The Poster at the Modern: A Brief History Author(s): Christopher Lyon Reviewed work(s): Source: MoMA, No. 48 (Summer, 1988), pp. 1-2 Published by: The Museum of Modern Art Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4381045 . Accessed: 02/10/2012 10:53 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. . The Museum of Modern Art is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to MoMA. http://www.jstor.org

Lyon - Poster at the Modern - Brief History - MoMA.pdf

Jan 02, 2016

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

The Poster at the Modern: A Brief HistoryAuthor(s): Christopher LyonReviewed work(s):Source: MoMA, No. 48 (Summer, 1988), pp. 1-2Published by: The Museum of Modern ArtStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4381045 .Accessed: 02/10/2012 10:53

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

The Museum of Modern Art is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to MoMA.

http://www.jstor.org

The Museum of Modern Art MembersQuarterly

0 umr18

This summer, THE MODERN POSTER (through September 6) presents over three hundred

works from the collection of The Museum of Modern Art. The exhibition, organized by

Stuart Wrede, Director, Department of Architecture and Design, is thefirst comprehensive

survey of the collection in twenty years. Wrede's essay in the publication accompanying

the exhibition describes the role of the poster in the overall development of modern art.

The history of the poster at the Museum itself; examined in this issue of MoMA, provides

insights into the Museum's own development.

The Museum was founded in a period "when a reevaluation of Western artistic sen-

sibilities was taking place in all the arts" Wrede writes. "Not only was the new art seen as

inseparable from the social and industrial changes of the day, but there was an unprece-

dented cross-fertilization among the various mediums:" Posters, which demonstrated this

process, fascinated Alfred H. Barr, Jr., founding director of the Museum. "The poster,"

Wrede continues, "a medium of its time, has always existed at the junction of the fine and

applied arts, culture and commerce.... Its approximately one-hundred-year history coin-

cides with that of modern art itself."

-GEWVERRB/E SEUMl

DER BUCHDLC

1-9. NAAR Z- 3OAP RI L 19I.22' EOFNET' VON 1O -12&2-6 UHR E7 EINT I TT F REt

Niklaus Stoecklin. Der Buchdruck

(Book Printing). 1922. Lithograph.

Gift of The Lauder Foundation,

Leonard and Evelyn Lauder Fund. The Poster at thelodern.

The prehistory, so to speak, of the poster at The Museum of Modem Art begins several years before the Museum's founding in 1929. In January of 1927, Alfred Barr in- troduced at Wellesley College a course in modem art, the first in any college to deal not only with painting and sculpture but with graphic design, photography, music, film, and architecture. Of the graphic arts, Barr wrote, 'Advertising is the happy hunt- ing ground of this group, showing how the modem pictorial style has filtered into the ordinary environment of life"

The following July, Barr sailed for London to begin a twelve-month tour of Europe on a traveling scholarship arranged by Paul J. Sachs, a professor at Harvard whose famous museum course Barr at- tended. In October, Barr was joined by his friend Jere Abbott, who would soon become Associate Director of the new Museum of Modem Art. After visiting Holland, they travelled to Dessau, in Ger- many, and spent four days at the Bauhaus. On the day after Christmas, they arrived in Moscow. They remained in the Soviet Union for nearly two months.

Philip Johnson, who met Barr in 1929, would become the founding director of the Museum's Department of Architecture in 1932. The experience of the Soviet Union was a "key" one, Johnson says, for the development of Barr's concept of the inter- relatedness of the arts that found expres- sion in his program for the Museum: "The Constructivists were on his mind all the time. Malevich was to him, and later to me, the greatest artist of the period. And,

you see, the Constructivists were cross- disciplinary, and I'm sure that influenced Alfred Barr, both that and the Bauhaus. When Alfred was in Russia in the twenties, the posters were new, the films-the great- est films ever done -were still new ... [the experience] got him interested in a museum that would cross the lines"

In Russia, Barr and Abbott met such artists as El Lissitzky and Alexander Rodchenko, with his wife, Varvara Stepanova (these three on the same day). They met Sergei Eisenstein and saw four reels of his film October (1928), made for the tenth anniversary of the Russian Revo- lution. Among the posters they brought back is 1917 (1927) by Yakov Guminer, in- cluded in this summer's exhibition, which presents a photomontage of stills from Eisenstein's famous film.

