MEMOIRS OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM BRISBANE © Queensland Museum PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone 06 7 3840 7555 Fax 06 7 3846 1226 Email [email protected] Website www.qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 0079-8835 NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum maybe reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the Editor in Chief. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed at the Queensland Museum web site A Queensland Government Project Typeset at the Queensland Museum

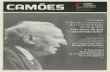

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

MEMOIRS OF THE

QUEENSLAND MUSEUM BRISBANE

© Queensland Museum PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia

Phone 06 7 3840 7555 Fax 06 7 3846 1226

Email [email protected] Website www.qm.qld.gov.au

National Library of Australia card number

ISSN 0079-8835

NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the

Queensland Museum maybe reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the Editor in Chief. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop.

A Guide to Authors is displayed at the Queensland Museum web site

A Queensland Government Project Typeset at the Queensland Museum

HMS PANDORA PROJECT — A REPORT ON STAGE 1: FIVE SEASONS OFEXCAVATION

PETER GESNER

Gesner, P. 2000 06 03: HIV1S Pandora project — a report on stage 1: five seasons ofexcavation. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, Cultural Heritage Series 2(1): 1-52.Brisbane. ISSN 1440-4788.

In 1790 the Pandora, a 24 gun frigate sailed from England to Tahiti in pursuit of the Bountyand its mutineers. After capturing some mutineers, the Pandora was wrecked in 1791 on itsreturn voyage attempting to navigate the Great Barrier Reef, east of Cape York Peninsula,Australia. The survivors sailed in an open boat from the Barrier Reef to Java and eventuallyreturned to England, where the mutineers were brought to trial. The discovery of the Pandorashipwreck in November 1977 and its' subsequent archaeological investigation by theQueensland Museum constituted an opportunity to expand on the Bounty saga and reconstructits material setting.Between 1983 and 1995 the Queensland Museum conducted exploratory excavations andsurvey over five field seasons, as a precursor to more intensive study. Excavation concentratedon the bow and stern sections where there was well preserved material evidence in the crewsliving spaces and personal storage areas. Maritime archaeology, shipwreck, 1TMS Pandora,Great Barrrer Reef, Royal Navy, HMS Bounty.

Peter Gesner, Museum of Tropical Queensland, 78-102 Flinders Street, Townsville 4810,Australia; 10 November 1999.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

HMS Pandora was a naval frigate dispatchedby the British Admiralty on a punitive voyage tothe South Pacific. Its mission was to find andrecapture HMS Bounty and bring to justice 25men who, in April 1789, had mutinied while theywere on the final stage of a voyage to transplantbreadfruit from Tahiti to plantations in the BritishWest Indies. The leader of the mutiny wasFletcher Christian, the Bounty's acting lieutenantwho felt slighted by his commander, CaptainWilliam Bligh, and, in an outburst of rage andfrustration, incited several members of his watchto take the ship and cast adrift 19 of theirshipmates, including Bligh. Following an un-successful attempt to establish a settlement onTubuai, one of the Austral Islands, the Bounty'smutinous crew fell out among each other fourmonths later. Sixteen mutineers elected to returnto Tahiti in September 1789, after which FletcherChristian sailed off with the Bounty to an un-known destination with eight others and theirPolynesian entourage. In the meantime Blighmanaged to return to England, where he reportedthe mutiny and the loss of his ship to the Lords ofthe Admiralty.

HMS Pandora sailed from Portsmouth in earlyNovember 1790 and arrived in Tahiti 011 23 March1791 after nearly five months at sea on the routearound Cape Horn (Fig. 1). During her six week

stay in Tahiti, fourteen of the Bounty's crew weretaken prisoner and locked up in a makeshiftwooden cell on the Pandora's quarterdeck, whichthe prisoners referred to as 'Pandora's Box'.

The Pandora left Tahiti on 8 May 1791 and,until mid-August 1791, cruised the South Pacificin search of the Bounty and the remainder of hermutinous crew. The search was unsuccessfulbecause Fletcher Christian and his followers hadfound a final refuge on uncharted Pitcairn Island,where they had burned and scuttled the Bounty inJanuary 1790.

On 29 August 1791 the homeward boundPandora was wrecked on the Great Barrier Reefwhile exploring an opening in the reef. Four ofthe prisoners and 31 of Pandora's crew diedwhen their ship sank after striking a submergedreef. Having spent two nights on a small sandcay(Escape Cay) in the vicinity of the wreck, thesurvivors —89 crew and 10 prisoners — set outfor the Dutch East Indies in the ship's boats. Afteran arduous 16-day, 2750km, open boat voyagethey arrived in Timor. They subsequently madetheir way to Batavia (Jakarta). From there theywere able to arrange for a passage home via theCape of Good Hope. At Cape Town the 10 sur-viving prisoners were transferred to a Britishwarship and transported to England to stand trial.Three of the mutineers were hanged and thePandora's officers faced courts martial. No

ENGLAND

HMS Pandoraleft England7th Nov 1790

Arrived Canary Islands r.

22nd Nov 1790

ATLANTI:OCEAN

Arrived Rio de Janeiro31st Dec 1790

•----------------

Pitcairn •^DucieIsland^Island^- • sEaster

s

Island

2^ MEMOIRS OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

FIG. 1. Pandora's route from England to Tahiti.

efforts were made to salvage the Pandora. Thewreck remained undisturbed until its rediscoveryby scuba divers and documentary film makersSteve Domm, John Heyer and Ben Cropp, withthe assistance of the Royal Australian Air Forcein November 1977.

Following an archaeological survey commis-sioned by the Commonwealth Department ofHome Affairs & Environment and carried out bythe Western Australian Maritime Museum'sarchaeologist Graeme Henderson in April 1979,the wreck was positively identified as the Pandoraand declared a protected site under section 7 ofthe Historic Shipwrecks Act, 1976 (Henderson,1979).

Since 1982, management ofthe wreck has beenthe responsibility of the Queensland Museum.Nine archaeological excavations have beencarried out by the Queensland Museum to date,

with additional financial assistance from thePandora Foundation, the CommonwealthGovernment's Historic Shipwrecks Program andthe Queensland Museum's Board of Trustees.These excavations have established that an ex-tremely coherent and well-preserved collectionof artefacts and a substantial portion of the wreckedhull are buried in the seabed (Henderson, 1986;Gesner, 1988; 1993).

The wreck's historical and archaeological valuesunderpin its international cultural significance. Itis a major source of European and Polynesianmaterial culture associated with a British navalvessel engaged on a long voyage to the SouthPacific Ocean in the last quarter of the 18thcentury. The Pandora's last voyage falls within avery important period of European discovery inthe Pacific Ocean, also referred to as the GrandAge of European Pacific Exploration (Howse,1990; Smith, 1992). This period had started

HMS PANDORA: FIVE SEASONS OF EXCAVATION 3

•10^•^• 7•fi^4°

COAST OF NEW SOUTH WALESFROM CAPE TRIBULATION

ENDEAVOUR STRAITS

Shewing TILE LABYRINTHon a Larger Seale

'^(11 fra titsKAT4PI7i.(00 *LIM' 111167

7/4f

45^JO

•fat, n‘ntr.,.././

inn

4t. voz

IL4Z,

112 146'

deburn*

Cape Gee nvAdmil 11

•

Cape Weylnout

t.4,.I 4,5i* eAmofril2t...........

...... •

FIG. 2. Portion of late 18th Century chart of Australia's east coast showing the Pandora's track (upper centre)along the Great Barrier Reef between 26th and 28th August 1791, as laid down by Lt Hayward. (State LibraryNSW #50, Laurie & Whittle)

during the 1760s with Bougainville's voyage,flourished with Cook's three Pacific voyagesduring the 1770s, and La Perouse's epic voyagein the 1780s, and ended with Matthew Flinders'circumnavigation of Australia in 1802. It was thetime when 'enlightened' European philosophersand scientists were rediscovering the world'snatural, cultural and social environments, recog-nising their multifarious forms, and making aconcerted effort to systematically classify thediversity they encountered (MacLeod & Reh-bock, 1988).

The Pandora episode would probably havereceded into historical obscurity but for twoimportant facts. The track which the Pandorafollowed while searching for a passage throughthe Great Barrier Reef and Pandora Entrance tothe Torres Strait was copied onto a late 18thcentury chart of Australia's east coast (Fig. 2).The named features on the nautical charts

became a constant reminder of the fate andlocation of the Pandora.

More importantly however, the story of thePandora's last voyage is one of the three mainstories constituting the infamous saga of themutiny on the Bounty, arguably the most drama-tised and romanticised seafaring saga from theannals of maritime history — certainly an eventwhich became larger than life from the momentWilliam Bligh returned to England in March1790 with news of the mutiny. Following hisreports about the ordeal which he and his loyalcrew had experienced after being cast adrift in theBounty's launch, Bligh was considered a hero.Feted and acclaimed by society, he was applaudedfor his fortitude and leadership. Soon afterwardshe was given command of another expedition,comprising two vessels, HMS Providence andHMS Assistant, to complete the breadfruitcollecting mission he had originally been

4^

MEMOIRS OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

entrusted with when given command of theBounty (Oliver, 1988).

