Part III Passing as “Real” pal-mock-05.qxd 4/27/07 2:40 PM Page 121

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

Figure 3: Sandra Bernhard performing at the Sydney Gay+Lesbian Mardi Gras Festival, State Theatre 1996

Source/Credit: Mazz Image from the book You & Mardi Gras; images by MAZZ (MazzImage.com)

pal-mock-05.qxd 4/27/07 2:40 PM Page 122

5

“Fuck ’Em If They Can’tTake a Joke!”

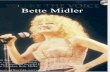

This chapter explores the way Sophie Tucker’s legacy reinscribed itselfin late twentieth-century America through the work of Bette Midler

and Roseanne. Like Tucker’s, theirs are performing presences that expressracialized sexual difference through comedy and grotesque displays ofgendered otherness and indicate how staged displays of artifice, vulgar-ity, consumption, and non-maternal performativity can continue to act asmediating agents between dominant culture and its abjected elements.Although Sophie Tucker was certainly considered “dirty” in the first decadesof the twentieth century, her later reputation as a “foul-mouthed” come-dian to some extent rests on an homage. A decade after Tucker’s death,Bette Midler began including “Soph” stories in her cabaret performances,routines which were considered “truly filthy” at the time.1 Although thejokes were not from Tucker’s repertoire, the impression was that they “cer-tainly could have been—and which nevertheless made the late Tucker arevitalized legend in her own right.”2

A typical “Sophie Tucker joke” involves Soph (who is identified withMidler), her boyfriend Ernie, or her friend Clementine, who variouslyappears as a prostitute or stripper (and is usually described as “a filthy vul-gar old broad not unlike myself”). The stories always begin with the line “Iwill never forget it you, you know.” Here are three of the most famous (or,at least, my favorites) from a Midler fan site, the third of which is told inher 1980 concert film, Divine Madness:

I will never forget it, you know. I was in bed last night with my boyfriendErnie and he said to me,“Soph, you got no tits and a tight box.” I said to him,“Ernie, get off my back!”

I will never forget it, you know. Doorbell rang the other day, answeredthe door and there was a delivery boy there with two dozen roses. I grabbed

pal-mock-05.qxd 4/27/07 2:40 PM Page 123

124 JEWISH WOMEN ON STAGE, FILM,AND TELEVISION / ROBERTA MOCK

the card. I opened it. It said “Love, from your boyfriend Ernie.” I was havingtea with my girlfriend Clementine. I said, “Clementine, do you know whatthis means? For the next two weeks I’m gonna be flat on my back with my legswide open.” Clementine says to me, “What’s the matter, ain’t you got a vase?”

I will never forget it, you know. I was terribly drunk the other night. Iwoke up and there was an elephant in my bed. I said, “Lord have mercy,I must’ve been tight last night.”“Well,” said the elephant, “kinda.”

The erotic, excessive, flexible, knowledgeable physicality of the Jewess isalways foregrounded in these shticks (even when she and Ernie aredescribed as being over eighty years old).

Stephen Holder in the New York Times observed that in a “liberated era”of “uninhibited self-expression,” “Ms. Midler reigns as its radiant highpriestess.”3 Her position within mainstream culture was more recentlyconfirmed when she appeared as the centerpiece of the tribute concert forthe people who died in the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.According to the BBC website (September 24, 2001), “When Hollywooddiva Bette Midler performed her inspirational anthem, ‘Wind Beneath MyWings’ and the line ‘Did you ever know that you’re my hero?’ many in thecrowd began sobbing.” Midler’s performativity has always, like Tucker’s(especially at the height of her career), included a hip finesse, an emphasison artifice, and a confident sexuality, as well as a mawkish sentimentality.And like so many Jewish female performers, this performativity is oneborne of difference.

In a 1971 interview, Midler says that she was miserable as a child due tothe way she looked: “I was a plain little fat Jewish kid. I spent a lot of timereading and listening to the radio. I had to find my own style or I was goingto get screwed, but once I made my mind up it all fell into place.” This style,as she described it at the time, was “grotesque”: “I’m much more grotesquethan Barbra Streisand. Grotesque to me is not a bad word. There are anynumber of performers around today who are above and beyond normal.”4

So, while her self-positioning as a symbol of mainstream American cul-ture may have originally begun as an ironic gesture, at a specific historicalmoment of cultural and political anxiety, Midler could represent the unityof America in much the same way Rachel and Sarah Bernhardt did forFrance in the nineteenth century.

Midler’s “Divine Miss M” persona consistently and conscientiously cap-italized on a distinct Jewish female performance tradition. In addition toher Sophie Tucker jokes, her live shows in the 1970s included a particularlysilly impersonation of Shelley Winters in The Poseidon Adventure and ref-erences to Belle Barth (during her Clams on the Half-Shell revue, Midlerwould respond to hecklers with the line,“Belle Barth used to say, ‘Shut your

pal-mock-05.qxd 4/27/07 2:40 PM Page 124

hole, honey. Mine’s makin’ money’”).5 Her “divinity” alludes to Bernhardt(and also a tradition of female impersonation which, as discussed inChapter 1, is not unrelated) and early advertisements for her shows featuredimages of Midler “doing” Streisand (another perennial favorite of dragqueens). To a large extent, Midler’s performance work cross-referencesJewish women and gay men. My discussion here will focus specifically onthe film version of her “time-capsule” concert performance, Divine Madness,where this can be most clearly illustrated. It also represents the point inMidler’s career at which she took stock of her past as a performer whileconfirming the performing persona for which she continues to be associ-ated despite her work in other media and genres.

At the start of Divine Madness, Midler is carried onstage on a silver plat-ter by four men. She powders her nose ironically; she frenetically minces,shimmies, jiggles, wiggles (as she also does when delivering her Soph jokes),and—given her faux glamorous showgirl costuming (which she claims is“not a garment” but “an investment”)—shakes her tail feathers. In betweenthe choruses of “Big Noise from Winnetka,” in which the lyrics claim thatshe’s “a scandal too hot to handle,” Midler confides to the audience that sheis “once again falling into the vat of vulgarity”:

O tut tut. I did so want to leave my sordid past behind and emerge from thisproject bathed in a new and ennobling light. I wanted to come out and be thesweet unadorned person that I really am. I wanted to show you the goodbeneath the gaudy. The saint beneath all this paint. The sweet pure winsomelittle soul that lurks beneath this lurid exterior. But fortunately, just as I wasabout to rush down the path of respectability and righteousness a wee smallvoice called out to me in the night and reminded me of the motto by whichI’ve always tried to lead my life: ‘Fuck ’em if they can’t take a joke!’