Barr and Abbott visited three times the Moscow art school known as Vkhutein, an acronym from the Russian name for the Higher State Art-Technical Institute, where Lissitzky, Vladimir Tatlin, and Rodchenko all taught. Similar in conception to the Bauhaus, it included departments of print- ing, typography, and graphic arts. They also met with Konstantin Umansky, head of TASS, the foreign news commission. Barr asked for his ideas about a proletarian art. Umansky, he noted, "repeated the com- monplace that the various modem move- ments were far beyond the grasp of the proletariat and then suggested that a pro- letarian style was emerging from the wall newspaper with its combined text, poster, and photomontage;' a suggestion which Barr found "interesting and acute:'

Barr resumed teaching at Wellesley in the autumn of 1928 and the following spring mounted an exhibition, titled MODERN EUROPEAN POSTERS AND COM- MERCIAL TYPOGRAPHY, at the Wellesley College Art Museum (May 2-22, 1929). This was only the second exhibition Barr had organized. It was accompanied by wall labels that not only identified the items but explained the subject, if necessary, and re- lated the works to developments in modem painting. A poster by E. McKnight Kauffer for the London Underground, for example, was said to correspond to "the third phase of cubism (c. 1915)' suggesting that Barr had yet to formulate the classic two-stage model of Cubist development established by his 1936 Museum exhibition CUBISM AND ABSTRACT ART.

An unsigned article in the Wellesley

College News of May 2, 1929, makes the point, which Barr repeatedly stressed, that posters demonstrate the connection be- tween modem art and "the utilitarian ends of modem life:" They are said to embody the principles of modem movements in painting and also to reflect national tem- perament. The Russian posters, for exam- ple, which "embody cubistic principles"' are "more virile, perhaps because their aim is nationalistic rather than hedonistic" The writer concludes by speculating about the "sluggish" development of poster art in the United States: "Is it that we do not demand and hence necessitate the merg- ing of the fine arts with the economic and social ends of our age? Are we too materialistic -or too unadventurous?" Whoever the author may have been, the provocative voice of Barr is heard in the question.

During the Museum's first fifteen years, poster activity flourished under the lead- ership of Barr, who in 1929 became the inaugural director. In 1933, two poster competitions were conducted by the newly established Department of Architecture, the first for New York high school students and the second a typography exhibition for which more than five hundred works were submitted from around the country.

The first published posters formally acquired for the collection included a gift from Mr. and Mrs. Stanley Resor of twenty-three advertising posters by A. M. Cassandre. These were the basis for the 1936 exhibition POSTERS BY CASSANDRE, for which the artist designed the cata- logue's cover, featuring the image of a

(continued on next page)

0 *U-

m

Herbert Bayer's poster Kan-

dinsky on His Sixtieth Birth-

day (1926) is an example of

Bauhaus graphic design that

was acquired by Alfred Barr

and Jere Abbott in Dessau

in 1927.

ANHALTISCHER KUNSTVEREIN JOltANNISSTR.

13

KANDI 4KVD 60. ....UT

, a e Gefne |wche 'Sontagi

5 n -1

M.

g~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~It w mitoleder; re

G 13U RTSTAG Nc%ig

Right to left: Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Jere Abbott,

and their guide Piotr in Moscow, 1928,

pictured on a souvenir postcard.

