HEAVEN ON EARTH oi.uchicago.edu

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

edited by

DEENA RAGAVAN

with contributions by

Claus Ambos, John Baines, Gary Beckman, Matthew Canepa, Davíd Carrasco, Elizabeth Frood, Uri Gabbay, Susanne Görke, Ömür Harmanah, Julia A. B. Hegewald, Clemente Marconi,

Michael W. Meister, Tracy Miller, Richard Neer, Deena Ragavan, Betsey A. Robinson, Yorke M. Rowan, and Karl Taube

Papers from the Oriental Institute Seminar

Heaven on Earth

Held at the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago

2–3 March 2012

THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIvERSITY OF CHICAGO ORIeNTAl INsTITUTe seMINARs • NUMBeR 9

CHICAGO, ILLINOIS

IsBN-10: 1-885923-96-1 IssN: 1559-2944

© 2013 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 2013. Printed in the United states of America.

The Oriental Institute, Chicago

Series Editors

Leslie Schramer

Rebecca Cain, Zuhal Kuru, and Tate Paulette

Publication of this volume was made possible through generous funding from the Arthur and Lee Herbst Research and Education Fund

Cover Illustration: Tablet of shamash (detail). Gray schist. sippar, southern Iraq. Babylonian,

early 9th century b.c.e. British Museum BM 91000–04

Printed by McNaughton & Gunn, Saline, Michigan

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Services — Permanence of

Paper for Printed library Materials, ANsI Z39.48-1984.

∞

INTRODUCTION

1. Heaven on earth: Temples, Ritual, and Cosmic symbolism in the Ancient World . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Deena Ragavan, The Oriental Institute

PART I: ARCHITeCTURe AND COsMOlOGY

2. Naturalizing Buddhist Cosmology in the Temple Architecture of China: The Case of the Yicihui Pillar . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Tracy Miller, Vanderbilt University

3. Hints at Temple Topography and Cosmic Geography from Hittite sources . . . . . . . . . 41 Susanne Görke, Mainz University

4. Images of the Cosmos: sacred and Ritual space in Jaina Temple Architecture in India . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55

Julia A. B. Hegewald, University of Bonn

PART II: BUIlT sPACe AND NATURAl FORMs

5. The Classic Maya Temple: Centrality, Cosmology, and sacred Geography in Ancient Mesoamerica . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89

Karl Taube, University of California, Riverside

6. seeds and Mountains: The Cosmogony of Temples in south Asia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 127 Michael W. Meister, University of Pennsylvania

7. Intrinsic and Constructed sacred space in Hittite Anatolia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 153 Gary Beckman, University of Michigan

PART III: MYTH AND MOVeMeNT

8. On the Rocks: Greek Mountains and sacred Conversations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 175 Betsey A. Robinson, Vanderbilt University

9. entering Other Worlds: Gates, Rituals, and Cosmic Journeys in sumerian Sources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 201

Deena Ragavan, The Oriental Institute

PART IV: sACReD sPACe AND RITUAl PRACTICe

10. “We Are Going to the House in Prayer”: Theology, Cultic Topography, and Cosmology in the emesal Prayers of Ancient Mesopotamia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 223

Uri Gabbay, Hebrew University, Jerusalem

11. Temporary Ritual structures and Their Cosmological symbolism in Ancient Mesopotamia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 245

Claus Ambos, Heidelberg University

12. sacred space and Ritual Practice at the end of Prehistory in the Southern Levant . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 259

Yorke M. Rowan, The Oriental Institute

v

oi.uchicago.edu

PART V: ARCHITeCTURe, POWeR, AND THe sTATe

13. egyptian Temple Graffiti and the Gods: Appropriation and Ritualization in Karnak and luxor . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 285

Elizabeth Frood, University of Oxford

14. The Transformation of sacred space, Topography, and Royal Ritual in Persia and the Ancient Iranian World . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 319

Matthew P. Canepa, University of Minnesota, Twin Cities

15. The Cattlepen and the sheepfold: Cities, Temples, and Pastoral Power in Ancient Mesopotamia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 373

Ömür Harmanah, Brown University

PART VI: IMAGes OF RITUAl

16. sources of egyptian Temple Cosmology: Divine Image, King, and Ritual Performer . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 395

