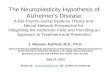

Using computers to conduct mass screening for dementia - practical issues and ethics - April 15, 2011 International Association of Geriatrics and Gerontology J. Wesson Ashford, M.D., Ph.D. Clinical Professor (affiliated) of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences Stanford University Senior Research Scientist Stanford/VA Aging Clinical Research Center, VA Palo Alto Health Care System Palo Alto, California Slides at: www.medafile.com/IAGG2011.ppt

J. Wesson Ashford, M.D., Ph.D. Clinical Professor (affiliated) of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences Stanford University Senior Research Scientist

Feb 25, 2016

Using computers to conduct mass screening for dementia - practical issues and ethics - April 15, 2011 International Association of Geriatrics and Gerontology. J. Wesson Ashford, M.D., Ph.D. Clinical Professor (affiliated) of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences Stanford University - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

Using computers to conduct mass screening for dementia

- practical issues and ethics -

April 15, 2011

International Association of Geriatrics and Gerontology

J. Wesson Ashford, M.D., Ph.D.Clinical Professor (affiliated) of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences

Stanford UniversitySenior Research Scientist

Stanford/VA Aging Clinical Research Center, VA Palo Alto Health Care System

Palo Alto, California

Slides at: www.medafile.com/IAGG2011.ppt

Two issues to be covered

• Establishing the Cost-Worthiness of dementia screening (ethical issues)

• Demonstrating a practical dementia screen

• Slides at: www.medafile.com/IAGG2011.ppt

Dementia Definition

• Multiple Cognitive Deficits:– Memory dysfunction– especially new learning, a prominent early symptom– At least one additional cognitive deficit

• aphasia, apraxia, agnosia, or executive dysfunction

• Cognitive Disturbances:– Sufficiently severe to cause impairment of occupational or social

functioning and – Must represent a decline from a previous level of functioning

AD - Dementia Continuum

NormalNormal MCIMCI ADAD

00 0.50.5 11

CDR CDR (clinical dementia rating scale)(clinical dementia rating scale)3004153-1

Estimate MMSE as a function of time

05

1015202530

-10 -8 -6 -4 -2 0 2 4 6 8 10

Estimated years into illness

MM

SE s

core

AAMI / MCI/ early AD -- DEMENTIA

Introducing the time-index model of the course of Alzheimer’s disease

Ashford et al., 1995

The best model to fit the progression,both mathematically and biologically,is the Gompertz survival curve (99.7% fit to mean changes over time):S(t) = exp(Ro/alpha *(1- exp (alpha * t)))

(calculated from the CERAD data set)

(Time-Index Scale)

Is it worth screening for memory problems or Alzheimer’s disease?

“If there was treatment for AD, I'd recommend screening, but there is no disease-modifying therapy."

Anonymous Alzheimer expert -2008

“All older adults benefit from memory screening because it detects cognitive problems before memory loss is noticeable.”

Anonymous Alzheimer expert -2008

Healthy Aging, 2008; repost, 2010“Memory Screening: Is it Worth It?”

http://healthy-aging.advanceweb.com

http://healthy-aging.advanceweb.com/Patient-Resource-Center/Disease-Management-and-Prevention/Memory-Screening-Is-it-Worth-It.aspx

Alzheimer's Disease Is Under-diagnosed

• Early AD is subtle, the diagnosis continues to be missed – It is easy for family members to avoid the problem and compensate for the

patient – Physicians tend to miss the initial signs and symptoms

• Less than half of AD patients are diagnosed– Estimates are that 25%–50% of cases remain undiagnosed– Diagnoses are missed at all levels of severity: mild, moderate, severe

• Undiagnosed AD patients often face avoidable social, financial, and medical problems

• Early diagnosis and appropriate intervention may lessen disease burden– Early treatment may substantially improve overall course

• No definitive laboratory test for diagnosing AD exists– Efforts to develop biomarkers, early recognition by brain scan

Why Memory Screening Is Important to Consider

• Cognitive impairment is disruptive to human well-being and psychosocial function

• Cognitive Impairment is potentially a prodromal condition to dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (AD)

• Dementia is a very costly condition to individuals and society (issue of who is paying for screening, patient care)

• With the aging of the population, there will be a progressive increase in the proportion of elderly individuals in the world (must consider costs to society)

• Screening will lead to better care (more cost-effective care)

No Testing: What happens without screening?

