-

7/31/2019 Grading the Government's Data Publication Practices, Cato Policy Analysis No. 711

1/44

Executive Summary

Barack Obama promised transparency andopen government when he campaigned forpresident in 2008, and he took office aiming todeliver it. Today, the federal government is nottransparent, and government transparency hasnot improved materially since the beginning ofPresident Obamas administration. This is notdue to lack of interest or effort, though. Alongwith meeting political forces greater than his

promises, the Obama transparency tailspin wasa product of failure to apprehend what trans-parency is and how it is produced.

A variety of good data publication practicescan help produce government transparency: au-thoritative sourcing, availability, machine-dis-coverability, and machine-readability. The CatoInstitute has modeled what data the govern-

ment should publish in the areas of legislativeprocess and budgeting, spending, and appro-priating. The administration and the Congressboth receive fairly low marks under systematicexamination of their data publication practices.

Between the Obama administration andHouse Republicans, the former, starting froma low transparency baseline, made extravagantpromises and put significant effort into the

project of government transparency. It has notbeen a success. House Republicans, who man-age a far smaller segment of the government,started from a higher transparency baseline,made modest promises, and have taken limitedsteps to execute on those promises. PresidentObama lags behind House Republicans, butboth have a long way to go.

Grading the GovernmentsData Publication Practices

by Jim Harper

No. 711 November 5, 2012

Jim Harper is director of information policy studies at the Cato Institute and the webmaster of WashingtonWatch.com.

-

7/31/2019 Grading the Government's Data Publication Practices, Cato Policy Analysis No. 711

2/44

2

There was nolack of effort or

creativity arounddata transparency

at the outsetof the Obama

Administration.

Introduction

As a campaigner in 2008, PresidentObama promised voters hope, change, andtransparency.1 Within minutes of his tak-

ing office on January 20, 2009, in fact, theWhitehouse.gov website declared: Presi-dent Obama has committed to making hisadministration the most open and transpar-ent in history.2 His first presidential mem-orandum, issued the next day, was entitledTransparency and Open Government. Itdeclared:

My Administration is committed tocreating an unprecedented level ofopenness in Government. We will

work together to ensure the publictrust and establish a system of trans-parency, public participation, and col-laboration. Openness will strengthenour democracy and promote efficiencyand effectiveness in Government.3

The road to government transparency islong. Nearly four years later, few would ar-gue that American democracy has materi-ally strengthened, or that the government isany more effective and efficient, due to for-

ward strides in transparency and openness.Indeed, the administration has come underfire recentlyas every administration does,it seemsfor significant transparency fail-ings.

Freedom of Information Act (FOIA)policy is an example. In its early days, theObama administration committed to im-proving the governments FOIA practices. InMarch 2009 Attorney General Eric Holderissued a widely lauded memorandum order-ing improvements in FOIA compliance.4 But

this September, Bloomberg news reportedon its test of the Obama Administrationscommitment to transparency under FOIA.Bloomberg found that 19 of 20 cabinet-levelagencies disobeyed the public disclosure lawwhen it asked for information about the costof agency leaders travel. Just 8 of 57 federalagencies met Bloombergs request for docu-

ments within the 20-day disclosure windowrequired by the act.5

President Obamas campaign promiseto post laws to the White House websitefor five days of public comment before he

signed them went virtually ignored by theWhite House in the first year of his admin-istration. Only recently has he reached two-thirds compliance with the Sunlight BeforeSigning promise, and this is because of themultitude of bills Congress passes to renamepost offices and such. More important billsare often given less than the promised fivedays sunlight.6

There was no lack of effort or creativityaround data transparency at the outset ofthe Obama Administration. In May 2009

White House officials announced on thenew Open Government Initiative blog thatthey would elicit the publics input into theformulation of its transparency policies. Ina meta-transparency flourish, the publicwas invited to join in with the brainstorm-ing, discussion, and drafting of the govern-ments policies.7

The conspicuously transparent, participa-tory, and collaborative process contributedsomething, evidently, to an Open Govern-ment Directive, issued in December 2009

by Office of Management and Budget headPeter Orszag.8 Its clear focus was to give thepublic access to data. The directive orderedagencies to publish within 45 days at leastthree previously unavailable high-valuedata sets online in an open format and toregister them with the federal governmentsdata portal, Data.gov. Each agency was tocreate an Open Government Webpage asa gateway to agency activities related to theOpen Government Directive.

Many, many of President Obamas trans-

parency promises went by the wayside. Hisguarantee that health care legislation wouldbe negotiated around a big table and tele-vised on C-SPAN was quite nearly the op-posite of what occurred.9 People are free toobserve whether it is political immaturity,idealism, or dishonesty that prompted trans-parency promises of this kind. Whatever the

-

7/31/2019 Grading the Government's Data Publication Practices, Cato Policy Analysis No. 711

3/44

3

Celebratedthough it is,transparencyis not awell-definedconcept.

case, history may show that the high-valuedata set challenge was where the ObamaAdministrations data transparency effortbegan its tailspin.

Celebrated though it is, transparency is

not a well-defined concept, and the admin-istrations most concerted effort to deliver itmissed the mark. The reason is that the defi-nition of high-value data set it adoptedwas hopelessly vague:

High-value information is informa-tion that can be used to increaseagency accountability and responsive-ness; improve public knowledge ofthe agency and its operations; furtherthe core mission of the agency; cre-

ate economic opportunity; or respondto need and demand as identifiedthrough public consultation.

Essentially anything agencies wanted topublish they could publish claiming highvalue for it.

Agencies adopted a passive-aggressiveattitude toward the Data.gov effort, accord-ing to political scientist Alon Peled.10 Theytechnically complied with the requirementsof the Open Government Memorandum,

but did not select data that the public valued.The Open Government Directive al-

lowed agencies to exploit a subtle shiftin vocabulary in the area of open govern-ment. They diverted the project away fromthe core government transparency that thepublic found so attractive about PresidentObamas campaign claims. The term opengovernment data might refer to data thatmakes the government as a whole moreopen (that is, more publicly accountable),write Harlan Yu and David Robinson, or

instead might refer to politically neutralpublic sector disclosures that are easy toreuse, even if they have nothing to do withpublic accountability.11

The Agriculture department publisheddata about the race, ethnicity, and genderof farm operators, for example, rather thanabout the funds it spent to collect that kind

of information. An informal Cato Institutestudy examining agencies high-value datafeeds found, almost uniformly, the agenciescame up with interesting databut interest-ing is in the eye of the beholder. And inter-

esting data collected by an agency doesntnecessarily give the insight into governmentwe were looking for.12

Genuinely high-value data for purposesof government transparency would provideinsight in three areas not found in many ofthe early Data.gov feeds. True high-valuedata would be about government entitiesmanagement, deliberations, or results.13

Open data can be a powerful force forpublic accountability, write Yu and Robin-son, It can make existing information easier

to analyze, process, and combine than everbefore, allowing a new level of public scru-tiny.14 This is undoubtedly true, and Ameri-cans have experienced vastly increased accessto information in so many walks of lifeshopping, news-gathering, and investments,to name just three. Data-starved public over-sight of government appears sorely lackingin comparison.

In September a new transparency-relatedinternational initiative took center stage forthe administration, the Open Government

Partnership (OGP).15 This multilateral ini-tiative was created to promote transparen-cy, fight corruption, strengthen accountabil-ity, and empower citizens.16 Participatingcountries pledged to undertake meaningfulnew steps as part of a concrete action plan,developed and implemented in close con-sultation with their citizens. The OGP web-site touts a panoply of meetings, plans, andsocial media outreach efforts, and a recentgraphic displayed on the home page said inbold letters, From Commitment to Action.

Its authors probably have no sense of theirony in that declaration. Significant actions,after all, announce themselves.