John Baines, University of Oxford

17. Mirror and Memory: Images of Ritual Actions in Greek Temple Decoration . . . . . . . . 425 Clemente Marconi, New York University

PART VII: ResPONses

18. Temples of the Depths, Pillars of the Heights, Gates in Between . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 447 Davíd Carrasco, Harvard University

19. Cosmos and Discipline . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 457 Richard Neer, University of Chicago

oi.uchicago.edu

vii

PREfACE

The present volume is the result of the eighth annual University of Chicago Oriental Institute seminar, held in Breasted Hall on Friday, March 2, and saturday, March 3, 2012. Over the course of the two days, seventeen speakers, from both the United states and abroad, examined the interconnec- tions among temples, ritual, and cosmology from a variety of regional specializations and theoretical perspectives. Our eighteenth participant, Julia Hegewald, was absent due to unforeseen circumstances, but fortunately her contribution still appears as part of this volume.

The 2012 seminar aimed to revisit a classic topic, one with a long history among scholars of the ancient world: the cosmic symbolism of sacred architecture. Bringing together archaeologists, art historians, and philologists working not only in the ancient Near east, but also Mesoamerica, Greece, south Asia, and China, we hoped to re-evaluate the significance of this topic across the ancient world. The program comprised six sessions, each of which focused on the different ways the main themes of the seminar could interact. The program was organized thematically, to encourage scholars of differ- ent regional or methodological specializations to communicate and compare their work. The two-day seminar was divided into two halves, each half culminating in a response to the preceding papers. This format, with some slight rearrangement, is followed in the present work.

Our goal was to share ideas and introduce new perspectives in order to equip scholars with new questions or theoretical and methodological tools. The topic generated considerable interest and enthusiasm in the academic community, both at the Oriental Institute and more broadly across the University of Chicago, as well as among members of the general public. The free exchange of ideas and, more importantly, the wide range of perspectives offered left each of us with potential avenues of research and new ideas, as well as a fresh outlook on our old ones.

I’d like to express my gratitude to all those who have contributed so much of their time and energy to ensuring this seminar and volume came together. In particular, I’d like to thank Gil stein, the Director of the Oriental Institute, for this wonderful opportunity, and Chris Woods, for his guidance through the whole process. Thanks also to Theo van den Hout, Andrea seri, Christopher Faraone, Walter Farber, Bruce lincoln, and Janet Johnson, for chairing the individual sessions of the conference. I’d like to thank all the staff of the Oriental Institute, including steve Camp, D’Ann Condes, Kristin Derby, emma Harper, Anna Hill, and Anna Ressman; particular thanks to John sanders, for the technical support, and Meghan Winston, for coordinating the catering. A special mention must go to Mariana Perlinac, without whom the organization and ultimate success of this seminar would have been impossible. I do not think I can be grateful enough to Tom Urban, leslie schramer, and everyone else in the publications office, not only for the beautiful poster and program, but also for all the work they have put into editing and produc- ing this book. Most of all, my thanks go out to all of the participants, whose hard work, insight, and convivial discussion made this meeting and process such a pleasure, both intellectually and personally.

Deena Ragavan

viii Heaven on Earth

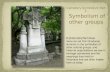

seminar participants, from left to right: Top row: John Baines, Davíd Carrasco, susanne Görke; Middle row: Matthew Canepa, Uri Gabbay, Gary Beckman, elizabeth Frood, Claus Ambos;

Bottom row: Yorke Rowan, Ömür Harmanah, Betsey Robinson, Michael Meister, Tracy Miller, Karl Taube, Clemente Marconi; Front: Deena Ragavan. Not pictured: Julia Hegewald and Richard Neer

oi.uchicago.edu

Heaven on Earth: Temples, Ritual, and Cosmic Symbolism in the Ancient World 1

1

in tHe ancient world Deena Ragavan, The Oriental Institute

Just think of religions like those of Egypt, India, or classical antiquity: an impen- etrable tangle of many cults that vary with localities, temples, generations, dynas- ties, invasions, and so on.

