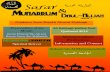

GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE ON ISLAMIC BANKING & INSURANCE ISSUE NO. 173 OCTOBER–DECEMBER 2009 SHAWWAL–DHU AL HIJJAH 1430 WAQF: ALLEVIATING POVERTY FINANCIAL CRISIS: LESSONS FOR ISLAMIC FINANCE IT FOCUS: ARAB BANK ANALYSIS: MUSHARAKAH MUTANAQISAH IIBI CAMBRIDGE WORKSHOP REVIEW PUBLISHED SINCE 1991

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE ON ISLAMIC BANKING & INSURANCE

ISSUE NO. 173OCTOBER–DECEMBER 2009

SHAWWAL–DHU AL HIJJAH 1430

WAQF: ALLEVIATING POVERTY

FINANCIAL CRISIS: LESSONS FOR ISLAMIC FINANCE

IT FOCUS: ARAB BANK

ANALYSIS: MUSHARAKAH MUTANAQISAH

IIBI CAMBRIDGE WORKSHOP REVIEW

PUBLISHED SINCE 1991

46 Shari’ah and legal issues of musharakah mutanaqisah

Adam Ng Boon Ka, PhD candidate at the International Centre for Education in Islamic Finance, Malaysia, takes a close look at this type of financing.

www.newhorizon-islamicbanking.com IIBI 3

NEWHORIZON Shawwal–Dhu Al Hijjah 1430

Features

Regulars

12 Recent crisis: lessons for Islamic finance

Leading financial hubs are increasingly looking towardIslamic finance as a new type of banking that will promote lasting stability. NewHorizon examines thevaluable lessons the Islamic finance industry shouldlearn from the recent financial turmoil.

18 Horses for courses

There is no doubt thattechnology is vital for any financial institutionnowadays, whether conventional or Islamic.NewHorizon talks to Andrew Cobb, chief proj-ects officer at Arab Bank, about the bank’s first-handexperience in implementing Islamic banking softwareacross its international locations.

40 Would Islamic finance have prevented the global financial crisis?

Mohammed Amin, UK head of Islamic finance at PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP,addresses the question on everyone’s lips.

24 Waqf and zakat: alleviating poverty How can Shari’ah-compliant finance mechanisms assist in the burning issue of alleviating poverty? In thefirst of a two-part analysis, NewHorizon focuses onwaqf.

CONTENTS

London conference, ‘Managing Shari’ah Risk through Shari’ah Governance’.

38 DIARYUpcoming Islamic finance events endorsed by the IIBI.

45 RATINGS & INDICESCredit ratings of Islamic financial institutions and instruments by Capital Intelligence (CI).

50 GLOSSARY

IIBI and ISRA sign MoU. IIBI and SII join forces to promote the UK as Islamic finance hub.More students complete the IIBI’s Post Graduate Diploma course.

30 IIBI LECTURESJuly and August lectures reviewed.

34 IIBI EVENTS REVIEWReviews of the Cambridge workshop,‘Structuring Innovative Islamic Financial Products’, and the

04 EXECUTIVE EDITOR’S NOTE

05 NEWSA round-up of the important stories from the last quarter around the globe.

16 APPOINTMENTSA summary of appointments within the Islamic finance industry.

20 IIBI NEWSIIBI, GK Partners and the British Library hold the UK’s first Access to Islamic Finance (A2IF) conference.

24

46

18

www.newhorizon-islamicbanking.com

NEWHORIZON October–December 2009

Executive Editor’s Note

On behalf of the staff at the IIBI and NewHorizon I would like towish all our readers Eid Mubarak.

The month of Ramadan has special significance for Muslims theworld over. ‘The month of Ramadan is the month in which was sent down the Quran, as a guide to mankind, also clear (Signs) for guidance and judgement (between right and wrong).’ (TheQuran 2:185). It is a time for deep devotion and reflection on thewisdom and guidance that comes with faith. It brings the spirit ofgiving and sharing to the fore. US President Barack Obama in hisRamadan message this year reminded us that fasting is shared bymany faiths as a way to bring people closer to God and to thoseamong us who cannot take their next meal for granted, and for all of us to remember that the world we want to build and thechanges we want to make must begin in our own hearts and in our own communities.

NewHorizon ponders how Islamic finance mechanisms can be applied to a long-term strategy of poverty alleviation. To begin with, we focus on waqf, followed by an in-depth analysis of zakat in the next issue of the magazine. Would Islamic finance have prevented the crisis? What lessons should be learned from recentevents? Eminent Islamic finance specialists attempt to answer thesepertinent questions.

Together with GK partners (advisers to socially responsible business)and the British Library, the IIBI held the UK’s first Access to IslamicFinance (A2IF) conference. The Institute’s third annual residentialworkshop on structuring innovative Islamic financial products, heldin August in Cambridge, was also a success. Furthermore, the IIBIhas signed a memorandum of understanding with the InternationalShari’ah Research Academy for Islamic Finance (ISRA), and anagreement with the Securities and Investment Institute (SII), a Lon-don-based professional body for those working in the financial andinvestment industry, to promote the UK as an Islamic finance hub.

As always, I hope that you will find this issue of the magazine interesting, informative and thought-provoking.

Mohammad Ali QayyumDirector General IIBI

EDITORIAL

EXECUTIVE EDITORMohammad Ali Qayyum,Director General, IIBI

EDITORTanya Andreasyan

IIBI EDITORMohammad Shafique

CONTRIBUTING EDITORJames Ling

NEWS EDITORLawrence Freeborn

IIBI EDITORIAL ADVISORY PANELMohammed AminRichard T de BelderAjmal BhattyStella CoxDr Humayon Dar Iqbal KhanDr Imran Ashraf Usmani

DESIGN CONSULTANTEmily Brown

PUBLISHED BY IBS Publishing Ltd8 Stade StreetHythe, Kent, CT21 6BEUnited KingdomTel: +44 (0) 1303 262 636Fax: +44 (0) 1303 262 646Email: [email protected]: www.ibspublishing.com

CONTACTAdvertisingIBS Publishing LtdPaul MinisterAdvertising ManagerTel: +44 (0) 1303 263 527Fax: +44 (0) 1303 262 646Email: [email protected]

SUBSCRIPTION IBS Publishing Limited8 Stade Street, Hythe, Kent, CT21 6BE, United KingdomTel: +44 (0) 1303 262 636Fax: +44 (0) 1303 262 646Email: [email protected]: newhorizon-islamicbanking.com

©Institute of Islamic Banking and InsuranceISSN 0955-095X

Cover photo: © Amanda Rihde,iStockphoto.com

Deal not unjustly,and ye shall not be dealt with unjustly.

Surat Al Baqara, Holy Quran

This magazine is published to provide information on developments in Islamic finance, and not to provide professional advice. The views expressed in thearticles are those of the authors alone and should not be attributed to the organisations they are associated with or their management. Any errors andomissions are the sole responsibility of the authors. The Publishers, Editors and Contributors accept no responsibility to any person who acts, or refrainsfrom acting, based upon any material published in the magazine. The Editorial Advisory Panel exists to provide general advice to the editors regardingmatters that may be of interest to readers. All decisions regarding the published content of the magazine are the sole responsibility of the Editors, and theEditorial Advisory Panel accepts no responsibility for the content.

4 IIBI

www.newhorizon-islamicbanking.com IIBI 5

NEWHORIZON Shawwal–Dhu Al Hijjah 1430

The Accounting and AuditingOrganisation for Islamic Finan-cial Institutions (AAOIFI) hasannounced its intention to mon-itor Islamic financial products inthe absence of a sector watch-dog. AAOIFI stated it plans to‘screen products and services of-fered by the industry for Shar-i’ah compliance’. According toMohamad Nedal Alchaar, secre-tary general of the organisation,the move would help to ‘ho-mogenise the market’.

‘Although AAOIFI is not takingon a permanent role of industrywatchdog, there exists a currenthuge gap in the market relating

to credible Shari’ah compliancescreening of products and serv-ices,’ stated Alchaar.

Currently, the Islamic financialindustry must rely on differentstandard-setting bodies, such asAAOIFI in Bahrain and the In-ternational Financial ServicesBoard (IFSB) in Malaysia, whichrecently issued new governanceand capital adequacy guidelines(NewHorizon, April–June2009). The guidance of individ-ual, qualified Shari’ah scholarsalso plays an important role, asdo national governments incountries which practice Islamicfinance.

An example of the difficultiesfacing the industry came withcomments from Shaikh Muham-mad Taqi Usmani, head of theShari’ah committee of AAOIFI,pronounced in February 2008that many sukuk issues up tothat point were not Shari’ah-compliant. This resulted in asharp drop in new issues ofsukuk, despite having doubledevery year since 2004(NewHorizon, October–December 2008).

