled for year-round operation. In 1993, recognizing dramaticchanges occurring in the district with a sharp rise in homelessness, theKama League formed the Kama Coalition with a dozen religious groups,a couple of advocacy groups, and other concerned individuals in thelocale to seek a comprehensive national policy for Kamagasaki, empha-sizing public employment of older day laborers and community revital-ization (T. Honda 2001).

Introduction 9

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page 9

Albeit less vigorously, similar reorganization of movement activitiesoccurred in San’ya, the second largest yoseba with about 8,000 day laborersaround 1990 (Koyanagi 1991: 131). While the San’ya League continued towork on labor disputes, as a senior member of the group put it, overall, thegroup became more like “a labor and medical consultant” than an organizerof mass action (SRFK 1992). To cope with rising homelessness, some mem-bers of the San’ya League created a patrol team to reach homeless day labor-ers in and around the district on a regular basis (Kasai 1999). Previously,patrolling was a part of San’ya’s Winter Struggle, but it was now a year-roundactivity. As patrollers walked around, they offered food and other services tothe homeless on the streets. By doing so, they studied grievances among thehomeless and how they could possibly organize them (Jinmin Patorôru Han1993). Further, during the 1993–94 Winter Struggle, the San’ya League and asmall advocacy circle in the district started a “collective kitchen” to offer anopportunity for homeless men to gather in one place and build communalrelations with each other. In the midst of this Winter Struggle, the TMGevicted homeless people in West Shinjuku and patrol team members went tothe site, eventually to form the Shinjuku Coalition.

The way in which the movement community in Kotobuki, with about5,000 day laborers (Koyanagi 1991: 131), responded to homelessness wassomewhat like that of San’ya. In 1990, a medical team, which had offeredfree medical consultation during the Winter Struggle, made this serviceavailable once a month to meet the need for the service among homelesspeople as well as flophouse dwellers in and around the district (Yajima1999). In addition, in the spring of 1993, a Kotobuki patrol team, formedby a local advocacy group and the Kotobuki League, went to KawasakiCity in response to a police assault on a day laborer that occurred at JRKawasaki station. The patrol team protested against the violence and alsoinvestigated grievances among the homeless in the locale. In 1994, the teamcreated an independent group for Kawasaki and, with homeless peoplethere, began wrestling with the city government, demanding regular wel-fare, emergency aid, safety of belongings (from confiscation), and othermeasures to improve the condition of the local homeless population(Kawasaki no Nojuku Seikatsusha Yûshi to Kawasaki Suiyô Patorôru noKai 1996, 1997).

Sasajima, used by around 1,000 day laborers as of 1990 (Koyanagi1991: 132), seems unique in that welfare was not a minor issue and receivedmuch attention long before homelessness began to grow sharply in the early1990s. Because this yoseba is not located in a flophouse quarter, wheneverhomelessness increased in the previous decades, it tended to concentrate atJR Nagoya station close to the labor market. When homelessness at the

10 “We Are Not Garbage!”

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page 10

station became highly visible after the oil crisis in 1973, a movement com-munity, which includes the Sasajima League, began to develop as concernednon-homeless individuals tackled welfare and other issues among homelessday laborers (Fujii 1994; Koyanagi 1991). Reflecting this background, themost visible response in Sasajima to the unusual growth of homelessness inthe early 1990s was a lawsuit that a homeless man, with the help of a localadvocacy group, filed in 1994 against the Nagoya City Government and thelocal welfare office that failed to provide him with welfare (Fujii 1994,1997; Hayashi Soshô wo Sasaeru Kai 2002).

Formation of new groups

The growth of homelessness led not only to reorganization and reorienta-tion of the existing movement communities in yoseba districts; it also led tothe formation of new movement, advocacy, and volunteer groups thataddressed the problem, especially in the 1990s when homelessness spreadwell beyond these districts. It is hard to know exactly how many newgroups have formed (and disbanded), but an examination of available data8

suggests that there are currently at least ten dozen groups of the kinds thatoperate more or less regularly.9 Although these groups include older onesthat formed in the 1970s and 1980s, a majority of them are of new cre-ation, or began their activity in the 1990s. Geographically new groups haveencompassed large cities across Japan, from Hokkaido on the north toKyushu on the south.

While leading figures in the movement communities of large yosebahave been veteran activists and advocates, often with unionist or New Leftbackgrounds, and other individuals long concerned with issues surroundingyoseba men, new groups have been usually led by individuals with no orlimited degrees of prior association with yoseba. They include young casualworkers, members of religious organizations, university instructors and stu-dents, and full-time activists of various origins. Albeit small in number,some groups have been entirely comprised by homeless persons, with orwithout prior contact with yoseba. These indigenous groups have emergedfrom encampments and have often looked like small neighborhood associa-tions. Also, they have usually worked closely with a non-homeless group inthe locale.

