22 BOOKS March 24-25, 2018 theaustralian.com.au/review AUSE01Z10AR - V1 Peter Craven Lysicrates and Martin — Two Arts Patrons of History Return to Give Again: Theatre for All By The Lysicrates Foundation MUP, 163pp, $35 (HB) It’s funny what can bring a city together. Who would have thought Sydney would go mad about the Greeks? It’s happened, though, thanks to an unusual theatre prize established by Patricia and John Azarias, a couple of mon- eyed, myriad-minded culture vultures. The Lysicrates Prize is decided when 500 or so people vote for one of the three would-be plays they have just seen in embryonic form. The performances are 20 minutes long, with- out props. The winner receives a $12,000 com- mission to produce the full-length work, overseen by Griffin Theatre Company artistic director Lee Lewis. This year’s recipient, chosen on March 11 after the prize was held for the first time at the Sydney Opera House, is Travis Cotton for Star- fish, a play about childhood friends. He joins Steve Rodgers, who won the inaug- ural prize in 2015 for his adaptation of Peter Goldsworthy’s book Jesus Wants Me for a Sun- beam, and Mary Rachel Brown, successful last year for a Approximate Balance, a play about addiction. So where are the Greeks in all this? Well, John Azarias (of Alexandrian Greek back- ground) was strolling on a “cheap date” with his wife Patricia when they came across the Ly- sicrates Monument in Sydney’s Royal Botanic Garden, commissioned by James Martin, mid-1800s premier of NSW. The sandstone monument is a reproduction of a bit of the statuary erected in 334BC not far from the Acropolis to mark the fact that one Lysicrates had been a choregos, a wealthy pa- tron of the arts, who had sponsored a play that won first prize in the great dramatic festival of Athens. That festival more or less invented the forms of entertainment by which we define ourselves and to which we aspire. Hence the Lysicrates Prize and hence this gorgeous, underpriced ragbag of a book, Lysi- crates and Martin, in honour of Greek drama and its Sydney shadow. It’s all laid out in arti- cles by notables such as Peter Wilson, pro- fessor of classics at Sydney University, and with addenda contributed by Robin Lane Fox, for instance, the Oxford classical historian who thinks bringing together gardens and Greek tragedy is a tremendous marriage. He’s not wrong. The idea of the theatre we have inherited, of which Shakespeare is the English-language instantiation, is essentially Greek. It is a theatre where the music of the word transcends the literary to create with a concomitant grandeur an absolute clarity of emotion. Think of Sophocles’s Oedipus Rex, the most famous Greek play. “I weep for you, my city,” Oedipus the King says at the outset, “and walk through endless ways of thought.” The endless ways of thought led to finite headstrong acts of folly, as when Oedipus says to the blind seer Tiresias, “You are the cursed polluter of this land.” Not to mention the sublime ironic worldliness of Jocasta, the unwitting wife and mother of the tragic hero, when she says to him comfortingly, of the apparitional nightmare of mother/son incest, “Many a man has dreamt as much.” Laurence Olivier was Oedipus in WB Yeats’s translation with Sybil Thorndike as Jocasta and Ralph Richardson as Tiresias. Ty- rone Guthrie, the Anglo-Irish theatre innova- tor (who once wrote a report on the prospect of an Australian national theatre for prime minis- ter Ben Chifley) did it here in 1970 as an or- chestrated symphony of birdcalls with Ron Haddrick in the title role. Dramatically the Greeks are the ground on which we walk. Judith Anderson, the magnifi- cent Australian actress (Alfred Hitchcock’s Mrs Danvers in Rebecca) did Euripides’s Medea and so did her successor Zoe Caldwell (both can be found on YouTube). Katharine Hepburn was Hecuba in Michael Cacoyannis’s version of Euripides, The Trojan Women. Robyn Nevin did the same for Barrie Kosky in a Sydney Theatre Company/Malt- house production in 2008. Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides each wrote three plays (with a modern running time of 90 minutes or less), which were performed as a sequence under the aegis of the dark and exalted god Dionysus. There’s a lot about Dio- nysus in this book, not least because he’s the lord of the drama. Wilson quotes Ezra Pound’s beautiful translation of one of the Homeric hymns in honour of a shrouded Dionysus: “I have seen what I have seen. When they brought the boy I said, ‘He has a god in him, but I do not know which god’.” The book has magnificent images, on glossy paper, of Dionysus in his many guises. There are full-page pictures of staggering Greek vases and details of the ravishing luminous quality of Greek art. There is also a rambling but interest- ing account of James Martin, a lawyer and pol- itician who was obsessed by the classical ideal. He came from a poor Irish Catholic family in County Cork and, translated to the colonies, he was so enthralled by education that he walked every day from Parramatta to what would eventually become Sydney Grammar. He never saw Greece but his deci- sion to reproduce the Lysicrates monument was probably related to his love of Lord Byron, who stayed in a monastery next to the monu- ment when it was known as the Lantern of Demosthenes and run by monks. Byron read the books in the cramped space and translated Horace’s Exegi monumentum there. The famous Thomas Phillips por- trait of the rock-star poet in Albanian dress is reproduced in this book. It’s not hard to im- agine the crusty old judge warming to lines such as “ ’Tis sweet to hear / At midnight on the blue and moonlit deep / The song and oar of Adria’s gondo- lier.” They all did. HV Evatt, that high- minded, high-hand- ed Labor politician, transferred Martin’s imitation of the Lysi- crates Monument to the Botanic Garden during World War II because he thought it should belong to the people and inspire them in a time of struggle. The Greeks were as interested in their mas- terworks as we are in Star Wars or (if you like) as we used to be in A Streetcar Named Desire or Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf. It’s good that the Azarias have made the Lysicrates a popular award and have also used it as an occasion to promote Greek civilisation in this book. They might consider extending their dra- matic ambition. We are a society deprived of classic theatre, ancient and modern. There would be a real audience for simple readings of the Greek plays by professional actors. The Lysicrates Prize is a reminder that one of the greatest Greek flames, one that perhaps burns even brighter than the Olympic spirit, is central to our heritage. Peter Craven is a literary critic. Greek gift keeps giving An image of Dionysus from the book; below, Griffin Theatre artistic director Lee Lewis with playwright Travis Cotton Two poems by Peter Rose From The Catullan Rag Sappho, no wonder you hid that poem so neatly it stayed lost for centuries. Only among your girls did it pass. Sipping wine they mooned at your craft: ‘skin once soft but wrinkled now … knees, once nimble, unable to carry you to bed’. When you intoned the line about no one who is human being unable to escape old age they filed home, lachrymose. ‘‘No one who is human …’’ Except Suffenus, who being inhuman gamely tries. Last seen he dripped more dye than predacious Aschenbach on the beach. Suffenus must have been soused at the time. Like his art, the black was unevenly applied. Lesbia declares herself happier than she has ever been. This time it’s a witless slam poet from Puglia. Hello must be paying her to torment Catullus? Naked they loll by an infinity pool, only a sparrow for decency – or finch in his case. On the balcony they cuddle in their kaftans. Well, Lesbia has always liked an agile tongue. Nightly she falls asleep to an ostinato of bilge from the unripe Puglian whose only dart is his incessant rhymery. Slam Poet De Senectute

