UNIVERSITÀ DEL SALENTO DIPARTIMENTO DI BENI CULTURALI BAS Saggi e testi Collana diretta da Lucio Galante 52

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

UNIVERSITÀ DEL SALENTODIPARTIMENTO DI BENI CULTURALI

BAS

Saggi e testi

Collana diretta da Lucio Galante

52

Mario Congedo Editore

Gerusalemme(WALKING TOWARDS JERUSALEM: CULTURES, ECONOMIES AND TERRITORIES)

a cura diAnna Trono, Marco Leo Imperiale e Giuseppe Marella

In viaggio verso

CULTURE, ECONOMIE E TERRITORI

Università del SalentoPubblicazioni del Dipartimento di Beni Culturali già Pubblicazioni del Dipartimento dei Beni delle Artie della Storia

Comitato Scientifico: Francesco Abbate, Giovanni Carli Ballola, Vincenzo Cazzato, Francesco de Lu-ca, Marina Falla Castelfranchi, Lucio Galante, Regina Poso, Luigi Rizzo†, Massimiliano Rossi, Luci-nia Speciale, Anna Trono, Benedetto Vetere

ISBN 9788867660995

Tutti i diritti riservati

CONGEDO EDITORE - 2014

Capitolo 4

Medieval Pilgrims from the Eastern Adriatic Coast to Terra Sancta and Jerusalem1

Zoran LadićCroatian Academy of Sciences and Arts

Zagreb Croatia

Medieval pilgrimages from various European regions to the Holy Land andJerusalem have been examined by many European medievalists butpilgrimages to Terra Sancta and Jerusalem from cities and towns situated on theEastern Adriatic coast are rather poorly analyzed. Although Croatianmedievalists have examined aspects of medieval pilgrimages and pilgrims, ageneral overview of medieval pilgrimages to the Holy Land and Jerusalem isstill lacking. Therefore, in this paper I shall try to present some aspects ofpilgrimages from Istria, the Croatian coast and Dalmatia to the Holy Land andJerusalem in the medieval period. This research is based mainly on theexamination of narrative sources, charters, and notary records. Since for theperiod prior to the second half of the thirteenth century there is a significantlack of contemporary sources, in this article I shall focus primarily on the Highand Late Middle Ages. Sources from that period, especially last wills recordedby communal notaries, are preserved in abundance for almost all cities andtowns on the Eastern Adriatic coast, enabling the analysis of pilgrimages andpilgrims from various points of view. Thus, here I shall examine the gender ofpilgrims, their social status and the costs of pilgrimages to Terra Sancta andJerusalem.

Another aspect that I shall analyze in this article is the problem of crusades toTerra Sancta as a form of pilgrimage from the end of the thirteenth century i.e.

95

1 I use the terms Terra sancta and Jerusalem because in medieval sources, particularly inconnection to pilgrimages and crusades as specific forms of pilgrimage, their meaning usuallyoverlaps. For example, in medieval Croatian sources the following terms refer to these forms ofpilgrimage: palmarius, palmatus, peregrinatio ad sanctum sepulcrum Domini, peregrinus ad sepulcrumChristi, peregrinus ad sepulcrum Iesu Christi, peregrinatio vltra mare ad visitandum sanctissimumseppulcrum domini nostri Iesu Christi in Ierusalem, peregrinus cruce signatus, transitus in terra de ultramare, pasagium in subsidium Terre Sancte, pasagium de ultra mare, pasagium generale, transitusgeneralis in auxilum Terre sancte and so on.

after the fall of Acre in manibus impiorum. In contrast to European and Americanmedievalists, who have examined this problem in detail, Croatian historiographyis only just beginning to research that form of medieval pilgrimage.

1. VOICES CONTRA PEREGRINATIO

In the period of early Christianity pilgrimages were considered by some ofthe most famous Christian theologians. As early as the fourth and fifthcenturies the term peregrinatio and its theological meaning was discussed in theworks of some early Christian theologians. Thus, Pope Gregory the Great (540-604) underlined that a Christian is only a passer-by on the Earth (viator acperegrinus)2. In his extensive work De civitate Dei St Aurelius Augustine alsodiscussed the meaning of the term peregrinatio. Generally speaking, Aureliusconsidered the term peregrina as the city of God on Earth and the citizens of thiscity as peregrini. According to Augustine the main goal of Christians, onlytemporarily settled on the Earth, was peregrinari ad Dominum3. However,Augustine said that each peregrinus christianus, while living on the Earth, mustobey earthly laws that were common for civitas terrena. These thoughts of oneof the Church fathers were accepted by most subsequent medieval Christiantheologians. His thoughts influenced the development of new ideas connectedto the cult of saints such as imitatio Christi, vita evangelica et apostolica or vitaperfecta, often mentioned in narrative hagiographic sources. In that sensepilgrimage was the daily practice of an ideal Christian way of life while theperegrinus was only a temporary viator in this material world4. The above-mentioned ideas were particularly popular during the Middle Ages, and insome European regions, such as Dalmatia and Istria, this continued into theRenaissance5. The aspiration of Christians to render their daily life as similar aspossible to that of Christ and the apostles is described in contemporaryhistoriography as “inner pilgrimage”6. It was expressed, for instance, throughcharity and solidarity with persons on the margins of society (the poor,widows, prostitutes, foreigners, poor children and girls, and so on), throughasceticism and eremitism and other practical expressions of Christian morals7.These ideas led to so-called introspective Christianity, particularly in the EarlyMiddle Ages and especially among Benedictines and Cistercians. Although theRegulae sancti Benedicti stipulated obligatory acceptance of pilgrims and other

Zoran Ladić

96

2 CLAUSSEN, 1991, p. 33.3 Ibid.4 GEREMEK, 1990, p. 348.5 In his work De institutione bene vivendi, written at the end of the fifteenth century, the famous

humanist writer from Split Mark Marulić extensively examined all the cited terms, particularlythe meaning of imitatio Christi. Marko Marulić, Institucija [Institution], Voll. I-III, 1986-1987.

6 TURNER - TURNER, 1978, p. 7.7 See: CONSTABLE, 1979, p. 45; DANIEL-ROPS, 1957, pp. 47-53.

travellers in Benedictine and Cistercian monasteries, monks from these tworeligious orders were not propagators of pilgrimages to holy Christian shrines.This was probably due to their general wish for isolation from the rest ofChristian society. Therefore, it is not surprising that they absolutely preferredthe idea of peregrinatio in stabilitate to stabilitas in peregrinatione. This means thatthey preferred an introspective spiritual journey towards God to material orearthly travelling through time and space to certain pilgrimage shrines.

