Home Office Research Study 275 Offending in England and Wales: First results from the 2003 Crime and Justice Survey Tracey Budd, Clare Sharp and Pat Mayhew The views expressed in this report are those of the authors, not necessarily those of the Home Office (nor do they reflect government policy). Home Office Research, Development and Statistics Directorate January 2005

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

Home Office Research Study 275

Offending in England and Wales:First results from the 2003 Crime and Justice Survey

Tracey Budd, Clare Sharp and Pat Mayhew

The views expressed in this report are those of the authors, not necessarily those of the Home Office (nor do they reflect government policy).

Home Office Research, Development and Statistics DirectorateJanuary 2005

Home Office Research Studies

The Home Office Research Studies are reports on research undertaken by or on behalf ofthe Home Office. They cover the range of subjects for which the Home Secre t a ry hasre s p o n s i b i l i t y. Other publications produced by the Research, Development and StatisticsDirectorate include Findings, Statistical Bulletins and Statistical Papers.

The Research, Development and Statistics Directorate

RDS is part of the Home Office. The Home Off i c e ’s purpose is to build a safe, just and tolerantsociety in which the rights and responsibilities of individuals, families and communities arep roperly balanced and the protection and security of the public are maintained.

RDS is also part of National Statistics (NS). One of the aims of NS is to inform Parliament andthe citizen about the state of the nation and provide a window on the work and perf o rm a n c eof government, allowing the impact of government policies and actions to be assessed.

T h e re f o re –

R e s e a rch Development and Statistics Directorate exists to improve policy making, decisiontaking and practice in support of the Home Office purpose and aims, to provide the public andParliament with information necessary for informed debate and to publish information forfuture use.

First published 2004Application for reproduction should be made to the Communications and Development Unit,Room 201, Home Office, 50 Queen Anne’s Gate, London SW1H 9AT.© Crown copyright 2005 ISBN 1 84473 541 9

ISSN 0072 6435

Offending in England and Wales: First results from the 2003 Crime and Justice Survey

Foreword

The Crime and Justice Survey is a new national self-report offending survey. It provides thefirst national self-report evidence on offending levels amongst the general population agedten to 65 living in private households in England and Wales.

The survey shows that offending in the general population is uncommon with one in tencommitting an offence covered by the survey in the last year. Offending is highest during theteenage years, with males being more likely to offend than females. However, even amongthis group many only offend infrequently or commit relatively trivial offences. A minority ofoffenders, though, are highly prolific and account for the vast majority offences measured.Ta rgeting these prolific offenders and those most likely to become prolific offenders willtherefore be an important feature of strategies to reduce crime.

The survey also shows that although most offences are not formally sanctioned a substantialminority of offenders, particularly the most serious or prolific, have contact with the criminaljustice system at some point.

Future waves of the survey will follow up young people aged ten to 25. This will provideevidence on how offending 'careers' develop and change over time and allow furt h e rexamination of the role of risk and protective factors. It will also provide further data ontrends in youth offending.

Jon Simmons Assistant DirectorResearch Development and Statistics DirectorateHome Office

i

Acknowledgments

This report is the result of a lengthy development process and we would like to extend ourthanks to all those involved along the way. Particular thanks are due to Catriona Mirrlees-Black (RDS) and Carol Hedderman (RDS) who provided invaluable support and advice andto Ruth Hayward (RDS, University of Surrey) for her assistance with the data analysis.Thanks are also due to former colleagues Dr. Bonny Mhlanga and Joanna Taylor who wereinvolved at the early stages of this project.

The research teams from National Centre for Social Research and BMRB Social Researchcontributed enormously to the design of the survey and efficiently managed the datacollection process.

We would also like to thank the members of the academic community who assisted in thisp roject, whether through contributing survey questions, reviewing the questionnaire orreviewing this report. These are:

Dr. Stephen Farrall (Keele University)Professor David Farrington (University of Cambridge)Bernard Gallagher (University of Huddersfield)Professor Susanne Karstedt (Keele University) Professor Michael Levi (Cardiff University)Professor Peter Lynn (University of Essex)Susan McVie (University of Edinburgh)Andrew Percy (Queen’s University Belfast)Dr. Mike Sutton (Nottingham Trent University)Professor Janet Walker (University of Newcastle Upon Tyne)

And finally, we extend our thanks to members of the public who participated in this study.

Offending in England and Wales: First results from the 2003 Crime and Justice Survey

ii

iii

Contents

PageExecutive summary v

1 Introduction 1Survey aims 1Crime and Justice Survey design 2

Limitations 2Measuring offending 3

The future 5Structure of report 5

2 The Crime and Justice Survey in context 7Administrative statistics on offenders 7Police statistics on crime 7Victimisation surveys 7Self-report surveys of offending 8The Crime and Justice Survey 9

Age range 10Sample size and coverage 10The questionnaire and its administration 10Measuring offending 11

Comparisons with other data sources 133 The extent of offending 15

The prevalence of lifetime offending 15Frequency of lifetime offending 16The prevalence of offending in the last year 17

Gender differences 17Age differences 18Age and gender 18

Number of offenders in England and Wales 20Comparisons with known offenders 21

Number of offences 22Volume of crime committed by young offenders 23Profile of offences committed 24Non-core offences 25

4 Serious and prolific offenders 27Frequency of last year offending 27Prolific offenders 29Serious offenders 31

The volume of serious crime 32An offender typology 33The number of serious or prolific offenders 34The volume of crime committed by prolific offenders 35

5 Contact with the criminal justice system 39Self-reported offending versus convictions 39General contact with the criminal justice system 41Offenders’ contact with the criminal justice system 42

Lifetime offenders 42Last year offenders 43

Offences dealt with by the criminal justice system 44Proportion of offences accounted for by known offenders 45

6 The pattern of offending 47Age of onset 47Age of desistence and length of offending 49Reasons for desistence 50Specialisation versus diversification 52Offending profile 53Endnote 54

7 The nature of offences 55Where and when incidents happened 56Seriousness of the incidents 56

What type of force was used 57The value of damage 58The value of stolen property 58

Victims 59Victim-offender relationship 59Victim characteristics 60

Co-offending 60Motivation for offending 61

The role of drugs and alcohol 62The importance of sanctions 64Views on re-offending 65

8 Conclusions 67Appendix A: Additional tables 73Appendix B: Methodology 101Appendix C: Offence screener questions 113References 119

Offending in England and Wales: First results from the 2003 Crime and Justice Survey

iv

Executive summary

This report presents the first findings from the 2003 Crime and Justice Survey (C&JS). This isa new national survey covering around 12,000 people aged between ten and 65 living inprivate household in England and Wales. It provides a unique picture of the extent andnature of offending across the general household population, covering a much broader agerange than in previous self-report offending surveys. The survey does not cover people livingin institutions, including prisons, or the homeless.

The C&JS collected information on the extent of lifetime and last year offending. It alsolooked at drug and alcohol use, attitudes to and contact with the criminal justice system andexperiences of victimisation. This report focuses on offending behaviour. It concentrates on20 ‘core’ offences which were measured by the survey (see Box 1). These exclude someoffences that were asked about in less detail (handling stolen goods, various types of fraud,and ‘technology’ offences, such as illegally downloading software).

All ‘core’ offences were transgressions against criminal law, though they will inevitablyinclude some incidents that are relatively trivial (e.g. a low value theft from the workplace).H o w e v e r, there is value in collecting information about such lower level activity. Minort r a n s g ressions can run alongside more serious offending. Exploring the full range ofo ffending throws light on what diff e rentiates serious and prolific offenders, and althoughindividual offences may themselves be trivial, they can lead to significant social andeconomic costs at an aggregate level.