Total Population Risk=P

P

Have ADNo effective intervention

Do not have AD

P’

Helena Kraemer, 2003

Testing: What happens with testing?Total Population

No ADAD

Unnecessary intervention OK No effective intervention Effective intervention

$ Testing $Testing $ Testing $ Testing$ Intervention $ Intervention

Iatrogenic Damage? Clinical Wash Clinical Wash Clinical Gain

Major(?) Loss Minor (?) Loss Minor(?) Loss Major(?) Gain Some gain

False Positive True Negative False Negative True Positive

PP’

SeSe’

SpSp’

Helena Kraemer, 2003

Specificity = Sp Sensitivity = Se

Factors for Deciding whethera Screening Test is Cost-Effective1) Benefit of a true positive screen2) Benefit of a true negative screen3) Cost of a false positive screen4) Cost of a false negative screen5) Incidence of the disease (in population)6) Test sensitivity (in population)7) Test specificity (in population)8) Test cost

$W = Cost–Worthiness Calculation

$W > ($B x I x Se) – ($C x (1 - I) x (1 - Sp)) - $T• BENEFIT

– $B = benefit of a true positive diagnosis• Earlier diagnosis may mean proportionally greater savings• Estimate: (100 years – age ) x $1000• Save up to $50,000 (e.g., nursing home cost for 1 year)

– (after treatment cost deduction at age 50, none at age 100)– (cost-savings may vary according to your locale)

– True negative = real peace of mind (no money)• COST

– $C = cost of a false positive diagnosis• $500 for further evaluation

– (time, stress of suspecting dementia)– False negative = false peace of mind (no price)

• I = incidence (new occurrences each year, by age)• Se = sensitivity of test = True positive / I• Sp = specificity of test = True negative / (1-I) = (1-False positive/(1-I)• $T = cost of test, time to take (Subject, Tester)

Kraemer, Evaluating Medical Tests, Sage, 1992

Benefits of Early Alzheimer Diagnosis Social

• Undiagnosed AD patients face avoidable problems • social, financial

• Early education of caregivers• how to handle patient (choices, getting started)

• Advance planning while patient is competent• will, proxy, power of attorney, advance directives

• Reduce family stress and misunderstanding• caregiver burden, blame, denial

• Promote safety• driving, compliance, cooking, etc.

• Patient’s and Family’s right to know• especially about genetic risks

• Promote advocacy• for research and treatment development

Benefits of Early Alzheimer Diagnosis Medical

• Early diagnosis and treatment and appropriate intervention may:– improve overall course substantially– lessen disease burden on caregivers / society

• Specific treatments now available (anti-cholinesterases, memantine)– Improve cognition– Improve function (ADLs)– Delay conversion from Mild Cognitive Impairment to AD– Slow underlying disease process, the sooner the better– Decreased development of behavior problems– Delay nursing home placement, possibly over 20 months– Delay nursing home placement longer if started earlier

Benefits of Early Treatment ofAlzheimer’s Disease

• Neurophysiological pathways in patients with AD are still viable and are a target for treatment

• Opportunity to reduce from a higher level: – Functional decline– Cognitive decline– Caregiver burden

Need to estimate net benefit monetarily

(key factor in determining case for screening)Estimate benefit = (100 years – age ) x $1000

Estimated Age-related Benefitof Early Alzheimer Treatment

0

10000

20000

30000

40000

50000

50 60 70 80 90 100AGE (years)

Dol

lar s

avin

gs fr

om d

elay

ed n

ursi

ng

hom

e pl

acem

ent

Benefit = $10,000 - 0Benefit = $25,000 - 0Benefit = $50,000 - 0

Value of Diagnosis versus Time-Index

0%10%20%

30%40%50%60%70%

80%90%

100%

-10 -8 -6 -4 -2 0 2 4 6 8 10

Estimated years into illness(TimeIndex Scale)