Several years later, however, the accounts ofthe ten Bounty crew brought home as prisoners bythe Pandora's Captain Edwards, cast doubts onBligh's version of events. Bligh's conduct as anaval commander was called into question andhis reputation was subsequently tainted byaccusations made against him by some mutin-eers; particularly by Peter Heywood and JamesMorrison, and by influential members and friendsof Fletcher Christian's family. The ensuingcontroversy fuelled renewed public interest in theBounty saga and resulted in a large collection ofnarratives, travelogues, letters, pamphlets andarticles. Many of these mention the Pandora'srole in the Admiralty's attempt to bring to justicethe Bounty's mutinous crew. Several are bymembers of the Pandora's crew who eagerlymade available their journals and accounts tosatisfy public demand for stories from the SouthPacific; in particular about the infamous mutiny.

Indeed, literature on the mutiny has grown tosuch an extent that a complete catalogue of theBounty saga, including references to the Pan-dora's voyage, would probably contain morethan one thousand entries. The list is still growingas contemporary historians continue to findreasons to analyse and re-interpret the mutiny andits aftermath (Dening, 1992: 397ff).

Thus, the main events of Pandora's last voyageare very well known. The names of the crew aswell as the chronology and sequence of events ofthe voyage can be gathered, not only from suchprimary sources as the ship's log (Adm. 180,Edwards' papers), but also from the publishedjournals, memoranda, eye witness accounts andletters written by Captain Edward Edwards andSurgeon George Hamilton (Thomson, 1915;Hamilton, 1998), by midshipman DavidRenouard (Maude, 1964) and by two of the Bountymutineers, Peter Heywood (Marshall, 1825;Tagart, 1832) and James Morrison (Rutter, 1935).

HMS PANDORA'S LAST VOYAGE

EN ROUTE (PORTSMOUTH TO TAHITI). Severaldays after taking up his command of the Pandoraon 10 August 1790, Captain Edwards wassummoned to the Admiralty in London for abriefing on special orders which would take thePandora into the South Pacific on what was to beher last voyage. The orders included instructions:

... to proceed to Otaheite and, not finding themutineers there, to visit the different groups of theSociety and Friendly Islands, and others in the

neighbouring parts of the Pacific and there seize andbring home in confinement all or some of thedelinquents ... (Adm/A/2831).

The unusual nature of the voyage requiredchanges to be made to the normal complement ofa frigate of the Pandora's class. No marines wereto be taken on the voyage, nor were the officersallowed the usual number of 'servants', i.e.apprentices (see Appendix 1). These berths wereto be filled by additional seamen. An extra lieu-tenant was also assigned and the usual number ofmaster's mates and midshipmen was doubled.These changes to the crew were made inanticipation of the need to provide an effectivecrew to bring the Bounty back to England afterher capture. The length, duration and theextraordinary nature of the voyage also requiredmore than the usual quantity of stores andsupplies to be taken on board. In addition, sparesand new fittings for the Bounty were required.Surgeon Hamilton's metaphor likening the crewto weevils, who first had to eat a hole in theirbread to make a space for themselves, is testimonythat the ship was filled to capacity on departure(Thomson, 1915: 92; Hamilton, 1998: 5).

Among the extra officers added to the Pan-dora's crew was Thomas Hayward, one of theBounty's midshipmen. As one of the 18 crew whodid not go with Fletcher Christian in the Bounty,Hayward had accompanied Bligh in the launchand had served as a witness at Bligh's courtmartial. By assigning Hayward to the Pandora asthe third lieutenant, the Admiralty was actingwith some forethought as they felt his par-ticipation would assist in the recognition of themutineers.

After leaving Portsmouth on 7 November 1790,the Pandora's first port of call was Tenerife in theCanary Islands, where she stayed for several daystaking on water, wine and fresh supplies inludingcitrus fruit, bananas and pomegranates (Thom-son,1915: 93-4).

On the leg between Tenerife and Rio de Janeiro,a large number of the crew, including assistantsurgeon James Innes, suffered from a contagiousfever. It was treated by surgeon George Hamiltonin a novel way by supplying the sick andconvalescent with tea and sugar. According toHamilton this was the first time tea had beenintroduced on a naval vessel at sea (Thomson,1915: 94). In spite of Hamilton's best effortshowever, James Johnson, a bosun's mate, diedduring the Atlantic crossing and was buried at seaoff Rio de Janeiro on 1 January 1791.

HMS PANDORA: FIVE SEASONS OF EXCAVATION^5

Edwards called in at Rio de Janeiro specificallyfor more fresh supplies as he was afraid the feverraging amongst the Pandora's crew would notpass before they reached the dangerous waters offCape Horn. After a short stay in Rio de Janeiro,the Pandora then ran along the coast of SouthAmerica toward Cape Horn. The crew's healthimproved because, according to Hamilton, of thecold weather off the Cape and the availabilty ofspecial supplies, including hot chocolate andspruce beer (Thomson, 1915: 100).

With most of the sick crew rapidly recovering,the Pandora passed Cape Horn without mishapin early February 1791 and after another un-eventful month at sea sighted Easter Island on 4March 1791. The voyage would certainly havebeen very different if Captain Edwards hadrealised that Pitcairn Island, the elusive Bountymutineers' final refuge, was within a relativelyshort sail of Easter Island. However, the fate ofFletcher Christian and his followers was toremain unknown until 1808 when the crew of theAmerican whaler Topaz put in at then unchartedPitcairn Island and met John Adams, the solesurviving mutineer, and the descendants of hisformer shipmates and their Polynesian entourage.

Several more islands were sighted to the westof Easter Island and their position duly recordedin the Pandora's log (Thomson, 1915: 88).Edwards named one of them Ducie Island afterhis patron Admiral Lord Ducie, under whom hehad served as a junior officer and to whose in-fluence he probably owed his current command.But because exploration and cartography werenot a priority, Edwards ignored the islands andcontinued on directly to Tahiti.

AT TAHITI: CAPTURING THE PRISONERS.By heading directly for Tahiti, Edwards wasactually giving effect to his orders to make aTahitian landfall as soon as possible. The reasonfor this urgency lay in the Admiralty's hopes thata sailor called Jonathan (or John) Brown wouldbe able to provide information on the location ofthe mutineers. The Admiralty had received areport that Brown had been put ashore fromanother ship (the Mercury) which had visitedTahiti in 1789. Edwards mentions this in hisjournal when recounting what happened immed-iately after the Pandora's arrival in Tahiti:

Jno. Brown, the person left at Otaheite by Mr Coxof the Mercury, and from whom their Lordshipssupposed I might get some useful information, hadbeen under the necessity for his own safety to associatewith the pirates ... I entered Brown on the ship's booksas part of the complement and found him very

intelligent and useful in the different capacities ofguide, soldier and sailor (Thomson, 1915: 30).

The Mercury had visited Tahiti in August 1789.Several weeks later Captain Cox had in fact comevery close to finding all of the mutineers — aswell as the Bounty — when the Mercury hadpassed the mutineers' first refuge on Tubuai in theAustral Islands. Fortunately for the mutineers,however, the Mercury passed at night, andalthough fires were sighted ashore, Cox did notbother to investigate. While at Tahiti, Cox hadheard of the return of Titreano — the Tahitians'name for Fletcher Christian — in the Bounty,without Bligh (Dening, 1992: 92-4). The storyhad puzzled Cox; perhaps he suspected that themutineers were at Tubuai but considered he wasin no position to act. He waited until he was inEngland to inform the Admiralty (Mortimer, 1791).

Within hours of the Pandora's arrival inMatavai Bay on 23 March 1791, five mutineersgave themselves up. The Bounty's armourerJoseph Coleman was the first to surrender. Hisexample was followed soon afterwards by twomidshipmen, George Stewart and Peter Heywood;then by the Bounty's barber Richard Skinner andthe nearly blind ship's fiddler Michael Byrne.Two days later three more seamen, ThomasEllison, Charles Norman and James Morrison,also surrendered. Morrison, Ellison and Normanhad spent their time on Tahiti with several othersbuilding a schooner in which they had had hopesof sailing for the Dutch East Indies. One of thePandora's midshipmen, David Renouard, recountshow the mutineers with much perseverance, hadbuilt a boat:

... handsomely shaped of about 18 tons which they hadnamed Resolution, to underscore their determinationto use it as a means of escaping from Tahiti (Maude,1964).

However, not all of the mutineers gave them-selves up. Several managed to elude thePandora's men by sailing off in the Resolution.But Brown informed Edwards that they had takeninsufficient water with them and would thereforeprobably soon return to the Papara district. ThePandora's launch and pinnace were sent toPapara and within a few more days another fourmutineers were captured. The remaining two,who had fled to the mountains, were finallycaptured as a result of information provided byBrown. By 9 April 1791 all of them, 14 in total,had been brought on board. This accounted forthe 16 Bounty crew left behind on Tahiti, asEdwards was given credible reports about thedeath of 2 others before the Pandora's arrival.