The report identifies serious and prolific offenders. Serious offenders are defined as thosecommitting: theft of a vehicle; burglary; robbery; theft from the person; assault with injury;or the selling of Class A drugs. Prolific offenders are those who committed six or moreoffences in the last year.

v

Executive summary

Box 1 The seven offence categories and 20 core offences PROPERTY OFFENCES

1 Burglary: domestic burglary*; commercial burglary*2. Vehicle related theft: theft of vehicle*; attempted theft of a vehicle; theft from outside vehicle; theft from inside

vehicle; attempted theft from a vehicle3. Other thefts: from work; from school; shoplifting; theft from person*; other theft4. Criminal damage: to a vehicle; to other property

VIOLENT OFFENCES DRUGS

5. Robbery: of an individual*; of a business* 7. Selling drugs: Class A drugs*; other drugs6. Assaults: with injury*; without injury* denotes a serious offence

How many offend?Although a substantial minority of people do transgress at some point in their lives most onlydo so on a few occasions, committing relatively minor offences. Serious and pro l i f i co ffending among the general household population is extremely rare, and concentratedamong teenagers, especially males.

Lifetime offending● Overall, four in ten people said they had committed at least one of the 20 core

offences at some time in their lives. Miscellaneous thefts (e.g. from work, schooland shops) were most common, followed by assaults (split fairly evenly betweeninjury and no-injury incidents).

● About a fifth of lifetime offenders had only offended once; between 35 per centand 40 per cent had done so on four or more occasions.

Offending last year● Offending in the last year is far less common. One in ten people had committed a

c o re offence in the last year.1 P revalence levels were low for most off e n c ecategories, except for other thefts and assault (Figure 1a). Robbery and burglarywere extremely rare. Virtually all drug selling was to friends.

● Out of all 10-to 65-year-olds only four per cent had committed a serious offencein the last year; two per cent were prolific offenders. In all, five per cent wereserious or prolific, and one per cent were serious and prolific – there being someoverlap between the two.

Offending in England and Wales: First results from the 2003 Crime and Justice Survey

vi

1. Respondents were asked about offending in the 12 months prior to interview (interviews took place betweenJanuary and July 2003).

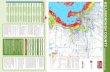

Figure 1a: Offending in the last year Figure 1b: Serious and prolific offending in the last year

● Overall, it is estimated that there were 3.8 million active (last year) off e n d e r saged between ten and 65. The number of serious or prolific offenders is farlower. There were an estimated 540,000 serious and prolific offenders. A further880,000 were serious but not prolific; 390,000 prolific but not serious.2

● A small group of offenders are responsible for the vast majority of off e n c e smeasured by the survey. While prolific offenders form only two per cent of thesample and 26 per cent of last year offenders, they account for 82 per cent of alloffences measured. These estimates are based on a sample of offenders in thegeneral population and exclude those in prison or other institutions, for example.Other research has also demonstrated that offending is highly concentrated.

Gender differences● A c ross most offence categories males were more likely to offend than females

(differences were not statistically significant for burglary and robbery). Overall,13 per cent of males had committed a core offence in the last year comparedwith seven per cent of females. Female offending is almost exclusively restricted toassault (with and without injury) and other thefts. Males are more fre q u e n t l yinvolved in a wider range of offences. The gender gap was smallest for assaults,though still males were almost twice as likely to have committed an assault.

vii

Executive summary

2. All these estimates, being based on a sample, have confidence intervals associated with them. The high and lowestimates are given in Tables 3.2 and A4.6.

● A half of all incidents committed by males were pro p e rty related, 21 per centwere drug selling offences, 17 per cent non-injury assaults, and 14 per cent moreserious violence. For females, non-injury assaults were a far higher proportion at31 per cent, drug selling a lower proportion at 11 per cent.

● Males were more likely to be serious or prolific offenders (Figure 1b).

Age differences ● The C&JS is unique among self-report offending studies in surveying a wide age

range. It supports other evidence that young people are more likely to be activeoffenders, at least for those offences covered.

● The peak rate of offending was among 14- to 17-years-olds (a third hadcommitted a core offence), followed by 12- to13-year-olds and 18- to19-year-olds(both a quarter).

● Taking account of gender and age, the highest rate of offending was among boysaged between 14 and 17: four in ten admitted a core offence in the last year.While girls offended less, they did so at a more even rate throughout the teenageyears – at around a fifth.

● Young males were also most likely to be serious and prolific offenders at around atenth. Among females serious and prolific offending remains under five per centfor all age groups.

● Those aged between ten and 17 and between 18 and 25 each accounted forabout a third of offences. Males aged between ten and 25 (14% of the sample)accounted for almost half (47%) of all offences committed.

● The majority of offences committed by juveniles are non-injury assaults or propertyoffences. Among those aged between 26 and 65, property offences were mostnumerous (62% of incidents). For 18- to 25-year-olds, drug selling was almost ascommon as property crimes (38% and 40%).

The number of offenders and offences dealt with by the Criminal Justice SystemThe C&JS asked people about contact they had had with the police and the courts, inrelation to any offence and also for ‘core’ offences. The results show that a substantialminority of offenders do have contact with the criminal justice system at some point,particularly the most serious. However, it also confirms that most offences are not formallysanctioned, though the sanction rate is relatively high for serious assaults.

● A quarter of those who had offended at some time in their lives had been arrestedat least once, a fifth had been to court charged with an offence, and 16 per centsentenced to a fine, community penalty or custody.

Offending in England and Wales: First results from the 2003 Crime and Justice Survey

viii

● Among serious or prolific lifetime offenders, about a third had had been arrestedat some time, around a quarter had been to court and just over a fifth given asentence (fine, community penalty or custody).

● The probability of sanction is lower when looking at the last year. Overall, six percent of last year offenders had been arrested in the period, with only one percent of all last year offences resulting in a court appearance. These figures willunderstate the sanction rate given delays in processing cases, but previous workhas also shown only a small minority of offences result in conviction.

● The probability of an offence being detected and proceeded against varied. Byfar the highest figure was for injury assaults, where about one in five resulted inpolice contact. The lowest figure was for selling drugs, where less than one in200 incidents resulted in police contact.

● Although, relatively few offences result in conviction, the criminal justice systemdoes bring to justice offenders responsible for many offences. The C&JS estimatesthat those convicted in the last year were responsible for a quarter of seriouso ffences re p o rted to the surv e y. This will understate the pro p o rtion of seriouscrime accounted for by those brought to justice since the survey excludes those incustody and will undercount those serving community penalties.

Offending patternsThe 2003 C&JS provides some information on when people begin and cease offending.However, this is somewhat limited by the cross-sectional nature of the survey; further sweepsof the survey will provide richer longitudinal information.

● Among all those who had offended at some point in their lives the mean age ofonset was 15. Male offenders had an average onset age of 15, female offenders16. However, there was considerable variation in age of onset. About ten percent of offenders first offended before the age of ten, while around a fifth onlyoffended for the first time at 18 or older.

● Shoplifting and, not surprisingly, theft from school started earliest. Drug sellinghad a relatively late onset – (mean age at first offence being 19).

● For non-active offenders, the average age when they last offended was 23,although a third had stopped offending before the age of 18. Female desistersstopped offending slightly earlier (mean age 21) than males (23). Many‘desisters’ had relatively short criminal careers.

● There was some evidence that serious and prolific offenders were more likely tos t a rt offending early and have longer criminal careers. Among active pro l i f i c

ix

Executive summary

o ffenders, for instance, the mean age of onset was 12, while for serious andprolific offenders it was 11.

Seriousness of offences To give an indication of the types of offences uncovered by the C&JS, last year offenderswere asked detailed questions about the last time they had committed each offence type (upto a maximum of six).

● Around seven in ten assaults involved the use of excessive force (force exceedinga grab or push); 58 per cent involved punching or slapping, 25 per cent kickingbut only six per cent hitting the victim with a weapon or object.

● While most incidents of damage and theft were relatively minor in cost terms, asignificant minority were serious. This was particularly the case with criminaldamage. A quarter of criminal damage incidents involved damage estimated atmore than £100, as against 9 per cent of thefts.