Rel

ativ

e va

lue

of d

etec

tion

Value across continuumValue at transitionValue early

- Sharpness of peak relates to increased sensitivity and specificity - Location of peak relates to point in dementia continuum where recognition would be most beneficial – adjusting sensitivity versus specificity

More specificMore sensitive

Cost of False-Positive Screen

• Referral of normal individual for further testing– (more specific testing)

• Value of individual’s time• Cost of additional testing

• Estimate cost = $500 per false-positive screen

• This does not and should not include the cost of untoward results of misdiagnosis, medication side-effects, or malpractice – quality management should address these issues

Other Benefits and Costs of Screening

• Benefit of true-positive screen = intangible– Peace of mind – Plan further into future

• Cost of false-negative screen = wash– Delay in diagnosis and treatment– No different from current condition

INCIDENCE OF DEMENTIA(Hazard per year)

Based on estimate of 4 million AD patients with dementia in US in 2000, with an incidence that doubles every 5 years, illness duration of 8 years.

U.S. mortality, dementia, MCI rate by age (mortality = 2000 CDC / 2000 census)

0.0001

0.0010

0.0100

0.1000

1.0000

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Age (years)

Haz

ard

/ yea

r

Males, 2t = 8.2yrsFemales, 2t = 7.5 yrsdementia incidence, 2t = 5 yrsMCI incidence, 2t = 5yrs

JW Ashford, MD PhD, 2003; See: Raber et al., 2004 (Incidence for “a” to “a + 1” year)

The Gompertz survival curve explains 99.7% of male and female mortalityVariance between 30 and 95 y/o in US:

U(t) = Ro * exp (alpha * t)

Relative Risk Factors for Alzheimer’s Disease (after age, early onset genotypes)

• APOE-e4 genotype 1 allele x 4; 2 alleles x 16• Family history of dementia 3.5 (2.6 - 4.6)• Family history - Downs 2.7 (1.2 - 5.7)• Family history - Parkinson’s 2.4 (1.0 - 5.8)• Obese, large abdomen 3.6• Maternal age > 40 years 1.7 (1.0 - 2.9)• Head trauma (with LOC) 1.8 (1.3 - 2.7)• History of depression 1.8 (1.3 - 2.7)• History of hypothyroidism 2.3 (1.0 - 5.4)• History of severe headache 0.7 (0.5 - 1.0)• History of “statin” use 0.3• NSAID use 0.2 (0.05 – 0.83)• Use of NSAIDs, ASA, H2-blockers 0.09

Roca, 1994; ‘t Veld et al., 2001, Breitner et al., 1998, Wolozin et al., 2000

U.S. Alzheimer Incidence

(4 million / 8yr)

02000400060008000

10000120001400016000

50 60 70 80 90 100

Age

# / y

r

male=170,603

female=329,115

JW Ashford, MD PhD, 2003; See: Raber et al., 2004

Zandi et al., JAMA, November 6, 2002—Vol 288, No. 17 p.2127

Dementia rate, assume Td = 5 yrs

0.0001

0.001

0.01

0.1

1

10

100

1000

50 60 70 80 90 100

Age (years)

Haz

ard

/ yea

rmean rate

APOE 4/4 (x7.5)

APOE 3/4 (x2)

APOE 3/3 (x0.6)

Early onset (x200)

Using the Gompertz equationto model rate of dementiaincrease with age:U(t) = Ro * exp (alpha * t)

JW Ashford, MD PhD, 2003; See: Raber et al., 2004

Miech et al., 2002

Cache County, probability of incident dementiaCircles – femalesSquares - malesOpen – ApoE-e44Gray – ApoE-e4/xBlack – ApoE-ex/x

JW Ashford, MD PhD, 2000

U.S. AD Incidence by APOE(proportion of cases)

00.10.20.30.40.50.60.70.80.9

1

50 60 70 80 90 100Age

Prop

ortio

n / Y

ear 4/4

3/43/3

e4/4 – 2% of pop, 20% of casese3/4 - 20% of pop, 40% of casese3/3 - 65% of pop, 35% of cases