6^ MEMOIRS OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

Captain Edwards confiscated the Resolution.After the boat was supplied with canvas sailsfrom the Pandora's stores, she was renamed theMatavai and officially commissioned as thePandora's tender. Crewed by a master's mate(William Oliver), a midshipman (David Renouard),a quartermaster (James Dodds) and six ableseamen, she was to be used for inshore recon-noitering of the islands yet to be searched.

Some of the prisoners protested that theirTahitian friends had prevented them from givingthemselves up. According to Morrison:

Tommaree told us we must go to the mountains andkeep away from the ship. When we refused he said: Iwill make you go! And his men seized us and wasproceeding inland with us. (Rutter, 1935: 120).

This should not be considered as a lame excuse;several of the Tahitian tribal leaders whom themutineers had befriended, had a vested interest inthe Bounty men. Association with the mutineersgave them access to firearms for use againsttraditional enemies or rival leaders. Indeed,Charles Churchill and Matthew Thompson, 2 ofthe 16 Bounty men originally left behind on Tahitiby Fletcher Christian, had died as a result of theirinvolvement in local power struggles (Thomson,1915: 110).

The 14 prisoners were initially confined underthe quarterdeck in leg irons pending completionof a special prison cell, which Captain Edwardsordered to be built on the quarterdeck. This woodencell was soon referred to by the prisoners asPandora's Box. It was 11ft x 18ft (3.5m x 5.5m)on the deck and not quite high enough for ThomasEllison — at 5'3" (1.57m) the shortest mutineer

to stand straight in (Rutter, 1935: 123) (Fig. 3).The building of Pandora's Box took more than

one week and was only one of many tasks thePandora's crew occupied themselves with whileat Tahiti. They overhauled the Pandora's riggingand properly fitted out the schooner Matavai.Thus, the Pandora stayed at Tahiti for severalmore weeks before resuming the search for theBounty and the mutineers still at large.

During this time Captain Edwards interviewedthe prisoners as well as a number of Tahitianleaders to get information about the likely where-abouts of Fletcher Christian and the othermutineers. He also tried to get a clearer picture ofthe events which had occurred on the Bounty afterthe mutiny. In this he was aided by the journalsthe captured midshipmen, Stewart and Heywood,had kept. These had been found in the mutineers'sea chests, which Edwards had confiscated aftertheir capture. He also interviewed several

prisoners on specific points in an effort to find outabout what had happened since the 14 prisonershad arrived back on Tahiti and, most importantly,where the Bounty may have gone to since then(Thomson, 1915: 34).

It is interesting to compare the comments aboutthe prison cell made by the gaolers, CaptainEdwards and surgeon Hamilton, with thecomments made by prisoners Heywood andMorrison. Not surprisingly they have oppositeperspectives and emphasise different aspects.Edwards reasoned that he:

... put the pirates in a round house ... for their moreeffectual security, airy and healthy situation, and toseparate them from and to prevent their having anycommunication with, or to crowd and incommode theship's company (Thomson, 1915: 34).

Hamilton relates that the cell was built so thatthe prisoners would:

... be secure and apart from our ship's company; andthat it might have every advantage of free circulationof air, which rendered it the most desirable place in theship. Orders were likewise given that they should inevery respect be victualled in the same as the ship'scompany, notwithstanding the established laws of theservice, which restricts prisoners to two-thirdsallowance (Thomson, 1915: 106).

These explanations may appear perfectlyreasonable according to the gaolers' perspective,however, a very different light can be cast bycontrasting them with Morrison's lament that:

Pandora's Box, was only 11 feet in length and 18 feetwide at the bulkhead, in which were two small scuttlesof 9 inches, and one on top of 18 or 20 inches square,secured by a bolt. When it was calm, the heat was sointense that the sweat frequently ran in streams to thescuppers, and soon produced maggotts, and thehammocks given to us were full of vermin, from whichwe could find no method of extricating ourselves ... Inthis situation we remained for 5 months ... Ourmiserable situation soon brought sickness on amongstus .... and, as the place was washed twice a week, wewere washed with it, there being no room to shift usfrom place to place, and we had no alternative butstanding up until the deck had dried ... (Rutter, 1935:122).

In a letter to his sister, Nessy, Heywood con-curred with Morrison's complaints about conditionsinside the cell. He stated that the prisoners:

... were all put in close confinement, with both legsand hands in irons, and were treated with great rigour,not being allowed ever to get out of this den. And,being obliged to eat, drink, sleep and obey the calls ofnature here, you may form some idea of the dis-agreeable situation I was in (Tagart, 1832:33) (Fig. 3).

The prisoners' treatment while locked up onthe Pandora is sometimes cited as one of theexamples of the harsh discipline 18th centurynaval crews were subject to. In this regard,Captain Edwards is often considered excessively

HMS PANDORA: FIVE SEASONS OF EXCAVATION^

7

FIG 3. Artist's impression of 'Pandora's Box' (by Robert Allen). The fourteen Bounty crew taken prisoner onTahiti were Joseph Coleman, Peter Heywood, George Stewart, Richard Skinner, Michael Byrne, JamesMorrison, Charles Norman, Thomas Ellison, Henry Hillbrandt (or Heildbrand), John Sumner, ThomasMcIntosh, William Muspratt, Thomas Burkitt and John Millward, four of whom (Skinner, Stewart, Sumner andHillbrandt) did not survive the wreck.

callous, not only because he put the prisonersunder close confinement during the Pandora'sfour month cruise in search of the Bounty, butmore so because he is reported as having shownvery little sympathy for the prisoners' plight afterthe Pandora had struck the reef and during thesojourn on Escape Cay, when the prisoners wereallegedly refused shelter against the harshtropical sun.

How much justification is there to considerCaptain Edwards as an excessive disciplinarian?Obviously, he should not be judged by 20thcentury standards. Most likely, he was simplyfollowing his orders, which were:

... to keep the mutineers as closely confined as maypreclude all possibility of their escaping, having,however, proper regard to the preservation of theirlives; that they may be brought home to undergopunishment due to their demerits (Adm. 2/120).

What obviously mattered to Edwards was thatthe appropriate judicial processes were to befollowed. It was not his prerogative to make,much less act on, judgements or pronouncementsabout the prisoners' guilt or innocence. Theywere to be brought home to undergo punishment

due to their 'demerits'. Thus, by keeping them'closely confined' to preclude escape, all theprisoners were treated in the same manner, inspite of the fact that Bligh had publicly vouchedfor the innocence of Norman, Byrne, Colemanand Macintosh. Peter Heywood later acknow-ledged this during his trial when he stated thatEdwards had not acted improperly by imprison-ing all of the mutineers but had simply followedthe Royal Navy's rules, or, as Heywood phrasedit, ... the dictates of the service' (Tagart, 1832:117).

Captain Edwards was probably also consciousof the need to lock up, guard and separate theprisoners because he was anticipating troublewith some of the prisoners' Tahitian friends. Mostof the mutineers had formed relationships withTahitian women and had also forged bonds offriendship (taio-ship) according to Tahitiancustom with Tahitian men, some of whom weretheir consort's father or brothers. Rival triballeaders had informed Edwards about a plot torescue George Stewart, which was apparentlybeing hatched by Stewart's `taio', who was alsoStewart's de facto father-in-law. Conceivably the

NEW CALEDONIA ••

roeIslands (6 June 1791)8olornon Islands (13 August 1791)

.........^................. Rotuma (5 August 1791)

"SamoartMlands (18 June 1791)

hPalmerston Island(21 May 1791)

Society Islands(23 March 1791)

...

........Cote, Islands(19 May 1791)

•

8^

MEMOIRS OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

FIG 4. Track of the Pandora's search for the Bounty in the South Pacific.

plot would put not only the prisoners at risk butthe Pandora as well (Thomson, 1915: 106-7).Viewed in this light then, Edwards' orders tostrictly separate and guard the prisoners can beinterpreted as the actions of a vigilant com-mander, primarily concerned for the safety of hisship and its crew. Hence the orders to prevent anycommunication between the prisoners and theirTahitian friends or consorts. Obviously some-times these orders, and the orders prohibitingcommunication between the prisoners and thePandora's crew, could not always be enforced:for example, as Edwards mentions, during thetimes that the prisoners were taken forward (tothe heads) to relieve themselves (Adm. MS 180,Edwards' papers, bundle 7).

SEARCHING THE SOUTH PACIFIC. Aftercompleting the ship's maintainance and hisenquiries, Edwards decided to leave Tahiti on 8thMay 1791, following the itinerary outlined in hisorders. These instructed him to proceed to theisland of Whytootackee' :

... calling ... at Huahine and Uliatea, where you neednot anchor as numbers of the natives may be expectedto come off to you, of whom you may probably get thenecessary information ... (Adm 2/120).