Victim characteristics● In three-quarters of incidents (excluding those directed specifically at businesses or

organisations) the offender already knew the victim(s) in some way (just over halfinvolving victims known well). Assaults and ‘other thefts’ were more likely to beagainst victims known to the offender. Only 20 per cent of violent incidents wereagainst strangers.

● Assaults committed by females and young people were more likely to involve avictim known well – about three-quarters did.

● In almost four in five assaults the victim was male. Nearly all assaults by maleswere against males. In assaults committed by females, the victim was more oftenmale than female, especially when the offender was older.

● Three-quarters of victims of assault were aged between ten and 25.

Co-offending● A quarter of offences involved one or more co-offender. Co-offenders most often

f e a t u red in vehicle-related thefts (62%) and criminal damage incidents (44%).Only about a fifth of violent offences and other thefts involved co-offenders.

● Most male offenders offended with other males, but only half of female offenderswhen they offended with others did so solely with females. Co-offenders tended tobe within the same age group as offenders and were usually aged between tenand 25.

Offending in England and Wales: First results from the 2003 Crime and Justice Survey

x

Motivations● Most offences measured by the survey were not planned but committed on the

spur of the moment: about eight in ten were. ‘Other thefts’ were most likely to beplanned.

● Reasons for committing offences varied considerably by offence type. Forexample assaults were mainly driven by being annoyed or upset with someone,while vehicle-related thefts often happened because the offender was bored orwanted a ‘buzz’. ‘Other thefts’ happened mainly because the offender wantedmoney or what was stolen.

● Motivations were generally similar for males and females, though in assaults, self-defence featured more for males than females.

Alcohol use● Overall, one in ten incidents were committed when the offender had been

drinking at the time of the incident, and two per cent when the offender had takenboth drugs and alcohol. Drinking was most common in relation to criminaldamage (40% of incidents were committed when the offender had been drinking,or drinking and taking drugs). It was also relatively common for vehicle-relatedthefts. The contribution of alcohol was, perhaps surprisingly, lower than this forassaults: in only 17 per cent of incidents of assault did the offender say he/shehad been drinking. This figure, however, rises to 37 per cent of assaultscommitted by males aged between 16 and 25.

Drug use Previous research among offenders in the criminal justice system has shown drug use to bean important contributory factor in offending. However, the C&JS shows drug use is rarely afactor, even less so than alcohol, when it comes to offending in the general population. Thisreflects the types of offender (often minor) and drug user (often recreational) picked up in thegeneral population. Prolific drug offenders are unlikely to be picked up.

● Overall, five per cent of incidents were committed when the offender had takendrugs (or both drugs and alcohol). Offenders had most often used drugs at thetime of vehicle-related thefts (11%). Having taken drugs was generally moreevident in property crimes than in violence.

● For offences as a whole, two per cent of offenders said that being under theinfluence of drugs contributed to the offence. The influence of drugs was higherfor shoplifting than other offences, at eight per cent. The figure was also relativelyhigh (5%) for vehicle-related thefts.

xi

Executive summary

● Another question asked current drug users whether they had committed a crime tobuy drugs in the last year. Overall, just one per cent of all drug users and one percent of all last year offenders had committed a crime to buy drugs (0.2 per cent ofthe whole sample). For drug users who had committed a ‘core’ theft offence in thelast year, the figure rises to four per cent.

The relevance of sanctions● In nearly thre e - q u a rters of incidents, offenders felt it unlikely they would get

caught. Similarly, offenders were not usually worried about the consequences ifthey were caught. There were some differences across offence type. For instance,a higher proportion of those involved in vehicle-related thefts thought they werelikely to get caught and were concerned about it.

● The question arises as to why people who think it likely they will be caughtcommit the offence at all. A higher proportion of those thinking they were likely toget caught said they offended because of revenge, were annoyed by someone,or were acting in self-defence. These spurs to offending, then, seem to serve tooverride an immediate concern about being caught.

● The most common reasons given for ceasing to offend were ‘I knew it was wrong’and ‘I grew up, settled down’. This suggests a natural process of maturation. Thepercentages giving these responses varied by offence type but ranged from abouthalf for those selling Class A drugs to over 80 per cent for those who hadcommitted criminal damage.

● However, a substantial minority of those who had in the past committed burglary,v e h i c l e - related thefts, shoplifting, or drug selling said that being caught by thepolice, or fear that this could happen, was a reason why they stopped. Theimpact of official sanction in deterring offenders, then, appears to be relativelystrong, but certainly not the main factor.

Methodological notesThe 2003 C&JS had a random probability sample design. The main sample comprised10,079 people aged from ten to 65 living in private houses in England and Wales. Thenumber of young people was boosted to around a half (N=4,574) as this is a group ofkey interest (weighting was applied to correct for this in analysis). In addition there was abooster sample of 1,882 non-white respondents. This report focuses on the main sampleonly. Results for black and minority ethnic groups will be available in due course. Theresponse rate for the main sample was 74 per cent. Fieldwork (by BMRB Social Researchand the National Centre for Social Research) took place between January and July2003. The first part of the interview was interviewer administered; the second part

Offending in England and Wales: First results from the 2003 Crime and Justice Survey

xii

including the more sensitive questions was self-administered. Computer assistedtechniques were used. The offending count module used Audio CASI whereby thequestions and responses are pre - re c o rded and listened to by the respondents thro u g hheadphones, as well as being presented on the computer screen. This was to make iteasier for those with literacy problems to take part.

While the C&JS is state of the art in many ways it is still subject to the followinglimitations that should be considered in interpreting the findings:

Sample coverage – the C&JS covers the general household population. By definition itexcludes those resident in institutions, including prison, and the homeless. As such it willexclude some of the highest rate offenders.

Sampling error – the estimates are from a sample and are therefore subject to samplingerror. That is they may differ from the figure that would have been obtained if the wholepopulation of interest had been interviewed. The degree of this error can be estimated.Throughout this report the differences identified are significant at the five per cent leveli.e. we are 95 per cent certain that the difference exists in the population.

Non response bias – although the response rate is high for a large-scale generalhousehold survey, it may still be that non-respondents differed in key respects from thosewho took part. Other research suggests that non-respondents tend to be more delinquentthan those who respond.

Accuracy of responses – respondents may be unwilling or unable to provide honest andaccurate answers and this may vary across different groups.

The futureThe plan is for the 2003 C&JS to be followed by three further sweeps (the 2004 surveyfieldwork has been completed). Each will be restricted to 5,000 young people, with thesample comprising both a panel and a fresh element. Each year those aged from ten to25 at first interview will be followed up for re-interview (the panel), while new ten- to 25-y e a r-olds will ‘top up’ the sample to ensure it remains re p resentative. Future sweeps,therefore, will not only provide data on trends in youth offending but also longitudinalevidence on the development of offending ‘careers’.

xiii

Executive summary

1 Introduction

This report presents the first findings from the 2003 Crime and Justice Survey (C&JS), a newsurvey commissioned by the Home Office. A sample of around 12,000 people aged fromten to 65 living in private households in England and Wales were interviewed betweenJ a n u a ry and July 2003. The survey collected information on the extent and nature ofoffending, drug and alcohol use, attitudes to and contact with the criminal justice systemand experiences of victimisation.3 This report focuses on offending behaviour. Respondentsw e re asked about offending in their lifetime and in the last 12 months. This is the firstnationally representative self-report offending survey to cover such a wide age range.

Survey aimsThe main aims of the survey were to provide:

● A measure of the number of offenders in the general household population inEngland and Wales and the offences they commit, including those who will nothave been processed by the criminal justice system. The coverage of offendingbehaviour is discussed later.

● An estimate of the proportion of offenders and offences that come to the attentionof criminal justice agencies.

● An estimate of the proportion of active offenders who are young people and theproportion of crime they commit.

● I n f o rmation on the nature of offences committed and, in part i c u l a r, offender motivations.● Information on patterns of drug use and links to offending. ● Data to identify the risk factors associated with the onset and continuation of

offending and drug use, and factors associated with desistence.

