Master Erasmus Mundus Crossways in European Humanities Mexico in the films of Luis Buñuel Dissertation Presented by Elsa Barreda Ruiz Home University: Università degli studi di Bergamo Supervisor at Home University: Prof. Stefano Ghislotti Facoltà di lingue e letterature straniere Semester 2 University: University of St Andrews Supervisor at Semester 2 University: Prof. Bernard P. E. Bentley School of Modern Languages / Spanish Department Semester 4 University: Universidade Nova de Lisboa Supervisor at Semester 4 University: Prof. Fernanda de Abreu Departamento de Línguas, Culturas e Literaturas Modernas Secção de Estudos Espanhóis, Franceses e Italianos Lisbon, June 2007

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

Master Erasmus Mundus Crossways in European Humanities

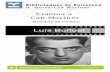

Mexico in the films of Luis Buñuel

Dissertation Presented by Elsa Barreda Ruiz

Home University: Università degli studi di Bergamo Supervisor at Home University: Prof. Stefano Ghislotti

Facoltà di lingue e letterature straniere

Semester 2 University: University of St Andrews

Supervisor at Semester 2 University: Prof. Bernard P. E. Bentley School of Modern Languages / Spanish Department

Semester 4 University: Universidade Nova de Lisboa

Supervisor at Semester 4 University: Prof. Fernanda de Abreu Departamento de Línguas, Culturas e Literaturas Modernas

Secção de Estudos Espanhóis, Franceses e Italianos

Lisbon, June 2007

2

A mis padres

3

Contents

Introduction……………………………………………………………………................4 Chapter one Mexican Cinema and the Idea of a Nation

1.1 The Mexican Revolution and the Birth of Nationalism…………..………….6 1.2. The construction of a national identity……………………………………..11 1.3. The Golden Age of Mexican cinema……………………………………….13 1.4. Ideology and the allegories of Mexicanidad………………………………..17

Chapter two Luis Buñuel in Mexico

2.1. Antecedents of Luis Buñuel’s Artistic Trajectory………………………… 21 2.2 Luis Buñuel and the Mexican Film Industry………………………............. 25 2.3 Buñuel’s Mexico: Cultural Encounters and Continuities…………………...29

Chapter three Mexico in the Films of Luis Buñuel

3.1 Analysis of Susana, La ilusión viaja en tranvía and El río y la muerte….... 34 3.2 Patriarchy and the Mexican Family: Susana………………………………..36 3.3 Modernity, class and the illusion of change: La ilusión viaja en tranvía…..40 3.4 Machismo and the State: El río y la muerte……………………………….. 46 3.5 Female Desire: Susana, Lupita, Mercedes….................................................50

Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………55 Annexe Luis Buñuel’s Mexican Filmography…………………………………………………...56 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………….66

4

Introduction

This is a work that studies the Mexican films of Luis Buñuel, concentrating on

the ways they were permeated by Mexican history and culture and how the author

adapted to the context of Mexican film industry by appropriating the diverse cultural

traits into his work.

Luis Buñuel directed 21films in Mexico. His capacities as a film director matured

in this country, where he made many of his most outstanding films. Yet, in very few

occasions has the dialectic relationship between the author and the culture of this

country been considered subject of study and nor have the films of this period of the

director’s career been regarded as representative of Mexican cinema or Mexican culture.

It is evident, however, that in these films Luis Buñuel managed to capture the essence of

Mexican idiosyncrasy and merge it with features of his artistic background, his native

country’s literary tradition and his particularly Spanish sense of irony and humour.

Moreover, these films give account of formal, aesthetic, ideological characteristics that

are specific of the Mexican film industry and particular to the period of the Golden Age,

and therefore can also be analysed as cultural texts that reflect on a particular socio-

economic context, and that influence the outcome of his work.

We have, therefore, set out from the consideration that the ways in which Buñuel

adapted to the Mexican cinema narrative paradigm provide with an understanding of the

way he saw and embrace his adoptive country and therefore we pose the question of

what is then, the Mexico that can be read in his films?

The first chapter is an overview of the historical antecedents that gave rise to

Mexican nationalism and of the development of the film industry during the years

known as the Golden Age. In it, we go through the elements that favoured cinema as a

pivotal medium for the construction of a national identity and the endorsement of the

ideology of the post revolutionary governments; we describe how this was accomplished

through the delineation of a set of aesthetic and ideological values that constituted the

narrative paradigm trademark of national cinema

5

Chapter two focuses on Buñuel’s artistic trajectory and the way his Mexican

work has been regarded by critical readings. By analysing some of these readings, we

sort out the difficulties of analysing the work of an auteur and surrealist artist within the

context of a national cinema largely regarded as constrictive and ideologically dominant.

We intend to widen these precepts in order to see Buñuel’s Mexican films as cultural

texts that cannot be separated from the context in which they were made but that are also

embodiments and reflection of the author’s specific choices, artistic trajectory, and

personal condition as exile.

Chapter three comprises the analysis of three of Buñuel’s Mexican films: Susana,

La ilusión viaja en tranvía and El río y la muerte. In them we analyse the different ways

in which Buñuel saw and embraced the culture of his adoptive country. This study is

informed by feminist, historical and psychoanalytic analyses of Mexican national

cinema, adapted as reading strategies to look for the ways in which Buñuel’s films

converge or differ with classic Mexican films whilst also functioning as a reflection of

his personal point of view.

6

Chapter one Mexican Cinema and the Idea of a Nation

1.1 The Mexican Revolution and the Birth of Nationalism

The Mexican Revolution was a social, popular movement that is considered to be

major rupture in the course of Mexican history, an event that came to break all the

established structures that were settled in the form of a republic in the nineteenth

century, following the war of independence and that still dragged elements from the

colonial system that had not yet completely been eradicated. The revolution is the event

that eventually catapulted the country into a complex process of modernisation and also

set the bases for the political delineation of twentieth century Mexico.

The Mexican Revolution occurred very early in the twentieth century and in

circumstances that drastically separates Mexican history from the history of most of the

countries in the region of Latin America. It can be fairly argued that any country’s

history is particular, but indeed the outcomes of Mexican revolution, the emergence of

mass mobilisation and popular participation in political affairs and the conformation of a

solid –if authoritarian and self perpetrating– political party came quite precociously to

Mexican history and prevented Mexico from undergoing the series of failed revolutions

that carried with them totalitarian and militarised governments across Latin America

later in the century. In opposition to this, Mexico enjoyed a relatively calm process of

transition to democracy, by maintaining a status quo difficult to place in the concepts of

modern democracy: the party that was in the power for over seventy years managed to

maintain peace and a certain amount of freedom, but keeping hold of authoritarian,

totalitarian and repressive mechanisms that left room for little explicit dissidence,

especially before the 1970s. Many argue that much of this was accomplished by the

party’s consistent cultural policies, (Noble, 2005: 12), and indeed one thing that

characterises Mexican society under the institutionalised revolution political system is

the common, social acceptance of governmental authority to apply social order and

maintain a ‘peaceful’ status quo in exchange of social justice and economic equality.

7

The Mexican Revolution exploded after a pivotal interview President Porfirio

Díaz, who had held power for 32 years, gave to American journalist James Creelman

from the popular Pearson’s Magazine in February 1908. In it, Díaz said he would

definitely abandon his charge once his ruling period was finished. (Womack 1968: 17)

Díaz was known for constantly promising his resignation and free elections, but his 78

years of age seemed to say this time he meant it.

Díaz’s regime was characterised by authoritarian and repressive policies exerted

to hold central power and by his particular interest in the material modernisation of the

country. He had commanded the construction of the railway system (entrusted to

European companies) whilst at the same time neglecting the precarious situation of

abject misery in which most of the population survived. Wealth and land, were kept in

the hands of a few privileged families who preserved the feudal and casts system that

prevailed from colonial times and that even dragged with it traits from pre-Columbian

hierarchical organization.