Nothing about the OGP is harmful, and itmay produce genuine gains for openness inparticipating countries. However, it has notproduced, and does not hold out, the funda-mental changedata-oriented changethat

-

7/31/2019 Grading the Government's Data Publication Practices, Cato Policy Analysis No. 711

4/44

4

The transparencyproblem is far

from solved.

was at the heart of President Obamas cam-paign promises.

The Obama administration is not theonly actor on the federal stage, of course.House Republicans made transparency

promises of their own in the course of theircampaign to retake control of the House ofRepresentatives, which they did in 2011.

The lack of transparency in Congresshas been a problem for generations, undermajorities Republican and Democrat alike,said aspiring House speaker John Boehner(R-OH) in late 2009. But with the advent ofthe Internet, its time for this to change.17

Since 1995, the Library of CongresssTHOMAS website has published informa-tion, sometimes in the form of useful data,

about Congress and its activities. Upon tak-ing control of the House for the first time in40 years, the Republican leadership of the104th Congress directed the Library of Con-gress to make federal legislative informationfreely available to the public. The offeringson the site now include bills, resolutions,activity in Congress, the Congressional Record,schedules, calendars, committee informa-tion, the presidents nominations, and trea-ties.18

In an attempt to improve the availabil-

ity of key information, at the beginning ofthe 112th Congress the House instituted arulenot always complied withthat billsshould be posted online for three calendardays before receiving a vote on the Housefloor.19 The House followed up by creatinga site at data.house.gov where such bills areposted. In February 2012 the House Com-mittee on Administration held a day-longconference on legislative data,20 evidenceof continuing interest and of plans to moveforward. And in September, the Library of

Congress debuted beta.congress.gov, whichis slated to be the repository for legislativedata that ultimately replaces the THOMASwebsite.21

Between the Obama administration andHouse Republicans, the former, startingfrom a low transparency baseline, made ex-travagant promises and put significant ef-

fort into the project of government trans-parency. It has not been a success. HouseRepublicans, who manage a far smallersegment of the government, started from ahigher transparency baseline, made modest

promises, and have taken limited steps to ex-ecute those promises.The transparency problem is far from

solved, of course. The information that thepublic would use to increase their oversightand participation is still largely inaccessibleThe Republican House may be ahead, butboth the administration and Congress scorepoorly under systematic examination oftheir data publication practices.

The Data that Would Make for

Transparent GovernmentIt was not disinterest that caused theObama administration transparency effort tofade. Arguably, it was the failure of the trans-parency community to ask clearly for whatit wants: good data about the deliberations,management, and results of government en-tities and agencies. So in January 2011 theCato Institute began working with a widevariety of groups and advisers to modelgovernmental processes as data and then toprescribe how this data should be published.

Data modeling is arcane stuff, but it isworth understanding here at the dawn ofthe Information Age. Data is collectedabstract representations of things in theworld. We use the number 3, for example,to reduce a quantity of things to an abstract,useful forman item of data. Because clerkscan use numbers to list the quantities offruits and vegetables on hand, store manag-ers can effectively carry out their purchas-ing, pricing, and selling instead of spendingall of their time checking for themselves

how much of everything there is. Datamakes everything in life a little easier andmore efficient for everyone.

Legislative and budgetary processes arenot a grocery stores produce department, ofcourse. They are complex activities involvingmany actors, organizations, and steps. TheCato Institutes modeling of these processes

-

7/31/2019 Grading the Government's Data Publication Practices, Cato Policy Analysis No. 711

5/44

5

Four key datapractices supporgovernmenttransparency:

authoritativesourcing,availability,machine-discoverability,and machine-readability.

reduced everything to entities, each hav-ing various properties. The entities andtheir properties describe the things in legis-lative and budgetary processes and the logi-cal relationships among them, like members

of Congress, the bills they introduce, hear-ings on the bills, amendments, votes, and soon. The entity and property terminol-ogy corresponds with usage in the world ofdata management, it is used to make codingeasier for people in that field, and it helpsto resolve ambiguities in translating govern-mental processes into useful data. The mod-eling was restricted to formal parts of theprocesses, excluding, for example, the variedorganizations that try to exert influence, in-formal communications among members

of Congress, and so on.The project also loosely defined severalmarkup types, guides for how documentsthat come out of the legislative processshould be structured and published to maxi-mize their utility. The models and markuptypes are discussed in a pair of Cato@Libertyblog posts that also issued preliminary gradeson the quality of data publication about theentities.22 The models and markup types forlegislative data and budgeting/appropria-tions/spending data can be found in Appen-

dixes A and B, respectively.Next, the project examined the publica-

tion methods that allow data to reach itshighest and best use. Four key data prac-tices that support government transparencyemerged. Documented in a Cato InstituteBriefing Paper entitled Publication Practicesfor Transparent Government,23 those prac-tices are authoritative sourcing, availability,machine-discoverability, and machine-read-ability.

Authoritative sourcing means producing

data as near to its original source and time aspossible, so that the public uniformly comesto rely on the best sources of data. The sec-ond transparent data practice, availability,entails consistency and confidence in data,including permanence, completeness, andgood updating practices.

The third transparent data practice,

machine-discoverability, occurs when infor-mation is arranged so that a computer candiscover the data and follow linkages amongit. Machine-discoverability exists when datais presented consistently with a host of cus-

toms about how data is identified and refer-enced, the naming of documents and files,the protocols for communicating data, andthe organization of data within files.

The fourth transparent data practice,machine-readability, is the heart of trans-parency because it allows the many mean-ings of data to be discovered. Machine-readable data is logically structured so thatcomputers can automatically generate themyriad stories that the data has to tell andput it to the hundreds of uses the public

would make of it in government oversight.A common and popular language for struc-turing and containing data is called XML,or eXtensible Markup Language, whichis a relative of HTML (hypertext markuplanguage), the language that underlies theWorld Wide Web.

Beginning in September 2011 the projectgraded how well Congress and the adminis-tration publish data about the key entitiesin the processes they oversee. Congress is re-sponsible for data pertaining to the legisla-

tive process, of course. The administrationhas the bulk of the responsibility for budget-related data (except for the congressionalbudgets and appropriations). These gradesare available in a pair of Cato@Liberty blogposts24 and in Appendixes C and D.

With the experience of the past year, theproject returned to grading in September2012. With input from staff at GovTrack.us, the National Priorities Project, OMBWatch, and the Sunlight Foundation (theirendorsement of the grades not implied by

their assistance), we assessed how well datais now published. The grades presented inFigures 1 and 2 are largely consistent withthe prior yearlittle changed between thetwo grading periodsbut there were somechanges in grades in both directions due toimprovements in publication, discovery ofdata sources by our panel of graders, and

-

7/31/2019 Grading the Government's Data Publication Practices, Cato Policy Analysis No. 711

6/44

6

Governmenttransparency is

a widely agreed-upon value,

sought after asa means toward

various ends.

heightened expectations. Incompletesgiven in the first year of grading became Fsin some cases and Ds in others.

It is important to highlight that gradesare a lagging indicator. Transparency is not

just a product of good data publication, butalso of the societys ability to digest and useinformation. Once data feeds are published,it takes a little while for the community ofusers to find them and make use of them.A new web site dedicated to congressionalinformation, beta.congress.gov, will un-doubtedly improve data transparency andthe grades for data it publishes, assuming itlives up to expectations.

Government transparency is a widelyagreed-upon value, sought after as a means

toward various ends. Libertarians and con-servatives support transparency becauseof their belief that it will expose waste andbloat in government. If the public under-stands the workings and failings of govern-ment better, the demand for governmentsolutions will fall and democracy will pro-duce more libertarian outcomes. Americanliberals and progressives support transpar-ency because they believe it will validate andstrengthen government programs. Trans-parency will root out corruption and pro-

duce better outcomes, winning the publicsaffection and support for government.