Cost-Worthy Test EvaluationBenefit = $50,000 - 0; False Pos = $500

-100-50

050

100150200250300350400450500550600

50 55 60 65 70 75 80 85 90 95

AGE

Cos

t Jus

tifie

d fo

r D

emen

tia S

cree

n .8, .8.9, .9.95, .951,1

Se, Sp

Cost-Worthy Test EvaluationSensitivity = 0.9, Specificity = 0.9

-$200$0

$200$400$600$800

$1,000

50 55 60 65 70 75 80 85 90 95AGE (years)

Cos

t Jus

tifie

d fo

r D

emen

tia S

cree

n

Benefit: $5,000 - 0Benefit: $10,000 - 0Benefit: $25,000 - 0Benefit: $100,000 - 0Benefit: cure = $240,000

Varying Benefit:

Cost-Worthy Dementia ScreeningSe=0.9; Sp=0.9

Benefit = $25,000 - 0; False Pos = $500

-1000

100200300400500600

50 55 60 65 70 75 80 85 90 95

AGE

Cos

t Jus

tifie

d fo

r D

emen

tia S

cree

n

meanApoE 4/4ApoE 3/4ApoE 3/3

AD all (easiest to hardest at p=.5)

00.10.20.30.40.50.60.70.80.9

1

-4 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

DISABILITY ("time-index" year units)

PRO

BAB

ILIT

Y C

ORR

ECT

PENCILAPPL-REPWATCLOCATIONPENY-REPTABL-REPCLOS-ISRIT-HANDCITYFOLD-HLFSENTENCECOUNTYNO-IFSFLOORSEASONYEARPUT-LAPMONTHADDRESSDRAW-PNTDAYSPEL_ALLDATEAPPL-MEMPENY-MEMTABL-MEM

Mini-Mental State Exam itemsMMSEitems

The Taxonomy of Long-Term Memory

(Squire and Zola, 1996)

Animals named in 30 seconds (mms>19)

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

0 5 10 15 20 25number of animals named

perc

ent o

f tot

al

Normal Controls, n=386

Mild Alzheimer Patients, n=380JW Ashford, MD PhD, 2001

Animals named in 1 min (mms>19) - CERAD data set

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

0 10 20 30 40

number of animals named

perc

ent o

f tot

al

Normal Controls, CS = 1, n = 386

Alzheimer patients, CS = 0, n = 380

Brief Alzheimer Screen (BAS)• Repeat these three words: “apple, table, penny”.• So you will remember these words, repeat them again.• What is today’s date?

• D = 1 if within 2 days.• Spell the word “WORLD” backwards

• S = 1 point for each word in correct order• “Name as many animals as you can in 30 seconds, GO!”

• A = number of animals • “What were the 3 words I asked you to repeat?” (no prompts)

• R = 1 point for each word recalled

BAS = 3 x R + 2/3 x A + 5 x D + 2 x S

Mendiondo, Ashford, Kryscio, Schmitt., J Alz Dis 5:391, 2003

www.medafile.com/bas.htm

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90Pe

rcen

t of V

alid

atio

n Sa

mpl

e

3-22 23 24 25 26 27-39

BAS Score

Mild AD

Control

JW Ashford, MD PhD, 2001

BRIEF ALZHEIMER SCREEN (Normal vs Mild AD, MMS>19)

9

20

1413

1211

10

9

6

7

8

2627

25

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100False Positive Rate (%) (1-Specificity)

True

Pos

itive

Rat

e (%

) (S

ensi

tivity

)

animals 1 m AUC = 0.868

animals 30 s AUC = 0.828

MMSE AUC = 0.965

Date+3 Rec AUC = 0.875

BAS AUC = 0.983

JW Ashford, MD PhD, 2003

Brief Alzheimer Screen (BAS) ROC for Univ. Kentucky ADRC Clinic Cases

Schmitt et al., 2006

Need for Mass Screening

• Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, and memory problems are difficult to detect when they are mild– about 90% missed early – about 25% are still missed late