Despite differences in backgrounds, new movement, advocacy, andvolunteer groups, like their older counterparts, have very often provided atleast one of the following services to the local homeless population on aregular basis: distribution of free food, patrol of places where homelessnessconcentrates, and medical referral and consultation. When these activitiesare done in combination, the group would patrol certain places, offering

Introduction 11

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page 11

food and medical consultation. Where this similarity has come from is aninteresting question. Because homelessness has been a smaller issue inJapan than in many other developed countries, groups working on home-lessness may have had better chances of knowing and learning from eachother. Or they may have learned the standard services through organiza-tional media, such as videos, newsletters and homepages. It is also possiblethat, rather than through diffusion of some kind, similar services appearedas groups tried to help solve some of the most pressing problems thathomeless persons faced in the locale.

More important for present purposes, however, is the fact that, as Ifound out through my research, the meaning of these “services” differs,depending on the orientation of the group at a given moment in time. Forexample, a movement group in full operation would do the patrol to organ-ize homeless people, to encourage indigenous participation in the patroland other activities conceived as integrated parts of the movement. Anotheron decline may do the same patrol to save homeless individuals’ life and/or,like the Shinjuku Coalition, to disseminate information on public servicesavailable for the aggrieved. Similarly, some movement groups have createda job-offering non-profit organization (NPO) to build a community ofworkers, to lay the groundwork for future collective action, while othershave done so in an effort to make up for the absence or dearth of publicemployment opportunity. Further, as it happened in Shinjuku, a volunteergroup can turn into a stubborn critic of the local homeless policy and refuseto cooperate with public officials while movement groups actively endorseit. These and other similar instances imply that the self-claimed name of agroup does not always convey the substance of its activities.

Besides new groups, some existing private organizations also becameconcerned about the homeless problem. Generally, these entities have beenlarger and much more formal than the new groups. They include well-established religious organizations, bar associations, medical doctors’ asso-ciations, and major labor unions such as Rengo Osaka. Theseorganizations usually began their activities for the aggrieved only afterhomelessness drew wide public attention. Rengo Osaka, for instance, pre-pared a policy suggestion to the central government in 1998 and sponsoreda symposium on homelessness in 1999, recognizing homelessness as a seri-ous social problem that could afflict its members (Osaka Yomiuri, February25, 1999). Activities of attorneys at legal organizations expanded as theybecame aware of a range of problems that could be alleviated with theirprofessional expertise. Today, attorneys deal with cases involving, forexample, human rights, application for welfare, and personal bankruptcy.Religious organizations have tended to focus on the sheer survival needs

12 “We Are Not Garbage!”

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page 12

among the homeless. The involvement of these organizations in the home-less issue is noteworthy because, before them, few formal, professionalorganizations had taken action for the aggrieved.

The Shinjuku Coalition

Where is exactly the Shinjuku Coalition located in the organizational devel-opments described above? It is between the changing movement commu-nity in San’ya and the formation of new groups addressing homelessness.On the one hand, the Shinjuku Coalition reflected the reorganization andreorientation of the San’ya community as two leaders who stayed with themovement were originally members of the patrol team of the San’yaLeague. On the other hand, the Coalition was one of the new groups thatformed outside yoseba against the backdrop of rising homelessness in dif-ferent parts of cities. For the two leaders, Shinjuku was a relatively newplace as well as for a third leader, who was from a group in Shibuya thatfought for undocumented Iranian immigrants. Shinjuku was not thegroup’s field, either, and, although it had some contact with San’ya before1994, the contact was very limited.

The Shinjuku Coalition is unique in that it was one of the earliestmass-based movement groups in Japan that focused on the problem ofhomelessness and pursued policy to reduce it. The group is unique also inthat, as I mentioned before, it formed and led the movement in Tokyo andalso succeeded in national mobilization of the homeless albeit for a shortperiod of time. Tracing the history of the Coalition, therefore, enables us tocapture the development of and some of the central features of homelesspolicies in Tokyo and Japan.

At the same time, in many ways, the Shinjuku Coalition was similarto other mass-based movement groups on homelessness. First, like othergroups, the Coalition was a loosely, rather than formally, structured group.Second, the group consisted of a small number of non-homeless activists,who took leadership, and a larger number of homeless individuals, whoparticipated in standard activities and collective action events more or lessregularly. Third, turnover was high among homeless regulars.10 In Shin-juku, some left the movement when they obtained welfare or employment.Some of them came back to rejoin it for one reason or another. Othersremained with the Coalition for a long period of time as currently home-less. Still others did not join the Coalition while they were homeless butbecame regularly involved after they got off the streets. Finally, whileturnover was high among non-homeless members as well, there were a fewcommitted ones, similar to many other movement groups. In Shinjuku, sev-eral non-homeless activists were present at the beginning of the movement,

Introduction 13

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page 13

but one eventually left for Shibuya to create another movement group.Another died in a traffic accident shortly after the Coalition formed (Mitsu1995). However, the aforementioned three remained throughout the struggle.