Though the goals may differ, pan-ideo-logical agreement on transparency can re-main. Libertarians should not prefer largegovernment programs that are failing. Iftransparency makes government work bet-ter, that is preferable to government work-ing poorly. If the libertarian vision pre-vails, on the other hand, and transparencyproduces demand for less government andgreater private authority, that will be a re-

sult of democratic decisionmaking that lib-erals and progressives should respect andhonor.

With that, here are the major entities inthe legislative process and in budgeting, ap-propriating, and spending; the grades thatreflect the quality of the data publishedabout them; and a discussion of both.

Publication Practices forTransparent Government:

Rating Congress

House Membership: C-Senate Membership: A-It would seem simple enough to publish

data about who holds office in the House ofRepresentatives and Senate, and it is. Thereare problems with the way the data is pub-lished, though, which the House and Senatecould easily remedy.

On the positive sideand this is not tobe discountedthere is a thing called theBiographical Directory of the United StatesCongress, a compendium of information

about all present and former members ofthe U.S. Congress (as well as the ContinentalCongress), including delegates and residentcommissioners. The Bioguide website atbioguide.congress.gov is a great resource forsearching out historical information.

But there is little sign that Bioguide isCongresss repository of record, and it islittle known by users, giving it lower author-ity marks than it should have. Some lookto the House and Senate websites and betacongress.gov for information about federal

representatives, splitting authority amongwebsites, rather than one established andagreed upon resource.

Bioguide scores highly on availabilitywe know of no problems with up-time orcompleteness (though it could use quickerupdating when new members are elected)Bioguide is not structured for discoverabil-ity, though. Most people have not seen it,because search engines are not finding it.

Bioguide does a good thing in terms ofmachine readability, though. It assigns a

unique ID to each of the people in its data-base. This is the first, basic step in makingdata useful for computers, and the Biogu-ide ID should probably be the standard formachine identification of elected officialswherever they are referred to in data. Unfor-tunately, the biographical content in Biogu-ide is not machine-readable.

-

7/31/2019 Grading the Government's Data Publication Practices, Cato Policy Analysis No. 711

7/44

7

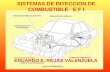

Publication Practices for Transparent

Government: Rating the Congress

How well can the Internet access data about Congress work? The Cato Institute rated how well Congress publishesinformation in terms of authoritative sourcing, availability, machine-discoverability, and machine-readability.

S U B J E C T GR A D E CO M M E N T S

House and SenateMembership

House C-Senate A-

The Senate has taken the lead on making dataabout who represents Americans in Washingtonmachine-readable.

Committees and

Subcommittees C-

Organizing and centralizing committee informa-tion would create a lot of clarity with a minimumof effort.

Meetings of House,Senate, and Committees

Meeting Records

House BSenate B

D-

The House has improved its data about floordebates. The Senate is strong on commiteemeetings.

There is lots of work to do before transcripts andother meeting records can be called transparent.

Committee Reports

Bills

Amendments

Motions

C+

B-

F

Committee reports can be found, but theyre not

machine-readable.

Bills are the pretty-good-news story inlegislative transparency, though there is room

for improvement.

Amendments are hard to track in any systematicwayand Congress has done little to make themtrackable.

If the public is going to have insight into thedecisions Congress makes, the motions on whichCongress acts should be published as data.

Decisions and Votes B+Vote information is in good shape, but voice votesand unanimous consents should be published asdata.

Communications(Inter- and Intra-Branch) F

Transparent access to the messages sent amongthe House, Senate, and executive branch wouldcomplete the picture available to the public.

F

October 2012

Figure 1

-

7/31/2019 Grading the Government's Data Publication Practices, Cato Policy Analysis No. 711

8/44

8

Publication Practices for Transparent Government:

Budgeting, Appropriating, and Spending

How well can the Internet access data about the federal governments budgeting, appropriating, and spending?The Cato Institute rated how well the government publishes information in terms of authoritative

sourcing, availability, machine-discoverability, and machine-readability.

S U B J E C T G R A D E CO M M E N T S

AgenciesThis grade is generous. There really shouldbe a machine-readable federal governmentorganization chart.

Bureaus D- The sub-units of agencies have the same problem.

Programs

Projects

D

F

Program information is obscure, incomplete,and unorganized.

Some project information gets published, butthe organization of it is bad.

Budget Documents

Budget Authority

Warrants, Apportion-ments, and Allocations

Obligations

CongressD

White House B-

F

F

The presidents budget submission and congres-sional budget resolutions are a mixed bag.

Legal authority to spend is hidden andunstructured.

Spending authority is divided up in anopaque way.

Commitments to spend taxpayer money arevisible some places.

Parties F A proprietary identifier system makes it hardto know where the money is going.

Outlays C- We need real-time, granular spending data.

B-

October 2012

D-

Figure 2

-

7/31/2019 Grading the Government's Data Publication Practices, Cato Policy Analysis No. 711

9/44

9

There should beone and only onauthoritative,

well-publishedsource ofinformationabout Houseand Senatemembership.

As noted above, the other ways of learn-ing about House and Senate membershipare ad hoc. The Government Printing Officehas a Guide to House and Senate Membersat http://memberguide.gpo.gov/ that du-

plicates information found elsewhere. TheHouse website presents a list of membersalong with district information, party affili-ation, and so on, in HTML format (http://www.house.gov/representatives/), and beta.congress.gov does as well (http://beta.congress.gov/members/). Someone who wantsa complete dataset must collect data fromthese sources using a computer program toscrape the data and through manual cura-tion. The HTML presentations do not breakout key information in ways useful for com-

puters. The Senate membership page,25

onthe other hand, includes a link to an XMLrepresentation that is machine readable.That is the reason why the Senate scores sowell compared to the House.

Much more information about our rep-resentatives flows to the public via repre-sentatives individual websites. These arenonauthoritative websites that search en-gine spidering combines to use as a record ofthe Congresss membership. They are avail-able and discoverable, again because of that

prime house.gov and senate.gov real estate.But they only reveal data about the mem-bership of Congress incidentally to com-municating the press releases, photos, andannouncements that representatives want tohave online.

It is a narrow point, but there should beone and only one authoritative, well-pub-lished source of information about Houseand Senate membership from which allothers flow. The variety of sources that ex-ist combine to give Congress pretty good

grades on publishing information aboutwho represents Americans in Washington,but improving in this area is a simple mat-ter of coordinated House and Senate efforts.

Committees and Subcommittees: C-Like Americans representation in Con-

gress, lists of committees, their membership,

and jurisdiction should be an easy lift. But itis not as easy as it should be to learn aboutthe committees to which Congress delegatesmuch of its work and the subcommittees towhich the work gets further distributed.

The Senate has committee names andURLs prominently available on its mainwebsite.26 The House does, too, at http://house.gov/committees/. But neither pageoffers machine-readable information aboutcommittees and committee assignments.The Senate has a nice list of committee as-signments, again, though, not machine-readable. The House requires visitors toclick through to each committees web pageto research what they do and who serves onthem. For that, youd go to individual com-

mittee websites, each one different fromthe others. There is an authoritative list ofHouse committees with unique identifi-ers,27 but its published as a PDF, and it isnot clear that it is used elsewhere for refer-ring to committees.

Without a recognized place to go to getdata about committees, this area suffersfrom lacking authority. To the extent thereare data, availability is not a problem, butmachine-discoverability suffers for havingeach committee publish distinctly, in for-

mats like HTML, who their members are,who their leaders are, and what their juris-diction is.

With the data scattered about this way,the Internet cant really see it. More promi-nence, including data such as subcommit-tees and jurisdiction, and use of a recog-nized set of standard identifiers would takethis resource a long way.

Until committee data are centrally pub-lished using standard identifiers (for bothcommittees and their members), machine-

readability will be very low. The Internetmakes sense of congressional committeesas best it can, but a whole lot of organizingand centralizingwith a definitive, always-current, and machine-readable record ofcommittees, their memberships, and theirjurisdictionswould create a lot of clarity inthis area with a minimum of effort.