Although the C&JS measures legally proscribed offences and the terms ‘offender’ and‘ o ffence’ are used throughout this re p o rt, it should be borne in mind that some of theincidents re p o rted to interviewers, while technically illegal, will be relatively minortransgressions. This is discussed further below.

The C&JS was commissioned by the Home Office as part of a programme of surv e y sdesigned to measure levels of self-re p o rt offending and drug use among various groups in the

1

3. The British Crime Survey (BCS) is the national victimisation survey for England and Wales. However, because theBCS only covers people aged 16 and over, a module on victimisation was included in the C&JS to measure theexperiences of children (see Wood, 2004).

population. It covers the general household population in England and Wales. By design, itexcludes those serving custodial sentences at the time of fieldwork and it will pick up few whoa re serving community penalties. There f o re two other self-re p o rt offending surveys have alsobeen undertaken. One is of those in custody – the 2000 Prisoner Criminality Survey (Budd e ta l., forthcoming). The other covers those serving sentences in the community – the 2002Community Penalties Criminality Survey (Budd et al., forthcoming). A Home Office surv e yamong arrestees has also been developed. To g e t h e r, this suite of surveys help build a betterp i c t u re of offending. However, there are important methodological diff e rences between themand direct comparisons will need to be treated with caution.

Crime and Justice Survey designThe 2003 C&JS had a random probability sample design. The main sample comprised10,079 people aged from ten to 65, just under a half (N=4,574) of whom were agedbetween ten and 25. Young people were over-sampled because they attract particular policyand criminological interest on account of evidence that they are most likely to offend and useillicit drugs. The C&JS, which is being repeated annually, will also be used to monitor levelsof youth crime over time. A sufficiently large sample size was there f o re re q u i red for ro b u s testimates. Weighting was applied to correct for this over-sampling in analysis.

I m p o rt a n t l y, though, the survey covered a wider age range than usual in self-re p o rto ffending surveys, which normally focus on young people. This allows us to identify theproportion of crime for which young people are responsible, and how offending patternsdiffer with age.

The C&JS also included an additional ‘booster’ sample of 1,882 black and minority ethnicrespondents to allow separate examination of their experiences. Results will be re p o rted later.

The size, breadth and representativeness of the sample make the C&JS a unique source ofdata on offending in England and Wales. Moreover, it was carefully designed to take onboard lessons from previous self-report offending surveys and incorporates some innovativetechniques to improve the quality of the data collected (see Chapter 2).

LimitationsAlthough the C&JS is ‘state of the art’ in many ways, it remains subject to some limitations.The main ones are:

● Sampling error – based on only a sample of the population, estimates are subject

Offending in England and Wales: First results from the 2003 Crime and Justice Survey

2

to sampling error. That is the results obtained may differ from those that would beobtained if the entire population had been interviewed. Statistical theory enablesus to calculate the degree of erro r. Throughout this re p o rt diff e rences betweengroups are statistically significant at the five per cent level (i.e., it is 95 per centcertain that the difference exists in the population) unless otherwise specified.

● Non-response bias – despite the high response rate (74% for the main sample), itmay be that non-respondents differ in key respects to those who took part. Forexample, those with particularly chaotic lifestyles might be difficult to contact andmore likely to refuse. There is evidence from other research that non-respondentstend to be more anti-social than respondents (see Farrington et al., 1990).

● Accuracy of responses – respondents may be unable or unwilling to pro v i d ehonest and accurate responses, and this may vary across diff e rent gro u p s .Respondents were asked at the end of the interview how honest they had beenwhen asked about offending and drug use. The results are encouraging with 97per cent saying they answered all offending questions honestly (see Appendix B).

● Incomplete coverage of off e n c e s – the ‘core offences’ (see below) focus onm a i n s t ream offences such as ro b b e ry, assault, burg l a ry, thefts of and fro mvehicles, and other miscellaneous thefts. But the survey does not cover all offences(e.g. sexual offences4).

● Exclusions from the sample – people in institutions (including prisons), or who arehomeless are not covered.5 Also, a random general population survey will pick uprelatively few ‘serious’ offenders because of sample size constraints.

Measuring offendingThe C&JS covers a range of behaviours from minor anti-social and delinquent behaviours,such as truancy, under-age drinking and fare evasion, to serious criminal offences, such asro b b e ry and burg l a ry. The inclusion of low-level anti-social behaviour was deliberate. Itsextent is of interest in its own right. Evidence indicates that young people are predominantlyinvolved in less serious delinquent behaviour (MORI, 2003). Moreover, the inclusion of lessserious behaviours can act as a ‘softener’ for questions about more serious transgressions.

3

Introduction

4. It would be impossible for a survey to cover all offence types adequately. Sexual offences, in particular, wereexcluded because legal advice suggested that assurances of confidentiality could not be given if such offenceswere covered.

5. A study to explore the feasibility of including the institutional population in the C&JS concluded that it would bedifficult, and that its inclusion would not impact on overall estimates of offending and drug use. Since only asmall proportion of the population are in institutions, rates for this group would have to be extremely high fortheir inclusion to have serious impact on population estimates. A re p o rt of the study can be found athttp://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/offending1.html.

The focus of this report, however, is on the ‘core’ criminal offences covered by the survey( ro b b e ry, assault, burg l a ry, criminal damage, thefts of and from vehicles, othermiscellaneous thefts and selling drugs). For these offences, information was collected on thenumber of incidents committed in the last year; the proportion that came to the notice ofjustice agencies, and the circumstances of the incident, such as why it happened and theinvolvement of co-offenders.

The C&JS also covered some other forms of potentially more serious offending includinghandling stolen goods, various forms of fraud,6 and technology crimes such as sendingv i ruses, hacking and illegally downloading material. Far less information was collectedabout these off e n c e s .7 They are there f o re not included in the ‘core’ offences’ analysispresented in this report, though Chapter 3 presents some results.

The ‘core’ offences all pertain to legal offences, but even so these will range in seriousness.They will inevitably include – and are meant to include – incidents that, while technicallycriminal, are relatively trivial and unlikely to provoke much in the way of a formal responseif they were known about (e.g. a low value theft from the workplace). The result is that arelatively large pro p o rtion of respondents will admit to having committed some type ofoffence at some time. This offers scope for the challenge that the C&JS (like other self-reportoffending surveys) fails to differentiate minor offending from more serious criminality, givingan inflated estimate of the number of ‘real’ offenders. This challenge, though, can be takentoo far. This is because:

● Minor transgressions can run alongside more serious offending. ● Exploring the full range of offending behaviour can throw light on what

d i ff e rentiates serious and prolific offenders from those who only occasionallytransgress.

● Although many individual offences may themselves be trivial in terms of monetaryloss say, they can add up to significant social and economic costs at thea g g regate level if a significant number of people commit them, even if onlyoccasionally.

Chapter 2 discusses the C&JS measure of offending in more detail.

Offending in England and Wales: First results from the 2003 Crime and Justice Survey

4

6. Tax evasion, unauthorised use of a credit card, fraudulently claiming social security benefits and work expenses,and false insurance claims.

7. Many of these questions were only asked of respondents aged 18 and over. They were asked if they hadcommitted the offences in the last year. They were not asked exactly how many times they had done so, norabout any resulting contact with official agencies.

For a general discussion of the advantages and disadvantages of self-re p o rt data, seeFarrington et al., 1996, Hindelang et al., 1981 and Elliott et al., 1989.

The future The plan is for the 2003 C&JS to be followed by three further annual sweeps. Each will berestricted to 5,000 young people, with the sample comprising both a panel and fre s helement. Each year those aged from ten to 25 at the time of their first interview will befollowed up for re-interview (the panel), while new respondents aged from ten to 25 will beintroduced to ‘top up’ the sample to ensure that it remains representative.8

This innovative design allows the C&JS to better meet various information needs. The panelelement will give longitudinal data to examine the development of offending ‘careers’ andidentify factors that contribute to onset, continuation and desistence. At the same time, thesample will remain re p resentative thus providing robust trend data on the prevalence ofyouth offending and drug use in England and Wales.