0~~

a

0 N

a.~~~~~~c

El Lissitzky. USSR Rus- I _A

sische Ausstellung (Rus- CO

sian Exhibition). 1929. Z

Gravure. Gift of Philip

Johnson, Jan Tschichold

Collection.

youth whose eye is pierced by an arrow symbolizing the message of the poster. Curator Ernestine M. Fantl, organizer of the Cassandre exhibition, observed that his designs, which occupy a prominent place in this summer's exhibition, avoid the for- mulas of American advertising, which is based on sex appeal, statistics, and fear. His railway and steamship posters, she wrote, "merely give you the excitement and magic of travel:'

In the summer of 1936, Fantl visited the London Passenger Transport Board, where she selected sixty-three posters for the Mu- seum's collection, a number of which were included in the 1937 exhibition POSTERS BY E. McKNIGHT KAUFFER. In a foreword to the McKnight Kauffer catalogue, which also featured a cover designed by the artist, Aldous Huxley remarked that Kauffer avoided appeals to "extraneous matters' like sex and snobbery. Instead, the artist preferred "the more difficult task of adver- tising products in terms of forms that are symbolic only of these particular products. Thus, forms symbolical of mechanical power are used to advertise powerful ma- chines. . . " Comments like these by Fantl and Huxley, critical of conventional adver- tising, confirm that the Museum did not simply present examples of "good design"' but promoted fundamental alternatives to the prevailing visual culture.

Also in 1936, the landmark exhibition CUBISM AND ABSTRACT ART opened at the Museum. It was, wrote Irving Sandler, "Barr's kind of show, encompassing paint- ing, sculpture, construction, photography, architecture, theater, films, posters, and ty- pography:" Approximately a dozen posters were included, as well as other examples of typography influenced by developments in modern art.

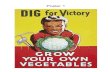

During World War II, posters became a vital medium for propaganda in the United States. In the early forties, the Museum held three poster competitions in support of the war effort. The National War Poster Competition of 1942 featured two hundred works selected from 2,224 entries from around the nation. The Museum gave the public the opportunity to participate by providing ballots and polling visitors on

which poster they liked best, which poster made them want to do more to help win the war, and whether there was an important idea that they did not see represented. President Roosevelt congratulated the art- ists: "It is proof of what can be done by groups whose ordinary occupations might seem far removed from war"

In Art in Progress, a publication accom- panying the Museum's fifteenth-anniver- sary exhibition, Monroe Wheeler, then director of exhibitions, noted that the Mu- seum had acquired, by 1944, "an admira- ble collection of nearly five hundred posters:' In fact, there may have been a great many more posters in the collection at that time, and curators were becoming alarmed by the deterioration of some items, poor storage conditions, and inad- equate or nonexistent cataloguing. The problems were aggravated by the failure to locate the collection within one department and by a lack of funding.

In 1949, Mildred Constantine was ap- pointed Assistant Curator in the newly des- ignated Department of Architecture and Design, which was to have responsibility for the poster collection (the departments of Film and of Prints and Illustrated Books retain responsibility for specialized areas of the collection).

On a recent morning, Constantine de- scribed her initial effort to assess the role of the poster collection. Her modest apart- ment's harmony of furnishings, art works, and books made it seem a cool refuge from the noisy midtown Manhattan street below. She sat at a glass-topped work table, her imposing presence suggesting the deter- mination she brought to the task of giving shape to the Museum's poster holdings. "Was there a clear conception of what the collection should be?" she had asked. "What kind of uses did it have within the Museum?"

She researched major private collec- tions, including that of Jan Tschichold. In 1937, an important collection of about sev- enty-five posters had been purchased from Tschichold. It included examples done in the 1920s and 1930s in Germany, Czecho- slovakia, Hungary, Switzerland, and the U.S.S.R. Tschichold, a distinguished

graphic designer, is represented in this sum- mer's exhibition by typographical posters of the 1930s whose spare, Constructivist- inspired designs prefigure the innovations of the postwar Swiss school.

In 1949, Constantine recommended a further purchase from Tschichold of graphic materials, including additional posters. Complementing this body of work

was the 1950 gift by Bernard Davis, a Phil- adelphia collector and philanthropist, of French and English work from the late 1920s and early 1930s. One of Constantine's most important contributions was her initiation of a graphic arts exchange pro- gram with the Library of Congress, where she had formerly worked, as well as the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, the Musee des Arts Decoratifs, Paris, and the Glasgow Institute of Fine Arts. This program brought many fine posters into the collection.