-

7/31/2019 Grading the Government's Data Publication Practices, Cato Policy Analysis No. 711

10/44

10

Can the publiclearn easily about

what meetingsare happening,

where they arehappening,

when they arehappening, and

what they areabout? It depends

on which sideof the Capitol

youre on.

Meetings of House, Senate, andCommitteesHouse: B/Senate: B

When the House, the Senate, committees,and subcommittees have their meetings, thebusiness of the people is being done. Can

the public learn easily about what meetingsare happening, where they are happening,when they are happening, and what they areabout? It depends on which side of the Capi-tol youre on.

The Senate is pretty good about publish-ing notices of committee meetings. From awebpage with meeting notices listed on it,28there is a link to an XML version of the datato automatically inform the public.

If a particular issue is under consider-ation in a Senate committee meeting, this is

a way for the public to learn about it. Thisis authoritative, it is available, it is machine-discoverable, and has some machine-read-able features. That means any application,website, researcher, or reporter can quicklyuse these data to generate moreand moreusefulinformation about Congress.

The House does not have anything similarfor committee meetings. To learn about thosemeetings, one has to scroll through page af-ter page of committee announcements orcalendars. Insiders subscribe to paid services.

The House can catch up with the Senate inthis area.

Where the House excels and the Senatelags is in notice about what will be consid-ered on the floor. The House made greatstrides with the institution of docs.house.gov, which displays legislation heading forthe floor. This allows any visitor, and vari-ous websites and services, to focus theirattention on the nations business for theweek.

Credit is due the House for establish-

ing this resource and using it to inform thepublic using authoritative, available, and ma-chine-discoverable and -readable data. This isan area where the Senate has the catching upto do.

For different reasons, the House and Sen-ate both garner Bs. Were they to copy thebest of each other, they would both have As.

Meeting Records: D-There is a lot of work to do before meet-

ing records can be called transparent. TheCongressional Record is the authoritative re-cord of what transpires on the House and

Senate floors, but nothing similar revealsthe content of committee meetings. Thosemeeting records are produced after muchdelaysometimes an incredibly long de-layby the committees themselves. Theserecords are obscure, and they are not beingpublished in ways that make things easy forcomputers to find and comprehend.

In addition, the Congressional Recorddoesnt have the machine-discoverable pub-lication or machine-readable structure thatit could and should. Giving unique, consis-

tent IDs in the Recordto members of Con-gress, to bills, and other regular subjects ofthis publication would go a long way to im-proving it. The same would improve tran-scripts of committee meetings.

Another form of meeting record ex-ists: videos. These have yet to be standard-ized, organized, and published in a reliableand uniform way, but the HouseLive site(http://houselive.gov/) is a significant stepin the right direction. It will be of greateruse when it can integrate with other re-

cords of Congress. Real-time flagging ofmembers and key subjects of debate in thevideo stream would be a great improve-ment in transparency. Setting video andvideo meta-data standards for use by bothHouses of Congress, by committees, and bysubcommittees would improve things dra-matically.

House video is a bright spot in a very darkfield, but both will shine brighter in time.When the surrounding information envi-ronment has improved to educate the pub-

lic about goings-on in Congress in real time,the demand for and usefulness of video willincrease.

Committee Reports: C+Committee reports are important parts

of the legislative process, documenting thefindings and recommendations that com-

-

7/31/2019 Grading the Government's Data Publication Practices, Cato Policy Analysis No. 711

11/44

11

Bills are apretty-good-news storyin legislativetransparency.

mittees report to the full House and Senate.They do see publication on the most au-thoritative resource for committee reports,the Library of Congresss THOMAS system.They are also published by the Government

Printing Office.

29

The GPOs Federal Digi-tal System (FDsys) is relatively new and ismeant to improve systematic access to gov-ernment documents, but it has not becomerecognized as an authoritative source formany of those documents.

Because of the sources through whichthey are published, committee reports aresomewhat machine-discoverable, but with-out good semantic information embeddedin them, committee reports are barely visibleto the Internet.

Rather than publication in HTML andPDF, committee reports should be pub-lished fully marked up with the array ofsignals that reveal what bills, statutes, andagencies they deal with, as well as authori-zations and appropriations, so that the In-ternet can discover and make use of thesedocuments.

Bills: B-Bills are a pretty-good-news story in

legislative transparency. Most are promptly

published. It would be better, of course, ifthey were all immediately published at themoment they were introduced, and if boththe House and Senate published last-min-ute, omnibus bills before debating and vot-ing on them.

A small gap in authority exists aroundbills. Some people look to the Library ofCongress and the THOMAS site, and nowbeta.congress.gov, for bill information. Oth-ers look to the Government Printing Office.Which is the authority for bill content? This

issue has not caused many problems so far.Once published, bill information remainsavailable, which is good.

Publication of bills in HTML on theTHOMAS site makes them reasonably ma-chine-discoverable. Witness the fact thatsearching for a bill will often turn up theversion at that source.

Where bills could improve some is intheir machine-readability. Some informa-tion such as sponsorship and U.S. code ref-erences is present in the bills that are pub-lished in XML, and nearly all bills are now

published in XML, which is great. Muchmore information should be publishedmachine-readably in bills, though, suchas references to agencies and programs, tostates or localities, to authorizations andappropriations, and so on, referred to usingstandard identifiers.

With the work that the THOMAS systemdoes to gather information in one place, billdata are good. This is relative to other, less-well-published data, though. There is yetroom for improvement.

Amendments: FAmendments are not the good-news sto-

ry that bills are. They are barely available,says Eric Mill of the Sunlight Foundation.Given that amendments (especially in theSenate) can be as large and important asoriginal legislation, this is an egregious over-sight.

With a few exceptions, amendments arehard to track in any systematic way. Whenbills come to the House and Senate floors,

amendment text is often available, butamendments are often plopped somewherein the middle of the Congressional Recordwithout any reliable, understood, machine-readable connection to the underlying leg-islation. It is very hard to see how amend-ments affect the bills they would change.

In committees, the story is quite a bitworse. Committee amendments are almostcompletely opaque. There is almost no pub-lication of amendments at allcertainly notamendments that have been withdrawn or

defeated. Some major revisions in processare due if committee amendments are goingto see the light of day as they should.

Motions: FWhen the House, the Senate, or a com-

mittee is going to take some kind of action,it does so on the basis of a motion. If the

-

7/31/2019 Grading the Government's Data Publication Practices, Cato Policy Analysis No. 711

12/44

12

Voting putsmembers ofCongress on

record aboutwhere they stand.And happily, vote

information isin pretty good

shape.

public is going to have insight into the deci-sions Congress makes, it should have accessto the motions on which Congress acts.

But motions are something of a blackhole. Many of them can be found in the Con-

gressional Record, but it takes a human whounderstands legislative procedure and whois willing to read the Congressional Recordtofind them. That is not modern transpar-ency.

Motions can be articulated as data. Thereare distinct types of motions. Congress canpublish which meeting a motion occurs in,when the motion occurs, what the proposi-tion is, what the object of the motion is, andso on. Along with decisions, motions are keyelements of the legislative process. They can

and should be published as data.

Decisions and Votes: B+When a motion is pending, a body such

as the House, the Senate, or a committee willmake a decision on it, only sometimes usingvotes. These decisions are crucial momentsin the legislative process, which should bepublished as data. Like motions, many de-cisions are not yet published usefully. Deci-sions made without a vote in the House orSenate are published in text form as part

of the Congressional Record, but they are notpublished as data, so they remain opaqueto the Internet. Many, many decisions comein the form of voice votes, unanimous con-sents, and so on.

Voting puts members of Congress on re-cord about where they stand. And happily,vote information is in pretty good shape.Each chamber publishes data about votes,meaning authority is well handled. Vote dataare available and timely.