After this climax, she belts out the lyrics: “I am the one they call the BigNoise. I am a living work of art.”6

The direct reference to the artifice of femininity performed theatricallywith ironic disjunction is the most obvious signifier of Midler’s camp strat-egy. However, Alan Sinfield notes that camp, deriving as he sees it from theWildean dandy (although this is equally applicable to Bernhardt’s Jewess),is also an allusion to leisure-class manners, “a ‘sorry I spoke’ acknowledge-ment of its inappropriateness in the mouth of the speaker.” Like SophieTucker’s use of double entendre, Midler’s wrestling with “appropriateness,”the struggle she displays between acceptable and non-acceptable behavior,is also a class issue.“Posh culture is recognized, implicitly, as being a leisuredpreserve, though perhaps impertinently invaded. Camp is not, therefore, asis usually imagined, grounded only, or even mainly, in an allusion to the

“FUCK ‘EM IF THEY CAN’T TAKE A JOKE!” 125

pal-mock-05.qxd 4/27/07 2:40 PM Page 125

femininity that is supposed to characterize women.”7 The performanceof femininity is the performance of white middle-class respectability, “nat-uralized” through gendered expectation.

Midler developed her highly flamboyant and deliberately outrageousact from the moment she began her career at the Continental Baths in NewYork in the late 1960s, in front of an intimate, nearly-nude all-male gayaudience.8 Although she had landed a part in the long-running Broadwayproduction of Fiddler on the Roof (moving from the chorus to playing oneof Tevye’s daughters) and had been appearing Off-Off Broadway and onthe avant-garde theater scene for at least five years, she still had not foundher niche. Her early cabaret shows at the Continental, accompanied by athen-unknown Barry Manilow on piano, primarily featured torch songsand period ballads, and she quickly needed to build on this to develop acredible rapport with her audience. Kevin Winkler, who has traced theeffects of this audience-performer relationship, notes,

By flaunting “trashy” clothes and using vulgar gestures not used by femalesingers in more traditional nightclub settings, Midler subverted the notionof “passing for straight” (e.g. conforming to conventional feminine stan-dards of decorum) and further underlined the outsider status she sharedwith her audience.9

Midler learned how to be a “lady” primarily from gay men, and their appre-ciation of ironic distancing, camp connoiseurship, and parodic appropria-tion of the notion of a stable gender identity were studied as part of thelesson. As a result of this transaction, she acts as if she has balls under herdress, even though (or because) she emphasizes her full physical attributesand is explicit in presenting her own heterosexuality. “Look alive! Yourmother is up here working!” Midler would command her bathhouse audi-ences, using a quintessential gay expression reserved for the most respecteddrag queens.10 It is implicit that her emphasis on artifice is not sustainable,nor is this desirable. Neither the means nor these messages were aban-doned when Midler began to perform to mainstream audiences.

Michael Bronski once described Midler as “a female female imperson-ator,”11 and her monologue during “Big Noise” shows how she bothacknowledges and accentuates this image. Her “sordid past,” the one shecan’t leave behind, conflates the drag queen and hyper-feminine Jewess.She considers “coming out” as “unadorned” and “pure,” an image (howeverhighly constructed) of heteronormative femininity, but she decides she’drather keep the saint concealed beneath the paint. The “lurid exterior”heightens her complexity; the “winsome little soul” is not entirely her. Thejoke she refers to, applying one of Philip Core’s definitions of camp, is a

126 JEWISH WOMEN ON STAGE, FILM,AND TELEVISION / ROBERTA MOCK

pal-mock-05.qxd 4/27/07 2:40 PM Page 126

little lie that tells the truth.12 It can also be seen, however, as an attempt toboth signify and allay the fears of a (real or prospective) threatened audi-ence. Midler explicitly refuses to be labeled “normal,”“straight,” or “real” inher monologue, and these categories are presented together as a package.As Terry Eagleton has stated, “If representation is a lie, then the very struc-ture of the theatrical sign is strangely duplicitous, asserting an identitywhile manifesting a division, and to this extent it resembles the structureof metaphor.”13 Midler’s body becomes iconographic and this serves tosignify the duplicity of her performance text.

The performer who expressly performs her performativity is necessarilyan (occasionally privileged) “outsider” looking in. Midler acknowledgesthis in Divine Madness when asked to tell “the taco joke” (which we neverhear). With echoes of Sophie Tucker, she replies “I know just how far I cango with the American public,” implying that she herself goes much further,beyond being an “American” woman. Camille Paglia is one of many cul-tural commentators who has noticed that only drag queens now act as“ladies.” She has also asserted that “the drag queen re-creates the dreamlikeartifice of culture that conceals the darker mysteries of biology” and “ritu-ally acts out and exorcises our confusions and longings.”14 LaurenceSenelick furthers this shamanic identification by interrogating the transac-tion between cross-dressed performer and spectator:

The actor is thus a shadow of the shaman, one step further removed from thesupernatural, but still simulating, still using his body as a vehicle for the layspectator’s vicarious inspiration by travelling back and forth across the fron-tiers of gender and carrying with him fantastic contraband.15

A performer like Bette Midler who uses the tropes of the drag queenbecomes valued both as the bearer of a wonderful gift in the form of a non-oppressive model for gendered behavior and the foolish scapegoat whosegift is laughed at.16 The laughter is part of the gift. And while the DivineMiss M says “Fuck ’em!” of those who don’t laugh, Midler certainly sawherself as a role-model at this time. In a 1981 Photoplay interview, she wasquoted as saying, “I want to be a heroine, a person others can model them-selves on. I don’t think this is outrageous. When you see you can be some-thing other than ordinary, you tend to want to be that. I want to be aninspiration.”17

In a 1973 Ms. magazine feature exploring the ‘meaning’ of Midler’srapid rise as a celebrity, playwright Myrna Lamb discusses her appeal injust these terms. For her, Midler creates a public space in which an audi-ence may “see clearly the essential drag-queen role societally assigned tothe female”:

“FUCK ‘EM IF THEY CAN’T TAKE A JOKE!” 127

pal-mock-05.qxd 4/27/07 2:40 PM Page 127

Bette Midler puts that role on in her dressing room. Tits and ass along withthe sequins and the merry-widow corset cover. She makes the drag-queen tripas potent as the supermale (Frank Sinatra from Hoboken, New Jersey) trip.

She is the votive offering of her own emotive ritual. . . . “Nice ass, huh?” inJewish New York camp location. The audience roars its approval. She demandsmore response, “Come on! What do ya think I’m up here workin’ my titsoff for?”

Her little breast-burdened body is plainly her conveyance. She rides it outand wheels on all the fabled female roles: thirties Billie Holiday, all theAndrews Sisters . . . the lonely little nobody at the radio, listening to and wait-ing for the superstar. But the trick is, we never forget the superstar she iswaiting for is Bette Midler!

