HARvaRD I BUsrr{ Ess I scnool 9-3 84-049 REV: MARCH 16,201r E. TATUM CHRISTIANSEN RICHARD T, PASCALE Honda (A) The two decades from 1960 to 1980 witnessed a strategic reversal in the world motorcycle industry. By the end of that period, previously well-firnnced American competitors with seemingly impregnable market positions were faced with extinction. Although most consumers had an initial preference to purchase from them, these U.S. manufacturers had been dislodged by ]apanese competitors and lost position despite technological shifts that could have been emulated as competition intensified. The ]apanese invasion of the world motorcycle market was spearheaded by the Honda Motor Company. Its founder, Soichiro Honda, a visionary inventor and industrialist, had been involved peripherally in the automotive industry prior to World War II. However, Japan's postwar devastation resulted in the downsizing of Honda's ambitions; motorcycles were a more technologically manageable and economically affordable product for the average fapanese. Reflecting Honda's commitment to a technologically based strategy, the Honda Technical Research Institute was established in 1946. This institute, dedicated to improvements in intemal combustion engines, represented Honda's opening move in the motorcycle field. In 1947, Honda introduced its first A-t'?e, 2-stroke engine. As of 1948, Honda's Japanese competition consisted of 247 lapanese participants in a loosely defined motorcycle industry. Most competitors operated in ill-equipped job shops, adapting clip-on engines for bicycles. A few larger manufacturers endeavored to copy European rnotorcycles but were hampered by inferior technology and materials that resulted in unreliable products. Honda expanded its presence in the fall of 1949, introducing a lightweight 50cc, 2-stroke, Dtype motorcycle. Honda's engine at 3 hp was more reliable than most of its contemporaries' engines and had a superior stamped metal frame. This introduction coincided closely, however, with the introduction of a 4-stroke engine by several larger competitors. These engines were both quieter and more powerful than Honda's. Responding to this threat, Honda followed in 1951 with a superior 4- stroke design that doubled horsepower with no additional weight. Embarking on a bold campaign to exploit this advantage, Honda acquired a plant, arrd over the next two years it developed enough manufacturing expertise to become a fully integrated producer of engines, frames, chains, sprockets, and other ancillary parts crucial to motorcycle performance. E 95 H <= 3 aqP 49o p4 d oEA ot€ 3<; BNb Dr. RidErd T. Pascale of StanJord Graduate Sdool of Busins pEpared ihis case with the collaboration of Profe$o! E. Tatum Christiansen of Harr'ard Business S.rhool. This cae was developed fiom published sources. HBS cas€s a1e developed solely as the basis for clas dis.ussion. Cases are not intended to se e as odoRments, souces of primary data, or illustratioN of effective or ineffe.tive manaSemeni. Note: This case is based largelV on HBS No. 587-210, "Note on the Motatcycle Industry '1975,' and o a publistud ftpott aJ the Boston Consulti g Ctoltp, "StntegV Ahematies fot thz Btitish Mototctcle lndustry," 1975. Copyright O 198, 1989, 2011 Presidmt and Fenows of Ha ard College. To ords copies or Equ6t pdmission to reproduce materials, €aI]1- 800 54'7685, wnte Harvad Business School PublishinS, Boston, MA 02163, or go io 9Mw.hb6p.ha ard.€du/educato6. This publication may nor be digirized, photocopied, or otheruise reproduced, posted, or transmitt€d, oithout the pmission of Harard Busin€ss Scllool. oirribur.d by...h, Ul( and UsA orth Amert.. Aen ot rh. Frtd the CaSe fof leafnino wsw..kh.@n ! +r7sr23es3a4 I +44(o)1234750e03 Allrishls re*rv.d o e.drus.@etdtion € e..h(i.cch..on

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

HARvaRD I BUsrr{ Ess I scnool

9-3 84-049REV: MARCH 16,201r

E. TATUM CHRISTIANSEN

RICHARD T, PASCALE

Honda (A)

The two decades from 1960 to 1980 witnessed a strategic reversal in the world motorcycleindustry. By the end of that period, previously well-firnnced American competitors with seeminglyimpregnable market positions were faced with extinction. Although most consumers had an initialpreference to purchase from them, these U.S. manufacturers had been dislodged by ]apanesecompetitors and lost position despite technological shifts that could have been emulated ascompetition intensified.

The ]apanese invasion of the world motorcycle market was spearheaded by the Honda MotorCompany. Its founder, Soichiro Honda, a visionary inventor and industrialist, had been involvedperipherally in the automotive industry prior to World War II. However, Japan's postwar devastationresulted in the downsizing of Honda's ambitions; motorcycles were a more technologicallymanageable and economically affordable product for the average fapanese. Reflecting Honda'scommitment to a technologically based strategy, the Honda Technical Research Institute wasestablished in 1946. This institute, dedicated to improvements in intemal combustion engines,represented Honda's opening move in the motorcycle field. In 1947, Honda introduced its firstA-t'?e, 2-stroke engine.

As of 1948, Honda's Japanese competition consisted of 247 lapanese participants in a looselydefined motorcycle industry. Most competitors operated in ill-equipped job shops, adapting clip-onengines for bicycles. A few larger manufacturers endeavored to copy European rnotorcycles but werehampered by inferior technology and materials that resulted in unreliable products.

Honda expanded its presence in the fall of 1949, introducing a lightweight 50cc, 2-stroke, Dtypemotorcycle. Honda's engine at 3 hp was more reliable than most of its contemporaries' engines andhad a superior stamped metal frame. This introduction coincided closely, however, with theintroduction of a 4-stroke engine by several larger competitors. These engines were both quieter andmore powerful than Honda's. Responding to this threat, Honda followed in 1951 with a superior 4-stroke design that doubled horsepower with no additional weight. Embarking on a bold campaign toexploit this advantage, Honda acquired a plant, arrd over the next two years it developed enoughmanufacturing expertise to become a fully integrated producer of engines, frames, chains, sprockets,and other ancillary parts crucial to motorcycle performance.

E

95 H

<= 3

aqP49o

p4 d

oEA

ot€3<;BNb

Dr. RidErd T. Pascale of StanJord Graduate Sdool of Busins pEpared ihis case with the collaboration of Profe$o! E. Tatum Christiansen ofHarr'ard Business S.rhool. This cae was developed fiom published sources. HBS cas€s a1e developed solely as the basis for clas dis.ussion.Cases are not intended to se e as odoRments, souces of primary data, or illustratioN of effective or ineffe.tive manaSemeni.