The revolution came then to overthrow the regime of Díaz, and, in a first

instance, with the main objective of establishing a true democracy, as was the call to

arms of Francisco I. Madero, a wealthy landowner from the northern state of Coahuila

who became president on the defeat of Díaz. The struggle, however, did not emerge as a

planned and organised movement led by Madero and his elite group holding a specific

ideology; instead, it exploded simultaneously in several places throughout the country,

gathering the general discontent that reigned among the population, which was as varied

and diverse as were the injustices put on them. Different outbursts grouped then

regionally, each group following its leader and brandishing its own specific demands.

Popular demands transcended the elemental and the immediate; as it has been

suggested by many scholars1, the main drive of the revolution was the claim for the

restitution of land, and people adhered to it so fiercely because they searched the

restitution of the core of their communal and social organisation. The struggle for land

dates back to the ancient tradition of the indigenous past that gave land a transcendental

importance and of which values were transmitted from generation to generation.

1 We are concentrating on the writings of Octavio Paz (1993) but on this conception we can also see John Womack (1968) and Carlos Fuentes (2000)

8

Mexican thinker Octavio Paz (1993) suggests that the spontaneity of the popular

movement is what separates it drastically from the revolutions of the nineteenth century

across Latin America, but most particularly from the Mexican liberal movement of the

1850s, a movement that followed European ideals and had been influenced by the

French Revolution and the Independence of the United States,

[A la revolución mexicana] no la guió una teoría de la igualdad: estaba poseída

por una pasión igualitaria y comunitaria. Los orígenes de esta pasión están no en

las ideas modernas sino en la tradición de las comunidades indígenas anteriores a

la Conquista y en el cristianismo evangélico de los misioneros

Paz, 1993: 33

[The Mexican revolution was not guided by theories of egalitarianism: it was

possessed by a passion both egalitarian and communitarian. The origins of this

passion are not in modern ideas but in the traditions of indigenous communities

prior to the Conquest and in the evangelic Christianity of the missioners.]

Being a movement that had a profound popular impulse, however, the revolution

was riven by the diversity of the factions that compounded it. In the south, the

movement was mainly agrarian; an army of campesinos led by the charismatic leader

Emiliano Zapata had raised in an authentic and politically disinterested quest for the

disintegration of the feudal system by which they had been perpetually stripped of their

lands; in the north, on the other hand, the groups led by Pancho Villa were mainly

ranchers who adhered more easily –though not quite- to the lineaments of the bourgeois

middle-class leaders from the urban centres, and preparing a new constitution and had

political aspirations.

This diversity of factions would influence dramatically the course of the

revolution and determine its outcome after ten years of devastating civil war. The

struggle was far more complicated than a fight between oppressors and liberators, thus it

cannot be easily put down as a winning-losing situation among groups: The leaders of

the different factions were all victims of subsequent political assassinations by their

9

contestants, and the triumphant rise of the middle class Constitutionalists in 1917 was

received with strong opposition by Zapata’s army in the south and Villa’s instigation of

a guerrilla war in the north.

In 1920 Carranza, the leader of the Constitutionalists was assassinated, leaving

the new government in hands of General Plutarco Elías Calles, who established a

mechanism of political continuity that searched to maintain the power in the hands of the

bourgeois, whilst also trying to build a political compromise that would include and

satisfy, at least until a certain extent, the demands of the other factions. The end of the

armed struggle saw then the beginning of the so-called period of institutionalisation of

the revolution in which, after the creation of a ‘revolutionary’ party Calles and the

subsequent governments would apply policies of nationalisation, bureaucratisation and

economic development.

With very different protagonists from the ones that starred the first stage of the

Revolution, -defined by Octavio Paz as a group of politicians and technocrats, the

popular movement turned shortly into an institutional regime with the creation of the

PNR (Partido Nacional Revolucionario, that would later become the PRI, Partido de la

Revolución Institucional) a party of state that would govern Mexico uninterruptedly for

seventy-one years ant that set the bases for an authoritarian political culture, background

to the project for the new nation that held as main objective the political stability of the

country and its modernisation and economic development.

The social tissue of the new nation had, however, changed dramatically. Other

than carrying on with a political compromise, the leaders of the new governments had

also to face up one of the most important legacies of the revolution: the rise of the

pueblo, the real protagonist of the revolution, “not as an elite, bourgeois concept, as it

had been up until this point, but a popular construct embodied in the masses” (Noble,

2005: 10); and that until then had been ignored in every period of Mexican history:

“grupos y minorías que habían sido excluídos tanto de la sociedad novohispana como de

la republicana […] comunidades campesinas y, en menor grado, a las minorías

indígenas” (Paz, 1993: 35) [Groups and minorities that had been excluded both from the

New-Spain and Republican societies (…) peasant communities and, on a lesser degree,

the indigenous minorities]

10

Indeed, the toppling of Díaz and the subsequent ten years of struggle that defined

the direction of the revolution had involved a level of mass mobilisation with which

came “new popular forces, manifested in social banditry, guerrilla and conventional

armies, sindicatos and mutualist societies, peasant leagues and embryonic political

parties of both Right and Left” (Knight, quoted in Noble, 2005: 10) and with which the

new governments saw themselves dealing with.

The PRI applied policies derived from the claims of the revolution, such as

agrarian reform, secularisation, and education reforms. At the same time it concocted a

complex hierarchical system that did not differ much from that that had been just

overthrown, and to do so, it had to extend its arms of influence to every corner of social

interaction. A strong bureaucratic mechanism guaranteed the adherence of every small

community to the party, in the form sindicatos, town councils, communal groups who

reinforced and promoted recurrent image of the big “familia revolucionaria” a great

revolutionary family where ‘father government’ was to provide for the population’s (and

this always meant the masses) well being.

Modernisation, however, did not arrive all at once and the policies of

urbanisation and industrialisation had to coexist with the big wounds that ten years of

civil war had left in society: the loosening of the family bonds due to immense death toll

and population shift from one place to another, the almost paralytic state of agricultural

economy and the disintegration of traditional forms of socialisation related to the

immediate, rural community. Therefore, the masses had also to be educated and bridged

to the new forms of socialisation ensued by modern practices. In this process culture and

the mass media played an extremely valuable role as it has been argued by Andrea

Noble (2005) who goes even further arguing the State’s cultural politics articulated the

different media into a project of state that ensured, at the same time, the prevalence of

the social order, noting, however, that it is “important not to over exaggerate the notion

that culture is a top-down hegemonic construct imposed on the masses fro above.

Instead, […] these relationships must be understood in terms of accommodations and

negotiations between the various sectors in society.” (Noble, 2005: 12)

11

1.2. The construction of a national identity

The social effervescence of the revolution contributed to the birth of one of the

most important cultural and intellectual movements of Mexican history. The armed

struggle stirred the creativity and the thought of intellectuals and artists, who debated

between the ideas of progress and capitalism and the influence of socialism and the

Russian revolution. Literature, music, cinema and the plastic arts all would be

profoundly marked by the aesthetics of the revolution. The revolution put an end to the

naturalist literature that had predominated in the nineteenth century, and that was very

much influenced by European literary schemes, and replaced it with a more realistic,

rough prose, direct and sometimes crude that gave shape to the ‘novela de la

revolución’, the novel of the revolution that would influence decisively the course of

modern Mexican literature; in the field of the plastic arts, the decades following the

revolution saw the emergence of Muralism, one of Mexico’s most distinctive pictorial

movements.

