1 Martha Kuhlman Associate Professor of Comparative Literature Bryant University Smithfield, RI 02917 Abstract As part of the Potsdam Agreement following WWII, 2.8 million Germans were expelled from Czechoslovakia. Disturbing details of mass executions and forced marches of Germans have become the topic of public debate in the Czech Republic. In recent years, representations of this traumatic episode in Czech history have filtered into popular culture as well. This article considers how the graphic novels Alois Nebel and Bomber, whose authors were inspired by Art Spiegelman’s Maus, address the controversial issue of the German expulsion. Note: see end of paper for images Haunting the Borderlands: Graphic Novel Representations of the German Expulsion I first discovered Bomber at a presentation by cartoonists held at the Museum of Comic Art in New York City in November, 2008. In conjunction with a number of prestigious European institutes, the museum had organized a series of events under the title Graphic Novels From Europe. David B., author of Epileptic (France); Max, creator of Bardín the Superrealist (Spain), Isabel Kreitz from Germany, and others were sharing the stage with two writers from the Czech Republic: Jaroslav Rudiš and Jaromír Švedík, aka Jaromír 99. I remember feeling that it was unfortunate these two lesser-known Czech authors were somewhat overshadowed by representatives from France, Spain and Germany, given that their works are as challenging and artistically complex as the other graphic novels discussed on the panel. The problem was (and is) that their graphic novels were unknown because they have only been translated into Polish and German, and the audience was American. So who are these two writers from the Czech Republic, and what makes their work significant? Rudiš, acclaimed Czech novelist, collaborated with artist Jaromír 99

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

1

Martha Kuhlman Associate Professor of Comparative Literature Bryant University Smithfield, RI 02917 Abstract As part of the Potsdam Agreement following WWII, 2.8 million Germans were expelled from Czechoslovakia. Disturbing details of mass executions and forced marches of Germans have become the topic of public debate in the Czech Republic. In recent years, representations of this traumatic episode in Czech history have filtered into popular culture as well. This article considers how the graphic novels Alois Nebel and Bomber, whose authors were inspired by Art Spiegelman’s Maus, address the controversial issue of the German expulsion. Note: see end of paper for images Haunting the Borderlands: Graphic Novel Representations of the German Expulsion I first discovered Bomber at a presentation by cartoonists held at the Museum of

Comic Art in New York City in November, 2008. In conjunction with a number of

prestigious European institutes, the museum had organized a series of events under

the title Graphic Novels From Europe. David B., author of Epileptic (France); Max,

creator of Bardín the Superrealist (Spain), Isabel Kreitz from Germany, and others

were sharing the stage with two writers from the Czech Republic: Jaroslav Rudiš and

Jaromír Švedík, aka Jaromír 99. I remember feeling that it was unfortunate these two

lesser-known Czech authors were somewhat overshadowed by representatives from

France, Spain and Germany, given that their works are as challenging and artistically

complex as the other graphic novels discussed on the panel. The problem was (and is)

that their graphic novels were unknown because they have only been translated into

Polish and German, and the audience was American.

So who are these two writers from the Czech Republic, and what makes their

work significant? Rudiš, acclaimed Czech novelist, collaborated with artist Jaromír 99

2

to create a trilogy of graphic novels Alois Nebel (2006) that follow the often

paradoxical course of Central European history in the aftermath of WWII.1 In

addition to Alois Nebel, the two authors have separately worked on projects that deal

with the history of Czechoslovakia’s border regions: Jaromír 99’s graphic novel

Bomber (2007)2 is set in the former Sudetenland, and Rudiš’s novel GrandHotel,

adapted into a film directed by David Ondriček 2006, takes place in Liberec. Both

Rudiš and Jaromír 99, who grew up in Jeseník, are particularly concerned with the

mixing of German and Czech cultures in these border regions.

What is especially notable about Alois Nebel and Bomber is their inclusion of

the brutal history of the Sudeten German expulsion in 1945 under President Edvard

Beneš, a period of Czech history that has recently been reexamined by historians,

filmmakers, and writers.3 By depicting the Sudeten German characters as victims

rather than as occupiers or Nazi sympathizers, Rudiš (1972) and Jaromír 99 (1963)

represent a controversial episode in Czech history from the perspective of the post-

war generation. Both authors were relatively young when the Velvet Revolution

occured and thus their experience is divided between Czech normalization and the

democratic government that followed. In comparison to the generation that lived

through the war, Czechs born in the 1960s and 1970s are perhaps more willing to ask

difficult questions about the German expulsion.4

1 Three volumes of the trilogy were originally released separately as Bílý potok 2003 [White Creek], Hlavní nádraží 2004 [Main Train Station], and Zlaté hory 2005 [Golden mountains], and then published together as Alois Nebel (Prague: Labyrint, 2006). 2 Jaromír 99, Bomber (Prague: Labyrint, 2007). 3 Misgivings about the morality of the German expulsion appeared in dissident and émigré journals in the 1970s, but the issue came to public attention when Václav Havel apologized for the expulsions as president. See Eagle Glassheim, ‘National mythologies and ethnic cleansing,’ Central European History, 33:4 (2000), 463-486. 4 Special thanks to Eagle Glassheim and José Alaniz for reading drafts of this article and offering valuable comments and suggestions.