Note: This case is based largelV on HBS No. 587-210, "Note on the Motatcycle Industry '1975,' and o a publistud ftpott aJ the Boston Consulti g Ctoltp,"StntegV Ahematies fot thz Btitish Mototctcle lndustry," 1975.

Copyright O 198, 1989, 2011 Presidmt and Fenows of Ha ard College. To ords copies or Equ6t pdmission to reproduce materials, €aI]1-800 54'7685, wnte Harvad Business School PublishinS, Boston, MA 02163, or go io 9Mw.hb6p.ha ard.€du/educato6. This publication maynor be digirized, photocopied, or otheruise reproduced, posted, or transmitt€d, oithout the pmission of Harard Busin€ss Scllool.

oirribur.d by...h, Ul( and UsA orth Amert.. Aen ot rh. Frtdthe CaSe fof leafnino wsw..kh.@n ! +r7sr23es3a4 I +44(o)1234750e03

Allrishls re*rv.d o e.drus.@etdtion € e..h(i.cch..on

Honda (A)

Motorcycle manufacturers in the Japanese industry tended to minimize risk by investing in onewiruring design and milking that product until it became technologically obsolescent. Beginning inthe 1950s, Honda began to depart frorn this pattern-seeking simultaneously to (1) offei amultiproduct line, (2) take leadership in product innovation, and (3) exploii opportunities foreconomies of mass production by gearing designs to production objectives. Most notably, in 1958Honda's market research identified a large, untapped market segment seeking a small,unintimidating motorcycle that could be used by small-motorcycle businesses for local deliveries.Honda designed a product specifically for this application: a step-through frame, automatictransmissiory and one-hand controls that enabled drivers to handle the machine with one hand whilecarrying a package in the other. The 50cc Honda was an explosive success. Unit sales reached 3,000per month after six months on the market. Deciding to make this the product of the future, Hondagambled, investing in a highty automated 30,000-unit-per-month manufacturing plant-a capacity 10times in excess of demand at the time of construction.

Honda's bold moves set the stage for a yet bolder decision-to invade the U.S. market. Thefollowing section depicts the sequence of events as taken from a Harvard Business School case on thenotorcycle industry.l

In 1959 ... Honda Motor Company ... entered the American market. The Japanese motorcycleindustry had expanded rapidly since World War II to meet the need for cheap transportation. In 1959,Honda, Suzuki, Yamaha, and Kawasaki together produced some 450,000 motorcycles. With sales of$55 million in that year, Honda was already the world's largest motorcycle producer. . .

In contrast to other foreign producers who relied on distributors, Honda established a U.S.subsidiary, American Honda Motor Company, and began its push in the U.S. market by offering verysmall lightweighi motorcycles. The Honda machine had a three-speed transmissiory an automaticclutch, five horsepower (compared with two and a half for the lightweight motorcycle then sold bySears, Roebuck), an electric starter, and a step-through frame for female riders. Generally superior tothe Sears lightweight and easier to handle, the Honda machines sold for less than 9250 retail,compared with $1,000-$1,500 for the bigger American or British machines.

Honda followed a policy of developing the market region by region, beginning on the West Coastand moying eastward over a period of four to five years. In 1961 it lined up 125 dealers and spent$150,000 on regional advertising. Honda advertising represented a concerted effort to overcome theunsavory image of motorcyclists that had developed since the 1940s, given special prominence by the1953 movie The Wild Ones, which starred Marlon Brando as the surly, destructive leader of amotorcycle gang. In contrast, Honda addressed its appeal prirnarily to middle-class consumers andclaimed, "You meet the nicest people on a Honda." This marketing effort was backed by heavyadvertising, and the other Japanese exporters also invested substantial sums: $1.5 million for Yamahaand $0.7 million for Suzuki.

Honda's strategy was phenomenally successful. Its U.S. sales rose from $500,000 in 1960 b $nmillion in'\965.8y 1966, Honda, Yamaha, arrd Suzuki together had 857o of the U.S. rnarket. From anegligible position in 1950, lightweight motorcycles had corne to dorninate the rnarket.

The transformation and expansion of the motorcycle market during the early 1960s benefitedBritish and American producers as well as the Japanese. British exports doubled between 1960 and1966, while Harley-Davidson's sales increased from 916.6 million in 1959 to $29.6 million in 1965.Two press reports of the mid-1960s illustrate these haditional manufacturers' interpretation of theJapanese success:

E

di E€

*6I6:E= 3tRs2?t9: i;o=6

?:*

saErT2'BNh

:)

1 D. Purkayastha and R. Buzzell, "Note on tlle Motorcycle Industry-1975," HBS No. 578-21Q pp. 5-7.

Honda (A)

"The success of Honda, Suzuki, and Yamaha in the States has been jolly good for us,,, EricTumer, chairman of the board of BSA Ltd., told Advefiising Age. "People here start out bybuying one of the low-priced Japanese jobs. They get to enjoy the fun and exhilaration of theopen road and frequently end up buying one of our more powerful and expensive nachines.,,The British insist that they're not really in competition with the Japarese (they're on the lighterend). The Japanese have other ideas. Just two months ago Honda introduced a 444cc model tocompete, at a lower pdce, with the Triumph 500cc. lAdaertising Age, December 27 , 19651

"Basically we do not believe in the lightweight market," says William H. Davidsory son ofone of the founders and currently president of the company (Harley-Davidson). "We believethat motorcycles are sports vehicles, not transportation vehicles. Even if a man says he boughta motorcycle for transportatior; it's generally for leisure time use. The lightweight motorcycleis only supplemental. Back around World War I, a number of companies came out withlightweight bikes. We came out with one ourselves. We came out with another one in 1942 andit iust did not go anywhere. We have seen what happens to these small sizes." fForbes,September 15, 19661

Meanwhile, the Japanese producers continued to grow in other export markets. ln 1965, domesticsales represented only 59% of Honda's total of 9316 million, down from 98% in 1959. Over the sameperiod, production volume had increased almost fivefold, from 285,000 to 1.4 million units. InEurope, where the ]apanese did not begin their thrust until the late 1960s, they had captured acommanding share of key markets by 1924.

In short, by the mid-1970s the Japanese producers had come to dominate a market shared byEuropean and American producers 20 years earlier, . .

It was often said that Honda created the market for the recreational uses of motorcycles throughits extensive advertising and promotional effort.

The company achieved a significant product advantage through a healy commitment to R&D andadvanced manufacturing techniques. Honda used its productiviiy-based cost advantage and R&Dcapability to introduce new models at prices below those of cornpetitive machines. New productscould be brought to market very quickly; the interval between conception and production wasestimated to be only 18 months. Honda was also reported to have a "cold storage" of designs ihaicould be introduced if the market developed. . . .