Both the House30 and Senate31 produce

vote information. The latter also publishesroll call tables in XML, which is useful forcomputer-aided oversight. Overall, votingdata are pretty well handled. But the omis-sion of voice votes and unanimous consentsdrags the grade down and will drag it downfurther as the quality of data publication inother areas rises.

Communications (Inter- and Intra-Branch): F

The Constitution requires each house ofCongress to keep a Journal of its Proceed-ings, and from time to time publish the same.

The basic steps in the legislative process (dis-cussed elsewhere) go into the journals of theHouse and Senate, along with communica-tions among governmental bodies.

These messages, sent among the House,Senate, and Executive Branch, are essentialparts of the legislative process, but they donot see publication. Putting these commu-nications onlineincluding unique identi-fiers, the sending and receiving body, anymeeting that produced the communicationthe text of the communication, and key sub-

jects such as billswould complete the pic-ture that is available to the public.

Publication Practices forTransparent Government:

Budgeting, Appropriations,and Spending

Agencies: D-Federal agencies are the agents of Con-

gress and the president. They carry out feder-al policy and spending decisions. According-ly, one of the building blocks of data aboutspending is going to be a definitive list of theorganizational units that do the spending.

Is there such a list? Yes. Its Appendix Cof OMB Circular A-11, entitled: Listing ofOMB Agency/Bureau and Treasury Codes.This is a poorly organized PDF documentthat is found on the Office of Managementand Budget website.32

Poorly organized PDFs are not good

transparency. Believe it or not, there is stillno federal government organization chartthat is published in a way amenable to com-puter processing.

There are almost certainly sets of distinctidentifiers for agencies that both the Trea-sury department and the Office of Manage-ment and Budget use. With modifications

-

7/31/2019 Grading the Government's Data Publication Practices, Cato Policy Analysis No. 711

13/44

13

Believe it ornot, there isstill no federalgovernment

organizationchartpublished in away amenableto computerprocessing.

either of these could be published as theexecutive branchs definitive list of its agen-cies. But nobody has done that. Nobodyseems yet to have thought of publishingdata about the basic units of the executive

branch online in a machine-discoverableand machine-readable format.In our preliminary grading, we gave this

category an incomplete rather than an F.That was beyond generous, according toBecky Sweger of the National Priorities Proj-ect. We expect improvement in publicationof this data, and the grades will be low untilwe get it.

Bureaus: D-The sub-units of agencies are bureaus,

and the situation with agencies applies todata about the offices where the work ofagencies get divided up. Bureaus have iden-tifiers. Its just that nobody publishes a listof bureaus, their parent agencies, and otherkey information for the Internet-connectedpublic to use in coordinating its oversight.

Again, a prior incomplete in this areahas converted to a D-, saved from being anF only by the fact that there is a list, howeverpoorly organized and published, by the Of-fice of Management and Budget.

Programs: DIt is damning with faint praise to call

programs the brightest light on the orga-nizational-data Christmas tree. The work ofthe government is parceled out for actual ex-ecution in programs. Like information abouttheir parental units, the agencies and bu-reaus, data that identifies and distinguishesprograms is not comprehensively published.

Some information about programs isavailable in usable form. The Catalog of Fed-

eral Domestic Assistance website (www.cfda.gov) has useful aggregation of some informa-tion on programs, but the canonical guideto government programs, along with the bu-reaus and agencies that run them, does notexist.

Programs will be a little bit heavier a liftthan agencies and bureausthe number of

programs exceeds the number of bureausby something like an order of magnitude,much as the number of bureaus exceeds thenumber of agencies. And it might be thatsome programs have more than one agency/

bureau parent. But todays powerful com-puters can keep track of these thingstheycan count pretty high. The governmentshould figure out all the programs it has,keep that list up to date, and publish it forpublic consumption.

Thanks to the CFDA, data publicationabout the federal governments programsgets a D.

Projects: FProjects are where the rubber hits the

road. These are the organizational vehiclesthe government uses to enter into contractsand create other obligations that deliver ongovernment services. Some project informa-tion gets published, but the publication is sobad that we give this area a low grade indeed.

Information about projects can be found.You can search for projects by name onUSASpending.gov, and descriptions of proj-ects appear in USASpending/FAADS down-loads, (FAADS is the Federal AssistanceAward Data System), but there is no canoni-

cal list of projects that we could find. Thereshould be, and there should have been for along time now.

The generosity and patience we showedin earlier grading with respect to agencies,budgets, and programs has run out. Theresmore than nothing here, but projects, so es-sential to have complete information about,gets an F.

Budget DocumentsCongress: D/White House: B-

The presidents annual budget submis-sion and the congressional budget resolu-tions are the planning documents that thepresident and Congress use to map the di-rection of government spending each year.These documents are published authorita-tively, and they are consistently available,which is good. They are sometimes machine-

-

7/31/2019 Grading the Government's Data Publication Practices, Cato Policy Analysis No. 711

14/44

14

Ideally, therewould be a nice,neat connection

from budgetauthority rightdown to every

outlay of funds.

discoverable, but they are not terribly ma-chine-readable.

The appendices to the presidents budgetare published in XML format, which vastlyreduces the time it takes to work with the

data in them. Thats really good. But the con-gressional budget resolutionswhen they ex-isthave no similar organization, and thereis low correspondence between the budgetresolutions that Congress puts out and thebudget the president puts out. You wouldthink that a personor better yet, a comput-ershould be able to lay these documentsside by side for comparison, but nobody can.

For its use of XML, the White House getsa B-. Congress gets a D.

Budget Authority: FBudget authority is a term of art forwhat probably should be called spendingauthority. Its the power to spend money,created when Congress and the presidentpass a law containing such authority.

Proposed budget authority is pretty darnopaque. The bills in Congress that containbudget authority are consistently publishedonlinethats goodbut they dont high-light budget authority in machine-readableways. No computer can figure out how

much budget authority is out there in pend-ing legislation.

Existing budget authority is pretty welldocumented in the Treasury DepartmentsFAST book (Federal Account Symbols andTitles). This handy resource lists Treasuryaccounts and the statutes and laws that pro-vide their budget authority. The FAST bookis not terrible, but the only form weve foundit in is PDF. PDF is terrible. And nobodyamong our graders uses the FAST book.

Congress can do a lot better, by high-

lighting budget authority in bills in a ma-chine-readable way. The administration cando much, much better than publishing theobscure FAST book in PDF.

Ideally, there would be a nice, neat con-nection from budget authority right downto every outlay of funds, and back up againfrom every outlay to its budget authority.

These connections, published online in use-ful ways, would allow public oversight toblossom. But the seeds have yet to be plant-ed.

Warrants, Apportionments, andAllocations: FAfter Congress and the president create

budget authority, that authority gets divviedup to different agencies, bureaus, programsand projects. How well documented are theseprocesses? Not well.

An appropriation warrant is an assignment of funds by the Treasury to a treasuryaccount to serve a particular budget author-ity. Its the indication that there is money inan account for an agency to obligate and then

spend. OMB has a web portal that agen-cies used to send apportionment requests,notes the National Priorities Projects BeckySweger, so the apportionment data are outthere.

Where is this warrant data? We cant findit. Given Treasurys thoroughness, it proba-bly exists, but its just not out there for pub-lic consumption.

An apportionment is an instruction fromthe Office of Management and Budget to anagency about how much it may spend from

a Treasury account in service of given bud-get authority in a given period of time.

We havent seen any data about this, andwere not sure that there is any. There shouldbe. And we should get to see it.

An allocation is a similar division of budget authority by an agency into programs orprojects. We dont see any data on this ei-ther. And we should.

These essential elements of governmentspending should be published for all to see.They are not published, garnering the execu-

tive branch an F.

Obligations: B-Obligations are the commitments to

spend money into which government agen-cies enter. Things like contracts to buy pens,hiring of people to write with those pens,and much, much more.