As well as preparing accounting,governance, ethics and Shari’ahstandards for Islamic bankingand financial institutions,

AAOIFI to perform temporary watchdog role

AAOIFI already provides prod-uct and auditing standardswhich are mandatory in sevencountries across the Islamicworld (Dubai, Bahrain, Jordan,Lebanon, Qatar, Syria andSudan). Alchaar stated thatAAOIFI wants to screen prod-ucts of all institutions, not justthose which are members ofAAOIFI, and not just those inthe seven countries listed. ‘It willbe market-wide, regardless ofthe geographic distribution ofproducts,’ he said.

AAOFI plans to submit a pro-posal to this effect to its boardof trustees by the end of 2009.

Thailand’s Ministry of Inte-rior has told governmentagencies and state-owned or-ganisations to provide techni-cal, management and financialsupport to encourage Islamicmicrofinance in the country.The proposal by the Ministryhas received cabinet support.It will result in knowledge oftransactions, accountancy andwelfare arrangements accord-ing to Shari’ah being passedon to staff in the sector by theagencies and organisations in-volved. Social welfare andother benefits, in terms of ed-ucation, social services andthe environment, will also beprovided for members of Is-lamic microcredit plans.

According to the Ministry ofInterior, the Southern BorderProvinces Administrative Cen-

tre had appointed aworking group to studywhat form and model ofIslamic microcreditwould be most appropri-ate. The population ofthis region is predomi-nantly Muslim, and theMinistry’s objective isthat communities in thearea have access to finan-cial institutions whichoperate in accordancewith their own lifestyleand religious beliefs.

The working group’sstudy demonstrated thatmost villagers were keento see the establishmentof Shari’ah-compliant micro-finance in their communities,although they still lacked un-derstanding of financialmechanisms used in the in-

Thailand’s government supports Islamic microfinance

NEWS

dustry. Once the workinggroup submitted its study, inMay 2009, the administrativecentre then made its proposalon Shari’ah-compliant microfi-

nance to the government. Muslims are the second largestreligious group in Thailand,numbering approximately twomillion.

Pattani Mosque,Thailand

© Jean-Yves Benedeyt, iStockphoto.com

6 IIBI www.newhorizon-islamicbanking.com

NEWHORIZON October–December 2009

Malaysia’s central bank andregulator, Bank NegaraMalaysia (BNM), has issued itsmurabaha parameter, the firstin a series of Shari’ah parame-ters to Islamic financial institu-tions in the country. These areissued as guidance and refer-ence to promote greater har-monisation in the developmentof the Islamic finance industryin the Malaysia.

This initiative aims to definethe essential features of Shar-i’ah-compliant financial prod-ucts and services based onexisting contracts that havebeen endorsed by Shari’ahboards and used by Islamic in-

time as it would unlock thehuge potential of the domestic market. He believed that theagreement could improve theinnovation level of depositproducts.

‘The adoption of the CMMAfor corporate deposits is ex-pected to result in cost and resource savings for both Is-lamic banks and corpora-tions,’ said Zukri at thelaunch. Takaful Malaysia,ACR Retakaful, Astro, Mae-sat and the Employees Provi-dent Fund have all signed amemorandum of understand-ing (MoU) to participate inthe CMMA.

Bank Negara Malaysia issues first Shari’ah parameter

stitutions. The parameters willact as standard documents forunderstanding the principlesand basis for adopting Shari’ahcontracts.

The murabaha parameter out-lines the main Shari’ah require-ments in the contracts andprovides examples, methods andmodels for practical applicationof this mode of financing. It willalso contribute to further har-monisation in the interpretationand application of Shari’ahviews and opinions among Shar-i’ah committee members.

To ensure the robustness of theparameter, BNM has conducted

extensive research and compiledvarious fatwas in addition to theviews of several local and inter-national Shari’ah boards.

Further parameters are currentlybeing developed, including ijara,mudarabah, musharakah, is-tisna and al-wadia.

Meanwhile, the Association ofIslamic Banking InstitutionsMalaysia (AIBIM) has launcheda Corporate Murabaha MasterAgreement (CMMA), with theintention of boosting the work-ings of the Islamic money mar-ket in the country. AIBIM’spresident, Datuk Zukri Samat,said the launch came at a good

NEWS

First fully Islamic bank to open in India

The first Indian bank to dealonly in Islamic financial prod-ucts is to open in Kochi, in thesouth western Indian state ofKerala, early next year. The Ker-ala State Industrial DevelopmentCorporation has initiated thecompany with an authorisedcapital of over $100 million.The company is expected to in-vest mainly in infrastructureprojects and pay dividends todepositors, and the state govern-ment is looking into which prod-ucts to finance with the bank.

P. Mohammed Ali of Oman’sGalfar Group, C.K. Menon ofDoha-based Behzad Group,M.A. Yusuf Ali who heads theLuLu supermarket chain in theGulf, and Azad Moopen ofMoopen’s Group are said to be

the company’s major promot-ers. The state government saidthat the outfit will first oper-ate as a non-banking financecompany before becoming afully Shari’ah-compliant bank.

There are approximately 150million Muslims in India,making the Indian Muslimpopulation the third largest inthe world (after Indonesia andPakistan). Senior politiciansand officials in India, such asAmar Singh, general secretaryof India’s Socialist party, havein recent times spoken infavour of Islamic finance inthe country. The push in Kerala is supported by the regional government headedby state finance minister DrThomas Isaac, who believes

that Islamicfinance op-tions will helpexpatriateswho return toIndia havinglost their jobsas a result ofthe global recession.

It will appar-ently also setup a separatesocial fundfor financing interest-free loansfor Gulf returnees (Indianswho had previously worked inthe GCC) to start small-scaleventures. Isaac was recentlyquoted as saying that hewanted GCC members to con-tribute to the fund. The gov-

ernment had formed a promot-ers group, including business-man Mohammed Ali, who wasquoted as explaining that ‘Is-lamic banking doesn’t work oninterest. It invests deposits inbusiness and returns a share ofits profit to depositors.’

New Dehli,India

8 IIBI www.newhorizon-islamicbanking.com

NEWHORIZON October–December 2009NEWS

A number of Islamic financialinstitutions around the worldare celebrating the holy monthof Ramadan by stepping uptheir charitable operations. Cor-porate social responsibility(CSR) is an important year-round consideration, but thistime represents a valuable op-portunity to double charitabledeeds and strengthen relationswith the community.

In Malaysia, Maybank has setup a fund, Tabung Maybank Se-jahtera, to assist the creation ofsustainable living environmentsfor vulnerable communities inthe country regardless of race,religion or creed. Members ofthe public are able to donate tothis fund via all of the bank’sdelivery channels.

For the second successive yearSaudi Arabian bank, SABB, issponsoring orphans to performUmrah during Ramadan. Thebank is covering the expenses of300 boys and girls to performthe pilgrimage through its par-ticipation in the Umrah Pro-gramme organised by Riyadh

Orphan Care Charitable Soci-ety, Ensan.

Shamil Bank, an Islamic com-mercial bank in Bahrain, ishelping two children in theKingdom regain their ability tohear with the purchase of twosophisticated cochlear implanthearing aids. The bank has pre-sented the hearing aids to theBahraini Society forCochlear Implanta-tion and Hearing Im-pairment (right). Theywill then be passed on to the CochlearImplantation team of the country’s Min-istry of Health for implantation to twochildren on the waiting list.

The Indian Islamic Associationand Qatar International IslamicBank have partnered to trans-late three Arabic religiousbooks into Malayalam to helpcreate awareness of Islam in theIndian community in Qatar.The books are: ‘The CompletePrayer’ by Sheikh Abdullah Jar-

Ramadan inspires CSR in Islamic banks

allah al-Jarallah; ‘This Is What Life Has Taught Me’ byMustafa al-Sibaai and ‘Compre-hensiveness of Islam’ by SheikhYousef al-Qaradawi. The bookshave been printed in India andare being distributed amongMalayalam speakers in Qatarfor free. A number have alsobeen sent to educational estab-lishments and public libraries in

the Indian state of Kerala.Meanwhile in Malaysia, Taka-ful Ikhlas, a provider of Shar-i’ah-compliant insurance, hasbrought joy to a score of poorchildren in the Petaling Jaya dis-trict of Selangor, by treatingthem to a day of Hari Raya(Eid) shopping followed by adinner to break their fast. The

day out was organised by Taka-ful Ikhlas in conjunction withthe Petaling Jaya branch of theSelangor Tithe Board.

The children, aged between fiveand 17, were accompanied to a shopping complex in BukitTinggi, Klang, where the takafulfirm paid for the purchase of all their clothes and shoes, be-fore picking up the tab for aniftar dinner. Takaful Ikhlas alsomade a donation to nine furtherchildren, who were unable to attend.

‘The children got to know ourstaff, who could be like fosterbrothers and sisters to them,’said chief operating officer and executive vice president of Takaful Ikhlas, Wan MohdFadzlullah.

While Takaful Ikhlas has em-braced the social side of Islamicfinance for Ramadan, it doeshave a track record of makingcharitable donations. In July2009, it donated a dialysis ma-chine to the Mersing DistrictHospital in Johor.