Besides purely theoretical opposition, criticism of pilgrimages and pilgrimswas also caused by their inappropriate behaviour (they included prostitutes,murderers, adventurers, bandits, thieves, and so on). Indeed, many pilgrimstravelled not for pious purposes but simply because of their desire to seedistant lands, cities and people, either because of their adventurous spirit or forthe purpose of business. Great international shrines such as Rome, Jerusalemand Saint James in Compostela were visited by tens and even hundreds ofthousands of people. Naturally, among them were many whose behaviour wasnot even close to what was considered that of a proper Christian believer.Therefore, theologians from time to time criticized the practice of pilgrimage.Thus St. Jerome, born in Stridon in Istria and the pride of Dalmatianhumanists, stressed: “it is praiseworthy not to visit Jerusalem but to live goodfor Jerusalem”8. St. Augustine in his work Contra Faustum underlined that Godis in all places and that certain regions or places do not confine Him9. In thetwelfth century Honorius of Autun opposed the practice of pilgrimageexplaining that it was much worthier and much more pious to donate moneyto the poor than spend it on pilgrimages to some distant shrine10. AugustineKažotić, the bishop of Zagreb (around 1260/1265-1323) warned against thevarious atrocities perpetrated by pilgrims during their visits to local pilgrimcentres such as drunkenness and fights11. In one of his letters Amulus, thebishop of Lyon, condemned as inappropriate the bad behaviour of manypilgrims. He wrote that some relics brought to Lyon by pilgrims from the lowerstrata of society were of questionable origin and value and were not evenauthentic. He also condemned superstition, particularly common amongmarried women, girls and older women, who occasionally threw themselves tothe ground in some kind of trance trying to demonstrate the presence of somesupernatural power12. In his work De supersticione from 1262, Stephen deBourbon recorded similar statements regarding pilgrims’ behaviour13. One of

Cap. 4 – Medieval Pilgrims from the Eastern Adriatic Coast to Terra Sancta and Jerusalem

97

8 “Non Hierosolymus fuisse, sed Hierosolymis bene vixisse laudandum est”. CONSTABLE,1979, p. 126.

9 Ibid.10 LE GOFF, 1988, str. 135.11 ŠANJEK, 1993, pp. 358-359.12 See: http://urban.hunter.cuny.edu/~thead/amulo.htm, sub voce: A Letter of Bishop Amulo

of Lyon.13 See: http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/guinefort.html, sub voce: Stephen de

Bourbon (d. 1262), De Supersticione: On St. Guinefort.

the most influential critiques of popular cults of saints and pilgrimages waswritten by abbot Guibert of Nogent in the tract De sanctis et eorum pigneribus14.

Criticism of cults of saints and consequently of pilgrimages and the Pope asthe main propagator and supporter of these pious practices reached its peak inthe late Middle Ages and the beginning of the Early Modern Period, coincidingwith Humanism, Renaissance and later the Protestant reformation. In the middleof the fifteenth century the Croatian humanist John of Česma (Janus Pannonius,1434-1472), a student in Ferrara and Padua and member of the intellectual elite atthe court of Mathias Corvinus, king of Hungary-Croatia, wrote epigrams inwhich he ridiculed pilgrimage to Rome during the Jubilee in 145015.

In his work entitled Enchiridion militis Christiani, Desiderius Erasmus ofRotterdam, one of the most influential humanist writers in the late fifteenth andearly sixteenth centuries, also criticized the practice of pilgrimage in the followingverses: “Is it so great a thing if thou go to Hierusalem in thy body, when withinthine own self is both Sodome, Egypt, and Babylon? … Thou believest perchanceall thy sins and offences to be washed away at once with a little paper orparchment sealed with wax, with a little money or images of wax offered, with alittle pilgrimage going?”16

2. MEDIEVAL PALMARII FROM THE EASTERN ADRIATIC COAST TOJERUSALEM

Like their Western European contemporaries, the medieval inhabitants ofurban and rural settlements on the Eastern Adriatic coast performedpilgrimages to various shrines all over Europe and the Near East. As testifiedin various types of source (narratives, charters, notary records) pilgrimagesfrom the Eastern Adriatic to peregrinations maiores (the Holy Land, Rome, SaintJames in Compostela) and peregrinations minores (local and regional EasternAdriatic shrines as well as shrines in Bari, Loreto, Recanati, Aquileia, Assisi,Mariazell, Aachen, and so on) became popular during the Early Middle Ages.

The earliest data regarding pilgrimage to Jerusalem was recorded by theRagusan chronicler Junius Restić and dated back to 843 when a certain priestnamed Giovanni Arbanese returned from a pilgrimage to Jerusalem and Egypton “una galera Veneziana, tornando d’ Eggito”17. According to Restić, Arbanesebrought certain relics to Dubrovnik in “una cassettina piccola e ben serrata”, the

Zoran Ladić

98

14 See: http://urban.hunter.cuny.edu/~thead/guibert.htm, sub voce: Guibert of Nogent, Onthe Saints and their Relics.

15 See: Ivan Česmički (Ianus Pannonius), Pjesme i epigrami (Poems and Epigrams), p. 319.16 Erasmus of Rotterdam, Enchiridion militis Christiani, 1501. See: http://files.libertyfund.org/

files/191/0048_Bk.pdf, sub voce: Enchiridion militis Christiani, par. XIII, p. 180. There are otherplaces in this book where Erasmus criticizes the practice of pilgrimage. See: Ibid., p. 26.

17 NODILO (ed.), Chroniche di Ragusa. Opera di Giugno Resti, 1893, p. 21: “a Venetian galley,returning from Egypt”.

small chest being kept in the cathedral church of St. Blaise and from 1040 in thepalace of the archbishop of Dubrovnik. When the chest was opened it wasfound to hold “il Pannicello, nel quale fu involto dalla B. Vergine Christo, NostroSignore, bambino, con tutte le autentiche necessarie”18. The relic was later “ripostonel tesoro pubblico, dove le altre reliquie si conservavano”19. Unfortunately, Restić’sis the only extant account of early medieval Eastern Adriatic pilgrimage toJerusalem20.