— Émile Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of Religious Life1

Introduction

The image on the cover of this volume is from the sun-god tablet of Nabu-apla-iddina;2 it depicts in relief the presentation of the king before a cultic statue, a sun disc, the symbol of the god Samas. The disc is central to the composition, but to its right, within his shrine, sits the sun god portrayed in archaic fashion. The temple itself is reduced to an abstraction, to its most salient elements: its canopy, a human-headed snake god, perhaps representing the Euphrates River, supported on a date-palm column; below lie the cosmic subterranean waters of the Apsu, punctuated by stars; the major celestial bodies, the sun, moon, and Venus, representations of the gods themselves, mark the space in between. His throne is the gate of sunrise in the eastern mountains, doors held apart by two bison men.

The idea that sacred architecture held cosmic symbolism has a long history in the study of the ancient Near East. From the excavations of the mid-nineteenth century to the scholars of the early twentieth century, we see repeated the notion that the Mesopotamian ziggurat reflected the form of the cosmos. Inevitably, the question of ritual was drawn in. The cult centers of the ancient world were the prime location and focus of ritual activity. Temples and shrines were not constructed in isolation, but existed as part of what may be termed a ritual landscape, where ritualized movement within individual buildings, temple com- plexes, and the city as a whole shaped their function and meaning. Together, ritual practice and temple topography provide evidence for the conception of the temple as a reflection, or embodiment, of the cosmos. Even among the earlier works on sacred architecture, the topic encouraged a comparative perspective. In the light of substantial research across fields

1

1 Durkheim 1912 (abridged and translated 2001), p. 7. 2 The interpretation of the relief that follows is based largely on Christopher Woods’s comprehensive ar-

ticle, “The Sun-God Tablet of Nabu-apla-iddina Re- visited” (2004).

oi.uchicago.edu

2 Deena Ragavan

and regional specializations, this volume is an attempt to revitalize this conversation. This seminar series is, I feel, based on a desire to re-open the often too self-contained field of ancient Near Eastern studies to external and comparative perspectives. In keeping with this motivation, I hope that this book will contribute to galvanizing this avenue of research in both directions, encouraging Near Eastern scholars to look outward, as well as encouraging scholars of all regions of the ancient world to once again consider the “Cradle of Civilization” with respect to their own field.

In this Introduction, I would like to first sketch an outline of this particular idea’s path through the history of my own discipline, Assyriology,3 before assessing the framework on which this volume rests.

History: Out of Babylon

In 1861, after excavations at Birs Nimrud, ancient Borsippa, a site in central Mesopota- mia a little to the south of Babylon, Henry Rawlinson connected the painted colors on the staged tower he had found with the colors assigned to the different planets in the Sabaean system.4 He announced:

we have, in the ruin at the Birs, an existing illustration of the seven-walled and seven-coloured Ecbatana of Herodotus, or what we may term a quadrangular rep- resentation of the old circular Chaldaean planisphere … Nebuchadnezzar, towards the close of his reign, must have rebuilt seven distinct stages, one upon the other, symbolical of the concentric circles of the seven spheres, and each coloured with the peculiar tint which belonged to the ruling planet.5

Although Rawlinson’s interpretation of the ziggurat at Borsippa has been shown to be quite flawed,6 the idea that sacred buildings might represent parts of the cosmos persisted.

Following the decipherment of cuneiform, the study of Mesopotamia became increas- ingly a philological venture, making it possible to offer new interpretations of excavated sites and materials based on the words of the inhabitants. Writing at the end of the nineteenth century, Morris Jastrow understood the Babylonian ziggurat as “an attempt to reproduce the shape of the earth” which, together with a basin representing the underground fresh waters (abzu, apsu), became “living symbols of the current cosmological conceptions.”7 His view rested upon the idea that the Mesopotamian cosmos took the form of a mountain, a possibility raised just a few years earlier by another scholar, Peter Jensen, who had observed the correlation between mountains and temples in Mesopotamia and compared it with the existence of the “world-mountain” (Mount Meru) of Indian mythology.8

3 This path has been mapped before; in particular, the abbreviated story of Eliade and his predecessors presented here owes a great deal to Frank J. Korom’s “Of Navels and Mountains: A Further Inquiry into the History of an Idea” (1992), as well as the writings of Jonathan Z. Smith, as cited throughout. 4 The connection between the colors and the planets had already been posited by Rawlinson twenty years earlier (Rawlinson 1840, pp. 127–28; James and van der Sluijs 2008, pp. 57–58).