Muralism was perhaps the artistic expression that embodies Mexico’s systematic

desire to interpret, reinterpret and exalt the revolution and definitely the movement that

passed Mexican cinema its aesthetic and ideological referents.

Muralism can be taken as the art form that embodies Mexico’s many times

contradictory approach towards its search for identity. Its importance as pictorial

movement ranges from aesthetics to politics, and much of the path followed by Mexican

classic cinema could not be understood without taking muralism into account. It

developed the aggrandising and dramatic aesthetics that characterise Mexican art and

that would remain as reference for further artistic expressions, moreover, the movement

was fundamental for the ideological reconstruction of the revolution in Mexican history

and collective memory.

The muralist movement was mainly supported by philosopher José Vasconcelos,

also minister of education (1921-1923) who had propelled an important educational

reform and promoted the redefinition of government policies regarding Indian

communities. He is given credit for modern indigenismo, the governmental, mainly

protectionist, policies regarding the Indian population. He exalted, on the other hand, the

quintessential Mexican-ness as embodied in the mestizo race, the ultimate convergence

12

of both Hispanic and pre-Columbian culture in what he called la raza cósmica, the

‘cosmic race’.

Muralism gathered much of Vasconcelos’ ideology and served the purpose of

bringing art and education to the masses. Its major exponents, Diego Rivera, David

Alfaro Siqueiros and José Clemente Orozco, acknowledged and exalted in their work the

participation of the masses in the revolution, and intended to place them as protagonists

in the centre of the historical paradigm as they have never been before. To do so, they

merged different historical symbols that had come to surface as part of the imaginary of

the revolution, and the masses were then portrayed as a compound of the oppressed

groups that carried with them the culture and tradition of ancient Indian civilisation, but

they were both Indian and mestizo, had fought the independence war a century earlier to

bring down Spanish rule and were the ones who fought the revolution to recover their

ancient and mystical right to land and freedom.

Governmental cultural policies adopted also this ideological paradigm to

welcome the masses to the new project of state: the figures of the uttermost popular

leaders of the revolution, Villa and Zapata, were stripped of any political stigma and

mystified as fallen heroes for the people. The masses were recognised as keepers of the

essence of Mexican-ness because they were the ones who had defended it throughout

history, and now they were to be kept safe as children of the revolutionary patriarch: the

system.

The rise of the mass media also contributed for the consolidation of these post-

revolutionary ideals. Modern forms of socialisation implied the birth of cultural

consumerism, and different media emerged to fulfil this need in the form of “tabloid

newspapers, comic books, radio and increasingly cinema [that] began to insinuate

themselves into everyday Mexican experience” (Noble, 2005: 11), forging and

broadcasting a national, common imaginary.

Cinema, a medium whose development already had a long history of ups and

downs since its arrival to Mexico in 1896, emerged as both the public and the

government’s favourite medium. After a deep drawback during the revolution, when all

the incipient developments of the industry were abruptly cut, cinema started recovering

13

in great paces, taking advantage of a brief halt in Hollywood industry due to the advent

of sound.

It started taking hold of the market gap left by the absence of appealing

Hollywood films2 and of the incursion of actors and other workers of the industry that

had trained in Hollywood.

Several of the films of this first stage of the Mexican film industry took form and

exploited many of the themes and ideals of the new nation, portraying an optimistic

image of cosmopolitanism and unity. In the same way this period saw the emergence of

many of the stylistic formulas and thematics that were to be constantly re-elaborated

throughout the history of Mexican cinema, such as the good-hearted prostitute

melodrama, who first appeared on Mexican screens as Santa (Antonio Moreno, 1932)

and would give way to the later cabaretera films, the family melodrama, the urban

comedy (especially those of Mario Moreno ‘Cantinflas’) and the most successful genre

of all, the Comedia Ranchera, inaugurated in 1936 by Fernando de Fuentes’ Allá en el

rancho grande.

Even though the consistent blooming of the film industry (in 1933, only one year

after Santa’s release, the Mexican film industry produced twenty-one films, making it

the leading producer of Spanish-language films in the world) it would take one more

decade for Mexican film industry to consolidate as the country’s third major industry,

the main exporter of cultural images and the creator of customs, inventor of traditions

and nourishment “in one or another [of] the diverse social groups that inhabit Mexico”

(Ramírez Berg, 1992: 1)

1.3 The Golden Age of Mexican cinema

Perhaps cinema could not have served so efficiently to the consolidation of

Mexico’s hegemonic system had it not been caught in the middle of a financial miracle

2 In order not to lose the income of the important Spanish-speaking audiences, who were rejecting sound films with subtitles (the rate of illiteracy was particularly high in the 1920s) Hollywood started producing ‘Hispanic’ films, in which Hispanic actors from different nationalities performed together (sometimes a Spanish, a Mexican and an Argentine were members of the same family!) this created confusion to Spanish-speaking audiences, who rejected these products and even considered them to be offensive and denigrating (García Riera ,1969: 20)

14

boosted by the Second World War, when political and economic factors influenced its

development and contributed for its becoming of a true industry.

The position that the Mexican government adopted during the war was the factor

that most tellingly beneficed Mexican film industry. In 1942, after the attack of two

Mexican oil ships by German submarines, President Manuel Ávila Camacho declared

war against the Axis power giving Mexico entrance to the conflict on the side of the

Allied.

This decision saved Mexican cinema from virtual extinction. The national

industry was resenting the shortage on raw film and other filming products imposed by

the United States due to the practical use of the material used for their fabrication in the

making of arms. The sales of raw film were limited for Hollywood production, where

mainly propaganda films were being produced.

Latin American audiences, on the other hand, were not being receptive to

Hollywood films as they did not feel identified with the war cause, and Hollywood

studios were suffering the loss of one of its most important marketplaces.

The adherence of Mexico to the Allies, then, made it the only country, among the

other two big film industries in the Spanish-speaking world, Spain and Argentina (who

declared neutral during the war), that could have access to raw film. This move

functioned well for both sides. Mexico became a faithful market partner both consumer

of filming products and films and Mexico had a cleared Spanish-speaking market where

Hollywood’s absence was to be filled.

The Mexican government shortly realised the importance of supporting the

development o the film industry. In 1943 the Banco Cinematográfico was founded, it

began as a private institution backed by official agencies like the Banco de México and

Nacional Financiera, which held 10 percent of its stock. It was evident by the creation of

this entity that the endorsement of the national film industry was a main objective of

President Ávila Camacho’s government (1940-1946). In its first year it extended credits

of 5 million pesos to small, undercapitalized producers and within two years it had

boosted the Mexican production and helped it become a true industry. Seventy films

were produced in 1943, while Argentina’s output declined sharply to thirty-six motion

pictures. (Mora 1992, 59) Only a few years before, the state had guaranteed a loan to

15

finance the construction of the first modern film studio in Mexico City in 1934, Estudios

Churubusco. This gave rise to a dynamic economic partnership of nationalized industry

and private enterprise that continues to characterize the Mexican film industry to this

day.

The boom of Mexican cinema favoured the emergence of a new generation of

directors like Emilio Fernández, Julio Bracho, Roberto Gavaldón and Ismael Rodríguez,

and the consolidation of a star system as never seen in the context of Spanish-speaking

cinema: María Félix, Mario Moreno ‘Cantinflas’, Pedro Armendáriz, Andrea Palma,

Jorge Negrete, Sara García, Fernando y Andrés Soler, Joaquín Pardavé, Arturo de

Córdova y Dolores del Río became the equivalent to the big Hollywood names and

attracted audiences steadily into the cinemas.

One of the representative figures of the Mexican cinema of this period is Emilio

“El Indio” Fernández; arguably the director who most successfully projected an ideal

image of the nation and whose epic stories, set in endless and vast landscapes constituted

the trademark of what is known as classic Mexican cinema.