At the heart of Midler’s performing persona is contradiction. The othertributes to her in this issue of Ms. celebrate the opposites that tend to reaf-firm rather than cancel each other out: Midler is “real” and “honest” and“vulnerable”; she is “hungry,”“cynical,” and “sentimental”; she is a “clown”and a masochistic “whore-woman”; “she is bawdy, obscene, and self-betraying”; it’s “all show business, just an act.”18 These adjectives resonateremarkably with the tropes of the Jewess.

By the late twentieth century, overt racial signifiers applied to Jewishwomen had become little more than traces (much like “sexual” onesapplied to Jewish men); assumptions about physicality and performedbehavior in orientalist terms, however, still remain and are used by femaleJewish performers, although the original referents are mainly obscured.Edward Said has argued that orientalist discourse was most consistentlygenerated and used by colonialist powers such as Britain, France, andAmerica; this is why he primarily locates his thesis in Orientalism withinthis framework. He also, notes, however, that the focus of Orientalismchanges when it is appropriated by America in the twentieth century.American Jews were very rarely identified as “oriental” in the way theywere in Europe at the fin de siècle. As discussed earlier, performers likeAnna Held, in fact, used a generalized “oriental” exoticism as a mask forJewishness (ironically displacing Jewishness with a performance of per-ceived “European” sophistication in the process).

By the end of the second world war, North Americans used “Orient” torefer primarily to the Far East and Muslim countries, rather than India and“biblical lands” (read as almost exclusively Palestine). This roughly corre-sponds with the emergence of the United States as a superpower and thecreation of the state of Israel. These observations may help to contextualizeMidler’s fascinating relationship with orientalism, one that turns the per-ception of racial Jewishness discussed in earlier chapters on its head and

128 JEWISH WOMEN ON STAGE, FILM,AND TELEVISION / ROBERTA MOCK

pal-mock-05.qxd 4/27/07 2:40 PM Page 128

yet still maintains Jewish status as an outsider. Midler was born inHonolulu and (with tongue firmly in cheek) describes her experiencesgrowing up in Hawaii as such: “I was not a hip color. I was white in an allOriental school. Forget the fact that I was Jewish. They didn’t know whatthat was. Neither did I. I thought it had something to do with boys.”19

Midler’s performativity still embeds “race” within gender/sexualitymatrices. One can note her close relationship with her back-up singers, the“Harlettes,” two of whom are usually black women. “They function as aGreek chorus,” Midler tells us.“These girls don’t know shit about Euripidesbut they know plenty about Trojans [condoms].” She urges them to singtheir “siren song and turn men into pigs.”20 As was the case in fin de sièclepaintings, the positioning of black women near a white central figure canbe seen as an attempt to eroticise the main subject through an associationwith blackness. Although a similar ruse in the world of rock music can beread as a (probably unconsciously) racist use of sexual stereotyping,Midler never implies that she is different from the Harlettes. Rather sheis seen as their “queen bee,” a role model; they worship her “like a god,”she tells us.

Midler has also associated herself closely with other “white” female per-formers who are identified with “blackness” (for example, Sophie Tuckerand Janis Joplin, whose “blues” were mainly written by Jewish men, BertBerns and Jerry Ragovoy). Throughout Divine Madness, Midler remindsthe audience that “whiteness” is a cultural construction and that somewomen are perceived as less white than others. Displaying none of Tucker’sawed respect for royalty, Midler relates how, on a trip to the UnitedKingdom, she “got to lay her eyes on Her Royal Heinie, the Queen,” whomshe describes as “the whitest woman in the whole world.” It is clear that thiswhiteness is not only based on class and its displays of consumption butalso on religion: the Queen, she says, “even dresses like a Protestant.”

One of the most celebrated routines in Divine Madness is Midler’s “trib-ute to the lowest form of show business now existing on the planet today:the itinerant lounge act.” Her “Dolores Delago, the toast of Chicago” is,according the Divine Miss M, a woman of “tremendous ambition and abs-olutely no pride at all; a woman of tremendous determination and abso-lutely no skill; a woman of the grandest notions and not the simplest hintof taste.”21 The lounge singer is a figure returned to later by both SandraBernhard in Without You I’m Nothing and Roseanne in her Live fromTrump Castle; interestingly enough, however, her roots can be found inearlier torch singing, often by Jewesses such as Libby Holman (whomMidler has cited as an inspiration) and Fanny Brice. This latter-day ver-sion of the Broadway stage and nightclub singer is recognized by her

“FUCK ‘EM IF THEY CAN’T TAKE A JOKE!” 129

pal-mock-05.qxd 4/27/07 2:40 PM Page 129

sham sentimentality, the falseness of her sincerity, her glamorous gaudi-ness, and her masquerades of intimacy: a “celebrity” without a fan base. Infact, Midler’s performance as Dolores Delago does not stray far from herusual style; she doesn’t sing “badly,” for instance (despite Midler’s earlierclaims about her lack of talent). Nor is her camp flamboyance far removedfrom Midler’s “own” (for example, in “Big Noise”), although it is extendedto massive proportions. As Midler states in her travelogue, A View from aBroad (which, it must be said, is not particularly reliable as autobiography),Dolores “is, let’s face it, a lot like me—or someone I might have become.”22

Dolores is a mermaid who propels herself around the stage in a motor-ized wheelchair, complete with attached phallic palm tree and strategicallyplaced coconuts. It is as Dolores that Midler refers to her orientalism (whilealso satirizing the “tiki” and “exotica” trends prevalent in bars and night-clubs, especially in the 1950s and 1960s): “Now I know you Caucasianshave a hell of a time wrapping your mouths around the Polynesian tongueno matter what size or shape,” she tells the audience before warning themthat “tonight you’re gonna get it in your mouth and you’re gonna like it!”The ridiculous moaning chant which follows is successful; Dolores’s feetmiraculously emerge from her glittery mermaid tail. No longer will menonly be interested in “eating” her, nor will her back-up singers be able tosay, “The question before us is ‘Where’s her clitoris?’” Midler’s mermaid isa well-aimed jibe at perceptions of “womanhood”: a glamorous seductivemonster, a hybrid half-woman/half-animal, a sex object whose female gen-italia have been replaced with a gigantic phallic tail. She is, in fact, the dera-cinated oriental Jewess.

Following her “turn” as Dolores, Midler gives another hybrid perform-ance, this time more explicitly cross-gendered; she sings “Going to theChapel and We’re Going to Get Married” in a costume that is constructedin such a way that she is the “bride” when facing front and “groom” whenher back is to the audience. This elaborate half-man/half-woman act reaf-firms her relationship with the drag artist (as well as variety and music hallperformance and freak shows). Midler’s display of heightened genderedartifice is continued when she appears next as a 1940s beauty pageant con-testant wearing a “Miss Community Chest” sash to sing “Boogie WoogieBugle Boy,” a musical standard of confident Americana. If, as Lenny Bruceonce said,“bosoms” are Jewish, Midler is flaunting her (commodified) eth-nic assets. She is simultaneously, however, inserting her full Jewish figureinto the very fabric of America. The projected background images super-impose her head between the American founding fathers on MountRushmore and then feature a poster of a female Uncle Sam which reads “IWant You!” before the Harlettes open their “baby doll” dresses to reveal

130 JEWISH WOMEN ON STAGE, FILM,AND TELEVISION / ROBERTA MOCK

pal-mock-05.qxd 4/27/07 2:40 PM Page 130

U.S. flags within. America is remade, somewhat optimistically for the time,as sexy, female, and racialized.