• There are important accommodations and interventions that should be made when there are cognitive impairments– (like needing glasses or having driving restrictions if you have

vision problems)

Recommendations being considered for mandatory Medicare screen (April, 2011)

1) Ask patient and significant other (if available) if memory is a problem

2) Ask patient and significant other (if available) if remembering to take medications is a problem

3) Ask patient to remember 3 unrelated words, and have the patient repeat the 3 items twice

4) Ask patient the date (note if off by more than 2 days)5) Ask the patient to name as many animals as possible in 1 minute

(note concern if number is below 10)6) Ask the patient to draw a clock (note issues)7) Ask the patient to recall the 3 items that were repeated (note

concern if 2 or 3 items not recalled)8) Evaluate the clinical responses. If problems noted, consider

possible explanations or need for further evaluation

There is considerable resistance to implementation of clinical screening

1) Clinicians are concerned that they don’t have time to screen

2) Certain organizations recommend use of warning signs, which have not been studied or ever shown to be effective for recognizing early cases

3) There needs to be a technique for easy recognition of memory problems in an at-risk individual

4) Audience memory screening is available5) Memory tests are available on the WEB6) Computerized testing is more effective and efficient

Issues for Memory Screening• Memory (neuroplasticity) is the fundamental deficit of

Alzheimer’s disease

• Current testing for memory problems is based on having a tester sit in front of a subject for a prolonged period of time and administer unpleasant tests

• Testing must be – Inexpensive (minimal need for administrator)– Fun (so people will return for frequent testing)– More precise, reliable, and valid

• To improve sensitivity• To improve specificity

Audience Screening: CONTINUOUS RECOGNITION TEST

• Presentation of complex pictures (that are easily remembered normally) are useful for detecting memory difficulties

• Testing memory using a pictures approach needs standardization for population use

• Picture memory is less affected by education• Picture memory can be tested by computer• Audiences can be shown slide presentations

Answer Sheet for Memory Screening (back of sheet)Carefully look at each picture. If you see a picture that you have seen before, mark the circle next to the number of the repeat picture. For the main test, you will see 50 pictures. Each picture is numbered. The pictures will stay on the screen for 5 seconds. 25 pictures are new, 25 pictures are repeated.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

THE END

Please note the number on your answer sheet, then hand it in.

MEMTRAX Memory Test

116 subjects – mostly elderly normals, some young, some dementia patientsFalse positive errors (false recognition) – 33(64);6(58);47(27)—4,18,23,34(1);1,2,8(0)False negative errors (failure to recognize) – 35(33);27(20);5(16)—32(4);24(3);45(3)

1 2 3 4 6 7 8 13 14 15 17 18 19 22 23 25 28 29 33 34 36 37 41 44 470

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

# fa

lse

posi

tives

/116

sub

ject

s249 - False Positive Responses for Each Slide, by Slide Number Order(116 subjects voluntarily participating at local informational talks)

242 - False Positive Responses by Slide Number, by Number of Errors(116 subjects voluntarily participating at local informational talks)

33 6 47 36 13 22 44 25 41 19 14 28 37 7 15 17 29 2 4 18 23 34 8 1 20

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

# fa

lse

posi

tives

/116

sub

ject

s

5 9 10 11 12 16 20 21 24 26 27 30 31 32 35 38 39 40 42 43 45 46 48 49 500

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

249 - False Negative Responses for Each Slide, by Slide Number Order(116 subjects voluntarily participating at local informational talks)

35 27 5 12 16 9 10 31 43 46 11 30 20 21 42 48 40 49 26 38 39 50 32 24 450

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

# fa

lse

nega

tive/

116

subj

ects

249 - False Negative Responses for Each Slide, by Number of Errors(116 subjects voluntarily participating at local informational talks)