5 Rawlinson 1861, p. 18. 6 James and van der Sluijs 2008. 7 Jastrow 1898, p. 653. 8 Jensen 1890, pp. 208–11. On Jensen as the originator of this comparison, see Korom 1992, p. 109. Despite the similar timing and subject matter of their work, Jensen was simply a contemporary, rather than a member of the pan-Babylonian school (Parpola 2004, p. 238).

oi.uchicago.edu

Heaven on Earth: Temples, Ritual, and Cosmic Symbolism in the Ancient World 3

Another deeply flawed theory was this idea of the Mesopotamian world-mountain, or Weltberg, the German term by which it was more popularly known.9 Still, it became wide- spread among a small, but prolific, group of scholars through the early years of the twentieth century. These scholars, the so-called pan-Babylonians, motivated by Friedrich Delitzsch’s lectures on Bibel und Babel and the overt influence of Mesopotamian culture on ancient Israel, extended his conclusions and in so doing sought Mesopotamian influence everywhere. Spear- headed by one Alfred Jeremias, these scholars took it upon themselves to draw comparisons between Mesopotamian mythology, and especially cosmology, and those of many other cul- tures, from Egypt to India. The pan-Babylonian movement soon encountered considerable resistance from within the field of Assyriology, which opted, in the early twentieth century, to turn its gaze largely inward, maintaining its distance from interdisciplinary endeavors in the study of Mesopotamian religion.10

Although the precedence of the comparative approach receded from Assyriology, the challenge was taken up by another discipline. It is from this group that we come to a scholar whose reputation endures at the University of Chicago, and whose influential work continues to overshadow any discussion of the cosmic symbolism of sacred architecture: Mircea Eliade.

In 1937, heavily influenced by the pan-Babylonians, and linking Near Eastern sources with Indian traditions, Eliade began to develop his notion of the axis mundi — a cosmic axis — communicating with different levels of the universe and located at the center of the world.11 It is this axis, and various related symbols, such as trees, pillars, and mountains, that in his view temples represent. Closely related, however, and at the heart of the seminar published here, is his concept of imago mundi: the idea that architectural forms at any scale can be im- ages, replicas, of the greater cosmos — microcosms of the macrocosm. It is with Eliade’s writ- ings, too, that the element of ritual is drawn into the mix, through his correlation between the construction and consecration of sacred places and the creation of the world: rites that construct,…

DEENA RAGAVAN

with contributions by

Claus Ambos, John Baines, Gary Beckman, Matthew Canepa, Davíd Carrasco, Elizabeth Frood, Uri Gabbay, Susanne Görke, Ömür Harmanah, Julia A. B. Hegewald, Clemente Marconi,

Michael W. Meister, Tracy Miller, Richard Neer, Deena Ragavan, Betsey A. Robinson, Yorke M. Rowan, and Karl Taube

Papers from the Oriental Institute Seminar

Heaven on Earth

Held at the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago

2–3 March 2012

THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIvERSITY OF CHICAGO ORIeNTAl INsTITUTe seMINARs • NUMBeR 9

CHICAGO, ILLINOIS

IsBN-10: 1-885923-96-1 IssN: 1559-2944

© 2013 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 2013. Printed in the United states of America.

The Oriental Institute, Chicago

Series Editors

Leslie Schramer

Rebecca Cain, Zuhal Kuru, and Tate Paulette

Publication of this volume was made possible through generous funding from the Arthur and Lee Herbst Research and Education Fund

Cover Illustration: Tablet of shamash (detail). Gray schist. sippar, southern Iraq. Babylonian,

early 9th century b.c.e. British Museum BM 91000–04

Printed by McNaughton & Gunn, Saline, Michigan

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Services — Permanence of

Paper for Printed library Materials, ANsI Z39.48-1984.

∞

INTRODUCTION

1. Heaven on earth: Temples, Ritual, and Cosmic symbolism in the Ancient World . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Deena Ragavan, The Oriental Institute

PART I: ARCHITeCTURe AND COsMOlOGY

2. Naturalizing Buddhist Cosmology in the Temple Architecture of China: The Case of the Yicihui Pillar . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Tracy Miller, Vanderbilt University

3. Hints at Temple Topography and Cosmic Geography from Hittite sources . . . . . . . . . 41 Susanne Görke, Mainz University

4. Images of the Cosmos: sacred and Ritual space in Jaina Temple Architecture in India . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55