The examination of pilgrimage to Jerusalem as well as to other shrines iseasier for the period following the establishment of communal notary offices inEastern Adriatic cities, starting from the mid thirteenth century. Particularlyvaluable for research into pilgrimage from Istrian and Dalmatian cities areprivate documents (especially last wills) recorded by communal notaries forpersons from all strata of society regardless of their financial and social status orgender. Pilgrimages to Terra sancta and Jerusalem during the High and LateMiddle Ages were a consequence of the general economic and social prosperityof the Eastern Adriatic cities and towns arising from political stabilization in theregion. Regardless of military conflicts between Venice and the kings ofHungary-Croatia and their magnates in the hinterland of Dalmatia and conflictsbetween Eastern Adriatic cities and Venice and Croatian magnates, in the periodbetween the thirteenth and the beginning of the sixteenth century most urbansettlements on the Eastern Adriatic coast experienced significant legal, economic,urban and architectural development that caused the establishment of richpatrician and middle classes in Poreč, Rab, Zadar, Split, Dubrovnik and othercities. One of the consequences of these historical circumstances was also growthin the number of pilgrims travelling to various pilgrimage sites. During the HighMiddle Ages one of the main pilgrimage destinations was the Holy Land andJerusalem.

3. PEREGRINI CRUCE SIGNATI IN THE EASTERN ADRIATIC SOURCES

It is interesting that the first references to pilgrimages to the Holy Land inthe thirteenth century were explicitly connected to the crusades. It is wellknown that from as early as the late eleventh century the usual term used forcrusader was peregrinus, while the usual term for a crusade to the Holy Landwas peregrinatio in subsidium Terre Sancte. At the council of Clermont in 1096Pope Urban II promised for the first time remissio peccatorum to all men who

Cap. 4 – Medieval Pilgrims from the Eastern Adriatic Coast to Terra Sancta and Jerusalem

99

18 “The swaddling cloth in which Christ Our Lord was wrapped as a baby by the BlessedVirgin Mary, with all the necessary authentication”, (Ivi).

19 Ibidem, p. 22: “placed in the public treasury, where the other relics were conserved”.20 The well-known Evangelistarium from Cividale records the names of several Croatian rulers

and distinguished magnates: Duke Trpimir and his son Peter, Duke Branimir, Bribina, Peter,Mary, Dragovid, and Presila). They went on pilgrimages to Cividale during the middle andsecond half of the ninth century. However, for that period there is still no extant data regardingpilgrims from the lower strata of Croatian society.

joined the crusader army. The crusaders considered this indulgence to meanfull remission of all sins, although neither the Pope nor any other theologiansever explained it that way21. However, just like the early medieval saintly kingsfighting pagans, the crusaders became milites Christi and their life wasregarded as a pilgrimage, at least during the crusades contra infideles Saracenos.The connection between crusaders and remission of all sins developed further,to the point that, for instance, Pope Inocent III promised, as reported byGeoffrey of Villehardouin in his chronicle of the Fourth crusade (1201-1204),“that all who should take the cross and serve in the host for one year, would bedelivered from all the sins they had committed, and acknowledged inconfession. And because this indulgence was so great, the hearts of men weremuch moved, and many took the cross for the greatness of the pardon”22.

The Zaratin and Ragusan notary records from the late thirteenth centuryattest to the successful crusader propaganda of the Franciscans in Dalmatiancities, which was connected to military offensives by Saracens in Palestine andthe fall of the last Christian fortress and port in Holy Land – Acre – in 1291.Even before the fall of Acre, Popes Nicholas IV and Boniface VIII sent threeletters to the minister of the Franciscan province in Dalmatia urging him topromote passagium generale ad liberandum predictam terram de manibus impiorum.Pope Nicholas IV promised indulgentiam salutarem to all those men who wouldaccept signum crucis and join the crusader army to the Holy Land in 129323. Inhis letter addressed to the Spalatin and Zaratin archbishops in 1296, PopeBoniface VIII warned that the Holy Land was being furiously and continuouslyattacked by Saracen military units24.

The promise of remission of all sins and the rapturous Franciscanpropaganda in Eastern Adriatic cities was obviously successful and a numberof men expressed their interest in joining the crusader army to liberate theHoly Land. According to data from Zaratin and Ragusin notary records fromthe last two decades of the thirteenth century, there were altogether 21 testators(persons composing their last wills) who either left bequests for crusades orcomposed their last will because of their wish to personally join the crusaderarmy. Of these, 17 were from Dubrovnik (ten female and seven male testators)and five from Zadar (three male and two female testators). The mainprecondition for personal departure as a crusader to the Holy Land was good

Zoran Ladić

100

21 SMIČIKLAS, Codex diplomaticus regni Croatiae, Dalmatiae et Slavoniae, 1909, doc. 33, p. 41.22 http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/basis/villehardouin.asp. Geoffrey de Villehardouin,

Memoirs or Chronicle of The Fourth Crusade and The Conquest of Constantinople, 1908, pp. 1-2. Itshould be mentioned here that prior to the conquest of Constantinople, in 1202 crusaders alsoattacked and captured another Christian city, Zadar, in order to recoup the costs of Venetiannaval transportation over the sea. After that, Zadar spent several decades under Venetiandominion. BOŽILOV, 2009, pp. 55-67.

23 Ibid., p. 41. See also: SCHMUGGE, 1988, p. 271.24 “Quam Sarracenorum furibunda rabies absque intermissione discerpit.” (SMIČIKLAS, CD.,

doc. 219, p. 248).

physical health. Therefore, only those testators that were corpore sanus wereallowed to go on peregrinatio in subsidium Terre Sancte.

The earliest two wills in which testators bequeathed legacies to the crusadeswere recorded in Dubrovnik. In his last will dated to 1283, Ragusan patricianElias de Restio left yperperi25 viginti et panceria mea to one man who would bewilling to join a future crusader army26. In his will of 1284 another Ragusanpatrician, Dobra de Guerero, donated a certain sum of money to a crusader inthe following way: Et si pasagium de vltra mare non fiet ante obitum meum, denturpost mortem meam yperperi viginti ad dictum passagium quando fiet27. From hiswords it seems that Dobra doubted that a new crusade to the Holy Land wouldever be organized. This is even more obvious from the last will of Elias deRestio, who used the formulation si fuerit transitus generalis, therefore leavingopen another possibility for distribution of his bequest, ordering that if thecrusade non fuerit his money was to be distributed among ecclesiasticalinstitutions and pious causes for the salvation of his soul28.