Performance in 116 subjects

0

5

10

15

20

25

0 5 10 15 20 25

Number False negative

Num

ber

Fals

e po

sitiv

e

Probable Normal

? fronto-temporaldementia? MCI

? dementia

RandomPerformanceRegression

Test Performancefor 1018 subjects

• 82 (8%) had perfect scores,82 (8%) had perfect scores,• 230 (23%) made 1 error (98% correct), 230 (23%) made 1 error (98% correct), • 700 (69%) made 5 or fewer errors (700 (69%) made 5 or fewer errors (>>90% correct),90% correct),• 132 (13%) made 6 – 10 errors (80 – 88% correct),132 (13%) made 6 – 10 errors (80 – 88% correct),• 186 (18%) made > 10 errors (<80% correct).186 (18%) made > 10 errors (<80% correct).----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------• 70 (7%) scored < 80% correct for True Negatives70 (7%) scored < 80% correct for True Negatives

– 19 (6%) males, 51 (8%) females 19 (6%) males, 51 (8%) females • (false positive responses = saying a picture is repeated when not),(false positive responses = saying a picture is repeated when not),

• 79 (8%) scored < 80% correct for True Positives79 (8%) scored < 80% correct for True Positives– 25 (7%) males, 54 (8%) females 25 (7%) males, 54 (8%) females

• (false negative responses = failure to recognize/recall repeat picture)(false negative responses = failure to recognize/recall repeat picture)

True Negative Performance

y = -0.0352x + 25.564R2 = 0.039

y = -0.0597x + 27.24R2 = 0.141

1213141516171819202122232425

40.0 50.0 60.0 70.0 80.0 90.0 100.0

Age (years)

Num

ber C

orre

ct

Male true-

Female true-

Linear (Male true-)

Linear (Female true-)

True Positive Performance

y = -0.0438x + 27.029R2 = 0.0617

y = -0.0418x + 26.746R2 = 0.0605

1213141516171819202122232425

40.0 50.0 60.0 70.0 80.0 90.0 100.0

Age (years)

Num

ber C

orre

ct

Male true+

Female true+

Linear (Male true+)

Linear (Female true+)

False Positives (incorrect guesses)

y = -0.0935x + 3.7674R2 = 0.0153

y = -0.021x + 2.5605R2 = 0.0007

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20

Education (years)

Num

ber W

rong

Male False+

Female False+

Linear (Male False+)

Linear (Female False+)

False Negatives (memory failures)

y = -0.0042x + 1.4457R2 = 3E-05

y = -0.0398x + 1.255R2 = 0.02

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20

Education (years)

Num

ber W

rong

Male False-

Female False-

Linear (Male False-)

Linear (Female False-)

The relationship between discriminability (d ) and age ′on the audience-based continuous recognition test of memory for 868 individuals with all information.

The relationship between discriminability performance (d ) and age in 868 individuals on ′the continuous recognition test of memory.

The relationship between discriminability performance (d ) and age in 868 individuals on ′the continuous recognition test of memory.

The relationship between discriminability index (d ) and education in 868 individuals on the ′continuous recognition test of memory.

*

The relationship between the number of intervening items (between initial and first repeat presentations) and percent correct on those items on the continuous recognition test of memory.

The relationship between percent correct and item repetition in 868 individuals on the continuous recognition test of memory.

WEB-based ScreeningOn-line Testing

• Same test paradigm as Audience Screening• Testing can be faster – 1-2 minutes for 50 image• Many different variations of the test can be given• Other aspects of cognition can be tested• Test can be repeated several times to decrease variance• Test can be taken over time to detect changes• Improved anonymity to protect private information

MEMTRAX - Memory Test(to detect AD onset)

• New test to screen patients for AD: – World-Wide Web – based testing– CD-distribution– KIOSK administration (grocery stores, drug stores)

• Determine level of ability / impairment• Test takes 2 to 3 minutes• Test can be repeated often (e.g., weekly, quarterly)• Any change over time can be detected

MemTrax WEB Testing• Blueberry Study

– 12 subjects – no health problems reported

– Mean age = 49.3 + 11.7 (range 31-68)

– 2 weeks of testing (5 days each week)