Pakistan-based MeezanBank has signed a memoran-dum of understanding(MoU) with internationalnon-governmental organisa-tion (NGO), Islamic Relief.

Under the terms of theMoU, Meezan will assist Is-lamic Relief to further en-

hance its Shari’ah-compliantmicrofinance operations in thecountry by capacity building,training and product develop-ment support.

Islamic Relief has been offer-ing Shari’ah-compliant micro-credit facilities around theworld for a number of years,

Meezan Bank partners with Islamic Relief

and in Pakistan since 2001. Itgives out loans through a non-interest bearing mudarabah financing strategy. Once se-lected for loan eligibility, bene-ficiaries are provided thedesired working capital oncredit. Repayments are made in instalments over the periodof one year.

Islamic Relief has several on-going projects in Pakistan,such as a small enterprise development programme inpartnership with HSBC thatoffers halal lending to femaleentrepreneurs. To date, thisproject has helped 388women in the Rawalpindidistrict in Punjab.

www.newhorizon-islamicbanking.com IIBI 9

NEWHORIZON Shawwal–Dhu Al Hijjah 1430 NEWS

The Turkish operation ofKuwait Finance House (KFH),known as Baytak, has received alicence from the Federal Finan-cial Supervisory Authority ofGermany to establish a Shar-i’ah-compliant financial servicesbranch in the country. Thebranch will be headquartered inMannheim, in the south westernGerman state of Baden-Würt-temberg. Mohammed Al-Omar,chairman of Baytak, stated thatthis is a significant step in thegeographical expansion strategyof the bank. He added that it islikely to open more branches inGermany, and also apply for li-cences to operate in other Euro-pean countries.

Turks are the second largest eth-

nic group in Germany, whileMuslims in the country accountfor 3.7 per cent of the popula-tion. Saxony-Anhalt, anotherfederal state of Germany, hasthe distinction of issuing theonly sovereign sukuk in westernEurope (NewHorizon, January– March 2009), showing thatthere is an interest in Islamicbanking that KFH will be ableto target.

KFH has over 100 branches in Turkey, as well as offices inother countries including re-cently established representationin Kazakhstan. Other parts ofKFH have also continued togrow, for example in Kuwait,where another five branches are due to open.

Gulf Finance House (GFH),the Middle Eastern Islamic investment bank, plans tofound a joint Islamic financialservices platform in the Mid-dle East with MacquarieGroup Limited, the Australia-listed global bank. The plat-form will focus on providingShari’ah-compliant financialservices on the wholesale side for the Middle East andNorth Africa. The two partiessigned a memorandum of un-derstanding at a ceremony inBahrain.

The partnership, whichawaits approval, will see ajoint presence based in the re-

gion and an investment byMacquarie in GFH of around$100 million in the form of aconvertible murabaha, as partof GFH’s current capital man-agement initiatives. An execu-tive of GFH stated that the pairplan to have the platform upand running by the beginningof 2010. The agreement willenable GFH to structure Mac-quarie’s existing products to beShari’ah-compliant, while al-lowing GFH access to Mac-quarie’s global advisory servicesand trading links, and helpingit expand geographically.

Meanwhile, the agreement sig-nals Macquarie’s interest in the

GFH and Macquarie enter into wholesale Islamic finance JV

Middle Eastern region, as wellas in Shari’ah-compliant finance.

John Wright, group COO ofGFH, suggested that part of therationale for the joint venturewas to help the bank diversifyaway from its core business ofinfrastructure and real estate fi-nancing, which currently standsat around 65 per cent of its busi-ness. Wright indicated that GFHaims to reduce this down toabout 20 per cent. It also re-cently signalled its intention toraise up to $300 million of freshcapital, which is to help it ex-pand the activities and geogra-phies it covers, as well asstrengthen its balance sheet.

Meanwhile, the involvementof Macquarie reflects a wider interest from Australiain Islamic finance – The Muslim Community Co-op-erative (Australia) recently received a financial services license from the Australian Securities and InvestmentsCommission (ASIC)(NewHorizon, April–July2009), and has sincelaunched the first AustralianShari’ah-compliant invest-ment fund. It is believed to be the first ASIC registeredretail managed investmentmortgage fund directed primarily to Islamic invest-ments.

Kuwait Finance House eyes up Germany

T’azur, a takaful firm head-quartered in Bahrain, haslaunched what it claims to bethe world’s first Shari’ah-compliant charitable insur-ance product, called the‘Sadaqah’ plan.

The plan helps donors saveregular contributions whichT’azur invests over a setnumber of years in Shari’ah-compliant funds. Accumu-lated capital is then passedon to the donor’s charity ofchoice. T’azur will continueto make payments on behalfof the donor if unforeseenevents (such as an illness)force the donor to stop pay-ing them. These donationswill be made through taka-ful, thereby ensuring that thecharity chosen by the donor

receives the intended amountno matter what happens.

Dr Abdulaziz Bin Naif AlOrayer, chairman of theboard of T’azur, said: ‘Thisplan embodies the essence oftakaful, namely mutual helpand assistance for the com-mon good, and demonstratesour commitment to charitiesand all communities inBahrain.’

Nikolaus Frei, T’azur’s chiefexecutive officer, added: ‘TheSadaqah plan is to our knowl-edge the world’s first insuredcharitable savings plan.’ Thisinnovation, in his view, is an affirmation of Bahrain’s position as a leading financialservices hub in the MiddleEast.

New charity takaful scheme

10 IIBI www.newhorizon-islamicbanking.com

NEWS NEWHORIZON October–December 2009

Despite, or perhaps because of,the strong headwinds in theconventional international fi-nancial markets, the world’slargest fully-fledged Islamicbanks have continued to growstrongly, according to statisticsfrom Asian Banker Research,the consultancy division of TheAsian Banker. The hundredlargest Islamic banks’ assetsgrew to $580 billion in 2008,up from $350 billion the previ-ous year (a 66 per cent rise).

Compared to the previous year,the identities of the largestbanks remained fairly constant,with Bank Melli of Iran at thetop of the list and Al-RajhiBank, headquartered in SaudiArabia, in second place. Indeed,seven out of the top ten institu-tions are Iranian, and the twelveIranian banks in the list account

for 40 per cent of the top 100banks’ assets. Four other coun-tries, Malaysia, the UAE, SaudiArabia and Kuwait, accountedfor most of the rest of the wealthof the top 100 banks, in roughlyequal proportion to each other.

Some have questioned whetherthe Iranian institutions should beincluded, since their treatment ofriba (interest) appears to be dif-ferent from other Islamic financemarkets. Likewise, the reportshows that, while Iranian banksare often very large by assets,they are not necessarily the mostprofitable. Al-Rajhi Bank had thehighest net income at $1.74 bil-lion, with the next highest, Ku-wait Finance House, just under$1 billion. In terms of asset size,the study suggested that BankMelli may lose its top spot, sinceit did not grow in 2008.

Largest Islamic banks’ assetscontinue to grow

As the Islamic finance industrycontinues to modernise the tech-nology which underpins it, anumber of banks have recentlytaken the decision to upgradetheir core banking systems.

Among these are two Sudanesebanks, United Capital Bank(UCB) and Bank of Khartoum(BOK). Both have chosen to im-plement the iMAL core bankingsystem of Kuwait-based PathSolutions, which was recentlycertified by the Accounting andAuditing Organisation for Is-lamic Financial Institutions

(AAOIFI) as Shari’ah-compliant(NewHorizon, January–March2009).

BOK is a universal financial in-stitution, while UCB focuses oncorporate banking. UCB lookedat four international core bank-ing system offerings beforechoosing iMAL, which thebank’s IT manager, AbdelrazagMustafa Abdelrazag, describesas a ‘pure Islamic system’. Headds that ‘Path Solutions hasgood knowledge of Islamicbanking itself, which is reflectedin the solution’. The project at

Islamic banks make core system decisions

UCB includes about ten modulesof the product, and will lastuntil March 2010. Among thebenefits UCB will see will be aneasing of the process of openingnew branches. ‘The system is de-signed in a way that when weopen a new branch we can dothat with minimum effort.’

Among other banks who haverecently been active in upgrad-ing their IT, Abu Dhabi IslamicBank in Egypt has gone livewith a new Shari’ah-compliantbanking system from Interna-tional Turnkey Systems (ITS),

while First East Export Bank inMalaysia, a subsidiary of Iran-based Bank Mellat, also tookiMAL from Path Solutions.

Path Solutions itself has recentlyclaimed to be nearing the com-pletion of a rewrite of its corebanking system in Java, with allmodules to be completed andcommercially available by theend of 2009. Around 35 of thecompany’s staff have been work-ing on the project, and existingusers of iMAL will be able toupgrade over a period of threeyears or so.