Julia A. B. Hegewald, University of Bonn

PART II: BUIlT sPACe AND NATURAl FORMs

5. The Classic Maya Temple: Centrality, Cosmology, and sacred Geography in Ancient Mesoamerica . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89

Karl Taube, University of California, Riverside

6. seeds and Mountains: The Cosmogony of Temples in south Asia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 127 Michael W. Meister, University of Pennsylvania

7. Intrinsic and Constructed sacred space in Hittite Anatolia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 153 Gary Beckman, University of Michigan

PART III: MYTH AND MOVeMeNT

8. On the Rocks: Greek Mountains and sacred Conversations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 175 Betsey A. Robinson, Vanderbilt University

9. entering Other Worlds: Gates, Rituals, and Cosmic Journeys in sumerian Sources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 201

Deena Ragavan, The Oriental Institute

PART IV: sACReD sPACe AND RITUAl PRACTICe

10. “We Are Going to the House in Prayer”: Theology, Cultic Topography, and Cosmology in the emesal Prayers of Ancient Mesopotamia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 223

Uri Gabbay, Hebrew University, Jerusalem

11. Temporary Ritual structures and Their Cosmological symbolism in Ancient Mesopotamia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 245

Claus Ambos, Heidelberg University

12. sacred space and Ritual Practice at the end of Prehistory in the Southern Levant . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 259

Yorke M. Rowan, The Oriental Institute

v

oi.uchicago.edu

PART V: ARCHITeCTURe, POWeR, AND THe sTATe

13. egyptian Temple Graffiti and the Gods: Appropriation and Ritualization in Karnak and luxor . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 285

Elizabeth Frood, University of Oxford

14. The Transformation of sacred space, Topography, and Royal Ritual in Persia and the Ancient Iranian World . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 319

Matthew P. Canepa, University of Minnesota, Twin Cities

15. The Cattlepen and the sheepfold: Cities, Temples, and Pastoral Power in Ancient Mesopotamia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 373

Ömür Harmanah, Brown University

PART VI: IMAGes OF RITUAl

16. sources of egyptian Temple Cosmology: Divine Image, King, and Ritual Performer . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 395

John Baines, University of Oxford

17. Mirror and Memory: Images of Ritual Actions in Greek Temple Decoration . . . . . . . . 425 Clemente Marconi, New York University

PART VII: ResPONses

18. Temples of the Depths, Pillars of the Heights, Gates in Between . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 447 Davíd Carrasco, Harvard University

19. Cosmos and Discipline . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 457 Richard Neer, University of Chicago

oi.uchicago.edu

vii

PREfACE

The present volume is the result of the eighth annual University of Chicago Oriental Institute seminar, held in Breasted Hall on Friday, March 2, and saturday, March 3, 2012. Over the course of the two days, seventeen speakers, from both the United states and abroad, examined the interconnec- tions among temples, ritual, and cosmology from a variety of regional specializations and theoretical perspectives. Our eighteenth participant, Julia Hegewald, was absent due to unforeseen circumstances, but fortunately her contribution still appears as part of this volume.

The 2012 seminar aimed to revisit a classic topic, one with a long history among scholars of the ancient world: the cosmic symbolism of sacred architecture. Bringing together archaeologists, art historians, and philologists working not only in the ancient Near east, but also Mesoamerica, Greece, south Asia, and China, we hoped to re-evaluate the significance of this topic across the ancient world. The program comprised six sessions, each of which focused on the different ways the main themes of the seminar could interact. The program was organized thematically, to encourage scholars of differ- ent regional or methodological specializations to communicate and compare their work. The two-day seminar was divided into two halves, each half culminating in a response to the preceding papers. This format, with some slight rearrangement, is followed in the present work.

Our goal was to share ideas and introduce new perspectives in order to equip scholars with new questions or theoretical and methodological tools. The topic generated considerable interest and enthusiasm in the academic community, both at the Oriental Institute and more broadly across the University of Chicago, as well as among members of the general public. The free exchange of ideas and, more importantly, the wide range of perspectives offered left each of us with potential avenues of research and new ideas, as well as a fresh outlook on our old ones.