After Divine Madness, Midler attempted to put some distance betweenherself and the Divine Miss M she created. This seemed to be a matter ofself-preservation, both professionally and personally. On one hand, Midlerwas canny enough to know that too great an identification with an outra-geous persona would prevent her from breaking into mainstream movies.On the other, however, there is a hint in interviews that there was thepotential for her “real” personality to blur into her performed persona in aself-destructive way. She refers frequently to the way rock star Janis Joplinburned herself out through excess and an acute awareness of her own dif-ference. It is not a coincidence that Midler’s first big Hollywood role was asa fictionalized Joplin in The Rose (1979). For this she was nominated for aBest Actress Oscar and won a Grammy for its theme song, but her nextmovie, Jinxed (1982), in which she plays a lounge singer, flopped.

From the mid-1980s, however, Midler scored box office hits by playinggutsy, sassy women in popular comedies such as Down and Out in BeverlyHills (1986), Outrageous Fortune (1986), Ruthless People (1987), The FirstWives Club (1996), and The Stepford Wives (2004), as well as in the sentimen-tal weepie, Beaches (1988), which she also produced.23 In 1993 she playedMama Rose in a well-received made-for-television version of Gypsy. Whilethis is a musical which erases explicit references to its semi-biographicalcharacters’ Jewishness and (in the case of Mama Rose herself, queerness), italso gave Midler the opportunity to stamp her mark on a complex role thatcelebrates women’s independence and ambition. Perceived as less stridentand “detached” than Streisand, the vulnerability that seeped out of hercabaret characterizations seems to have enabled the packaging of Midler asa safe and lovable eccentric. Like Sophie Tucker and Fanny Brice, she ispositioned and highly valued as a “contrast” to constructions of middle-America; unlike them, however, she has been accepted within its main-stream Hollywood narratives.

In 1989, less than a decade after Divine Madness was made, a fat Jewishwoman appeared on more magazine covers in one year than any other per-son had in recorded history to date.24 Unlike her female Jewish predeces-sors, however, Roseanne Barr actually came to represent middle Americaitself. While following Midler’s lead in her use of woman-centered vulgar-ity, Roseanne differed primarily in her refusal to refer to images of glamourand in her anger. She was confident, unapologetic and uninhibited; withrelatively little “toning down” for a mass audience (and then mainly interms of expression rather than content or performativity), she not onlyreflected an American agenda but shaped it.25

“FUCK ‘EM IF THEY CAN’T TAKE A JOKE!” 131

pal-mock-05.qxd 4/27/07 2:40 PM Page 131

Roseanne rose from obscurity almost overnight, debuting in an epony-mous sitcom based on the cheeto-eating, angry,“domestic goddess” personashe had been honing on the stand-up circuit since the early 1980s. She wasnewly politicized when embarking on this career, a member of a woman’scollective based around a Denver bookshop. It was here she found her voice:“No longer wishing to speak in academic language, or even in a feministlanguage, because it all seemed dead to me, I began to speak as a working-class woman who is a mother, a woman who no longer believed in change,progress, growth, or hope. This was the language that all the women onthe street spoke.”26 And, it would seem, this was the voice that spoke for the“real” America. In 1994, Roseanne was the only television show that couldclaim a top-ten rating in both first-run and syndication (in some Americanmarkets, viewers could watch the sitcom six times a week).

Following bitter battles with the program’s production company duringRoseanne’s first season—the result of which was that its credited “creator”was fired (a pattern repeated for many subsequent directors, producers,and writers)—Roseanne wrested almost complete control over its content.She made a serious amount of money (estimated at $100 million) and wasstill earning half a million dollars for every show in the mid-1990s.According to Roseanne herself (and there is little reason to doubt her onthis point), she was at the time the richest and most powerful woman inHollywood. For her, the reason was intimately bound up with why shewas so frequently in the headlines and why she had a reputation as a “dif-ficult” artist:

There’s a real political point to make here, which is, nobody came to televi-sion or anywhere near the media with the idea that I came with, which is apro-woman idea. . . . They don’t dig that in the press, they don’t dig it at thenetworks, and they never will. So that’s how Roseanne got to be such a bigpersonality and celebrity. If Roseanne came here and weighed 120 poundsand wanted to show her tits, nobody would have said shit.27

Roseanne draws attention to an uncomfortable contradiction at the heartof her popularity. Although fat “has come to represent the very hallmark ofmodernity,” Mary Russo points out that fatness can also be seen as a cate-gory of abjection that signifies lower social status.28 Roseanne is unapolo-getic about her size. As she says on her first HBO television special, “Ifyou’re fat, like, be fat and shut up. And if you’re not, well, fuck you.”

For every loyal fan, Roseanne always had her detractors. Not everyonewanted to be spoken to, or for, in that tone of voice: one New York Postheadline read simply “BARR-F” in response to her aggressive, “unladylike”behavior both on and off screen. On the other hand, some critics felt that

132 JEWISH WOMEN ON STAGE, FILM,AND TELEVISION / ROBERTA MOCK

pal-mock-05.qxd 4/27/07 2:40 PM Page 132

serious issues such as unemployment and child care were being glossedover and defused by her sitcom’s happy endings. It also seemed thatRoseanne was less than appreciated by mainstream feminism. Ann TaylorFleming, for instance, wondered aloud in the New York Times, “Was I justbeing squeamish, a goody-two-shoes suburban feminist who was used toher icons being chic and sugar-coated instead of this gum-chewing, male-bashing, or at least male-baiting, working class mama with a bad mouth?”29

There was one particular incident which alienated even (especially) herworking class audience.

On July 25, 1990, Roseanne was asked to sing “The Star SpangledBanner” between games of a San Diego Padres double-header. Her screech-ing, off-key rendition (made worse by the feedback from the ball parksound system) was met almost immediately with booing and hissing bythe baseball fans, who interpreted it as a deliberate act of anti-nationalism.According to Roseanne, by the end of the national anthem she looked upand saw “64000 Edvard Munch faces” and decided to “punish them withmy voice” by making “the loudest noise I’ve ever made in my life.”30 Shethen hammered the nail into the proverbial coffin; in a parody of the on-field habits of baseball players, she grabbed her crotch and spat.31 The per-formance caused a national uproar; the president of the United Statescalled her “disgraceful.” Roseanne apologized in tears on a talk show, sayingit was the best she could do with a notoriously difficult song. Her ratingsplummeted and sponsors withdrew, but only temporarily. It seems thatAmerica still needed Roseanne.

