International Trade By: David Ricardo

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

International Trade

By: David Ricardo

Trade

Buying and selling goods and services from other countries

The purchase of goods and services from abroad that leads to an outflow of currency from the UK – Imports (M)

The sale of goods and services to buyers from other countries leading to an inflow of currency to the UK – Exports (X)

Specialisation and Trade Different factor endowments mean some countries

can produce goods and services more efficiently than others – specialisation is therefore possible:

Absolute Advantage: Where one country can produce goods with fewer

resources than another Comparative Advantage:

Where one country can produce goods at a lower opportunity cost – it sacrifices less resources in production

Biography of David Ricardo

David Ricardo was one of those rare people who achieved tremendous success and lasting fame. After his family disinherited him for marrying outside his Jewish faith, Ricardo made a fortune as a stockbroker and a loan broker. When he died, his estate was worth over $100 million in today's dollars.

At age of 27, after reading The Wealth of Nations, Ricardo got excited about economics. He wrote his first economics article at age of 37 and then spent fourteen years—his last ones—as a professional economist.

In 1814, at the age of 42, Ricardo retired from business and took up residence at Gatcombe Park in Gloucestershire, where he had extensive landholdings.

In 1819 he became MP for Portarlington. Illness forced Ricardo to retire from Parliament

in 1823 and he died on 11 September at Gatcombe Park at the age of 51.

1772~1823

Important assumptions of comparative advantages theory

To simplify analysis the following assumptions should be held.

There are no transport costs. Costs are constant and there are no economies of scale. There are only two economies producing two goods. The theory assumes that traded goods are homogeneous. Factors of production are assumed to be perfectly mobile

within a country but no movement internationally. There are no tariffs or other trade barriers.

Typical Ricardian “2×2 Model”

Labor Requirements in Portugal and England

in Production of the Given Amount of Wine and Cloth

Portugal England

Wine 80 men/year 120 men/year

Cloth 90 men/year 100 men/year

Portugal is superior to England in the two trades since she could produce the both products with less labor input. On the contrary, England is inferior to Portugal in the two industries because she has to employ more labor to produce the given amount of the products.

In accordance with the absolute advantage theory there would no opportunity for the two countries to execute the mutual benefit trade since the above model dose not satisfy the requirement of the “assumption of Adam Smith”.

England in the above model, even has no industry in which it could produce at least one commodity with the absolutely lower cost of labor it necessarily can obtain its trade benefit by taking an active part in the free trade. For Portugal that enjoys the absolute advantages in the both industries, it can also maximize its benefit from the free trade.

Key to understand such mutual benefit of trade

Difference in degrees of advantages of Portugal over England and the difference in degrees of disadvantages of England over Portugal in the two industries.

In producing wine labor requirement in Portugal is 2/3 of that in England and in production of cloth the relevant ratio is 9/10. That is to say the advantage of Portugal in producing wine is much larger than in cloth.

In England, on the contrary, labor requirement in producing cloth is 1/9 more than that in Portugal while labor requirement in producing wine is 1/2 more than that in Portugal.

This concludes that Portugal is much greater advantageous over England in producing wine than in cloth since 2/3 is smaller than 9/10 whereas England suffers from less disadvantages in producing cloth than in wine since 1/2 is larger than 1/9.

Portugal has its comparative advantages in the wine industry while England could be considered to be comparatively advantageous in the cloth industry.

Basic principle of comparative advantages theory

For the country enjoying overall advantages in the both industries, choose one in which it is comparatively more advantageous, while for the other country with overall disadvantages in the both industries, choose one in which it is comparatively less disadvantageous.

Ricardo’s contribution in trade theory Based on the co-called comparative advantages illustrated by

Ricardo and actually enjoyed by all the possible trading countries each of them must have the universal motivation to exchange with the other countries because of real benefit.

Such real benefit constitutes the practical solid foundation for rationality of free trade policy argument.

The significant difference between Adam Smith and David Ricardo is that Ricardo developed free trade philosophy and made such philosophy very much wider applicable.

