THE MAPUTO BAY ECOSYSTEM Editors Salomão Bandeira | José Paula

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

Book title:The Maputo Bay Ecosystem.

Editors:Salomão BandeiraJosé Paula

Assistant Editor:Célia Macamo

Book citation:Bandeira, S. and Paula, J. (eds.). 2014. The Maputo Bay Ecosystem. WIOMSA, Zanzibar Town, 427 pp.

Chapter citation example:Schleyer, M. and Pereira, M., 2014. Coral Reefs of Maputo Bay. In: Bandeira, S. and Paula, J. (eds.), The Maputo Bay Ecosystem. WIOMSA, Zanzibar Town, pp. 187-206.

ISBN: 978-9987-9559-3-0© 2014 by Western Indian Ocean Marine Science Association (WIOMSA)Mizingani Street, House No. 13644/10P.O. Box 3298, Zanzibar, Tanzania.Website: www.wiomsa.orgE-mail: [email protected]

All rights of this publication are reserved to WIOMSA, editors and authors of the respective chapters. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the editors and WIOMSA. The material can be used for scientific, educational and informational purposes with the previous permission of the editors and WIOMSA.

This publication is made possible by the generous support of Sida (Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency) through the Western Indian Ocean Marine Science Association (WIOMSA). The contents do not necessarily reflect the views of Sida.

Design: Marco Nunes Correia | designer of comunication and scientific illustrator | [email protected]: credits referred in respective legends.Printed by: Guide – Artes Gráficas, Lda. (www.guide.pt)Printed in Portugal

T h e M a p u t o B a y E c o s y s t e m XVII

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Foreword by the Rector of UEM

Foreword by the President of WIOMSA

Acknowledgements

List of contributors

PART I ENVIRONMENTAL AND HUMAN SETTING

Chapter 1. AN INTRODUCTION TO THE MAPUTO BAY

José Paula and Salomão Bandeira

Chapter 2. GEOGRAPHICAL AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC SETTING OF MAPUTO BAY

Armindo da Silva and José Rafael

Case Study 2.1. Maputo Bay’s coastal habitats

Maria Adelaide Ferreira and Salomão Bandeira

Case Study 2.2. Main economic evaluation of Maputo Bay

Simião Nhabinde, Vera Julien and Carlos Bento

Chapter 3. GEOMORPHOLOGY AND EVOLUTION OF MAPUTO BAY

Mussa Achimo, João Alberto Mugabe, Fátima Momade and Sylvi Haldorsen

Case Study 3.1. Erosion in Maputo Bay

Elidio A. Massuanganhe

Chapter 4. HYDROLOGY AND CIRCULATION OF MAPUTO BAY

Sinibaldo Canhanga and João Miguel Dias

Case Study 4.1. Maputo Bay offshore circulation

Johan R.E. Lutjeharms† and Michael Roberts

Case Study 4.2. Ground water flow in/into Maputo Bay

Dinis Juízo

Chapter 5. HUMAN SETTINGS IN MAPUTO BAY

Yussuf Adam, Júlio Machele and Omar Saranga

1

3

11

21

25

31

39

45

55

61

67

XVIII T h e M a p u t o B a y E c o s y s t e m

Chapter 6. INHACA ISLAND: THE CRADLE OF MARINE RESEARCH IN MAPUTO BAY

AND MOZAMBIQUE

Salomão Bandeira, Lars Hernroth and Vando da Silva

Case Study 6.1. The role of SIDA/SAREC on research development in Maputo Bay during the

period 1983-2010

Almeida Guissamulo and Salomão Bandeira

Case Study 6.2. Inhaca and Portuguese islands reserves and their history

Salomão Bandeira, Tomás Muacanhia, Olavo Deniasse and Gabriel Albano

PART IIMAIN HABITATS AND ECOLOGICAL FUNCTIONING

Chapter 7. MANGROVES OF MAPUTO BAY

José Paula, Célia Macamo and Salomão Bandeira

Case Study 7.1. Incomati mangrove deforestation

Celia Macamo, Henriques Baliddy and Salomão Bandeira

Case Study 7.2. Saco da Inhaca mangrove vegetation mapping and change detection using very

high resolution satellite imagery and historic aerial photography

Griet Neukermans and Nico Koedam

Case Study 7.3. The mud crab Scylla serrata (Forskål) in Maputo Bay, Mozambique

Adriano Macia, Paula Santana Afonso, José Paula and Rui Paula e Silva

Case Study 7.4. Crab recruitment in mangroves of Maputo Bay

José Paula and Henrique Queiroga

Chapter 8. SEAGRASS MEADOWS IN MAPUTO BAY

Salomão Bandeira, Martin Gullström, Henriques Balidy, Davide Samussone and Damboia Cossa

Case Study 8.1. Zostera capensis – a vulnerable seagrass species

Salomão Bandeira

Case Study 8.2. Thalassodendron leptocaule – a new species of seagrass from rocky habitats

Maria Cristina Duarte, Salomão Bandeira and Maria Romeiras

Case Study 8.3. Morphological and physiological plasticity of the seagrass Halodule uninervis at

Inhaca Island, Mozambique

Meredith Muth and Salomão Bandeira

Chapter 9. CORAL REEFS OF MAPUTO BAY

Michael Schleyer and Marcos Pereira

87

99

101

107

109

127

131

135

141

147

171

175

181

187

XIXT h e M a p u t o B a y E c o s y s t e m

Table of Contents

Case Study 9.1. Shrimps in coral reefs and other habitats in the surrounding waters of Inhaca Island

Matz Berggren

Chapter 10. MARINE MAMMALS AND OTHER MARINE MEGAFAUNA OF MAPUTO BAY

Almeida Guissamulo

Case Study 10.1. Seagrass grazing by dugongs: Can habitat conservation help protect the dugong?

Stela Fernando, Salomão Bandeira and Almeida Guissamulo

Chapter 11. MARINE TURTLES IN MAPUTO BAY AND SURROUNDINGS

Cristina Louro

Chapter 12. THE TERRESTRIAL ENVIRONMENT ADJACENT TO MAPUTO BAY

Salomão Bandeira, Annae Senkoro, Filomena Barbosa, Dalmiro Mualassace and Estrela Figueiredo

Case Study 12.1. Inhaca Island within Maputaland centre of endemism

Annae Senkoro, Filomena Barbosa and Salomão Bandeira

Case Study 12.2. Uses of plant species from Inhaca Island

Filomena Barbosa, Annae Senkoro and Salomão Bandeira

Case Study 12.3. The avifauna of Maputo Bay

Carlos Bento

PART IIIFISHERIES OF MAPUTO BAY

Chapter 13. SHALLOW-WATER SHRIMP FISHERIES IN MAPUTO BAY

Rui Paula e Silva and Zainabo Masquine

Case Study 13.1. Influence of the precipitation and river runoff on the semi-industrial shrimp

catches in Maputo Bay

Carlos Bacaimane and Rui Paula e Silva

Case Study 13.2. Influence of estuarine flow rates on the artisanal shrimp catches in Maputo Bay

Sónia Nordez

Case Study 13.3. Distribution and abundance of the shrimp Fanneropenaeus indicus in Maputo Bay

António Pegado and Zainabo Masquine

Case Study 13.4. By-catch in the artisanal and semi-industrial shrimp trawl fisheries in Maputo Bay

Vanda Machava, Adriano Macia and Daniela de Abreu

207

215

223

229

239

255

259

265

275

277

285

287

289

291

XX T h e M a p u t o B a y E c o s y s t e m

Chapter 14. THE MAGUMBA FISHERY OF MAPUTO BAY

Paula Santana Afonso and Zainabo Masquine

Chapter 15. ARTISANAL FISHERIES IN MAPUTO BAY

Alice Inácio, Eunice Leong, Kélvin Samucidine, Zainabo Masquine and José Paula

Case Study 15.1. Biology and current status of the Otolithes ruber population in Maputo Bay

Alice Inácio

Case Study 15.2. Aspects of the reproductive biology of saddle grunt (Pomadasys maculatus) and

silver sillago (Sillago sihama) in Maputo Bay

Isabel Chaúca

Case Study 15.3. Socio-economic aspects of gastropod and bivalve harvest from seagrass beds –

comparison between urban (disturbed) and rural (undisturbed) areas

Elisa Inguane Vicente and Salomão Bandeira

Case Study 15.4. The sea urchin Tripneustes gratilla: insight to an important food resource at Inhaca