Zaratin patrician Cosa Saladin composed his last will in 1296, donating 300libras paruorum uni militi willing to join the crusaders (transitus generalis ultramare) in defence of the Holy Land for the salvation of Cosa’s soul29. Cosa alsobequeathed 150 libras paruorum to another crusader, this time for the salvationof the soul of his father’s sister30. Female testators from various social classesalso frequently bequeathed legacies for crusades. For example, Zaratinpatrician Mary de Madio in her last will of 1292 donated the significant sum ofC libre fideliter statim soluantur cum fiet transitus in terra de ultra mare in subsidiumTerre Sancte31 while Zaratin citizen Palmeria, relicta Marci, in her last willcomposed in October 1295 donated libras denariorum paruorum quinquaginta inauxilium Terre (Sancte) quando fiet transitus generalis32. The first Ragusan femaletestator to bequeath a donation for crusades after the fall of Acre in 1291 waspatrician Rada, wife of Marin Rubei, who left yperperos XXX to one crusader33.In her last will recorded in 1298, Ragusan patrician Beatrice, wife of Lawrencede Poueda, bequeathed twenty perpers for the crusade. However, like manyother testators she also doubted whether the crusade would ever be organized

Cap. 4 – Medieval Pilgrims from the Eastern Adriatic Coast to Terra Sancta and Jerusalem

101

25 The Perper was a coin used in medieval Dubrovnik. At the end of the thirteenth centuryone perper was worth approximately half a Venetian golden ducat.

26 LUČIĆ, Monumenta historica Ragusina, II (henceafter MHR II): Zapisi notara Tomazina de Savere1282-1284, 1984, p. 333.

27 Ibid., p. 374.28 Ibid., p. 333.29 ZJAČIĆ, Spisi zadarskih bilježnika Henrika i Creste Tarallo, I (henceforth SZB I), 1959, pp. 85-90.

At the end of the thirteenth century one ducat was worth a little more than two libre, exactly twolibre and 12 solids or 52 solids. Thus, Cosa donated the impressive sum of 115 golden ducats.

30 Approximately 57.5 golden ducats. Ibid. 31 Ibid., pp. 67-68.32 Ibid., p. 82.33 LUČIĆ, Monumenta historica Ragusina, IV (henceforth MHR IV): Zapisi notara Andrije Beneše

1295-1301, 1993, p. 266.

and therefore she added the following words - si pasagium vero non fuerit, dictyyperperi dentur pro anima mea34. In the same spirit, patrician Slava, relicta MariniBinçola, left ten perpers in support of a crusade. But, in the spirit of “socialChristianity” and increasing empathy for persons on margins of urbansocieties, she ordered that, if the crusade non fuerit, the above-mentioned tenperpers were to be spent on vestiantur leprosi35. Besides monetary legacies, somemale testators donated their weapons, armour and shields. For instance, in hiswill of 1298, Ragusan patrician Ursacius de Guberico donated yperperos XIIII etarma to one crusader quando erit primum pasaçium36, while Michael de Gherdusioin his will of 1295 bequeathed twenty perpers and omnia arma mea ferea37.Perhaps the most striking example of a donation of armour and weapons isrecorded in the last will of Ragusan patrician Pasqua de Zereua who bequeathedscutum unum et spatam meam et baciletum et panceriam unam de yperperis octo etpar unum de gamberiis et colare unum et par unum de ghuantis de malla38. Since themain precondition for joining the crusade was physical health it is no wonderthat only two out of all the examined Zaratins and Ragusans from that periodpersonally went to Jerusalem and the Holy Land, either to join a crusader armyor just to visit pilgrimage shrines. Thus, Zaratin citizen Stojko, son of Nicholas,recorded his last will in May 1291 intendens ire ad exercitum in Holy Land39

while Zaratin patrician Thomas de Penaço only indeterminately mentioned thathe composed his will intendens ire ultra mare40. As mentioned above, enthusiasticsupport for crusades to the Holy Land as a form of pilgrimage may be found inlast wills of testators from all strata of Ragusan and Zaratin communalsocieties. Thus, a certain Ragusan magister Petrus petrarius in his last willcomposed in 1299 bequeathed yperperi XXV pro pasagio41, the priest Rosinus,son of Balislaue ordered in 1295 si pasagium fuerit, mitatur homo unus pro unoanno cum illis armis que superius dixi42, while the priest Barbius de Gore in 1296also bequeathed the rather humble sum of yperperi XXV pro pasagio43.

It may be concluded that military and political circumstances, above all thesuccessful Saracen military offensives in the Holy Land from the middle of thethirteenth century until the fall of Acre, caused significant changes in thetestamentary bequests of Dalmatian testators, who expressed financial supportfor peregrinatio in subsidium Terre sancte but also occasionally joined otherDalmatians in the crusader armies.

Zoran Ladić

102

34 Ibid., p. 336.35 Ibid., p. 295.36 Ibid., p. 264.37 Ibid., p. 271.38 ČREMOŠNIK, Monumenta historica Ragusina, I (henceforth MHR I): Spisi dubrovačke kancelarije,

knjiga I, Zapisi notara Tomazina de Savere 1278-1282, 1951, p. 274.39 ZJAČIĆ, SZB I, p. 52.40 Ibid., p. 66.41 LUČIĆ, MHR IV, p. 343.42 Ibid., p. 269.43 Ibid., p. 290.

4. THE FLOURISHING OF PILGRIMAGES TO THE HOLY LAND ANDJERUSALEM IN THE LATE MIDDLE AGES

The fall of the entire Holy Land under the dominion of Muslim rulers did notcause a decrease in the number of Christian palmarii to Jerusalem and otherpilgrim shrines in Palestine. On the contrary, as testified in various late medievalsources, pilgrimages from Europe to the Holy Land and Jerusalem became morepopular than ever before, primarily because of the better organization of thenetwork of pilgrimage roads and increasing safety of naval and land routes. Theperiod between the fourteenth and the beginning of the sixteenth century wasalso characterized by the improvement and reconstruction of ancient roads. Theestablishment of a secure network of main roads leading to all major pilgrimagesites such as Rome and St. James in Compostela, together with the establishmentof inns and hospitals along these roads, enabled more comfortable and securejourneys not only for pilgrims from the upper classes but also from the lowerstrata of late medieval society. Therefore, from the fourteenth century onwards,pilgrimage saw a general social and gender democratization, and Jerusalembecame a pilgrimage destination for rich and poor and men and women alikefrom all over Europe. This process may also be observed in the late medievalurban societies of the Eastern Adriatic coast. The great advantage for Istrian andDalmatian pilgrims lay in the fact that the main naval route to the Holy Land,which started in Venetian ports, went for a thousand kilometres along theEastern Adriatic coast and many pilgrims from that region could easily boardVenetian pilgrim or merchant galleys sailing towards Mediterranean ports inPalestine. The above-mentioned social and gender democratization in thepractice of pilgrimage to Terra sancta is best illustrated by the fact that during theLate Middle Ages palmarii were equally likely to be lay or clergy, rich or poor,men or women.