3

The Context of Czech Comics

Although the majority of Czech comics prior to the Velvet Revolution were

intended primarily for children, they were nonetheless subjected to the constraints of

censorship, first under the Nazi occupation, and again under the communist

government.5 Some examples of popular comics pre-1989 include the adventure

stories in Rychle šipy [Fast Arrows] by Jaroslav Foglar and illustrator Jan Fischer, and

comics by Miloš Macourek and Kaja Saudek, which were influenced by the U.S.

comic books like Captain America that Saudek received from relatives in the states.

In both cases, however, the creators were hindered by communist authorities who

condemned these works as examples of Western decadence; the children’s comics

magazine Ctyřilistek [Four-leaf Clover] by writer Ljuba Štíplová and cartoonist

Jaroslav Nemeček was one of the few condoned publications.6

After the fall of communism, Czech translations of American and European

works primarily intended for adult audiences began to change the perception of the

medium—the first and most influential of these were Art Spiegelman’s Maus I and II,

released by the prestigious literary publisher Torst in 1997 and 1998 respectively.

Since then, the number of foreign titles available in Czech has exploded; a Czech

reader can obtain a variety of American mainstream serial comics (Batman,

Daredevil, Green Lantern) as well as a fair number of alternative titles (Chris Ware’s

Jimmy Corrigan: Smartest Kid on Earth 2004; Black Hole, Charles Burns, 2008;

Palestine, Joe Sacco, 2007; Berlin, Jason Lutes, 2012). In a similar vein, French-

language comics such as Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis (2006-2007), Frederik Peeter’s

5 See Tomáš Prokůpek’s overview in ‘Czech Comics,’ International Journal of Comic Art 2 (2003), 312-338. 6 Ibid., 325.

4

Pilules bleues [Blue Pills] (2008), and comics by Lewis Trondheim and Joann Sfar

are available in Czech.7

Collectively, this influx of international material demonstrated to Czech

audiences that comics have the potential to treat serious subjects and have literary

promise. Unencumbered by censorship and inspired by these foreign examples, Czech

artists and writers — many of them graduates of prestigious art schools — are

exploring the possibilities of the medium through independent publications such as

Aargh and Crew and an annual comics festival that features an international array of

comics artists.8 This new generation of cartoonists reached a critical mass in 2007

with the exhibit Generace Nula [Generation Zero], a title that has come to represent

the best and most talented artists in contemporary Czech comics. In the introduction

to the exhibit catalogue, Tomáš Prokůpek writes that Czech comics ‘právě prožívá své

vůbec nejlepší období’ [are experiencing their best period ever]. Moreover, he claims

that comics have gained enough respect that ‘současní tvůrci tak nemusejí zbytečně

mrhat energií na obhajobu svého oblíbleného media a mohou se věnovat tomu

hlavímu—tedy vymýšlení a kreslení komiksů’ [contemporary artists don’t have to

waste energy defending their favorite medium and can devote themselves to the main

thing—drawing and creating comics].9 The anthology features an Alois Nebel story

by Rudiš and Jaromír 99 alongside a diverse range of fictional and nonfictional work

including an excerpt from Branko Jelinek’s Oskar Ed trilogy (2003-2006), a

7 See Tomáš Prokůpek, ‘Ven z bubliny!’ A2. 20 (2008) for the impact of foreign language comics on the Czech comics scene. To see what is available in Czech, refer to the internet bookstore website www.kosmas.cz. The primary publisher for English language mainstream and alternative comics is BB Art; for French language comics, Mot is the dominant publishing house. 8 José Alaniz describes the Czech comics scene since 2000 in ‘Introduction: A Czech Patchwork,’ International Journal of Comic Art 11 (2009), 7-20. 9 Tomáš Prokůpek, ‘Komiks tady a teď.’ Generace Nula: Český komiks 2000-2010 (Prague: nakladatelstvi Plus, 2010), 4.

5

disturbing narrative about childhood trauma; a surreal story by Vojtěch Mašek, Džian

Baban (writer) and Jan Šiller (artist), the collaborators behind Monstrkabaret Freda

Brunolda (2004-2006); comics reportage from Korea by Tomáš Kučerovsky; and

documentary comics criticizing the Czech governments’ treatment of Gypsy children

by Toy_Box, to mention only a few examples.