Emilio Fernández effectively managed to convey the nationalist sentiments that

had been gathering since the revolution in other artistic expressions and the ideological

traits that were inherent to this nationalism. He also established, in collaboration with his

working team, cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa and scriptwriter Mauricio Magdaleno,

a distinctive narrative style that converged with the characteristic visual lyricism of

strong Eisenstenian influence and the art of the muralist painters of the 1920s and 30s.

When Fernández began directing after having pursued a career as an actor where

he usually played the role of an Indian (hence his nickname, “El Indio”), he chased the

ideal of creating a vital national cinema that would tell Mexican stories that were about

Mexicans and for Mexicans; he believed that until then Mexican cinema had been

derivative and lacked imagination, “copied from Spanish theatre or from Hollywood”

(Ramírez Berg, 1994: 14).

The cinema of El Indio was therefore carrier of great ideological hues that

reinforced the progressive force of modernisation whilst also exalting the Indian

component of Mexican society in an idealised and romanticised representation of Indian

characters and of Mexico’s rural landscape. His cinema skilfully projected a set of

16

values that collected symbols and mythologies of the many Mexicos that emerged from

the revolution and catapulted them into an ideal of a modern, post revolutionary nation

that was well articulated into a capitalist system and mainly of mestizo compound. His

cinema also conveyed a message that secured the protectionist role of the state as centre

of the social order by legitimising the figure of the patriarchal family institution by

which all social structures were defined.

The work of Fernández has been defined by many critics as monolithic, for the

way it represents society is mainly static and hieratic, and aesthetic exaltation of the

landscape and the prominence given to strongly typified characters convey a one-

dimensional idea of a nation, one that looks back to reinterpret history from an

ideological standpoint, intending to legitimise the social and political status achieved by

the post revolutionary governments.

A good example of this is Fernández’s first film Flor Silvestre (1943), a

revolutionary melodrama that deals with the issue of the clash of social casts that existed

in the feudal system before the revolution. The film tells the story of José Luis (Pedro

Armendáriz), the son of a wealthy landowner who falls in love with Esperanza (Dolores

del Río) a poor peasant girl, daughter of a peon who works in José Luis’ estate. The

social impediment for the couple is such that the young couple is obliged to elope. They

marry and have a child but the revolution breaks cutting short their idyllic marriage. José

Luis leaves for battle on the side of the revolutionaries; he dies in combat whilst

Esperanza is left to her fortune. The plot is darkened by the cruelty of the revolution but

the film glimpses of hope are embodied in the José Luis and Esperanza’s son, to whom

the story is told in retrospective by his aging mother.

Using memory as a narrative device is frequent in period films for a specific

purpose, argues Andrea Noble (2005: 59-60). Esperanza and her son are the “Symbolic

embodiments of the new society engendered by the revolution” and their going back

ideologically places the spectator in a superior, already better period, that cost the lives

of those who fought,

The revolution is seen as the painful birth of a new generation of families who

are able to live in the more just and equitable society envisioned and created by

17

those who came before. As a result, Flor silvestre is able to affirm the traditional

values of the melodrama –the family and the fatherland – at the same time that it

affirms radical social changes, for the painful transitional phase is set in the past

and is shown to contain the seeds of a new and better present.

Mistron, quoted in Noble, 2005: 60

By the 1940s the revolution had “undergone a process of institutionalisation and

passed into the domains of collective memory” (Noble, 2005: 49) and films like

Fernández’s contributed to the prevailing of the specific values promoted by

governmental policies, that included as well the exaltation of Indians in a poetic way that

placed them in a distant, sacred place where they do not interfere with the prevalence of

the new mestizo and modern order, as in María Candelaria (1943).

1.4. Ideology and the allegories of Mexicanidad

Many critics have studied the ideological impact of the Mexican film industry of

the classic period and the ways it managed to cluster a number of ideological precepts

that endorsed the preservation of the political and social post-revolutionary order. In

their essay Intimate Connections: Cinematic Allegories of Gender, the State and

National Identity, Alex M. Saragoza and Graciela Berkovich (1994), analyse the

melodramas Salón México, Nosotros los pobres, and Flor Silvestre as documents of the

conservative ideology of the Mexican state, exploring the ways in which they presented

the official version of history through the affirmation of stereotypes, archetypical

characters that reinforced the prevalence established order.

Saragoza and Berkovich argue that Mexican films often mediated the textual,

political and economic relationships between the state and national identity through the

transmission of gendered allegories, (Saragoza et al 1994: 25), though not necessarily

through the explicit involvement of the Mexican state in the film industry but via an

implicit consensus between the state and the audience, whereby a discreet delineation of

typified familial and gender roles emerged as a common referential network of signs that

18

was unquestionably accepted. This accepted status quo promoted the development of

particular genres and cinematic formulas constituted the paradigm of Mexican cinema,

composed primarily of simple plots with standard endings that idealised the family and

endorsed traditional morality through archetypical representations of gender roles.

(Saragoza and Berkovich, 1994: 27)

This ideological consensus not only helped maintain the State’s hegemonic

influence in the many aspects of private and public life, but with its accomplishment, it

also helped to dilute, if only in the imaginary, the strains caused by the country’s

multilayered and despaired social composition. In this way, Mexican cinema insistently

portrayed a society that lived harmoniously in despite differences across gender, class

and ethnicity whereas promoting their inexorable immobility.

As Saragoza and Berkovich, other scholars have argued that the essential

allegories that allowed this mechanism lie on the way the family, the economic system

and the roles of women and men were represented.

In Mexican films, the ubiquity of melodrama made somehow easy to reproduce

these allegories in the different cinematic styles, namely comedies, period films and

even adaptations of novels or plays. Ideology, argues Ramírez Berg, (1992) reveals itself

in each of these archetypes, and its projection of the key issues of mexicanidad reveal

the conflicting nature of Mexico’s history as well as of its social composition.

The following is a description of these archetypes and the way they functioned as

carriers of ideology as identified by Ramirez Berg (1992, 1994), Hershfield (1996) and

Saragoza and Berkovich (1994). This theoretical framework will allow for the analysis

of the films in chapter three and also as an outline of the aesthetic and ideological

platform to which Luis Buñuel adapted at his arrival to the Mexican film industry.

• Family, the patriarchal institution

The family is the basic unit of society. It is the mediation between the state and

the individual, and therefore the place where all forms of socialisation of the

members of a nation are moulded and individual roles of men and woman are

defined.

19

In Mexican cinema, family is the microcosm of society, where patriarchal

authority is unquestioned and absolute, even when it is exercised unjustly.

Patriarchal rules are passed on from generation to generation as men grow into

manhood.

It is within the universe of the family that all the values of Mexican-ness are

engendered and guarded. This is better exemplified by films as Cuando los hijos se

van (Juan Bustillo Oro, 1941), but the same features are respected and can be read

implicitly in almost every Mexican melodrama.

• Capitalism

The economic system in Mexican films was usually portrayed as a given and

unalterable fact. Seen as inherited manifestation of the post revolutionary government, it

is the ultimate force by which all characters’ lives is governed. In many cases he system

can be read as the ultimate antagonistic force that prevents the characters of achieving

happiness for it puts pressure on individuals, who must live by the norms of an

inherently flawed system “Mexico’s capitalistic status quo”, argues Ramírez Berg, is

“automatically suspect, for the system is the result of a bloody revolution that was

supposed to reform Mexican life yet changed little” (Ramírez Berg, 1995: 22)

• Class

An insistent message of social stasis runs under the classic paradigm of Mexican

films. The lower class is portrayed as the ultimate bearer of mexicanidad, and money is

best understood as a corrupting force: there are all sorts of troubles if the working class

can expect it consorts with the upper class or aspires to rise in class stature. “Such

messages suggest not only that the Poor should stay where they are in order not to lose

their humanity and the ability to care and feel for others, but also they must accept the

status quo in order to maintain “legitimate mexicanidad.” (Ramírez Berg, 1995: 25)

• Machismo

Reinforced by the patriarchal institution and metonymically also by an ideological

agreement with the state, machismo is an entrenched social-sexual tradition in

20

Mexican society in which the figure of the male is always associated to a position of

power and the endorsement of masculinity. On the ideological level, the male

receives a secure identity and the state receives his allegiance; the male gains a

favoured place in the patriarchal system while the state accumulates political might.