5. PALMARII - MEN AND WOMEN, LAY AND CLERGY, RICH AND POOR

As discussed in the previous chapter, until the beginning of the fourteenthcentury most pilgrims to Jerusalem and the Holy Land were men, mainly fromthe upper and wealthier strata of society (rulers, magnates, patricians,crusaders, diplomats, merchants, and so on). Of course, kings and magnateswere often accompanied by their wives and courtiers. In the Late Middle Agesthe circumstances significantly changed. The period from the fourteenthcentury until the end of the fifteenth century was characterized by the muchgreater presence of Istrian and Dalmatian women travelling to Palestine andJerusalem. On the one hand, this was the consequence of the reconstruction oftraditional, centuries-old land routes organized into networks enablingrelatively safe pilgrimage to the Holy Land. Thus, pilgrims belonging toOrthodox Churches arriving from Russia, Bulgaria or Georgia travelled almostentirely by road. In contrast, pilgrims from Western and Central Europe only

Cap. 4 – Medieval Pilgrims from the Eastern Adriatic Coast to Terra Sancta and Jerusalem

103

partially travelled by land; after reaching Venice or some other importantNorth Mediterranean port they boarded galleys to the Holy Land which theyreached after a voyage of thirty to sixty days. In good weather the voyage fromVenice to Kotor, which was the first phase of the journey, lasted two weeks,whereas in poor weather the same journey lasted one week more44. On theother hand, the much greater participation of women in pilgrimages toJerusalem was a consequence of the rise of a new class of rich citizens,particularly merchants, artisans and artists, in the cities of Istria and Dalmatiain the fourteenth century. Reflecting the pious habits of local patricians, womenfrom this stratum of communal society suddenly emerge in the sources aspilgrims to various shrines all over Europe and the Holy Land. In that periodthe costs of pilgrimage were not an issue because their husbands earnedenough money not only for the everyday needs of their families andhouseholds but also for pious purposes. Besides financing pilgrimages by theirwives and daughters, they started to invest in buying books and orderingartistic pieces such as votive images, reliquaries, and so on. Thus, afterreceiving their travel documents and permission from the local bishops orarchbishops, during the fourteenth and fifteenth century more and morewomen travelled to various pilgrim shrines. To a certain degree, the latethirteenth century and entire fourteenth century represent a period in whichwomen were allowed for the first time, at least in Istria and Dalmatia, toexperience free mobility, something that until that period had been theexclusive domain of men. For the first time women were able to escape thenarrow confines of their domestic and city walls and to travel to distantpilgrimage sites thousands of kilometres away. The main preconditionscausing the appearance of that type of democratization were clearly the legaland ecclesiastical development of urban societies in Istria and Dalmatia.

For the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries there are records for a totalof 110 pilgrims from Zadar visiting pilgrimage shrines in Jerusalem, liminaapostolorum Petri et Pauli in Rome45, St. James in Compostela46, Assisi, Recanati,Bari and many other sites all over Europe. However, it is interesting that arelatively small group of twelve Zaratin pilgrims travelled to Jerusalem. This

Zoran Ladić

104

44 LADIĆ, 1993, pp. 20-21.45 After pope Boniface VIII proclaimed the first Jubilee year, large numbers of European and

East Adriatic pilgrims chose Rome as their pilgrimage destination. Interestingly, the first papaldecision was that the Jubilee was to be celebrated every fifty years, then 33, and finally every 25years. According to some estimates, during the Jubilee year Rome was visited by more than tenthousand pilgrims from the German lands alone. On the influence of the proclamation of Jubileeyears on the number of pilgrims in Rome see: Schmugge, 1995, pp. 104-109. See also: Idem, 1988,pp. 266-267, 272-273, 275-276. According to Schmugge, in the same period, only three to fivehundred German pilgrims travelled yearly to Jerusalem. SCHMUGGE, 1995, p. 266.

46 Dalmatian pilgrims were especially attached to that distant pilgrimage shrine because inalmost all Dalmatian cities there were confraternities dedicated to St. James whose main purposewas to take care of foreign pilgrims.

seems understandable given that although Jerusalem was the locus sanctissimusand primus among all pilgrim shrines, travel expenses were relatively high. Thejourney itself was long and possibly full of danger, since the Holy Land wasnow under the dominion of the Saracens and there were neither KnightsTemplar nor Knights Hospitaller, the military orders which in previouscenturies were the chief defenders of European pilgrims in the Holy Land. Thefirst pilgrim from Zadar to Jerusalem and the Holy Land recorded in thesources for that period was the patrician Thomas de Penaço, who composed hislast will in 1291 intendens ire ultra mare, that is to the Holy Land47. Four yearslater, in 1295, the patrician Vitus de Cerna Galellis recorded his will per Deigratiam conpos mentis et corporis, intendens domino Iesu Christo concedente me cumtribus galeis Venetis ad longinquas partes transferre48. A century later most palmariistill belonged to the group of patricians. Thus, in 1404 ser Damian de Cipriano,nobilis ciuis Iadre, decided to visit the Holy Land expressing his pious reasons inthe following way: intendens causa deuotionis sacrosanctum sepulcrum domininostri Iesu Christi in Ierusalem uisitare49. However, the above-mentioned processof democratization of pilgrimage from the point of view of the pilgrims’ socialand financial status is obvious in the last will written in 1375 for the poorZaratin mariner Gregory, who made his will affectantis Sanctum SepulcrumIerosolymis visitare50. As testified in Zaratin sources, foreigners who lived inZadar for long periods also went on pilgrimages to Jerusalem. Thus, forexample, the Italian Nicholas de Feltre, habitator Iadre, recorded his last will in1383 after making the decision ad terram sanctam sepulcrum domini uisitaturusopporteat proficisci, dubitans hora mortis ne ea preuentur abintestato decedat51.

In other Eastern Adriatic cities the number of pilgrims to the Holy Land wassmaller and they are only occasionally mentioned in the sources. Nevertheless,traces of pilgrimages to Terra sancta may be found in the sources from Rab,Šibenik, Krk, and some other cities. As recorded in one source written in theGlagolitic script at the beginning of the fifteenth century, Croatian magnateNicholas Frankapan, the count of the island and city of Krk off the Croatiancoast, went on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem in April 1411 and returned from theHoly Land in July of the same year52. For that purpose Nicholas rented aVenetian galley and, typically for wealthy and powerful magnates at that time,his retinue, knights and soldiers accompanied him53. In his last will of 1450

Cap. 4 – Medieval Pilgrims from the Eastern Adriatic Coast to Terra Sancta and Jerusalem

105

47 ZJAČIĆ, SZB I, p. 66.48 DOKOZA, 2002, pp. 256-260.49 State Archive in Zadar (henceforth SAZ), Records of Zaratin notaries (henceforth RZN),

Articutius de Riuignano (henceforth AR), b. 5, fasc. 2, nr. 47.50 Archive of the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts (henceforth ACASA). Guerrin

Ferrante, II.a.43, fol. 10.51 SAZ, RZN, Iohannes de Casulis (henceforth IC), b. 1, fasc. 3/1, pp. 86-87.52 MASLAĆ, 1930, pp. 177-189.53 Ibid. In 1430 Nicholas went on a pilgrimage to Rome and a diplomatic visit to Pope Martin

V crossing the Adriatic sea on an Anconitan galley. MARGETIĆ, 1990, p. 68.