Despite her public remorse over the incident, Roseanne couldn’t helpcommenting that “If this is the worst thing they ever heard, they’ve had itreally easy,” and four years later in her autobiography she admitted that “it’sthe funniest fucking thing I ever did.”32 She also noted, however, that herdemonization at that time could have been due to political expediency:“[A] day after I sang, Hussein invaded Kuwait. If they wouldn’t have hadme all over the news, if they would’ve paid attention to something decent,they probably could’ve prevented the war.”33 To make a point, Roseannecontinued to “sing”; she wouldn’t be silenced. She was “Woman” and shewould “roar,” as she said frequently, echoing the feminist anthem madepopular by Helen Reddy in the 1970s. Her targets, however, remaineddeliberately confusing.

In her live show from Trump Tower (dressed in a glittery red dress andwhite boa which matched the classic Duesenberg driven onstage by DonaldTrump himself with her as a passenger), she ironically discusses her “awak-ening political consciousness” and laughs when she says that she “had thegood fortune of living on an Indian reservation” in the early 1970s. Her

“FUCK ‘EM IF THEY CAN’T TAKE A JOKE!” 133

pal-mock-05.qxd 4/27/07 2:40 PM Page 133

rendition of the classic peace activist song about Native Americans, “OneTin Soldier,” which follows is outrageously aggressive and out-of-tune. Inthe accompanying monologue she tells us why “what the world needs nowis love”: “If everybody was holding hands, nobody could push the button.And if we all had a great big dick in our mouth, nobody could speak ill ofanother. Let’s start by holding hands.” Roseanne is grotesque, and offensiveto many, even when she is being politically correct.

By early 1990, Roseanne the sitcom was less newsworthy than Roseanneherself. She had become, according to the Wall Street Journal, “the humantabloid.”34 It seems that American readers (whether of the supermarkettabloids or “up-market” newspapers) could not consume enough of thisall-consuming woman. They knew about her divorce from her first hus-band Bill Pentland and her subsequent love affair and marriage to TomArnold, who became her executive producer. Roseanne took his surnameand the media reported their tattoos, their drug addictions, their publicfistfights with paparazzi, their arguments with other celebrities, their“mooning” binges, their abuse in childhood, their therapy, their attemptsto conceive a child, and, finally, their divorce. In 1995, Roseanne marriedher former bodyguard, Ben Thomas and (like Rachel of the Comédie-Française) dispensed with the need for surnames altogether. In fact, by thistime Roseanne the person had very little in common with her televisioncharacter, working-class Roseanne Conner, until both their bodies werepregnant at the same time in the final series of the sitcom.

Ironically, Roseanne’s “realness”—not as a character, but as a person—had become an issue and was consistently emphasized or critiqued in waysthat uncannily mirror popular discussions about Rachel and Bernhardtover a century earlier. A review of Ruby Wax Meets Roseanne (a British tel-evision interview that took place in Roseanne’s Hollywood mansion)comments on her choice of interior decoration: “The walls display theoccasional Old Master (fake) in which Roseanne herself often featuresprominently. . . . But one can forgive Roseanne everything because, unlikeher décor, she is not a fake.”35 When Roseanne initiated divorce proceed-ings against Tom Arnold, the headline of New York’s Daily News read,“Roseanne and Tom end scam, er, split.” Phil Reeves, in The Independent,summed up the questions America was asking, implying that not only thedivorce but the marriage itself was part of “her self-spun mythology”:“[H]as Roseanne Arnold, the diva of television comedy, conned everyone?Has the world been the victim of a cynical publicity campaign aimed atkeeping her ratings among the clouds?”36 A cable television program chartedmajor “Roseanne” stories against the dates of national ratings sweeps and

134 JEWISH WOMEN ON STAGE, FILM,AND TELEVISION / ROBERTA MOCK

pal-mock-05.qxd 4/27/07 2:40 PM Page 134

found an unambiguous pattern that confirmed a degree of media manipu-lation on Roseanne’s part.37

One of the most controversial episodes of Roseanne featured the firstlesbian kiss on national television in America. Roseanne goes to a gay night-club with her friend Nancy (played by Sandra Bernhard) and is kissed onthe lips by Sharon, an erotic dancer/performance artist (played by MarielHemingway). The next morning, we find Roseanne frenetically cleaningthe restaurant in which she works. Her sister, Jackie, has the best line of theprogram: “Boy, if Sharon had slipped you the tongue we might actually getthis place up to code.” Television critic Jasper Rees notes that, if she had,the show would have probably been “wiped off the screen”;38 like SophieTucker and Bette Midler, Roseanne too knew how far she could push theAmerican public when her persona was contained as entertainment andalso how to exceed this beyond her “bound” performances.

Stephen Maddison situates this episode in an assessment of Roseanne’sheterosocial potential (that is, the extent to which the program may pro-vide a model for relationships between men and women regardless ofwhether they are heterosexual, homosexual, or bisexual). Following a closereading, he concludes that Roseanne encapsulates an enigma: “The recog-nition that the shape of another kind of oppression may be similar to yourown, indeed may be a function of your oppression, seems an encouraginglyheterosocial understanding. Yet at the very moment of this awareness, wesee that this heterosocial knowledge is twisted through the axis of itsempathy so that it repositions Roseanne herself as inversely privileged: shebecomes even more oppressed.”39

Shortly before the “lesbian kiss” episode was due to air, Roseanne and TomArnold announced that the couple were involved in a menage-à-trois withtheir 24-year old assistant, Kim Silva. Their three-way “marriage” announce-ment generated a great deal of publicity at a time when—according to TomArnold—the network was considering pulling the plug on the televisedkiss. In an article in Vanity Fair, Kevin Sissums recreates the moment thestory was unleashed in between takes of recording another episode ofRoseanne in front of a studio audience. At the time, he asked Roseannewhat she would do if Arnold really was sleeping with Kim Silva:

“I don’t know what I’d do, but I do know that I wouldn’t continue to be inthe relationship.”

“So this three-way-marriage publicity stunt is all a hoax in order to havea little fun with the tabloid press?”