Island

Stela Fernando and Salomão Bandeira

Case Study 15.5. Recreational and sport fishing in Maputo Bay

Marcos Pereira and Rudy Van der Elst

PART IV

CROSS CUTTING ISSUES

Chapter 16. POLLUTION IN MAPUTO BAY

Maria Perpétua Scarlet and Salomão Bandeira

Case Study 16.1. Aerosols in Maputo Bay

António Queface

Case Study 16.2. Heavy metal contamination of penaeid shrimps from the artisanal and semi-

industrial fisheries in Maputo Bay

Daniela de Abreu, David Samussone and Maria Perpétua Scarlet

Chapter 17. POTENCIAL CLIMATE CHANGE IMPACTS ON MAPUTO BAY

Alberto Mavume, Izidine Pinto and Elídio Massuanganhe

Chapter 18. MANAGEMENT OF MAPUTO BAY

Sérgio Rosendo, Louis Celiers and Micas Mechisso

297

303

321

325

329

335

341

345

347

373

377

383

399

XXIT h e M a p u t o B a y E c o s y s t e m

Table of Contents

Chapter 19. MAPUTO BAY: THE WAY FORWARD

José Paula and Salomão Bandeira

419

T h e M a p u t o B a y E c o s y s t e m 399

Managementof Maputo Bay

18

Sérgio Rosendo, Louis Celliers and Micas Mechisso

Introduction Estuaries are complex and diverse systems that

present significant management challenges. This

complexity arises not only from a multiplicity of

resources and resource-use activities that occur

within their boundaries, but also because they are

affected by processes and activities occurring in

the broader catchment and adjacent marine area. It

is widely recognised that coastal zones in general

have unique characteristics that require special

management treatment. Estuarine systems, as par-

ticular components of the coastal zone, have

equally high management requirements. Some

countries recognise the specificity of estuaries and

require special management plans to be prepared

for these systems. However, Mozambique lacks a

legal instrument for the co-ordinated management

of estuaries. Nevertheless, it has made some steps

towards developing policies, legislation and insti-

tutions for the protection and management of

coastal zones.

Despite recognition of the need for developing

a more integrated approach to managing coastal

zones, the various sectors are still governed by a

plethora of laws addressing particular resources,

activities and sector-specific issues or problems.

Separate laws have evolved for land-use planning,

fisheries, aquaculture, minerals, energy, tourism and

recreation, waste disposal and pollution control,

conservation and site protection. These also define

respective regulatory institutions as well as their

functions. Consequently, responsibilities for manag-

ing the coast are also dispersed amongst a multiplic-

ity of actors and institutions. This chapter provides

an overview of the existing regulatory framework

and the resulting institutions that may to varying

degrees contribute to the management of Maputo

Bay. For the purposes of this chapter, management

is understood as deliberate efforts to direct or con-

trol actions and conditions. Management takes place

within a given regulatory framework that defines

access to and use of resources, and is undertaken by

various actors including government institutions,

the private sector and civil society. Although the

actions of individuals are important in terms of man-

agement outcomes, in this chapter we are interested

in collective actors such as institutions and organisa-

tions, their mandates and functions.

The next section of the chapter identifies and

describes the main policies and laws dealing with

400 T h e M a p u t o B a y E c o s y s t e m

IV . Cross Cutting Issues

environmental protection, spatial planning and fish-

eries. These three aspects were selected because of

their centrality to managing the Bay given their

linkages to key problems the system is facing such

as loss and degradation of coastal habitats, erosion,

inappropriate settlement and building and threats

to the sustainability of fishing activities. They are

not exhaustive of all applicable laws but rather serve

to exemplify the complexity of the legislative

framework and some of the key overlaps and omis-

sions. The subsequent section of this chapter out-

lines the key institutions involved in the

management of Maputo Bay, again with reference to

the three aspects cited earlier. The concluding sec-

tion presents the case for developing a strategic

framework for the integrated management of

Maputo Bay.

Overview of the policy and legal frameworkMaputo Bay is by no means uniform in social and

ecological terms. Natural habitats, levels of human

occupation, types and intensities of resource use

vary widely across the landscape. Consequently,

the types of environmental problems that affect

the Bay are diverse. Nevertheless, some of the

most common include the loss of coastal wetlands,

mangroves and other coastal habitats as a result of

a proliferation of badly planned or unplanned set-

tlements and infrastructure; pollution from various

local and remote sources including domestic and

industrial waste water, shipping, nitrate and pesti-

cide contamination from agriculture (see Chapter

16 – Pollution in Maputo Bay); coastal erosion (see

Case Study 3.1); and salt-water intrusion into

coastal aquifers and agricultural land (Langa, 2007;

Hoguane, 2007; UN-HABITAT, 2009). These

issues are addressed by various laws, including

laws specific to environmental protection, nature

conservation, land-use planning and water

resources management.

Environmental protection The legal foundations for environmental protection

are provided by the Constitution of the Republic, the

latest version of which was approved on 16 Novem-

ber 2004 [Item 1]. The Constitution does not make

specific reference to the coastal zone, but several of

its provisions lend support to laws and policies that

have a bearing on coastal zone management. Fore-

most amongst these is the entrenched right of the

population to a healthy and balanced environment

(Art. 90). Article 117 goes on to identify a number of

areas of policy that the State is to adopt in order to

protect the environment within a sustainable devel-

opment framework. These include preventing and

controlling pollution and erosion; integrating envi-

ronmental goals in sector policies and environmental

values in education programmes; guaranteeing the

rational use of natural resources; and promoting the

appropriate spatial planning of activities.

The 1997 Environment Law (Law 20/97) [Item

2] is the reference law for environmental protection

in Mozambique. Some of the most important provi-

sions directly relevant for managing coastal zones are

the prohibition to pollute, including the discharge of

pollutant substances to water bodies (Art. 9); provi-

sions for the creation of environmental protection

areas that may cover river and marine areas (Art.

13/2); prohibition to establish infrastructure that due

to their dimension, nature and location may impact

negative on the environment, particularly in coastal

zones and other ecologically fragile areas (Art. 14/2);

and requirements for environmental licensing,

including Environment Impact Assessment (EIA)

and auditing (Art. 16, 17 and 18).

A cross-cutting policy and accompanying law

that is particularly relevant for coastal management is

the 1995 Land Policy and Implementation Strategy

(Resolution 10/95) [Item 3] and the laws and regula-

tions that followed it, namely the 1997 Land Law

(Law19/97) [Item 4], and the 1998 Land Law Regu-

401T h e M a p u t o B a y E c o s y s t e m

18 . Management of Maputo Bay

lations (Decree 6/98) [Item 5] together with its tech-

nical annex (Ministerial Diploma 29-A/2000) [Item

6] and respective alterations (Decree 1/2003) [Item

7]. The Land Policy [Item 3] makes reference to the

need to promote the sustainable use and protection

of coastal zones (Section IV/7). It goes on to define

specific measures to protect the coastal zone. Article

8 declares that the first 100 meters from the mean

water mark inland along the coastline and the con-

tour of islands, bays and estuaries is a zone of partial

protection. Article 9 states that land use rights cannot

be acquired for areas falling within zones of partial

protection except through special licenses.

Two other policies and respective legislation that

have a bearing on coastal management are those

related to forests and wildlife and water resources.

The Forests and Wildlife Development Policy and

Strategy (Resolution 8/97) [Item 8] recognizes that

mangroves are under threat, particularly in Maputo

province, but it does not contain any specific meas-

ure for their protection. The Forests and Wildlife

Law (Law 10/99) [Item 9] itself also does not address

coastal zone matters directly, but it provides the legal

basis for the creation of protected areas, including

national parks and reserves to protect fragile ecosys-

tems such as wetlands, mangroves, dunes and corals

(Art. 10, 11 and 12).

Water resources are of vital importance for estua-

rine systems because of the effects that flows of

freshwater and sedimentation can have on their mor-

phology, productivity and pollution levels. The Water

Law (Law 16/91) [Item 10] contains several provi-

sions directly relevant for these systems. Among

these are that water resources should be used with-

out detriment to the minimum and ecological flow of

rivers, and the pledge to protect water quality (Art.

13), both of which play a vital in bio-morphological

processes. The Water Law also contains provisions

for international cooperation on transboundary river

basins, sharing of water resources and control of pol-

lution (Art. 14), and requirements for social, eco-

nomic and environmental impact assessment of

large-scale infrastructure project on rivers which

have potential downstream effects such as dams (Art.