• Women

Derived from the outline given by the patriarchal family, women in Mexican

cinema –and in Mexican imaginary, exist only to give pleasure to men. Their

representation is always inscribed in the paradoxical virgin-whore paradigm, only in

the Mexican case, the concept has unique characteristics because of the additional

“expectations tradition and history have placed upon Mexican women” (Ramírez

Berg, 1995: 23), for women are expected to be not only virginal, but ‘Virginlike’

“emulating the Virgin of Guadalupe, the spiritual patroness of Mexico” (Ibid) and in

counterpart, the whore refers to the historical figure of La Malinche, the Indian

princess who worked as interpreter for Cortés and who is considered the ‘primordial

traitoress’ of Mexico, who sold out her people to the Spanish conquerors. “Because

of her, Paz and others have argued, feminine sexual pleasure is linked in the

Mexican consciousness not only with prostitution but with national betrayal.

(Ramírez Berg, 1995: 24)

To avoid being perceived as a traitor, a woman must remove herself from the

sphere of sexual pleasure. In Mexican movies –and in Mexican life—the most

common nontreacherous role is that of the asexual, long-suffering mother.

21

Chapter two Luis Buñuel in Mexico

2.1. Antecedents of Luis Buñuel’s Artistic Trajectory

Luis Buñuel is one of the most important figures in the history of cinema. He is

director of a series of very personal films in which it is evident the influence of the

surrealist movement and most crude Spanish realism. Born in Calanda, in the province

of Teruel at the beginning of the twentieth century, Buñuel was son of a rich ‘Indiano’

who had made his fortune in Cuba. He received a Catholic education with the Jesuits of

Zaragoza just before leaving for Madrid, where he dwelled at the “Residencia de

Estudiantes”, the student’s resident where also lived poet Federico García Lorca, painter

Salvador Dalí and other people who would later be outstanding intellectuals or artists of

the so-called “Generación del 27”. Seduced by avant-garde poetry (i.e. creacionism and

ultraism, an interest that would always be with him and that would be fundamental for

his approach to cinema), he published some poems and prose before turning into cinema,

after having been impressed by Fritz Lang’s Der Müde Tod. In 1925 he moved to Paris

where he had the chance to collaborate as film critic for publications in both Paris and

Madrid, leaving stated like this, a few cinematographic concepts and considerations on

the medium that later on his life would refuse to express.

Attracted by the surrealist movement, he gathered with Salvador Dalí to write the

script of Un Chien andalou (1929), a film hat would give him entrance to the group. The

film, financed by the director’s mother, received eloquent praises by intellectuals and

filmmakers of the Parisian scene and beyond like Russian director Eisenstein. Thanks to

this success he managed to get sponsorship from a couple of aristocrats for his next film

L’Age d’or (1930), the film that portrayed the delirium of amour fou so much praised in

the surrealist circle and whose blatant anticlericalism and denounce against social

hypocrisy provoked intense polemic in the Paris of the time. The film’s contents and the

public’s reaction are examples of what would accompany Buñuel throughout his career.

22

In one way or another, Buñuel’s films would always come back to this primordial couple

that is driven by the desire of getting together but stopped continuously by moral,

religious and social norms, on the other hand, this was not to going be the last time one

of his films raised polemic and scandal.

His fame caught the attention of Hollywood producers, who offered him a sort of

internship at the Metro Goldwyn Mayer studios, where he was supposed to observe and

learn the techniques of studio filmmaking. He did learn, but also found no interest on it.

Rapidly bored, Buñuel went back to Spain after a while, where he shot the gripping and

strongly criticised documentary Las Hurdes, tierra sin pan (1932). Banned by Spain’s

new republican government, Las Hurdes is considered pivotal in the career of Buñuel,

for it is a film that combines elements of surrealism (embedded in the film’s fatalist

narrative) with stark realism and bleak treatment of facts.

Buñuel continued working in Spain as a dubbing supervisor for Paramount and

Warner studios and held an executive position in Filmófono, a state-fund producing

company that attempted to give boost to Spain’s film industry with commercial quality

filmmaking. He produced several films and supervised the direction of others (among

which Don Quintín el amargao, 1935), but the project was interrupted with the outbreak

of the Civil War.

In 1938 Buñuel immigrated to the United States where he worked as a film editor

for the New York Museum of Modern Art. His job consisted of cropping and assembling

documentaries for war propaganda. In 1942 he was fired because of rumours concerning

his previous allegiance to the Communist party in Paris, and more explicitly, because his

employers learned that he was the author of L’Age d’or. Unemployed and without

having worked as a director for almost fifteen years, he accepted the proposition of

Mexican producer Oscar Dancigers to direct a couple of films in Mexico. He moved

south then, and in 1946 shot Gran Casino (1947) starring Jorge Negrete and Libertad

Lamarque, two of the most renowned stars of the then flourishing Mexican film

industry. The film was a financial failure, but Buñuel stayed in Mexico living on a

monthly allowance sent by his mother. Almost three years later, Buñuel was appointed

another film by Dancigers, El gran calavera (1949), a family melodrama that was a

large box-office success and marked the beginning of a long list of films made against

23

time, with appointed scripts and imposed actors, what Buñuel would call “películas

alimenticias” (bread-and-butter films) and that make up the majority of his Mexican

filmography.

In 1950 he directed Los olvidados a film for which he enjoyed absolute creative

freedom as he had not had for a long time. After the commercial success of El gran

calavera, Dancigers proposed Buñuel to make a ‘real film’ and allowed him total liberty

to search for the subject. Buñuel already had it, though his project did not intend to be

much more than a conventional melodrama. With writer Juan Larrea, he had written a

script entitled ¡Mi huerfanito jefe! (My orphan boss!), about a street boy who sold

lottery tickets. Dancigers liked it but was willing to go for something more serious and

proposed Buñuel to write a script about Mexico City’s poor children. (Aranda, 1969:

188)

Buñuel liked the project, during his first years in Mexico he had walked the

streets of the city, observing the lives of the marginalised that dwelled in Mexico City’s

slums. He began a deeper investigation and gathered some real stories from the

reformatory to write the script. The collaboration of Spanish writer Jesús Camacho

(better known as Pedro de Urdimalas) was essential for the portrayal of the typical urban

speech of Mexico City. Urdimalas had written the characteristic dialogues that

determined much of the success of urban comedies like Ismael Rodríguez’s Nosotros los

pobres (1948) and Ustedes los ricos (1948)

From then on, Buñuel’s career would alternate between personal projects and

appointed assignments. In both cases he developed a personal style that explored

different themes and stories within the realm of melodrama, as well as an ability of

directing at an incredibly fast rhythm, one film after another with extreme efficacy. He

directed 21 films; among the most renowned of this first period are, Susana (1950), Él

(1920), Abismos de pasión (1953), La vida criminal de Archibaldo de la Cruz (Ensayo

de un crimen) (1955) and Nazarín (1958); less famous but of considerable commercial

success within Mexico were Subida al cielo (1951) and Una mujer sin amor (1951) and

La ilusión viaja en tranvía (1953).