Constantine and Johnson shared Barr's conviction that posters were both artistic and historical documents. "Barr saw the poster two ways' she explained, "as re- flective and informative of the aesthetic and of the social and political era repre- sented by it. What era did it come from, what country, and how did the artist reflect all the impulses that were going on at that time? Alfred was extremely aware of these things:'

Constantine organized a wealth of poster exhibitions through the 1960s, beginning with an exhibition on the subject of combat- ting polio. A select group of designers, photographers, painters, and sculptors were invited to work on this project, among them David Smith, who did a medallion of St. George fighting the polio dragon.

Constantine's innovative show of New York Times posters (1952), which she in- stalled outdoors in the Museum's sculpture garden, explored "how a newspaper, which is one visual, graphic medium, could use another graphic medium:" Constantine also selected posters for the Museum's twen- tieth-anniversary exhibition, the 1953 MODERN ART IN YOUR LIFE.

The culminating poster exhibition of her career was the 1968 WORD AND IMAGE, the first comprehensive survey of the history of posters and typography in the modem period, organized with Arthur Drexler, then director of the department. It was pre- sented in a stunning installation in which many of the posters were in very deep frames, so that they appeared to be pro- jecting themselves from the walls. In an essay in the exhibition catalogue, Alan Fern suggested that the history of the tradi- tional poster might be coming to an end. Ironically, the Museum also presented, in that unsettling year, a hastily orga- nized response to the student uprising in Paris, PARIS: MAY 1968, POSTERS OF THE STUDENT REVOLT.

Since WORD AND IMAGE, poster exhibi- tions have been divided between ones de- voted to individual artists, such as the 1985 POSTERS BY FRANCISZEK STAROWIEYSKI, an examination organized by Robert Coates of work by one of Poland's foremost graphic designers, and surveys of recent acquisitions. In 1968, there were some two thousand posters in the Museum's collec- tion. Since that time, the number has ap- proximately doubled. More than two-thirds of the works included in THE MODERN POSTER have been acquired since 1968.

Many individuals have helped make this growth possible. Close to one hundred posters have been acquired for the Museum since 1980 with the support of Leonard A. Lauder. Fifty-two of these are featured in this summer's exhibition. His contributions include such important works as Ludwig Hohlwein's Deutsches Theater (1907) and Niklaus Stoecklin's Der Buchdruck (1922).

Stuart Wrede concludes his essay in the publication accompanying this summer's exhibition with the observation that the poster "has proved to be a remarkably re- silient medium, adapting itself to a variety of aesthetics and uses:" While it is no longer a primary vehicle for commercial advertising, it remains significant "as a reproducible popular-cultural medium that can be used by all-from large institutions to small cultural or political movements and individuals -to give visual expression to their ideas and beliefs.... [The] poster at its best has been, and continues to be, an extraordinary social and artistic document'

-Christopher Lyon

THE MODERN POSTER and its accompany- ing publication have been supported by a generous grantfrom The May Department Stores Company. Additional support has been provided by the National Endowment for the Arts.

This is the Enemy (1942),

by Victor Ancona and Karl

Koehler, was a winning

entry in the Museum's

1942 National War Poster

Competition.

This is the Enem

L

A. M. Cassandre's little Dubonnet man, his most famous creation (seen filling himself with drink in

Dubo Dubon Dubonnet [1932]), has "the universal appeal of Mickey Mouse" observed Ernestine

M. Fantl, organizer of the Museum's 1936 Cassandre exhibition.

II II

a1 biJ.

Installation view of the

1968 exhibition WORD AND

IMAGE.

Nelson Rockefeller and

Mildred Constantine be-

side a poster installed in

the Museum sculpture gar-

denfor the 1952 New York

Times poster exhibition,

Related Documents