7). The Water Law is supported by a Water Policy

(Resolution 7/95) [Item 11], which was revised and

updated in 2007 (Resolution 46/2007) [Item 12] and

a National Water Strategy [Item 13] aimed at driving

the implementation of the Policy. The new Water

Policy recognises the vital importance of water for

fisheries in terms of the water flow and water quality

in rivers and estuaries (Section 3.4.3) and the envi-

ronment in general with regards to supporting eco-

systems (Section 4).

In 2006, Mozambique passed legislation aimed

specifically at coastal zones, the Regulation for the

Prevention of Pollution and Protection of the Marine

and Coastal Environment (Decree 45/2006) [Item

14]. These regulations are one step towards giving

coastal zones a distinct legal statute by defining what

is meant by ‘coast’ and ‘coastal zone’ (see Box 1), and

established a number of provisions regarding pollu-

tion from land-based sources as well as from shipping

activities and rigs; and the protection of vulnerable

habitats such as coral reefs, wetlands, native coastal

vegetation and specific species, namely marine tur-

tles. The Regulations also reinforce the special pro-

tection status given to the coastal strip (100 meters

from the mean high-tide mark).

Regulations concerning pollution have added

relevance for Maputo Bay because of the Maputo

Port and the potential for operational and accidental

discharges of oil and other harmful substances from

ships. Land-based sources of pollution are also an

important issue in the Bay (see Chapter 16 – Pollu-

tion in Maputo Bay, for an overall view of pollution

issues in Maputo Bay). Rapid urbanization and indus-

trial development and insufficient treatment facili-

ties for domestic and industrial waste waters have

increased pollution levels (UNEP et al. 2009). More

402 T h e M a p u t o B a y E c o s y s t e m

IV . Cross Cutting Issues

distant sources of pollution may also affect the Bay

through its rivers. This includes not only pollution

occurring within Mozambique but also beyond its

borders since some of the rivers that discharge into

the Bay are transboundary. This is the case of the

Maputo, Incomati and Umbeluzi rivers.

The Regulation concerning the coastal and

marine environment is also important in terms of

protecting wetlands, which had not been covered

adequately in previous legislation and now brings

Mozambique closer in line with its international

commitments under the Ramsar Convention on Wet-

lands. It defines wetlands as areas of swamp, broads

and turf, or of water naturally or artificially formed,

stagnant or flowing, permanent or temporary, fresh,

brackish or salty, including areas of the sea with

depths at low tide not exceeding 6 meters that sus-

tain animal and plant life that require saturated soils

for their survival. This effectively includes large areas

of Maputo Bay. Other relevant provisions include

prohibitions on discharge of untreated wastewater to

wetlands and rivers flowing into wetlands, and any

activities that involve a substantial alteration of their

hydrological regime.

Fisheries Fisheries are a key area of policy and legislation rele-

vant to the management of Maputo Bay (see Part 3,

Chapters 13 to 15 for an overall view of fisheries in

Maputo Bay). Fishing and associated activities, such as

fish trading, provide livelihoods for a considerable

number of people, while also being an important source

of protein for the population and supplier of a large

number of restaurants that attract foreign tourists and

Mozambicans alike, particularly in Maputo city. Devel-

opment objectives for the fisheries sector were first out-

lined in the 1996 Fisheries Policy and Implementation

Strategy (Resolution 11/96) [Item 15], emphasizing the

contribution of fisheries to food security, employment,

poverty reduction and economic growth (Art. 3). These

objectives continue to feature in most policies dealing

with economic development, including the Poverty

Reduction Strategy Papers that in recent years have

guided the country’s efforts to reduce poverty levels

[Items 16, 17, 18].

The 1996 Fisheries Policy [Item 15] also estab-

lishes the basis for the management of fisheries

resources, particularly in terms of avoiding over-exploi-

tation. At the time the Fisheries Policy was drafted (mid

1990s), fisheries resources were recognised as being

over-exploited in several areas, amongst them Maputo

Bay (Art. 17.1/c). The management measures set out in

the Fisheries Policy include restrictions on fishing activ-

ities for resource conservation and socio-economic pur-

poses; promoting the involvement of local communities

in management; and introducing systems to control

fishing effort such as allocation of fishing rights through

quota systems (Art. 19).

According to the 2006 Regulation for the Preven-tion of Pollution and Protection of the Marine and Coastal Environment [Item 14], the coast refers to “the area of the national territory formed by the ter-restrial environment that is directly influenced by the sea, including the beach, dunes, and man-groves; and the marine environment located near land” (Art. 1/11). Coastal zones are “areas between

the inner edge, land or continental, of all coastal districts, including districts bordering Lake Niassa and Cahora Bassa, 12 nautical miles from the sea inside” (Art. 1/48). In other words, the coastal zone extends from the inner boundaries of districts bor-dering the ocean, Lake Niassa and Cahora Bassa dam to the outer limit of territorial waters (12 nauti-cal miles).

Box 1 How is the ‘coastal zone’ defined in Mozambique?

403T h e M a p u t o B a y E c o s y s t e m

18 . Management of Maputo Bay

Fishing activities in Mozambique are regulated by

the Fisheries Law of 1990 (Law 3/90) [Item 19], which

in the case of marine fisheries are expanded in the 2003

General Regulations on Marine Fisheries (Decree

43/2003) [Item 20]. The latter include provisions regard-

ing prohibited gear, licensing of fishing activities and

fisheries management measures and institutions. One

of the most significant features of these Regulations is

the establishment of a participatory system for fisheries

management (Art. 15) consisting of a nested set of insti-

tutions that include Community Fisheries Councils

(CCPs) at the local level, Co-Management Committees

(CCG) at the provincial and district levels, and a Com-

mission of Fisheries Administration (CAP) at the

national level.

Spatial planning Legislation in Mozambique applying to spatial plan-

ning can be largely divided into two types: environmen-

tal impact assessment requirements under the

Environment Law [Item 2] that apply to all activities

that are susceptible of causing damage to the environ-

ment; and land use or territorial planning laws that have

both a regulatory and development function [Items 21,

22].

As a regulatory mechanism, spatial planning laws

and instruments are important to protect certain envi-

ronmentally sensitive areas; and as a development

mechanism they aim to promote a more rational arrange-

ment of activities and to reconcile competing social,

economic and environmental goals. While appearing to

Any activity which may affect the environment requires authorization or a licence issued by MICOA. This license is based on the evaluation of the potential impact of the planned activity. The procedures for environmental licensing are specified in the EIA Regu-lations (Decree45/2004) [Item 23]. Annexes I, II and III of the EIA Regulation divide potential activities into three categories based on their likely impact on the environment. Proponents of a listed activity must obligatorily apply for an environmental license. Cate-gory A is subject to a full EIA; B to a Simplified Environ-mental Assessment; and C is to norms of good environmental management. Any other activity not listed, but potentially causing significant negative impact on the environment, is subject to a pre-evalu-ation by MICOA which may: reject its implementation; categorize it and consequently determine the type of environmental evaluation to be undertaken; or exempt it from environmental evaluation. Despite this comprehensive legislation, development has taken place legally in ecologically fragile areas of the coast. Both the 1997 Land Law [Item 4] and the 2006 Regula-tion for the Prevention of Pollution and Protection of the Marine and Coastal Environment [Item 14] declare the first 100 meters from the mean high water mark as

a zone of partial protection. The Land Law states that land use rights cannot be acquired for this area, which helps to prevent most types of development. Generally, a development cannot go ahead without the proponent having land rights to the area in question. However, both legal instruments include provisions for a special license for certain activities (Art. 9 and Art. 66 of each instrument respectively). Various special licenses for eco-tourism facilities directly on the coast or on small-islands have been granted under this provision (MICOA, 2007). The 2006 Regulation concerning the marine and coastal environment [Item 14] states that certain types of infrastructure can be established in zones of partial protection provided that the environmental quality standards in force are observed. Such standards are interpreted to mean EIA regulations [Item 23]. Pro-posed developments located in areas and ecosys-tems with special protection status fall under Category A and trigger an EIA. Many of the ecosys-tems and areas listed are coastal, and include coral reefs, mangroves, small islands and coastal dunes. This means that developments located on sensitive coastal and marine areas may be authorised pro-vided that the EIA is favourable.

Box 2 Regulating development along the coast

404 T h e M a p u t o B a y E c o s y s t e m

IV . Cross Cutting Issues

be comprehensive, Environment Law [Item 2] in

Mozambique has some limitations in terms of protect-

ing the coastal environment from inappropriate devel-

opment. This is aggravated by the weak capacity of

government authorities to enforce the legislation, which

has enabled the proliferation of illegal building on the

coastal strip (MICOA, 2007). These combined prob-

lems are well visible in Maputo Bay where construction

is encroaching on the mangrove at Costa do Sol, in

Maputo City. Much of this construction is legal, which

means that there are gaps and inconsistencies in the law

that fail to protect vulnerable coastal habitats (see Box

2).