Peter de Zaro, one of the richest and most influential patricians in the city ofRab in the fifteenth century, bequeathed donations for four pilgrimages - vnapersona ad sanctum sepulcrum et vna alia persona ad ecclesiam sancti Jacobi de Galitiaet vna persona Romam et vna persona ad Assisium, all of them for salvation of hissoul54. In another last will recorded in 1456 Peter donated forty ducats to aperson who would go to Jerusalem pro anima sua55. Peter’s wife Mary, nobilisdomina Arbi, in her last will of 1464 also left a donation for a pilgrim whowould visit sanctum sepulchrum in Jerusalem for the salvation of her soul56.Mary ordered the executors of her last will to sell all her houses in Zadar andall her estates situated near Zadar and to give the money for pilgrimages toJerusalem, Rome, ad sanctum Franciscum de Assissio, and ad sanctum Bernardinumde Aquila57. A notary document from 1477 testifies that Mary’s wish wasfulfilled. Namely, according to data from that document, a patrician of Rabwho was the executor of Mary’s last will Cressius de Dominis gave forty threeducats to a priest of Rab John Ilijanić after John’s decision to go on a pilgrimagead sanctum Sepulcrum pro anima dicte Marie58. Another inhabitant of Rab, thepriest Thomas de Cancarella, composed his last will in 1452 after making thedecision to go on a pilgrimage ad sanctum sepulcrum Domini et timens naufragiaque inde euenter possent59. Catharine, vxor quondam magistri Stefani Radinouichcerdonis and citizen of Šibenik, who composed her last will in 1456 in favour ofa pilgrimage to St. James in Compostela, following the wish of her latehusband, bequeathed one hundred ducats pro duobus peregrinis mittendis,videlicet ad sanctum Iacobum in Galicia et ad sepulcrum Christi. Bearing in mindthe differences in distance between the two pilgrim shrines as well asdifferences in travel and accommodation costs, she left only twenty ducats forthe pilgrimage to St. James in Compostela and eighty ducats for the pilgrimagead sepulcrum Iesu Christi60. In his diary written in 1482, Franciscan palmariusPaul Walter Guglingen stated that during his pilgrimage to Jerusalem he wasaccompanied by an unknown married couple from Croatia. Unfortunately,somewhere between Ramala and Jerusalem the husband died and wasimmediately buried in the desert in the Muslim graveyard61.

Zoran Ladić

106

54 SAZ, Records of Rab’s Notaries (henceforth RRN), Toma Stančić (henceforth TS), kut. 2, sv.4, fol. 1168-1169/a.

55 SAZ, RRN, TS, kut. 2, sv. 8, fol. 108-110.56 SAZ, RRN, TS, kut. 2, sv. 11, fol. 177-178.57 Ibid.58 SAZ, RRN, Andrija Fajeta (henceafter AF), kut. 1, sv. 10, fol. 13a.59 SAZ, RRN, TS, kut. 2, sv. 6, fol. 55a-56.60 SAZ, Records of Šibenik’s Notaries, Karotus Vitale (henceforth KV), kut. 16/II, sv. 15.IVa,

fol. 88’.61 “Demum asinavimus per terram planam et campestrem, fertilem, non petrosam versus

Iherusalem, et distat a Rama 30 miliaria. Et venimus sero usque ad ascensum montium et ibistetimus per noctem in campis. Et quidam peregrinus de partibus Slavonie in nocte illa mortuusest presente sua uxore, que multum anxiata est et cum dolore maximo reliquit virum, quemmultum amabat, inter gentiles sepelire in campis”. Fratris Pauli Waltheri Guglingensis Itinerariumin terram sanctam et ad sanctam, pp. 108-109.

As is obvious from this short presentation of pilgrimages from the EasternAdriatic coast to Jerusalem and the Holy Land, the most sacred places ofChristianity, the practice remained popular among lay men and womenthroughout the Late Middle Ages. Regardless of the fact that pilgrimage adsanctum sepulchrum was dangerous and very expensive, and regardless of theincreased popularity of Rome as a pilgrimage site because of the morefrequently proclaimed Jubilees, there were still many believers ready to risktheir lives in order to visit the locus sanctissimus of Christendom.

The sources show that the largest group of late medieval Eastern Adriaticpilgrims to Jerusalem was the clergy. Certainly the most famous EasternAdriatic palmarius was Nicholas, a member of Šibenik’s patrician familyTavelić. After entering the Franciscan order Nicholas studied philosophy andtheology in Zadar and Split and after serving as a missionary in Bosnia in 1383he went to St Catharine’s monastery on Mount Sinai where he learned Arabic.He was executed in Jerusalem after trying to convert the local Muslimpopulation62. In 1392 a certain friar Mark, abbot of the convent of St. Francis inthe city of Krk, promised to go on an ex voto pilgrimage to Jerusalem and todonate, according to the wish of Rijeka’s patrician Nicholas, one hundredducats to the above-mentioned monastery on Mount Sinai. There is no furtherinformation on whether Mark fulfilled his promise63. The Zaratin priest JohnÇoccholich, officians in ecclesia sancti Stephani de Iadra, recorded his last will in1404, volens peregrinari et ire vltra mare ad visitandum sanctissimum seppulcrumdomini nostri Iesu Christi in Ierusalem, timens ne aliquid sinistri de ipso aduciant64.In 1418 the Franciscan friar George Ivanov from Zadar, who had already beento Jerusalem, tried to collect money for his pilgrimage to Mount Sinai65; in 1440Kreško, archpriest of Nin near Zadar, went on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land66;in 1453 the Dominican friar John from Dubrovnik, after receiving permissionfrom the Dalmatian Dominican minister, went on a pilgrimage to the HolyLand together with his companion67; in 1463 Zaratin canon Lucas Stipziobtained papal permission to go on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land68; in 1480the Dominican friars Francis from Kotor and Dominik from Dubrovnik wenton a pilgrimage to Jerusalem together with Felix Fabri, a Dominican friar fromSwitzerland69; in 1483 the above-mentioned Paul Walter Guglingen wroteabout his encounter with two Franciscan friars from Croatia in the middle ofthe Sinai desert – one called James maior from Slavonia and another calledJames minor from Šibenik – who were travelling from Jerusalem to the