The secretary general of thezakat fund of the UAE, Ab-dullah Bin Aqeeda AlMuhairi, has rowed back onsuggestions made last year(NewHorizon, July – Septem-ber 2008) that the collectionand distribution of zakatshould be made mandatoryfor all UAE citizens whoseincome surpassed a certainthreshold. According to theseplans, local Islamic financialinstitutions and companieswould have had to pay 2.5per cent of their net operat-ing capital to the fund fromthe beginning of 2009, witheight Islamic banks includedamong those that would haveto make payments.

Al Muhairi had wanted toamend the fund’s bylaws to

make it mandatory to submitaudited accounts and pay therequired share, the purposebeing to streamline the processof distribution. However, thegovernment of the UAE lastyear rejected the fund’s pro-posal for new legislation,which would have mandatedthat individuals earning over athreshold make an annual pay-ment. Al Muhairi has now ad-mitted that the payment ofzakat will remain discretional‘for the time being’, for bothcompanies and individuals.

‘What we have to do now israise awareness of how volun-tary payment can benefit us asa society,’ Al Muhairi said. TheUAE’s zakat fund has grownfrom its inception in 2004 tobe worth over $12 million.

Alms to remain voluntary in UAE

12 IIBI www.newhorizon-islamicbanking.com

NEWHORIZON October–December 2009

crisis. New regulations often engenderedregulatory arbitrage where these regulationswere evaded by financial innovations. Leg-islative gaps were also a factor in sustainingweak or outdated regulatory framework.Additionally, ideologically driven deregula-tion exacerbated efforts at forging an effec-tive regulatory framework that couldpromote stability. The frequency and magni-tude of banking crises with significant ad-verse consequences for income andemployment both over time and acrosscountries has led many thinkers to concludethat the conventional financial system con-tains seeds of inherent instability. The the-ory of inherent instability of theconventional interest-based, debt-dominatedfinancial system has been expounded uponat least since the late eighteenth and earlynineteenth centuries. One of the most eru-dite advocates of the inherent instability hy-pothesis was an American economist,Hyman Minsky (1996) who, beginning inthe second half of the last century, notedthat the stability of such a system, if andwhen achieved, could not be sustained. Thiswas because conventional finance was des-tined to evolve from stability created by eq-uity-dominated financial transactions byfirms, which he called hedge finance, to in-stability created by interest-debt-dominatedfinancing, which he called speculative andPonzi finance. Such instability would hardlybe a surprise when we recall Verse 2, 276 inthe Quran which unequivocally declaresthat riba-based debt transactions havewithin them the seeds of their own destruc-tion. Instability would be unavoidable when

Inherent instability of the conventional financial system

The conventional financial system, based oninterest and debt contracts, has been shakenby frequent crises with varying intensityover the centuries in almost every countrywhere it has operated. Both advanced andpoor countries have suffered major bankingcrises; some devastating. Each crisis re-quired a government guarantee of depositsand bank bailouts, without which the conta-gious effect would have led to total failureof the banking system with severe conse-quences for the real economy. The role ofthe central bank as a lender of last resortwas stressed by a prominent British econo-mist and journalist, Walter Bagehot (1873). Deposit insurance was introduced in 1935in response to massive losses of depositsthat occurred in each crisis. Each bankingcrisis has had dramatic effect on economicgrowth and employment and caused an eco-nomic recession or depression.

Financial crises have occurred in spite of theexistence of regulatory and supervisoryframeworks, including Basel I and II regula-tions. Each crisis called for more regulationand supervision. Such was the case for PeelAct in 1844 in the United Kingdom, the es-tablishment of the US Federal Reserve Sys-tem (Fed) in 1913, and the RooseveltAdministration banking regulations in1935. At times, new regulations becamesources of new instability. For instance, theFed was a key contributing factor in theGreat Depression and in the recent financial

Recent crisis: lessons for Islamic financeAbbas Mirakhor, former executive director at the International Monetary Fund (IMF), andNoureddine Krichene, economist at the IMF and former advisor at the Islamic DevelopmentBank in Jeddah, examine the valuable lessons that the recent financial turmoil can teach theIslamic finance industry.

ANALYSIS

To promote Islamic banking,there is a priority to develop theregulatory and supervisoryframework and demonstratethe strength and resilience ofIslamic banks.

www.newhorizon-islamicbanking.com IIBI 13

NEWHORIZON Shawwal–Dhu Al Hijjah 1430 ANALYSIS

those who resort to riba-based transactionscall forth a declaration of a direct war fromAllah (s.w.t) and His Messenger PBUH(Quran, Verse 2, 279).

During the Great Depression, a number ofscholars, especially those economists associ-ated with the Department of Economics ofthe University of Chicago, offered a pro-posal to the Government of the USA for thereform of the financial system. The crux ofthe Chicago Reform Plan corresponds to alarge degree to the core of the financial sys-tem that emerges from Islamic teachings.The Reform proposed a two-tier bankingsystem: (i) 100 per cent reserve banking thatwould preclude money creation and destruc-tion by the banking system, which wouldconsequently fully protect deposits and thenation's payments system; and (ii) a regu-lated investment banking system withoutgovernment protection such as a depositguarantee system of insurance. The Islamicfinance version converts the second tier intoan equity-based system in which interest-based debt transactions are prohibited. The-oretical analyses of such a system havedemonstrated its inherent stability. This con-clusion stems from the fact that no maturitymismatching is possible since there is a 100per cent money reserve system in place andbecause any asset-side price inflation or de-flation is mapped one-to-one onto the liabil-ity side of the balance sheet of the financialinstitution.

Causes of conventional finance instability

Economic literature has analysed at greatlength the causes of financial instability. Asearly as the beginning of the nineteenth cen-tury, English economist, banker and philan-thropist Henry Thornton (1802) observedcostless paper money creation by the centralbank and banks and explained a bankingcrisis essentially as the result of two factors:(i) deviation of the market interest rate froma non-observed natural interest rate whichmeasures the rate of profit or marginal pro-ductivity of capital in the economy; and (ii)consequent multiple expansion and contrac-tion of the deposit base of the banks intocredit. If the market interest rate is belowthe natural rate, demand for credit expands.

Banks have no difficulty issuing loans inmultiples of their deposits and capital, in-cluding fictitious credit that has no depositbackup in the form of promissory notes.Asset and commodity prices rise. Monetisa-tion of government deficits causes abundantliquidity, depresses money interest rates, and leads to credit expansion. When the in-verted credit pyramid becomes too over-leveraged, i.e. unsustainable, in relation toreal economy, or to the tax base, govern-ments, entrepreneurs, and consumers facedifficulties in servicing their debt. A rapidcontraction of credit ensues, asset and com-modity prices fall steeply, and a massivebank failure occurs.

Thornton’s two interest rates theory waselaborated by many writers. Among thesewas the re-examination of the quantity the-ory of money (1898) by Johan Gustaf KnutWicksell, a renowned Swedish economist.He argued that deviations of the moneymarket interest rates from the natural inter-est rates set forth changes in money velocity,as well as in the quantity of money, leadingin turn to changes in the price level as wellas in real economic activity. Observing theGreat Depression unfold, American econo-mist Irving Fisher (1933) ruled out all possi-ble causes except over-indebtedness arisingfrom cheap money followed by debt defla-tion as the single cause of financial crises.He firmly concluded that financial crises canbe explained only by excessive expansion ofcredit and grave financial and economic dis-orders that follow such expansion, includingmoney and credit contraction, falling prices,bankruptcies, and massive unemployment.

The recent financial crisis which broke outin August 2007 could be explained by thesame factors repeatedly mentioned in the lit-erature, namely interest and over-indebted-ness. Financialisation has drasticallyweakened the link between the financial andreal sectors, allowing for the inverted creditpyramid to reach a leverage ratio in relationto real GDP that might have exceeded amultiple of 50. Mirakhor (2002) noted thealarming growth of the inverted credit pyra-mid in relation to real GDP and determinedthat financialisation had nearly severed therelationship between finance and produc-

tion. He stated that for each dollar worth ofproduction there are thousands of dollars ofdebt claims, and predicted the imminent col-lapse of such a credit pyramid.

The chart indicates that the crisis was pre-ceded by a long period of record low inter-est rates and largely negative real interestrates forced by the US Fed and over-abun-dant liquidity that fuelled excessive specula-tion in asset and commodity markets. TheUS war financing and excessive externalcurrent account deficits that ranged betweenfive and seven per cent during 2002/07 haveallowed dollar deposits of foreign centralbanks at US banks to increase considerablyand fuel more liquidity and lending in theUS markets. Over-abundant liquidity couldnot be absorbed by prime markets. Finan-cialisation, which encompasses securitisa-tion of assets and credit derivatives, pushedfloods of liquidity into sub-prime marketsand fuelled housing and commodity bub-bles. The ratio of credit has risen to an un-precedented level in relation to GDP, whichled to difficulties in servicing such credit.Households were not able to pay the specu-lative prices and speculative gains as well asthe high salaries of debt merchants. Thesebecome a burden on households. Foreclo-sures have transferred all the burden tobanks that suffered large losses and had tobe bailed out with trillions of dollars bygovernments.