Structure of reportChapter 2 provides an overview of self-report methodology and the design of the C&JS.

Chapter 3 presents findings on the prevalence of offending on a lifetime and last year basis. Itprovides estimates of the number of offences committed and the proportion committed byyoung offenders.

Chapter 4 examines levels of serious or prolific offending and identifies the pro p o rtion ofcrime accounted for by prolific offenders.

Chapter 5 identifies the proportion of offenders and offences that come to official notice.

Chapter 6 discusses patterns of offending in terms of age of onset, duration and reasons fordesistence.

Chapter 7 outlines the nature of offences committed and comments on offender motivations.

Chapter 8 provides an overview of the findings.

5

Introduction

8. Fieldwork for the 2004 C&JS is taking place between January and July 2004. The aim is to achieve about3,300 panel interviews and 1,700 fresh interviews.

R e p o rts covering the other main topics in the C&JS (and the experiences of black and minorityethnic groups) have been published or will appear in due course. The main topics are:

● Anti-social behaviours (Hayward and Sharp, 2004);● Fraud and ‘technology’ offences committed;● Drug and alcohol use;● Victimisation among children under the age of 16 (Wood, 2004); and● Attitudes towards crime and the criminal justice system.

Offending in England and Wales: First results from the 2003 Crime and Justice Survey

6

7

2 The Crime and Justice Survey in context

This chapter discusses how the Crime and Justice Survey (C&JS) adds to our understandingof offending and crime. It discusses other sources of information and how self-re p o rto ffending studies provide important complementary data. The chapter also outlines thedesign of the survey (there are further details in Appendix B).

Administrative statistics on offendersMost information on offending is derived from the processing of known off e n d e r s. Forexample, there is information on the number of people cautioned or convicted, by offence,and the number of offenders in custody or serving a community sentence. Most data onoffenders provide a snapshot at a particular point in time, but no sense of how individualcriminal careers develop. An exception is the Home Off i c e ’s Offenders Index (OI), adatabase of the criminal conviction history of individuals convicted since the 1960s. Forexample, the OI shows that 33 per cent of males and 9 per cent of females born in 1953had a conviction for a standard list offence by the age of 46.9 This information isinvaluable, but nonetheless captures only offending which is officially sanctioned. Manyoffences (and offenders) are never formally processed.

Police statistics on crime The traditional measure of the amount of crime committed comes from figures of offencesrecorded by the police. These allow a fine-grained picture of the distribution of crime acrossdifferent areas, but the count is limited to crimes that the police know about and that theyrecord. Routine police figures say little about offenders.

Victimisation surveysEvidence on the extent to which official statistics underestimate the ‘true’ level of crimecomes from victimisation surveys. These ask a sample of the population to recall incidents ofcrimes against them or their household in a specific time period. They give little insight intothe number of i n d i v i d u a l o ffenders involved, since some may commit many crimes.Nonetheless victimisation surveys are important in capturing better the ‘real’ amount ofcrime experienced, and how this changes over time – which itself may indicate changes inoffending levels.

9. For further information on the Offenders Index see www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/offendersindex1.html.

The British Crime Survey (BCS) is the national victimisation survey for England and Wales,and has provided victimisation estimates over more than twenty years.10 The BCS indicatesthat there were 12.3 million offences against individuals and households in 2002/03, lessthan half of which were re p o rted to the police (Simmons and Dodd, 2003). For off e n c etypes that can be compared with police figures, the BCS registers nearly three times asmany as recorded by the police.

Self-report surveys of offending S e l f - re p o rt offending methodology first gained currency in the 1950s and has sinceflourished as a tool to understand the extent and nature of criminal and delinquentbehaviour. The methodology is based on the simple premise of directly asking people abouttheir offending behaviour.

T h e re have been several small-scale, localised surveys in the United Kingdom. The bestknown is the Cambridge Study of Delinquent Development – a unique pro s p e c t i v elongitudinal study that has followed up a sample of males from the age of eight into their latef o rties. It has been an invaluable source of information on the development of delinquent andcriminal careers and the factors associated with onset and desistence (Farrington, 2003a).Several other local area surveys have emerged in recent years, including the Edinburgh Studyof Youth Transitions and Crime (Smith et al., 2001; Smith and McVie, 2003) and theP e t e r b o rough Youth Study and Adolescent Development Study (Wi k s t rom, 2003).

In terms of nationally re p resentative surveys, the Home Office has previously commissioned the1998/1999 Youth Lifestyles Survey (YLS) (Flood-Page et al., 2000), the 1992/1993 Yo u t hLifestyles Survey (Graham and Bowling, 1995), and a survey in 1983 covering juveniledelinquency (Riley and Shaw, 1985).1 1 Each has been a cross-sectional survey of a sample ofyoung people in England and Wales. The 1998/1999 YLS found that almost a fifth of 12-to30- year-olds had committed one or more offence in the 12 months prior to interv i e w.

The Youth Justice Board (YJB) commissions an annual Youth Survey to examine youngpeople’s experience of crime, both as offenders and victims. The survey has been conductedsince 1999. The 2003 survey included a sample of nearly 5,000 11-to 16-year-olds inm a i n s t ream schools and a sample of about 600 pupils excluded from school. Around aquarter (26%) of mainstream pupils had committed at least one of the offences asked about

Offending in England and Wales: First results from the 2003 Crime and Justice Survey

8

10. The British Crime Survey only covers crimes against households and individuals aged 16 and over. It does notcover offences against commercial or public bodies, children, or those not resident in private households. Itcovers most ‘mainstream’ offences but is not comprehensive – e.g. it does not cover homicide or fraud. Furtherdetails about the BCS are at: http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/bcs1.html.

11. F u r ther details on the Youth Li fes ty les Sur vey including links to re p o r ts can be found a t:http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/offendingyls.html.

in the 12 months prior to interview. The figure was far higher among excludees at 60 percent (MORI, 2003).

The International Self-Report Delinquency Study was undertaken in 1991/1992 covering 13countries, including England and Wales. It examined cross-national diff e rences in thep revalence of delinquency and aimed to identify any variability in factors related to it.Relative to the four other countries with similar sample designs, England and Wales had alower level of overall delinquency (38% of those sampled had committed a delinquent act inthe last year), although the comparability of the surveys remains in some doubt (Junger-Taset al., 2003).12

These studies have consistently demonstrated that delinquency and offending is fairlyw i d e s p read, although serious or persistent offending is much less common. These patterns are tobe expected given that self-re p o rt surveys typically include many relatively trivial incidents thatwould often be considered marginal in terms of ‘real’ criminality. Farrington (2003b)summarises key findings from self-re p o rt studies on criminal careers and the causes of offending.

The Crime and Justice SurveyThe current Crime and Justice Survey builds on previous national self-report studies. But ithas been designed to provide more information than other studies and includes innovativedata collection techniques to improve the quality of the data collected. A considerableamount of feasibility work was undertaken before the full survey was commissioned.13 Theacademic community was extensively consulted about the design of the survey.

The important features of the 2003 survey are:

● an extended age range from ten to 65, though with a sufficient number of youngpeople to provide robust estimates;

● inclusion of a booster sample of people from black and minority ethnic groups;● a large sample of around 12,000 respondents in total;● a sophisticated questionnaire designed to give a better measure of offending than

hitherto available;

9

The Crime and Justice Survey in context

12. The Netherlands, Portugal and Switzerland all had nationally re p resentative samples. The last year prevalence ratesw e re 62%, 57% and 70% re s p e c t i v e l y. Spain, using a large stratified urban sample, had a last year rate of 59%.