Buñuel made two films in the United States with the collaboration of Hugo

Butler Robinson Crusoe in 1952 and The Young One in 1960. The latter, made under the

24

production of George P. Werker, tells the story of a black man that, after having been

unjustly accused of raping a white woman, seeks refuge in an island in the Mississippi

River where a young girl and her racist guardian live. The film received bad criticism in

the United States because of its ambiguity in dealing with the issue of racism; it is,

however, one of Buñuel’s subtlest portrayals of human nature, with the characters

moving back and forth in the realms of guilt, violence and desire.

In 1961 he directed a film in Spain for the first time in 30 years. The shooting of

Viridiana was permitted by the Francoist government, in an attempt to please the

international criticism to the regime’s censorship policies. Nevertheless, when the film

was released, the religious authorities were scandalised and demanded Buñuel’s

excommunication, the Spanish government abducted the film from its circulation in

Spain and only a few copies that were circulating abroad were saved. It was awarded the

Palm d’or in Cannes in 1962.

Buñuel would direct two more films in Mexico: El ángel exterminador (1962),

and Simón del desierto (1965). The former is considered one of the most acid critiques

to the bourgeoisie, and it has been widely praised by critics and international audiences.

The film is indeed a delirious portrayal of the hypocrisy of social norms in a feast of

entrapment and desire, full of inexplicable repetitions and surrealist situations that build

up in a crescendo and burst in a final sarcastic laugh.

Simón del desierto, a film based on the story of Simeón el Estilita, a Syrian

ascetic who stood on top of a column with no food or water and as thought to perform

miracles, received attention and applauses for its irreverence and iconoclastic portrayal

of religious symbols, though its fame also comes from the difficulties experienced at the

time of the shooting. The budget was cut out in the middle of the shooting and many of

the scenes had to be left out, in the same way, the film had to do without several effects

and especial features, reason for which it is considerably short and the ending comes in

quite abruptly, it is, nevertheless, one of Buñuel’s best finales.

This episode symbolically closes the Mexican stage of Buñuel’s career, a period

in which low budgets, time shortages, imposed scripts and actors were the norm, A

phase in which Buñuel pulled out outstanding works in despite of the permanent

practical difficulties and inconvenient conditions. As stated in an opportune comment by

25

Francisco Sánchez (quoted by Sánchez Vidal, 1984), the episode shamefully falls on the

inefficacy of the decaying Mexican film industry,

El director que había realizado Viridiana, nada menos, era tratado en su país de

adopción como si fuera un director aficionado. Como que no había derecho. Si a

Alatriste se le acabó el dinero, ¿no hubo en toda la asociación mexicana de

productores nadie que le entrara al relevo? ¿El talento de Buñuel no tenía aún

crédito en el Banco Nacional Cinematográfico?

Sánchez Vidal 1984: 286

[The director that had directed nothing less than Viridiana was being treated in

his adoptive country as an amateur. There was no right. If Alatriste had run out of

money, was not there anybody in the whole Mexican Association of Producers to

help him out? Did not Buñuel’s have yet credit in the Banco Nacional

Cinematográfico?]

From 1963 Buñuel began shooting in France, where he would work with

considerably larger budgets than in Mexico and with total creative freedom. Belle de

Jour (1963) is his first French film of the latter period, to it would follow La Voie lactée

(1969), Tristana (1970), Le Charme discret de la bourgeoisie (1972), Le Fantôme de la

Liberté (1974) and Cet obscur objet du désir (1977), his last film. He died in Mexico

City on the 30th of July 1983.

2.2 Luis Buñuel and the Mexican Film Industry

When Buñuel arrived to Mexico in 1946, the Mexican film industry was on its

highest peak and about to start its rapid decline; after the end of the war, with the

support of Hollywood studios cut out, Mexican film industry lingered on “protectionist

laws, semi-obligatory exhibition, attempts to form a monopoly which would finally

become a State monopoly, a production based on stereotypes and an organization that

excludes renovation in all its aspects” (King, 1995: 129).

26

So it meant that the industry in which Buñuel came to work, as offered by Oscar

Dancigers was beginning to be less an industry and more a series of aesthetic and

bureaucratic impositions that moreover had to be followed without the incentive of

monetary gratification. The panorama could not be bleaker for the director, who not only

found himself working with actors whose huge ego interfered with his work, but also

with strong monetary restrictions and very little time for shooting.

The major factor sustaining such a movie industry was the “star system”

Mexican producers and directors were indeed fortunate in that during the 1940s

and 1950s a fortuitous confluence of talented, charismatic, and attractive

performers appeared who could assure commercial success for even the worst of

films., The problem with this was that a motion picture became a vehicle for the

star and consequently the director and the script became of secondary concern.

Mora, 1982: 75

Despite these difficulties Buñuel directed 21 films in Mexico. These films have

been difficult to place both in the context of the Mexican cinema industry and in the

trajectory of his career. On the one hand, critics of Buñuel’s work at the time did not

expect his trajectory as an artist to take a turn on commercial filmmaking, and many

considered it to be “a decline from the excellence of his early work” (Aranda 1975: 146)

and on the other hand, his status as an artist did not allow his work to be considered

thoroughly part of Mexican national cinema, and it is seen to have remained separated

from the dominant modes of Mexican film industry, even though in most cases he

explored and exploited the genre of melodrama and adapted to the formal structures that

were already a routine in the Mexican cinema industry.

Present in his Mexican filmography are, moreover, the typical elements that

made up the billboards of Mexico and most of Latin America and Spain: urban comedy

(La ilusión viaja en tranvía, El gran calavera), rural and ranchera comedy (Gran

Casino, Subida al cielo, El bruto), or family melodramas (La hija del engaño, Una

mujer sin amor, Susana), within which we also find the usual stylistic attributes that

27

these kind of films contained: musical numbers, typified characters and a plethora of

happy endings.

Buñuel’s adscription to the looked-down genre of melodrama and commercial

filmmaking caused that for many years the critics left his so-called “minor” works in

oblivion. Not until recently has the situation changed, due to the revision of the

importance of melodrama as a mode of cultural representation, after being for so long

“accused of complicity with suspect ideological structures” (Noble 2005: 97) and

condemned by critics for several years, who perceived it as “excessively sentimental,

escapist form of entertainment that appealed primarily to an ‘uncultured’ mass

audience”.

Recent studies of Buñuel’s work in Mexico, for example, analyse these films

searching in them the elements in which Buñuel appropriated and transformed the forms,

structures and conventions to the genre. Peter Evans, in his important study The Films of

Luis Buñuel. Subjectivity and Desire, (1995) analyses a number of Buñuel’s melodramas

within this framework, acknowledging Buñuel’s keeping of authorial control but

underlining the fact that they do adapt to commercial and generic demands.

Buñuel’s films, he says, “managed to appeal to both large and minor audiences

through form, sexuality, humour and irony […] reworking the auterist thematics through

the patterns and drives of the popular cinema” (Evans 1995: 38)

A similar approach is taken by Spanish critics Pablo Pérez and Javier Hernández

in the article Luis Buñuel y el melodrama. Miradas en torno a un género (1995), who

argue that Buñuel preferred the genre of melodrama as a medium to portray passionate

characters and stories that could have well been taken out from the Spanish folletín,

another “género chico” which the director was also fond of. They also argue, however,

that Buñuel’s use of melodrama was always consciously stripped of its coarse

sentimentality. Avoiding over-sentimental devices such as close-ups or sympathetic

musical backgrounds, Buñuel kept control of his films even though they are populated

by characters that can be easily stereotyped: (“Susana, la chica descarriada, Don Quintín,

el hombre derrotado por el falso orgullo, el bruto de buenos sentimientos” (40) [Susana,

the stray girl, Don Quintín, the man defeated by false pride, the tough guy with good

feelings]). Pérez and Hernández argue that these films do not pretend to mock the genre

28

of melodrama, instead, Buñuel used its elements as an excuse to tell stories impregnated

of his personal sense of humour and point of view.