Major reserve banks have become a danger-ous destabilising force and a powerful taxa-tion and wealth redistribution agency. Muchfinancial wealth, in the form of stocks, hasbeen wiped out. No financial system nomatter how perfectly regulated could sur-vive cheap money policy in the form of ex-cessively low interest rates and abundantliquidity. Although the credit to GDP ratiohas been at its highest level ever, centralbanks have been reckless in pushing moresub prime debt by injecting trillions of dol-lars in liquidity at near-zero interest ratesthat has been amassed in excess reserves andhas only fuelled speculation in commodityand exchange markets. By depressing inter-est rates and printing unlimited money, cen-tral banks are only paving the ground for aneven more powerful financial crisis, creating

14 IIBI www.newhorizon-islamicbanking.com

NEWHORIZON October–December 2009ANALYSIS

considerable distortions, and imposing pro-hibitive taxation on workers and fixed in-come pensioners.

Islamic finance is inherently stable

Logically, there can be little doubt that a fi-nancial system that derives its operatingprinciples from the Quran and the Sunnahwill be inherently stable. In such a system,banks do not contract interest bearing loansand do not create and destroy money. Theydo not finance speculation, nor do they en-gage in debt trading. Although lending isnot prohibited in Islam, it has to be free ofany element that can be considered as inter-est. Interest-based lending cannot be part ofIslamic economic activity. Such lending andborrowing redistribute wealth when thereare wide price fluctuations and thereforecannot be part of Islamic finance that isbased on justice. Lending can increase thewealth of borrowers in undeserved ways atthe expense of workers and low-incomeclasses. Besides causing inflation when it ex-ceeds savings, it can fuel speculation. More-over, borrowers always shift the risk tolenders. They repay interest and principalonly when their projects are profitable.When projects instead make losses, borrow-ers default, resulting in the deterioration ofbank portfolios.

Mirakhor (1988) defined an Islamic finan-cial system as one in which there are norisk-free assets and where all financialarrangements are based on risk and profitand loss sharing. Hence all financial assetsare contingent claims and there are no debtinstruments with fixed or floating interestrates. Modelling the financial system asnon-speculative equity shares, he showedthat the rate of return to financial assets isprimarily determined by the return in thereal sector, and therefore in a growingeconomy, Islamic banks will always experi-ence net positive returns. Mirakhor notedthe absence of an inverted credit pyramidand showed that there is a one-to-onemapping between the real and financialsector. Because the interest rate is absent,there is no discrepancy between interestand profit rates, and hence the economyalways operates at full employment equi-librium. More specifically, underemploy-ment equilibrium (devised by Britisheconomist John Maynard Keynes), basedon pivotal role of interest rate, liquiditytrap and deficient demand, is inapplicableto Islamic finance.

Conceptually, an Islamic banking systemcan have two basic types of banking activi-ties: first, a safekeeping and payments ac-tivity as in the pre-Islam and early Islam

periods and also as in goldsmith houses,and the second are investment activities.The first type of activity is similar to the100 per cent reserve system, with depositsremaining highly liquid and checking services fully available. This system has to be a fee-based system to cover the costof safekeeping, transfers and paymentsservices.

The second activity, investment activity, iswhere deposits are considered as longer-term savings and banks engage directly inrisk taking in trade, leasing, and produc-tive investment in agriculture, industry,and services. The most important charac-teristic of this activity is that it is immuneto un-backed expansion of credit. An Is-lamic bank is assumed to match depositmaturities with investment maturities.Short-term deposits may finance short-term trade operations, with the bank pur-chasing merchandise or raw materials andselling to other companies; liquidity is re-plenished as proceeds from sales opera-tions are generated. For longer-terminvestment, longer-term deposits are used.Liquidity is replenished as amortizationfunds become available. It can also be re-plenished through stock market transac-tions by selling and buying shares.

In all these cases, an Islamic bank is a di-rect owner of the investment. In such asystem, a financial institution participatesdirectly in the evaluation, managementand monitoring of the investment process.Returns to invested funds arise ex-postfrom the profits or losses of the operation,and are distributed to depositors as if theywere shareholders of equity capital. Sinceloan default is absent, depositors face asmall risk of loss of their assets. In con-ventional finance, loan default is perva-sive, and the rate of default increases morethan proportionally relative to the rate ofcredit expansion. Furthermore, the higherthe share of consumer loans the higher therisk of default. Credit default can becomea systemic risk and degenerate into abanking crisis. Without government guar-antee, depositors face a significant risk oflosing their deposits. Such risk does notexist in Islamic finance.

Key Interest Rates2000M1 – 2009M5

www.newhorizon-islamicbanking.com IIBI 15

NEWHORIZON Shawwal–Dhu Al Hijjah 1430 ANALYSIS

Lessons for Islamic finance

The recent financial crisis has brought Is-lamic finance to the centre stage. Leadingfinancial places are looking toward Is-lamic finance as a new type of bankingthat will promote lasting stability anddurable growth of production, trade, andemployment. To promote Islamic bank-ing, there is a priority to develop the regu-latory and supervisory framework anddemonstrate the strength and resilience ofIslamic banks. The establishment of a uni-versal regulatory framework and diffu-sion of knowledge about Islamic bankingwould help attract investors and business-men to this field.

The regulatory and supervisory frame-work of conventional finance cannot re-move the two fundamental causes ofbanking instability namely: interest anddebt. Islamic finance is theoretically in-herently stable as these two fundamentalcauses do not exist in Islamic finance.However, practitioners admit that Islamicfinance as it is practiced at this stage can-not be distinguished from conventional fi-nance. Financialisation is proceeding atthe same rate as in conventional finance.There is evidence that failed Islamic bankswere simply conducting conventionalbanking and were plagued by the samecauses that made conventional banksfragile and prone to failure.

Regulators have to agree on a definitionof Islamic finance. Our view is that such asystem has to be a two component sys-tem: a 100 per cent reserve componentand an equity investment component. Thetwo functions should be mandated to sep-arate institutions; a legislative-regulatoryfirewall must keep the two separate. Theinvestment component can undertake fi-nancial transactions stemming from con-tractual modes of financing such asmudarabah, murabaha, ijara and istisna.More broadly, it has to be an equity-based component. Where and whenneeded, non-interest debt financing canfacilitate transactions that are notamenable to equity participation. Regula-tors have to set guidelines for ensuring the

soundness and viability of the investmentcomponent through up to date risk analysisand compliance with Shari’ah principles.

The promulgation of a theoretical regula-tory framework that represents a consensus-driven definition of Islamic finance wouldenable people to determine deviations ofpracticing institutions from pure Islamic fi-nance and the degree of their compliancewith Shari’ah principles. Currently, Islamicfinancial institutions operate in differentregulatory jurisdictions and under differentschools of jurisprudence that have varyingunderstandings of Islamic banking. The ex-istence of a universal regulatory frameworkwould allow the measurement of cross-country differences.

Only banks licensed by central banks shouldbe allowed to practice Islamic banking. Thiswould prevent swindles and schemes thatrob consumers under the cover of Islamicbanking. Many types of financial transac-tions and instruments should be excludedfrom Islamic finance, particularly interestrate-based bonds, and securities often dis-guised as collateralised instruments thatmake them more expensive than those is-sued under the conventional system. Addi-tionally, excluded from Islamic transactionsare finance based on securitisation of ficti-tious assets, speculative finance, hedgefunds, and consumer finance that is notbacked by real assets. In all of this type offinance, either the acquired assets are finan-cial papers, or loans that have no real back-ing, and do not contribute to generating realactivity, income, and employment. In partic-ular, conventional consumer loans, besides

being expensive for consumers, have a high default risk, and do not generate newwealth. Financial innovations such as se-curitisation, originate and distribute mod-els, and many instruments that lead tospeculation or to fictitious assets, cannotexist in an Islamic system. Attempts bybanks to issue their own money and liabil-ities, beyond full asset-liability matching,would be strictly prohibited. Supervisionshould be tightly conducted to ensure fullcompliance with Islamic banking princi-ples. Violations should carry prohibitivepenalties.

The resilience of many Islamic banks tothe Asian as well as the recent financialcrises has shown the inherent stability ofthese institutions. Such resilience would befurther enhanced through issuing universalregulatory and supervisory guidelines forIslamic finance and putting in place an ef-fective reference framework that measurescompliance with true Islamic banking andaims at eliminating serious credit and in-terest rate risks that may compromise depositors’ savings and undermine thesafety of Islamic banks. Such an edifice ofunified and universal regulatory-supervi-sory framework is becoming increasinglyurgent lest the failure of a few more osten-sibly Islamic financial institutions and in-struments lead to reputational damagethat would be more destructive to Islamicfinance than in the case of the conven-tional system. Whereas in the conventionalsystem, the failure of a few institutionscannot threaten the entire system, damageto the reputation of Islamic finance is apronounced systemic risk.