Since 1960, Honda had consistently outspent its competitors in advertising. It had also esiablishedthe largest dealership network in the U.S. On average, Honda dealers were larger than theircompetitors. In new markets, Honda had been willing to take short-term losses in order to build upan adequate selling and distribution network.

In 1975, the Boston Consulting Group was retained by the British govemment to diagnose theBritish motorcycle industry and the factors contributing to its decline. The remainder of this case,reflecting on Honda's strategy, consists of excerpts from that reporL2

The market approach of [Honda] has certain common features which, taken together, may bedescribed as a "marketing philosophy." The fundamental feature of this philosophy is the emphasis itPlaces on market share and sales volume. Objectives set in these terms are regarded as critical, anddefended at all costs.

2 Boston Consulting Group, "strategy Altematives for the British Motorcycle lndustrr" Her Majesty's Stationary Office,London, 30 Jdy 1975, pp. 1,G17 , 23, 3943, a'+-55.

E

ar59b8s6 3

ti 3_aR s<3EaqP

9- b.:E

oEq.':.Eg<;rT2.pNh

i q'X

Honda (A)

The whole thrust of the markethg program . . . is towards maintaining or improving market shareposition. . . . We have seen some ways in which this goal is pursued. It is worth adding, as anexample of how pervasive this objective is . . . that in an interview with a Honda persorurel director,we were told ihat the first question a prospective Honda dealer is asked is the level of his marketshare in his local area. "I don't know why, but this company places an awful lot of emphasis onmarket share" was the comment. . . . We shall retum to the reasons why lnarket shares are critical forcommercial success in the industry.

We were also told by representatives of [Honda] that their primary obiectives are set in terms ofsales volume rather than short-term profitability. Annual sales targets-based on narket sharepenetration assumptions and market growth prospects-are set, and the main task of the salescompany is to achieve these targets. The essence of this strategy is to grow sales volume at least asfast or faster than any of your competitors.

A number of more specific policies follow from this general philosophy, and our descriptions ofeach of the japanese competitors provide ample examples of these poLicies:

1. Products are updated or redesigned whenever a market threat or opportunity is perceived.

2. Prices are set at levels designed to achieve market share targets and will be cut if necessary.

3. Effective marketing systems are set up in all markets where serious competition is intended,regardless of short-term cost.

4. Plans and objectives look to long-term payoff.

The results of these policies for the Japanese competitors have, of course, been spectacularlysuccessful. Over the last fifteen years, the rates of growth of the four major Japanese companies havebeen as shown in Table A.

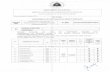

Table A Growth of Japanese Production

E

F; g

36 3

<= 3_aR I<di Eaq2

dEc

g<;.9!5

-

Production in 1959(000 units)

Production in 1974(000 units)

Avelage AnnualGrowth Rate

(o/o o.a.l

Honda

Yamaha

Kawasaki

Suzuki

285

64

10

96

2,133

1 ,165

355

840

14

21

16

Source: JapanAutomobilelndustryAssociation.

Selling and distribution systems We have so far discussed market share as a function of theproduct features and prices of particular models. Market share across all cc classes is also influencedby what we shall call the selling and distribution system (s and d system). Within the s and d systemwe include all the activities of the marketing comparries (or importers) in each national market:

. Sales representation at the dealer level

. Physical distribution of parts and machines

o Warranty arrd service support

Honda (A) 384-(X9

. Dealer support

. Advertising and promotion

. Market planning and control

We also include the effects of the dealer network established by the marketing companies:

. Numbers and quality of dealers

o Floor space devoted to the manufacturers' products

. Sales support by dealers

The s and d system supports sales of the manufacturer across the whole model range, and itsquality affects market shares in each cc class where the manufacturer is represented. Table Bcompares the s and d systems of the four full-line Japanese manufacturers in the USA, and shows thathigh market shares both overall and in each cc class go with high levels of expenditure on s and d andwith extensive dealer networks.

The interaction between product-related variables and s- and d-related variables is complex. Thebetter the product range in terms of comprehensiveness, features, and price, and the moresophisticated the s and d system of the sales company, the easier it will be to attract good dealers.This is because good products, which are well supported at the marketing company level, lead togood retail sales. Equally, good dealers themselves irnprove retail sales, and active competitionbetween dealers can lead to retail discounting which acts as a volume-boosting price cut to the public.The manufacturers' products and s and d system therefore hfluence sales both directly, at retail, andproximately, through thefu effeci on the dealer network.

In particular cc categories, each manufacturer's position is substantially influenced by its specificproduci offerings. For example, Kawasaki are strong in the 750cc-and over class due to the Z-1, andYamaha have been weak due to its poor 750cc model. Outstanding products obtain market sharesthat are unusually high for a manufacturer, and weak products lead to atypically low market shares.For products of average attraction, however, market shares seem to move towards some equilibriumlevel. For each manufacturer, this level in the USA appears to be:

E

.:isn

9b896 H

€:8+.! e

aqP

oEq

9<;r!>\

*=E

:Honda

YamahaKawasaki

Suzuki

40100/o

15-250/"'lo-15"/o

9-12/"

As overall market leaders, the Japanese have dominated pricing in the motorrycle industry. It istherefore appropriate to begin this analysis by examining the extent to which the experience curveconcept appears to explain the performance of the Japanese. Unfortunately, it is impossible directly todetermine unit cost performance data for competitors, since the data are not publicly available.Sources can be found, however, for unit price and production volume data. Over the long term, pricebehavior is a useful guide to movements in the underlying costs, and so an experience curve analysison prices can be extremely reveaLing.

]apanese price performance In Figure A, price expedence curyes are drawn for the Japanesernotorcycle industry as a whole, based on aggregate data collected by MITI. These curves show pricereduction Performance of a consistent nature for each of the size ranges of rnotorcycle considered, therate of price reduction being most rapid of all in the largest range, 126-250cc, which is following anexperience curve slope of 76Y". Tt.e other slopes are more shallow, at 81% and 887., but there is no

Honda (A)

mistaking the fact that real prices are descending smoothly over time. These experience-based pricereductions clearly go a long way towards explaining the historical competitive effectiveness of thejapanese in the marketplace in small and medium motorcycles.

Table B The Selling and Distribution Systems of Japanese Companies in the U.S.A.