Among the three, most committed was Takai. Originally from San’ya,he had long been interested in organizing homeless people. He assumed thetop leadership position in the Shinjuku Coalition, and chaired meetings,spoke for the group, and wrote almost all regular flyers, official statements,and letters of request. Also from San’ya was Harada, who became a sub-leader of the group. He worked primarily to plan, coordinate, and lead col-lective action events in which homeless people as well as other movementgroups participated. Takai and Harada were both in their 30s when theCoalition formed. Another sub-leader was Irino, a younger activist fromShibuya. His primary role was to take care of welfare and advocacy activi-ties. Takai and Harada left the patrol team upon the inception of the Coali-tion. Takai also left the San’ya League permanently as he became busy inShinjuku. Harada retained his membership in the San’ya League because,unlike Takai, he belonged to a New Left group whose main activitiesincluded those in San’ya.11 Later, Harada assumed an important position inthe National Federation of Day Laborers’ Leagues. Irino was a studentmember of the Shibuya group for Iranian immigrants, but, like Takai, even-tually left the group to work solely for the Coalition in Shinjuku.

THE MOVEMENT IN TOKYO IN THE RELATIONALPERSPECTIVE

To explain the emergence and development of the movement in Tokyo andthe gains achieved by the challengers, the present study draws on the rela-tional perspective. The relational perspective was recently put forward bypolitical process analysts (McAdam, Tarrow, and Tilly 2001), but it differsfrom the political process perspective in three important ways. First, toexplain movement emergence, the new perspective leads us to examinedynamic interactions among actors that unfolded well before initial mobi-lization took place. Second, the perspective activates what the politicalprocess approach treats as static variables to explain changes in action.That is, rather than treat such notions as opportunities (for action), mobi-lizing structures (or ties and networks among the aggrieved), and frames (ofopportunities, issues, and identities) as objectively given causes of changesin action, the perspective sees them as subject to active creation and appro-priation. Third, in the relational perspective, not only challengers but alsotheir opponents, especially the state, engage in such creation and appropri-ation. The state is no longer a static entity, as it is conceptualized in the

14 “We Are Not Garbage!”

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page 14

political process perspective, but an active participant in movements thatcontinuously interacts with challengers. The state and challengers respondto each other in action, attribution, and framing, sometimes transformingthe course of interaction itself.

In analyzing the movement in Tokyo, this study adopts these premisesas well as the concept of relational mechanism. Relational mechanismsdenote actions or events that alter connections among actors (McAdam,Tarrow, and Tilly 2001). In this study, I present as the main actors of themovement in Tokyo (1) non-homeless activists who led the Shinjuku Coali-tion, (2) homeless people in Shinjuku, including regulars, and (3) their tar-gets, in particular, the TMG and the Shinjuku Ward Government (SWG). Iask 1) what specific relational mechanisms changed the relations among thethree parties to the movement, and 2) how these tripartite relations wereassociated with goals, tactics, and gains on the part of the challengers. Forthe movement under study, I identify brokerage, repression, and certifica-tion as the key mechanisms that altered the tripartite relations. I argue thatthe ongoing tripartite relations in turn shaped the goals and tactics of thechallengers, thereby producing a unique set of gains under the given rela-tions. In what follows, I outline the story that I tell in the book on the basisof the relational perspective.

* * *

The movement in Tokyo emerged in early 1994 when the TMG evictedhomeless persons in an encampment in West Shinjuku and non-homelessactivists in San’ya and Shibuya responded to the eviction. Yet, long before itemerged, significant interactions had begun between the SWG and homelesspeople in Shinjuku. Recognizing the TMG’s plan to relocate its headquartersfrom Chiyoda to Shinjuku Ward as a great opportunity for the well-being ofthe town, in 1980, the SWG initiated what it called a “clean-up movement” tomake the town look good for the relocation. This movement, which lastedinto the 1990s, included patrols to chase homeless people away. During theperiod, the homeless resisted the movement in a number of ways, but mostthreatening to the local authorities as well as businesses was the creation in1993 of an encampment on the west side of JR Shinjuku station, which wasless than a mile away from the newly built TMG complex. Pressured by localbusiness associations and its own pending plan for road improvement in WestShinjuku, in February 1994, the TMG took action by conducting a large-scaleeviction of the homeless in the encampment.