After `Whytootackee' (Aitutaki, in the CookIslands) the Pandora's crew searched the Union(Tokelau), Samoan and Friendly (Tongan)Islands (Fig. 4).

Using the Matavai or the Pandora's boats and,on one occasion, a sailing canoe hired in Tonga,Captain Edwards sent off armed shore-parties tolook for word or signs of the mutineers still atlarge. On these occasions the Pandora usuallyremained well offshore to avoid the fringing reefstypical of the South Pacific islands. As a result of

this practice the ship's cutter, with five men undercommand of midshipman John Sival, was lostwhen it failed to return from a search ofPalmerston Island (Fig. 4) on 24 May; it was notheard of again (Thomson, 1915: 86) (Appendix1).

Sival's cutter was the first of two of Pandora'sboats lost. The second one, the schooner Matavai,failed to rendezvous with the Pandora on 23 Juneoff Samoa. Command of the schooner had beengiven to William Oliver, a 20 year old master'smate. After becoming separated from the Pan-dora during a storm, he and his crew successfullynavigated the schooner from Samoa to Tofua,then along the New Guinea coast via the TorresStrait (Fig. 5), to Surabaya in the Dutch EastIndies. This voyage can be ranked with WilliamBligh's much vaunted open boat voyage to Timorin the Bounty's launch. A transcript of a journalkept by Oliver's second-in-command, 16-year-old midshipman David Renouard, has survivedand is of considerable historical interest;particularly because it describes several Pacificislands not previously recorded by Europeanexplorers (Maude, 1964). The schooner's crewarrived in Java on 20th September, several weeksbefore the survivors of the Pandora shipwreck;which occurred at about the same time as Oliverand his crew were struggling to get the schoonerthrough the Torres Strait.

However, their woes were not over yet; Ren-ouard recalls, when they made Surabaya:

Mr Oliver immediately waited on the governor toacquaint him with our misfortunes and to implore theprotection and assistance due to British subjects indistress. But the fate of the 'Bounty' had beencommunicated to (him), in consequence of which thegovernor suspected the truth of our story. The

HMS PANDORA: FIVE SEASONS OF EXCAVATION^

9

FIG 5. Watercolour attributed to George Tobin showing the tender Matavai struggling through Tones Straitwaters. (Reproduced courtesy of the Australian National Maritime Museum)

appearance of our vessel, being built entirely ofOtaheitan wood, served to strengthen him in theopinion that we were in reality part of the 'pirates whohad seized on the 'Bounty' ...

As suspected Bounty mutineers, the crew wasimprisoned in Surabaya. But William Olivereventually managed to persuade the governor tolet them go on to Batavia. On the way there theyput in at Samarang where, during the last week ofOctober, they fortuitously met up with theirformer shipmates who had survived the wreck ofthe Pandora.

Captain Edwards eventually found out why theMatavai had failed to turn up at Anamooka.Oliver had been given orders to proceed toAnamooka (modern Nomuka), one of TonganIsland Group, in the event the tender failed torendezvous with the Pandora off Samoa. Butwhile bound for Anamooka, Oliver miscalculatedthe tender's speed and arrived at Tofua, aboutsixty miles downwind. Mistaking Tofua forAnamooka, the tender's crew waited there forseveral weeks, after which Oliver assumed some-thing untoward had occurred to the Pandora;consequently he decided to make for the DutchEast Indies (Maude, 1964).

In the meantime as the Pandora had waited forthe tender off Anamooka, several of the Pandora'screw experienced difficulties in their interactionwith the islanders. As related by George Ham-ilton, one incident involved Captain Edwards'clerk whose clothes were stripped from him andstolen.

Another incident was an assault on lieutenantRobert Corner, who apparently felt sufficientlyprovoked to shoot dead one of his assailants.None of these incidents appears to have pre-vented what Hamilton referred to as a 'brisktrade' being carried out between the islanders andthe Pandora's men (Thomson, 1915: 132-5). Ona previous occasion Hamilton also mentionedtrade with islanders, specifically the purchase ofobjects not related to provisions or the ship'sstores at:

...Whytootackee, an island discovered by CaptainBligh ... Here we purchased from the natives a spear ofthe most exquisite workmanship; it was nine feet longand cut in the form of a Gothic spire ... (Thomson,1915: 123).

The remainder of the Pandora's voyage throughthe south west Pacific was comparativelyuneventful. Shortly after leaving Anamooka on1st August an auction of the tender crew's

10^MEMOIRS OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

possessions was held. In his papers CaptainEdwards mentions the sale of William Oliver'sand David Renouard's personal possessionsamong the Pandora's officers. This was doneprematurely, in light of the fact that the crew ofthe tender were to be reunited with the Pandora'screw two months later.

Several discoveries of small islands were alsomade, including Rotumah (Fig. 4). On 13 Augustan island Edwards named Pitt's Island (VanikoroIsland) was sighted in the Santa Cruz Group.Hamilton describes it as mountainous andassumed it was inhabited because of smokeobserved in various parts of it (Thomson, 1915:140). However, a shore party was not sent out toinvestigate. Possibly some of these fires wereassociated with the survivors of the Frenchexplorer La Perouse's expedition, whose lastknown port of call had been Port Jackson, inFebruary 1788, after which his vessels LaBoussole and L'Astrolabe had not been heard ofagain. If the Pandora had stopped to investigate,further light may have been thrown on the mysteryof La Perouse's disappearance. But definitiveinformation on the loss of La Perouse's shipswould not be available until 1827, when thesandalwood trader Peter Dillon went to Vanikoroto investigate reports about the source of Europeanobjects he had found on neighbouring Tikopia(Dillon, 1829: 33f0. However, somewhat sur-prisingly, Edwards did not stop to investigate andordered a:

... course to the westward between the latitudes of 10 0

and 9033 S, keeping the mouth of Endeavour Straitsopen, by which means (he) hoped to avoid the dangersexperienced by Captain Cook in his passage throughthe reef in higher latitudes ... On 25th August at 9 in themorning, we saw breakers from the masthead ...(Thomson, 1915: 70).

These breakers were named Look-out Shoaland Edwards attempted to by-pass them bysetting a south-westerly course in the hope offinding a direct channel to Endeavour Straits. Onthis course the Pandora encountered the islandsand reefs around Mer at the eastern entrance tothe Torres Strait. Edwards named them theMurray Islands but did not land on them. In orderto by-pass them, a southerly course was followed.However, no suitable passage was found duringthat day or the next. He kept the ship well away atnight and came back to the reef's edge during theday. A large opening was sighted two days later.The yawl was launched and lieutenant Cornerwas given orders to reconnoitre inside the entrance.The Pandora hove to outside the opening. WhenCorner returned late in the afternoon, he signalled

from the yawl that a navigable passage throughthe reef had been found. It is interesting to notethat Edwards mentions that at this stage the yawlwas 'outside the reef' (Adm. MS 180, Edwards'papers, bundle 16). This indicates that by thistime the Pandora may have already drifted intoPandora Entrance while waiting for the yawl'sreturn. Whatever the case, as night was approach-ing, Edwards, ever prudent, ordered it back to theship, to get it on board before nightfall.

THE WRECKING. In ordering the yawl back tothe ship, Edwards was undoubtedly acting as aprecaution against loosing another of the ship'sboats. With 15 men already missing as a result ofmisadventures with the schooner Matavai andthe cutter, the Pandora could ill afford the loss ofanother boat and more men. Undoubtedly thisaccounts for the ship actually venturing into theentrance late in the afternoon to pick up Corner'syawl. With the sun low on the western horizon,visibility would have been greatly reduced andany reefs lying ahead difficult to see. Hove to, thevessel was especially vulnerable to the strongtidal current which must have driven her furtherwest into the entrance, where it was low tide atapproximately 5.30pm (L. Hiddens, pers. comm.).

It is not difficult to imagine that at this point thecrew may have been distracted by signallingbetween the ship and the yawl (Fig. 6). Moreimportantly, with sunset at approximately 6pmand the sun low on the western horizon afterapproximately 5pm, it would have been verydifficult for the lookouts to discern wavesbreaking on the small submerged coral outcropslocated in this part of Pandora Entrance to thewest of Pandora's location.

Edwards' account of the wrecking describeshow the vessel ran aground when:

at about twenty after seven the boat was seen closein under our stem and at the same time we gotsoundings in 50 fathoms. We immediately made sail,but before the tacks were on board the ship struck uponthe reef when we were getting 2 fathoms on thelarboard side, and 3 fathoms on the starboard side. Anhour and a half after she had struck there was eight feetof water in the hold and we perceived that the ship hadbeat over the reef where we had 10 fathoms water(Thomson, 1915: 72).

Thus, an unfortunate combination of factorscaused the ship to run aground on a coral outcropnot much larger than a cricket oval. This outcropis now unofficially refered to as Pandora's Reef andis surrounded on all sides by depths in excess of30 metres (15 fathoms). It is one of several,mainly submerged, small reef outcrops withinPandora Entrance.