Of these many talented artists and writers, Rudiš and Jaromír 99 are doubtless

the most media savvy, due in no small part to their friend and editor Joachim Dvořák,

the man behind Labyrint [Labyrinth] publishing house. In order to promote Alois

Nebel and Bomber, the three friends created the rock band ‘Bomber,’ released a CD,

posted professionally produced music videos, and took the whole show on the road

for the book tour.10 In some cases, readings and performances were enhanced by a

traveling exhibit of posters featuring art from the graphic novel and documentary

photos. Ultimately Alois Nebel proved to be so popular that it was also adapted into a

theater production and an animated feature-length film version of the graphic novel

was released in 2010.11 A spin-off project called Na trati [Tracks] was published

serially in the magazine Reflex from 2005-2007, republished in book form,12 and was

recently converted into an app for google play. For those who want up to the minute

information on Alois Nebel developments, Rudiš keeps fans informed through Alois

Nebel sites on facebook and myspace. In short, Alois Nebel is nothing short of a

phenomenon. You can even buy the t-shirt.

10 See Jan Velinger’s interview with Joachim Dvořák, ‘Founder of Labyrinth publishers unafraid to take risks. ’Český Rozhlas. 2 May 2006. www.radio.cz 11 Theater adaptation by Činoherní studio Ústí nad Labem, 2005. The rotoscope film Alois Nebel was directed by Tomáš Luňák and released by Negativ film in 2011. In 2012, the film was the Czech Republic’s official entry to the Oscars for best foreign language film. 12 Jaroslav Rudiš and Jaromír 99, Na Trati (Prague: Labyrinth, 2008).

6

Comics and History

Given that Rudiš is primarily known in the Czech Republic for his novels, one

may well ask why he would collaborate with Jaromír 99 and choose comics as a

storytelling medium. In addition to their popular appeal, the formal properties of

comics open up possibilities unavailable in prose or traditional historical narratives.

As Hillary Chute has noted, the conflation of time and space in comics ‘lends graphic

narratives a representational mode capable of taking up complex political and

historical issues with an explicit, formal degree of self-awareness, which explains

why historical graphic narratives are the strongest emerging genre in the field.’13

More than any other graphic narrative, Art Spiegelman’s Maus14 has changed the way

we think about representing history in comics by foregrounding the act of

storytelling.15 In superimposing his father Vladek’s experiences in Auschwitz over the

ordinary contemporary reality of Rego Park Queens, Spiegelman brings together

jarring combinations of past and present that emphasize discontinuities between these

two narrative frames through the inventive use of panels, fractured page layouts, and

disagreements between father and son.16

13 Hillary Chute, Graphic Women (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010), 4. 14 Art Spiegelman, Maus (New York: Pantheon Books, 1997). I’m referring to the single book that includes volumes I and II. 15 In MetaMaus, Spiegelman explains the importance of this deliberate choice: ‘Visibly juxtaposing pasts and presents allowed there to be a continual kind of flashing back and forth that wouldn’t feel like a total flashback to an ersatz reconstruction of the past. Telling a story as if I was the invisible hand that allowed Vladek to make a comic about Auschwitz would have been so fraudulent.’ MetaMaus (New York: Pantheon Books, 2011), 208. 16 There are so many articles on Maus that it’s impractical and undesirable to list them all, but I will mention two that I think are particularly useful in their discussion of the relationship between history and the text: Joshua Brown, book review, Journal of American History 79:4 (1993) 1668-1670; James E. Young, ‘The Holocaust as Vicarious Past: Art Spiegelman’s Maus and the Afterimages of History’ Critical Inquiry 24 (1998) 666-699.

7

Jaromír 99 explains how Maus was a crucial reference as he developed Alois

Nebel and Bomber, ‘je to vlastně muj první komiks který jsem četl v dospělosti a u něj

jsem si uvědomil jak je to skvělé medium a kvuli němu jsem ve svých 35 letech opět

začal kreslit a možná díky tomu vznikl Alois Nebel a Bomber’ [it was really the first

comic that I read as an adult and I realized how amazing the medium of comics is.

Thanks to (this encounter with Maus), I started to draw again when I was 35 years

old; the idea of Alois Nebel and Bomber was probably inspired by this].17 Both Alois

Nebel and Bomber, although fictional, refer to historical traumas and create unsettling

juxtapositions of past and present. In both graphic novels, past crimes haunt the same

location in the present on skillfully composed pages, however the representational

strategies employed by Jaromír 99 differ from Spiegelman’s in significant ways, as

we shall see. First, I want to examine scenes from Alois Nebel and Bomber, both of

which are set post-89 in the Czech Republic, and then consider these works in the

context of debates about the history of the German expulsion.

Alois Nebel

Alois Nebel, the eponymous protagonist of the trilogy, was born in 1948, the

year that marks the beginning of communist rule in Czechoslovakia, and thus

occupies a unique standpoint from which to view both the past and the historical

upheavals to come. He is a train dispatcher in the border town of ‘Bílý Potok’ [White

Creek], a position that seems to function as an extended metaphor for his place in

history as a witness to occupying powers and the migration of people across borders.