Es{d Total S&DExpenditureby AdvedigingSalesCompany Expendituie

1974 ($m) 1972 ($m)

Dealers 1974 1974 o/o Shar.e

Units Sold ofTotalNumbers DerDealer Market (units)

Lowest o/o Highest o/o

ShareofAny Shale ofanycc Cla6s cc class

HondaYamahaKawasakiSuzuki

8.1

4.22.2

90-10040-4530-3525-30

1,9741,515

1,018

1,103

220135

127

98

61

34

1S

16

34

4I5

4320

13

1l

Source: R.L. RoIk, Motorcycle Dealet Neus, Zilf-Davis Market Research Dept., BCG estimates.

For the purposes of strategy development ... it is [helpful] to look more closely at priceperformance in the larger bike rnodels. The Honda CB 750 has been the pacesetter in superbikes interms of both market penetration and pricing. In Figwe B, price experience curves are plotted for thisproduct and for two other large Honda bikes. The prices of other Japanese manufacturers have beenbroadly comparable to Honda's in the equivalent size range (they usually tend if anything to price ata slight prernium relative to Honda), so that we may use Honda as a good "benchmark" for theJapanese competition in big bikes in general.

Figure A |apanese Motorcycle brdustry: Price Experience Cuwes,1959-1974

''' a

a;

(million unils)

(YO00

1965)

E

r*ii

e6 SAE<;- E

aqi!.16:5: X

oEq

s-E"9N;

i s'X

-

' * "" -----------t"r-t- j.l-*H*" t'"t i'.8..1-_ __

----

Source: MITI.

Honda (A)

Figure B Honda Large Bikes: Price Experience Curves

Price

Honda pdces in U.S.

384449

500

400

E

isIgt;9b3g6 3

€= 6

<di EaqP

6:56E!-

oEq

g<;BNb

Retail list pice(+000, 1965)

Honda's Cumulalive Volume(Million Units > 250 cc)

It is clear from Figure B that price performance in the large bikes has been consistent with that insmall: real prices have declined along experience curve slopes in the region of 857.-87%. This has alsobeen true of the price in the United States, when converted into yen terms.

An interesting feature of the curves is that the prices in the United States are so much higher than[those] of the same products in Japan. As shown in Table C, the premiums are high across almost theentire range of bikes and are far larger than seems necessary, even allowing for the extra costs

c8750

Honda (A)

incurred for duty, freight, and packing in shipping bikes from Japan io the United States. Thiscertainly suggests that there is no possibiLity that the Japanese are "dumping" their products in theU.S. markeh quite the reverse. Furthermore, it may well indicate that competitive though theJapanese have been in the United States, based on the downward trends in their real price levels overtime, there may well be plenty of scope for them to be even more competitive in the future ifseriously challenged in that market. They could simply reduce their margins on exports to the UnitedStates to levels more in Line with those enjoyed in their domestic business.

Table C Honda Price Premium, USA vs. Japan

Premium on retail list prices, 1974

Mod"l # p"iu""si$) p""-io*cB 750cB 550cB 450cB 360cB 350MT 250MT 125cB 125

395 141'l355 1268303 1082253 904275 982218 779158 564166 593

20241732't471

11501363965743640

430/"

37./"36%26./.39v"240/o

32%ao/"

E

€: E

qd|E(,)Qe

I9 p

o=!

\', e 3-

J9>.Btb

Premium allowing for lreight, duty and packingCB 750, U.S. retail price 1975 = $2112

$1584 (75o/" ol 2't12),$1!|23 (65%)

Y440,000 orgEE (equivalent)

$ e86 (65o/d

6063 (3% U.S. Retail Price)40

$ 163

Thus, indicated price to U.S. distributor lor equal manufacturer's margin to that on bikes sold in Japan

$1149

rhus' premium in u s A even after a]oflvJls#ltt'-nli',oi}o*o **'*

Note: The versions ol the smaller bike models shipped to the States may be slightly more expensivethan their Japanese equivalents (extra lighting, etc.). The versions of the larger bikes are, however,reported to be identical in both markets.

lapanese cost perforrnance The implication of the downward trends in real prices for thefapanese is, of course, that there have been underlying experience-based cost reductions: that thedecline has not been accounted for simply by a reduction in margins.... However, the majorfapanese manufacturers have been continuously profitable, and this suggests that cost reductionshave indeed taken place in parallel with real price reductions. On the other hand, all the Japanese

Price to dealerPrice to distributor

Japan list price

Price to distributorOcean freight to LADutyPackaging costs

Honda (A)

motorcycle manufacturers also make a significant proportion of products other than motorcycles (in"1974 about 35% of Honda's tumover, and about 407o of Suzuki's, was accounted for by cars; ofYamaha Motor's tumover about 40% was in products such as boats and snowmobiles). Ii is, perhaps,reasonable to question whether these products are sufficiently profitable to ,,subsidize,, themotorcycle business.

. . . It seems clear that . . . none of [the three major Japanese] manufacturers is subsidizing themotorcycle business from other businesses. Indeed, Honda was actually losing money in its carbusiness in 1974, which suggests thai their rnotorcycle business that year may have shown retums ofthe order of 20% (BIT) compared wiih the 12.4% return eamed by the company overall. The overallinference from this profit performance must be that each manufacfurer has indeed achieved anexperience curve effect on costs in parallel with those achieved on price. The existence of thisexperience curve effect in the motorcycle industry has important strategy implications.

Competitive Strategy Implications

As we have discussed, failure to achieve a cost position-and hence cost reductions over time-equivalent to your competitors' will result in commercial vulnerabiLity. At some point yourcompetitors will start setting prices which you carmot match profitably, and losses will ensue. Thestrategic importance of the experience curve is that it explains clearly the two possible long-termcauses of uncompetitive costs:

o Relative growth: failure to grow as rapidly as competitors, thereby progressing more slowlythan them along the experience curve.

o Relative slopes: failure to bring costs down the characteristic experience curve slope achievedbycompetitors....

Summary

From the perspective of the writers of the BCG study, a fundamental cause for the Japanesesuccess was their high productivity. The motorcycle industry was exhibiting the effects thatdifferences in growth rates, volume, and level of capital investment among competitors can have onrelative costs. The high rates of growth and levels of production achieved by the japanesemanufacturers resulted in their superior productivity. In terms of value added per employee, Hondaoutperformed Western competitors by as rnuch as four times. Even the smaller ]apanese competitorswere able to outperform their Westem counterparts by a factor of two or three.

The BCG report also countered the common argument that the relatively inexpensive Japaneselabor was the primary source of competitive advantage. The Japanese cornpetitors in fact had higherlabor costs than companies in the West. Their relative high growth and scale caused total costs todrop quickly enough to support regular pay increases and price decreases at the same time.

Essentially the argument presented by BCG was that the Japanese emphasis on market share asthe primary obiective led to high production volume, improved productivity, low costs, and in thelong term to higher profitability than their competitors.