HMS PANDORA: FIVE SEASONS OF EXCAVATION^

11

FIG. 6. The Pandora 'hove to', waiting to take on board Lt Corner's yawl (artist's interpretation, watercolour byB. Searle, 1995).

Possibly, the vessel might have cleared thereef, or at least not have impacted on it as heavilyif she had run onto it several hours later whenhigh water would have been at approximatelyllpm. At this time there would have been betweenthree to four metres of water over the reef (Fig. 7).

Aided by the rising tide, the crew managed torefloat the vessel just before midnight and toprevent her from striking adjacent reefs byanchoring the stricken vessel in 15 fathomswith both anchors' (Rutter, 1935: 125). Morrisonadds how:

Coleman, Norman and Macintosh were ordered out tothe pumps and the boats got out. But as soon as CaptainEdwards heard that we had broke our irons he orderedus to be handcuffed and ironed again ... the Master atArms and Corporal were now armed with each a braceof pistols and placed as additional centinals over us,with orders to fire among us if we made any motion(Rutter, 1935: 126).

One can only speculate why Captain Edwardsordered handcuffing of the other prisoners whohad not been let out of their cell to help at thepumps and why he ordered several armed men on

top of the prison cell. Possibly he was afraid theymight steal a boat, interfere with the crew'sefforts to save the ship, or disrupt plans for theorderly evacuation of the ship.

By all accounts the crew behaved splendidly.They worked hard to prevent the sinking of theship; at the pumps, attempting to stop leaks,repairing equipment or hull damage below decks,fothering the hull, or heaving guns overboard tolighten the ship.

They continued to do so in spite of two fatalaccidents during the night. Hamilton describesvividly how the:

... guns were ordered thrown overboard; and whathands could be spared from the pumps were employedthrumbing a topsail to haul under her bottom toendeavour to fother her ... We baled between life anddeath ... She now took a heel, and some of the gunsthey were endeavouring to throw over board run downto leeward, which crushed one man to death; about thesame time, a spare topmast came down from thebooms and killed another man ... During this tryingoccasion the men behaved with the utmost intrepidityand obedience, not a man flinching from his post(Thomson, 1915: 143).

12^

MEMOIRS OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

Hi .fl tide 3.8 metres

2.5 Metres bei1,13:2,tue li)gh Tide Level

y 1.2 Metres

05 metres

Low Tide 0.4 Metres

Time ofWreck

5 pm^6 pm 7 pm^ 11 30 pm

FIG. 7. Tidal range at Pandora Entrance on 28 August1791. (Courtesy L. Hiddens)

The identity of the two men killed before thePandora sank is unfortunately not revealed inCaptain Edwards' list of the 31 crew lost with theship (Adm. MS 180, Edwards' papers).

Early next morning it was clear that nothingmore could be done to save the stricken vessel.Orders were given to abandon ship and to releasethe eleven remaining prisoners from Pandora'sBox. It appears the armourer's mate, Hodges,acted too slowly here. According to Morrison, theship began to sink before Hodges was able torelease all of the prisoners from their fetters:

At daylight the boats were hauled out and, most of theofficers being aft on top of the Box, we begged that wenot be forgot, when by Captain Edwards' ordersJoseph Hodges, the armourer 's mate, was sent down totake the irons off; but Skinner, being too eager to getout, got hauled up with his handcuffs on, and therebeing two following him close, the scuttle was shutand barred again. I begged the Master-at-Arms toleave the scuttle open when he answered 'Never fearmy boys, we'll all go to hell together !'. The wordswere scarce out of his mouth when the ship took a sallyand a general cry of there she goes' was heard. Burkittand Heildbrandt were still handcuffed and the shipunder water as far as the mainmast and it was nowflowing in fast on us when Divine providence directedWilliam Moulter to the place. He was scrambling upon the box and, hearing our cries, took out the bolt andthrew the scuttle overboard. On this, we all got outexcept Heildbrandt (Rutter, 1935: 127).

William Moulter's solicitude, which undoub-tedly saved several other prisoners from certaindrowning, was recognised in 1984 when one ofthe sand cays in Pandora Entrance was namedafter him. The cay at the eastern approach toPandora Entrance, referred to by Edwards asEntrance Cay, is now called Moulter Cay tocommemorate Moulter's humane deed.

ESCAPE CAY. Thirty-one ofthe Pandora's crewand 4 of the prisoners did not survive the wreck.Among the casualties were the two extra guardsposted on top of Pandora's Box, master-at-arms

FIG 8. George Reynolds' pen and ink drawing showinga shipmate in the water after the wrecking. (Privatecollection)

John Grimwood and ship's corporal WilliamRoderick, as well as prisoners, George Stewart,Henry Heildbrandt, John Sumner and RichardSkinner. The survivors, 89 crew and 10 prisoners,reached a small sandcay about three miles to thewest of the wreck. Incredibly, several of theprisoners managed to stay afloat in spite of stillwearing their handcuffs (Fig. 8).

Peter Heywood described the survivors' plightin a letter he later wrote to his sister, adding in themargins of his letter:

... two little sketches of the manner in which HMSPandora went down on 29th August, and the appearancewe who survived made on the small sandy key withinthe reef, about ninety yards long and one hundredathwart, in all ninety-nine souls. Here we remainedthree days, subsisting on a single wineglass of wine orwater, and two ounces of bread daily, with no shelter.Captain Edwards had tents erected for himself and hispeople, and we prisoners petitioned him for an old sailwhich was lying useless, but he refused it, and all theshelter we had was to bury ourselves up to the neck inthe burning sand, which scorched the skin, we beingquite naked, entirely off our bodies, as if dipped in largetubs of boiling water (Tagart, 1832: 71) (Fig. 9).

The identity of the sandcay Heywood describedhas not yet been definitively established. However, itis likely to be Preservation Cay (Fig. 10). Thesurvivors called it 'Escape Cay' to distinguish itfrom Entrance Cay' (Moulter Cay), the sandcaymarking the entrance to Pandora Passage.Edwards placed both cays on latitude 11°23'S(Thomson, 1915: 89). However there is a problemwith this determination as neither Moulter Cay norPreservation Cay are actually on the latituderecorded by Edwards. On modern charts theiractual latitude is at approximately 11°25'S (GreatBarrier Reef Marine Park Authority, 1985). Thediscrepancy of two minutes can be attributed to theaccuracy of Edwards' instrument, which wasprobably an octant or quadrant.

HMS PANDORA: FIVE SEASONS OF EXCAVATION^

13

FIG. 9. Thomas Heywood's sketches of the wrecking and the survivors on the cay. (Courtesy of the NewberryLibrary, Chicago)

The identification of Preservation Cay as EscapeCay becomes more likely with the addition ofdetails from Morrison's accounts. Morrisonmentions that the cay was the middle of threesimilar cays within Pandora Entrance:

... the whole of it being no more than a smallsandbank washed up on the reef which, with a changeof wind, might disappear, it being scarecely 150 yardsin circuit and not more than 6 feet from the level ofhigh water. There are two more of the same kind ofwhich this is in the middle; between it and the one tothe southward is a deep channel through which a shipmight pass in safety (Rutter, 1935: 128).

Looking at the modern configuration of cayswithin Pandora Entrance (Fig. 10) (Great BarrierReef Marine Park Authority, 1985) and assumingthis reflects the situation in August 1791, thereare three cays and two sandbanks. At spring tidesthe sandbanks sometimes dry, but generally theyare submerged and do not warrant being calledsand cays proper. For this discussion, they havebeen disregarded. Morrison's description appearsto suggest that the three cays in question arealigned along a north-south axis. However, thereare only two cays oriented approximately alongthat axis (Fig. 10); the third cay (Moulter Cay)being well to the east. One explanation for Mor-rison's description could be that one of the twosandbanks to the north of 'Melbourne Cup' Cay(Cay 11-088 on BRA Q 102) (unofficially namedMelbourne Cup Cay by members of the Queens-land Museum's 1983 Pandora expedition tomark the location of a piggy-back horse race onMelbourne Cup race day in 1983) was a

substantial cay in 1791, but has eroded since then.If this was the case at the time of Pandora's loss,then Melbourne Cup (Cay 11-088) Cay may beEscape Cay. However, this explanation isunlikely in view ofMorrison's mention of a 'safe'and 'deep' channel between the middle cay and... the one to the southward'. The channel

referred to is unlikely to be any of the narrow,east-west running passages between MelbourneCup (Cay 11-088) Cay and Preservation (Cay11-091) Cay or between the string of small reefsdirectly to their south. None of these east-westaligned passages is wider than 100m. While theymay be reasonably safe for modern motor-drivenvessels, a navigator attempting to pass throughthem under sail would be reckless in the extremebecause of the strong tidal flows and eddies whichoccur inside the passages. It therefore seems moreplausible that Morrison's use of 'southward' indesignating the 'safe' channel's position shouldactually be interpreted as a channel leading to thesouthward rather than lying to the southward.The wide opening between Moulter Cay andPreservation Coy is certainly wide enough anddoes lead to the south.