This in turn gave an opportunity to San’ya’s patrol team that hadbeen interested in organizing the homeless beyond the district. Members of

Introduction 15

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page 15

the patrol team appropriated what social organization existed among thehomeless at the site, framed the homeless as “laborers” instead of“vagrants” (as they were called by local officials), and introduced to thesite familiar activities in San’ya, such as regular patrol and food serving. Inso doing, the activists organized a series of direct action protests at the pub-lic agencies involved in the eviction in an effort to restore the encampment.Growing numbers of homeless persons participated in these protests, andthey developed into a sustained interaction with the public agencies as theseagencies kept responding to the protestors in highly provoking ways. Sev-eral non-homeless activists and homeless people in the encampment thenformed the Shinjuku Coalition and began pursuing public guarantee ofemployment and livelihood.

Throughout the struggle, the Coalition upheld the goal of public guar-antee of employment and livelihood, but its operational goals as well as tacti-cal choices changed as it interacted with its targets. The operational goals theCoalition pursued were (1) mass negotiations, (2) communal protection, and(3) policy to help the homeless get off the streets. Its tactics largely involved(1) non-normative, direct action tactics, (2) non-institutional but acceptabletactics, and (3) institutional tactics. Using these tactics, the group achieved(1) “collective benefits,” which benefited all homeless people in Shinjuku(and sometimes beyond), and (2) a “selective benefit,” which benefited a lim-ited segment of the homeless population. Over time, operational goals, tac-tics, and gains shifted from the former toward the latter, although theysometimes coexisted or overlapped. To show how they shifted, I analyticallydivide the movement into three periods on the basis of the key relationalmechanisms that changed the tripartite relations. The three periods are (1)the initial period (early 1994-early 1996) following brokerage; (2) the transi-tional period (early 1996-late 1997) marked by repression; and (3) the finalperiod (late 1997-mid 2002) beginning with certification.

The initial period began with brokerage by the activists from San’ya.Brokerage brought homeless people in West Shinjuku into direct, con-tentious interaction with SWG and TMG officials. In doing so, it alsobrought the activists close to the homeless in and around the encampment.Brokerage led to solidaristic relations between the activists and the home-less on the one hand, and antagonistic relations between the two partiesand their common opponents on the other. Within a communal setting, thetwo parties set the overriding goal as well as the operational goals of massnegotiations and communal protection on the basis of common interests asopposed to the interests of the officials. The tripartite relations enabled thechallengers to use disruptive tactics throughout the initial period and anumber of collective benefits followed.

16 “We Are Not Garbage!”

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page 16

The transitional period began when the TMG repressed the ShinjukuCoalition by dismantling the encampment in West Shinjuku, arrestingTakai and Harada during an anti-eviction campaign, and depriving thegroup of direct access to TMG officials. Although the Coalition soon recre-ated an encampment in the station area, it no longer served as a communitybecause it permanently lost the spatial arrangements conducive to move-ment activities. The group also lost the key leaders for eight months anddirect access to TMG officials for the entire period. The absence of the keyleaders weakened the solidaristic relations between the leadership and thehomeless, while the lack of direct contact between the group and TMGofficials weakened antagonistic relations between the two. When Takai andHarada rejoined the movement, they shifted their attention from commu-nal protection to mass negotiations and policy, although the homeless weremost interested in spatial maintenance in the absence of a workable home-less policy. The tripartite relations rarely allowed the Coalition to use dis-ruptive tactics, and it achieved only one collective benefit.

The final period of the movement began with certification by the wel-fare branch of the TMG. Welfare officials at the TMG not only acceptedmass negotiations with the aggrieved but also recognized the Coalition as alegitimate group representing the interests of the homeless in Shinjuku.With this certification, the relations between the non-homeless leaders ofthe Coalition and welfare officials at the TMG became closer while thosebetween the leaders and the homeless became more distant. The Coalitionleadership created a dual internal structure in an effort to control the move-ment and began to mobilize homeless people on an individual rather thancommunal basis. The leadership abandoned communal protection andfocused on policy. It first sought a homeless policy in Tokyo in cooperationwith the TMG officials and then sought a national homeless policy withlegislators and administrators. These developments isolated the homeless inShinjuku because their spatial and communal concerns were left unat-tended while the leadership pursued its own agenda. In the final period, thecertified status enabled the Coalition to achieve a couple of gains withoutusing direct action tactics, but one of these gains was selective in nature.

The most important component of Tokyo’s homeless policy was theprovision of several year-round homeless shelters designed to help theaggrieved seek private, full-time employment while staying fed and shel-tered for a few months. These shelters, called “self-sustenance support cen-ters,” were meant for a small, “elite” segment of the homeless populationin the city who seemed ready to get off the streets through employment.Yet, it was not a promising measure even for homeless persons so qualified,given their past employment status and current housing status as well as the

Introduction 17

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page 17

depressed economy. In fact, the proportion of center users who perma-nently got off the streets was extremely small. By working with four othermovement groups based in San’ya, Shibuya, and Ikebukuro, the ShinjukuCoalition helped open three of these centers. Takai’s original plan was tobring public jobs into the facilities once they became available, but he failedbecause the alliance in Tokyo broke up as it engaged in a protracted cam-paign for these facilities. This development disappointed many of thehomeless who struggled with the Coalition to win them.