13. Two feasibility studies were undertaken – one to test the validity of the self-re p o rt method for the generalpopulation (BMRB Social Research); the other to investigate the feasibility of conducting the survey among theinstitutional population (Office for National Statistics). Professor David Farrington was commissioned tosummarise what had already been learnt from self-report offending surveys and to identify information gaps thenew survey could fill. Professor Peter Lynn was commissioned to consider methodological issues. All reports fromthe feasibility phase are available at: http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/offendingcjs.html.

● use of Audio-CASI to ensure respondents with literacy problems could participate;and

● a sample design to allow the future collection of longitudinal data for youngpeople.

Age rangeMany previous studies have focused on adolescence and young adulthood. The YLS onlycovered 12- to 30-year-olds, while the MORI Youth Survey conducted on behalf of the YouthJustice Board covers young people aged from 11 to 16.

The 2003 C&JS is much wider in coverage, sampling those aged from ten to 65. We canthus examine early development of offending and how it changes in later life, on which thereis little self-re p o rt evidence. The extended age range also enables us to estimate thep ro p o rtion of crime committed by young people. While future sweeps of the survey will focuson young people, the baseline data covering the wider age range fills a key knowledge gap.

Sample size and coverageMany self-re p o rt offending surveys have relatively small sample sizes, which placesconstraints on the robustness of estimates. The 2003 C&JS had a comparatively large mainsample of 10,079: 4,574 of whom are aged from ten to 25.

The questionnaire and its administrationThe questionnaire was developed in consultation with the research, academic and policycommunities. The instrument was thoroughly tested before the full surv e y. Cognitivei n t e rviews tested comprehension, understanding and re l e v a n c y, including among thoseunder the age of 16 and people known to have been involved in crime and drug use.

The interview included interv i e w e r- a d m i n i s t e red and self-administered sections, both ofwhich used computer-assisted techniques. Computer programmes allow the development ofsophisticated questionnaires with complex routing and customised ‘text fills’. CASI(Computer- Assisted Self-Interviewing), whereby respondents read the question and answercodes from the computer screen and enter their own answers, was used for the mostsensitive questions about offending, alcohol and drug use, and family and educationalexperiences. CASI has the advantage over paper and pencil techniques of ensuringrespondents answer all relevant questions in the correct order and prevents them pre -

Offending in England and Wales: First results from the 2003 Crime and Justice Survey

10

empting later questions. There is also some evidence that CASI results in higher admittanceof ‘deviant’ behaviours such as drug use and offending (Percy and Mayhew, 1997; Flood-Page et al., 2000; O’Reilly et al., 1994).

An important innovation on the C&JS was the use of Audio-CASI for the key self-a d m i n i s t e red sections. With Audio-CASI respondents listen to pre - re c o rded questions andanswer categories through headphones and then enter their response into the computer.Audio-CASI has the advantage over normal CASI of permitting those with re a d i n gd i fficulties to participate without interviewer assistance – thus pre s e rving confidentiality.Audio-CASI had not previously been used in a large-scale household survey in England andWales, but was adopted for the C&JS because of the need to interview children and thep a rticular sensitivity of the questions. It proved extremely successful in practice. Furt h e rdetails about Audio-CASI are in Appendix B.

Measuring offendingThe main purpose of the C&JS is to provide more robust measures than hitherto available ofthe prevalence of offending and the number of offences committed. Key to this was carefuldesign of the offence screener questions to avoid some problems identified in other surveys.

Offence specific screenersAlthough the C&JS covers a wide range of anti-social and delinquent behaviours, only 20‘core’ offences were asked about in detail. These core offences fall into seven broad offencecategories: burglary; vehicle-related thefts; other thefts; criminal damage; robbery, assault,and selling drugs (Chapter 3 gives more detail).

The 20 core screener questions (listed in Appendix C) were designed to reflect the legaldefinition of offences but used simple descriptive language. Some surveys opt for fewer,broader screeners with follow-up questions to find out the types of offence committed. Thedanger with this approach is that the screener is inevitably ‘looser’ and allows gre a t e rambiguity as to what should be reported. Although the C&JS used tightly worded ‘screener’questions to measure offending it may still be that some incidents re p o rted would notnecessarily meet the criteria of an offence if they became known to the police. Respondentswere asked details about the ‘last’ incident of each type reported to try and assess if thiswas a problem.14 There was no evidence that respondents were erroneously reporting non-criminal incidents though, as already discussed, the survey inevitably picks up somerelatively trivial incidents.

11

The Crime and Justice Survey in context

14. Respondents could be asked these detailed follow up questions about up to six offence types, with the mostserious offence types being given the highest priority.

Respondents were first asked if they had ever committed each of the respective off e n c e seven if it was a long time ago. Those who had committed an offence were then asked howmany times they had done so, and their age at the first and last (or only) incident.Respondents were only asked if they had offended in the last 12 months if this could not bea s c e rtained from the age information. The ordering of the questions was designed toencourage respondents to provide honest answers. It was felt that simply asking ‘cold’ aboutoffending in the last year could discourage respondents from being honest.15

For all offence types admitted to respondents were asked how many such incidents resultedin police contact, a court appearance and a conviction. This was to allow robust estimatesof the pro p o rtion of offences resulting in contact with the criminal justice system (seeChapter 5).

Avoiding double countingA common problem in self-report surveys is double counting of incidents, particularly wherea series of offence screeners are used. If questionnaires are inappropriately designed,respondents can be misled into reporting a single incident at more than one question. Thiswas addressed in the C&JS by ensuring that offence screener questions were suff i c i e n t l yspecific, and logically ord e red. Where appropriate, instructions were also given torespondents, for instance through the use of the term ‘Apart from anything else you havealready mentioned’.

The questionnaire was designed to try and eliminate an offender reporting a single offenceon more than one occasion. However, it remains the case that incidents may be double-counted if, by chance, co-offenders are picked up in the sample. For example, if the sampleincludes two individuals who offend together and they both report the same incidents thenthe count of incidents will be inflated. In practice, though, it is unlikely that there will bemany co-offenders included in the survey.

Counting the number of offencesSome previous self-re p o rt studies, including the Youth Lifestyles Surv e y, have askedrespondents to provide banded frequencies for the number of offences committed in the lasty e a r. This has been justified on the grounds that prolific offenders can have diff i c u l t yrecalling the exact number of offences they have committed. However, it means that surveyanalysts have to put their own figure on the number of offences committed – which poses aparticular problem with a response category of “ten or more” for instance. The C&JS opted

Offending in England and Wales: First results from the 2003 Crime and Justice Survey

12

15. This decision was based on discussions with the survey contractors and feedback from the feasibility study andcognitive interviews.

to use a banded approach for ‘lifetime’ offending, but asked respondents to give an ‘exact’count of offences in the last year. This means that the range of responses is not artificiallyconstrained and allows a finer differentiation between types of offender. However, it shouldbe acknowledged that some respondents, for various reasons, may overestimate orunderestimate the number of offences committed.

It is also important to note that the C&JS grossed up estimate of the number of off e n c e scommitted by offenders is a count of individual instances of offending rather than of crimeevents. In a single crime event, for example, two offenders might be involved which wouldequate to two individual instances of offending. This is further discussed in Chapter 3.

Reference periodI n t e rviews took place between January and July 2003. The ‘last year’ re f e rence periodpertained to the 12 months before interview.16 This was reiterated at each relevant questionto ensure respondents understood the importance of the re f e rence period. During thedevelopment phase the use of a paper calendar was tested to see if it helped respondentsaccurately recall events in the re f e rence period. Feedback from respondents andinterviewers suggested that this was not a particularly useful tool for most respondents andbecause it added considerably to interview length this was not used in the main stage.

Comparisons with other data sourcesWhile the C&JS was developed with reference to other self-report offending surveys, it wasnot designed to be directly comparable with them. Nonetheless, some comparisons aremade where relevant. Comparisons are also made with other data sources, including theBritish Crime Survey and the Offenders Index, though again these comparisons areproblematic and the results should be treated with due caution.