E

i9@d ilt

s6 3

€iE

.,qc69',"9- bo:6

3< 3

BN:

g'e I

HARvaRD I BUsrirEss I scn oor-

E. TATUM CHRISTIANSEN

RICHARD T, PASCALE

Honda (B)

soichiro Honda, an inventive genius with a legendary ego, founded the Honda Motor Co., Ltd., in1948. His exploits have received wide coverage in the Japanese press. Known for his mercurialtemperament and bouts of "philandering,"l he is variously reported to have tossed a geisha out asecond-story window,2 climbed inside a septic tank to retrieve a visiting supplier,s fals-e teeth (andsubsequently placed the teeth in his own mouth),3 appeared inebriated and in costume before aformal presentation to Honda's bankers requesting finaniing vital io the firm,s survival (the loan wasdenied),4 hit a worker on the head with a wrench,s and stripped naked before his engineers toassemble a motorcycle engine.6

Company Background

Postwar JaPan was in desperate need of transportation. Motorcycle manufacturers proliferated,producing clip-on engines that converted bicycles into makeshift ;'mopeds." soichiro'Honda wasamon8 these, but his prior experience as an automotive repairmar provided neither the financial,managerial, nor technical basis for a viable enterprise.

soichiro Honda viewed "technology" as the vehicle through which Japanese society could berestored and the world made a better place in which to live. Reflecting the intensity of thiscomrnitnent, he established the Honda Technical Research Institute in 1946. The term institute wassomewhat misleading, since the organization was composed of himself and a few associates and hadno practi.al means of support. Under this organizational umbrella, he began to tinker, and, as ameans of livelihood, he purchased 500 war surplus engines and rehofitted them for birycle use.Lacking marketing know-how, he entered into an exclusive arrangement with a distribuior, whopackaged a motorcycle conversion kit for bicycles. The Honda Motor Company was formed. Further

9-384-050REV: MARCH 16,2011

1 Sakiya, Tetsuo. "The Story of Honda's Founders ," Asahi Eoening Ne:a/s,lune l-August 29, 1979, Series #2 and #3.

2 Interviews with Honda executives, Tokyo, JaparL July 1980.

3 Sakiya, Tetsuo. Hor?d, Motot: Tfu Men, The Ma egement, The Machi es, Kadonsha Intemational. Tokyo, Japan, 19g2, p 69; alsoSakiya, "Honda's Founders," Sedes lf4.

4 Sakiya, "Honda's Founders," Se es +f7 and tl8.

5 Sakiya, Hondlt Motot, p.72.

6 Sakiya, "Honda's Fourldels," Series #2.

E

EX g

*5ald::

iE 3

6ZP59-9:,8

s4 d6: g

:)

Dr. Ri.hard T Pa$ale of Sta.nfod Graduate School of Business wrote rhis case w h the coltaborarion of piofessor E. Tatum Christiansen ofHaNard Business ftnool lt is based Iargely on intemal Honda souces and interiews with fouders of Honda Moror Co., Lrd., dd the Japanesemanagemmt team that founded Honda of Anqica HBS €ases a.e developed solely as the basis for .lass discussion. Cases are not intm'ded toseFe as endorsemmis, sou€es of primary daia, or ilusrrations of €ffedive;r ineff€dive mdagemenr.

CoPyriSht O 19$, r9s9, 2011 Presideni md lelows of Hanard Colle8e. To order copi€s or request permission to reproduce materials, call 1-800-54t7585, write Harad Business Schml Publishing, Boston, MA 02163, or go to www.hbsi.hanira.edu/educarors. This pubticarion maynot be digitized, PhotocoPied, or otheMis€ reproduced, posbed, or kesmitted, wiihour the permission of Haflard B$ines Schoot.

Di*ributed by @h, Ux lnd UsA nonh An.ri.. i6t ot the mrtdthe CaSe fOf leafninO ww..G<hron t +17a123e$a4 r +44 to) | 234 7soeo3

J Att'ight5E€.ved e [email protected] e [email protected],con

Honda (B)

tinkering led, in tum, to the introduction of the "A-design"-a 2-stroke, 50cc engine. The engine hadnumerous defects, and sales did not materialize. scraping by on occasional orders, the company lostmoney in 1947 and grossed 955,000 in 1948.

In 1949, Soichiro Honda tumed to friends. Raising $3,800, he developed and introduced the 2-stroke, D-type engine. This engine, generating 3 hp, was more reliable than most on the market andenjoyed a brief spurt of popularity. Recruiting a work force of 70 employees, Honda producedengines one at a time and approached an annualized production rate of 100 units per month by theend o11949.

Success was short-lived, however. Honda's exclusive distributor elected to artificially limit sales to80 units per month in order to maintain high margins. soichiro Honda was irate and vowed to avoidsuch dependencies in the future. In late 1949 he set out to raise additional financing but suffered asecond setback when competitors leapfrogged the 2-stroke design and introduced quieter and morepowerful 4-stroke engines.

A classic dilemma now faced the struggling enterprise. Honda's engine was obsolete, and hisdistribution system held him at ransom. Without additional financing he could not correct thesedeficiencies, and bants and investors did not regard him as a sould management risk.

In late 1949, an intermediary urged him to accept a partner-Takeo Fujisawa. Fujisawa wasprepared to invest 2 million yen (about $2500). More irnportant, Fuiisawa brought financial expertiseand marketing strengths.

Despite Fujisawa's presence, the firm continued to falter. No further capital could be raised in1950. Fujisawa pressed his partner to quit tinkering with his noisy 2-stroke engine and join theindustry leaders with a -stroke design, since it was clear that competition had threatened Hondawith extinction. At first too proud to accept this counsel, in 1951 he unexpectedly unveiled abreakthrough design that doubled horsepower over competitive 4-stroke engines. With thisinnovatiory the firm was off and putting, and by 1952 demand was brisk.z

Honda's superior 4-stroke engine enabled Fujisawa to raise $88,000 in 1952. With these funds,Fuiisawa committed to reduce dependency on suppliers and distributors by becoming a full-scalemotorcycle manufacturer. To forestall technological obsolescence, he encouraged Honda to stayabreast of technological developments. He also sought more flexible channels of distribution.Unfortunately, Honda was a relatively late entrant the best Fujisawa could do was to arrange forseveral distributors to carry Honda as a secondary line. He compensated for weak productpositioning by going directly to the consumer with advertising.