The Shinjuku Coalition then began to pursue national goals as thecentral government announced emergency homeless measures and showedinterest in having a homeless assistance act. Harada pursued a fuller policythan the emergency measures prepared by administrators while Takai andIrino pursued passage of a homeless assistance bill introduced by legisla-tors. The leadership, as well as movement and advocacy groups acrossJapan, split over the bill for it hinted eviction once it passed. Harada, withhis colleagues, mobilized homeless people from across the country for aworkable national policy while Takai and Irino joined the Kama Coalitionand other groups to support pro-act legislators. These moves, however, didnot excite homeless people in Shinjuku not simply because the targets werefar above them but also because their relations with the leadership hadweakened. In the final analysis, the Coalition leadership exerted little influ-ence at the national level. By the time the bill passed in mid-2002, Takaiand Irino in effect turned the Coalition into a pressure group. Later in theyear, Takai created an NPO with an advocacy group in Shinjuku to begintheir own employment program. Irino in the mid-2001 had become a direc-tor of another, larger advocacy group offering various services to the home-less. Some time later, Harada left the movement to assume familyresponsibilities.

RESEARCH METHODS

To trace the history of the movement in Tokyo, I relied on three sets ofdata. The first set consists of materials from the Shinjuku Coalition andother movement, advocacy, and volunteer groups as well as larger, formalorganizations that have worked on homelessness in one way or another.These materials include flyers, newsletters, newspapers, reports, videos,pictures, internal records and memos, public statements, petitions, letters ofrequest, and published books and booklets. The majority of the materialscome from the Shinjuku Coalition and other movement groups in Tokyo. Itried to be exhaustive especially with what the Shinjuku Coalition pro-duced, by itself or through commission. Unpublished, written documents

18 “We Are Not Garbage!”

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page 18

by the Coalition alone have amounted to 28 one-inch-thick binders. Theother materials are from groups and organizations in Tokyo, Osaka, Yoko-hama, Nagoya, and several other cities. I collected them to seek referencesto the movement in Tokyo and to know about the groups and organiza-tions themselves.

The second set of data originates from my own fieldwork and inter-views. I began mixing with movement groups in Tokyo in August 1998. Iattended their summer festivals and some of their weekly activities. Istarted intensive fieldwork in January 1999 and continued it until April2001. During this period, I participated in most of the collective actionevents that the Shinjuku Coalition sponsored, independently or with othermovement groups in Tokyo. Toward the end of my fieldwork, I also joinedCoalition-led rallies and demonstrations that targeted the central govern-ment. Besides these events, I attended the weekly activities of the Coalition,i.e., food service, patrols, meetings, and collective application for welfare,as well as some of its annual events, such as the Winter Struggle and sum-mer festivals. The frequency of my presence in the weekly activities varied; Ijoined food service and patrols most often and meetings and application forwelfare, occasionally. In addition, I went to San’ya, Shibuya, and Ike-bukuro to take part in some of the activities of the local movement groups.Further, I participated twice in the annual convention of advocacy groupson day labor and homelessness operating in different parts of Japan.

In addition to exchanging casual conversations in the field, I inter-viewed a few dozen currently and formerly homeless persons who weredeeply involved in and/or well informed of the activities of the ShinjukuCoalition. I also interviewed several currently and formerly homelesspersons who worked closely with the movement groups in San’ya,Shibuya, and Ikebukuro (see Appendix C for details of these interviews).I conducted some of the interviews during my fieldwork and others afterI finished it. To assure accuracy, before I began interviewing, I prepared along chronological table of movement events by using the first set ofdata. When necessary, I showed this table to my interviewees to helpthem collect their memory. I further set up a few lengthy interview ses-sions with the Coalition’s top leader because, in the field, he was usuallymuch less open and accessible than the sub-leaders of the group.Through the sessions, I learned his interpretation of the movement andview of the homeless constituency. I also cross-checked my materials as Iinterviewed him.

When I conducted fieldwork, there were several non-homeless volun-teers who came to the weekly activities of the Coalition to assist homelesspeople in trouble. I interviewed a few of them who came to the site most

Introduction 19

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page 19

frequently, to make sure that I did not miss any important event surround-ing the movement.

The third set of data was derived from all other sources, including themedia, academia, and government of all levels. The materials include news-paper articles, television programs, videos, reports, journals, books, andinternal and public announcements. The written and visual data are gener-ally about collective protests by the homeless, stories of homeless individu-als and groups, policy and programs targeting the homeless, and othermatters associated with homelessness. During and after my fieldwork, anumber of seminars and symposiums were held in Tokyo to study and/ordiscuss issues of homelessness. Whenever possible, I attended these eventsas they often invited as discussants public officials, professionals (e.g.,lawyers and researchers), and other individuals who once worked on home-lessness or were currently involved in the issue. I took the opportunities toask them, usually individually, questions about their experience with and/orview of the homeless problem and the movement in Tokyo. This practicegreatly enhanced my understanding of the subject of this study.