From these considerations we can observe how the constant flow of Buñuel’s

work, between the limits of high art and lowbrow products, has made it quite

uncomfortable to place and define in the context of Mexican cinema. Whilst his

presence in Mexico was fundamental, whether he followed the established conventions

of commercial cinema or not, his work is said not to have influenced the trajectory of

Mexican filmmaking outside a few selected circles, and his films were often not fully

appreciated, as was the case of Los olvidados, a film that was initially rejected in

Mexico, both by the critics and the government, who considered “offensive” that a

foreigner would make such bleak portrait of Mexico City’s Poor, whilst Mexican cinema

sacred directors like Ismael Rodríguez could made them look endearing and funny, even

photogenic, as in Nosotros los pobres (1948); in return, it was openly welcomed after it

received the Palm d’or at Cannes Film Festival, it rerun in important venues and

received official recognition. Los olvidados is, nevertheless, looked upon as more a

Buñuelean film than a Mexican one.

The exceptionality of Buñuel's work in the context of Mexican cinema has

provoked that scholars of this national cinema tend to leave him out from their

historiographies on the evolution of the cinema industry and the cinematic styles in

Mexico. Mexican film critic and scholar Jorge Ayala Blanco deliberately leaves out the

whole work of Luis Buñuel from his extensive Aventura del cine mexicano (1968),

arguing that “el cine del gran realizador español de ninguna manera puede integrarse al

desarrollo del cine mexicano y nunca ha conseguido modificar su trayectoria, apenas ha

influido sobre algunas películas muy escasas” (Ayala Blanco 1968: 10) [the cinema of

the great Spanish director can in no way be included in the development of Mexican

cinema and has never influenced on its trajectory, if only on very few films] This is to

say that in a way, Buñuel’s ‘major’ films are considered a rarity among the mass of

productions that were made in Mexico on that period, and as a rarity, they did not

influence much in the development of the style and features of commercial cinema.

Ayala Blanco goes even further, to close the argument: “Si se prefiere la hipérbole, este

libro quiere responder afirmativamente a la pregunta: ¿queda algo valioso en el cine

29

mexicano si quitamos a Luis Buñuel?” (11) [If we prefer the hyperbole, this book

intends to respond with a yes to the question ‘is there anything worthy left in Mexican

cinema if we take out Luis Buñuel?’]

This statement casts light on the fact that, when compared with the attention

given to the director by the international critics, Mexican cinema often passed

overlooked. The same situation occurred in the case of Spain, the director was

considered to be the only representative, even though he did not make a single film there

between the years of 1935 and 1963. In her essay Exile and Ideological Reinscription:

The Unique Case of Luis Buñuel (1993), Marsha Kinder argues how it is this condition

as lifetime exile what contributes to Buñuel’s frequent recognition as the only

representative of Spanish cinema abroad (Kinder, 1993: 279), an assumption that creates

the myth of a country “in which changes never occur” (291), freezing as well the image

of the director: “it ignores the fact that although he was always subversive he was also a

powerful shifter whose meaning changed according to which particular hegemony he

was working against –Francoism, Catholicism, or Hollywood” (291) and we might as

well add here “or Mexico’s hegemonic film industry” for just the same could be argued

of the director’s case in Mexico.

This is perhaps the essentialist perspective that Ayala Blanco wishes to avoid,

implying with his words that, for better or worse, Mexican film industry, and Mexican

films, though not as appealing for international critics (but what mainstream films are?)

did develop, shift and evolve, even if not necessarily influenced by films as Los

olvidados or El ángel exterminador, but perhaps in despite of them.

2.3 Buñuel’s Mexico: Cultural Encounters and Continuities

Buñuel produced most of his films as an exile, but the roots of his humour,

absurd and brutal at times, his detailed, almost morbid analysis of established morality

and the bourgeoisie, his obsession with religion, eroticism, death and the miseries of the

human kind are to be found in Spanish realism (Quevedo, the picaresque novel, Goya

and Valle Inclán) features that Buñuel would combine with his constant surrealist optic.

Both influences flourished and mingled with the different environments to which he was

exposed. His contact with Mexico’s culture, its politics and its conflicting social

30

composite, gave him matter for the exploration of new themes and the development of

incisive projects in which he imprinted his distinctive personal style. We have argued above that Buñuel’s Mexican films have enough elements to be

considered representative of the Mexican film industry. In the same way, we cannot

categorically exclude a consideration of authorial intervention in the case of Buñuel for,

even when mainstream films are circumscribed by ideological constructions, the author

reserves a level of authorial control whereby his personal universe permeates the content

and the form of this work, no matter whether that work was an appointed task or a

personal project.

In the same way, this universe was in many senses constructed by the artist’s

particular condition as an exile. Buñuel, according to Víctor Fuentes was both an exile

and an outsider to the industry of commercial filmmaking. “When arriving to Mexico”

he argues, “the director fought tirelessly on two fronts: on the first to make a poetic,

personal cinema […] and on the second to project his personal and cultural vision on the

commercial cinema within which he was working” (Fuentes 1995: 162).

This is not to imply that Buñuel did not enjoy making those commercial films or

that they lack of the director’s personal sensibility, but that in trying to convey his

sensibility, he had to establish a dialogue with different forms of expression from those

with which he had worked previously. In this dialogue Buñuel reworked the conventions

of a national cinema to produce films that fulfilled his artistic needs.

As an exile, Buñuel was a “unique case”. Out of his natal Spain most of his life,

the whole of his career took place virtually somewhere else, yet the traces of a constant

quest for what is Spanish, can be found in each one of his films. To Marsha Kinder,

Buñuel’s work is characterised by the director’s perennial condition as an outsider, what

results in a certain “indeterminacy”- the result of a series of exiles and reinscriptions into

different cultures. Kinder argues that the “discourse of the exile resists the cultural

‘melting pot’ both in the old and new lands; it retains its Otherness in both contexts.”

(Kinder, 1993: 279)

Both Kinder and Fuentes agree on the fact that Buñuel’s condition of permanent

exile was determinant for the particular representation of the culture of the new country

in his films. On the one hand, Marsha Kinder underlines as pivotal factor Buñuel’s

31

insistency on the portrayal of the clash of social classes and gender, this is the result of a

“cultural continuity”, that of the history of longstanding oppression and violence shared

by Mexico and Spain, “the colonial past is represented in Buñuel’s constant use of social

and class differences” (Kinder, 1993: 301)

It is evident that this history is also represented by the figures of authority and

submission that are constant in Buñuel’s films either explicitly or implicitly, and we

would add here that this is because the inquisitive gaze of the outsider did not fail to

notice that much of that colonial past authoritarian legacy was still present in the 1950s,

and perhaps still is.

For Víctor Fuentes the cultural reinscriptions of the exile are to be read

differently in the different stages of the process of assimilation of the exile to the new

culture. The process begins with the exile passing through a period of resistance slowly

moving into a subsequent one of assimilation, to eventually reach the position of

“transterrado” –an exile that is still an outsider but manages to express specific

characteristics of his new country. Fuentes’ position rounds the edges of what Kinder

expounds: in a first stage of his exile, Buñuel made efforts to infuse the ‘counterpoints’

of Spanishness in the melodramas he was making, starting from the Spanish literary and

theatrical tradition in an attempt to go back to his roots by recreating the myth of

Spanish identity, an effort that came as a result of the crisis of national identity that not

only Buñuel but also his conational also exiled in Mexico were feeling at the time.