In 2007, Mozambique published a Land Use or

Territorial Planning Policy (Decree 11/2007) [Item 24]

which explicitly aimed to improve the management of

natural resources through better coordination of sector

policies and planning at various scales, from national to

local. The policy places significant emphasis on

improving the institutional framework for land use

planning at all levels of decision-making. It states that

implementation will be based on existing institutions,

but highlights the need to build their capacity and

define simple and clear rules of articulation between

them. The Land Use Policy is accompanied by a Land

Use Planning Law (Law 19/2007) [Item 18] that

defines a land-use planning system comprised of four

different levels of intervention, namely national, pro-

vincial, district and local authority or municipal (Art

8/1). The law also states that planning at the different

levels should be vertically coordinated and aligned,

with lower levels having to make their plans and

actions compliant with those of higher levels (Art 8/3).

The respective roles of each of the planning levels, as

well as the land-use instruments used at each level, as

defined in the Land Use Law and respective regula-

tions [Items 21, 22], are outlined in Table 1.

Although the various instruments need to be ver-

tically aligned, the preparation and approval of a plan

at a lower level does not depend on the existence of a

plan at a higher level (Land Use Planning Law Regu-

lations, Art. 7/2, Art. 12/3). For example, a District

Land Use Plan does not depend on there being a Pro-

vincial Territorial Development Plan in place. Moreo-

ver, only the district and municipal level plans are

compulsory (Art. 7/2) and their preparation must be

initiated within two years of the publication of the pre-

viously mentioned regulations (Art. 8/2).

The land use planning legislation goes some way

to creating a favourable legal environment for a more

sustainable and integrated management of the coastal

zone. By making land use plans compulsory for dis-

tricts and municipalities it contributes to addressing

some of the problems that affect the coastal zone, par-

ticularly disorderly urbanisation and encroachment on

fragile areas and ecosystems. It also promotes a greater

integration of plans at different levels with the require-

ment that lower-level plans be consistent with higher

level plans. Another important feature of the Land

Use Planning legislation is the participation of stake-

holders (Art. 22 of the Land Use Law [Item 21] and

Art. 9 of the Land Use Law Regulations [Item 22]).

Provisions for participation have the potential to ena-

ble affected parties to express their views on the allo-

cation of land and resources for different purposes,

potentially leading to more effective and equitable

plans.

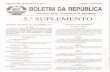

Figure 1 is a non-exhaustive representation of

legislation regulating the use of resources in Maputo

Bay. The first column represents key laws governing

coastal areas; the middle column are key provisions

relevant to management of these areas; and the third

column shows how these provisions are linked to

other laws and regulations. These linkages can rein-

force and complement some provisions but also cre-

ate redundant overlaps. For example, the land use

planning instruments provided for under the Land

Use Planning Law are reinforced by the Law of Local

Government which transfers responsibilities to Dis-

tricts for land use planning. Another example are pro-

405T h e M a p u t o B a y E c o s y s t e m

18 . Management of Maputo Bay

Figure 1. Legal framework applying to the Management of Maputo Bay.

IEA requirements

Protected areas

Pollution of water bodies

Public participation

Water use

Water quality and quantity

Transboundary cooperation

Protection zones

100m protection zone

Land rights

Community participation

Land use planning instruments

Resource use regulation

Protection of fragile areas incl. coastal areas

Participatory management

Licensing & regulation

Protection measures

Protected areas

Participatory management

Licensing & regulation

Key provisionsrelevant to management Laws

Linkages to otherlaws and regulations

Environmental Law

Forests and Wildlife Law

Land Law

Water Law

Land Use Planning Law

Fisheries Law

General IEA Regulations

IEA Regulations for Mining

Licensing Regime for Private Construction

Law of Local Government

Law of Local Authorities

Forests and Wildlife Law

Environmental Law

Water Law

Land Law

Land Law Regulations

Land Use Planning Law Regulations

General Regulations on Aquaculture

General Regulations on Marine Fisheries

Sports & Recreational Fisheries Regulations

Regulations for Prevention of Pollutionand Protection of the Coastaland Marine Environment

Law of Tourism

visions for protected and conservation areas that are

simultaneously covered under Environment Law,

Forests and Wildlife Law, Tourism Law, Fisheries

Law and Local Government Law (or Law of the

Local Organs of the State). In this case, overlap leads

to some degree of confusion over which legislation

governs the establishment of these areas (Chircop et

al., 2010).

Institutional landscape for managementof Maputo BayMICOA has overall responsibility for environmental

protection and management in Mozambique, specifi-

cally in terms of monitoring compliance with and

enforcing environmental legislation, and promoting

the integration of environmental concerns in national

and sub-national policies and plans. Its full objectives

406 T h e M a p u t o B a y E c o s y s t e m

IV . Cross Cutting Issues

and functions are defined in Presidential Decree 5/95

[Item 25] and its most up-to-date structure presented

in Ministerial Diploma 265/2009 [Item 26]. MICOA’s

structure includes various units dedicated specifically

to coastal and marine matters, namely a Department

for Coastal Management within its National Directo-

rate for Environmental Management, and two subor-

dinate research institutions, the Centre for the

Sustainable Development of Coastal Zones (CDS-

ZC) created in 2003 (Decree 5/2003) [Item 27] and the

Centre for Research on the Marine and Coastal Envi-

ronment (CEPAM), established in 2007 (Decree

16/2007) [Item 28].

MICOA operates on the ground through Provin-

cial Directorates for the Coordination of Environmen-

tal Action (DPCAs). DPCAs are organised into various

departments responsible for different activity areas,

including Environmental Management, Environmen-

tal Education and Gender, Land-Use Planning and

Environmental Inspection (Ministerial Diploma

91/99) [Item 29]. They have the important role of pro-

viding technical assistance to local government (Dis-

tricts and Municipalities) on all matters related to

environment, particularly in terms of preparing land-

Role Specific instruments General instruments

National

Defines the general rules of land use planning;

Sets the planning norms and directives for provincial, district and municipal level;

Harmonises land use strategies of the various sectors.

National Territorial Development Plan (Plano Nacional de Desenvolvimento

Territorial)

Special Land Use Plans (Planos Especiais de Ordenamento do Território)

Qualification of Soils 1

Classification of Soils 2National Land Registry

Environmental, Social and Economic Assessments

Zoning

Provincial

Defines provincial land use strategies, which must be integrate with national development

strategies; Establishes planning directives for district

and municipal level.

Provincial Territorial Development Plans (Planos Provinciais de Desenvolvimento

Territorial)

District

Prepares land use plans and implementation projects that must integrate with national

policies and be in accordance with national and provincial directives.

District Land Use Plans (PlanosDistritais de Uso da Terra)

Municipal (Local

Authority)

Establishes development programs, plans and projects and the urban land use regime

according to existing law.

Town Master Plans (Planos de Estrutura Urbana)

Urbanisation Plans (Planos Gerais e Parciais de Urbanização)

Detailed Plans (Planos de Pormenor)

Table 1. The land use planning system as defined in the Land Use Planning Law.

1 In terms of their biophysical characteristics and use 2 In terms of the applicable political/administrative regime, namely urban or rural soils

407T h e M a p u t o B a y E c o s y s t e m

18 . Management of Maputo Bay

use plans and integrating environmental concerns in

activity plans and budgets. Applications for environ-

mental licenses, which may lead to an EIA process, are

also processed by MICOA, either at the provincial or

national level according to the type and scale of the

activity proposed (DPIC et al. 2009). Maputo Bay is

under the responsibility of the DPCA for Maputo

Province.

Beyond environmental issues in general and the

role played by MICOA in monitoring and enforcing

environmental legislation and providing technical

assistance to, and building the capacity of, local gov-

ernments, there are a number of other institutions

involved in managing particular resources and areas

within Maputo Bay. This is the case of fisheries, water

resources, land and protected areas which, as noted in

the earlier section, are subject to specific legislation.

Fisheries and fishing activities at the national level

are governed by the Ministry of Fisheries (MoF), the

functions and competencies of which are defined in

Presidential Decree 6/2000 [Item 30]. On the ground,

the MoF operates through its provincial directorates

and Services for Economic Activities at the District

Level. The MoF also includes various institutions

dealing with specific issues such as fisheries research,

extension, aquaculture, fisheries development and law

enforcement, as outlined in its organisational structure

defined in Resolution 38/2010 [Item 31]. Fishing is

regulated by a system of permits defined in the fisher-

ies legislation [Items 19, 20] and issued by Provincial

Directorates of Fisheries or District Services for Eco-

nomic Activities. Fishing vessels must also be licensed

by INAMAR, the National Navy Institute. INAMAR

is represented locally by Maritime Administrations

(ADMAR) and Maritime Delegations [Item 32].