Many types of financial transactions and instruments shouldbe excluded from Islamic finance, particularly interest rate-based bonds, and securities often disguised as collateralisedinstruments that make them more expensive than thoseissued under the conventional system.

16 IIBI www.newhorizon-islamicbanking.com

NEWHORIZON October–December 2009

On the move

APPOINTMENTS

HSBC Middle East has appointed DavidHunt as head of insurance for the region.Hunt will oversee all HSBC insurancebusiness in the Middle East, includingEgypt and Saudi Arabia. He will also beresponsible for the provision of insuranceproducts and services for all of the bank’spersonal and commercial customers in-cluding the development of its Shari’ah-compliant takaful business. Hunt movesfrom SABB Takaful Company in SaudiArabia, which is an associate company ofSABB and HSBC.

Ithmaar Bank, the Bahraini outfit whosesubsidiaries include the Shari’ah-compli-ant universal bank, Shamil Bank, inBahrain, has appointed Mohamed Hus-sain as chief executive officer. Hussain hasbeen co-CEO since April 2008, and takesover from Michael P Lee. Prior to his ap-pointment at Ithmaar last year, Hussainwas an executive and board member atthe bank.

Dow Jones Indexes, which produces theDow Jones Islamic Market World Index,has announced the appointment of TariqAl-Rifai as its new director of Islamic in-dexes. He will be charged with workingwith clients to develop new business op-portunities, developing new Shari’ah-com-pliant indexes and working with moneymanagers and investors. Al-Rifai will alsobe the contact point between Dow Jones’board of Islamic scholars and its mainte-nance, research and development teams.

Al-Rifai is a veteran of 13 years in Islamicfinance. He founded Failaka Advisors in1996 to develop and promote Shari’ah-compliant financial instruments. He hassince served as vice president of Islamicbanking at HSBC, and was a partner inThe International Investor, a Kuwaitishareholding company. Since 2004, he hasbeen vice president of UIB Capital.

Ali bin Za’al Al Mansouri has replaced DrAbdul Latif Al Shamsi as chairman of UAE-based Methaq Takaful Insurance Company,after the latter resigned at the end of July.Samer Mohammed Kanan has also beenelected as managing director. Kanan willmanage the company’s administrative staffand represent Methaq legally and financially.

Abu Dhabi IslamicBank (ADIB) has re-cently made a spate ofnew appointments.Malik Sarwar has beennamed global wealthmanagement executiveto target high networth and affluentclients with Shari’ah-compliant products.Dhafer Faroq Lugman has been named headof strategy, product management and inter-national retail banking. Lugman will be responsible for planning and directing allbusiness development strategies, includingthe tapping of new geographies. Mrs NawalAl Bayari (above) has been appointed vicepresident and business head for ladies bank-ing, in a role to ensure the development of new products and services for female customers.

Sarwar has worked in the US, Asia and theMiddle East in a career which spans numer-ous posts, including at Permal Group, Citi-group and Merrill Lynch. He worked at thelatter for 17 years, in sales and businessroles, primarily in global wealth manage-ment. Before moving to ADIB, he was headof US business for Permal, an independentfund of hedge funds.

Lugman has 19 years of experience, mostlywith HSBC and Dubai Islamic Bank (DIB) inthe Saudi and UAE markets. He finished hiscareer at HSBC as country manager for retailin the UAE. He previously spent twelve yearsin Saudi Arabia in the corporate and retailbanking divisions. While at DIB, he was

head of corporate development and a boardmember of two of its subsidiaries.

Mrs Al Bayari boasts considerable experi-ence at international banks including Bar-clays, Standard Chartered Bank, AmericanExpress and DIB. She joins ADIB from Bar-clays, where she spent two years overseeingbusiness coordination in over 15 countriesacross MENA, Africa, Asia and Eastern Eu-rope. While at DIB, she was relationshipmanager and acting head of private bankingfor ladies. Her spell at Standard CharteredBank was as business support manager foroffshore accounts in the international bank-ing wealth management division.

Kuwait’s Securities House is to bring to-gether its two UK-listed subsidiaries, Gate-house Bank (a fully fledged Islamic bank)and GSH UK (a Shari’ah-compliant finan-cial services firm), into one organisationunder the Gatehouse Bank brand, resultingin a number of senior management changes.Fahed Faisal Boodai has been appointedchairman of Gatehhouse Bank, and RichardThomas will become CEO, stepping downfrom his former roles as non-executivechairman of Gatehouse Bank and managingdirector of GSH. He is to replace DavidTesta, who is leaving the group. Thomashas worked in merchant and investmentbanking for 29 years, the last 25 of whichhave been in Islamic banking. He hasworked for Saudi International Bank,United Bank of Kuwait and Arab BankingCorporation, helping each set up Islamicbanking operations.

Rohail Ali Khan has become deputy CEOof Pak-Qatar General Takaful, a Pakistan-based Islamic insurance company. Khan hasover 15 years of senior management experi-ence in the Islamic finance sector, with pre-vious senior roles at Adamjee Insurance,Pak-Kuwait Takaful Company Ltd andTakaful Pakistan Ltd.

18 IIBI www.newhorizon-islamicbanking.com

NEWHORIZON October–December 2009

‘Currently we have alternative models todeliver Islamic banking services in differentparts of the group. We offer servicesthrough the IIAB and Arab Sudanese Bankas full Islamic subsidiaries, with Islamicwindows and branches offered by ArabBank Plc in Qatar and the UAE. The reason behind the different approaches is a combi-nation of market preference and the prevail-ing central bank regulations in thesecountries,’ explains Cobb.

Another critical factor has been the technol-ogy that supports the delivery of the Islamicbanking services. Arab Bank has set upIIAB using a core system from Path Solu-tions, iMAL. Two of its other Islamic unitshave recently launched, and have shownthat different operations require differenttypes of software.

The first project was with the Islamic win-dows and branches in Qatar and the UAE.It is one thing to start a fully Islamic opera-

Established in 1930, Arab Bank was thefirst private sector financial institution inthe Arab world. It has achieved a number of milestones throughout its nearly 80-year history, such as becoming the firstArab financial institution in Switzerland in 1962. It is the largest company listed on the Amman Stock Exchange and thebiggest bank in Jordan in terms of assets,equity and banking market share.

As part of the larger Arab Bank Group, ithas a presence of over 500 branches in 30countries across five continents, and morethan $48 billion in assets. It has been runsince its inception by the Shoman family.Current chairman and CEO, AbdelHamid Shoman, marks the third genera-tion to take charge of the bank that hisgrandfather established.

Across the group it offers products viafour divisions, which are personal bank-ing, corporate and investment banking,private banking and treasury. These areaimed at individuals, corporations, gov-ernment agencies, and other internationalfinancial institutions.

It made the decision to enter the Islamic financial services market 13 years ago with the launch of its International IslamicArab Bank (IIAB) subsidiary. According to Andrew Cobb, chief projects officer at Arab Bank, ‘we wanted to extend the existing services within our establishedbusinesses in the Gulf to provide a wider range of products in response to the needs of our customers and the growing demand for Shari’ah-compliantbanking’.

Horses for coursesGood technology is the cornerstone of any Islamic institution, but different approaches toShari’ah-compliant banking require different systems. One bank with first-hand experience of this is Arab Bank. It has recently completed two implementation projects of separate systemsto cover its operations. James Ling, NewHorizon contributing editor, reports.

tion with a purpose-built Shari’ah-compliantsystem. It is a very different challenge to takean existing conventional institution and addin Islamic products. And, at the end of 2007,this was exactly what the bank wanted todo. ‘We were looking to extend our corpo-rate and treasury Islamic banking productsand services in Qatar and the UAE through a branch/window model,’ says Cobb. Itstarted by defining its business case, beforemoving on to the operating model designand platform selection in the first quarter of 2008.

The technology to power its Islamic offer-ings was an important factor for considera-tion at the bank. It had been using aconventional system for a number of years,but this would not be able to support the additional products. ‘Key processes that underpin the Islamic products and serviceshave special characteristics and functionalrequirements related to Shari’ah rules, in-cluding profit calculation and distributionthat are fundamentally different from inter-est calculation.’ The bank decided thatwhere it did not impact Shari’ah rules andregulations it would leverage its existingback office functions and processes. But itwould need new technology for the rest.

The selection process began with a review of the available Islamic banking systems.The policy at the bank is to ‘consider allknown solutions from existing and potentialsuppliers’, explains Cobb. As a result, ‘weshortlisted a number of solutions and con-ducted an in-depth review with each one be-fore finalising the decision’. It was a rapidselection process which lasted approximatelyeight weeks.