Possibly then, this opening is the channelexplored by lieutenant Robert Corner, which thePandora would have taken the next day if she hadnot run aground while manoeuvring to take onboard the yawl. The three cays Morrison men-tioned are most likely to be Moulter (Entrance)Cay, Preservation (Escape) Cay (Cay 11-091)

FIG. 10. Pandora Entrance, modern situation (map drawn from GBRMPABRA Q102).

and the unnamed cay, now referred to unofficiallyas Melbourne Cup (Cay 11-088) Cay (Fig. 10).

During the two days which the survivors spenton Escape Cay, the majority of the men were idle,although a number of them were undoubtedlyinvolved in making more seaworthy the fourboats saved from the Pandora. While one boatwent off to fish, another was sent back to thewreck the next day to see if anything worthwhilecould be salvaged (Fig. 11). They returnedwith part of one of the Top Gallant Masts ... and acat ... found sitting on the crosstrees ...' (Rutter,1935: 129). The cat is not mentioned again in anyother source, and its fate is unknown.

THE SURVIVORS' JOURNEY TO ENGLAND.Escape Cay to Mount Adolphus Island. Bysending lieutenant Corner in the yawl toreconnoitre Pandora Entrance, Edwards was notbeing overly cautious. Undoubtedly most watch-ful commanders would have done the same,especially in light of the remarks about theintricacies and dangers of navigating in GreatBarrier Reef waters made by navigators of JamesCook and William Bligh's calibre.

Captain Edwards was to use the informationgathered by Corner to give effect to what mayhave been another aspect ofhis orders, which was

to find, in a more northerlylatitude, an easier passagethrough the Great Barrier Reefthan the track from Provi-dential Channel to EndeavourStrait followed by Cook in1770. Edwards described thepassage the Pandora'ssurvivors followed, sayingthat they left Escape Cay on:... the 31st August ... at half past

ten in the forenoon (and)embarked and steered N.W. by W.and W.N.W. within the reef. Thischannel through the reef is betterthan any hitherto known. In therun from thence to the entrance ofEndeavour Strait there is a smallwhite island on the larboard end ofthe channel which lies in latitude11 0 23' S' (Thomson, 1915: 75)(Fig. 12).

Edwards omits to name theisland at the end of thischannel, but with reference tomodern charts it is reasonableto assume that the trackfollowed by the Pandora'sboats took them through whatis now named Denham Pass.

Edwards" small white island' (Thomson, 1915:75) can therefore be identified as eitherCholmondsley Island or Wallace Islet (AUS 835).

However, the passage pioneered by thePandora's boats was never generally adopted norrecommended in 19th century sailing directions.Edwards' claim about the superiority of thepassage was not followed up; presumablybecause of a general perception among merchantcaptains that advice from ships' commanderswho had lost their ships ought not to be heeded.More importantly perhaps, how could Edwardshave hoped to be compared to such accomplishednavigators as Cook and Bligh (whose reputationas a skilled navigator and very capable hy-drographer was never adversely affected by thedebate concerning his qualities as a naval com-mander). Edwards' and Hamilton's descriptionsof the survivors' route refer to landmarks andgeographical features noted by both James Cookand William Bligh. Other landmarks and featuresare also noted and named.

Distributed among the four boats, the 99 sur-vivors set off for the mainland; before nightfallthe boats formed into single file, the launch infront with each boat successively in tow (Fig. 13).At daylight on 1 September 1791, the mainland

'Melbourne Cup Cay(11-088) . r ..

i„:, ....Preservation• • •,,(11-091)^,....'(Escape Cay

te.:=

14^

MEMOIRS OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

HMS PANDORA: FIVE SEASONS OF EXCAVATION^

15

FIG 11. George Reynolds' water colour of the masts protruding from the waves. (Private collection)

was sighted and the two yawls sent ashore atFreshwater Bay to search for water, while thelaunch and pinnace made for Mount AdolphusIsland.

Morrison and Hamilton's accounts are mostinformative about the survivors' progress afterEscape Cay. Their accounts give interestingdetails about Cape York, the Torres Straits andtheir inhabitants.

Morrison recalls that the survivors:... embarked in the following manner: McIntosh,

Ellison and myself in the pinnace with Capt Edwards,Lieut. Hayward and 19 officers and men ...; in the RedYawl went Burket & Millward with Lieut. Larkan and19 officers and men; in the Launch, Peter Heywood,Josh Coleman & Michael Byrn, with Lieut. Corner &27 officers and men; in the Blue Yawl, Norman andMuspratt, with the master and 19 officers and men,making ninety-nine souls in all ... next morning, the 1stof September, we made the land ... and the two yawlswere sent in to the land, while we stood on towards anisland where we hoped to get water. In the afternoonwe were joined by the yawls who had got water andhaving filled their vessels followed us ... We stood infor a bay to search for water and as we approached abeach found that there were some inhabitants on it, ...The natives appeared on the beach to the amount of 18or 19 men, women and children, who appeared to beall of one family; they came off freely to the boatswhen we found that the colour of their skin washeightened to a jett black by means of either soot or

charcoal ... some had holes in their ears which werestretched to such a size as to receive a man's arm. Wemade signs that we wanted water which they soonunderstood, and half an ancker being given to one ofthem & some trifles by way of encouragement, he soonreturned with it almost full which (we poured) into abrecco and we gave it to him again. He then called ayoung woman who stood near him and sent her for thewater ... Meanwhile two of the men began to preparetheir weapons, and a javelin being thrown ... severalmuskets were fired ... (Rutter, 1935: 129-30).

Morrison's ability to recall such details as thenumber of men in the boats, which prisoners wentwith which officers and in which boat isremarkable. Looking at his published account,the amount of detail he is able to recall aboutmany aspects of the voyage suggests he had ajournal, notebook or some paper to make notes.This is corroborated by Captain Edwards' mentionthat he suspected that some of the prisoners wereengaged in a secret correspondence with some ofthe Pandora's crew (Adm. MS 180, Edwards'papers bundle 7). Alternatively, he may later havehad access to one of the Pandora's officer'sjournals; perhaps when he was writing his'memorandum' while a prisoner awaiting hiscourt martial in Portsmouth (Du Rietz, 1986).

Possibly Hamilton's notes or journal were ac-cessible to Morrison, as Hamilton records similar

Coral Sea

„tr:

Rant

^

•`:, •^Wednesday Is

.^....

Little

...^

...... ................^........^ lot Adolphus „^a ^a sea. 9 ' ) ea

^ Adolphus Landed and ate a plum-like iriri;

knives end buttonsBooby I^

. oxo.nged

s,....... ...........

Fres^Bayte=ter^ te•

2 yawls sentPrince of Wares^ -le^hwater

ashore for waterIsland

CAPE YORKPENINSULA

50^100 krn

2 neWawrecksite,^29 August. 1791

4 boats left for Time30 August, 1791

a

16^

MEMOIRS OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

SULAWESI

C:4frar

sel

C:2^• 'zBall^Flores^p

Timor........... .................

....

Torres Strait

-X Pandora wrecksite

Coral Seasee inset irri9.3

/AUSTRAUA

To England ---

(crew divided between four vessels)

Sumba Isiah

INDIAN OCEAN

FIG. 12. A, B, Survivors' route to Timor.

details about the survivors' progress from EscapeCay:

... we embarked and laid the oars upon the thwarts,which formed a platform, by which means we stowedtwo tiers of men ... At meridian we saw a cay[Cholmondsley Island] bounded with large craggyrocks ... At eight in the morning, the red and blue yawlswere sent ahead ... to investigate the coast of NewSouth Wales ... On entering a very fine bay[Freshwater Bay] we found most excellent waterrushing from a spring at the very edge of the beach.Here we filled our bellies, a tea kettle, and two quartbottles. The pinnace and launch had gone too far aheadto observe any signal of our success; and immediatelywe made sail after them ... In two hours we joined thepinnace and launch, who were lying to for us ... Afterrunning along, we came to an inhabited island [MountAdolphus Island] from which we promised ourselves a

supply of water. On our approach, the natives flockeddown to the beach in crowds ... we made signals ofdistress to them for something to drink, which theyunderstood; and on receiving some trifling presents ofknives and some buttons cut off our coats, theybrought us a cag of good water. They would nothowever bring it the second time, but put it down onthe beach and made signs to us to come on shore for it.This we declined as we observed the women andchildren ... supplying the men with bows and arrows.In a few minutes, they let fly a shower of arrowsamongst the thick of us. Luckily we had not a manwounded ... We steered from these hostile savages toother islands [Little Adolphus Island] (Thomson,1915: 148).

There is a slight difference between Edwards'account and Morrison's and Hamilton's account

HMS PANDORA: FIVE SEASONS OF EXCAVATION^

17

FIG 13. The Pandora's boats in tow while making for Timor. (Private collection)

of the survivors' first contact with the Australianmainland, the Torres Strait's islands and theirinhabitants. Edwards glosses over the hostilenature of the encounter.