“Of course. I’m tired of people making such a huge deal out of this.”40

“FUCK ‘EM IF THEY CAN’T TAKE A JOKE!” 135

pal-mock-05.qxd 4/27/07 2:40 PM Page 135

Roseanne, however, refuses to disown her bisexuality. When Sissums asksher whether, considering her early history with lesbian fans, she had everhad sex with other women, she answers:

I didn’t have sex with none of them cow dykes and pool players, no. . . . But,yes, I have done that. . . . The way I think about it is that anybody can havesex with anything. You’re the one that’s sexual. The person you’re having itwith doesn’t do anything to make you one way or the other. You’re the sexualperson. If you want to go over there and have sex with that lamppost, youcan do that too.41

Roseanne also is proud of her attendance at drag balls, which she, interest-ingly, mentions in the context of blackface. Just as modern blackface per-formance makes fun of white people, she says, drag queens are “making funof men.” Her drag name is CeCe Fallopia.

Roseanne’s celebrity is founded on what has been called her “super-realness.” The strength of her talent as a comedian, as well the bond withher audience, is based on her life prior to becoming a performer: at the ageof 25, she was a “trailer mom” married to an alcoholic with three childrenunder four and also a compulsive eater: “So when she trudges into her sit-com world, amid the washing-up and unmade beds, we, the viewers, knowshe’s been there for real.”42 Roseanne’s staged “realness,” however, hasalways been a contestable site, hybrid and fragmented, and this is stressedin early analyses of her work. Siân Mile points out that by the time the pub-lic knew Roseanne as a housewife, she no longer was one. “Even thoughBarr says this character ‘is me,’ the real location of Barr’s subjectivity haschanged. The ‘real’ Roseanne is now a comic/actress/‘celebrity’; the televi-sion other is a fictional projection. . . . She has un-become her traditionalrole.”43 Philip Auslander notes that even before Roseanne hit the airwaves,her first national vehicle, The Roseanne Barr Show (1987), was a “generichybrid,” a combination of stand-up presented in a domestic environmentand situation comedy. She “represents and thematizes containment in herwork by encasing her stand-up act in a sort of triple Pirandellian frame”;Roseanne the housewife is at home with her “real” family (played byactors), encasing a performance of Roseanne in a trailer home with her fic-tional family, encasing Roseanne the comic on a stage that is dressed like asuburban living room.44

This strategy parallels the construction of womanhood represented bythe show’s fictional sponsor: “Fem-rage, for the one time of the monthyou’re allowed to be yourself.” “Real” women are many women; if you areonly “yourself” when you are menstruating, you are “not yourself” the restof the time. Five years later, in Live from Trump Castle, Roseanne elaborates

136 JEWISH WOMEN ON STAGE, FILM,AND TELEVISION / ROBERTA MOCK

pal-mock-05.qxd 4/27/07 2:40 PM Page 136

on this multiplicity: “Women are always twenty-eight women.” They alter-natively feel the urge to neurotically fold towels, eat chocolate, demand sex,and kill everybody in sight. By the end of the routine, she confesses that thecycle recurs over the period of a day, rather than the presumed month. By1994, this woman who represents Woman had claimed that she has “metmany people who share her body” and lists seventeen of her multiple per-sonalities in My Lives, with gratitude “to them all for saving my life.”45 Inwhat appears to be almost a parody of hysterical consumption, she hasdevoted a room in her house to a collection of over two hundred dolls cho-sen because they each remind her of an aspect of her personality.

Not only does Roseanne represent the “real” Woman as fragmented andmultiple, but she has also come to exemplify the fragmentation and multi-plicity of “whiteness.” While it seems to be universally acknowledged thatRoseanne is white, this whiteness is almost always qualified. The cover of a1995 issue of Entertainment Weekly, for instance, featuring “The Womenof ‘Roseanne’” (Roseanne, Sara Gilbert and Laurie Metcalf), includes thesub-title “A Trio of White Chicks Sitting Around Talking Trash.”46 Thereappears to be no obvious reason why their whiteness should be emphasizedor even mentioned. The explanatory word is “trash.” There are two types ofwhiteness in America, as there always has been: middle-class whiteness(this, of course, extends to anybody who conforms to bourgeois “respectabil-ity” and signifiers of status) and a whiteness that represents lower statusand abjection. Roseanne may be a wealthy woman who no longer lives in atrailer, but she “acts” like those who do, people derogatively referred to as“white trash.”

Indeed, this combination of aspirational success and “hillbilly” sensibil-ity is one of the reasons she is considered a “real” American. In a 1990 arti-cle she wrote for the New York Times entitled “What Am I Anyway, a Zoo?”(reprinted in My Lives), Roseanne discusses all she has come to “stand for”in America. Starting as “a regular housewife,” she “stood for all the latentenergy and talent that resides in ordinary folks living ordinary lives of quietdesperation in better trailer parks everywhere”; then “for mother”; then for“the Little Guy” standing up against “the corporate greed ogres”; thenfor “fat people”; then for “social folk remedies, anti-intellectualism, anti-feminism, ex-mental hospital inmates, people who’ve cried on BarbaraWalters”; then (“or was it at the same time?” she asks) for “the many womenwho have become megalomaniacal dictators”; then for “anger at Mother,”and “the traditional American family and later, its demise.” She also saysshe “stood for sex, too: fat, sweatin’, darkly Oedipal, ground-grabbin’ sexlike the boys like it around the Midwest, below the corn belt, sex that is allsubtext”; followed by “angry womankind herself”; and finally for “the

“FUCK ‘EM IF THEY CAN’T TAKE A JOKE!” 137

pal-mock-05.qxd 4/27/07 2:40 PM Page 137

notorious and sensationalistic La Luna madness of ovulating Abzug-iennewoman run wild.”47 Significantly, Roseanne does not mention that she everstood for “Jews,” because she does not and never has. Like Freud’s Dora,Roseanne has been deracinated. The Jewess once again has become Woman.

But Roseanne has never concealed her Jewishness. In her first autobiog-raphy, she writes that she was primarily influenced by two women: herhuge Appalachian babysitter and her Lithuanian grandmother, BobbeMary: “In the end, looking back, I realize that I have molded myself afterRobbie and Bobbe, one-half Tennessee Hillbilly, and one-half JewishMatriarch.”48 The Roseanne Barr Show featured many stories about her child-hood, beginning with an explanation of “self”:“Well, I’m from Salt Lake City,Utah, and I’m Jewish so that’s why I’m like this.” Auslander, who analyzesthis particular performance in some depth, never mentions Roseanne’sJewishness. Just as his analysis of Sandra Bernhard (discussed in the fol-lowing chapter) only focuses on her postmodernism, Roseanne is read interms of undifferentiated womanness. In both cases, however, the per-formances which come to represent totalizing (and ironically) “universal”positions are informed and enabled by specific displays of performativity.