IT FOCUS

Arab Bank

www.newhorizon-islamicbanking.com IIBI 19

NEWHORIZON Shawwal–Dhu Al Hijjah 1430 IT FOCUS

Among the vendors considered was a UK-based software house, Misys. The companyhad an advantage as it provided Arab Bankwith the existing core system it was lookingto expand, Equation. On top of its conven-tional core, the vendor can also boast ahigh number of users for the Islamic versionof its software, particularly in the MiddleEast. Indeed, Equation was tailored for Is-lamic banking in the region. The vendoralso had experience of installing the systemfor Islamic windows, with twelve banks inthe Middle East, South and South East Asiausing it for this purpose on top of their con-ventional operations.

There were a number of factors that led tothe selection of Misys. ‘Arab Bank has along relationship with Misys,’ says Cobb.‘It was very important that we can extendthe current platform functionality using theresources and expertise that we have devel-oped internally.’ The contract with Misyswas signed in April 2008, and the imple-mentation began the following month.

The implementation was two months long,with the first Islamic branch in Qatar goinglive at the end of July. The project contin-ued in Qatar until August 2008. The imple-mentation then moved to the UAE where itran from October to December of that year.

The bank used a team of internal resourcesfrom various banking functions as well asexternal consultants and key staff fromMisys. Cobb puts the rapid implementationdown to good planning, business commit-ment and effective decision making. ‘Thisenabled us to commit to deliver the solutionto our customers within a relatively shorttimeframe.’

The most recent project was at Arab Su-danese Bank. This involved setting up a fullIslamic bank, so presented a different chal-lenge from a technology point of view.

Again, it did a full but rapid selection, opt-ing for iMAL from Path after a six-week re-view of the available products. ‘Thissolution was already implemented at IIABand enabled us to leverage the resourcesand expertise that we have to support this

critical re-launch into Sudan,’ explainsCobb.

The bank signed the contract with Path forArab Sudanese Bank in October 2008 andthe implementation started in November. Itinitiated the programme with a team of in-ternal resources and various external con-sultants. ‘The team collaborated in definingand planning the best approach and imple-mentation phases which enabled us to de-liver Islamic banking to our customerswithin the expectations of senior manage-ment and the Arab Bank CEO,’ says Cobb.‘The project teams worked with high disci-pline to meet the delivery schedule dead-lines and were able to deliver the requiredsolution on time, within budget, and thebank achieved full customer launch in June2009.’

Arab Bank has seen many benefits from expanding its Islamic operations. ‘Primarily,this allows us to provide a wider choice toexisting and new customers. We can achievethis through building on our well estab-lished business and operations and the existing network of branches and sub-sidiaries around the world to this new lineof business.’

The bank is now able to offer a variety ofservices through its new units. ‘We offer full

Islamic banking products and services forretail, corporate and treasury, such asmurabaha, ijara, trade finance, commoditymurabaha and sukuk in addition to Islamicdeposits and services to all our customersegments,’ says Cobb. He believes the newoperations have enabled the bank to offer awider choice for its customers, and addsthat it will ‘continue to deliver the productsbased on our customer needs and develop-ments of the market’.

The experiences of Arab Bank highlight theimportance that different types of technol-ogy play in Islamic banking. When settingup a full Islamic subsidiary there can beconsiderable advantages from taking a com-plete Shari’ah-compliant system. However,if Islamic windows are being added to exist-ing operations, it is always worth consider-ing Shari’ah-compliant modules that can beadded to the conventional core.

Arab Bank had the advantage of previousexperience and knowledge of the systems itchose, and this enabled the rapid selectionand implementation times. However, not allprojects run this smoothly, and the most im-portant factor for banks embarking on thisprocess is making sure they select the systemthat best meets their needs. Arab Bank didthis for both projects and is now reaping thebenefits.

Key processes that underpin the Islamic products and serviceshave special characteristics and functional requirements relatedto Shari’ah rules, including profit calculation and distribution thatare fundamentally different from interest calculation.

Andrew Cobb, Arab Bank

20 IIBI www.newhorizon-islamicbanking.com

NEWHORIZON October–December 2009

Improving Islamic finance in-vestment in socially responsiblebusinesses in the UK was thefocus of the UK’s first Access toIslamic Finance (A2IF) confer-ence, held at the British LibraryConference Centre. It washosted by GK Partners, a con-sultancy firm to socially respon-sible business, in partnershipwith The British Library and theIIBI. The conference followedon from the series of Islamic fi-nance workshops run at the li-brary. Gabrielle Rose of theBritish Library’s Business andIntellectual Property Centre in-troduced the conference.

For the first time in the UK, theA2IF event brought finance pol-icymakers and practitionersfrom the ethical, social enter-prise, community developmentand SME sectors, together withIslamic finance experts, to dis-cuss the areas of common inter-est. As professionals working onenterprise development, A2IFenabled them to understand therelevance of Islamic finance totheir work and highlighted howthey can make new businesspartnerships.

Gibril Faal, director of GK Part-ners and convenor of A2IF,stated that ‘the A2IF pro-gramme is a comprehensive andinclusive approach, based onnew forms of synergistic cross-sectoral partnerships. The prac-tical business benefits andethical virtues of Islamic financeare relevant and consistent withthe values and financing needsof commercial and social enter-prises from a wide range of sec-

Access to Islamic Finance (A2IF): meeting new social economy partners

tors. I want to see more busi-nesses from the social and realeconomy having greater access to Islamic finance funds andservices.’

He spoke passionately abouthow Islamic finance should em-brace new partners in a mannerthat improves the financial andsocio-economic benefits that ac-crue to the whole society andcountry. This theme was rein-

forced by various speakers. An-thony Clarke, chairman of theBritish Business Angels Associa-tion stated that ‘Business Angelinvestment is a form of equity finance which is in line with theIslamic principles of profit-and-loss sharing’. Therefore, he be-lieves that the two types ofmodels fit well together.

Bernie Morgan, CEO of Com-munity Development FinanceAssociation, and Penny Shep-herd, CEO of UK Sustainable Investment and Finance, gavebackground information abouttheir sectors. This demonstratedthe commonality of goals and of-fered a framework for partner-ship and collaboration betweenIslamic, sustainable and commu-nity development investment. Richard T de Belder, partner at

law firm Denton Wilde Sapte,explored the legal and regula-tory challenges relating to theexpansion of Islamic finance in-vestment in UK businesses, andthe issues raised were discussedby other speakers and delegates.Stephen Alambritis of the Feder-ation of Small Businesses urgedIslamic finance institutions (IFIs)to engage with smaller busi-nesses and provided statisticaldata to challenge the myth that

SMEs are riskierbusinesses to investin. MohammedAmin, tax partner at Pricewaterhouse-Coopers, demon-strated how IFIs canuse current tax reliefschemes as incen-tives to increase andexpand their invest-

ments in the commercial and social economy. Some ofthese schemes are already widelyused to enhance equity-based in-vestments in SMEs and socialenterprises.

Ian Shaw, who is responsible forreviewing the government’s En-terprise Finance Guaranteescheme (a loan guaranteescheme introduced to cushionthe impact of the current eco-nomic recession) represented theDepartment of Business, Innova-tion and Skills (BIS). He talkedabout the importance of Busi-ness Link (the government’sbusiness support agency) havinggreater awareness of Islamic fi-nance options. As the only Is-lamic retail bank in the UK,Islamic Bank of Britain (IBB)was among the institutions that

IIBI NEWS

participated in the ‘A2IF mar-ketplace’ – meeting delegates in-terested in their services. FezalBoodhoo of IBB explained thatabout 20 per cent of depositsheld by the bank are in businessaccounts and about 35 per centof the value of IBB mortgages re-late to the bank’s CommercialProperty Finance scheme.

For the benefit of delegates whowere new to Islamic finance,master classes were held. MuftiMuhammad Nurullah Shikderof Gatehouse Bank and MuftiMohammed Zubair Butt of theInstitute of Islamic Jurispru-dence presented on the ‘Princi-ples of Islamic Finance’; DavideBarzilai, partner at law firmNorton Rose, presented on‘Legal Structures of Islamic Fi-nance Products’. For those fa-miliar with Islamic finance butnot with a business background,Faal conducted a master class,‘Shari’ah-Compliant BusinessPlans’. GreenEquity, a firm of Is-lamic and ethical investment ad-visers, presented case studies onthe ‘dos and don’ts’ of raisingequity and debt finance fromIFIs.

As part of the A2IF programme,GK Partners, in association withthe IIBI, had started a researchproject assessing the nature andsize of Islamic finance invest-ment in the UK. Prior to theconference, both BIS and HMTreasury expressed interest inthe results of the findings of theresearch. In light of the potentialpolicy implications of the re-search project, delegates were in-vited to make suggestions and

www.newhorizon-islamicbanking.com IIBI 21

NEWHORIZON Shawwal–Dhu Al Hijjah 1430 IIBI NEWS

recommendations on how Is-lamic finance investment in theUK can be improved. These rec-ommendations were collated tobe reflected in the final reportpublished later this year. At theend of the conference, delegatesexpressed their satisfaction withthe content, quality and diversityof the programme and speakers,with one commenting about theexcellent quality of all the speak-ers who were engaging, conciseand kept the attention of the au-dience.