In the case of Maputo Bay, only semi-industrial

and artisanal fishing activities are allowed. Shallow

water prawns are one of the main resources, but finfish

and invertebrates are also important. In the Bay there

are over 30 artisanal fishing centres, varying in size, but

all are associated with one of the main fishing commu-

nities of Inhaca, Catembe, Matola, Costa de Sol and

Muntanhame (EU SADC MCS Programme 2004).

During the wet season (January to March) the Minis-

try for Fisheries applies a closed fishing season for

prawns through ministerial decree. In 2012, this period

was from 1 January to 28 February (Ministerial

Diploma 273/2011 [Item 33]). The monitoring and

enforcement of fisheries regulations is undertaken by

the Ministry of Fisheries through its provincial direc-

tions and District Services for Economic Activities.

Other institutions may also be involved, for example

the Maritime Police and the Navy.

Mozambique has passed legislation for the partici-

patory management of fisheries resources, which

includes provisions for the establishment of participa-

tory institutions at national, provincial and district and

local levels. At the local level, these institutions are

called Community Fishing Councils (CCPs). The

CCPs are organisations set up at the community level

to enable fisheries co-management, namely by con-

tributing towards the enforcement of existing fishing

regulations and other management measures and solv-

ing conflicts arising from fishing activities. They are

responsible for an area of coastline between two well-

known reference points (for example, between points

X and Y and 3 nautical miles into sea). The full range

of objective of CCPs is listed in Box 3.

In Maputo Bay there is at least one fully legal-

ised CCP in Costa do Sol (recognised by a Dispatch

of the Ministry of Fisheries on 23 May 2008 [Item

35]). This CCP is responsible for an area along the

coast (between two points: Rua 10 and Banderene)

up to three miles into the sea. However, Costa do Sol

is only one amongst the various fishing centres in

Maputo Bay. Several of these fishing centres share

the same fishing grounds because Maputo Bay is a

relatively confined area (see Chapter 15 – Artisanal

Fisheries of Maputo Bay, for location of fishing cen-

tres in Maputo Bay). This is a challenge to establish-

408 T h e M a p u t o B a y E c o s y s t e m

IV . Cross Cutting Issues

ing additional CCPs as many of the fishing grounds

used by the various communities in the Bay are the

same, thus almost certainly creating overlaps in terms

of users and jurisdiction over their management.

Water resources at the national level are man-

aged by the Ministry for Public Works and Housing

through its National Water Directorate. The National

Water Directorate in turn has established a number

of regional water bodies throughout the country

called Regional Water Administrations (ARA), each

responsible for the management of key river basins.

The rivers that drain into Maputo Bay are managed

by ARA Sul, the regional water body for southern

Mozambique. Other institutions involved in water

resources management include the Ministry for Agri-

culture, particularly through its promoting of irriga-

tion systems. MICOA also plays a role in terms of

monitoring and enforcing environmental legislation

regarding pollution and protection of water bodies.

The importance of water resources for various uses

and users has prompted the establishment of a

National Water Council bringing together various

ministries in order to coordinate policy and action on

water resources.

District Governments and Municipalities are

important actors in the management of Maputo Bay,

particularly in terms of spatial planning. They have

powers to make decisions about the use of land and

to set aside areas for environmental protection. Their

mandates are outlined in the Law of Local Govern-

ment (Law 8/2004) [Item 36] and Law of Local

Authorities (Law 2/97) [Item 37] respectively. Dis-

trict Governments represent the nationally elected

government and are one of the administrative divi-

sions of Mozambique. Administratively, Mozam-

bique is divided into Provinces, Districts,

Administrative Posts and Localities. Municipalities

are also administrative divisions, but governed inde-

pendently by locally elected structures (Municipal

Councils). Municipalities were created in cities with

conditions to support a large share of their adminis-

trative and service provision costs through revenue

collected from taxes. They enjoy a larger degree of

financial and decision-making autonomy.

Maputo Bay encompasses the Districts of Matu-

tuíne and Marracuene and the Municipalities of

Maputo and Matola. Inhaca Island is one of the

Urban Districts of Maputo Municipality. The Land

The main objective of CCPs is to contribute towards the preservation of the coastal and marine environ-ment within its geographic area of coverage. Their tasks include: • Encourage and recommend licensing of fishing activities; • Alert the authorities about any changes in the marine environment or resources;• Carry out law and licensing enforcement activities delegated to them;• Collaborate in the fight against marine and coastal pollution; • Participate in the implementation of fishing restric-tion measures;

• Mediate any relevant conflicts between different types of fishers;• Encourage the use of adequate signalling means for fishing gear; • Promote awareness about the need to protect the marine environment; • Accompany and provide support for fisheries exten-sion activities;• Participate in data collection about fisheries activi-ties and training activities.

Source: Model Statute for Community Fishing Councils [Item 34]

Box 3 Community Fishing Councils

409T h e M a p u t o B a y E c o s y s t e m

18 . Management of Maputo Bay

Use Planning Law [Item 21] requires Districts and

Municipalities to have planning instruments in place

to guide their land allocation decisions and ensure

they comply with environmental regulations and

other laws promoting the sustainable use and conser-

vation of resources. Maputo City, for example, has an

Urban Structure Plan that provides the framework

for spatial planning of the city, including the identifi-

cation of areas for urban expansion and environmen-

tal protection (CMM, 2008). Land-use planning

instruments can also be important in terms of

addressing cross-cutting environmental issues such

as climate change. The Maputo Municipal Council,

for example, has been making efforts to assess the

effects of climate change on the city and incorporate

climate change considerations in planning (UN-

HABITAT, 2009).

Local communities play an equal important role

in how land is used around the Bay. Land legislation

grants rights to local communities over land they

have traditionally occupied [Items 4, 5]. They can

enter into negotiations with outside investors for the

use of community land for economic activities.

Demand for land is high, particularly in seafront

areas for the establishment of tourism-related busi-

nesses. While basic awareness of rights to land exist

amongst local communities, various studies suggest

that local people still lack full understanding of what

these mean when confronted with the state and pow-

erful outsiders that seek to occupy their land.

Although the legislation defines clear procedures for

negotiation between outsiders and local communi-

ties [Item 5], the bargaining power of the latter is

often weak and the consultation and negotiation

processes do not always involve all community mem-

bers, meaning that only a few people benefit (de Wit

and Norfolk, 2010; Norfolk and Tanner 2007: Hanlon,

2004).

Maputo Bay also includes a number of protected

areas, including the Inhaca Island and Portuguese

Island Reserves and the northern part of the Maputo

Special Reserve. Inhaca Island and the Maputo Spe-

cial Reserve have both marine and terrestrial compo-

nents. At Inhaca Island, the marine part protects

coral reefs at Barreira Vermelha and Ponta Torres

sites, while the Maputo Special Reserve protects

marine habitats adjacent to the coastline. These two

protected areas now link with the recently created

Ponta do Ouro Marine Partial Reserve (Decree

42/2009) [Item 38] extending from the most northern

point of Inhaca Island to Ponta do Ouro, bordering

South Africa (DNAC, 2010). These protected areas

form part of the much wider transfrontier conserva-

tion plans involving Mozambique, South Africa and

Swaziland (Lumbombo Transfrontier Conservation

Area) and have management plans (DNAC, 2009;

2010).

Conclusion: towards an integrated management of Maputo BayWhat is the answer to improving the management of

the Bay? There is no simple answer or recipe. A com-

bination of various actions may be needed. Some

options are provided below. It is open to question

whether some of these are feasible, but they are cer-

tainly possibilities.

A first step towards more effective management

of Maputo Bay would be to improve the implemen-

tation of existing legislation. The land-use planning

laws in combination with environmental and other

laws provide a good basis for addressing some of the

problems that affect the Bay. For this to happen, it is

also necessary to strengthen the capacity of the insti-

tutions involved in the management of the Bay in

terms of qualified human resources, technical exper-

tise and information and knowledge. A great deal of

scientific information already exists about Maputo

Bay generated by different donor and NGO-led

projects and the University Eduardo Mondlane. A

good example is the collection featured in this vol-

410 T h e M a p u t o B a y E c o s y s t e m

IV . Cross Cutting Issues

ume. However, existing information is not always

used to inform decisions, either because it is not eas-

ily accessible to those making decisions or is in a for-

mat that is of limited use for decision-makers.