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

22 BOOKS

March 24-25, 2018 theaustralian.com.au/reviewAUSE01Z10AR - V1

Peter Craven Lysicrates and Martin — Two Arts Patrons of History Return to Give Again: Theatre for AllBy The Lysicrates FoundationMUP, 163pp, $35 (HB)

It’s funny what can bring a city together. Whowould have thought Sydney would go madabout the Greeks? It’s happened, though,thanks to an unusual theatre prize establishedby Patricia and John Azarias, a couple of mon-eyed, myriad-minded culture vultures.

The Lysicrates Prize is decided when 500 orso people vote for one of the three would-beplays they have just seen in embryonic form.The performances are 20 minutes long, with-out props. The winner receives a $12,000 com-mission to produce the full-length work,overseen by Griffin Theatre Company artisticdirector Lee Lewis.

This year’s recipient, chosen on March 11after the prize was held for the first time at theSydney Opera House, is Travis Cotton for Star-fish, a play about childhood friends.

He joins Steve Rodgers, who won the inaug-ural prize in 2015 for his adaptation of PeterGoldsworthy’s book Jesus Wants Me for a Sun-beam, and Mary Rachel Brown, successful lastyear for a Approximate Balance, a play aboutaddiction.

So where are the Greeks in all this? Well,John Azarias (of Alexandrian Greek back-ground) was strolling on a “cheap date” withhis wife Patricia when they came across the Ly-sicrates Monument in Sydney’s Royal BotanicGarden, commissioned by James Martin,mid-1800s premier of NSW.

The sandstone monument is a reproductionof a bit of the statuary erected in 334BC not farfrom the Acropolis to mark the fact that oneLysicrates had been a choregos, a wealthy pa-tron of the arts, who had sponsored a play thatwon first prize in the great dramatic festival ofAthens.

That festival more or less invented theforms of entertainment by which we defineourselves and to which we aspire.

Hence the Lysicrates Prize and hence thisgorgeous, underpriced ragbag of a book, Lysi-crates and Martin, in honour of Greek dramaand its Sydney shadow. It’s all laid out in arti-cles by notables such as Peter Wilson, pro-fessor of classics at Sydney University, andwith addenda contributed by Robin Lane Fox,for instance, the Oxford classical historian whothinks bringing together gardens and Greektragedy is a tremendous marriage.

He’s not wrong. The idea of the theatre wehave inherited, of which Shakespeare is theEnglish-language instantiation, is essentiallyGreek. It is a theatre where the music of theword transcends the literary to create with aconcomitant grandeur an absolute clarity ofemotion.