Cap. 4 – Medieval Pilgrims from the Eastern Adriatic Coast to Terra Sancta and Jerusalem

107

62 He was canonized in 1970 during the pontificate of Pope Paul VI.63 CRNČIĆ, Što je pisama sakupio P. Blagoslav Bartoli, 1888, pp. 1, 13, 14; Runje, 1995, p. 263.64 SAZ, RZN, Vannes Bernardi de Firmo (henceforth VBF), b. 2, fasc. 2, nr. 55.65 RUNJE,1999, p. 302.66 RUNJE, 1997, nr. 39, p. 91.67 KRASIĆ, Regesti pisama generala dominikanskog reda poslanih u Hrvatsku (1392-1600), 1976, p.

169.68 NERALIĆ, 2007, p. 364.69 KRASIĆ, 2001, p. 162.

monastery of St Catharine on Mount Sinai70; the Dominicans James fromDubrovnik in 1492 and Ambrose from Dubrovnik in 1494 received permissionto go on pilgrimages to the Holy Land71. The first female member of theEastern Adriatic clergy documented in the sources as going on a pilgrimage toJerusalem was a certain Margaret, a member of the Franciscan Third Order,who departed in 1515 ad sanctum sepulchrum72.

In the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries the first pilgrims’ diariesand itineraries written by Eastern Adriatic pilgrims to the Holy Land began toappear. Thus in 1480 Paul da Stridone in Istria wrote Santo Viaggio in TerraSancta, in 1523 John di Gondola from Dubrovnik published Tabula Terrae Sancte,in 1526 the same John Gundulić wrote Itinerario a pellegrinaggio in Tera Santa, in1553 Bartholomew Đorđević from Dubrovnik published in Rome his Memoirsin Italian, and in 1566 the same author published in Rome Specchio de’bocchi sandi Terra Santa. Under the influence of Renaissance and Humanist thought, theappearance of this new literary genre in Croatia also marks significant changesin the experience of pilgrimages, which were now considered not only as piousor penitentiary journeys but also as adventurous and intellectual travels, whichalso inspired the appearance of so-called road novels and picaresque literature,in which vagabonds and leisure were important literary motifs.

* * *

In conclusion it may be said that the inhabitants of Eastern Adriatic citiesand towns actively participated in medieval Christian pilgrimages to Terrasancta and Jerusalem. As testified in the sources, in the mid-medieval periodpilgrimages to the Holy Land were the privilege of the highest and mostpowerful members of Eastern Adriatic societies. Only the wealthiest of thespiritual and lay pilgrims were in a position to go on pilgrimages to Jerusalem,the most sacred Christian shrine. Yet the early thirteenth century saw the startof a process of democratization, in the sense that, as documented in extantsources, believers from all strata of Eastern Adriatic societies appear as palmariito the Holy Land. In the thirteenth century most pilgrims to Terra sancta werestill male and from the higher social classes, often participating in crusades asperegrini cruce signati. After the end of the thirteenth century, when the lastChristian forts in Palestine fell into the hands of the Saracens, the idea ofperegrinatio in subsidium Terre sancte significantly declined, at least among thelay population. During the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries a new group ofpilgrims to the Holy Land appears more often in the sources – women. Until

Zoran Ladić

108

70 Fratris Pauli Waltheri Guglingensis Itinerarium in terram sanctam et ad sanctam, p. 214.71 KRASIĆ, 1976, pp. 227, 231.72 DE DIESBACH, 1893, p. 272.

then mobility was almost exclusively associated with men, either clerics or layfigures such as diplomats, soldiers, intellectuals, merchants, artists or artisans.However, from the fourteenth century onwards, the number of female pilgrimsto the Holy Land significantly increased and, at least as far as the EasternAdriatic is concerned, female pilgrims to Jerusalem became as numerous astheir male contemporaries. A very important factor in the general growth ofpalmerii from the Eastern Adriatic coast to the Holy Land was the convenientgeographical position of this region on the main naval routes from Venice toPalestine. There is much written evidence (in diaries, chronicles, travelaccounts) describing ecclesiastical, cultural, intellectual, economic and artisticcontacts between European pilgrims and the peoples of the Eastern Adriatic.Such contacts, most often expressed through peaceful communication andthrough the exchange of constructive ideas, influenced the growth of EasternAdriatic pilgrims to Jerusalem as locus sanctissimus among all Christian shrines.

Cap. 4 – Medieval Pilgrims from the Eastern Adriatic Coast to Terra Sancta and Jerusalem

109

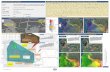

Fig. 1. East-Adriatic pilgrimages to Jerusalem in the Middle Ages.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

I. Sources

Archive of the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts. Guerrin Ferrante, II.a.43.Ivan Česmički (Ianus Pannonius), “Pjesme i epigrami” (“Poems and Epigrams”), ed.

NIKOLA ŠOP, in Hrvatski latinisti, 2, Zagreb, 1951.ČREMOŠNIK G., Monumenta historica Ragusina, vol. I: Spisi dubrovačke kancelarije, knjiga I,

Zapisi notara Tomazina de Savere 1278-1282 [Notary records of Thomas de Savere 1278-1282], Zagreb, 1951.

Fratris Pauli Waltheri Guglingensis Itinerarium in terram sanctam et ad sanctam Catharinam(herausg. M. SOLLWECK), Tübingen, 1892.

Geoffrey de Villehardouin, Memoirs or Chronicle of The Fourth Crusade and The Conquest ofConstantinople, trans. F. T. MARZIALS, J. M. DENT, London, 1908.

LUČIĆ J., Monumenta historica Ragusina, vol. II. Zapisi notara Tomazina de Savere 1282-1284[Records of Notary Thomas de Savere], Zagreb, 1984.

LUČIĆ J., Monumenta historica Ragusina, vol. IV: Zapisi notara Andrije Beneše 1295-1301,[Records of Notary Andrew Beneša 1295-1301], Testamenta 1295-1301, Zagreb, 1993.