-

7/31/2019 Grading the Government's Data Publication Practices, Cato Policy Analysis No. 711

15/44

15

Outlay data canbe much, muchmore detailedand timely.

USASpending.gov has quickly becomethe authoritative source for this informa-tion, but it is not the entire view of spend-ing, and the data is dirty: inconsistent andunreliable. The use of proprietary DUNS

numbersthe Data Universal NumberingSystem of the firm Dun & Bradstreetalsoweakens the availability of obligation data.

There is some good data about obliga-tions, but it is not clean, complete, and welldocumented. The ideal is to have one sourceof obligation data that includes every agen-cy, bureau, program, and project. With a de-cent amount of data out there, though, use-ful for experts, this category gets a B-.

Parties: F

When the government spends taxpayerdollars, to what parties is it sending themoney?

Right now, reporting on parties is domi-nated by the DUNS number. It provides aunique identifier for each business entityand was developed by Dun & Bradstreet inthe 1960s. Its very nice to have a distinctidentifier for every entity doing businesswith the government, but it is not very niceto have the numbering system be a propri-etary one.

Parties would grade well in terms ofmachine-readability, which is one of themost important measures of transparency,but because it scores so low on availability,its machine-readability is kind of moot. Un-til the government moves to an open identi-fier system for recipients of funds, it will getweak grades on publication of this essentialdata.

Outlays: C-For a lot of folks, the big kahuna is know-

ing where the money goes: outlays. An out-layliterally, the laying out of fundssat-isfies an obligation. Its the movement ofmoney from the U.S. Treasury to the outsideworld.

Outlay numbers are fairly well reportedafter the fact and in the aggregate. All onehas to do is look at the appendices to the

presidents budget to see how much moneyhas been spent in the past.

But outlay data can be much, much moredetailed and timely than that. Each outlaygoes to a particular party. Each outlay is

done on a particular project or program atthe behest of a particular bureau and agency.And each outlay occurs because of a particu-lar budget authority. Right now these detailsabout outlays are nowhere to be found.

Surely the act of cutting a check doesntsever all relationship between that amountof money and its corresponding obligation/project/program, writes a frustrated BeckySweger from the National Priorities Project.Surely these relationships are intact some-where and can be published.

Plenty of people inside the governmentwho are familiar with the movement oftaxpayer money will be inclined to say, itsmore complicated than that, and it is! Butits going to have to get quite a bit less com-plicated before these processes can be calledtransparent.

The time to de-complicate outlays is now.Its a feat of generosity to give this area a C-.Thats simply because there is an authorita-tive source for aggregate past outlay data.As the grades in other areas come up, outlay

data that stays the same could go down. Waydown.

Conclusion

Many of the entities discussed here arelow-hanging fruit if Congress and the ad-ministration want to advance transparencyand their transparency grades. Authorita-tive, complete, and well-published lists ofHouse and Senate membership, commit-

tees, and subcommittees are easy to produceand maintain, and much of the work has al-ready been done.

The same is true of agencies and bureaus,at least on the executive branch side. Presi-dential leadership could produce an author-itative list of programs and projects withinmonths. Establishing authoritative identi-

-

7/31/2019 Grading the Government's Data Publication Practices, Cato Policy Analysis No. 711

16/44

16

fiers for these basic units of government islike creating a language, a simple but impor-tant language computers can use to assistAmericans in their oversight of the federalgovernment.

The more difficult tasksamendments to

legislation, for example, and discretely iden-tified budget authoritieswill take somework. But such work can produce massivestrides forward in accountable, efficient,responsive, andin the libertarian vision

smaller government.

-

7/31/2019 Grading the Government's Data Publication Practices, Cato Policy Analysis No. 711

17/44

17

Appendix AConceptual Data Model of Formal Legislative Processes in

the U.S. Federal Government

MotivationGoal is to have an

open, authoritative set of machine-processable data covering formal actions of Con-gress and its members

to enable (not create) a variety of uses for a variety of users: for data processors (ontologies, codifications, correlations with other datasets)

for end users (apps, mashups, human-searchable websites, researchers, reporters) for other government entities

Scope of the Specification

a general statement of transparent data practices a conceptual model (descriptive and prescriptive) of desired data concerning the for-mal legislative process

and not of specific publication or serialization technologies or methodologies

Transparent Data Practices

availability permanent

stable (always in same location) complete bulk accessible

incrementally accessible open (publicly accessible and free of proprietary encumbrances)

authority authoritative (authoritative sources will emerge from consistent practices.)

timely/real-time correctable (in response to consumers of data)

machine-discoverability internet-accessible

cross-referenceable machine-processability comprehensive conceptual data model

semantically rich

well-defined, published serializations

Conceptual Data Model

MetamodelEntities

An Entity represents an object in the world. An Entity is composed of unordered namedProperties and is uniquely identified by an Identifier.

-

7/31/2019 Grading the Government's Data Publication Practices, Cato Policy Analysis No. 711

18/44

18

An Entitys Class defines what Properties and Identifiers compose a given Entity.An Entity Class may be specified by other Entity Classes. Such Entity Classes are called

Subclasses of the specified Entity Class. An Entity Subclass inherits the Properties and Iden-tifiers of the Entity Class.

PropertiesA Property consists of a Name and a Value. Names must be unique within an Entity. AValue must be an Entity, a Collection of Entities, or a typed literal.

A Property may be derived or computed, meaning that its value can be inferred fromother Properties.

IdentifiersIdentifiers uniquely identify an Entity. Identifiers are composed of the Values of one or

more Properties which taken together are the minimum necessary to identify that Entity.Identifiers should be natural where possible; if there is no natural Identifier for an Entity,

a surrogate Identifier must be assigned and transmitted by an authority. Every Entity musthave an Identifier.

TypesA Type describes a literal Value for a Property. Types may be simple (e.g., Integers, Strings

URIs, Currency Amounts, Dates, etc) or complex (XML documents, PDF documents, etc).This specification does not define the textual representation for typed Values, but one

should use representations that are standardized, machine-readable, and in conformancewith the principles set forth in the Transparent Data Practices outlined in this document.

CollectionsCollections are groups of Entities indicated together. Collections may be heterogeneous

or homogeneous. Collections may have cardinality constraints.

BagA Bag is an unordered non-unique set of Entities. A single Entity may occur more than

once within a Bag.

ListA List is an ordered non-unique set of Entities. A single Entity may occur more than once

within a List. The sort order should be specified.

SetA Set is an unordered unique set of Entities. An Entity may occur only once within a Set

Ordered Set

An Ordered Set is an ordered unique set of Entities. The sort order should be specified.

ExtendingThis data model is not meant to be exhaustive. It may be extended byaugmentation (add-

ing additional properties to Entity Classes defined in this specification), or bysubclassing(defining new Entity Classes inheriting from an existing Entity Class defined in this speci-fication).

Abstract Entity Classes may not be augmented, only subclassed.

-

7/31/2019 Grading the Government's Data Publication Practices, Cato Policy Analysis No. 711

19/44

19

Any extensions must make use of a namespacing mechanism to prevent Property Nameand Entity Class Name collisions with other extensions. No namespacing mechanism is de-fined by this specificationnamespacing mechanisms are implementation-specific.

Metamodel Notation

The following notation is used to describe entities.[SuperClassName] EntityClassNameDescription of Entity Class.

Identifier (PropertyName1, PropertyName2, . . .) this defines the property names that com-pose the Entity Classs identifierPropertyName: PropertyValueType[cardinality constraints] {collection information and othernotes}/DerivedPropertyName:PropertyValueType

Model (Entity Classes)Static Entities

Static Entities are those which change infrequently.