Ricardo developed classical trade theory from what that merely analyzed some special cases, for instances trade of England and such countries, into the theory which might function as the guidance of trade of almost all countries.

That must be a great theoretical contribution of David Ricardo in development of the pure theory of international trade.

Trade benefit based on comparative advantages theory

Trade benefit based on comparative advantages theory also derived from comparing domestic exchange ratios between the two commodities in the two countries with the exchange rate in international market.

Because the same rule which regulates the relative value of commodities in one country dose not regulate the relative value of the commodities exchanged between two or more countries domestic exchange ratio between the two goods in one country must be different from that in another country.

Such difference prepares possibility for the two countries to initiate bargaining for determining an exchange ratio between the two goods prevailing in international market which represents real benefit for the both countries.

Exchange ratios in an autarky economy

Domestic exchange ratio between wine and cloth in Portugal is 1W : 8/9C or 1C : 9/8W.

That exchange ratio in domestic market in England is 1W : 6/5C or 1C :5/6W.

The relative price of wine in terms of cloth is lower in Portugal than in England. 8/9C﹤6/5C.

The relative price of cloth in terms of wine is lower in England than in Portugal. 5/6W﹤9/8W.

Labor Requirements in Portugal and England

in Production of the Given Amount of Wine and Cloth

Portugal England

Wine 80 men/year 120 men/year

Cloth 90 men/year 100 men/year

Requirements of the two countries and bargaining between them

The exporter of wine, Portugal requires to exchange 1W for more than 8/9C. The importer of wine, England is only willing to give up less than 6/5C for importing 1W from Portugal.

The exporter of cloth, England wants to exchange 1C for more than 5/6W. The importer of cloth, Portugal, is only willing to pay 1C with less than 9/8W.

Exchange ratio in an opening worldThere must be an obvious range between the subjective requirements of the two countries toward the relative prices of the two goods in international market.

For wine, its international exchange ratio would fall into the range between 8/9C till 6/5C.

For cloth, its international exchange ratio would fall into the range between 5/6W till 9/8W.

No matter any point in the respective range at which the international exchanges would be actually executed there must be some gains from trade for the both countries.

8 61

9 5C W C

5 91

6 8W C W

PA

PW

The Gains from TradePrice

S1 D1 Quantity

S

a

b

c

D

Figure 8.2At lower world price, consumer surplus increases to a+b+d an increase of b+d from no-trade

At lower world price, producer surplus falls to c a decrease of b from no-trade

Imports, M1

Gain in trade is triangle d with area equal to ½(M1)(PA-PW)

d

(b) Free Trade

© 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor

B

The Gains from Trade

D

PA

PW

Price

S

S1 Q0 D1 Quantity

Price

M1 Imports

Import demand curve, M

A

A'

No-trade equilibrium

Imports, M1

Each point on the import demand curve is a point that corresponds to Home imports at a given Home price

Figure 8.3

(a) (b)

The Gains from Trade Home Import Demand Curve

We can derive the import demand curve, shown in figure 8.3 The relationship between the world price of a good and the

quantity of imports demanded by Home consumers. At the no-trade equilibrium, there are zero imports

This is shown as point A′ in panel (b). At the world price of PW, the quantity demanded is greater than

quantity supplied, and we import M1.

This is point B in panel (b).

Joining A′ and B gives import demand curve M.

Barriers to international trade adopted by the government to protect the domestic industry. Protectionist measures include tariff and non-tariff barriers.

Protectionism

Barriers to tradeTariffs

A tariff is a tax on imports.

Non-Tariff Barriers (NTB)Non-tariff barriers, unlike tariffs are less direct protectionist measures, which are used to reduce the volume of imports.

Import Tariffs for a Small Country Free Trade for a Small Country

Since Home is a small country, the tariff does not affect world prices. The Foreign export supply curve X* is horizontal at the world price PW.