Marko Marulić, Institucija [Institution], Vol. I-III, ed. B. GLAVIČIĆ, Split, 1986-1987.NODILO S. (ed.), “Chroniche di Ragusa. Opera di Giugno Resti”, in Monumenta spectantia

historiam Slavorum Meridionalium 25, Scriptores, vol. II, Zagreb, 1893.SMIČIKLAS T., Codex diplomaticus regni Croatiae, Dalmatiae et Slavoniae, vol. VII, Zagreb,

1909.State Archive in Zadar, Records of Rab’s Notaries, Andrija Fajeta, kut. 1, sv. 10.State Archive in Zadar, Records of Rab’s Notaries, Toma Stančić, kut. 2, sv. 4.State Archive in Zadar, Records of Šibenik’s Notaries, Karotus Vitale, kut. 16/II, sv. 15. IVa.State Archive in Zadar, Records of Zaratin notaries, Articutius de Riuignano, b. 5, fasc. 2.State Archive in Zadar, Records of Zaratin notaries, Iohannes de Casulis, b. 1, fasc. 3/1;ZJAČIĆ M., Spisi zadarskih bilježnika Henrika i Creste Tarallo [Notary records of Zaratin

notaries Henry and Creste Tarallo], vol. I, Zadar, 1959.

II. Literature

BOŽILOV I. (2009), “Zadar i Četvrti križarski rat [Zadar and the Fourth Crusade]”, inRadovi Zavoda za povijesne znanosti HAZU u Zadru, vol. 51/2009, pp. 55-67.

CLAUSSEN M. A. (1991), “Peregrinatio and Peregrini in Augustine’s City of God”, inTraditio. Studies in Ancient and Medieval History, Thought, and Religion, XLVI, 1991, pp.33-75.

CONSTABLE G. (1979), “Opposition to Pilgrimage in the Middle Ages”, in IDEM, ReligiousLife and Thought (11th – 12th Centuries), IV, London: Variorum Reprints, pp. 125-146.

CRNČIĆ I. (1888), “Što je pisama sakupio P. Blagoslav Bartoli” [Letters collected by P.Blagoslav Bartoli], in Starine JAZU, XX, pp. 1-21.

DANIEL-ROPS H. (1957), Cathedral and Crusade. Studies of the Medieval Church 1050 – 1350,London: J. M. Dent & Sons LTD.

DE DIESBACH M. (1891), “Les Pèlerins fribourgeois à Jérusalem (1436-1640)”, Archives dela Société d’histoire du Canton de Fribourg, V, Fribourg.

GEOFFREY DE VILLEHARDOUIN, Memoirs or Chronicle of The Fourth Crusade and The Conquestof Constantinople, 1908, pp. 1-2

DOKOZA S. (2002), “Inventar fonda don Kuzme Vučetića u Državnom arhivu u Zadru

Zoran Ladić

110

[The inventory of don Kuzma Vučetić in the State archive in Zadar]”, in Prilozipovijesti otoka Hvara, XI, pp. 256-260.

GEREMEK B. (1990), “The Marginal Man”, in J. LE GOFF (ed.), Medieval Callings, Chicago:The University of Chicago Press, pp. 347-374.

http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/guinefort.html, sub voce: Stephen deBourbon (d. 1262), De Supersticione: On St. Guinefort.

KRASIĆ S. (2001), “Opis hrvatske jadranske obale u putopisima švicarskog dominikancaFeliksa Fabrija (Schmida) iz 1480. i 1483/84. godine” [Description of CroatianAdriatic Coast in travelling accounts by Felix Fabri, Dominican from Switzerland], inAnali Zavoda za povijesne znanosti HAZU u Dubrovniku, XXXIX, pp. 133-216.

KRASIĆ S. (1976), Regesti pisama generala dominikanskog reda poslanih u Hrvatsku(1392-1600)” [Regests of Letters of Generals of Dominican Order adressed to Croatia(1392-1600)], in Arhivski vjesnik, 17-18, pp. 201-321.

LADIĆ Z. (1993), “Prilog proučavanju hodočašćenja iz Zadra u drugoj polovici XIV.stoljeća” [Contribution to the research of pilgrimages from Zadar in the second halfof the fourteenth century], in Croatica Christiana Periodica, 32/XVII, Zagreb, pp. 17-31.

LE GOFF J. (1988), Medieval civilization, 400-1500, Oxford-New York: B. Blackwell.MARGETIĆ L. (1990), “Počeci prošteništa i franjevačkog samostana na Trsatu” [The

Beginnings of Pilgrim Shrine and Franciscan convent on Trsat], in Croatica ChristianaPeriodica, XIV, 25, pp. 66-77.

MASLAĆ, N. (1930), “Hrvatski knezovi Frankopani prema kat. Crkvi” [Croatian CountsFrankopan towards the Catholic Church], in Život, XI, pp. 177-189.

NERALIĆ J. (2007), Put do crkvene nadarbine – rimska Kurija i Dalmacija u 15. stoljeću [TheWay to Ecclesiastical Donation – Roman Curia and Dalmatia in the FifteenthCentury], Split.

RUNJE P. (1995), “Svećenici ‘glagoljaši’ u 15. stoljeću u Svetoj zemlji” [‘Glagolitic’ priestsin the Fifteenth century in Holy Land], in Riječki teološki časopis, 3/2, 1995.

RUNJE P. (1997), “Lazaret u predgrađu srednjovjekovnog Zadra i njegovi kapelani”[Leprosory in the Outskirt of Zadar and ist Chaplains], in Radovi Zavoda za povijesneznanosti HAZU u Zadru, 39, pp. 81-116.

RUNJE P. (1999), “Hrvatski franjevci trećoreci hodočasnici u srednjem vijeku” [CroatianFranciscans of Third Order as pilgrims in the Middle Ages], in Riječki teološki časopis,7/2, pp. 301-306.

ŠANJEK F. (1993), Crkva i kršćanstvo u Hrvata: srednji vijek [Church and Christianityamong Croats: The Middle Ages], Zagreb: Kršćanska sadašnjost.

SCHMUGGE L. (1988), “Kollektive und individuelle Motivstrukturen im mittelalterlichenPilgerwesen”, in G. JARITZ and A. MÜLLER (eds.), Migration in der Feudalgesellschaft,Frankfurt-New York, pp. 263-289.

SCHMUGGE L. (1995), “Deutsche Pilger in Italien”, in S. DE RACHEWILTZ and J. RIEDMANN(eds.), Kommunikation und Mobilität im Mittelalter. Begegnungen zwischen dem Südenund der Mitte Europas (11.-14. Jahrhundert), Sigmaringen, pp. 97-113.

TURNER V. - TURNER E. (1978), Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture: AnthropologicalPerspectives, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cap. 4 – Medieval Pilgrims from the Eastern Adriatic Coast to Terra Sancta and Jerusalem

111

Related Documents