BodyAn abstract Entity Class representing an official body of people.Body ConstitutionalBody

An abstract Entity Class representing the House or Senate. This Entity Class is unusual inthat most of its properties are derived. In principle, the value of these properties may bederived by examining all open Terms of all FederalElectiveOfficeholders.

date: date {all other properties of this Body are assertions which are true on the dateindicated by this property}/congress: number/session: number

ConstitutionalBody HouseOfRepresentativesThe membership of the House of Representatives on a given date

/speaker: FederalElectiveOfficeholder/majorityLeader: FederalElectiveOfficeholder/minorityLeader: FederalElectiveOfficeholder/majorityWhip: FederalElectiveOfficeholder/majorityWhip: FederalElectiveOfficeholder/members: FederalElectiveOfficeholders[1..n] {Set, includes all members of theHouse of Representatives for a given Congress}

ConstitutionalBody SenateThe membership of the Senate on a given date

/senatePresident: FederalElectiveOfficeholder {always the Vice President}/presidentProTempore: FederalElectiveOfficeholder/majorityLeader: FederalElectiveOfficeholder

/assistantMajorityLeader: FederalElectiveOfficeholder/minorityLeader: FederalElectiveOfficeholder/AssistantMinorityLeader: FederalElectiveOfficeholder/members: FederalElectiveOfficeholders[1..n] {Set, includes all members of the Sen-ate for a given Congress}

Body AbstractCommitteeAbstract Entity Class shared by Committees and Subcommittees

Identifier code: string

-

7/31/2019 Grading the Government's Data Publication Practices, Cato Policy Analysis No. 711

20/44

20

house: ConstitutionalBody_enum {house, senate, or joint} name: stringjurisdiction: string {describes committees purview} chairman: FederalElectiveOfficeholder[1,2] {Set, two chairmen reflects co-chair-manship}

rankingMember: FederalElectiveOfficeholder[0,1] {leading member of the minorityparty, may be empty if committee has co-chairmanship} members: FederalElectiveOfficeholder[1..n] {Set, complete including chairman andrankingMember}

AbstractCommittee CommitteeA Congressional Committee. Includes the Committee of the Whole.

subcommittee: Subcommittee[0..n] {Set}AbstractCommittee Subcommittee

A congressional subcommittee: musthave only one parent Committee. Identifier code: string {full Identifier is (Committee code, SubCommittee code)}

CongressA two-year meeting of the United States Congress composed of Sessions.

Identifier number: integer start: date end: date sessions: Session[1..n] {OrderedSet}

SessionA meeting of a Congress. A Session mustbe part of one and only one Congress.

Identifier number: integer {full identifier is (Congress number, Session number)} start: date end: date

SeatRepresents a Congressional Seat. This is an abstract class which exists solely to defineSubclasses; there are no concrete Entities of this Class.

state: usa_stateSeat HouseSeat

A Seat in the House of Representatives district: integer {0 for at-large}

Seat SenateSeatA Seat in the Senate

class: integer {senatorial class: 1, 2 or 3}Term

Represents the time during which an official seat is held. start: date end: date office: House

Term CongressionalTermRepresents a Congressional Term. A new Term beings when a person is sworn in.

seat: Seat/congress: Congress {OrderedSet}

Term CongressionalOfficialTermRepresents a Term of a Congressional office aside from Congressional Membership.

office: congressionaloffice_enumTerm ExecutiveTerm

-

7/31/2019 Grading the Government's Data Publication Practices, Cato Policy Analysis No. 711

21/44

21

Represents a Term of an Executive office. office: executiveoffice_enum {president or vice president}

PartyAffiliationRepresents the time during which a person is a member of a party.

start: date

end: date party: party_enumPerson

Represents a Person. This is an abstract class which exists solely to define Subclasses;there are no concrete Entities of this Class.

honorific: string {optional} firstName: string middleName: string {optional} lastName: string suffix: string {optional}

Person FederalElectiveOfficeholderRepresents a Person who holds an elective federal office. All federal elective officeholders

should be identified by a single identifier system. terms: Term {Set} parties: PartyAffiliation {OrderedSet; ordered by start date} officialPortrait: image gender: gender_enum/currentTerm: Term/currentParty: {the current party affiliation of the officeholder}

Person FunctionaryA person who is identified by title or purpose rather than by name. This is used for non-FederalElectiveOfficeholders who appear frequently in congressional proceedings butwhose individual identities are not important, such as a clerk or a chaplain.

title: string

Substantive EntitiesSubstantive Entities are those which contain information on the deliberations of Con-

gress.Bill

A Bill in Congress that has not become law. Identifier (congress, type, number) congress: Congress type: bill_type number: integer text: billtext {must include machine-extractable title and bill body text information} sponsor: FederalElectiveOfficeholder

isByRequest: Boolean {indicates introduction without a show of support for the bill} cosponsor: FederalElectiveOfficeholder[0..n] {OrderedSet, date of cosponsorshipmust be recoverable through the actionlog} actionlog: Action {List, only actions that concern this bill}/state {state of the bill; inferred from actionlog and bill state machine}/introduced: datetime {date on which bill was introduced; inferred from actionlog}/introducedSession: {session during which bill was introduced; inferred from ac-tionlog or date introduced}

-

7/31/2019 Grading the Government's Data Publication Practices, Cato Policy Analysis No. 711

22/44

22

PublicLawA Bill which has passed into law.

Identifier (congress, lawnumber) congress: Congress lawnumber: integer

bill: Bill {The bill passed to create this law.} dateEnacted: dateAmendment

An amendment to a Bill or to another Amendment. Identifier (object {Bill}, number) {the identifying object must be a Bill; it is foundby following the object property of an amendment entity through its parent entitiesuntil a Bill is found.}venue: Body {where the amendment was offered} adoptionDate: datetime {if it was adopted, the time at which the amendment wasadopted} number: integer {a monotonically increasing number unique among all amend-ments for a given Bill}

object: Bill, Amendment {the thing amended; must eventually terminate at a Bill} changes: amendmentchange {the changes themselves; should be machine-process-able can be applied to the object by machine}/afterChange: billtext, amendmentchange {optional; the text of the Bill or Amendment after applying the change}/introduced: datetime {the time at which the amendment was introduced, inferredfrom the Motion that introduces it}

MeetingA specific temporally and spatially delineated gathering of a Body. Includes House ofRepresentative, Senate, Committee, and Subcommittee meetings.

legislativeDay: integer {A meetings call to order and adjournment define the bound-aries of a legislative day. Legislative days are numbered sequentially and numbering

is reset at the beginning of a new Congress} start: datetime end: datetime location {physical location} title: string {optional: the official title of the meeting if one exists} purpose: text {optional} billSubject: Bill[0..n] {Set; bills discussed at a meeting} meetingBody: Body meetingType: meeting_type participants: Person[1..n] {Set} statements: LegislativeStatement {OrderedList, by time} records: Record {Set, transcripts of the meeting}

materials: url {Set, reference to supplemental non-transcript documents used in themeeting}

LegislativeStatementSomething said to a Body convened in a Meeting.

Identifier (meeting, time) time: datetime/meeting: Meeting {inferred} speaker: Person

-

7/31/2019 Grading the Government's Data Publication Practices, Cato Policy Analysis No. 711

23/44

23

bill: Bill {optional, bill which is mentioned or indicated by the speaker} text: transcript {optional} officialText: transcript {optional}video: url {optional, reference to video files}/records: Record {Set, Records which include this statement, inferred from the meet-

ings records property}RecordA record of the entire content of a meeting released as a single document. Although notcomposed of LegislativeStatements, these should be derivable from the text, video, oraudio. Must include at least one of the optional properties.

source: text {who prepared the record} released: date text: Transcript {optional}video: video {optional} audio: audio {optional}

ReportA report submitted by a committee to a house of Congress

number: integer {identifier assigned when report is filed} committee: AbstractCommittee {Committee or SubCommittee} text: string {the text of the report in a structured markup language}/contains: Vote, Bill, Amendment, Decision {Set; entities present in the report itself;should be inferred from the text}/about: Bill

Administrative EntitiesAdministrative Entities are those that affect the state of a Bill.