Think of Sophocles’s Oedipus Rex, the mostfamous Greek play. “I weep for you, my city,”Oedipus the King says at the outset, “and walkthrough endless ways of thought.” The endlessways of thought led to finite headstrong acts offolly, as when Oedipus says to the blind seerTiresias, “You are the cursed polluter of thisland.” Not to mention the sublime ironicworldliness of Jocasta, the unwitting wife andmother of the tragic hero, when she says to himcomfortingly, of the apparitional nightmare ofmother/son incest, “Many a man has dreamt asmuch.”

Laurence Olivier was Oedipus in WBYeats’s translation with Sybil Thorndike asJocasta and Ralph Richardson as Tiresias. Ty-rone Guthrie, the Anglo-Irish theatre innova-tor (who once wrote a report on the prospect ofan Australian national theatre for prime minis-ter Ben Chifley) did it here in 1970 as an or-chestrated symphony of birdcalls with RonHaddrick in the title role.

Dramatically the Greeks are the ground onwhich we walk. Judith Anderson, the magnifi-cent Australian actress (Alfred Hitchcock’sMrs Danvers in Rebecca) did Euripides’sMedea and so did her successor Zoe Caldwell(both can be found on YouTube).

Katharine Hepburn was Hecuba in MichaelCacoyannis’s version of Euripides, The TrojanWomen. Robyn Nevin did the same for Barrie

Kosky in a Sydney Theatre Company/Malt-house production in 2008.

Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides eachwrote three plays (with a modern running timeof 90 minutes or less), which were performedas a sequence under the aegis of the dark andexalted god Dionysus. There’s a lot about Dio-nysus in this book, not least because he’s thelord of the drama. Wilson quotes Ezra Pound’sbeautiful translation of one of the Homerichymns in honour of a shrouded Dionysus: “Ihave seen what I have seen. When theybrought the boy I said, ‘He has a god in him,but I do not know which god’.”

The book has magnificent images, on glossypaper, of Dionysus in his many guises. Thereare full-page pictures of staggering Greek vasesand details of the ravishing luminous quality ofGreek art. There is also a rambling but interest-ing account of James Martin, a lawyer and pol-itician who was obsessed by the classical ideal.He came from a poor Irish Catholic family inCounty Cork and, translated to the colonies, hewas so enthralled by education that he walkedevery day from Parramatta to what wouldeventually become Sydney Grammar.

He never saw Greece but his deci-sion to reproduce the Lysicratesmonument was probably related tohis love of Lord Byron, who stayedin a monastery next to the monu-ment when it was known as theLantern of Demosthenes and runby monks. Byron readthe books in thecramped space andtranslated Horace’sExegi monumentumthere. The famousThomas Phillips por-trait of the rock-starpoet in Albaniandress is reproduced inthis book.

It’s not hard to im-agine the crusty oldjudge warming to linessuch as “ ’Tis sweet tohear / At midnight onthe blue and moonlitdeep / The song andoar of Adria’s gondo-lier.”

They all did. HVEvatt, that high-minded, high-hand-ed Labor politician,transferred Martin’simitation of the Lysi-crates Monument to the

Botanic Garden during World War II becausehe thought it should belong to the people andinspire them in a time of struggle.

The Greeks were as interested in their mas-terworks as we are in Star Wars or (if you like)as we used to be in A Streetcar Named Desire orWho’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf. It’s good thatthe Azarias have made the Lysicrates a popularaward and have also used it as an occasion topromote Greek civilisation in this book.

They might consider extending their dra-matic ambition. We are a society deprived ofclassic theatre, ancient and modern. Therewould be a real audience for simple readings ofthe Greek plays by professional actors.

The Lysicrates Prize is a reminder that oneof the greatest Greek flames, one that perhapsburns even brighter than the Olympic spirit, iscentral to our heritage.

Peter Craven is a literary critic.

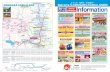

Greek gift keeps givingAn image of Dionysus from the book; below, Griffin Theatre artistic director Lee Lewis with playwright Travis Cotton

Two poems by Peter RoseFrom The Catullan Rag

Sappho, no wonder you hid that poemso neatly it stayed lost for centuries.Only among your girls did it pass.Sipping wine they mooned at your craft: ‘skin once soft but wrinkled now …knees, once nimble, unable to carry you to bed’.When you intoned the line about no one who is human being unable to escape old agethey filed home, lachrymose.‘‘No one who is human …’’ Except Suffenus,who being inhuman gamely tries.Last seen he dripped more dye than predacious Aschenbach on the beach. Suffenus must have been soused at the time.

Like his art, the black was unevenly applied.Lesbia declares herself happier than she has ever been. This timeit’s a witless slam poet from Puglia.Hello must be paying her to torment Catullus?Naked they loll by an infinity pool,only a sparrow for decency – or finch in his case.On the balcony they cuddle in their kaftans.Well, Lesbia has always liked an agile tongue.Nightly she falls asleep to an ostinato of bilge from the unripe Puglianwhose only dart is his incessant rhymery.

Slam Poet

De Senectute

Related Documents