Effect of the Tariff The new export supply curve shifts up to PW+tariff Quantity demanded falls while quantity supplied rises However, as firms increase the quantity produced, the marginal costs of production rise. The domestic price will equal the import price.

© 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor

Quantity M1 Imports

Foreign export supply, X*

B

Import Tariffs

M

Price

M2

C

Figure 8.4

A

D

X*+tPW+t

Price

S

No-trade equilibrium

M2

Home price rises by the amount of the tariff.Home supply increases and Home demand decreases Imports fall to M2

PW

S1 D1 S2 D2

© 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor

Import Tariffs for a Small Country

Effect of the Tariff on Consumer Surplus With the tariff, consumers now pay the higher price, PW+t, and their surplus is the

area under the demand curve and above the higher price, PW+t.

The fall in consumer surplus due to the tariff is the area in-between the two prices and to the left of Home demand, (a+b+c+d) in panel (a.1) of figure 8.5.

This area is the amount that consumers lose due to the higher price caused by the tariff.

Quantity M1 Imports

Foreign export supply, X*

B

M

Price

M2

C

Figure 8.4

A

D

X*+tPW+t

Price

S

No-trade equilibrium

M2

Home price rises by the amount of the tariff.Home supply increases and Home demand decreases Imports fall to M2

PW

S1 D1 S2 D2

PW+t

PW

Import Tariffs for a Small Country

A

D

Price

S

S1 S2 D2 D1 Quantity

No-trade equilibrium

M2

Lost consumer surplus due to the higher price with the tariff is equal to the shaded area (a+b+c+d)

a

b d

c

Figure 8.5 (a.1)

Effect of the Tariff on Producer Surplus

With the tariff, producer surplus is the area above the supply and below the higher price, PW+t.

Since the tariff increases Home price, firms can sell more goods, and producer surplus increases

This area, a in figure 8.5 (a.2), is the amount that Home firms gain due to the higher price caused by the tariff.

Increases in producer surplus can benefit Home workers but at the expense of consumers.

© 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor

Import Tariffs for a Small Country Effect of the Tariff on Consumer Surplus

With the tariff, consumers now pay the higher price, PW+t, and their surplus is the area under the demand curve and above the higher price, PW+t.

The fall in consumer surplus due to the tariff is the area in-between the two prices and to the left of Home demand, (a+b+c+d) in panel (a.1) of figure 8.5.

This area is the amount that consumers lose due to the higher price caused by the tariff.

The effect of a tariff on imports

Q

P

D

S

SwPw

Qd1Qs1

Pw + tariff

Qd2Qs2

imports

The imposition of the tariff reduced imports from Qs1-Qd1 to Qs2-Qd2

Consumer surplus

The consumer surplus is the difference between the maximum price that consumers are willing to pay and the price that they actually pay.

Q

PS

D

Pe

Producer surplus

The producer surplus is the difference between the minimum price that producers are willing to charge and the price that they actually charge.

Q

PS

D

Pe

The effect of a tariff on welfare

Q

P

D

S

SwPw

Qd1Qs1 Qd2Qs2

imports

Consumer surplus

The effect of a tariff on welfare

Q

P

D

S

SwPw

Pw + tariff

Qd2Qs2

imports

Consumer surplus

The imposition of the tariff reduces the consumer surplus

The effect of a tariff on welfare

Q

P

D

S

SwPw

Pw + tariff

Qd2Qs2

imports

Consumer surplus

While producers and the government gain from the tariff, their combined gain is smaller than the loss to the consumer.

Area a: increase in producer surplus due to tariff

Area c: government tariff revenue

Areas b and d: dead-weight loss to society due to tariff

ab c d

The Flow of Currencies:

Oil

Oil from Russia

£ changed into Roubles Export earnings for Russia

Import expenditure for the UK(Debit on balance of payments)

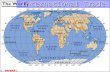

Map courtesy of http://www.theodora.com

Exchange Rates

The rate at which one currency can be exchanged for another e.g.