In late 1952 a sewing machine plant was purchased and converted to a crude motorcycle factory.Neither partner had managerial or manufacturing experience, and there was no real plan other thanto work as long as necessary each day to keep up with orders. Honda's more powerful engine andsuperior stamped motorcycle frame created considerable interest, and demand remained strong.Employment leaped from 150 in 1951 lo 1,337 by the end of 1952. Honda inte$ated into theproduction of chains, sprockets, and motorcycle frames. Altogether, these factors greatly complicatedthe management task, There were no standardized drawings, procedures, or tools. For several yearsthe plani was, in effect, a collection of semi-independent "activities" sharing the same roof.Nonetheless, by the beginning of 1959 Honda had become a significant participant in the industry,with 23% market share (see Exhibit 1).

E

*ba,di:--.e8 39U H

9;6-$ 9!Ei:d3Ei9r,6=6e at6!Q d

d:e

e,rE

:)

7 Sak]ya, Honda Motor, pp. 71-72.

Honda (B) 384-050

Honda's successful 4-stroke engine eased the pressures on Fuiisawa by increasing sales andproviding easier access to financing. For Soichiro Honda, the higher-horsepower enghe opened thepossibility of pursuing one of his central ambitions in life: to build and to race a high-performance,special-purpose motorcycle-and win. Wiruring provided the ultimate confirmation of his designabilities. Racing success in Japan came quickly. As a result, in 1959 he raised his sights to theinternational arena and committed the firm to winning at Great Britain's Isle of Man-the"Oly.rnpics" of motorcycle racing.8 Agairg Honda's inventive genius was called into play. Shiftingmost of the firm's resources into this racing effort, he embarked on studies of combustion thatresulted in a new configuration of the combustion chamber, which doubled horsepower and halvedweight. Honda leapfrogged past European and American competitors-winning in one class, thenanother, winning the Isle of Man manufacturer's prize in 1959, and sweeping the first five positionsby 1961..e

Throughout the 1950s, Fujisawa sought to tum his partler's attention from enthusiasm withracing to the more mundane requirements of running an enterprise. By 1956, as the innovationsgained from racing had begun to pay off in vastly more efficient engines, Fujisawa pressed Honda toadapt this technology for a commercial motorcycle.l0 He had a particular segment in mind. Mosimotorcyclists in Japan were male, and the machines were used primarily as an alternative form oftranspodation to trains and buses. However, a vast number of small commercial establishments inJapan still delivered goods and ran errands on bicycles. Trains and buses were inconvenient for theseactivities. The purse strings of these small enterprises were controlled by ihe Japanese wife-whoresisted buying conventional notorcycles because they were expensive, dangerous, and hard tohandle. Fujisawa challenged his partner: Can you use what you've learned from racing to come upwith an inexpensive, safe-looking motorcycle that can be driven with one hand (to enable carryingpackages)?11

The First Breakthrough

In 1958 the Honda 50cc Supercub was introduced-with an automatic clutch,3-speedtransmission, automatic starter, and the safe, friendly look of a bicycle (without the stigma of theoutmoded mopeds). As a rule of ihurnb, a 50cc engine is 50% cheaper to make than a 100cc engine.Achieving high horsepower with a small engine thereby reaps automatic cost savings-making thenew bike affordable. lnnovative design provided a cost advartage without requiring Honda tomanufacture more efficiently than its competitors. (This was fortunate since the firm, havingexpanded into three plants in the 1950s, had still noi achieved a well-integrated production process.)

Ovemight, Honda was overwhelmed with Supercub orders. Demand was met through makeshift,high-cost, cornpany-owned assembly and farmed-out assembly through subcontractors.l2 By the endof 1959 Honda had skyrocketed into first place among Japanese motorcycle manufacturers. Of itstotal sales that year of 285,000 units, 168,000 were Supercubs.l3 The time seemed appropriate to buildan automated plant with a 30,000-unii-per-month capacity. "It wasn't a speculative investment,"

8 Sakiya, "Honda's Founde6," Series #11.

e rbid.

10 lbid., Sedes #13; also Sakiya, Honda Motor, p. 1't7 .

11 Sakiya, "Honda's Founders," Sedes #11.

12 Pascale, Richard T., lnterviews with Honda executives, Tokyo, Japary September 10, 1982.

13 Data provided by Honda Motor Company-

E

oE.=4

*Eo,,64

r!3.rye

6ZP

-9- bc=6

.9 d;di 3

ti i: N:3.9 H

r :'6

384-050 Honda (B)

recalls one executive. "we had the proprietary technology, we had the market, and the demand wasenormous."14 The plant was completed in mid-1960.

Distribution Channels

Fujisawa utilized the supercub to restructure Honda's charnels of distribution. For rnany years,Honda had rankled under the two-tier distribution system that prevailed in the industry. As notedearlier, these problems had been exacerbated by Honda's being carried as a secondary line bydistributors whose loyalties lay with older, established manufacturers. Further weakening Honda'ileverage, all manufacturer sales were on a consignment basis,

Fujisawa had characterized the Supercub to Honda's distributors as ,,something much more like a

bicycle than a motorcycle." The traditional channels, to their later regret, agreed. Under amicableterms, Fuiisawa began selling the supercub directly to retailers-and primarily through bicycleshops. Since these shops were small and numerous (approximately 12,000 in Japan), salej onconsignment were unthinkable. A cash-on-delivery system was installed-giving Honda significantlymore leverage over its dealerships than the other motorcycle manufacturers enjoyed.ls

Honda Enters U.S. Market

Soichiro Honda's racing conquests in the late 1950s had given substance to his convictions abouthis abilities. success fueled his appetite for new and different challenges. Explosive sales of theSupercub in Japaa provided the financial base for new quests. The stage was now set for theexploration of the U.S. market.

From the Japanese vantage point, the American market was vast untapped, and affluent. ,,We

tumed toward the United States by a process of deduction," states one executive. ,,Our experimentswith local Southeast Asian markets in 1957 and 1958 had little success. With little disposable incomeand_poor_roads, total Asian exports had reached a meager 1,000 units in 1958.16 The EuropeanmarkeL while larger, was heavily dominated by its own name-brand manufacturers, and the popularmopeds dominated the low-price, low-horsepower end."

Two Honda executives-the designated president of American Honda Motor Company,Kihachiro Kawashima, and his assistant-arrived in the United States in late 1958. Their itinerary:San Francisco, Los Angeles, Dallas, New York, and Columbus. Kihachiro Kawashima recounts hisimpressions:17

My first reaction after traveling across the United States was "How could we have been sostupid to start a war with such a vast and wealthy country!" My second reaction wasdiscomfort. I spoke poor English. We dropped in on motorcycle dealers who treated usdiscourteously and, in additiory gave the general impression of being motorcycle enthusiastswho, secondarily, were in business. There were only 3,000 motorcycle dealers in the UnitedStates at the time, and or y 1,000 of them were open five days a week. The remainder wereopen on nights and on weekends. lnventory was poor, manufacfurers sold motorcycles to

E

f;a]

tE IetBE!;aA2d66696.EE

a:6

9:i.!!"