13

The Crime and Justice Survey in context

16. Respondents were asked to think about the 12 months since the 1st of [month] 2002. So those interviewed inF e b ru a ry were asked about the 12 months since the 1st of Febru a ry 2002. The re f e rence period there f o re diff e re ddepending on the month of interv i e w, but all offences would have fallen in 2002 or January to July 2003.

15

3 The extent of offending

This chapter presents findings on overall patterns of offending. (Chapter 4 examines howwe can differentiate serious or prolific offenders; Chapter 7 looks at the nature of offencesreported to the survey.17) The focus is on the 20 core offences that were covered in mostdetail to provide a measure of the frequency and count of offending. These offences fallunder seven broad offence categories:

● burglary (of domestic and commercial properties); ● vehicle-related thefts (thefts of and from a vehicle, including attempts); ● other thefts (including from place of work or school, shoplifting, thefts from the

person and other thefts);● criminal damage (to a vehicle and other property); ● robbery (of an individual or business); ● assault (with and without injury); and ● selling drugs (Class A and other drugs).18

While these are all legal offences, some respondents will inevitably, and quite corre c t l y,re p o rt incidents that are relatively trivial, such as theft of a low-value item from work.Moreover, based on a random sample of the household population, the C&JS will inevitablypick up a relatively small number of high rate and serious offenders. Chapters 1 and 2discussed these issues in more detail. Suffice it to say they need bearing in mind ininterpreting the results.

The prevalence of lifetime offending The C&JS estimates that just over four in ten (41%) ten-to 65-year-olds living in privatehouseholds in England and Wales had committed at least one of the 20 core offences intheir lifetime. Males were far more likely to commit an offence (52%) than females (30%).

Figure 3.1a shows the percentage of respondents admitting to at least one incident withinthe seven diff e rent offence categories. Across all offences, males were significantly morelikely to be offenders than females. The only exception to this was for robbery which wasparticularly rare (less than 0.5% of respondents admitted to it).

17. Chapter 7 is based on detailed questions about the 'last' incident of up to six offence types committed. The restof the report pertains to all offences reported at the 20 'core' screener questions.

18. The term drug selling is used as opposed to drug dealing because this more closely fits with the offence screenerquestions which ask about selling. Many incidents involved selling drugs to friends.

Among both males and females ‘other theft’, comprising theft from the workplace, theft fromschool, shoplifting, theft from a person and other thefts, was most common, followed byassaults (including those resulting in no injury to the victim). About a quarter of males and atenth of females had at some time assaulted someone in such a way that they were injured.Lower proportions admitted other offences. Table A3.1 in Appendix A shows the results forthe 20 core offences.

There are difficulties in interpreting patterns in lifetime prevalence by age. Older people willhave had more time in which to offend, although at the same time they may understate theiro ffending as incidents further back in time are more likely to be forgotten or evendeliberately suppressed if the person no longer views himself/herself as an off e n d e r.Cognitive testing indicated that children were more likely than adults to respond literally. So,for example, a child who stole a small item from a school friend would admit to it, while anadult who had committed the same act many years ago would not - rationalising that it didnot constitute a crime. With these caveats in mind Table A3.2 shows the results. Everoffending is highest among teenagers and gradually declines thereafter, suggesting that theprobability of forgetting or concealing incidents does increase with age.

Frequency of lifetime offending For each offence, offenders were asked how often they had committed it in their lifetime.(They could say whether it was only once, two or three times, or more often.) For most of theindividual core offences a substantial proportion – between around 40 and 65 per cent –had only committed them once (Table A3.3). Theft from the workplace, selling drugs andnon-injury assaults were more frequently committed, particularly selling drugs. Almost four inten of those who had sold drugs had done so four or more times in their lifetime. Soalthough relatively few people admitted to selling drugs, those who did had done so morefrequently than was the case for other offences.

While it is not possible to derive an exact count of the number of offences committed, theindications are that almost a fifth (17%) of lifetime offenders had only offended once, whilebetween 35 per cent and 40 per cent had offended on four or more occasions.19

The remainder of this chapter focuses on offending during the 12 months prior to interview.

Offending in England and Wales: First results from the 2003 Crime and Justice Survey

16

19. Figures depend on whether one selects two or three as the figure for the count of those who committed eachoffence “two or three times”.

The extent of offending

Figure 3.1a Percentage ever offending, Figure 3.1b Percentage offending in by sex last year, by sex

The prevalence of offending in the last year Ten per cent of ten-to 65-year-olds had committed at least one of the 20 offences coveredduring the 12 months prior to interview.20 Again, males were more likely to have offended(13%) than females (7%). Prevalence levels were low for most offence categories (Figure3.1b). Robbery and burglary were extremely rare. The most common offences were assault(5.4%) and other thefts (4.7%). Thus, while other thefts were somewhat more common thanassaults on an ever basis, the reverse holds for last year offending. Similarly drug selling issomewhat more prominent in the last year picture than the ever picture, particularly formales. These changing patterns may well reflect the youthful nature of last year offending(see below), which is more driven by assaults and selling drugs. (Table A3.1 provides fullerdetails of lifetime and last year offending rates for the 20 core offences.)

Gender differences Previous self-report offending studies have consistently shown that males are more likely too ffend than females – although the gender gap varies according to the types of off e n c econsidered. The 1998/1999 Youth Lifestyle Survey (covering 12- to-30-year-olds) found that

17

20. Interviews took place between January and July 2003. Respondents were asked to think about the 12 monthssince the 1st of [month] 2002. So those interviewed in February were asked about the 12 months since the 1stof February 2002. The reference period therefore differed depending on the month of interview, but all offenceswould have fallen in 2002 or January to July 2003.

26 per cent of males had committed an offence in the previous 12 months, compared with11 per cent of females (Flood-Page et al., 2000). Conviction data shows a greater genderdifference, with males between the ages of ten and 45 being about four times as likely tohave a conviction as females (Prime et al., 2001).

The C&JS results are in line with these previous findings. Overall, males were almost twiceas likely to commit an offence in the last year as females (13% versus 7%). Among 12- to30-year- olds the figures were 25 per cent versus 14 per cent – similar to the 1998/99 YLSdespite the differences in the offences covered and survey design.

Females were significantly less likely to commit all offences categories, with the exception ofburglary and robbery which was extremely rare for both males and females. The degree ofthe gender difference varied somewhat across offences, overall being smallest for assaults.This finding, though, was mainly driven by offending patterns among 18- to 25-year-olds.For young people aged between ten and 17 the gender differential was least apparent for‘other thefts’, followed by assault.

Age differencesThe burden of previous evidence has also been that younger people commit most crime,though again the age gap varies by source and offence type. The C&JS is unique amongnational self-re p o rt offending studies in surveying a wide age range. It confirms thato ffending peaks among younger people. Around a third of 14- to 17-year-olds hadoffended in the last year, and about a quarter of 12- to 13-year-olds and 18- to 19-year-olds(Table A3.5).21

Age and genderT h e re are some diff e rences in offending patterns in the C&JS when age and gender arelooked at together. Among males, offending peaks between the ages of 14 and 17 witha round 40 per cent offending in the previous 12 months. Rates are significantly loweramong 12- to 13-year-old (25%) and 18- to 19-year-olds (29%). There is less fluctuationthrough the teenage years for females with the prevalence of offending remaining at arounda fifth between the ages of 12 and 19 (Table 3.1).

Offending in England and Wales: First results from the 2003 Crime and Justice Survey

18

21. The C&JS includes thefts from the workplace and from the school. The opportunity to commit these offences ishighly related to age. Excluding these offences reduces the prevalence of offending among all age groups butdoes not alter the pattern – with offending still peaking among 14- to 17- year-olds (see Table A3.5).