Roseanne’s is the voice of a not-quite-white, not-quite-heterosexual,unnaturally “real,” multiple, hysterical, masculine, all-consuming womanfashioned through consumption. She herself is very aware of the power ofher difference:

When I realized the powers that the press was giving to everything I did, justbecause I was a big, scary, fat woman—and also a big, scary, fat, Jewishwoman, I was like everythin’ that fuckin’ everybody feared—I said, my God,I’m gonna be able to work it even more for women. And that’s why I talkabout everything that I talk about. It wasn’t to, like the press said, to boostmy ratings. It was because, shit, if I got the spotlight, then let’s bring it allfuckin’ down.49

Auslander and Miles both apply Hélène Cixous’s seminal essay,“The Laughof the Medusa” to Roseanne’s comedy. This is entirely appropriate. She“blazes her trail in the symbolic” and “cannot fail to make of it the chaos-mos of the “personal”; her subversive feminine text brings about anupheaval of the masculine order “in order to smash everything, to shatterthe framework of institutions, to blow up the law, to break up the ‘truth’with laughter.”50

At the end of the opening credits of every episode of Roseanne, her“real” laughter bleeds into the performance text. Roseanne “writes with herbody”; her voice wrecks “regulations and codes.” It “cuts through” and gets“beyond the ultimate reserve-discourse, including the one that laughs at

138 JEWISH WOMEN ON STAGE, FILM,AND TELEVISION / ROBERTA MOCK

pal-mock-05.qxd 4/27/07 2:40 PM Page 138

the very idea of pronouncing the word ‘silence’” (256). Its bisexuality, itsheterogeneity, its multiplicity, and its abjection signify the recuperated andpowerful voice of the hysteric. Cixous called for women to refuse to represstheir drives and desires: “a desire to live self from within, a desire for theswollen belly, for language, for blood” (261), just like the “admirable hys-terics.” She identifies her modern model Medusa explicitly: “You, Dora,you the indomitable, the poetic body, you are the true ‘mistress’ of the sig-nifier” (257). Cixous, a Jew like Freud, deracinates Dora, makes this Jewessrepresent all the force and potential of Woman.

Closing her act at The Comedy Store in 1985 (and many subsequentperformances), Roseanne commented,“You know, sometimes people comeup to me after the show and say, ‘Gosh, Roseanne, you’re not very femi-nine.’ And I say to them, ‘Suck my dick!’” For Auslander, this claim to havea penis thematizes the “inequity of a politics that equates possession of apenis with the symbolic authority of the phallus.” He sees this as evidenceof the laugh of the Medusa, a humor that usurps traditional male preroga-tive through strategies advocated by Cixous.51 I would simply add that thestereotype of the hybrid Jewess has always possessed an imaginary penisand that it was phallically used by many of Roseanne’s female Jewish pred-ecessors in the field of entertainment.52 This contradictory signifier of thecomplex interarticulation of race, sexuality, gender, and class is paradoxi-cally what has allowed her to speak for Woman.

It is perhaps not unrelated that, while Roseanne’s Jewishness has beenvirtually ignored—or at least unmentioned—by dominant cultural critics(some of whom have certainly been Jewish), the Jewish community itselfhas hardly leapt forward to embrace Roseanne as one of its own. This isremarkable in itself, since Jews are traditionally very quick to identify and“claim” other Jews, as if the achievements of one person represent theachievements of the entire community.53 However, I have rarely heardRoseanne being described by a Jew as both “funny” and “Jewish” in thesame breath, and this is due to expectations about the ways sex, sexuality,and gender relate to race, class, and national identity. If, as Mary Brewer hasshown, there is a “movement personality” for feminism (that is, a dominantideology that assumes a white, affluent, educated and heterosexual perspec-tive, often inadvertently serving to perpetuate racial, class-based, and sexualheirarchies within the category of “Woman”),54 it can also be said that thereis a similar movement personality for American Judaism. This personality,as we have seen, is either (at least) middle-class or aspires to be.

Most Jews would recognize Roseanne as what Auslander (among manyothers) has called a “matriarchal comic,” albeit an angry one.55 Given thevariety of models of motherhood provided by Jewish female performers

“FUCK ‘EM IF THEY CAN’T TAKE A JOKE!” 139

pal-mock-05.qxd 4/27/07 2:40 PM Page 139

(both on and off stage, although, as we have established, these personae areintimately related), it comes as a surprise that she should especially alien-ate Jewish audiences for this particular reason. The problem is that Roseannehas always refused to identify her motherhood as middle-class, and this ismost evident even in her early stand-up routines (captured on the 1987Roseanne Barr Show for HBO). While presenting herself as fundamentallychild-centered (although she is ignoring them to perform to an audience ina labyrinth of staged “realities”), she is unsentimental (“When my husbandcomes home at night, if those kids are still alive, hey, I’ve done my job”);she refuses to make displays of self-sacrifice (“My kids love me cuz I’mlike the mom they never had”); she doesn’t believe in gentle, manneredapproaches to child-rearing (“They say you should never hit your childrenin anger. Like when would be a good time to hit them?”). Roseanne’s per-sonae, both the character she developed from stand-up to sitcom and herpublic performances of “self,” are defiantly working-class, and the AmericanJewish community would rather see this as a assimilative stage it has passedthrough. When Roseanne wins the lottery in the last series of the sitcom(by which time most people would agree the program had “jumped theshark,” or passed its prime), the family is presented as gauche hillbilliesrather than as people who understand the value of consumption toenhance social status. Roseanne, quite simply, refuses to conform to pat-terns of Jewish identity in twentieth-century America.

This, to some extent, may be an intentional strategy, mirroring the wayshe refused to conform to expectations of the domesticated woman. Beinga Jew surrounded by Mormons (the “Nazi Amish” as Roseanne calls themin her act) was only one reason for her isolation as a child in Salt Lake City.Roseanne’s sister Geraldine describes the family’s ostracization by the city’ssmall Jewish community:

Part of it had to do with the fact that our father was a struggling salesman ina community where, if you had to be Jewish, you were expected to be rich.In a synagogue parking lot filled with Mercedeses, Lincolns, and Cadillacs,our old Chevy stood out like a sore thumb. Our family thought that suchan obvious display of poverty was viewed by our fellow parishioners as beingonly slightly less sinful than being kicked out of the Garden of Eden forovereating. We were raised to feel shame for our family’s lack of money.We felt it was perhaps the ultimate blasphemy in Salt Lake City, assuringthat Rosey and I, along with our younger siblings, would never be fullyaccepted.56

Just as Roseanne was determined to give voice to women who have beensilenced in and by mainstream entertainment, she may have been equallymotivated to present herself as the type of Jew (not to mention Jewish

140 JEWISH WOMEN ON STAGE, FILM,AND TELEVISION / ROBERTA MOCK

pal-mock-05.qxd 4/27/07 2:40 PM Page 140

woman) hidden by mainstream Judaism. There is a theory that membersof minority groups may (perhaps inadvertently) collaborate with theprocess of suppressing alternative voices within them due to the phenom-enon of “surplus visibility.” To avoid drawing attention to themselves, theytry to lead minority members into invisibility.57

This theory was outlined by Susan Kray in an article about the lack ofJewish women in television sitcoms. Although most academic books andarticles about Jewish women and Jewish popular culture exclude Roseanne,Kray is the most explicit about why when she states that “Roseanne Arnold,who says she is half-Jewish, plays energetic, emotional, humourous white-Protestant Roseanne Connor [sic].”58 It is an extraordinary comment andnot simply because it is untrue (Roseanne has always talked about herJewishness; her character on the sitcom is half-Jewish). Kray is actuallyimplying that Roseanne couldn’t be Jewish and that we shouldn’t believeher when she says she is. However, in her article she also states that to beJewish means not being “white,” an argument I have been developingthroughout this study although, as I have pointed out, Roseanne’s white-ness is not without complications.