– 11 different tests

– 14 to 18 administrations per subject

d' by Test #

0.0000

0.5000

1.0000

1.5000

2.0000

2.5000

3.0000

3.5000

4.0000

4.5000

0 2 4 6 8 10 12

Test #

d'

d' by Agey = 0.0076x + 2.8553R2 = 0.0219

0.0000

0.5000

1.0000

1.5000

2.0000

2.5000

3.0000

3.5000

4.0000

4.5000

30 35 40 45 50 55 60 65 70

Age

d'

d' by Test Ordery = -0.0067x + 3.2933R2 = 0.0032

0.0000

0.5000

1.0000

1.5000

2.0000

2.5000

3.0000

3.5000

4.0000

4.5000

0 5 10 15 20 25

test order #

d'

Reaction Time by Test #

0

200

400

600

800

1000

1200

0 2 4 6 8 10 12

Test #

Corr

ect r

eacti

on ti

mes

Reaction Time by Agey = 1.3554x + 622.79R2 = 0.0276

0

200

400

600

800

1000

1200

30 35 40 45 50 55 60 65 70

Age

Corr

ect r

eacti

on ti

mes

Reaction Time by Test Order y = -0.4084x + 693.39R2 = 0.0005

0

200

400

600

800

1000

1200

0 5 10 15 20 25

test order #

Corr

ect r

eacti

on ti

mes

Gender Age d' d' Tot BetaBeta Total

Memtrax RT

Faces RT O-HAP

Gender -

Age -0.20 -

d' 0.01 -0.14 -

d' Total 0.26 -0.38 0.88 -

Beta 0.61 -0.43 0.18 0.52 -

Beta Total 0.61 -0.53 0.33 0.67 0.98 -

Memtrax RT -0.42 0.29 -0.31 -0.55 -0.67 -0.66 -

Faces RT -0.23 0.26 -0.59 -0.78 -0.73 -0.74 0.75 -

Offline HAP 0.76 -0.57 0.05 0.32 0.78 0.77 -0.70 -0.47 -

Vis-Accom 0.55 -0.72 0.01 0.19 0.17 0.28 -0.10 0.16 0.57

Correlation coefficient with n-2 (9 for 11 subjects) degrees of freedom is: significant at p < .10 level with a value of at least 0.521, p < .05 at 0.602, and p < .01 at 0.735.

Correlations significant at the .10, .05 and .01 level are shown in red, blue, and green type respectively.

BlueBerry Study – MemTrax – correlation analyses

Reaction Time as a Function of Hearing y = -1.4941x + 870.94R2 = 0.3873

500.0

550.0

600.0

650.0

700.0

750.0

800.0

850.0

900.0

950.0

1000.0

20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160 180

Offline HAP

Cor

rect

Rea

ctio

n Ti

me

(mse

cs)

Conclusions• The ethical concerns of values and harms must be estimated as costs

and benefits• Incidence, costs, and test accuracy each play a role in determining

whether screening is justified• Calculations show that screening for memory problems is justified

under specific circumstances, age, and risks• Memory can be measured in mass settings using an audience- based

system or web administration over the internet• The remaining question is whether health systems are prepared to

provide the care that will improve the lives of those affected• In the future, the incidence is climbing, so the problem may be much

worse. Will future treatments be better? • Legislation is needed to require training of clinicians to properly

diagnose, treat, and manage dementia patients and for mandating appropriate reimbursements of clinicians for their work

• Screening tests are ready for widespread implementation

Screening Tests Available On-Line• www.memtrax.com (clinical)• www.memtrax.net (research)• www.medafile.com (information)• Slides at:

–www.medafile.com/IAGG2011.ppt

• For further information, contact:– Wes Ashford: [email protected]

Future directions for screening• Successful prevention of dementia, AD• APOE genotyping – routine at birth

– Preventive measures based on genetics • Can amyloid preprotein dysfunction be controlled

by diet, mental stimulation (education), physical exercises, better sleep, drugs, to prevent AD?

• Longitudinal assessment of memory– To treat dementia when not prevented

• Computer games to monitor/improve cognition– Quick, fun, inexpensive, user-friendly, repeated

Related Documents