There was overwhelming realisa-tion and palpable excitement

amongst the profes-sional delegates aboutthe potential for part-nership between Is-lamic finance andother vibrant socio-economic developmentsectors. The first A2IFconference has estab-lished a definitiveframework and plat-

form through which to pursueambitious and feasible goals of‘mainstreaming’ Islamic financein the UK, and improving in-vestment in the corporate, pub-lic, charitable, social enterpriseand SME sectors. GK Partnershas developed an A2IF actionplan to cultivate and deepen re-lationships with new strategicand business partners. Further-more, after the publication ofthe A2IF research report, a se-ries of thematic A2IF events areplanned for 2009/10, focussingon improving Islamic financeinvestments in other sectors ofthe UK economy.

IIBI and SII join forces to promote the UK as Islamic finance hub

The IIBI has inked an agreementwith the Securities and InvestmentInstitute (SII) to promote the UKas the hub of Islamic finance.

The SII is a professional body for practitioners in the securitiesand investment industry globally,which sets professional standardsand measures them through examinations. It also monitorsand develops the competence ofindividual specialists and organi-sations through a code of conduct,and provides continuous profes-sional development (CPD) oppor-tunities for its members, throughseminars, conferences and web-based services.

The institutes will share their ex-pertise and advocate each other’sservices to advance the profes-sional development in the Islamicfinance industry. Aspart of the agreement,the IIBI will encour-age its members tostudy for the SII’s Is-lamic Finance Qualifi-cation (IFQ) as anentry level exam inthe field. In its turn,the SII will promotethe IIBI’s Diplomaand Post GraduateDiploma (PGD) in Islamic Bank-ing and Insurance as qualifica-tions for further progression for

students following achievementof the IFQ. There is also poten-tial for the two organisations todevelop a long-term strategy to

include market research relatingto specialist Islamic financemodules, such as sukuk.

‘We are delighted to work withthe IIBI to promote our com-mon goals for the developmentof Islamic finance skills in theUK,’ said Ruth Martin, manag-ing director of the SII.

Mohammad A. Qayyum, IIBIdirector general, stated that theInstitute is looking forward toworking closely with the SII instrengthening the UK’s positionas the leading centre for Islamicfinance qualifications. ‘Theagreement with the SII will un-doubtedly afford greater scopeof advancement of competentpersons in the Islamic financialservices industry,’ he added.

IIBI and ISRA sign MoU

IIBI and the InternationalShari’ah Research Academyfor Islamic Finance (ISRA)signed a memorandum of un-derstanding (MoU) at a one-day Islamic finance conferencein London, titled ‘ManagingShari’ah Risk through Shari’ahGovernance’.

ISRA was established byMalaysia’s central bank, BankNegara Malaysia (BNM), as arepository of knowledge forShari’ah fatwas and part ofthe International Centre forEducation in Islamic Finance(INCEIF). It also promotes applied research and under-takes studies on contemporaryissues in the Islamic finance industry.

The organisations will workon areas of mutual interest in

Islamic finance to further theknowledge in Shari’ah rulingsas well as other aspects, partic-ularly with regard to transla-tion and fatwa collection.

‘ISRA is playing a very proac-tive role to promote applied re-search in the area of Shari’ahand Islamic finance, and thestrength of our relationshipwill benefit the industry aswhole,’ stated Mohammad A.Qayyum, IIBI director general.

Dr Mohammad Akram, ISRAexecutive director, added: ‘Weare pleased to sign this agree-ment and look forward toworking with the IIBI – theonly organisation of its kind in Europe, in furthering the research as well as other activi-ties intended for promotion ofIslamic finance.’

Mohammad A. Qayyum and Ruth Martin

22 IIBI www.newhorizon-islamicbanking.com

NEWHORIZON October–December 2009IIBI NEWS

The IIBI’s Post GraduateDiploma (PGD) course in Islamic banking and insurance,offered since 1994, is highly regarded worldwide. UK-basedDurham University has ac-corded this course recognitionas an entry qualification for its postgraduate degrees in Is-lamic finance, including the MAand MSc in Islamic finance andthe Research MA. Applicantswill also have to fulfil the spe-cific entry qualifications foreach specialist degree pro-gramme.

To date, students from nearly 80countries have enrolled in thePGD course. In the period ofJuly 2009 to September 2009,the following students success-fully completed their studies:

o Adamu Ibrahim, executive director, IntegratedMicrofinance Bank, Nigeria

o Afsaneh Leissner, trainee solicitor, Gide Loyrette NouelLLP, UK

o Muath Mubarak, assistantmanager, corporate strategy,First Global Group, Sri Lanka

o Alaaddin Karakus, US

o Amjad Zaki Mohamed Radi,head of structured finance products, Qatar National BankIslamic Branch, Qatar

o Enoch Lawrence, senior vicepresident, CBRE, Capital Mar-kets, USA

o Farhan Ahmed, senior finan-cial analyst, Hewlett-Packard,India

IIBI awards post graduate diplomas

o Fawaz Abdul Basith, financial analyst, EKSAB Investments, Saudi Arabia

o Garry Monksfield, director,authorisation, QFCRA, Qatar

o Hussain Buhary, senior manager, Saif Capital (Pvt) Ltd,Sri Lanka

o Hussain Alloub Mohammed,underwriter, export credit insur-ance, The Islamic Corporationfor the Insurance of Investmentand Export Credit (ICIEC),Saudi Arabia

o Inuwa Garba Affa, lecturer,Bahrain Institute of Banking and Finance (BIBF), Bahrain

o Irshad A A Byraub, opera-tions officer, Barclays Bank Plc,Mauritius

o Irum Saba, assistant director,Islamic banking department,State Bank of Pakistan, Pakistan

o Mohamed Farhad Chundoo,compliance officer, South EastAsian Bank Ltd, Mauritius

o Mohammad Amin Tejani,vice president, Habib Metropoli-tan Bank Ltd, Pakistan

o Muhammad Adam, risk analyst, Khushhali BankLtd, Pakistan

o Muhammad Saarim Ghazi,student, International IslamicUniversity, Islamabad, Pakistan

o Muhammad Hisham Alif,junior executive, operations,First Global Group, Sri Lanka

o Muhammad Nadeem, branchmanager, Bank AlFalah, Pakistan

o Muhammad Nasir Aliyu,transaction processing assistant,Bank PHB Plc, Nigeria

o Muhammad Zahid Bhatti,Atlas Asset Management Ltd,Pakistan

o Mukthar MohamedMubarak, assistant manager,Amana Investments Ltd, Sri Lanka

o Mulindwa Mubarak, banking officer, Bank of Africa(U) Ltd, Uganda

o Murtadh Al-Sharae, content manager, ThomsonReuters, UAE

o Nariman A Barakjie, business structuring manager, Access Company WLL, Qatar

o Sani Danbatta, operations manager, Afribanking Plc, Nigeria

o Md Touhidul Alam Khan, executive vice president andhead of syndications andstructured finance, Prime BankLtd, Bangladesh

o Vanessa Wood, associate director, Qatar Financial Centre Regulatory Authority,Qatar.

The course has brilliantly taught me the fundamentals of Islamic banking and in-surance. The lessons are written in such a way that the more you read the moreeager you are to know of what’s coming next. Not only do we understand howIslamic banking functions but we also learn about its history and its value propo-sition, which is very important to get a bigger picture of Islamic finance and itsobjectives. The course was great to follow. The IIBI team is very professional andI would certainly recommend this course to anyone who wishes to learn about Islamic banking. If it’s Islamic banking, then it’s definitely the IIBI!

Irshad A A Byraub, Barclays Bank Plc, Mauritius

Enoch Lawrence Afsaneh Leissner Mohammad Amin Tejani

24 IIBI www.newhorizon-islamicbanking.com

NEWHORIZON October–December 2009

was practically no demand for Islamic finan-cial services domestically. Time is needed tocreate this kind of demand. In a number ofRussia’s regions (Moscow, Tatarstan, Dages-tan, Chechnya, etc.) there is constantlygrowing interest in Islamic financial servicesfrom potential Muslim clients.

o Europe has almost 30 years of experiencein Islamic finance. Over this time there wereboth successes and noticeable failures. InRussia, Islamic financial services were pro-vided by Badr-Forte since the late 1990s. Inother words, an Islamic bank with a limitednumber of products consistent with Shari’ahworked in Russia for just over six years. Thistime span is too short to seriously discuss theprospects of Islamic banking.

Some experts note that one substantial ob-stacle to the development of Islamic financein Russia is lack of demand from the Russianpopulation for such services. This is trueonly in part. Many Muslims realise that conventional financial institutions build their operations on the basis of charging interest. However, they don’t know how theycan avoid participating in interest-bearingtransactions. To resolve this problem it isnecessary that as many people as possiblehave access to information on Islamic finan-cial services.