The extent of offending

These results broadly mirror those from other sources. Administrative data, for instance,show that the peak age for cautions and convictions in 2002 was 15 for females and 19for males (Criminal Statistics, 2002). In the 1998/1999 YLS, the peak age of offendingwas also lower for females (14) than for males (18). Given diff e rent age/off e n d i n gtrajectories, the male to female ratio thus varies with age.

Types of offence T h e re are also some diff e rent patterns in the types of offence committed by males andfemales of different ages (Table 3.1). The main features are below. Property offences are alltheft offences and criminal damage. Violent offences are all assaults and ro b b e ry, withresults essentially reflecting the former since the prevalence of ro b b e ry is so low. Moreserious violence include only assaults with injury and ro b b e ry. Tables A3.4 and A3.5present more detailed results by age.

● Female offending is almost exclusively restricted to assault (with and withoutinjury) and other thefts. Males are more frequently involved in a wider range ofoffences.

● Both males and females aged between ten and 17 are significantly more likely tocommit a violent offence than a pro p e rty offence, albeit at diff e rent levels.H o w e v e r, if minor assaults without injury are excluded, violent/pro p e rty ratesbecome similar. After the age of 17 the prevalence of violence and pro p e rt yoffending is similar (this applies to both males and females).

● For males violence peaks among 14- to 17-year-olds, at around a third. The peakage for pro p e rty offending is 16 to 17. For females, the level of violent andproperty offending peaks in the teenage years – though within the 12- to 19-year-old age groups there are no significant differences.

● D rug selling appears to peak somewhat later – between 18 and 19 years forboth males and females – though drug selling is rare and the differences are notstatistically significant.

19

Table 3.1 Last year prevalence of offending, by age and sex (percentage committingonce or more)

Percent committing … Property All violent More serious Drug Any Base offence offence violence2 selling offence n

Males 7 7 4 2 13 4,67610 to 11 9 14 9 - 20 31312 to 13 15 18 12 <0.5 25 37514 to 15 17 33 20 2 41 32816 to 17 25 30 23 6 42 31818 to 19 16 18 14 8 29 27620 to 25 10 9 6 5 20 60226 to 35 8 5 3 1 13 59536 to 45 5 3 2 1 9 67246 to 65 3 1 1 - 4 1,197Males 10-17 16 24 16 2 32 1,334Females 4 4 3 1 7 5,05010 to 11 3 5 3 - 8 27112 to 13 9 15 8 <0.5 21 33814 to 15 13 18 12 2 23 29916 to 17 10 15 11 2 21 32718 to 19 9 11 8 5 20 20420 to 25 6 6 4 1 11 72326 to 35 3 2 2 1 6 74236 to 45 2 2 1 <0.5 3 70046 to 65 1 1 <0.5 <0.5 2 1,446Females 10-17 9 13 8 1 18 1,235All 5 5 3 1 10 9,726Notes:1. Source: 2003 Crime and Justice Survey, weighted data. Based on all respondents.2. Excludes assault without injury.

Number of offenders in England and WalesBy applying C&JS estimates of the prevalence of offending to the population in England andWales aged between ten and 65, one can estimate the number of people who hadcommitted at least one of the core offences covered by the survey during 2002/2003.22

Overall, it is estimated that 3.8 million people aged between ten and 65 had committed atleast one offence covered by the survey in the last year. Around 2.1 million had committed

Offending in England and Wales: First results from the 2003 Crime and Justice Survey

20

22. Incidents of offending could have occurred at any time from January 2002 to July 2003 depending on the dateof interview. 2003 population projection estimates for the England and Wales resident population, supplied byGovernment Actuary's Department, were used. There was a total of 19,224,864 males aged between ten and65, and 19,278,566 females.

The extent of offending

a violent offence, including 1.3 million committing assault with injury. An estimated 2.1million had committed a property offence, and 400,000 a drug selling offence. (For ClassA drugs alone, there were 150,000 offenders.)

These estimates are based on the accounts of offending given by respondents in the C&JS.For reasons discussed, one cannot be entirely sure that all those who may have offendedw e re pre p a red to admit to this. The estimated number of offenders, there f o re, could fallshort of the ‘real’ number. Moreover, the estimates derive from a sample of the populationand are thus subject to sampling erro r. Another sample may have resulted in diff e re n testimates. However, one can calculate the precision of the estimates. Table 3.2 indicates therange of estimates within which there is a 95 per cent chance that the true figure falls. Sofor example, one can be 95 per cent confident that the total number of ‘last year’ offendersis between 3.6 and 4.1 million, based on the pro p o rtion who admitted offending in theC&JS.

The overall figure breaks down into around 2.5 million male and 1.3 million femaleoffenders in the last year. In terms of age, there were 1.4 million juvenile offenders (agedbetween ten and 17), 0.9 million aged between 18 and 25 and 1.6 million aged between26 and 65. Thus although people over the age of 25 are less likely to offend, numericallythey are still a significant group of offenders. Table A3.6 shows the figures for males andfemales of different age groups, with confidence intervals.

Table 3.2 Number of offenders in England and Wales (in millions) Number committing… Best estimate Lowest estimate Highest estimate

Any offence in last 12 months 3.8 3.6 4.1Violent offence in last 12 months 2.1 1.9 2.3Property offence in last 12 months 2.1 1.9 2.3Drug selling in last 12 months 0.4 0.3 0.5

Notes:1. S o u rce: 2003 Crime and Justice Surv e y, weighted data. Lowest and highest estimates based on 95%

confidence interval range.

Comparisons with known offendersIt is difficult to compare C&JS estimates with figures of known offenders. First, criminaljustice statistics usually count offending events rather than offenders. They therefore overstatethe number of people convicted or cautioned, since some could have offended more thanonce. Second, and conversely, such statistics will undercount offenders unless all thoseinvolved in an incident are cautioned or convicted, which will not always be the case.

21

Despite these difficulties, it is clear that the C&JS gives a far higher estimate of the numberof offenders than statistics from the criminal justice system. There were around 400,000cautions or convictions in 2002 for the types of offence covered in the C&JS,23 comparedwith the 3.8 million estimate from the C&JS. This is to be expected. The C&JS will include alarge number of people who have only committed relatively minor offences that never cometo the attention of the police, and which might not necessarily have resulted in a form a lresponse if they had.

Number of offences Thus far the focus has been on the pro p o rtion and number of offenders in England and Wa l e sliving in private households. It is also possible to estimate the rate of offending in the sample.

The C&JS estimates a mean annual offending rate of 0.77 offences averaged across thesample. This equates to 770 offences per 1,000 ten- to 65-year-olds in England and Wales.These include the 20 ‘core’ offences against individuals, households and org a n i s a t i o n scovered by the survey, but will not be a full count of crime because not all types of offenceare covered. At the same time, many minor offences will be included and some incidentsthat will have taken place outside England and Wales.24 The estimate is also subject to arelatively wide margin of error. There is a 95 per cent chance that – based on offencesrespondents were prepared to admit to – the ‘true’ number of offences committed per 1,000population lies between 560 and 980.

It is reasonable to ask how C&JS offence estimates compare with British Crime Survey crimeestimates. In fact, though, the comparison is difficult for a number of reasons. First, the BCScovers crime events in England and Wales, while the C&JS covers individual instances ofo ffending some of which may have occurred outside England and Wa l e s .2 5 Second, theo ffence coverage differs in the two surveys, though this can be controlled for to somee x t e n t .2 6 T h i rd, there are diff e rences between the C&JS and BCS in how they re c o rdoffences. For example, the BCS includes an extensive set of follow-up questions to ensurereported incidents are cor rectly classified, and meet legal criteria. This is not the case in theC&JS, which relies simply on carefully worded screener questions which are meant to elicit

Offending in England and Wales: First results from the 2003 Crime and Justice Survey

22

23. If someone is cautioned or convicted twice for example they will appear twice in the 400,000 figure (source:Criminal Statistics, 2002). The C&JS, of course, excludes those of 65 and over but all indications are that thisgroup has low levels of offending and form a very small number of offenders in official statistics.