Obviously, even when relevant information is availa-

ble, decision-making processes need to be oriented

towards using such information. In many cases, short-

term economic objectives and political interests are

an obstacle to making decisions based on the best

available scientific information. Better linkages

between researchers and decision-makers are also

needed to ensure that both existing information and

efforts to expand it address management needs.

Another requirement is to recognise Maputo Bay

as a distinct management area with special manage-

ment needs. Linked to this is the need for better

coordination between the various institutions and

sector plans and strategies, and their alignment

within a common framework and goal. One way of

doing this is by developing a management plan for

Maputo Bay. Some countries have made manage-

ment plans for estuaries compulsory. This is the case

of South Africa as part of the Integrated Coastal

Management (ICM) Act (Celliers et al. 2009). A man-

agement plan would provide an holistic framework

to manage the multiple factors that impact on the

Bay by providing a vehicle for inter-institutional

cooperation, promote change where needed, and

identify appropriate solutions to existing and future

problems and opportunities. It would not necessarily

impose new duties on institutions or alter their man-

dates. Rather it would utilise what there is already,

with existing agencies and organisations working

towards a shared vision.

Yet another option would be to create a Commis-

sion or similar type of collaborative management

institution responsible for the overall management of

Maputo Bay. A Commission would also provide the

leadership often required to implement any manage-

ment plan eventually prepared. Yet the creation of a

new institution to address old problems also needs to

be carefully considered, as it requires funding and

staff to function effectively. A first step towards

establishing a body of this kind would be to gain an

understanding of who are the Bay’s stakeholders and

describe their interests through a stakeholder analy-

sis, with a view to define its membership. A stake-

holder analysis of Maputo Bay would involve

identifying those who determine the decisions

affecting the Bay and those who are affected by such

decisions, either positively or negatively. It would

also identify actual and potential conflicts and trade-

offs. Conflicts are situations of competition and disa-

greement between two or more stakeholders over

the use of resources, including territory; while trade-

offs refer to the process of balancing conflicting inter-

ests and objectives (Brown et al. 2001; Grimble,

1998).

A third option would be a policy and associated

legislation for Integrated Coastal Management

(ICM). Box 4 shows some of the key principles of

ICM.

Mozambique has taken initial steps towards

ICM. This included hosting international workshops

(UNESCO, 2000), national planning workshops

(Lindén et al., 1996), and draft strategies at various

government levels (MICOA, 1998; UNEP/FAO/PAP,

1998). It has also created the CDS-ZC (2003), a spe-

cific agency of MICOA to lead ICM processes at

various levels. An ad hoc institution, the Technical

Inter-Institutional Committee for ICM (CTIGIZC)

was also created under the National Council for Sus-

tainable Development (CONDES), a body made up

of all ministries for the coordination of sector policies

in pursuit of sustainable development [Item 39]. In

2006, a draft version of a Strategy for the Integrated

Management of the Mozambique Coastal Zone

(2007-2017) was released, but it was not subsequently

finalised and approved by the Council of Ministers.

More recently, the Government Programme for 2010-

411T h e M a p u t o B a y E c o s y s t e m

18 . Management of Maputo Bay

2014 [Item 40] includes reference to the approval of

a policy for the sustainable development of coastal

zones (Paragraph 173/14).

At the international level, Mozambique has dem-

onstrated continued commitment to implementing

ICM. The latest of these demonstrations was in 2010,

as party to the Nairobi Convention for the Protection,

Management and Development of the Marine and

Coastal Environment of the WIO. All parties agreed

to strengthen ICM, including the development of a

protocol to lend support to its further application

across the region (Decision CP 6/3, UNEP 2010).

Mozambique is also a party to the Ramsar Conven-

tion on Wetlands. Clearly, both nationally and inter-

nationally Mozambique recognises the need for

specific policies, legislation and institutions to pro-

mote the protection and sustainable development of

coastal zones. However, to date no policy for the sus-

tainable management of the coastal zone has yet

been adopted, and institutions such as the CTIGIZC

have for the time being appeared to lost momentum,

which is demonstrated by it not being officially cre-

ated as part of CONDES.

An ICM policy could help to enshrine key princi-

ples for improved management of coastal zones,

including estuarine systems which include coordinat-

ing across different sectors, base planning on sound

knowledge, adopting a long-term perspective, pro-

actively involving stakeholders, and taking into con-

sideration both the terrestrial and marine components

of the coastal zone. However, the key would still be

implementation, which depends largely on factors

already enumerated such as adequate technical

capacity and strong political will. Which of the options

above are feasible and implementable in Maputo Bay

is open to debate. However, one thing is certain,

Maputo Bay needs to be managed as a system and

not in a fragmented manner.

ICM should incorporate a dual “bottom-up” and “top-down” approach. This seeks to ensure that the inter-ests of all stakeholders are taken into consideration through a local consultation and participation proc-ess, whilst at the same time creating a legal and regu-latory environment for an effective implementation of the ICM process. Integration in ICM has a number of dimensions:

• Vertical: integration among institutions and adminis-trative levels within the same sector; • Horizontal: integration among various sectors at the same administrative level; • Systemic: the need to ensure that all important inter-actions and issues are taken into consideration;• Functional: interventions by management bodies which must be harmonised with the coastal area man-

agement objectives and strategies; • Spatial: integration between the land and marine components of the coastal zone; • Policy: coastal area management policies, strategies and plans which need to be incorporated into broader-scale (including national) development policies, strat-egies and plans; • Science-management: integration among different scientific disciplines and the transfer of science for use by end-users and decision-makers; • Planning: plans at various spatial scales should not have conflicting objectives, strategies or planning proposals; and • Temporal: coordination among short, medium and long-term plans and programmes.

Adapted from: Ramsar Convention Secretariat (2007)

Box 4 Principles and dimensions of integration in ICM

412 T h e M a p u t o B a y E c o s y s t e m

IV . Cross Cutting Issues

Brown, K., Tompkins, E.L., Adger, W.N., 2001. Trade

off analysis for participatory coastal zone manage-

ment. Overseas Development Group, UEA, 109

pp.

Celliers, L., Breetzke, T., Moore, L., Malan, D., 2009.

A user-friendly guide to South Africa’s integrated

coastal management act. The Department of

Environmental Affairs and SSI Engineers and

Environmental Consultants, Cape Town, South

Africa, 100 pp.

Chircop, A., Francis, J., van Der Elst, R., Pacule, H.,

Guerreiro, J., Grilo, C., Carneiro, G., 2010. Gov-

ernance of Marine Protected Areas in East Africa:

A Comparative Study of Mozambique, South

Africa, and Tanzania. Ocean Development & Inter-

national Law 41, 1–33.

CMM, 2008. Plano de Estrutura da Cidade de

Maputo. Maputo, Conselho Municipal de

Maputo (CMM).

de Wit, P., Norfolk, S., 2010. Recognizing rights to

natural resources in Mozambique. Rights and

Resources Initiative, Washington DC, 40 pp.

Available online at: http://www.rightsan-

dresources.org/documents/files/doc_1467.pdf

(accessed at 20 April 2012).

DNAC, 2009. Ponta do Ouro partial Marine Reserve

Management Plan, 72 pp. Available online at:

http://www.aquamarinebay.com/docs/MPA_

ManPlan_English.pdf (accessed at 20 April 2012).

DNAC, 2010. Maputo Special Reserve Management

Plan, 1st Edition, 119 pp. Available online at:

http://www.opwall.com/Library/Opwall%20

library%20pdfs/Reports/South%20Africa/

M o z a m b i q u e / M a p u t o % 2 0 S p e c i a l % 2 0

Reserve%20Management%20Plan%20-%20

First%20Edition.pdf (accessed at 20 April 2012).

DPIC, MICOA, GERENA, 2009. O quadro legal

para o licenciamento ambiental em Moçambique.

Direcção Provincial de Industria e Comercio da

Província de Sofala, Ministério para a Coorde-

nação da Acção Ambiental, Acção Ambiental do

Programa GERENA, 58 pp.

EU SADC MCS Programme, 2004. Bay of Maputo

coastal surveillance operations in Mozambique:

Working Paper No. 25, July 2004. EU SADC

Monitoring Control and Surveillance of Fisheries

Activities Programme.

Grimble, R., 1998. Stakeholder methodologies in

natural resource management. Socioeconomic

Methodologies. Best Practice Guidelines.

Chatham, UK: Natural Resources Institute.