Like the character Miloš Hrma from Bohumil Hrabal’s Ostře sledované vlaky

[Closely Watched Trains], Nebel is a down-to-earth, unassuming everyman with good

intentions. Throughout the narrative, he tries to help others; in one instance, he

17 Email exchange with Jaromír 99, 8 Aug 2012.

8

conceals a deserting Soviet soldier; in the main plotline, he befriends Němy, a Polish

murderer who is confined in an insane asylum. Nebel himself suffers from a kind of

insanity when a mist distorts his vision and he sees into the past,18 witnessing

traumatic historical moments.

To convey the somber tone of the graphic novel, Jaromír 99 adopts a stark

black and white palette influenced by German Expressionism, one of his sources of

inspiration.19 Sometimes sharp and jagged, sometimes more subtle and smooth, the

edges and contours of his drawings resemble woodblock prints even though they are

rendered with a pen. This black and white style of drawing combined with a social

conscience recalls Belgian expressionist Frans Masereel’s Mon livre d’Heures (1919)

[Passionate Journey] or contemporary artist Eric Drooker, whose work Flood, a novel

in pictures (1992) depicts alienation in New York City. As is the case in America and

in European comics culture more generally, black and white comics in the Czech

context tend to be aimed at an adult readership and have a darker, psychological

dimension as exemplified by Monstrkabaret Freda Brunolda (writer Džian Baban and

artist Vojtěch Mašek) and Oskar Ed by Branko Jelinek.20 Thus, from the beginning,

the visual style of Alois Nebel conveys a sense of gravity and seriousness well-suited

to examining historical conflicts.

18 Rudiš emphasizes that he chose the name ‘Nebel’ because it means ‘fog’ in German; reversed, it becomes ‘Leben’ [life], inviting readers to consider Nebel’s place in the broader sweep of Czech history. 19 See interview with Jaromír 99, ‘Jaromír 99: mezi rockem, filmem, a Mignolou.’ 14 Nov. 2003. www.Komiks.cz . Spiegelman also discusses how woodcuts (specifically by Lynd Ward) and German Expressionism were important influences for him, particularly as he was working on the ‘Prisoner on Hell Planet’ portion of Maus. See ‘Reading Pictures,’ his introduction to the first volume of the Library of America books on Lynd Ward: God’s Man, Madman’s Drum, Wild Pilgrimage (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), xxiv. 20 Tomáš Prokůpek, ‘Ven z bubliny!’ A2 (2008). http://www.advojka.cz

9

Although the depiction of the German expulsion is not the main subject of the

story, it does appear in a few peripheral scenes and it clearly troubles Nebel’s

conscience. As he is recounting the history of his family in the first book, we learn

that his grandfather worked at the station with a German named Müller. Nebel states

that Müller was a good man who had helped Czechs during the war, but that his fear

of Czech revenge after the war compelled him to leave. In the second volume, Hlavní

nádraží [Main Train Station], Nebel travels to Prague to see the Wilson Train Station,

an impressive art nouveau edifice where he ultimately spends a year people-watching.

During one of his hallucinatory visions, he stands on the balcony and sees crowds

flowing through beginning in the present but stretching back into the past to the

founding of the first Republic in 1918. As the clock rewinds, two panels show

Germans leaving the country in 1945 with swastikas painted on their backs; an angry

Czech soldier taunts one of them: ‘Chceš do rajchu? Můžeš. A zadarmo. Marš domů!’

[Do you want to go back to the Reich? You can, for free. Go home!]. On the

following pages, we see concentration camp survivors returning home, and then leap

further back in time as crowds of Jews marked with stars are sent off to the camps. 21

These are simply passing references to the German expulsion; the third

example occurs somewhat later in the book and is more dramatic. Here, Nebel’s

friend and coworker Wachek is depicted about to execute a Sudeten German at point-

black range. The size of the panel, which occupies the top half of the page, and the

closeup of the gentle face of an elderly man against the black background, renders this

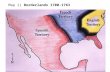

scene particularly disturbing <Fig 1>. Jaromír 99’s style is crisp and precise; the

wrinkles at the corners of the man’s eyes create a pleading expression that calls for

21 For a more thorough discussion of this sequence of pages and of Alois Nebel in general, see my article, ‘Time Machine: Main Train Station by Jaroslav Rudiš and Jaromír 99,’ International Journal of Comic Art, 11:1 (Spring 2009), 63-73.