Many cultural commentators, especially at the height of Roseanne’spopularity in the early 1990s, compared it to 1950s sitcoms like FatherKnows Best and Leave It To Beaver, which presented domesticated middle-class families with complacent housewife mothers. A more apt comparisonwould be The Goldbergs, which began as a radio serial in 1930 and ended in1955 as a television sitcom broadcast three times a week. The show wasconceived by a Jewish woman, Gertrude Berg, who not only starred in it (asMolly Goldberg) but also wrote all 4500 scripts. She was probably the firstwoman to write, produce, and star in her own television vehicle (and therecertainly haven’t been many others since). This long-running story about aJewish family in the process of “Americanization” was sentimental, cozy,nostalgic, and hugely popular. At first, the dialogue was heavily accented(“You know, Jake,” says Molly in an episode titled “Sammy’s Bar Mitzvah”which aired in 1930, “Ull de pipple vhat goes arount saying dat in life ismore troubbles den plezzure is ull wrong—I tink so”) and the Goldbergsobserved Jewish holidays on air; by 1955, when the show was known sim-ply as Molly, religious practice was largely erased, and the family movedfrom the Bronx to the suburb of “Haverville”—the “village of the haves”as one critic has pointed out.59 Although they were still coded culturally asJewish, the specifics of the Goldbergs’ ethnicity were, according to Bial,“unmarked and unremarked upon”; theirs came to represent the genericexperiences of immigrant aspiration and acculturation.60 Furthermore,when Berg made public appearances, her “self” image was very differentfrom that of her character Molly. She had no accent and wore mink coats;

“FUCK ‘EM IF THEY CAN’T TAKE A JOKE!” 141

pal-mock-05.qxd 4/27/07 2:40 PM Page 141

when the sitcom ended, she marketed her own stylish clothing range (for“rounder” women).

If Roseanne’s star text is examined closely enough, she can superficiallybe seen as performing the same patterns as many other performers whohave not been rejected by the Jewish community. She admits to engaging inprostitution between early comedy gigs to support her family, but theneven the exemplary “serious actress” Sarah Bernhardt was actively involvedin a courtesan culture at the start of her career. Roseanne left her childrenfor long periods of time and was only reunited with her first daughtereighteen years after putting her up for adoption; but, as we have seen,neglecting one’s children in pursuit of a career was not particularly unusualand could be compensated for within other frameworks. Her house may befull of gaudy kitsch, but she also wears expensive designer clothes (some-thing which is often ignored, since the media has always preferred to pres-ent Roseanne as an unfashionable slob). In fact, the following quote couldhave practically come out of the mouth of Totie Fields twenty years earlier:

My shopping is compulsive. Eight to 10 hours a day. . . . Oh, I have a messagefor [fashion designer] Ms. Donna Karan. . . . The first thing that upset me isthat the woman is Jewish and making all these crosses. I thought it was alittle anti-Semitic. And then I heard that Ms. Karan has decided to discon-tinue her size 14. . . . I said, “How goddamn anti-Semitic can you get.” Thatjust says it all. First the crosses and then this—because there is no Jewish girlwho is below a size 14.61

Although Roseanne is a conspicuous consumer, there is an assumptionthat this is done without “taste.” Where she differs from Sophie Tucker,Totie Fields and Bette Midler is that Tucker’s and Fields’s “vulgarity” asconsumers is not seen as deliberate (it is the “unfortunate” result of trying“too hard”), and Midler’s is a construction of artifice and refers back to atradition. Many Jewish female entertainers who are broadly (and proudly)accepted by Jewish audiences are known for their loudness, their use ofprofanity, their outspokenness—and their plastic surgery. It is precisely atthis point, however, that I believe Roseanne went one step too far.

In her first autobiography, Roseanne states uncategorically: “I’m crazyabout Jews who cut off their noses, change their names, starve off theirJewish fat, and then talk about how proud they are to be Jewish.”62 By 1994,she’d had a breast reduction, a tummy tuck, a nose job, and a face-lift. This,as we have seen, is not a problem; the problem, for many Jews, resides in thereasons why she says she had cosmetic surgery. In her second autobiogra-phy (one which quite radically revises aspects of the first), she writes abouther response to her new shape:

142 JEWISH WOMEN ON STAGE, FILM,AND TELEVISION / ROBERTA MOCK

pal-mock-05.qxd 4/27/07 2:40 PM Page 142

This body, which had always been the receptacle of violence and abuse, Iabused further by inflicting tears, holes and gouges on my belly, breasts, but-tocks, thighs, everywhere unseen. This, I later learned, is not uncommonamong incest victims. . . . I feel that I have been able to reverse the years ofdamage to my physical being and my self-esteem. After forty-one years, Ifinally feel no shame or disgust looking at myself in a mirror—I am a big,round, normal-shaped woman, with scars. Sometimes I feel as if I’ve had cutaway my own self-loathing and am finding comfort in my own skin.63

In therapy, Roseanne says she had “recovered” memories of sexual, physi-cal, and emotional abuse by her parents, a claim that her family stronglydenies. She had plastic surgery so she wouldn’t see her parents when shelooked in the mirror.64

The truth of these allegations is not particularly relevant here; what isrelevant is that a public attack on the family, one which could reflect badlyon Jews, is deeply frowned upon within the Jewish community. These areconsidered private matters, to be dealt with at a local level. Schneider hascalled domestic violence “the last taboo in Jewish life.”65 In Mimi Scarf ’sstudy of battered Jewish wives, she argues that “Jews living in the Diasporahave frequently spread much propaganda about themselves in order tokeep a low profile, and as a consequence, have tended to downplay socialproblems of their own.”66 Many Jews, indeed, have come to believe inthese myths, seeing such behavior as aberrant. What Roseanne has done,through her interplay of autobiographical presentation, performativity,her inscribed body, and her staged performances, is not simply destabilizebut dismantle idealized concepts of the Jewish family both for Jews andnon-Jews.

“FUCK ‘EM IF THEY CAN’T TAKE A JOKE!” 143

pal-mock-05.qxd 4/27/07 2:40 PM Page 143

Related Documents