Hamilton and Morrison are more forthcoming,although they do not distinguish whether thepeople were Aborigines or Torres StraitIslanders. However, Hamilton's mention of thebows and arrows used against the Pandora'sboats suggests that the encounter was with TorresStrait Islanders, as Aborigines did not use thiskind of weapon. From Hamilton's account, itappears that after the hostile encounter on MountAdolphus Island an armed party probably landedon Little Adolphus Island to look for water beforesetting off for Horn Island (called Laforey'sIsland by Hamilton).

Mt Adolphus Island to Timor. Edwards namedLittle Adolphus Island Plum Island, after anabundant fruit — probably the bountiful TonesStrait `nonda' plum — found growing there bythe shore party. They left the island beforenightfall and steered a westerly course towardsthe Prince of Wales Islands, west of Cape York.Several of the islands were named by Edwards,however, not all of these names were adopted tobe passed on and recorded on modern charts.

Edwards recounts how in the evening they:... steered for the islands which we supposed were

those called Prince of Wales' Islands by Captain Cook,and before midnight came to, near one ofthese islands,in a large sound formed by several of the surroundingislands, to several of which we gave names, and calledthe sound Sandwich Sound. It is fit for the reception ofships, having from five to seven fathoms of water.There is plenty of wood on most of the islands, and bydigging we found very good water ... (Thomson, 1915:149).

Although Edwards probably chose the namesof the various other islands making up the Princeof Wales Group, he does not mention any of themin his text. However, Hamilton does mentionthem individually:

We steered for those islands which we supposed werecalled the Prince of Wales' Islands; and at about two inthe morning came to anchor ... along side of an islandwe called Laforey's Island [Horn Island] ... Themorning was ushered in with the howling of wolves ...Lt. Corner and a party were sent at daylight to searchagain for water... As we landed, we discovered afootpath which led down into a hollow ... and ondigging we had the pleasure to see a spring rush out ...On traversing the shore, we discovered a moray, orrather a heap of bones ... among them two humanskulls, the bones of some large animals, and someturtle bones. These were heaped together in the form ofa grave, and a very long paddle, supported at each endby a bifurcated branch of a tree, laid horizontally alongit ... There is a large sound formed here, to which wegave the name of Sandwich Sound [Flinders Passage(AUS 293)], and commodious anchorage for shippingin the bay, to which we gave the name Wolf's Bay,Hammond 's Island lies north west ... Parker's Island[Wednesday Island (AUS 293)] from north by west tonorth and by east ... Sandwich Sound is formed byHammond's, Parker's and a cluster of small islands onthe starboard hand at its eastern entrance [TuesdayIslets (AUS 293)] and near the centre of the sound is asmall dark-coloured, rocky island [Channel Rock(AUS 293)] (Thomson, 1915: 151).

From Hamilton's account, it is obvious that ashore party landed on Horn Island (Hamiltoncalls it Laforey Island) and traversed part of itsnorthern shoreline. It is assumed that the shoreparty landed just west of King Point on its northeastern shore, where the coast forms a shallowbay towards the south (i.e. Hamilton's Wolf'sBay). However, they do not appear to havetraversed very much of the shore as Hamiltonomits to mention Thursday Island, which, if theysaw it, they must have assumed to be part of

18^MEMOIRS OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

Hammond Island because of its height. Fromtheir vantage point at Wolf's Bay the channelbetween Thursday and Hammond Islands wouldnot have been apparent; Thursday Island wouldtherefore have appeared an integral part ofHammond Island.

The survivors made off from Horn Island assoon as they had filled their containers withwater. They left Sandwich Sound by the entrance,now called Flinders Passage, between Hammondand Wednesday Islands (AUS 293), enteredPrince of Wales Channel and last sighted theAustralian coast late in the afternoon when, westof Goods' Island, they finally cleared Prince ofWales Channel (Thomson, 1915: 77) (Fig. 12B).

Although there is no record of third lieutenantThomas Hayward's thoughts at the sight ofPrince of Wales Island receding from view, itwould be understandable if he had been over-heard muttering to himself that as far as he wasconcerned this was the last time he wanted to seteyes on this part of the world. After all, havingbeen with Bligh in the Bounty's launch in 1789, itwas the second time within as many years that hehad been in Torres Strait waters in such dis-tressing circumstances. For as Morrison recounts:

... the heat of the weather made our thirst unsupport-able and as the canvas bags soon leaked out, noaddition of allowance of water could take place, and tosuch extremity did thirst increase, that several of themen drank their own urine ... (Rutter, 1935: 131).

The survivors' progress through the ArafuraSea was comparatively uneventful in spite of theextreme deprivations suffered as a result ofhunger, thirst and the heat of the sun. Some of theprisoners' lot was even worse as they not onlysuffered hunger and thirst, but were also made tolie down on the boats' floor with their armspinioned. Morrison relates how he and Ellisonapparently had done or said something toprovoke Captain Edwards' wrath, and weresubsequently ordered to be pinioned with a cordand lashed down in the boats' bottom (Rutter,1935: 131).

Timor was finally sighted after 12 days in theArafura Sea. The boats eventually made theDutch East India Company's (VOC) settlement atCoupang several days after the survivors hadspent a day and night ashore near a small villageabout seventy miles to the southwest of Coupang,where they bartered for water and food with localTimorese (Thomson, 1915: 156).

Upon arrival at Coupang, their reception byVOC officials was cordial. The Dutch authoritiesdid everything possible to ensure a speedy and

full recovery from the ordeal of the 15 day openboat voyage. They were soon fit enough to makethe journey to Batavia (Jakarta) where theywould be able to embark on VOC vessels boundfor Europe.

During the five weeks which the survivorsspent in Coupang, Edwards took charge ofanother group of prisoners. This group of eightmen, one woman and two children had arrived inCoupang two weeks before the Pandora'ssurvivors. Led by William Bryant, they wereescaped convicts from New South Wales and hadmade the long sea voyage in a small fishing boatfrom Port Jackson along the east coast of Aus-tralia to Torres Strait and across the Arafura Sea(Martin, 1991).Timor to England. While on the journey fromCoupang to Batavia, the ten surviving Bountyprisoners were confined to the lower deck of theVOC ship Rembang, which, but for the exertionsof the Pandora's survivors who helped to crewher, was almost wrecked in a storm off the northcoast of Java. The Rembang was then forced toput in at Samarang for repairs. Initially this delaywas a setback for the Pandora's survivors. How-ever, it later proved beneficial as it resulted in afortuitous reunion with William Oliver's crewfrom the Matavai, who had been lost off Samoaand given up for dead nearly four months earlier.

For William Oliver the pleasure of the reunionwith the rest ofhis shipmates was short-lived. Hisname is to be counted among the thirteen crewlisted as deceased after the survivors reached theDutch East Indies (Appendix 1). Some probablydied as a result of the extreme conditions they hadbeen exposed to during the open boat voyage(Thomson,1915: 145), but most died of diseasescontracted in Batavia, where the survivorsarrived on 7 November 1791. Oliver's second incommand, David Renouard, was lucky to survivethe rigours of Batavia's pestilential climate. Ableseaman Barker, one of the Matavai's crew, haddied before Oliver's group got to Samarang.(Adm. MS 180, Edwards' papers, bundle 7).

Once in Batavia, Captain Edwards made everyeffort to get berths on ships bound for Europe forhimself and his crew. He negotiated with theVOC and agreed to sign on most of the Pandora'ssurvivors as crew on three of the Company'sships returning to Holland from Batavia. (Thom-son, 1915: 81). Edwards negotiated a passage forhimself, George Passmore, Gregory Bentham,two midshipmen and his prisoners, again in ironfetters, on board the Vreedenburg. (Thomson,

HMS PANDORA: FIVE SEASONS OF EXCAVATION^19

1915: 163) The remainder of the Pandora's crewwere divided into three groups, each under one ofthe three lieutenants, and were mustered as crewonto the VOC ships Horssen, Hoornweg andZwaan.

Brown, the beachcomber who had been enteredon Pandora's muster list at Tahiti, was paid off inBatavia. Only one man was too sick to travel andwas left behind in hospital in Batavia. (Thomson,1915: 87). No records about the fate of these twomen have been found to date.

When the Vreedenburg arrived at Cape Town,Edwards transferred his party to HMS Gorgon,homeward bound from New South Wales. Thereare accounts of this voyage, several of whichmention Edwards' presence on board — one byMary Ann Parker, the wife of the Gorgon'scaptain, who apparently enjoyed Edwards' com-pany during the voyage home (Parker, 1795).Unfortunately Mrs Parker omits to mention theprisoners, responsibility for whom Edwardspartially ceded to Captain Parker.