ORGANIZATION OF CHAPTERS

Before I examine the movement in Tokyo, in Chapter Two, I provide anoverview of homelessness in postwar Japan and discuss plausible causes ofor preconditions for the recent growth in homelessness. Homelessness didnot grow suddenly in the 1990s but appeared in large scale after the end ofWorld War II and some persisted well into the 1960s. The chapter firsttraces the growth and decline of homelessness in the two decades followingthe war end and then explains the reappearance of much homelessness inthe 1990s. I plan to show how shifts in the industrial structure and govern-ment policy as well as urban redevelopment that proceeded in the 1980spaved the way for a rapid increase in homelessness in the 1990s.

In Chapter Three, I lay the theoretical and empirical foundation ofthe present analysis. I first discuss the RM and political process perspec-tives of social movements some elements of which this study criticallyincorporates. I then introduce and examine some of the most systematicstudies on mobilization among the homeless in the United States in orderto draw attention to complexities that mixed movements such as the onein Tokyo tend to display. I will make the point that, while external col-laborators can play a significant role in improving the lives of theaggrieved, their relations with the constituency can change in ways thatconstrain movement gains. Finally, I elaborate the relational perspectiveas it pertains to the present study and define the concepts of collective

20 “We Are Not Garbage!”

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page 20

and selective benefits. I also summarize arguments which may apply toother mixed movements.

Chapters Four–Six correspond to the three periods of the movementthat I specified earlier. They are (1) the initial period (early 1994-early1996) following brokerage; (2) the transitional period (early 1996-late1997) following repression; and (3) the final period (late 1997-mid 2002)following certification. Each of these chapters examines the interactionamong the main parties to the movement, the ongoing relations amongthem, and the effect of these relations on goals, tactics, and gains of thechallengers. Chapter Four details how the future parties to the movementinteracted before the initial mobilization took place and how non-homelessactivists from San’ya subsequently organized the “unorganizable.” ChapterFive shows how spatial rearrangement of the encampment and the absenceof the key leaders of the Coalition weakened the relations between the lead-ership and the homeless. In Chapter Six, I show how TMG official’s accept-ance of the Coalition as a negotiator interacted with the ongoing internalrelations to the disadvantage of the aggrieved. At the end of the chapter, Ibriefly summarize my answers to the questions that I posed at the begin-ning of this chapter, and discuss some of the lessons that we might be ableto learn from the experience of the movement in Tokyo.

Introduction 21

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page 21

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page 22

Chapter Two

Homelessness in Postwar Japan

This chapter traces postwar history of homelessness in Japan and discussesplausible causes of its recent growth. In postwar Japan, one can identify acouple of times when homelessness increased sharply across the country;one is immediately after World War II, which ended in August 1945, andthe other is around 1992 when the Japanese economy was hit by the worstrecession since the war end. I first show how homelessness rose rapidly inthe aftermath of the war and how it persisted into the 1960s. I then charac-terize the more recent homeless population and explain why it began togrow rapidly in the early 1990s. I attribute the sharp growth of homeless-ness to three broad processes that unfolded in the 1980s in relation to eco-nomic globalization: (1) a shift from a manufacturing to a service economy;(2) urban redevelopment and gentrification; and (3) shifts in governmentpolicy toward deregulation and privatization. Yoseba men began to experi-ence long-term homelessness in the 1980s because their proneness to home-lessness interacted with parallel developments in the yoseba system.

HOMELESSNESS BETWEEN THE 1940s AND THE 1970s

The single most dramatic increase in homelessness in postwar Japanoccurred immediately after World War II. The direct cause of the increasewas Japan’s defeat; it threw the country into a catastrophic state and madenumerous people homeless. Already toward the war end, homelessnessbegan to increase especially in large cities as people lost housing due tointensive air raids and, in the case of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, atomicbombs. In Tokyo, Osaka, Nagoya, Yokohama, and Hiroshima, by August1945, 50 to 80 percent of the housing stocks that existed in 1943 weregone (Matsuo 1975a: 38) because of bombings and, to a lesser extent, relo-cation of housing to suburban and rural areas. While many city residents

23

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page 23

had moved to these areas to escape fire, with or without housing reloca-tion, others had remained in the city, sometimes losing housing and, atother times, life.