I’d like to express my gratitude to all those who have contributed so much of their time and energy to ensuring this seminar and volume came together. In particular, I’d like to thank Gil stein, the Director of the Oriental Institute, for this wonderful opportunity, and Chris Woods, for his guidance through the whole process. Thanks also to Theo van den Hout, Andrea seri, Christopher Faraone, Walter Farber, Bruce lincoln, and Janet Johnson, for chairing the individual sessions of the conference. I’d like to thank all the staff of the Oriental Institute, including steve Camp, D’Ann Condes, Kristin Derby, emma Harper, Anna Hill, and Anna Ressman; particular thanks to John sanders, for the technical support, and Meghan Winston, for coordinating the catering. A special mention must go to Mariana Perlinac, without whom the organization and ultimate success of this seminar would have been impossible. I do not think I can be grateful enough to Tom Urban, leslie schramer, and everyone else in the publications office, not only for the beautiful poster and program, but also for all the work they have put into editing and produc- ing this book. Most of all, my thanks go out to all of the participants, whose hard work, insight, and convivial discussion made this meeting and process such a pleasure, both intellectually and personally.

Deena Ragavan

viii Heaven on Earth

seminar participants, from left to right: Top row: John Baines, Davíd Carrasco, susanne Görke; Middle row: Matthew Canepa, Uri Gabbay, Gary Beckman, elizabeth Frood, Claus Ambos;

Bottom row: Yorke Rowan, Ömür Harmanah, Betsey Robinson, Michael Meister, Tracy Miller, Karl Taube, Clemente Marconi; Front: Deena Ragavan. Not pictured: Julia Hegewald and Richard Neer

oi.uchicago.edu

Heaven on Earth: Temples, Ritual, and Cosmic Symbolism in the Ancient World 1

1

in tHe ancient world Deena Ragavan, The Oriental Institute

Just think of religions like those of Egypt, India, or classical antiquity: an impen- etrable tangle of many cults that vary with localities, temples, generations, dynas- ties, invasions, and so on.

— Émile Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of Religious Life1

Introduction

The image on the cover of this volume is from the sun-god tablet of Nabu-apla-iddina;2 it depicts in relief the presentation of the king before a cultic statue, a sun disc, the symbol of the god Samas. The disc is central to the composition, but to its right, within his shrine, sits the sun god portrayed in archaic fashion. The temple itself is reduced to an abstraction, to its most salient elements: its canopy, a human-headed snake god, perhaps representing the Euphrates River, supported on a date-palm column; below lie the cosmic subterranean waters of the Apsu, punctuated by stars; the major celestial bodies, the sun, moon, and Venus, representations of the gods themselves, mark the space in between. His throne is the gate of sunrise in the eastern mountains, doors held apart by two bison men.

The idea that sacred architecture held cosmic symbolism has a long history in the study of the ancient Near East. From the excavations of the mid-nineteenth century to the scholars of the early twentieth century, we see repeated the notion that the Mesopotamian ziggurat reflected the form of the cosmos. Inevitably, the question of ritual was drawn in. The cult centers of the ancient world were the prime location and focus of ritual activity. Temples and shrines were not constructed in isolation, but existed as part of what may be termed a ritual landscape, where ritualized movement within individual buildings, temple com- plexes, and the city as a whole shaped their function and meaning. Together, ritual practice and temple topography provide evidence for the conception of the temple as a reflection, or embodiment, of the cosmos. Even among the earlier works on sacred architecture, the topic encouraged a comparative perspective. In the light of substantial research across fields

1

1 Durkheim 1912 (abridged and translated 2001), p. 7. 2 The interpretation of the relief that follows is based largely on Christopher Woods’s comprehensive ar-

ticle, “The Sun-God Tablet of Nabu-apla-iddina Re- visited” (2004).

oi.uchicago.edu

2 Deena Ragavan

and regional specializations, this volume is an attempt to revitalize this conversation. This seminar series is, I feel, based on a desire to re-open the often too self-contained field of ancient Near Eastern studies to external and comparative perspectives. In keeping with this motivation, I hope that this book will contribute to galvanizing this avenue of research in both directions, encouraging Near Eastern scholars to look outward, as well as encouraging scholars of all regions of the ancient world to once again consider the “Cradle of Civilization” with respect to their own field.

In this Introduction, I would like to first sketch an outline of this particular idea’s path through the history of my own discipline, Assyriology,3 before assessing the framework on which this volume rests.