Hanlon, J., 2004. Renewed land debate and the ‘cargo

cult’ in Mozambique. Journal of Southern African

Studies 30, 603-625.

Hoguane, A.M., 2007. Perfil diagnóstico da zona

costeira de Moçambique. Revista de Gestão Costeira

Integrada 7, 69-82.

Langa, J.V.Q., 2007. Problemas na zona costeira de

Moçambique com ênfase para a costa de Maputo.

Revista de Gestão Costeira Integrada 7, 33-44.

Lindén, O., Lundin, C.G., (Eds.), 1997. Proceedings

of the National Workshop on Integrated Coastal

Zone Management in Mozambique. Inhaca

Island and Maputo, Mozambique, May 5-10,

1996. World Bank, SIDA/SAREC, 148 pp.

MICOA, 1998. Estratégia de desenvolvimento da

zona costeira do Distrito de Manjacaze. Adminis-

tração do Distrito de Manjacaze/MICOA,

Chidenguele, 32 pp.

MICOA, 2007. Relatório nacional sobre o ambiente

marinho e costeiro. Ministério para a Coorde-

nação da Acção Ambiental, Direcção Nacional de

Gestão Ambiental, Maputo, 66 pp.

Norfolk, S., Tanner, C., 2007. Improving tenure rights

for the rural poor: Mozambique country case-

study. FAO, Rome. Available online at: ftp://ftp.

Bibliography

413T h e M a p u t o B a y E c o s y s t e m

18 . Management of Maputo Bay

fao.org/docrep/fao/010/k0786e/k0786e00.pdf

(accessed at 20 Abril 2012).

Ramsar Convention Secretariat, 2007. Coastal man-

agement: wetland issues in Integrated Coastal

Zone Management. Ramsar handbooks for the

wise use of wetlands, 10, 3rd edition. Ramsar

Convention Secretariat, Gland, Switzerland.

UNEP, 2010. Decision CP 6/3: strengthening inte-

grated coastal zone management in the Western

Indian Ocean Region. In: The Decisions of the

Sixth Conference of the Contracting Parties

(COP) to the Convention for the Protection,

Management and Development of the Marine

and Coastal Environment of the Eastern African

Region (Nairobi Convention), 1 April 2010, 6 pp.

UNEP/FAO/PAP, 1998. Xai-Xai District Coastal Area

Management Strategy. East African Regional

Seas Technical Reports Series No. 2. Split,

Croatia, 84 pp.

UNEP/Nairobi Convention Secretariat, CSIR,

WIOMSA, 2009. Regional synthesis report on

the status of pollution in the Western Indian

Ocean Region. UNEP/Nairobi Convention Sec-

retariat, CSIR and WIOMSA, Nairobi, Kenya, 91

pp.

UN-HABITAT, 2009. Climate change impacts in

urban areas of Mozambique a Pilot Initiative in

Maputo City: A preliminary assessment and pro-

posed implementation strategy report. United

Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-

HABITAT), Nairobi, Kenya, 46 pp.

UNESCO, 2000. Pan-African Conference on Sustaina-

ble Integrated Coastal Management (PACSICOM),

Maputo, Mozambique, 18-24 July 1998. Proceed-

ings of Workshops, 317 pp. Available online at:

h t t p : / / u n e s d o c . u n e s c o . o r g /

images/0012/001211/121166e.pdf (accessed at 20

Abril 2012).

List of Laws, Policies and Plans

[1] Constituição da República de Moçambique, de

16 de Novembro de 2004. Constitution of the

Republic of Mozambique, of 16 November

2004. Available online at http://www.portaldog-

overno.gov.mz/Legisla/constituicao_republica/

(accessed 18 April 2012).

[2] Lei nº 20/97 de 1 de Outubro. Aprova a Lei do

Ambiente. Law 20/97 of 1 October. [Approves

the Environment Law]. Boletim da República,

Série I, 40, 7 de Outubro de 1997, pp. 200 (19)

– 200 (24). Available online at: http://www.

legisambiente.gov.mz/index.php?option=com_

docman&task=doc_view&gid=27 (accessed 18

April 2012).

[3] Resolução nº 10/95, de 17 de Outubro. Política

Nacional de Terras e as respectivas Estratégias

de Implementação. [Land Policy and Imple-

mentation Strategy, Resolution nº 10/95 of 17

October]. Boletim da República, Série I, 9, 28 de

Fevereiro de 1996, pp. 52 (1) – 52 (6). Available

online at: http://www.legisambiente.gov.mz/

index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_

view&gid=77, (accessed 18 April 2012).

[4] Lei nº 19/97, de 1 de Outubro. Aprova a Lei de

Terras. [Land Law, Law nº 19/97 of 1 October].

Boletim da República, Série I, 40, 7 de Outubro

de 1997, pp. 200 (15) – 200 (19). Available online

at: http://www.legisambiente.gov.mz/index.

php?option=com_docman&task=doc_

view&gid=49 (accessed 18 April 2012).

[5] Decreto nº 66/98, de 8 de Dezembro. Aprova o

Regulamento da Lei de Terras. [Land Law

Regulations, Decree nº 66/98 of 8 December.

414 T h e M a p u t o B a y E c o s y s t e m

IV . Cross Cutting Issues

Boletim da República, Série I, 48, 8 de Dezem-

bro de 1998, pp. 225 (33) – 225 (40). Available

online at: http://www.legisambiente.gov.mz/

index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_

view&gid=50 (accessed 18 April 2012).

[6] Diploma Ministerial nº 29-A/2000, de 17 de

Março. Aprova o Anexo Técnico ao Regulamento

da Lei de Terras [Technical Annex to the Land

Law Regulations, Ministerial Diploma nº

29-A/2000, of 17 de March ]. Boletim da

República, Série I, 11, 17 de Março de 2000, pp.

50 (30) – 50 (36). Available online at: http://www.

legisambiente.gov.mz/index.php?option=com_

docman&task=doc_view&gid=51 (accessed 18

April 2012).

[7] Decreto nº 1/2003, de 18 de Fevereiro. Altera os

artigos 20 e 39 do Regulamento da Lei de

Terras, aprovado pelo Decreto n.º 66 de 1998,

de 8 de Dezembro. [Changes to the Land Law

Regulations, Decree nº 1/2003, of 18 de

February. Boletim da República, Série I, 7, 18

de Fevereiro de 2003, pp. 40 (4) – 50 (36).

Available online at: http://www.legisambiente.

gov.mz/index.php?option=com_

docman&task=doc_view&gid=52 (accessed 18

April 2012).

[8] Resolução nº 8/97, de 1 de Abril. Aprova a

Política e Estratégica de Desenvolvimento de

Florestas e Fauna Bravia. [Forests and Wildlife

Development Policy and Strategy, Resolution nº

/97 of 1 de April]. Boletim da República, Série I,

14, 1 de Abril de 1997, pp. 51 (1) – 51 (9).

Available online at: http://www.legisambiente.

gov.mz/index.php?option=com_

docman&task=doc_view&gid=78 (accessed 18

April 2012).

[9] Lei n° 10/99, de 7 de Julho. Lei de Florestas e

Fauna Bravia [Forests and Wildlife Law, Law n°

10/99 of 7 July]. Boletim da República, Série I,

27, 12 de Julho de 1999, pp. 126 (31) – 126 (39).

Available online at: http://www.legisambiente.

gov.mz/index.php?option=com_

docman&task=doc_view&gid=37 (accessed 18

April 2012).

[10] Lei n.º 16/91, de 3 de Agosto de 1991. Aprova a

Lei de Águas [Water Law, Law n.º 16/91 of 3

August]. Boletim da República, Série I, 31, 3 de

Agosto de 1991, pp. 214 (11) – 214 (22). Available

online at: http://www.legisambiente.gov.mz/

index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_

view&gid=104 (accessed 18 April 2012).

[11] Resolução nº 7/95 de 23 de Agosto de 1995.

Aprova a Política de Águas [Water Policy,

Resolution nº 7/95 of 23 August 1995]. Boletim

da República, Série I, 34, de 23 de Agosto de

1995, pp. 145 – 150. Available online at: http://

www.portaldogoverno.gov.mz/docs_gov/fold_

politicas/outrasPol/politica_aguas.pdf (accessed

20 April 2012).

[12] Resolução nº 46/2007 de 21 de Agosto de 2007.

Aprova a Política de Águas e Revoga a Anterior

Política [New Water Policy, Resolution nº

46/2007 of 21August 2007]. Boletim da Repú-

blica, Série I, 43, de 30 de Outubro de 2007, pp.