$1 = 48 Rs £1 = €1.50 Important in trade

Exchange Rates Converting currencies: To convert £ into (e.g.) $ Multiply the sterling amount by the $ rate To convert $ into £ - divide by the $ rate: e.g.

To convert £5.70 to $ at a rate of £1 = $1.90, multiply 5.70 x 1.90 = $10.83

To convert $3.45 to £ at the same rate, divide 3.45 by 1.90 = £1.82

Exchange Rates

Determinants of Exchange Rates: Exchange rates are determined by the demand for

and the supply of currencies on the foreign exchange market

The demand and supply of currencies is in turn determined by:

Exchange Rates

Relative interest rates The demand for imports (D£) The demand for exports (S£) Investment opportunities Speculative sentiments Global trading patterns Changes in relative inflation rates

Exchange Rates Appreciation of the exchange rate:

A rise in the value of $ in relation to other currencies – each $ buys more of the other currency e.g.

$1 = Rs 48 $1=52 India exports appear to be more expensive

( Xp) Imports to the India appear to be cheaper (

Mp)

Exchange Rates Depreciation of the Exchange Rate

A fall in the value of the £ in relation to other currencies - each £ buys less of the foreign currency e.g.

£1 = € 1.50 £1 = € 1.45 UK exports appear to be cheaper

( Xp) Imports to the UK appear more expensive

( Mp)

Exchange Rates

A depreciation in exchange rate should lead to a rise in D for exports, a fall in demand for imports – the balance of payments should ‘improve’

An appreciation of the exchange rate should lead to a fall in demand for exports and a rise in demand for imports – the balance of payments should get ‘worse’ BUT

Exchange Rates

The volumes and the actual amount of income and expenditure will depend on the relative price elasticity of demand for imports and exports.

Exchange RatesRs per $

Quantity onForEx Markets

D$

S$

48

Q1

Assume an initial exchange rate of £1 = $1.85. There are rumours that the UK is going to increase interest rates

Investing in the UK would now be more attractive and demand for £ would rise

D$

Q2

Shortage

Q3

The rise in demand creates a shortage in the relationship between demand for $and supply – the price (exchange rate) would rise

52

Exchange Rates Floating Exchange Rates:

Price determined only by demand and supply of the currency – no government intervention

Fixed Exchange Rates: The value of a currency fixed in relation to an

anchor currency – not allowed to fluctuate Dirty Floating or Managed Exchange Rate:

– rate influenced by government via central bank around a preferred rate

Exchange Rate Regimes

What is a “clean” float? A “dirty” one?

- With a dirty float the government doesn’t peg the currency, but tries from time to time to influence the rate by buying or selling in the currency markets.

Fixed Exchange Rates

How can the government keep a currency at a certain value if international commerce becomes unwilling to pay that price?

It can’t maintain the value for long. If the demand for the currency falls, it’s price would fall as well.

Fixed Exchange Rates

The only way the price can be kept up is for the government promising to maintain the original level to enter the foreign exchange market and bid the price of the currency back up by purchasing it.

Fixed Exchange Rates

The government must buy the amount that will bring the quantity demanded back to the original level.

Quantity of exchangeQuantity of exchange

$ Price of Rs$ Price of RsSupply of dollars Supply of dollars

Demand for dollars Demand for dollars

Fixed Exchange Rates

To what does the government fix the value of its currency?

When or how often does the country change the value of its fixed rate?

Fixed Exchange Rates

How does the government defend the fixed value against any market pressures pushing toward higher or lower exchange rate value?

Fix to what?

In the past, all currencies were fixed to gold.

Today, a country can fix its value to another country’s currency.

Fix to what?

A country can fix its currency to a “basket” of other currencies.

-Same as diversifying a portfolio (Not putting all your eggs in one basket)

-Special Drawing Right (SDR)…A basket of four major world currencies.

Defending a Fixed Exchange Rate

1. To buy or sell foreign currencies (in order to influence the prevailing exchange rate), a government must have foreign exchange reserves.

2. It is not likely to have enough reserves to defend against a massive and sustained attack on the currency. What is an attack on a country’s currency?