:J

14 Pascale interviews.

ls Ibid.

16Ibid.

17tbid.

Honda (B) 384-050

dealers on consignment, the retailers provided consumer financing, and after-sale service waspoor. It was discouraging.

My other impression was that everyone h the United States drove an automobile-makingit doubtful that motorcycles could ever do very well in the market. However, with 450,000motorcycle registrations in the United States and 60,000 motorcycles imported from Europeeach year it didn't seem unreasonable to shoot for 10% of ihe import market. I returned toJapan with that report.

ln truth, we had no strategy other than the idea of seeing if we could sell something in theUnited States. It was a new frontier, a new challenge, and it fit the "success against all odds,,culture that Mr. Honda had cultivated: I reported my impressions to Fujisawa-including theseat-of-the-pants target of hying, oyer several years, to attain a 10% share of the U.S. imports.He didn't probe that target quantitatively. We did not discuss profits or deadlines forbreakeven. Fuiisawa told me if anyone could succeed, I could, and authorized g1 million forthe venture-

The next hurdle was to obtain a currency allocation from the Ministry of Finance. Theywere extraordinarily skeptical. Toyota had launched the Toyopet in the United States in 1958and had failed rniserably. "How could Honda succeed?" they asked. Months went by. We putthe project on hold. Suddenly, five months after our application, we were given the go-ahead-but at only a fraction of our expected level of comrnitment. "You can invest 9250,000 in the U.S.market," they said, "but only $110,000 in cash." The remainder of our assets had to be in partsand motorcycle inventory.

We moved into frantic activity as the govemment, hoping we would give up on the idea,continued to hold us to ihe ]uly 1959 start-up timetable. Our focus, as mentioned earlier, was tocompete with the European exports. We knew our products at the time were good, but not farsuperior. Mr. Honda was especially confident of the 250cc and the 305cc machines. The shapeof the handlebar on these larger machines looked like the eyebrow of Buddha, which he feltwas a strong selling point. Thus, after some discussion and with no compelling criteria forselection, we configured our start-up inventory with 25% of each of our four products-the50cc Supercub and the 125cc,250cc, and 305cc machines. In dollar-value terms, of course, theinventory was heavily weighted toward the larger bikes.

The stringent monetary controls of the |apanese govemment together with the unfriendlyreception we had received during our 1958 visit caused us to start small. We chose Los Angeleswhere there was a large second- and third-generation Japanese comrnunity, a climate suitablefor motorcycle use, and a growing population. We were so strapped for cash that the three ofus shared a furnished apartment that rented for 980 per month. Two of us slept on the floor.We obtained a warehouse in a run-down section of the city and waited for the ship to arrive.Not daring to spare our funds for equipment, the three of us stacked the motorcycle cratesth-ree-high, by hand; swept the floor; and built and mainiained the parts bin.

We were entirely in the dark the first year. We were not aware that the motorcycle businessin the United States occurs during a seasonable April-to-August window*and that our timingcoincided with the closing of the 1959 season. Our hard-leamed experiences withdistributorship in Japan convinced us to try to go to the retailers direct. We ran ads in themotorcycle trade magazine for dealers. A few responded. By spring 1960, we had 40 dealersand some of our inventory in their stores- mostly larger bikes. A few of the 250cc and 305ccbikes began to sell. Then disaster struck.

E

*;r Q,)

'n:t

9:5aqej,4 3

*9,"6=6

ir 3

:!:

Honda (B)

By the first week of April 1960, reports were coming in that our machines were leaking oiland encountering clutch failure. This was our lowest moment. Honda,s fragile reputation wasbeing destroyed before it could be established. As it tumed out motorcycles in the UnitedStates are driven much farther and much fasier than in Japan. We dug deeply into our preciouscash reserves to air freight our motorcycles to the Honda testing lab in Japan. Throughout thedark month of April, Pan Am was the only enterprise in the United States that was nice to us.Our testing lab worked 24-hour days bench testing the bikes to try to replicate the failure.Within a mont[ a redesigned head gasket and clutch spring solved the problem. In themeantime, events had taken a surprising turn.

Throughout our first eight months, following Mr. Honda's and our own hstincts, we hadnot attempted to move the 50cc Supercubs. While they were a smash success in ]apan (andmanufacturing couldn't keep up with demand there), they seemed wholly ursuitabie for theU.S._market where every.thing was bigger and more luxurious. As a clincher, we had our sightson the import market-and the Europeans, like the American manufacturers, emphasized thelarger machines.

We used the Honda 50s ourselves to ride around Los Angeles on errands. They attracted alot of attention. One day we had a call from a Sears buyer. While persisting in our refusal tosell through an intermediary we took note of Sears's interest. But we still hesitated to push the50cc bikes out of fear they might harm our image in a heavily macho market. But when thelarger bikes started breakhg, we had no choice. We let the 50cc bikes move. And surprisingly,the retailers who wanted to sell them weren't motorcycle dealers; they were sporting goodsstores.

The excitement created by Honda Supercub began to gain momentum. Under restrictionsfrom the Japanese goverrunent, we were still on a cash basis. Working with our initial cash andinventory we sold machines, reinvested in inventory, and sunk the profits into additionalinventory and advertising. Our advertising tried to straddle the market. While retailerscontinued to inform us that our Supercub customers were normal everyday Americans, wehesitated to target toward this segment out of fear of alienating the high-margin end of ourbusiness-sold through the traditional motorcycle dealers to a more traditional ,,black leatherjacket" customer.

€

'n :6

€LE

=-9:6q,"

-9 d694d(4&4

g=tf :2\

An Advertising Twist

As late as 1963, Honda was still working with iis original Los Angeles advertising agency, its adcampaigns straddling all customers so as not to antagonize one market in pursuit of another.

In the spring of 1963, while fulfilling a routine class assignmmt, an undergraduate advertisingmajor ai UCLA submitted an ad campaign for Honda. Its theme was "You Meet the Nicest People Ona Honda." Encouraged by his instructor, the student passed his work on to a friend at GreyAdvertising. Grey had been soliciting the Honda account-which, with a g5-million-a-year budget,was becoming an attractive potential client. Grey purchased the student's idea-on a tightly kepinondisclosure basis. Grey attempted to sell the idea to Honda.l8

Interestingly, the Honda management team, which by 1963 had grown to five Japanese executives,was badly sPlit on this advertising decision. The president and treasurer favored another proposalfrom another agency. The director of sales, however, felt strongly that the Nicest people carnpaign

18Ibid.