Edwards was the only officer to transfer hisparty, including the escaped New South Walesconvicts, to the Gorgon. The remainder of Pan-dora's crew remained on board the other threehome bound VOC ships as mustered crew andeventually got home to Britain via Holland.Together with sixteen of Pandora's men, RobertCorner was mustered on the Horssen. Theyarrived in Den Briel on 21st July 1792, whereCorner drew an advance of £30 on the Admiralty.He used this money to pay for his men'ssubsistence and their passage to England fromHolland (Adm. 106/1317). The groups underLarkan and Hayward's charge arrived in Englandsometime afterwards; Hayward's group arrivedin Den Briel in the Hoornweg, while Larkan'sgroup arrived in Rammekens in the Zwaan on 12August 1792.COURTS MARTIAL AND SUBSEQUENTCAREERS. HMS Gorgon arrived in England inearly June 1792. The fate of the ten Bountyprisoners remained undecided for another threemonths; they were detained as prisoners on HMSDuke in Portsmouth Roads until their courtsmartial. Hearings started on 11 September 1792.

Michael Byrne, Joseph Coleman, Charles Nor-man and Thomas McIntosh were immediatelyacquitted because William Bligh had vouched fortheir innocence. Tom Ellison, John Millward andThomas Burkitt were found guilty, sentenced todeath and were eventually hanged on board HMSBrunswick in October 1792 (Dening, 1992:

39-40; 46-48). In spite of also being found guiltyof m utiny and sentenced to death, Peter Heywoodand James Morrison were recommended to theKing's mercy and were eventually pardoned;William Muspratt was acquitted on a legaltechnicality.

Peter Heywood remained in the navy and roseto the rank of post captain. He retired in 1819after a distinguished career as a sea-going officer.His service record included duty as signal mid-shipman, master's mate and acting lieutenant onvarious ships in the Channel Fleet until 1798.Upon receiving his lieutenant's commission hewas given command of the brig HMS Amboyna,attached to the India Station at Madras. Whileserving at the India Station he surveyed northernAustralian waters as the commander of HMSVulcan between 1800 and 1801. During this timehe had occasion to visit many islands in the DutchEast Indies, including Timor, where he hadlanded ten years earlier as one of CaptainEdwards' prisoners. In 1807 Captain Heywoodcollaborated with James Horsburgh, the BritishEast India Company's hydrographer, assistinghim with information and the production of thecharts which accompanied Horsburgh's SailingDirections 'for the navigation of the Indian Seas'(Tagart, 1832: 164ff).

James Morrison also stayed in the Navy andhad an exemplary career as a warrant officer,fighting in a number ofmajor naval battles duringthe Napoleonic Wars. He drowned in 1807 whileserving as the gunner on HMS Blenheim. Whilein prison in 1792 awaiting his court-martial, theReverend William Howell, vicar of St John's inPortsea, assisted him with the preparation of ajournal and a separate memorandum detailing hisexperiences of the mutiny in the Bounty, his lifeas a mutineer in the South Pacific and hisimprisonment on board the Pandora (Rutter,1935; Du Rietz,1986; De Lacy, 1997).

Edward Edwards was exonerated for the loss ofhis ship. However, he never commanded at seaagain. He was twice appointed as a 'regulating'(i.e. recruiting) captain; first for Argyleshire andthen for Hull. His various requests to theAdmiralty for another sea command were neveracted upon. He was, however, eventually pro-moted to Admiral's rank (Syrett & Niardo, 1994).A reputed link between Edwards and the'Pandora Inn' in Restronguet, near Falmouth,UK, of which Edwards is said to have been thelandlord during his retirement, has not beenconfirmed. This link appears apocryphal as the

20^MEMOIRS OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

correspondence with the Admiralty, in whichEdwards sought further appointments as a sea-going officer, is post-marked from his Londonresidence or from Edwards' home in Lincolnshire.He died in 1815 and was buried in St Remegiuscemetery in his native village, Water Newton inHuntingdonshire. Edwards' obituary in TheLincoln, Stamford & Rutland Mercury of 21stApril 1815 mentions that he had felt 'to the latestperiod of his life', the effects of the hardships heexperienced during the open boat voyage toTimor.

John Larkan later served as first lieutenant onHMS Defence under Lord Gambier; he sawaction at the Battle of the 1st June (1794) andsoon afterwards was promoted to commander.This was his last sea going appointment. Hereturned to Ireland where he subsequently wasgiven command of an Irish division of SeaFencibles (Marshall, 1825: 250).

Robert Corner appears to have continued in anactive naval career; there is evidence that LloydsPatriotic Fund awarded him one of their pres-entation swords for distinguished conduct whileserving as a lieutenant on board HMS Thisbeduring action against the French frigate Veloce in1803 (May & Annis, 1970: 70). He ended hiscareer as Superindendant of Marine Police inMalta and died in 1820 (Marshal,1825: 38).

Thomas Hayward's naval career was cut shortwhen he perished with his crew, while in com-mand of the sloop HMS Swift, which was lostwith all hands during a typhoon in the SouthChina Sea in 1797 (James, 1886: 462).

George Hamilton published an account of thePandora's voyage in 1793 (Thomson, 1915;Kenihan, 1990; Hamilton, 1998). Upon his returnto Britain, his next naval appointment was assurgeon on board HMS Lowestoff, which waspart of the British Mediterranean fleet under LordHood. Hamilton was discharged in April 1794having lost an arm, probably after being woundedin action against French fortifications on Corsica(Pigott, 1995: 24ff). It is assumed he returned tohis native Northumberland sometime during 1794,where he lived in retirement on a naval pensionuntil his death in 1796 (Kenihan, 1990: xvii).

George Passmore's career did not remainunblemished; he appeared before a court martialin 1793. The nature of his offence is not recordedbut was apparently unrelated to his conduct as thePandora's master. Whatever the offence, it wasserious enough to cause the Navy Board todecline an appointment as master of HMS

Daedalus, in spite of representations from thecaptain and recommendations by Admiral SirCharles Knowles (Adm. 106/1317).

The rest of the Pandora's crew have recededinto historical obscurity, although undoubtedlyanecdotal information about some of them, e.g.on master's mate George Reynolds, is extant inprivate collections as well as in public recordsrepositories. Archival information on many ofthe others should also be recoverable, as theirnames will appear in such documents as musterlists and pay books, as well as in private collect-ions, or obituaries in contemporary newspapers.

However, what remains of them in a verytangible way are their personal possessions andprofessional equipment — their material culture— which was lost with the Pandora. Much of thisappears to have been preserved within and aroundthe hull and can be retrieved using systematicarchaeological methods and analysed and in-terpreted using models developed in materialculture studies. This, then, is the rationale forconducting an archaeological investigation of thePandora wreck, which provides the functionalcontext of a well preserved collection of objectsin use by a microcosm of late 18th century Britishsociety (Rodger, 1986: 14).

Finally, as far as the Pandora is concerned,neither the Admiralty nor the colonial authoritiesin New South Wales apparently made anyattempts to salvage material from the wreck.There is no evidence that the wreck was disturbeduntil its rediscovery in November 1977 bydocumentary film makers Steve Domm, JohnHeyer and Ben Cropp, with Royal Australian AirForce assistance.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION

SITE DESCRIPTION AND DISTRIBUTIONOF THE WRECKAGE

LOCATIONAL INFORMATION. The wreck islocated within Pandora Entrance (Figs 10, 12B),approximately 5km to the NW of Moulter Cay.This sandcay is on the outer Great Barrier Reefabout 140km ESE of the tip of Cape York innorth-eastern Australia.

Although the wreck lies inside Pandora Entrance,it is exposed to the force of swells from the CoralSea generated by easterly winds, prevalentbetween July and December. Within a radius ofapproximately 200m to the SE, E, N and W, thewreck is surrounded by four small submergedreefs which provide some protection againstocean swells. These reefs also deflect the flow of

AI,ICHOR?

SANCHORP BAKERG HENDERSON

10 METRES

CHAIN PLATE 9

/ SHEATHING

COPPERPUMP TUBING

ANCHOR?,

C)^CANNON

CANNON^CANNON

CANNON

Us

00

11‘RUDDERFITTINGS

0 'kANN

C,^Q^- CHAINPLATES

CAPSTAKI

,) ,V) \lcH°R pCHAIN PLATE

COWLING?

HMS PANDORA: FIVE SEASONS OF EXCAVATION^

21

FIG. 14. Pandora wrecksite 1979: predisturbance site plan drawn from photomosaic. (P. Baker & G. Henderson)

tidal currents. The pattern of these currents hasnot yet been determined definitively, althoughpreliminary measurements have been recorded(Ward et al., 1998). However, divers have exper-ienced their considerable strength, sudden onsetand unpredictability. Consequently conditionsfor marine archaeological recovery operationsare challenging. Underwater working conditionsare further complicated by depths of between30m and 35m which impose limitations on (airbreathing) diving operations.

An area with a radius of 500m, centred on thesite at the intersection of latitude 11°2240S andlongitude 143°59'35"E, has been declared aprotected zone under Section 7 of the Common-wealth's Historic Shipwrecks Act (1976). Entryto this zone is subject to a permit issued by theDirector of the Queensland Museum, who is theMinister's delegate under the Historic ShipwrecksAct (1976), responsible for historic wrecks inCommonwealth waters off Queensland.