Defending a Fixed Exchange Rate

How can higher i rates keep the currency value up?

(Answer: Foreigners will purchase the nation’s currency, bidding its value upward, to make short-term investments in the country.)

Defending a Fixed Exchange Rate

3. The government can also make long-term adjustments of its macroeconomic (monetary and/or fiscal policy).

Budget austerity avoids inflation and takes downward pressure off currency.

Defending a Fixed Exchange Rate

3. Why does inflation put downward pressure on a country’s exchange rate?

Non-inflating countries are unwilling to pay more and more to buy an inflating country’s goods and services. Reduced demand for the inflating currency will make it depreciate.

When to Change the Rate?

What is a pegged exchange rate? The term pegged exchange rate refers to

setting a targeted value for a country’s foreign exchange, and it indicates the govt. has some ability to move the peg.

When to Change the Rate?

Governments attempt to keep the value fixed for relatively long periods of time to reduce trade uncertainties.

What is an adjustable peg? The government may change the pegged

rate if a substantial disequilibrium in the country’s international position develops (e.g., demand for the currency is too weak to maintain the desired value).

When to Change the Rate?

A crawling peg can be changed often (monthly, say) according to a set of indicators or the judgment of the country’s monetary authority.

Indicators: The difference of inflation rates Interest Rates International reserve assets Growth of the money supply Growth of Economies

The Floating Exchange Rate

Clean Float Supply and Demand are solely

private activitiesComplete flexibility

When to Change the Rate?

Governments attempt to keep the value fixed for relatively long periods of time to reduce trade uncertainties.

What is an adjustable peg? The government may change the pegged

rate if a substantial disequilibrium in the country’s international position develops (e.g., demand for the currency is too weak to maintain the desired value).

When to Change the Rate?

A crawling peg can be changed often (monthly, say) according to a set of indicators or the judgment of the country’s monetary authority.

Indicators: The difference of inflation rates International reserve assets Growth of the money supply The current actual market exchange rate relative

to the central par value of the pegged rate

The Floating Exchange Rate

Clean Float Supply and Demand are solely

private activitiesComplete flexibility

The Floating Exchange Rate

Dirty Float (Managed Float)From time to time, the

government tries to impact the rate through intervention

More popular than clean floatEffectiveness of intervention is

controversial

To improve a poor macroeconomic situation, a country increases its money supply so that banks are more willing to lend.

Interest rate drops

Real spending, production, and income rise, but

Capital flows out.((in the short run)

The Current account balance “worsens” as exports fall and imports increase.

The overall payments balance “worsens.”

The price level increases.

Expanding the Money Supply Worsens the Balance of Expanding the Money Supply Worsens the Balance of Payments Payments

Monetary Policy with Fixed Exchange Monetary Policy with Fixed Exchange RatesRates

Thoughts on Fixed and Floating Rates

Times have changed since the early 1970s and Nixon’s destruction of Bretton Woods. Markets have developed to hedge exchange risks and we have become accustomed to the uncertainties associated with them. Trade flourishes.

On Exchange Rate Choices

Many countries have gone to the float for their exchange rates, but many still decide to peg their currency or fix their exchange rate. The choice is probably the most important macro-economic policy decision a country makes.

66

What Changes the Equilibrium Rate?

Inflation rates: Higher domestic inflation means less demand for local

goods (decreased supply of foreign currency) and more demand for foreign goods (increased demand for foreign currency).

Interest rates: Higher domestic (real) interest rates attract investment

funds causing a decrease in demand for foreign currency and an increase in supply of foreign currency.

Economic growth: Stronger economic growth attracts investment funds

causing a decrease in demand for foreign currency and an increase in supply of foreign currency.

67

What Changes the Equilibrium Rate?

Political & economic risk: Higher political or economic risk in the domestic country

results in increased demand and reduced supply of foreign currency.

Changes in future expectations: Any improvement in future expectations regarding the

domestic currency or economy will decrease the demand for foreign currency and increase the supply of foreign currency.