MotionA formal proposition put before a Body which requires the consent of that Body tobe approved. The thing approved depends on the nature of the Motion, but includes

Amendments, passage of Bills, adjournments, etc. Motions are closely tied to Decisions. Identifier (meeting, time) time: datetime meeting: Meeting {the meeting in which the Motion was made}/before: Body {the Body to whom the proposition is addressed and from whom itrequires a Decision; inferred from meetings Body} motionType: motion_type {optional; where the proposition is of a standard type out-lined in the rule it is indicated here; otherwise the proposition text itself must suffice} proposition: string {the natural-language text of the motion} object: Bill, Amendment, Meeting {optional; where the proposition is about someobject it is indicated here. The object should be evident from the proposition.} decisions: {OrderedSet; A motion may have several Decisions because members may

object to a Decision. The last and only the last Decision in this set must be the decid-ing one and have an isDeciding property set to true}/isAdopted: Boolean {inferred from decisions property}

Motion ReferralThe assignment of a bill to a committee for consideration. This is a Motion with a mo-tionType of to refer and a Bill as its object.

terms: referral_term {whether the bill is to be considered by all committees at onceor one at a time}

-

7/31/2019 Grading the Government's Data Publication Practices, Cato Policy Analysis No. 711

24/44

24

referredTo: Committee {List}Decision

The expression of assent or dissent by a Body for or against a Motion. Identifier (motion, time) time: datetime

motion: Motion {the motion being decided}/proposition: string {inferred from Motion}/object {inferred from Motion} objectionGrounds: text {optional; if there is an objection to the outcome of thisDecision, the grounds for the objection is noted here} objector: FederalElectiveOfficeholder {optional; present if there is an objection} type: decision_type {the means of measuring assent by the Body as a whole, e.g. byroll call} rule: decision_rule {the type of assent required by a Bodys members, e.g. simplemajority, lack of objection} result: decision_result {the final outcome of the decision} isDeciding: boolean {whether this Decision was the final and deciding one for the

referenced Motion; if true, it must be the last Decision for a given Motion and itmust have no value for the objector and objection properties}Decision RollCall

A Decision resolved by voting. Identifier (Congress, Session, number) {congress and session are inferred fromthe motion} number: integer {the number assigned to this roll call}votes: Vote[1..n] {Set}

VoteAn individual vote

voter: FederalElectiveOfficeHoldervote: vote_cast

CommunicationA formal message or communication between houses of Congress or the president andCongress

Identifier (Congress, House, number) {Congress and House are inferred from theMeeting indicated by the introducedAt property} number: int {a monotonically increasing number uniquely identifying the commu-nication; resets at the beginning of each Congress} from: Body to: Body introducedAt: Meeting text: communication {content of the communication with machine-processablemarkup}

summary: communication {summarized content of the communication as shownin the House or Senate Journal}/about: Bill {Set, optional; derived from text property. If the communication refer-ences one or more bills, these should be accessible through this property}

Actions/EventsRelationship to Entity Classes

Actions are an event-based, incremental view of congressional activities. Every Action

-

7/31/2019 Grading the Government's Data Publication Practices, Cato Policy Analysis No. 711

25/44

25

should contain enough information to fully specify either a new entity or a set of modifica-tions to an existing entity, or both.

The entity an action modifies is called the objectof that action.An ordered list of actions with an identical object is called aactionlog. Actionlogs should

be available for entities retrieved through bulk access. For example, a Bill Entity should have

some way to list all actions that affected it.

Action Entity ClassAction

Identifier (meeting, timestamp) timestamp: datetime meeting: Meeting type: action_type object: Entity {Set}

Action TypesBelow are the defined action types and the Entity they create or modify

CallToOrder: Meeting, Session, CongressAdjourn: sets end date on Meeting, Session, or Congress SwearIn: Term {refers to a Person indirectly} Establish: Committee, Subcommittee Introduce: Bill Refer: Referral, Bill Report: Bill Cosponsor: Bill Remove-Cosponsor: BillAmend: Bill, Amendment Say: Statement, Transcript Decide: Decision {refers to Bill, PublicLaw, or Amendment indirectly}

Present: Report, Communication Pass: BillVeto: Bill

State MachinesIn principle the set of allowed action types and entity modifications at any point in a

sequence of actions is constrained by the state of those entities. Some actions advance thestate of entities in such a way that other actions upon those entities are no longer possibleand new actions are possible. (For example, a Meeting that has been called to order may notbe called to order again.)

The rules that govern the transitions between states are called state machines. Because ofthe complexity of the formal legislative process and because the details of this process may

change over time, this specification does not rigorously define a set of state machines gov-erning entity states.

Bill StatesHowever, the value of the Bill state property is governed by a state machine because the

state of a Bill is important to know and difficult to discover algorithmically.Below is a description of the defined bill state values and their types.

introduced

-

7/31/2019 Grading the Government's Data Publication Practices, Cato Policy Analysis No. 711

26/44

26

Last action was a successful motion to Introduce.referred

Last action was a successful motion to Refer.reported

Last action was aReportby committee.

pass.houseLast action was aPass by the House for a bill originating in the House which requiresboth chambers to be enacted. The bill must go to the Senate.

pass.senateLast action was aPass by the Senate for a bill originating in the Senate that requires bothchambers to be enacted. The bill must go to the House.

pass_back.houseLast action was aPass by the House for a bill originating in the Senate which requiresboth chambers to be enacted, but the bill contains modifications to which the Senatemust agree. Modifications are noted by successful Amendactions since the Pass actionin the House.

pass_back.senate

Last action was aPass by the Senate for a bill originating in the House that requires bothchambers to be enacted, but the bill contains modifications to which the House mustagree. Modifications are noted by successful Amendactions since the Pass action in theSenate.

passedLast action was aPass by any chamber which was sufficient for the bill to achieve finalpassage.

For simple resolutions, the bill passed in the originating chamber. This is the finalstate for a simple resolution. For concurrent resolutions, the bill passed identically in both chambers. This is thefinal state for concurrent resolutions. For constitutional amendments, the bill passed identically in both chambers, but

must still be ratified by the states. For all other bill types, the bill passed identically in both chambers and must bepresented to the President to be signed or vetoed.

vetoedThe last action was that the President vetoed a passed bill. The veto may still be overridden

veto_override.houseThe last action was that the House overrode a presidential veto, but the Senate has not.

veto_override.senateThe last action was that the Senate overrode a presidential veto, but the House has not.

enactedThe bill has become a public law or constitutional amendment either by presidential sig-nature, veto override by both houses, or state ratification. This is a final state.

Types (property-level specifications)The exact representation of the types below will depend on the concrete data model that

implements this abstract model. Use existing standards where possible and aim for unam-biguous machine-readability.markuptype

An abstract type. A markuptype is a document with inline machine-processable mark-up (e.g. XML) from which it is easy to extract contained or related Entities and other

-

7/31/2019 Grading the Government's Data Publication Practices, Cato Policy Analysis No. 711

27/44

27

semantic information.Special considerations:

References to U.S. Public Laws or Codes and Statues should include an explicit ma-chine-readable reference to the prior law affected.Agencies and Programs should be referenced by a standard numbering scheme, such

as MAX codes or contractor codes, which are unambiguous over time. Where a person is mentioned, this fact should be indicated inline with a machine-readable proper name even if a unique identifier of the person is not available. Where a location is mentioned, this fact should be indicated inline with a machine-readable name even if a unique identifier of the location is not available. Where a government or agency is mentioned, this fact should be indicated inlinewith a machine-readable name even if a unique identifier of the government is notavailable. At the very least, federal agencies and U.S. state governments should haveunique identifiers.

billtext (markuptype)The text of a bill. Titles, agencies, or programs affected, U.S. Code sections affected, au-thorizations or appropriations of funds and their amounts, locations, people, foreign