With the end of the war, homelessness rose rapidly in these and othercities as growing numbers of people found themselves jobless and house-less. According to a rough government estimate, during a two-monthperiod following the war, a total of 7.6 million soldiers were demobilized, 4million military factory workers were fired, and 1.5 million civiliansreturned from Korea and other parts of the world that Japan had colonizedor occupied (Matsuo 1975a: 40). Thus, more than 13 million people weresaid to be jobless at the time of the war end. The majority of these peopleshortly secured housing because they were from agrarian villages that werelargely left intact; they returned home to regain housing. They also securedemployment in agriculture (MITI 1954). Many others, in cities, obtained atleast temporary housing by moving to the suburbs and beyond or parts ofthe city that escaped fire. However, some had no choice other than sleepingin air-raid shelters that had been built before the war end, in shacks thatwere constructed with whatever materials left in the ruins, or on the streets.Immediately after the war, more than 400,000 households were estimatedto stay in air-raid shelters and shacks (Ueno 1958: 86), and perhaps tens ofthousands individuals slept on the streets. In Tokyo, about 93,000 house-holds, or 310,000 people, were in these types of self-made structures (TMG1972: 141) while thousands of others, including war orphans, were said tobe on the streets.

Government response to the widespread homelessness was largely apatchwork of emergency measures, which in no way succeeded in eliminat-ing it. One early measure planned by the central government was to pro-vide, within the year 1945, 300,000 relief housing units for war-damagedhouseholds that were now in shacks (Ueno 1958: 13). However, it offeredonly 81,000 such units by March 1946 (ibid.). Although about 160,000units were added between 1946 and 1949 (ibid.), they were hardly suffi-cient to meet the housing needs of shack dwellers.

Another measure was welfare. In 1946, the government, in responseto a command by the General Headquarters of the Allied Forces (GHQ),prepared emergency relief and enacted a Livelihood Protection Law. Theformer consisted of food, lodging, clothing, and other necessities of life,but, again, it was hardly sufficient and reached only a small portion of thedestitute (Shibata 1998). The latter made available a public assistance pro-gram that reflected the GHQ’s effort to demilitarize Japanese society(Soeda 1995). The country’s welfare had favored the military class and,against the GHQ’s quest for “public” assistance, the government initially

24 “We Are Not Garbage!”

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page 24

tried to depend on private organizations for welfare. The law was anachievement in that it clarified the government’s responsibility, as a princi-ple, to provide for all the poor in need of public protection. The livelihoodprotection program covered large numbers of people—a total of 1.64 mil-lion in 1949 and 2.04 million in 1950 (ibid.: 33). However, it assured littlemore than minimum food intake because benefit levels were so low; in1948 when they reached the highest level since the enactment of the law,they were still below 40 percent of the average living expenses of allhouseholds in Japan, the majority of which were poor by any standard(ibid.: 24).

A third component of the welfare measure was to place homeless peo-ple in welfare facilities, especially those on the streets. This practice, alsobased on the GHQ’s command, began before the emergency relief and thepublic assistance program mentioned above, because this form of homeless-ness threatened public order. In Tokyo, at the time of war end, there wasonly one welfare facility that the Tokyo Metropolitan Government (TMG)operated directly. In a six-month period from September 1945, the govern-ment of Tokyo sent a total of 3,603 street homeless to the facility (Iwata1995: 61). In 1946, the same facility received a total of 11,442 homeless(ibid.). In Osaka, between November 1945 and March 1948, the city’s con-sultation center for the homeless and people at risk of homelessness dealtwith a total of 11,648 homeless men alone (Honma 1988: 105). In Nagoya,the number of homeless sheltered through outreach reached its peak in1947 at 3,696 (Tamaki 1995: 78). To contain the homeless, local govern-ments opened welfare facilities one after another. According to a 1953national survey of all types of welfare facilities, nearly 40 percent of the1,279 units that existed in Japan in that year had been newly set upbetween 1946 and 1950 (Iwata 1995: 90). Among other types of welfarefacilities, the newly created ones heavily concentrated on rehab centers andlodging houses, known as “vagrants’ camps” at that time.

The problem with this practice was that it was forceful and resisted by“vagrants,” especially able-bodied ones, including children. Institutionaliza-tion of homeless people on the streets accompanied what was calledkarikomi whose meaning is close to “hunting” in English. In Tokyo, forexample, “hunting” teams drove to places where homeless people congre-gated, put them on vehicles, and drove them to welfare facilities (Iwata1995). Because able-bodied persons wanted jobs rather than a filthy,crowded shelter, they often ran away from the facility or, if they stayed,spent the day time working outside (ibid.). In Tokyo, recognizing it better toput some of these persons in rental facilities, the TMG helped private enti-ties run “tent hotels” and flophouses in several parts of the city, including

Homelessness in Postwar Japan 25

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page 25

San’ya. By April 1947, these rental facilities grew to shelter a total of47,000 homeless people at a time (Imagawa 1987: 30–31). San’ya, with along history as a cheap lodging district, was flattened by an air raid inMarch 1945, but shortly revived as a day laborers’ quarter partly becauseof this arrangement (Iwata 1995).