10

our sympathy. The man, who apparently knows Wachek, begs for his life in German:

‘Herr Wachek, bitte nicht.’ In the lower panel, another officer in uniform declares in

Czech ‘Mrtvej Němec, dobrej Němec’ [A dead German is a good German] as a

number of Germans are forced to kneel. The narrative voice of Nebel, however, is not

terribly judgmental: ‘A jak sem lidi přišli, tak je zase jiní vyhnali. Děly se tu hrozné

věci a starý Wachek prý byl při tom, co tím myslím. Jak řikám, možná jsou tu jen

pomluvy. Lidi už jsou takovi.’[And just as they had come, so were they again driven

away. Horrible things were done (note the passive voice) and Mr. Wachek was right

in the middle of it, as far as I know. But maybe it’s just slander; people are like that.]

In the exhibit that accompanies the book, one poster reproduces this particular

scene with additional documentary photos and commentary that is ostensibly from the

perspective of Nebel, but is obviously a reflection of the authors’ views <Fig 2>. The

poster relates how many Germans in the border regions were enthusiastic Hitler

supporters, and shows sketches of Nazi prison camps. At the same time, however, the

poster emphasizes that some Germans were victims, as in the section concerning

Jeseník, the town where the authors grew up:

Before the war, our region was more German than Czech, and after 1938

Jeseník, known as Friewaldau at that time, became part of Hitler’s Reich. I

don’t think they all wanted that. Death marches from German concentration

camps crossed our region. So after the war, the Czechs drove the Germans out.

Our region has been a little empty and sad since that time.22

These sentences are the captions for two photographs: the first shows dead German

bodies in the countryside; the other depicts a car overladen with people and baggage

as they leave. Considering these few scenes from Alois Nebel in combination with the 22 Poster from the Alois Nebel exhibit, Nov 22-Dec 19, 2008; Prague Kolektiv, Brooklyn, NY. The translation from Czech was part of the original poster.

11

exhibit, one would be inclined to interpret the work as an act of historical recovery,

bringing to light a tragic aspect of World War II and its aftermath that was untold or

unacknowledged by the Czech public. But this story is only one of many strands that

propel the trilogy—the mystery behind the Polish murderer or the love story between

Nebel and Květa, the bathroom attendant in the train station, are the dominant

plotlines. Representing the German expulsion is not the primary purpose or theme of

the book, even if it is undeniably present.

Bomber

On the other hand, Bomber, the solo project of artist and musician Jaromír 99,

places the fate of the Sudeten Germans much more centrally, although this agenda is

hidden in plain sight. From the beginning, this book is more secretive and elliptical

compared to Alois Nebel. On the flyleaf appears the following synopsis:

Kdesi v pohraničí, kde krajina přišla o svou duši, leží jezero, které vždy

přitahovalo nešťasné. Sem, do míst svého dětsví, se na konci kariéry vrací

profesionální fotbalista. V domě sých prarodičů a ve vlastní minulosti hledá co

kdysi ztratil. Lidé přicházejí a zase odcházejí. Jen jezero mlčenlivě zůstává.

Možná pravě v něm je ukrté největší tajemství jeho vzpomínek…

[Somewhere in the borderlands, where the landscape lost its soul, there is a

lake that always attracted the unhappy. Here, at the end of his career, a

professional soccer player returns to the place of his childhood. In his

grandparents’ house, he looks for what he once lost. People come and people

leave again. Only the lake silently remains. In the lake is hidden perhaps the

greatest secret of his memory…]

12

The prelude to the book opens with the image of a house on a hill with a lake beneath,

a landscape that serves as a mute witness to the lives of the inhabitants that pass

through from 1945 to 1998.

In the first pages, a Czechoslovak German girl and her father solemnly fill the

girl’s pockets with stones and row to the middle of the lake. After blessing her father,

she commits suicide by drowning. No explanation of her desperate act is given, but

she does enigmatically tell her father that she does not want to end up ‘like Helga.’23

A few pages later, an entire page dramatically cast in black represents bewildered

Russian soldiers discovering her parents who have also committed suicide by hanging

themselves <Fig 3>.24 In the upper left corner of the page, a short passage relates the

following information: ‘According to statistics for the Czech, Moravian and Silesia

regions, 5,556 Czech citizens of German descent committed suicide in 1945.’25

Unattributed, floating quotes such as this appear occasionally in both Bomber and

Alois Nebel, and appear to serve as objective narration in order to lend historical

authenticity to these fictional works. Thus the introductory portion of the graphic

novel ends, although the spectral character of the girl haunts the main narrative that

follows.

23 According to Eagle Glassheim, this likely refers to the fear of rape by Soviet or Czechoslovak paramilitary forces. 24 This image bears an uncanny resemblance to a page from Maus I in which Vladek describes friends of his who were put to death by hanging for ‘dealing goods without coupons’ (85). The page is centered upon hanging bodies of these Jewish businessmen, with panels intruding above and below to indicate Vladek’s narration. In Bomber, the representation of Germans as perpetrators is reversed to Germans as victims. 25 I was not able to verify the precise figure cited in Bomber, but other sources support the claim. According to the Czech-German Joint Commission of Historians: ‘a German “general investigation” … Substantiated approximately 5,000 suicides’ (Konfliktní společenství, katastrofa, uvolnění: Náčrt výkladu německo-českých dějin od 19. století [Conflictual Community, Catastrophe, Detente: An Outline of an Interpretation of Czech-German History from the Nineteenth Century] (Prague: Ústav mezinárodních vztahů, 1996), 29.