(Fuentes notes as example of this the desire that from early on Buñuel had of “not only

to take Nazarín to the big screen, but also Doña Perfecta –also by Galdós- Jacinto

Benavente’s La Malquerida and Carlos Arniches’ El último mono.) (Fuentes 1995: 162)

Buñuel did remake Don Quintín el amargao in Mexico, a film he had produced

in 1935 in Spain when working for Filmófono, and the result gives an interest insight on

how this cultural reinscription took place in both directions.

Don Quintín el amargao is based in the homonymous zarzuela by Arniches and

Estremera, a play of which Buñuel was particularly fond and of which he owned a copy

that he and other Spanish exiles watched frequently “just for fun”. The significant

difference that the Mexican version of the film, La hija del engaño (1951), holds with its

32

Spanish counterpart, though necessary because the film had to be adapted for an

audience that was different both territorially and temporally, tellingly denote how a

strong desire of rewrite their Spanish identity persuaded Buñuel and his collaborators

(Urdimalas and Alcoriza) to adapt the culturally specific genre of zarzuela with its

plethora of jokes based on typical linguistic traits and typical madrilène characters to a

no less culturally specific audiences of 1950s Mexico, and therefore the Spanish humour

that they very much enjoyed had to be modified in the Mexican version, and though Don

Quintín continued to be essentially the same character, instead of the “echao pálante”

madrilène, he became a Mexican macho

The character of Don Quintín does change, however at the end of the Mexican

film. The newer film’s ending makes sure that there are no ambiguities in whether Don

Quintín’s bitterness has been thoroughly shaken off, whereas in the Spanish version, we

can perceive a nervous look, a glimpse of paranoia that hints to what the character of

Arturo Córdova in Él would bring a few years later and tells us that “El amargao” might

as well still be around for a while. The happy ending of the Mexican version is thus

more commercially acceptable; notwithstanding it leaves open the question on whether

familial happiness can be restored once he ties have been so violently torn.

Curiously, some of the best moments of La hija del engaño are not in the

1935 version, and these account for features that are included specifically to address

Mexican audiences: the inclusion of a musical number by Jovita (Lily Aclémar) singing

the bolero “Amorcito corazón” and the hilarious and over-the-top sequence of the rogue

“El Jonrón” to “El Infierno” (i.e. “Hell”, Don Quintín’s casino/cabaret, another common

place feature of classic Mexican cinema and epitome of sin and decadence) pointing his

gun at everyone and creating mayhem with exaggerated macho displays.

The differences between Don Quintín el amargao and La hija del engaño acutely

exemplify Fuentes description of the way the choices of the director are influenced by

his desire to project aspects of his shaded national identity, but they also cast light on the

influence that the cultural specificity of the country of exile delimits and influences this

range of choices since the director, as an exile, had to adapt not only to a new culture,

but to specific ways of representation of that culture. Buñuel’s affection for the popular

Spanish genre is then influenced by his desire to comment on Mexican males proclivity

33

to facile violence, whilst at the same time it functions as an opportunity to introduce an

anticlerical joke by making the priest enter “El infierno” with his cassock buttoned up to

the end.

This is but an example of the ways in which the films of Luis Buñuel were

permeated and enriched from many different stocks. Buñuel’s work in Mexico emerges

therefore as paradigmatic: in the same way as the genius of the artist is composed by the

influences and choices of life, his work cannot be stripped of its cultural specificity. As

seen in the previous example, much of the aesthetic and dramatic choices made by the

director to adapt an old idea were conditioned by the exigencies of the industry. These

exigencies, however, were not to be accounted as negative limitations, but as the

opening of new doors and levels of signification from which to emit a message.

Creativity is a force that finds its way even in the most constricted environments, and

Buñuel’s creativity was evidently not inhibited by these economic restrictions, on the

contrary, as we will see in the next chapter, the director managed to articulate the

integrity of his genius into the apparently flat language of commercial filmmaking,

managing in this way, to attain and reflect the complexities contained in his adoptive

country’s culture.

34

Chapter three Mexico in the Films of Luis Buñuel

3.1 Analysis of Susana, La ilusión viaja en tranvía and El río y la muerte

In the following chapter we will analyse three films of Luis Buñuel through

which we will try to explore the way they account for both “Mexican” and “Buñuelean”

characteristics as has been suggested from the two previous chapters.

The films to be analysed are Susana (1951), La ilusión viaja en tranvía (1953),

and El río y la muerte (1954). They are representative of three types of melodrama that

were typical in the period of the classic Mexican cinema: Susana is a family melodrama

that presents the archetypical devoradora character, the Mexican femme fatale whose

untameable sexuality confronts the familial order and whose best exponent was actress

María Félix in films like Doña Bárbara (Fernando de Fuentes, 1943); La ilusión viaja en

tranvía is a comedy of customs with shades of melodrama, set in Mexico City and

presenting the lives of the urban poor. This is a film closely related to two kinds of films

that enjoyed great popularity during the Golden Age: on the one hand the urban

comedies of Mario Moreno Cantinflas, who made popular the character of “El Peladito”

a poor but honest man, whose humorous appeal was based on a witty use of language

and the ridiculing of the upper classes, (Mexican comedians ever since have been more

or less a reinterpretation of this character) and on the other hand, the set of urban

“weepies” Nosotros los pobres (Ismael Rodríguez, 1947) and its sequels that presented

the predicaments of the working classes of Mexico City, and that marked the rise of

actor Pedro Infante as a national hero (even today he is remembered as “El ídolo del

pueblo”); El río y la muerte is what could be called a ‘serious’ melodrama that deals

with the theme of the confrontation of progress and backwardness as represented by

rural/urban environments that was typical of the modernising official discourse of the

period and that finds its best representative in Emilio Fernández’s Río Escondido (1948),

a film that exalts the educational policies of the governments and portrays progress as

the vehicle to fight the oppression in which the Indian population lived.

The films chosen are also representative of the cinematic styles exploited by

Buñuel during his first years in Mexico. Susana, La ilusión viaja en tranvía and El río y

35

la muerte, are all part of Buñuel’s early work in Mexico. To El río y la muerte would

follow only projects of a more personal nature and also some of his best films, such as

Nazarín and El ángel exterminador.

Above all, these films were addressed to large audiences, they adapt quite

accurately to the conventions of the Mexican cinema narrative paradigm and belong to

the group of films that Buñuel himself called “películas alimenticias”, these three

characteristics are important for the purposes of this work since they allow for the

interpretation of issues of ideology, national representation and cultural interpretation

that we have argued in the previous chapters.

This choice of films allows then for an approximation to the way Buñuel

portrayed the themes that are archetypes recurrently used in Mexican films. As such,

Susana will give us the opportunity to explore the representation of the family as

nucleus of the patriarchal system; La ilusión viaja en tranvía will give material to

explore issues of capitalism and representation of social class and social mobility,

whereas El río y la muerte will provide the opportunity to explore representations of the

male figure, the state and modernising discourses; all three films will also serve to

explore the representation of feminine roles.

A note on the critical approach

As it was stated in the first chapter, classic Mexican cinema favoured the use of a

specific narrative paradigm in which the films of several cinematic styles were inscribed.

According to this paradigm, a number of types and archetypes emerged as standard

forms of representation of specific traits of human interaction, these archetypes

functioned as ideology carriers and in this way, Mexican cinema managed to convey a

message that promoted nationalism, social stasis and the prevalence of a paternalist state

through the reinforcement of the values of the patriarchal family and the subsequent

gendering of the roles of its members.

As a starting point of our analysis, we have decided to search for these

archetypical elements in the films of Luis Buñuel, in order to see the extent until which

they adapted and used the established economy of signs, to this follows a further