A final measure against homelessness was employment. One way inwhich homeless people regained employment and often lodging wasthrough the demand for day labor created by the GHQ, which needed man-ual labor for various purposes, including preparation of infrastructure tooccupy Japan, securement of petty services to run the daily business, andoperation of military bases and ports. To meet the demand, in 1946, thegovernment opened up recruitment centers in 83 places across the country(Imagawa1987: 148). Many homeless people, especially single and mobileones, responded to this demand, including those in San’ya. The governmentalso encouraged homeless people to move to Hokkaido and Kyushu towork in coal mines (Honma 1988). Especially after 1946, to reconstructthe economy, the government adopted a priority production system thatemphasized the coal and steel industries (Matsuo 1975b). Labor wasneeded in the coal industry to make up the loss of Korean and Chineselabor; a number of Korean and Chinese people had been forced into Japanto labor for this and other industries, but many went home after the coun-tries won territorial freedom from Japan. Homeless people took this oppor-tunity, too, including those who were once sheltered in welfare facilities.1

Compared to other measures, employment received scant attentionbecause the government saw homelessness as a matter of relief and publicorder rather than an issue of employment (Yoshida 1993, 1994). It intro-duced a public employment program in 1946, but the program mainly ben-efited the elderly and war widows (Matsuo 1975c), who presumably hadan address. The private sector did not offer much employment opportunity,either, especially in the formal sector in which even large firms were busytrying to fire, rather than hire, employees (Ôkôchi 1955). Under the cir-cumstances, homeless people strived to survive on their own. Some workedas black market brokers or as their hands; after the war, black marketssprang up all over Japan as the ration system had ceased to bring sufficientnecessities of life. Others took petty jobs on the streets, such as street vend-ing and rag picking. Rag picking grew into a popular job among people inshacks. For women, street prostitution was another popular job in the earlypostwar years (K. Takahashi 1999; Yoshida 1993).

Literature referring to public measures on homelessness and direpoverty in the aftermath of World War II generally indicates that they failedto cope adequately with the phenomena. The failure must be seen within

26 “We Are Not Garbage!”

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page 26

the context of the disastrous condition of the economy. By the end of thewar, Japan had lost one-fourth of the wealth that it had a decade earlier(Economic Planning Agency 1993: 11). Production and distribution sys-tems were either destroyed or paralyzed, and there was a severe shortage ofraw materials (Yoshida 1993). By August 1945, mining and manufacturingindustries produced less than one-tenth of what they did on average in a1934–1936 period (Y. Andô et al. 1977: 249). The agrarian sector did notdo any better. In 1945, it experienced the poorest harvest since 1905 (Mat-suo 1975a: 40), and in the following years, massive inflows of returneesfrom abroad worsened food shortages both in rural and urban areas (Fuji-wara 1975). In addition, the government was heavily in debt because ofmilitary spending during the war.2

Nevertheless, it is wrong to assume that the inadequacy of measuresstemmed from the disastrous economy alone. Despite the debt, the gov-ernment continued to spend to make up losses for military firms and per-sonnel—losses that resulted from the demise of the war economy.3 It alsoallowed banks to generously finance these firms.4 Although the govern-ment explained that these decisions were to help military firms switch tocivilian production and curb war-induced inflation, the decisions, in fact,accelerated inflation because the government did not introduce a policyto increase production, which was needed to fulfill the alleged purpose(Economic Planning Agency 1993). The only measures that the govern-ment took to raise production levels was to increase the availability ofraw materials by promoting production of coals and, with the military,selling to private firms war materials that it had.5 However, coal produc-tion did not rise much, and firms, because of inflation, channeled a largeportion of the munitions into speculative and under-the-counter tradingto make easy gains rather than to resume production. The governmentthus failed to reduce inflation, delayed economic recovery, and, by doingso, ensured that a significant number of homeless people were insuffi-ciently attended at best.

Economic recovery began rather abruptly with the outbreak of theKorean War in June 1950. The war created huge demand for goods andservices in Japan. Domestic demand grew, too, following wage rises andincome tax cuts (MITI 1954). Accordingly, production in mining and man-ufacturing exceeded the prewar level6 within the year 1950 (Y. Andô et al.1977: 327). The real GNP recovered its prewar level in 1951 (ibid.), andper capita real income, almost in 1952 (MITI 1954: 76). In the mid-1950s,Japan further entered the high growth period, bolstered by technologicaltransfers from the United States, cheap raw materials from developingcountries, and abundant labor from domestic agrarian areas (Itoh 1990).

Homelessness in Postwar Japan 27

96460_Hasegawa_04 06.qxp 4/6/2006 5:08 PM Page 27

From 1961 until 1973 when the growth period ended, the Japanese econ-omy grew annually at an astonishing rate of 9.4 percent on average (ibid.:140). Growth was led by the heavy and chemical industries, which vigor-ously invested in plants and equipment while using low-cost domestic laborand foreign materials.