13

The protagonist of Bomber is Franz Kovac, an expatriot Czech who has

become a famous German soccer player and returns to the Czech Republic to visit the

house where his grandparents once lived. In the same way that the main train station

functions as a kind of time machine in Alois Nebel, this house is a site where multiple

histories collide: the suicide of the Sudeten family, Kovac’s childhood memories of

visiting his grandparents’ home, and the present-day hotel that Kovacs visits as an

adult. These connections are not explicitly stated in the text, but rather are suggested

through repeated images of the girl and the building.26 Distinct moments separated by

decades are brought together in the space of the page when the image of the Sudeten

girl appears with the young Kovacs against the black outline of the house in a vertical

triptych of panels. Although he does not know who she is, Kovacs is haunted by the

Sudeten girl in his dreams. <Fig 4>

The melancholy tone of the narrative is subtly reinforced by the novel’s

soundtrack: Jaromír 99 uses the lyrics to songs by the band ‘Bomber’ as captions in

several sequences. At first, these two semantic tracks—one textual and the other

visual—seem parallel but not directly related;27 the lyrics provide a melancholic

background to the action rather than serving as an explanation of what is happening

on the page. And indeed, the album stands alone as a collection of love songs and

songs about the border region where Jaromír 99 and Rudiš grew up.28

26 In fact, Jaromír 99 writes that he originally envisioned the book as primarily about the stories inhabiting the building and not as much about the soccer star: měl být víc o tom domě, který v komiksu hraje velko roli, než o fotbale, takže možná ještě někdy nakreslím druhy díl, abych se do toho baráku mohl vrátit [it should be more about this building, which plays a large role in the comic, rather than about soccer. Maybe one day I’ll draw a second volume in order to return to the building]. From email correspondence with Jaromír 99. 27 See Scott McCloud, Understanding Comics (New York: Harper Perennial, 1994) 154. 28 Czech reviewers favored the album over the graphic novel, which they tended to criticize as slow-paced. See ‘Bomber aneb slabší rána,’ 29 Jan 2008 www.komiks.cz

14

Upon further examination, however, links between the lyrics and the story

emerge. The captions to the above-mentioned sequence with young Kovacs, the girl,

and the silhouette of the building are lyrics from the song ‘Bezejmenná’ [Nameless]:

Přiletěl nad dům černý mrak a ptáci přestali zpívat/Lidé si šeptali, to nebude

jen tak/Bydlí tam ta beze jména/Ráno ten mrak byl pryč/a ptáci zpívali, jakoby

nic/Lidé si vzali vidle a sekery/šli se k ní podívat/Hledali na půdě, ve sklepě i

po cimrách/nenašli, jako by nikdy nebyla.

[Above the building flew a black cloud/and birds stopped singing/People

whispered, there must be a reason/one without a name lives there/In the

morning the cloud was gone/And birds sang as if nothing happened/People

took pitchforks and hatchets/They went to go see her/They looked in the attic,

in the cellar, in all the rooms/They found nothing as if she had never existed]

A mournful, wailing chorus reinforces the song’s sinister, melancholy tone. The real

reason for the girl’s fear in the first pages is suggested in the description of mobs of

angry Czechs seeking retribution after the war in the period of the divoký odsun [wild

expulsions] in the spring and summer of 1945. Of course, they do not find her because

she and her entire family committed suicide first. This unspoken, quiet tragedy has

repercussions and reverberations in the present of the narrative as Kovacs struggles

with his own private traumas.

Kovac is mostly silent throughout the graphic novel; the rhythm of the

narrative follows the logic of traumatic repetition punctuated by repeated of images of

his wristwatch, memories, and nightmares from his childhood. His worst memory is

of the moment he innocently kicked a ball to his grandfather when he was a boy,

(no author given) and Tomáš Hibi Matějiček, ‘Bomber melancholický gól v komiksové síti Jaromíra 99’ 20 Dec 2007. www.acktuálně.cz

15

accidentally provoking a heart attack that causes his grandfather’s death.29 He also has

flashbacks to another time when as a professional soccer player, he kicked a ball that

hit a goalie in the head, seriously injuring him and thus reminding him of his other

fatal kick.30 While he is staying in his grandparents’ former house, which has since

been converted into a hotel, his traumatic memories become confused with the fairy

tale of the jezero ztracených [lake of the lost], a story he reads before drifting off to

sleep. Kovac dreams that he is descending into a cellar or drowning in the water, both

clear metaphors for the unconscious, and it is in this subterranean landscape filled

with storybook castles and strange fish that Švedík brings together Kovac and the girl.