History: Out of Babylon

In 1861, after excavations at Birs Nimrud, ancient Borsippa, a site in central Mesopota- mia a little to the south of Babylon, Henry Rawlinson connected the painted colors on the staged tower he had found with the colors assigned to the different planets in the Sabaean system.4 He announced:

we have, in the ruin at the Birs, an existing illustration of the seven-walled and seven-coloured Ecbatana of Herodotus, or what we may term a quadrangular rep- resentation of the old circular Chaldaean planisphere … Nebuchadnezzar, towards the close of his reign, must have rebuilt seven distinct stages, one upon the other, symbolical of the concentric circles of the seven spheres, and each coloured with the peculiar tint which belonged to the ruling planet.5

Although Rawlinson’s interpretation of the ziggurat at Borsippa has been shown to be quite flawed,6 the idea that sacred buildings might represent parts of the cosmos persisted.

Following the decipherment of cuneiform, the study of Mesopotamia became increas- ingly a philological venture, making it possible to offer new interpretations of excavated sites and materials based on the words of the inhabitants. Writing at the end of the nineteenth century, Morris Jastrow understood the Babylonian ziggurat as “an attempt to reproduce the shape of the earth” which, together with a basin representing the underground fresh waters (abzu, apsu), became “living symbols of the current cosmological conceptions.”7 His view rested upon the idea that the Mesopotamian cosmos took the form of a mountain, a possibility raised just a few years earlier by another scholar, Peter Jensen, who had observed the correlation between mountains and temples in Mesopotamia and compared it with the existence of the “world-mountain” (Mount Meru) of Indian mythology.8

3 This path has been mapped before; in particular, the abbreviated story of Eliade and his predecessors presented here owes a great deal to Frank J. Korom’s “Of Navels and Mountains: A Further Inquiry into the History of an Idea” (1992), as well as the writings of Jonathan Z. Smith, as cited throughout. 4 The connection between the colors and the planets had already been posited by Rawlinson twenty years earlier (Rawlinson 1840, pp. 127–28; James and van der Sluijs 2008, pp. 57–58).

5 Rawlinson 1861, p. 18. 6 James and van der Sluijs 2008. 7 Jastrow 1898, p. 653. 8 Jensen 1890, pp. 208–11. On Jensen as the originator of this comparison, see Korom 1992, p. 109. Despite the similar timing and subject matter of their work, Jensen was simply a contemporary, rather than a member of the pan-Babylonian school (Parpola 2004, p. 238).

oi.uchicago.edu

Heaven on Earth: Temples, Ritual, and Cosmic Symbolism in the Ancient World 3

Another deeply flawed theory was this idea of the Mesopotamian world-mountain, or Weltberg, the German term by which it was more popularly known.9 Still, it became wide- spread among a small, but prolific, group of scholars through the early years of the twentieth century. These scholars, the so-called pan-Babylonians, motivated by Friedrich Delitzsch’s lectures on Bibel und Babel and the overt influence of Mesopotamian culture on ancient Israel, extended his conclusions and in so doing sought Mesopotamian influence everywhere. Spear- headed by one Alfred Jeremias, these scholars took it upon themselves to draw comparisons between Mesopotamian mythology, and especially cosmology, and those of many other cul- tures, from Egypt to India. The pan-Babylonian movement soon encountered considerable resistance from within the field of Assyriology, which opted, in the early twentieth century, to turn its gaze largely inward, maintaining its distance from interdisciplinary endeavors in the study of Mesopotamian religion.10

Although the precedence of the comparative approach receded from Assyriology, the challenge was taken up by another discipline. It is from this group that we come to a scholar whose reputation endures at the University of Chicago, and whose influential work continues to overshadow any discussion of the cosmic symbolism of sacred architecture: Mircea Eliade.

In 1937, heavily influenced by the pan-Babylonians, and linking Near Eastern sources with Indian traditions, Eliade began to develop his notion of the axis mundi — a cosmic axis — communicating with different levels of the universe and located at the center of the world.11 It is this axis, and various related symbols, such as trees, pillars, and mountains, that in his view temples represent. Closely related, however, and at the heart of the seminar published here, is his concept of imago mundi: the idea that architectural forms at any scale can be im- ages, replicas, of the greater cosmos — microcosms of the macrocosm. It is with Eliade’s writ- ings, too, that the element of ritual is drawn into the mix, through his correlation between the construction and consecration of sacred places and the creation of the world: rites that construct,…

Related Documents