730 (49) – 730 (63). Available online at: http://

www.cra.org.mz/lib/legislacao/Politica%20de%20

Aguas%20de%202007.pdf (accessed 20 April

2012).

[13] Estratégia Nacional de Gestão dos Recursos

Hídricos. Aprovada na 22ª Sessão do Conselho

de Ministros de 21 de Agosto de 2007 [National

Strategy for the Management of Water

Resources]. Available online at: http://waterwiki.

net/images/f/f2/Mozambique_-_National_

Water_Management_Strategy.pdf (accessed 20

April 2012).

[14] Decreto n.º 45/2006 de 30 de Novembro.

Aprova o Regulamento para a Prevenção da

Poluição e Protecção do Ambiente Marinho e

Costeiro e revoga o Decreto n.º 495/73, de 6 de

415T h e M a p u t o B a y E c o s y s t e m

18 . Management of Maputo Bay

Outubro. [Regulation for the Prevention of

Pollution and Protection of the Marine and

Coastal Environment, Law n.º 45/2006 of 30 de

November]. Boletim da República, Série I, 48,

30 de Novembro de 2006, pp. 254 (1) – 254 (17).

Available online at: http://www.legisambiente.

gov.mz/index.php?option=com_

docman&task=doc_view&gid=143 (accessed 18

April 2012).

[15] Resolução n.º 11/96 de 28 de Maio. Aprova a

Politica Pesqueira e Estratégias de Implemen-

tação. [Fisheries Policy and Implementation

Strategies, Resolution n.º 11/96 of 28 May].

Boletim da República, Série I, 21, 28 de Maio de

1996, pp. 166 (33) – 166 (40). Available online at:

http://www.portaldogoverno.gov.mz/docs_gov/

fold_politicas/outrasPol/politica_pesqueira.pdf

(accessed 18 April 2012).

[16] Plano de Acção para Redução da Pobreza

Absoluta 2001-2005 (PARPA I), Versão Final

Aprovada pelo Conselho de Ministros em Abril

de 2001. [Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper

2001-2005]. Available online at: http://www.

extensao-protecsocial.com/components/com_

eps/ficheiros/MZ_parpa.pdf (accessed 18 April

2012).

[17] Plano de Acção para Redução da Pobreza

Absoluta 2006-2009 (PARPA II) e Matriz de

Indicadores Estratégicos, Versão Final Aprovada

pelo Conselho de Ministros a 2 de Maio de 2006.

[Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper 2006-2009

and Strategic Indicator Matrix]. Available online

at: http://www.legisambiente.gov.mz/index.

php?option=com_docman&task=doc_

view&gid=127 (accessed 18 April 2012).

[18] Plano de acção para a redução da pobreza,

2011-2014 (PARP III), Versão Final Aprovada

pelo Conselho de Ministros a 3 de Maio de 2011

[Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper 2011-2014].

Available online at: http://www.misau.gov.mz/pt/

misau/destaques/plano_de_accao_para_redu-

cao_da_pobreza_parp_2011_2014 (accessed 18

April 2012).

[19] Lei nº 3/90, de 26 de Setembro. Aprova a Lei de

Pescas. [Fisheries Law, Law n.º 3/90 of 26

September]. Boletim da República, Série I, 39,

26 de Setembro de 1990, pp. 250 (5) – 250 (14).

Available online at: http://www.legisambiente.

gov.mz/index.php?option=com_

docman&task=doc_view&gid=56 (accessed 18

April 2012).

[20] Decreto nº 43/2003, de 10 de Dezembro. Aprova

o Regulamento Geral da Pesca Marítima

(REPMAR) [General Regulations on Marine

Fisheries, Decree nº 43/2003 of 10 December].

Boletim da República, Série I, 50, 10 de

Dezembro de 2003, pp. 550 – 583. Available

online at: http://www.legisambiente.gov.mz/

index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_

view&gid=59 (accessed 18 April 2012).

[21] Lei nº 19/2007, de 18 de Julho. Aprova a Lei de

Ordenamento do Território. [Land Use Planning

Law, Law n.º 19/2007 of 18 de July]. Boletim da

República, Série I, 40, 18 de Julho de 2007, pp. 1

– 16. Available online at: http://www.legisambi-

ente.gov.mz/index.php?option=com_

docman&task=doc_view&gid=138 (accessed 18

April 2012).

[22] Decreto n.º 23/2008 de 1 de Julho. Aprova o

Regulamento da Lei de Ordenamento do

Território. [Land Use Planning Law Regula-

tions, Decree n.º 23/2008 of 1 de July]. Boletim

da República, Série I, 26, 1 de Julho de 2008, pp.

214 (21) – 214 (35). Available online at: http://

www.legisambiente.gov.mz/index.

php?option=com_docman&task=doc_

view&gid=145 (accessed 18 April 2012).

[23] Decreto nº 45/2004, de 29 de Setembro. Aprova

o Regulamento Relativo ao Processo de

Avaliação do Impacto Ambiental. [Environmen-

416 T h e M a p u t o B a y E c o s y s t e m

IV . Cross Cutting Issues

tal Impact Assessment Regulation, Decree nº

45/2004 of 29 September]. Boletim da Repú-

blica, Série I, 39, 29 de Setembro de 2004, pp.

406 (1) – 406 (17). Available online at: http://

www.legisambiente.gov.mz/index.

php?option=com_docman&task=doc_

view&gid=31 (accessed 19 April 2012).

[24] Resolução n.º 18/2007 de 30 de Maio de 2007.

Aprova a Política de Ordenamento do Território

[Land Use Planning Policy, Resolution n.º

18/2007 of 30 May 2007. Boletim da República,

Série I, 22, 30 de Maio de 2007, pp. 204 – 208.

Available online at: http://www.legisambiente.

gov.mz/index.php?option=com_

docman&task=doc_view&gid=133 (accessed 19

April 2012).

[25] Decreto Presidencial nº 6/95, de 29 de

Novembro. Define os Objectivos e Funções do

Ministério para a Coordenação da Acção

Ambiental. [Defines the objectives and

functions of the Ministry for the Coordination of

Environmental Affairs, Presidential Decree nº

6/95 of 29 November. Boletim da República,

Série I, 48, 29 de Novembro de 1995, pp. 230 (1)

– 230 (2). Available online at: http://www.

legisambiente.gov.mz/index.php?option=com_

docman&task=doc_view&gid=83 (accessed 19

April 2012).

[26] Diploma Ministerial nº 265/2009, de 16 de

Dezembro. Aprova o Estatuto Orgânico do

Ministério para a Coordenação da Acção

Ambiental e Revoga o Diploma Ministerial nº

29/2007 de 18 de Abril. [Approves the structure

of the Ministry for the Coordination of Environ-

mental Affairs, Ministerial Diploma nº 265/2009,

of 16 de December]. Boletim da República,

Série I, 50, 16 de Dezembro de 2009, pp. 254

– 267. Available online at: http://www.mozlii.org/

files/node/1207/boletim_da_rep_blica_i_s_

rie_n_mero_50_200_82166.pdf (accessed 19

April 2012).

[27] Decreto nº 6/2003, de 18de Fevereiro. Cria o

Centro de Desenvolvimento Sustentável para as

Zonas Costeiras, abreviadamente designado por

CDS-ZONAS COSTEIRAS e aprova o

respectivo Estatuto Orgânico. [Creates the

Centre for the Sustainable Development of

Coastal Zones and approves the respective

Organisational Statute, Decree nº 5/2003 of 18

de February]. Boletim da República, Série I, 7,

18 de Fevereiro de 2003, pp. 40 (7) – 40 (7).

Available online at: http://www.legisambiente.

gov.mz/index.php?option=com_

docman&task=doc_view&gid=86 (accessed 19

April 2012).

[28] Decreto n.º 16/2007 de 10 de Abril. Cria o

Centro de Pesquisa do Ambiente Marinho e

Costeiro (CEPAM) [Creates the Centre for

Research on the Marine and Coastal Environ-

ment, Decreto n.º 16/2007 of 10 de April].

Boletim da República, Série I, 14, 10 de Abril de

2007, pp. 118 (4) – 118 (6). Available online at:

http://www.legisambiente.gov.mz/index.

php?option=com_docman&task=doc_

view&gid=142 (accessed 19 April 2012).

[29] Diploma Ministerial nº 91/99, de 25 de

Agosto. Aprova o Estatuto Orgânico-Tipo das

Direcções Provinciais para a Coordenação da

Acção Ambiental. [Model Statute of the

Provincial Directions for The Coordination of

Environmental Affairs, Ministerial Diploma nº

91/99 of 25 of August]. Boletim da República,