Near the end of the graphic novel, Kovac has a drug-induced hallucination in

which he imagines that he is again in this underwater, fairy-tale world when the girl

tosses his soccer ball to him, saying, ‘To ti posílá děda. Chytej!’ [Your grandfather

sent you this—catch!].31 In this unexpected, surreal encounter, Kovac’s personal guilt

for his grandfather’s death is associated with the collective guilt surrounding the death

of the Sudeten girl, although this inference is only available to the reader since the

characters do not make this connection. Kovac never realizes on a conscious level that

his sense of melancholy and loss is rooted in the sad history of the house. As Czech

reviewer Jaroslav Balvín notes, this tension between past and present is somewhat

artificially resolved when Kovac sleeps with a woman who resembles the ghostly girl

in his dreams. Balvín criticizes this ending as too easy, and adds the following more

damning judgment: ‘Národy si však své kolektivní viny musejí odpykávat

29 Bomber, 54. 30 Ibid., 80. 31 Ibid., 118-119.

16

dlouhodoběji’ [Nations, however, must serve time for their collective sins for a long

while yet].32

The ending is not quite as simple or happy as this review suggests, however.

Kovac follows his new girlfriend to a squatter camp where he is arrested by Czech

authorities the next day for trespassing. At this point, the narrative takes an

unexpected turn when we suddenly view the scene from the perspective of his parents

in Germany who are watching the news report of his arrest on TV. In a somewhat

dizzying mise-en-abyme, a panel frame echoes the television screen on which we see

Kovac being taken away by Czech police. After panning through the interior of the

parents’ house, the story ends with the mother sitting on the bed in her son’s

childhood room. The penultimate page of the graphic novel abandons panels

altogether and depicts the mother’s hands holding a family photo of the three of them

— mother, father and son — taken when Kovac was still a boy in his soccer uniform.

Far from revealing the secrets of the text, the ending seems deliberately unsettling

rather than reassuring.

Reading Bomber and its reviews, it is striking how much is left unstated about

the German expulsion given that it is the foundation upon which the entire story rests

based on the suicides of the former inhabitants of the house and the reoccurring motif

of the girl. Apart from Balvín, who is rather oblique in referring to kolektivní viny

[collective sins], no critic addresses this aspect of the story. Jaromír 99 states that part

of his motivation for creating the graphic novel was ‘proto že se odsunu nikde moc

nemluvilo a když tak šeptem’ [because people didn’t talk much about the expulsions

and when they did, in whispers].33 Regardless of how it was understood, the graphic

32 Jaroslav Balvín, ‘Jaromír 99, spoluautor Aloise Nebela, vydává komiks Bomber,’ www.novinky.cz 2 Jan 2008. 33 Email with Jaromír 99, 8 Aug 2012.

17

novel gained some acclaim within the comics community when it won the Muriel

prize for best Czech graphic novel at Komiksfest in 2008.34 Both Alois Nebel and

Bomber were publishing successes, although Nebel was far more popular, at 25,000+

copies sold as opposed to Bomber’s limited print run of 1,500.35

A second point worth considering is how Jaromír 99 and Rudiš position

themselves as narrators of this unspoken trauma. Unlike Spiegelman or Joe Sacco,

they do not call attention to their role as storytellers. The German expulsion is not

their personal story and thus it is very different from the situation of Spiegelman, who

tries to convey the experiences of his father in Auschwitz, or Sacco in his role as a

journalist in the former Yugoslavia or in Palestine.36 Just as Maus poses the question

of ‘how to negotiate the subject position of one born later,’37 the authors, children of

the generation that lived through the war, had to find the right amount of distance to

reveal a past injustice without claiming it as their own. Marianne Hirsch frames the

dilemma this way: ‘What do we owe the victims? How can we best carry their stories

forward without appropriating them, without calling undue attention to ourselves, and

without, in turn, having our own stories displaced by them?’38 Jaromír 99’s solution is

to adopt a neutral tone by including factual text in white on a black background. It is

almost as if to say: let the facts speak for themselves.

The German Expulsion, divoký odsun, and vyhnání

Beginning in the mid-1990s, a reexamination of Czech history between 1945

and 1948 was prompted by the discovery of mass graves of Sudeten Germans and 34 See the Komiksfest website: http://www.komiksfest.cz/2008 35 Email with Joachim Dvořak, 22 Aug 2012. 36 See Joe Sacco, The Fixer: A Story from Sarajevo (Montréal: Drawn & Quarterly, 2003); Safe Area Goražde (Seattle: Fantagraphics, 2000), and Palestine (Seattle: Fantagraphics, 2001). 37 Dominick LaCapra, History and Memory After Auschwitz (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1998) 177. 38 Marianne Hirsch, ‘The Generation of Post-Memory,’ Poetics Today 29 (2008): 104.