Honda (B)

was the right one-arld his commitment eventually held sway. Thus, h 1963, Honda adopted astrate8y that directly identified and targeted that large, untapped segment of the marketplace thatwas to become inseparable from the Honda legend.l9

The Nicest People campaign drove Honda's U.S. sales at an even greater rate. By 1964 nearly oneout of every two motorcycles sold was a Honda. As a result of the influx of medium-income leisure-class consumers, banks and other consumer credit companies began to finance motorcycles-shiftingaway frorn dealer credit, which had been the traditional purchasing mechanism available. Honda,seizing the opportunity of soaring demand for its products, took a courageous and seemingly riskyposition. Late in 1964 it announced that thereafter, it would cease to ship on a consignment basis butwould reqrrire cash on delivery. Honda braced itself for a revolt that never materialized. \,Vhile nearlyevery dealer questioned, appealed, or complained, none relinquished the Honda franchise. In one feilswoop, Honda shifted the power relationship from the dealer to the manufacturer. Within threeyears, C.O.D. sales would become the pattern for the industry.20

Honda's growth on several dimensions is shown n Exhibrt 2. Automobiles were introduced intothe product line in 1963, shifting resources and management attention heavily in that direction in theensuing years.

25 Years Later

In late 1972, anticipating the company's twenty-fifih anniversary, Fujisawa,62, raised the issue ofretirement. "We are strong dominating individuals," he said. "I must step aside and let the youngermen lead our company." Soichiro Honda, 66, also conceded to retire. In September 1923, the twostepped down. States one source: "Fujisawa retired early to provide Mr. Honda with an opportunityto retire, also. It is a reflection of Fujisawa's genuine personal friendship with Mr. Honda.,,2l

19Ibid.

20 tbid.

21 Sakiya, Tetsuo. "The Story of Honda's Found efi," Asahi E@ning News, August 29, 1979.

E

d3

*b@d:€.eg 3

f e 3a+qE2tU)d-3

i9 r,'

"E!

o: !-Io€: !:

! >E

:)

Honda (B)

Exhibit 1 Motorcycle Production in ]apan by Japanese Makers

KawasakiYamahaCalendarYear Honda

19s0

1951

1952

1953

1954

1955

1956

1957

1958

1959

1960

1961

1962

1963

1964

1965

1966

1967

1968

1969

1970

1971

1972

1973

1974

1975

1976

1977

't974

1979

1980

1981

531

2,380

9,659

29,797

30,344

42,557

55,031

77,509

117,375

285,214

649,243

935,859'1,009,787

1,224,695

1,353,594

1,465,762

't,422,949

'1,276,226

'1,349,896

1,534,882

1,795,828

1,927,186'1,873,893

1,835,527

2,132,902

1,742,444

1,928,576

2378,467

2,639,588

2,437,057

3,087,47'l

3,587,957

2,272

4,743'15,811

27,1e4

63,657

138,153

't29,O79

117,908

167,370

221,655

244,O5A

389,756

406,579

423,039

519,710

574,100

750,510

853,317

1,012,810

1,164,886

1,030,541

1 ,169,175

1,824,152

1,887,31 1

1,653,891

2,241,959

2,792,417

9,079

18,M4

29,132

66,363

95,862

155,445

186,392

173,121

27'1,438

373,871

34'1,367

M8,128

402,438

365,330

398,784

407,538

491,064

594,922

641,779

839,741

686,666

831,941

'1,031,753

1,144,488

1,100,778

1,551,'127

1,764,120

200

5,083

6,793

7,O18

10,104

9,26r

22,034

31,718

34,954

33,040

44,745

67,959

79,194

74,124

102,406

149,480

208,904

218,058

250,099

354,615

274,O22

2a4,478

335,1 12

326,317

308,191

521,446

521,333

6,960 7,491

21,773 24,153

69,586 79,245

131,632 '161,429

133,929 164,473

205,487 259,395

245,459 332,760

280,819 410,064

283,392 501,332

425,78A 880,629

520,982 1,473,0A4

531,003 1,804,371

342,391 1,674,925

229 ,5't3 1 ,927 ,970

128,175 2,110,335

112,452 2,212,7A4

118,599 2,447,391

77,410 2,241 ,447

34,946 2,251.335

2'1,091 2,576,873

20,726 2,947,672

22,434 3,400,502

25,056 3,565,246

22,912 3,763,'t27

17,276 4,509,420

28,470 3,802,547

20,942 4,235,112

7,475 5,577,359

2,225 5,999,929

79 5,499,996

- 7,402,403

- 8,666,227

E

r; g

*teJ'n:fe3I6-?{E Its6:6JP60,":* boF6

g;;::2,

; !;

Source:

Note:

Japan Automobile Manufacturers AssociatiotL Inc.

KD sets and scooteG are included.

Honda (B)

Exhibit 2 Honda's Financial Performance and U.S. Motorcvcle Sales

Calendar Gross SalesYear (million yen) Sales (units) (million ven) Emplovees

Honda U.S.Motorcycle

1,31;

6,052

27,840

65,869

110,470

227,308

272,900'181,200

174,706

272,600

441,200

656,800

707,800

556,300

628,500

343,900

444,624

439,822

401,114

OubideFinancing

1948

1949

1950'1951

'1952

1953

1954

1955'1956

1957

1958

'1959

1360

1961

1962

1963

'1964

1965

1966

1967

1968

1969

1970

't971

't972

'1973

't974

1976

1977

1978

14.3

34.6

82.8

330.3

2,434

7,729

5,979

-90- 150

'1,337

2,185

1

2

15

60

20

70

5,525

7,882

9,786

14,188

26,165

49,128

57,912

64,552

83,206

97,936

123,746

106,845

141,179

193,871

244,895

316,331

332,931

327,702

366,777

519,897

563,805

668,677

849,635

922,280

360

720't,440

4,320

8,640

9,090

18,180

19,480

24,350

25,500

29,600

13,165

16,614

't7,511

18,079

14,297

18,287

18,455'18,505

'19,069

19,968

2'1,316

_ 2,494

120 2,459

2,377

2,438

2,705

3,355

4,053

5,406

5,798

6,816

7,696

8,481

- 9,069

_ 11,283

E

Eg tl

*rG)

! .g

iiq59t

I9p:- o

oEE

:

Note: Above figures are related solely to Honda Motor Co.. Ltd., and are not consolidatedwith those of its subsidiaries.

Related Documents