Government intervention: Maintain weak currency to improve export

competitiveness.

Balance of Payments Accounting

The Balance of Payments is the statistical record of a country’s international transactions over a certain period of time presented in the form of double-entry bookkeeping.

N.B. when we say “a country’s balance of payments” we are referring to the transactions of its citizens and government.

69

Balance of Payments

The BOP is a statistical record of the flow of all of the payments between the residents of a country and the rest of the world in a given year.

Transactions are recorded on the basis of double entry bookkeeping – by definition it has to balance. Every “source” must have a “use”.

The two main components are: Current Account Capital/Financial Account

70

Balance of Payments

71

Current Account (CA)

This is record of a country’s trade in goods and services in the current period.

CA = Exports (X) – Imports (M)

It is divided into 4 sub-categories: Goods trade Services trade Income Current transfers

The sum of the four sub-categories = CA balance

72

Capital Account (KA)

This includes all short- and long-term transactions pertaining to financial assets.

KA = Capital Inflow (cr) – Capital outflow (dr)

The two main components: Capital account. Financial account (direct, portfolio, other).

KA balance = Sum of capital account and financial account.

73

Official Reserves

Records the purchase or sale of official reserve assets by the central bank. These assets include

Commercial paper, Treasury bills and bonds Foreign currency Money deposited with the IMF

This account shows the change in foreign exchange reserves held by the central bank.

Since the BOP must balance

CA + KA + RFX = 0

CA + KA = – RFX

The Balance of Payments

Identity

For floating rate regime countries, such as the U.S., official reserves are relatively unimportant.

74

Statistical Discrepancy (E&O)

The identity CA + KA = – RFX assumes that all transactions are measured accurately.

Inaccurate recording of transactions (errors & omissions), results in the above equality not holding. For BOP to balance,

CA + KA + E&O = – RFX

Assuming changes in official reserves, errors are approximately zero:

Current Account = (–) Capital Account

This will hold approximately for floating rate countries

75

CA ≈ -KA

76

A surplus in the BOP implies that the demand for the country’s currency exceeded the supply and that the government should allow the currency value to increase – in value – or intervene and accumulate additional foreign currency reserves in the Official Reserves Account.

A deficit in the BOP implies an excess supply of the country’s currency on world markets, and the government should then either devalue the currency or expend its official reserves to support its value.

BOP in Total

77

Examples of Transactions

An Australian company exports goods worth US$1 million to the United States: Export of goods is credit for the current account. Increase in foreign asset (US$1 million) is debit for capital

account.

Australian company then coverts US$ into A$ and buys government bonds back in Australia: Decrease in foreign asset is credit for the capital account. Increase in government liability is debit for official reserves

account.

Australian individual imports a sports car from Europe: Increase in foreign liabilities is credit for the capital account. Import of goods is debit for current account.

78

A nation’s balance of payments interacts with nearly all of its key macroeconomic variables.

Interacts means that the BOP affects and is affected by such key macroeconomic factors as: Gross Domestic Product (GDP) Exchange rate Interest rates Inflation rates

BOP & Macroeconomic Variables

79

A country’s BOP can have a significant impact on the level of its exchange rate and vice versa.

The relationship between the BOP and exchange rates can be illustrated by use of a simplified equation that summarizes the BOP (see next slide).

BOP & Exchange Rates

80

(X – M) + (CI – CO) + (FI – FO) + FXB = BOP

Where:X = exports of goods and servicesM = imports of goods and servicesCI = capital inflowsCO = capital outflowsFI = financial inflowsFO = financial outflowsFXB = official monetary reserves

Current Account Balance

Capital Account Balance

Financial Account Balance

BOP & Exchange Rates

81

Fixed Exchange Rate Countries Under a fixed exchange rate system, the

government bears the responsibility to ensure that the BOP is near zero.

Floating Exchange Rate Countries Under a floating exchange rate system,

surpluses/deficits influence exchange rate.

BOP & Exchange Rates

Related Documents