18

controversies surrounding the Beneš decrees, which confiscated the property of Czech

Germans and expelled 2.8 million of them following WWII.39 Václav Havel, the first

President of Czechoslovakia following the Velvet Revolution, ‘particularly

questioned the principle of collective guilt’ behind the German expulsion, and

publicly apologized for these atrocities in 1990 as a way of making peace with the

past.40 Unfortunately, public opinion at the time considered this gesture as ‘his biggest

political blunder.’41 The debate was reignited in 2002 when the Czech Republic was

under pressure to renounce the Beneš decrees as a condition for admission to the

European Union,42 but ultimately the government was able to dodge this objection by

claiming that the decrees had no legal standing and thus did not require any repeal.43

In fact, this issue has only become more politically sensitive given that recent

revelations have brought to light more details of the severity and violence of the

German expulsion.44

The opening scene of Bomber is set in 1945, right at the time of the ‘wild

expulsions.’ Historian Mary Heimann explains how just after the war, ‘The

opportunity to turn the tables on “the Germans,” regardless of whether or not

German-speaking individuals had actually been Nazi, Nazi sympathizers or even

German nationalists, proved impossible for many Czechs to resist.’45 She draws a

distinction between the ‘wild expulsions,’ which ‘resulted in the forced expulsion of

about 660,000 German speakers from Czechoslovakia, [and] the killing of anywhere 39 Luboš Palata, ‘Normal Neighbors,’ Transitions Online, 1 Feb 2011. 40 Ladislav Holy, The Little Czech and the Great Czech Nation: National identity and the post-communist social transformation (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1996) 123 41 Ibid., 124. 42 Emil Nagengast, ‘The Beneš Decrees and EU Enlargment,‘ The Journal of European Integration 25 (Dec 2003): 335-350. 43 Conversation with Jiři Pehe, political commentator, 15 July 2011, Prague. 44 Luboš Palata, ‘An old crime, uncovered,’ Transitions Online, 26 Aug 2010. 45 Mary Heimann, Czechoslovakia: A Failed State (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009) 156.

19

between 19,000 and 30,000 more’46 in the months immediately following the war and

the larger scale expulsion of Germans (also referred to as vyhnání) under the Potsdam

agreement, which accounts for another 2.8 million. The claims regarding mass

executions during the wild expulsions were reinforced by David Vondriček’s 2010

documentary Killing the Czech Way,47 which shows footage of Czech-Germans lined

up and shot at close range, much as was depicted in the scene from Alois Nebel. In

popular culture, the most sensational representation of the divoký odsun is director

Juraj Herz’s film Habermannův mlýn, also released in 2010. The film, which takes

place from 1938 to 1945 and is based on real events, dramatizes the plight of Sudeten

Germans from the perspective of a German mill owner who was fair to his Czech

employees, but fell victim to his hostile Czech neighbors after the war.48

What is noteworthy about Bomber and Alois Nebel in the context of Czech

national identity is that they raise troubling questions about the behavior of ordinary

Czechs just following the war,49 when Czechoslovakia was a free and democratic state

under President Beneš. The depiction of the wild expulsions is hard to reconcile with

the two dominant historiographies of the Czech nation: according to the first, Czechs

represent a progressive beacon of democracy and humanism, best epitomized by the

values of the First Republic under President Masayrk. The second, non-nationalistic

view posits the Czech nation as the hapless victim of 20th century European history:

first, as dominated by the Habsburg Empire, then betrayed by 1938 Munich

46 Ibid., 159. 47 Palata, ‘An old crime, uncovered.’ 48 Habermannův mlýn, Dir. Juraj Herz. KN Filmcompany, 2010. 49 As Eagle Glassheim has argued, ‘Ground-level perpetrators are the crucial missing link in our understanding of ethnic cleansing. Though national and international influences contributed to the anti-German mood after the war, local conditions and popular mentalities were essential ingredients of the Czechoslovak expulsion fury in the summer of 1945,’ in ‘National Mythologies and Ethnic Cleansing: The Expulsion of Czechoslovak Germans in 1945,’ 465.

20

Agreement, oppressed by the Nazis during WWII, and finally oppressed yet again by

a Soviet-dominated form of Communism.50 The period between 1945 and 1948 used

to be passed over with relatively little scrutiny, but a younger generation of Czechs —

among them Jaromír 99 and Rudiš — are more willing to confront troubling aspects

of the history of Czech-German relations.

50 Heimann 175-176; Holy 126-127.

21

Images and figures for ‘Haunting the Borderlands: Graphic Novel Representations of the German Expulsion’

22

Figure 1: Wachek is about to execute a German at point-blank range. Another officer remarks, ‘Dead German, good German.’

Figure 2: The image of the execution is recontextualized in the exhibit poster in an explanation of the German expulsions.

23

Figure 2: The image of the parents’ suicide is accompanied by statistics on suicides for Czech Germans in 1945.

Related Documents